Abstract

The research elaborates on and empirically verifies an integrative model that describes how the combination of various workplace resources results in the improvement of employee and organizational outcomes. It is based on the Job Demands–Resources model and the Resource-Based View to conceptualize Employee Experience Capital (EEC) as a higher-order construct, consisting of seven interrelation drivers, including digital autonomy, inclusive cognition, sustainability alignment, AI synergy, mindful design, learning agility, and wellness technology. This study examines the effect of these resources in developing two psychological processes, work resonance and employee vitality, which subsequently improves organizational performance. It also examines how the well-being of employees can be a contextual moderator that determines such relationships. The study, based on a cross-sectional design and the diversified sample of the employees who work in various digitally transformed industries, proves that EEC is a great way to improve resonance and vitality, which are mutually complementary mediators between resource bundles and performance outcomes. Employee well-being turns out to be a factor of performance, as opposed to a circumscribed condition. The results put EEC as one of the strategic types of human capital that values digital, sustainable, and wellness-oriented practices to employee well-being and sustainable organizational performance and provides new theoretical contributions and practical guidance to leaders striving to create resource-rich, high-performing workplaces.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Rationale

Contemporary businesses invest significant resources in digital transformation projects, sustainability programmers, employee health, and well-being improvement. However, with all these efforts being implemented simultaneously, empirical results are still sporadic and unsatisfactory. Many companies complain of exhaustion due to long-term active involvement, loss of labor enthusiasm, and the failure to achieve regular benefits on huge investments in human-resources technology. This paradox exists in the context of a more general issue of resource fragmentation: organizations view digital tools, sustainability values, and wellness mechanisms as independent events, not as a cohesive model that creates the experience of an employee. Understanding the relationship between these unequal resources and how they work with one another to create employee resonance and vitality is a big challenge to a modern-day manager. Existing theoretical frameworks do not have a sufficient explanation for this complexity. The High-Performance Work Systems (HPWS) paradigm is a paradigm that bundles HR practices in a synergistic manner; nonetheless, it is mostly process-driven and unsuitable to the specifics of digitalization and sustainability. Psychological Capital (PsyCap) on the other hand focuses on personal abilities—hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism—and does not focus much on the socio-technical environment that develops these abilities. Employee Experience (EX) models focus on touchpoints and emotion more than the organizational resources that support performance. As a result, none of these standpoints adequately reflect the integrative, cross-domain resource system, which contemporary employees face in hybrid, AI-driven, wellness-based workplaces. This gap forms the main research question, as follows: How can organizations integrate their socio-technical and psychological resources to create one higher-quality capital that fosters resonance, vitality, and performance? It is the disintegration of surviving models that creates a theoretical vacuum, as well as a managerial one, which, however, is a sum of the parts but does not capture the entirety of the phenomenon.

1.2. Contemporary Workplace Drivers

Digital autonomy is the degree to which workers take the initiative in the modalities of technology used in their work processes, a construct that has always been correlated with intrinsic motivation and engagement (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Marsh et al., 2024). Inclusive cognition denotes the recognition of aberrant cognitive profiles, such as neurodiversity, which, in its turn, leads to greater problem-solving abilities and creativity (Edmondson, 1999). Company alignment with sustainability goals shows the way organizational needs to tackle the environmental and social goals are integrated into the overall mission, which enhances the legitimacy and commitment of employees (Sethi et al., 2017). AI synergy refers to the level of knowledge of artificial intelligence technologies among employees, which has become one of the major predictors of job satisfaction and well-being (Jarrahi, 2018). Thoughtful work design helps maintain focus and reduce stress, and learning agility helps employees quickly adapt to change and drive innovation (Bedford, 2019).

1.3. The Need for an Integrative Framework

Although individual workplace resources such as autonomy, inclusivity, and learning agility have received significant scholarly attention, the literature fails to provide a comprehensive framework wherein the above factors as well as the new ones, including AI synergy and wellness technology, are incorporated into a single model that can explain employee as well as organizational outcomes. The resulting lack of synthesis is a significant gap. Each of the factors has been historically studied on an empirical level, thus limiting our current knowledge of their potential to be combined and provide a disproportionate impact when combined. Also, there are considerable intervening and contextual processes that are poorly explored. Although constructs like engagement and vitality have been shown to exert a mediating influence on resource performance connections in a fragmented manner, the dual mediation of work resonance and employee vitality has not been investigated in a rigorous manner. Similarly, the well-being of employees is often considered as a result, but not a moderator. There is limited empirical research into the existence or absence of the amplification or attenuation effects of well-being on the effect of resource bundles on performance. These gaps in the methodology highlight the significance of the current study, which investigates the contribution of an overall set of modern organizational resources, denominated Employee Experience Capital, to sustainable organizational performance as a result of the interactive effects of work resonance and vitality at different degrees of employee well-being.

1.4. Research Gaps and Needs

Although studies acknowledge the role of autonomy, inclusivity, digital tools, sustainability orientation, and wellness practices in shaping engagement, three important gaps persist:

- G1—Resource Bundling: Few studies conceptualize or empirically test a higher-order reflective construct that integrates digital, sustainable, inclusive, AI-enabled, mindful, and wellness dimensions into one resource system.

- G2—Transmission Logic: Dual, complementary psychological mechanisms—resonance (alignment and meaning) and vitality (energy and self-regulation)—are rarely examined together as simultaneous mediators between resources and performance.

- G3—Boundary Role: Employee well-being is generally considered only as a consequence; however, the possibilities of its potential role as a boundary condition defining the efficacy of resonance and vitality are, however, yet to be investigated in the existing theoretical literature.

1.5. Theoretical and Practical Significance

High-Performance Work Systems (HPWSs) and Psychological Capital (PsyCap) remain the most used systems to explain the outcomes of employees. However, an HPWS predicts managerial human-resources-linked practices such as recruitment, training, and reward systems whereas PsyCap predicts the psychological characteristics of the individual such as hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism. Neither of the constructs can sufficiently respond to the cross-domain integration of digital, sustainable, and wellness-based resources characteristic of the hybrid, AI-enabled organizations of today. Employee Experience Capital (EEC) goes a step further and puts forward its own perspective, namely, as a second-order, organization-level construct that integrates both socio-technical and psychosocial resources into the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) and Resource-Based View (RBV) frameworks. In terms of concept, EEC is opposed to HPWSs since it integrates digital autonomy, inclusivity, and well-being technologies as fundamental job resources instead of using managerial practices. Similarly, it builds on PsyCap by modifying the focus of attention to structural, experience-making resources provided by the organization. This repositioning defines EEC as a unique and new theoretical model that replicates how integrated resource systems initiate resonance, energy, and performance. Practically, the EEC lens can provide managers with a roadmap that is measurable to integrate technology, sustainability, and wellness programs and ensure that employee experiences translate into performance realities.

1.6. Objectives and Hypothesis Overview

The current research will investigate the relationship between Employee Experience Capital (EEC) and organizational performance by the two mediators of work resonance and employee vitality and the moderating role of employee well-being. The investigation will be carried out based on the assumptions of the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) and Resource-Based View (RBV) frameworks and answer the following research questions:

RQ 1: What is the effect of Employee Experience Capital on improved organizational performance in digitally intensive workplaces?

RQ 2: Does the relationship between EEC and organizational performance mediate work resonance and employee vitality?

RQ 3: How is the mediating relationship between vitality and resonance in the performance outcomes mediated by employee well-being?

RQ 4: How can the integrative EEC–resonance–vitality–well-being model be applied to inform sustainable human capital strategies in the AI-driven and wellness-oriented organization?

The objectives of this study are fourfold: (1) to investigate how the seven drivers of Employee Experience Capital contribute to shaping work resonance and employee vitality; (2) to analyze the effects of Employee Experience Capital on organizational performance; (3) to evaluate the dual mediating roles of work resonance and employee vitality in linking the drivers of Employee Experience Capital with organizational performance; and (4) to assess the moderating role of employee well-being in the relationship between the mediators (work resonance and employee vitality) and organizational performance. Based on these objectives, five hypotheses are proposed and tested in the subsequent sections.

