Abstract

Nanoplastics have emerged as widespread environmental contaminants with toxicological properties that differ from those of microplastics. While existing reviews often examine their effects on specific organisms, they rarely provide direct comparisons with microplastics. This review aims to comprehensively assess the toxic effects of nanoplastics on animals, with a comparative perspective highlighting their distinctions from microplastics. In mammals, nanoplastics cross the blood–brain barrier and induce oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and synaptic disruption, with consequences ranging from cognitive impairment to Parkinson’s disease-like neurodegeneration. They also impair liver, kidney, intestinal, pancreatic, and reproductive function, with evidence of transgenerational toxicity. In aquatic organisms such as fish, crustaceans, bivalves, and aquatic invertebrates, nanoplastics compromise growth, immunity, reproduction, and metabolism, while in terrestrial invertebrates they cause gut toxicity, mitochondrial damage, immune suppression, and heritable defects. Across taxa, the dominant mechanisms involve oxidative stress, apoptosis, inflammation, and interference with metabolic and signaling pathways. Comparisons with microplastics reveal that while both particle types are harmful, nanoplastics generally exert stronger and more systemic effects due to higher bioavailability, cellular uptake, and molecular reactivity. Microplastics primarily impose mechanical stress, whereas nanoplastics disrupt cellular homeostasis at lower exposure levels, often acting at the subcellular level. Evidence also indicates size-, surface chemistry-, and concentration-dependent effects, with smaller and functionalized nanoplastics exhibiting heightened toxicity. Despite growing knowledge, significant gaps remain in cross-size comparative studies, long-term and multigenerational assessments, trophic transfer analyses, and investigations involving environmentally derived nanoplastics. Addressing these gaps is critical for advancing ecological risk assessment and developing mitigation strategies against plastic pollution.

1. Introduction

Plastics are integral to many sectors due to their versatility and performance in modern applications. They are lightweight, are resistant to chemicals, possess mechanical strength, offer durability, are cost-effective, and have insulating properties, which makes them popular worldwide [1]. Global plastic production and usage hit about 415 million tonnes in 2023, marking a substantial increase from roughly 234 million tonnes in 2000, with estimates between 435 and 460 million tonnes in 2024 [2]. Forecasts from the OECD suggest that, with no major policy changes, plastics production and waste could surge by nearly 70 % by 2040, reaching around 736 million tonnes annually, driven by rising demand in both developed and emerging economies [3].

When it comes to disposal and recycling, only about 9 % of all plastics ever produced have been recycled globally, with 14 % of plastic packaging being collected for recycling. The remaining plastics, estimated at between 79 and 91 %, are either landfilled, or incinerated, or leak into natural environments, with over 300 million tonnes of plastic waste generated annually, much of which ends up mismanaged or polluting ecosystems [4]. Mismanaged plastics that are not properly collected or treated often end up in the natural environment, where they accumulate and persist for extended periods [5]. A significant portion of this waste is carried by wind and water into rivers, lakes, and oceans, contributing to widespread marine pollution [6]. Over time, larger plastic items break down into microplastics and nanoplastics through physical, chemical, and biological processes, further infiltrating ecosystems [7]. These small plastic particles derived from the breakdown of larger ones are called secondary micro- or nanoplastics. Primary microplastics and nanoplastics, on the other hand, are intentionally manufactured small plastic particles designed for specific industrial, commercial, or consumer applications. These include microbeads used in personal care products (e.g., exfoliants in facial cleansers and toothpaste), abrasives in industrial cleaning agents, and pre-production plastic pellets known as nurdles used in plastic manufacturing [8]. Nanoplastics, though less well-characterized, may be produced deliberately for use in targeted drug delivery systems, nanocomposites, or advanced coatings. These particles enter the environment directly through pathways such as wastewater discharge, runoff from industrial sites, and accidental spills during production or transport [9]. Due to their minute size, they often bypass filtration systems in wastewater treatment plants and disperse easily into aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, raising concerns over their bioavailability, persistence, and potential toxicity to organisms [10].

Every year, roughly 2.7–3 million tonnes of microplastics are released into the global environment. This includes about 3 million tonnes of primary microplastics (such as pellets, microbeads, and turf infills), with nearly 1.5 million tonnes entering the oceans alone [11]. In Europe, about 145,000 tonnes of intentionally added microplastics and 176,000 tonnes of inadvertently formed microplastics (from sources like tires, paints, textiles, and pellet loss) are released into surface waters each year [12]. Although nanoplastics remain more difficult to measure, they are now recognized as widespread and growing contaminants within ecosystems and food webs [13]. Currently, there are no standardized global release-volume estimates for nanoplastics.

Microplastics and nanoplastics are small plastic particles that differ primarily in size and origin. Microplastics are typically defined as plastic fragments, fibers, or beads measuring less than 5 mm in diameter, with some definitions specifying a lower bound of 1 micrometer (µm) [14]. Nanoplastics, on the other hand, are generally defined as plastic particles smaller than 1000 nanometers (nm), with some definitions adopting a narrower range of 1–100 nm. These definitions are still evolving due to challenges in detection and measurement at the nanoscale [15,16,17]. This review will adopt a size range of 1–1000 nm for nanoplastics to encompass a broader spectrum of findings on the toxic effects of nanoplastics.

Microplastics and nanoplastics pose significant toxicological threats to living organisms due to their small size, large surface area, and capacity to adsorb and carry harmful environmental pollutants such as heavy metals, persistent organic pollutants, and pathogens [18,19,20]. Once ingested or inhaled, these particles can translocate across biological barriers, accumulate in tissues, and induce a range of adverse effects including oxidative stress, inflammation, cytotoxicity, immune disruption, endocrine interference, and genotoxicity [21,22]. Nanoplastics, in particular, can penetrate cellular membranes more readily than microplastics, increasing their potential for cellular damage and interference with gene expression and metabolic pathways. These effects have been observed across multiple taxa, including aquatic organisms, mammals, and even human cell lines, raising growing concern about the potential long-term health and ecological consequences of plastic pollution [23,24]. For instance, a study found that microplastics elevated the activity of antioxidant enzymes, such as catalase, glutathione reductase, and glutathione-S-transferase, in the liver of gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata), indicating an activated oxidative stress response [25]. Additionally, inhalation of polystyrene micro- and nanoplastics was demonstrated to trigger lung inflammation in rats [26]. Lee et al. [27] found that smaller polystyrene nanoplastics easily entered zebrafish embryos, accumulating mainly in lipid-rich areas like the yolk. They caused minimal impacts on survival, hatching, development, and cell death.

Although it is commonly claimed that nanoplastics could be more toxic than microplastics because of their smaller size, larger surface area, and easier cellular entry, there are few reviews that offer a comparative perspective on nanoplastic and microplastic toxicity. Liao et al. [28] reviewed the toxic mechanisms of micro- and nanoplastics on various animal organs but did not distinguish between the toxic effects of nanoplastics and microplastics or compare their differences. Urli et al. [29] focused on how microplastics and nanoplastics behave in farms and their effects on livestock, without differentiating between the two particle types. Jiang et al. [30] studied the bioaccumulation of both microplastics and nanoplastics and their impacts on human health; however, their review also did not differentiate between the two types of particles and was limited to human health effects.

This review, therefore, primarily aims to present the toxic effects of nanoplastics on animals. Secondarily, it seeks to provide a comparative overview of these effects against those of microplastics. By doing so, it hopes to clarify their distinct biological impacts, address existing knowledge gaps, and support more accurate risk assessments and regulatory strategies.

2. Review Methodology

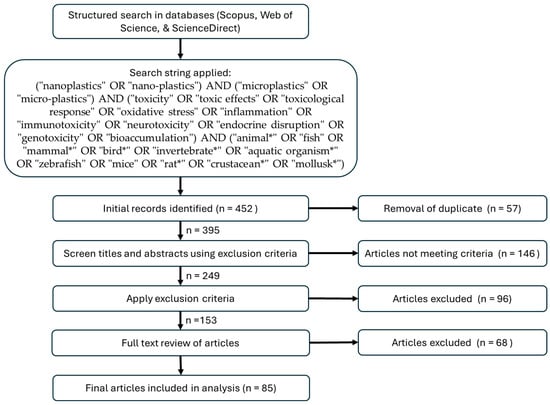

This review adopts a narrative approach to synthesize and evaluate the current scientific literature on the toxic effects of nanoplastics and microplastics in animals. A comprehensive literature search was conducted using major scientific databases, including Web of Science, Scopus, and ScienceDirect, covering publications from 2015 to 2025. The search strategy included combinations of the following keywords: “nanoplastics,” “microplastics,” “toxicity,” “animal exposure,” “bioaccumulation,” “oxidative stress,” “inflammation,” “endocrine disruption,” “genotoxicity,” and “comparative toxicity.” Boolean operators (AND, OR) were used to refine the searches, and filters were applied to limit results to peer-reviewed journal articles written in English.

The representative search string applied in all databases was: (“nanoplastics” OR “nano-plastics”) AND (“microplastics” OR “micro-plastics”) AND (“toxicity” OR “toxic effects” OR “toxicological response” OR “oxidative stress” OR “inflammation” OR “immunotoxicity” OR “neurotoxicity” OR “endocrine disruption” OR “genotoxicity” OR “bioaccumulation”) AND (“animal *” OR “fish” OR “mammal *” OR “bird *” OR “invertebrate *” OR “aquatic organism *” OR “zebrafish” OR “mice” OR “rat *” OR “crustacean *” OR “mollusk *”).

