Abstract

The broad availability of connected and intelligent devices has increased the demand for Internet of Things (IoT) applications that require more intense data storage and processing. However, cloud-based IoT systems are typically located far from end-users and face several issues, including high cloud server load, slow response times, and a lack of global mobility. Some of these flaws can be addressed with edge computing. In addition, node selection helps avoid common difficulties related to IoT, including network lifespan, allocation of resources, and trust in the acquired data by selecting the correct nodes at a suitable period. On the other hand, the IoT’s interconnection of edge and blockchain technologies gives a fresh perspective on access control framework design. This article provides a novel node selection approach for blockchain-enabled edge IoT that provides a quick and dependable node selection. Moreover, fuzzy logic to approximation logic was used to manage numerical and linguistic data simultaneously. In addition, the Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS), a powerful tool for examining Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) problems, is used. The suggested fuzzy-based technique employs three input criteria to select the correct IoT node for a given mission in IoT-edge situations. The outcomes of the experiments indicate that the proposed framework enhances the parameters under consideration.

1. Introduction

Recently, many types of network-based systems have become prevalent, such as the Wireless Body Area Network (WBAN) [1], mobile networks [2], spatial-temporal networks [3], and the Internet of Things (IoT) [4]. Since the invention of the IoT by Kevin Ashton, the concept of IoT has become more prosperous and more powerful [5,6]. IoT has been described as a network in which different objects with exclusive identifiers and the capability to transmit data are interconnected without the need for human interaction over the Internet [7,8,9]. The rapid growth of 6G-enabled IoT has recently piqued academia and industry’s interest [10,11,12]. Further, the issues related to privacy, anomaly, and security are becoming essential as the applications become more prevalent [13,14,15,16]. Safe and robust communication and networks include authentication, data sharing, and analysis [17,18,19].

Blockchain is devised to present data availability and tamper resistance in a decentralized environment and an immutable that is tailored to increase IoT data integrity, security, and availability while optimizing IoT applications [20]. It is an encoded, dispersed ledger technology for building tamper-resistant real-time records which is applicable in many fields [21,22]. Furthermore, this platform provides a reliable environment for IoT devices by securely interconnecting them and protecting them from the adversarial attacks that plague centralized client/server models [23].

Moreover, the network of IoT is assorted for a particular action, meaning that specific IoT nodes will complete it better than others. The critical problem that has been considered in this paper is determining which nodes are best suited. Obtaining the right nodes at the right time and their selection helps mitigate common IoT-based concerns such as network lifespan, allocation of resources, and trust in the gathered data [24]. The issue of energy and routing could be solved by choosing the node rather than optimizing node numbers and their location [25]. In this case, the nodes can be organized in any order, and only a subsection of nodes is stimulated at any given time for a given mission. By selecting the appropriate subset of nodes based on the task criteria, node selection aids energy efficiency [26]. Furthermore, there is individual-based selection, in which every node is evaluated independently and the best nodes are selected, or group-based selection, in which possible clusters are evaluated as a whole and the finest set is selected. So, evaluations are focused on the task specifications and constraints [27]. The latest selection strategies, in particular, are not well-suited to localization tasks due to several flaws. First, the present selection methods concentrate on comprehensive environmental monitoring, making them less application-oriented [28]. The information gathered is not used in a response system to update the community of nodes, which could be critical for increasing the speed of localization. Most studies on the area of interest coverage in the literature are planned for nodes with sensing ranges. However, this is not true for all sensors, for example, radiation sensors, which do not have a range [29]. These flaws necessitate the use of a dynamic selection outline that acclimates to the localization mission and uses the gathered readings to update the node collection [30].

Fuzzy Logic (FL) is a method that employs approximation logic to manage linguistic and numerical data simultaneously [31,32]. To achieve an actual output and determine the details of the non-linear mapping, fuzzy logic works on stages of input likelihoods [33]. Furthermore, the models based on Markov Theory and Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) have been used to solve engineering problems in science, technology, economics, and other fields in numerous studies [34,35,36]. However, MCDM models, which combine computational and mathematical methods to provide a subjective assessment of performance criteria by decision-makers, have emerged as a part of the process study. In addition, the Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS), a powerful tool for examining Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) problems, is used. TOPSIS has been widely utilized to tackle decision-making difficulties. This strategy is based on comparing all the possibilities in the issue. The TOPSIS approach provides the following advantages: Simplicity, rationality, comprehensibility, high computational efficiency, and the ability to quantify the relative performance of each choice in a simple mathematical form. Consequently, in this investigation, blockchain technology has been employed to improve the privacy and security of the system. Using an edge platform can also improve system efficiency, reduce latency, and improve performance. To select an appropriate node for a specific mission, the proposed fuzzy-based method uses three input parameters: IoT Node’s Free Buffer Space (INFBS), IoT Node’s Remaining Energy (INRE), and IoT Node’s Distance to Event (INDE). Using a hybrid MCDM model, the node selection issue in blockchain-enabled edge-IoT platforms using a fuzzy-based method has been analyzed. This investigation’s significant outcomes are listed below:

- Proposing a secure framework for integrating edge and blockchain technologies into IoT networks to ensure data protection and energy efficiency.

