Abstract

Particulate matter is widely known as a significant air pollutant due to its proven detrimental impact on human health. Furthermore, ultrafine particles (UFPs) are those with diameters smaller than 100 nm, which can cause numerous serious health effects. Thus, identifying the sources of UFPs is essential for formulating effective mitigation strategies. Quantifying the contributions of particle sources can be performed by measuring particle number size distributions (PNSDs) for specific size ranges. This study was conducted in the city of Belgrade, the capital of Serbia, and one of the largest cities in the Balkans peninsula, which, within the European framework, belongs to a region and urban area characterized by high levels of atmospheric particulate matter pollution. In addition, there is a lack of studies addressing UFP levels and their sources in Serbia, including Belgrade. Several criteria pollutants were measured, together with the UFPs and equivalent black carbon (BC) at the urban background site in the city of Belgrade, Serbia, for the period from February to August 2024. The particle sources were analyzed using Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) of PNSDs along with equivalent BC, PM10, PM2.5, O3, SO2, NO, NO2 and NOx. Seven source types were identified, characterized, and quantified, including two traffic sources (separated into traffic 1 and traffic 2), mixed traffic, an urban diffuse source, nucleation and nucleation growth sources, and a biomass burning source. Traffic-related sources were found to have the most significant contribution at around 40% of total particles emitted, followed by nucleation-related sources (24%) and biomass burning (20%). This is the first study performed in Serbia and Belgrade that addresses source apportionment of PNSD, for particles in the range 10–400 nm.

1. Introduction

Ultrafine particles (UFPs), defined as particles with diameters less than 100 nm, have attracted a lot of interest from the aerosol and health communities in recent years, as a significant pollutant, which should be considered among the other regulated air pollutants [1,2,3]. Health studies on the impacts of UFPs started in the 1990s using animal toxicological studies [4] and later, the effects of generated UFPs on humans in clinical studies [5]. It was discovered that UFPs can be deposited through diffusion in the tracheobronchial and pulmonary regions of the respiratory tract [3,6]. Smaller particles can travel deep into the airways and lodge in the alveoli. There, cytokines and chemokines recruit phagocytic cells such as neutrophils and macrophages, which then immerse the particles via phagocytosis. Particle-laden phagocytes are subsequently cleared via the mucociliary escalator [7,8,9]. In addition, particle exposure induces an inflammatory response, stimulating immune and structural airway cells to release cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, GM-CSF, and TNF-α [10,11,12]. Furthermore, they can participate in redox reactions that elicit inflammatory responses and can even enter the circulation system [13], causing consequences to the respiratory, cardiovascular, and nervous system [14]. For these reasons, the analysis of UFPs as a health-related parameter requires their variability patterns and quantitatively evaluating the relative contributions of their sources. The World Health Organization (WHO), in its latest update to the Global Air Quality Guidelines [1], has identified UFP as an emerging pollutant that needs further investigation. The European Ambient Air Quality Directive 2024/2881 specifies the importance of measuring UFPs at both rural and urban background sites. Epidemiological studies supported by reliable measurement data are needed to establish a foundation for future regulatory measures.

The formation of UFP is attributed to both direct emissions and the process of atmospheric new particle formation (NPF) [15,16,17]. NPF in cities is a significant source of UFP, and their amount is comparable to the directly emitted UFP [16]. Combustion is the dominant primary emission source in urban environments [18,19]. The subsequent rapid cooling of hot exhaust gases in the atmosphere leads to their nucleation and condensation, generating fresh particles typically under 50 nm in size [20]. Furthermore, these gaseous emissions contribute to secondary UFP production via NPF events, where they form condensable vapors capable of influencing regions hundreds of kilometers wide [15,21,22]. The relative contribution of NPF to total UFP number concentrations is generally limited, but it becomes considerable during midday, with reported contributions of up to 50% [23,24]. In general, particles are grouped by size into three categories or modes. The nucleation mode (10–25 nm) consists of freshly formed particles from photochemical processes or transportation exhaust. The Aitken mode (25–100 nm) is made up of particles from incomplete combustion. Finally, the accumulation mode (100–800 nm) contains aged particles that have undergone long-range transport. According to research on European particle size distributions from 2017 to 2019, Budapest, Leipzig, and Barcelona recorded the highest concentrations for the nucleation mode. Aitken mode concentrations were the highest in Marseille, indicating that the dominant source of pollution was traffic. Average concentrations of Accumulation mode particles were highest in Budapest at 2173 cm−3, possibly due to long-range transport. On the other hand, Zurich, Birmingham, and Helsinki showed the lowest values for all three modes [2].

To date, there has been a huge scientific interest in the source apportionment of particle number size distributions (PNSDs) presented in different studies [17,24,25,26,27,28]. Multivariate modeling is a key method for determining the contributions of different sources [29], and Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) [30] is one of the most widely used, well-established, and efficient techniques for investigating this phenomenon [31]. The commonly identified sources of UFP in the ambient air of urban environments include nucleation, various traffic-related sources (from fresh to aged emissions), domestic heating, regional secondary aerosols (both inorganic and organic), biomass burning, industrial emissions, dust, and unknown sources [27].

