Abstract

The growing demand for carbon-based energy materials requires sustainable alternatives to fossil fuels. This study explored the production and characterization of char obtained from refuse-derived fuel (RDF) and biomass blended pellets in varying proportions (0%, 15%, 25%, 50%, and 100% RDF). The objective was to evaluate their potential as high-energy-density solid fuels while addressing operational challenges related to ash behavior. Chars were produced at 400 °C for one hour in a muffle furnace in closed crucibles. A set of analytical techniques (calorimetry, infrared spectroscopy, thermogravimetry, inductively coupled plasma, and X-ray fluorescence) was employed to assess physicochemical properties. RDF content strongly affected mass yield, energy yield, and thermochemical behavior. Among the tested formulations, char with 50 and 25% of RDF (C_RDF50:BW50 and C_RDF25:BW75) ignited at lower temperatures (≈150 °C) and showed high flammability (C) values (1.97–2.03 × 10−5), indicating greater flammability. They also reached higher combustion temperatures (716–746 °C), suggesting improved thermal stability during the final combustion stage. Both chars presented increased high heating values (18–19 MJ/kg, dry basis) and a few surface functional groups. This supports a lower devolatilization rate, meaning that although ignition is easy, combustion remains stable and controllable. All chars showed very high acid–base indices, indicating a strong tendency for ash melting. However, low slag viscosity and alkalinity values suggest viscous, poorly mobile slag, reducing adhesion and buildup on reactor surfaces. This study combines thermogravimetric combustion analysis with ash chemistry–based slagging and fouling indices to provide an integrated assessment of the operational behavior of RDF–biomass-derived char fuels. The results highlight the technical feasibility of chars produced from RDF and biomass blended pellets, whose thermal properties make them promising candidates for use as solid fuels.

1. Introduction

As the energy transition and the sustainability of materials have drawn global concern, understanding how to replace current fossil–carbon-based energetic materials requires discovering innovative pathways supported by the integration of more sustainable materials. According to Chen et al. [1], outlining pathways for an energy and sustainable transition requires knowledge of advanced technologies across several areas, including the conversion of waste into energetic materials. The amount of waste generated is on the rise, increasing as urbanization and economic development grow. Of the approximately 2.01 billion tonnes of municipal solid waste (MSW) produced annually, about 33% is inadequately managed from an environmental standpoint. Improper management of MSW leads to environmental, socioeconomic, and public health problems, revealing an urgent need to find strategies to reduce the enormous volumes of waste [2,3].

Strategies such as recycling, direct incineration with energy recovery, and landfill disposal have been widely applied by waste management entities and energy companies; however, they face significant obstacles and disadvantages. Not all types of waste are recyclable, and there are limits to the number of times a material can be recycled. Moreover, recycling is minimally applied in countries where large volumes of waste are sent to landfills. Landfill disposal leads to the loss of carbon-based resources that could otherwise be valorized. Incineration, widely used in Western, Central, and Northern Europe is energetically inefficient, producing mainly heat and electricity while generating greenhouse gases (GHG) and toxic emissions that require costly treatment. Its resulting solid residues also require further handling, highlighting the need for more efficient and circular waste-to-energy (WtE) approaches [3,4,5].

Waste such as MSW can be processed into refuse-derived fuel (RDF), the combustible fraction produced through mechanical–biological treatment (MBT) and subsequently transformed into char for use as an energy resource or multifunctional material. This strategy, known as thermal or chemical recycling, involves exposing carbon-containing waste, such as polymeric fractions and carbon-rich fibrous materials, to elevated temperatures to produce a new, more uniform product. Resource recovery reduces the demand for virgin raw materials, cuts GHG emissions, and minimizes the quantity of discarded waste [3,4].

According to Khan et al. [3], one of the main present and future concerns is the continuous increase in both the volume and complexity of MSW. Its heterogeneous composition constitutes a major obstacle to efficient valorization. Thermal and chemical recycling, particularly pyrolytic conversion to char, addresses this challenge by yielding a uniform, homogeneous material with favorable chemical and structural properties suitable for applications such as energy generation, catalysis, adsorption, and soil amendment [6,7]. Several thermochemical routes produce char, including torrefaction, carbonization (slow pyrolysis), intermediate pyrolysis, and gasification. These processes can be carried out in dry conditions or hydrothermally (in a liquid medium such as water) [6]. For high-moisture wastes, hydrothermal processes are advantageous, whereas for heterogeneous materials such as RDF and lignocellulosic residues with lower water content, dry thermochemical routes are more suitable [8].

Life cycle assessment (LCA) studies indicate that pyrolysis and gasification are among the most sustainable options for MSW valorization when compared with landfilling, incineration, or anaerobic digestion [9]. Pyrolysis is conducted in the absence of oxygen and predominantly yields char at temperatures below 500 °C (slow pyrolysis). At higher temperatures (500–550 °C), bio-oil becomes the main product, while above 700 °C, gas production is favored [10]. The benefits of this process include an increase in heating value, improved hydrophobic behavior, enhanced grindability, reduced oxygen and hydrogen carbon ratio (O/C and H/C ratios), and a low moisture content in the resulting char [11].

Char offers a higher high heating value (HHV) and energy density, along with a lower moisture content, making it more homogeneous and stable than raw residue. It also minimizes the risk of incrustation and clogging and simplifies grinding and handling due to its friability. Practically, these benefits lead to reduced logistics costs, including transportation and storage, enhanced system performance stability, and facilitated integration of these chars into existing systems, thereby boosting the reliability of WtE or Waste to Gas (WtG) systems [12,13].

Several studies have demonstrated the potential of slow pyrolysis to recover valuable char from heterogeneous solid wastes. RDF-derived chars produced at 400–500 °C are rich in micronutrients (K, Mg, P), contain functional groups such as –OH and –COOH, and display alkaline pH values (7.8–9.5), making them promising soil conditioners [9]. Improved homogeneity, grindability, and heating value were also observed in RDF chars produced at 250–350 °C, which showed an increase in HHV of approximately 36% comparing to the raw RDF [8]. Other studies have reported optimal HHV and reduced ash content at around 400 °C, while higher temperatures decrease volatiles and increase ash content [14]. Conversely, pyrolysis at higher temperatures (up to 900 °C) can enhance surface area and adsorption capacity, as shown by Miskolczi et al. [15], suggesting that temperature should be selected based on the intended application. A higher pyrolysis temperature, however, demands more energy, reinforcing the need to optimize the process to balance char quality with operational costs and environmental performance. Thus, temperatures above 400 °C may be advantageous for specialized applications such as adsorbents or catalysts. In contrast, moderate temperatures are more suitable for fuel applications or bulk material uses where energy efficiency is critical [16,17].

Despite the growing number of studies on RDF pyrolysis, limited research has investigated the combined valorization of RDF pellets blended with biomass residues, particularly regarding how these blends affect char physicochemical properties and ash-related behavior under slow pyrolysis conditions. Few studies have systematically evaluated chars produced from RDF–biomass pellets under identical carbonization conditions, while simultaneously linking their combustion behavior and ash-related indices. Biomass–RDF blends may offer synergistic advantages, such as improved pelletization, reduced chlorine content, and more controlled ash chemistry, yet these interactions remain insufficiently characterized [18,19,20].

Understanding the properties of ash, slag behavior, and viscosity is crucial for optimizing the performance of pyrolysis, combustion, and gasification systems. The accumulation of molten ash on the internal surfaces of furnaces, gasifiers, or boilers can compromise heat transfer, reduce efficiency, hinder the combustion or gasification of the remaining carbon, and even lead to corrosion and mechanical failures [21]. Therefore, this study aims to characterize chars obtained from slow pyrolysis (400 °C) of RDF–biomass pellets prepared in different proportions, evaluating their mass and energy yields, physicochemical properties, combustion behavior, and ash-related indices. By directly linking combustion characteristics with ash melting, slagging, and incrustation tendencies, this work provides an integrated assessment of the suitability of RDF–biomass chars for stable and efficient conversion systems, contributing to the development of sustainable and circular WtE systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Feedstock

