Abstract

This study investigates the effectiveness of cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) treatment for improving the microbiological and physicochemical quality of wastewater generated in tourism-affected coastal regions. Experiments were performed on influent and effluent samples from the Ravda Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP) collected in April, August, and November 2024, representing different seasonal loading conditions. The plasma pre-treatment of influent aimed to minimize toxic micropollutants that inhibit activated sludge activity, reduce pathogenic and opportunistic microorganisms, and enhance oxidative potential before biological processing. The post-treatment of effluent focused on the elimination of residual pathogens, mainly Enterobacteriaceae, and the oxidative degradation of xenobiotics resistant to conventional treatment. Combined fluorescent (CTC/DAPI) and culture-based analyses were used to assess microbial viability and activity. Plasma exposure (1, 3 and 5 min) caused measurable changes in metabolic potential and bacterial abundance across all sampling periods. The results demonstrate that 1 min CAP treatment does not increase pathogen removal, but enhances oxidation capacity of the influent, while 3 min of CAP treatment ensures the disinfection of the effluent. Both can be combined to improve the effluent safety prior to Black Sea discharge. CAP is showing strong potential as a sustainable technology for wastewater management in tourism-intensive coastal zones.

1. Introduction

Wastewater treatment in the tourism sector is one of the key issues of important environmental, social, and economic importance. Of particular importance are the type, modernity, and functioning of water treatment technologies in existing and newly built treatment plants. They are directly related to the protection of the environment and the quality of tourist services [1,2,3,4,5,6].

The Black Sea tourism sector in the Republic of Bulgaria represents a significant component of the country’s economic development and holds particular environmental importance for the preservation of the Black Sea ecosystem. Black Sea tourism in the recreation zone of the Republic of Bulgaria is distinguished by its seasonal nature—an active season from May to October. This seasonal tourism is very much related to the volume, load, type of pollutants, and the need for seasonal changes in the mode of operation of the treatment plants [7,8].

The challenges in the operation of these treatment plants can be generally formulated as follows: 1/Dynamic and large-scale changes in the volume and load of wastewater. As an example, we can point out the Ravda wastewater treatment plant, which in the summer purifies wastewater from large hotel complexes and covers about 220,000 inhabitants, and in the winter season, outside the tourist load, the volume and load of wastewater shrink and amount to a flow formed by about 2000 inhabitants. This necessitates a major change in technology due to expansion during the active tourist season and contraction during the winter season [9,10,11,12].

2/Other critical problems that come to the fore during the active tourist season are the high amounts of various pollutants, including suspended substances, trivial pollutants, micropollutants of a toxic nature—microplastics, antibiotics, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, preservatives, disinfectants, PFAS, surfactants, steroid hormones, and others—which form the complex toxicity of wastewater [13,14,15,16]. These pollutants are in higher concentrations at the entrance to the WWTP, but due to the fact that they are difficult to include in the biodegradation water treatment process, a large part of them remain in the treated water. Due to their low output quantities, they cannot be registered with the common methods used for assessing the quality of purified water and go to the water receivers [17,18,19]. As a consequence, on the basis of accumulation and adsorption processes, they accumulate in sediments, hydrobionts, and trophic chains, and have a lasting damaging effect on hydroecosystems [20,21]. In response to these concerns, the new recast Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive (Directive (EU) 2024/3019) introduces, for the first time, binding EU-wide requirements for the removal of micropollutants. It mandates the implementation of quaternary treatment in large WWTPs (≥150,000 p.e., and ≥10,000 p.e. in risk-sensitive areas) and requires an average 80% removal efficiency for a defined set of twelve-indicator emerging contaminants, primarily pharmaceuticals and benzotriazoles. These obligations are complemented by extended monitoring duties and an extended-producer–responsibility scheme for pharmaceuticals and cosmetics, marking a substantial strengthening of EU policy on micropollutant control [22].

3/An important issue related to the preservation of recreational zones and the protection of tourists’ health is the elimination of pathogenic and opportunistic microorganisms as part of the tertiary treatment of wastewater within water purification technologies. This elimination is most commonly achieved either through chlorination or ultraviolet (UV) disinfection. However, chlorination is not suitable for the discharge of treated waters into recreational areas, even in cases of deep-water discharge, as it leads to additional pollution by residual chlorine-containing compounds, which negatively affect marine ecosystems [20,23]. UV treatment, on the other hand, is a high-cost method, and its application is often limited to cases where elevated levels of pathogenic or other hazardous microorganisms have been detected [24].

Addressing the critical challenges of wastewater treatment in the tourism sector requires the implementation of a variety of innovative methods and technologies, as well as the development of new technological modules. These encompass a wide range of physical, biological, molecular-biological, and chemical innovations, which form the foundation of hybrid treatment technologies [25,26,27,28].

In this aspect, various technological options are created and applied:

1/Expansion of the treatment plants during the active season with additional treatment modules—additional bio-basins, SBR/sequencing batch reactors/, additional primary and/or secondary clarifiers, turning on modules for UV treatment, etc. [29].

2/Sometimes, additional equipment and modules for pre-treatment or post-treatment are included in the technological chain [28]. Most commonly, these are adsorption modules incorporating novel materials as sorbents. Considerable research efforts have been directed toward the engineering of functional materials, such as modified biochars, nanocomposites, and specialized adsorbents tailored for the removal of various contaminants (e.g., heavy metals, nutrients, pharmaceuticals, and others). These modules can be integrated either as pre-treatment units—for the initial conditioning of influent streams—or as post-treatment stages, serving as polishing systems to enhance effluent quality [24,30,31,32,33]. Surface functionalization and hybrid material design enhance both selectivity and adsorption capacity. Beyond the simple removal of contaminants, current technological developments increasingly aim at the recovery of valuable resources such as nutrients (N, P), energy, and embedded materials (e.g., metals from waste streams), thereby promoting the principles of the circular economy [34,35,36,37].

Significant research efforts are devoted to enhancing the resilience of wastewater treatment technologies through a deep understanding of the complex microbial consortia operating within treatment systems (e.g., aerobic and anaerobic granular sludges, biofilms in biofilters, and constructed wetlands). Furthermore, manipulation of the community structure and activity is applied by introducing microbial formulations, enzyme activity stimulators, and micro- and nanoregulators, aiming to achieve sustainable pollutant removal [38,39,40].

An innovation that is in the phase of intensive development is the use of cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) treatment and the application of plasma technologies at atmospheric pressure to solve critical problems—elimination of toxic micropollutants and the disinfection of treated water ensure a subsequent increase in the efficiency of water treatment in biotechnological facilities [41,42]. The plasma produced by gas discharge at atmospheric pressure can be used for direct treatment of various types of samples, including solids and liquids. Indirect treatment is also applied when water or solution is treated by plasma and the treated liquid is after that used for treatment of other samples. This is possible since the plasma treatment of water/liquid produces plasma-activated water (PAW) which is enriched with chemically reactive species. When the liquid sample is directly treated by the plasma, both short- and long-lived reactive species are produced. For indirect treatment only the long-lived particles are in the liquid. For wastewater the direct plasma treatment is preferred for increasing the effectiveness by including the processes with both short- and long-lived reactive species. This allows, without any chemical addition, the changing of various physical, chemical, and biological parameters of water such as pH, salinity [43], conductivity, oxidation–reduction potential (ORP), turbidity, hardness [44], chemical contaminants [45,46], and microbial load [47]. The short-lived species produce hydroxyl radicals (OH•), nitric oxide (NO•), superoxide (O.2), peroxynitrate (OONO.2), and peroxynitrite (ONOO.), which are with subsecond lifetimes [48]. This plasma-generated reactive chemical species play a crucial role in its different biological applications, such as cancer cell treatment [49], dentistry [50], wound healing [51], disinfecting the spoilage microorganisms and foodborne pathogens on food products for the reduction in post-harvest losses, and production of safer foods, as well as to replace the traditional chemical sanitizing solutions applied for disinfection [48,52]. Having a mixture of various plasma-generated reactive oxygen species (ROS) including singlet molecular oxygen in bio-contaminants inactivation during wastewater disinfection is demonstrated to have better antimicrobial ability than a mimicked solution of single ROS [53].

Cold plasma treatment enriches water with a variety of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS). In plasma-activated water (PAW), RONS include both short-lived species and long-lived species, such as nitrate (NO3−), nitrite (NO2−), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which have typical half-lives ranging from years (NO3−), to days (NO2−), and hours (H2O2). The RONS in the water revealed huge potential for their application in environmental protection, including the activation of water treatment processes as well as in the sanitation of the water [29,54].

Mainly the long-lived products of plasma treatment would have an activating effect on the metabolic processes realized in the technological facilities—breaking up the suspended substances, dispersing the microorganisms adsorbed by them, increasing the concentration of nitrites and nitrates and hence stimulating the denitrification processes, increasing the oxidative potential of the waters through dissolved hydroxyl radicals and hydrogen peroxide. Small amounts of reactive species (•OH, NOx, H2O2) can stimulate the growth of certain bacteria through a moderate level of oxidative stress. When properly controlled, plasma treatment can reduce inhibitory substances in wastewater (e.g., toxic compounds, phenols, and others), thereby facilitating microbial activity within the treatment facilities. Evidence also indicates an increase in the BOD5/COD ratio, which improves the characteristics of the influent and enhances its suitability for biological treatment. In many cases, plasma treatment disrupts the bacterial walls and cell membranes of microbial cells. This leads to the activation of some enzyme systems, which in bio-basins would stimulate the degradation of pollutants.

Plasma-based modules can be integrated into treatment technologies either as pre-treatment or post-treatment units. In these applications, by adjusting the parameters of plasma processing, different objectives can be achieved. Pre-treatment of wastewater, prior to its entry into treatment facilities, aims to reduce its toxicity, decrease the concentration of organic molecules that are difficult to degradable, increase the concentration of oxidative species, and, where possible, stimulate the activity of microbial communities within the treatment process in the facilities [41]. The available literature data on the pre-treatment with plasma are limited and are based primarily on changes in the physicochemical properties of the water, without addressing the role of microbial metabolic potential and the microbial structures that exert a significant influence on the treatment processes in all units of wastewater treatment plants—including grit chambers, primary settlers, and bioreactors.

When it comes to post-treatment, there is sufficient data in the literature for the elimination of pathogens, micropollutants, and even antibiotic resistance genes by treating water with cold plasma, but mainly in model water [42]. In the plasma modules for post-treatment of already treated water, two effects are studied and pursued—the elimination of residues of micropollutants of a toxic nature and the elimination of pathogenic microorganisms.

Overall, the influence of plasma treatment on the performance of complete wastewater treatment systems is still insufficiently investigated in the available literature.

An important aspect of eliminating toxic micropollutants from wastewater is process diagnostics and correct assessment. One way is the chemical determination of their concentrations. This is a long, difficult, and inaccurate process due to the fact that micropollutants accumulate in microbial cells, interact with each other, exhibit a synergistic effect (mutual reinforcement of their effect or antagonistic action), reducing the effect of their joint action [41]. The study of their complex toxicity and the influence of the activity of living organisms in wastewater and treated water or in activated sludge is extremely important and valuable. This complex effect of toxicity can be evaluated by a fluorescence method—staining and fluorescence diagnostics of CTC/DAPI and assessment of the detoxication process by means of bioindicator—which uncovers their metabolic microbial potential [55]. This method monitors the ratio between physiological and metabolic active cells compared to all bacterial cells in the water sample. This method enables the assessment of the ratio between physiologically active microbial cells and structures (small microbial consortia) and the total number of microbial cells and consortia. The simultaneous monitoring of both the number and the intensity of the fluorescence signal provides the basis for evaluating the capacity of microbial units to degrade pollutants, thereby linking these observations to key parameters of the wastewater treatment processes occurring within the treatment plant facilities.

In the center of the working hypothesis of this article is the treatment with cold plasma (based on the plasma source Beta device) of influent and effluent in the Ravda Treatment Plant. The aim is to obtain practical functional and metabolic information about the potential for the creation of plasma modules for wastewater pre-treatment in order to activate them and subsequently accelerate the treatment processes in the biotechnological facilities of the Ravda WWTP. The parallel cold plasma treatment of purified water aimed to investigate the potential of plasma treatment to offer a post-treatment module that simultaneously removes residual toxic contaminants and pathogenic bacteria.

The removal of residual toxic contaminants in this study was assessed through indirect, integrative parameters (reflecting overall toxicity and biodegradability), rather than through direct quantification of specific chemical pollutants.

2. Materials and Methods

There are 32 WWTPs in the Bulgarian Black Sea area, shown in Figure 1. Amongst them, 19 are located on the coast, but only 4 have a deep-water discharge system (2.5 km long and 18 m deep) in the Black Sea.

Figure 1.

Map of the WWTPs on the Bulgarian Black Sea coast. (Source: OpenStreetMap).

One of them is Ravda WWTP, which serves the largest resort in Bulgaria and on the Black Sea coast [56], marked with a yellow pin in Figure 2 below. Its operation is of critical importance not only for the national economy but also for protecting the environment from the substantial seasonal pressures associated with intensive summer tourism.

Figure 2.

Map of the Black Sea and the location of Sunny Beach Resort. (Source: Google Earth).

As a seasonal resort operating primarily between May and October, the area experiences limited opportunities for natural environmental recovery compared to destinations with a more evenly distributed visitor load. During the peak tourist season in August 2024, the Ravda WWTP received 959,155 m3 of influent, while in the off-season (November) the volume decreased to 340,821 m3 (monthly data provided by Ravda WWTP). In the absence of industrial activity in the region, the influent consists solely of domestic wastewater and stormwater runoff.