Photochemical nucleation drives NPF events, which are characterized by PNSD peaking at the smallest sizes, 10–30 nm, and O3 contributions [26]. NPF events are favored by high solar radiation and wind speed, low relative humidity, minimal pre-existing particle surface area (i.e., a low condensation sink), and sometimes by the presence of precursor gases such as SO2 [2]. Additionally, emissions from harbors and airports predominantly contribute to the particles in the nucleation mode [18,19]. Usually, in urban areas, studies on source apportionment of UFPs identify traffic as the dominant source [18,24,27,32,33,34], typically with more than 70% of the annual UFP emissions [27]. Fresh and urban vehicular traffic emissions were contributing to over 50% of total and even more (64–78%) to UFP concentrations in the study performed in Athens [24]. In campaigns in Australia and Spain, traffic was also a main source of UFP in the urban atmosphere, with contributions between 44 and 63% [32]. In the long-term study conducted in Rochester, trends in the source-specific PNCs were analyzed and related to the implementation of regulations and changes in emissions resulting from economic drivers. Additionally, there are two main traffic sources usually mentioned in the literature, with peaks around 30–35 nm usually referred to as gasoline, commonly ascribed to spark-ignition vehicles, and 60–80 nm, associated with diesel vehicle emissions [27,35,36]. However, in some studies, a factor named traffic-related nucleated particles appears, which may originate from gasoline emissions and, more significantly, from semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs) escaping from diesel vehicle particulate filters (DPFs) [37,38]. These particles tend to grow quickly as they move away from the traffic source, so at urban background sites, traffic particles are generally larger than those found closer to traffic sources. This growth results from coagulation and the evaporation-driven loss of the delayed nucleated diesel traffic mode as the particles disperse into cleaner air [39,40]. It is important to recognize that where nucleated particle splitting methods are used, there may be greater uncertainty in estimating source contributions. Moreover, the traffic source category may include particles from less significant sources and be influenced by factors such as the distance from monitoring sites to major roads or unique local climate and meteorological conditions. Biomass burning and other human activities (e.g., industry) also produce a significant number of UFP [41]. In addition, there is typically a mode above 100 nm, which has been ascribed to the secondary inorganic particles [27]. If the factor has its maximum contribution in winter, it is typically labeled as secondary nitrate, whereas in summer, it is called secondary sulfate. Some reports [42] have observed both sulfate and nitrate in the transition season. Furthermore, other sources contribute to urban UFP concentrations, such as urban background (which is heavily influenced by traffic), domestic heating, regional background, and long-range transport, which typically emit particles with modes near or larger than 100 nm.

This study represents the first source apportionment analysis of UFP conducted in Belgrade. While similar studies have been extensively performed across Western, Central, and Northern Europe, there remains a significant lack of research addressing UFP concentrations and sources in Eastern European urban environments. Our work, therefore, fills an important regional gap, providing new insights into the origins and behavior of UFPs in this underrepresented area. We aim to quantitatively assess the impact of aerosol sources and formation processes on particle number concentrations (PNCs) at an urban background (UB) supersite in Belgrade, Serbia, at Ada Marina, using PMF receptor modeling on continuously monitored PNSD data (period of February–August 2024).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Monitoring Site

The site is located along the Sava River and bordered by extensive green spaces. It presents the largest recreational area in the central area of Belgrade city (Figure 1). The nearest potential pollution sources include numerous restaurants in the vicinity and a high-traffic arterial road, approximately 0.25 km away. There are other local emission sources: to the West, a natural gas residential heating plant (1.5 km), in the Northwest, one of the most busiest airport in the Balkan Peninsula (~10 km), and, to the East, pollution from the Vinča municipal landfill and road traffic associated with the Belgrade’s 1.7 million citizens, where there are more than 0.7 million restarted vehicles.

Figure 1.

Ada Marina monitoring site. The wider region of the city of Belgrade with points of interest can be observed on the left. The immediate surroundings of the monitoring site are shown on the right.

In addition, the international E-70 highway passes through Belgrade. However, it now primarily serves local transport, as the new bypass encircles the city to handle transit road traffic. Potential air pollution sources also include numerous smaller production plants and processing and storage facilities. Southwest of the Ada Marina is the coal-fired thermal power plant “Nikola Tesla” (~25 km), and further beyond are located mining basins and another coal-fired thermal power plant near Lazarevac. Furthermore, outside the city are areas of agricultural activity. In the wider region, additional sources may affect Belgrade’s air quality, such as the Smederevo ferreous smelter (~30 km to the East) and the Kostolac coal-fired thermal power plant (~50 km).

2.2. Instrumentation and Measurements

Ambient particle data were collected using a Mobility Particle Size Spectrometer (MPSS), optimized for capturing high-resolution PNSDs in the submicron range. MPSS 3938 (TSI, Shoreview, MN, USA)was housed in a controlled environment to reduce contamination. The system was configured to record PNSDs at 90 s intervals, enabling detailed, time-resolved analysis of submicron particle concentrations. For real-time measurements of equivalent elemental carbon (eBC) and total carbon, an AE-33 Aethalometer and a TCA08 Real-Time Measurement of Total Carbon (Aerosol Magee Scientific, Ljubljana, Slovenia) were employed, providing data at 5 min and 30 min time resolutions, respectively. PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations were measured by the Grimm monitor EDM/180, while gaseous pollutants were detected with Teledyne API monitors for SO2, NO, NOx, NO2, and O3.

2.3. Data Processing

PMF [30] was applied to the PNCs dataset using the EPA PMF 5.0 receptor model to resolve and quantify major contributing sources. In addition to size-resolved PNC from the SMPS, we included co-located gaseous and particulate pollutants (O3, carbonaceous particles, SO2, PM10, PM2.5, NO2, NO, and NOx) measured at the same site that belongs to the local network of automatic monitoring stations in Belgrade. These additional parameters helped distinguish between sources and supported the interpretation of the factor profiles in terms of known emission types and atmospheric processes.

Proper treatment of uncertainty is essential for the PMF because the model minimizes a weighted least-squares objective function in which each residual is normalized by its estimated uncertainty. For each size bin i and time step j, the measurement uncertainty was defined according to the method employed in other studies [34,42,43].

where αij = 0.01(nij + ), nij is the observed concentration, is its mean value, and C3 is a constant determined empirically by trial and error. This structure prevents unrealistically small uncertainties at low concentrations and scales the uncertainty with concentration at higher values. A similar method was applied to the non-SMPS species. Uncertainties of the measurements of main pollutants were provided by the Public Health Institute of Belgrade, which operated the local AQ monitoring network. Measurement uncertainties were estimated following the EPA PMF methodology as the quadratic sum of a relative analytical error and the method detection limit (MDL). For concentrations below the MDL, values were replaced by half of the MDL, and their uncertainties were set to five-sixths of the MDL, thereby down-weighting low-signal data without excluding them from the analysis [44]. The resulting uncertainty matrix was then supplied to EPA PMF 5.0 along with the concentration matrix.