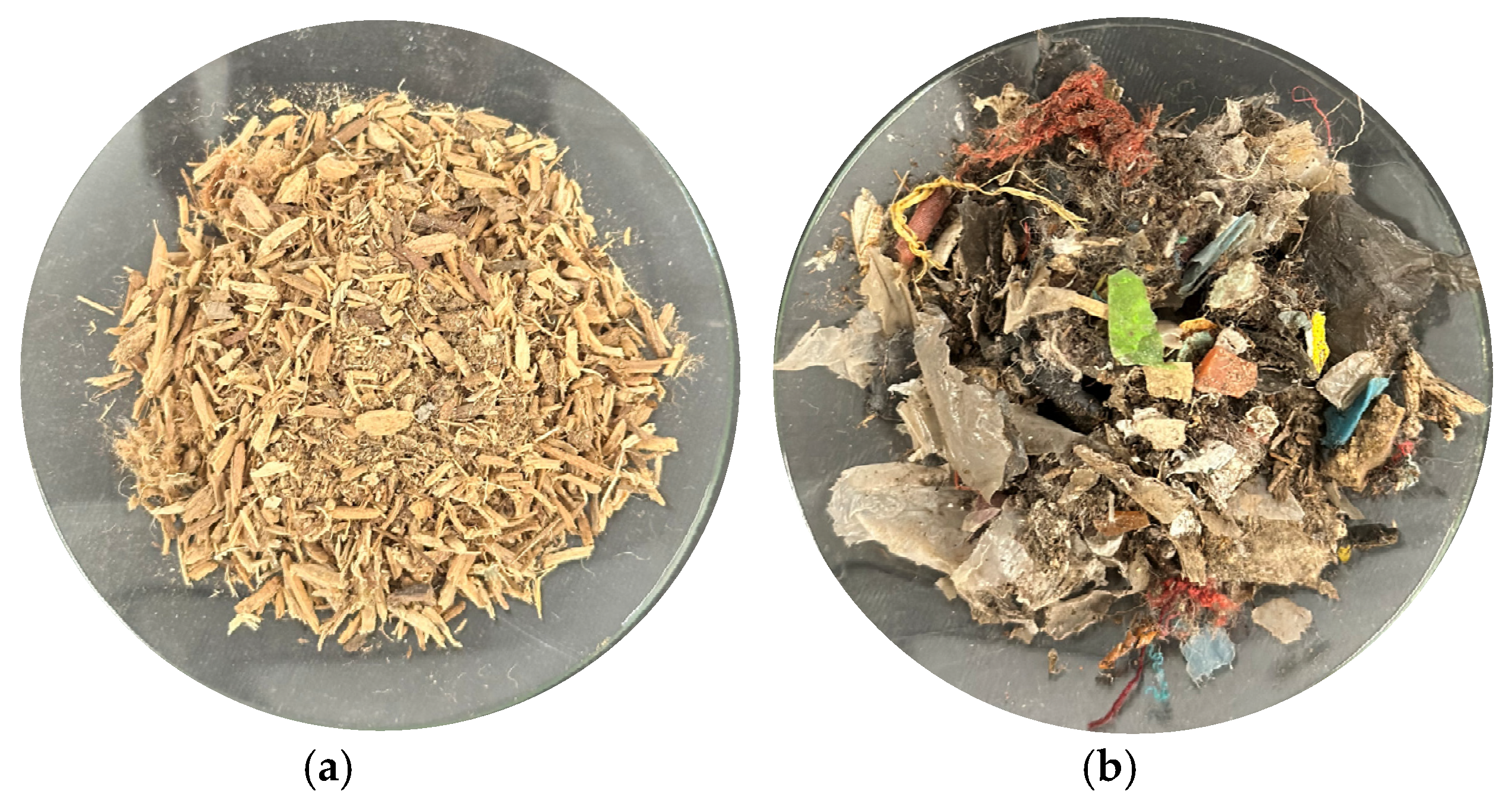

The biomass waste sample (Figure 1a) was obtained pre-shredded from the company Casal & Carreira Biomassa S.A. (Leiria, Portugal), and consisted of an end-of-life lignocellulosic biomass stream. This stream corresponds to low-grade, heterogeneous lignocellulosic residues handled within biomass supply chains (e.g., mixed wood-derived residues from the forestry industry routed to biomass valorization, including pellet production), supplied as a pre-processed (shredded) material.

Figure 1.

Raw materials as received. (a) biomass waste; (b) RDF.

The RDF sample (Figure 1b) was supplied by a MSW company, BRAVAL S.A. (Braga, Portugal). For sampling purposes, eight different sampling points were selected, and eight samples of 4 kg each were collected and homogenized to obtain a composite sample. From this composite, three subsamples of 100 g each were collected and manually sorted to determine their morphological composition. The RDF contained 32.09 ± 0.25% plastics, 16.26 ± 1.68% textiles, 11.15 ± 1.09% paper and cardboard, with the remaining fraction consisting of unidentified materials. The characterizations of the original raw materials (RDF and BW) were detailed in a previous study [22]. The raw BW presented an ash content of 4.2 ± 0.4% (dry basis). This value is lower than the ash content measured in the corresponding pellets. The increase observed after pelletization is attributed to the concentration of fine mineral-rich fractions within the processed material. In addition to its low ash content, the raw BW exhibited typical lignocellulosic characteristics, including low sulfur content and moderate carbon content, consistent with mixed wood-derived residues, as detailed in [22].

The RDF was shredded using a hammer mill equipped with 10 mm and 2 mm screens and subsequently pelletized (Andritz, Germany) using a 6 mm die. Mixtures of RDF and biomass residues at different proportions were also pelletized under the same conditions (Figure 2). For clarity, the produced pellets were coded according to the proportion of RDF and biomass wastes (BW) in each formulation: RDF100 corresponds to pellets composed of 100% RDF; RDF50:BW50 to pellets containing 50% RDF and 50% biomass wastes; RDF25:BW75 to pellets with 25% RDF and 75% biomass wastes; RDF15:BW85 to pellets with 15% RDF and 85% biomass wastes; and BW100 to pellets composed entirely of biomass wastes.

Figure 2.

Pellets produced as a raw material for the slow pyrolysis process.

A summary of the main physicochemical properties of the pellets, previously reported in earlier work, is provided here for completeness. Moisture content ranged from 5.4 to 10.1 wt.%, ar, while volatile matter varied between 67.9 and 79.9 wt.%, db. Fixed carbon values were between 0.94 and 14.4 wt.%, db, and ash content ranged from 12.4 to 19.1 wt.%, db. Chlorine content spanned 1.34 to 3.36 wt.%, ar. Elemental analysis showed carbon contents between 49.8 and 58.1 wt.%, daf, hydrogen between 6.2 and 7.9 wt.%, daf, nitrogen between 1.1 and 1.2 wt.%, daf, sulfur between 0.2 and 0.4 wt.%, daf, and oxygen between 32.4 and 42.6 wt.%, daf. These values reflect the compositional variability of RDF and biomass waste and provide the baseline for evaluating the changes induced by pyrolysis.

2.2. Biochar Production

Operating parameters such as temperature and residence time have a strong influence on char yield and on the properties of the resulting material. Because the RDF pellets contain a high fraction of plastics, the selection of pyrolysis time and temperature is particularly critical to ensure efficient degradation of the polymeric components [20]. The main RDF polymeric fractions thermally degrade predominantly within the 350–500 °C range, while lignocellulosic components decompose between 250 and 400 °C [23,24]. Although higher temperatures may promote more extensive polymer cracking, they also reduce char yield and increase ash concentration. Therefore, 400 °C was selected as a compromise temperature to ensure substantial degradation of both plastic and biomass fractions while preserving fixed carbon and energy yield, in line with previous RDF carbonization studies [14,25,26].

The slow pyrolysis tests conducted in this study were based on the procedures described by Longo et al. [7] and Nobre et al. [27]. The chars were produced at 400 °C for 1 h in a muffle furnace (Kilper®, CK 25-E, CERINNOV, Leiria, Portugal) with an effective capacity of 80 L. The selected residence time refers to the duration at the target temperature after thermal stabilization. At 400 °C, primary devolatilization of lignocellulosic components and degradation of the main RDF polymeric fractions occur rapidly once isothermal conditions are reached [10,14]. Considering the small batch size (30 g), the pre-heated furnace configuration, and the use of closed crucibles, 1 h was deemed sufficient to ensure uniform carbonization without unnecessarily extending thermal exposure.

Before each experiment, the furnace temperature stabilized at 400 °C, and the empty crucibles and their corresponding lids were preheated at the operating temperature, then transferred to a desiccator to cool to room temperature before being weighed. For each run, approximately 30 g of pellets were placed into the crucibles, which were then covered with their lids. The crucibles were introduced into the furnace and maintained at 400 °C for 1 h. After the residence time, they were removed, cooled in a desiccator to room temperature, and weighed again. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The resulting chars were coded according to the composition of the corresponding pellets: C_RDF100, C_RDF50:BW50, C_RDF25:BW75, C_RDF15:BW85, and C_BW100, reflecting formulations containing 100%, 50%, 25%, 15%, and 0% RDF, respectively.

All samples were characterized in the as-produced state (no washing or leaching or other dechlorination step was applied). Chlorine was therefore treated as an intrinsic property of the RDF-derived chars and was quantified by XRF (Section 3.2.1, Table 1) to support interpretation of downstream characterization results.

Table 1.

Summary of the results of the physicochemical characterization of the produced chars.

2.3. Process Performance Assessment

The performance of the slow pyrolysis process for char production was evaluated by calculating the mass yield (Ymass) and energy yield (Yenergy) using Equations (1) and (2):

where and represent the mass (kg) and higher heating value (MJ/kg) of the produced char, and and correspond to the mass (kg) and higher heating value (MJ/kg) of the raw pellets.

2.4. Char Characterization

2.4.1. Chemical Characterization

HHV was determined on a dry basis (db) using an IKAC®200 bomb calorimeter (Staufen, Germany). The contents of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), nitrogen (N), and sulfur (S) were measured using an elemental analyzer (Thermo Finnigan–CE Instruments, Flash EA 112 CHNS series, Milan, Italy). Oxygen content was calculated by difference on a dry, ash-free basis (daf). The proximate composition of the chars was determined according to ASTM standards: ASTM E949-88 [28] for moisture (fractions < 0.425 mm), ASTM E897-88 [29] for volatile matter, and ASTM E830-87 [30] for ash. Fixed carbon was calculated by difference (db).

2.4.2. Functional Group Analysis

FT–IR spectra were obtained using a Nicolet iS10 Fourier–transform infrared spectrometer (SID–Molecular, Wisconsin, USA) to identify surface functional groups. Spectra were recorded in the range of 400–4000 cm−1, using 32 scans and a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1.

2.4.3. Thermal Decomposition and Combustion Behavior

Thermogravimetric analysis was performed using a TGA 8000™ analyzer equipped with an autosampler, under an oxygen flow of 20 mL/min. The tests were conducted in ceramic crucibles using approximately 10 mg of sample, over a temperature range of 30 to 900 °C, with a heating rate of 20 °C/min. Thermogravimetric (TG) and derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) data were processed to extract three characteristic combustion parameters: the ignition temperature (Ti), the temperature of maximum mass-loss rate (Tmax), and the burnout temperature (Tf). The initial mass (m0) and residual mass (m∞) were taken from the first and last points of the TG curve, and the fractional conversion was computed as described in Equation (3), following standard TG kinetic conventions [31]:

Tmax was defined as the temperature corresponding to the maximum |DTG| value, a commonly used indicator of peak reactivity in solid fuel combustion [32]. Ignition temperature (Ti) was determined using a DTG-threshold method, where Ti is the first temperature ≥ 150 °C at which |DTG| reaches 5% of its maximum, consistent with approaches applied in solid fuels and biofuels combustion analyses [32,33]. Burnout temperature (Tf) was identified as the point at which the TG curve satisfied , reflecting near-complete oxidation of the remaining char [34,35]. Together, these parameters provide a concise comparative measure of ignition behavior, peak combustion reactivity, and burnout characteristics among the samples. Ignition (Di) and flammability (C) indices were calculated to provide a quantitative assessment of overall combustion performance. Di was calculated as the ratio between the maximum mass-loss rate and the product of ignition and burnout temperatures, as seen in Equation (4):

While C was calculated as the ratio between the maximum mass-loss rate and the square of the ignition temperature, represented in Equation (5):

These indices are commonly used in TG-based combustion studies to evaluate the ease of ignition and the intensity of early-stage combustion, allowing direct comparison of fuels with different compositions. All TG/DTG experiments were performed in replicate runs to confirm reproducibility. However, the reported combustion parameters (Table 2) were extracted from representative profiles, and standard deviations are not reported, as these curve-derived indicators are not treated as statistical variables.

Table 2.

Characteristic combustion parameters derived from TG/DTG analysis for RDF, biomass, and blended samples.