- Providing a platform for node selection for various IoT-edge frameworks.

- Utilizing an edge platform to increase performance, decrease latency, and increase system efficiency.

- Introducing a novel fuzzy-based method using a hybrid MCDM model.

- Improving parameters such as INFBS, INRE, and INDE.

2. Related Works

In the last several years, much research has been conducted and is currently being performed on distributed computation. Researchers have focused on various topics, including architectural design, bug report prediction, and overall system performance [37,38]. Moreover, several optimization strategies are accessible for the mobile computing area [39,40]. Scholars have focused on many elements of IoT optimization under various restrictions. Most researchers have focused on reducing power consumption and overall system delay and optimizing additional factors such as cost and bandwidth utilization. Qureshi and Kumar [41] provided a general logistics benchmarking process with the Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (FAHP). Logistics’ essential success elements are recognized and prioritized in the literature. Using these crucial success indicators, LOGINET, a 3PL services provider situated in western India, is benchmarked against four other service providers. Their relative ranking has also been displayed using the standard.

Wudhikarn and Chakpitak [42] created an integrated technique for overcoming the inadequacies and gaps observed in previous benchmarking studies, as well as for benchmarking Intellectual Capital (IC) in the undeveloped logistics sector. The suggested technique integrated the analytic network process and the concept of thinking and non-thinking assets with the generic benchmarking procedure to address the lack of consideration of relationships among previous benchmarking concepts and the impacts of their managerial factors, as well as to examine the wide range of elements and indicators of IC influencing the sustainable development of organizations.

Riaz and Qaisar [43] developed a mathematical outline for minimizing latency and choosing nodes in edge-based networks. Furthermore, a solution based on branch-and-bound and outer approximation is thoroughly described. A comprehensive study of the suggested algorithm’s convergence is provided, demonstrating that it converges linearly and offers the best answer. According to experimental data, the Outer Approximation Algorithm (OAA) successfully optimized the system as the total system throughput rose with node numbers. According to their findings, their technique can considerably minimize the time required for node selection and total latency while maximizing the output. To compare OAA outcomes, a many-to-one matching-based method was employed as a baseline. OAA beats the matching-based method, according to the results. Other features of the service model and different service parameters, such as workload balancing among MEC nodes, can be catered for in this work.

Furthermore, Redhu and Anupam [44] proposed an optimum relay node-choosing technique to quickly forward data over time-varying IoT networks. Poisson point processes are used to describe the movement of dense IoT networks. Relay nodes are selected by balancing the network’s data latency and risk of packet loss. The suggested approaches’ performance is tested in a variety of network topologies. The effects of the risk of packet loss in a time-varying network, the duration of the connection history on data latency, data on delayed connectivity, node density, and transmission range are shown in the results. The suggested bi-objective optimization issue is equated to single-objective optimization in terms of performance. When the latter is optimized, the performance of such approaches is found to deteriorate. On the other hand, the technique works well while minimizing data delay and packet loss danger.

In addition, for eliminating IoT nodes and selection in OppNets, Cuka and Elmazi [45] provided two fuzzy-based schemes: Node removal and node selection. They employed three input measures for node removal, INDE, NFBS, and the IoT node’s battery level, and four input measures for selecting nodes, namely ‘Node Contact Duration’, ‘Node Inter Contact Time’, ‘Node’s Unique Encounters’, and Node’s Number of Past Encounters. IoT Node Selection Possibility (INSP) is the output parameter. The findings demonstrate that the suggested techniques correctly excluded and selected IoT nodes. They found from both systems that in the Node Elimination System (NES), the nodes that did not meet the fundamental resource readiness criterion were removed from the selection process. They discovered in NES that IoT nodes with adequate principal resources are chosen for further job selection.