To determine the appropriate dimensionality of the solution, we performed model runs using 5, 6, 7, and 8 factors. Each candidate solution was evaluated in terms of statistical performance (e.g., Qrobust to Qexp), interpretability of factor profiles, and temporal behavior such as diurnal patterns. Based on these criteria, we selected the 7-factor solution as the most meaningful. The selected run yielded Qrobust = 326,994 and Qexp = 326,943, giving Qrobust/Qexp = 1.00, which is indicative of a satisfactory solution in line with guidelines laid out by previous studies [45,46]. More than 95% of scaled residuals fell between −3 and +3 across the measured variables. R2 values for particle number size distribution were in the range between 0.85 and 0.99, indicating excellent reconstruction of ultrafine particle variability. For the co-measured gaseous and particulate species, R2 ranged from ~0.25 to 0.70, while ozone showed low R2, as expected for a secondary pollutant primarily governed by photochemical production rather than direct emission sources. We assessed the robustness of this solution using bootstrap analysis (to test the sensitivity of the resampling of the input data) and displacement analysis (to probe rotational ambiguity and factor stability). The bootstrap analysis (Supplementary Information, Table S1) shows strong and consistent mapping. Only a small 2% drift appeared on one of the factors, while the other ones had 100% perfect stability without cross-mapping. Additionally, none of the factors were left unmapped, which further strengthens the seven-factor hypothesis. The displacement (DISP) analysis (Supplementary Information, Figure S1) indicates that the seven-factor solution is generally well constrained, with most factors showing tight uncertainty ranges and base profiles that remain centered within the bootstrap distributions. Minor variability appears in a few size ranges—most noticeably for the factors related to biomass burning—but the overall shapes remain consistent, and no factor shows signs of significant rotational ambiguity or alternative competing solutions. Overall, the DISP results confirm that the factor profiles are stable, and the seven-factor model is robust.

Finally, we evaluated the physical plausibility of the resolved PMF factors using tools from the openair (version 2.18-2), R package (version 4.4.2). At the campaign site, in addition to the main pollutants, meteorological parameters such as wind speed and wind direction are measured as well. During the measurement period, winds from the South–Southeast sector were, on average, the most frequent.

By combining PMF factor contributions with local meteorological data, we examined the directional dependence and temporal behavior of each factor using established diagnostic plots, such as bivariate polar plots and diurnal variation analyses. This approach allowed us to assess whether the identified factors exhibited physically meaningful relationships with wind direction, wind speed, and typical daily activity patterns. The consistency between factor contributions, prevailing wind sectors, and expected diurnal trends provided an independent qualitative validation of the PMF solution, supporting the interpretation that the resolved factors represent realistic local and transported sources influencing the monitoring site.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Basic Statistics

Table 1 presents a summary of the basic statistics of meteorological data and pollutants in our measurement campaign. The average temperature was 19.25° and the relative humidity 62.08%. We analyzed concentrations of UFP and PNC, and the contribution of UFP to PNC. Overall daily average PNCs for total particles were 10,525.16 cm−3, N100–400 was 1849.03 cm−3, N10-100 (UFP) was 8945.8 cm−3 and N10-25 was 2925.29 cm−3. The results are in the same range as in the cities in the region, with median values as follows: N10-400 was 7482.57 cm−3 in Belgrade, N10–500 were 8889 cm−3 in Budapest, 5395 cm−3 in Vienna, and 5844 cm−3 in Prague [16]. The contribution ratio of UFPs to the PNC, expressed as N10–100/N10–400 = 0.80, was obtained at the site in Belgrade during our campaign, while similar ratios expressed as N10–100/N10–500 were 0.71 in Budapest, 0.73 in Vienna, and 0.78 in Prague [16], during a two-year campaign. Our campaign duration was 6 months, 2 months during the heating season and 4 months during the non-heating season.

Table 1.

Observed PNC values at the Ada Marina site in Belgrade (in #/cm3) and a summary of other pollutants and meteorological data.

3.2. Source Apportionment Results

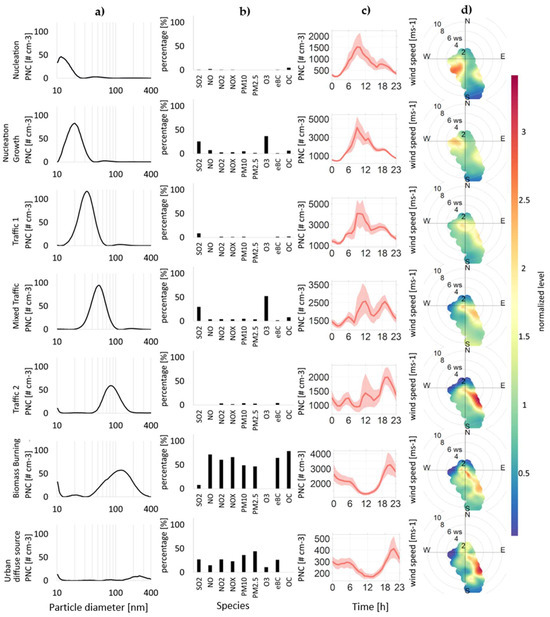

The factor distribution obtained with the PMF analysis agrees well with those reported in the literature and is discussed together with our measurements and conditions (analysis results are presented at Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4). Figure 3 presents, for each factor, the PNSD, relative contributions of co-pollutants, daily variations in PNC, and the corresponding polar wind plots. Time series data of each source is given in Supplementary Information at Figure S2.

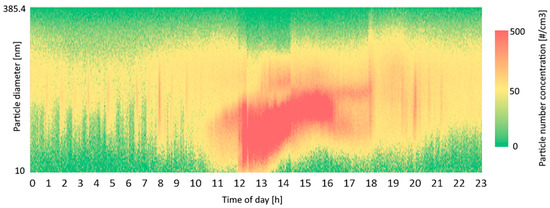

Figure 2.

PNCs for 3 March 2024. An NPF event can be observed at 12 PM.

Figure 3.

Source appointment at the Ada Marina site. The factors are listed in rows, while the (a) column represents particle number concentration distributions ([#cm−3/nm], the (b) column represents contributions of chemical components [% of total], (c) column is the daily variation in particle number concentration [#cm−3/h] (red lines are averaged concentrations and red background are confidence intervals of concentrations), and (d) column is polar wind plots with normalized concentrations.

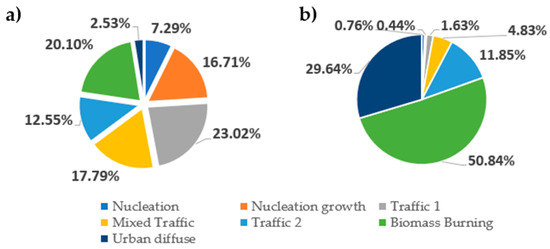

Figure 4.