2.4.4. Ash Behavior and Fouling/Slagging Potential

The inorganic composition of the chars was determined by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP–AES) after sample digestion, and chlorine content was measured using X–ray fluorescence (XRF, Niton XL3t Analyzer, MA, USA). The mineral fraction was converted into its corresponding oxide forms to support the evaluation of slagging and fouling tendencies. The potential for char ash deposition and fouling was assessed using several empirical indices, including: The base-to-acid ratio (B/A) was calculated using Equation (6) to evaluate the tendency for slag formation inside the furnace, the slag viscosity index (Sr) was determined using Equation (7), and the fouling index (Fu) was obtained through Equation (8) to assess fouling potential. The amount of alkali oxides in char per unit of energy (kg of alkali/GJ) was also calculated using Equation (9). Additionally, the likelihood of bed agglomeration was evaluated through the bed agglomeration index (BAI), calculated according to Equation (10).

According to Lachman et al. [36], ash exhibits a low tendency for slag formation when the B/A value is below 0.5, and a moderate tendency is observed between 0.5 and 1.0. The tendency becomes high between 1.0 and 1.75, and values above 1.75 indicate a strong propensity for slagging. The slag viscosity index is a useful measure for determining how easily slag may form in the furnace. Higher values reflect more viscous ash and therefore less slagging. Generally, slagging is low for Sr above 72, moderate between 65 and 72, and high when it falls below 65. The alkali index quantifies the amount of alkali oxides per unit fuel energy. When this index exceeds 0.17 kg of alkali/GJ, scale formation becomes likely, and once it surpasses 0.34 kg of alkali/GJ, it becomes almost inevitable. For fouling, Fu values below 0.6 correspond to low fouling potential, values up to 40 indicate high potential, and values exceeding 40 represent extreme fouling risk. Bed agglomeration is likely to occur when the BAI value is below 0.15.

3. Results

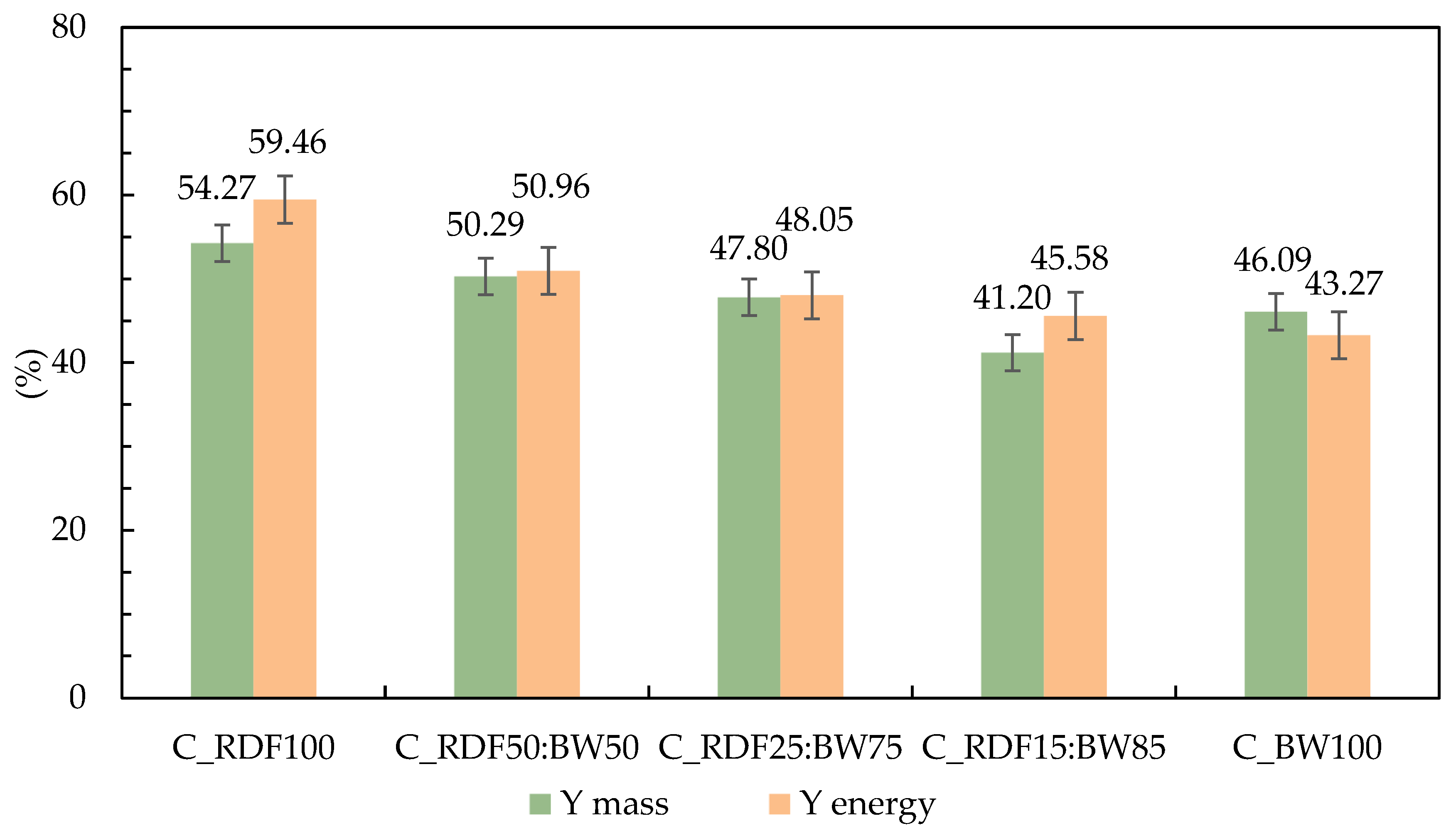

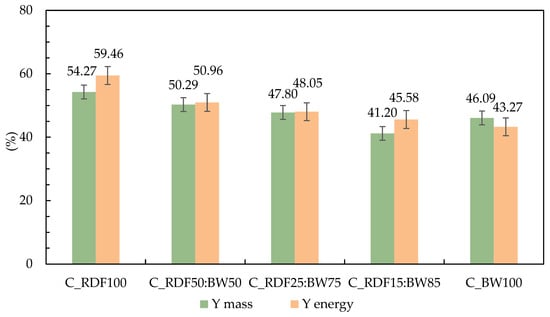

3.1. Process Performance Assessment

The mass and energy yields of the chars produced by slow pyrolysis of the pellets are presented in Figure 3. The results show a clear trend associated with the proportion of RDF and BW in the mixtures. Both mass and energy yields decrease progressively as the RDF fraction is reduced. Sample C_BW100 is unique in that its mass yield surpasses its energy yield, indicating a greater concentration of low-heating-value volatiles and inert materials, such as ash [37]. The C_RDF100 sample exhibits the highest yields, confirming better performance when the feedstock consists solely of RDF. In the blended samples, a gradual reduction is observed, with C_RDF15:BW85 showing the lowest values.

Figure 3.

Mass and energy yield of chars produced through pyrolysis at 400 °C.

The thermal decomposition of the plastic fraction present in RDF can influence char formation through interactions with the lignocellulosic matrix during co-pyrolysis. As plastics thermally soften or partially melt within the 350–450 °C range, they may physically interact with biomass particles, limiting volatile release and promoting secondary reactions at the solid phase. Simultaneously, biomass-derived char can act as a reactive matrix capable of retaining or cracking volatile compounds released from the plastic fraction, contributing to additional solid carbon formation. These synergistic interactions may enhance char stabilization by reducing excessive devolatilization and favoring crosslinking reactions within the solid residue. Depending on blend composition, such effects can contribute to higher char yields and improved structural stability compared to single-component pyrolysis, as reported in previous co-pyrolysis studies [38,39]. The present results are consistent with these mechanisms, supporting the role of RDF–biomass interactions in governing char yield and properties.

Although C_BW100 shows a slight recovery in mass yield, its energy yield remained comparatively lower. Similar trends were reported by Longo et al. [40], who found that the char mass yield from RDF pellets decreased as the proportion of biomass in the mixture increased.

The RDF used in this study presented a lower moisture content and higher C and H contents, characteristics that favor fixed carbon retention and good energy density after pyrolysis, resulting in chars with higher mass and energy yields. In all cases, the energy yield remained higher than the mass yield, indicating effective retention of energetic potential despite the loss of mass during thermal conversion.

3.2. Char Characterization

3.2.1. Chemical Characterization

Table 1 presents the physicochemical composition of the chars produced by slow pyrolysis of RDF and biomass waste pellets. Lower moisture and oxygen contents, together with higher volatile matter, carbon, and hydrogen contents, were observed in chars with higher proportions of RDF, most likely due to the presence of plastic materials in the RDF. Chen et al. [41] reported a similar trend in their study: as the proportion of plastics (polyethylene) increased during co-pyrolysis with bamboo, the resulting chars exhibited higher carbon and hydrogen contents and lower oxygen content. According to the authors, during pyrolysis, volatiles released from plastics may condense onto the char surface, enriching it in carbon and hydrogen while promoting deoxygenation reactions that reduce the oxygen content. In this context, the plastic fraction present in the RDF represents a particularly concentrated source of carbon and hydrogen, reinforcing the decisive role of these materials in increasing the carbon and hydrogen contents of the resulting chars [42]. This also resulted in higher energy content of the char with the incorporation of RDF, from about 15 MJ/kg to 23 MJ/kg on a dry basis.

Regarding volatile matter, a high content indicates a greater potential to produce pyrolysis gas and syngas, in addition to facilitating ignition and improving the efficiency of thermochemical processes [43]. As noted by Magdziarz et al. [19], higher volatile matter content generally leads to increased yields of gaseous products. This is because these components break down when heated, releasing gases such as methane, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen. Ash content was high in all chars, likely due to the concentration of minerals during pyrolysis, the heterogeneity and impurities present in the RDF, additives contained in plastics, and the inherent mineral fraction of the biomass. The ash fraction in solid fuels can lead to slagging, fouling, bed agglomeration, and corrosion issues during thermal conversion. For this reason, the inorganic composition of the chars and their tendencies toward slag formation, fouling, and agglomeration are analyzed in a later section.

