Abstract

In the global context of biodiversity loss, increased demand for natural resources, and major efforts to restore ecosystems altered by human activities, the widespread use of passive acoustic monitoring (PAM) and acoustic recording devices allows for the collection of enormous amounts of data for monitoring the health of ecosystems. BirdNET Analyzer is a freely accessible machine learning tool that has had a great impact on the scientific community due to its apparent ease of use for identifying animals by sound. However, the literature shows some gaps regarding the influence of certain BirdNET configuration parameters on the results of its predictions. This study applies PAM and uses BirdNET in a real acoustic monitoring project and analyzes the potential impact of the configuration parameters Overlap and Sensitivity on the results of the bird inventory of a wetland created on the site of a former limestone quarry in Spain. Our results guide other researchers in the optimal combination of configuration parameters at the community level. Higher Sensitivity configuration values provided the optimal solution for minimizing the loss of species in the bird inventory. On the other hand, we identified that Recall is the best indicator to identify all combinations of BirdNET configuration parameters that cause the lowest species loss, in line with the goal of this monitoring program.

1. Introduction

The loss of biodiversity on a global scale is an internationally recognized crisis that has increased dramatically in recent decades [1,2]. Changes in land and sea use, together with the direct exploitation of natural resources, are among the main factors causing the recent loss of biodiversity worldwide [3,4,5]. Among the various industries that exploit natural resources, the mining industry has experienced rapid growth in recent decades due to the increasing global demand for the various resources it provides [6]. In fact, mining is a fundamental source of raw materials for the manufacturing, transportation, construction, and energy sectors [7]. The world mining production has increased from 9.6 billion metric tons in 1984 to 19.2 billion in 2023 [8] and demand for raw materials is expected to continue to rise as the global population grows and many low-income economies become middle-income countries. For instance, concrete is the most consumed material after water in the world [9]. With growing concerns about sustainability, aggregates underpin modern society and are the most extracted material on Earth, constituting the most important component in terms of mass for most urban development and infrastructure projects [7]. On the other hand, the mining sector is also considered essential to enabling the green transition. However, mining processes can produce significant environmental impacts [10] even more so in the current context of the climate crisis [11].

Surface mining is a temporary and specific use of land that necessarily involves a major transformation of the land occupied [12]. In Europe, there are an estimated 26,000 aggregate extraction sites [13], and the sustainability of this activity depends, among other matters [10], on the restoration of the mined land to reduce the environmental impacts of the post-activity stage [14]. Companies are expected to restore these degraded areas and create new ecosystems, sometimes aimed at returning them to their pre-mining (natural) state [15]. On a continental scale, it is estimated that approximately 80% of Europe’s habitats are in poor or bad state, not only due to mining activities, and the European Union (EU) has recently adopted the Nature Restoration Law (NRL) to address its restoration from now to 2050 [16], and it includes mechanisms for monitoring and reporting progress [17]. The implementation of the NRL monitoring will represent a major effort by numerous stakeholders and states in an attempt to stop and reverse biodiversity losses [18]. Given that birds are a good candidate taxon for monitoring the health of many ecosystems [19,20], for instance, this regulation proposes using indices of their trends to assess biodiversity progress in certain habitats [21].

Among other monitoring techniques, passive acoustic monitoring (PAM) has proven effective for large-scale population surveys of acoustically active species, as well as for a single indicator taxon (birds), making it a valuable tool for monitoring threatened species [22] and, in particular, for monitoring in the field of ecological restoration [19,23,24]. In addition, PAM is considered a non-invasive method [25]. Acoustic recording units (ARUs) are increasingly used in long-term PAM due to the availability of open-source software and low-cost recorders that make it feasible to quickly collect and extract vocalizations of interest from large audio datasets [26,27].

Manual analysis of audio recordings by experts requires a time-consuming dedication, so automated analysis of recordings represents a solution that is under development but whose impact on the scientific community is increasingly evident in relation to biodiversity monitoring [28,29]. Among machine learning tools capable of identifying animals by sound, BirdNET Analyzer is a free bird sound recognizer that uses convolutional neural network algorithms to identify bird vocalizations in small segments (3 s) of longer audio recordings [30]. The current BirdNET Species Range Model V2.4 [31] has the capacity to identify >6000 bird species worldwide [32] and outputs provide a confidence score for each prediction ranging from 0 to 1, indicating the program’s degree of confident is that a species is present in the recording [33].

BirdNET has several tuning parameters that can be used to adjust key recognizer functions [33,34,35]. For instance:

- Overlap, is the number of seconds between extracted spectrograms and it can be configurated between 0.0 and 2.9 s (default value is 0.0).

- Sensitivity, is the detection sensitivity and can be set between 0.50 and 1.50 (the default value is 1.0) in Birdnet Analyzer v 2.3.0 and software versions before v 2.1.0. It can be set between 0.75 and 1.25 (the default is 1.0) in Birdnet Analyzer v 2.1.0, v 2.1.1, and v 2.2.0.

- Minimum confidence, adjusts the threshold to ignore results with confidence below. It can be configurated between 0.05 and 0.95 (default value is 0.25).

- Year round/Week, users can indicate whether the samples refer to the entire year or to a specific week. Although each month is considered to be 4 weeks long, so a value between 1 and 48 must be entered in case of the option “week”.

- Species List, there are different options to filter the species that are included in outputs. If the option “species by location” is selected, then the coordinates of the location must be specified.

- Location (latitude/longitude), coordinates of the recording location can be indicated, because these parameters are used for automatically generating species lists.

Effective PAM is not simply an act of collecting huge amounts of audio recordings, but it must be properly planned and analyzed to obtain high-quality information [29]. There is a growing trend in the literature on the need to guide other researchers in the optimal combination of configuration parameters when using new technologies for monitoring biodiversity, such as BirdNET [36]. In this regard, studies on BirdNET performance stand out for their applicability both for the ecological monitoring of bird species and for the characterization of bird communities [37]. For instance, Fairbairn et al. [38] has recently demonstrated that using appropriate parameter settings and undertaking some basic validation, BirdNET can yield results comparable to experts without the need for time-consuming estimation of species-specific thresholds. This represents a significant advancement in the study of the influence of other BirdNET configuration parameters according to the objectives of each case study. (e.g., Overlap and Sensitivity).

Among other challenges highlighted in the literature on the use of BirdNET are its limited use in monitoring birds in real-world conditions [1,30] and the lack of information on the effect of Sensitivity and Overlap parameters on BirdNET performance [24,39,40,41]. In fact, due to the aforementioned scarcity of studies dealing with this matter, some authors choose to use this justification to employ the software’s standard parameters [42]. However, default BirdNET parameter settings may perform poorly [38].

So, the main objective of this study is to evaluate BirdNET performance considering different configurations of the Overlap and Sensitivity parameters, applied to bird monitoring during 3 years as part of a broader ongoing monitoring program on the ecological restoration of a former limestone quarry located in central Spain. In addition, we also conducted a literature review on the use of BirdNET and the level of detail and justification provided in the scientific literature on these configuration parameters.

2. Background Information on Using BirdNET and Configuring Sensitivity and Overlap Parameters

2.1. State of the Art in BirdNET Configuration Parameters (A Literature Review)

For this section of the literature review, Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus were used because they are considered the two most comprehensive and influential bibliographic databases for various purposes [43]. The literature review was conducted between July and October 2025 and was based on the use of matching search terms and tools in WoS and Scopus. As an initial criterion for searching for publications on the use of BirdNET, all works indexed in either of the two databases (WoS Core Collection and Scopus) that included the word “BirdNET” in their title or abstract were searched. The initial results were then filtered by document type (only “Article”) and, among these, the search was also restricted to those published in “English” language. Finally, reading the articles collected allowed us to refine the results and eliminate some articles in which the term “birdnet” was used in a context completely different from that of our work. For example, the word “birdnet” was found in some works related to the use of LiDAR [44,45]. An article about the BirdNET App, a free bird sound identification app for Android and iOS [46], was also excluded from the analysis, as it does not correspond to the tool evaluated in our work (BirdNET Analyzer for scientific audio data processing).