Pie graphs: (a) average particle number contribution of each factor and (b) average factor mass contribution of each factor.

3.2.1. Factor 1: Nucleation

This factor is associated with the smallest particles and is characterized by a single mode in the source profile with a diameter ranging from 10 to 25 nm [17,24], peaking in our analysis at 11.8 nm (Figure 3). The maximum contributions from this factor occurred around noon, coinciding with the solar radiation peak. This source was associated with photochemically induced NPF events, which are enhanced by high insolation [32,40]. Generally, a high frequency of NPF events was observed during the campaign. Figure 2 shows an example of increased concentrations of nucleation mode particles due to the NPF. The decrease in nucleation mode particle concentrations in the subsequent hours, together with the shape of the banana plot, indicates that agglomeration and coagulation are the dominant processes during midday. Smaller peaks during traffic rush hours in the morning and evening are visible, meaning that the source may include nucleation mode particles from the traffic exhaust. The wind directions indicate that the main contributions to this factor are coming from the North–West and the South–East. While the source in the South–East likely comes from traffic-related sources, the contributions from the North–West could potentially be related to the local airport. This factor contributes only 7.29% to the total PNC and less than 1% to the total mass, as the particle diameters are very small (Figure 4).

3.2.2. Factor 2: Nucleation Growth

This factor, which is associated with nucleation growth and the formation of new particles, is rich in SO2 and O3. It was observed in the 10–40 nm size range, peaking at 20.2 nm (Figure 3). It is linked to periods of intense solar radiation and high O3 concentrations, peaking at midday, similar to the previous factor, which indicates the evolution of particles generated by NPF events (Figure 2) [47]. The second stage of particle growth is characterized by the PNSD maximum shifting to larger sizes than in the first nucleation stage [48]. Wind directions indicate that the main contributions to this factor originate from the Northwest and Southeast, further confirming its connection to the previous factor. This factor accounts for 16.71% to the total PNC, and less than 1% in mass concentration, as the particle diameters, volumes, and masses are very small (Figure 4).

3.2.3. Factor 3: Traffic 1

The first traffic factor has a maximum at 32.2 nm in our analysis (Figure 3) and is commonly ascribed to spark-ignition (gasoline) vehicles, with the major size modes having peaks ranging from 23 to 39 nm [17]. There are also suggestions that these small-diameter particles, up to 40 nm, are also called fresh traffic particles [18]. They may present fresher traffic emissions of core carbon particles with organic compounds condensed and absorbed. These traffic nucleated particles can come from SVOCs, and they tend to grow quickly, moving away from the traffic source, during exhaust dilution and cooling. This mode is even enhanced when diesel fuel has a high sulfur content [37,49,50]. As shown in Figure 3, the diurnal pattern of this factor is observed at two rush hour peaks of lower concentrations and one midday peak with higher concentrations that could suggest further evolution of nucleation-generated particles [27,34,36]. Additionally, some contributions of SO2 can be noticed. Figure 4 shows that the distribution of this factor according to particle number is 23% and according to mass distribution is 1.63%, owing to the small dimensions of the particles. This makes it the highest contributing factor in terms of particle number concentrations.

3.2.4. Factor 4: Mixed Traffic

This source is characterized by a major size mode peak at 51.4 nm, falling into a highly traffic-influenced urban background (Figure 3). It has large contributions of O3 and SO2. This factor was also predominant at low wind speeds. In the literature, this source is characterized by peaks in the range 43–55 nm, which is the range between Traffic 1 and Traffic 2. It represents a highly traffic-influenced urban background; thus, it is mixed with other sources, maintaining the daily, seasonal, and weekly patterns of traffic sources [17]. The wind direction indicates that the particles come from the main road Southeast of the measurement location. Higher concentrations of SO2 are probably due to the proximity to the river, boat routes, or nearby industries [18]. This factor accounted for 17.79% and 4.83% of the observed number of particles and particle masses, respectively (Figure 4).

3.2.5. Factor 5: Traffic 2

Particles of this source are found in the 55–119 nm region [17], with the largest concentration being found at 82 nm in our analysis (Figure 3). These particles are associated with diesel vehicle emissions [51]. In our case, there were small contributions of NO2, NOx, PM2.5, and PM10. There are also suggestions that this factor appears due to aged road traffic, which is explained by the coagulation of particles moving from sources. This factor is also characterized by increased concentrations of NO2 and PM10 [17,19]. When it comes to wind direction in our analysis, this factor’s pollutants also come from the high-traffic road from the Southeast. Figure 4 displays that this factor accounts for 12.55% of the total PNCs, and in mass it is similar at 11.85%.

3.2.6. Factor 6: Biomass Burning

The particles that constitute this factor can be found in the entire observed particle diameter spectrum and are related to domestic heating. Some of the reported modes were 70–110 nm in the cold period [24]. In our analysis, a distinct maximum was observed at 126.3 nm, though a smaller peak exists as well at 20.9 nm (Figure 3). The diurnal pattern shows increased concentration during the night. This factor contains substantial amounts of organic matter, nitrates, and sulfates. Most of them are found appearing in “small” mode, which has been linked to primary combustion emissions [19]. This factor has contributions from all gases as well as PM10 and PM2.5. Another footprint of this factor is the increased concentrations of carbonaceous particles. The use of biomass in heating has risen across the European Union by 57–111% from 2010 to 2020, as the 27 member states are committed to obtain 20% of their energy requirements from renewable sources, including biomass, to reduce CO2 emissions [52]. Approximately around 20% of particles come from this source, and they represent 51% of the total UFP mass emitted owing to the large particle dimensions (Figure 4).

3.2.7. Factor 7: Urban Diffuse Source

The urban diffuse factor is defined as a profile found in a broad region of accumulation mode particles, peaking at 250.3 nm in our analysis, and is associated with several air pollutants, including PM10 mass and combustion-related pollutants such as CO, SO2, NO, and NO2 [28,36]. Figure 3 shows a very broad and small peak near the end of the range and another peak, which includes a small portion of small particles at the beginning of the range. The wind directions indicate the main contributions from the high traffic road from the Southeast. It displayed an early-morning peak and an evening peak. The presence of an urban diffuse source could be explained by the formation of secondary particles. Gaseous precursors from vehicle exhaust, once diluted and oxidized in the atmosphere, form new particles. From polar plot diagrams, the contribution to this factor is also visible from North, that is, the location of New Belgrade, a modern residential and business part of the city and the airport; Southwest, where it is a strong city center with dense traffic; South, the coal-fired thermal power plant. These particles subsequently increase in size through condensation and coagulation processes. Figure 4 shows that this factor has a very low contribution to particle number distribution, 2.53%, but in mass it is nearly 30%, as these particles have larger diameter sizes.