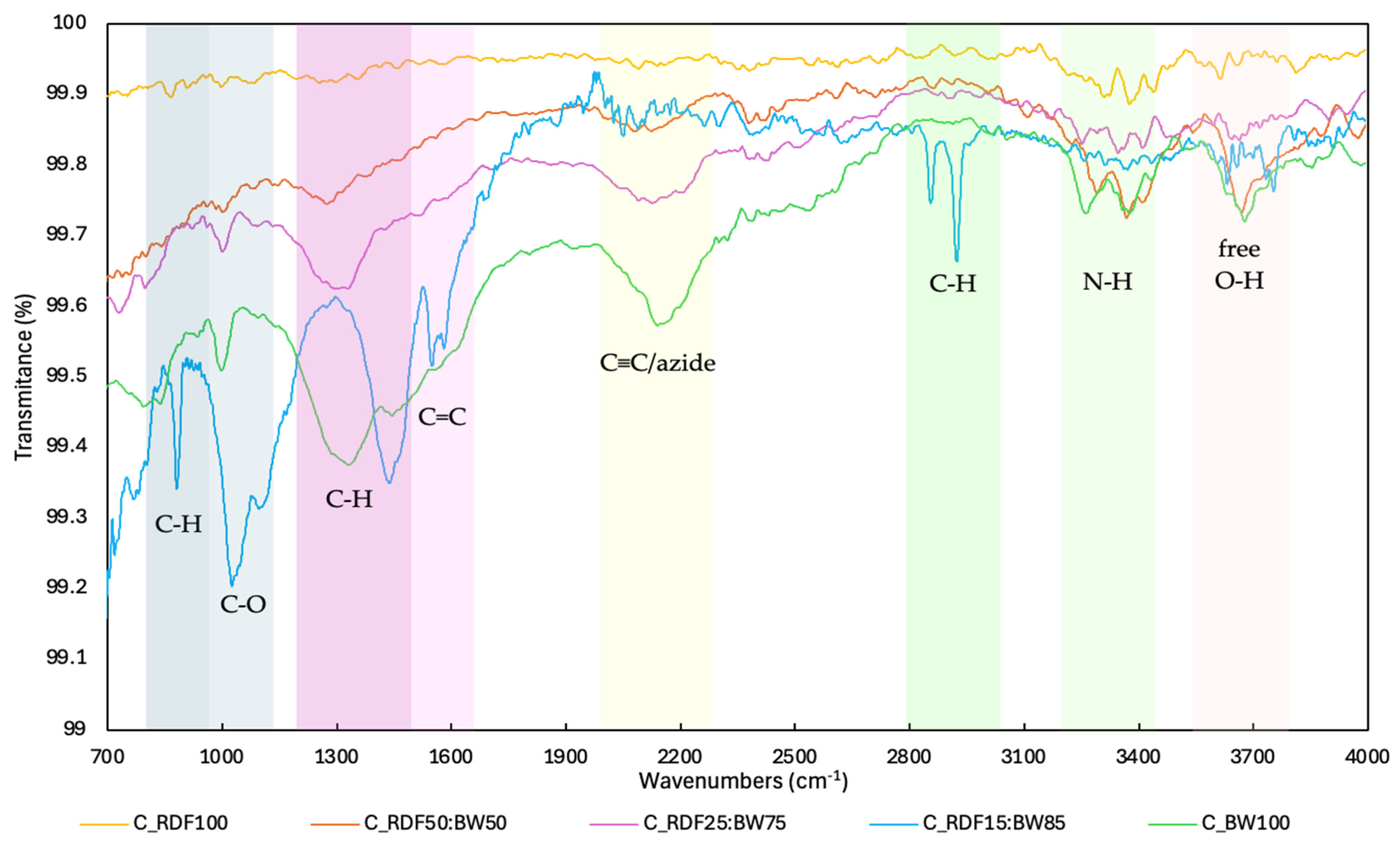

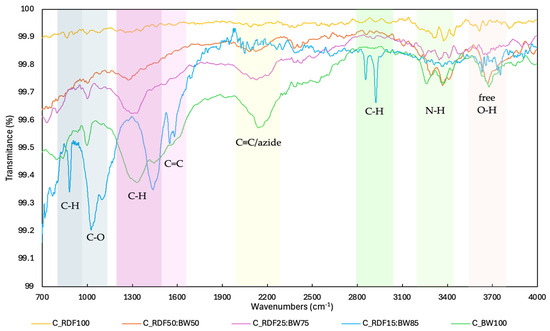

3.2.2. FT–IR Analysis

Figure 4 shows the FT–IR spectra of the chars produced. This analysis was used to observe how the molecular chemistry of char changed as the proportion of RDF in the mixtures increased.

Figure 4.

FT–IR spectra of chars.

The FT–IR spectrum displays the characteristic bands of biomass-derived chars, including the out-of-plane C–H modes in aromatic rings (800–900 cm−1), the adjacent signal linked to C–O bonds (900–1200 cm−1), the combined C–O/C–H modes around ≈1300 cm−1, and the CH2/CH3 bending vibrations (1360–1480 cm−1). It also shows bands attributed to aromatic C=C stretching (1500–1600 cm−1), C≡C absorption band (2100–2200 cm−1), aliphatic and aromatic C–H stretching (2860 and 3020 cm−1), typical N–H stretching of primary amines (3200–3400 cm−1) and free O–H groups (3650–3700 cm−1) [14,44,45,46]. Generally, chars with a higher fraction of biomass residues (C_BW100, C_RDF15:BW85, and C_RDF25:BW75) exhibited more pronounced bands associated with oxygenated functional groups. For instance, these chars feature a broad band around ≈1000 cm−1, attributable to C–O stretches (alcohols, ethers, phenols, esters), and deformations characteristic of oxygenated groups present in biomass, as well as ≈3300 cm−1, characteristic of O–H stretching (alcohols, carboxylic acids, hydroxyl ligands, and water). This pattern aligns with the presence of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin in the biomass, which intensifies the O–H and C–O signals in the spectra. The study by Magdziarz et al. [19] observed that as the proportion of RDF increased in mixtures of biomass (comprising rye straw and agricultural grass) and RDF, there was a corresponding decrease in the concentration of oxygenated compounds. Increasing the RDF fraction reduced the intensity of the oxygenated bands, consistent with the elemental analysis results of the chars and the anticipated changes in the physicochemical properties of chars with a higher RDF proportion (lower oxygen content and higher hydrophobicity), which may affect their reactivity and volatilization characteristics [19,47,48]. The spectra of chars with a higher RDF proportion were nearly flat, indicating less diversity in the functional groups on the surface, greater thermal stability, and a high degree of aromatization of the char. The literature indicates that as thermal conversion of plastics advances, the liquid aromaticity of the carbon matrix increases. This increase results from the preferential removal of thermally less stable aliphatic structures [49]. Biomass-rich mixtures retain oxygenated functionalities, whereas higher RDF contents result in more aromatic and structurally uniform char. This evolution is consistent with the decrease in the oxygen content and greater thermal stability of chars with a higher RDF proportion, reflecting the transition to a more condensed carbon matrix.