Lu and Wudhikarn [46] presented an integrated model for producing intellectual capital performance indicators, which can be used in a financial shared-services organization to enhance the standard IC process model. Their research aims to employ IC management in conjunction with the MCDM approach to build an IC measurement system and use the best–worst method to determine the weights of IC performance indicators to prioritize KPIs. These prioritized IC performance indicators assist managers in focusing on the important components of their IC management and effectively allocating the organization’s limited resources. Their hybrid solution was applied in four commercial courier businesses. The suggested technique prioritized and determined the magnitude of the aspects under consideration, including the IC elements and their performance metrics. The findings show that management prioritizes the IC of the best performer and other enterprises. Their benchmark results revealed gaps, the potential for improvement, and prospects for sustainable development for inferior logistics businesses.

Shukla and Tripathi [27] developed a three-phase implementation technique. The network is initially installed in a hierarchical cluster architecture, expanding to any level. The effective relay node selection technique is used in the second stage to elect the sensor node as a relay node. The quantity of relay nodes available in each cluster is determined by the node and relay node communication range density, and it varies for every cluster. The Energy-Efficient Communication (EEC) protocol transmits network data to the base station in the last phase. They compared the suggested approach to several protocols and found that it is superior in the context of depletion of energy and lifespan of the network. On a green WSN-Assisted IoT deployment, the energy-efficient consumption may be simply deployed. Furthermore, the method continues to outperform the comparable protocol as the size of the network and the number of nodes grow.

Redhu and Hegde [47] offered an effective relay node selection technique based on IoT network contact patterns. Digital traces of computer equipment give a priori connect pattern information that aided in improving the data forwarding scheme’s performance. This information was used in the approach, which combined data latency and connection dependability for reliable data forwarding over time-varying IoT systems. The technique’s performance is assessed in a variety of network topologies. The results showed how using a priori network contact patterns may reduce data latency and improve dependability. The impact of the reliability of a link and connection history duration on data latency, node density, mobility variance, and transmission range is also investigated. The technique works well while minimizing data latency and increasing connection dependability.

Finally, Alagha and Singh [24] suggested a two-stage node selection technique that employed genetic and greedy algorithms. The first step used a cluster-based methodology associated with a genetic algorithm to obtain primary data about the source. Then, the active node readings are dynamically employed in the second phase to pick the following best group of active nodes using an individual-based greedy selection process. Both steps are combined in the Data-driven Active Node Selection (DANS) framework, a dynamic framework for tackling localization issues in IoT sensing applications. In addition, a methodology for determining coverage has been devised for sensors that may not have a detecting range. Studies using real-life and synthetic datasets confirm the efficacy of the technique. The findings showed that the suggested approach, DANS, surpassed current benchmarks in terms of QoL by up to 52% on the synthetic dataset and up to 75% on the real-life dataset. Furthermore, using a simulated dataset, DANS was found to accomplish more for small groups of active nodes, outperforming benchmarks by up to four times in terms of QoL. Finally, side-by-side analyses of state-of-the-art IoT node selection methods are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

A comparison of the discussed IoT methods.

3. Proposed Method

However, thanks to evolving edge device technology, the combination of blockchain and edge allows for secure network and computation access and control at the edges. Furthermore, since both blockchain and edge have a distributed structure, they are better suited to each other. As a result, incorporating edge and blockchain into IoT is advantageous, given the high-security requirements and intensive computation in IoT networks. In this research, the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) is used for analyzing MCDM problems, which Lai and Liu [48] developed. This approach is constructed on the concept that the selected options must have the shortest distance to the positive ideal solution (which minimizes the criteria about cost (worst criteria) and maximizes the best measures) and the furthest distance to the negative ideal solution [49]. In TOPSIS, the weights of the measures and rankings of the options considered for the analysis are crisp numeric values. Hence, it does not consider the vagueness of human judgments.

Further, it may be noted that crisp values cannot evaluate real-life problems; therefore, using linguistic terms and further analyzing the fuzzy environment would yield better results [50]. Thus, the Fuzzy TOPSIS methodology has been employed in this research study. Moreover, the terminologies used in the TOPSIS methodology are indicated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Notations list.

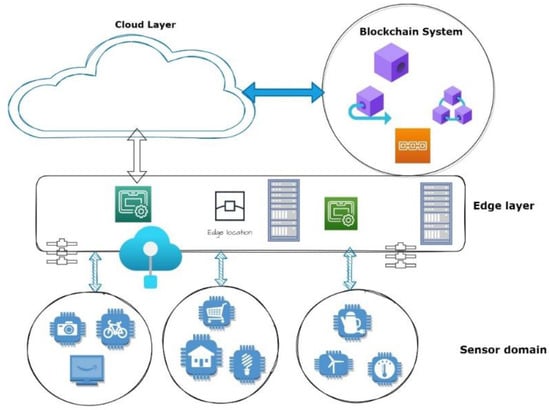

- System architecture

This architecture has been split into three layers after integrating the edge platform and blockchain into the IoT system: Edge in the linked IoT devices on behalf of an IoT domain at the bottom, and cloud computing at the top. Figure 1 shows the proposed architecture of the blockchain-based IoT structure.