Inclusion criteria focused on: (1) Experimental studies involving in vivo or in vitro animal models exposed to nanoplastics, with or without direct comparison to microplastics; and (2) Studies reporting on specific toxicological endpoints, including but not limited to: oxidative stress, inflammation, immunotoxicity, genotoxicity, neurotoxicity, and reproductive or developmental effects. Studies reporting multiple endpoints were also included. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Studies that focused solely on human health, plants, or microbial communities without animal models; (2) Papers lacking empirical data (e.g., editorials, news articles, or speculative commentaries); (3) Studies conducted on cell line models only; and (4) Reviews or meta-analyses that did not include comparative discussions between microplastics and nanoplastics. A flowchart of the review methodology is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of literature retrieval, screening, and selection. (* indicates a wildcard symbol used to represent any group of characters that can follow the root of the keyword, e.g., animals, animalia, etc.).

The collected evidence was then categorized by biological system affected (e.g., digestive, respiratory, nervous, reproductive) and by type of organism (e.g., aquatic invertebrates, fish, mammals, birds). This structure facilitated a side-by-side comparison of nanoplastic versus microplastic toxicity and highlighted size-related trends in their biological impacts. Comparative data were extracted directly from studies conducted on both microplastics and nanoplastics. For these data, only those with statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) were typically presented in this review. In instances where direct comparison was lacking, the comparison was inferred.

The primary objective of the review is to examine the toxicity of nanoplastics of different polymer types and sizes on different animals, with a secondary objective of providing brief comparative insights into the effects of nanoplastics and microplastics on animals. Therefore, the conceptual framework here is that plastic particle properties, particularly particle size and polymer type (1–1000 nm for nanoplastics and >1 µm to <5 mm for microplastics as defined in the introduction, with polymer types such as polystyrene, polyethylene and PET) → govern → tissue distribution in animals → initiate → molecular and cellular mechanisms (reactive oxygen species generation, inflammation, genotoxicity, endocrine disruption) → manifest as → physiological and behavioral effect → contribute to → organismal outcomes. The comparative dimension is the size-dependent toxicity gradient, in which toxicity is thought to increase with decreasing size due to greater surface area, mobility, and bioavailability.

The review is constrained to reporting the toxicity results and, therefore, has the limitation of not examining methodological robustness and biases in adequate detail. Additionally, the toxic effects on mammals primarily depend on mouse models, as they are most used in studies examining the toxic impacts of nanoplastics on mammals. There are significantly more studies conducted on mouse models than on other organisms, resulting in more information about mice presented here than about other animals. Since more studies on mice focus on specific organs and systems, this allows information about mice to be categorized based on these bioindicators. Furthermore, there are significantly more studies conducted on polystyrene than on other polymer types, which limits comparison across plastic polymers.

3. Toxic Effects of Nanoplastics

Nanoplastics have emerged as a significant environmental concern due to their unique physicochemical properties and potential for heightened toxicity compared to larger plastic particles. Their extremely small size enables them to traverse biological membranes, accumulate within cells and tissues, and interact directly with subcellular structures, posing distinct toxicological risks to a wide range of animal species [23,30,31]. As nanoplastics become increasingly prevalent in ecosystems, elucidating their toxic effects is essential for assessing ecological risks and informing environmental health policies.

3.1. Mouse Models

3.1.1. Effects on the Brain and Behaviors

Liu et al. [32] found that nanoplastics (carboxyl- or amino-functionalized polystyrene) can reach the brain through nasal inhalation, leading to neurotoxic effects and behavioral changes in animals. Smaller nanoparticles were taken up by cells more efficiently than larger ones. Specifically, 80 nm polystyrene nanoplastics were capable of penetrating the brain tissue of mice following aerosol exposure. Mice exposed to these nanoparticles showed reduced locomotor activity compared to those exposed to water aerosols. Furthermore, the nanoplastics caused significant neurotoxicity, as evidenced by the suppression of acetylcholinesterase activity [32].

A 28-day oral toxicity study in C57BL/6J mice exposed to 0.25–250 mg/kg of 50 nm polystyrene nanoplastics revealed Parkinson’s disease-like neurodegeneration [33]. Single-nucleus RNA sequencing of over 62,000 brain cells showed cell-specific disruptions, mainly involving impaired energy metabolism and mitochondrial dysfunction across brain cell types. Excitatory neurons showed the greatest vulnerability, while astrocytes and microglia exhibited inflammatory changes. Proteostasis and synaptic regulation were also disturbed in astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and endothelial cells, collectively contributing to the observed neurodegenerative effects [33].

Furthermore, Rafiee et al. [34] evaluated the potential neurobehavioral effects of polystyrene nanoparticles in adult male Wistar rats orally exposed to 1–10 mg/kg/day for five weeks. The polystyrene nanoplastics averaged 38.92 nm in size. Although no statistically significant behavioral or body weight changes were observed, exposed rats showed increased entries into open arms in the elevated plus maze. These subtle effects suggest that even pristine nanoplastics may influence behavior in other organisms, including marine life and humans. Shan et al. [35] examined whether 50 nm polystyrene nanoplastics can cross the blood–brain barrier and cause neurotoxicity. In mice, polystyrene nanoplastics (0.5–50 mg/kg for 7 days) increased blood–brain barrier permeability and accumulated in the brain in a dose-dependent manner. The particles were detected in microglia, triggering their activation and causing neuronal damage. In vitro, polystyrene nanoplastics entered human brain endothelial cells (hCMEC/D3), induced reactive oxygen species production, NF-κB activation, TNF-α release, necroptosis, and disrupted tight junction integrity. Polystyrene nanoplastics also activated BV2 microglia, and their conditioned medium harmed HT-22 neurons. Overall, the study indicates that polystyrene nanoplastics can cross the blood–brain barrier and induce neurotoxicity, likely through microglial activation [35].

Chu et al. [36] explored whether 25 nm polystyrene nanoplastics could impair learning in mice. Forty mice were orally exposed to 0, 10, 25, or 50 mg/kg polystyrene nanoplastics for six months. Behavioral tests, histopathology, reactive oxygen species levels, and DNA damage were assessed. RNA sequencing of the prefrontal cortex revealed significant expression changes in 987 mRNAs, 29 miRNAs, and 67 circRNAs between control and high-dose groups. Exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics led to dose-dependent cognitive decline, increased reactive oxygen species and DNA damage, and signs of synaptic dysfunction [36].

3.1.2. Effects on the Digestive System and Kidneys

Monodisperse (80 nm) fluorescent polystyrene nanoplastics were found to accumulate in the liver, kidneys, spleen, and pancreas of mice after oral exposure (5 mg/kg and 15 mg/kg body weight) [37]. This led to organ damage, especially liver dysfunction and disrupted lipid metabolism. RNA-Seq analysis showed that polystyrene nanoplastics affected genes linked to reactive oxygen species production and the PI3K/Akt pathway. Chronic exposure raised reactive oxygen species and blood glucose levels without altering insulin secretion. Increased IRS-1 phosphorylation reduced Akt activation, indicating insulin resistance [37]. Overall, polystyrene nanoplastics triggered oxidative stress and lipid buildup, and impaired glucose regulation in the liver.

In another study, four-week-old mice were orally exposed to polystyrene nanoplastics at doses of 0, 0.2, 1, or 10 mg/kg for 30 days [38]. The findings showed that exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics influenced the expression of genes related to mucus production and altered the composition of gut microbiota, despite causing no behavioral changes. Additionally, there were no significant signs of inflammation or oxidative stress in the liver, lungs, intestines, cortex, or blood serum. Histological analysis also revealed no tissue damage in the liver, lungs, or cortex.

Choi et al. [39] examined the biodistribution, toxicity, and inflammation in ICR mice given 5, 25, or 50 mg/kg of polystyrene nanoplastics or purified polystyrene nanoplastics (500 nm) for two weeks. Nanoplastics, when orally fed through water, accumulated primarily in the intestine, followed by the kidneys and liver. Despite no significant changes in serum biochemistry or tissue structure, nanoplastic exposure led to marked increases in inflammatory markers (iNOS, COX-2, and cytokine mRNA) and oxidative stress indicators (reactive oxygen species, superoxide dismutase activity, and Nrf2 expression) in all three organs. Similar effects were observed in the purified nanoplastic group [39].

A study involving intragastric inoculation of C57BL/6 male mice with 50 μg/mL polystyrene nanoplastics (60 nm) and incubation of human gastric epithelial (GES-1) cells with polystyrene microplastics (50 μg/mL, 500 μL) for up to 48 h reported that fluorescent polystyrene nanoplastics were detected in the stomach, intestines, and liver of mice, as well as in GES-1 cells [40]. Their uptake by GES-1 cells involved multiple endocytic pathways, with reduced internalization observed when caveolae-, clathrin-mediated, macropinocytosis, RhoA, or F-actin pathways were inhibited. In contrast, Rac1 inhibition had little impact. Polystyrene nanoplastics were found within cellular compartments like vesicles, autophagosomes, and lysosomes. Exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics upregulated RhoA, F-actin, RAB7, and LAMP1, but downregulated Rab5. The particles reduced cell proliferation, triggered apoptosis, and promoted autophagosome formation, with increased LC3II expression over time [40]. These findings suggest that polystyrene nanoplastics enter cells via RhoA/F-actin-regulated endocytosis and induce cytotoxicity through autophagic and lysosomal disruption.