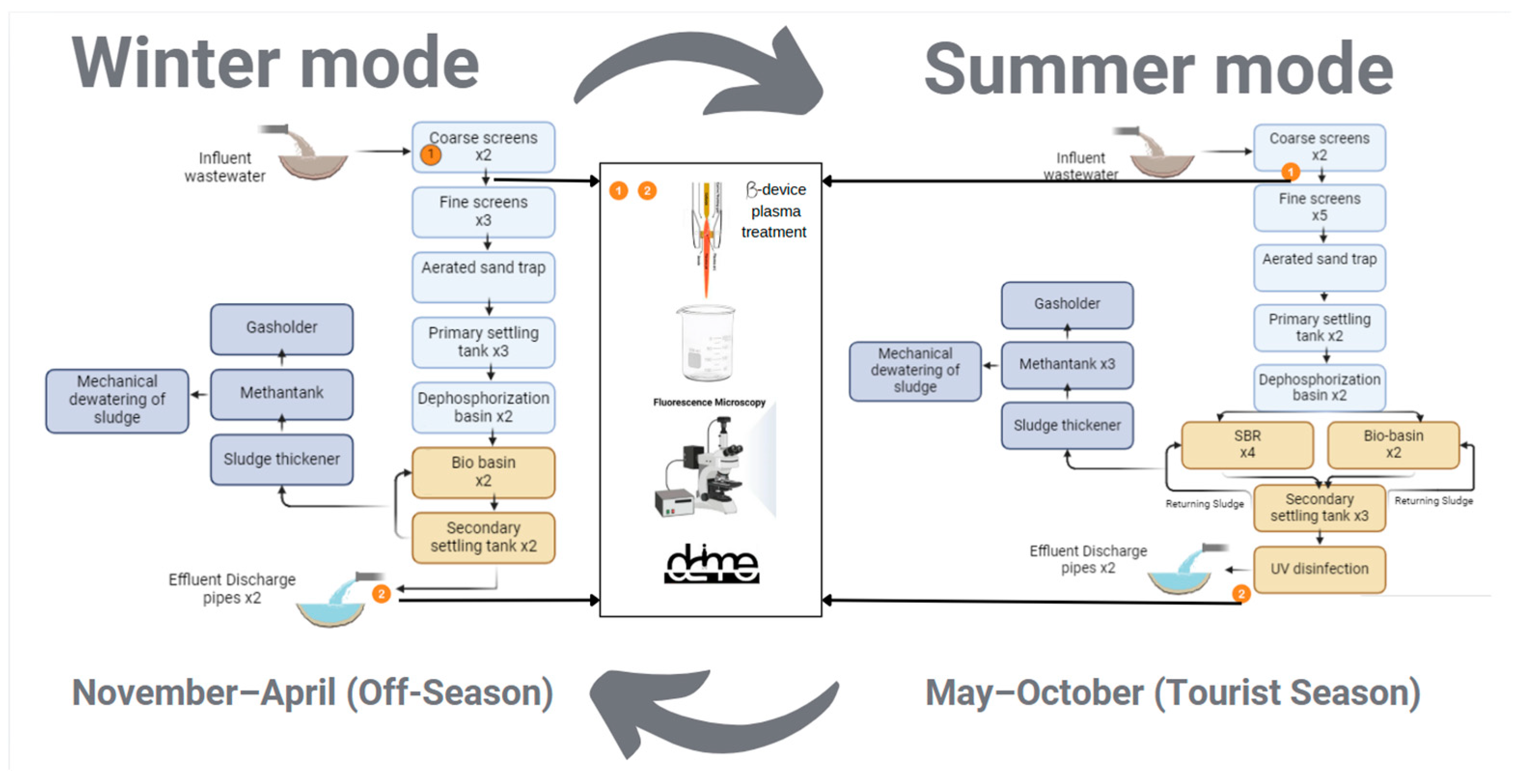

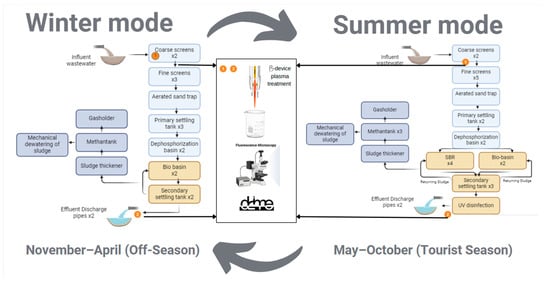

To cope with the different number of tourists/citizens during and after the tourist season, the Ravda WWTP operates with two treatment lines, one with bio-basins and the other with bio-basins and sequencing batch reactors (SBRs). They can be both switched on and off according to their needs, making the process flexible and energy-efficient. Detailed schema of Ravda WWTP with all its facilities is shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3.

Simplified schema of Ravda WWTP in winter (left) and summer (right) with all its facilities and locations of sampling points used for the experiments (orange points).

2.1. Samplings

Water samples were collected from the inflow and outflow of the Ravda wastewater treatment plant during the months of April, August, and November 2024, as shown in Figure 3. It is important to note that in summer there is UV disinfection before the final discharge to the Black Sea, but when taking the samples, the UV was switched off so the results are not affected and easy to compare. The influent and effluent wastewater samples were treated with a cold plasma source under atmospheric conditions for the following purposes:

Treatment of influent waters aimed to enhance oxidative potential prior to their entry into the technological units of the treatment plant, thereby improving the overall purification efficiency. Additional expected outcomes of this pre-treatment included a reduction in the number of pathogenic and opportunistic microorganisms, as well as a decrease in the concentration of toxic micropollutants that could otherwise inhibit the biodegradation activity of microbial communities in the activated sludge within the biotechnological units.

The effluent water samples were also treated with cold plasma under atmospheric conditions. The objective of this post-treatment was to eliminate pathogenic and opportunistic bacteria, particularly those belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae. In parallel, the treatment aimed to remove residual micropollutants that were not degraded during the conventional wastewater treatment process.

These experiments were taken in 2024: one in April prior to the summer tourist season, one in August during its peak and one just after the end of the season in November. In April, the Ravda WWTP was operating in the technologically reduced winter mode scheme shown in Figure 3. In August, all the equipment was switched on and working at full capacity. In November, only one bio-basin was working due to maintenance of the second one. The samples were taken from two critical control points, influent (1) and effluent (2), as shown in Figure 3.

The period from November to April is defined as the off-season, with no tourists and closed hotels. From May to October, tourism is active; May, June, September, and October form the shoulder season with lower visitor numbers, while July and August represent the high season, when hotels operate at or near full capacity.

Previous research shows that the level of BOD5 at effluent is very close to maximum permissioned levels [8]. To meet the future needs of the station and taking into account the continuously growing sector of tourism in the area [57], there is a need to implement new technologies, without expanding the amount of equipment as that would take a long time. That is why, in this research, we have tested the effect of CAP torch on the treatment process.

The experiment was divided into two parts: first, testing the CAP on the metabolic microbial potential, as an indicator of velocity and efficiency of the biodegradation purification process at influent as a possibility to stimulate the treatment process; second, testing the effect of CAP on the bacteria at effluent and their metabolic potential in order to remove the residual contaminants before discharging the water into the Black Sea.

2.2. Microbiological Assays

The wastewater samples of influent and effluent were pre-treated by ultrasonic disintegrator UD-20 automatic (Techpan, Verquigneul, France), in three repeats of 15 s. Then they were serially diluted and plated on Endo Agar (Scharlau, Brit. Phar., Barcelona, Spain), a selective and differential medium for Enterobacteriaceae. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h (±1 h) and then they were subjected to a cytochrome-oxidase test. After 10–30 s, the oxidase positive colonies (Pseudomonades, Aeromonades) were colored in blue, but the oxidase negative bacteria did not change [58,59].

2.3. CTC/DAPI Staining for Analysis of Metabolic Potential

The samples at influent and effluent before and after treatment with CAP were colored with CTC (5-cyano-2,3-ditolyl tetrazolium chloride) and DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) [60]. Then, the samples were observed by excitation with 450–490 nm wavelength for CTC and 340–380 nm wavelength for DAPI on a fluorescent microscope Leica. Images of the fluorescent objects were made at 100× magnification (real image size of 1243 × 932 μm). The images were processed by the software program daime and then analyzed based on the following parameters: mean fluorescent intensity of the images and number of the fluorescent objects. These parameters refer to the formation of clusters of the biological system due to the synergistic and syntrophic relationships of the complex microbial consortia. The intensity (brightness) of objects in the analyzed color images was measured in the daime (Version 2.1) program [60] by taking the maximal intensity of each pixel (voxel) in any color channel. The intensity varies between 0 and 255 depending on the bit depth of the image. As a comparative parameter in this study, the mean intensity of each image was analyzed. The data obtained are average values from the analysis of at least five images. DAPI stains all biological objects, while CTC staining marks only those capable of reducing the tetrazolium salt (CTC) to fluorescent CTC-formazan. Thus, this method differentiates biological objects, cells, clusters, or consortia of cells that exhibit oxidoreductive enzymatic activity and are, to varying degrees, viable and metabolically active. These organisms are therefore considered active participants in the biodegradation processes within the treatment systems.

The bioindicator “metabolic potential” was calculated in two different ways, using the following formulas:

Metabolic potential by number of objects (MPN)

where NCTC is the number of objects (cells and consortia) stained with CTC, i.e., physiologically active organisms, and NDAPI represents the total number of biological entities, both active and inactive.

where FCTC is the fluorescence intensity emitted by physiologically active biological entities, and FDAPI is the signal corresponding to all biological entities—both living and dead.

Thus, the metabolic potential bioindicator is considered a reliable parameter for assessing the biodegradation capacity of microbial clusters or individual cells. In practice, the CTC fluorescence reflects the total dehydrogenase activity, which has been repeatedly shown to correlate directly with the rate of the biodegradation processes occurring in wastewater treatment systems [60].

The percentage of physiologically active units (%PAU) was calculated using the following formula:

where CTC represents the number of physiologically active biological entities (cells or consortia) and DAPI represents the total number of biological entities counted per microscopic image.

This parameter provides a quantitative estimate of the proportion of metabolically active microorganisms within the total microbial population. It allows the differentiation between viable, respiring cells, and inactive or dead cells, thereby reflecting the physiological state and functional capacity of the microbial community. Evaluating the share of active units is essential for understanding how CAP treatment affects microbial viability and metabolic activity, which are key indicators of biodegradation efficiency and the overall biological performance of the wastewater treatment process.

Thus, the metabolic potential bioindicator is considered a reliable parameter for assessing the biodegradation capacity of microbial clusters or individual cells. In practice, the CTC fluorescent labeling measures total dehydrogenase activity, which has been repeatedly shown to correlate directly with the rate of the biodegradation process in wastewater treatment systems [61,62,63].

2.4. Hydrochemical Parameters

From the hydrochemical parameters, the chemical oxygen demand (COD) indicates the organic content in the wastewater and its assimilation during the process has been analyzed. COD was determined using the potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7) method and sample heating in the presence of sulfuric acid (H2SO4) [64]. In addition, the BOD5 was analyzed (according to BDS EN ISO 5815-1:2019) [65]. Total nitrogen (TN) and phosphorus were determined using the standard methodology of the spectrophotometric method with Nova 60, a spectrophotometer, and Merck cuvette tests [66]. The data for total suspended solids (TSSs) was provided by Burgas Waterworks and the Ravda WWTP. Samples were examined in a certified laboratory in the city of Burgas.

The coefficient (K) is an indicator of the biodegradability of organic substances in water. It is calculated as the ratio between the BOD5 for 5 days and COD. This indicator can assess how many hard-to-degrade and nondegradable pollutants are present in the water. It is particularly suitable for evaluating the presence of toxic substances. The formula is as follows:

K = BOD5 ÷ COD

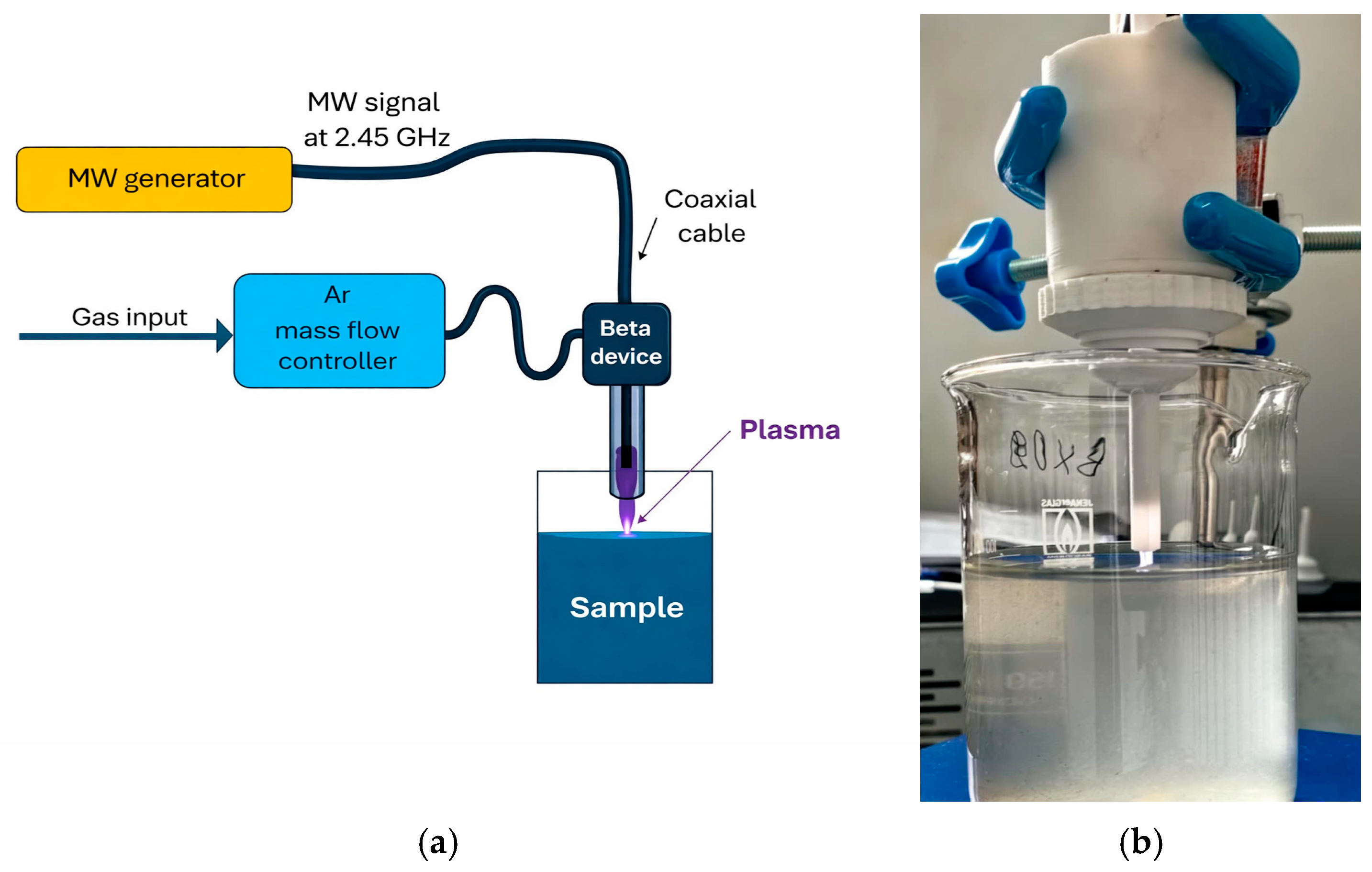

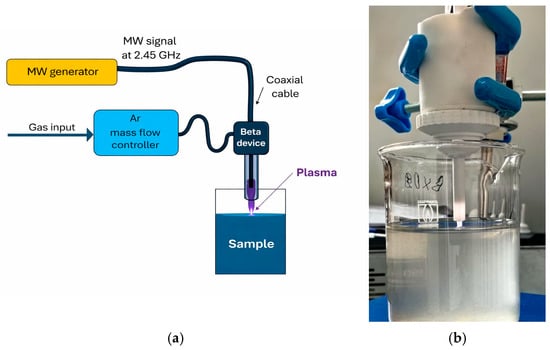

2.5. Cold Atmospheric Plasma Treatment

The plasma source used in this study for liquid samples treatment is a Beta device. It was designed and constructed at the Clean&Circle Center of Competence with the aim of developing a suitable system for producing cold plasma for biological and medical applications. The parameters of the plasma obtained by the Beta device are optimized to allow direct contact of the active plasma with biological objects without any thermal damage. This plasma source uses a solid-state microwave generator (SAIREM, Décines-Charpieu, France) with a frequency of 2.45 GHz connected to the Beta plasma device by a coaxial cable to excite surface electromagnetic wave, sustaining the gas discharge (Figure 4a). In the case of SWD, the applied power is the difference between the generator’s output power and the reflected power. As with the other types of surface-wave-sustained discharges, the operational regime can be optimized so that the reflected power is minimized which guarantees that the wave power is completely absorbed in plasma sustaining. In order to prevent contamination of the samples during the treatment, the plasma torch applicator that is in contact with the objects is disposable. The source allows operation in two treatment modes: underwater mode (when the applicator end is immersed in the liquid samples and the plasma is created inside the liquid) and surface mode (when plasma is in contact with the liquid surface) (Figure 4a). The plasma in both surface and underwater regimes is produced in argon as the working gas, proven to be extremely effective when the plasma needs to be cold and, at the same time, have a high concentration of reactive particles.