Figure 1.

The proposed Blockchain-enabled IoT System’s architecture.

In this architecture, the IoT area has a conforming edge gateway that becomes a peer node in the blockchain network and communicates with the cloud via WiFi. If certain conditions are met, the gateway node will also act as an orderer node in the consensus process. Due to our design, IoT devices do not join the blockchain network as peer nodes. Instead, they connect to their domain’s edge gateway and exchange access control data with it via the lightweight MQTT protocol. Edge gateways can connect to the WiFi network and communicate with the cloud in milliseconds, thanks to the WiFi base station, which connects the edge and the cloud. For example, the industrial edge gateway can swiftly and securely access storage resources in the industrial cloud and provide essential data for remote monitoring.

The manager could modify the access control policy in our platform using the chain code and send it to the blockchain. A collection of subject–object access permissions is represented by every policy. The explicit content of the access control policy is kept in the state database, and transaction details are recorded in the ledger. As a result, the access control policy may be audited and traced. For behavior-gathering and credit computation, the edge gateway will initially use MQTT to regularly gather behavior information from IoT devices inside its area. The gateway subsequently standardizes the data before writing it to the blockchain to record its behavior. Finally, the gateway frequently checks the domain credit value, guiding dynamic node selection in the following consensus procedure. The handler could seek access permission for obtaining resources using chain code for user authorization. The chain code will verify access control restrictions once the user submits a request. The chain code will return the access authorization if the access request satisfies the policy’s properties. The user might then utilize the edge gateway to connect to IoT nodes.

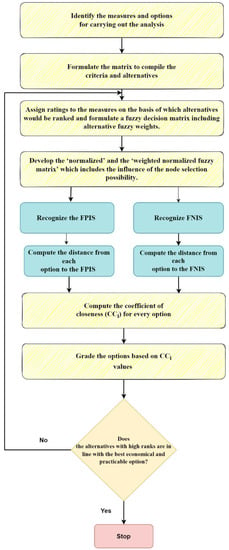

Algorithm 1, used to determine the rank using a fuzzy-based hybrid MCDM approach, is as follows:

| Algorithm 1. Proposed method | |

| Step 0 | Determine the measures (INFBS, INRE, and INDE) and options (27) for the analysis. |

| Step 1 | Accept inputs or assignment ratings for three criteria and alternatives from the user |

| Step 2 | Formulate criteria and alternatives decision matrix showcasing the magnitudes of assignment ratings for INFBS, INRE, and INDE and 27 options. |

| Step 3 | Formulate the ‘fuzzy normalized decision matrix’ for the benefit and cost criteria using Equations (2) and (3), respectively. |

| Step 4 | Develop the ‘fuzzy weighted normalized matrix’ using step 4 of the methodology, which considers the influence of the node selection possibility. |

| Step 5 | Compute the FPIS and FNIS using Equations (5) and (6), respectively. |

| Step 6 | Determine the distance from every option to the FPIS and FNIS employing Equations (7) and (8), respectively. |

| Step 7 | Determine CCi for each option employing Equation (9). The Cci weights help in identifying the ranks of the alternatives. |

| Step 8 | Determine the rank of alternatives based on the magnitude of the Cci. |

| Step 9 | Check if other options with high positions are feasible. If ‘No’ GOTO Step 3. If ‘Yes’ GOTO Step 10. |

| Step 10 | Print-Optimal node selection as output |

| Step 11 | STOP |

On Hyperledger Fabric, the chain code may be thought of as a smart contract. The chain code is how the user interacts with the ledger. We may develop interfaces that fulfill specified logic functions for distinct chain codes with the aid of Fabric’s API. There are three sorts of chain codes in the proposed architecture. (1) The Policy Management Chaincode (PMC) adds and maintains access control policies based on the ABAC architecture in this work. Only policy managers, such as object owners, could perform it. The Environment Attribute (EA), Action Attribute (AA), Object Attribute (OA), and Subject Attribute (SA) are the four components of an access control policy. The subject, role, group, and domain are all part of the SA, representing the subject’s basic identity information. SubjectID distinguishes whether the topic is a user or a user’s device. As with OA, we choose two unique identifiers, ObjectID and MAC, as the object’s properties. The AA represents the permissions for a subject–object pair. We utilize an integer to signify various storage permissions (4—Read, 2—Write, 1—execute). The EA reflects the policy’s context condition. The item could only be accessed in a particular context by the subject. Each policy’s information will be kept in PMC. Given the lack of security protection, the system is exposed to infiltration. IoT devices with insufficient processing, memory, and resource availability are vulnerable to becoming tools for thieves to start nefarious conduct. This will cause the infected IoT system to behave abnormally, including deleting, changing, injecting, and retransmitting data packets, among other things. Further, the monitoring and recording of this data, linked with the access control system, for detecting harmful conduct, and its prevention from spreading as quickly as feasible may be performed.