2.2. Undefined Configuration Settings of the Parameters Overlap and Sensitivity

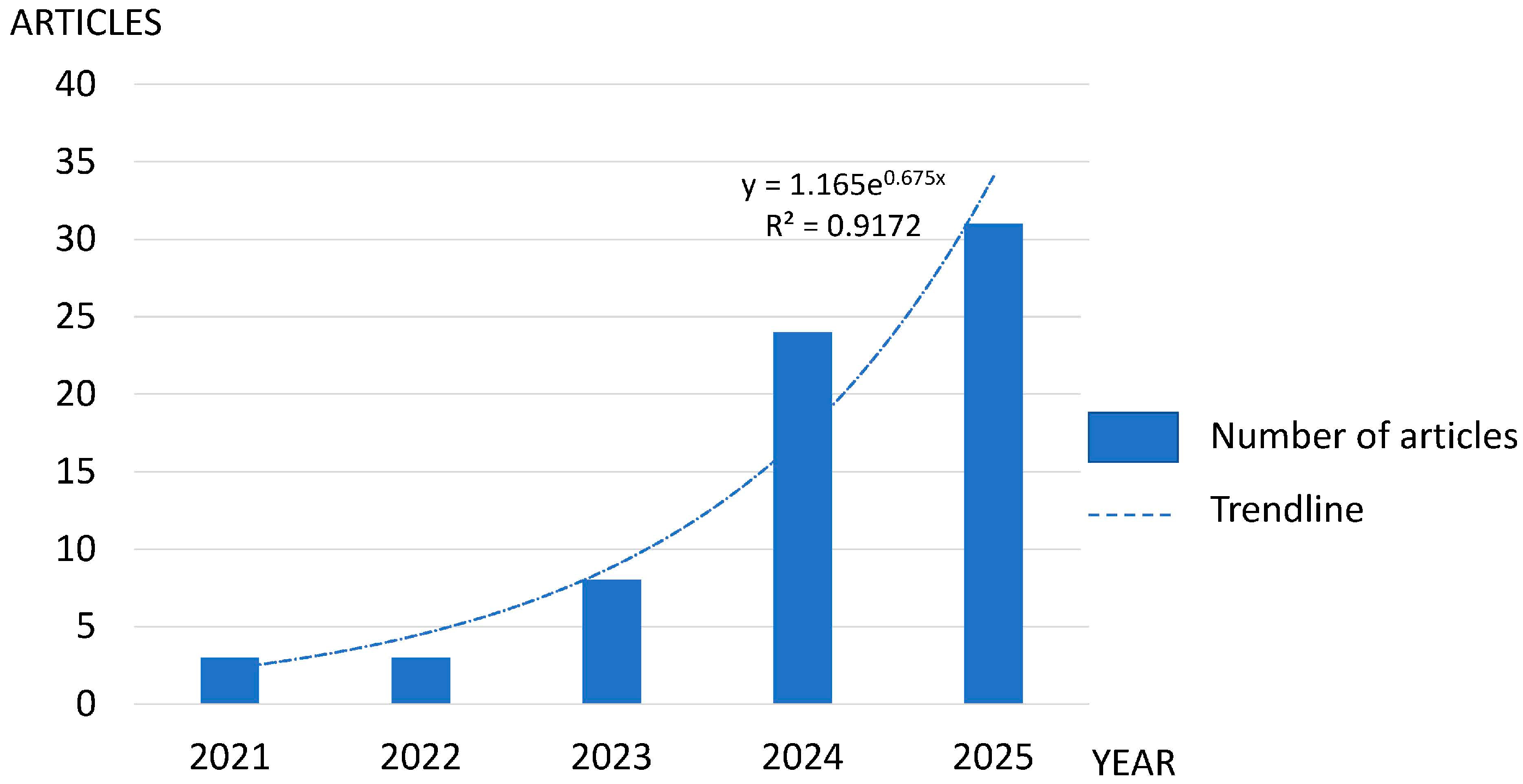

Based on the bibliographic search criteria explained above, a total of 79 publications were found in WoS and 91 in Scopus that included the word “BirdNET” in their title or abstract. Restricting the initial search results to “Article” publications reduced these numbers to 71 in WoS and 70 in Scopus. When selecting only English-language articles, there were 71 studies from WoS and 67 from Scopus. After that, duplicate works were eliminated from the results of the search in both databases, leaving 72 unique articles in English that included the word “BirdNET” in their title or abstract. Finally, reading these articles revealed that three of them were unrelated to the tool being analyzed in our study. Thus, 69 articles (Table S2) were ultimately considered for the review. All the selected articles were published between 2021 and 2025. Among the most relevant results of the bibliometric analysis, it is worth highlighting that the number of articles published each year on the use of BirdNET in international, English-language journals indexed in WoS and Scopus shows exponential growth (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of articles published per year in the databases consulted that include the word BirdNET in their title or abstract.

Regarding the analysis of the consideration of the overlap and/or sensitivity configuration parameters, most of the papers reviewed maintain the default BirdNET configuration. We have found that 81.1% of the 69 articles reviewed (56 out of 69) include some mention of Overlap, although only 36 of them (64.2%) mention this term in relation to BirdNET configuration parameters.

Other uses of the words “overlap” and “sensitivity” in studies using BirdNET often relate to details unrelated to the software configuration. For example, when talking about overlapping between acoustic signals (whether between different regions of the sound spectrum or between segments of different lengths of the same audio sample, or between territories of different species or individuals). As well as the sensitivity of different tools (for example, referring to microphones or statistical analysis techniques).

Returning to the analysis of the overlap parameter in the selected publications, only 14 articles (25%) justify the Overlap value they use, and only 9 studies (13%) adopt a value other than the default value set by BirdNET (Table S2). In 2 articles, the configuration of the overlap parameter is related to evaluating the effects on BirdNET predictions. In three articles, the value adopted is 1 s, in two articles it is 1.5 s, and in one article it is 2.9 s. The main reasons given for these changes to the default configuration are:

- The authors are interested in the highest resolution possible;

- To increase the number of detections and the probability of correct detections;

- To better fit shorter vocalizations.

However, in some cases, it has been observed that the default values are modified without apparent justification.

The term Sensitivity is mentioned at a lower frequency compared to Overlap, specifically in 49 papers (71.1%). However, only half of the articles reviewed, 35 articles (50.7%), use this term in relation to the BirdNET configuration. In this case, only 10 articles (14.5%) justify the value of the Sensitivity parameter used in their case, and only 7 studies (10%) adopt a Sensitivity value different from the default value established by BirdNET (Table S2). Only 4 of the 69 studies reviewed (i.e., 5.8%) do not adopt the default value for both parameters, and in these 4 cases, they include their justification.

Among the seven published studies that modify the default Sensitivity value, four articles evaluate the effectiveness of the results by testing different combinations of the Sensitivity value (only two of these studies also test different combinations of the Overlap parameter) (Table S2), and three articles adopt values of 1.4 or 1.5. Among the most commonly used arguments for modifying the default sensitivity setting are:

- A high sensitivity performs better in acoustically dense environments;

- As an effort to improve the BirdNET detection rate;

- A higher sensitivity allows us to capture more distant signals.

However, authors who increase the Sensitivity value are aware that this decision also increases the number of false positive detections.

Despite the small percentage of studies in which the configuration of the Overlap and Sensitivity parameters is justified, our results could be interpreted as conservative in favor of considering the influence of the Overlap and Sensitivity parameters in the literature. Given that, for example, it has been considered that the authors demonstrate that they take into account the possible influence of these parameters when they provide other details about the configuration of BirdNET, such as the particularization of the species list to identify a small number of them (usually between 1 and 4 species in these cases) to avoid classifying sounds of non-target species. Given that higher values of these parameters result in a greater expected number of bird identifications and vocalizations by BirdNET [28], although their configuration was not fully explained in the text, it can be interpreted that the authors were seeking an alternative to reduce this possibility.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

