Abstract

Orange processing generates large amounts of waste orange peels (WOPs), which are a valuable source of bioactive polyphenols. This study investigated the use of mild (urea) and strong (sodium hydroxide) alkaline catalysts to enhance polyphenol extraction via an ethanol-based organosolv process. First, the two catalysts were evaluated in terms of process performance, extraction kinetics, and treatment severity. Subsequently, response surface methodology was applied to optimize the conditions, and the obtained extracts were characterized for their polyphenolic profile and antioxidant activity. The sodium hydroxide (SoHy)-catalyzed treatment, using 70% ethanol as solvent, was the most effective, yielding 33.4 ± 1.7 mg of total polyphenols (as gallic acid equivalents) per gram of dry mass. For both catalysts tested, the yield followed a severity-dependent linear model. Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry of extracts produced under optimized conditions showed that hesperidin was the predominant polyphenolic constituent, but the SoHy-catalyzed treatment resulted in the generation of three novel compounds, tentatively identified as ethyl esters of p-coumaric, ferulic and sinapic acids. Such an effect was not observed in the extracts produced with the urea (Ur)-catalyzed treatment. This compositional modification was reflected on both the antiradical activity and ferric-reducing power, which were found to be significantly enhanced in the extracts produced via the SoHy-catalyzed treatment. These findings highlight how treatment conditions can be tuned to modify the polyphenolic composition of WOP extracts and reinforce antioxidant activity. Such insights could support the development of WOP valorization strategies within integrated biorefineries.

1. Introduction

With the rapid growth of the global population, the need for increased food production has risen significantly. However, this expansion is frequently associated with the overuse of natural resources, the accumulation of by-products and waste, and considerable environmental damage. The agricultural and food sectors generate substantial quantities of residual biomass, much of which is disposed of in landfills, thereby intensifying environmental challenges and creating potential health hazards. At the same time, it is increasingly acknowledged that by-products from agricultural and food processing activities—such as pruning residues, post-harvest materials, and waste from food production and consumption—are rich in valuable bioactive compounds. Consequently, circular economy strategies based on advanced biorefinery technologies have been developed to convert these side streams into high-value products for applications in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries [1,2].

Food processing by-products can be viewed as valuable resources, as they are rich in a wide array of bioactive phytochemicals such as polysaccharides, essential oils, pigments, and antioxidants. Among these compounds, polyphenols—secondary metabolites produced by plants—are particularly noteworthy due to their broad spectrum of biological activities and are regarded as some of the most valuable constituents recoverable from industrial food processing residues [3]. Polyphenols display considerable structural diversity and exhibit multiple biological effects, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, cardioprotective, and chemoprotective properties [4]. As a result, biomass abundant in polyphenols has attracted significant interest across various industrial sectors.

Citruses represent the largest fruit crop globally, with oranges making up around 60% of total citrus production. Most oranges are processed into juice, yielding roughly 50% juice by fresh fruit weight. The remaining half consists of by-products such as peels, seeds, pulp, and rejected fruits [5]. In 2019, global orange production reached 46 million metric tons, with about 37% being processed into various products. These figures clearly highlight orange processing by-products as a significant source of food industry waste. Therefore, developing strategies for the reuse and valorization of orange processing residues—particularly for the efficient recovery of polyphenols—is essential. This is especially relevant given the extensive research demonstrating the beneficial bioactivities of citrus flavonoids, which are widely utilized in nutraceutical and health supplement formulations.

In solid–liquid extraction techniques, a key goal is to disrupt the plant cell wall matrix to enable the release of intracellular compounds—especially bound polyphenols—and promote their diffusion into the solvent phase [6,7]. This structural breakdown enhances mass transfer, thereby increasing extraction efficiency. The decomposition or partial depolymerization of cell wall components such as hemicellulose and lignin can be effectively induced through high-temperature thermal treatments [8]. When these processes are carried out using water or aqueous solvents, they are termed hydrothermal treatments; in contrast, the use of organic solvents under elevated temperature and pressure conditions is known as organosolv treatment [9,10]. The fundamental aim of these pretreatment technologies is to dismantle the cellulose–hemicellulose–lignin matrix, thereby facilitating subsequent saccharification and fermentation processes. Moreover, the partial degradation of polysaccharides also contributes to the liberation of polyphenols from complex plant matrices, ultimately enhancing polyphenol extraction efficiency.

These processes typically involve the treatment of lignocellulosic biomass with organic solvent–water mixtures under elevated temperatures for a defined residence time, with both parameters exhibiting a mutual dependency [11,12]. The incorporation of catalysts, such as sodium hydroxide, can further enhance treatment efficiency by accelerating the cleavage of ether and ester linkages. These linkages are also responsible for the esterification of hydroxycinnamates (e.g., ferulic acid) to polysaccharides within cell walls [13]. Consequently, the bound polyphenolic compounds are not readily extractable using conventional solvent extraction techniques; however, their liberation can be achieved through hydrolytic processes employing alkaline catalysis [14,15].

Recent investigations into the ethanol-based organosolv treatment of wheat bran have demonstrated that sodium hydroxide functions as an effective catalyst in liberating ferulic acid from wheat bran [16]. However, although WOP is a lignocellulosic material, such investigations have never been performed to examine the manifestation of similar phenomena. Building upon these findings, the development of an organosolv treatment for the recovery of polyphenols from WOP employing alkaline catalysis represents a promising yet technically demanding endeavor. Having this as the scope, an organosolv process was developed with the aim of maximizing polyphenol release and recovery from WOP, using ethanol as an environmentally friendly, non-toxic and readily available solvent [17], and both Ur and SoHy as alkali catalysts. The treatment’s performance was evaluated in terms of both efficiency and intensity by calculating combined severity factors and employing response surface optimization. The resulting extracts were analyzed through the tentative identification and quantification of major polyphenolic compounds. Antioxidant activity was further assessed as a supplementary indicator of treatment efficacy. To the authors’ knowledge, this study represents the first report on an alkali-catalyzed organosolv process applied to WOP for the recovery of antioxidant polyphenols.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals—Reagents

Sodium carbonate (>99.8%), iron(III) chloride hexahydrate, urea (99%), and 2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine (TPTZ) were purchased from Honeywell/Fluka (Steinheim, Germany). Hesperidin (hesperetin 7-O-rutinoside, ≥80%), ascorbic acid, narirutin (naringenin 7-O-rutinoside, ≥98%), 2,2-diphenylpicrylhydrazyl (DPPH), sinapic acid, ferulic acid, p-coumaric acid, and gallic acid were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). The Folin–Ciocalteu reagent was supplied by Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). All solvents used for chromatographic analyses were of HPLC grade.

2.2. Waste Orange Peel Procurement and Handling

Around 2 kg of discarded orange peels were obtained from a catering facility in Chania (South Greece), within 2 h of their disposal, and promptly transported to the laboratory. The peels were carefully inspected to remove residual pulp and other impurities, then rinsed with cold tap water. After washing, they were manually cut into pieces of roughly 2 × 2 cm, arranged on trays, and dried in a laboratory oven (Binder BD56, Bohemia, NY, USA), at 70 °C for 24 h. The dried material was then ground using a laboratory mill (Tristar, Tilburg, The Netherlands) and sieved to obtain a powder with an average particle size below 300 μm. This powder served as the raw material for all subsequent experiments.

2.3. Alkali-Catalyzed Ethanol Organosolv Treatment

Solutions of 70% ethanol containing either SoHy (0.5, 1, 1.5 and 2%) or Ur (2.5, 5, 7.5 and 10%) were used to carry out the organosolv treatments. A volume of 20 mL of each solvent was combined with 1 g of dried and pulverized WOP, and treatment was accomplished at 80 °C, for 240 min, under continuous agitation at 400 rpm. Both stirring and heating were provided by a hotplate (AREC.X, Velp Scientifica, Usmate, Italy). After the completion of the treatment, cell debris was separated from the extract with centrifugation at 10,000× g, in a REMI NEYA 16R centrifuge (Remi Elektrotechnik Ltd., Palghar, India). The clear extract obtained was used for further examination.

2.4. Treatment Severity Determination

Severity was determined for various combinations of treatment temperature and residence time, as shown below [18]:

The severity factor (SF) was determined as follows:

SF = logRo

Ro is severity, t is the residence time, T is the treatment temperature, the value 100 °C is the reference temperature, and 14.75 an empirical factor related to the temperature of the treatment and activation energy. Based on SF, the combined severity factor (CSF) and the alternative combined severity factor (CSF’) were computed as follows [19]:

CSF = logRo’ − pH

CSF’ = logRo + |pH − 7|

2.5. Kinetic Assay

The model deployed was first-order kinetics, as described elsewhere [20]:

where YTP(t) corresponds to the total polyphenol yield at any time t, YTP(s) to the total polyphenol yield at saturation (equilibrium), and k is first-order extraction rate constant (min−1).

YTP(t) = YTP(s)(1 – e−kt)

2.6. Response Surface Optimization of Treatments

The optimization procedure was designed to identify the optimal combination of two critical parameters—residence time (t) and temperature (T)—to enhance treatment performance, evaluated in terms of total polyphenol yield (YTP). Accordingly, these two independent variables (t and T) were selected to develop the experimental framework using response surface methodology (RSM). A central composite design consisting of 11 experimental runs, including 3 center points, was employed. The variables were coded at three levels (−1, 0, and 1), following a previously reported approach [21]. The coded and corresponding actual values of the variables are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Treatment variables used to construct the experimental design and their corresponding actual and coded values.

The selected ranges for both variables were determined from the kinetic assay while also taking into account prior findings [22]. The statistical evaluation involved assessing the significance of the mathematical model (R2, p-values) as well as each model coefficient, using lack-of-fit and ANOVA tests, with a 95% confidence level as the threshold for significance.

2.7. Determination of Yield in Total Polyphenols (YTP) and Antioxidant Activity

The concentration of total polyphenols in the extracts generated was measured using the Folin–Ciocalteu method [23]. Gallic acid served as the calibration standard (R2 = 0.9991), and the results were expressed as gallic acid equivalents (GAEs). The yield in total polyphenols (YTP) was reported in mg GAE per gram of dried WOP. Additionally, the antiradical activity (AAR) and ferric-reducing power (PR) of the extracts were evaluated following established protocols [24]. AAR results were expressed as μmol DPPH per gram of dried WOP, while PR results were expressed as μmol ascorbic acid equivalents (AAEs) per gram of dried WOP (R2 = 0.9989).

