Abstract

This study presents a comprehensive bibliographic and semantic analysis of 3957 scientific publications on artificial intelligence (AI) in government and public administration. Using an integrated text- and network-based approach, we identify the main thematic areas and conceptual orientations shaping this rapidly expanding field. The analysis reveals a research landscape that spans AI-driven administrative transformation, digital innovation, ethics and accountability, citizen trust, sustainability, and domain-specific applications such as healthcare and education. Across these themes, policy-oriented and conceptual contributions remain prominent, while empirical and technical studies are increasingly interwoven, reflecting growing interdisciplinarity and methodological consolidation. By clarifying how AI research aligns with governance values and institutional design, this study offers actionable insights for policymakers and public managers seeking to navigate responsible public-sector AI adoption. Overall, the findings indicate that AI-for-Government research is moving from fragmented debates toward a more integrated, implementation-relevant knowledge base centered on trustworthy and value-aligned digital-era governance.

1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is rapidly transforming the way governments design, implement, and evaluate public policies. From predictive analytics that enhance strategic foresight to conversational agents that support citizen interaction, AI technologies are increasingly embedded in the machinery of governance. These transformations promise significant gains in efficiency, transparency, and responsiveness, yet they also pose complex challenges related to ethics, legality, institutional accountability, and public trust. Governments at all levels local, regional, and national are thus confronted with the dual imperative of fostering innovation while safeguarding legitimacy and democratic values) (Kuziemski & Misuraca, 2020).

At the policy level, frameworks such as the EU Artificial Intelligence Act and the OECD AI Principles emphasize a risk-based approach to trustworthy AI, where transparency, explainability, and human oversight are preconditions for public sector adoption. Scholars of algorithmic accountability and digital-era governance (Margetts, Dunleavy, and others) further argue that AI governance must balance computational decision-making with institutional responsibility, ensuring that automation reinforces rather than replaces democratic deliberation. However, despite growing scholarly attention, the field of AI in government remains fragmented across disciplines public administration, data science, ethics, and political theory resulting in a dispersed and sometimes contradictory body of knowledge.

Recent reviews and bibliometric studies have substantially advanced understanding of AI in government by synthesizing governance frameworks, adoption trends, ethics, and regulatory developments. However, these works primarily rely on qualitative synthesis or citation/keyword-based mappings, which are less able to detect latent conceptual proximity across disciplines or to connect thematic structures with epistemic orientations. Building on this foundation, our contribution is threefold:

- (1)

- we map the AI-for-Government literature using semantic similarity between abstracts rather than citation or keyword co-occurrence;

- (2)

- we integrate community detection with HOMALS to reveal how thematic clusters align with policy/technical and conceptual/empirical orientations; and

- (3)

- we formalize these steps as a Semantic Community Method that is replicable for other interdisciplinary governance domains. To clarify the specific novelty of this manuscript relative to prior review and scientometric work, Table 1 summarizes key studies and highlights the distinct analytical value of our Semantic Community Method.

Table 1. Summary of prior review and bibliometric studies on AI in government/public administration and the gap addressed by this study.

Table 1. Summary of prior review and bibliometric studies on AI in government/public administration and the gap addressed by this study.

This study aims to address that fragmentation by conducting a comprehensive bibliographic and semantic mapping of the academic literature on AI in government and public administration. Rather than analyzing policy documents or regulatory texts, our focus is explicitly on peer-reviewed scientific publications, where theoretical and empirical contributions define the contours of the research field. We employ the Semantic Community Method, which integrates large language model (LLM) embeddings, network analysis, and multivariate statistics to uncover the field’s latent structure and conceptual orientations. This approach allows us to move beyond traditional citation analysis, revealing how ideas, methods, and governance perspectives coalesce into distinct thematic communities.

Despite rapid growth in AI-for-Government scholarship, we still lack a field-level map that simultaneously identifies (a) the semantic architecture of research themes and (b) the conceptual/empirical and policy/technical orientations that structure how knowledge is produced. Existing systematic reviews provide depth but are not designed to reveal large-scale latent connections across subfields, while conventional bibliometric techniques based on citations or keyword co-occurrence may underrepresent emerging or interdisciplinary linkages. Consequently, the knowledge base remains fragmented in ways that obscure how governance values, technical approaches, and empirical evidence co-evolve. To address this gap, we apply the Semantic Community Method, which integrates semantic similarity mapping, community detection, and HOMALS to produce a unified and interpretable picture of the AI-for-Government research landscape at a moment when the field is expanding and policy relevance is accelerating.

Accordingly, this paper is guided by three research questions:

- RQ1: What are the dominant conceptual and empirical orientations in the academic literature on AI-for-Government?

- RQ2: How do these orientations cluster into thematic communities, and what do they reveal about the evolution of the field?

- RQ3: How can semantic and network-based methods enhance the understanding of interdisciplinary knowledge architectures in AI governance research?

By addressing these questions, we contribute both conceptually and methodologically to the emerging discipline of AI governance studies. Conceptually, we illuminate how academic discourse reflects and shapes institutional responses to the digital transformation of the public sector. Methodologically, we demonstrate how semantic similarity and community detection can map interdisciplinary fields with precision and replicability. Together, these contributions offer a clearer, data-driven perspective on how governments and researchers are jointly redefining public administration in the age of algorithms.

2. Literature Overview

Research on Artificial Intelligence (AI) for government has grown from early explorations into opportunities and risks to more detailed frameworks that link technology with public institutions, values, and democratic principles. In the beginning, scholars focused on mapping what AI could mean for governments, often describing potential benefits and dangers in broad, conceptual terms. These early reviews highlighted the field’s growing ambitions but also warned that much of the work was still theoretical, with little real, world evidence. They pointed to serious issues such as algorithmic bias, data privacy, and the lack of accountability mechanisms (Reis et al., 2019; Valle-Cruz et al., 2019; Charles et al., 2022).

As research evolved, European case studies and broader analyses began to position AI as a form of digital or ICT, based innovation within government. These studies showed that AI’s success depends not only on technology and data but also on the social, organizational, and policy environments that support it. They found that AI is mostly used to improve service delivery and internal administrative processes, while much less often applied to direct policy design. This revealed an important distinction between governance of AI (regulating and guiding its use), governance with AI (using AI tools to support decision making), and governance by AI (where AI takes on an active role in policy implementation). The findings also emphasized that strong data systems alone are not enough, cultural readiness, institutional design, and leadership are equally critical (van Noordt & Misuraca, 2022a).

In recent years, the field has entered a stage of conceptual consolidation. Straub et al. (2023) proposed a unified framework to evaluate AI in government, based on three core ideas: operational fitness (how well AI performs its intended function), epistemic alignment (how well it fits with existing knowledge and expertise), and normative divergence (how it aligns with ethical and social values). At the same time, other reviews have called for more empirical, data, driven, and multidisciplinary research, work that connects theory with evidence from the public sector and evaluates actual outcomes. They stress the need for frameworks that can scale up as adoption grows and that can manage emerging risks responsibly (Charles et al., 2022; Zuiderwijk et al., 2021; Caiza et al., 2024).

Evidence is now emerging that shows tangible effects of AI on governance. For example, Zhao et al. (2025) used patent-based data from China and found that AI can increase government transparency through three main mechanisms: improving administrative efficiency, expanding open data practices, and building public trust. However, the impact varies depending on context, meaning that policy strategies must be adapted to local conditions. Similarly, a five-decade scientometric analysis of AI in local government revealed a sharp rise in the use of AI for decision support, automation, prediction, and service delivery. The study also pointed out that ethical and participatory aspects, such as how citizens are involved in AI governance, remain under, researched (Yigitcanlar et al., 2024).

Citizen perspectives play a central role in determining whether AI adoption in government is seen as legitimate and trustworthy. Schmager et al. (2024) found that citizens tend to support AI in public services when they trust the institutions implementing it, when there is a clear balance between individual and collective benefits, and when humans remain in control of key decisions. Transparency in data and model logic also strengthens acceptance.