Figure 4.

(a) Experimental set-up. (b) Plasma treatment of wastewater samples by the Beta device in surface mode.

Wastewater samples were collected from the influent and effluent of the wastewater treatment plant. They were exposed to argon low-temperature plasma (LTP) generated by the Beta device at 20 W microwave power (at reflected power less than 1 W) with an argon flow rate of 5 L/min. Plasma treatment was applied for 1, 3, and 5 min in a becker glass of 200 mL in the surface mode (Figure 4b). Following treatment, samples were serially diluted and plated on Endo agar to isolate Enterobacteriaceae.

While the results clearly demonstrate the potential of cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) treatment in improving the microbiological and physicochemical quality of wastewater, certain limitations should be acknowledged. The experiments were conducted ex situ under controlled laboratory conditions, which allowed for precise parameter control but did not fully reproduce the dynamic environment of full-scale treatment systems. In addition, the effluent water used for CAP testing had not undergone prior plasma pre-treatment, and conversely, the influent samples treated with CAP were not subsequently subjected to biological processing within the wastewater treatment plant, as pre-treatment and post-treatment were evaluated independently. These constraints limit the direct extrapolation of the findings to operational conditions. Nevertheless, the results obtained provide valuable proof-of-concept evidence for the efficiency and environmental relevance of CAP as a complementary step in wastewater treatment, forming a solid foundation for future pilot-scale and in situ applications.

All the analyses were made in three independent replicates. The results and standard deviations were calculated with the software product SigmaPlot 11 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Statistical analysis was performed using a t-test in Sigma Stat (version 4.0). Differences were considered statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level.

3. Results

The Ravda WWTP operates from November to April under a reduced-load regime, treating smaller volumes of wastewater, as this period falls outside the peak tourist season. During this off-season, the volume of treated wastewater is approximately 340,821 m3 per month, which is almost three times lower than that treated during the active tourist season in August. Given the relatively small permanent population served by the Ravda WWTP, these seasonal differences are operationally significant. During the off-season, the inflow is so reduced that nearly half of the treatment equipment is taken offline, whereas in the tourist season, the plant must operate at full capacity to accommodate the sharply increased hydraulic and pollutant load. In addition to the higher volume, the pollutant load of the wastewater is 2.5 to 3 times greater during the tourist season compared to the off-season. Although we did not quantify individual contaminants, we used metabolic potential assays (MPN/MPF by CTC/DAPI) as integrative bioindicators of measuring the complex toxicity, an approach which has been successfully applied in studies of chemically stressed, activated sludge communities and aquatic microbial ecosystems [41].

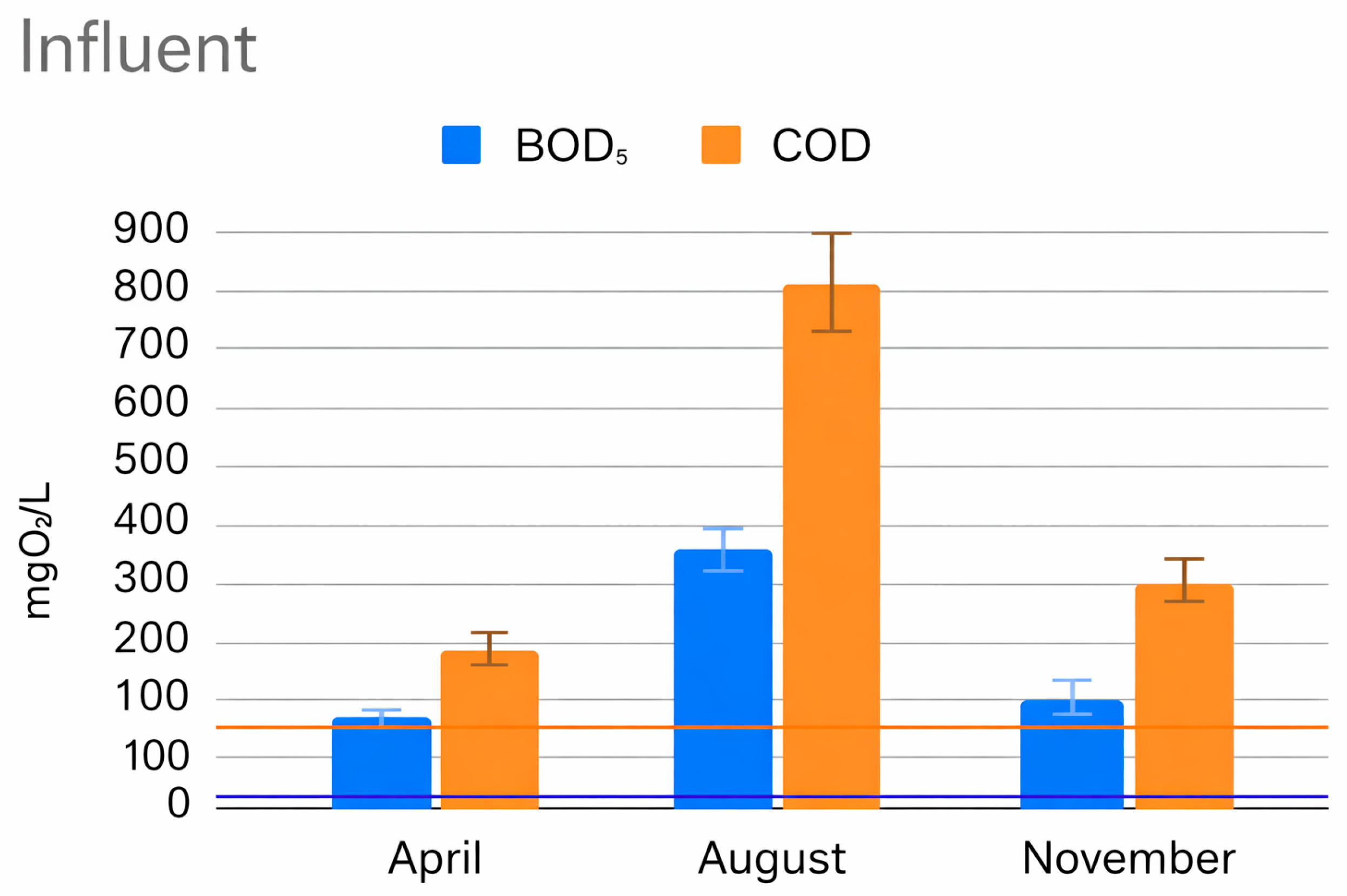

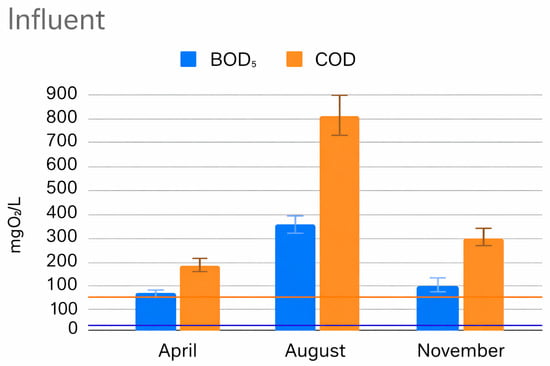

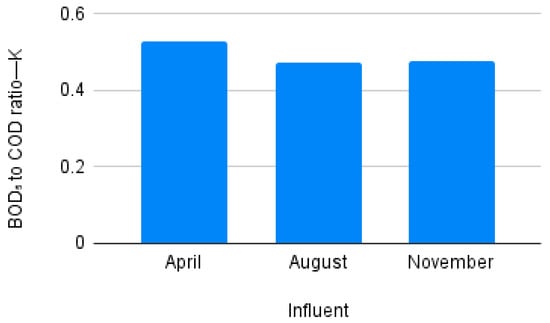

3.1. Pre-Treatment of Wastewater at the Influent of the Ravda WWTP

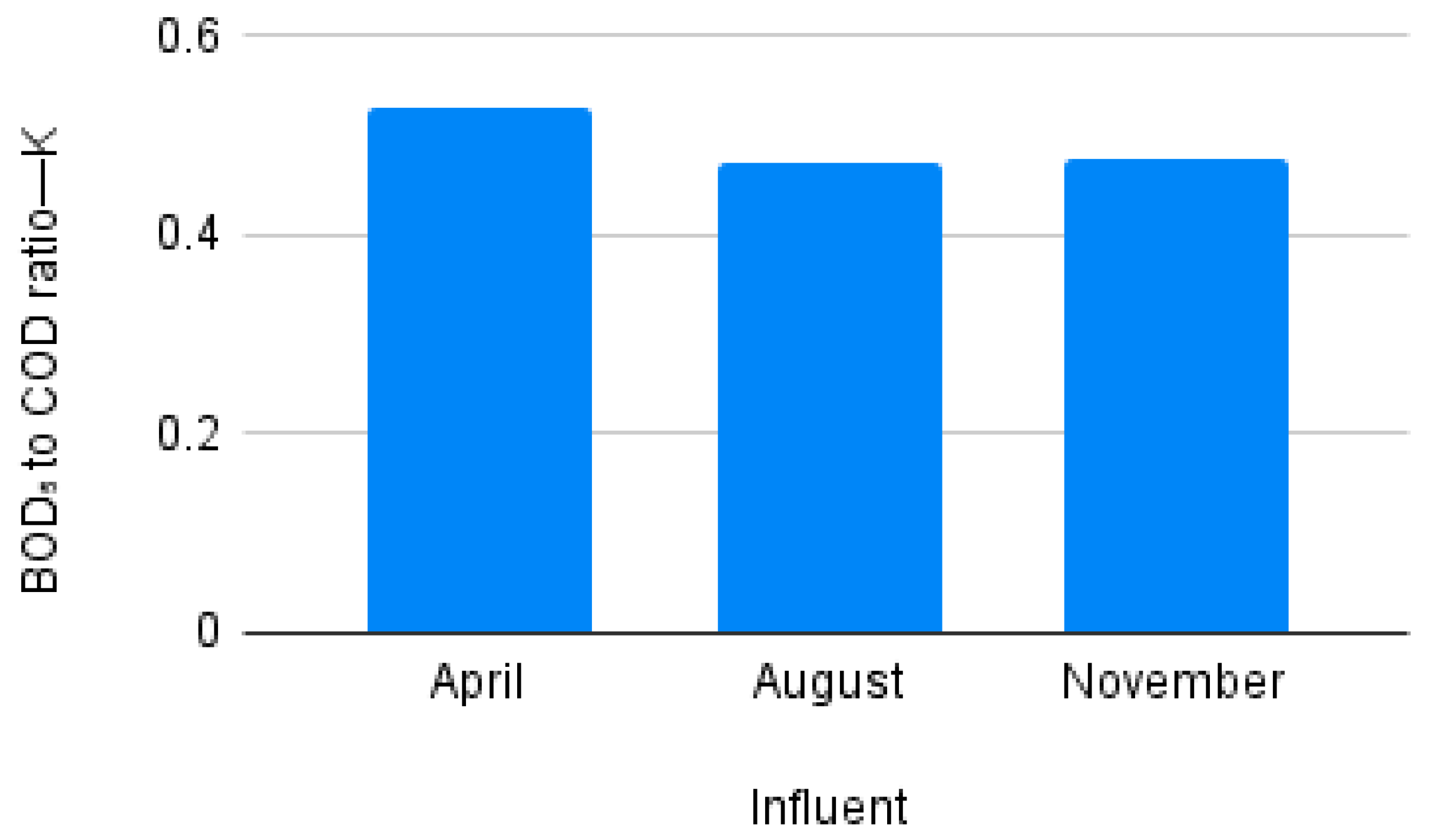

The data on the organic load, expressed as COD and BOD5, are presented in Figure 5. The BOD5/COD ratio, shown in Figure 6, which serves as an indicator of the biodegradability of pollutants, is 0.46 and 0.43 during the off-season, decreasing to 0.42 in August, which is the peak of the tourist season. This trend indicates that in addition to the volume and load of the wastewater streams being strongly influenced by tourism-driven pollution, the proportion of poorly biodegradable contaminants also increases.

Figure 5.

BOD5 and COD at influent with maximum permissible level of discharge for BOD5 (blue line) and COD (orange line) (Source: complex permit of the Ravda WWTP).

Figure 6.

BOD5 to COD ratio—K at the WWTP influent.

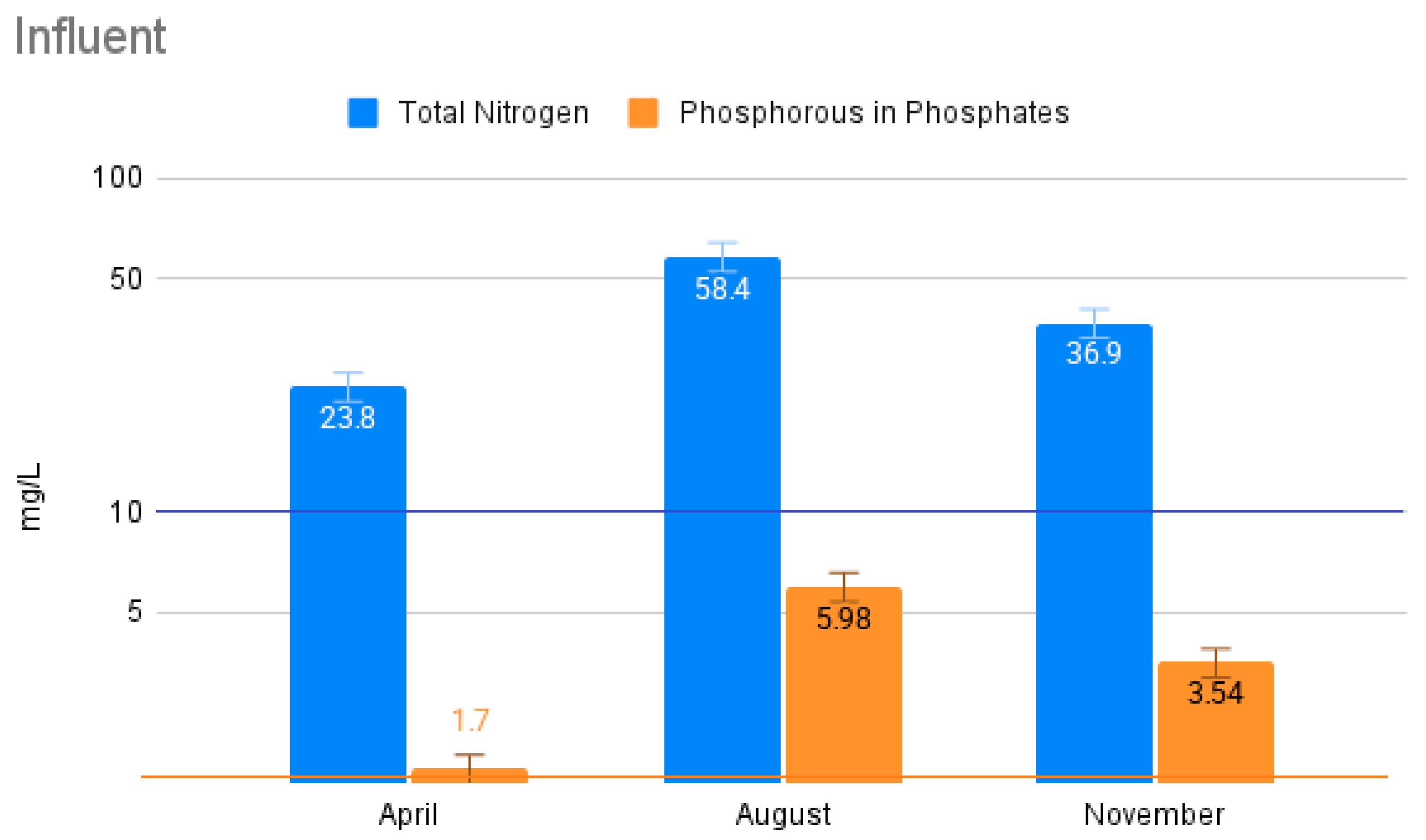

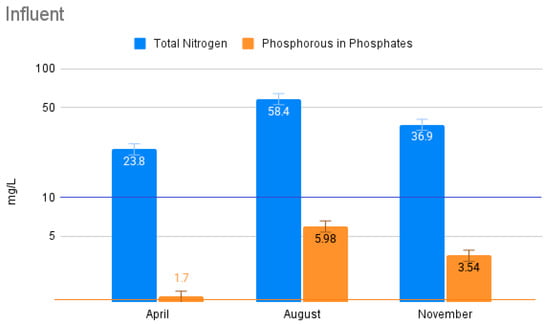

The amount of nitrogen in influent water, shown in Figure 7, varies between 23.8 and 58.4 mg/L with highest amount recorded in August (the peak of the tourist season). This is explained by the higher domestic wastewater production, especially from hotels, restaurants, and recreational facilities that are usually closed in winter. This also correlates with higher organic load which supports the interpretation that the plant experiences significant seasonal hydraulic and organic overloading during the tourist season. In addition, it is important to emphasize that in wastewater systems, higher TN often co-occurs with higher microbial loads (because both originate from increased human activity), so the trend is plausible and internally consistent.