2.8. Liquid Chromatography—Diode Array—Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-DAD-MS/MS)

Prior to analysis, samples were diluted with HPLC-grade methanol. Analyses were carried out using a TSQ Quantum Access LC–MS/MS system equipped with a Surveyor pump (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and an Acquity PDA detector (Waters, Milford, MA, USA), operated through XCalibur 2.1 and TSQ 2.1 software. Chromatographic separation was performed on a Fortis RP-18 column (150 × 2.1 mm, 3 μm) maintained at 40 °C, with an injection volume of 10 μL and a flow rate of 0.3 mL min−1. The mobile phase consisted of eluent A (1% acetic acid in water) and eluent B (99% acetonitrile with 1% acetic acid). The gradient program was set as follows: 5% B from 0 to 2 min, increased to 50% B from 2 to 27 min, and raised to 100% B from 27 to 29 min. Mass spectra were acquired in negative ionization mode using a spray voltage of 3000 V, sheath gas pressure of 30 (arbitrary units), auxiliary gas pressure of 10 (arbitrary units), and a capillary temperature of 350 °C. All flavones were tentatively identified by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry in positive ionization mode, applying the chromatographic and mass spectral conditions described earlier [25]. Dereplication of mass spectra and UV–visible data was performed according to an earlier methodology [26]. The chromatographic system and analytical procedures were implemented as given in a previously published study [27]. In short, Flavone quantification was achieved using luteolin 7-O-glucoside as an external standard for calibration. In addition, the tentatively identified ethyl p-coumarate, ethyl ferulate and ethyl sinapate, were quantified with p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid and sinapic acid as the corresponding external standards. Likewise, narirutin and hesperidin were tentative identified using negative ionization mode and quantified with commercially available standards. All standard solutions were prepared in HPLC-grade methanol immediately before use, within a concentration range of 0–50 μg mL−1.

2.9. Data Processing—Statistics

The experimental design, response surface methodology (RSM), and statistical evaluations—including ANOVA and lack-of-fit tests—were performed using JMP™ Pro 16 software (SAS, Cary, NC, USA). Linear and non-linear regression analyses were conducted with SigmaPlot™ 15.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA), adopting a minimum significance threshold of 95%. Since the Shapiro–Wilk test revealed that the data did not follow a normal distribution, group comparisons were carried out using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test in IBM SPSS Statistics™ 29 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All treatments were performed at least in duplicate, whereas chemical analyses (chromatographic and spectrophotometric) were conducted in triplicate. Results are expressed as mean values ± standard deviation (SD).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Effect of Alkali Catalyst Type and Concentration

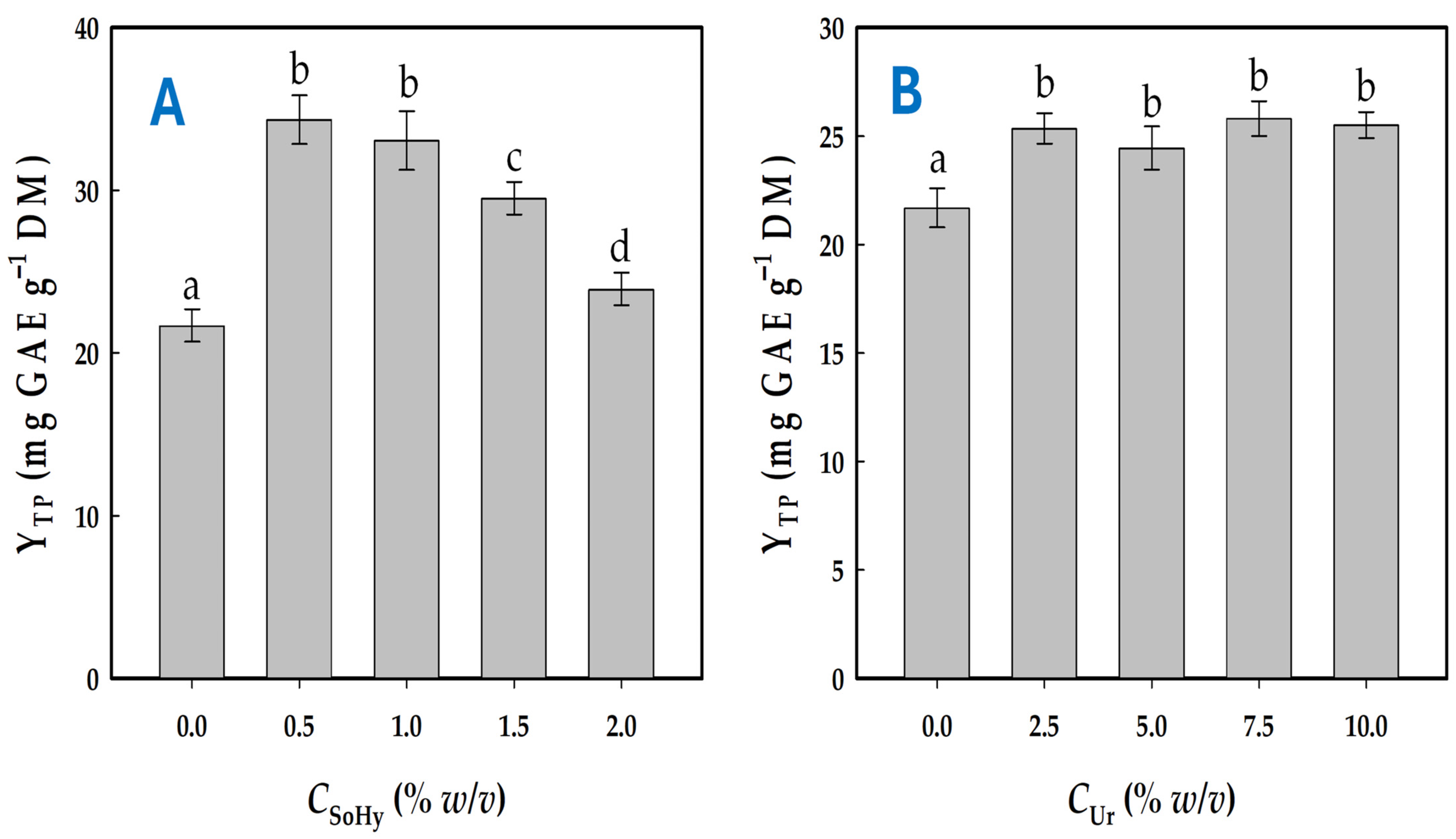

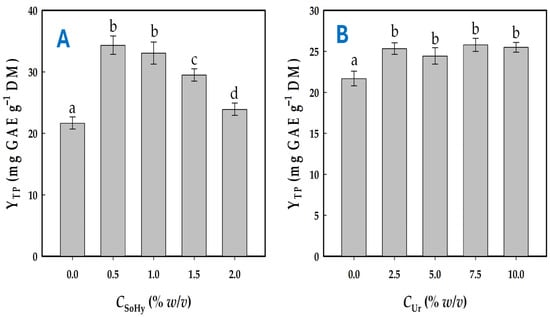

For all treatments, a 70% ethanolic solution was used containing variable concentrations of either SoHy (a strong alkali catalyst) or Ur (a mild alkali catalyst). In the first case, the pH of the solvents employed varied from 6.20 (neat 70% ethanol) to 12.70 (70% ethanol containing 2% SoHy), whereas in the latter case the range was from 6.20 to 8.05 (70% ethanol containing 10% w/v Ur). The screening of SoHy concentration showed that solutions of 0.5 and 1% promoted significantly higher polyphenol recovery compared to 70% ethanol (p < 0.05), but concentrations higher than 1% were not favorable in this regard (Figure 1A). Furthermore, it was noted that no statistically significant difference existed between 0.5 and 1% SoHy.

Figure 1.

Diagram showcasing the effect of SoHy (A) and Ur (B) concentration on the total polyphenol yield. All treatment of waste orange peels (WOPs) were performed with 70% ethanol as solvent. Bars designated with different small letters (a–d) are values with statistically significant difference (p < 0.05).

The behavior of Ur-containing solutions was very different, and while 70% ethanol incorporating 2.5% Ur was significantly more effective in polyphenol recovery than neat 70% ethanol (p < 0.05), any further increase in Ur concentration up to 10% did not produce a stronger effect (Figure 1B). On the basis of these findings, 70% ethanol containing either 0.5% SoHy or 2.5% Ur was chosen for further investigation.

3.2. Effect of Treatment Severity on Total Polyphenol Yield

To test the influence that severity could exert on treatment performance, several pairs of residence time and temperature were tested, as presented in Table 2. In all cases investigated, the Ur-catalyzed treatments were of relatively low CSF’, which varied from 0.09 to 2.50. On the other hand, the SoHy-catalyzed treatments were characterized by significantly higher CSF’, ranging from 5.38 to 7.79. Based on the trials carried out, it was seen that maximum YTP with the Ur-catalyzed treatment (23.0 ± 1.9 mg GAE g−1 DM) could be achieved at 170 min and 70 °C (CSF’ = 1.91), whereas a maximum YTP of 33.0 ± 2.3 mg GAE g−1 DM was attained with the SoHy-catalyzed treatment at 90 min and 90 °C, but at almost 3.9-fold higher severity (CSF’ = 7.51). Such an outcome indicated that the SoHy-catalyzed treatment provided harsher conditions, yet it could also provide 30% higher total polyphenol yield compared to the Ur-catalyzed treatment. Thus, it was suspected that yield might be dependent on severity.

Table 2.

The various combinations of temperature and residence time used to assess the effect of severity, as estimated by the severity factor (SF) and the alternative combined severity factor (CSF’). Values of total polyphenol yield (YTP) are means (n = 3) ± standard deviation.