Other studies have focused on recurring challenges faced by governments introducing AI, such as bias in algorithms, cybersecurity vulnerabilities, workforce adaptation, and bureaucratic resistance to change. Scholars like Malawani (2025) and Vatamanu and Tofan (2025) argue that addressing these issues requires governance systems that combine strong security and compliance structures with investment in human capacity, stakeholder participation, and clear lines of accountability.

At a more theoretical level, researchers such as Ghosh et al. (2025) emphasize the need for adaptive regulatory models that balance innovation with fairness, transparency, and economic sustainability. They identify weaknesses in current self, regulatory systems and propose design principles for building more trustworthy and responsive “AI states.”

Large, scale bibliometric studies provide a broader picture of how the field is evolving. Panda et al. (2025) show that research on AI in government has expanded rapidly since 2017, centering around themes such as ethics and policy challenges, governance and adoption, and the role of AI in transforming economies and public administration. These studies underline the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration, long, term evaluation, and institutional mechanisms that ensure AI aligns with public values.

This growing body of literature shows a clear shift: the discussion around AI in government has moved from promise to practice. We now understand that AI can enhance efficiency, transparency, and state capacity, but only if it is implemented responsibly. Legitimacy depends on setting clear socio-technical standards, maintaining human oversight, measuring outcomes beyond efficiency alone, and developing participatory governance that fosters both trust and innovation (Caiza et al., 2024; Straub et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2025; Zuiderwijk et al., 2021; van Noordt & Misuraca, 2022a).

Table 1 provides a comparative overview of the major review studies that have shaped the understanding of AI governance and adoption in public administration. These works collectively highlight the field’s conceptual richness but also expose methodological fragmentation. Batool et al. (2025) offered a valuable synthesis of governance frameworks across institutional levels, yet did not analyze how ideas cluster semantically across the field. Papagiannidis et al. (2025) expanded the discussion to responsible and ethical AI but focused broadly on cross-sectoral contexts rather than the specific dynamics of public administration. Babšek et al. (2025) overview of 2024 contributed extensive bibliometric evidence on adoption trends, though it lacked an interpretive framework connecting conceptual and empirical orientations. Finally, Laux et al. (2024) deepened the legal-regulatory perspective through the lens of the EU AI Act but remained confined to normative analysis without mapping interdisciplinary linkages. Together, these reviews reveal a gap that this study addresses by integrating semantic network and HOMALS analysis to uncover how technical, policy, empirical, and conceptual strands interact in the evolving AI-for-Government research landscape.

At the European level, these debates have been reframed by the EU Artificial Intelligence Act, which introduced a risk-based governance framework that mandates transparency, accountability, and human oversight for high-risk AI systems. The Act’s principles, trustworthy AI, human-centric design, and proportional regulation, mirror the theoretical foundations of algorithmic accountability and digital-era governance (Batool et al., 2025). This convergence between policy, theory, and empirical research illustrates how AI governance has become a mature interdisciplinary field spanning administrative science, data ethics, and law.

3. Methodology

To explore the evolving knowledge architecture of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in government and public administration, this study employed a hybrid analytical pipeline called the Semantic Community Method (SCM). The approach integrates natural language processing, network science, and multivariate statistics to identify conceptual patterns and thematic clusters in large text corpora. Unlike traditional bibliometric techniques that rely on citation co-occurrence or author networks, SCM maps semantic proximity between articles, revealing how ideas interrelate through shared meaning rather than citation frequency.

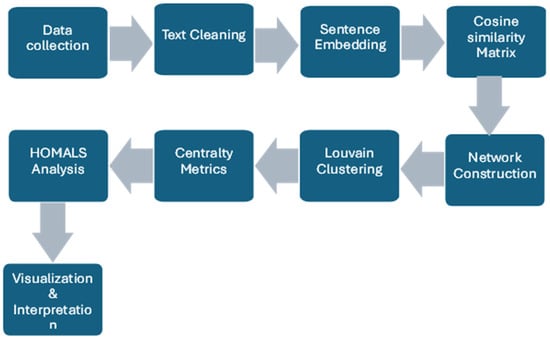

The analytical process used in this study follows a structured, multistage workflow that integrates text mining, semantic modeling, and network analysis to uncover the conceptual architecture of AI-for-Government research. As illustrated in Figure 1, the procedure begins with data collection and text cleaning, after which article abstracts are transformed into high-dimensional semantic vectors using sentence embedding models. Pairwise cosine similarity values are then calculated to construct a semantic network representing conceptual proximity among studies. The Louvain algorithm is applied to detect thematic communities, and centrality metrics identify the most influential or conceptually central papers within each cluster. Finally, HOMALS analysis classifies the corpus into conceptual orientations and visualizes their interrelations, providing a comprehensive view of the field’s underlying epistemic structure.

Figure 1.

Research workflow Semantic Community Method.

The initial dataset comprised 3957 records retrieved from the Web of Science using the query (“Artificial Intelligence” OR “AI”) AND (“government” OR “local administration” OR “regional administration”). After removing duplicates and incomplete records, a refined corpus of 3207 abstracts was obtained. Preprocessing was performed in Python (v3.11) using NLTK, spaCy, and pandas libraries. Text was converted to lowercase, punctuation and stop words were removed, and lemmatization was applied to standardize word forms.

Each cleaned abstract was encoded into a 384-dimensional semantic vector using the Sentence-BERT model all-MiniLM-L6-v2 from the sentence-transformers library. This model captures contextual meaning at the sentence level, enabling nuanced comparison of conceptually similar texts. Pairwise cosine similarity was then calculated between all article vectors, and only pairs with a similarity score of 0.85 or higher were retained to ensure meaningful conceptual overlap. We selected the cosine similarity threshold through a sensitivity check across 0.80–0.90. For each candidate value, we compared basic network properties (edge density, size of the largest connected component), the number and size distribution of detected communities, and modularity stability. A threshold of 0.85 offered the best balance between avoiding an overly dense graph at lower cutoffs and preventing excessive fragmentation at higher cutoffs, while maintaining stable modularity and community boundaries across the tested range. A threshold of 0.85 thus offered an optimal balance, resulting in a network with 1811 nodes (articles) and 14,805 edges representing significant semantic connections.

The Louvain community detection algorithm, implemented through the python-louvain package, was applied to this network to identify clusters of semantically related papers. The algorithm optimizes modularity by maximizing the density of links within communities compared to links between them. This method was chosen for its efficiency and reliability in large, sparse networks. For each detected community, degree centrality and PageRank centrality were calculated using the NetworkX library to identify conceptually influential papers that served as anchors for qualitative interpretation.

To further interpret the conceptual orientations of the field, the study used Homogeneity Analysis by Means of Alternating Least Squares (HOMALS) implemented via the prince Python package. The four prototypes (technical, policy, empirical, conceptual) were defined by selecting a small set of clearly representative abstracts for each orientation and computing an averaged embedding as the centroid reference for cosine comparison. To ensure face validity, we performed a manual check on a random sample of articles near the classification boundaries and confirmed that the assigned categories aligned with the substantive focus of the abstracts. Each article was categorized into one of four predefined conceptual types technical, policy, empirical, or conceptual based on semantic similarity to representative prototypes. This produced four hybrid categories: Policy/Conceptual, Policy/Empirical, Technical/Conceptual, and Technical/Empirical. HOMALS then projected these qualitative variables into a two-dimensional space, optimizing variance (inertia) to visualize how different orientations relate to one another across the research field.

Robustness checks confirmed the stability of results. Varying the similarity threshold between 0.80 and 0.90 produced consistent community structures with only minor boundary changes. Random subsampling and re-embedding maintained stable modularity values (Q ≈ 0.78 ± 0.02), and alternative embeddings using the BAAI/bge-small-en-v1.5 model yielded over 90% overlap in cluster membership, indicating methodological reliability.