Figure 7.

Total nitrogen (TN) and phosphorous in phosphates in wastewater at inlet with maximum permissible level of discharge for TN (blue line) and phosphorous in phosphates (orange line).

The phosphorus in phosphates, marked in orange in Figure 7, indicates concentrations between 1.7 and 5.98 mg/L, and peaks again in August, following the same seasonal pattern observed for nitrogen. These observations are logical, given that hotel and tourism activities are associated with the intensive use of disinfectants, pesticides, preservatives, detergents, dyes, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical products, including antibiotics, steroid hormones, and microplastics.

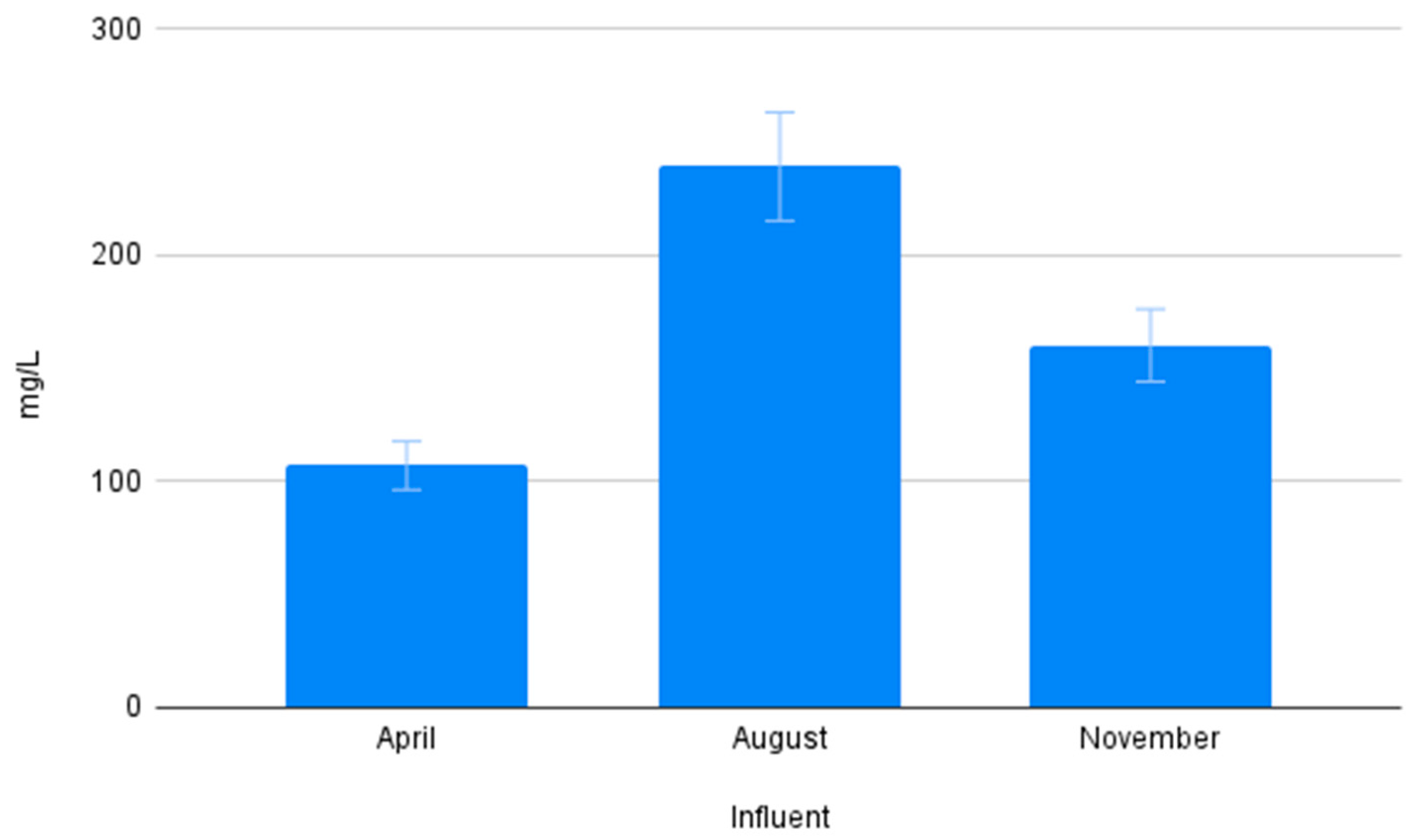

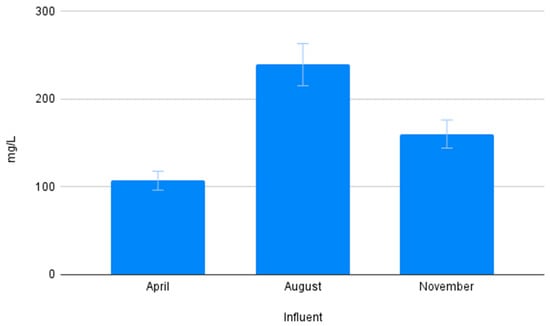

The TSS concentrations at the WWTP inlet, shown in Figure 8, also demonstrate a distinct seasonal pattern that parallels the trends observed for nitrogen and phosphorus. They were lowest in April and increased markedly during August; they declined again by November, showing significant seasonal stress, strongly influenced by tourism-driven fluctuations.

Figure 8.

Total suspended solids at inlet.

A critical group of contaminants during the tourist season is pathogenic and opportunistic microorganisms, particularly those originating from the gastrointestinal tract of humans and domestic animals—members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. These factors collectively impair and reduce the efficiency of the wastewater treatment process.

For this reason, the search for innovative approaches to the pre-treatment of influent wastewater streams has become increasingly important. The purpose of CAP treatment is, on one hand, to reduce the toxicity of the incoming water, and on the other, to decrease the abundance of pathogenic and opportunistic bacteria. However, the primary objective is to evaluate the effect of CAP treatment on the oxidative and metabolic potential of the influent water, thereby aiming to accelerate and enhance the biological removal of pollutants within the facilities and bioreactors of the Ravda WWTP.

The monitoring of plasma-treated wastewater characteristics in our experiments was carried out by assessing changes in the metabolic potential (MP) of the waters and the restructuring of their microbial communities, distinguishing between the activation or inhibition of the microorganisms present in the wastewater.

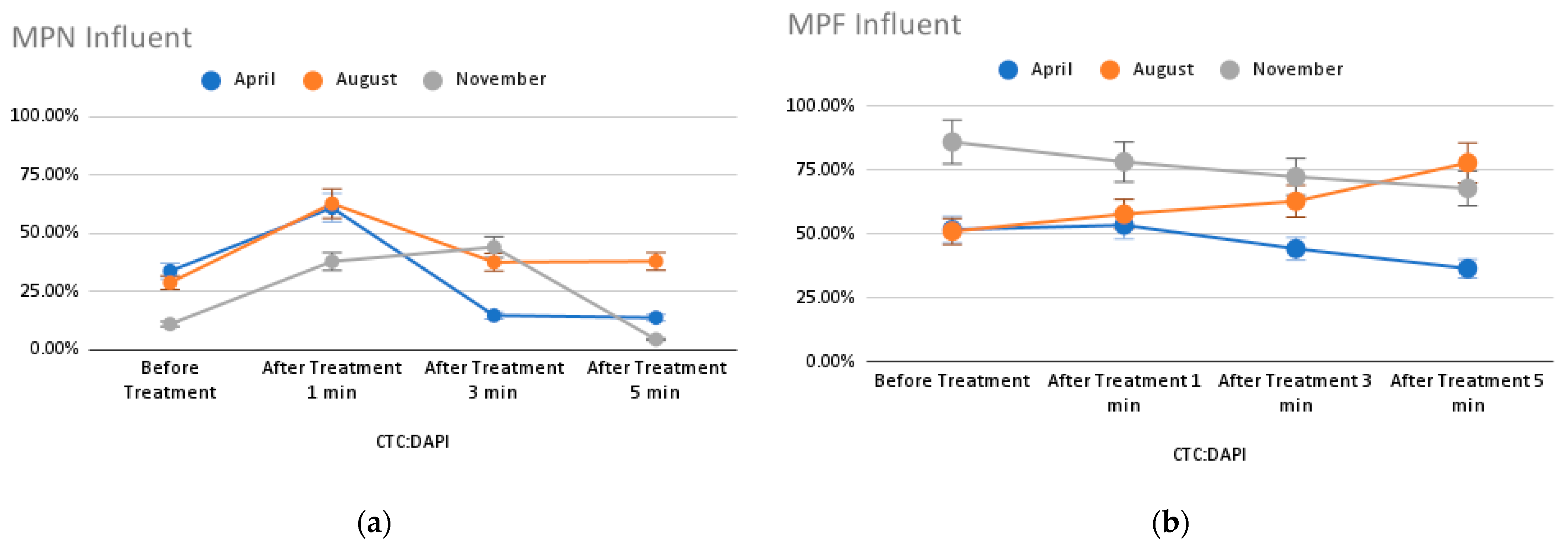

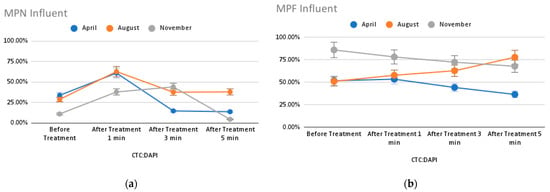

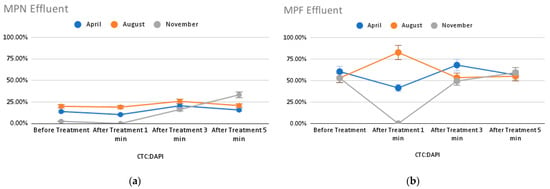

The CTC/DAPI ratio (MP), shown in Figure 9a, represents an index of metabolic activity, or in other words, the proportion of viable cells. According to literature data, a high percentage (80–100%) indicates that most cells are metabolically active, whereas a low percentage (10–20%) suggests that a large fraction of the cells is inactive, stressed, or dead [24].

Figure 9.

Dynamics of metabolic potential variation by number of objects (a) and by mean intensity of fluorescence (b) in the influent.

In this study, for the influent samples (Figure 9a), the highest number of active cells was found after 1 min of CAP treatment. A decline was recorded after 3 and 5 min, a trend that was consistent for the April and August samples. In November, the highest metabolic potential was noted following 3 min of treatment, while the lowest was detected after 5 min of plasma exposure.

The fact that the percentage of viable biological entities was highest in April and August after CAP treatment suggests an additional important conclusion. Under such short exposure times, the effect of cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) on metabolic potential (MPN) appears to be stimulatory, most likely due to a combination of plasma-induced processes—including the breakdown of suspended organic matter, detachment of microbial biofilms and microorganisms from surfaces, removal of biofilms from inorganic suspended particles, disruption of existing microbial clusters, increased availability of organic substrates to suspended bacteria, and reduction in water toxicity through the degradation of toxic pollutants. Together, these simultaneous processes lead to an increase in the proportion of physiologically active microorganisms, reaching 60.91% in April and 62.72% in August. This indicates that short CAP exposure (1 min) is suitable for the activation of microbial metabolic potential (MPN). The higher number of active suspended microorganisms and smaller microbial clusters create favorable conditions for biofilm development in grit chambers and for the stimulation of biodegradation processes even in the initial physical treatment units. It should be noted that biofilm-based microbial communities are generally more effective in biodegradation, as these processes occur under higher concentration gradients of substrates, pollutants, enzymes, cofactors, etc.

In November, plasma had the opposite effect on MPN, because the organics were more easily biodegradable (higher K). In this case, the microbial community can tolerate and even benefit from a slightly longer CAP exposure (3 min), where partial oxidation and PAW species may improve substrate availability and stimulate metabolism (MPN peak at 3 min). At 5 min, oxidative stress becomes dominant and metabolic activity drops sharply. In April, with lower load and relatively less biodegradable organics (lower K), even short CAP exposure (1 min) gave a brief stimulatory effect, but longer exposures (3–5 min) more quickly shifted the balance toward inhibition.

Another expected stimulatory effect on the overall treatment process is the reduction in toxic pollutants and overall water toxicity. The elimination of toxic contaminants begins as a physically plasma-induced process, but continues through the action of activated biofilm microorganisms in the grit chambers and bioreactors. An additional benefit of this detoxification in the initial treatment units is the preservation of the active sludge in the bioreactors, allowing it to function more efficiently under reduced or absent toxic pressure.

These findings indicate that 1 min of plasma pre-treatment is suitable for increasing the microbial metabolic potential (MPN), which can positively influence the overall wastewater treatment efficiency at the Ravda WWTP. Such a pre-treatment act as a mechanism for accelerating purification during periods of heavy pollution load.

When exposed for 3 min, MPN values decreased in April and August, but remained relatively high in November after a 3 min treatment. Conversely, 5 min plasma exposure led to a reduction in MPN across all sampling months of influent analysis. It is evident that longer plasma exposure is accompanied by damage to biological structures—both individual cells and microbial clusters—and is therefore not suitable for activating wastewater treatment processes or for enhancing the operational efficiency of the treatment plant [40].