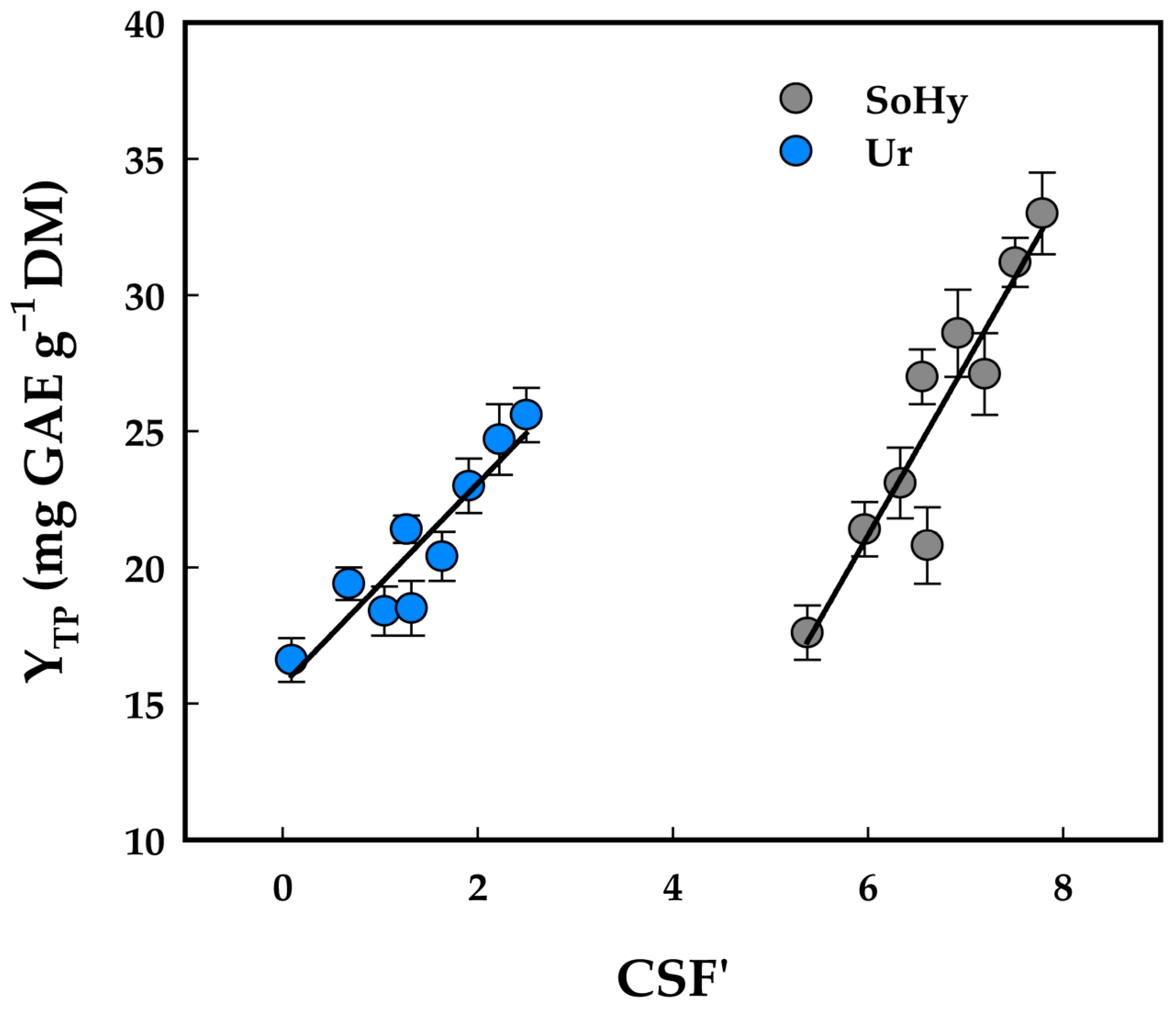

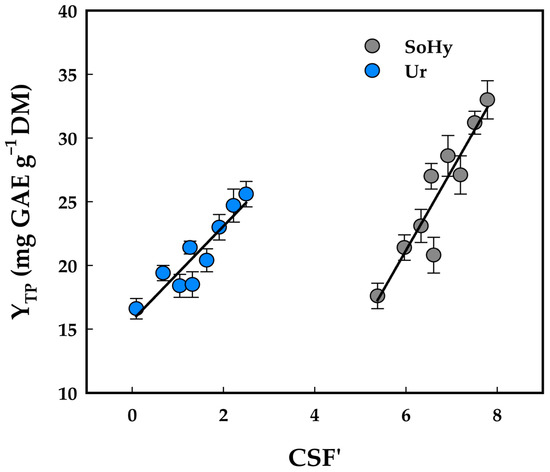

To verify this assumption, a correlation between CSF’ and YTP values was attempted. As can be seen in Figure 2, linear regression gave very satisfactory results, suggesting that YTP may be directly linked to CSF’, as shown below:

YTP(SoHy) = 6.28 CSF’ − 16.54 (R2 = 0.86, p = 0.0003)

YTP(Ur) = 3.70 CSF’ + 15.68 (R2 = 0.85, p = 0.0004)

Figure 2.

Correlation between severity, as assessed by CSF’, and yield in total polyphenols (YTP). Designations: SoHy, sodium hydroxide-catalyzed treatments; Ur, urea-catalyzed treatments.

These results were in line with previous findings on SoHy-catalyzed 1- and 2-propanol organosolv treatment of oat bran [28], and sodium carbonate-catalyzed hydrothermal treatment of wheat bran [29]. However, a study on cotton stalk ethanol organosolv treatment catalyzed by either sodium carbonate or SoHy showed that such correlations are not a general rule [30]. Therefore, the establishment of such correlations may be considered as a subject of case experimentation.

Severity is commonly used to evaluate and optimize ethanol organosolv treatments [31] and has recently been applied as a parameter for assessing process intensity in polyphenol recovery [32]. It can therefore be valuable not only for the appraisal of individual treatments, but also for enabling comparisons among them. Incorporating treatment pH into severity calculations may provide a more comprehensive understanding of severity effects [33] and extend applicability across a broad pH range [19,34]. Nevertheless, severity should be regarded only as indicative, since the impact of treatment harshness on total polyphenol yield may depend on several factors, such as the recalcitrance of the material, polyphenolic composition, and thermostability. Additionally, interactions (synergistic effects) between temperature and residence time cannot be captured solely by severity. Even so, severity can serve as a complementary criterion in selecting conditions for organosolv treatments. Ultimately, temperature, pH, and residence time must be carefully considered when designing recovery strategies, and since severity can sometimes correlate strongly with yield, it may prove to be a valuable tool for assessing treatment performance.

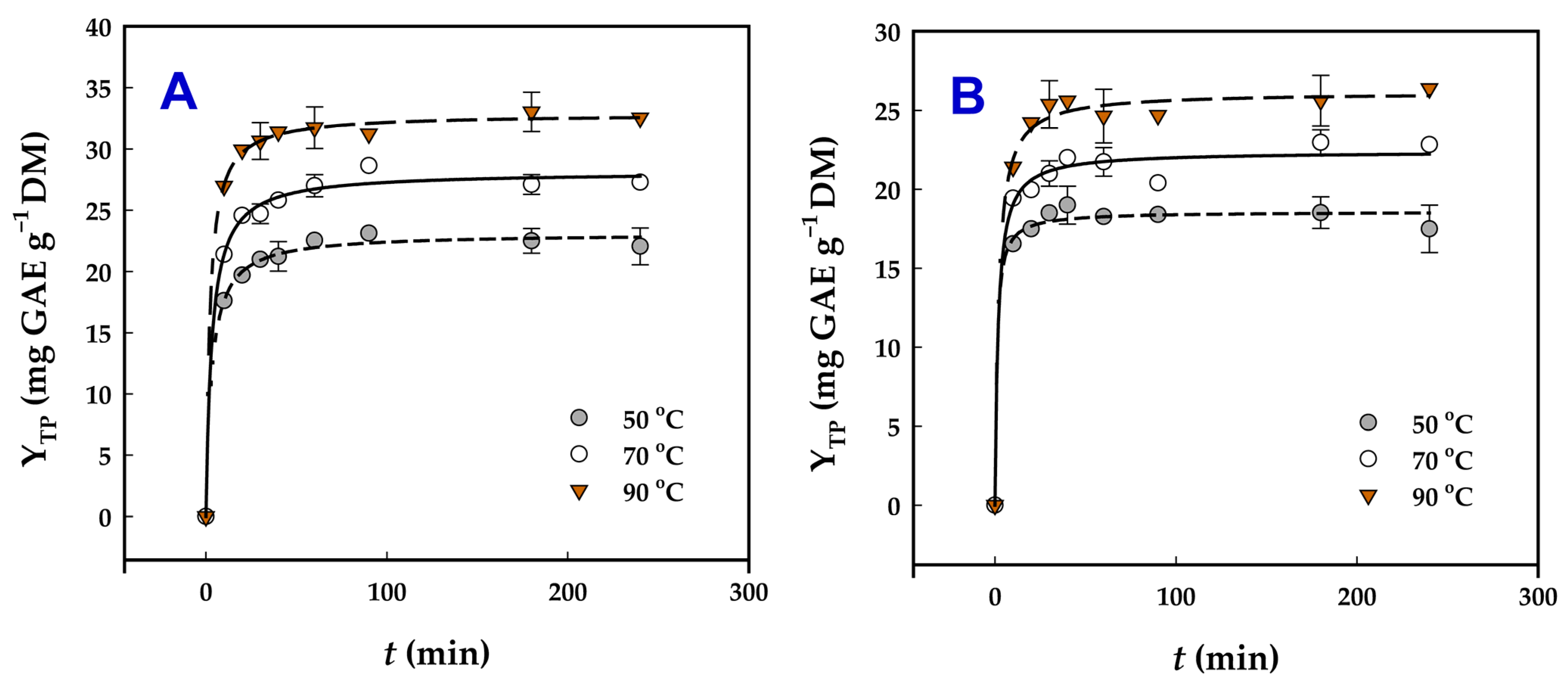

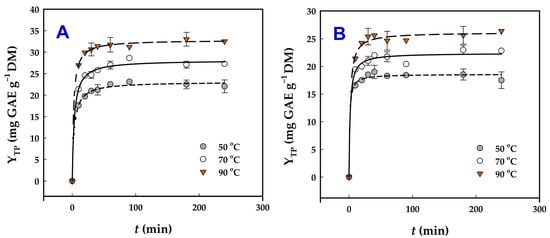

3.3. Kinetics of Polyphenol Recovery

To elucidate the influence of the two catalysts on the extractability of polyphenols from WOP, a kinetic study was conducted over a temperature range of 50–90 °C (Figure 3). The experimental data were accurately described by a first-order kinetic model, previously applied to polyphenol extraction processes [20], demonstrating excellent agreement, as evidenced by the high coefficients of determination (R2 ≥ 0.988) and p-values (<0.0001). The information derived by deploying this model is given in Table 3, and it can be noted that, for the Ur-catalyzed treatment, changing the temperature from 50 to 90 °C was in favor of increasing both the extraction rate constant, k, and YTP. In the case of SoHy-catalyzed treatment, the increase in temperature enabled the achievement of higher YTP, but at 90 °C a decline in k was observed. This finding was not in accordance with the Arrhenius model for rate–temperature relationships [35,36], which typically predicts an increase in k with rising temperature. The exact mechanism behind this kinetic behavior remains unclear, though similar findings have been documented for polyphenol extraction using deep eutectic solvents [24].