Compared with traditional bibliometric techniques based on co-citation or keyword co-occurrence, the Semantic Community Method captures latent semantic relationships that transcend disciplinary boundaries. It is particularly effective in emerging research areas where citation networks are underdeveloped or fragmented. By detecting conceptual similarity rather than formal linkage, SCM uncovers how academic ideas converge and evolve across diverse domains. This methodological innovation complements conventional scientometric tools by offering a more direct and linguistically grounded approach to mapping interdisciplinary knowledge.

Overall, the Semantic Community Method integrates NLP-based embeddings, cosine similarity, Louvain community detection, and HOMALS analysis into a coherent and replicable framework for understanding the structure of scientific knowledge. Its application to the AI-for-Government corpus not only reveals how research themes and epistemic orientations technical, policy, empirical, and conceptual interact and evolve but also demonstrates a scalable model for analyzing other complex interdisciplinary domains.

All code and parameter settings used for preprocessing, embedding, thresholding, community detection, and HOMALS classification are available upon request

4. Results

Section 4 presents the semantic network structure and the nine major Louvain communities. We first summarize the overall network and cluster selection criteria, then provide a consolidated overview of the nine largest thematic communities (Table 2), followed by detailed cluster profiles. The section concludes with a HOMALS-based synthesis of the field’s conceptual orientations.

Table 2.

Overview of the nine largest Louvain communities detected in the semantic network.

Our analysis began with 3957 scientific articles retrieved from the Web of Science database using the query:

(“AI” OR “Artificial Intelligence”) AND (“government” OR “local administration” OR “regional administration”).

After removing duplicates and entries that contained only minimal bibliographic information (author names and titles), we obtained a clean dataset of 3207 articles. This ensured that only records with meaningful abstracts and metadata were included in the analysis.

To identify relationships among publications, we computed semantic similarity between article abstracts using sentence embeddings derived from the all-MiniLM-L6-v2 model. Articles with a cosine similarity greater than 0.85 were considered semantically connected, indicating substantial conceptual overlap. This filtering process produced a refined network of 1811 interconnected articles, meaning that each of these papers shared high semantic similarity with at least one other publication in the corpus.

The resulting network contained 1811 nodes (representing individual articles) and 14,805 edges (representing strong semantic connections). On average, each article was connected to 8.175 other articles, suggesting a moderately dense structure where ideas and research themes frequently intersect. This pattern reflects an emerging but cohesive scholarly landscape in the study of artificial intelligence in government and administration.

The Louvain community detection algorithm identified a total of 108 distinct thematic communities within the semantic network. These communities vary widely in size, from very small clusters containing only two or three articles, to large, well-developed thematic groups with over 300 interconnected publications.

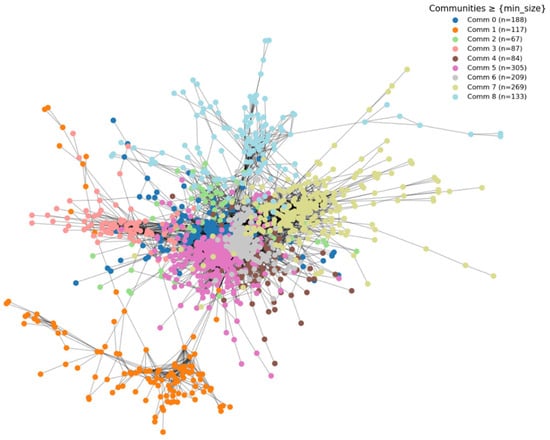

From these 108 detected communities, we focused our detailed analysis on the nine major groups, each containing more than 50 interconnected articles, presented in Figure 2. These larger clusters represent the core intellectual structure of the field. For clarity, we grouped them according to their conceptual focus:

Figure 2.

Network with Communities.

- AI and Public Administration Transformation: AI-Driven Administrative Transformation and Digital Governance and Public Sector Innovation both explore how AI reshapes public sector operations, decision-making, and service delivery, emphasizing efficiency, transparency, and institutional adaptation.

- AI and Societal Resilience: Artificial Intelligence and Digital Technologies in Pandemic Management and AI-Enabled Sustainability and Circular Economy highlight AI’s contribution to large-scale societal challenges, from crisis management to environmental and resource efficiency goals.

- AI, Citizens, and Ethical Governance: Citizen Trust and Acceptance of AI in Public Governance, AI-Driven Governance and Decision-Making, and AI Ethics and Governance Frameworks address the human and institutional dimensions of AI in government, focusing on trust, transparency, ethics, and the legitimacy of automated decision systems.

- AI in Domain-Specific Governance Contexts: AI Adoption, Ethics, and Trust in Healthcare and Artificial Intelligence in Education Policy and Practice explore how public sector AI adoption unfolds within key domains of social policy, shedding light on unique regulatory, ethical, and organizational challenges.

For each of these nine major communities, we conducted an in-depth content analysis of the ten most significant papers, as identified by their PageRank centrality within the semantic network. This approach ensured that the most influential and conceptually central publications, those most connected to others by thematic similarity, were systematically examined to capture the essence of each cluster.

Most of the smaller clusters reflect niche or highly specialized areas of research, often focusing on specific applications of AI within local or regional government contexts.

In contrast, the larger communities capture broader and more integrated topics, such as AI governance frameworks, citizen trust and ethics, data-driven decision-making, and the use of AI in public service delivery.

This size distribution illustrates the structure of the research landscape: a combination of many small, emerging topics and a few mature, interdisciplinary areas where academic attention is rapidly consolidating.

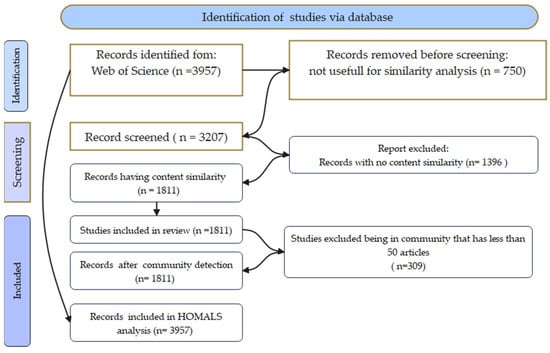

All stages of this process from initial data collection and cleaning, through semantic similarity mapping, to community detection are summarized in Figure 3: PRISMA Flowchart, which visually presents the step-by-step workflow and the number of records retained The Louvain community detection algorithm revealed 108 thematic communities within the semantic similarity network, capturing the diverse ways in which artificial intelligence (AI) intersects with governance, administration, and public value creation. These communities ranged in size from small, specialized clusters of two or three articles to large, interconnected thematic groups with more than 300 publications. This distribution reflects a research landscape characterized by many emerging niches alongside several mature, multidisciplinary domains where academic attention has begun to converge.

Figure 3.

PRISMA Flowchart.

The following parts present our analysis of these nine key communities and their most representative works.

4.1. AI-Driven Administrative Transformation

The “AI-Driven Administrative Transformation Cluster” thus captures how governments deploy AI to steer sustainable development, industrial decarbonization, and economic coordination. Comprising 298 articles, connected by 1477 edges, with an average degree of 4.96 and a radius of 6, this cluster represents a moderately dense and wide-reaching research community, suggesting a maturing but still evolving policy field in which administrative decision-making, innovation governance, and data-driven regulation intersect.