3.2.8. Contributions of Factors to Total Particle Concentration

Figure 4 presents the contribution of each factor to total particle concentration, in number (left) and in mass (right). The results indicate dominant number concentrations of sources related to traffic, in total over 40%. Biomass burning is the dominant source of mass contributions. This is expected as these particles are larger in diameter and mass. Traffic particles can be classified as diesel- or gasoline-related, fresh or aged particles, and they do not include only engine exhaust emissions but also particles originating from the road–tire interface. These particles can span a wide range of diameters, with sizes of 15–50 nm having been reported [53], as well as particles up to 100 nm during braking or acceleration events [54,55].

3.3. Comparison of Quantitative Factor Contributions in Different Cities

In some studies, a general nucleation factor (with the particle diameter < 25 nm) was further split into photonucleation and traffic-nucleation factors [17], while in our study, we named it as nucleation (peaking at ~12 nm) and nucleation growth (peaking at~21 nm) factors, with contributions of 7% and 17%, respectively. Photonucleation is a significant contributor in several cities in Europe, mainly driven by NPF phenomena on regional scales. In the Barcelona urban background site, which experiences relatively high sunlight compared to other studied cities [8], this source accounts for 31% of the average PNC, with values notably higher in summer but remaining important throughout the whole year, mainly due to emissions of precursor gases from shipping. Both Dresden and Leipzig urban background sites also show considerable contributions from photonucleation—24% in Dresden, and 18% in Leipzig, which are higher values than the one we obtained in our study in the city of Belgrade. These contributions are likely linked to surface fumigation by higher-altitude atmospheric layers enriched with nucleation-mode particles formed via NPF during the planetary boundary-layer growth [56].

If we compare the traffic factor contributions from Figure 4 with the results obtained in Budapest [36], the results are almost the same, with nearly 55% of traffic sources in summer and spring periods. In the other source appointment study, results obtained at the urban background site in Budapest indicate a 58% contribution of traffic sources with the measurements in all seasons, similar to Madrid and Zurich, while in the city of Athens, it is around 47%. The sum of all the traffic contributions in this study (traffic 1, traffic 2, mixed traffic, and traffic-nucleation) represents 70–88% of the average PNC at 9 out of the 14 cities that participated in this study [17]. Accordingly, the results indicate that road traffic is the major contributor to UFP/PNC around Europe. Traffic emissions have been widely documented in the literature as a major source contributing to the total particle number size distribution (PNSD) in numerous urban areas globally [17,22,24,42].

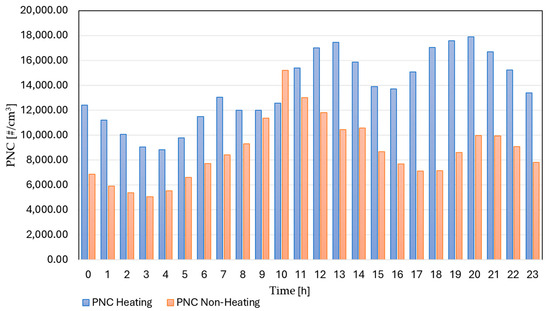

3.4. Seasonal Variability of Particle Number Concentration

Figure 5 compares the average hourly PNC for the heating and non-heating seasons. The heating season officially starts on 15 October and ends on 15 April. As expected, PNC levels were higher in the heating season, reaching a maximum of 17,908.5 cm−3, with higher values in the afternoon and evening. In the non-heating season, the maximum concentration is 15,214.2 cm−3, between 9:00 and 13:00. The morning and evening maxima can be attributed to rush-hour traffic emissions. The increased concentrations observed at noon are likely related to solar radiation–enabled photonucleation and the resulting particle growth. Other studies have also evaluated seasonal variations, and the results indicate lower PNC in summer and higher concentrations in winter. For example, in the city of Canoas, Brazil, traffic is a major source of UFP, and the PNC revealed higher concentrations, ranging from 20,245 to 21,945 #/cm3, in winter (08:00 to 12:00 h) during traffic rush hours, and at night [57]. In the city of Athens, the study was conducted in three periods: warm, cold, and lockdown periods. Traffic and biomass burning produced high UFP number concentrations in the cold period (+107% compared to summer), and the lockdown restrictions reduced the number of UFP (−42%). Interesting results were obtained by comparing two winter periods: usual and lockdown. A high lockdown reduction of 46% was observed for fresh traffic contributions to the total number concentration, indicating the importance of traffic sources in the wintertime [24]. Additionally, in the city of Thessaloniki, which is 630 km away from Belgrade, domestic heating was determined to be the dominant reason for increased concentrations of particles in the wintertime [58].

Figure 5.

Average hourly PNC in heating and non-heating seasons.

The seasonal variation may be due to the formation of new particles, which are enhanced by the mixing of air parcels with large temperature and relative humidity differences [59] and poorer mixing (less dilution) in winter. During the day, the turbulent, expanding planetary boundary layer disperses particles evenly. At night, as the mixing layer collapses, a stable boundary layer forms, and particles rapidly accumulate near the surface and decrease sharply with height. In addition, research indicates that particles, especially those that absorb sunlight, play a significant role in forming near-surface temperature inversions. This is supported by data showing that inversions become more common as total particle levels rise, but less common as particles become more reflective (less absorbent) [60]. Another usual source of pollution during the winter months is biomass burning coming from domestic heating. The distribution according to particle diameter (Figure S3, in Supplementary Information) indicates that the highest concentration difference between seasons lies in the diameter range 20–80 nm, which are Aitken mode particles. Thus, it is indicative that reasons for higher levels of particles in the heating season can be different; one of them is the low thickness of the boundary layer at night in winter, another one is biomass burning, with possible contributions from traffic sources as well.