Figure 3.

Kinetics of polyphenol extraction from WOP, upon organosolv treatment (70% ethanol) using 0.5% sodium carbonate (A) and 2.5% urea (B) as catalyst.

Table 3.

First-order extraction rate constant (k) and yield in total polyphenols (YTP) obtained by performing alkali-catalyzed WOP organosolv treatments.

One possible explanation is that, at lower temperatures, easily accessible polyphenols are quickly released into the solvent, and the observed k may largely reflect this initial washing phase of the extraction. At higher temperatures, however, the situation changes: Polyphenols bound within lignocellulosic or pectin structures diffuse more slowly into the solvent, while the alkali catalyst also takes time to break down these networks for further release. Under such conditions, diffusion becomes the rate-limiting step. Consequently, mass transfer progresses more slowly, as reflected in the reduced value of k. Nonetheless, overall extraction yield (YTP(s)) still increases because the solvent accumulates polyphenols from both the rapid washing phase and the slower diffusion-driven release. In SoHy- and Ur-catalyzed treatment, the theoretical maximum YTP (YTP(s)) were 32.8 ± 2.2 and 26.1 ± 1.5 mg GAE g−1 DM, respectively, which was in absolute accordance with the results given in Table 2. This agreement brought out the validity of the predictions through the kinetic model used.

Aside from the variation in k as a response to temperature, it was also pointed out that the SoHy-catalyzed treatment enabled faster extraction rates compared to the Ur-catalyzed one. This observation might be further evidence for the ability of SoHy, in combination with ethanol, to contribute to untangling the lignocellulosic network and promoting hydrolytic/ethanolytic reactions, thereby boosting polyphenol extraction rate. Such an effect of SoHy-/ethanol on lignocellulosic recalcitrance abatement has been previously reported [37]. Although hydrothermal treatments combined with Ur have been shown to break down lignin-associated ester bonds [38], such as those occurring between hydroxycinnamates and lignin or hemicellulose, in the case examined herein the presence of Ur did not promote increased polyphenol yield. Ur may also contribute to deconstructing the lignocellulosic network [39,40], thereby facilitating polyphenol release. The deconstruction has been largely attributed to the Ur-assisted breakage of bonds interconnecting lignin with carbohydrates, such as hemicellulose [41,42]. Nevertheless, such a phenomenon, under the condition employed, most probably did not occur, as evidenced by the significantly lower YTP values obtained using Ur as the alkali catalyst.

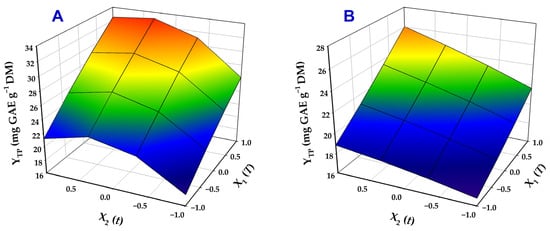

3.4. Treatment Optimization

Both the severity-based approach and the kinetic assay offered useful insights into the influence of temperature and residence time; however, they were insufficient to reveal potential synergistic effects between these variables or to estimate optimized settings for the treatment variables (t, T). To address this, a response surface methodology was applied, specifically designed to assess the impact of these critical treatment factors and to explore possible synergistic (interaction) effects. Model adequacy and suitability of the response surfaces were evaluated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and lack-of-fit tests (Figures S1 and S2), by comparing the proximity of predicted vs. experimental response values (YTP) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Data showing the combinations of organosolv treatment variables (T, t) used in the experimental design, along with the actual response (YTP) values and the predicted values obtained from the models developed using response surface methodology. SoHy and Ur correspond to sodium hydroxide and urea catalysis.

The second-order polynomial equations (mathematical models), with non-significant terms excluded, are given below, together with the overall coefficient of determination (R2), which reflects the proportion of variability explained by the models. In both cases, R2 values were ≥0.95 and p-values < 0.005, indicating an excellent fit to the experimental data.

YTP(Ur) = 20.8 + 3.0 X1 + 1.6 X2 (R2 = 0.98, p = 0.0003)

YTP(SoHy) = 28.0 + 5.0 X1 + 2.5 X2 − 3.3 X22 (R2 = 0.97, p = 0.0011)

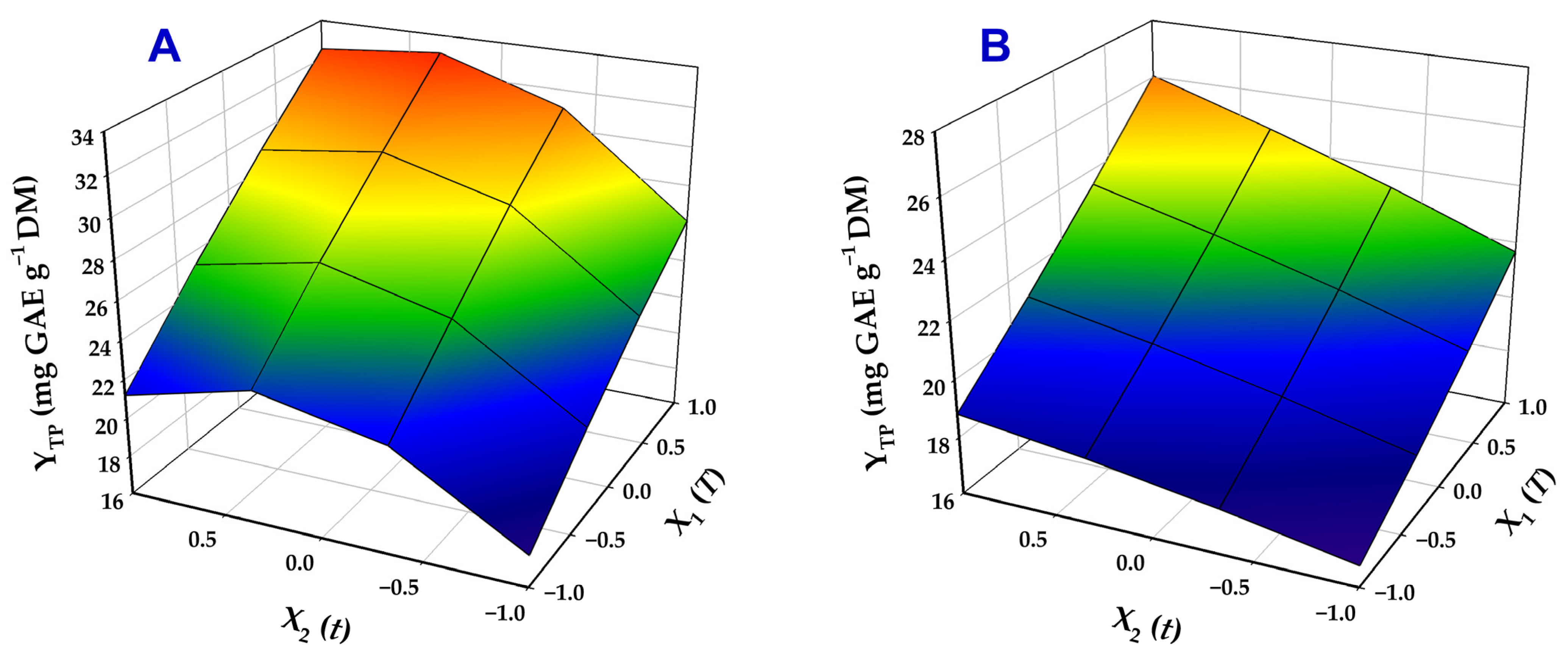

Three-dimensional plots generated from the models provided a clear visual representation of variable effects on YTP and highlighted the differences observed among the two catalysts tested (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional plots illustrating the combined influence of the treatment variables (T, t) on the total polyphenol yield (YTP). Treatments were performed with 70% ethanol containing 0.5% SoHy (A) and 2.5% Ur (B).

For both treatments, both residence time (t) and temperature (T) were highly significant factors (p < 0.005), regardless of the catalyst applied. In the case of SoHy-catalyzed treatments, the negative quadratic term of t (X22) was also significant, revealing a turning point in the role of residence time, as manifested by the curvature of the response surface (Figure 4A). This outcome suggested that, with SoHy as a catalyst, extending residence time beyond a certain point could lead to a reduction in YTP. Conversely, in Ur-catalyzed treatments, no interaction or quadratic terms were statistically significant. These results clearly highlighted that the extraction may be profoundly affected by the catalyst employed.

Application of the desirability function (Figures S1 and S2) enabled the determination of optimum conditions for maximizing YTP, which were 90 °C/130 min and 90 °C/180 min, for the SoHy- and Ur-catalyzed treatment, respectively. Under these conditions, the corresponding maximum predicted YTP were 33.4 ± 1.7 and 26.0 ± 1.6 mg GAE g−1 DM, which closely matched the experimental data (Table 3) and confirmed the robustness of the developed models. To further validate the reliability of the theoretical optimum settings, three independent treatments were conducted for each catalyst. The resulting YTP values were 31.6 ± 0.7 and 24.2 ± 1.4 mg GAE g−1 DM, for the SoHy-, and Ur-catalyzed treatments, respectively. These findings supported the conclusion that the models represented by Equations (8) and (9) could accurately predict YTP, provided that both t and T remain within the tested ranges.

The SoHy-catalyzed treatment yielded a YTP of 33.4 mg GAE g−1 DM, which can be considered satisfactory given that the literature values often range between 7 and 26 mg GAE g−1 DM when employing methods such as cyclodextrin-assisted extraction [43], ultrasound-assisted extraction [44], and microwave-assisted extraction [45]. In contrast, the highest YTP values reported to date (73.4–75.8 mg GAE g−1 DM) have been achieved using deep eutectic solvents [22,46], while intermediate levels of around 44.1 mg GAE g−1 DM have been obtained through glycerol-based WOP organosolv treatment [26], at temperatures higher than 120 °C.