Across the ten representative studies, AI is consistently framed not only as a technological catalyst but as a governance instrument reshaping the logic of public administration and policy coordination. Al Mawla (2025) positions AI readiness as a determinant of macroeconomic performance and social inclusion, implying that administrative capacity and digital infrastructure are now central components of national competitiveness. Han et al. (2024) interpret AI governance through the lens of environmental policy, demonstrating that targeted government intervention amplifies AI’s capacity to reduce industrial carbon emissions, underscoring the policy-dependent nature of AI’s societal outcomes. Fu et al. (2024) analyze how state-owned enterprises respond to administrative incentives for green innovation, showing that AI’s regulatory embedding enhances the alignment of corporate behavior with national sustainability targets. Xu and Lin (2025) highlight the public governance dimension of intelligent transformation in the new energy sector, identifying how fiscal subsidies and administrative control quality modulate the innovation effects of AI. Fang and Yang (2025) provide empirical evidence that government marketization and incentive mechanisms channel AI toward improved energy efficiency, illustrating how administrative settings shape environmental performance. Xie and Wang (2024) extend this reasoning by uncovering the nonlinear governance dynamics of AI and carbon reduction, showing that administrative maturity, digital infrastructure, and human capital policies define the thresholds of AI’s effectiveness. Yang et al. (2025) interpret AI adoption within enterprises as a reflection of national governance quality and policy orientation, indicating that firms internalize state-led AI objectives through compliance and performance management systems. Yin et al. (2023) explore how government R&D support and market-based environmental instruments reinforce the positive administrative feedback loops between AI development and renewable energy transition. Georgescu et al. (2025) integrate AI governance with institutional stability and green finance, revealing how administrative quality and policy coherence advance Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These studies articulate a shared paradigm where AI becomes an administrative infrastructure for achieving adaptive, evidence-based, and sustainability-oriented governance linking state capacity, digital innovation, and ecological stewardship into one policy ecosystem.

4.2. Digital Governance and Public Sector Innovation

Within bibliometric and semantic network analysis, these cluster represents a coherent research community where nodes (articles) exhibit thematic proximity and shared intellectual roots, often through cross-citations and methodological alignment. Statistically, this cluster consists of 64 nodes connected by 98 edges, with an average degree of 1.53 and a radius of 6, indicating a more sparse and emerging research network, one that bridges diverse subfields of digital governance, public administration, and citizen-centered innovation. This body of literature conceptualizes “cluster” as a locus of cumulative learning and methodological convergence, reflecting the gradual institutionalization of digital transformation as a central paradigm in the study and practice of public administration.

Across the representative studies, digital transformation is interpreted as both a technological and administrative evolution, redefining how governments deliver services, engage citizens, and maintain accountability. Purnomo and Khabibi (2025) provide the cluster’s conceptual foundation through a systematic literature review outlining four subthemes, digital transformation, e-government, open collaboration, and innovation strategies, thereby mapping the epistemic terrain of digital innovation in public organizations. Bolívar et al. (2024) deepen this discourse by emphasizing the theoretical underpinnings of emerging technologies in civic participation, calling for stronger conceptual frameworks that balance technological potential with democratic legitimacy. Aristovnik et al. (2025) contribute empirical depth by identifying the determinants of disruptive technology capabilities in local governments, underlining the importance of proactive leadership, skill investment, and institutional readiness as administrative enablers of innovation. Valle-Cruz and Gil-Garcia (2022) adopt the PRISMA approach to systematically categorize emerging technologies, ranging from mobile platforms to AI and blockchain, highlighting both their transformative potential and ethical challenges, such as surveillance and loss of human oversight. Ranerup and Henriksen (2022) focus on the micro-governance implications of automation, analyzing “digital discretion” in Sweden’s social services and revealing how human and technological agency co-shape decision-making in welfare administration. Haraguchi et al. (2024) expand the cluster toward urban governance by assessing city digital twins through their CITYSTEPS Maturity Model, arguing that humancentric design, inclusivity, and transparent data governance are prerequisites for legitimate digital transformation. Karunaratne and Zitnik (2024) examine how disruptive technologies affect digital public service provision within EU cross-border initiatives, exposing gaps in administrative knowledge and interoperability under the Single Digital Gateway Regulation, thus linking local innovation to supranational governance. Sani and Jaafar (2025) employ bibliometric and content analyses to chart the evolution of IoT in the public sector, identifying its convergence with AI, blockchain, and smart city paradigms while warning of security and privacy vulnerabilities. Northcott (2025) investigates automation’s impact on street-level bureaucrats’ discretion, revealing that ICT standardization reshapes professional identity and hierarchical control, an insight critical to understanding the human dimension of digital government. Djatmiko et al. (2025) frame digital inclusion as a condition for sustainable governance, aligning e-government adoption with the UN Sustainable Development Goals and highlighting the need for participatory, equity-focused digital policy design. All these studies illustrate an emerging yet increasingly structured cluster of scholarship that conceptualizes digital transformation not as mere technological modernization but as a profound reconfiguration of governance capacity, institutional trust, and social equity in the public sector.

4.3. AI and Digital Technologies in Pandemic Management

The “AI and Digital Governance in Pandemic Management Cluster” comprises 117 nodes, 303 edges, an average degree of 2.59, and a radius of 7, characterizing it as a moderately connected but intellectually dynamic network linking public health, digital transformation, and policy innovation under conditions of global disruption. This cluster collectively interprets “cluster” not merely as a statistical structure but as an evolving body of knowledge, where the COVID-19 pandemic acted as an accelerant for AI’s application in governance, healthcare, education, and data-driven decision-making.

Across the ten representative papers, AI emerges as both a technological instrument and a governance paradigm enabling states and institutions to manage uncertainty and enhance administrative responsiveness. Chandra et al. (2022) initiate this discussion by mapping how digital technologies and Industry 4.0 tools, including AI, IoT, and cloud computing, helped governments and industries maintain operations and health services during COVID-19, thus situating AI at the intersection of policy, health, and industrial resilience. S. Khan et al. (2023) extend this perspective by proposing a taxonomy of intelligent technologies employed during the pandemic, highlighting AI’s coordination role among public agencies and underscoring open challenges in integrating cloud and high-performance computing for real-time public health management. M. Khan et al. (2021) consolidate this thread through a comprehensive review of AI applications ranging from diagnosis to epidemiological forecasting emphasizing their implications for decision-makers, healthcare institutions, and data governance policies. Pillai and Kumar (2021) deepen the governance aspect by focusing on AI’s role in the “public sphere,” illustrating how governments used data-driven systems to analyze infection trends and support evidence-based crisis policymaking. Al Mnhrawi and Alreshidi (2023) translate these insights into the education domain, analyzing how Saudi Arabia’s higher education institutions used AI tools to ensure learning continuity under national administrative mandates, while also noting the governance challenge of equitable access and digital literacy. Aisyah et al. (2023) offer a case of administrative digitalization in Indonesia, revealing how government-academia-private sector collaborations co-developed AI and big data tools for pandemic detection and response, symbolizing a new governance model for public health systems. Lanyi et al. (2022) demonstrate how governments leveraged AI-based natural language processing (NLP) to analyze public sentiment toward vaccination on Twitter, providing evidence of algorithmic tools as extensions of public communication and behavioral governance. Yu et al. (2021) present the COVID-19 Pandemic AI System (CPAIS), integrating Oxford and Johns Hopkins datasets to forecast infection dynamics through deep learning, thereby illustrating how AI can augment global policy coordination and monitoring infrastructures. Poongodi et al. (2021) further highlight AI’s role in anticipating and mitigating second-wave effects, positioning data analytics and machine learning as core to government readiness and post-pandemic resilience strategies. Hantrais et al. (2021) broaden the cluster’s scope by embedding AI and digitalization within the broader “digital revolution” framework, showing how pandemic governance triggered new ethical and legislative responses to algorithmic decision-making, data privacy, and digital inequality. Together, these studies delineate a coherent research frontier where AI and digital technologies are institutionalized as instruments of crisis governance, policy foresight, and societal adaptation transforming the pandemic from a biomedical challenge into a testbed for algorithmic public administration.

4.4. AI-Enabled Sustainability and Circular Economy

In bibliometric terms, this AI-Enabled Sustainability and Circular Economy Cluster comprises 130 nodes, 296 edges, an average degree of 2.28, and a radius of 6, indicating a moderately connected research ecosystem where cross-references between sustainability, industry transformation, and technological innovation form the core of intellectual exchange. As a group, these works conceptualize a cluster not as an isolated thematic category but as a dynamic constellation of interconnected inquiries, uniting industrial ecology, smart agriculture, digital transformation, and green innovation under the broader banner of the digital-sustainability transition. This cluster reflects an epistemic shift in contemporary sustainability studies: from descriptive analyses of environmental issues to systemic approaches where AI, IoT, and data-driven intelligence actively shape resource efficiency, policy coherence, and circular economy governance.