Xu et al. [41] exposed mice to ~100 nm polystyrene nanoplastics (amino-functionalized, carboxyl-functionalized, and unmodified) at a human-equivalent dose (1 mg/day) for 28 days. All types caused Crohn’s-like ileitis, marked by structural damage, inflammation, and necroptosis of intestinal epithelial cells, with carboxyl- and amino-functionalized polystyrene nanoplastics showing stronger effects. The nanoplastics triggered necroptosis via the RIPK3/MLKL pathway, linked to mitochondrial accumulation and stress. Although mitophagy was activated through the PINK1/Parkin pathway, it was disrupted due to lysosomal de-acidification. Restoring mitophagy with rapamycin reduced necroptosis of intestinal epithelial cells [41].

In another study, mice were given drinking water containing polystyrene nanoplastics (50 nm) at 0.1, 1, and 10 mg/L for 32 weeks [42]. Polystyrene nanoplastic exposure led to their accumulation in intestinal tissues, upregulating endocytosis proteins (clathrin and caveolin) and disrupting gut structure, particularly at higher doses, with villus erosion, reduced crypts, and heavy inflammatory cell infiltration. Tight junction proteins (occludin, claudin-1, ZO-1) were significantly reduced, especially at 1 and 10 mg/L. Polystyrene nanoplastics also triggered oxidative stress (increased reactive oxygen species and malondialdehyde, decreased superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase), altered immune cell populations (increased B cells in mesenteric lymph nodes, reduced CD8+ T cells in intestinal epithelial cells, and lamina propria lymphocytes), and elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β) [42]. Overall, chronic polystyrene nanoplastic exposure compromised the intestinal barrier and immune function, posing potential health risks.

A study examined whether oral exposure to 10 μg/L, 50 μg/L, and 100 μg/L of polystyrene nanoplastics (500 nm) for two weeks induced constipation in ICR mice [43]. Treated mice showed reduced water intake, stool weight, and moisture, altered stool shape, and decreased gastrointestinal motility and intestinal length. Significant structural changes in the mid-colon were observed. Polystyrene microplastics also lowered levels of gastrointestinal hormones, muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, and related signaling. Additionally, chloride ion levels and related channels (CFTR, CIC-2), as well as water transport proteins (AQP3, AQP8), were reduced via activation of the MAPK/NF-κB pathway [43]. The findings suggest polystyrene microplastics cause chronic constipation by disrupting gut motility, mucin secretion, and ion/water transport in the colon.

3.1.3. Systemic Toxicity

Male Wistar mice were orally exposed to polystyrene nanoplastics (25 and 50 nm mixed) at 1, 3, 6, and 10 mg/kg/day for 5 weeks [44]. Whole-body imaging confirmed polystyrene microplastic accumulation, and exposure triggered a dose-dependent rise in reactive oxygen species. While catalase and glutathione levels changed, superoxide dismutase remained unaffected, indicating redox imbalance. Significant increases were observed in glucose, cortisol, lipase, lactate, lactate dehydrogenase, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, triglycerides, and urea, while total protein, albumin, and globulin decreased [44]. These biochemical shifts, along with altered acetylcholinesterase activity, suggest potential neurobehavioral effects and disrupted energy metabolism, likely linked to stress, liver, and kidney dysfunction.

After 28 days of oral exposure to ~100 nm polystyrene nanoplastics (10 mg/mL, 100 µL), mice were observed to have accumulated the nanoplastics in multiple organs, including the spleen, lungs, kidneys, intestines, testis, and brain [45]. This was accompanied by tissue inflammation, apoptosis, and structural damage. Polystyrene nanoplastics also caused damage to the blood system and disrupted lipid metabolism. In vitro, polystyrene nanoplastics entered Caco-2 intestinal cells via macropinocytosis and clathrin-mediated endocytosis, damaging tight junctions. Amino-functionalized and carboxyl-functionalized polystyrene microplastics were more readily taken up by cells, likely explaining their higher toxicity [45].

A study exposed male Swiss albino mice to polyethylene terephthalate (PET) nanoplastics (~96 nm, 200 mg/kg, orally) for 30 days [46]. Blood and kidney samples were analyzed. PET nanoplastic exposure led to increased levels of blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and malondialdehyde, along with decreased glutathione. Kidney tissue showed notable damage, including shrinking of renal corpuscles, structural loss in proximal convoluted tubules and distal convoluted tubules, and signs of hyalinization, congestion, and degeneration in the medulla.

Following oral exposure to 0.01 mg/day and 0.1 mg/day of carboxylate-modified polystyrene particles (40 nm and 200 nm), fluorescent polystyrene nanoplastics were found to travel through the digestive tract, accumulate in various organs, and cause cellular and organ-level changes in mice [47]. In vitro tests using cochlear explants revealed polystyrene nanoplastic aggregation in inner ear hair cells. In males, polystyrene nanoplastics accumulated around the seminiferous tubules in the testes, leading to reduced testosterone levels. Increased secretion of IL-12p35 and IL-23 by splenocytes was observed, alongside spleen cell damage and DNA impairment. Males also exhibited anxiety-like behavior, while treated females showed elevated expression of pro-apoptotic and pro-inflammatory genes (Bax, Nlrp3) in the hippocampus [47].

3.1.4. Transgenerational Effects

Huang et al. [48] assessed the transgenerational toxicity of 100 nm polystyrene nanoplastics in mice exposed during pregnancy and lactation at doses of 0.1, 1, and 10 mg/L. Maternal exposure led to reduced birth and postnatal body weight in offspring. High doses caused liver damage in male offspring, marked by reduced liver weight, oxidative stress, and inflammation, elevated proinflammatory cytokines, and disrupted glucose metabolism. Additionally, polystyrene microplastic exposure before and after birth lowered testis weight, impaired testicular structure, reduced sperm count, and induced oxidative damage in the testes of newborn mice [48].

Jeong et al. [49] examined how polystyrene nanoplastics (50 nm and 500 nm at 0.5–1000 µg/day) affect brain development using both neural stem cell cultures and mice exposed during early life stages. Nanoplastic-containing jelly cubes were given to pregnant subjects daily starting on embryonic day 8, continuing until the two-week postpartum period. Maternal exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics during pregnancy and lactation disrupted neural stem cell function, altered brain cell composition, and affected brain structure in offspring. Similar molecular and functional impairments were seen in cultured neural stem cells. High levels of polystyrene nanoplastics also led to sex-specific neurophysiological and cognitive deficits in offspring [49].

3.1.5. Effects on the Reproductive System

Amereh et al. [50] examined the potential reproductive endocrine toxicity of polystyrene nanoplastics (~39 nm) in male rats under hypothetical exposure scenarios (1–10 mg/kg/day for five weeks). They assessed semen quality, hormone levels, sperm DNA integrity, and molecular markers of endocrine disruption. Exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics led to dose-dependent declines in testosterone, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone levels, along with observable tissue damage even at the lowest dose. DNA damage, abnormal sperm morphology, and reduced viability increased with higher exposures. Gene expression analysis revealed significant suppression of spermatogenesis-related markers, indicating disruption of both testicular function and the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis. Interestingly, follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone gene expression rose at the highest dose, and androgen-binding protein analysis suggested a nonlinear dose–response. Unexpectedly, gonadotropin-releasing hormone levels increased with exposure, though sensitivity diminished at higher doses [50].

Additionally, An et al. [51] explored how polystyrene nanoplastics affect ovarian function and the underlying mechanisms in rats. Female Wistar rats were exposed to varying doses (0 to 1.5 mg/d) of 0.5 μm polystyrene nanoplastics for 90 days. Ovarian tissue and blood were then analyzed. In vitro, granulosa cells were treated with different concentrations (0 to 25 µg/mL) of polystyrene nanoplastics, with or without the antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC). Results showed that polystyrene nanoplastics entered granulosa cells, reduced growing follicle numbers, and lowered anti-Müllerian hormone levels. Polystyrene nanoplastics also triggered oxidative stress, granulosa cell apoptosis, and ovarian fibrosis. These effects were linked to activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and increased expression of fibrosis-related proteins (TGF-β, fibronectin, α-SMA). NAC treatment reduced oxidative stress, granulosa cell apoptosis, and Wnt pathway activation [51]. Overall, polystyrene nanoplastics impaired ovarian reserve by promoting oxidative stress-induced cell death and fibrosis via the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