3.5. Polyphenolic Composition and Antioxidant Activity

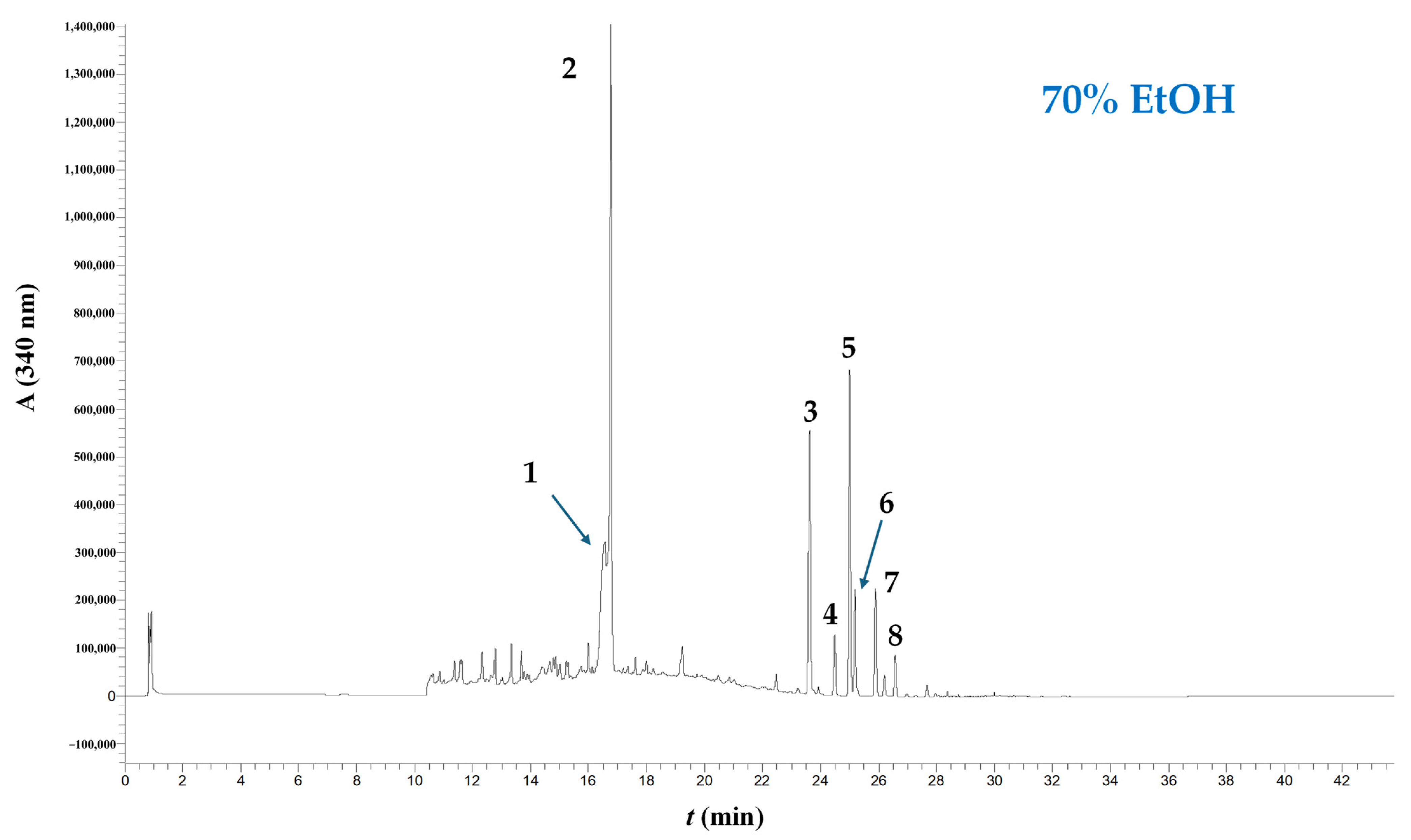

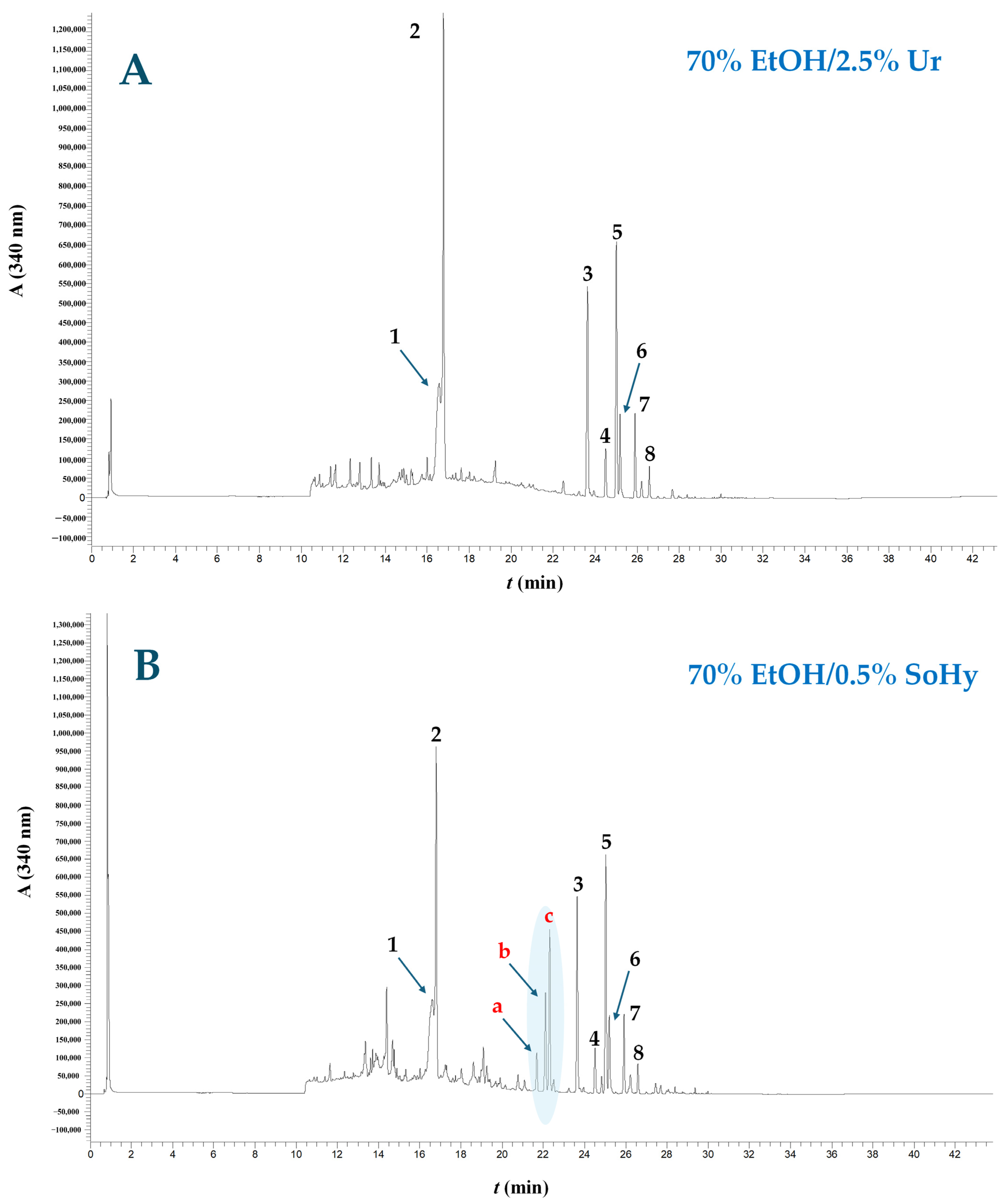

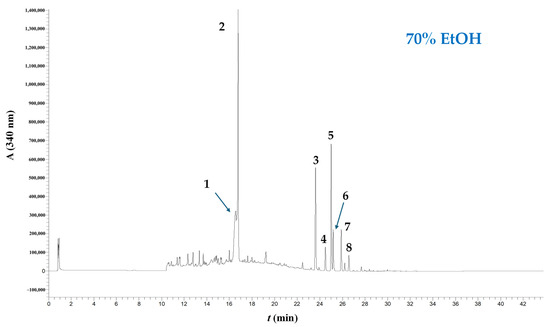

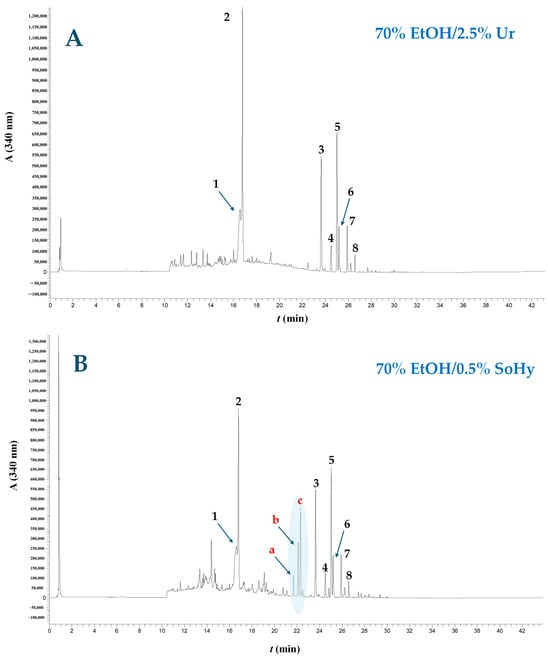

To better understand the impact of the alkali catalysts tested on the polyphenolic composition, extracts obtained under optimized conditions, along with an extract made without any catalyst (using only 70% ethanol), were analyzed using LC-DAD-MS/MS. The extract produced without a catalyst (only 70% ethanol) displayed the chromatographic profile shown in Figure 5. Likewise, the extract generated by applying Ur catalysis exhibited no changes in composition compared to neat 70% ethanol treatment (Figure 6A). Peaks 1 and 2 were identified as narirutin and hesperidin, using commercial standards, but their identity was also confirmed by their molecular ions, which were m/z = 579 and 609, respectively (negative ionization mode). In positive ionization mode, peaks 3–8 gave corresponding molecular ions of m/z = 373, 403, 373, 433, 343, and 373, and based on previously provided information [26,47], their corresponding tentative identities were sinensetin, nobiletin, tangeretin, heptamethoxyflavone, tetramethoxyflavonol, and a sinensetin or tangeretin isomer (Table 5).

Figure 5.

Chromatographic profile of WOP extract obtained through treatment with 70% ethanol (no catalyst added). The trace was recorded at 340 nm. Peak assignment: 1, narirutin; 2, hesperidin; 3, sinensetin; 4, nobiletin; 5, tangeretin; 6, heptamethoxyflavone; 7, tetramethoxyflavonol; 8, sinensetin or tangeretin isomer. Treatment was accomplished at 90 °C, for 180 min.

Figure 6.