Within this cluster, several distinct yet interdependent strands emerge. Purushothaman et al. (2025) establish the conceptual foundations by systematically mapping the theories, techniques, and strategies linking circular economy principles with emerging digital technologies such as AI, blockchain, and IoT, emphasizing cross-sector collaboration among governments, industries, and academia. Okot and Pérez (2025) advance this dialog by empirically demonstrating AI’s transformative role in sustainable agriculture in Costa Rica through structural equation modeling and scenario analysis, while underlining digital inequality and the need for public-sector interventions. Sood et al. (2023) focus on behavioral and organizational enablers of AI adoption, identifying user expectations, technology compatibility, and engagement activities as decisive for digital transition in farming communities, a key node connecting technological and human dimensions of sustainability. Das et al. (2023) situate AI within the Agri 5.0 and circular economy paradigm, revealing through fuzzy DEMATEL modeling that legal frameworks and government regulation are critical enablers of AI’s integration into food grain supply chains. Díaz-Arancibia et al. (2024) expand the lens to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in developing countries, showing how sociocultural and policy factors influence digital transformation and advocating for context-sensitive technology adoption models. Rosário et al. (2025) approach the topic from a macro perspective, demonstrating through bibliometric synthesis that digital development acts as a lever for sustainability across sectors, provided it is governed by adaptive and interdisciplinary frameworks. Sharma and Gupta (2024) integrate the Industry 5.0 paradigm, using multi-criteria decision models to reveal how AI, IoT, blockchain, and digital twins collectively enable cleaner production and sustainable competitive advantage, bridging industrial efficiency with environmental responsibility. Putri et al. (2025) focus on green growth in SMEs, identifying circular economy models, green finance, and digitalization as emerging drivers while calling for cross-sector policy harmonization and resilience-based approaches in post-pandemic recovery. Hearn et al. (2023) address the human capital dimension by examining education and training ecosystems for Industry 4.0, underscoring that successful industrial sustainability transitions hinge on continuous learning, innovation culture, and alignment between government and educational institutions. Prusty et al. (2025) link agriculture, AI, and sustainability through a systematic review of agri-allied sectors, identifying AI-driven robotics, machine learning, and sensor networks as transformative forces for resource efficiency, productivity, and environmental stewardship.

These studies articulate a convergent research field where AI serves not merely as a technological enhancer but as a governance and systems innovation tool embedded within the global shift toward circularity and sustainability. The moderate density of the network suggests that this field is still coalescing but increasingly interdisciplinary, linking industrial engineering, environmental economics, agricultural science, and digital policy into a unified research frontier. This cluster thus represents a critical node in the broader map of sustainable transformation scholarship: an academic ecosystem devoted to understanding how algorithmic intelligence, digital connectivity, and socio-technical adaptation collectively drive the regenerative reorganization of economies, institutions, and societies.

4.5. Citizen Trust and Acceptance of AI in Public Governance

The empirical and conceptual studies converge on understanding citizens’ trust, attitudes, and behavioral intentions toward Artificial Intelligence (AI) in government and public service delivery. Within bibliometric and semantic network frameworks, a cluster represents a dense interconnection of studies sharing conceptual proximity, thematic coherence, and methodological parallels. The “Citizen Trust and Acceptance of AI in Public Governance Cluster” comprises 203 nodes, 1499 edges, an average degree of 7.38, and a radius of 5, indicating a highly connected and mature research field. This reflects an established body of literature in which public administration, behavioral science, and digital governance intersect to examine how trust, transparency, ethics, and human oversight shape the legitimacy and acceptance of AI in public institutions. These studies define a cluster not only as a statistical or networked entity but as a living corpus of shared inquiry into the social contract between governments, citizens, and intelligent technologies.

Across the literature that defines this community, the central theme is the reconfiguration of public trust and democratic legitimacy in the age of algorithmic governance. Schmager et al. (2024) lay the normative foundation by examining citizens’ stances on AI in Norwegian public welfare services through a social contract perspective, identifying macro-level trust in government, meso-level balancing of collective and individual values, and micro-level reassurance through transparency and human oversight as key determinants of citizen acceptance. Mohamad et al. (2022) consolidate these insights through a large-scale review of 78 studies, identifying benefits such as efficiency and personalization alongside persistent challenges, bias, opacity, and privacy concerns, thus providing an analytical framework for both institutional readiness and ethical design. Bullock et al. (2025) extend this to the regulatory domain, empirically demonstrating how perceived risk and institutional trust predict support for AI governance measures, offering an evidence base for the interplay between public opinion and AI regulation. Savveli et al. (2025) map citizen attitudes across 30 empirical studies and find that perceived usefulness, trust, and transparency drive acceptance, while privacy and usability concerns remain central barriers, highlighting the continuing gap between technological capability and social legitimacy. Y. F. Wang et al. (2025) use behavioral public administration theory to model citizens’ willingness to follow AI-based recommendations during crises, showing that algorithmic transparency and communication strategies can strengthen compliance by mediating trust.

At the same time, empirical evidence grounds these conceptual insights. Chen et al. (2024) analyze AI chatbot implementation in U.S. state governments, showing that such tools transform bureaucratic operations and public interaction dynamics by improving responsiveness and efficiency while reshaping administrative labor structures. Aoki (2020) provides early experimental evidence from Japan, showing that citizens’ initial trust in AI chatbots depends strongly on contextual framing and communicated governmental purposes, an insight foundational to subsequent studies of user acceptance. Kleizen et al. (2023) test the limits of ethical AI information, finding that short-term communication about compliance and fairness has minimal influence on citizen trust, indicating that structural trust-building requires deeper cultural and institutional engagement rather than surface-level messaging. Horvath et al. (2023) further unpack these dynamics via conjoint experiments on AI-based decision-making in public permits, revealing that human involvement, appeals systems, and transparency substantially enhance perceptions of fairness and acceptance, though excessive discretion can undermine efficiency. Alzebda and Matar (2025) explore the moderating role of government regulation on citizen intention to adopt AI in Palestine’s public communication sector, showing that regulatory clarity amplifies the positive effects of usefulness, ease of use, and social influence, offering a critical governance perspective applicable across contexts.

These studies illuminate a richly interconnected research field at the intersection of AI governance, public trust, and administrative legitimacy. The high connectivity and compact structure of this cluster indicate an established theoretical core, anchored in social contract theory, behavioral public administration, and digital ethics, around which diverse empirical applications are organized. Thematically, the cluster signifies a broader shift in digital-era governance: from efficiency-driven e-government models toward trust-centric AI governance, where institutional design, ethical communication, and citizen perceptions co-determine the societal acceptance of algorithmic systems in public life.

4.6. AI-Driven Governance and Decision-Making

Within this densely interconnected body of literature, the concept of a cluster represents an advanced epistemic formation of scholarly work converging on the study of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in public governance, decision-making, and administrative transformation. The “AI-Driven Governance and Decision-Making Cluster” consists of 307 nodes, 5096 edges, an average degree of 16.6, and a radius of 3, denoting a highly mature and cohesive network where theoretical, empirical, and policy-oriented studies interact intensively. As a group, this cluster portrays AI as a pivotal agent reshaping the epistemology and practice of government, transforming administrative rationality, enhancing transparency, and reconfiguring decision architectures, while simultaneously amplifying challenges related to ethics, accountability, and democratic legitimacy. In the literature, “cluster” thus transcends its technical meaning as a networked aggregation of co-occurring terms or citations; it denotes an intellectual ecosystem in which multidisciplinary dialogs between computer science, political theory, and public administration produce a shared conceptual grammar for understanding governance “of, with, and by” AI.

