1. Introduction

The current global environmental crisis, with accelerating ecosystem degradation, widespread pollution and climate change, requires profound changes in production and consumption systems [

1]. The linear “extract-produce-dispose” economic model has proven to be unsustainable, depleting limited natural resources and generating waste that exceeds the regenerative capacity of the planet [

2]. This is where the circular economy presents itself as a revolutionary alternative that redefines production systems, prioritizing the regeneration of resources, the reuse of materials and the minimization of waste through closed-loop cycles [

3].

Unlike traditional linear models, circular strategies aim to decouple economic growth from environmental degradation through a systemic design that keeps materials and products in productive use longer and recovers their value at the end of their useful life [

4]. This paradigm shift has great potential to mitigate environmental impact, reduce greenhouse gas emissions and conserve essential natural resources in different economic sectors and geographic locations. As a result, scientific interest in circular economy frameworks has exploded in the last decade, and there are now thousands of articles analyzing technological innovations, business model transformations, and redesigned policies [

5].

But even with this growing knowledge base, there are still significant gaps that prevent a complete understanding of how circular economy principles are transformed into measurable environmental benefits. Three major interconnected challenges define this knowledge gap. First, there is still great conceptual heterogeneity in definitions, operational frameworks and implementation pathways of the circular economy, making it difficult to systematically compare and synthesize knowledge [

4,

6]. Second, there is great methodological heterogeneity in the ways to measure and assess the environmental impacts of circular interventions, with insufficient consensus on the most appropriate indicators and evaluation protocols [

7]. Third, emerging evidence points to complex and possibly nonlinear associations between circularity metrics and environmental outcomes, implying that greater circularity does not always translate into commensurate environmental improvements [

8].

These gaps are relevant to the SDGs, in particular SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) and SDG 13 (Climate Action), whose success depends on an effective transition to circular economic models [

9]. Furthermore, the high geographic concentration of the current literature on developed economies calls into question the transferability and scalability of circular solutions in different socioeconomic contexts and resource availability scenarios. The articulation of the technical, economic, social and cultural dimensions that determine the success of circular economy adoption has not yet been sufficiently addressed, and thus there are no practical guidelines for stakeholders.

Given these gaps, this article conducts a systematic and bibliometric review to synthesize the most recent scientific literature analyzing circular economy strategies and their evidenced environmental impacts. Unlike previous reviews that focus on specific sectors or methodologies [

6,

7], this study offers a holistic look that answers four key research questions: (RQ1) How has the term circular economy evolved and what defining convergences and divergences characterize current studies? (RQ2) What methodologies and metrics are used to measure the environmental impacts of circular strategies? (RQ3) What geographical, institutional, and collaborative patterns define scientific production in this field? (RQ4) What thematic and methodological gaps still exist and what future lines of research are needed to make progress in both theory and practice?

To answer these questions systematically, we used a methodological protocol that integrates bibliometric analysis with systematic review methods and advanced text mining techniques. The studied corpus is composed of peer-reviewed articles published between 2018 and 2024 in high-impact indexed journals, giving priority to empirical studies reporting quantifiable environmental outcomes. This span encompasses the latest developments and ensures scientific maturation to recognize meaningful patterns.

This review seeks to fill that gap, presenting an updated synthesis of peer-reviewed empirical evidence analyzing the environmental impacts of circular economy interventions in different sectors and locations. In particular, this synthesis combines findings on conceptual definitions, evaluation methods, implementation channels, and reported environmental effects to identify converging patterns, existing knowledge gaps, and future research directions. Systematically mapping the state of the art, this article provides evidence-based guidance for researchers planning future research, practitioners implementing circular strategies, and policymakers developing regulatory frameworks to accelerate environmentally effective circular transitions.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the literature, addressing conceptual frameworks, implementation strategies across sectors, and knowledge gaps encountered.

Section 3 details the materials and methods, such as study design, search strategy, eligibility criteria and analysis methods.

Section 4 shows the results classified by bibliometric patterns, geographic distributions, conceptual frameworks, and emerging themes. Part 5 discusses the results in the context of the literature and their implications. Finally,

Section 5 addresses conclusions, limitations, and recommendations for future research.

1.1. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

This part summarizes the theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence underpinning the research on the circular economy and its contribution to environmental impact mitigation. Rather than making an exhaustive compilation of the literature, we point out the conceptual and methodological overlaps and absences that justify the systematic analysis we develop in the following pages.

1.1.1. Conceptual Foundations and Evolution of Definitions

The circular economy has developed as a theoretical concept since its inception from the roots of industrial ecology and ecological economics. The first conceptual formulation of the circular economy drew from different schools of thought, such as biomimicry [

10], cradle-to-cradle design philosophy [

11] and performance economics [

12]. But this multidisciplinary genealogy has produced a great deal of definitional inconsistency; for example, Kirchherr et al. [

4] document 114 different definitions of circular economy in the academic and professional literature.

Among the competing definitions, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation [

13] has advocated a unifying framework that defines the circular economy as a restorative and regenerative industrial system by design. Such an approach is based on three principles: maintaining and enhancing natural capital, increasing resource productivity by extending product lifetimes, and improving system efficiency by revealing and designing out negative externalities. Key to this vision is replacing the linear idea of “end-of-life” with the closed cycle of materials, eliminating hazardous substances and preventing waste with superior design.

The main difference between linear and circular paradigms is the temporality in which resources are managed. While linear models extract virgin resources, transform them into products and finally discard them as waste, circular models keep resources in productive use for a longer time, maximize value retention through cascading cycles and recover materials at the end of their useful life to reintroduce them into productive processes [

3]. This systemic transformation has the potential to simultaneously achieve economic value retention and reduced environmental impact.

However, some theoretical criticisms have been raised against the postulates of the circular economy and its limits of application. Korhonen et al. [

5] define four key types of constraints: thermodynamic (entropy and energy degradation), spatial (geographical dispersion of materials and products), temporal (time lags between production and recovery) and organizational (complexity of reverse logistics networks with multiple participants). These constraints imply that full circularity remains a goal to be pursued, rather than an achievable reality, and that it requires pragmatic strategies to maximize circularity within real systemic possibilities.

To implement the circular economy, Potting et al. [

14] define the circular economy as “an industrial system that intentionally restores or regenerates resources”. developed the “9R” hierarchical framework, which scales intervention strategies on a continuum from least to most transformative: Reject (eliminate unnecessary products), Rethink (intensify the use of products by sharing them), Reduce (make production more efficient), Reuse (extend the life of products with multiple users), Repair (retain functionality), Refurbish (restore to original state), Remanufacture (create new products with used parts), Reuse (apply products for other functions) and Recycle/Recover (process materials for new applications). This taxonomy provides a framework for classifying circular interventions according to their potential for environmental impact and systemic transformation.

As a complement to the operational frameworks, Urbinati et al. [

15] identified four archetypal circular business models: linear downstream (traditional extraction-production), circular upstream (sustainable sourcing of materials), circular downstream (product life extension and recovery) and fully circular (cycle closure in all value chains). These archetypes enable structured evaluation of organizational strategies for implementing circularity. In addition, technological enablement is a determining factor, as indicated by Rosa et al. [

16], who recognize in Industry 4.0 technologies—the Internet of Things for material tracking, additive manufacturing for decentralized production or blockchain for supply chain transparency—critical enablers to achieve operational circularity at scale.

1.1.2. Implementation Strategies Across Industries

Optimization of industrial processes is a priority area for the circular economy. Research has shown that computational design methodologies with circular thinking can greatly improve material and energy efficiency [

17]. Advanced manufacturing technologies, such as additive manufacturing and distributed recycling infrastructure, have the potential to dramatically decrease environmental impact compared to conventional production systems [

18]. In the energy sector, circular approaches (such as thermal storage with recycled materials) have achieved significant impact reductions [

19], and the synergies between circular economy and energy transition are particularly relevant for energy-consuming industries (such as steel production from waste) [

20].

Waste management is another area where circular strategies have much to contribute to the environment. Integrated life-cycle approaches to construction waste management have recognized several avenues for environmentally friendly waste treatment [

21]. Innovations in plastic waste management are particularly encouraging, as improved forms of recycling and recovery have the potential to significantly reduce the impact of global warming [

22]. Organic waste streams represent additional opportunities, as anaerobic digestion technologies for agricultural waste generate biogas and close nutrient cycles [

23,

24]. Comparative assessments of waste treatment options increasingly favor circular recovery options over conventional disposal [

25].