- Suggested method

TOPSIS with extended triangular functions was proposed by Chen [25], in which the distance between 2 triangular functions was calculated using the vertex method. So, if the 2 triangular functions are x = (a1, b1, c1) and y = (a2, b2, c2), then

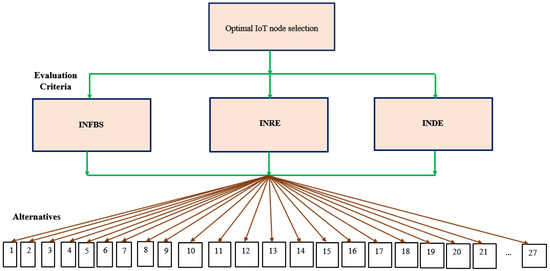

The framework used for this study is given in Figure 2. Further, the fuzzy TOPSIS methodology procedure has been detailed below, and a flowchart of the same is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

The framework used for the optimal node selection that indicates the evaluation criteria and the alternatives.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the fuzzy TOPSIS methodology.

- Identify the measures and options for carrying out the analysis.

- Assign ratings to the measures based on which alternatives would be ranked.

- Formulate “R”.where R = [rij], for the ‘benefit criteria’

Furthermore, for the cost criteria, we have Equation (3).

- Compute “V”, where vij = rij * weight of the criteria (wj).

V = vij

- 2.

- Using the following equations, calculate the Fuzzy Positive and Negative Ideal Solution (FPIS and FNIS).

- 1.

- Calculate the distance of every option from ‘FPIS’ and ‘FNIS’ employing Equations (7) and (8).

- 2.

- Compute for each option based on Equation (9).

- 3.

- Grade the options using the values. The higher the intensity, the better the alternative.

4. Results

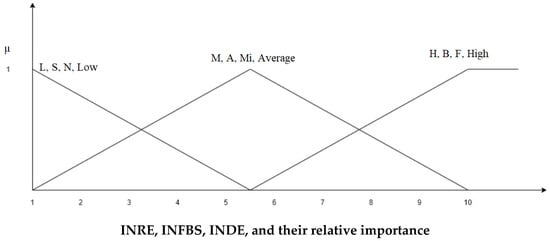

In this study, for selecting a proper IoT node, three parameters, namely INFBS, INRE, and INDE, have been considered. Furthermore, the fuzzy TOPSIS methodology has been used to rank the IoT node possibilities. Table 3 highlights the parameters, term sets, and triangular fuzzy membership functions.

Table 3.

Parameters along with their term sets and membership functions.

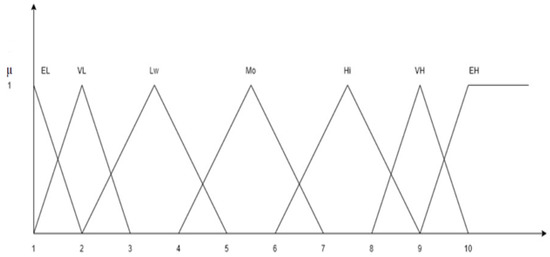

As discussed earlier in the research methodology section, in the Fuzzy TOPSIS approach, the relative importance of the parameters is considered for ranking the alternatives. Hence, the linguistic terms indicating the relative importance of the parameters have been shown in Table 3, along with their membership functions. Figure 4 represents the Fuzzy triangular membership functions for INRE, INFBS, and INDE, and their relative importance. Table 4 indicates the linguistic terms for the INSPs, their codes, and corresponding triangular fuzzy membership functions. For INSPs, seven levels have been considered, namely “Extremely Low: EL”, “Very Low: VL”, “Low: L”, “Moderate: M”, “High: H”, “Very High: VH”, and “Extremely High: EH”. Later, the fuzzy rule base was developed, as shown in Table 5, reflecting each criterion’s nature and selection possibilities (See Figure 5). Out of three parameters, INRE and INFBS are the benefit parameters, whereas INDE is the cost criterion. It may be noted that the weights of the selection possibilities should be considered for ranking the node possibilities, along with the relative importance of the selected attributes. Table 6 shows the decision matrix with 27 selection possibilities indicating fuzzy weights of the measures chosen and the node numbers.