Of particular interest is the effect of plasma treatment for 1, 3, and 5 min on MPF, i.e., its measurement based on fluorescence intensity. This indicator serves as an analog of total dehydrogenase activity, reflecting overall enzymatic activity within the microbial community [24,30]. As shown in Figure 9b, during April and November, when organic loading is lower and the K coefficient is higher, the MPF values decreased with increasing plasma exposure time. This is most likely due to the fact that plasma-generated particles, both short- and long-lived, exert an inhibitory effect on total dehydrogenase activity, particularly the oxidative species that interact with hydrogen cations, thereby reducing their flow through the electron transport chains.

The relationship between MPF values and plasma treatment duration was only directly proportional in August, when the organic load was high. The high organic loading is associated with greater abundance of hydrogen cations, which move through the electron transport chains of the living microbial entities in the influent. This likely mitigates the inhibitory effects of longer plasma exposure on both the total dehydrogenase activity and the corresponding MPF values.

In August, the MPN increased by 117.4% after 1 min of plasma treatment, while the MPF increased by 13.28%. When considered together, these results suggest that 1 min exposure is an optimal duration for stimulating wastewater treatment efficiency under high organic loading conditions, which are typically accompanied by elevated concentrations of toxic compounds and, consequently, a lower K coefficient. In this study, such conditions correspond to the heavy pollution load observed in August.

A 1 min plasma treatment also proved suitable during April and November, when the wastewater load was lower, corresponding to the off-tourist season. The increases in MPN and MPF during these months were 80.2% and 3.34% in April, and 241.56% and 9.05% (decrease) in November, respectively. These findings indicate that short plasma exposure effectively enhances microbial activity and biodegradation potential across different seasonal conditions, though the response intensity varies depending on the organic and toxic load of the influent.

As an intermediate conclusion, it can be stated that a 1 min treatment with the Beta device represents an optimal duration for accelerating the overall purification process within the facilities of the Ravda Wastewater Treatment Plant. This treatment has a positive effect on both parameters of the metabolic potential—MPN and MPF—enhancing microbial activity and contributing to improved treatment efficiency.

The specific data on the percentage increase or decrease in the metabolic potential (MP) according to the parameters MPN and MPF are presented in Table 1. The table also indicates the optimal treatment regimes (in red), taking into account all observed relationships and parameters, and is based on the combined analysis of metabolic potential indicators and the number of culturable microorganisms from the family Enterobacteriaceae.

Table 1.

Percentage change in object count and fluorescence intensity relative to control (influent).

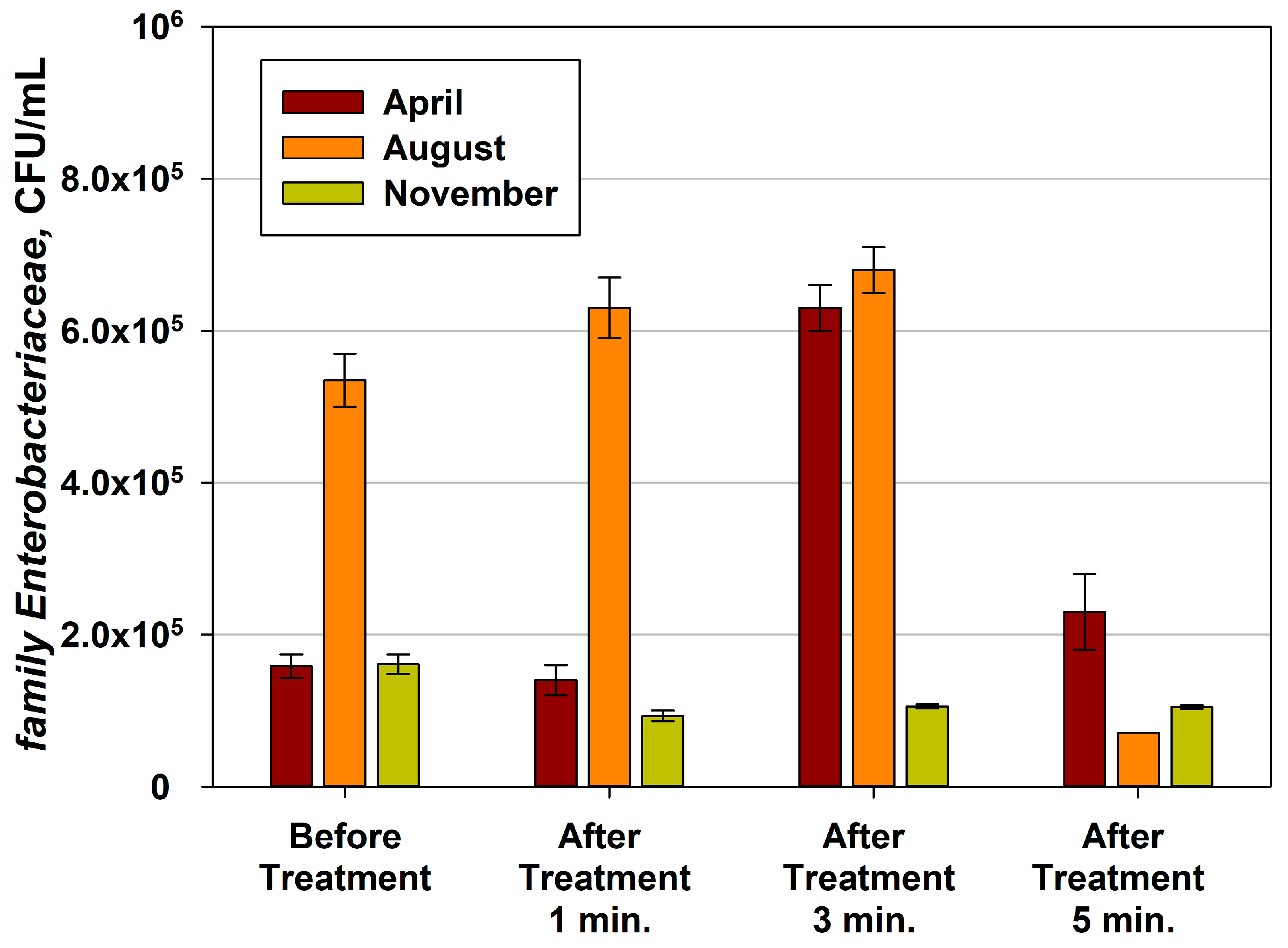

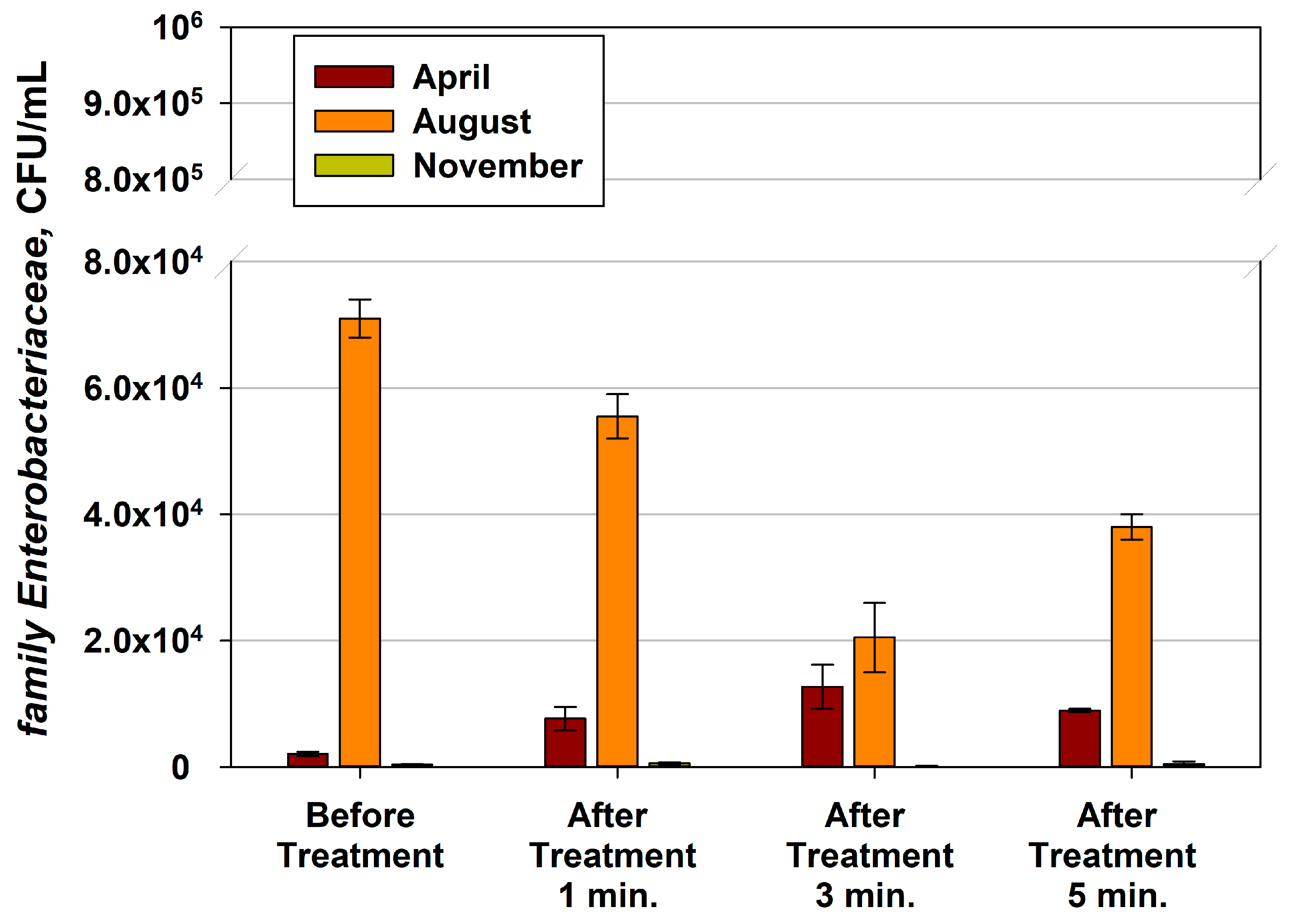

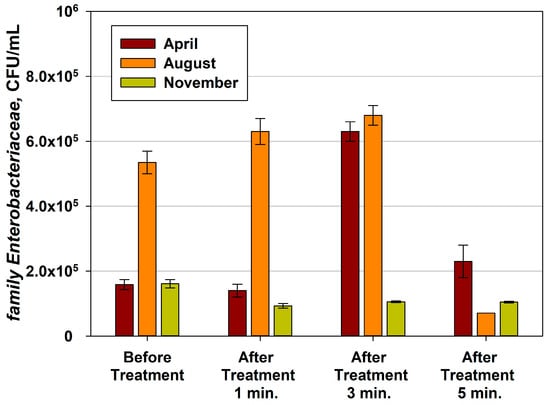

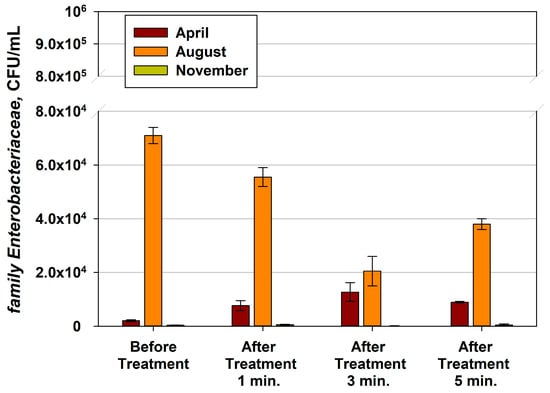

In parallel with the assessment of the overall metabolic potential measured by DAPI and CTC staining, the abundance of bacteria from the family Enterobacteriaceae was also investigated using a culture-based method. The results are shown in Figure 10 below. This approach enabled the analysis of only the culturable bacteria within this family, which play a key role in the epidemiological evaluation of wastewater quality.

Figure 10.

CFU/mL Enterobacteriaceae before and after treatment with plasma at influent.

The presented results clearly show that during 1 and 3 min plasma treatment of the influent, across the three sampling months, the quantity of Enterobacteriaceae either remained unchanged (as in the 1 min treatment in April) or increased. The most pronounced and consistent increase was recorded in August, when both the organic and microbiological loads were highest, and the bacterial counts rose proportionally with the duration of treatment.

In the April influent, an unexpectedly high abundance of enterobacteria was detected after 3 min of CAP exposure. Although April belongs to the off-season, this sample is characterized by lower overall organic loading and a higher BOD5/COD ratio compared to November, indicating pollutants that were less difficult to degrade. Our assumption is that the 3 min CAP treatment induces desorption of bacteria from the suspended particles and disrupts bacterial aggregates. This results in more homogeneous cells, leading to a higher number of colony-forming units of microorganisms, including bacteria from the family Enterobacteriaceae.

This increase in Enterobacteriaceae abundance within the influent, as part of the overall bacterial complex, could in fact have a positive effect on the subsequent treatment stages. Upon entering the grit chambers and bioreactors, these bacteria—often not integrated into activated sludge flocs—could serve as an easily available and abundant food source for the micro- and meta-fauna, thereby supporting the maintenance of a balanced and active activated sludge structure. These key participants in the treatment process would benefit both from the readily available organic substrates and from the reduced inhibitory impact of complex toxic contaminants.

3.2. Post-Treatment of Wastewater at the Effluent of the Ravda WWTP

The aim of this part of the study was to apply a cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) treatment regime to the purified effluent in order to evaluate the feasibility of incorporating plasma modules within the wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) as a form of tertiary treatment. The same parameters previously discussed for CAP pre-treatment were again monitored, including effluent quality indicators such as COD and BOD5, and the economic coefficient (K), which reflects the presence of residual toxic and poorly degradable pollutants. In addition, the changes in metabolic potential (MPN and MPF) were tracked, and culturable bacteria from the family Enterobacteriaceae were quantified to assess the microbiological impact of plasma post-treatment.