1.7. Clarification on Scope and Construct Selection

Previously conceptual versions of this framework included Green Brand Love (GBL) as an attitudinal outcome between sustainability value and the identification of employees. But later in the model refinement process, both theoretical and methodological reasons led to the removal of the construct. The initial empirical convergence tests showed that GBL has a high level of conceptual overlap with work resonance. Both denote the congruency of personal and corporate values; however, resonance is a broader experience level that includes the congruency of personal and corporate values in a broader way than just egocentric affection. Second, it becomes essential since the main unit of analysis of the study is not consumer–brand attachment but rather the inner psychological mechanism of the employee. Keeping GBL would thus have mixed internal and external relationships levels. Based on this, the updated model relies on Employee Experience Capital (EEC) as a resource system which promotes both resonance and vitality moderated by well-being to predict the organizational performance. The boundary clarification makes the theoretical precision more precise but at the same time does not refute the notion that value-based affinity constructions like GBL will continue to have a role in future studies and will be able to connect sustainable employer branding to employee outcomes.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital Detox Autonomy

Early work established that autonomy is a core motivator and driver of intrinsic satisfaction. Longitudinal investigations have found that technology functioning as a resource combined with autonomy predicts higher sustained engagement under remote work conditions (Marsh et al., 2024). Reviews indicate that digital autonomy positively influences innovative work behavior when employees are digitally competent (Hair et al., 2019). Higher autonomy has been linked with lower stress and reduced privacy concerns, showing that it acts as a buffer (Reb et al., 2014). Digitalization tends to enhance job autonomy, particularly in decision-making and workload allocation (May et al., 2004). However, algorithmic monitoring and surveillance technologies constrain autonomy (Lombardo & Eichinger, 2000). In AI-augmented workplaces, restricting choices in AI support reduces perceived autonomy and meaningfulness even when decision performance improves (Lombardo & Eichinger, 2000). Empirical associations between AI use and autonomy suggest that it must be considered in AI contexts (May et al., 2004). Studies in globally distributed teams show that autonomy matters but only when paired with competence and relatedness (Sennott & Stewart, 2025). Reviews of remote work emphasize autonomy as a psychological need fulfilled via digital control in remote settings (Yu et al., 2023). Taken together, these works show a strong basis for digital autonomy as a resource. More recent work recognizes it as a strategic driver in digitally transformed workplaces, integrating it into models of Employee Experience Capital, but few have empirically tested its joint influence along with other digital, sustainability, and wellness resources (Ryan & Frederick, 1997).

2.2. Neurodiversity-Inclusive Cognition

Psychological safety enables individuals to express divergent viewpoints, which is a prerequisite for inclusive cognition (La Torre et al., 2019). Inclusion conceptualized as both belongingness and uniqueness lead to higher performance (Lee et al., 2021). Climates of inclusion predict stronger employee engagement and reduced turnover (Lee et al., 2021). Evidence shows that inclusive leadership strengthens well-being and vigor in hybrid workplaces (Guerci et al., 2016). Diverse teams outperform homogeneous ones when inclusive processes support information sharing (Salanova et al., 2019). Recent studies confirm the idea that inclusive thinking advances equity and has a direct impact on shared intelligence and innovation (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). Cognitive-level inclusivity helps to promote innovativeness in cross-cultural teams (Garcia-Cabrera et al., 2022). Inclusion transcends the demographics to include cognitive perspectives (Lopez et al., 2020). Workers with neurodiversity in inclusion settings are more creative and more satisfied with their jobs (Schaufeli et al., 2002). More current research emphasizes the fact that inclusive thinking is becoming a strategic organizational asset in organizations that go through the process of digital transformation (Sennott & Stewart, 2025). However, it has not been incorporated frequently in combination with other drivers like digital independence, AI synergy, or wellness technology to foresee organizational outcomes, and has therefore left a void of comprehensive structures of Employee Experience Capital (Yu et al., 2023).

2.3. Sustainability Alignment

Employees who identify with sustainable practices demonstrate more organizational commitment and pro-environmental citizenship behaviors (Shirom, 2004). Agreement to sustainability goals by employees results in better environmental management systems (Henseler et al., 2015). Green HR practices enhance the attitude and retention of employees (Tiru et al., 2021). Perceived corporate social responsibility enhances the recognition of organizational values by employees (Pratt & Ashforth, 2003). The environmental behaviors of employees increase when the organizational culture facilitates sustainability (Shore et al., 2011). The kind of relationship between environmental management and employee outcomes is mediated by Green HRM (Kline, 2016). Leadership plays a role in passing sustainability values to employees (Van Doorn et al., 2017). HRM practices are sustainable, thus enhancing trust and engagement (Nielsen et al., 2017).

More recent studies have pointed out that the alignment of sustainability has been progressively recognized as a strategic internal force of performance as opposed to an extrinsic legitimacy mechanism (Edmondson, 1999). However, the literature has rarely combined the concept of sustainability alignment with new aspects, including AI synergy, wellness technology, or technology digital autonomy, to define how values-based practices in collaboration with technology affect employee outcomes, which indicates the existence of a research gap (Edmondson, 1999).

2.4. AI–Human Synergy Comfort

Artificial intelligence can serve as an assistant to human decision-making but not to substitute it (Paille & Raineri, 2015). Companies that integrate human intelligence with machine intelligence are more prosperous (Paille & Raineri, 2015). AI is more acceptable to employees when it is applied to augment tasks as opposed to automation. Clear AI interfaces enhance faith and cooperative effectiveness (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). Longitudinal data indicate that satisfaction with AI technologies grows with job and life satisfaction in cases when synergy and not substitution are observed (Daily & Huang, 2001). The introduction of AI transforms the organization of tasks and affects the well-being of employees (Dragoni et al., 2014). By combining AI and human-centric design operations, innovation is more likely to work. Empirical evidence shows that the adoption of AI affects job satisfaction and engagement through task restructuring (Cotten & McCullough, 2020). Human and machine collaborative intelligence presents novel functions and improves performance (Reb et al., 2014). Recently, it was reported that employees utilized AI tools significantly more than managers anticipated, which suggests the necessity of frameworks that recognize the existence of human–AI collaboration as both a psychological and technological influence (Sadeghi, 2024). In spite of these developments, there are limited studies that have incorporated AI synergy and other job capabilities like digital autonomy, mindful design, or wellness technology in the same model of Employee Experience Capital, and this represents a significant gap in research (Cotten & McCullough, 2020).

2.5. Mindful Design

The need to find meaningful work to maintain employee engagement and provide the foundation for purposeful job design is undeniably clear (Salanova et al., 2019). Evidence-based practice testifies to the fact that a combination of mindful work practices produces a reduction in burnout and an increase in vitality (West et al., 2019). Furthermore, it has been shown that mindfulness is predictive of improved emotional control and high performance at work (Onkila & Sarna, 2021). Mindfulness-based interventions can be used to emphasize and increase the concentration of employees (Spreitzer et al., 2005). The impact of leader mindfulness on the well-being and job satisfaction of their subordinates has been supported (Udayakumar & Nazeer, 2023). Job configurations where mindfulness factors are incorporated are linked to a decrease in absenteeism and turnover (Dumont et al., 2017). Workplace mindfulness facets have been strictly measured using validated psychometrics scales (Gering et al., 2025). Systematic reviews argue that a conscious job design paradigm enhances psychological safety in organizations (Dumont et al., 2017). Cognizant work design allows for levels of engagement to be raised by establishing resonance with the organization’s values at their core (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). Mindfulness-based job redesign is increasingly being recognized as an antidotal strategy to the ever-growing problem of attention fragmentation in digital working environments (J. Robertson & Barling, 2013). However, the empirical literature is limited in the discussion of how mindful design is integrated with other modern levers (digital autonomy, AI integration, or wellness technology) to provide a deeper understanding of its additive effect on employee vitality, resonance, and overall organizational performance. This gap provides the motivation for the current study (J. Robertson & Barling, 2013).