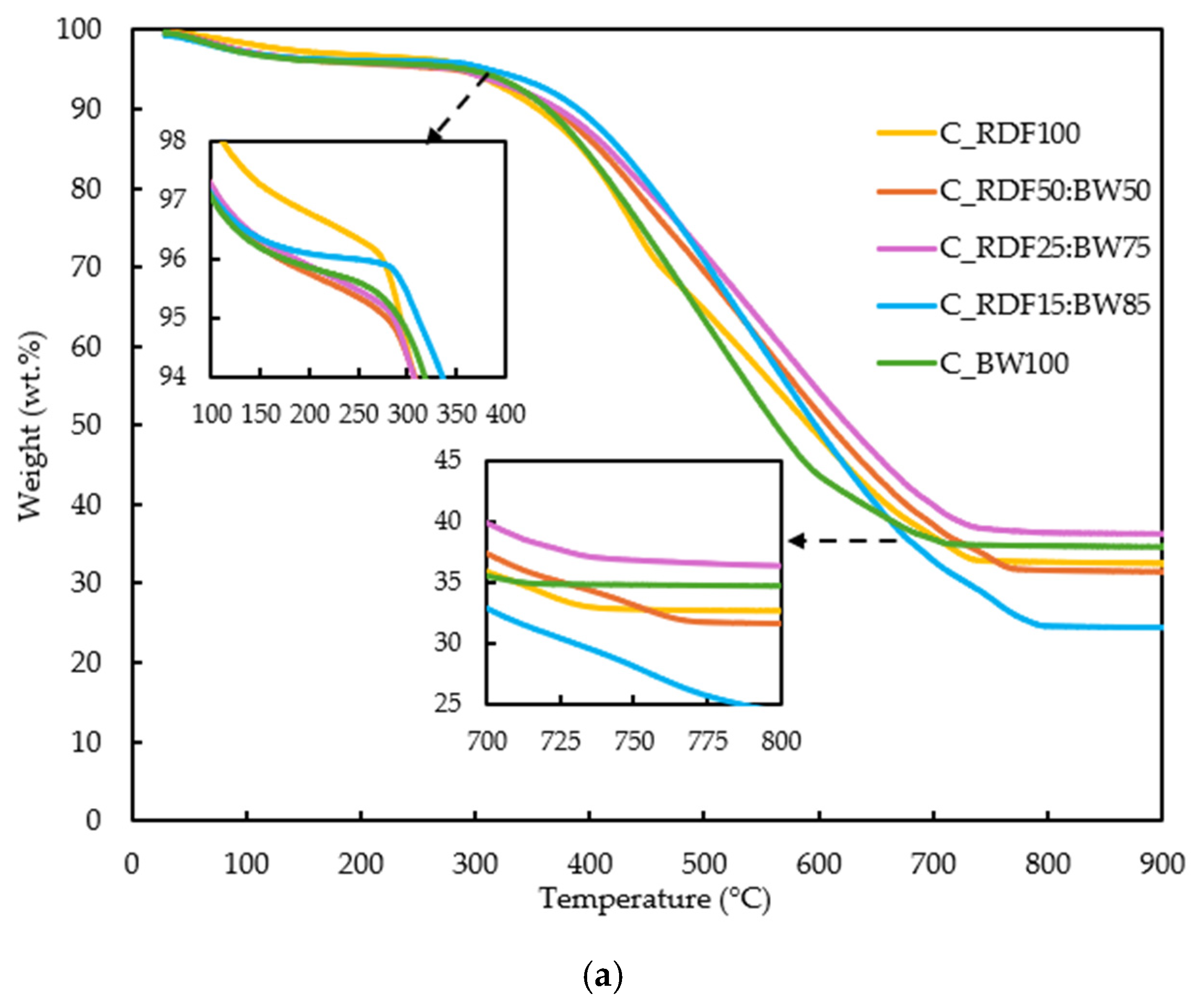

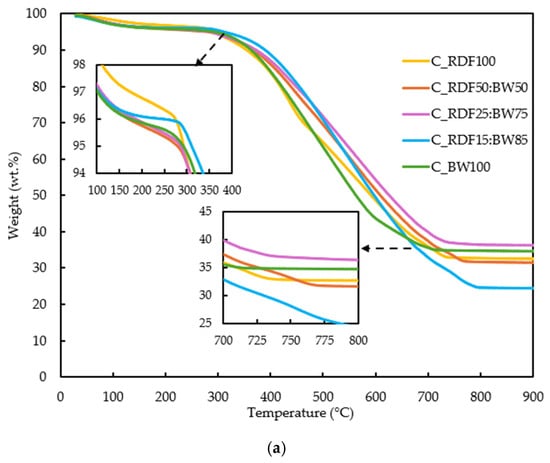

3.2.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis

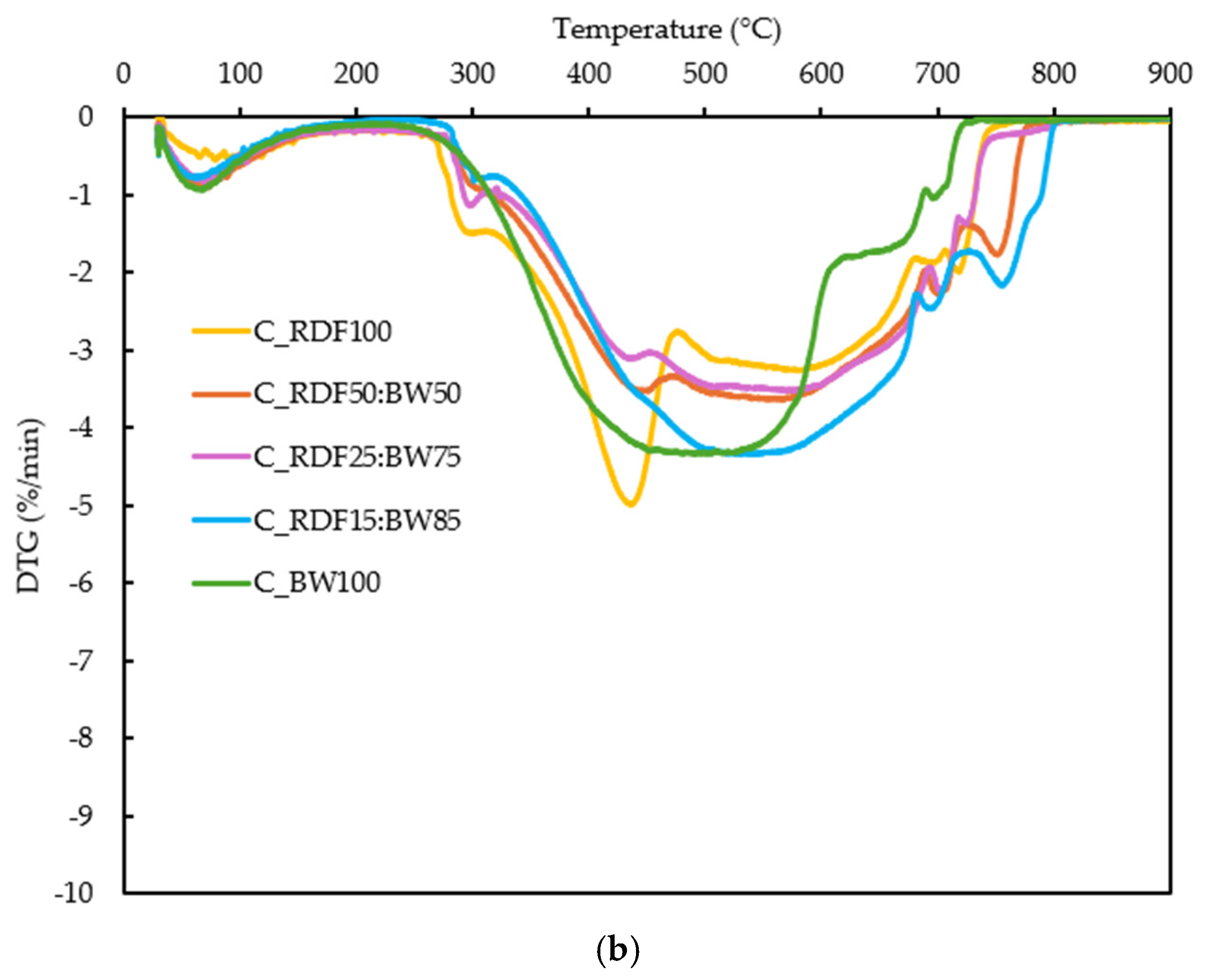

The thermal conversion behavior of the samples was evaluated through their TG and DTG profiles (Figure 5a,b). These analyses provide quantitative indicators of ignition behavior, reactivity, and burnout, which are later discussed in relation to char composition and ash-related properties to support an integrated performance assessment.

Figure 5.

(a) TG curves of the RDF, biomass, and blended samples; (b) DTG curves of the RDF, biomass, and blended samples.

The TG curves in Figure 5a reveal broadly similar thermal decomposition profiles for all samples, though with clear differences in both the onset and extent of mass loss. All fuels exhibit an initial minor decrease in mass below 150 °C, associated with moisture release. The major devolatilization stage occurs between approximately 250 and 800 °C, which corresponds to the degradation of lignocellulosic, which has a wider decomposition temperature range, and polymeric chains present in chars. Although aromatization generally increases the stability of RDF char, a noticeable reactive fraction persists. This residual reactivity is associated with the presence of plastics and with functional groups such as hydroxyls, which contribute to the marked decomposition observed around 430–450 °C. In fact, sample C_RDF100 was the only one to display a pronounced peak in this temperature range, indicating that unconverted polymer fractions remaining after pyrolysis were largely responsible for the mass loss, as also reported by Alves et al. [8] and Bhatt et al. [9].

Pure RDF (C_RDF100) and biomass (C_BW100) display smoother and more gradual mass loss within 250 and 800 °C. At temperatures exceeding 600 °C, the curves diverge more distinctly: C_RDF15:BW85 attains lower final residual masses, aligning with its reduced inorganic fraction and carbon content, as well as its increased oxygen content, as confirmed by chemical characterization.