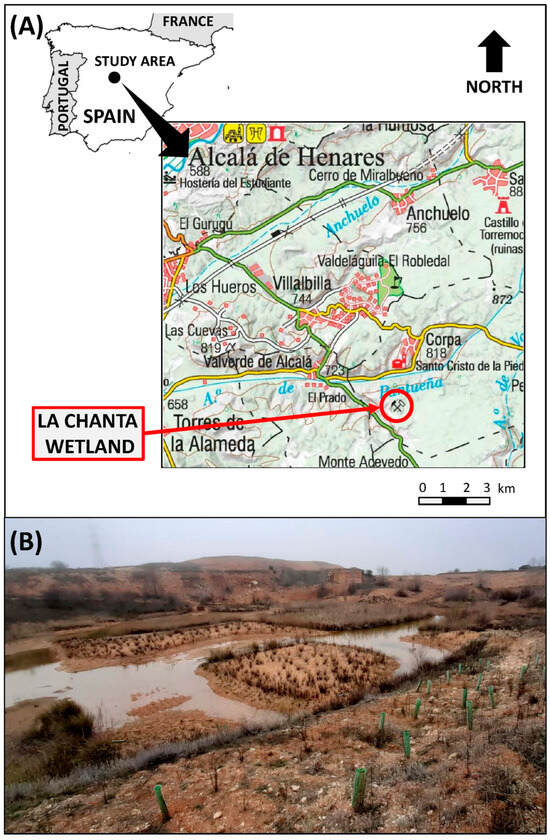

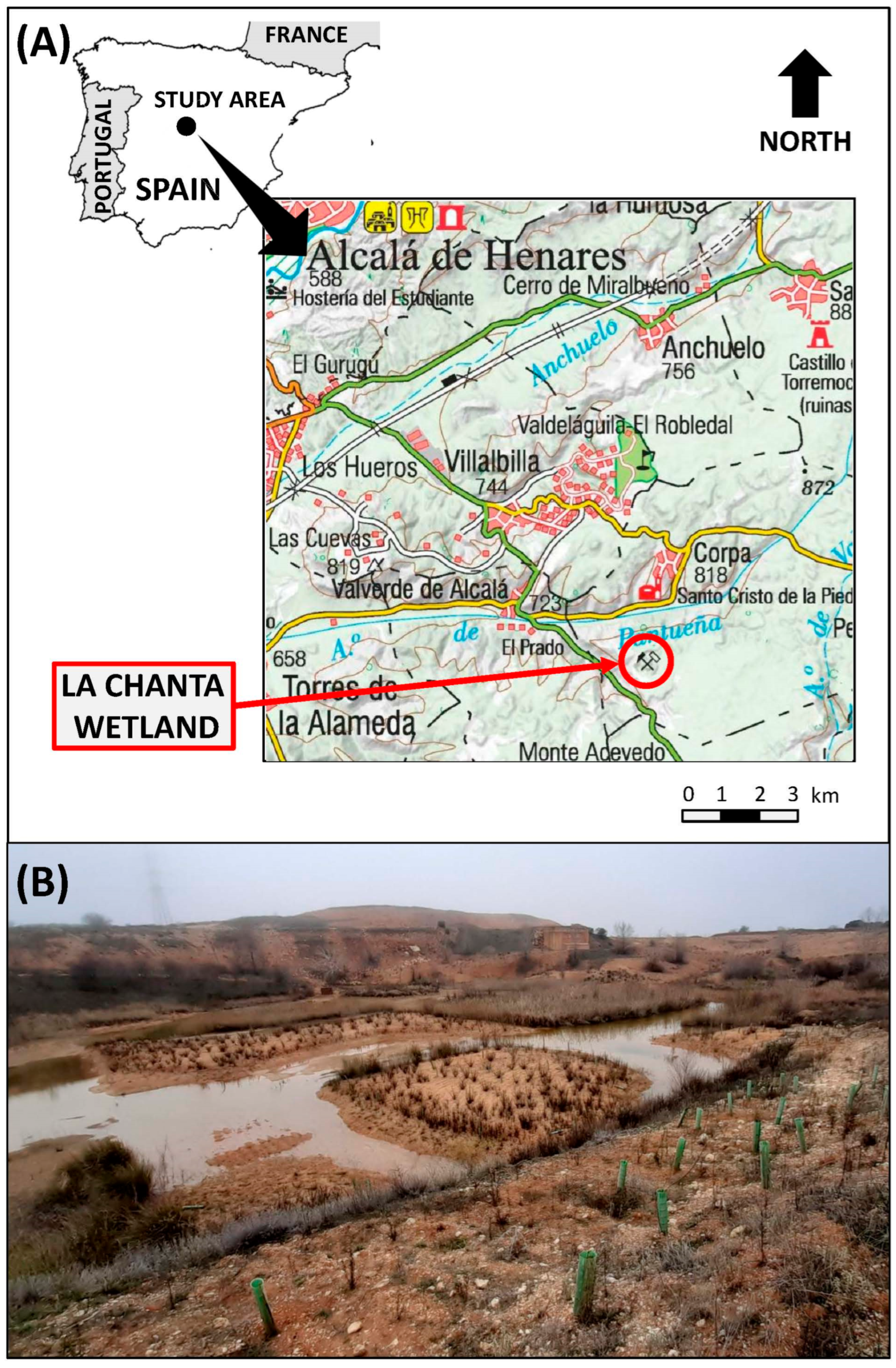

We conducted fieldwork within La Chanta wetland, located in the municipality of Corpa (Autonomous Community of Madrid) in central Spain (40°24′30.6″ N 3°16′12.0″ W) (Figure 2). The reserve covers 20 ha, of which 1.5 ha are occupied by the main wetland which is a temporary pond. Vegetation at the study area is primarily marsh vegetation, composed by reed (Phragmites australis), cattail (Thypha spp.) and round-headed club-rush (Scirpoides holoschoenus). In the surroundings there is a still sparsely developed grove containing poplars (Populus spp.), willows (Salix spp.), field elms (Ulmus minor) and tamarisks (Tamarix spp.). In the undergrowth there are wild roses (Rosa spp.) and hawthorns (Crataegus monogyna). Mean annual temperature is 12–13 °C and mean annual precipitation is 500–600 mm.

La Chanta wetland is located in a former limestone quarry that was ecologically restored between 2020 and 2021. Several monitoring programs are being implemented to assess the progress of the different types of habitats created and to monitor the evolution of several fauna groups, including birds. The quality of the wetland’s waters has allowed the formation of large areas of Characeae (charophyte algae, which form habitat 3140 of Directive 92/43/EEC, “hard oligo-mesotrophic waters with benthic vegetation of Chara spp.”) and, under their protection, communities of aquatic macroinvertebrates and amphibians have emerged [47]. Habitat 3140 is usually found in low to medium nutrient-rich, clear water and tends to disappear due to eutrophication. For this reason management is mostly directed to conserve an optimum water quality [48]. The restoration of the old quarry has attracted diverse species of fauna and constitutes a hotspot of biodiversity in a landscape dominated mainly by agriculture. Four species of amphibians now reproduce in its waters, and the vegetation on the banks and islands is home to excellent populations of odonates, water birds, marsh birds, and grove birds, and even two pairs of marsh harriers (Circus aeruginosus). These ecological values have led to the protection of the La Chanta wetland at the regional level since 2023 [49]. In addition, the rocky slopes and rock faces, once suitable, constitute habitats of European interest (8130, “Western Mediterranean and thermophilous scree” and 8210, “Calcareous rocky slopes with chasmophytic vegetation”) in which chasmophytes (genus Antirrhinum, Linaria, Sedum, etc.) are thriving [47].

Among other environmental parameters, its soundscape is being monitored [49]. As the audio recordings themselves can also be used to evaluate variations in avian diversity in space and time, a commonly used metric to assess environmental changes [23], it was considered appropriate to evaluate the use of audio files and the performance of BirdNET Analyzer for their potential use in wildlife surveys. Furthermore, given that many bird species depend on acoustic communication for a variety of social interactions, as well as on their acoustic environment [50,51,52].

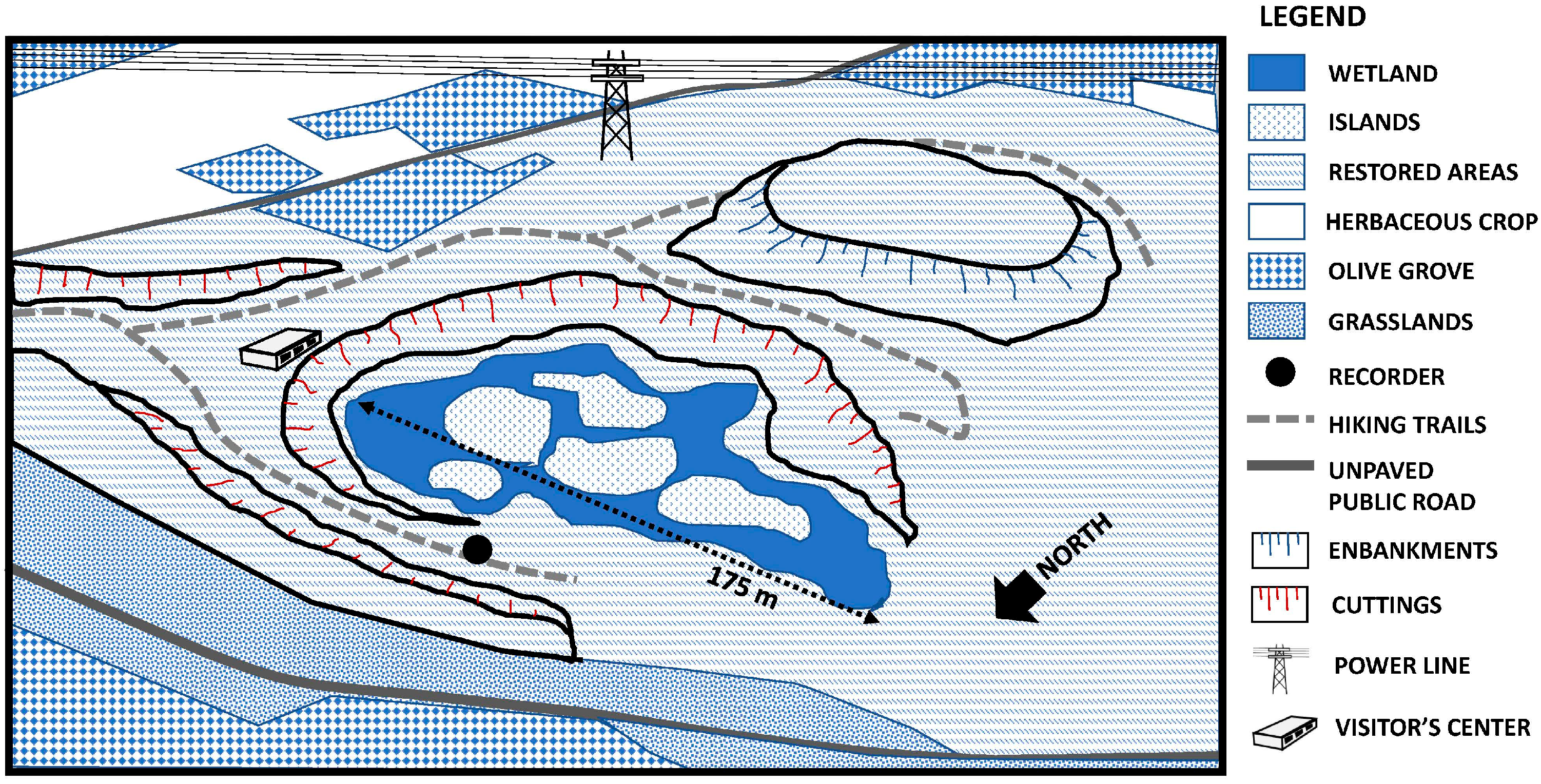

Figure 2.