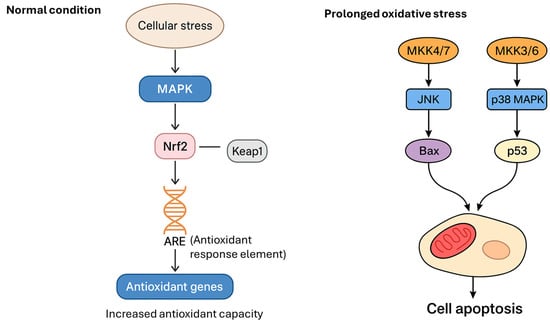

Li et al. [52] investigated how polystyrene nanoplastics affect male reproduction and the blood–testis barrier (BTB) in rats. Thirty-two male Wistar rats were given polystyrene nanoplastics (500 nm) daily at varying doses (0, 0.015, 0.15, and 1.5 mg/day) for 90 days. Results showed that polystyrene nanoplastics caused damage to seminiferous tubules, increased spermatogenic cell apoptosis, reduced sperm motility and concentration, and raised sperm abnormalities. Polystyrene nanoplastics also triggered oxidative stress, activated the p38 MAPK pathway, and suppressed Nrf2. Additionally, BTB-related protein expression declined [52]. These findings suggest that polystyrene nanoplastics impair male fertility by disrupting BTB integrity and inducing cell apoptosis via the MAPK-Nrf2 pathway (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Activation of MAPK–Nrf2 initially protects against apoptosis by enhancing antioxidant defenses. However, under excessive or chronic stress, MAPKs also drive pro-apoptotic signaling. MAPK kinase (MKK) 4/7 activates JNK, which in turn activates Bax, a pro-apoptotic protein that disrupts mitochondrial integrity. MKK3/6 activates p38 MAPK, which stimulates p53, a transcription factor that induces pro-apoptotic genes. Both Bax (mitochondria-mediated) and p53 pathways converge on the cell, leading to programmed cell death (apoptosis).

Male Swiss albino mice were exposed to polystyrene nanoplastics (0.2 mg/mL, 50 nm) for 60 days to assess subchronic toxicity [53]. Evaluations included sperm quality, antioxidant enzyme activity, testis structure, and histology using the Johnsen scoring system. While no lethal effects were observed, polystyrene nanoplastics reduced body and testis weights. Sperm quality declined, and testicular abnormalities, such as vascular congestion, Leydig cell hyperplasia, and structural damage, highlighted the reproductive toxicity risk of polystyrene nanoplastic exposure.

3.1.6. Comparative Studies

When examining how polystyrene nanoplastics (50 nm, 300 nm, and 600 nm) and microplastics (4 μm) change in the gastrointestinal tract and their effects on mouse kidneys, it was found that digestion caused these particles to aggregate and increased their Zeta potential [54]. Both types accumulated in the kidneys, with 600 nm nanoplastics showing higher toxicity. Exposure to all particles led to weight loss, higher mortality, altered biomarkers, kidney tissue damage, oxidative stress, and inflammation in mice. Catalase activity significantly declined in the 600 nm and 4 μm groups by 54.48% and 27.41%, respectively, compared to the control. In contrast, malondialdehyde levels increased in the 50 nm, 300 nm, and 600 nm groups [54].

Cheng et al. [55] examined how polystyrene microplastics and nanoplastics damage intestinal epithelial cells. In cell (human colonic epithelial cells exposed to 1 mg/mL plastic particles for 24 h) and mouse models (exposed to 0.1 mg/day of plastic particles by oral gavage for 7 weeks), 100 nm nanoplastics entered cells via endocytosis, causing oxidative stress and ferroptosis, while 10 μm microplastics mainly caused mechanical injury and altered cell metabolism. Proteomic analysis showed small particles increased expression of ferroptosis-related genes, especially Fosl1, which activates p53, suppresses Slc7a11, and drives ferroptosis through iron buildup, glutathione loss, GPX4 inactivation, and lipid peroxidation. Blocking Fosl1 or using Ferrostatin-1 reduced these effects. Large particles instead activated the YAP pathway, triggering cytoskeletal changes, shifting metabolism toward anaerobic glycolysis, and promoting inflammation [55].

Among ICR mice exposed to polyethersulfone nanoplastics (50 nm) and microplastics (5 µm) over 6 weeks, foodborne micro- and nanoplastics (5 mg/kg body weight) were observed to disrupt gut microbiota, alter gut and serum metabolism, impair liver gene expression, reduce serum antioxidant activity, and cause liver damage [56]. Airborne micro- and nanoplastics (0.75 mg/kg body weight) disturbed nasal and lung microbiota, disrupted serum and lung metabolism, altered liver transcripts, impaired antioxidant activity, and led to lung injury. Polyethersulfone nanoplastics caused more severe liver or lung toxicity than microplastics, likely due to size-related effects. Overall, foodborne polyethersulfone micro- and nanoplastics may damage the gut–liver axis, while the airborne ones may impair the lung axis.

Jin et al. [57] examined the impact of polystyrene micro- and nanoplastics on male reproduction in mice. Within 24 h, 4 μm and 10 μm polystyrene particles accumulated in the testes, while 0.5 μm, 4 μm, and 10 μm particles entered various testicular cells in vitro. After 28 days of exposure to 10 mg/mL polystyrene particles administered by oral gavage once daily, sperm quality and testosterone levels in mice declined. Histological analysis revealed disordered spermatogenic cells, cell loss, and multinucleated gonocytes in seminiferous tubules. Polystyrene particles also triggered testicular inflammation and disrupted the blood–testis barrier [57]. Overall, polystyrene particles impaired male reproductive function, highlighting their potential toxicity in mammals.

Yang et al. [58] investigated the toxicokinetics of microplastics and nanoplastics in mammals. Mice were orally given 100 nm, 3 μm, or 10 μm fluorescent polystyrene beads at 200 mg/kg body weight, and fluorescence levels in blood, fat tissues, brain regions, and reproductive organs were measured up to 4 h post-exposure using small-animal imaging. After controlling for dye leaching and pH effects, significant fluorescence increases were detected in multiple tissues for 100 nm beads, while 3 μm beads showed changes only in the cerebellum and testis at 4 h; 10 μm beads showed minimal distribution [58]. A study in C57BL/6 male mice found that daily oral exposure (40 mg/kg/d) to polystyrene nanoplastics (80 nm) and microplastics (5 µm) for 60 days reduced spermatocyte numbers in the seminiferous tubules after both treatments [59]. Gene expression profiling identified 1794 shared differentially expressed genes among polystyrene nanoplastic groups and 1433 shared differentially expressed genes among polystyrene microplastic groups. GO and KEGG analyses showed 349 overlapping and several distinct pathways: 348 unique to polystyrene nanoplastics and 526 unique to polystyrene microplastics. Functionally, polystyrene nanoplastics mainly affected retinoic acid metabolism, while polystyrene microplastics influenced pyruvate and thyroid hormone metabolisms.

Table 1 and Table 2 summarize the toxic effects of nanoplastics on mouse models and the comparison of the toxic effects between nanoplastics and microplastics.

Table 1.

Summary of the toxic effects of nanoplastics on mouse models.

Table 2.

Comparison of the toxic effects of nanoplastics with microplastics using mouse models.

3.1.7. Implications

Nanoplastics exhibit significant toxicity in mammals, affecting multiple organs and systems by penetrating biological barriers and accumulating in tissues. Studies in mouse and rat models have shown that polystyrene nanoplastics can cross the blood–brain barrier, accumulate in neurons, and trigger neurotoxicity characterized by oxidative stress, microglial activation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and synaptic disruption [33,35,36]. Behavioral impairments, including reduced locomotor activity and learning deficits, have also been observed, alongside Parkinson’s disease-like neurodegeneration [33,47], though one study reported negligible behavioral and weight changes upon exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics (35 nm), perhaps due to the lower doses used [31]. Beyond the brain, nanoplastics accumulate in the liver, kidneys, intestines, and pancreas, where they induce oxidative stress, inflammation, necroptosis, and metabolic dysregulation such as impaired glucose regulation and lipid accumulation [37,40,56]. In the reproductive system, nanoplastics disrupt spermatogenesis, reduce hormone levels, and damage ovarian follicles through oxidative stress and apoptosis, ultimately impairing fertility [50,51,53]. Transgenerational studies further highlight their risks, showing that maternal exposure during pregnancy and lactation can cause developmental, metabolic, and neurophysiological defects in offspring, suggesting long-term systemic consequences [48,49].

When compared to microplastics, nanoplastics generally display greater toxicity in mammals due to their smaller size, higher cellular uptake, and broader tissue distribution. Evidence from multiple studies indicates that smaller polystyrene nanoplastics (25–100 nm) show enhanced cellular uptake, broader systemic and brain distribution, and stronger induction of oxidative stress, inflammation, and neurotoxicity than their larger microplastic counterparts [54,56]. For instance, while both microplastics and nanoplastics accumulate in the kidneys and testes, nanoplastics penetrate more deeply into cells and organelles, causing more pronounced oxidative damage, ferroptosis, and metabolic disruptions. Microplastics tend to induce mechanical injury and cytoskeletal alterations, whereas nanoplastics act at the molecular level, directly interfering with mitochondrial function and signaling pathways such as RIPK3/MLKL and PINK1/Parkin. Toxicokinetic studies show that 100 nm nanoplastics are rapidly distributed across multiple organs, including the brain and reproductive system, while larger 3–10 μm microplastics exhibit limited or delayed biodistribution [55,58]. Comparative gastrointestinal studies also revealed that nanoplastics activate ferroptosis-related genes, whereas microplastics mainly trigger YAP pathway–mediated structural and metabolic changes. Overall, both particle types are harmful, but nanoplastics pose a higher toxicological risk because they can cross barriers, accumulate systemically, and disrupt cellular homeostasis at lower exposure levels. When nanoplastics and microplastics are both reported to harm animals, different mechanisms may be involved, as seen in their adverse effects on spermatocytes in mice [59].