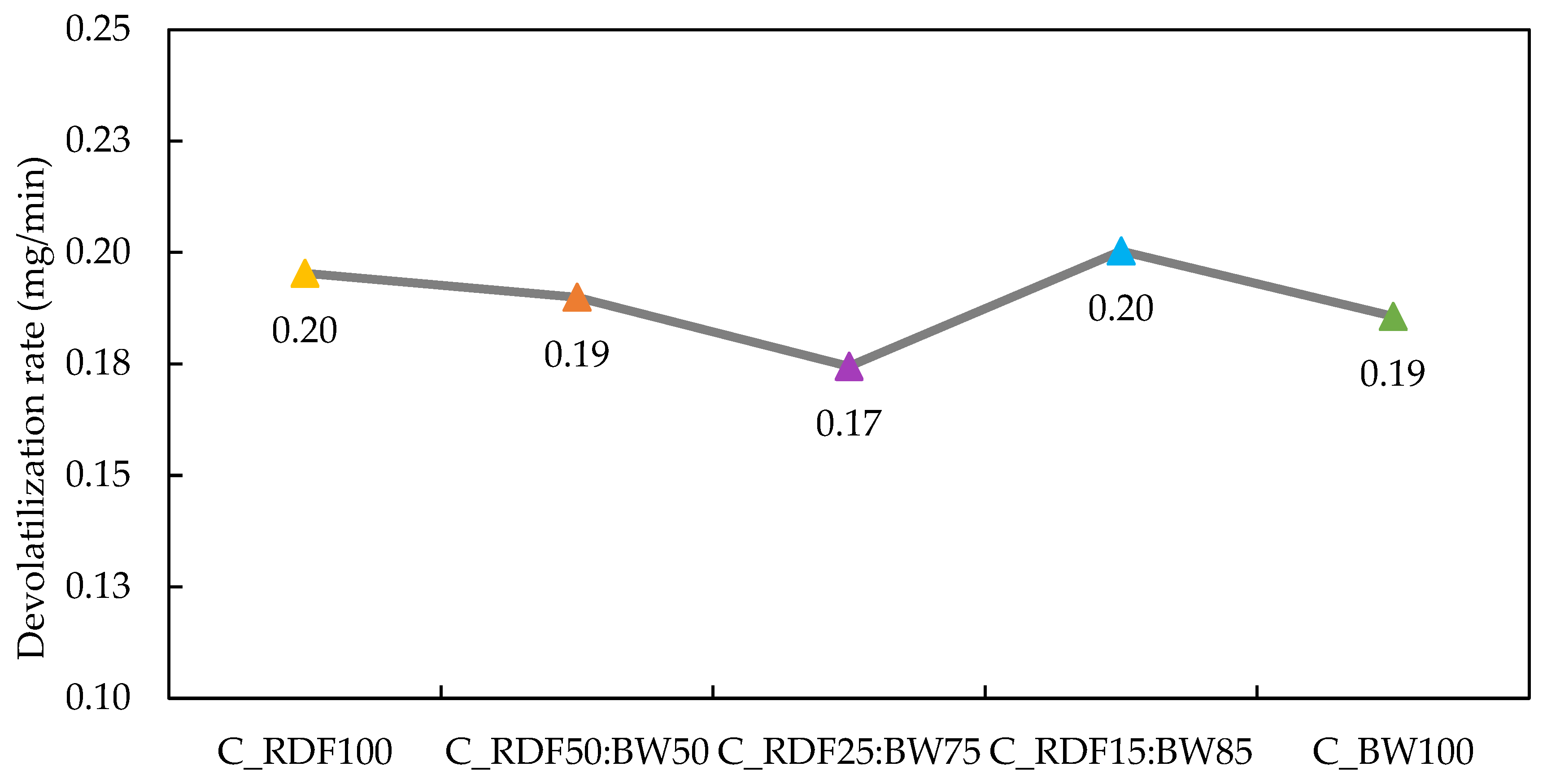

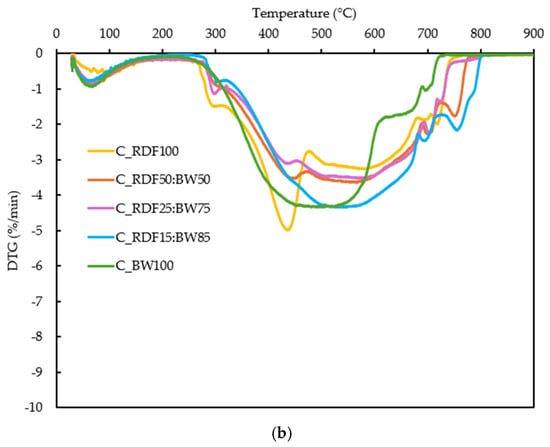

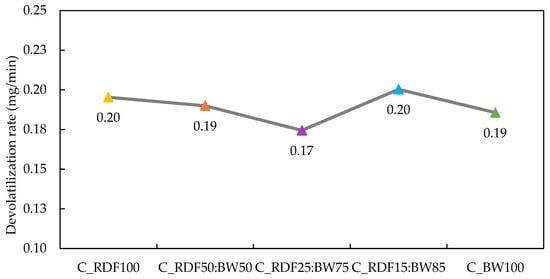

The devolatilization rate of the chars is depicted in Figure 6. It is important to note that devolatilization is sensitive to char composition, exhibiting nonlinear behavior (0.17 to 0.20 mg/min). This non-linearity suggests that the devolatilization rate is influenced not only by the individual proportions of the components but also by the synergistic effects of physicochemical interactions between RDF and BW. In the case of C_RDF100, the elevated devolatilization rate (≈0.20 mg/min) indicates high thermal reactivity, potentially associated with the higher fraction of polymeric materials, the substantial volatile matter content (42.7 wt.% db), and the low fixed carbon (19.79 wt.% db) of this char. As the biomass fraction increases, there is a progressive reduction in volatile matter and an increase in fixed carbon, particularly evident in C_RDF25:BW75 and C_RDF15:BW85. In C_RDF25:BW75, the combination of low volatile content (31.08 wt.% db) and high fixed carbon (33.35 wt.% db) results in a more stable and less reactive structure, justifying the lower devolatilization rate (≈0.17 mg/min) observed. Generally, materials with low volatility and a high concentration of fixed carbon tend to be more resistant and stable [50]. These trends highlight how blend composition governs both reactivity and structural stability of the resulting chars. Studies indicate that, in certain mixing proportions, during the pyrolysis of biomass with plastic material, the presence of lignocellulosic material contributes to greater stability of the residual char, an effect attributed to diffusion restrictions that reduce the volatilization of intermediate compounds [51]. The resistance of char to degradation depends, above all, on how its carbon atoms are organized and connected internally [50].

Figure 6.

Devolatilization rate of chars.

The spectrum of C_RDF15:BW85 char shows aromatic, C=C, and C–H functional groups (Figure 4), reflecting a more aromatically condensed and less functionalized char, which enhances its thermal stability. In C_RDF15:BW85, the devolatilization rate reached 0.20 mg/min, which contradicts the expected trend of increased fixed carbon and decreased volatile matter. The substantial proportion of biomass within this mixture is likely to facilitate the release of volatile compounds due to its catalytic effect [52]. This deviation from linear compositional trends underscores the complexity of RDF–biomass thermal interactions and motivates the combined evaluation of thermal reactivity and ash-related behavior. Future studies on char degradation, together with analysis of released gases, are necessary to provide more information on the synergistic effects of RDF co-pyrolysis chars with biomass waste.

The DTG curves in Figure 5b provide deeper insight into reactivity and decomposition stages. A primary DTG peak is observed for all fuels, corresponding to rapid devolatilization. Its position and intensity vary systematically with blend composition: the peak appears at lower temperatures for C_RDF100 and C_BW100, whereas intermediate blends (C_RDF50:BW50 and C_RDF25:BW75) exhibit peaks shifted to higher temperatures (≈560–575 °C), consistent with a more distributed combustion process. The peak magnitude (DTGmax) is highest for C_RDF100 (Table 2). A secondary DTG feature is present at elevated temperatures (>650 °C), particularly in biomass-containing samples, reflecting char oxidation. The broader and more extended DTG signals of biomass-rich samples indicate slower late-stage oxidation, in agreement with their higher burnout temperatures (Tf) reported in Table 2.

The characteristic combustion parameters extracted from these curves, namely the ignition temperature (Ti), peak reactivity temperature (Tmax), burnout temperature (Tf), and the ignition (Di) and flammability (C) indices, are summarized in Table 2. Together, these parameters enable direct comparison of ignition, reactivity distribution, and burnout behavior across the different RDF–biomass char compositions.

Biomass addition markedly lowers Ti for the mid-range blends (C_RDF50:BW50 and C_RDF25:BW75), confirming a strong ignition-promoting effect, while high RDF or high BW fractions exhibit higher Ti values. The highest Tmax values appear in the intermediate blends, indicating more distributed combustion, whereas pure RDF and pure biomass burn more sharply. Tf increases with biomass fraction, suggesting slower conversion of biomass-derived char. The Ti verified here for C_RDF100 (264 °C) is close to the values reported by Longo et al. [40] and Guo et al. [53], which are 283 °C and 332 °C, respectively. The Di and C indices confirmed that, while all samples demonstrated relatively low thermal reactivity, C_RDF100 was somewhat more prone to mass loss, whereas C_RDF50:BW50 displayed greater overall stability. Biomass-rich mixtures have lower C values among the chars, suggesting slightly diminished overall thermal stability.

The TG/DTG results show that the composition clearly influences the thermal behavior of the chars. C_RDF100 shows a marked peak at 435 °C (DTGmax = 4.99%/min), associated with residual polymers, whereas the mixtures shift Tmax to 566–575 °C, revealing a more distributed conversion. Biomass reduced Ti to approximately 150 °C and prolonged the final oxidation, with Tf reaching 766 °C in C_RDF15:BW85. The sample C_RDF15:BW75 exhibited the lowest C value (1.41 × 10−5), which confirmed the high rate of devolatilization, and the presence of oxygenated compounds as observed in its FT–IR spectrum. The C index was higher in C_RDF50:BW50 (2.03 × 10−5), indicating greater stability. These TG/DTG-derived indicators demonstrate how adjusting the RDF–biomass ratio can enable targeted modulation of ignition behavior, reactivity, and burnout, providing a basis for interpreting ash-related performance discussed in subsequent sections.

3.2.4. XRF Analysis and ICP–AES: Ash Behavior Assessment

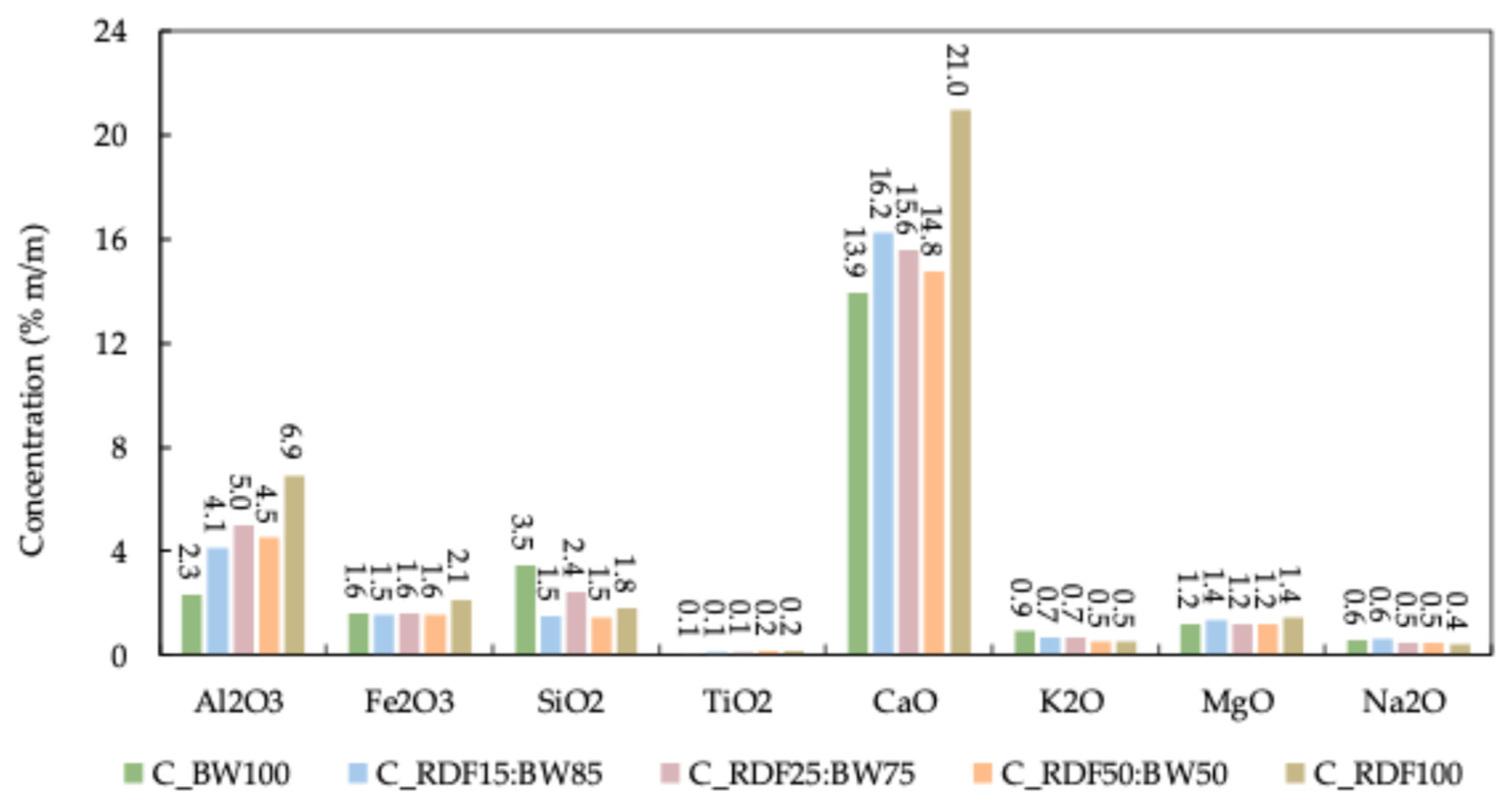

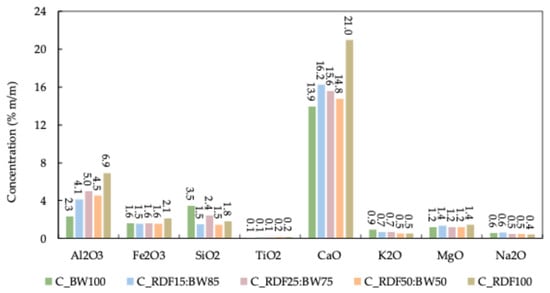

The ashes encompass a diverse array of inorganic components, with their composition typically expressed as the percentage by weight of the corresponding, stable oxides. Figure 7 illustrates the mineral composition of the ashes, and Table 3 presents the slagging, fouling, and agglomeration indices. These ash-related parameters are interpreted in conjunction with the TG/DTG-derived combustion behavior to assess the operational performance of the chars under thermal conversion conditions.