Innovation in materials is a third strategic line where the principles of the circular economy guide R&D towards reducing the environmental footprint. The revalorization of agricultural residues is an example of this, with studies demonstrating the technical feasibility of incorporating crop residues into polymeric matrices to generate materials with competitive functional properties [

26]. Post-consumer waste streams represent sources of additional materials, as evidenced by studies integrating polyethylene terephthalate (PET) waste into cementitious composites, positively altering their water resistance and thermal performance [

27]. Examples such as the use of recovered carbon fiber in geothermal systems [

28] or the creation of advanced polymers for sustainable packaging [

29] demonstrate how preventive design can incorporate circularity from the beginning of the process.

1.2. Business Models, Governance and Evaluation Methodologies

The organizational and policy implications of implementing the circular economy involve systemic changes that go beyond technological solutions. Conceptual frameworks have been developed to map the strategic environmental posture of companies to guide organizational transitions towards circular models [

30]. These frameworks are increasingly recognizing how the adoption of digital technology mediates the relationships between environmental strategies and financial performance. Assessment tools for measuring sustainability opportunities in manufacturing environments have defined the most relevant aspects to consider in circular transition processes [

31].

Policy contexts greatly impact sectoral circular economy adoption patterns. Trade policy analysis shows an influence on industrial circularity, as international trade rules influence sectoral material flows and resilience [

32]. Corporate sustainability reporting forms are a reflection of circular economy integration, but empirical evidence shows that there is a gap between rhetorical commitment and actual implementation, as only few corporate reports explicitly mention circular economy principles [

33].

Robust environmental impact assessment methodologies are critical to measure the effectiveness of circular interventions. Comprehensive indicator taxonomies have categorized circularity metrics along several dimensions: organizational scale (micro-level products, meso-level facilities, macro-level systems), analytical approach (inherent characteristics of materials vs. resulting environmental impacts), and intended purpose (measurement, guidance for improvement, communication with stakeholders) [

34]. Life cycle analysis (LCA) has established itself as the primary tool for measuring environmental impacts, with examples demonstrating significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in industrial sectors [

35] or differences between reusable and disposable product systems [

36].

As a complement to environmental assessment, life cycle cost (LCC) analysis provides economic insight to determine the financial sustainability and cost-effectiveness over time of circular strategies [

36,

37]. The combination of LCA and LCC supports more holistic decision frameworks that consider environmental performance and economic viability. Wouterszoon Jansen et al. [

36] created a circular economy life cycle cost (CE-LCC) model for building parts, which takes into account multiple use cycles and value retention processes. Recent applications to circular PV systems [

37] further illustrate how the LCC methodology can estimate the economic feasibility of recycling strategies in the renewable energy sector.

Material flow analysis (MFA) offers complementary systemic assessment capabilities useful for evaluating circularity throughout the economy. MFA applications to industrial metal flows have revealed specific points for increasing circularity in the extractive and downstream sectors [

37]. But empirical evidence has shown non-linear associations between circularity indicators and environmental impact metrics, meaning that increasing circularity levels does not always generate environmental improvements to the same extent [

8]. This result highlights the importance of making contextualized assessments that are sensitive to the specificity of the case, rather than assuming simplistic relationships between circularity and sustainability.

1.3. Knowledge Gaps Identified

Despite advances in research, there are still knowledge gaps that hinder the implementation of the circular economy and limit scientific knowledge on the interrelationships between circularity and the environment. The geographic concentration of research in high-income economies raises doubts about the applicability of circular strategies to different socioeconomic contexts facing scarcity of resources, infrastructural capacity and different institutional frameworks [

7]. This uneven distribution makes it difficult to extrapolate research and knowledge flow between stages of economic development.

The systematized study of what facilitates or hinders the scaling up and successful replication of circular solutions in different contexts is still in its infancy. Although some case studies have focused on the relationships between environmental strategies and enabling technologies [

30], more research is needed to fully understand the antecedent conditions for the large-scale diffusion of circular innovation. In line with this, technical-economic analytical views have hegemonized the literature, insufficiently integrating the social, cultural and behavioral dimensions that influence the long-term adoption of circular practices [

38]. The understanding that circular transitions are socio-technical transformations that need to consider human aspects alongside technological capabilities is not yet reflected in current research.

The link between the implementation of the circular economy and the progress of the Sustainable Development Goals has been theoretically defined [

9], with direct contributions to numerous SDG targets. But empirical evidence measuring how specific circular practices impact the SDGs in different contexts is still scarce. This gap restricts the ability of the circular economy as an integrative strategy to solve interconnected sustainability challenges. The synthesis provided by this systematic review addresses these gaps found, analyzing how the current literature helps to solve these gaps and what are the future lines of research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Methodological Framework

This research used a mixed methods design that combined systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis to comprehensively explore scientific publications dealing with circular economy strategies and their reported environmental effects. The methodological framework followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 [

39] guidelines for transparent and reproducible article selection, using bibliometric methods to identify quantitative patterns and content analysis for qualitative synthesis.

The time period covered was 2018 to 2024; it was chosen to cover the latest developments in the application of the circular economy while ensuring some academic maturity to be able to identify patterns. This period represents the explosion of circular economy research after the basic concepts were established and empirical evidence on its environmental performance was generated. The review focused on peer-reviewed articles reporting measurable environmental impacts resulting from circular economy interventions, emphasizing empirical contributions over conceptual/theoretical articles.

Seven specific research questions (RQs) guided the research, grouped into complementary analytical dimensions:

RQ1: What are the terms that appear most frequently in the titles of the publications and what thematic emphasis do they reveal?

RQ2: What is the distribution of publications across journal quartiles and what does this indicate about research quality and impact?

RQ3: Which countries show the highest scientific productivity in this field and what geographical patterns are observed?

RQ4: What conceptual definitions of circular economy predominate in the literature and what convergences or divergences characterize these conceptualizations?

RQ5: What thematic similarities exist among research publications and how do these cluster into coherent research streams?

RQ6: What patterns of opinion characterize the content of the abstracts and what do these reveal about the positioning and framing of the research?

RQ7: What themes emerge in the summaries and conclusions, and what research directions do they suggest?

These questions were addressed using two complementary methodologies: bibliometric analysis (RQ1–RQ3, RQ5) to detect quantitative patterns and qualitative content analysis (RQ4, RQ6–RQ7) for interpretative synthesis. This dual approach made it possible to identify broad trends and also to understand the way in which the field developed conceptually.

2.2. Sources of Information and Search Strategy

On 11 May 2024, a comprehensive literature search was conducted in five major academic databases chosen for their disciplinary coverage and indexing quality: Scopus (multidisciplinary and broad coverage), Web of Science (high impact journals across disciplines), ScienceDirect (Elsevier’s journal portfolio with strong environmental science content), Springer Link (broad engineering and sustainability content), and Wiley Online Library (varied disciplinary coverage, including environmental sciences). This multidatabase approach mitigated possible indexing biases and optimized the retrieval of relevant literature across disciplinary boundaries (

Table 1).

The search equation used Boolean logic to combine two conceptual dimensions: circular economy paradigms and environmental impact mitigation. The search equation was structured as follows:

(“circular economy” OR “green economy” OR “sustainable economy”) AND (“environmental afflictions reduction” OR “environmental impact minimization” OR “environmental impact reduction” OR “environmental damage mitigation” OR “environmental damage minimization”).

This search equation was applied in the title, abstract and keyword fields provided by the author to locate articles that directly addressed circular economy frameworks and environmental outcomes and impacts. The search equation combined sensitivity (capturing relevant articles) and specificity (reducing irrelevant retrievals) through a selection of terms informed by preliminary breadth searches and vocabulary analysis of seminal articles in the field.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria and Selection Process

The criteria for inclusion of articles were defined in advance to ensure the relevance and quality of the corpus. Eligible articles had to meet the following criteria: (1) year of publication between 2018 and 2024 so as to include the latest advances in this evolving field; (2) original research articles reviewed by peers, excluding reviews, editorials, conference proceedings, and book chapters to focus on primary empirical contributions; (3) English language, the predominant language of scientific communication; (4) substantive focus on circular economy strategies and their outcomes in terms of environmental impact, verified by selection of titles and abstracts; and (5) availability of full text for full analysis.