Across the summarized studies, the oral, or waterborne exposure doses for nanoplastics (mostly polystyrene) ranged approximately from 0.01 mg/day to 250 mg/kg body weight/day, or 0.1–10 mg/L when administered in drinking water, and up to 200 mg/kg in a single high-dose PET study. These are orders of magnitude higher than current estimates of environmental or dietary human exposure, which typically fall within the nanogram-to-microgram per kilogram per day range (i.e., 10−6–10−3 mg/kg/day), depending on region and diet. However, some studies have indicated ingestion rates as high as 13 to 23.7 mg/kg/day per capita [60,61]. While some of the studies reviewed used doses higher than 25 mg/kg/day, they generally aimed to provide conservative estimates of the wide-ranging nanoplastic or microplastic exposure globally and the increasing severity of plastic pollution.

3.2. Crustaceans

Contino et al. [62] investigated the sublethal effects of amino-modified polystyrene nanoplastics (50 nm and 100 nm) on Artemia salina (Linnaeus, 1758), a key aquatic species. The larvae of A. salina were exposed to 10 and 20 mg/L of nanoplastics for 48 h. While no lethal effects were observed, nanoplastics accumulated in the body and caused malformations in the gut and body size, increased apoptosis, and elevated oxidative stress. These effects were more pronounced with higher concentrations and smaller particle sizes, highlighting a size-dependent toxicity [62].

Mishra et al. [63] also evaluated the toxicity of polystyrene nanospheres on A. salina and human blood cells. After 48 h in lake and seawater, polystyrene particles grew nearly 8-fold in size, reaching a range of 561 to 900 nm, which indicates aggregation. The acute toxicity of polystyrene nanoplastics on adult A. salina was assessed across a range of concentrations over 24 h: 0.5, 1, 10, 50, 100, 150, and 200 μg/mL. Toxicity tests showed LC50 values of 4.82–8.79 μg/mL for A. salina and 75 μg/mL for lymphocytes. At 50 μg/mL, about half of the lymphocytes showed genotoxic effects, including tri- and multinucleated cells. Cytotoxicity in red and white blood cells reached 50% only at 100 μg/mL. In A. salina, polystyrene nanoplastic exposure led to reduced total protein, glutathione, and catalase, along with increased lipid peroxidation, indicating oxidative stress and tissue damage [63].

Kim et al. [64] explored how nanoplastics are transferred through marine food chains and their effects on predators. Artemia franciscana (Kellogg, 1906) (brine shrimp) exposed to polystyrene nanoplastics (190 nm, at 1 mg/L in a 50 mL culture) were fed daily to Larimichthys polyactis (Bleeker, 1877) (small yellow croaker) for eight days. The findings revealed that sub-acute trophic exposure to nanoplastics led to reduced growth, significant liver damage, and impaired swimming ability. Notably, swimming behavior, including general activity and thigmotaxis, was substantially disrupted [64]. These results highlight that even indirect exposure to nanoplastics through the food chain can trigger neurotoxic effects and compromise motor function in fish.

In addition, Machado et al. [65] examined the acute toxicity of amino-functionalized polystyrene nanoparticles (50 nm) on A. franciscana larvae under varying conditions and developmental stages. Nauplii at instar II and III stages were exposed to nanoplastic concentrations ranging from 0.005 to 5 μg/mL for 48 h, with and without water agitation to simulate environmental conditions. Toxic effects were only observed at the highest concentration (5 μg/mL), with similar larval immobility rates under both static and agitated conditions (~61–65%). Instar III larvae were more vulnerable, showing 38.2% immobility after 24 h [65]. Microscopy revealed time- and dose-dependent nanoplastic accumulation in the gut.

Sendra et al. [66] evaluated how A. franciscana digests and accumulates polystyrene nanoplastics at low concentrations (0, 0.006, and 0.6 mg/L), and whether polystyrene nanoplastics affect microalgae ingestion. Artemia were exposed to polystyrene nanoplastics alone or with microalgae for 3.5 or 24 h, followed by feeding (2 h) and depuration (24 h) tests. Over 90% of polystyrene nanoplastics were ingested and accumulated in various body parts, including the gut and appendages, after 24 h. Polystyrene nanoplastics did not interfere with microalgae consumption. Post-exposure feeding showed ~70% microalgae ingestion in all groups except for previously starved Artemia, which consumed ~90%. Polystyrene nanoplastics remained in the gut after 24 h, indicating incomplete elimination [66].

A study examined the time-dependent effects of amino-modified polystyrene nanoparticles (50 nm) on A. franciscana after short-term (48 h) and long-term (14 days) exposure at concentrations of 0.1–10 μg/mL in natural seawater [67]. Short-term exposure reduced growth and development in a dose-dependent manner, while long-term exposure decreased survival but did not affect feeding or growth. Oxidative stress was evident, with antioxidant enzyme activity decreasing early and lipid peroxidation increasing over time. The nanoplastics also reduced cholinesterase activity, indicating neurotoxicity, as well as inhibited carboxylesterase, potentially disrupting hormone metabolism related to development and molting. Gene expression related to cell protection, growth, and molting was also altered across both exposure durations [67].

In a 14-day toxicity test exposing 40 nm anionic (carboxyl-functionalized) and 50 nm cationic (amino-functionalized) polystyrene nanoparticles to A. franciscana. it was reported that carboxyl-functionalized polystyrene nanoplastics, which formed micro-scale aggregates (>1 μm), had no impact on growth up to 10 μg/mL but were taken up and later excreted [68]. In contrast, amino-functionalized polystyrene nanoplastics formed smaller aggregates (<200 nm) and were highly toxic, with an LC50 of 0.83 μg/mL. At 1 μg/mL, these particles significantly increased the expression of the clap and cstb genes, which are linked to molting and stress, indicating physiological disruption and possible activation of apoptosis via a cathepsin L-like protease [68].

Hsieh et al. [69] examined how different doses (0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 µg/g shrimp) of polystyrene nanoplastics (50 nm) affect the immune system, oxidative stress, and survival of Litopenaeus vannamei (Boone, 1931). Shrimp were exposed for 7 days, during which survival was monitored daily, and immune, antioxidant, and histopathological analyses were conducted. Results showed that higher polystyrene nanoplastic doses significantly reduced shrimp survival. Phagocytic activity decreased, while respiratory burst activity increased across all exposure levels. Superoxide dismutase activity declined significantly at higher doses (>0.2 µg/g), whereas catalase activity, superoxide dismutase and catalase gene expression, and malondialdehyde levels increased. Histological examination revealed damage to muscle, hepatopancreas, midgut gland, and gills, indicating polystyrene nanoplastics-induced tissue toxicity [69].

Wang et al. [70] found that nanoplastics (80 nm) affect juvenile Procambarus clarkii (Girard, 1852) differently depending on concentration. At 10 mg/L, they triggered antioxidant and non-specific immune responses and disrupted energy metabolism and oxidative phosphorylation. Higher concentrations (20 and 40 mg/L) caused immune system damage, oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, and apoptosis, and interfered with ion transport and osmoregulation. Overall, nanoplastics inhibited growth and induced oxidative damage in a dose-dependent manner.

Pikuda et al. [71] examined how sublethal exposure to carboxylated polystyrene nanoplastics (20 nm and 200 nm) affected Daphnia magna (Straus, 1820) over 21 days. The test included 50 mg/L of both particle sizes and 0.1 mg/L of the 20 nm particles. Results showed that even low concentrations (0.1 mg/L) of 20 nm particles negatively affected growth, molting, and reproduction, indicating chronic toxicity across sizes and doses. Specifically, polystyrene nanoplastics suppressed growth in exposed organisms across both particle sizes and concentrations. Exposure to 20 nm particles notably delayed reproduction, while 200 nm particles caused delayed molting and fewer molting events over the 21-day period [71]. Similarly, Pochelon et al. [72] examined the behavior and toxicity of amidine-modified polystyrene nanoplastics (20–100 nm) in freshwater and synthetic media using D. magna. Across exposure concentrations (0.5–30 mg/L, up to 100 mg/L for 100 nm particles), smaller nanoplastics (20–40 nm) remained more stable in the presence of natural organic matter, whereas larger ones (60–100 nm) tended to aggregate. All particle sizes caused acute immobilization in D. magna within 48 h, with toxicity increasing as particle size decreased. Water chemistry factors such as pH, ions, and dissolved organic carbon had a comparatively minor influence on toxicity.

Using palladium-doped 200 nm polystyrene nanoparticles, a study examined multigenerational effects on D. magna across four 21-day exposure cycles (F0–F3) at 0.1 and 1 mg/L [73]. In contrast to the studies above, no significant effects were observed at 0.1 mg/L, while exposure to 1 mg/L increased fertility but reduced body size and lipid content in F3 offspring. Nanoparticle accumulation reached 105–503 ng/mg in adults and 621–823 ng/mg in offspring, indicating generational transfer and size-dependent physiological impacts.