The thematic coherence of this cluster emerges from a decade of rapid evolution in AI-governance research. Early foundational works such as Valle-Cruz et al. (2019) and Reis et al. (2019) established the initial policy and methodological frameworks for understanding AI’s role in government services, identifying both the opportunities for efficiency and the normative uncertainties surrounding algorithmic decision-making. Zuiderwijk et al. (2021) systematically advanced this foundation by articulating a research agenda that calls for empirical, multidisciplinary, and public-sector-focused inquiries, urging the field to move from conceptual enthusiasm toward grounded theory and institutional practice. van Noordt and Misuraca (2022a, 2022b) operationalized this agenda through extensive mapping of AI adoption across the European Union, distinguishing governance functions supported by AI, such as policy design, internal management, and service delivery, and developing frameworks for understanding the enabling conditions of successful integration.

Complementing these macro-level analyses, Zhao et al. (2025) introduced empirical evidence from China demonstrating that AI enhances government transparency by optimizing efficiency, deepening open-data practices, and strengthening citizen trust, thus linking technological mechanisms to governance outcomes. Similarly, Caiza et al. (2024) synthesized 50 studies to reveal how AI redefines decision-making logics within public institutions, emphasizing both efficiency gains and the persistent need for ethical oversight and accountability structures. Straub et al. (2023) contributed a unifying theoretical framework, anchored in the dimensions of operational fitness, epistemic alignment, and normative divergence, that bridges the social-scientific and technical perspectives of AI in government, marking a significant conceptual consolidation within the field. Charles et al. (2022) further explored AI’s capacity for data-driven governance, highlighting tensions between evidence-based decision-making, privacy risks, and public value creation, and calling for longitudinal and cross-sectoral studies to trace the evolution of AI assimilation in government.

The most recent wave of research moves toward implementation analysis and governance design. Vatamanu and Tofan (2025) empirically quantify the relationship between AI integration, governance improvements, and economic performance using DESI indicators, proposing a governance model balancing innovation with cybersecurity and ethical safeguards. These studies reveal a field that is both theoretically dense and empirically expansive, linking administrative science, data policy, and digital ethics within a shared discourse of responsible AI governance. The high connectivity (average degree = 16.6) and small radius of this cluster underscore a centrally positioned, interdisciplinary nexus in which the AI-governance paradigm has become both a subject of analysis and a driver of administrative modernization across jurisdictions.

Jointly, this literature delineates a paradigmatic shift from traditional e-government toward “intelligent governance”, where algorithmic systems are embedded not merely as tools of automation but as actors within decision ecosystems requiring transparency, legitimacy, and public trust. The cluster thus represents the intellectual consolidation of an emerging field, AI-enabled governance studies, that integrates computational capacities with normative reasoning to redefine how public institutions think, decide, and act in the digital age.

4.7. AI Ethics and Governance Frameworks

Within this interconnected body of scholarship, the concept of a cluster encapsulates a coherent intellectual formation focused on AI ethics, governance, and regulatory frameworks in government systems, where interdisciplinary approaches converge around questions of accountability, legality, and sociotechnical design. The “AI Ethics and Governance Frameworks Cluster” comprises 225 nodes, 1383 edges, an average degree of 6.15, and a radius of 4, indicating a moderately dense but conceptually integrated research community that bridges computer science, public administration, political philosophy, and law. As a group, this cluster conceptualizes “cluster” not merely as a bibliometric grouping, but as an evolving epistemic ecosystem in which scholars co-produce frameworks, norms, and models to operationalize responsible AI in public institutions. The literature converges on the understanding that effective AI governance requires translating abstract ethical principles into enforceable, context-sensitive mechanisms, linking accountability and transparency to institutional design, regulatory innovation, and public trust.

Engstrom and Haim (2023) anchor this cluster by addressing the sociotechnical nature of AI regulation in government, emphasizing that accountability cannot rely solely on external legal controls but must be embedded within organizational behavior and design. Their work highlights the need for regulatory approaches that acknowledge AI’s infiltration into discretionary, policy-sensitive domains where traditional administrative law has limited reach. Saheb and Saheb (2023) extend this systemic inquiry through a cross-national topic modeling of national AI policies, revealing how most governments emphasize education, technology, and ethics but often marginalize algorithmic transparency and startup inclusion. de Almeida and dos Santos (2025) provide an empirical contribution by analyzing 28 public organizations worldwide, showing that AI governance maturity strongly correlates with ethical training and the institutionalization of ethical design practices, culminating in the proposal of the AIGov4Gov framework. Similarly, J. Wang et al. (2024) bridge theory and implementation through their Ethical Regulatory Framework for AI (ERF-AI), which integrates multidisciplinary theories from organizational management, behavioral psychology, and process control, translating them into practical mechanisms for ethical review and iterative system improvement.

Complementary perspectives are offered by Ghosh et al. (2025), who conceptualize AI governance as a balance between oversight and innovation, calling for adaptive regulation that recognizes bias, transparency, and fairness as interdependent variables within dynamic sociotechnical systems. Saheb (2024) further enriches the discussion by mapping ethical AI policies across 24 nations, identifying convergence around core themes principles, data protection, and monitoring while exposing epistemological gaps in governments’ understanding of AI ethics. The normative depth of this cluster is underscored by Domanski (2019) and Greiman (2020), who explore the ethical dilemmas and human rights implications of AI deployment, warning that governance must anticipate systemic risks to autonomy and justice. Karimov and Saarela (2025) introduce a cross-national perspective on AI literacy, arguing that ethical AI governance depends not only on legal frameworks but also on societal capacity to comprehend and critically engage with algorithmic decision systems. Finally, Biju and Gayathri (2025) offer a contextualized exploration of algorithmic accountability in India, showing how sociocultural complexity amplifies the moral and legal stakes of AI misjudgment and advocating for frameworks rooted in political philosophy to bridge normative theory and local realities.

The AI Ethics and Governance Frameworks Cluster embodies a maturing research frontier that moves from declarative ethics to institutionalized governance, reflecting a growing recognition that the legitimacy of AI in public administration depends on its alignment with democratic values, human rights, and public trust. The network’s structural parameters, a moderate degree of connectivity and a compact radius, indicate a tight but multidimensional research community in which ethics, policy, and technical design are mutually constitutive. This synthesis situates the cluster as a cornerstone of the broader AI-in-government discourse, providing the normative and operational scaffolding for the transition from experimental AI regulation to a globally harmonized architecture of responsible, lawful, and human-centered AI governance.

4.8. AI Adoption, Ethics, and Trust in Healthcare

This cluster represents a dense constellation of studies united by their shared exploration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in healthcare systems, focusing on perceptions, governance, ethics, and readiness across professional, institutional, and patient contexts. The “AI Adoption, Ethics, and Trust in Healthcare Cluster” comprises 92 nodes, 322 edges, an average degree of 3.5, and a radius of 5, reflecting a moderately connected but thematically cohesive domain that bridges medical innovation, digital ethics, and public trust. Mutually, the reviewed literature conceptualizes “cluster” not as a mere grouping of studies but as a dynamic epistemic community where interdisciplinary approaches, combining medicine, information systems, and policy analysis, intersect to interrogate how AI reshapes the moral, organizational, and regulatory architecture of healthcare delivery. This cluster’s shared foundation lies in understanding the human dimensions of technological transformation: acceptance, accountability, equity, and the ethical governance of machine intelligence in medical decision-making.