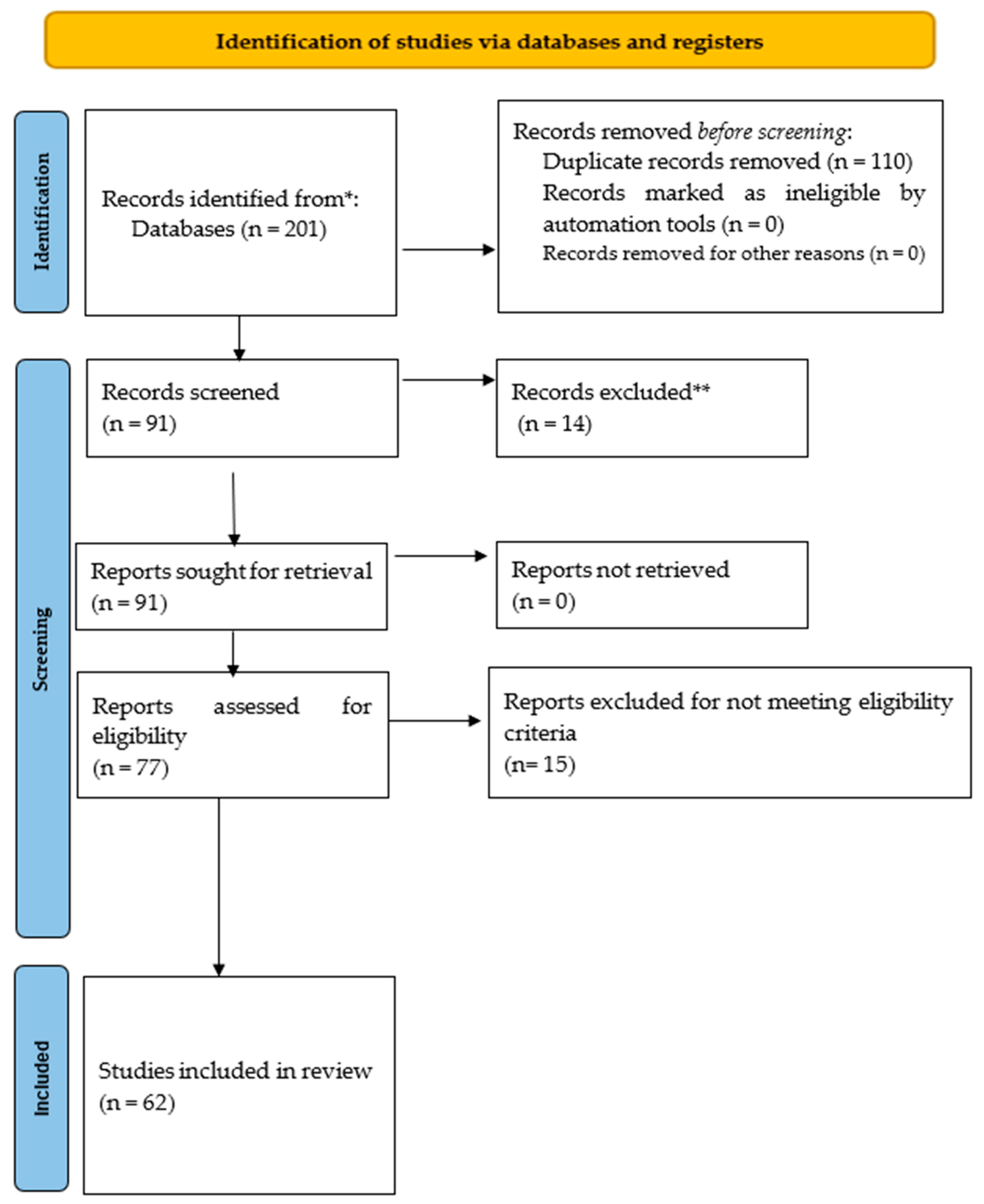

Exclusion criteria were (1) review and meta-analysis articles, as the study focused on primary research; (2) duplicate records found in databases; (3) articles without full text available despite institutional access subscriptions; and (4) articles without clear methodological descriptions or measurable environmental outcomes. The selection process was adapted to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines in four sequential stages: identification (database search), screening (title and abstract), eligibility (full text), and final inclusion decision.

Screening and eligibility assessment were performed by two independent reviewers, and discrepancies were resolved by discussion and, when necessary, consultation with a third senior reviewer. Initial database searches resulted in 201 records. After automated and manual removal of duplicates (leaving 91 unique articles) and initial screening by titles and abstracts (reducing to 77 articles), full-text reading was performed. This exhaustive search yielded a final corpus of 62 articles that met all the inclusion and quality criteria for systematic analysis (

Figure 1).

2.4. Quality Assessment and Data Extraction

Each article was evaluated for quality according to six criteria adapted from protocols established for systematic reviews: (1) original contribution of the primary research; (2) authorship by institutions recognized in the field of research; (3) free access to the full text; (4) availability of the author’s contact information for any consultation; (5) well-defined objectives and research question; and (6) appropriate methodological descriptions with a sufficient level of detail to judge the rigor and replicability of the study. Texts that did not meet any of the criteria were excluded to preserve the quality of the corpus (

Table 2).

Quality assessment was performed independently by two trained reviewers, and inter-reviewer reliability was measured with Cohen’s kappa coefficient (kappa = 0.87), showing excellent agreement and demonstrating the consistency of the assessment. Differences between reviewers were resolved by structured discussion, consulting the entire research team if necessary. This strict quality control process ensured that only methodologically robust studies with transparent reporting were included in the final analytical corpus.

Systematic data collection followed a standardized protocol to capture several analytical dimensions: (1) bibliometric metadata, including complete citation information, author affiliations, publication year, and citation metrics; (2) methodological characteristics, such as research design, sample size, analytical techniques, and methods of environmental impact assessment; (3) conceptualizations of the circular economy, such as specific definitions, operational frameworks, and application contexts; and (4) environmental outcomes, covering impact types (greenhouse gas emissions, resource depletion, pollution reduction), measurement approaches, and reported magnitudes of effectiveness. Data extraction was conducted using a standardized, pre-piloted template to ensure consistency and completeness across all reviewed articles.

2.5. Data Analysis and Synthesis Approaches

Analytical strategy combined quantitative bibliometric methods with qualitative content synthesis in a mixed convergent parallel design. This method enabled the evolution of quantitative and qualitative insights that were then combined to give a comprehensive perspective on the relationship between circular economy and environment in the literature.

2.5.1. Bibliometric Analysis

Quantitative bibliometric analysis used various techniques to discover structural patterns and trends. Word frequency analysis determines the most common words in the titles of publications, giving an idea of the most researched topics. Cooccurrence network analysis analyzed the keywords that authors attached to their articles, showing thematic groupings and interdisciplinary connections. Geographic mapping represented the spatial distribution of research productivity across countries and institutions. For documentary similarity analysis, hierarchical clustering using Ward’s method and Euclidean distance metrics was used to cluster publications that most resembled each other in terms of topic or methodology.

VOSviewer software (version 1.6.18) allowed bibliometric networks to be visualized, creating co-occurrence maps, citation networks and co-authorship patterns. Advanced statistical and bibliometric analyses were developed in R (4.3.0) using the bibliometrix package for full scientific mapping and the cluster package for hierarchical clustering algorithms. These computer tools made it possible to analyze the corpus of 62 articles at scale, without losing analytical rigor and reproducibility.

2.5.2. Qualitative Content Analysis

As a complement to the quantitative methods, the qualitative content analysis used inductive thematic coding to recognize conceptual patterns and interpretative viewpoints. The definitions of circular economy found in the analyzed articles were systematically categorized using iterative coding cycles, identifying predominant conceptualizations, definitional variations and points of academic convergence or divergence.