3.2.1. Comparative Studies

Although direct comparisons of microplastic and nanoplastic toxicity in crustaceans are lacking, a study has explored the effects of nanoplastics of varying sizes, up to 1 µm (a particle size in the borderline). Han et al. [74] assessed how nanoplastics of different sizes (75, 500, 1000 nm) and concentrations (2.5, 10 mg/L) affect gut health in Chiromantes dehaani (H. Milne Edwards, 1853). Smaller particles (75 nm) favored pathogenic bacterial growth, while nanoplastics overall disrupted gut function. Low nanoplastic levels increased total cholesterol, whereas high levels reduced triglycerides and cholesterol. Nanoplastics inhibited lipase and amylase activity, with 500 nm particles causing the greatest inhibition. Apoptosis was promoted by reduced Bcl2 and elevated caspase gene expression, particularly at high concentrations; 75 nm nanoplastics most strongly induced cell apoptosis. Nanoplastics also triggered inflammation, marked by increased pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL1β, IL6, IL8) and decreased IL10, with 500 nm nanoplastics exerting the strongest inflammatory effect [74]. Overall, nanoplastics impaired gut microbiota, reduced microbial diversity, inhibited digestion, induced apoptosis, and caused inflammation, with 500 nm nanoplastics most detrimental to metabolism and immunity, and 75 nm nanoplastics most potent in triggering apoptosis.

Moreover, Pashaei et al. [75] assessed the acute toxicity of 0.1 µm polystyrene nanoplastics and 20 µm polystyrene microplastics on D. magna over a 48 h exposure period at concentrations of 10–400 mg/L. Mortality increased with concentration for both particle types, with nanoplastics causing complete (100%) mortality at 400 mg/L, while microplastics induced a lower but significant mortality rate of 50% at the same concentration.

3.2.2. Implications

Nanoplastics exert a broad range of toxic effects on crustaceans, primarily through oxidative stress, immune suppression, developmental disruption, and tissue damage. In Artemia species, exposure to amino- and carboxyl-functionalized polystyrene nanoparticles has been linked to gut malformations, reduced growth, altered molting, apoptosis, and neurotoxicity [63,65,66,68]. These effects are often size- and concentration-dependent, with smaller particles and amino-functionalized forms showing the highest toxicity. Beyond Artemia, studies in shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) and crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) have shown that nanoplastics can impair immune defenses, reduce survival, disrupt energy metabolism, and damage key organs such as the hepatopancreas, midgut gland, and gills [69,70]. Nanoplastics exert both acute and chronic toxic effects on D. magna, even at relatively low concentrations. Smaller particles (≤40 nm) are more stable, bioavailable, and toxic, disrupting growth, molting, and reproduction, while larger particles show lower but still measurable impacts [71,72]. Chronic and multigenerational exposures indicate potential for bioaccumulation and transgenerational transfer, leading to physiological alterations such as reduced size and lipid content in offspring [75]. Overall, nanoplastic toxicity in Daphnia appears to be size-dependent, persistent, and capable of affecting population-level fitness over successive generations. Collectively, these findings highlight that nanoplastics compromise crustacean health by interfering with fundamental physiological, developmental, and immune processes.

Although direct comparisons between microplastics and nanoplastics in crustaceans are limited, available evidence suggests that nanoplastics generally induce more severe and systemic effects due to their smaller size and higher cellular uptake. For instance, a study on differently sized nanoplastics (75–1000 nm) revealed that smaller particles favored apoptosis and pathogenic bacterial growth, while larger ones disrupted metabolism and digestion more strongly [74]. This contrasts with the typical toxicity profile of microplastics, which are more likely to cause mechanical damage, reduced feeding efficiency, or gut blockage rather than penetrating cells.

3.3. Fish Models

Zebrafish, Danio rerio (Hamilton, 1822), is a popular fish model for studying micro- and nanoplastic toxicity. Sun et al. [76] used zebrafish to examine the toxic effects of an environmentally relevant level (1 mg/L) of polystyrene nanoplastics (50 nm). Behavioral tests showed increased anxiety and depression-like responses. Tissue analysis revealed brain damage, inflammation, oxidative stress, hormonal imbalance, and gonadal injury. Gene expression analysis confirmed that polystyrene nanoplastics disrupt the brain-pituitary-gonadal axis, leading to reproductive toxicity with differences between sexes.

A study examined neurobehavioral changes, tissue distribution, and health risks in adult zebrafish exposed to 0.5 and 1.5 ppm of polystyrene nanoplastics (~70 nm) over 7 days and 7 weeks (for circadian rhythm) [77]. Polystyrene nanoplastics accumulated in the brain, liver, intestine, and gonads, with distribution influenced by particle size and shape. Exposure disrupted lipid and energy metabolism, induced oxidative stress, and led to notable behavioral changes, including altered locomotion, aggression, shoaling, predator avoidance, and circadian rhythm. Neurotransmitter biomarkers were significantly affected after one week, indicating potential neurotoxicity. After a month, fluorescence analysis confirmed polystyrene nanoplastic accumulation, especially in the gonads, suggesting possible impacts on reproduction [77].

Elizalde-Velázqueze et al. [78] evaluated the innate immune response of adult fathead minnow, Pimephales promelas (Rafinesque, 1820), exposed to polystyrene nanoplastics (50 nm) by analyzing expression of immune-related genes (ncf, nox2, mst1, and c3) in the liver and head kidney. Fish were exposed via intraperitoneal injection (5 µg/L) and ingestion (Daphnia exposed to nanoplastics). After 48 h, nanoplastics were detected in both organs and caused significant downregulation of ncf, mst1, and c3, indicating immunotoxic effects. Notably, ncf expression in the liver showed significant variation between exposure methods [78]. These findings suggest that polystyrene nanoplastics can impair key immune functions in fish through realistic exposure routes.

Wang et al. [79] examined how polystyrene nanoplastics (100 nm) affect intestinal health and growth in juvenile orange-spotted groupers, Epinephelus coioides (Hamilton, 1822). Polystyrene nanoplastics were absorbed by the liver and intestines upon exposure to 300 and 3000 μg/mL polystyrene nanoplastics. After 14 days, digestive enzyme activities (lipase, trypsin, and lysozyme) declined, indicating impaired digestion. Polystyrene nanoplastics also disrupted gut microbiota by reducing diversity, simplifying microbial networks, and increasing harmful bacteria like Vibrio and Aliivibrio. Microbial community assembly shifted from deterministic to stochastic processes. Additionally, specific growth rates decreased significantly with higher polystyrene nanoplastic concentrations, from 0.095% growth in 300 µg/L treatment to 0.074% growth in 3000 µg/L treatment [79].

Pang et al. [80] exposed larval tilapia to 100 nm polystyrene nanoplastics (20 mg/L) for 7 days, followed by a 7-day recovery in clean water, to assess transcriptomic and metabolomic toxicity. Exposure led to 2152 differentially expressed genes and 203 altered metabolites, indicating disruptions in glycolipid, energy, and amino acid metabolism, as well as signaling pathways. Inflammatory responses were suggested by changes in adhesion molecule-related genes. Despite the recovery period, lasting effects were observed, with olfactory-related processes being the most severely affected [80].

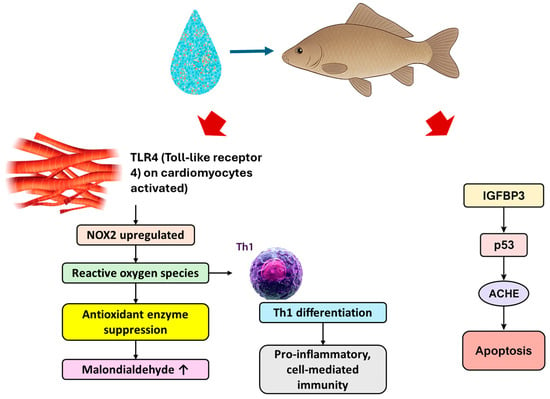

Carps were exposed for 28 days to polystyrene nanoparticles (1000 μg/L) of 50, 100, and 400 nm for 28 days [81]. All sizes caused myocardial inflammation and cardiomyocyte apoptosis, with the smallest particles (50 nm) producing the most severe damage. Polystyrene nanoplastic exposure elevated TLR4 and NOX2 levels, increased reactive oxygen species, reduced antioxidant enzyme activity (catalase, superoxide dismutase-1, glutathione peroxidase-1), and raised malondialdehyde content, with effects intensifying as particle size decreased (Figure 3). Smaller particles also shifted the immune balance from Th2 to Th1 dominance and upregulated IGFBP3/p53/ACHE apoptosis-related genes [81]. Findings indicate size-dependent oxidative stress-driven cardiac inflammation and apoptosis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

TLR 4 activation causes NOX2 upregulation, leading to excessive production and accumulation of reactive oxygen species. This, in turn, causes antioxidant enzyme suppression and oxidative damage, indicated by elevated malondialdehyde. Reactive oxygen species also stimulate Th1 differentiation and drive pro-inflammatory immunity. IGFBP3 (Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein 3) activates p53, a key tumor suppressor and stress response protein. p53 then upregulates ACHE (acetylcholinesterase), which contributes to apoptotic signaling.