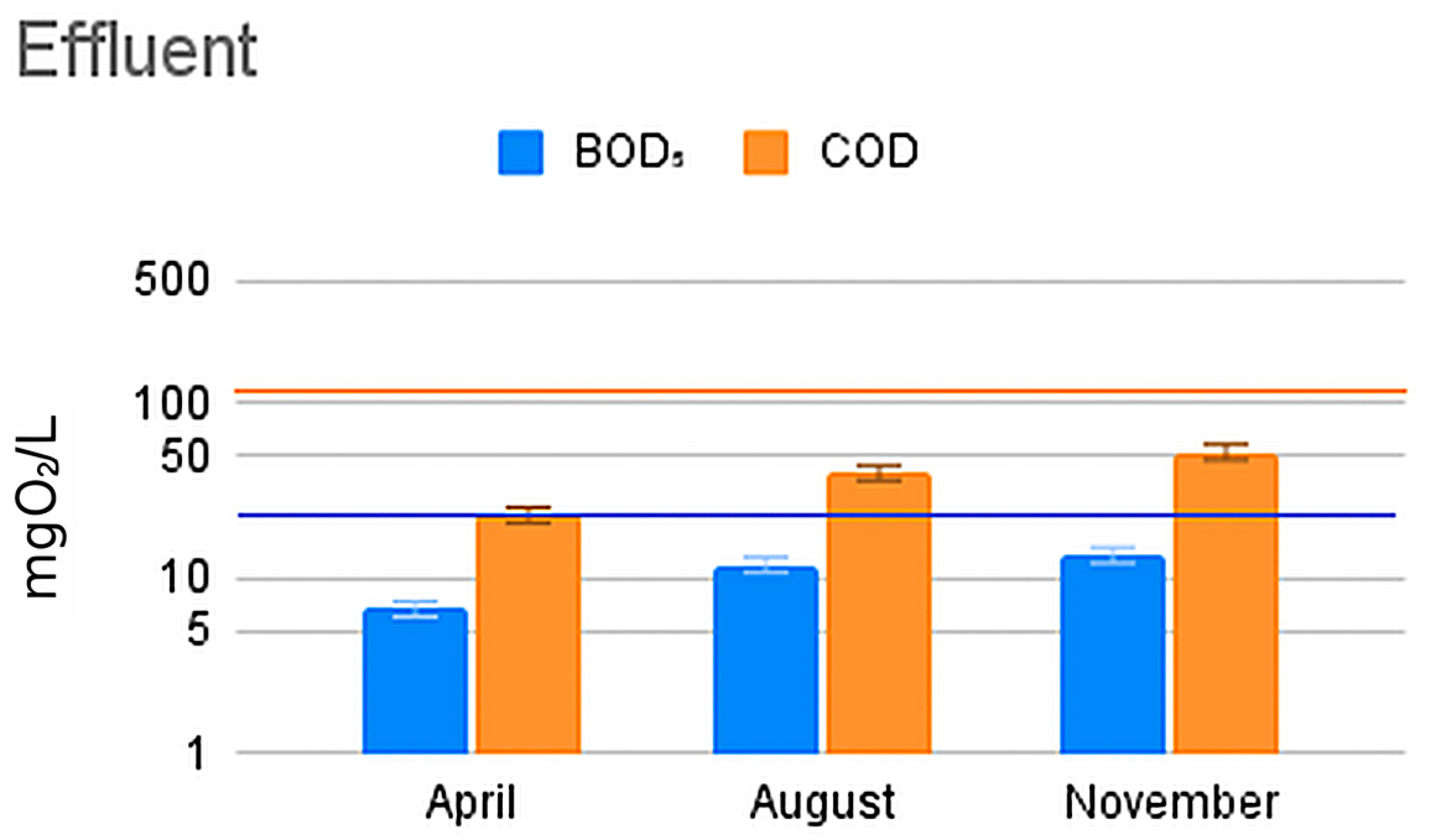

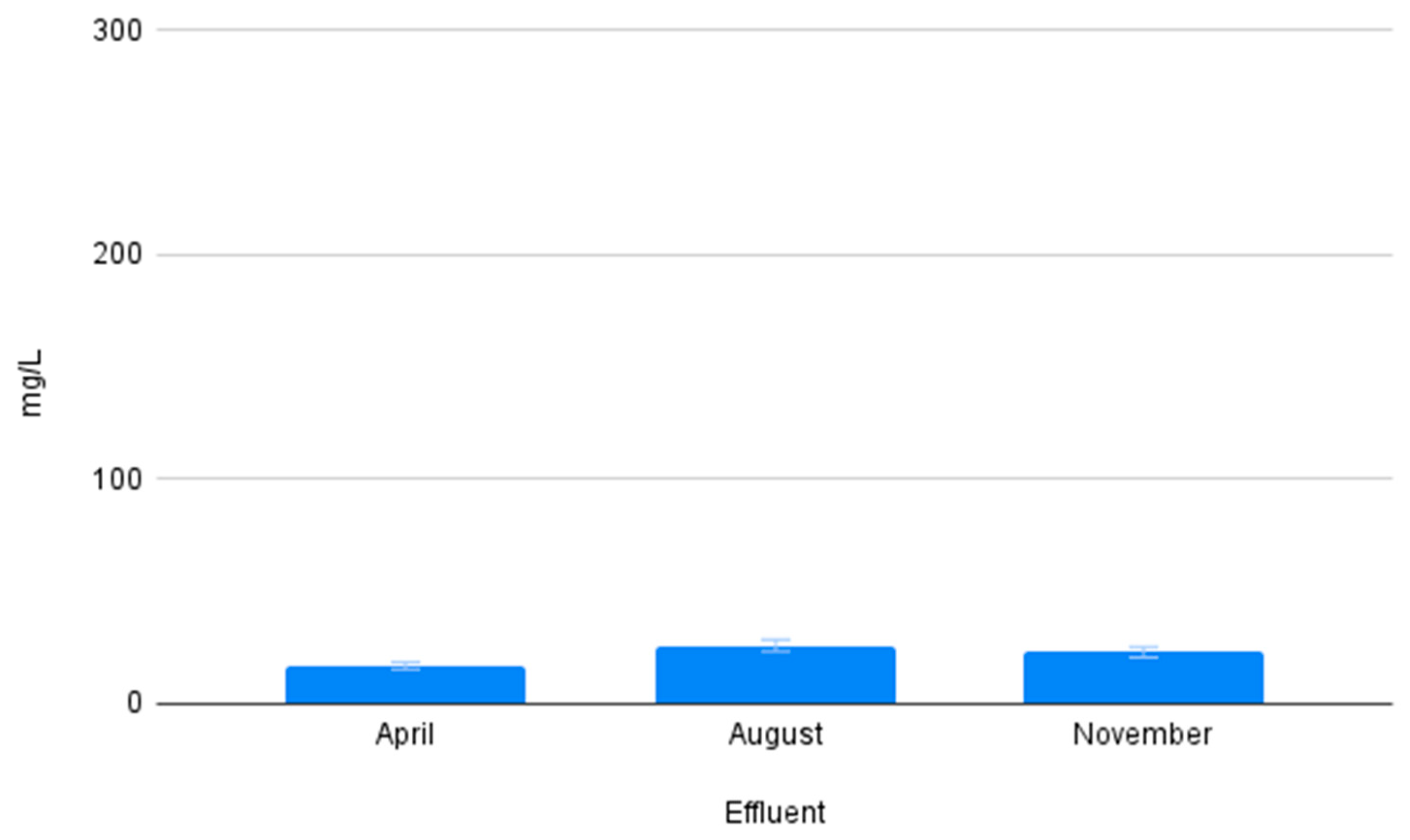

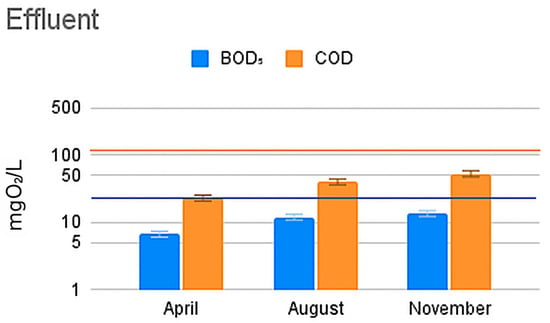

The results concerning the chemical parameters of the effluent are presented in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

BOD5 and COD at effluent with maximum permissible level of discharge for BOD5 (blue line) and COD (orange line) (Source: complex permit of the Ravda WWTP).

According to the standards of the Republic of Bulgaria, the maximum permissible level of COD in treated wastewater is 125 mgO2/L and 25 mgO2/L for the BOD5. In this case, the samples meet these requirements as shown in Figure 11. The highest COD and BOD5 are recorded in November, due to the maintenance of the equipment. On the day the samples were collected, only one bioreactor was in operation, which led to an increased load on the activated sludge, thereby reducing the overall treatment efficiency. Nevertheless, the effluent parameters remained within acceptable limits and did not pose a risk to the Black Sea ecosystem upon discharge. However, previous studies show that in extreme conditions (very high touristic load), COD and BOD5 are very close to the limits [8], which is visible in Figure 12.

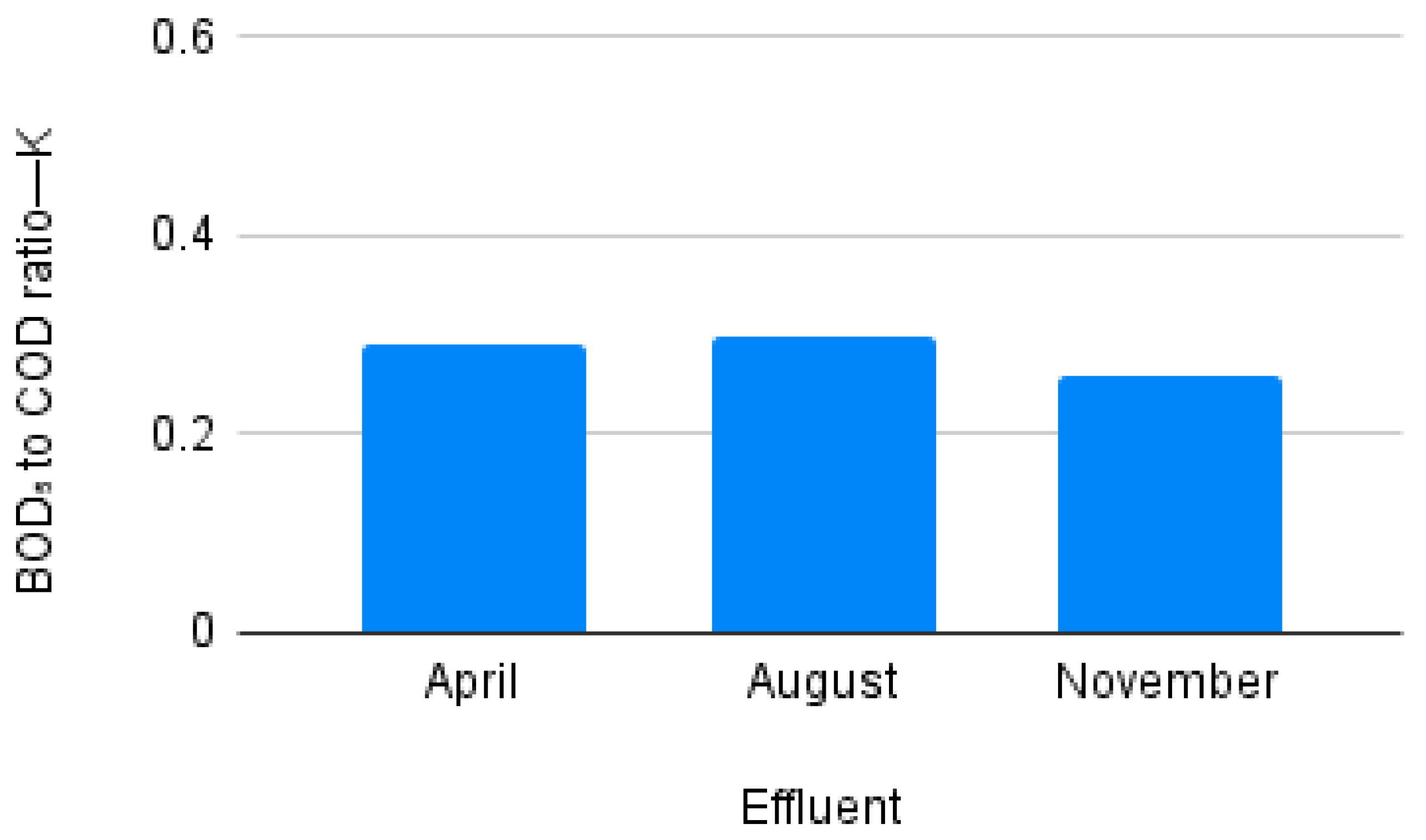

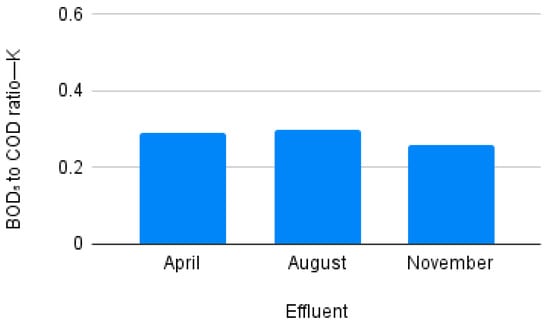

Figure 12.

BOD5 to COD ratio—K at the WWTP effluent.

It is clearly evident that in all three sampling months, the chemical parameters reflecting effluent quality remain within the regulatory limits for discharge into receiving waters [7,8]. The economic coefficient (K) is almost twice as low compared to that of the influent. On one hand, this reflects the effective purification process achieved in the WWTP; on the other, it indicates that while the readily degradable organic matter is efficiently removed during treatment, the toxic component persists in the effluent after the biological stage. This highlights a well-recognized limitation of conventional wastewater treatment systems, particularly in coastal regions serving marine tourist complexes, where even treated waters may still contain residual toxic pollutants. Although these compounds may not be fully captured by standard COD measurements, they can negatively affect aquatic ecosystems or limit the potential for water reuse [5,8]. For this reason, the testing of alternative and innovative tertiary treatment methods, such as cold atmospheric plasma (CAP), represents a promising direction for further development.

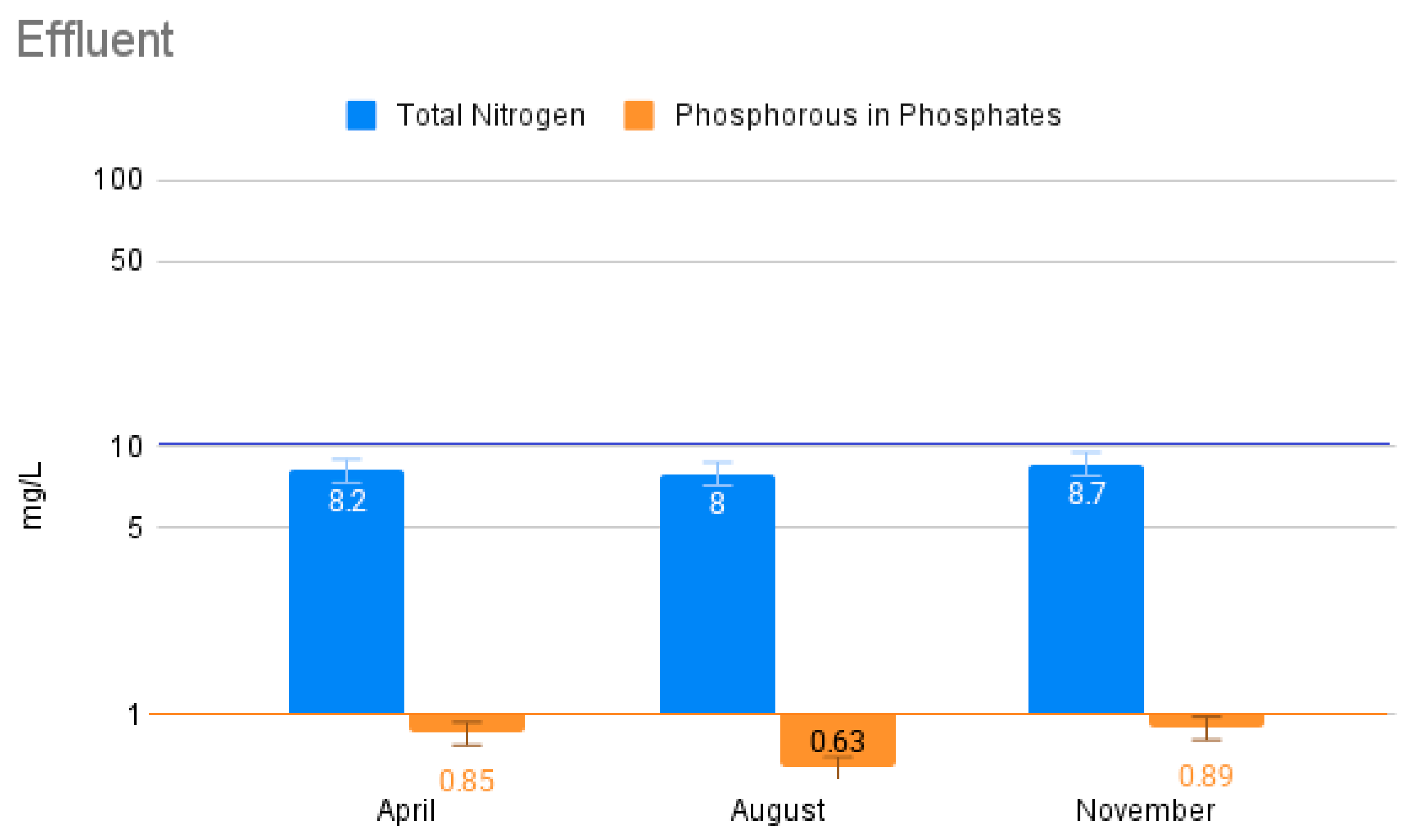

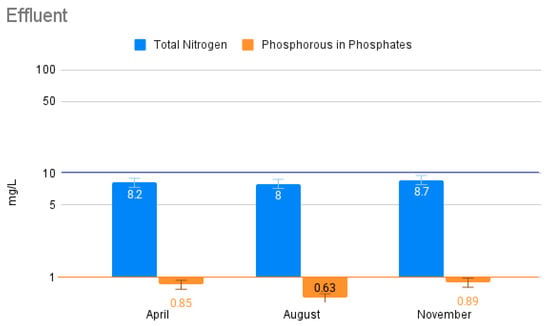

Figure 13 illustrates the concentration of TN and phosphorus in phosphates in the effluent with their maximum permissible levels as follows: 10 mg/L for TN and 1 mg/L for phosphorus, based on the individual complex permit of the exanimated WWTP Ravda.