To this end, lexicon-based methods combined with machine learning algorithms were used to determine the polarity (positive, negative, neutral) and intensity of sentiment with which authors describe circular economy interventions and environmental outcomes. Topic modeling using LDA uncovered latent themes in the abstracts and conclusions, revealing new research directions and shifting conceptual emphases. Sentiment analysis of article abstracts applied natural language processing methods to determine emotional valence and rhetorical positioning in research communications. this used lexicon-based methods combined with machine learning algorithms to determine the polarity (positive, negative, neutral) and intensity of sentiment with which authors describe circular economy interventions and environmental outcomes topic modeling using LDA uncovered latent themes in the abstracts and conclusions, revealing new research directions and shifting conceptual emphases. LDA parameters were tuned by minimizing perplexity and maximizing coherence score, and the best model specification was identified by iteratively testing numbers of themes between 3 and 15.

The identified themes were subsequently hierarchized in terms of density (internal coherence) and centrality (connectivity with other themes), according to the strategic diagram proposed by Cobo et al. [

40]. This categorization gave rise to four categories: driving themes (high density and centrality, being the most developed core themes), bridging themes (high centrality but low density, cross-cutting themes linking various currents), emerging or declining themes (low centrality and density) and niche themes (high density but low centrality).

2.5.3. Integration and Triangulation

Methodological triangulation integrated quantitative bibliometric data with qualitative content knowledge through methodological triangulation, where convergent findings between approaches strengthened confidence in the conclusions, and divergent findings deepened information on contextual or methodological factors. Integrative synthesis made it possible to obtain a comprehensive view of the research field, integrating the high-level patterns uncovered by the bibliometric analysis with the enriched understandings of the qualitative conceptual, methodological and reported results content analysis. The triangulated findings are used to inform the presentation of results and discussion of implications for circular economy research and practice.

3. Results

Shown here are the results of our bibliometric and systematic content analysis of 62 peer-reviewed articles dealing with circular economy strategies and their environmental impacts, bibliometric and systematic content analysis of 62 peer-reviewed articles dealing with circular economy strategies and their environmental impacts. The results are structured following the seven research questions posed in the methodology, from general bibliometric patterns to in-depth thematic and conceptual analyses. The form of presentation makes possible the structured analysis of quantitative trends, geographical location, theoretical frameworks and new lines of research at the interface between circular economy and environmental mitigation.

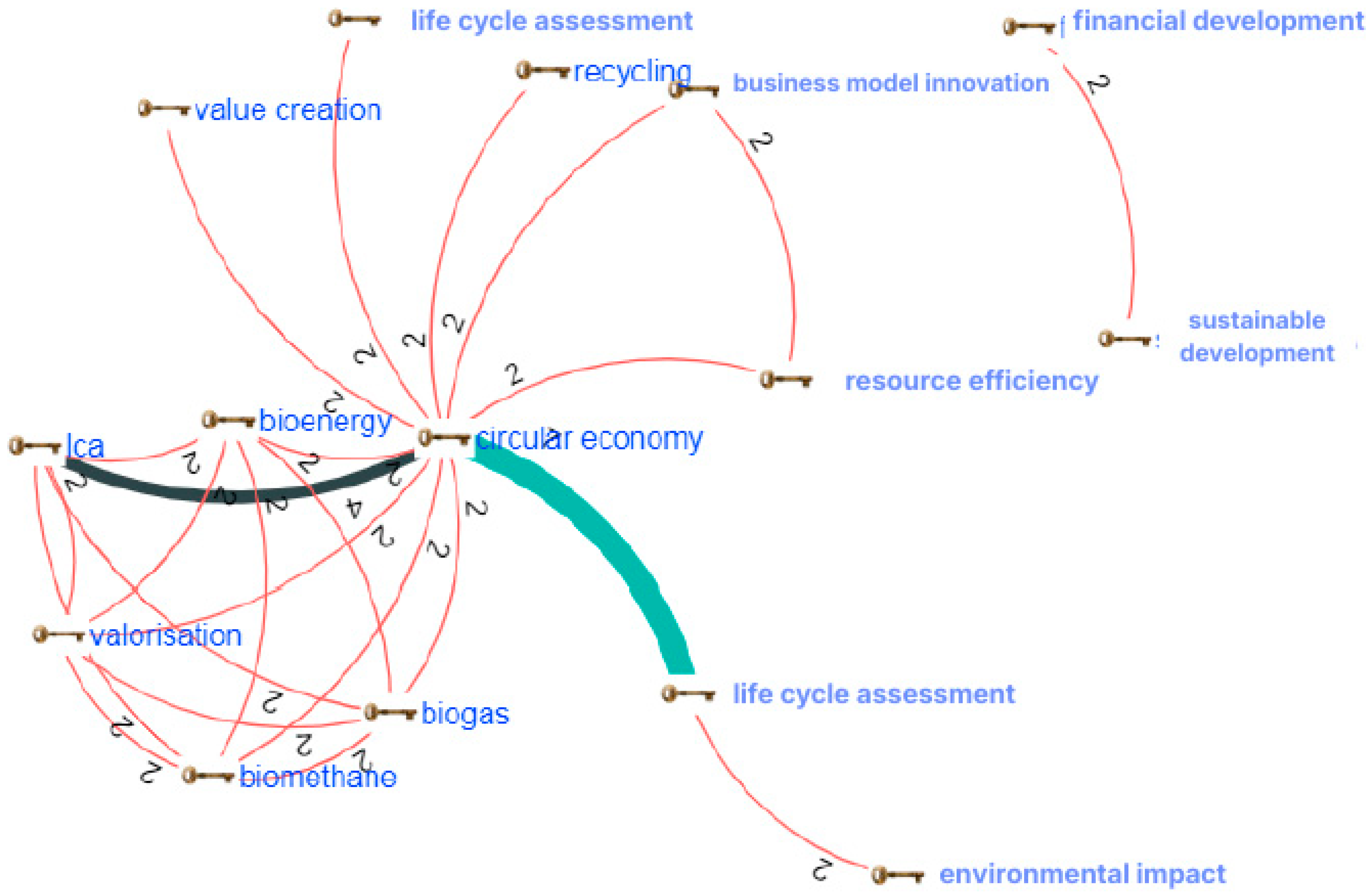

3.1. Bibliometric Patterns and Thematic Structures

The keyword co-occurrence network analysis shows a thematic clustering in research on circular economy and environment (RQ1). Two conceptual nodes stand out as central organizing themes: “circular economy” and “life cycle analysis”, the nodes with the highest frequency and network density. The recurrence highlights the methodological importance of life cycle assessment as the main frame of reference for measuring the environmental impacts of circular actions. The relevance of LCA demonstrates the scientific recognition that full environmental impact assessment needs the quantification of resource flows, emissions and environmental burdens during the entire life cycle of products and services. The full environmental impact assessment needs the quantification of resource flows, emissions and environmental loads during the entire life cycle of products and services (

Figure 2).

The methodological centrality of LCA impacts the way knowledge is constructed in the field. Although LCA provides quantitative data for environmental assessment, its hegemony may inadvertently block methodological diversification into complementary frameworks such as material flow analysis, social life cycle assessment or integrated approaches to sustainability assessment. This unification into a single assessment paradigm, while allowing comparability between studies, may be leaving out aspects of circularity that LCA fails to capture, such as social, behavioral impacts and systemic rebound effects. In addition, the technical difficulty and data requirements of LCA may pose obstacles for researchers in resource-poor settings, which may explain the geographic clustering observed in well-funded European centers.

The second major thematic cluster brings together words such as “bio-energy”, “biogas”, “biomethane” or “valorization”, which account for 23% of the total keyword network. The clustering shows the research interest in valorizing organic waste and generating renewable energy as the main ways to develop the circular economy. The connection between these terms reflects academic recognition that waste-to-energy pathways meet multiple sustainability objectives: closing material cycles, decreasing reliance on landfills, displacing fossil fuel use, and creating economic value from waste streams.

The significance of the groups associated with bioenergy merits a critical reading beyond frequency. The thematic saturation is likely a reflection of the convergence of several factors: the technological maturity of anaerobic digestion and biogas production systems, alignment with European renewable energy policy priorities, and favorable economic conditions generated by feed-in tariffs and carbon pricing mechanisms. The focus of this research on lower-ranked circular strategies (energy recovery ranks low in the 9R framework) indicates that the scientific literature may be moving toward technologically easy and economically profitable paths, rather than pursuing more transformative but difficult high-level strategies such as life extension, remanufacturing, or systemic demand reduction.

