Abstract

Maintaining air quality is an important environmental challenge, affecting both urban and regional areas where industrial, agricultural, and energy activities intersect. The Upper Hunter Valley, NSW, experiences emissions from coal mining, power generation, agriculture, and wood fires, compounded by local meteorology, geology, and climate change. This study applies a political economy framework to examine historical governance structures including colonial legacies, institutional arrangements, and power relations and how they shape stakeholder roles and influence decision-making related to air quality. Technical applied research including improving dust monitoring, occupational health studies, and investigations into alternative fuels provided an empirical basis for identifying key stakeholders, including mining and energy companies, regulatory agencies, local councils, community groups, and environmental organisations. The analysis demonstrates how these actors influence governance processes, social licence to operate, and public perceptions of environmental risk. Findings indicate that effective air quality management requires multi-level, collaborative approaches that integrate technical expertise, regulatory oversight, and community engagement. The study highlights the importance of systemic strategies that align economic, environmental, and social objectives, providing insight into the governance of contested environmental resources in historically and politically complex regional contexts. This article is a rewritten and expanded version of the study “Analysis of air quality stakeholders in the Upper Hunter”, presented at the Clean Air conference, in Hobart, Australia, August 2024.

1. Introduction

The Upper Hunter, located in the Great Dividing Range of New South Wales (NSW), Australia, spans approximately 20,000 km2 and is home to over 50,000 residents [1]. Natural resources in this region have been transformed into valuable economic products, often through conflicts over land boundaries and both formal and informal practices [2]. Mining alone supports over 30,000 full-time jobs and contributes around AUD 24 billion to the state’s economy, along with nearly AUD 6 billion in taxes and royalties. The industry also supports a network of businesses [3], and these revenues help fund government services and regional infrastructure [4], with local government programs and sponsorships further supporting the community [5]. While these economic benefits promote regional growth and reduce vulnerability, they also bring negative effects such as pollution, rising living costs, reduced housing affordability, and higher unemployment rates in marginalised communities [6].

Air quality in the Upper Hunter is influenced by topography, weather, industrial activity, and climate change [7,8], and over the last 10–15 years, particulate matter (PM) concentrations have generally exceeded national benchmarks [9,10]. Although coal mining has been identified as a significant source [9], emissions from wood smoke, vehicles, and other sources contribute to poor air quality, which is a contentious issue among local, state, and federal governments, communities, and industries [11,12]. In smaller towns like Muswellbrook and Singleton, with populations under 25,000, the issue often fails to capture significant attention at broader levels, despite the clear associated health risks [13,14]. Activist groups, such as Lock the Gate Alliance and Doctors for the Environment Australia, have been strong advocates for change, although under the main theme of climate change rather than health. With 80% of NSW’s electricity reliant on coal, strategic frameworks are being developed to manage the transition from fossil fuels [15,16].

The governance of air quality in the region represents a highly complex and contested landscape, shaped by overlapping institutions, agents, and structures across multiple scales. At the national level, regulatory authority rests with the National Environment Protection Council (NEPC), which sets the Ambient Air Quality National Environment Protection Measure (NEPM) [17], federal agencies such as Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW), which frame environmental policy, while the Department of Health, Disability and Ageing and SafeWork Australia set health and occupational health-related policy, respectively [18].

The state government through the NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA) enforces standards, the Department of Planning oversees mining approvals, and consults with the Independent Planning Commission (IPC) for state significant developments (SSD). The Resources Regulator handles safety and compliance, in consultation with SafeWork NSW, while the Treasury through Revenue NSW is responsible for managing coal royalties [19]. At the industry level, multinational coal companies and their representative bodies such as the NSW Minerals Council exert considerable influence through compliance systems, lobbying, and a central role in the economy of the region.

At the local scale, regional councils, the EPA-managed Upper Hunter Air Quality Monitoring Network (UHAQMN), community organisations (e.g., Hunter Community Environment Centre, Lock the Gate Alliance), landholders, and advocates contest both the social and environmental impacts of coal dependence. Research institutions, think tanks, and the media also pose a presence across local, regional, state, and national scale. They act as channels for generating information, sharing and disseminating it between institutions, agents, and structures, in the process shaping policy, discourse, and outcomes that also often transcend national borders. The described overlapping of institutions, agents, and structures across multiple scales produces inherent tensions between environmentally positive outcomes, health protection, and economic imperatives.