4. Conclusions

UFPs and larger accumulation mode particles up to 400 nm, together with online measurements of the main pollutants and carbonaceous particles, were used to investigate the contribution of sources in the city of Belgrade (Serbia) in the period of February to August 2024. The sources were established using PMF of PNSD along with eBC and OC, as well as PM10, PM2.5, O3, SO2, NO, NO2, and NOx. Seven sources were distinguished, which can be divided into two traffic sources, a mixed traffic source, an urban diffuse source, a nucleation and nucleation growth source, and biomass burning.

It seems likely that the two types of traffic sources express emissions from gasoline and diesel motor vehicles. All three traffic sources exhibited similar patterns, confirming the fact that they are related. With the analysis of the wind profiles, it was again confirmed that most of the contributions seemed to arrive from the highway located to the South–East, relative to the measurement site. The analysis of banana plots of some of the daily profiles confirmed that the nucleation and subsequent aggregation and growth of these particles significantly contributed to the concentration of UFPs. Thus, two of the factors—nucleation and nucleation growth, are related to the phenomena of NPF. The diurnal patterns of these factors have a significant influence of solar radiation that peaks at noon, and with the co-occurrence of O3 and SO2, which are precursors of NPF, further indicate nucleation sources. The biomass burning source was confirmed to have characteristic particle diameters as well as the observed chemical species. The urban diffuse source factor showed similar patterns to both biomasses burning (in terms of gaseous species and diurnal profile) and traffic-related sources (similar wind profiles).

The results showed that traffic sources are the main contributors to the concentration of UFPs and are responsible for over 40% of total emissions. Nucleation-related sources contributed 24% of the total PNC, and biomass burning contributed 20% to PNC, with increased levels of particles during the heating season. This study features a comprehensive analysis that combined several months of data from several different sampling devices, including wind data, in order to evaluate the main pollutants and contributors of ultrafine particles. The results obtained could suggest a further course of action for the development of possible future mitigation measures and strategies in the city of Belgrade. Source apportionment, combining particle size and chemical composition data, shows that regulating traffic and other residential emissions could significantly reduce ultrafine particle levels, offering major benefits for public health.

Applying receptor modeling to long-term particle number size distribution data can yield valuable quantitative insights. In future research, we aim to conduct longer measurement campaigns, with a minimum duration of one year, or to establish a supersite with permanent monitoring of fine particles and UFP number size distributions. In addition, we plan to perform shorter campaigns at several different locations across the city to monitor fine and UFP particle number-size distributions, thereby providing a deeper understanding of the identified source factors.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/environments13010047/s1, Figure S1: Displacement analysis; Figure S2: Time series for all factors; Figure S3: Distribution of particle concentrations according to particle diameter in heating and non-heating seasons; Table S1: Bootstrap analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B.S.; methodology, Ž.Ć. and M.D.; software, Ž.Ć.; validation, D.B.S., M.G.-M., A.A. and M.J.-S.; formal analysis, Ž.Ć., D.B.S., M.D. and M.J.-S.; investigation, Ž.Ć., D.B.S., M.G.-M., N.P.L., A.A. and M.J.-S.; resources, M.J.-S. and A.A.; data curation, Ž.Ć.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B.S. and Ž.Ć.; writing—review and editing D.B.S., Ž.Ć., A.O., M.G.-M., A.A. and M.J.-S.; visualization, Ž.Ć. and D.B.S.; supervision, M.J.-S., A.O. and A.A.; project administration, M.J.-S.; funding acquisition, M.J.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Program under GA 101060170 (WeBaSOOP project) and the Ministry of Science, Technological Development, and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia under GA 451-03-136/2025-03/200017.

Data Availability Statement

All data on particle number size distribution are openly available at https://ebas.nilu.no/ (accessed on 29 July 2025) and https://doi.org/10.48597/CQF2-YGGJ.

Acknowledgments

For participation in data collection, the authors acknowledge the team from Vinca Institute, which participated in the WeBaSOOP campaign, and the WeBaSOOP team from the Public Health Institute of Belgrade for their logistical support and valuable contributions before and during the experimental campaign. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used DeepSeek V3-2 and ChatGPT 5.2 tools for the purposes of language editing support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Trechera, P.; Garcia-Marlès, M.; Liu, X.; Reche, C.; Pérez, N.; Savadkoohi, M.; Beddows, D.; Salma, I.; Vörösmarty, M.; Casans, A.; et al. Phenomenology of Ultrafine Particle Concentrations and Size Distribution across Urban Europe. Environ. Int. 2023, 172, 107744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leikauf, G.D.; Kim, S.-H.; Jang, A.-S. Mechanisms of Ultrafine Particle-Induced Respiratory Health Effects. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberdorster, G. Lung Particle Overload: Implications for Occupational Exposures to Particles. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 1995, 21, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utell, M.J.; Frampton, M.W.; Zareba, W.; Devlin, R.B.; Cascio, W.E. Cardiovascular effects associated with air pollution: Potential mechanisms and methods of testing. Inhal. Toxicol. 2002, 14, 1231–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaques, P.A.; Kim, C.S. Measurement of Total Lung Deposition of Inhaled Ultrafine Particles in Healthy Men and Women. Inhal. Toxicol. 2000, 12, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seagrave, J.; Campen, M.J.; McDonald, J.D.; Mauderly, J.L.; Rohr, A.C. Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Pulmonary Function Assessment in Rats Exposed to Laboratory-Generated Pollutant Mixtures. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2008, 71, 1352–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, C.; Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Xi, Z. Comparative Study of Cytotoxicity, Oxidative Stress and Genotoxicity Induced by Four Typical Nanomaterials: The Role of Particle Size, Shape and Composition. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2009, 29, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Qiongliang, L.; Yang, L.; Li, C.; Han, L.; Wilmot, J.; Yang, G.; Leinardi, R.; Zhou, Q.; Schröppel, A.; Kutschke, D.; et al. Alveolar macrophages initiate the spatially targeted recruitment of neutrophils after nanoparticle inhalation. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadx8586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yousaf, M.; Xu, J.; Ma, X. Ultrafine particles: Sources, toxicity, and deposition dynamics in the human respiratory tract——Experimental and computational approaches. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124458. [Google Scholar]