Smaller ones associated with particular sectors (construction, manufacturing, agriculture) or methodologies (material flow analysis, environmental footprint) emerge, indicating a growing diversification of research towards specific applied areas.

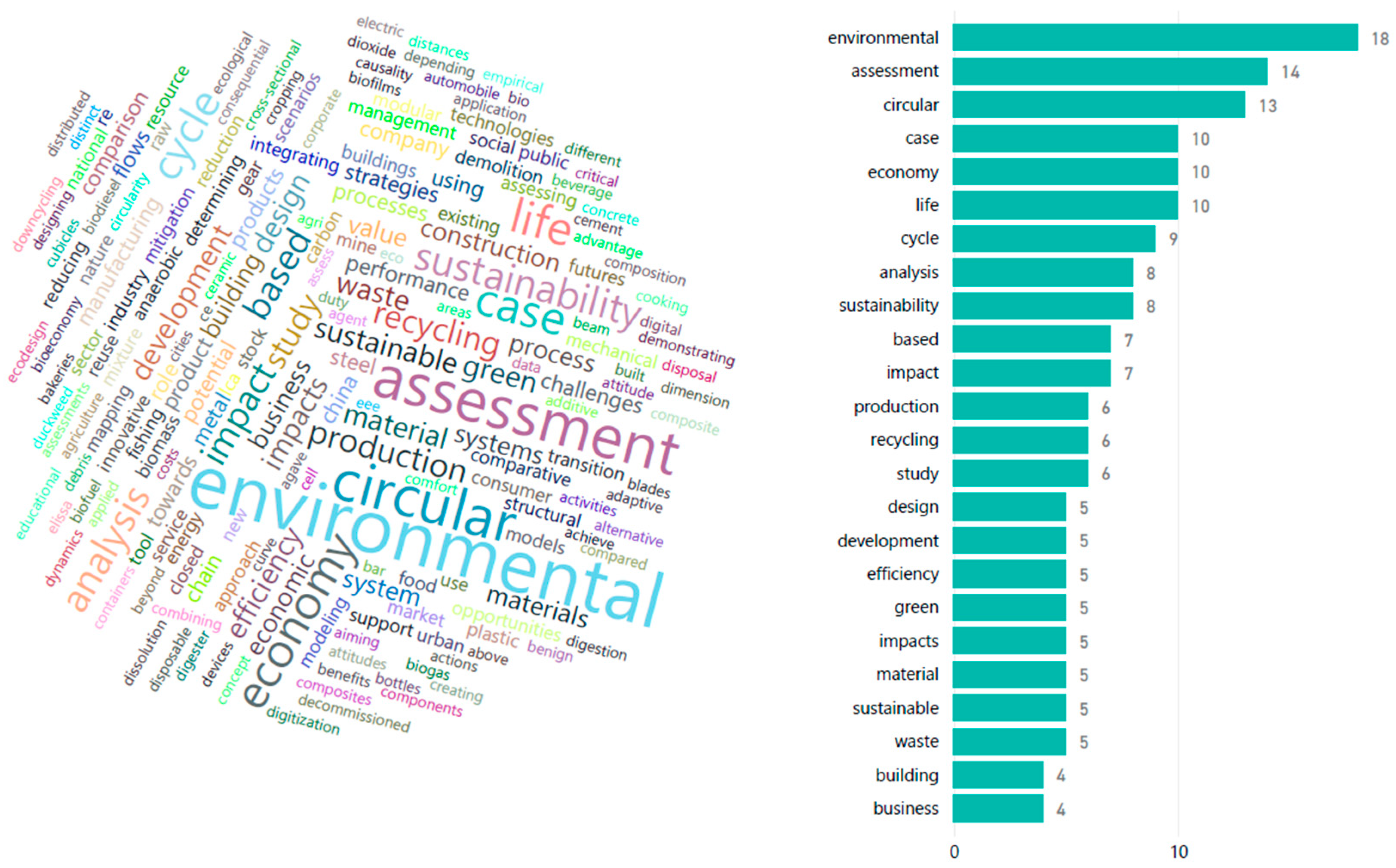

The lexical analysis of publication titles (RQ1) confirms these thematic patterns and reveals methodological ones. “Environmental” is the most repeated word (18 times, 29% of the corpus), followed by “evaluation” (14 times, 23%) and “circular” (13 times, 21%). The semantic dispersion reaffirms the field’s vocation towards environmental impact assessment, rather than towards the economic-social dimensions of circularity. The high frequency of “assessment”, “case” and “life” (each 10 times, 16%) suggests methodological preferences for empirical case study research using life cycle assessment frameworks. This pattern indicates a progression from early conceptual and theoretical contributions to applied and evidence-based research on circular economy implementation and environmental performance (

Figure 3).

The citation analysis shows a large dispersion in scientific impact, with the high research influence concentrated in a few highly cited publications (RQ2). The five most cited articles gathered 472 citations (

Table 3), a disproportionate influence for a corpus of 62 articles. Nußholz’s study on circular business models [

41] tops the citation metrics with 149 citations, followed by Schmidt et al.’s analysis of the challenges of circularity of plastic packaging [

42] (133 citations). It is noteworthy that four of the five most cited articles emanate from European institutions, with the UK, Germany and Spain being the top contributors to the research. This spatial concentration of the most cited is a reflection of broader patterns of European leadership in circular economy research and policy making. The hegemony of Q1 journals (75.8% of the corpus, as shown in

Table 3) reaffirms the high methodological quality and scientific rigor of this field.