(A) Study area location (map derived from “Mapa provincial de Madrid 1:200.000” year 2022, MP200raster 1922–2025 CC-BY 4.0 Instituto Geográfico Nacional, www.ign.es (access on 1 October 2025), in accordance with the Spanish Orden FOM/2807/2015 [53]). (B) View of La Chanta wetland (December 2022) from near the acoustic sampling point. Details of plantations on islands and on cut slopes of the old quarry, and protective tubes against herbivores (green tubes).

Figure 2.

(A) Study area location (map derived from “Mapa provincial de Madrid 1:200.000” year 2022, MP200raster 1922–2025 CC-BY 4.0 Instituto Geográfico Nacional, www.ign.es (access on 1 October 2025), in accordance with the Spanish Orden FOM/2807/2015 [53]). (B) View of La Chanta wetland (December 2022) from near the acoustic sampling point. Details of plantations on islands and on cut slopes of the old quarry, and protective tubes against herbivores (green tubes).

3.2. Passive Acoustic Monitoring

To sample sound, a Song Meter Mini Bat recorder (Wildlife Acoustics, Maynard MA, USA) was used with an acoustic microphone that, in the utilized configuration, captures ambient sound up to a frequency of 12 kHz. The ARU was mounted on the trunk of a black poplar (Populus nigra) tree, next to the edge of the wetland (Figure 3), and secured to a branch with cable ties (at a height of approximately 3 m above ground level), with the microphone always facing in the same direction. An ultrasonic microphone and an acoustic microphone are placed on opposite sides of the recorder, and they were always oriented in parallel to the northern edge of the wetland. The acoustic microphone faced east, and the ultrasonic microphone faced west. Only the recordings from the acoustic microphone were analyzed in this study. An original manufacturer’s windscreen was used to protect the microphone. Recordings were made at a sampling rate of 24 kHz, a gain of +18 dB, and a depth of 32 bits in “.wav” format. Our research was conducted as part of a broader study of the wetland soundscape, in which the recorder was programmed to record for 5 min every 20 min throughout the 24 h of the day. Sound recordings were obtained over 42 months, between June 2021 and March 2025. Subsequently, inspired by the five-minute bird count (5MBC) method per sampling site, which has been a well-known standard method for bird counting since the early 1970s [54]. In most temperate situations, a short count duration of 5 min is sufficiently long to obtain a somewhat representative sample of species richness from a site [55,56]. Among the dates available with sound sampling data for each month, the dates closest to the fieldwork corresponding to the wetland bird inventory carried out by local birders were selected first. Thus, we selected a single file per month from 15 min before local sunrise to 1:00 h later on days without any precipitation nor wind interferences, because they represent the time when birds vocalize most frequently [57].

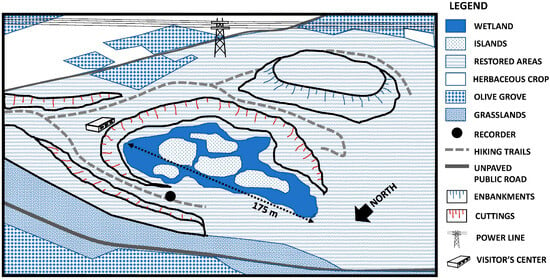

Figure 3.

Oblique drawing of La Chanta wetland with relevant features (unscaled). The figure offers an illustration of the main forms of cultivation in the wetland surrounding terrains (herbaceous crops and olive groves mainly) and the relative location of the main sources of anthropogenic noise (unpaved rural roads) and a high-voltage power line. To a large extent, their effects are shielded by the excavation cuts and the plateau-like embankment. The black dot represents the location of the audio recorder during acoustic monitoring of the wetland soundscape.

The main sources of anthropogenic noise are daytime and sporadic, such as agricultural vehicles on surrounding unpaved rural roads and airplanes. The closest permanent source of noise is a high-voltage power line (200 m away from the center of the wetland), but the geomorphological design of the restoration itself means that the wetland is protected by a small plateau of material from former quarry. It can be considered a quiet area, and the average equivalent continuous noise levels are estimated at 38 dBA throughout the year. The background noise level (considered to be the level exceeded during 90% of the total measurement time, LA90), is around 26 dBA next to the location of the recorder, at the edge of the wetland [49].

3.3. Data Processing

We used BirdNET Analyzer v. 2.1.0, which was the most up-to-date version at the time of this analysis, available on GitHub (https://github.com/birdnet-team/BirdNET-Analyzer) (accessed on 28 June 2025). BirdNET is able to identify over 6500 bird species (see full description in [23]. Among the BirdNET configuration parameters mentioned above, we selected the option “Species by location” (we indicated the coordinates of La Chanta wetland) and checked the option “Year round”. Regarding “Minimum confidence”, we chose to leave the default value (i.e., 0.25), since we were going to test different Sensitivity settings. Given that adjusting the Sensitivity parameter will change the relative distribution of confidence prediction scores and, therefore, the specific threshold value calculated to achieve a particular performance metric [40]. Furthermore, this approach provides reliable presence-absence data quickly and efficiently without having to define specific thresholds for each species [38], which would be a task far from the purpose of our research. To clarify this point, Wood and Kahl [32] presented the equation of BirdNET’s confidence score as follows:

Regarding the Sensitivity and Overlap parameters, all combinations between four values of the Overlap parameter (0.1, 1.0, 2.0 and 2.9 s) and three values of the Sensitivity parameter (0.75, 1.00 and 1.25), were used. To evaluate the results of BirdNET’s predictions, two local expert birders familiar with the local avifauna verified BirdNET’s predictions from each 5 min audio recording to confirm whether each BirdNET predicted species was present or absent.

Two ornithology experts (RA and RS) used Kaleidoscope Lite Analysis Software version 5.6.8 (Wildlife Acoustics, Maynard MA, USA) to visualize the spectrograms corresponding to BirdNET predictions and listen to detections. RA has over 30 years of experience, and RL has over 15 years of experience as ornithological technicians in population census campaigns, migratory censuses, wildlife inventories, reintroduction projects, and at a well-known recovery center for nocturnal birds of prey in Spain (Brinzal). The experts inspected all recordings and documented all identifiable and dismissible species from the audio recordings, alternating between visual inspection of the spectrograms and listening to the vocalizations as necessary to confirm the presence or absence of each species predicted by BirdNET. Since the aim was not to analyze behavior or interactions between different sound sources, once the audio recording of a species was confirmed, it was not considered necessary to validate all predictions for that species. However, all records of species classified as false positives were inspected.

3.4. BirdNET Performance Assessment

For the evaluation of BirdNET performance, we defined four possible categories of results in the identification of species from audio samples:

- True Positives (TP), species correctly identified by BirdNET for the corresponding configuration.

- False Positives (FP), species misidentified by BirdNET based on audio samples and considered absent from La Chanta wetland.

- True Negatives (TN), species not identified by BirdNET for the corresponding configuration that have been identified by other BirdNET configurations in this study and are considered absent species in the La Chanta wetland to date.

- False Negatives (FN), for the definition of a false negative, we considered two possible scenarios:

- FN in Scenario A, species not predicted by BirdNET (whether or not included in the audio samples) whose presence has been confirmed in La Chanta wetland. This list consists of 80 species of birds (Table S1).

- FN in Scenario B, when a species identified by the experts was not predicted by BirdNET in the audio samples. In this scenario, FN refers to a list of 68 species whose recording in the audio samples has been validated by the expert birders (Table S1).

Based on the categorization described, we calculated four of the more frequent metrics used in machine learning to evaluate the performance of classification models (i.e., Precision, Recall, False Positive Rate (FPR) and F1-Score) [58,59]. We also calculated the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC), due to the currently growing criticism against F-Score because it does not take the number of true negatives into account [60], among other reasons [61,62]. MCC is recommended by researchers in case of unbalanced datasets [61,63,64], a very common case in event count as those evaluated by BirdNET use [65].

In addition, we calculated Species Loss (SL). Given that, in certain cases, traditional evaluation measures of classifiers may be not appropriate [61,63,64]. In fact, the empirical evaluation of algorithms and classifiers is a matter of on-going debate between researchers and other metrics (e.g., failure avoidance) may be preferable [66]. In our case study, all species are of interest and they should be distinguished by classifiers. It should be noted that the main objective of this analysis of audio samples is to contribute to the inventory of bird species in La Chanta wetland.