- Totlandsdal, A.I.; Cassee, F.R.; Schwarze, P.; Refsnes, M.; Låg, M. Diesel Exhaust Particles Induce CYP1A1 and Pro-Inflammatory Responses via Differential Pathways in Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2010, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsien, A.; Diaz-Sanchez, D.; Ma, J.; Saxon, A. The Organic Component of Diesel Exhaust Particles and Phenanthrene, a Major Polyaromatic Hydrocarbon Constituent, Enhances IgE Production by IgE-Secreting EBV-Transformed Human B Cells in Vitro. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1997, 142, 256–263. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.; Saffari, A.; Sioutas, C.; Forman, H.J.; Morgan, T.E.; Finch, C.E. Nanoscale Particulate Matter from Urban Traffic Rapidly Induces Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Olfactory Epithelium with Concomitant Effects on Brain. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 1537–1546. [Google Scholar]

- Samoli, E.; Andersen, Z.J.; Katsouyanni, K.; Hennig, F.; Kuhlbusch, T.A.J.; Bellander, T.; Cattani, G.; Cyrys, J.; Forastiere, F.; Jacquemin, B. Exposure to Ultrafine Particles and Respiratory Hospitalisations in Five European Cities. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 48, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salma, I.; Németh, Z.; Kerminen, V.-M.; Aalto, P.; Nieminen, T.; Weidinger, T.; Molnár, Á.; Imre, K.; Kulmala, M. Regional Effect on Urban Atmospheric Nucleation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 8715–8728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, Z.; Rosati, B.; Zíková, N.; Salma, I.; Bozó, L.; de España, C.D.; Schwarz, J.; Ždímal, V.; Wonaschütz, A. Comparison of Atmospheric New Particle Formation Events in Three Central European Cities. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 178, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Marlès, M.; Lara, R.; Reche, C.; Pérez, N.; Tobías, A.; Savadkoohi, M.; Beddows, D.; Salma, I.; Vörösmarty, M.; Weidinger, T.; et al. Source Apportionment of Ultrafine Particles in Urban Europe. Environ. Int. 2024, 194, 109149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, I.; Beddows, D.C.S.; Amato, F.; Green, D.C.; Järvi, L.; Hueglin, C.; Reche, C.; Timonen, H.; Fuller, G.W.; Niemi, J. V Source Apportionment of Particle Number Size Distribution in Urban Background and Traffic Stations in Four European Cities. Environ. Int. 2020, 135, 105345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacey, B.; Harrison, R.M.; Pope, F. Evaluation of Ultrafine Particle Concentrations and Size Distributions at London Heathrow Airport. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 222, 117148. [Google Scholar]

- Giechaskiel, B.; Maricq, M.; Ntziachristos, L.; Dardiotis, C.; Wang, X.; Axmann, H.; Bergmann, A.; Schindler, W. Review of Motor Vehicle Particulate Emissions Sampling and Measurement: From Smoke and Filter Mass to Particle Number. J. Aerosol Sci. 2014, 67, 48–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousiotis, D.; Dall’Osto, M.; Beddows, D.C.S.; Pope, F.D.; Harrison, R.M. Analysis of New Particle Formation (NPF) Events at Nearby Rural, Urban Background and Urban Roadside Sites. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 5679–5694. [Google Scholar]

- Kalkavouras, P.; BougiatiotI, A.; Hussein, T.; Kalivitis, N.; Stavroulas, I.; Michalopoulos, P.; Mihalopoulos, N. Regional New Particle Formation over the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Atmosphere 2020, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnerero, C.; Pérez, N.; Reche, C.; Ealo, M.; Titos, G.; Lee, H.-K.; Eun, H.-R.; Park, Y.-H.; Dada, L.; Paasonen, P. Vertical and Horizontal Distribution of Regional New Particle Formation Events in Madrid. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 16601–16618. [Google Scholar]

- Kalkavouras, P.; Grivas, G.; Stavroulas, I.; Petrinoli, K.; Bougiatioti, A.; Liakakou, E.; Gerasopoulos, E.; Mihalopoulos, N. Source Apportionment of Fine and Ultrafine Particle Number Concentrations in a Major City of the Eastern Mediterranean. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 170042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, T.V.; Delgado-Saborit, J.M.; Harrison, R.M. Review: Particle Number Size Distributions from Seven Major Sources and Implications for Source Apportionment Studies. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 122, 114–132. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Q.; Ding, J.; Song, C.; Liu, B.; Bi, X.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Hopke, P.K. Changes in Source Contributions to Particle Number Concentrations after the COVID-19 Outbreak: Insights from a Dispersion Normalized PMF. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 759, 143548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopke, P.K.; Feng, Y.; Dai, Q. Source Apportionment of Particle Number Concentrations: A Global Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 819, 153104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowell, A.; Brean, J.; Beddows, D.C.S.; Petäjä, T.; Vörösmarty, M.; Salma, I.; Niemi, J.V.; Manninen, H.E.; Van Pinxteren, D.; Tuch, T.; et al. Insights into the Sources of Ultrafine Particle Numbers at Six European Urban Sites Obtained by Investigating COVID-19 Lockdowns. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 9515–9531. [Google Scholar]

- Hopke, P.K. An Introduction to Receptor Modeling. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 1991, 10, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paatero, P.; Tapper, U. Positive Matrix Factorization: A Non-negative Factor Model with Optimal Utilization of Error Estimates of Data Values. Environmetrics 1994, 5, 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Hopke, P.K.; Dai, Q.; Li, L.; Feng, Y. Global Review of Recent Source Apportionments for Airborne Particulate Matter. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 740, 140091. [Google Scholar]

- Brines, M.; Dall’Osto, M.; Beddows, D.C.S.; Harrison, R.M.; Gómez-Moreno, F.; Núñez, L.; Artinano, B.; Costabile, F.; Gobbi, G.P.; Salimi, F. Traffic and Nucleation Events as Main Sources of Ultrafine Particles in High-Insolation Developed World Cities. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 5929–5945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddows, D.; Harrison, R.M. Receptor Modelling of Both Particle Composition and Size Distribution from a Background Site in London, UK–A Two-Step Approach. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 4863–4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopke, P.K.; Chen, Y.; Chalupa, D.C.; Rich, D.Q. Long Term Trends in Source Apportioned Particle Number Concentrations in Rochester NY. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 347, 123708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.R.; Hu, B.; Liu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.S. Source Apportionment of Urban Fine Particle Number Concentration during Summertime in Beijing. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 96, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vörösmarty, M.; Hopke, P.K.; Salma, I. Attribution of Aerosol Particle Number Size Distributions to Main Sources Using an 11-Year Urban Dataset. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 5695–5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.M.; Beddows, D.; Dall’Osto, M. PMF analysis of wide-range particle size spectra collected on a major highway. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 5522–5528. [Google Scholar]