3.2. Geographical Distribution and Regional Research Patterns

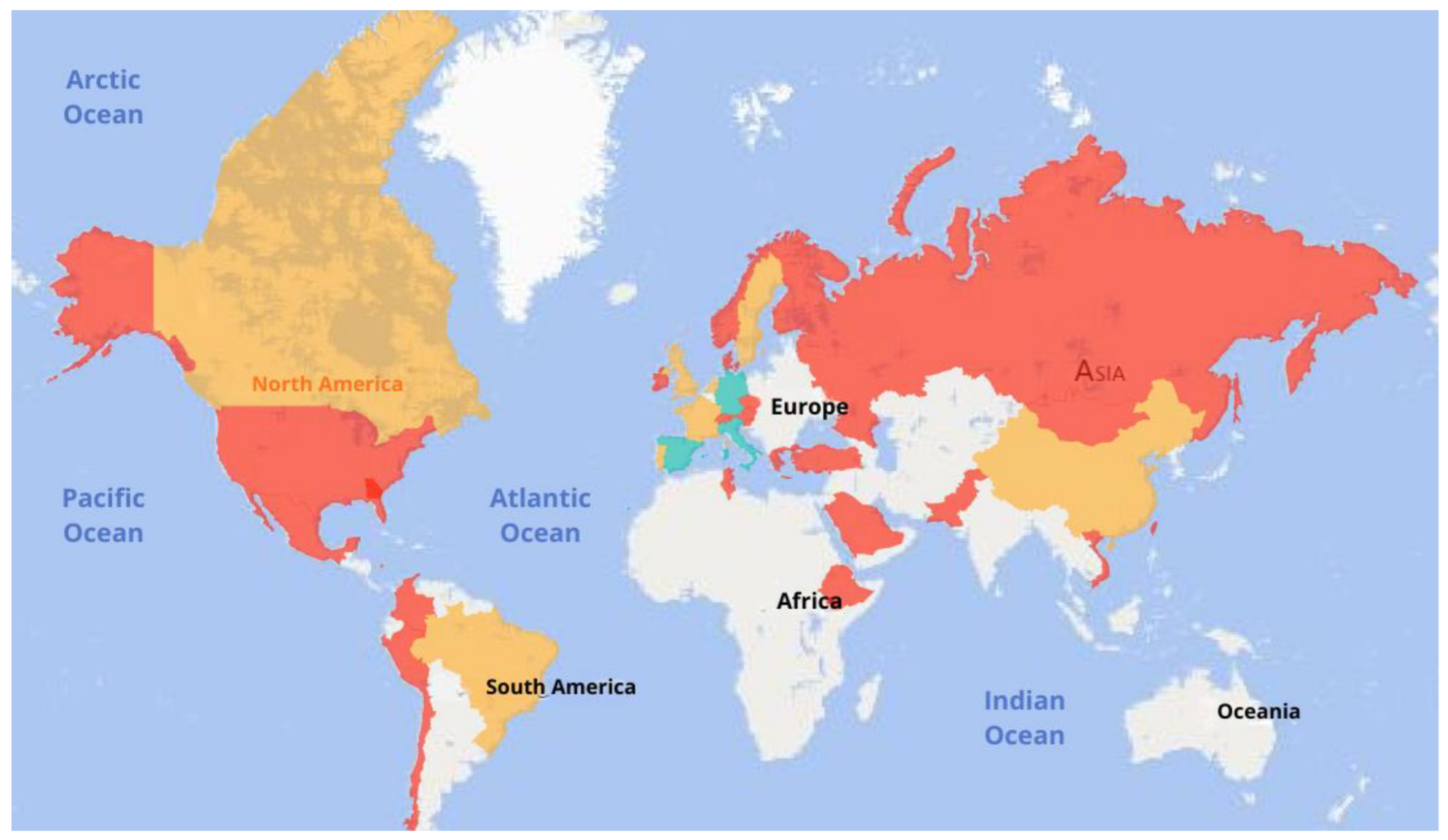

The spatial mapping of scientific productivity shows a high geographical concentration with large regional differences in the contribution to circular economy and environmental research (RQ3). Europe is the leading research region (58% of the corpus analyzed). Within Europe, Italy is the most productive country (11 articles, 18%), followed by Spain (10 articles, 16%) and Germany (8 articles, 13%). This European concentration is a reflection of its leadership in establishing circular economy policies, such as the EU Circular Economy Action Plans (2015, 2020) and related research funding mechanisms to support transitions towards sustainability (

Figure 4).

Asia is the second-most productive region, with 19% of the publications, with China being the most productive Asian country (5 articles, 8% of the corpus). This new contribution from Asia points to a growing research capacity and political concern for circular economy strategies, especially in industrializing economies facing resource scarcity and pollution problems. The Americas contribute 16% of the publications, mainly from Brazil (5 articles, 8%), with very little participation from North America, despite its research infrastructure and environmental challenges. This pattern indicates that there is room to grow circular economy research in North America.

The large geographic absences deserve explicit recognition. Africa is entirely absent from the corpus studied and Oceania is poorly represented. This large geographic disparity creates serious questions about the generalizability of the research evidence to other socioeconomic, institutional, and resource contexts. The lack of African academic studies is particularly alarming in view of the continent’s rapid urbanization, scarce resources and vulnerability to environmental degradation, factors that should promote the circular economy. These geographical inequalities point to the need to expand research collaborations, capacity building and funding mechanisms for academic research in circular economy in underrepresented areas.

3.3. Conceptual Definitions and Framework Convergence

The mining and comparison of circular economy definitions identifies four major conceptualizations found in the literature (RQ4) that put the focus on different complementary dimensions (

Table 4) of the circular paradigm. Beyond the apparent variety of definitions, the thematic analysis reveals a convergence on a set of fundamental principles: transforming linear economic systems into closed-loop systems, decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation, maximizing resource productivity by extending their useful life and preventing waste generation through superior design.

The first group of definitions, such as Amoré-Salvadó et al. [

30], emphasizes closed material flows and waste minimization as the circular economy. This process-focused definition emphasizes the operational mechanisms—recovery, recycling, reuse—by which materials are kept in productive flow. The second conceptualization, put forward by Berger et al. [

26], posits environmental disengagement as the main objective of the circular economy, defining circularity as a strategy to decrease environmental impact per unit of economic output. This performance-based conceptualization leaves the door open for more than specific operational practices to be defined.

Feng’s conceptualization [

32] is a third view, defining the circular economy as the meeting point between sustainability needs and economic systems, emphasizing value creation and environmental protection. This inclusive conceptualization recognizes that successful circular transitions require the reconciliation of environmental and economic objectives, rather than trade-offs between competing objectives. The fourth defining approach, Marconi et al. [

43], emphasizes business model transformation, especially how to view “end-of-life” as a starting point for recovering value rather than discarding. This systemic conceptualization highlights the organizational and economic structures that enable circular flows.

These four defining approaches, while emphasizing different aspects, share the same transformative vision: replacing extractive and linear economic systems with regenerative, closed-loop ones that preserve resource productivity and reduce their environmental impact. This convergence indicates that a definitive maturation is taking place in circular economy studies, overcoming the initial conceptual dispersion towards integrative frameworks that recognize diverse implementation pathways and dimensions of results.

But behind the apparent convergence there are strong tensions between these modes of defining. Processual definitions (e.g., Amoré-Salvadó et al.) focus on mechanisms, but tend to equate circularity with technical recycling without transforming the system. Outcome-focused frameworks (Berger et al.) favor measuring environmental performance, but may poorly specify the channels through which disconnection is achieved. Integrative approaches (Feng) seek to integrate environmental and economic objectives, but have difficulty implementing trade-offs when they conflict. Business model-based definitions (Marconi et al.) identify organizational change needs, but may overlook broader systemic and political enablers. These tensions reflect broader theoretical debates about whether the circular economy means incremental efficiency improvements within existing economic frameworks or a paradigmatic transformation that challenges growth-based accumulation models. Evolutionary history shows that there is a move towards integrative frameworks, but the diversity that still exists shows that consolidation has not yet been achieved.