Chromatographic profiles of WOP extracts obtained through treatment with 70% ethanol, using Ur (A) and SoHy (B) as catalyst. The trace was recorded at 340 nm. Peak assignment: 1, narirutin; 2, hesperidin; 3, sinensetin; 4, nobiletin; 5, tangeretin; 6, heptamethoxyflavone; 7, tetramethoxyflavonol; 8, sinensetin or tangeretin isomer. Peaks a, b and c correspond to the ethyl esters of p-coumaric, ferulic and sinapic acids. Treatments were accomplished under optimized conditions (90 °C/130 min and 90 °C/180 min for the SoHy and Ur catalysis, respectively).

Table 5.

Information related to the tentative identification of the principal peaks observed in the WOP extracts.

On the other hand, the extract produced with 70% ethanol/0.5% SoHy as catalyst displayed a noticeable modification in composition, as three additional prominent peaks, assigned as a, b, and c, appeared in the chromatogram (Figure 6B). On the ground of the information derived from the LC-DAD-MS/MS analyses (Table 5), their corresponding tentative identities were ethyl p-coumarate, ethyl ferulate and ethyl sinapate. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, these compounds have never been previously reported as natural WOP constituents, and it was thus hypothesized that they were generated through the SoHy-catalyzed ethanol organosolv treatment. It would appear that, in the presence of ethanol, SoHy catalysis provoked the ethanolysis of cell wall-bound hydroxycinnamates, giving rise to the formation of a, b and c derivatives (Figure 6B). Since bound phenolics in plant tissues are frequently attached onto polysaccharide (e.g., hemicellulose) networks via esters bonds [14], the conditions employed and the presence of both SoHy and ethanol facilitated interesterification, leading to the formation of ethanol esters. On the other hand, the weak alkaline environment brought about by the use of Ur did not suffice to catalyze such reactions.

In relation to the superior performance of the treatments observed in the presence of SoHy, it appears that the efficient hydrolysis of ester bonds linking hydroxycinnamates to polysaccharides (e.g., hemicellulose) necessitates a more potent catalytic environment. Given that SoHy is a stronger and more reactive base, it can more effectively cleave lignin–hemicellulose linkages, disrupt the lignin–carbohydrate matrix, and facilitate the release of bound hydroxycinnamates through the cleavage of ester bonds. Conversely, Ur exerts a milder catalytic effect, which might result in less pronounced degradation of lignin–polysaccharide complexes, reduced disruption of recalcitrant lignin/ester linkages, and consequently, a more limited or no liberation of hydroxycinnamates.

Bound phenolics have long been known to occur in orange peel, the main representatives being, in the order of abundance, ferulic acid, sinapic acid, p-coumaric acid and caffeic acid [48,49,50,51], while their content may be a subject of intense fluctuations during fruit ripening. These compounds may be liberated upon treatment with SoHy, and they represent a notable portion of the overall polyphenolic load. It has been reported that the bound polyphenol fraction in orange peels may account for almost 40% of the total polyphenolic content and be responsible for strong antioxidant effects [52]. However, in other cases, bound phenolics might be the largest part of the total polyphenolic amount occurring in citrus peels [53].

To gain a deeper understanding of the effects of alkali catalysis on the polyphenolic profile of WOP extracts, a quantitative assay was also performed, and the data produced are analytically presented in Table 6. With regard to flavanone fraction, Ur catalysis had no detectable effect on narirutin and hesperidin yield compared to neat 70% ethanol treatment (p > 0.05), but SoHy catalysis did cause a significant reduction in both (p < 0.05), and in the majority of flavones. Furthermore, the SoHy-catalyzed treatment triggered the formation of ethyl p-coumarate, ferulate and sinapate. Thus, the extract generated with the SoHy-catalysis had lower flavanone and flavone concentrations, yet it was significantly enriched in the hydroxycinnamate ethyl esters and had an almost 30% higher total polyphenol concentration compared to the extract obtained with neat 70% ethanol.

Table 6.

Quantitative data for the main compounds identified in WOP extracts obtained using organosolv treatments with 2.5% urea (Ur) and 0.5% sodium hydroxide (SoHy) as catalysts. Treatments were accomplished under optimized conditions (90 °C/130 min and 90 °C/180 min for the SoHy and Ur catalysis, respectively).

In some plant tissues, i.e., wheat bran and straw, hydroxycinnamates such as ferulic acid are attached to arabinoxylan components of the cell wall through ester bonds [54]. These bonds are susceptible to alkaline hydrolysis, which leads to increased release of hydroxycinnamates [55]. In such materials, hydroxycinnamates can also serve as a cross-linking agents between polysaccharides and lignins. In this case, they are bound to polysaccharides via alkali-sensitive ester bonds [56]. Hydroxycinnamates may also be part of the lignin structure, where they are connected by ester bonds. Consequently, breaking down lignin could assist hydroxycinnamate release. The role of ethanol is important in this process, as it aids lignin solubilization and enhances the accessibility of sodium hydroxide to ester bonds, which is a key step in the hydrolysis process [31]. On the other hand, transesterification that would lead to the formation of hydroxycinnamate ethyl esters has not been reported in recent relevant examinations [16,30]; thus, the detection of these substances could most probably be ascribed to the increased ethanol concentration (70%) used in the work herein.

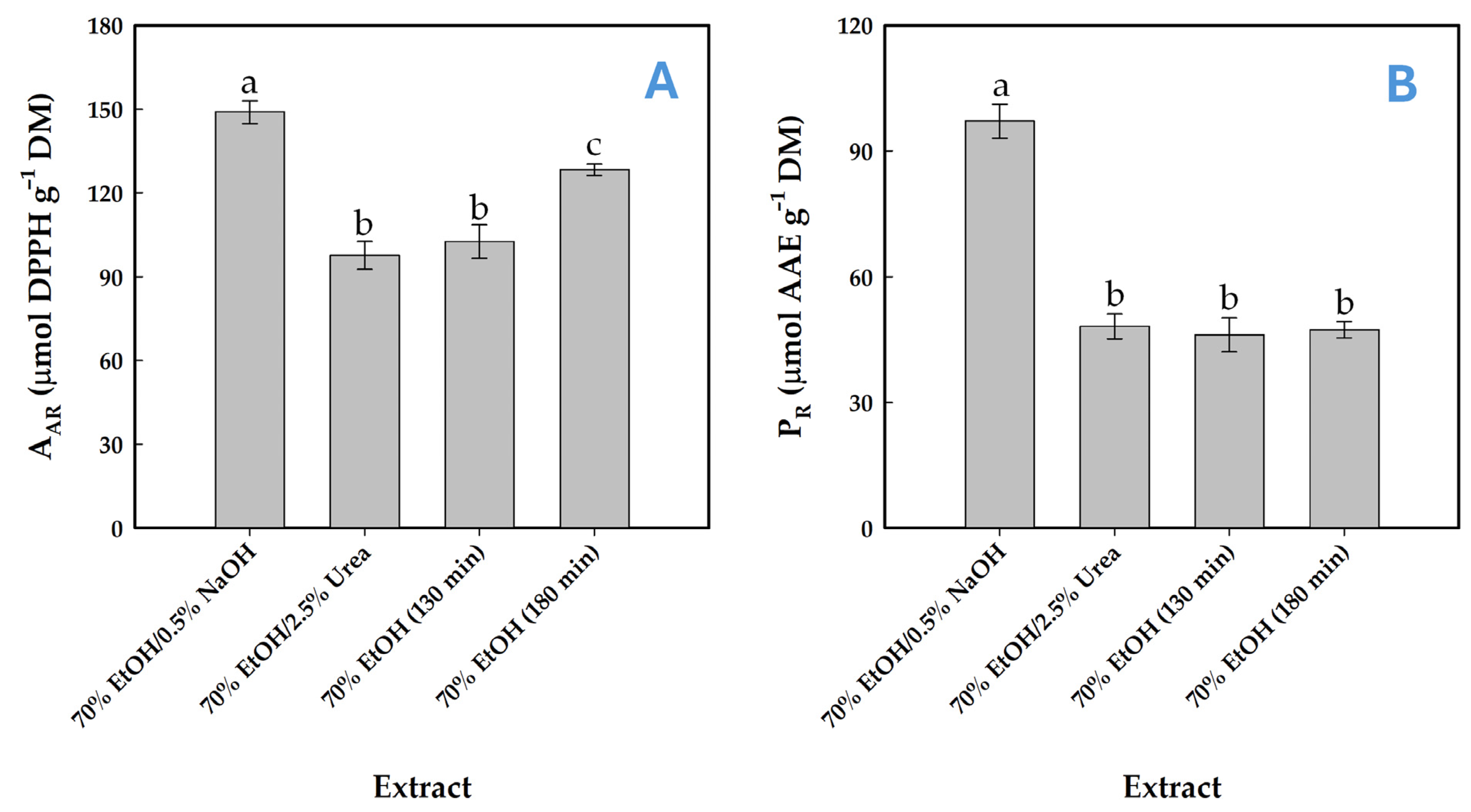

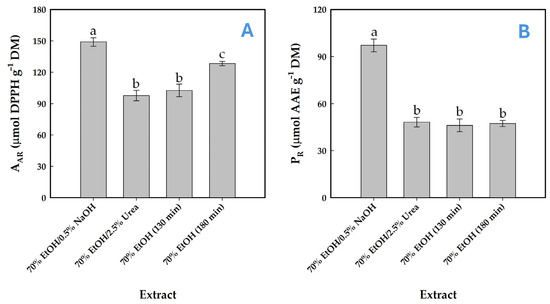

To elucidate whether these compositional differences could exert a notable effect on the antioxidant activity, the antiradical activity (AAR) and the ferric-reducing power (PR) of the resulting extracts were investigated. The extract obtained via SoHy-catalyzed treatment, which exhibited a higher total polyphenol concentration, demonstrated markedly greater antioxidant potency in both tests (Figure 7A,B). This finding indicated that polyphenol concentration might be a key determinant in the expression of antioxidants effects in the extract produced. This argument is in consistency with earlier results on WOP extracts, where high polyphenol concentration coincided with high levels of both AAR and PR [22,26,57]. However, other works failed to provide evidence for such a correlation [43,58].

Figure 7.

Determination of antiradical activity (A) and reducing power (B) in WOP extracts obtained from organosolv treatments using sodium hydroxide (SoHy) and urea (Ur) as catalysts. Values marked with different lowercase letters (a–c) indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05). Treatments were accomplished under optimized conditions (90 °C/130 min and 90 °C/180 min for the sodium hydroxide and urea catalysis, respectively). Control treatments with 70% ethanol (no catalyst added) were performed at 90 °C and for both 130 and 180 min residence time.