2.6. Learning Agility

This construct is one of the differentiators of the potential of leadership (I. T. Robertson & Cooper, 2011). It plays a vital role in designing adaptive leaders in turbulent situations (Jiang et al., 2012). It has been linked with resilience and sustainable employability among European workforces (I. T. Robertson & Cooper, 2011). It forecasts managerial performance even beyond cognitive capability and personality (Hülsheger et al., 2013). Learning-agile employees with good qualities will take feedback and developmental assignments on their own initiative and fast-track their career development. Learning agility controls the interdependence between the complexities of the job and innovation behaviors (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). Learning-agile individuals adapt better to organizational change projects (Jiang et al., 2012). Learning agility promotes the use of new technologies in digital transformation projects (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). Studies have shown that it is an indicator of flexibility and psychological security in remote work transitions (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). More recent research believes that it must be studied as a part of other emergent factors, including wellness technology or AI synergy, into one overarching model of Employee Experience Capital (Jiang et al., 2012). This disconnect warrants the need to look at it not as a single entity but as a component of a larger resource bundle that defines vitality, resonance, and performance (Jiang et al., 2012).

2.7. Wellness Technology

Well-being programs enhance the health and performance of employees (Huselid, 1995). Digital wellness programs assist workers in striking a balance between technology demand and mental health outcomes in remote work settings (Ryan & Frederick, 1997). Meta-reviews affirm that stress is substantially minimized, and resilience is improved with digital well-being interventions (Dragoni et al., 2014). Wellness and mindfulness apps enhance vitality and minimize absenteeism (Lee et al., 2021). Interventions based on mobile-based stress management have been shown to reduce psychological distress in employees (Lee et al., 2021). Digital health tools allow older employees to cope with technostress (Hair et al., 2019). The incorporation of wellness technology into HRM practices enhances engagement and reduces turnover (Pratt & Ashforth, 2003). Digital intervention reviews on occupational stress find that job demand wellness is supported by technology-based wellness (Reb et al., 2014). Workers using wellness applications on a regular basis have greater work–life balance satisfaction and proactive coping abilities (J. Robertson & Barling, 2013). More current data underscores the idea that wellness technology is being viewed more and more as a programmatic supplement and not as a structural part of Employee Experience Capital (Dragoni et al., 2014). However, not many studies have integrated wellness technology with other emerging drivers, such as AI synergy, mindful design, or learning agility, to describe the way resource bundles maintain employee vitality, resonance, and performance (Dragoni et al., 2014).

2.8. Work Resonance

Engagement can be defined as the interaction between the psychological presence of employees regarding the conditions of their role and their cognition of its resonance (Salanova et al., 2019). The concept of engagement at work, which refers to vigor, commitment, and absorption, is similar to the notion of alignment (Yadav & Pathak, 2025). Engagement is predicted by meaningfulness and safety, which is an indirect finding related to resonance (Salanova et al., 2019). The recognition of organizational values enhances discretionary effort, which is a major component of resonance (Dwivedi et al., 2021). Employee–employer value congruence is associated with an increase in well-being and a reduction in turnover (Kline, 2016). The effect is associated with job resources and enhanced by cultural alignment (Ebert et al., 2018). Significant work and identity processes bring more connectivity, which is a fundamental part of resonance (Spreitzer et al., 2005). Work resonance also adds to relational energy and enhances organizational commitment (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). Predicting greater identification and positive results is achieved by person–organization fit (Guest, 1997). Other more recent contributions suggest that resonance is seen by organizations undergoing digital and sustainability transformations to be a strategic mediator, where the translation of resource bundles into performance can be achieved by resonance (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). Nevertheless, there is a limited number of empirical investigations directly researching work resonance as a dual mediator along with vitality as a factor in a unified model of Employee Experience Capital, which points to a significant gap (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017).

2.9. Employee Vitality

Subjective vitality is a dynamic reflection of well-being and positive functioning (West et al., 2019). Vigor has been conceptualized as including physical strength, emotional energy, and cognitive liveliness (Van den Broeck et al., 2010). Job resources predict vitality, which in turn predicts work engagement and performance (Xanthopoulou et al., 2009). Recovery experiences during off-job time enhance vitality at the start of the next workday (Tiru et al., 2021). Thriving at work—a state combining vitality and learning—leads to increased proactivity and resilience (Van Doorn et al., 2017). Person–organization value fit fosters vitality and reduces burnout (Van den Broeck et al., 2010). Vitality mediates the relationship between supportive leadership and employee outcomes (Salanova et al., 2019). Relational energy from supervisors predicts higher vitality and better performance (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). Vitality functions as an energizing self-regulation resource enabling creativity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Organizations undergoing digital transformation are increasingly recognizing vitality as a strategic mediator linking bundles of job resources—such as digital autonomy, inclusive cognition, and wellness technology—to organizational performance (Nambisan et al., 2019). Yet few studies have examined vitality’s mediating role together with work resonance in an integrated framework of Employee Experience Capital, creating a significant research gap (Nambisan et al., 2019).

2.10. Employee Well-Being

Job features have been attributed to mental health and happiness (Huselid, 1995). A longitudinal study proves that psychological well-being is positively correlated with job performance (Huselid, 1995). Four dimensions of occupational well-being (affective, cognitive, and psychosomatic) have been combined in a multidimensional framework (Huselid, 1995). Autonomy and support are job resources that are associated with well-being through engagement (Xanthopoulou et al., 2009). Interventions that enhance well-being are effective investments that boost retention and productivity (Van Doorn et al., 2017). Coaching interventions enhance well-being and the achievement of goals, which reflects the plasticity of well-being (Molino et al., 2020). Reviews have deduced that employee well-being acts as a potential linkage between HR practices and outcomes (Shore et al., 2020). In digital work scenarios, well-being is a protective mechanism, enhancing positive processes and reducing risks of overload (Dillman et al., 2014). Perceptions of AI can affect the well-being and outcomes of employees, indicating that well-being mediates the effectiveness of the conversion of digital and AI resources into performance (P. M. Wright & McMahan, 2011). Regardless of this growing awareness, few empirical studies have empirically tested employee well-being as a moderating condition of two dual mediation processes including work resonance and vitality, which also presents a research gap that is filled by this study (P. M. Wright & McMahan, 2011).

2.11. Organizational Performance

Sustained competitive advantage is based on capitalizing on the valuable, rare, non-substitutable, and inimitable human capital (Etikan et al., 2016). The organizational capacity of HRM practices determines the attitudes and behaviors of employees that lead to organizational outcomes (Noll et al., 2020). HPWSs boost productivity and market value (Faas et al., 2024). The influence of HR practices on performance extends to employee behaviors (Van den Broeck et al., 2010). The linkages between HRM and performance differ in different institutional settings (Shirom et al., 2013). The value of bundles of HR practices is generated by human capital (Jarrahi, 2018). Training, selection, and compensation investments are predictive of low turnover and an increase in financial returns (Paauwe, 2009). Performance is enhanced by differentiated HR architectures that correspond to human capital types (Renwick et al., 2013). Meta-analyses affirm that HR practices influence organizational performance based on skills among employees, as well as motivation and opportunities (Porath et al., 2012). Organizational performance should be seen as a whole, whereby the well-being of employees and sustainable results are taken into consideration and not just financial performance (Shore et al., 2020). Theorists have gradually come to understand that Employee Experience Capital is converted into organizational performance via constructs such as work resonance, vitality, and well-being, yet little empirical evidence has examined such cumulative models (Shore et al., 2020). This model, by incorporating organizational performance as the dependent variable in this study, makes a contribution to the literature by integrating the current drivers, i.e., digital autonomy, inclusive cognition, sustainability alignment, AI synergy, mindful design, learning agility, and wellness technology, via mediating and moderating linkages, into a wide, employee-based understanding of organizational success (Shore et al., 2020).