Underlying these tiers are durable structures that both constrain and enable governance outcomes. This includes the economic reliance of NSW on mining royalties, the political prominence of coal electorates, the specific topography of the region, which inhibits the flow of particulate concentrations, and entrenched cultural identities that are tied to coal mining. These tiers are reinforced by the following:

- 1.

- A national undertow of embedded colonial settler institutions which continues a legacy of inequity in political and economic relations while marginalising Indigenous voices [20];

- 2.

- The structural dependence of the region on traditional resources in the face of heightened climate change pressures and the imperative to diversify beyond fossil fuels [21]; and

- 3.

- Limited institutional capacity of local governments, which constrains their ability to address both direct impacts of mining and the restrictive effects of mining governance itself [22].

Together, these layers form an interlocking system of constraint, within which countervailing forces such as global decarbonisation pressures, research highlighting health vulnerabilities, and advocacy discourses framing air quality as a matter of justice and equity, struggle to gain traction. The result is a system of governance that is characterised by asymmetrical power relations, where community and health voices are strong in interest but often weak in formal influence, while industry actors dominate economic and political channels, and only on the surface does the government appear to be proactive.

This landscape is well-suited to a political economy analysis (PEA), which seeks to uncover how structures, institutions, and agency interact to shape outcomes [23]. It also necessitates systematic stakeholder analysis to identify who is involved, their interests, and the basis of their influence [24]. Understanding the interplay of these forces is essential to explaining why air quality remains a persistent topic of interest in the Upper Hunter, despite decades of monitoring, regulation, and contestation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Technical Solutions

The conceptualisation of this study was informed by a range of academic research projects that were entirely of a technical nature. This includes improving air quality monitoring, dust management, worker exposure, and evaluating the health impacts of PM. The approach aimed to clarify the contextual rationale for air quality research from mining, environmental, and health regulatory perspectives. The study thus represents a derivative outcome of broader stakeholder engagement initiatives undertaken to inform discourse and enhance air quality management in the Upper Hunter.

Industry-relevant insights were derived from long-term collaborations in coal preparation through the Australian Coal Association Research Program (ACARP) and Australian Standards (AS) [25] and a local mine site where low-cost sensors and Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR)-based dust monitoring was trialled as a means of improving air quality management [26,27]. Additional air quality operational perspectives were gathered through multi-disciplinary research projects addressing occupational health and safety, funded by industry bodies such as Coal Services Health and Safety Trust [28,29]. During these projects, participation in public forums, including the Upper Hunter Mining Dialogue (UHMD), provided exposure to the perspectives of mining and electricity generation companies, local councils, advocacy groups, community representatives, and different types of businesses. Technical research into alternative fuels, such as biomass and ethanol, further informed the understanding of regional diversification incentives and the potential for reduced reliance on fossil fuels [30]. Collectively, these technical inputs offered both a unique and broad foundation that indirectly shaped the scope and framing of the study.

2.2. Political Economy and Stakeholder Analysis

Politics is fundamentally about “who gets what, when, and how,” underscoring the importance of examining actors and incentives in shaping outcomes, [31]. In managing shared environmental “goods” or common-pool resources such as air quality, it is also important to explore the role of collective action, institutional arrangements, and multi-level governance, [32].

PEA and stakeholder analysis are complementary but distinct approaches to understanding complex governance and decision-making environments. PEA seeks to explain why things happen as they do by examining the structural, institutional, and power dynamics that shape incentives, behaviours, and policy outcomes. It focuses on the interaction between political and economic forces, formal and informal rules, historical legacies, and institutional arrangements that enable and/or constrain change.

PEA was adopted as a methodological lens to investigate how power, interests, and institutions shape governance around air quality in the Upper Hunter. PEA has been used as a basis for examining complex problems such as governance of climate change and development, conflict, security and justice [33,34,35]. It is particularly valuable for examining issues surrounding air quality in the Upper Hunter because it highlights how competing incentives, structural constraints, and power dynamics influence policy choices and regulatory outcomes beyond purely technical considerations.