Figure 13.

Total nitrogen and phosphorous in phosphates in wastewater at outlet with maximum permissible level of discharge for TN (blue line) and phosphorous in phosphates (orange line).

TN values remained relatively stable (8.2 mg/L in April, 8.0 mg/L in August, and 8.7 mg/L in November), indicating that the biological treatment processes were able to accommodate the seasonal rise in nitrogen loading without deterioration of performance. Similarly, phosphorus in phosphates (0.85 mg/L in April, 0.63 mg/L in August, and 0.89 mg/L in November) stayed well within the allowable limit of 1 mg/L. When compared with the substantial seasonal increases observed in the influent, the effluent data confirm that the WWTP provides a stable and compliant level of nutrient removal throughout the year.

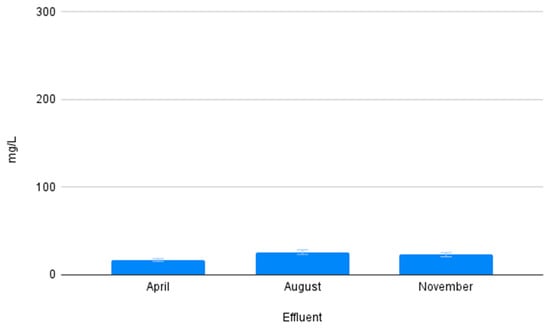

The concentrations of TSS in the treated effluent, shown in Figure 14, remained consistently low throughout all sampling periods with only minor variation between months. This stability indicates that the WWTP’s clarification and filtration processes perform reliably even under conditions of increased hydraulic and organic loading during the tourist season, that otherwise contribute to turbidity, residual contamination, and potential microbiological risk in the discharged water. This is a favorable baseline for assessing the additional benefits of plasma treatment.

Figure 14.

Total suspended solids at outlet.

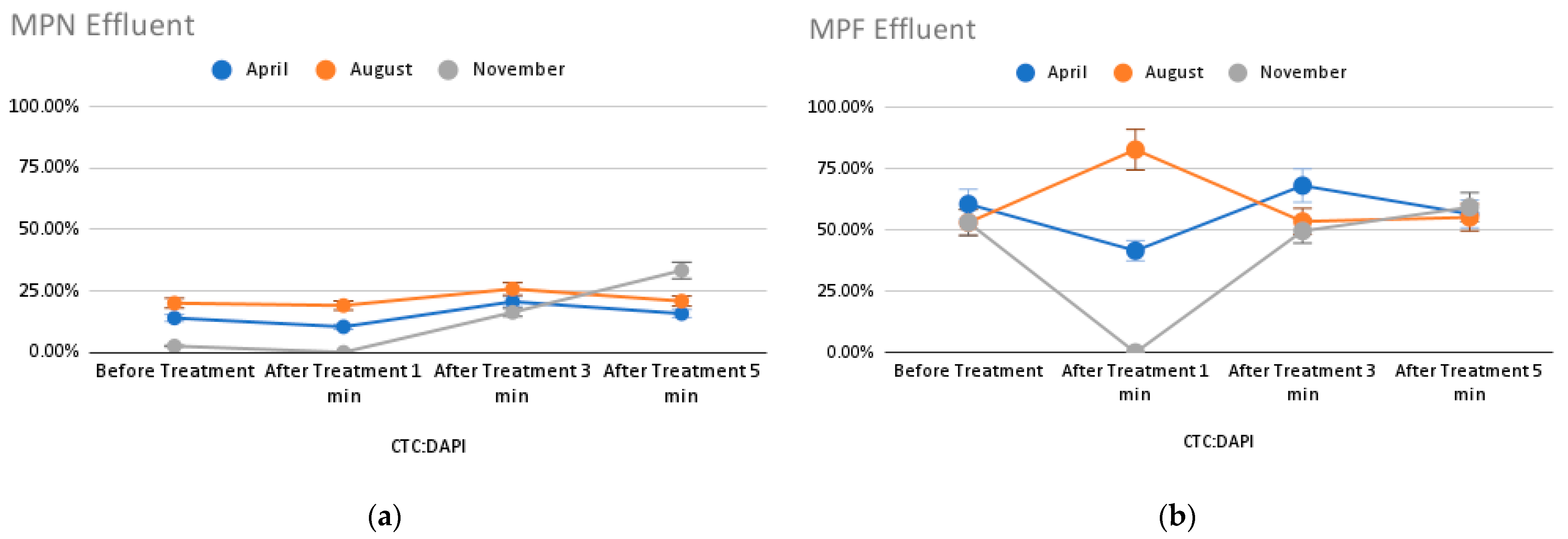

In this context, beyond detoxification, plasma treatment also contributes to disinfection, leading to the elimination of pathogenic and opportunistic bacteria [67]. Figure 15 presents the dynamics of metabolic potential changes, expressed by both MPN (a) and MPF (b), across the different months of sampling and as a function of plasma treatment duration.

Figure 15.

Dynamic of metabolic potential variation by number of objects (a) and by mean intensity of fluorescence (b) in the effluent.

The data presented in Figure 15 clearly show that the MPN values in the effluent were almost twice lower than those measured in the influent. Plasma stimulation had only a minor or negligible effect on the number of physiologically active biological entities, which, although fluctuating with treatment duration, remained within similarly low ranges. Several factors likely contribute to this outcome. The absence of a significant increase after treatment indicates that the effluent primarily contains individual microbial cells rather than cell consortia. Moreover, the lack of organic and inorganic suspended matter after the completion of the treatment process prevents biofilm formation and the detachment of bacteria from such structures, which could otherwise elevate MPN values. The only exception was an increase in MPN observed after 3 and 5 min treatments in November, when the treatment performance at the Ravda WWTP was compromised, which was reflected in the MPN dynamics.

The variation in MPF with plasma exposure time showed an increase in microbial activity after a 1 min treatment in August, and a decrease in April and November. The increase observed in August corresponds with a higher K coefficient, indicating lower water toxicity. The reduction in inhibitory pressure on microorganisms likely resulted in enhanced metabolic activity, which could have a beneficial effect once the treated waters are discharged into the Black Sea, as the self-purification processes in the marine environment would be further stimulated. Conversely, in April and November, the metabolic fluorescence potential (MPF) decreased after a 1 min treatment, but increased slightly after 3 and 5 min exposures, remaining close to the control values.

The specific percentage changes in the metabolic potential (MP) according to both parameters (MPN and MPF) are presented in Table 1. The table also identifies optimal plasma treatment regimes, taking into account all dependencies and parameters, and is based on the integrated analysis of MP values and the number of culturable Enterobacteriaceae.

Table 2 illustrates the changes in the number of all bacteria in the effluent after various durations of cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) treatment. In April and August, the abundance of bacteria generally increased across all three exposure times, with minor exceptions where the counts remained almost unchanged (e.g., after 1 and 5 min treatments in August).

Table 2.

Percentage change in object count and fluorescence intensity relative to control (effluent).

From the results presented in Table 2, the following intermediate conclusions can be drawn. A 1 min CAP post-treatment of the effluent resulted in a slight decrease in MPN (i.e., the number of metabolically active cells) across all three months, a moderate increase in MPF in August, and a reduction in MPF in April and November. Under this treatment regime, a slight decrease was observed in the number of culturable Enterobacteriaceae in August and November (Figure 16). Therefore, a 1 min plasma exposure could only be considered suitable if the objective is to enhance the MPF during periods of high organic loading (e.g., in August), thereby potentially stimulating the self-purification capacity of the receiving water body. However, given the low abundance of physiologically active biological entities in the effluent, this effect remains minor and can be considered negligible.

Figure 16.

CFU/mL Enterobacteriaceae before and after treatment with CAP at effluent.

In contrast, a 3 min plasma treatment produced a slight, almost negligible increase in both MPN and MPF, but resulted in a threefold reduction in the number of culturable Enterobacteriaceae in August. Since the primary goal of post-treatment is to achieve both detoxification and disinfection, a 3 min CAP exposure can be considered the optimal treatment duration according to the findings of this study. It should be noted, however, that these recommendations will require further refinement during the engineering design and process scaling stages for the full-scale implementation of effluent treatment modules.

4. Discussion

Wastewater treatment in the tourism sector is of critical ecological, economic, and social importance. The key challenges requiring innovative solutions include improving treatment efficiency during periods of high seasonal load, achieving targeted removal of toxic micropollutants contributing to overall toxicity, and ensuring elimination of pathogenic microorganisms and residual toxicity during the tertiary treatment stage [8,39].

An innovative approach to improving treatment performance through the creation of pre-treatment modules involves the use of cold atmospheric plasma (CAP). CAP can also be applied in post-treatment to design modules aimed at removing residual micropollutant toxicity, while simultaneously enhancing disinfection efficiency by eliminating pathogenic and opportunistic bacteria.

Bioindication of these processes was performed by monitoring the metabolic potential (MP), expressed both as the number of active biological entities (individual bacterial cells, clusters, or biofilm fragments—MPN) and as fluorescence intensity (MPF). These indicators provide insight into the structural integrity and activity of microbial communities responsible for biodegradation in various treatment units, reflecting the total dehydrogenase activity [61]. This enzymatic activity represents the flow of hydrogen ions and electrons through transport chains, effectively characterizing the biodegradation of pollutants along major metabolic pathways such as the glycolytic chain and the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) [62,63].

CAP treatment modifies both influent and effluent through its short- and long-lived reactive plasma species, influencing biological structures and activity in the direction of activation or inhibition, depending on the treatment parameters [48,49], particularly the exposure duration [50,51,67].

Our results indicate that a 1 min CAP treatment of influent significantly increases the number and activity of biologically active units (MPN) and their activity (MPF), particularly in August, when wastewater loading and pollutant concentrations are at their highest. Several factors likely contribute to this trend in influent, as supported by the MPN—the reduction in size and increase in number of biological entities (groups of cells and smaller clusters), the detachment of microbial biofilms, including Enterobacteriaceae, from suspended organic and inorganic particles, and the release of more bioavailable organic substrates, which promote the growth and proliferation of viable bacteria, among them Enterobacteriaceae. An additional factor is the decrease in overall influent toxicity, which reduces the inhibitory pressure on all microorganisms, including these bacteria. The stronger these effects become under high organic loading, the greater the gradual increase in Enterobacteriaceae abundance observed in August, corresponding to the peak tourist season and prolonged treatment times.

This CAP stimulation like pre-treatment can accelerate biodegradation processes throughout the technological treatment chain, including both bioreactors and physical separation units such as grit chambers.

Altogether, these findings reinforce that plasma pre-treatment, when adapted to the specific seasonal loading of the influent at the Ravda WWTP, represents a suitable mechanism for enhancing treatment efficiency throughout the entire technological process chain. Naturally, this approach would require further engineering optimization and scaling before full-scale implementation.

Conversely, a 3 min CAP treatment of the effluent produced no substantial change in MPN or MPF, but led to a threefold reduction in the number of culturable Enterobacteriaceae in August in the most intensive tourism season at the highest organic loading (including highest xenobiotic pollution). As the primary objective of effluent post-treatment is disinfection combined with detoxification, a 3 min plasma exposure appears to be the most effective duration for achieving the goals of tertiary water treatment.

It may also indicate that the treatment parameters—including exposure duration, plasma source power, or the design of the bioreactor and plasma distribution system within the post-treatment modules—require further optimization. Adjusting these parameters could enhance the effectiveness of CAP treatment for the microbiological stabilization of effluent waters prior to discharge.

It is important to note that CAP was tested on real wastewater samples, yet practical implementation requires engineering optimization, reactor design, scaling, and validation under real operational conditions to fine-tune CAP parameters according to plant-specific technological configurations.

Overall, our findings are encouraging, as they provide a metabolically grounded rationale for the application of CAP in wastewater treatment and establish a clear link between metabolic indicators, treatment efficiency, and biological system dynamics across different treatment units.

5. Conclusions

Cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) treatment emerges as a reliable and promising approach for enhancing and accelerating wastewater treatment processes and for addressing critical unresolved challenges associated with conventional systems. This method can be employed to develop hybrid wastewater treatment technologies, expanding existing systems through the integration of pre-treatment and post-treatment plasma modules. Depending on the specific objectives of the treatment process and technological conditions, these modules should be adaptively controlled according to seasonal variations, organic loading, and the presence of toxic pollutants, among other factors.