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

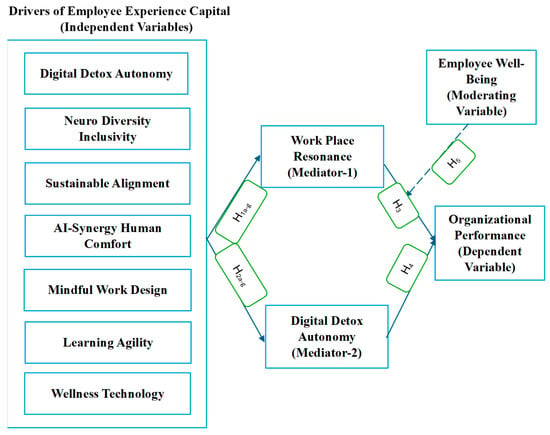

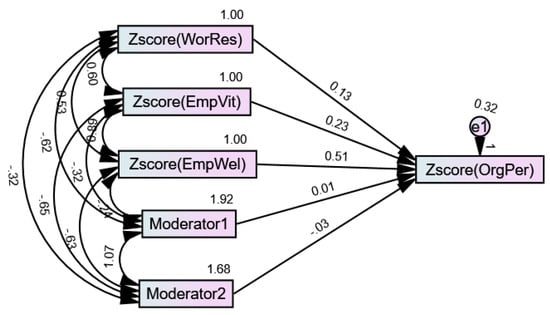

Grounded in Job Demands–Resources theory (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017) and the Resource-Based View of the firm (Barney, 1991), this study proposes a model (Figure 1) in which seven drivers of Employee Experience Capital—digital autonomy, inclusive cognition, sustainability alignment, AI synergy, mindful design, learning agility, and wellness technology—operate as interrelated job resources. These resources are theorized to shape two key psychological states—work resonance and employee vitality—which in turn influence organizational performance. Employee well-being is included as a boundary condition moderating the indirect effects. This integrative model extends prior research on job resources, psychological mechanisms, and performance (Edmondson, 1999; Shore et al., 2011; Daily & Huang, 2001; Jarrahi, 2018; Kahn, 1990; Lombardo & Eichinger, 2000; Danna & Griffin, 1999).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model adapted from Udayakumar and Nazeer (2023, Human Systems Management, DOI:10.3233/HSM-211593).

The model integrates the motivational pathway of the Job Demands–Resources (JD–R) theory and the value creation logic of the Resource-Based View (RBV). Through the JD–R lens, the seven EEC resources represent motivational job resources that stimulate resonance and vitality as positive work states. From the RBV standpoint, these resource bundles qualify as valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN) assets that generate a sustainable competitive advantage. The synthesis of both theories enables a coherent explanation of how EEC operates simultaneously as a psychological and strategic resource system.

This paper operationalizes Employee Experience Capital (EEC) as a second-order reflective–reflective latent construct that denotes an integrated set of workplace resources and not a set of independent variables. The seven first-order dimensions are digital autonomy, inclusive cognition, sustainability alignment, AI synergy, mindful design, learning agility, and wellness technology, which are interdependent job resources that create EEC together. This more advanced specification is consistent with the Job Demands–Resources theory, which focuses on the multiplicity of job resources working together to create motivation and positive results, and with the Resource-Based View, which views resource sets as helpful, scarce, and inimitable, non-substitutable assets that facilitate sustainable advantage. Under this hierarchical framework, work resonance and employee vitality are placed in a mediator role as state-like mediators that will direct the motivational and vital energy of EEC into higher performance and employee well-being in the role of a contextual moderator that can either reinforce or dampen these relationships. Lastly, the outcome construct is organizational performance, as it represents economic and psychosocial aspects of success. This hierarchy offers conceptual clarity, the separation of the functions of state-like and trait-like constructs, and a theoretical basis of the structural model, as demonstrated in Figure 1.

3.1. Direct Effects on Work Resonance and Employee Vitality

Prior studies show that autonomy, inclusive cognition, sustainability alignment, AI synergy, mindful job design, learning agility, and wellness technology each predict higher engagement, psychological safety, and positive affect at work. Therefore, the model predicts direct positive paths from each of these seven resources to both mediators.

H1.

The seven drivers of Employee Experience Capital (digital autonomy, inclusive cognition, sustainability alignment, AI synergy, mindful design, learning agility, and wellness technology) positively influence work resonance and employee vitality.

3.2. Effects on Organizational Performance

Because job resources and positive psychological states are linked to higher-level outcomes (Guest, 1997; Peccei & van de Voorde, 2019), the model also posits a direct effect of Employee Experience Capital on organizational outcomes.

H2.

Employee Experience Capital influences organizational performance.

3.3. Influence of Employee Vitality

Employee vitality reflects an energizing self-regulation resource enabling proactivity and creativity (Ryan & Frederick, 1997; Spreitzer et al., 2005) and is expected to have its own direct path to performance.

H3.

Employee vitality positively influences organizational performance.

3.4. Mediation Through Work Resonance and Employee Vitality

The middle section of Figure 1 shows work resonance and employee vitality as dual mediators. Work resonance captures the alignment between employees’ values and their organization’s purpose, fostering meaningfulness and relational energy (Pratt & Ashforth, 2003; Cable & DeRue, 2002). Together these states are expected to channel the effects of Employee Experience Capital toward organizational performance (Xanthopoulou et al., 2009; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004):

H4.

Work resonance and employee vitality mediate the relationship between the drivers of Employee Experience Capital and organizational performance.

3.5. The Moderating Role of Employee Well-Being

The right-hand side of Figure 1 positions employee well-being as a moderator. Evidence shows that well-being conditions how effectively digital and AI resources translate into performance (I. T. Robertson & Cooper, 2011; Frontiers in Public Health, 2025; Sadeghi, 2024). Therefore, the model predicts that the indirect effects through work resonance and employee vitality will be stronger for employees with higher well-being.

H5.

Employee well-being moderates the relationship between the mediators (work resonance and employee vitality) and organizational performance, such that the relationship is stronger under higher levels of well-being.

3.6. Organizational Performance

Organizational performance is conceptualized broadly, incorporating both economic and psychosocial outcomes in line with recent calls to link HRM, well-being, and sustainability (Guest, 1997; Peccei & van de Voorde, 2019). By testing this integrated model, the study contributes to understanding how contemporary job resources combine with psychological mechanisms to drive sustainable organizational success.

3.7. Research Gap

Although extensive research has documented drivers of an organization at the workplace, including autonomy, inclusiveness, and learning agility, most research has characterized each of these drivers individually, thus failing to consider how the combination of the three factors forms a cohesive construct of Employee Experience Capital. As an example, engagement and intrinsic motivation have been connected to autonomy (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Marsh et al., 2024), psychological safety and well-being to inclusivity (Edmondson, 1999; Contreras et al., 2020), and alignment to sustainability and to organizational legitimacy and pro-environmental behaviors (Sethi et al., 2017; Onkila & Sarna, 2021). Nevertheless, there are only a limited number of studies that combine these multifaceted dimensions with emerging factors, including AI synergy (Jarrahi, 2018) and wellness technology (Marsh et al., 2024) into an overall framework that can explain how these approaches, in turn, affect the outcomes of employees. This division creates a gap in the comprehension of the systemic interaction among several contemporary drivers of the workplace and how they affect organizational performance, as well as the dual mediating role of work resonance and vitality of employees, which has not been adequately addressed (Xanthopoulou et al., 2009). The possible moderating role of employee well-being has also been underused in existing research and has been recognized as an outcome, as well as an important work resource (T. A. Wright & Cropanzano, 2000). Existing research has a propensity to isolate the results of well-being and performance, which restricts theoretical development. The holistic model that incorporates Employee Experience Capital, dual mediation processes, and the moderating role of well-being vis-a-vis organizational performance is thus yet to be found, and is a main gap in theory as well as practice.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design and Approach

A quantitative, cross-sectional survey was adopted in this study to empirically test the proposed conceptual model and establish how and how often multiple employees’ experiences regarding capital resources correlate to organizational performance, using the two forms of mediating and moderating relationships. A questionnaire was distributed to full-time workers in organizations that were in the process of undertaking online digital transformation and sustainability efforts. The use of a cross-sectional approach is justified by the fact that this methodology allows for the estimation of direct, indirect, and moderated effects between a wide range of variables at once, which is suitable when it is necessary to explore bundles of job resources and psychological processes in the workplace (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Podsakoff et al., 2012).