Figure 7.

Ash mineral composition of chars.

Table 3.

Calculated indices of slagging and fouling of chars. The corresponding slag or fouling tendencies were classified as severe (S), high (H), and low (L).

The findings clearly demonstrate that CaO is the predominant mineral across all chars, especially in C_RDF100, which exhibits the highest value of 21%. Al2O3 followed a trend like that of CaO. A comparable result was observed by Longo et al. [40]. The increase in CaO and Al2O3 in samples with a higher proportion of RDF may be attributed, on one hand, to the calcium naturally present in biomass waste and, on the other hand, to the frequent use of calcium and aluminum carbonates as additives in plastics, paper, and other materials that constitute RDF. Minerals such as Fe2O3, K2O, MgO, Na2O, and SO2 showed little variation between samples, consistently maintaining low levels regardless of the mixture. The predominance of CaO-rich ash phases is particularly relevant given their potential influence on burnout behavior and high-temperature mass loss observed in the TG curves.

The B/A values were exceptionally high across all chars, indicating a strong propensity for the formation of severe slag. This tendency is influenced by the melting temperatures of the ashes, where basic compounds generally lower the melting point, and acidic compounds increase it [54]. However, certain bases, such as CaO, can interact with other minerals to form compounds with high melting points, such as silicates, phosphates, and calcium oxides [36]. Despite minor variations among the different chars, the high concentration of basic oxides predominated, suggesting that the ash from these chars melted at lower temperatures. Consequently, these chars pose a significant risk of molten material formation in the reactor. This melting tendency is consistent with the extended high-temperature conversion and elevated Tf identified in the TG/DTG analysis, particularly for biomass-rich chars. Nevertheless, all samples exhibited high slag viscosity indices (Sr ≥ 72), which correspond to highly viscous slags and, consequently, a low slagging risk. This indicates that, although the B/A ratio suggests a severe tendency toward ash melting, the resulting molten phases are expected to be poorly mobile due to their high viscosity, thereby reducing their likelihood of adhesion and deposition on reactor surfaces. This highlights the critical role of slag viscosity in predicting deposition behavior in char thermal-conversion systems [36]. As illustrated in Table 3, all chars had a low viscosity index, with C_RDF100 showing the most favorable value. These results help explain why samples exhibiting prolonged oxidation stages in TG/DTG (higher Tf) do not necessarily present elevated slag adhesion risks. Despite the pronounced tendency to melt, the molten material remains highly viscous and not very mobile, thereby minimizing the risk of adhesion and slag accumulation on the furnace surfaces. Additionally, all samples exhibited a low alkalinity index, which can be attributed to the low alkali content (Na2O and K2O) in the chars [55,56]. The low alkali content is also consistent with the absence of sharp late-stage DTG peaks associated with alkali-driven ash reactions.

The Fu is derived from the acid-base ratio, known as the slag formation index. Despite the low concentrations of Na2O and K2O in the chars, the slag index was found to be severe, negatively impacting the Fu. The results indicated that Fu ranged from 2.6 to 4.8, placing it in the “high fouling potential” category. This apparent discrepancy between fouling indices and TG/DTG behavior highlights the importance of interpreting ash indices alongside combustion kinetics rather than in isolation. This suggests that although the B/A ratio indicates a severe slag risk, the threat of fouling on heat exchange surfaces remains low.

The BAI values, which ranged from 3.0 to 5.6, were significantly above the problematic threshold (<0.15). Bed agglomeration is likely when the ash melting point is low. Therefore, higher coefficients typically correlate with higher melting temperatures [36]. The findings suggest that bed agglomeration should not pose a problem during the thermal conversion of these chars. This conclusion aligns with the absence of abrupt mass-loss instabilities in the TG/DTG curves, indicating stable solid-phase behavior during conversion. Char composed solely of RDF exhibits the same higher value, indicating even greater stability against this phenomenon. In conclusion, although there is a strong tendency for char ash to melt, the high viscosity of the slag reduces deposit formation and supports a more stable thermal conversion process. When interpreted together with TG/DTG-derived combustion parameters, these ash-related indices confirm that RDF–biomass blending enables controlled reactivity while mitigating ash-related operational risks.

4. Conclusions

This work discusses the char production and characterization through thermogravimetric, spectroscopic, combustion indices, and compositional analyses of blended pellets from RDF and biomass waste. A key gap addressed in this work is the limited evidence on how pre-blending RDF with biomass wastes prior to slow pyrolysis can be used to intentionally tune char ignition behavior, reactivity, and ash-related performance under identical carbonization conditions. This study demonstrates that blending RDF with biomass preceding low pyrolysis enables effective tuning of char reactivity, ignition behavior, and ash-related performance. The results revealed that mixtures of RDF and BW significantly influenced the properties of the resulting chars, demonstrating clear synergistic effects on thermal stability and fuel behavior. In addition, this study addresses the gap in linking simple solid-phase descriptors (ultimate composition, proximate composition, and FT–IR signatures) with operationally relevant combustion indices (Ti, Tmax, DTGmax, C) and ash-related indicators, which are frequently reported separately for waste-derived chars.

C_RDF100 is distinguished by its high volatile matter content (42.66 wt.%, db) and high heating value (22.84 MJ/kg, db), which contribute to high devolatilization rates, albeit with increased thermal lability, as evidenced by a DTGmax of 4.99%/min and Tmax of 435 °C. The C_RDF50:BW50 and C_RDF25:BW75 formulations are notable for their ease of ignition at low temperatures (≈150 °C) and high C values (of approximately 2 × 10−5), while also exhibiting higher final combustion temperatures, indicating greater thermal recalcitrance during the burnout phase. Among the tested formulations, these intermediate RDF–biomass blends provide the most balanced combination of low ignition temperature, moderated reactivity, and stable burnout behavior. This directly supports blend selection for applications where ignition stability and burnout control are critical operational constraints.

The reduced intensity of functional bands in FT–IR, such as aliphatic C–H and O–H, supports the low devolatilization rate observed in TGA/DTG, facilitating more controlled and stable combustion with substantial energy yields (18–19 MJ/kg). It is worth noting that the C_RDF15:BW85 char showed a higher devolatilization rate, which can be explained by the dominance of the lignocellulosic fraction, forming catalytic char early on and thus promoting more efficient decomposition of the RDF polymeric component, without the diffusion barriers common in intermediate blends. This highlights that blend performance is not strictly proportional to blend ratio and that interaction effects can occur during co-pyrolysis.

Although all chars showed a strong tendency for ash melting, indicated by high acid-base indices, the low viscosity and alkalinity values of the slag helped mitigate operational problems by reducing adhesion to the reactor walls. This indicates that, despite a pronounced melting tendency, the high slag viscosity limits slag mobility and reduces deposition risks during thermal conversion. This addresses an applied gap in RDF-related char studies: translating ash composition into operationally meaningful indicators (slag mobility and deposition tendency) for thermal conversion systems.

It is important to note that future efforts, such as collecting, quantifying, and characterizing the liquid and gaseous products formed, along with reducing char chlorine content through leaching and washing processes, will significantly enhance the relevance of this research. These aspects are outside the scope of the present work and represent the next steps needed to extend the current solid-phase assessment toward full process evaluation.

The results of this study emphasize the importance of optimizing the composition of waste for the sustainable transformation of waste into high-energy-density fuels, reducing ash-related complications, and supporting their adoption in waste-to-energy conversion processes, particularly in systems where combustion stability and ash management represent critical operational constraints. Overall, this study helps close the gap between char characterization and practical operability by providing composition–combustion–ash relationships for RDF–BW blended pellets carbonized under consistent conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.S. and C.N.; investigation, S.M.S.; resources, M.G. and P.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.S. and C.N.; writing—review and editing, S.M.S., C.N., M.G. and P.B.; supervision, C.N., M.G. and P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by FUNDAÇÃO PARA A CIÊNCIA E A TECNOLOGIA, I.P. (FCT), grant number 2022.09990.BD, and by national funds through the FUNDAÇÃO PARA A CIÊNCIA E TECNOLOGIA, I.P. (FCT) under grant UID/05064/2025—https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/05064/2025 and, UIDB/04077/2020-2023 and UIDP/04077/2020-2023 (MEtRICs—Mechanical Engineering and Resource Sustainability Center).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RDF | Refuse-derived fuel |

| BW | Biomass waste |

| MSW | Municipal solid waste |

| MBT | Mechanical–biological treatment |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| LCA | Life cycle assessment |

| HHV | High heating value |

| ar | As received basis |

| db | Dry basis |

| daf | Dry ash free basis |

| TG | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| DTG | Derivative thermogravimetric analysis |