All these metrics for evaluating BirdNET’s performance were calculated for all possible combinations between the four values considered for the Overlap parameter (0.1, 1.0, 2.0, and 2.9) and the three values considered for the Sensitivity parameter (0.75, 1.00, and 1.25). All these indices are normalized between 0 and 1:

- Precision (P) is defined as the proportion of predictions that are correct [32],

P = TP/(TP + FP)

- Recall (R, or True Positive Rate, TPR) is defined as the proportion of target signals that were correctly identified as such [32],

R = TP/(TP + FN)

- False Positive Rate (FPR) is calculated by dividing the number of species incorrectly identified by the total number of species absent from the acoustic sample analyzed (Equation (3)), considering the complete list of species inventoried in La Chanta wetland since 2021. In this way, this index estimates the probability that a species absent from the acoustic sample will be detected by BirdNET [28],

FPR = FP/(FP + TN)

- Fβ-Score is a statistical measure used in machine learning to evaluate the performance of binary classification models based on the balance between Precision and Recall, depending on specific needs [67],

- β is the parameter that reflects the importance we give to Precision or Recall. If β > 1, F becomes more Recall -oriented and if β < 1, it becomes more Precision oriented is the relative importance given to recall over precision. If Recall and precision are of equal weight, β = 1.0, it is called F1-Score and it represents the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall [67]. In this case, the value of the F1-Score lies between 0 and 1, with one being the best and F1-Score reaches is worst value at 0.

- Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) is a contingency matrix method of calculating the Pearson product moment correlation coefficient between actual and predicted values. It is defined as follows, in terms of TP, TN, FP and FN [64].

- Species Loss (SL) indicates the ratio between the number of unidentified bird species in each combination of the Overlap and Sensitivity parameters and the maximum number of species correctly identified by any of these combinations (Maxsp). In scenario A, SL is calculated with respect to 80 species with confirmed presence in the wetland (Table S1). In scenario B, SL is calculated with respect to 68 species identified in the audio samples and with confirmed presence in the wetland (Table S1).

SL = (Maxsp − TP)/(Maxsp)

3.5. A Multi-Objective Optimization Problem

Multi-objective problems often involve considering several criteria that frequently conflict with each other [68]. The Pareto frontier shows a set of optimal solutions from which we can choose according to our priorities [69]. Pareto dominance is often used in decision making and relies on qualitative or ordinal preference information, which, depending on the case, may be easier to obtain from a decision maker [70]. Applied to our case, the problem consists of finding optimal BirdNET configuration solutions with two input parameters (i.e., Overlap and Sensitivity) when it is not possible to improve one performance evaluation index without worsening another [71]. However, if one metric is considered a priority, in our case SL over the other metrics (Precision, Recall, FPR, F1-Score, and MCC), the main objective would be to minimize species loss. Then, combinations with the minimum SL value would be considered optimal. To rank the possible solutions that offer the same minimum SL metric value, a second criterion could be applied. For example, the best balance between the other metrics or weighting one of them above the rest [72]. In our case, we prefer to minimize the validation effort for experts (i.e., minimize the number of vocalizations or species that need to be validated). Because in this case, the aim is not to evaluate aspects of wildlife behavior or the impact of other potential sound sources on BirdNET predictions.

4. Results

As expected, both the number of vocalizations and the number of species identified by BirdNET increase with the value of the Overlap and Sensitivity parameters (Table 1), so the effort required to validate BirdNET predictions by experts is also directly proportional to the value of these parameters. The confusion matrix also shows a significant increase in the number of FP when Sensitivity is 1.25 compared to the other configurations of this parameter (Table 2). This increase is much greater than, for example, that of the number of TP. This fact makes the Precision value significantly low (Table 3 and Table 4) in the combinations of the Overlap and Sensitivity parameters that identify the highest number of bird species. The maximum accuracy according to our objectives (when SL is minimal) is achieved with Precision values between 0.29 and 0.36 in both Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 1.

Number of vocalizations and species predicted by BirdNET for the different combinations of Overlap and Sensitivity.

Table 2.

Results of the confusion matrix for the different combinations of Overlap and Sensitivity.

Table 3.

Performance table referring to the 80 species of birds inventoried in the study area.

Table 4.

Performance table referring to the 68 bird species identified through audio recordings out of the 80 species inventoried in the study area.

The lowest value allowed by the Sensitivity parameter setting (i.e., 0.75) does not work, in any combination with the possible Overlap values, to identify all the bird species whose vocalizations are recorded in the analyzed audio samples. On the contrary, the lowest value of the Overlap parameter (i.e., 0.0 s) does allow, in some of the combinations with the possible values of Sensitivity (e.g., 1.25), the identification of the 68 species in La Chanta bird inventory whose voices are included in the recordings (Table 2). In fact, the 68 bird species recorded in the audio samples were identified when the Sensitivity value was 1.25 and in all the assessed combinations of the Overlap parameter (i.e., 0.0, 1.0, 2.0, and 2.9 s).

When sensitivity is 1.25, the maximum Recall (or TPR) value is 0.85 in scenario A, which refers to the complete inventory of avifauna in La Chanta (Table 3), or 1.00 if calculated with respect to the 68 bird species identified by experts in the recordings (scenario B). In the first of these two scenarios, SL is 0.15 (15% of the birds inventoried in La Chanta are not recorded in the audio samples collected), and in the second scenario, SL is 0.00 (the 68 species for which the different metrics are calculated have been identified by BirdNET). With regard to the other metrics for assessing BirdNET performance, FPR increases with the value of Overlap and Sensitivity (Table 3 and Table 4). On the other hand, the F1-Score and MCC metrics perform inversely. F1-Score and MCC values closer to 0 indicate poorer performance by BirdNET and, in addition, are more time consuming due to the need to review a greater number of vocalizations and bird species predicted by the algorithm.

5. Discussion

The main finding in this work is that the lowest SL value (the main objective of applying PAM techniques in the study area) is achieved when the Sensitivity parameter equals 1.25 in the four Overlap configurations evaluated (0.0, 1.0, 2.0, and 2.9). In other words, the most appropriate Sensitivity configuration for this objective is the one that corresponds to the highest value that BirdNET allowed. However, recent research on the effect on the Sensitivity parameter (based on an earlier version of BirdNET that allowed its setting to be modified between 0.5 and 1.5) suggested that its minimum setting (i.e., 0.5) maximizes overall performance for community-level analyses across all confidence thresholds [37]. Our result is closer to the criterion adopted by Funosas et al. [28] for the configuration of BirdNET in the specific context of their study, which compressed datasets from 194 different sites. Nevertheless, these studies are based on the prioritization criterion of the total area under the curve of Precision-Recall (PR AUC). They also calculated AUC of Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC AUC) and F1-Score, although with varying results. In this sense, it should be noted that PR-AUC is also impacted by imbalanced datasets [73].

Another relevant reason that may justify this difference in interpretation between our study and previous literature is that, in most published studies, the analyses are based on comparing the results of the algorithm’s predictions with visual or listening supervision performed by experts on the same audio recordings [30]. In our case, the evaluation of BirdNET performance aims to verify the usefulness of PAM applied to the monitoring of birds in a real restoration project of a restored quarry, for the purpose of inventorying birds in a study area, based on a catalogue of species whose presence has been verified in situ. The objective of using BirdNET may determine the choice of metrics for assessing predictions and, similarly, the configuration parameters of the tool [38,74,75]. In our case, we did not intend to calculate population densities or to characterize the activity of the species. In this case, among the usual BirdNET evaluation metrics, only Recall allows us to identify the combination of Overlap and Sensitivity settings that meets our objectives (minimizing SL).

Fairbairn et al. [38] conducted another of the few studies that analyzed the influence of Overlap and Sensitivity on BirdNET performance. They recommended using an overlap between 1 and 2 s for short 1 to 5 min recording schemes and also commented that an overlap may not be necessary depending on the cases. This recommendation could coincide with some of our optimal combinations in terms of the Overlap parameter. However, based on their findings, they also recommended keeping the default Sensitivity value (1.0) when maintaining higher minimum confidence thresholds. But in cases such as the aims of our study, that recommendation is not applicable. Furthermore, it must be remembered that confidence scores vary with the Sensitivity parameter setting, as has already been indicated in the methods and materials section [32,40].

Sensitivity controls the shape of the sigmoid curve, which affects how strict or permissive the model is when deciding whether a sound belongs to a species [32]. With a high sensitivity value, the model accepts weaker signals as possible detections. Although this causes an increase in the number of false positives, it also reduces SL, which can be key in studies such as ours, depending on the objective [37,38,75]. On the other hand, higher Overlap values increase the number of vocalizations and processing time. In large datasets, the increase in processing and validation time may not be worth it without providing many benefits in terms of Recall [35]. So, in our study, once we have identified the Sensitivity values that allow us to minimize SL, we should then consider the value of Precision as an indicator of the validation effort in PAM. In this case, very small variations in the Precision value imply a significant change in the number of individual vocalizations and species predicted by the BirdNET algorithm. This is largely due to the possible double-counting (or more) of the same bird vocalization detected in two overlapping segments.

As already mentioned, our results show that at equal SL values, the highest Precision is obtained with the combination of parameters Overlap = 0 and Sensitivity = 1.25 (Table 5 and Table 6). Therefore, this would be the optimal combination of Overlap and Sensitivity that minimizes the loss of species in the bird inventory using PAM in La Chanta wetland and, at the same time, implies the least validation effort. This approach to an optimization problem is close to the concept of the Pareto frontier, a method for solving multi-objective optimization problems [72,76]. In our case, as already indicated, the second criterion would be to minimize the number of BirdNET predictions to be verified, i.e., the validation time of expert birders (Table 5 and Table 6). Therefore, secondly, we would prioritize solutions at the Pareto frontier that reduce the number of vocalizations or species to be validated. This is very relevant considering the impact on the level of Precision or FPR in our case study (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 5.