In contrast, stakeholder analysis focuses on who is involved, identifying the individuals, groups, and organisations that have an interest in or are affected by an issue, and assessing their relationships, levels of influence, and motivations. While stakeholder analysis maps the actors and their relative power or interest, PEA situates these actors within the broader system of incentives and constraints that drive their behaviour. Used together, these methods provide a comprehensive understanding of both the contextual drivers and the actor-specific dynamics shaping both governance and policy outcomes. When applied to complex challenges such as air quality in the Upper Hunter, this is helpful in revealing the dominant voices in decision-making. Combined with a PEA, stakeholder analysis provides deeper insight into how governance structures, power dynamics, and institutional constraints shape both the opportunities and barriers to effective air quality management.

Following the framework set out in the Department for International Development (DFID) “How to Note” [23], analysis is structured across three levels:

- Foundational factors (context including historical, geographical, and socio-economic);

- Rules (formal and informal institutions that shape incentives); and

- The present (current actors, events, and decision-making processes).

The chosen DFID framework is accepted as standing the test of time [36]. To complement PEA, a stakeholder analysis drawing on the typology developed by Reed et al. [24] is implemented to distinguish stakeholders by their roles, interests, and power, and to examine why they participate in governance processes. Stakeholders were categorised using a top-down analytical approach, using interest/stake and power/influence to classifying stakeholders into key actors, context setters, crowd and subjects [37,38]. Classification was informed by the authors perspective as well as the observed stakeholder levels and forms of engagement in the implementation and communication of outcomes related to the technical solutions. The authors perspective and observations were balanced by interrogating and critically examining the relevant cited literature. Together, the PEA and stakeholder analysis approaches provide a structured basis for mapping the relationships, influence, and capacities of actors, linking contextual dynamics with the stakeholder networks shaping air quality outcomes.

The PEA approach was applied through three analytical dimensions: the structural context, the formal and informal institutions that influence behaviour, and the incentives and power relations of key actors. Here, structures refer to long-term factors that shape the political and economic context and are not easily altered, such as the historical connections between mining and the state. Institutions encompass both formal (e.g., legislation, markets) and informal (e.g., political, social, and cultural norms) elements.

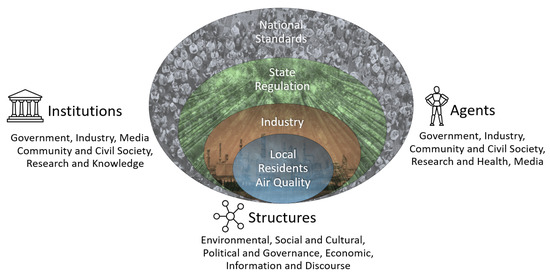

Agents are divided into internal (e.g., politicians, political parties, business associations, community organisations) and external groups (e.g., foreign NGOs, multinational corporations, regional organisations). The focus of analysis are the key questions: Who are the key stakeholders in the political economy of air quality governance in the Upper Hunter?, and, What is their influence on the governance of air quality in the region? The analysis within this article investigates the mining and resources sector through both vertical and horizontal scales [39] to identify the factors (drivers of change) and incentives for improving air quality in the short, medium, and long term [23]. A conceptual framework of the governance landscape used in this study is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Framework adopted for the Upper Hunter air quality PEA and stakeholder analysis.

The landscape is sub-divided into four tiers of primary mandate and sphere of influence:

- 1.

- National mandate or scale which involves policy, regulation and discourse at the federal or inter-state level.

- 2.

- State mandate or scale (i.e., NSW) where regulatory authority, planning and enforcement occurs;

- 3.

- Industry mandate or scale that involves operational and compliance-based influence on air quality; and

- 4.

- Local air quality mandate (i.e., Upper Hunter scale) that includes community, participatory governance, monitoring, and lived experience.

An assessment of the power dynamics arising from sectoral interactions and between various factors follows. When combined with stakeholder analysis, the framework shown provides a systematic means to map relationships, identify power asymmetries, and assess capacities, offering deeper insight into the dynamics that shape air quality governance in the region.