- Damayanti, S.; Harrison, R.M.; Pope, F.; Beddows, D.C. Limited impact of diesel particle filters on road traffic emissions of ultrafine particles. Environ. Int. 2023, 174, 107888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Osto, M.; Thorpe, A.; Beddows, D.C.S.; Harrison, R.M.; Barlow, J.F.; Dunbar, T.; Williams, P.I.; Coe, H. Remarkable dynamics of nanoparticles in the urban atmosphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 6623–6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.M.; Jones, A.M.; Beddows, D.C.; Dall’Osto, M.; Nikolova, I. Evaporation of traffic-generated nanoparticles during advection from source. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 125, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni, C.; Pokorná, P.; Hovorka, J.; Masiol, M.; Topinka, J.; Zhao, Y.; Křůmal, K.; Cliff, S.; Mikuška, P.; Hopke, P.K. Source Apportionment of Aerosol Particles at a European Air Pollution Hot Spot Using Particle Number Size Distributions and Chemical Composition. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 234, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squizzato, S.; Masiol, M.; Emami, F.; Chalupa, D.C.; Utell, M.J.; Rich, D.Q.; Hopke, P.K. Long-Term Changes of Source Apportioned Particle Number Concentrations in a Metropolitan Area of the Northeastern United States. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogulei, D.; Hopke, P.K.; Chalupa, D.C.; Utell, M.J. Modeling Source Contributions to Submicron Particle Number Concentrations Measured in Rochester, New York. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paatero, P.; Hopke, P.K. Discarding or Downweighting High-Noise Variables in Factor Analytic Models. Anal. Chim. Acta 2003, 490, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, M.L.; Jeong, C.-H.; Slowik, J.G.; Chang, R.-W.; Corbin, J.C.; Lu, G.; Mihele, C.; Rehbein, P.J.G.; Sills, D.M.L.; Abbatt, J.P.D. Elucidating Determinants of Aerosol Composition through Particle-Type-Based Receptor Modeling. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 8133–8155. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). EPA Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) 5.0: Fundamentals and User Guide; Office of Research and Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rejano, F.; Casquero-Vera, J.A.; Lyamani, H.; Andrews, E.; Casans, A.; Perez-Ramirez, D.; Alados-Arboledas, L.; Titos, G.; Olmo, F.J. Impact of Urban Aerosols on the Cloud Condensation Activity Using a Clustering Model. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casquero-Vera, J.A.; Lyamani, H.; Dada, L.; Hakala, S.; Paasonen, P.; Román, R.; Fraile, R.; Petäjä, T.; Olmo-Reyes, F.J.; Alados-Arboledas, L. New Particle Formation at Urban and High-Altitude Remote Sites in the South-Eastern Iberian Peninsula. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 14253–14271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A.L.; Donahue, N.M.; Shrivastava, M.K.; Weitkamp, E.A.; Sage, A.M.; Grieshop, A.P.; Lane, T.E.; Pierce, J.R.; Pandis, S.N. Rethinking organic aerosols: Semivolatile emissions and photochemical aging. Science 2007, 315, 1259–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridolfo, S.; Querol, X.; Karanasiou, A.; Rodríguez-Luque, A.; Pérez, N.; Alastuey, A.; Jaén, C.; van Drooge, B.L.; Pandolfi, M.; Pedrero, M.; et al. Size distribution, sources and chemistry of ultrafine particles at Barcelona-El Prat Airport, Spain. Environ. Int. 2024, 193, 109057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Hinds, W.C.; Kim, S.; Shen, S.; Sioutas, C. Study of Ultrafine Particles near a Major Highway with Heavy-Duty Diesel Traffic. Atmos. Environ. 2002, 36, 4323–4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, F.; Amann, M.; Bertok, I.; Cofala, J.; Heyes, C.; Klimont, Z.; Rafaj, P.; Schöpp, W. Baseline Emission Projections and Further Cost-Effective Reductions of Air Pollution Impacts in Europe—A 2010 Perspective; IIASA: Laxenburg, Austria, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, A.; Gharibi, A.; Swietlicki, E.; Gudmundsson, A.; Bohgard, M.; Ljungman, A.; Blomqvist, G.; Gustafsson, M. Traffic-Generated Emissions of Ultrafine Particles from Pavement–Tire Interface. Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foitzik, M.-J.; Unrau, H.-J.; Gauterin, F.; Dörnhöfer, J.; Koch, T. Investigation of Ultra Fine Particulate Matter Emission of Rubber Tires. Wear 2018, 394, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fussell, J.C.; Franklin, M.; Green, D.C.; Gustafsson, M.; Harrison, R.M.; Hicks, W.; Kelly, F.J.; Kishta, F.; Miller, M.R.; Mudway, I.S. A Review of Road Traffic-Derived Non-Exhaust Particles: Emissions, Physicochemical Characteristics, Health Risks, and Mitigation Measures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 6813–6835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junkermann, W.; Vogel, B.; Bangert, M. Ultrafine particles over Germany–An aerial survey. Tellus B Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 2016, 68, 29250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo-Castañeda, D.M.; Teixeira, E.C.; Braga, M.; Rolim, S.B.A.; Silva, L.F.O.; Beddows, D.C.S.; Harrison, R.M.; Querol, X. Cluster Analysis of Urban Ultrafine Particles Size Distributions. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2019, 10, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vouitsis, I.; Amanatidis, S.; Ntziachristos, L.; Kelessis, A.; Petrakakis, M.; Stamos, I.; Mitsakis, E.; Samaras, Z. Daily and seasonal variation of traffic related aerosol pollution in Thessaloniki, Greece, during the financial crisis. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 122, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, P.; Beyrich, F.; Gryning, S.E.; Joffre, S.; Rasmussen, A.; Tercier, P. Review and intercomparison of operational methods for the determination of the mixing height. Atmos. Environ. 2000, 34, 1001–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, J.; Ding, A.; Liao, H.; Liu, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, T.; Xue, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, B. Aerosol and boundary-layer interactions and impact on air quality. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2017, 4, 810–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.