4.2. Participants and Sampling Strategy

The target population was composed of mid-level and senior professionals working in industries that involved frequent interaction with artificial intelligence (AI) and workplace wellness technologies and business practices focused on sustainability. These were information technology, financial services, manufacturing, and higher-education organizations. Those contexts were chosen as they proactively implement digital transformation and well-being programs, therefore providing high construct relevance to Employee Experience Capital, vitality, and well-being.

To ensure heterogeneity in terms of industries and at the same time ensure that the sampling was in line with the conceptual focus of the study, a purposive-stratified sampling method was adopted (Etikan et al., 2016). Inclusion criteria were that the respondents must have had a year of tenure in their current organization and had firsthand experience with digital instruments or sustainability initiatives in their day-to-day operations.

As per the suggested principles of structural equation modeling, at least 15–20 observations were aimed at every single parameter to be estimated (Hair et al., 2019; Kline, 2016). The sample size of about 612 respondents was therefore designed to offer a sufficient level of statistical power and strong estimation of parameters. The data collection process was conducted in January–April 2025 based on a mixed online-and-offline approach.

The participants were approached through organizational human resources departments, professional associations, and LinkedIn networks. Every invitation contained a safe survey contact, a description of the reason why the research was conducted, and guarantees of confidentiality and the voluntary nature of the responses. Informed consent was conducted electronically before the beginning of the surveys, and no personally identifiable data was gathered, except basic demographic attributes, to maintain anonymity (Dillman et al., 2014).

The number of questionnaires that were retained following completion, response bias, and outlier screening in the 612 total responses was 590. The obtained sample was above the minimum requirements of SEM and was a representative sample with equal demographic and industry distribution between males and females and with good generalizability of the findings. Each of the operations was followed by institutional ethical review approval and by the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) declaration on research participation by human subjects. The full questionnaire is provided in Appendix A. The measurement items are listed in Appendix B. The ethical approval letter is included in Appendix C.

4.3. Survey Instrument

A structured online questionnaire was used in collecting data for the specific purposes of this study. The tool included an introduction, which covered the aim of this study, a guarantee of confidentiality, and voluntary participation; a body section, which entailed multi-item statements that assessed each construct of the conceptual model; and a brief demographic section. The rating of all the substantive items was on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), with a higher score indicating greater support of the underlying construct (Likert, 1932). The items for the independent variables (digital autonomy, neurodiversity-inclusive cognition, sustainability alignment, AI–human synergy comfort, mindful design, learning agility, and wellness technology) and the moderator (employee well-being) were based on previously tested scales and digitally transformed workplaces. The items for the dependent variable (organizational performance) were what had been tested before (see Supplementary Materials for the full dataset). A pilot test was conducted on 30 participants of the target population to test the questionnaire in terms of clarity, internal consistency, and time to complete the survey, and a few words were edited (Saunders et al., 2019). The last survey took about 12–15 min to fill out and was made available on the Internet through a secure system to eliminate the possibility of duplication of responses and guarantee anonymity.

4.4. Data Collection Procedure

The information was gathered in six weeks. An online survey was conducted on a secure platform that does not support any duplications of the same survey, and the respondents could complete the questionnaire at their own convenience through their desktop or mobile phone. Two reminder messages were sent after two weeks to enhance the rate of responding. Everything was performed in adherence to the ethical principles of the institutional review board of the respective institution of the author (Babbie, 2020).

4.5. Data Analysis Plan

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS (v31) for preliminary screening and AMOS for structural equation modeling. Descriptive statistics summarized the demographic characteristics of the sample. Internal consistency reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (Cronbach, 1951; Hair et al., 2019). Convergent validity was examined via average variance extracted, and discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion and heterotrait–monotrait ratios (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Henseler et al., 2015).

The hypothesized model was tested using SEM with maximum likelihood estimations. Direct effects of the seven independent variables on work resonance and vitality were estimated first. The dual mediation of work resonance and vitality was then assessed using bootstrapped confidence intervals for indirect effects (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Employee well-being moderation was tested by the inclusion of the interaction term between the moderators and the moderator. The model fit was assessed based on several indices, such as comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and in accordance with the acceptable model fit and diagnostic thresholds (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2016). Other possible explanations were controlled by introducing control variables like age, gender, and tenure.

4.6. Ethical Considerations

The ethics committee of the host institution was consulted in order to give ethical approval before data was collected. Every participant received information about the aim of the research, the voluntariness of their participation, and the possibility to leave the research without any penalties. All data was stored safely and was reported in an aggregate manner to safeguard participant anonymity.

5. Results

5.1. Sample Characteristics

Table 1 outlines the demographic picture of the respondents. The age distribution indicates that employees in the 20–30 age group constitute younger employees, and the proportions gradually decrease in the older age groups. The gender distribution is rather balanced, though slightly biased towards males; the share of respondents who self-identify as female is large, whereas the representation of other or unspecified genders is marginal. With regard to education, most of the participants have undergraduate or postgraduate degrees, with a comparatively smaller number of people having doctoral or professional degrees, thereby showing a well-educated workforce as a whole. The information about marital status indicates that most of the respondents are single, with smaller proportions saying that they are married, divorced, or non-specified.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of respondents (n = 588).

The occupational range of the sample is a wide one, but the largest group comprises entry-level or junior employees, the next comprises middle-level and senior management, and a small proportion comprises those at the executive or director level. With respect to professional experience, the majority of the participants have less than one to three years of experience in their specific fields, while minor subgroups have medium-to-long-term experience, hence constituting a relatively young and early-career group.

Divided by sector, the respondents are in the IT/telecommunications, healthcare/education, banking/finance, or manufacturing or other industries, hence establishing heterogeneous organizational settings for this study.

The nature of the organization indicates that the highest percentage of employees are in the public sector, followed by private and multinational corporations, and lastly start-up or non-governmental organizations. In relation to the modality of work, the hybrid modality is the most common, with fewer participants working remotely, on-site, and on a freelance/contractual basis. Finally, the distribution of income indicates that most of the respondents fall under the lower-to-middle salary brackets, with a steadily declining number falling in the upper income category. Truthfully, these demographic factors illustrate a diverse but mostly young, educated, and hybrid-working sample, which, in harmony, resonates with the modern-day organizational environment.

5.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis of the Constructs

Table 2 shows the reliability and validity ratings of all the constructs that are utilized in the current study. Internal consistency was measured using Cronbach’s alpha, and the coefficients obtained were greater than the traditional 0.70; hence, it confirmed good reliability. Furthermore, the level of composite reliability (CR) of all the constructs was more than 0.80, which is the requirement for good construct-level reliability. The mean variance extracted (AVE) was larger than the minimum acceptable value of 0.50 across constructs, and it speaks to sufficiently convergent validity.

Table 2.

Reliability and validity analysis (n = 588).

Combining these diagnostics, it is possible to state that the measurement model can be characterized by strong internal consistency and convergent validity. In turn, the operationalization of each of the latent constructs, along with digital autonomy, inclusive cognition, and sustainability alignment to work resonance, employee vitality, and organizational performance, was performed at a high level of reliability, which adequately reflected the variability of the indicators of each construct to support the integrity of subsequent structural analyses.

Table 3 provides the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) coefficient of sampling adequacy and the Bartlett test of sphericity of the variables utilized in this study. The KMO estimate exceeded the traditional cut-off of 0.80, which means that the inter-correlation matrix was homogeneous enough to justify the extraction of factors and that the sample that was used was sufficient to undergo the factorial procedures suggested. The result of Bartlett’s test of sphericity was very significant; hence, it was possible to discard the hypothesis of the identity structure of correlation and prove that the correlation between the items was strong enough to warrant the use of the confirmatory factor analysis on the measurement model.