2.3. Identifying Stakeholders

A basis for key stakeholder identification was possible through multiple complementary engagements. As described previously, industry perspectives, were captured indirectly via long-term research collaborations. Resources for the study were directly encountered during the lifetime of the reasearch projects, in the context of developing, implementing and/or disseminating technical solutions and scientific findings. Engagement with regional, interstate, and international actors and government was further supported by participation in open forums. These engagements are summarised below:

- AS and Australian Coal Preparation Society (ACPS) technical meetings, leading to improvement and update of coal dustiness testing standard AS4156.6 [25];

- Community Consultative Committee (CCC) meetings at a local mine site, highlighting outcomes of applying more accurate air quality monitoring methods [26];

- Coal Services and Mine Safety Occupational Hygiene standing dust committee, consultation on enhancing coal dust exposure occupational monitoring [27];

- UHMD, and NSW state government, Department of Primary Industries, Planning and Environment (DPIE) workshops, presenting handling solutions for forestry waste management and use of alternative fuels such as biomass for bioenergy [30,40];

- Port Hedland Industries Council (PHIC), Pilbara producers/exporters forum, on the update of AS4156.6 coal dustiness standard and its implementation in iron ore dust management [41]; and

- Sustainable Minerals Institute, 5th annual dust and respiratory health forum, including health relevant research outcomes from coal murine models [28,29].

A diverse range of stakeholders was identified and engaged to primarily inform the assessment and management of emissions associated with mining operations. Key stakeholder groups included internal mine personnel (e.g., site engineers, technical services manager, external relations manager, mine manager, environmental superintendent, and environmental officers), local residents, community representatives, and local government staff such as environmental policy officers and technical advisors. Additional stakeholders comprised air quality scientists, policy advisors, academic researchers, consultants, environmental and biomedical scientists, retirees, business managers, small business owners, equipment suppliers, engineers, industry representatives (including personnel from the resources regulator, minerals council, and trade unions), as well as occupational hygienists, park rangers, and journalists.

Stakeholder engagement was undertaken through both written submissions and verbal communication, with the latter typically occurring through face-to-face interactions. These were conducted across a range of venues, including conference rooms, lecture theatres, public halls, Returned and Services League (RSL) clubs, hotel function rooms, town halls, shopping centres, visitor centres, university facilities, and operational areas of an open-cut mine (e.g., offices, site vehicles, and active mining zones).

This inclusive engagement process ensured that a broad spectrum of perspectives, ranging from local community concerns to technical and regulatory expertise, were incorporated into the evaluation of emissions sources, monitoring strategies, and potential mitigation measures. The approach supported a more robust and context-sensitive emissions management strategy by integrating scientific knowledge, industry practices, and community values into the decision-making process. Overall, such insight, essentially stems from a holistic multi-disciplinary research agenda that aims to enhance air quality monitoring solutions, better understand the health impacts of PM and increase transparency.

The relevant stakeholders are summarised in Table 1. They include industry associations, mining companies (and their supply chains), power producers, mining equipment technology services (METS), other businesses such as agriculture, viticulture, equine industries, service providers, air quality consultancies, as well as regional councils, community groups, business development organisations, health and safety organisations, trade unions, local, state, and federal governments, education and research institutions, advisory committees, traditional landholders and Indigenous groups, activist or advocacy organisations, local residents, media, and think tanks.

Table 1.

Identification of stakeholders and their representative entities.

3. Results, Analysis, and Discussion

Inspired by the stakeholder analysis presented in Table 2, the discussion that follows covers governance, legislation and regulation, structures, knowledge and information, and economic considerations.

Table 2.

Stakeholder Analysis.

3.1. Governance

Australia’s governance landscape is rooted in its colonial past, when at Federation in 1901, self-governing colonies united to establish a federal system that divided power between the Commonwealth and the states. This framework has since developed into three tiers: federal, state/territory, and local governments, each with distinct but sometimes overlapping responsibilities. The federal government oversees national matters such as defence, trade, taxation, immigration, and Medicare, while states and territories manage regional priorities including schools, hospitals, transport, utilities, and policing. Australia’s more than 500 local councils are responsible for community needs through by-laws and services such as waste management, local roads, parks, libraries, and town planning [42]. However, Australia’s reliance on raw resources like coal and iron ore has amplified the influence of mining companies, reshaping local government functions and straining service delivery and decision-making. These councils often compete for institutional capacity with state and federal agencies, unions, and multinational corporations [22], and while they aim to represent community interests, their limited regulatory authority over resource use constrains their effectiveness.

This fragmented, multi-layered governance environment, with overlapping and embedded organisations, impedes strategic, long-term planning and creates ambiguity around authority and accountability. Tensions between transnational policy frameworks and sub-national implementation further exacerbate this capacity gap, particularly in regional planning and development [2]. As a result, institutional capacity in Australian regional governance remains weak [22].