A study exposed juvenile largemouth bass, Micropterus salmoides (Lacepede, 1802), to 10 and 100 μg/L polystyrene nanoplastics (100 nm) for 7 and 19 days to assess growth, oxidative stress, histology, and gut microbiota [82]. Growth remained unaffected, but notable tissue alterations occurred in gills (hyperplasia, curvature), liver (hypertrophy, vacuolization), and intestines (villus changes, reduced goblet cells). After 19 days, liver superoxide dismutase and catalase activities were significantly elevated in the high-dose group, while malondialdehyde increased only on day 7, showing no difference by day 19.

3.3.1. Comparative Studies

Yang et al. [83] compared the toxicity of nanoplastics (70 nm) and microplastics (50 μm) in goldfish larvae exposed to 10, 100, and 1000 μg/L for 1, 3, and 7 days. Both particle sizes accumulated in the digestive tract, with high concentrations causing oxidative stress, tissue damage in the intestine, liver, and gills, elevated heart rate, and reduced growth and swimming speed. Notably, nanoplastics penetrated muscle tissue via the epidermis, damaging muscle fibers, disrupting nerves, inhibiting acetylcholinesterase activity, and impairing movement more severely than microplastics [83]. Ding et al. [84] assessed size-dependent effects of polystyrene nano- and microplastics (0.3, 5, and 70–90 μm, at 95, 92 and 112 µg/L, respectively) on red tilapia. After 14 days, larger particles (70–90 μm) accumulated most. Microplastics (5 and 70–90 μm) induced stronger oxidative stress than nanoplastics. Polystyrene nanoplastics notably inhibited CYP3A-related enzymes, while liver CYP enzymes were less responsive to microplastics. In the brain, only 5 μm microplastics significantly reduced acetylcholinesterase activity. Metabolomics revealed 31, 40, and 23 altered metabolites for 0.3, 5, and 70–90 μm exposures, respectively, with tyrosine metabolism consistently affected [84]. Overall, μm-sized particles caused greater physiological stress than nanoplastics.

Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758), were exposed to polystyrene particles (80 nm, 2 µm, 20 µm) at 100 µg/L for 28 days to assess respiratory effects [85]. All sizes caused respiratory damage, which was more severe with 2 µm and 20 µm particles. This correlated with the upregulation of egln3 and nadk and the downregulation of isocitrate. Transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses indicated tricarboxylic acid cycle disruption and enrichment of cytokine and chemokine pathways, particularly for micro-sized particles. While nano-sized particles could penetrate the gill epithelium, they were largely cleared via circulation [85]. Another study exposed juvenile discus fish, Symphysodon aequifasciatus (Pellegrin, 1904), for 96 h to microfibers (900 µm) or nanoplastics (~88 nm) at 0, 20, and 200 µg/L [86]. Plastic type and concentration did not affect gut accumulation. Microfibers impaired growth, while nanoplastics reduced swimming and predatory performance. Nanoplastics activated brain acetylcholinesterase, whereas both plastics inhibited butyrylcholinesterase. Neurotransmitter levels rose in the brain but fell in the gut after exposure. Gut microbiota showed higher richness with microfibers. Proteobacteria decreased under nanoplastic treatment but increased under microfiber treatment. Clostridia and Fusobacteriia (e.g., Bacillus), linked to neurotransmitter secretion, increased with nanoplastics but declined with microfibers. Brain transcriptomics revealed altered expression of neural activity genes, with enrichment of neuroactive ligand-receptor and serotonergic synapse pathways for both plastics, and dopaminergic synapse pathway only for microfibers [86].

However, Li et al. [87] reported that adult zebrafish chronically exposed to polyethylene micro- (13.5 µm) and nanoplastics (70 nm) for 21 days demonstrated neurotoxicity and gut microbiota disruption, but no significant difference was observed between microplastics and nanoplastics. In a different study, common carp were exposed to 100 mg/L polyethylene plastics of different sizes [macro- (>5 mm), micro- (>100 nm and <5 mm), and nano- (<100 nm)] at 100 mg/L for 15 days to evaluate neurotoxicity [88]. Brain biomarkers, namely acetylcholinesterase, monoamine oxidase, and nitric oxide, decreased by 30–40%, with effects intensifying as particle size decreased (nanoplastics > microplastics > macroplastics). Histological analysis revealed necrosis, fibrosis, edema, capillary alterations, and tissue degeneration in the tectum, while the retina showed necrosis, vacuolation, and inner layer deformation [88].

Chu et al. [89] exposed rare minnows, Gobiocypris rarus (Ye and Fu, 1983), to polystyrene microplastics (1 μm) and nanoplastics (100 nm) at 1 and 10 mg/L to assess growth, tissue damage, oxidative stress, gut microbiota, and metabolism using chemical and multi-omics analyses. Both particle types reduced growth, caused histopathological lesions, and heightened oxidative stress, with effects varying by size and concentration. Core gut microbiota shifted significantly, especially under high microplastic exposure, while high nanoplastic exposure notably reduced richness and diversity. Network analysis showed major alterations in keystone bacterial genera compared to controls [89].

Furthermore, Chen et al. [90] examined how microplastics (45 µm) and nanoplastics (50 nm), both directly and indirectly, affect the locomotion of zebrafish larvae. Zebrafish larvae were exposed to 1 mg/L of microplastics or nanoplastics for 48 and 72 h. The findings indicated that microplastics had minimal impact, apart from an increase in the expression of the visual gene zfrho. In contrast, nanoplastics caused a 22% decrease in larval movement during the final dark phase, reduced body length by 6%, suppressed acetylcholinesterase activity by 40%, and significantly increased the expression of gfap, α1-tubulin, zfrho, and zfblue genes [90]. Table 3 summarizes the toxic effects of nanoplastics on fish and their comparison with those of microplastics.

Table 3.

Summary of recent studies on the toxic effects of nanoplastics in fish.

3.3.2. Implications

Nanoplastics exert significant toxic effects on fish, impacting behavior, physiology, and organ systems in a size- and dose-dependent manner. Studies in zebrafish have shown that exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics disrupts the brain-pituitary-gonadal axis, leading to reproductive toxicity, alongside behavioral impairments such as increased anxiety, depression-like responses, and altered locomotion [76,77,90]. Nanoplastics accumulate in multiple tissues, including the brain, liver, intestine, gonads, and heart, causing oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, and metabolic disruption [77,91]. Similar findings in other fish species, such as tilapia, groupers, carps, and largemouth bass, indicate that nanoplastics impair digestion, disrupt gut microbiota, induce immune suppression, and trigger cardiotoxicity [79,80,81,82]. Even after short-term exposures, nanoplastics can produce long-lasting transcriptomic and metabolomic changes, particularly affecting neurological and olfactory pathways [80,92]. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that nanoplastics pose a broad and systemic threat to fish health by interfering with vital biological functions.

Comparative studies suggest that both microplastics and nanoplastics negatively affect fish, but their modes of toxicity and severity often differ. Microplastics tend to cause mechanical stress, gut blockage, respiratory damage, and oxidative stress at higher concentrations, while nanoplastics penetrate tissues more easily, leading to stronger neurotoxic, immunotoxic, and reproductive effects. For example, in goldfish larvae, nanoplastics damaged nerves, suppressed acetylcholinesterase activity, and impaired movement more severely than microplastics [83]. However, some evidence indicates microplastics may induce stronger oxidative stress and respiratory damage, particularly at larger particle sizes, as seen in tilapia [84,85]. At least one study reported similar levels of toxicity across both particle sizes, with severity often depending on species, exposure route, and concentration [87]. Overall, while both forms of plastic pollution are harmful, nanoplastics are generally more potent in inducing cellular and molecular damage, whereas microplastics more strongly disrupt physiological functions linked to size and accumulation.

3.4. Bivalves

Palladium-doped polystyrene nanoplastics (139.5 nm, 43.8 mV) were used to quantify accumulation in Ruditapes philippinarum (Adams and Reeve, 1850) and assess toxicity via physiological measurements, a toxicokinetic model, and 16S rRNA sequencing [93]. After 14 days, nanoplastic levels reached 17.2 mg·kg−1 at environmentally realistic (0.02 mg·L−1) and 137.9 mg·kg−1 at ecologically relevant (2 mg·L−1) exposures. High concentrations reduced antioxidant capacity, triggered the production of excess reactive oxygen species, and induced lipid peroxidation, apoptosis, and tissue damage. Uptake and elimination rate constants from the pharmacokinetic model were inversely related to short-term toxicity. While realistic concentrations caused no overt toxicity, they significantly altered intestinal microbiota composition [93].

Arini et al. [94] compared the toxicity of nanoplastics from fragmented coastal debris (nanoplastics-G, which contained polyethylene and polypropylene) (280 nm) and commercial polystyrene nanoplastics (260 nm) on Caribbean swamp oysters, Isognomon alatus (Gmelin, 1791), with or without arsenic (1 mg·L−1) co-exposure. Oysters were exposed to 7.5 or 15 μg·L−1 nanoplastics for one week before gene-level analysis. Nanoplastics-G induced stronger molecular changes than polystyrene nanoplastics, particularly with arsenic. Both nanoplastic types, alone or with arsenic, altered mitochondrial metabolism (up to 11.6-fold upregulation), suppressed antioxidant genes cat and sod1 (down to 0.01-fold), and markedly upregulated apoptotic markers p53 and bax (up to 59.3-fold in nanoplastics-G + As) [94].