Figure 4.

Fuzzy triangular membership functions for INRE, INFBS, and INDE, and their relative importance.

Table 4.

Term sets and membership functions for node selection possibilities.

Table 5.

Fuzzy rule base.

Figure 5.

Fuzzy triangular membership functions for INSP.

Table 6.

Decision matrix.

A fuzzy normalized decision matrix is shown in Table 7, which was developed using Equations (2) and (3). In addition, in this table, weights of the INSP are indicated, which were taken into account for developing the fuzzy weighted normalized decision matrix shown in Table 8. This table considered weights of relative importance and weights of the selection possibilities, i.e., vij = rij *weight of the criteria (wj)*weight of the selection possibility (ws). Moreover, the FPIS and FNIS values are shown in Table 8, which were calculated using Equations (5) and (6). The distance of each node from the FPIS (〖d_i〗^*) and FNIS (〖d_i〗^-) was computed by employing Equation (1), Equation (7), and Equation (8) and all the values of distances are shown in Table 9. These (〖d_i〗^* and 〖d_i〗^-) values help in calculating the Closeness Coefficients (CCi) using Equation (9), which helps in identifying the ranks of the 27 alternatives. The CCi of all the node numbers is given in Table 9, along with their ranks. It may be inferred from Table 9 that node numbers 27, 18, 17, 9, and 8 have the highest potential for selection as their weights (w27 = 0.960246, w18 = 0.875025, w3 = 0.744288, w9 = 0.677472, and w8 = 0.662365, respectively) are close to the positive ideal solution. On the other hand, node numbers 22, 20, 19, 10, and 1 are the least preferred numbers as their weights, i.e., w22 = 0.087472, w20 = 0.068519, w19 = 0.05284, w10 = 0.050204, and w1 = 0.029671, respectively, are considerably distant from the FPIS.

Table 7.

Normalized Fuzzy decision matrix.

Table 8.

Weighted normalized Fuzzy decision matrix.

Table 9.

Distance from a positive and negative ideal solution and ranks of the node possibilities.

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Directions of Research

One of the most crucial IoT problems in real-world applications is object selection based on customer demand. Effective object selection, identification, and selection of relevant nodes are required to achieve optimal performance. As a result, experts may easily comprehend diverse views on IoT object selection methods. The findings of this work will also aid academics and provide insight into future research topics in this discipline. Furthermore, the disadvantages and benefits of the suggested method were examined, paving the way for the future development of more efficient and practical processes for object selection in IoT contexts. Therefore, fuzzy TOPSIS is a powerful approach for effective decision-making; however, the findings of this study may be validated by employing other tools, namely AHP, ANP, VIKOR, and ELECTRE, in the fuzzy environment. Moreover, a hybrid approach is used to validate and improve the accuracy of the results. In addition, after integrating the edge platform and blockchain into the IoT system, we divided this architecture into three layers: Edge in the center-connected IoT devices on behalf of an IoT domain at the bottom and cloud computing at the top. However, the IoT’s deep integration of edge and blockchain technologies offers a new access control framework design approach. Therefore, this study proposes a unique node selection framework for blockchain-enabled edge IoT that implements a fast and reliable node selection technique. In addition, we developed a hybrid MCDM model mechanism that can dynamically pick select nodes to obtain a rapid and reliable result using the fuzzy approach. In this study, three evaluation criteria, namely INRE, INFBS, and INDE, have been considered, and the Fuzzy TOPSIS approach was used to rank the IoT node alternatives. The results of the experiments indicate that the suggested framework improves the parameters under evaluation.

However, the data storage optimization of blockchain nodes for IoT is not the subject of this article. Instead, we intended to investigate several optimization strategies to lessen the future framework’s expanding storage load. Furthermore, in upcoming studies, the number of criteria may increase, increasing the number of node possibilities. This would make the model more robust and reliable. Moreover, GUI-based simulations could be carried out. Finally, using machine learning techniques for defect prediction of IoT nodes will be interesting in the future [51].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.J.N. and A.H.; methodology, B.B.G.; software, B.B.G.; validation, N.J.N. and M.U.; formal analysis, B.B.G.; investigation, B.B.G., A.H., N.J.N. and M.U.; writing—review and editing, B.B.G., A.H., N.J.N. and M.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are reported in the paper.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable input which has improved the quality of the manuscript substantially. Also, the authors thank Vaibhav Narwane for guiding them through the fuzzy approach.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