Pareto solutions sorted by the minimum SL value in Scenario A (referring to the 80 bird species) and, secondly, the lowest number of vocalizations and species to review.

Table 6.

Pareto solutions sorted by the minimum SL value in Scenario B (referring to the 68 species recorded in the audio files) and, secondly, the lowest number of vocalizations and species to review.

As can be seen in Table 5 and Table 6, Precision is the same in both comparison scenarios. Precision is not affected by the maximum number of detectable species (Maxsp). However, the TPR (Recall) is modified between the two scenarios. This is because we consider either the maximum number of known species in the study area (80 species) or the maximum number of species identified in the audio recordings (68 out of 80). For this reason, the F1-Score is altered in each reference scenario, because the F1-Score is defined as the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall [67]. These changes also affect the MCC measure in a similar way to the F1-Score. Both indicators show very modest results (less than or equal to 0.5) in solutions that minimize SL. Furthermore, the variability of F1-Score and MCC (Table 3 and Table 4) also does not allow us to identify the combination of Overlap = 0 and Sensitivity = 1.25 as the optimal solution. Therefore, these assessment metrics are not useful for the purpose of our study.

In our case, the BirdNET configuration combinations that produce the lowest SL are those with the highest FPR value. Therefore, the objective of our monitoring distances us from classic quantitative evaluation methods in binary classification on imbalanced datasets [58,59]. In this sense, evaluation measures of machine learning experiments, such as Recall, Precision, and F-Score are considered a common but poorly motivated way evaluating results by some authors [77]. Therefore, we consider it essential to introduce a metric such as SL when deciding on the optimal configuration of BirdNET in community-level studies.

Regarding the lack of motivation or detail provided in many published studies using BirdNET, it should be noted that only 4 out of 69 studies reviewed did not adopt the default BirdNET configuration parameters and, even more, included minimal justification for their decision. This finding reveals a lack of effort in the literature to date to understand the effect that inappropriate use of the tool may have on the results themselves [30,32,78]. Currently, the combination of a freely accessible and user-friendly tool such as BirdNET [38], together with the reduction in the prices of ARUs, is popularizing the widespread use of PAM [79,80]. The appeal of having a tool that offers immediate results without requiring extensive knowledge of ornithology [46] and the inertial use of controversial metrics for evaluating outcomes in machine learning [60,61,62,65,66] can result in a dangerous combination.

As ecological implications of our findings, in the context of this work, we consider that the failure to detect a particular species can affect our understanding of the bird community and its functioning, and therefore, the management of the ecosystem or the development and implementation of conservation measures, for example, if the missing species require them [81]. Furthermore, regarding ecological restoration and the monitoring of such projects, the absence of a species can lead to an inaccurate assessment if there are specific restoration objectives related to the presence or absence of a particular species [82]. For this reason, adequate monitoring is fundamental for determining whether restoration projects are reaching their goals and for verifying their overall effectiveness and success [83]. Our study does not evaluate bird behavior or interactions between birds and different sound sources. This is an aspect that could be addressed with audio recordings [37,56,84,85]. However, the bird inventory is the basis on which to develop more comprehensive ecological analyses, which are very common in acoustic ecology studies [22]. Therefore, our findings have an impact on these potential deductions, which are theoretically more advanced. It is necessary to ensure the accuracy of the bird inventory on which the following analyses are based. In this regard, Huang et al. [86] show how different data sources may produce different inventories that affects the inference of correlations between variables such as functional diversity and environmental factors.

As a final consideration, it is worth mentioning that identifying and measuring how variables such as sounds from other sources (natural or not), signal degradation characteristics for each species, recording device quality and signal-to-noise ratio can affect BirdNET’s automatic signal recognition capabilities [84,87]. This is an interesting issue that has been partially addressed to date in the literature, but not in relation to changes in overlap and sensitivity settings. This could be considered a limitation of our study. However, we point it out as a topic for further research due to its potential interest. Our goal was not to evaluate how these parameters may affect false positive or false negative rates in each of the scenarios. Because our scenarios are based on the same audio files obtained with a single recorder. Therefore, the presence and interactions between different sound sources, the characteristics of the recorder, signal degradation, etc., are constant in each combination of BirdNET configuration parameters and in each scenario analyzed in our work: scenario A, comparison of predictions with the complete list of species with confirmed presence in La Chanta wetland, or scenario B, taking as baseline the list of birds with confirmed presence in the audio files.

We consider our findings to be relevant for two reasons. First, our main result differs from prior research exploring the impact of adjusting the input values of BirdNET parameters that optimize monitoring outcomes for community-level analyses (i.e., the best settings to correctly identify the species that appear in a collection of recordings). Second, setting a Sensitivity value other than 1 causes a problem that needs to be noted in the case of long-term monitoring programs. The Sensitivity values allowed in BirdNET-Analyzer have varied from 0.5 to 1.5 and 0.75 to 1.25 (and, again, to between 0.5 and 1.5) between different versions of the program. It must be noted that changes in the Sensitivity parameter will modify the relative distribution of confidence prediction scores [32,40]. Therefore, apart from Sensitivity = 1, other Sensitivity values may be incompatible between different BirdNET versions [88]. It is a significant change that may force researchers to need additional future adjustments when trying to compare results from long term monitoring datasets.

Our findings can be applied by practitioners in various fields related to biodiversity monitoring programs anywhere in the world. Not only in anthropogenically restored environments, but also in natural spaces and any biodiversity monitoring scenario that requires, as in this case study, monitoring the composition of its bird communities. For instance, at the European level, the EU Nature Restoration Law (Regulation (EU) 2024/1991) came into force in 2024. It is considered crucial for restoring biodiversity in the EU and is also a key instrument for helping Member States meet international biodiversity commitments. The Regulation requires the use of biodiversity indicators, such as the common forest bird index based on Brlík et al. [89], as key targets in the forestry and agricultural sectors, as evidence of the success of ecological restorations and its trends to monitor ecosystems’ health.

6. Conclusions

It has been found that the configuration Overlap = 0 and Sensitivity = 1.25 is the optimal solution that minimizes the loss of species in the bird inventory using PAM in La Chanta wetland and, at the same time, implies the least validation effort.

It should be noted that, in our case study at the community level, Recall is the indicator, among the classic ones used to evaluate the performance of binary classification models, that best allows us to identify all combinations of BirdNET configuration parameters that cause the lowest SL.

However, identifying the optimal combination of the Overlap and Sensitivity parameters has been made possible by following the theory of a multi-objective optimization analysis (e.g., the Pareto frontier) as an alternative to calculating PR AUC or ROC AUC, whose usefulness is limited with unbalanced datasets.

Our study demonstrates that appropriate adjustments for Overlap and Sensitivity parameters may be crucial due to the ecological implications associated with species loss (actual or apparent) in environmental assessment, behavioral studies, or functional diversity studies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/environments13010031/s1, Table S1: Predictions resulting from BirdNET for the different Overlap and Sensitivity settings; Table S2: List of articles reviewed to analyze the consideration of the Overlap and Sensitivity parameters in scientific literature; Table S3: Information on the seasonal presence of the species inventoried; Table S4: Technical specifications of the recorder.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S.-T. and C.I.-M.; methodology, R.S.-T., R.A. and C.I.-M.; software, R.S.-T., R.A. and C.I.-M.; validation, R.S.-T. and R.A.; formal analysis, R.S.-T., R.A. and C.I.-M.; investigation, R.S.-T., R.A. and C.I.-M.; resources, R.A. and C.I.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.I.-M.; writing—review and editing, R.S.-T., R.A. and C.I.-M.; visualization, C.I.-M.; supervision, C.I.-M.; project administration, R.A. and C.I.-M.; funding acquisition, R.A. and C.I.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by HOLCIM España (FUCOVASA-FACT-N-P-2021/43).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in Tables S1 and S2. The original field recordings are under the custody of the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid in compliance with the Spanish Data Protection Act.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank HOLCIM España, owner of La Chanta and the company who made the restoration project, for allowing the field work and supporting it economically. In particular we are very grateful to Pilar Gegúndez, Laura Martín, José María Martínez and Mariano García. We also appreciate the support of Luis Alberto Toledano and Iván García (Brinzal) for their help during the field work and Blas Molina, José Manuel Sayago e Iñigo Zuberogoitia for their help identifying some bird sounds. Finally, we would also like to thank the support of the Conde del Valle de Salazar Foundation. During the preparation of this study, the authors used Microsoft Copilot (Microsoft, 2025) as a tool to explore and study multi-objective optimization methodologies. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ARUs | Acoustic recording units |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| FN | False Negatives |

| FP | False Positives |

| FPR | False Positive Rate |

| EU | European Union |

| MCC | Matthews correlation coefficient |

| NRL | Nature Restoration Law |

| PAM | Passive acoustic monitoring |

| PR | Precision–Recall |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SL | Species Loss |

| TN | True Negatives |

| TP | True Positives |

| WoS | Web of Science |

References

- Schiavo, G.; Portaccio, A.; Testolin, A. Fine-Tuning BirdNET for the Automatic Ecoacoustic Monitoring of Bird Species in the Italian Alpine Forests. Information 2025, 16, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western, D. The Biodiversity Crisis: A Challenge for Biology. Oikos 1992, 63, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hald-Mortensen, C. The Main Drivers of Biodiversity Loss: A Brief Overview. J. Ecol. Nat. Resour. 2023, 73, 7. [Google Scholar]