Repeated exposure to amino-modified polystyrene nanoparticles (50 nm) was tested in Mytilus galloprovincialis (Lamarck, 1819) through two treatments (10 μg/L for 24 h each) separated by a 72 h depuration period [95]. Immune responses were assessed in hemocytes, serum, and hemolymph. The first exposure altered mitochondrial and lysosomal activity, reduced serum lysozyme activity, and changed gene transcription, including upregulation of extrapallial protein precursor and downregulation of lysozyme and mytilin B. These changes suggested cellular stress but did not impair overall bactericidal activity. After re-exposure, hemocyte subpopulations shifted, functional parameters returned to baseline, and bactericidal activity increased, accompanied by upregulation of most immune-related genes encoding secreted proteins [95].

Liu et al. [96] examined the toxicity of amino- and carboxyl-modified polystyrene nanoparticles on Meretrix meretrix (Linnaeus, 1758) across multiple biological levels at environmentally relevant concentrations (0.02–2 mg/L). Both nanoplastics were non-lethal but suppressed clam growth, largely due to energy imbalance caused by nanoplastic-induced inflammation and bioaccumulation in digestive glands. Growth inhibition was further linked to impaired immune function, with reduced phagocytosis from lysosomal membrane destabilization. Genotoxicity arose from disrupted energy metabolism involving pancreatic secretion, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and peroxisome proliferator activated-receptor α signaling, as well as immune dysregulation through altered TLR, NF-κB, phagosome, and lysosome pathways [96].

Additionally, Wang et al. [97] examined the effects of polystyrene nanoplastics (100 nm) on the gill physiology of the mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis after 7 days of exposure (0.5 mg/L and 5 mg/L). Nanoplastics increased total antioxidant capacity and inhibited acetylcholinesterase activity, while disrupting ion balance, suppressing Na+/K+-ATPase activity, and altering key metabolic enzymes (pyruvate kinase and succinate dehydrogenase) and lipid levels. These findings indicate that polystyrene nanoplastics interfere with oxidative balance, ion regulation, and energy metabolism in marine invertebrate gills.

3.4.1. Comparative Studies

In an early study, Pacific oyster [Magallana gigas (Thunberg, 1793)] larvae (3–24 days post-fertilization) were exposed to polystyrene particles (70 nm–20 μm) with varying surface properties to assess effects on feeding and growth [98]. Ingestion rates over 24 h depended on larval age, particle size, and surface chemistry, with aminated particles consumed and retained more often. Plastic ingestion strongly correlated with particle load. Exposure to 1 and 10 μm particles for up to 8 days at <100 particles/mL showed no significant impact on feeding or growth. Oyster larvae were capable of internalizing nano-sized polystyrene (<1 μm). It was unclear whether particles larger than 160 nm crossed the gut epithelium [98]. Overall, larvae readily ingested micro- and nanoplastics, but environmentally unrealistic concentrations used in the study caused no detectable developmental or feeding effects.

Latchere et al. [99] compared the toxicity of polystyrene nanoplastics (200 nm) and environmentally derived microplastics (1.2 to 300 µm) and nanoplastics (235 nm) from Garonne River debris on the freshwater bivalve Corbicula fluminea (Muller, 1774). Organisms were exposed to 0.008, 10, or 100 μg·L−1 for 21 days, and responses were evaluated using multiple biomarkers. Environmental nanoplastics had the strongest impact, particularly on detoxification and immune functions, highlighting that laboratory use of manufactured nanoplastics may underestimate environmental risks. Environmental microplastics caused fewer effects than environmental nanoplastics, underscoring the need to assess a full size range of plastics. Some impacts occurred only at low or intermediate concentrations, stressing the value of environmentally realistic exposure levels [99].

Using Mytilus coruscus (Gould, 1861) as a model, Qi et al. [100] examined the acute toxicity of polystyrene nanoplastics (100 nm) and microplastics (1 µm) via transcriptomics, histology, and biochemistry. Mussels exposed to 10–100 mg/L polystyrene micro- and nanoplastics for 2 days efficiently ingested nanoplastics, triggering strong inflammation, while microplastics caused only mild responses. Plastic exposure upregulated multiple biochemical biomarkers, with nanoplastics inducing greater reactive oxygen species production and higher total antioxidant capacity than microplastics. Transcriptomic data showed that most differentially expressed genes were enriched in stress and immune-related pathways [100].

Capolupo et al. [101] assessed the effects of 21-day exposures to 1.5, 15, and 150 ng/L polystyrene microplastics (3 µm) and nanoplastics (50 nm) on immunological, oxidative stress, detoxification, and neurotoxic biomarkers in Mediterranean mussels, Mytilus galloprovincialis (Lamarck, 1819). Nanoplastics induced stronger lysosomal stress, elevated lipid peroxidation, and increased catalase, glutathione S-transferase, and lysozyme activities, while microplastics uniquely reduced hemocyte phagocytosis. Nanoplastics also decreased acetylcholinesterase activity, indicating possible neurotoxicity [101]. Overall, integrated biomarker analysis showed greater health impairment from nanoplastics than microplastics. Table 4 summarizes the toxic effects of nanoplastics on bivalves and their comparison with those of microplastics.

Table 4.

Summary of nanoplastic toxicity studies in bivalves.

3.4.2. Implications

Nanoplastics can exert diverse toxic effects on bivalves, impacting physiology, immunity, and gene regulation. Studies show that exposure leads to oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, apoptosis, and tissue damage, often through disruption of energy metabolism and immune signaling pathways [94,95]. Bioaccumulation in digestive tissues and destabilization of lysosomal membranes impair growth and immune defense, while even non-lethal concentrations can alter intestinal microbiota and gene expression [94,96]. Repeated exposures may trigger adaptive responses, but they also highlight the persistent stress that nanoplastics impose on cellular and systemic functions in bivalves.

Comparisons between nanoplastics and microplastics suggest that nanoplastics generally induce stronger toxic effects in bivalves. While both particle types are ingested, nanoplastics are more readily internalized and cause more severe oxidative stress, inflammation, and immunological disruption than microplastics. Some studies report that microplastics reduce phagocytosis, whereas nanoplastics cause broader cellular damage, including lysosomal stress and neurotoxicity [95,100,101]. Environmental nanoplastics, in particular, appear more harmful than manufactured ones, emphasizing that their smaller size, higher reactivity, and bioavailability make them a greater toxicological risk compared to microplastics.

3.5. Terrestrial Invertebrates

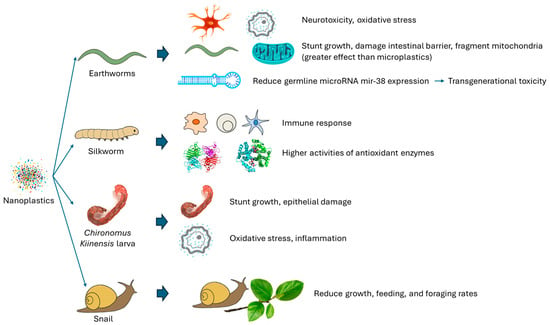

Most of the existing studies of nanoplastic toxicity on terrestrial invertebrates focus on earthworms. Jeong et al. [102] investigated how 25 nm polystyrene nanoplastics affect Caenorhabditis elegans (Maupas, 1900) by examining physiological and neurotoxic effects after a one-day exposure to concentrations of 10, 100, or 1000 µg/L. Even at low concentrations, the particles impaired the growth and movement of C. elegans, with effects influenced by their surface chemistry. Nanoplastics accumulated in the gut and also spread to other tissues, damaging the intestinal barrier and causing mitochondrial fragmentation in muscle, which likely contributed to reduced mobility (Figure 4) [102].

Figure 4.

Toxic effects of nanoplastics on terrestrial invertebrates.

Liu et al. [103] used C. elegans to compare the transgenerational toxicity of 20 nm and 100 nm polystyrene nanoparticles (Figure 4). Worms were exposed at the P0 generation, while offspring (F1–F6) were raised without further exposure. The 20 nm polystyrene nanoplastics caused more persistent toxicity, affecting movement and reproduction up to F6, while effects from 100 nm polystyrene nanoplastics lasted only until F3. The stronger toxicity of the smaller particles was linked to prolonged oxidative stress and differing transgenerational responses in antioxidant activity, mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPR), and endoplasmic reticulum UPR [103].

Also using C. elegans, Hua et al. [104] found that exposure to 1–100 μg/L polystyrene nanoparticles (20 nm) over 6 days reduced germline microRNA mir-38 expression (Figure 4). Overexpressing mir-38 mitigated transgenerational toxicity, indicating its downregulation drives this effect. In the germline, mir-38 acts by inhibiting targets NDK-1, NHL-2, and WRT-3, with NDK-1 further modulating toxicity via suppression of Ras kinase regulators KSR-1/2. Thus, reduced mir-38 promotes transgenerational toxicity of polystyrene nanoplastics through the NDK-1–KSR-1/2 signaling pathway [104].