Furthermore, bioindication of microbial and metabolic processes provides a valuable foundation for process control and optimization, both within the hybrid plasma modules and across the entire technological treatment chain. These promising findings lay the groundwork for further development, including engineering design, process scaling, and validation of CAP-based modules under real operational conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.T.; methodology, Y.T., E.B. and M.K.; software, M.B., I.Y. and N.D.; validation, Y.T. and E.B.; formal analysis, M.B., I.Y., N.D., T.B., P.M. and Y.T.; investigation, M.B., I.Y., N.D., T.B., P.M. and Y.T.; resources, Y.T., M.B. and I.Y.; data curation, I.Y.,Y.T. and E.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.T., I.Y. and M.B.; writing—review and editing, Y.T., I.Y., M.B., T.B., P.M. and E.B.; visualization, M.B.; supervision, Y.T. and I.Y.; project administration, I.Y.; funding acquisition, I.Y. and Y.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project № BG16RFPR002-1.014-0015, “Clean Technologies for Sustainable Environment—Water, Waste, Energy for Circular Economy”, financed by the European Regional Development Fund through the Bulgarian Program “Research, Innovation and Digitalisation for Smart Transformation” and the project № 80-10-180/04.06.2025, “Microbial and plasma detoxification combined with the elimination of bacteria from the Enterobacteriaceae family in the Ravda WWTP” funded by the research fund from Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski”.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to “Water Supply and Sewerage” EAD Burgas City, WWTP “Ravda”, and Diana Chorbadzhiyska for their assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WWTP | Wastewater treatment plant |

| CAP | Cold atmospheric plasma |

| PAW | Plasma-activated water |

| MPN | Metabolic potential by number of objects |

| MPF | Metabolic potential by fluorescence activity |

| PAU | Percentage of physiologically active units |

References

- Raschke, N. Environmental Impact Assessment as a Step to Sustainable Tourism Development. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2024, 84, 303–313. [Google Scholar]

- Otterpohl, R.; Wendland, C.; Al-Baz, I. Efficient Management of Wastewater: Its Treatment and Reuse in Water-Scarce Countries; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gaulke, L.S.; Weiyang, X.; Scanlon, A.; Henck, A.; Hinckley, T. Evaluation Criteria for Implementation of a Sustainable Sanitation and Wastewater Treatment System at Jiuzhaigou National Park, Sichuan Province, China. Environ. Manag. 2010, 45, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, Y.; Abidin, U.S.Z.; Yusof, Y.; Abidin, U.S.Z. Towards Sustainable Environmental Management through Green Tourism: Case Study on Borneo Rainforest Lodge. Asian J. Tour. Res. 2017, 2, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarda Mallorquí, A.; Sansbelló, R.M.; Pavón, D.; Ribas Palom, A. Tourist Development and Wastewater Treatment in the Spanish Mediterranean Coast: The Costa Brava Case Study. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan 2016, 11, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oarga-Mulec, A.; Jenssen, P.D.; Krivograd Klemenčič, A.; Uršič, M.; Griessler Bulc, T. Zero-Discharge Solution for Blackwater Treatment at Remote Tourist Facilities. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 798–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanova, M.; Yotinov, I.; Topalova, Y.; Lyubomirova, V. Wastewater Treatment Technology for Sustainable Tourism: Sunny Beach, Ravda WWTP Case Study. Water 2024, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanova, M.; Yotinov, I.; Topalova, Y. Comparison of the Work of Wastewater Treatment Plant “Ravda” in Summer and Winter Influenced by the Seasonal Mass Tourism Industry and COVID-19. Processes 2024, 12, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boragno, V.; Bruzzi, L.; Tarantini, M.; Verità, S. The Role of EMAS for Sustainable Coastal Tourism. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on the Management of Costal Recreational Resources-Beaches, Yacht Marinas and Coastal Ecotourism, Gozo, Malta, 7 November 2004; pp. 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Estévez, S.; Feijoo, G.; Moreira, M.T. Environmental Synergies in Decentralized Wastewater Treatment at a Hotel Resort. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 317, 115392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duygun, F.; Eylül, D. Analyzing the Wastewater Treatment Facility Location/Network Design Problem via System Dynamics: Antalya, Turkey Case. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 320, 115814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, G.; Francisco, J. An Analysis of the Cost of Water Supply Linked to the Tourism Industry. An Application to the Case of the Island of Ibiza in Spain. Water 2006, 12, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Shapiro, E.F.; Barajas-Rodriguez, F.J.; Gaisin, A.; Ateia, M.; Currie, J.; Helbling, D.E.; Gwinn, R.; Packman, A.I.; Dichtel, W.R. Trace Organic Contaminant Removal from Municipal Wastewater by Styrenic β-Cyclodextrin Polymers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 19624–19636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.L.; Maile-Moskowitz, A.; Lopatkin, A.J.; Xia, K.; Logan, L.K.; Davis, B.C.; Zhang, L.; Vikesland, P.J.; Pruden, A. Author Correction: Selection and Horizontal Gene Transfer Underlie Microdiversity-Level Heterogeneity in Resistance Gene Fate during Wastewater Treatment. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Li, T.; Hu, T.; Zheng, K.; Shen, M.; Long, H. Removal of Micro/nanoplastics in Constructed Wetland: Efficiency, Limitations and Perspectives. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 475, 146033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.H.; Aziz, H.A.; Palaniandy, P.; Naushad, M.; Cevik, E.; Zahmatkesh, S. Pharmaceutical Residues in the Ecosystem: Antibiotic Resistance, Health Impacts and Removal Techniques. Chemosphere 2023, 339, 139647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, A.; Bibi, S.; Abu-Dieyeh, M.; Al-Ghouti, M.A. Towards Sustainable Physiochemical and Biological Techniques for the Remediation of Phenol from Wastewater: A Review on Current Applications and Removal Mechanisms. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 417, 137810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Fu, D.; Wu, X.; Liu, C.; Yuan, X.; Wang, S.; Duan, C. Opposite Response of Constructed Wetland Performance in Nitrogen and Phosphorus Removal to Short and Long Terms of Operation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 120002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Z. Enhancing Pollutants Removal in Hospital Wastewater: Comparative Analysis of PAC Coagulation vs. Bio-Contact Oxidation, Highlighting the Impact of Outdated Treatment Plants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 471, 134340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priya, Y.; Rahul, P. Biogas Production Using Waste Water: Methodologies and Applications. In Advances in Chemical Pollution; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Priya, E.; Kumar, S.; Verma, C.; Sarkar, S.; Maji, P.K. A Comprehensive Review on Technological Advances of Adsorption for Removing Nitrate and Phosphate from Waste Water. J. Water Proc. Eng. 2022, 49, 103159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU) 2024/3019; 11 December 2023 on Urban Wastewater Treatment (Recast of Directive 91/271/EEC). European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/3019/oj/eng (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Gonçalves, J.; Pequeno, J.; Diaz, I.; Kržišnik, D.; Žigon, J.; Koritnik, T. Killing Two Crises with One Spark: Cold Plasma for Antimicrobial Resistance Mitigation and Wastewater Reuse. Water 2025, 17, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Y.; Hong, C.; Liu, D.; Yang, F.; Xiao, G.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, S. Dynamics of Bacterial Communities and Identification of Microbial Indicators in a Cylindrospermopsis-Bloom Reservoir in Western Guangdong Province, China. Processes 2025, 13, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, P.; Duan, N.; Ji, H.; Zhao, X. A Mini-Review on the Use of Chelating or Reducing Agents to Improve Fe(II)-Fe(III) Cycles in persulfate/Fe(II) Systems. Processes 2024, 12, 2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struhs, E.; Bare, W.F.R.; Mirkouei, A.; Overturf, K. Magnesium-Modified Biochar for Removing Phosphorus from Aquaculture Facilities: A Case Study in Idaho, USA. Processes 2025, 13, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bare, W.F.R.; Struhs, E.; Mirkouei, A.; Overturf, K.; Chacón-Patiño, M.L.; McKenna, A.M.; Chen, H.; Raja, K.S. Controlling Eutrophication of Aquaculture Production Water Using Biochar: Correlation of Molecular Composition with Adsorption Characteristics as Revealed by FT-ICR Mass Spectrometry. Processes 2023, 11, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Mei, Y.; Fan, F.; Zhang, S. Advancing the Frontiers of Wastewater Treatment—Synthesis and Future Perspectives in State-of-the-Art Techniques. Processes 2025, 13, 3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Francis, K.; Zhang, X. Review on Formation of Cold Plasma Activated Water (PAW) and the Applications in Food and Agriculture. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyedibe, V.O.; Waseem, H.; Aqeel, H.; Liss, S.N.; Gilbride, K.A.; Sühring, R.; Hamza, R. Influence of Polyester and Denim Microfibers on the Treatment and Formation of Aerobic Granules in Sequencing Batch Reactors. Processes 2025, 13, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, X.; Huang, C.; Bao, Z.; Zhao, X.; Tan, Z.; Xie, E. Effects of Irrigation with Slightly Algae-Contaminated Water on Soil Moisture, Nutrient Redistribution, and Microbial Community. Processes 2024, 12, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Wang, B.; Hou, Z.; Peng, J.; Li, D.; Chu, Z. Response of Nitrogen Removal Performance and Microbial Distribution to Seasonal Shock Nutrients Load in a Lakeshore Multicell Constructed Wetland. Processes 2023, 11, 2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Cao, J.; Liao, W.; Zhu, F.; Hou, Z.; Chu, Z. Effects of Vegetation Cover Varying along the Hydrological Gradient on Microbial Community and N-Cycling Gene Abundance in a Plateau Lake Littoral Zone. Processes 2024, 12, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csutak, O.E.; Nicula, N.-O.; Lungulescu, E.-M.; Marinescu, V.E.; Gifu, I.C.; Corbu, V.M. Candida Parapsilosis CMGB-YT Biosurfactant for Treatment of Heavy Metal- and Microbial-Contaminated Wastewater. Processes 2024, 12, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H.; Khirul, M.A.; Kang, D.; Jee, H.; Park, C.; Jung, Y.; Song, S.; Yang, E. Cutting-Edge Solutions for Soil and Sediment Remediation in Shipyard Environments. Processes 2025, 13, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Wang, S.; Dong, Y.; Ni, Z.; Hong, Y. Spatiotemporal Analysis and Risk Prediction of Water Quality Using Copula Bayesian Networks: A Case in Qilu Lake, China. Processes 2024, 12, 2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Yang, Z.; Ouyang, W. Surface Runoff and Diffuse Nitrogen Loss Dynamics in a Mixed Land Use Watershed with a Subtropical Monsoon Climate. Processes 2023, 11, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lao, K.; Chen, C.; Zhu, H.; Yang, Y.; Chen, H.; Pang, H. Field Study on Washing of 4-Methoxy-2-Nitroaniline from Contaminated Site by Dye Intermediates. Processes 2024, 12, 2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhang, D.; Sui, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, W.; Huo, Z.; Wu, Y. Improved Dujiangyan Irrigation System Optimization (IDISO): A Novel Metaheuristic Algorithm for Hydrochar Characteristics. Processes 2024, 12, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, X.; Lang, H.; Zhang, P.; Ni, J.; Wu, W. Effects of Reclaimed Water Supplementation on the Occurrence and Distribution Characteristics of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in a Recipient River. Processes 2024, 12, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirilova, M.; Todorova, Y.; Marinova, P.; Bogdanov, T.; Yotinov, I.; Schneider, I.; Dinova, N.; Topalova, Y.; Benova, E. Plasma-Assisted Reduction of Toxicity of Landfill Leachate, Spiked with PFOA. J. Water Proc. Eng. 2025, 76, 108190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooshki, S.; Pareek, P.; Mentheour, R.; Janda, M.; Machala, Z. Efficient Treatment of Bio-Contaminated Wastewater Using Plasma Technology for Its Reuse in Sustainable Agriculture. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 32, 103287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanayake, U.M.; Barclay, M.; Seo, D.H.; Park, M.J.; MacLeod, J.; O’Mullane, A.P.; Motta, N.; Shon, H.K.; Ostrikov, K. Utilization of plasma in water desalination and purification. Desalination 2021, 500, 114903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aka, R.J.N.; Wu, S.; Mohotti, D.; Bashir, M.A.; Nasir, A. Evaluation of a Liquid-Phase Plasma Discharge Process for Ammonia Oxidation in Wastewater: Process Optimization and Kinetic Modeling. Water Res. 2022, 224, 119107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magureanu, M.; Mandache, N.B.; Parvulescu, V.I. Degradation of pharmaceutical compounds in water by non-thermal plasma treatment. Water Res. 2015, 81, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardenier, N.; Gorbanev, Y.; Van Moer, I.; Nikiforov, A.; Van Hulle, S.W.; Surmont, P.; Lynen, F.; Leys, C.; Bogaerts, A.; Vanraes, P. Removal of alachlor in water by non-thermal plasma: Reactive species and pathways in batch and continuous process. Water Res. 2019, 161, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patinglag, L.; Melling, L.M.; Whitehead, K.A.; Sawtell, D.; Iles, A.; Shaw, K.J. Non-Thermal Plasma-Based Inactivation of Bacteria in Water Using a Microfluidic Reactor. Water Res. 2021, 201, 117321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumdas, R.; Kothakota, A.; Annapure, U.; Siliveru, K.; Blundell, R.; Gatt, R.; Valdramidis, V.P. Plasma Activated Water (PAW): Chemistry, Physico-Chemical Properties, Applications in Food and Agriculture. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 77, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, J.C.; Suchowerska, N.; McKenzie, D.R. Cancer Treatment with Gas Plasma and with Gas Plasma-Activated Liquid: Positives, Potentials and Problems of Clinical Translation. Biophys. Rev. 2020, 12, 989–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milhan, N.V.M.; Chiappim, W.; da Sampaio, A.G.; da Vegian, M.R.C.; Pessoa, R.S.; Koga-Ito, C.Y. Applications of Plasma-Activated Water in Dentistry: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Wang, S.; Li, B.; Qi, M.; Feng, R.; Li, Q.; Zhang, H.; Chen, H.; Kong, M.G. Effects of Plasma-Activated Water on Skin Wound Healing in Mice. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herianto, S.; Arcega, R.D.; Hou, C.-Y.; Chao, H.-R.; Lee, C.-C.; Lin, C.-M.; Mahmudiono, T.; Chen, H.-L. Chemical Decontamination of Foods Using Non-Thermal Plasma-Activated Water. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 874, 162235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Fang, C.; Shao, C.; Li, L.; Huang, Q. Study of the Synergistic Effect of Singlet Oxygen with Other Plasma-Generated ROS in Fungi Inactivation during Water Disinfection. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, M.; Sun, C.; Zhang, X. Microbubble-Enhanced Water Activation by Cold Plasma. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirilova, M.; Topalova, Y.; Velkova, L.; Dolashki, A.; Kaynarov, D.; Daskalova, E.; Zheleva, N. Antibacterial Action of Protein Fraction Isolated from Rapana Venosa Hemolymph against Escherichia Coli NBIMCC 8785. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSI—National Statistical Institute. Available online: https://www.nsi.bg/en (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Ministry of Tourism of the Republic of Bulgaria. Available online: https://www.tourism.government.bg/en (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Assessment of Contamination with Opportunistic Pathogenic Bacteria from Family Enterobacteriaceae in Sediments of Iskar River. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ivaylo-Yotinov/publication/319623737_Assessment_of_Contamination_with_Opportunistic_Pathogenic_Bacteria_from_Family_Enterobacteriaceae_in_Sediments_of_Iskar_River/links/59b660a50f7e9b374355de1b/Assessment-of-Contamination-with-Opportunistic-Pathogenic-Bacteria-from-Family-Enterobacteriaceae-in-Sediments-of-Iskar-River.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- BDS 17336:1993; Determining the Most Probable Number (MPN) of Coliforms, Fecal coliforms and Escherichia coli. IWA: London, UK, 1993.

- Yordanova, V.; Todorova, Y.; Belouhova, M.; Kenderov, L.; Lyubomirova, V.; Topalova, Y. Environmental Impact Assessment of Discharge of Treated Wastewater Effluent in Upper Iskar Sub-Catchment. BioRisk 2022, 17, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsot, A.S.; Dzantor, E.K. Effect of alachlor concentration and an organic amendment on soil dehydrogenase activity and pesticide degradation rate. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1995, 14, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małachowska-Jutsz, A.; Matyja, K. Discussion on methods of soil dehydrogenase determination. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 7777–7790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X. Bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon-contaminated soil by petroleum-degrading bacteria immobilized on biochar. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 35304–35311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, E.W.; Bridgewater, L. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]