References

- Liu, K.; Ke, F.; Huang, X.; Yu, R.; Lin, F.; Wu, Y.; Ng, D.W.K. DeepBAN: A temporal convolution-based communication framework for dynamic WBANs. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2021, 69, 6675–6690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.; Navimipour, N.J.; Unal, M.; Toumaj, S. Machine learning applications for COVID-19 outbreak management. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 15313–15348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, G.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, F.Y. ESTNet: Embedded Spatial-Temporal Network for Modeling Traffic Flow Dynamics. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Lu, L.; Yu, J.; Chen, Y.; Tang, F. Continuous authentication through finger gesture interaction for smart homes using WiFi. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2020, 20, 3148–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.; Jamali, M.A.J.; Navimipour, N.J.; Akbarpour, S. Deep Q-Learning Technique for Offloading Offline/Online Computation in Blockchain-Enabled Green IoT-Edge Scenarios. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, X.; Skonieczny, Ł.; Lv, Z. Recommendation Based on Large-Scale Many-Objective Optimization for the Intelligent Internet of Things System. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 15030–15038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, J.; Gu, Y. Resource allocation in 5G IoV architecture based on SDN and fog-cloud computing. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 3832–3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Gu, Y.; Lv, Z.; Yang, S.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y. RFID Reader Anticollision Based on Distributed Parallel Particle Swarm Optimization. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 3099–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Ding, H.; Wang, B.; Lv, L.; Tian, J.; Wei, Q.; Gong, F. Enhancing Physical Layer Security for IoT with Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access Assisted Semi-Grant-Free Transmission. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Qiao, L.; You, I. 6G-enabled network in box for internet of connected vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 22, 5275–5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Fan, S.; Zhao, J.; Tian, S.; Zheng, Z.; Yan, Y.; Yang, P. Large-scale many-objective deployment optimization of edge servers. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 3841–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.; Navimipour, N.J.; Unal, M. The History of Computing in Iran (Persia)—Since the Achaemenid Empire. Technologies 2022, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Li, Y.; Feng, H.; Lv, H. Deep learning for security in digital twins of cooperative intelligent transportation systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.; Toumaj, S.; Navimipour, N.J.; Unal, M. A privacy-aware method for COVID-19 detection in chest CT images using lightweight deep conventional neural network and blockchain. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 145, 105461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gao, Q.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Yan, L.; Liu, G. A Structural Evolution-Based Anomaly Detection Method for Generalized Evolving Social Networks. Comput. J. 2022, 65, 1189–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chen, X.; Xiong, Z.; Xu, Z.; Liu, G.; Zhang, X. A privacy-preserving aggregation scheme based on negative survey for vehicle fuel consumption data. Inf. Sci. 2021, 570, 526–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xiong, Y.; Li, S.; Song, Z.; Hu, Z.; Liu, F. Multi-Sensor Data Driven with PARAFAC-IPSO-PNN for Identification of Mechanical Nonstationary Multi-Fault Mode. Machines 2022, 10, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.; Navimipour, N.J.; Unal, M. Applications of ML/DL in the management of smart cities and societies based on new trends in information technologies: A systematic literature review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 85, 104089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Gao, T.; Cai, G.; Hai, K.L. Research on electric vehicle charging safety warning model based on back propagation neural network optimized by improved gray wolf algorithm. J. Energy Storage 2022, 49, 104092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.B.; Li, K.C.; Leung, V.C.; Psannis, K.E.; Yamaguchi, S. Blockchain-assisted secure fine-grained searchable encryption for a cloud-based healthcare cyber-physical system. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2021, 8, 1877–1890. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Tripathi, R. DBTP2SF: A deep blockchain-based trustworthy privacy-preserving secured framework in industrial internet of things systems. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2021, 32, e4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Yin-He, S.; Qian, Y.; Zhi-Yu, S.; Chun-Zi, W.; Zi-Yun, L. Method of reaching consensus on probability of food safety based on the integration of finite credible data on block chain. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 123764–123776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, M.A.; Cai, J.; Gao, X.C.; Khan, F.; Mastorakis, S.; Usman, M.; Alazab, M.; Watters, P. Security and blockchain convergence with Internet of Multimedia Things: Current trends, research challenges and future directions. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2021, 175, 102918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagha, A.; Singh, S.; Mizouni, R.; Ouali, A.; Otrok, H. Data-driven dynamic active node selection for event localization in IoT applications-a case study of radiation localization. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 16168–16183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zuo, X.; Huang, J.; Konak, A.; Xu, Y. The continuous pollution routing problem. Appl. Math. Comput. 