Hesperidin is a flavonoid with well-documented antioxidant activity [59], and its abundance suggests that it may be a principal contributor to the antioxidant capacity of the tested extracts. Its strong antioxidant efficacy has been consistently demonstrated in chemical assays [60] and in vitro studies [61]. In the extracts produced, the differences in hesperidin concentration were low, and thus differences in the antioxidant activity could not be attributed to the effect of hesperidin. On the other hand, the important compositional difference in the extract produced through the SoHy-catalyzed treatment was the presence of the three hydroxycinnamate esters. Therefore, it could be speculated that the increased antioxidant potency found for the extracts obtained with the SoHy-catalyzed treatment might be to some extent due to the effect of these substances. Although all three hydroxycinnamate esters had lower concentration compared to hesperidin, their contribution to antioxidant activity should not be overlooked. Recent research into the antioxidant properties of orange peel extracts has demonstrated that, although some polyphenols are present in lower concentrations, they exhibit greater antioxidant efficacy compared to the more abundant WOP constituents [62]. The authors further proposed that the polyphenols found in orange peel extracts predominantly function via a single-electron transfer (SET) mechanism, rather than through hydrogen atom transfer (HAT).

It has long been recognized that ethyl esterification of phenolic acids such as caffeic, ferulic and sinapic [63] may significantly boost their antioxidant potency. Such a trend was also confirmed by subsequent studies on glucose esters of ferulic and sinapic acid [64]. Nevertheless, other examinations suggested that esterification may indeed improve caffeic acid performance, but not that of ferulic acid [65], while a following investigation revealed variable behavior of caffeic, ferulic and p-coumaric acid alkyl esters, depending on the chain length of the fatty alcohol used for esterification [66]. On this basis, it could also be possible that the ethyl esters of p-coumaric, ferulic and sinapic acid, found in the extract obtained through the SoHy-catalyzed treatment might display increased antioxidant activity, and this could explain the more power antioxidant effects of this extract. Further to that, it should be underlined that orange polyphenols have been demonstrated to manifest various synergistic and antagonistic effects [67]. The manifestation of such phenomena might be critical to the expression of antioxidant activity, since, in general, antioxidant activity represents the cumulative contribution of individual polyphenols in conjunction with the potential antagonistic or synergistic interactions occurring among them [68,69,70]. Consequently, it is not feasible to accurately predict the overall biological effect based solely on the concentration of specific polyphenolic compounds.

4. Conclusions

Testing two alkali catalysts, a mild (Ur) and a strong (SoHy) one, in the ethanol organosolv treatment of WOP, demonstrated that SoHy was significantly more effective than Ur in delivering extracts enriched in polyphenolic substances. This treatment showed greater severity and caused notable alterations in the natural polyphenolic profile of WOP, which were shown to provoke a significant enhancement of the antioxidant activity of the extracts produced, by triggering the formation of hydroxycinnamate ethyl esters. This effect can be seen as advantageous, as it allows treatment conditions to be tailored depending on the intended outcome. Overall, the study demonstrated that alkali-catalyzed ethanol organosolv treatment is a promising strategy for recovering bioactive polyphenols from WOP, but also for enriching the polyphenolic composition with newly formed potent antioxidants. This should be a subject of a more scrutinized future study, to further develop such a promising methodology. These findings highlight the potential of WOP valorization within broader biorefinery frameworks, paving the way for targeted processes that enable efficient utilization of WOP to produce high-value products.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/environments13020120/s1, Figure S1: Statistical data related to the response surface methodology, deployed to optimize the SoHy-catalyzed treatment. (A) Correlation between actual (measured) and predicted values; (B) desirability function; numbers designated with different color in the inset tables denote statistically different values (p < 0.05). Figure S2: Statistical data related to the response surface methodology, deployed to optimize the Ur-catalyzed treatment. (A) correlation between actual (measured) and predicted values; (B) desirability function; numbers designated with different color in the inset tables denote statistically different values (p < 0.05).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.P.M. and S.G.; methodology, D.P.M., S.G., H.R. and H.A.; validation, S.G., H.R. and H.A.; formal analysis, S.G., H.R. and H.A.; investigation, S.G., H.R. and H.A.; resources, S.G.; data curation, D.P.M., S.G., H.R. and H.A.; writing—original draft preparation, D.P.M. and S.G.; writing—review and editing, D.P.M. and S.G.; visualization, D.P.M. and S.G.; supervision, D.P.M. and S.G.; project administration, S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAR | antiradical activity (μmol DPPH g−1 DM) |

| CSF | combined severity factor |

| CSF’ | alternative combined severity factor |

| DM | dry mass (g) |

| EtOH | ethanol |

| GAEs | gallic acid equivalents |

| PR | reducing power (μmol ascorbic acid equivalents g−1 DM) |

| SoHy | sodium hydroxide |

| T | time (min) |

| T | temperature (°C) |

| Ur | urea |

| YTP | yield in total polyphenols (mg GAE g−1 DM) |

| WOPs | waste orange peels |

References

- Lizárraga-Velázquez, C.E.; Leyva-López, N.; Hernández, C.; Gutiérrez-Grijalva, E.P.; Salazar-Leyva, J.A.; Osuna-Ruíz, I.; Martínez-Montaño, E.; Arrizon, J.; Guerrero, A.; Benitez-Hernández, A. Antioxidant molecules from plant waste: Extraction techniques and biological properties. Processes 2020, 8, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, L.L.D.R.; Flórez-López, E.; Grande-Tovar, C.D. The potential of selected agri-food loss and waste to contribute to a circular economy: Applications in the food, cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries. Molecules 2021, 26, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, R.; Sales, H.; Pontes, R.; Nunes, J.; Gouveia, I. Food wastes and microalgae as sources of bioactive compounds and pigments in a modern biorefinery: A review. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahidi, F.; Varatharajan, V.; Oh, W.Y.; Peng, H. Phenolic compounds in agri-food by-products, their bioavailability and health effects. J. Food Bioact. 2019, 5, 57–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassoff, E.S.; Guo, J.X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.C.; Li, Y.O. Potential development of non-synthetic food additives from orange processing by-products—A review. Food Qual. Saf. 2021, 5, fyaa035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadar, S.S.; Rao, P.; Rathod, V.K. Enzyme assisted extraction of biomolecules as an approach to novel extraction technology: A review. Food Res. Inter. 2018, 108, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Huang, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, D.; Fan, J. A review of the polyphenols extraction from apple pomace: Novel technologies and techniques of cell disintegration. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 9752–9765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, T.R.; Pattnaik, F.; Nanda, S.; Dalai, A.K.; Meda, V.; Naik, S. Hydrothermal pretreatment technologies for lignocellulosic biomass: A review of steam explosion and subcritical water hydrolysis. Chemosphere 2021, 284, 131372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Lin, R.; Lam, C.H.; Wu, H.; Tsui, T.-H.; Yu, Y. Recent advances and challenges of inter-disciplinary biomass valorization by integrating hydrothermal and biological techniques. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lee, D.-J. Lignocellulosic biomass pretreatment by deep eutectic solvents on lignin extraction and saccharification enhancement: A review. Biores. Technol. 2021, 339, 125587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei Kit Chin, D.; Lim, S.; Pang, Y.L.; Lam, M.K. Fundamental review of organosolv pretreatment and its challenges in emerging consolidated bioprocessing. Biofuels Bioprod. Bioref. 2020, 14, 808–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borand, M.N.; Karaosmanoğlu, F. Effects of organosolv pretreatment conditions for lignocellulosic biomass in biorefinery applications: A review. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2018, 10, 033104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, A.; Razavi, S.H. The role of bioconversion processes to enhance bioaccessibility of polyphenols in rice. Food Biosci. 2020, 35, 100605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Estrada, B.A.; Gutiérrez-Uribe, J.A.; Serna-Saldívar, S.O. Bound phenolics in foods, a review. Food Chem. 2014, 152, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bento-Silva, A.; Patto, M.C.V.; do Rosário Bronze, M. Relevance, structure and analysis of ferulic acid in maize cell walls. Food Chem. 2018, 246, 360–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadaki, E.S.; Palaiogiannis, D.; Lalas, S.I.; Mitlianga, P.; Makris, D.P. Polyphenol release from wheat bran using ethanol-based organosolv treatment and acid/alkaline catalysis: Process modeling based on severity and response surface optimization. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, F.P.; Jin, S.; Paggiola, G.; Petchey, T.H.; Clark, J.H.; Farmer, T.J.; Hunt, A.J.; Robert McElroy, C.; Sherwood, J. Tools and techniques for solvent selection: Green solvent selection guides. Sustain. Chem. Proc. 2016, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overend, R.P.; Chornet, E. Fractionation of lignocellulosics by steam-aqueous pretreatments. Phil. Transac. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1987, 321, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, M.; Meyer, A.S. Lignocellulose pretreatment severity–relating pH to biomatrix opening. New Biotech. 2010, 27, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harouna-Oumarou, H.A.; Fauduet, H.; Porte, C.; Ho, Y.-S. Comparison of kinetic models for the aqueous solid-liquid extraction of Tilia sapwood in a continuous stirred tank reactor. Chem. Eng. Com. 2007, 194, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, M.A.; Ferreira, S.L.C.; Novaes, C.G.; Dos Santos, A.M.P.; Valasques, G.S.; da Mata Cerqueira, U.M.F.; dos Santos Alves, J.P. Simultaneous optimization of multiple responses and its application in Analytical Chemistry–A review. Talanta 2019, 194, 941–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalompatsios, D.; Palaiogiannis, D.; Makris, D.P. Optimized production of a hesperidin-enriched extract with enhanced antioxidant activity from waste orange peels using a glycerol/sodium butyrate deep eutectic solvent. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicco, N.; Lanorte, M.T.; Paraggio, M.; Viggiano, M.; Lattanzio, V. A reproducible, rapid and inexpensive Folin–Ciocalteu micro-method in determining phenolics of plant methanol extracts. Microchem. J. 2009, 91, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakka, A.; Karageorgou, I.; Kaltsa, O.; Batra, G.; Bozinou, E.; Lalas, S.; Makris, D. Polyphenol extraction from Humulus lupulus (hop) using a neoteric glycerol/L-alanine deep eutectic solvent: Optimisation, kinetics and the effect of ultrasound-assisted pretreatment. AgriEngineering 2019, 1, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulou, M.A.; Kefalas, P.; Kokkalou, E.; Assimopoulou, A.N.; Papageorgiou, V.P. Analysis of antioxidant compounds in sweet orange peel by HPLC–diode array detection–electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Biomed. Chrom. 2005, 19, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoun, R.; Grigorakis, S.; Kellil, A.; Loupassaki, S.; Makris, D.P. Process optimization and stability of waste orange peel polyphenols in extracts obtained with organosolv thermal treatment using glycerol-based solvents. ChemEngineering 2022, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casasni, S.; Guenaoui, A.; Grigorakis, S.; Makris, D.P. Acid-catalyzed organosolv treatment of potato peels to boost release of polyphenolic compounds using 1-and 2-propanol. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenaoui, A.; Casasni, S.; Grigorakis, S.; Makris, D.P. Alkali-catalyzed organosolv treatment of oat bran for enhanced release of hydroxycinnamate antioxidants: Comparison of 1-and 2-propanol. Environments 2023, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadaki, E.; Grigorakis, S.; Palaiogiannis, D.; Lalas, S.I.; Mitlianga, P. Hydrothermal treatment of wheat bran under mild acidic or alkaline conditions for enhanced polyphenol recovery and antioxidant activity. Molecules 2024, 29, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, G.; Zarnavalou, V.; Chatzimitakos, T.; Palaiogiannis, D.; Athanasiadis, V.; Lalas, S.I.; Makris, D.P. Comparison of sodium hydroxide and sodium carbonate as alkali catalysts in ethanol organosolv treatment of cotton stalks for the release of hydroxycinnamates. Recycling 2024, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Lei, F.; Li, P.; Jiang, J. Lignocellulosic biomass to biofuels and biochemicals: A comprehensive review with a focus on ethanol organosolv pretreatment technology. Biotech. Bioeng. 2018, 115, 2683–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pazo-Cepeda, M.V.; Aspromonte, S.G.; Alonso, E. Extraction of ferulic acid and feruloylated arabinoxylo-oligosaccharides from wheat bran using pressurized hot water. Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, N.; Richel, A. Adaptation of severity factor model according to the operating parameter variations which occur during steam explosion process. In Hydrothermal Processing in Biorefineries: Production of Bioethanol and High Added-Value Compounds of Second and Third Generation Biomass; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 333–351. [Google Scholar]