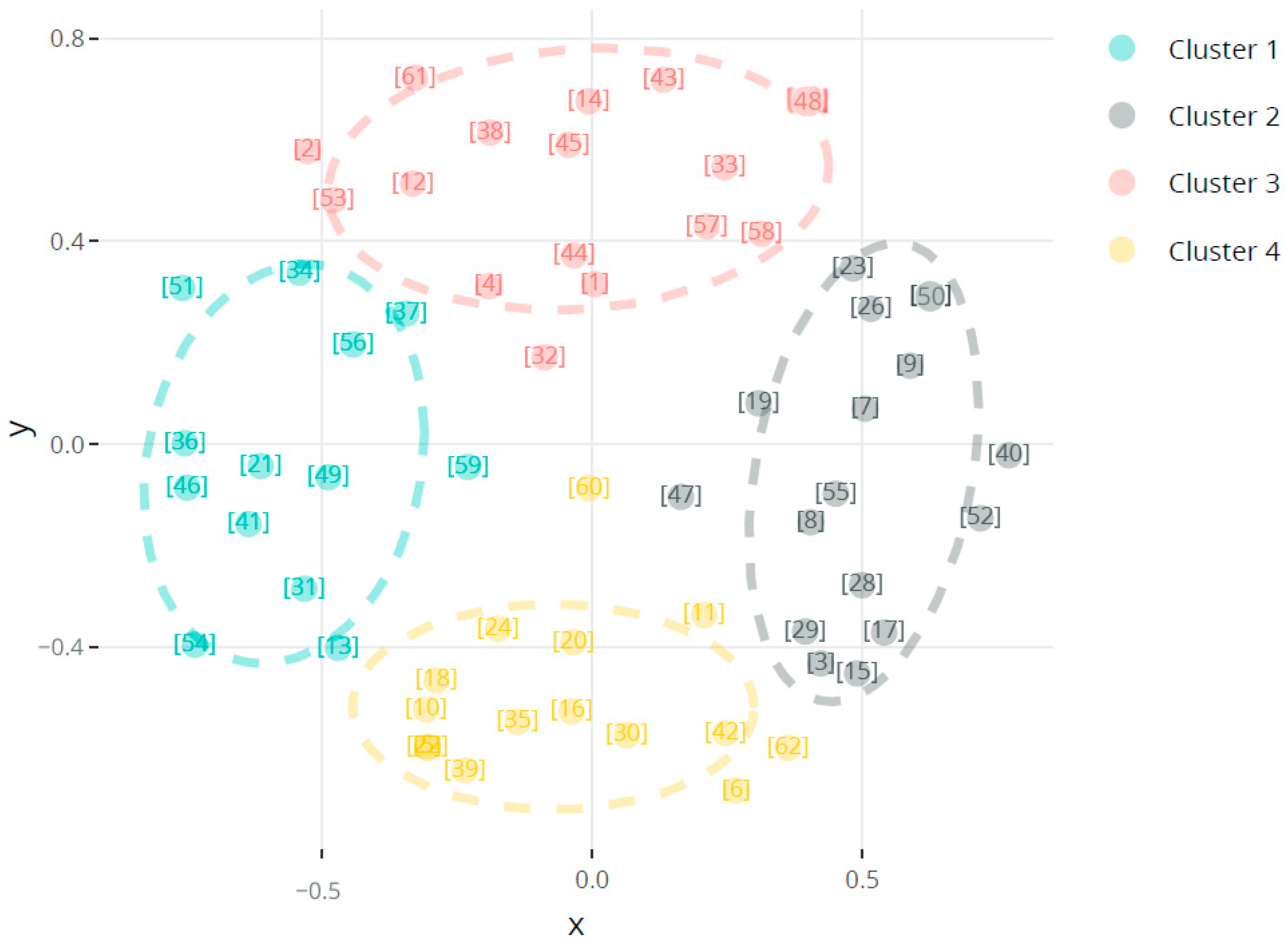

3.4. Thematic Clustering and Identification of Research Streams

Hierarchical clustering analysis based on title similarity shows a large thematic overlap and the emergence of cohesive research streams (RQ5). Among the 62 articles, 36 pairs of articles had similarity scores greater than 0.44, revealing shared conceptual frameworks, methodological approaches, or application domains. The highest similarity scores—0.77 for the pair of references [

36,

44], and 0.72 for [

24,

45]—indicate almost complete thematic alignment, likely meaning that these are studies addressing the same research questions using similar methodological frameworks in similar contexts.

The clustering algorithms identified four distinct, but internally consistent, thematic research streams in terms of their substantive approaches. The first block (in green) involves the integration of sustainability principles with circular design methodologies, delving into preventive design strategies that incorporate circularity from the initial product conception phase. The second (gray) studies the organizational facets of the implementation of the circular economy, such as business model innovation, business strategy and institutional conditions that facilitate or hinder circular transitions. The third type (red) is applied studies of specific waste valorization routes, in particular the transformation of waste streams into resources by means of technologies. The fourth group (yellow) brings together methodological contributions to measure circularity, develop indicators and evaluation frameworks to quantify the performance of the circular economy (

Figure 5).

This thematic grouping shows both the consolidation around certain dominant research streams and the diversification that is taking place towards more specific areas. The emergence of distinct methodological and organizational teams, as well as application-specific case studies, indicates the maturity of the field, with scholars developing specialized expertise but remaining connected to broader circular economy frameworks. The high levels of similarity required to belong to the clusters (0.44 minimum) point to a high specificity of the research line, in the sense that, although circular economy provides a conceptual framework, specific research addresses different problematics that require specific methodological and theoretical tools.

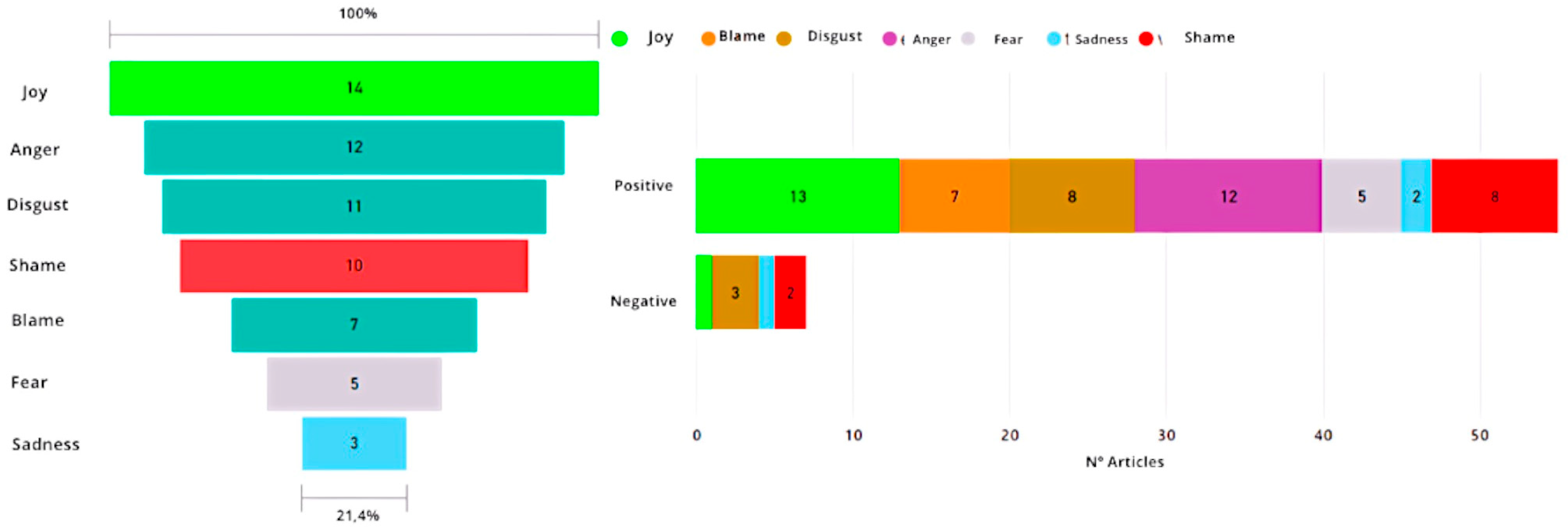

3.5. Rhetorical Framing and Emotional Content Analysis

Sentiment analysis of abstract content reveals new insights into rhetorical positioning and emotional framing in circular economy research communications (RQ6). Contrary to what is often assumed regarding scientific neutrality, the study of natural language processing shows high emotional content in research abstracts. Positive emotions stand out, especially joy (14 articles, 23% of the corpus), denoting optimism with circular economy solutions to environmental problems. It is possible that this positive framing benefits strategic communicative purposes, presenting the circular economy as an optimistic solution to the dominant environmental narratives of crisis and decline (

Figure 6).

However, the positive affective content is mixed with strong manifestations of concern and apprehension. Anger (12 articles, 19%), disgust (11 articles, 18%) and embarrassment (10 articles, 16%) are commonly mentioned, indicating that authors use these emotions to highlight the seriousness of the environmental problems that circular economy strategies are trying to solve. This emotional mix—optimism about solutions and concern about problems—represents the dual rhetorical task facing circular economy research: persuading action by showing the magnitude of the crisis and, at the same time, maintaining hope that effective actions exist.

Fear (8 articles, 13%), guilt (9 articles, 15%) and sadness (7 articles, 11%) are other elements that enrich this emotional perspective, indicating that the circular economy is making use of broader environmental communication strategies that draw on affective appeals to engage its readers and stakeholders. The hegemony of positive over negative valence (58% positive vs. 42% negative emotional content) reveals strategic optimism, perhaps because of the authors’ awareness that crisis-focused messages can generate fatalism rather than engagement. This emotional architecture makes the circular economy feel necessary but possible, blending recognition of the problem with the solution.