Across the cluster, authors converge on the view that AI’s transformative potential in healthcare is matched by profound ethical and governance challenges. Nitiema (2023) captures the ambivalence among health professionals, whose online discussions reveal both enthusiasm for AI’s diagnostic precision and anxiety about job displacement, data integrity, and algorithmic opacity, establishing the cluster’s sociotechnical grounding. B. J. Wang et al. (2025) complement this with patients’ perspectives, showing that individuals with chronic diseases call for balanced AI-human collaboration, shared accountability, and regulatory oversight to preserve trust and agency in clinical decision-making. Tezpal et al. (2024) focus on the readiness of Indian health professionals, finding that while awareness of AI’s benefits is widespread, a lack of formal training and persistent concerns about data privacy hinder adoption, a theme echoed across emerging economies. Carter et al. (2020) provide a normative anchor through their ethical and legal analysis of AI in breast cancer care, identifying the tension between rapid innovation and insufficient oversight, and urging proactive governance to ensure that algorithmic medicine aligns with patient values and justice. Kapoor et al. (2024) expand this discussion to India’s national context, portraying AI as both a vector for healthcare equity and a policy challenge requiring investment in education, ethics, and interoperability. Castonguay et al. (2024) examine AI maturity across OECD health systems, revealing divergent trajectories shaped by governance capacity and the principle of “equifinality,” where multiple policy pathways can achieve responsible AI adoption.

Meanwhile, Adigwe et al. (2024) offer empirical insights from Nigeria, showing that knowledge and positive perceptions among healthcare workers coexist with uncertainties about job impacts and data governance, thereby emphasizing the need for context-specific policy frameworks. Phang et al. (2025) turn to Malaysia, documenting how fragmented legislation and limited regulatory expertise impede responsible AI deployment despite growing research activity, and proposing alignment with international ethical standards. Weinert et al. (2022) highlight similar barriers in Germany, where hospital IT leaders identify resource shortages and legacy infrastructure as key inhibitors of AI adoption, demonstrating how governance and capacity shape technological uptake even in advanced systems. Wong et al. (2025) explore older adults’ acceptance of AI-driven health technologies, underscoring the irreplaceable value of human care, the centrality of usability, and the necessity of government-backed ethical frameworks to ensure equitable access and trust.

These works delineate a global narrative in which AI’s medical promise is inseparable from its ethical, institutional, and societal contexts. The cluster’s interconnectedness reflects a maturing research frontier where adoption and governance co-evolve, and where responsible innovation demands integrating patient-centered design, clinician training, and multi-level regulatory coordination. As such, this cluster represents not only academic synthesis but also a conceptual blueprint for the future of trustworthy, human-centered AI in healthcare governance.

4.9. Artificial Intelligence in Education Policy and Practice

Within this focused subset of literature, the notion of a cluster denotes a coherent yet moderately diffuse body of research concerned with Artificial Intelligence in Education Policy and Practice (AI-EduPolicy Cluster), comprising 66 nodes, 151 edges, an average degree of 2.29, and a radius of 5, reflecting a network of distinct but mutually aware studies. Collectively, these works conceptualize “cluster” as an emergent intellectual domain linking pedagogy, policy, and technology governance through shared concern for responsible, explainable, and equitable AI adoption in educational ecosystems. Across this community, “cluster” functions not only as a bibliometric construct but as an epistemic space in which researchers, educators, and policymakers co-construct frameworks for integrating AI technologies, particularly generative and explainable AI, into national and institutional education systems. The literature converges on the understanding that AI’s educational transformation is contingent upon transparent policy design, stakeholder participation, ethical safeguards, and a balance between automation and human agency.

Knight et al. (2023) ground the discussion in policy discourse, presenting open-data evidence from Australia’s federal inquiry into generative AI in education, which captures the pluralistic and contested stakeholder positions shaping national strategy. Isotani et al. (2023) extend this dialogic approach by linking AI research and education policy, proposing action plans to bridge research practice and governmental decision-making through learning-science-based policy design. Kazimova et al. (2025) systematize the technological dimension via a PRISMA-based review of AI applications in higher education, demonstrating that adaptive and intelligent tutoring systems improve personalization and administrative efficiency, yet raise enduring issues of data governance and bias. Stracke et al. (2025) complement this with an inter-European comparative study, analyzing 15 higher-education AI policies and underscoring the dual imperative of teaching about AI and through AI, thereby institutionalizing AI literacy as a cornerstone of educational modernization. Chaushi et al. (2023) deepen the ethical and epistemic scope by focusing on Explainable AI (XAI) in education, emphasizing transparency, interpretability, and human-AI collaboration as prerequisites for trust and accountability in algorithmic learning environments.

At the national level, Lukina et al. (2025) explore Russia’s AI-enabled school transformation, revealing regional disparities in digital infrastructure and proposing cohesive policy measures for equitable AI integration. Sandu et al. (2024) bring an applied perspective through an Australian case study that formulates a GenAI-empowered curriculum framework, situating generative models as tools for personalized and ethical learning design. Luan et al. (2020) offer a foundational perspective by linking big data analytics and AI policy, arguing that sustainable educational innovation requires reciprocal academia-industry collaboration and lifelong teacher training underpinned by robust data protection regimes. Egara and Mosimege (2024) provide empirical insights from Nigerian mathematics education, documenting educators’ limited awareness yet cautious optimism toward ChatGPT integration and calling for professional development to bridge technological and pedagogical divides. Zhang et al. (2025), while operating in the adjacent domain of tourism, broaden the policy lens by introducing the TECH-Trust Model, which conceptually parallels AI-in-education governance through its integration of technological affordances, cultural adaptation, and regulatory trust architectures.

Mutually, these studies articulate a multi-scalar vision of AI’s role in educational ecosystems, where policy coherence, ethical literacy, and pedagogical alignment are the principal vectors of innovation. The relatively low average degree and moderate radius indicate a diverse but thematically consistent research community, where knowledge exchange occurs through shared frameworks rather than direct co-citation density. The AI-EduPolicy Cluster thus represents a dynamic frontier within the broader AI-in-governance landscape, one where education serves simultaneously as a testbed and a moral compass for shaping equitable, transparent, and human-centered AI futures.

4.10. HOMALS Analysis

To better understand how different kinds of research contribute to the field of AI in government, we applied Homogeneity Analysis by Means of Alternating Least Squares (HOMALS) to the full set of article abstracts. HOMALS is a statistical technique similar to principal component analysis, but it works with qualitative or categorical data instead of purely numerical values. In simple terms, it helps us find hidden dimensions or patterns that organize how ideas and topics appear together across studies. We started by representing each abstract as a set of categorical indicators such as whether the article focused on technical, policy, empirical, or conceptual aspects. The HOMALS algorithm then transformed these qualitative categories into coordinates in a low-dimensional space, allowing us to visualize how studies cluster together based on their conceptual orientation.

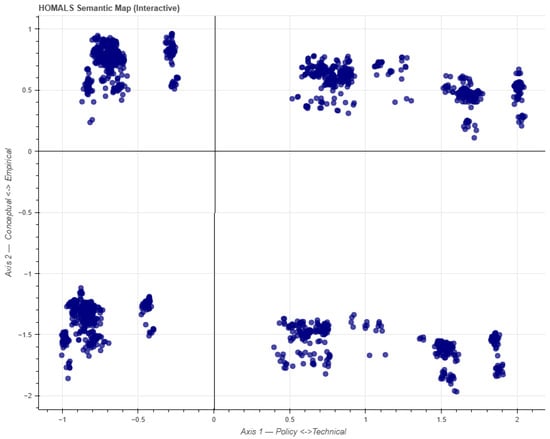

To define these orientations more precisely, we used semantic similarity analysis with predefined concept prototypes: technical, policy, empirical, and conceptual, as seen in Figure 4. Each article was compared to these prototypes using cosine similarity, which measures how closely the meanings of words align. This allowed us to assign every article to one of four main conceptual groups. The results reveal a rich diversity of approaches: Policy/Conceptual studies dominate the field with 1666 articles, followed by Policy/Empirical (871), Technical/Conceptual (989), and Technical/Empirical (431).

Figure 4.

Homals semantic map.

These findings, illustrated in Figure 2, show that most AI-for-government research still focuses on theoretical or governance-related questions, while a smaller but growing share explores empirical and technical dimensions. This balance reflects the evolving maturity of the field from conceptual discussions of ethics and governance toward more data-driven, applied, and interdisciplinary research.