- Svärd, A.; Brännvall, E.; Edlund, U. Rapeseed straw polymeric hemicelluloses obtained by extraction methods based on severity factor. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 95, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, M.; Engel, R.; Gonzalez-Martinez, C.; Corradini, M.G. Non-Arrhenius and non-WLF kinetics in food systems. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2002, 82, 1346–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-H.; Yusoff, R.; Ngoh, G.-C. Modeling and kinetics study of conventional and assisted batch solvent extraction. Chem. Eng. Res. Design 2014, 92, 1169–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Xie, J.; Qin, Y. Effects of NaOH-catalyzed organosolv pretreatment and surfactant on the sugar production from sugarcane bagasse. Biores. Technol. 2020, 312, 123601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yuan, H.; Yan, B.; Zuo, X.; Li, X. Improved performance of corn stover anaerobic digestion by low-temperature hydrothermal pretreatment with urea enhancement. Biomass Bioen. 2022, 164, 106553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, K.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, D. High-solid pretreatment of corn stover using urea for enzymatic saccharification. Biores. Technol. 2018, 259, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Bergeron, A.D.; Davaritouchaee, M. Methane recovery from anaerobic digestion of urea-pretreated wheat straw. Renew. Energy 2018, 115, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado-Pacheco, J.; Julio-Altamiranda, Y.; Sánchez-Tuirán, E.; González-Delgado, Á.D.; Ojeda, K.A. Variables affecting delignification of corn wastes using urea for total reducing sugars production. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 12196–12201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cao, Z.; Zou, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z. Urea-pretreated corn stover: Physicochemical characteristics, delignification kinetics, and methane production. Biores. Technol. 2020, 306, 123097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakka, A.; Lalas, S.; Makris, D.P. Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin as a green co-solvent in the aqueous extraction of polyphenols from waste orange peels. Beverages 2020, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmau, E.; Rosselló, C.; Eim, V.; Ratti, C.; Simal, S. Ultrasound-assisted aqueous extraction of biocompounds from orange byproduct: Experimental kinetics and modeling. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M’hiri, N.; Ioannou, I.; Boudhrioua, N.M.; Ghoul, M. Effect of different operating conditions on the extraction of phenolic compounds in orange peel. Food Bioprod. Proc. 2015, 96, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Urios, C.; Viñas-Ospino, A.; Penadés-Soler, A.; Lopez-Malo, D.; Frígola, A.; Esteve, M.; Blesa, J. Natural deep eutectic solvents as main solvent for the extraction of total polyphenols of orange peel. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2021, 6, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifi, S.M.; Gök, R.; Eikenberg, I.; Krygier, D.; Rottmann, E.; Stübler, A.-S.; Aganovic, K.; Hillebrand, S.; Esatbeyoglu, T. Comparative flavonoid profile of orange (Citrus sinensis) flavedo and albedo extracted by conventional and emerging techniques using UPLC-IMS-MS, chemometrics and antioxidant effects. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1158473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, H.; Naim, M.; Rouseff, R.L.; Zehavi, U. Distribution of bound and free phenolic acids in oranges (Citrus sinensis) and grapefruits (Citrus paradisi). J. Sci. Food Agric. 1991, 57, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocco, A.; Cuvelier, M.-E.; Richard, H.; Berset, C. Antioxidant activity and phenolic composition of citrus peel and seed extracts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 2123–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alu’Datt, M.H.; Rababah, T.; Alhamad, M.N.; Al-Mahasneh, M.A.; Ereifej, K.; Al-Karaki, G.; Al-Duais, M.; Andrade, J.E.; Tranchant, C.C.; Kubow, S. Profiles of free and bound phenolics extracted from Citrus fruits and their roles in biological systems: Content, and antioxidant, anti-diabetic and anti-hypertensive properties. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 3187–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Guo, Z.; Feng, X.; Huang, P.; Du, M.; Zalan, Z.; Kan, J. Distribution and natural variation of free, esterified, glycosylated, and insoluble-bound phenolic compounds in brocade orange (Citrus sinensis L. Osbeck) peel. Food Res. Inter. 2022, 153, 110958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oboh, G.; Ademosun, A. Characterization of the antioxidant properties of phenolic extracts from some citrus peels. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 49, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmus, N.; Gulsunoglu-Konuskan, Z.; Kilic-Akyilmaz, M. Recovery, Bioactivity, and Utilization of Bioactive Phenolic Compounds in Citrus Peel. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 9974–9997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, D.M.; Finger-Teixeira, A.; Rodrigues Mota, T.; Salvador, V.H.; Moreira-Vilar, F.C.; Correa Molinari, H.B.; Craig Mitchell, R.A.; Marchiosi, R.; Ferrarese-Filho, O.; Dantas dos Santos, W. Ferulic acid: A key component in grass lignocellulose recalcitrance to hydrolysis. Plant Biotech. J. 2015, 13, 1224–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buranov, A.U.; Mazza, G. Lignin in straw of herbaceous crops. Ind. Crops Prod. 2008, 28, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linh, T.N.; Fujita, H.; Sakoda, A. Release kinetics of esterified p-coumaric acid and ferulic acid from rice straw in mild alkaline solution. Biores. Technol. 2017, 232, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Wu, Y.; Liu, D.; Sheng, Z.; Liu, J.; Chen, H.; Feng, W. The kinetic behavior of antioxidant activity and the stability of aqueous and organic polyphenol extracts from navel orange peel. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e90621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalompatsios, D.; Athanasiadis, V.; Palaiogiannis, D.; Lalas, S.I.; Makris, D.P. Valorization of waste orange peels: Aqueous antioxidant polyphenol extraction as affected by organic acid addition. Beverages 2022, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-S.; Lee, S.-H.; Lee, K.-A. A comparative study of hesperetin, hesperidin and hesperidin glucoside: Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial activities in vitro. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaze, F.I.; Termentzi, A.; Gabrieli, C.; Niopas, I.; Georgarakis, M.; Kokkalou, E. The phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity assessment of orange peel (Citrus sinensis) cultivated in Greece–Crete indicates a new commercial source of hesperidin. Biomed. Chrom. 2009, 23, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Ikram, M.; Hahm, J.R.; Kim, M.O. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of citrus flavonoid hesperetin: Special focus on neurological disorders. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.T.; Rodríguez Mellado, J.M. Spectrophotometric and Electrochemical Assessment of the Antioxidant Capacity of Aqueous and Ethanolic Extracts of Citrus Flavedos. Oxygen 2022, 2, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalas, J.; Claise, C.; Edeas, M.; Messaoudi, C.; Vergnes, L.; Abella, A.; Lindenbaum, A. Effect of ethyl esterification of phenolic acids on low-density lipoprotein oxidation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2001, 55, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kylli, P.; Nousiainen, P.; Biely, P.; Sipilä, J.; Tenkanen, M.; Heinonen, M. Antioxidant potential of hydroxycinnamic acid glycoside esters. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 4797–4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, J.; Gaspar, A.; Garrido, E.M.; Miri, R.; Tavakkoli, M.; Pourali, S.; Saso, L.; Borges, F.; Firuzi, O. Alkyl esters of hydroxycinnamic acids with improved antioxidant activity and lipophilicity protect PC12 cells against oxidative stress. Biochimie 2012, 94, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, A.-D.M.; Durand, E.; Laguerre, M.; Bayrasy, C.; Lecomte, J.; Villeneuve, P.; Jacobsen, C. Antioxidant properties and efficacies of synthesized alkyl caffeates, ferulates, and coumarates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 12553–12562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, B.L.; Eggett, D.L.; Parker, T.L. Synergistic and antagonistic interactions of phenolic compounds found in navel oranges. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, C570–C576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, H.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Chung, D.; Kim, D.-O. Antioxidant capacities of individual and combined phenolics in a model system. Food Chem. 2007, 104, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Samra, M.; Chedea, V.S.; Economou, A.; Calokerinos, A.; Kefalas, P. Antioxidant/prooxidant properties of model phenolic compounds: Part I. Studies on equimolar mixtures by chemiluminescence and cyclic voltammetry. Food Chem. 2011, 125, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choueiri, L.; Chedea, V.S.; Calokerinos, A.; Kefalas, P. Antioxidant/pro-oxidant properties of model phenolic compounds. Part II: Studies on mixtures of polyphenols at different molar ratios by chemiluminescence and LC–MS. Food Chem. 2012, 133, 1039–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.