In mining-intensive regions, partially coordinated actor networks enable corporate interests to disproportionately shape structures of accountability and responsibility, often skewing priorities in favour of industry. Such dynamics have tangible consequences for local and regional communities, as illustrated in the Upper Hunter, where governance inconsistencies continue to challenge effective air quality management.

3.2. Legislation and Regulation

The federal government sets ambient air quality standards through the NEPM [17], which the states implement via legislation such as the Environmental Protection Licence (EPL). In practice, however, economic priorities often override health considerations, leading to subsidies that benefit polluters [43]. While compliance has been encouraged through NSW EPA pollution reduction programs [44] which incentivised the mining industry to reduce targeted emissions and adopt improved practices (e.g., [45]), these measures remain unevenly effective in assuaging scrutiny, despite alignment with best-practice dust management recommendations [46,47].

On the back of diversification away from a carbon heavy economy [15], the electricity sector has simultaneously pursued higher efficiency, renewable energy investment, emissions mitigation, and plant closures [48]. Despite this, air quality continues to reflect a trade-off between socio-economic benefits, environmental and health costs, highlighted by the stark contrast between fines of AUD 15,000 for daily emissions breaches [49] and the estimated AUD 65 million annual health burden from fine particle pollution [7], of which a significant portion is directly related to Australia’s economic reliance on mining and export of other natural resources.

Since being established in the early 2010’s, the state government, together with industry partners, oversees the UHAQMN. The UHAQMN consists of fourteen monitoring stations across the region which continuously measure airborne and gaseous pollutants and meteorological data [9,10]. Since its introduction, the UHAQMN has recorded PM concentrations exceeding national air quality standards, particularly during exceptional events such as large-scale dust storms, bushfires, and hazard reduction burns. During the first five years of operation (2012–2016), 98% of days met national standards, with exceedances recorded on 39 days. In the subsequent five-year period (2017–2021), compliance dropped to 94%, with 115 exceedance days. Notably, almost two-thirds of these occurred within a six-month window from August 2019 to January 2020, coinciding with the extreme 2019–2020 bushfire season. In addition, Muswellbrook recorded one exceedance of the one-hour sulphur dioxide (S) standard in 2016. By contrast, air quality in 2021 improved significantly, with 12 of the 14 monitoring stations recording the lowest annual average particle concentrations since monitoring commenced.

The network’s funding, administration, and maintenance are governed by the Protection of the Environment Operations (General) Regulation [50] under the Protection of the Environment Operations Act [51], both under Federal government mandate. The regional air quality data across the state, including four monitoring stations from the Upper Hunter, is reported annually by the state government [52]. Similarly, since 2012, local council and the NSW Minerals Council have together coordinated the UHMD. The UHMD is a public forum for discussing community issues related to mining, with a strong focus on air quality and the efforts of key actors to address community concerns. For example, mining companies run organised tours in which local school children are escorted through nearby mine sites. The UHMD also presents an annual detailed report on the UHAQMN, including correlation to rainfall and coal production, for which it typically engages an environmental consultancy. The most recent data indicates that PM concentrations parallel those observed elsewhere in NSW, although seven exceedances were recorded in smaller communities [53].

In addition to regulatory compliance, planning and approvals for resource development are heavily shaped by industry influence. The NSW coal sector, in particular, wields substantial political power, prioritising short-term economic returns over long-term sustainability, environmental protection, and diversification [54]. This concentration of political capital directly affects air quality governance, producing a persistent tension between economic development and public and environmental health at local, regional, and national levels.

3.3. Structures

Colonial structures have fundamentally shaped environmental governance in Australia, embedding Western notions of ownership that prioritise economic interests over collective responsibility and Indigenous land stewardship [55]. This legacy extends to conservation and resource management, where historical displacement of Indigenous peoples has excluded their ecological knowledge [56]. Although increased advocacy (e.g., [57]) highlights the importance of Indigenous-led economic development, linking equitable prosperity to recognition of sovereignty and control over land and resources, entrenched colonial and economic structures constrain air quality governance in the Upper Hunter but, more broadly, environmental and economic policy.