- IPBES. Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem services; Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES): Bonn, Germany, 2019; 56p, Available online: https://files.ipbes.net/ipbes-web-prod-public-files/inline/files/ipbes_global_assessment_report_summary_for_policymakers.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Jaureguiberry, P.; Titeux, N.; Wiemers, M.; Bowler, D.E.; Coscieme, L.; Golden, A.S.; Guerra, C.A.; Jacob, U.; Takahashi, Y.; Settele, J.; et al. The direct drivers of recent global anthropogenic biodiversity loss. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm9982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, J.; Pietrobelli, C. Natural resource based growth, global value chains and domestic capabilities in the mining industry. Resour. Policy 2018, 58, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igogo, T.; Awuah-Offei, K.; Newman, A.; Lowder, T.; Engel-Cox, J. Integrating renewable energy into mining operations: Opportunities, challenges, and enabling approaches. Appl. Energy 2021, 300, 117375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichl, C.; Schatz, M.; Masopust, A. World Mining Data 2025. Iron and Ferro-Alloy Metals. Non-Ferrous Metals. Precious Metals. Industrial Minerals. Mineral Fuels; Federal Ministry of Finance: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Volume 40, 264p, Available online: https://www.bmf.gv.at/dam/jcr:b778238b-9952-4fee-84ab-f3293b00c4e9/WMD%202025.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Dias, S.; Almeida, J.; Tadeu, A.; De Brito, J. Alternative concrete aggregates—Review of physical and mechanical properties and successful applications. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 152, 105663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Mineral exploration and the green transition: Opportunities and challenges for the mining industry. Resour. Policy 2023, 86, 104263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Climate crisis, cities, and health. Lancet 2024, 404, 1693–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahirwal, J.; Pandey, V.C. Restoration of mine degraded land for sustainable environmental development. Restor. Ecol. 2021, 29, e13268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CORDIS—EU. Innovative Digital Sustainable Aggregates Systems; CORDIS—EU: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapico, I.; Laronne, J.B.; Sánchez Castillo, L.; Martín Duque, J.F. Drainage network evolution and reconstruction in an open pit kaolin mine at the edge of the Alto Tajo natural Park. CATENA 2021, 204, 105392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.E.; Gann, G.D.; Walder, B.; Liu, J.; Cui, W.; Newton, V.; Nelson, C.R.; Tashe, N.; Jasper, D.; Silveira, F.A.O.; et al. International principles and standards for the ecological restoration and recovery of mine sites. Restor. Ecol. 2022, 30, e13771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prach, K.; Janečková, P.; Walker, L.R. Europe’s Nature Restoration Law has now been adopted. What Comes Next? Oikos 2025, 2025, e11209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perissi, I. Assessing the EU27 Potential to Meet the Nature Restoration Law Targets. Environ. Manag. 2025, 75, 711–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hering, D.; Schürings, C.; Wenskus, F.; Blackstock, K.; Borja, A.; Birk, S.; Bullock, C.; Carvalho, L.; Dagher-Kharrat, M.B.; Lakner, S.; et al. Securing success for the Nature Restoration Law. Science 2023, 382, 1248–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraixedas, S.; Lindén, A.; Piha, M.; Cabeza, M.; Gregory, R.; Lehikoinen, A. A state-of-the-art review on birds as indicators of biodiversity: Advances, challenges, and future directions. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 118, 106728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roché, J.; Godinho, C.; Rabaça, J.E.; Frochot, B.; Faivre, B.; Mendes, A.; Dias, P. Birds as bio-indicators and as tools to evaluate restoration measures. In Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on Ecological Restoration, Avignon, France, 23–27 August 2010; Society for Ecological Restoration: Avignon, France, 2010. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10174/6870 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- EU. Regulation (EU) 2024/1991 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 June 2024 on Nature Restoration and Amending Regulation (EU) 2022/869; Official Journal of the European Union, L series; European Union: Luxembourg, 2024; 93p. [Google Scholar]

- Sueur, J.; Pavoine, S.; Hamerlynck, O.; Duvail, S. Rapid Acoustic Survey for Biodiversity Appraisal. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, S.; Wood, C.M.; Eibl, M.; Klinck, H. BirdNET: A deep learning solution for avian diversity monitoring. Ecol. Inform. 2021, 61, 101236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.M.; Kahl, S.; Barnes, S.; Van Horne, R.; Brown, C. Passive acoustic surveys and the BirdNET algorithm reveal detailed spatiotemporal variation in the vocal activity of two anurans. Bioacoustics 2023, 32, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.R.P.-J.; O’Connell, D.P.; Deichmann, J.L.; Desjonquères, C.; Gasc, A.; Phillips, J.N.; Sethi, S.S.; Wood, C.M.; Burivalova, Z. Passive acoustic monitoring provides a fresh perspective on fundamental ecological questions. Funct. Ecol. 2023, 37, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugai, L.S.M.; Silva, T.S.F.; Ribeiro, J.W.; Llusia, D. Terrestrial Passive Acoustic Monitoring: Review and Perspectives. BioScience 2019, 69, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Rubio, R.; Bota, G.; Brotons, L.; Soto-Largo, E.; Pérez-Granados, C. Low-cost open-source recorders and ready-to-use machine learning approaches provide effective monitoring of threatened species. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 72, 101910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funosas, D.; Barbaro, L.; Schillé, L.; Elger, A.; Castagneyrol, B.; Cauchoix, M. Assessing the potential of BirdNET to infer European bird communities from large-scale ecoacoustic data. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 164, 112146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, D.; Roe, P.; Van Rensburg, B.J.; Linke, S.; McDonald, P.G.; Tucker, D.; Fuller, S. Effective ecological monitoring using passive acoustic sensors: Recommendations for conservation practitioners. Conserv. Sci. Prac. 2024, 6, e13132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Granados, C. BirdNET: Applications, performance, pitfalls and future opportunities. Ibis 2023, 165, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, S. Species Range Model Details #234. Birdnet-Team/BirdNET-Analyzer. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/birdnet-team/BirdNET-Analyzer/discussions/234 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Wood, C.M.; Kahl, S. Guidelines for appropriate use of BirdNET scores and other detector outputs. J. Ornithol. 2024, 165, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, G.E.; Walston, L.J.; Little, A.R. Evaluation of an autonomous acoustic surveying technique for grassland bird communities in Nebraska. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0306580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bota, G.; Manzano-Rubio, R.; Catalán, L.; Gómez-Catasús, J.; Pérez-Granados, C. Hearing to the Unseen: AudioMoth and BirdNET as a Cheap and Easy Method for Monitoring Cryptic Bird Species. Sensors 2023, 23, 7176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, L.; Mahon, C.L.; McLeod, L.; Jetté, J.-F. Artificial intelligence (BirdNET) supplements manual methods to maximize bird species richness from acoustic data sets generated from regional monitoring. Can. J. Zool. 2023, 101, 1031–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, F.; Abrego, N.; Bush, A.; Chase, J.M.; Guillera-Arroita, G.; Leibold, M.A.; Ovaskainen, O.; Pellissier, L.; Pichler, M.; Poggiato, G.; et al. Novel community data in ecology-properties and prospects. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2024, 39, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Granados, C.; Funosas, D.; Morant, J.; Marín Gómez, O.H.; Mendoza, I.; Mohedano-Munoz, M.A.; Santamaría, E.; Bastianelli, G.; Márquez-Rodríguez, A.; Budka, M.; et al. Optimization of passive acoustic bird surveys: A global assessment of BirdNET settings. Ibis 2025. Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbairn, A.J.; Burmeister, J.-S.; Weisser, W.W.; Meyer, S.T. BirdNET can be as good as experts for acoustic bird monitoring in a European city. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0330836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradet, D.T.; Cimino, M.A.; White, E.R.; Kloepper, L.N. Designing a BirdNET classifier for high wind detection in passive acoustic recordings to support wildlife monitoring. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2025, 157, 4502–4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacuzzi, G.; Olden, J.D. Few-shot transfer learning enables robust acoustic monitoring of wildlife communities at the landscape scale. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 90, 103294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Granados, C.; Feldman, M.J.; Mazerolle, M.J. Combining two user-friendly machine learning tools increases species detection from acoustic recordings. Can. J. Zool. 2024, 102, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biffi, S.; Chapman, P.J.; Engler, J.O.; Kunin, W.E.; Ziv, G. Using automated passive acoustic monitoring to measure changes in bird and bat vocal activity around hedgerows of different ages. Biol. Conserv. 2024, 296, 110722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, A.; Beltran, J.; Guindel, C.; Iglesias, J.A.; Garcia, F. BirdNet+: Two-Stage 3D Object Detection in LiDAR Through a Sparsity-Invariant Bird’s Eye View. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 160299–160316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eka Budiyanta, N.; Mulyanto Yuniarno, E.; Usagawa, T.; Purnomo, M.H. Utilizing a Single-Stage 2D Detector in 3D LiDAR Point Cloud With Vertical Cylindrical Coordinate Projection for Human Identification. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 72672–72687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.M.; Kahl, S.; Rahaman, A.; Klinck, H. The machine learning–powered BirdNET App reduces barriers to global bird research by enabling citizen science participation. PLoS Biol. 2022, 20, e3001670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mola, I. Restauración Ecológica: Ejemplos de bases técnicas y soluciones prácticas; Fundación Biodiversidad del Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y Reto Demográfico: Madrid, Spain, 2024; 635p. [Google Scholar]