2020, 387, 125072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Cong, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhong, B.; Fu, Y. Representative task self-selection for flexible clustered lifelong learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 33, 1467–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Tripathi, S. An effective relay node selection technique for energy efficient WSN-assisted IoT. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2020, 112, 2611–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Wu, D.; Pan, C.; Zha, J. Optimal energy strategy for node selection and data relay in WSN-based IoT. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2015, 20, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Li, M.; Liu, X.; Zhao, J.; Cao, W.; Lv, Z. Many-Objective Deployment Optimization for a Drone-Assisted Camera Network. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2021, 8, 2756–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazza, H.; Said, B.; Laallam, F.Z. A hybrid IoT services recommender system using Social IoT. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34 Pt B, 5633–5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zheng, H.; Cai, G.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Koh, L.H. Power-frequency oscillation suppression algorithm for AC microgrid with multiple virtual synchronous generators based on fuzzy inference system. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2022, 16, 1589–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, S. Multi-Sensor Fusion by CWT-PARAFAC-IPSO-SVM for Intelligent Mechanical Fault Diagnosis. Sensors 2022, 22, 3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, G.; Lu, J. Multisource heterogeneous unsupervised domain adaptation via fuzzy relation neural networks. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 29, 3308–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lu, J.; Peng, Y. Hybrid MCDM model for location of logistics hub: A case in China under the belt and road initiative. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 41227–41245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Niu, B.; Liu, L.; He, X. A novel hybrid multi-criteria group decision-making approach with intuitionistic fuzzy sets to design reverse supply chains for COVID-19 medical waste recycling channels. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169, 108228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, Y.; Liu, M.; Wu, P.; Yang, B.; Liu, S.; Yin, L.; Zheng, W. Depth Estimation Method for Monocular Camera Defocus Images in Microscopic Scenes. Electronics 2022, 11, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zheng, W.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, T.; Mu, D. Improving high-impact bug report prediction with combination of interactive machine learning and active learning. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2021, 133, 106530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zheng, W.; Xia, X.; Lo, D. Data quality matters: A case study on data label correctness for security bug report prediction. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2021, 48, 2541–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Zhao, J.; Lv, Z.; Yang, P. Diversified personalized recommendation optimization based on mobile data. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 22, 2133–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Lu, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Kong, L. An indirect eavesdropping attack of keystrokes on touch screen through acoustic sensing. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2019, 20, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.N.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, D. Framework for benchmarking logistics performance using fuzzy AHP. Int. J. Bus. Perform. Supply Chain. Model. 2009, 1, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wudhikarn, R.; Chakpitak, N.; Neubert, G. Improving the strategic benchmarking of intellectual capital management in logistics service providers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, N.; Qaisar, S.; Ali, M.; Naeem, M. Node selection and utility maximization for mobile edge computing–driven IoT. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2022, 33, e3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redhu, S.; Anupam, M.; Hegde, R.M. Optimal relay node selection for robust data forwarding over time-varying IoT networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 9178–9190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuka, M.; Elmazi, D.; Ikeda, M.; Matsuo, K.; Barolli, L.; Takizawa, M. Application of fuzzy logic for IoT node elimination and selection in opportunistic networks: Performance evaluation of two fuzzy-based systems. World Wide Web 2021, 24, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Wudhikarn, R. Using the best-worst method to develop intellectual capital indicators in financial service company. In Proceedings of the 2020 Joint International Conference on Digital Arts, Media and Technology with ECTI Northern Section Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Computer and Telecommunications Engineering (ECTI DAMT & NCON), Chiang Rai, Thailand, 26–28 January 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Redhu, S.; Hegde, R.M. Optimal relay node selection in time-varying IoT networks using apriori contact pattern information. Ad Hoc Netw. 2020, 98, 102065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.-J.; Liu, T.-Y.; Hwang, C.-L. Topsis for MODM. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1994, 76, 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, R.; Raut, R.D.; Gardas, B.B.; Kamble, S.S. Sustainable partner selection: An integrated AHP-TOPSIS approach. Int. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 39, 205–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Barman, A.G. Fuzzy TOPSIS and fuzzy VIKOR in selecting green suppliers for sponge iron and steel manufacturing. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 6505–6525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Shen, T.; Chen, X.; Deng, P. Interpretability application of the Just-in-Time software defect prediction model. J. Syst. Softw. 2022, 188, 111245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).