Table 3.

KMO Bartlett’s Test.

The loading of factors on each of the latent constructs is reported in Table 4, where the measurement items are arranged on their respective latent constructs. All indicators have significant loadings to their underlying factor, with coefficients exceeding the traditional cut-off rates, hence establishing satisfactory convergent validity. The insignificance of the cross-loadings only contributes more to the argument that the items clearly measure their intended constructs without any major overlaps.

Table 4.

Factor loadings.

Taken together, these results prove that the measurement model has a strong and clear structure as concerns the factors. Everything fits very well within their hypothesized dimensions, which, in turn, means that the modified scales are appropriate to the current setting and provide a reliable basis for future structural equation modeling.

5.3. Structural Model Results (Direct Effects Testing H1–H3)

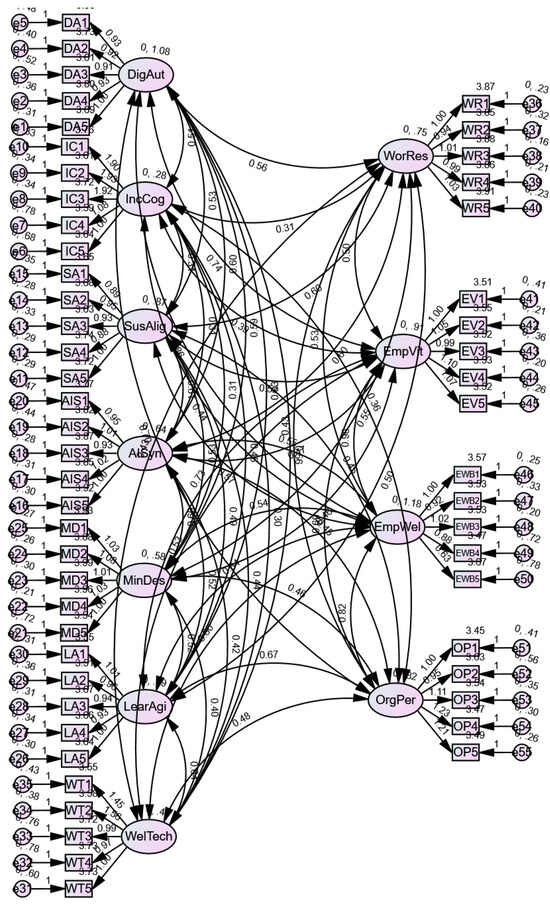

5.3.1. Measurement Model (CFA)

Table 5 reports the diagnostic fit indices for the measurement framework derived from confirmatory factor analysis. All indices exceeded or met their recommended thresholds, indicating a well-fitting measurement model. The χ2/df ratio was below the cut-off of 3.00, suggesting acceptable parsimony. Both the comparative fit index (CFI) and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) were comfortably above 0.90, and the goodness-of-fit index (GFI) and adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) also met the recommended standards, demonstrating robust global fit.

Table 5.

Diagnostic fit statistics for the measurement framework derived from confirmatory factor analysis.

Figure 2 shows that additionally, the parsimony normed fit index (PNFI) surpassed 0.50, showing a good balance between model complexity and explanatory power, while the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was below 0.08, indicating a close fit of the model to the data. Collectively, these results confirm that the measurement framework has strong psychometric properties and is suitable for testing the hypothesized structural relationships in the next stage of analysis.

Figure 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis of the eleven latent constructs showing standardized factor loadings and inter-factor correlations.

5.3.2. Discriminant and Construct Validity

Table 6 contains the Fornell–Larcker discriminant validity matrix, with the square roots of the Average Variance Extraction (AVE) conspicuously written along the diagonal. It is evident that all the diagonal items outperform the inter-construct correlation of those, thus validating the Fornell–Larcker test as introduced by (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). This empirical pattern enlightens us about the fact that every construct has a higher shared variance with their respective indicators than any other latent variable and therefore supports the discriminant distinctiveness of Employee Experience Capital, work resonance, employee vitality, well-being, and organizational performance. The moderate correlations that were identified between these constructs indicate theoretical interrelations, but at the same time, that multicollinearity is insignificant. A combination of these results supports the notion that the measurement model has high levels of convergent and discriminant validity, which justifies the adoption of the latent architecture of constructs for future structural studies.

Table 6.

Fornell–Larcker discriminant validity matrix (AVE values on the diagonal).

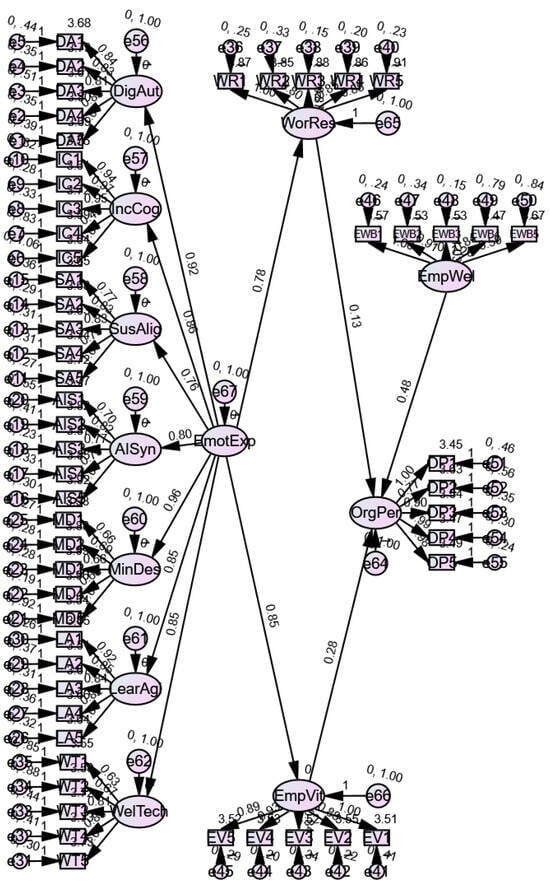

5.3.3. Structural Model (SEM)

The goodness-of-fit statistics of the hypothesized structural path model are summarized in Table 7. The reported indices were all within or exceeded the recommended thresholds, which confirmed that the structural framework proposed has sufficient fit to the data. The χ2/df value was less than the usual cutoff of 3.00, which indicates satisfactory model parsimony. Incremental fit measures, namely the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), had values comfortably above the 0.90 cut-off, and the Goodness Fit Index (GFI) and Adjusted Goodness Fit Index (AGFI) also met the required standards, all confirming a strong global fit.

Table 7.

Goodness-of-fit indicators for the hypothesized structural path model.

The parsimony normed fit index (PNFI) exceeded 0.50, reflecting a good balance between model complexity and explanatory power. Both the RMSEA and SRMR values were below 0.08, suggesting a close approximation of the model to the observed covariance matrix. Taken together, these results provide strong evidence that the hypothesized structural path model exhibits satisfactory psychometric adequacy and is suitable for testing the direct, indirect, and moderating relationships specified in this study.

Table 8 shows the path coefficient estimates and test statistics of the direct effect of the specified structural model. The direct relationship between all the hypotheses was positive and statistically significant, which gives solid empirical evidence for the proposed frameworks. Figure 3 shows that the composite of the seven resource drivers presented a significant positive impact on the first mediator since it had a high standardized coefficient and a considerably high t-value above the critical value. It also had an overwhelming positive impact on the second mediator, thus confirming that all these resources collectively revitalize the two aspects of the employee experience.

Table 8.

Estimated path coefficients and test statistics for direct effects within the proposed model.

Figure 3.

The structural equation model presents strong direct and indirect linkages between the study constructs, and standardized coefficients are reported.