Air quality management in the region includes technical monitoring through the UHAQMN, coordinated by the state government with local councils and mining companies, and reported at public forums such as the UHMD. In 2024, air quality monitoring stations recorded approximately 20 daily averaged PM exceedances across NSW, with only one in the Upper Hunter [52]. Despite these measures, environmental advocacy groups, including Doctors for the Environment Australia but also grassroots organisations, have amplified public scrutiny and challenged the mining sector’s social licence to operate [58,59,60,61,62]. The influence of transnational NGOs such as WWF and Greenpeace further underscores global engagement in regional governance [60].

Government influence is constrained by technocratic approaches and competing interests, while local groups contest state- and industry-funded scientific narratives [63]. Public discourse is structured around anti-coal versus pro-renewables coalitions [64], reflecting broader colonial settler mindsets that prioritise individual economic rights over collective environmental responsibility. Effective air quality management thus requires integrated strategies combining regulation, governance, technical expertise, and civil activism to navigate mismatched authority, interests, and access across scales.

3.4. Knowledge and Information

Air quality governance and policy in the Upper Hunter is also shaped by the production of knowledge and circulation of information. Media outlets, think tanks, and research institutions mediate not only the dissemination of technical findings but also the framing of political debate and public perception. From a political economy perspective, these actors both inform and contest dominant narratives, influencing issues that gain traction and those that remain marginal as well as constructing legitimacy around environmental decision-making [65,66].

Local and national media often reproduce polarised accounts, either amplifying concerns over health and environmental risks or accentuating the economic dependence of communities on coal and power generation. The general economic dominant framing of coal mining suggests a mismatch between policy setting and the well-being of the broader public [67]. Think tanks, such as Australia Institute and the Grattan Institute, range in alignment from industry organisations to environmental NGOs. They mobilise expertise and advocacy to influence public opinion and policy agendas, often competing to define the problem, such as, for example, air quality, in ways that are consistent with their institutional priorities [68]. Research institutions, including universities and independent monitoring bodies, provide scientific assessments that underpin regulatory decisions, yet their influence is mediated by the ways findings are communicated, interpreted, and contested by other stakeholders [64]. The interdependent relationship between both state and federal governments and industry severely impacts consistency and focus, and effectively key outcomes of discourse surrounding air quality, but also more generally, prioritisation of environmental imperatives including climate change over economic interests [69,70].

This contested knowledge environment reflects deeper structural tensions. In line with PEA, asymmetries in resources and access to platforms allow well-resourced and powerful actors to exert disproportionate influence, while community groups and Indigenous voices often struggle to have their knowledge legitimised within regulatory frameworks [56,71]. As such, knowledge and information are not neutral inputs but sites of power and contestation, shaping bargaining positions, accountability mechanisms, and the credibility of governance outcomes.

3.5. Economics

The mining industry is integral to the Upper Hunter’s identity [2], yet the majority of its production, 85% of its coal output, is exported to Asia [16]. Coal export over many years parallels trends across other Australian natural resources, with the estimated life of reported conventional gas reserves sitting below 20 years [72,73]. Despite contributing modestly to employment and state GSP in 2012–2013, the coal mining sector’s economic footprint has grown, reaching 7.3% of GSP and supporting 5.6% of employment in 2022–2023 [74,75].

Lobbying and political engagement amplify the industry’s perceived importance across regional, state, and national scales, shaping public opinion and reinforcing its influence [74]. A profound tension between the economic dependence on coal mining and community’s concerns over air quality and well-being are increasingly evident [76]. Community resistance is demonstrated by strong negative views toward coal dust pollution but also a pervasive sense of disempowerment, driven by the domineering influence of government–industry alliances. With nearly 90% foreign ownership and over AUD 500 million spent on lobbying, corporate interests are deeply embedded in government decision-making processes [77]. This influence, reinforced by a “revolving door” between government and industry, too often prioritises corporate over community or environmental interests [77,78].