- 3140 habitat English. Ecopedia. 2025. Available online: https://ecopedia.s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/pdfs/habitat%203140%20english%20layout%20def_0.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Iglesias Merchán, C.; Sánchez Torres, R.; Martín Herranz, L.; García Martínez, I.; Martínez Gascón, J.M.; Alonso Moreno, R.; Gegúndez Cámara, P. Contribuciones de la Restauración de Minas y la Ecología Acústica a la Promoción de Reservas Sonoras de Origen Natural; Fundación Conama: Madrid, Spain, 2024; p. 13. Available online: https://www.fundacionconama.org/wp-content/uploads/conama/comunicaciones/7913/COMUNICACION-Ecologia_Acustica_Minas_v2.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Barrero, A.; Llusia, D.; Traba, J.; Iglesias-Merchan, C.; Morales, M.B. Vocal Response to Traffic Noise in a Non-Passerine Bird: The Little Bustard Tetrax tetrax. Ardeola 2020, 68, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Catasús, J.; Barrero, A.; Llusia, D.; Iglesias-Merchan, C.; Traba, J. Wind farm noise shifts vocalizations of a threatened shrub-steppe passerine. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 303, 119144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Jiménez, L.; Iglesias-Merchan, C.; Barja, I. Behavioral responses of the European mink in the face of different threats: Conspecific competitors, predators, and anthropic disturbances. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BOE. Orden FOM/2807/2015, de 18 de Diciembre, por la que se Aprueba la Política de Difusión Pública de la Información Geográfica Generada por la Dirección General del Instituto Geográfico Nacional. 2015. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2015/BOE-A-2015-14129-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Hartley, L.J. Standard method for counting forest birds in New Zealand since the early 1970s. N. Z. J. Ecol. 2012, 36, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bibby, C.J.; Burgess, N.D.; Hill, D.A.; Mustoe, S. Bird Census Techniques, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK; San Diego, CA, USA; New York, NY, USA; Boston, MA, USA; Sydney, Australia; Tokyo, Japan; Toronto, ON, Canada, 2000; 302p. [Google Scholar]

- Winiarska, D.; Neubauer, G.; Budka, M.; Szymański, P.; Barczyk, J.; Cholewa, M.; Osiejuk, T.S. BirdNET provides superior diversity estimates compared to observer-based surveys in long-term monitoring. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 177, 113747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.S.; Michel, N.L.; Emerson, S.A.; Siegel, R.B. Automated bird sound classifications of long-duration recordings produce occupancy model outputs similar to manually annotated data. Ornithol. Appl. 2022, 124, duac003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, G.; Zuva, T.; Sibanda, E.M. A Review of Evaluation Metrics in Machine Learning Algorithms. In Artificial Intelligence Application in Networks and Systems; Silhavy, R., Silhavy, P., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 724, pp. 15–25. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-031-35314-7_2 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Rainio, O.; Teuho, J.; Klén, R. Evaluation metrics and statistical tests for machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christen, P.; Hand, D.J.; Kirielle, N. A Review of the F-Measure: Its History, Properties, Criticism, and Alternatives. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, R.; Edalo, C.; Awe, O.O. Machine Learning Evaluation of Imbalanced Health Data: A Comparative Analysis of Balanced Accuracy, MCC, and F1 Score. In Practical Statistical Learning and Data Science Methods; Awe, O.O., Vance, E.A., Eds.; STEAM-H: Science, Technology, Engineering, Agriculture, Mathematics & Health; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 283–312. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-031-72215-8_12 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Hand, D.J.; Christen, P.; Kirielle, N. F*: An interpretable transformation of the F-measure. Mach. Learn. 2021, 110, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughorbel, S.; Jarray, F.; El-Anbari, M. Optimal classifier for imbalanced data using Matthews Correlation Coefficient metric. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Jurman, G. The advantages of the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) over F1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansar, W.; Chatterjee, A.; Goswami, S.; Chakrabarti, A. An EfficientNet-Based Ensemble for Bird-Call Recognition with Enhanced Noise Reduction. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, M.; Japkowicz, N.; Szpakowicz, S. Beyond Accuracy, F-Score and ROC: A Family of Discriminant Measures for Performance Evaluation. In AI 2006: Advances in Artificial Intelligence; Sattar, A., Kang, B., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 4304, pp. 1015–1021. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/11941439_114 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Takahashi, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Kuchiba, A.; Koyama, T. Confidence interval for micro-averaged F1 and macro-averaged F1 scores. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 4961–4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Balteiro, L.; Iglesias-Merchan, C.; Romero, C.; García De Jalón, S. The Sustainable Management of Land and Fisheries Resources Using Multicriteria Techniques: A Meta-Analysis. Land 2020, 9, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certa, A.; Galante, G.; Lupo, T.; Passannanti, G. Determination of Pareto frontier in multi-objective maintenance optimization. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2011, 96, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, C.; Wilson, N. Sorted-Pareto Dominance and Qualitative Notions of Optimality. In Symbolic and Quantitative Approaches to Reasoning with Uncertainty; Van Der Gaag, L.C., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 7958, pp. 449–460. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-642-39091-3_38 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Intriligator, M.D. Mathematical Optimization and Economic Theory; Classics in Applied Mathematics; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002; 528p. [Google Scholar]

- Giagkiozis, I.; Fleming, P.J. Methods for multi-objective optimization: An analysis. Inf. Sci. 2015, 293, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E.; Trevizani, R.; Greenbaum, J.A.; Carter, H.; Nielsen, M.; Peters, B. The receiver operating characteristic curve accurately assesses imbalanced datasets. Patterns 2024, 5, 100994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, F.K.W.; Schwarzkopf, L.; Allen-Ankins, S. Advancing invasive species monitoring: A free tool for detecting invasive cane toads using continental-scale data. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 89, 103172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegenhorn, M.A.; Lanctot, R.B.; Brown, S.C.; Brengle, M.; Schulte, S.; Saalfeld, S.T.; Latty, C.J.; Smith, P.A.; Lecomte, N. ArcticSoundsNET: BirdNET embeddings facilitate improved bioacoustic classification of Arctic species. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 90, 103270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engau, A.; Sigler, D. Pareto solutions in multicriteria optimization under uncertainty. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 281, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, D.M.W. Evaluation: From precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. arXiv 2008, arXiv:2010.16061. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, S.; Hodder, D.P.; Otter, K.A. Setting BirdNET confidence thresholds: Species-specific vs. universal approaches. J. Ornithol. 2025, 166, 1123–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, R.; Browning, E.; Glover-Kapfer, P.; Jones, K.E. Emerging opportunities and challenges for passive acoustics in ecological assessment and monitoring. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2019, 10, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefer, S.; McKnight, D.T.; Allen-Ankins, S.; Nordberg, E.J.; Schwarzkopf, L. Passive acoustic monitoring in terrestrial vertebrates: A review. Bioacoustics 2023, 32, 506–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, D.I.; Nichols, J.D.; Lachman, G.B.; Droege, S.; Andrew Royle, J.; Langtimm, C.A. Estimating site occupancy rates when detection probabilities are less than one. Ecology 2002, 83, 2248–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Jaen, M.C.; Mitchell Aide, T. Restoration Success: How Is It Being Measured? Restor. Ecol. 2005, 13, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Toribio, M.; Martínez-Garza, C.; Ceccon, E. Challenges during the execution, results, and monitoring phases of ecological restoration: Learning from a country-wide assessment. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Granados, C. A First Assessment of Birdnet Performance at Varying Distances: A Playback Experiment. Ardeola 2023, 70, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Chi, T.; Vu, T.T.; Nguyen, H.T.; Clink, D.J. Circadian rhythms and the use of transfer learning for critically endangered crested argus Rheinardia ocellata in the Central Highlands of Vietnam: The implications for conservation. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2025, 380, 20240056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Lin, C.; Ji, L.; Feng, G. Species inventories from different data sources “shaping” slightly different avifauna diversity patterns. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1121422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, F.; Sueur, J.; Sèbe, F.; Le Cesne, M.; Haupert, S. Acoustic detection of a nocturnal bird with deep learning: The challenge of low signal-to-noise ratio. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 181, 114475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, S. Clarification on v2 Breaking Change for Sensitivity Parameter, and Practical Implications for Long-Term Monitoring Projects? 2025. Available online: https://github.com/birdnet-team/BirdNET-Analyzer/issues/758#issuecomment-3137598831 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Brlík, V.; Šilarová, E.; Škorpilová, J.; Alonso, H.; Anton, M.; Aunins, A.; Benkö, Z.; Biver, G.; Busch, M.; Chodkiewicz, T.; et al. Long-term and large-scale multispecies dataset tracking population changes of common European breeding birds. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.