Inspection of the HOMALS map suggests that Dimension 1 primarily separates policy-oriented work from technically oriented research, reflecting differences between governance frameworks and implementation-focused studies. Dimension 2 appears to differentiate conceptual/normative contributions from empirical/measurement-driven work, indicating the field’s balance between theorizing AI’s institutional role and testing it in practice. The predominance of Policy/Conceptual studies (n = 1666) confirms that AI-for-government remains anchored in questions of legitimacy, ethics, and institutional design, while the substantial presence of Policy/Empirical and Technical/Conceptual work signals a widening methodological and interdisciplinary base. The relatively smaller Technical/Empirical segment indicates that large-scale, applied evaluations of AI tools in administrative settings remain an emerging frontier.

Taken together, these clusters form a cohesive but multidimensional research landscape. The policy-oriented communities (Clusters 1, 2, 3 and 6) dominate in size and citation influence, reflecting that AI in government remains primarily a governance rather than a technical field. Yet the increasing density of edges between policy and technical nodes suggests growing interdisciplinarity. Technical clusters (4, 5, 8 and 9) provide the methodological backbone, developing data architectures and analytical tools, while empirical clusters (1, 5 and 7) anchor these innovations in real-world practice. This balance indicates a maturing ecosystem where conceptual and empirical approaches are converging to inform evidence-based governance models.

5. Discussion

The results of this study confirm the central hypotheses proposed in the research questions (RQ1–RQ3) and highlight the structural and epistemic dynamics shaping the academic field of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in public administration.

RQ1 examined the dominant conceptual and empirical orientations of AI-for-Government research. The HOMALS analysis confirmed a clear predominance of Policy/Conceptual studies (1666 articles), which underscores that AI in governance is still primarily understood through frameworks of legitimacy, ethics, and institutional adaptation. However, the presence of nearly 1400 articles across Policy/Empirical and Technical/Conceptual orientations signals a gradual but steady convergence toward more evidence-based and interdisciplinary approaches. This shift validates the hypothesis that the field is evolving from theoretical reflection toward applied governance models, integrating technical depth with normative accountability.

RQ2 explored how these orientations cluster into thematic communities and what this reveals about the evolution of the field. The Louvain community detection identified nine major clusters that articulate the multidimensional nature of AI in public governance ranging from administrative transformation and digital innovation to ethics, trust, sustainability, healthcare, and education. The coexistence of mature, policy-driven clusters (e.g., AI-Driven Governance and Decision-Making, AI Ethics and Governance Frameworks) alongside technically anchored and sectoral ones (e.g., AI-Enabled Sustainability and Circular Economy, AI in Education Policy and Practice) demonstrates that AI governance has moved beyond disciplinary silos into a hybrid ecosystem of conceptual reflection and practical implementation. This confirms our second hypothesis that the field’s internal structure is increasingly interconnected, with policy and technical discourses co-evolving rather than existing in parallel.

RQ3 investigated how semantic and network-based methods enhance understanding of interdisciplinary knowledge architectures. The integration of semantic similarity mapping, Louvain clustering, and HOMALS dimensional reduction validated the methodological hypothesis that AI governance research can be meaningfully visualized as a semantic knowledge system rather than a fragmented citation network. The Semantic Community Method captured latent conceptual proximity between studies that would otherwise remain hidden in traditional bibliometric analyses. This methodological contribution provides a replicable model for future research in other emerging interdisciplinary fields, such as digital ethics, smart cities, and sustainability governance.

The results of our bibliographic and semantic analysis reveal a field that is both intellectually rich and methodologically diverse, reflecting the rapid evolution of artificial intelligence (AI) in government and administration from a peripheral innovation to a core governance concern. The nine major clusters identified through our Louvain community analysis demonstrate that AI’s role in the public sector is multifaceted simultaneously technical, ethical, institutional, and social. The dominance of the Policy/Conceptual orientation identified through the HOMALS analysis suggests that much of the scholarship continues to explore how AI aligns with governance values, regulatory structures, and democratic legitimacy. Yet, the steady growth of Empirical and Technical studies indicates a progressive shift toward application-based and evidence-driven approaches. Together, these trends highlight the ongoing integration of AI into real-world administrative systems, where conceptual frameworks are increasingly being tested and refined through practice.

The communities themselves reveal distinct but complementary perspectives. Clusters such as AI-Driven Governance and Decision-Making and AI Ethics and Governance Frameworks show that scholars are actively building normative and operational models for responsible AI adoption. In contrast, clusters like Digital Governance and Public Sector Innovation and AI-Driven Administrative Transformation focus more on implementation mapping how AI technologies are being embedded into bureaucratic and service-delivery processes. The clusters related to Citizen Trust and Acceptance, Healthcare, and Education highlight the social and ethical dimensions of AI deployment, emphasizing that successful adoption depends on legitimacy, transparency, and inclusion. Meanwhile, the clusters addressing Sustainability and Pandemic Management demonstrate AI’s potential to contribute to resilience and policy adaptation in times of systemic disruption.

Future research on Artificial Intelligence (AI) in public administration must move beyond viewing algorithms as tools of automation and examine how they transform the reasoning, legitimacy, and accountability of governance itself. The findings of this study show that AI is becoming embedded in administrative cognition, influencing how governments define problems and make decisions. Future scholarship should therefore explore this shift toward cognitive governance, investigating how human and machine intelligence interact within bureaucratic processes, how discretion is redistributed, and how accountability can be maintained in hybrid decision systems.

Another crucial direction lies in closing the implementation gap between ethical principles and administrative practice. While frameworks for trustworthy and human-centric AI are well established, empirical studies should examine how they are institutionalized in government workflows. Comparative research across EU member states could assess how agencies interpret and operationalize the AI Act’s provisions on risk management, transparency, and oversight. Measuring how citizen trust evolves after AI adoption in public services would also clarify whether ethical safeguards achieve their intended effects or require redesign.

Research on AI for sustainability and the circular economy should advance toward integrated models of regenerative governance, aligning algorithmic innovation with ecological responsibility. AI’s efficiency gains must be tested against environmental and social trade-offs, leading to the development of “green algorithm audits” that extend the AI Act’s conformity assessments to environmental impact metrics.

At the European level, more attention should be given to cross-border interoperability. The EU’s data space initiatives demand analytical frameworks that treat interoperability not only as a technical standard but as a new mode of governance coordination. Comparative and network-based studies could map how regulatory approaches and institutional models circulate across jurisdictions, informing the creation of a European AI governance graph.

A further frontier involves human capacity and algorithmic literacy. AI adoption in government depends as much on organizational culture as on technology. Future studies should assess how civil servants’ digital competencies, ethical reasoning, and interpretive skills shape implementation outcomes. Education-oriented research can evaluate whether programs such as AI4Gov-X or the Digital Europe Skills Agenda enhance the ability of officials to design, audit, and communicate about AI systems.

Building on the Semantic Community Method, future work should extend this mapping longitudinally to trace how AI-for-Government themes and orientations evolve over time and to identify inflection points driven by technological breakthroughs and regulatory shifts. A second priority is to link semantic communities to measurable implementation outcomes—such as service performance, cost-efficiency, fairness indicators, or accountability mechanisms—to move from knowledge architecture to evidence of public value. Comparative cross-national analyses would also help clarify how different administrative traditions and regulatory regimes shape the configuration of AI research and policy narratives. Finally, the relatively smaller Technical/Empirical segment suggests the need for more rigorous evaluations of real-world public-sector AI systems, including procurement, human-in-the-loop design, explainability practices, and citizen-facing transparency tools.

From a methodological perspective, the use of the Semantic Community Method and HOMALS analysis has proven particularly effective in capturing the structure of this interdisciplinary field. By combining machine learning embeddings with social network and multivariate analyses, we were able to map how ideas and discourses are interconnected beyond disciplinary or citation boundaries. The average degree and network radius values across clusters show a mix of mature and cohesive communities alongside more exploratory or emerging topics. This balance suggests a healthy and dynamic research ecosystem, one where conceptual debate coexists with practical experimentation.