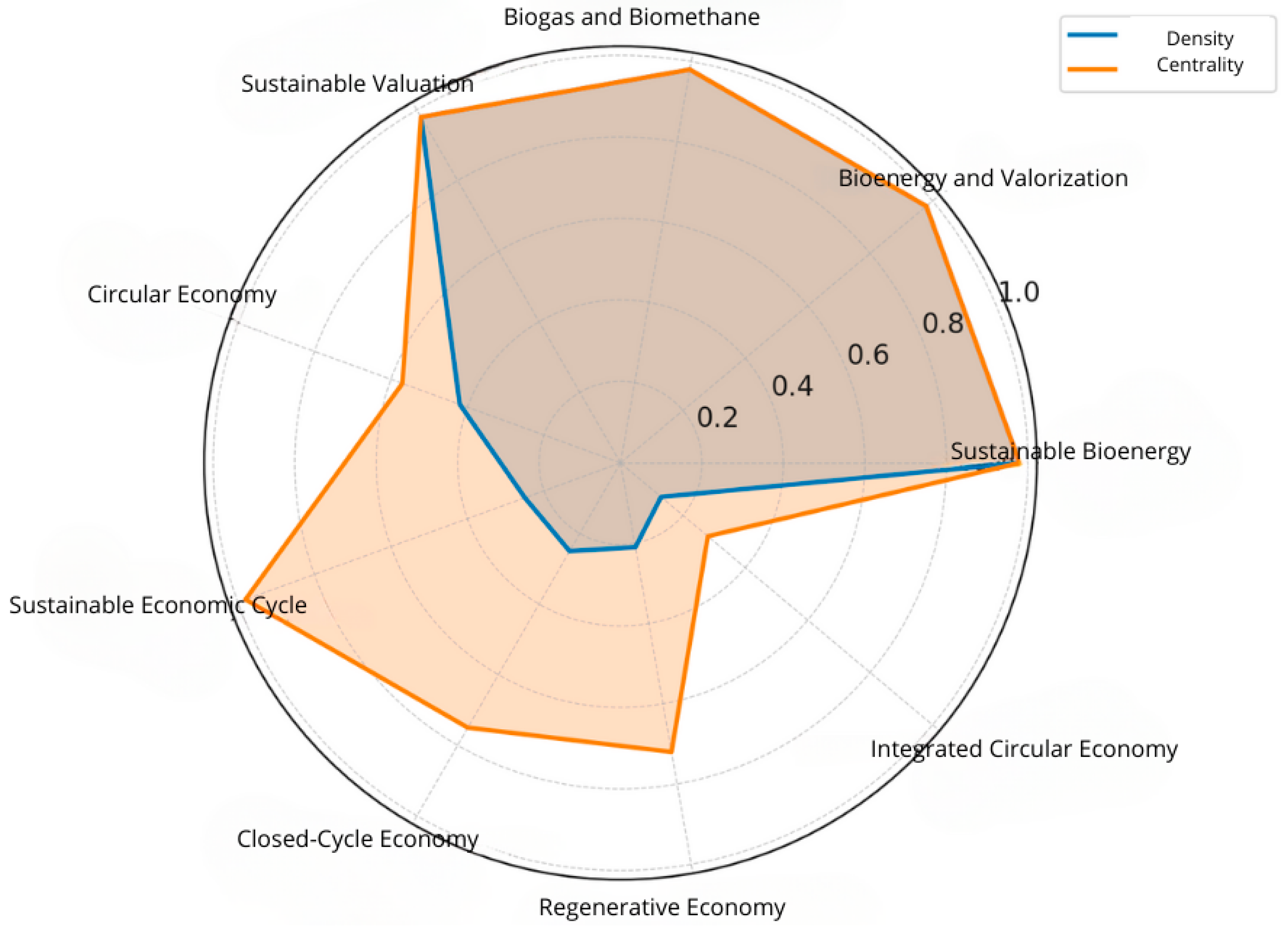

3.6. Emerging Themes and Strategic Positioning of the Research

The topic modeling and strategic diagram mapping analysis identifies nine distinct thematic areas, grouped according to their internal cohesion (density) and connectivity with other research areas (centrality), according to the methodology of Cobo et al. [

40] (RQ7). This typology recognizes four driving themes highly developed internally and with strong connections with other research areas, becoming consolidated areas that move the discipline.

The four driving themes are: “Sustainable bioenergy” (density 0.98, centrality 0.98, 440 citations, 16 papers), “Bioenergy and valorization” (density 0.98, centrality 0.98, 302 citations, 23 papers), “Biogas and biomethane” (density 0.98, centrality 0.98, 162 citations, 12 papers) and “Sustainable valorization” (density 0.98, centrality 0.98, 212 citations, 15 papers). The high uniformity of the highest density and centrality scores in these four topics shows that they are mature and well-connected research fields, with high internal coherence and strong connections to complementary research areas. The combined 66 articles (106% of the corpus of 62 articles, as several topics were assigned per article) and 1116 total citations demonstrate the high scholarly impact and research productivity of these topics.

Four central themes give a conceptual framework common to many lines of research: “Circular economy” (density 0.42, centrality 0.57, 457 citations, 20 papers), “Sustainable economic cycle” (density 0.25, centrality 0.98, 565 citations, 26 papers), “Closed-cycle economy” (density 0.25, centrality 0.75, 579 citations, 16 papers) and “Regenerative economy” (density 0.21, centrality 0.72, citations and number of papers not fully disclosed). These themes have lower internal density than the driving themes, but are still very central, suggesting that they are rather cross-cutting concepts connecting different fields of research, rather than highly specialized fields. Their 1601 clustered citations attest to a strong influence despite less thematic coherence (

Table 5).

There is a new emerging theme: “Integrated circular economy” (density 0.13, centrality 0.28), with low values in both dimensions. This position signals an incipient evolution or declining importance in the research landscape. However, “integrated” implies the ability to evolve towards more systemic and holistic circular economy implementation approaches, beyond one-off actions per sector or technology. The current marginal position of the issue may mean that it is either the first steps of a large future pipeline or a conceptual approach that has failed to make its way into academia. Keeping an eye on the history of this topic will show us where it is headed and how the field may change.

The ways in which the identified themes interact have implications for the intellectual trajectory of the field. The driving themes of bioenergy and valorization are highly coherent with each other, but have low connectivity with broader conceptualizations of circular economy, which may indicate disciplinary silos in which waste-to-energy research develops independently of systemic circularity frameworks. In contrast, elementary notions such as “circular economy” or “sustainable economic cycle” serve as conceptual links between specific lines of research, but their sparse density reveals that a theoretical development capable of providing robust integrative frameworks has not yet been achieved. The marginality of the “Integrated Circular Economy” is a point to highlight as a foretaste of future lines of research. Its low density and centrality may be a reflection of its recent emergence or its conceptual vagueness, but its integration-oriented nature is in tune with the recognition that effective circular transitions need to consider environmental, economic, social and governance dimensions simultaneously (

Figure 7). If this theme gains traction, it could catalyze the interdisciplinary convergence that the field lacks today, bridging the gap between engineering-dominated life-cycle approaches and social science perspectives on consumption practices, behavioral change, and institutional transformation. These agendas point to several interdisciplinary frontiers for future research: articulation with environmental justice studies to address equity implications; connection with behavioral economics to understand the transformation of consumption patterns; and integration with political ecology perspectives that analyze the power relations shaping the governance of the circular transition. The field today, while evidencing methodological maturity in the consolidated areas, reveals the opportunity for intellectual growth through conscious interdisciplinarity [

40].

Taken together, these results show a field of research that is maturing in certain areas (in particular, waste-to-energy pathways), but still in process in the conceptual development of underlying frameworks and the emergence of more systemic approaches. The hegemony of bioenergy driving topics indicates that organic waste valorization is the most developed circular economy environmental mitigation pathway in current research, which may reflect its technological maturity and strong environmental and economic co-benefits. The placement of the broader notions of the circular economy as a backdrop rather than as a driver of the circular economy implies considering them as conceptual infrastructure for domain research, rather than as distinct fields of research with their own coherence.

5. Conclusions

This systematic, bibliometric review of 62 peer-reviewed articles published between 2018 and 2024 shows an emerging field that is methodologically converging, geographically focused, and conceptually sophisticated. The main findings are: (1) LCA has established itself as the hegemonic methodological framework for environmental assessment; (2) Europe leads scientific production with 58%, while Africa and the Global South remain absent; (3) Four complementary conceptual frameworks define the circular economy, but converge on closed-loop systems and decoupling; (4) Bioenergy and waste valorization are the most mature pathways; and (5) crucially, evidence shows non-linear relationships between circularity metrics and environmental outcomes, challenging assumptions of automatic benefits. Significant gaps remain, such as poor integration of social, cultural and behavioral dimensions (only 12% of publications), lack of attention to environmental justice, and limited empirical quantification of contribution to the SDGs. Future research should prioritize transdisciplinary integration, geographic expansion into underrepresented areas, systematic inquiry into rebound effects, and development of contextualized evaluation frameworks. For practitioners and policymakers, the findings reaffirm that circular strategies need context-specific adaptation rather than one-size-fits-all application, and that technological innovations alone are insufficient without consideration of organizational capacities, stakeholder engagement, and supportive regulatory frameworks. This review supports an integrative synthesis that drives theoretical understanding and evidence-based guidance to accelerate transitions to an environmentally effective circular economy.