The model also indicated that the composite resource drivers explained the outcome variable directly with a medium but significant influence, thus showing that the resource bundle had direct effects on organizational outcomes besides its indirect channels. Lastly, the second mediator significantly forecasted the outcome variable, meaning vitality is one of the mechanisms that transform resource bundles to performance outcomes. These aggregated findings justify the conclusion that all the direct paths defined in the model are supported and justified the theoretical propositions behind H1 through H3, providing a strong base for testing their mediating and moderating effects in further analysis.

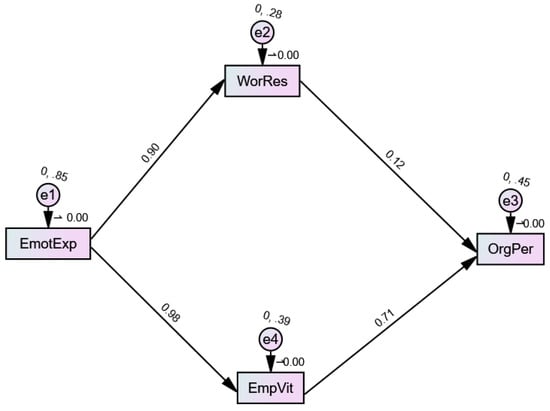

5.4. Mediation Analysis

Figure 4, Table 9 reports the bootstrapped indirect effects of the proposed mediators on the outcome variable. The indirect path from the resource bundle through the first mediator to the outcome was statistically significant, but of small magnitude, indicating that this channel exerts only a modest influence on performance. By contrast, the indirect path through the second mediator was highly significant and of strong magnitude, showing that this channel serves as a much more powerful conduit linking the resource bundle to organizational outcomes.

Figure 4.

Illustration of the dual-mediation mechanism of work resonance and employee vitality between Employee Experience Capital and organizational performance.

Table 9.

Bootstrapped indirect effects of work resonance and employee vitality on organizational performance (H4).

The combined indirect effect of both mediators was also large and significant, confirming the dual-mediation mechanism proposed in the model. The 95% confidence intervals for all indirect effects excluded zero, providing robust evidence of mediation. These results support H4 and demonstrate that the hypothesized mediators jointly explain a substantial portion of the relationship between the resource drivers and the outcome variable.

5.5. Moderation Analysis

Figure 5 The non-significant moderation effect suggests that employee well-being functions more as a direct contextual resource rather than as a boundary condition in this dataset. Theoretically, this aligns with the JD–R proposition that certain resources exert both enabling and outcome roles. In environments where general well-being levels are already high, its marginal moderating influence may diminish. This insight refines the framework by identifying well-being as a stabilizing contextual enabler rather than an amplifying moderator.

Figure 5.

Latent interaction moderation analysis showing the stable relationship between mediators and organizational performance across levels of employee well-being.

Table 10 presents the results of the moderation analysis examining whether employee well-being conditions the effects of the two mediators on the outcome variable. All main effects were positive and statistically significant, indicating that both mediators and the moderator independently contribute to higher levels of the outcome. However, the interaction term between the first mediator and employee well-being was not significant, and the interaction term between the second mediator and employee well-being was also non-significant. The 95% confidence intervals for both interaction coefficients included zero, confirming the absence of moderation.

Table 10.

Conditional interaction effects on outcome variables in the proposed model.

Taken together, these findings show that although employee well-being has a direct positive association with the outcome, it does not significantly amplify or dampen the effects of the mediators on performance. This pattern suggests that the benefits of the mediators on organizational performance are relatively stable across different levels of employee well-being. Consequently, H5 was not supported within this dataset.

6. Discussion

The results of the empirical findings support the motivational trajectory identified by the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model and highlight the idea that aggregated workplace resources, namely Experiential and Economic Capitals (EECs), act in a proactive manner to promote work resonance and vitality, which are two of the key job-related affective states. At the same time, using the Resource-Based View (RBV) paradigm, the causal relationships between EEC and organizational performance have been empirically supported, which supports the idea that integrated and experience-based resources serve as a strategic source of human capital, thus creating a sustainable competitive advantage.

6.1. Overview of the Main Findings

The current study was aimed at empirically questioning how a collective of modern workplace resources, all of which are referred to as Employee Experience Capital, can be translated into organizational performance through two intervening and modulating mechanisms. Specifically, the theoretical model assumed that seven drivers, including digital autonomy, inclusive thinking, sustainability alignment, AI–human synergy comfort, mindful design, learning agility, and wellness technology, would have a positive influence on two primary psychological conditions: work resonance and employee vitality. These states, in turn, were supposed to improve organizational performance. Also, the moderating effect of the relationship between the mediators and the performance was theorized to be higher at higher levels of employee well-being.

The hypothesized direct and indirect pathways were mostly supported by empirical data. The interaction of the seven drivers had a significant positive effect on both the mediators but a stronger effect on vitality than resonance. These findings highlight that Employee Experience Capital is not an abstract or diffuse concept but a measurable set of job resources capable of energizing employees in two complementary ways, the development of a sense of connection and alignment (resonance) and the provision of the psychological energy required to engage in proactive behaviors (vitality). Besides these indirect effects, the resource bundle showed a high direct effect on organizational performance, indicating that some benefits are realized through processes other than mediators. More importantly, employee vitality per se showed a strong positive impact on organizational performance, serving as a crucial indicator of the role of employee vitality as a self-regulatory resource that connects the state of affairs in the workplace with performance.

On the other hand, moderation analysis failed to support the hypothesis that organizational performance is magnified by employee well-being in the presence of work resonance or vitality. Even though employee well-being also had a substantial main effect on performance, and thus confirmed its position as an important standalone outcome and resource, the terms of interaction did not turn out to be significant, and the conditional effects were not variable at different levels of employee well-being. This tendency suggests that well-being, though a positive factor, might not have necessarily changed the magnitude of the causal relationships between resonance or vitality and performance in the studied sample.

Collectively, these results are a strong indication of the central role of Employee Experience Capital and mediating processes, as well as the narrow scope of understanding the boundary conditions within which the relationships are occurring. We recommend that further studies be conducted to clarify other avenues in which these resources can affect performance and also examine the situational domain that can precondition the mediating effect of employee well-being.

6.2. Interpretation of Direct Effects (H1–H3)

The strong direct effects found between Employee Experience Capital and the mediators of work resonance and vitality are the empirical measurements that support Hypothesis 1 and are consistent with the essence of the provisions expressed in the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model and self-determination theory. Employees facing high levels of autonomy, inclusion, alignment with sustainability imperatives, and helpful technological affordances are more likely to feel that they are experiencing a sense of meaning and alignment with their work (resonance), as well as a pulsating sense of energy and aliveness (vitality). These results build upon previous research by showing that the psychological conditions of interest cannot be attributed to the effect of a single resource or psychological state but are the combination of numerous and mutually enhancing resources. The findings also reinforce the emerging literature on resource bundles or capability bundles in the management of human resources, including that it is the combined practices that are more effective than individual interventions.

Hypothesis 2 indicates that, despite the lack of mediating processes, resource-rich environments perform better, although the relationship between the experience capital of the employees and the performance of the organization is direct. This process can occur since conducive environments boost not only individual vigor and congruency but also group activities like teamwork, creativity, and discretionary work, which, in turn, are directly converted into quantifiable performance indicators. The latter is consistent with resource-based views, which claim that human capital practices grant a sustainable competitive advantage when they are indeed valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable.

Hypothesis 3 regarding the tremendous direct impact of employee vitality on organizational performance supports the idea that vitality is a key process whereby job resources are transformed into performance. Vitality is theorized as an energy system that is self-regulating to maintain focus, persistence, and creativity in challenging environments. When employees feel vital, they are more active and stronger and ready to go a step further, beyond the expectations of their role in the organization, thus increasing organizational effectiveness. This conclusion intersects those of other prior studies that have linked subjective vitality to engagement, proactivity, and well-being in the workplace, but it adds to the existing body of research by drawing a picture of how vitality can be incorporated in both a wider, digitally oriented model and sustainability-infused resource model.