| FT–IR | Fourier-transform infrared spectrometer |

| Tmax | Temperature of maximum mass-loss rate |

| Ti | The ignition temperature |

| Tf | The burnout temperature |

| Di | Ignition index |

| C | Flammability index |

| B/A | The base-to-acid ratio |

| Sr | Slag viscosity index |

| Fu | Fouling index |

| Al | Alkali index |

| BAI | Agglomeration index |

| WtE | Waste-to-energy |

| WtG | Waste-to-gas |

References

- Chen, B.; Xiong, R.; Li, H.; Sun, Q.; Yang, J. Pathways for sustainable energy transition. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 1564–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.V.; Srivastava, V.K.; Mohanty, S.S.; Varjani, S. Municipal solid waste as a sustainable resource for energy production: State-of-the-art review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.H.; López-Maldonado, E.A.; Khan, N.A.; Villarreal-Gómez, L.J.; Munshi, F.M.; Alsabhan, A.H.; Perveen, K. Current solid waste management strategies and energy recovery in developing countries—State of art review. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 133088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibria, M.G.; Masuk, N.I.; Safayet, R.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Mourshed, M. Plastic Waste: Challenges and Opportunities to Mitigate Pollution and Effective Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2023, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanaraj, R.; Suresh Kumar, S.M.; Kim, S.C.; Santhamoorthy, M. A Review on Sustainable Upcycling of Plastic Waste Through Depolymerization into High-Value Monomer. Processes 2025, 13, 2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.M.; Gonçalves, M.; Brito, P.; Nobre, C. Waste-Derived Chars: A Comprehensive Review. Waste 2024, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, A.; Alves, O.; Sen, A.U.; Nobre, C.; Brito, P.; Gonçalves, M. Dry and Hydrothermal Co-Carbonization of Mixed Refuse-Derived Fuel (RDF) for Solid Fuel Production. Reactions 2024, 5, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, O.; Nobre, C.; Durão, L.; Monteiro, E.; Brito, P.; Gonçalves, M. Effects of dry and hydrothermal carbonisation on the properties of solid recovered fuels from construction and municipal solid wastes. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 237, 114101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, M.; Wagh, S.; Chakinala, A.G.; Pant, K.K.; Sharma, T.; Joshi, J.B.; Shah, K.; Sharma, A. Conversion of refuse derived fuel from municipal solid waste into valuable chemicals using advanced thermo-chemical process. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 329, 129653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Yin, L.; Wang, H.; He, P. Pyrolysis technologies for municipal solid waste: A review. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 2466–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandhini, R.; Berslin, D.; Sivaprakash, B.; Rajamohan, N.; Vo, D.V.N. Thermochemical conversion of municipal solid waste into energy and hydrogen: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 1645–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacovidou, E.; Hahladakis, J.; Deans, I.; Velis, C.; Purnell, P. Technical properties of biomass and solid recovered fuel (SRF) co-fired with coal: Impact on multi-dimensional resource recovery value. Waste Manag. 2018, 73, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, A.A.; Ikubanni, P.P.; Emmanuel, S.S.; Fajobi, M.O.; Nwachukwu, P.; Adesibikan, A.A.; Odusote, J.K.; Adeyemi, E.O.; Abioye, O.M.; Okolie, J.A. A comprehensive review on the similarity and disparity of torrefied biomass and coal properties. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haykiri-Acma, H.; Kurt, G.; Yaman, S. Properties of Biochars Obtained from RDF by Carbonization: Influences of Devolatilization Severity. Waste Biomass Valorization 2017, 8, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miskolczi, N.; Gao, N.; Quan, C.; Laszlo, A.T. CO2 reduction by chars obtained by pyrolysis of real wastes: Low temperature adsorption and high temperature CO2 capture. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2025, 14, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Luo, H.; Colosi, L.M. Slow pyrolysis as a platform for negative emissions technology: An integration of machine learning models, life cycle assessment, and economic analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 223, 113258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soka, O.; Oyekola, O. A feasibility assessment of the production of char using the slow pyrolysis process. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Zhou, J.; Qin, Q.; Xie, C.; Luo, Z. Physicochemical characteristics of biomass-coal blend char: The role of co-pyrolysis synergy. Energy Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdziarz, A.; Jerzak, W.; Wądrzyk, M.; Sieradzka, M. Benefits from co-pyrolysis of biomass and refuse derived fuel for biofuels production: Experimental investigations. Renew. Energy 2024, 230, 120808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerzak, W.; Mlonka-Mędrala, A.; Gao, N.; Magdziarz, A. Potential of products from high-temperature pyrolysis of biomass and refuse-derived fuel pellets. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 183, 107159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.T.; Dai, B.; Wu, X.; Hoadley, A.; Zhang, L. A critical review of ash slagging mechanisms and viscosity measurement for low-rank coal and bio-slags. Front. Energy 2021, 15, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.M.; Souza, P.; Nobre, C.; Rijo, B.; Gonçalves, M.; Engvall, K.; Brito, P. RDF Co-processing through CO2 Gasification Using Waste-based Catalysts. In Proceedings of the 32nd European Biomass Conference and Exhibition, Marseille, France, 24–27 June 2024; pp. 118–120. [Google Scholar]

- Rashwan, S.S.; Boulet, M.; Moreau, S. Catalyzing Refuse-Derived Fuel Understanding: Quantified Insights From Thermogravimetric Analysis. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2024, 146, 091203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, N.L.; Septiariva, I.Y.; Sarwono, A.; Qonitan, F.D.; Sari, M.M.; Gaina, P.C.; Ummatin, K.K.; Arifianti, Q.A.M.O.; Faria, N.; Lim, J.-W.; et al. Substitution of Garden and Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Plastic Waste as Refused Derived Fuel (RDF). Int. J. Renew. Energy Dev. 2022, 11, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyà, J.J.; García-Ceballos, F.; Azuara, M.; Latorre, N.; Royo, C. Pyrolysis and char reactivity of a poor-quality refuse-derived fuel (RDF) from municipal solid waste. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 140, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syguła, E.; Świechowski, K.; Stępień, P.; Koziel, J.A.; Białowiec, A. The prediction of calorific value of carbonized solid fuel produced from refuse-derived fuel in the low-temperature pyrolysis in CO2. Materials 2021, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, C.; Vilarinho, C.; Alves, O.; Mendes, B.; Gonçalves, M. Upgrading of refuse derived fuel through torrefaction and carbonization: Evaluation of RDF char fuel properties. Energy 2019, 181, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E949-88; Standard Test Method for Total Moisture in a Refuse-Derived Fuel. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2004.

- ASTM E897-88; Standard Test Method for Volatile Matter in the Analysis Sample of Refuse-Derived Fuel. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2004.

- ASTM E830-87; Standard Test Method for Ash in the Analysis Sample of Refuse-Derived Fuel. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2004.

- Vyazovkin, S.; Burnham, A.K.; Criado, J.M.; Pérez-Maqueda, L.A.; Popescu, C.; Sbirrazzuoli, N. ICTAC Kinetics Committee recommendations for performing kinetic computations on thermal analysis data. Thermochim. Acta 2011, 520, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G. Combustion characteristics and kinetic analysis of biomass pellet fuel using thermogravimetric analysis. Processes 2021, 9, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wzorek, M.; Junga, R.; Yilmaz, E.; Bozhenko, B. Thermal decomposition of olive-mill byproducts: A TG-FTIR approach. Energies 2021, 14, 4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wnorowska, J.; Ciukaj, S.; Kalisz, S. Thermogravimetric analysis of solid biofuels with additive under air atmosphere. Energies 2021, 14, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangwanda, G.T.; Madyira, D.M.; Ndungu, P.G.; Chihobo, C.H. Combustion characterisation of bituminous coal and pinus sawdust blends by use of thermo-gravimetric analysis. Energies 2021, 14, 7547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman, J.; Baláš, M.; Lisý, M.; Lisá, H.; Milčák, P.; Elbl, P. An overview of slagging and fouling indicators and their applicability to biomass fuels. Fuel Process. Technol. 2021, 217, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Shan, R.; Li, X.; Pan, J.; Liu, X.; Deng, R.; Song, J. Characterization of 60 types of Chinese biomass waste and resultant biochars in terms of their candidacy for soil application. GCB Bioenergy 2017, 9, 1423–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, B.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S. Study of synergistic effects in co-pyrolysis of biomass and plastics from the perspective of phase reactions. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2025, 186, 106951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Burra, K.G.; Lei, T.; Gupta, A.K. Co-pyrolysis of waste plastic and solid biomass for synergistic production of biofuels and chemicals—A review. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2021, 84, 100899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, A.; Pacheco, N.; Panizio, R.; Vilarinho, C.; Brito, P.; Gonçalves, M. Carbonization of Refuse-Derived Fuel Pellets with Biomass Incorporation to Solid Fuel Production. Fuels 2024, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Rocha, L.A.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, H. Insights into the char-production mechanism during co-pyrolysis of biomass and plastic wastes. Energy 2024, 312, 133642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbrolini Tiburcio, R.; Malpeli Junior, M.; Tófano de Campos Leite, J.; Minoru Yamaji, F.; Pereira Neto, A.M. Physicochemical and thermophysical characterization of rejected waste and evaluation of their use as refuse-derived fuel. Fuel 2021, 293, 120359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.M.; Longo, A.; Gonçalves, M.; Nobre, C.; Calado, L.; Brito, P. Refuse derived fuel pellets as feedstock for energy production. In WASTES: Solutions, Treatments and Opportunities IV, 1st ed.; Vilarinho, C., Castro, F., Quina, M., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherymoosavi, S.; Verheyen, V.; Munroe, P.; Joseph, S.; Reynolds, A. Characterization of organic compounds in biochars derived from municipal solid waste. Waste Manag. 2017, 67, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandiyanto, A.B.D.; Oktiani, R.; Ragadhita, R. How to read and interpret ftir spectroscope of organic material. Indones. J. Sci. Technol. 2019, 4, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- InstaNANO FTIR Functional Group Database Table with Search-InstaNANO. InstaNano 2024. Available online: https://instanano.com/all/characterization/ftir/ftir-functional-group-search/ (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- He, X.; Liu, X.; Nie, B.; Song, D. FTIR and Raman spectroscopy characterization of functional groups in various rank coals. Fuel 2017, 206, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.K.S.; Júnior, D.L.; da Silva, Á.M.; Cupertino, G.F.M.; de Souza, E.C.; Delatorre, F.M.; Ucella-Filho, J.G.M.; de Oliveira, P.R.S.; Rodrigues, B.P.; Júnior, A.F.D. How pyrolysis conditions shape the structural and functional properties of charcoal? A study of tropical dry forest biomass. Renew. Energy 2025, 243, 122575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çepelioǧullar, Ö.; Pütün, A.E. Thermal and kinetic behaviors of biomass and plastic wastes in co-pyrolysis. Energy Convers Manag. 2013, 75, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainability Directory. Biochar Stability. Sustainability Directory 2025. Available online: https://climate.sustainability-directory.com/term/biochar-stability/ (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Burra, K.G.; Gupta, A.K. Kinetics of synergistic effects in co-pyrolysis of biomass with plastic wastes. Appl. Energy 2018, 220, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, V.; Bhattacharya, S.; Shastri, Y. Pyrolysis of mixed municipal solid waste: Characterisation, interaction effect and kinetic modelling using the thermogravimetric approach. Waste Manag. 2019, 90, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Wang, K.; Bing, X.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Guan, B.; Yu, J. Pyrolysis of plastics-free refuse derived fuel derived from municipal solid waste and combustion of the char products in lab and pilot scales: A comparative study. Fuel 2024, 359, 130335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniowski, W.; Taler, J.; Wang, X.; Kalemba-Rec, I.; Gajek, M.; Mlonka-Mędrala, A.; Nowak-Woźny, D.; Magdziarz, A. Investigation of biomass, RDF and coal ash-related problems: Impact on metallic heat exchanger surfaces of boilers. Fuel 2022, 326, 125122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degereji, M.U.; Ingham, D.B.; Ma, L.; Pourkashanian, M.; Williams, A. Prediction of ash slagging propensity in a pulverized coal combustion furnace. Fuel 2012, 101, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, T.; Xing, P.; Pourkashanian, M.; Darvell, L.I.; Jones, J.M.; Nimmo, W. Prediction of biomass ash fusion behaviour by the use of detailed characterisation methods coupled with thermodynamic analysis. Fuel 2015, 141, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.