Remarkably, although work resonance had significant predicted performance in the bivariate analyses conducted, when vitality was added to the model, the effect of work resonance became mostly indirect. This is an indication that resonance is more of an influencer by virtue of making employees feel more energized and not necessarily a performance driver. An implication of such a distinction is that although both alignment and meaning are conditions for sustaining energy, it is the energized state (vitality) that drives performance behaviors the most.

6.3. Interpretation of Mediation (H4)

The mediating variables assessed in the mediation analysis were work resonance and employee vitality as mediators between Employee Experience Capital and organizational performance. The results strongly argue in favor of a two-mediation model. The indirect effect that was transmitted through vitality was large and significant whilst the resonance-mediated indirect effect, though significant, had a relatively small magnitude. Together, the total indirect influence was found to be statistically significant, indicating the supplementary nature of the psychological constructs to the significant amount of influence that the resource bundle has on performance outcomes. Such findings contribute to theoretical dialogue discourse in a number of relevant ways.

These results contribute to theoretical discussion in a number of ways. First, they support the thesis that modern work resources not only influence performance in the capacity to endow employees with capabilities or chances but also through the process of energization and psychological alignment. This is in line with the self-determination theory that states that the satisfaction of fundamental psychological needs creates a sense of meaning and energy, resulting in optimal functioning. Second, the findings build on the Job Demands–Resources literature by defining two complementary mediators, resonance, which reflects meaningful alignment, and vitality, which reflects energy and aliveness (as well as assessing them simultaneously in the same structural model).

The relatively high power of vitality as a mediator of performance as compared to resonance has theoretical significance. It indicates that the operationalization of performance behaviors is more related to an energized state even though alignment and meaning act as necessary antecedents. That is, employees would self-identify with organizational values but would still perform poorly in the face of a lack of vitality, and when vitality is coupled with alignment, performance will be at its best. This finding is consistent with thriving-at-work studies, which theorize thriving as the co-experience of learning and vitality and show that vitality is a more behaviorally operationalized dimension. By including both mediators, the current research is able to capture this subtlety and provide a deeper description of the way resource bundles become performance.

From a practical perspective, mediation outcomes suggest that interventions to boost the experience capital of employees should go beyond structural or policy-level changes (e.g., the implementation of digital tools or sustainability plans) to include programs that create vitality. Some of these are the design of tasks that offer recovery opportunities, include wellness technologies, and provide training on energy management. These strategies will help organizations to maximize the benefits of resource-abundant environments in the behaviors and performance outcomes of workers.

6.4. Interpretation of Moderation (H5)

The dual-path analysis provides strong data that the resonance of work and vitality of employees are two independent but complementary psychological processes in which Employee Experience Capital (EEC) enhances organizational performance. These outcomes of the mediation model prove that vitality produces stronger power, and energy and proactivity prove to be the main pathways through which resource-rich environments are converted into the best results. Resonance, in turn, serves a supporting purpose in that it develops alignment and meaning, which, in turn, indirectly renews vitality and maintains engagement throughout the length of time. All these processes demonstrate that EEC is not only a discrete collection of resources but also a logical motivational system that fosters alignment and energy at the same time, two essential elements of success at work.

Even though the affective qualities of employee well-being, vitality, and resonance have similar qualities of affectivity and motivational response, they exist at different levels of psychological functioning. Under the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) paradigm, well-being is treated as a higher-level personal resource that defines how these temporal states of experience transform into long-term consequences. Following the Self-Determination Theory (SDT), well-being increases the internalization of autonomy and competence, and thus enhances the overall positive effect of vitality and resonance on organizational performance. Therefore, by treating well-being as a moderator, as opposed to a mediator, the stabilizing effect of well-being on the strength of such state-based relationships without confusing their time frames or conceptual spaces is achieved.

The moderation analysis also explains the conditions of the boundary regarding this process. Employee well-being (WB) showed a substantial influence on performance but no significant change in the strength of the indirect connections between resonance, vitality, and performance. This trend suggests that the salutary effect of mediators is strong under varying states of well-being. In theory, WB describes a more sustained mental state, whereas resonance and vitality describe state-like experiences, which are directly linked to the immediate working situation. They overlap at the expense of moderation; the energizing and affective aspects of well-being are already within the context of vitality. In line with this, WB is a contributing factor to performance as an independent resource instead of a boundary variable.

These results can be narrowed to theoretical predictions based on the JD-R and SDT theories. They point out that the performance of augmenting bundles of job resources is mainly supported by internally generated meaning and energy as opposed to externally mediated well-being contingencies. In practice, this would imply that organizations need to create interventions that simultaneously resonate and activate both vitality, by helping organizations match work and purpose, by promoting inclusive and mindful practices, and by providing recovery opportunities, and well-being, by sustaining it as an indirect, parallel product. Further studies can examine alternative moderators such as leadership climate, team psychological safety, or resilience capacity to determine situations where the motivational pathways between resonance and vitality to performance are stronger or weaker.

6.5. Theoretical Contributions

The findings provide empirical confirmation of the JD–R model’s motivational pathway, demonstrating that bundled workplace resources (EEC) enhance work resonance and vitality—two critical job-related states. Simultaneously, from the RBV perspective, the confirmed paths from EEC to organizational performance validate the view that integrated, experience-based resources constitute a form of strategic human capital that yields a sustainable advantage.

The significant dual-mediation effects of resonance and vitality extend existing theory by specifying how resource integration translates into outcomes. Resonance reflects cognitive–affective alignment, while vitality embodies affective energy; together, they operationalize the transmission logic proposed by the JD–R and RBV models. Thus, this study advances theoretical integration by bridging micro-level psychological mechanisms and macro-level resource frameworks.

This research has a number of substantive implications for the behavioral sciences and the literature on human resource management in that it combines constructs represented by digital transformation, sustainability, and positive organizational psychology into a single explanatory framework. Firstly, this study goes beyond conventional one-resource models because it conceptualizes the experience capital of employees as a combination of seven modern drivers, including digital autonomy, inclusive cognition, sustainability alignment, AI–human synergy comfort, mindful work design, learning agility, and wellness technology. It directly reacts to calls by scholars to study resource caravans as opposed to resources in a job and therefore offers a more ecologically valid illustration of the contemporary workplace.

Second, this research introduces and empirically confirms work resonance as a mediator between the vitality of employees and work resonance. Although the concept of vitality has been well-researched as an element of success in the workplace, it has been found that the concept of resonance has remained mostly theoretical. Operationalizing resonance as psychological identification and the significance of resource-based work-related environments, this research paper provides the first empirical evidence of its involvement in transferring the benefits of resource-based Employee Experience Capital to business performance. This is an addition to the Job Demands–Resources paradigm, which traditionally focuses on motivational or health-protective mechanisms but not both at the same time.

Third, the results narrow down our knowledge about the relative salience of psychological mechanisms. Although the two mediators are important, the impacts of vitality are stronger, indicating that energy and aliveness have more proximal impacts on performance than alignment does. This subtly adds value to existing theories, suggesting that alignment can be a necessary but not sufficient antecedent, and vitality is the motivating stimulus that changes alignment into performance behaviors that can be observed.

Fourth, the lack of evidence on significant moderation by employee well-being runs against the existing hypothesis that all positive work processes are moderated by well-being. The findings reveal that in circumstances whereby psychological mediators already explain substantive amounts of the variance connected with well-being, further moderation effects could be insignificant. This requires a re-evaluation of the conceptualization and measurement of the employee resource and employee outcome models’ boundary conditions by researchers. It further highlights the need to differentiate between general traits like well-being and context-specific, state-like indicators in theorizing moderation effects.

Last, this research makes methodological contributions by proving that complex mediating models can be tested using large samples in digitally transformed workplaces. The combination of proven scales that have been adjusted to new environments and the application of structural equation modeling with bootstrapped confidence intervals are consistent with the best practices in the research of behavioral science and thus contribute to the strengthening of the results and their predictability.

6.6. Managerial and Practical Implications