Consequently, policy development—including air quality regulation and broader development planning—is skewed, reducing consistency, transparency, and accountability. Despite calls for load-based licensing laws to be widened to include coal mining and related activities this has thus far not eventuated [79]. Perhaps it is of interest to consider here that other resource extraction and related activities such as crushing, grinding or separating, extractive activities, metal processing and waste generation, mining for minerals, and mineral processing and waste generation, are all also omitted from existing load-based regulation [50]. On the other hand, in more recent times, the NSW EPA has rolled out annual “Bust the Dust” campaigns with updated penalties for breaching EPL conditions of AUD 30–AUD 45,000 [80], with one mine paying over AUD 100,000 in fines in 2023. The alignment of economic, political, and corporate interests thus reinforces systemic power imbalances, shaping governance outcomes from local to national scales. Adding to this, rising housing costs have produced a hyper-inflated economy in which home ownership, once a standard aspiration for people in their mid-20s, has become largely unattainable within one generation [81,82]. Juxtaposed with the difficulty of aligning economic prosperity with environmental outcomes for the coal industry, such as air quality, is a reflection of policy cycles of subsidies and taxation that shift with changes in government.

3.6. Discussion

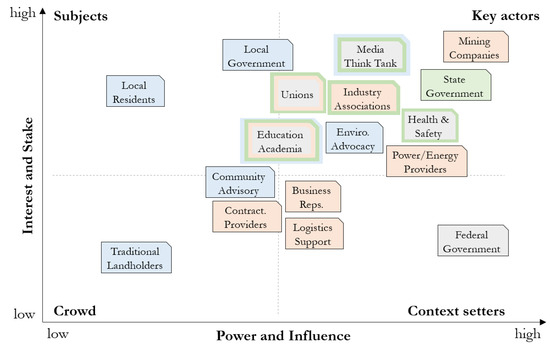

Building on the previous sections and the analysis presented in Table 2, and following the methodology outlined in [24], stakeholders in the Upper Hunter are categorised according to their level of interest and capacity to influence the issue of air quality. Figure 2 presents these relationships, dividing stakeholders into four groups: crowd (low interest and low power to influence), subjects (high interest but low power), key players (high interest and high power), and context setters (low interest but high power). The stakeholders are also coloured according to their primary mandate and sphere of influence, reflecting the colours in the applied four-tiered governance landscape and framework previously depicted in Figure 1. This four-tiered framework is as follows:

Figure 2.

Interest and stake and power and influence matrix.

- National scale (coloured grey) which includes Federal Government, Education and Academic Organisations, Media and Think Tanks, and WHS Organisations and Unions);

- State scale (coloured green) that includes State Government, Industry Associations, WHS Organisations, Education and Academia, and Media and Think Tanks;

- Industry scale (coloured orange) including Mining and Power Companies, Industry Associations, Logistics and Support Services, Contractors and Service Providers, and Unions and Business Representatives; and

- Local scale (coloured blue) that includes Local Government, Community Advisory Groups, Advocacy and Environmental Groups, Indigenous Groups and Traditional Landholders, Local Residents, and Education and Academic Organisations, and Media.

From this matrix it is obvious that overlaps are present across scales. For example, WHS organisations have a presence across federal and state scales (e.g., SafeWork Australia and SafeWork NSW), and unions operate on the federal, state, and industry scale (e.g., federal and operational union branches and industry presence). Similarly media operates across federal, state, and local scales (e.g., ABC, Newcastle Herald and Singleton Argus). Arguably, universities, academia, and research providers operate across all scales. Overall, such organisations (shown with multiple colours) straddle multiple tiers, thus producing both policy-level influence at national and state scales but also engagement with communities at the local and industry scale. Industry associations (e.g., NSW Minerals Council) provide a link between state regulation and local operations, whereas advocacy groups operate within community forums locally but are often aligned with NGOs, nationally and internationally evoking global environmental justice networks and movements that connect top-down and bottom-up dynamics.

A central actor in the Upper Hunter air quality landscape is the State Government, which holds authority to issue EPLs to mining and energy companies. Often overlooked are air quality consultancies, which provide technical assessments and advice on environmental impacts to a range of stakeholders. While classified under “Contractors, Service Providers,” their influence can rival that of advisory committees or industry associations, particularly in relation to approvals for new or extended developments, highlighting a gap in conventional stakeholder mapping. Air quality consultancies can also often be employed by all three scales of government, but also business, mining companies, industry associations and health organisations for analysis and reporting of air quality. As such, their analyses may at times reflect the priorities of the commissioning body, potentially affecting the perceived neutrality of reported findings.

Local residents are classified as subjects, directly exposed to emissions from mining and energy activities but with limited capacity to influence decisions. Stakeholder influence, however, can be amplified through collaboration and coalition building. For instance, the UHAQMN arose from collaboration between the State Government, mining companies, and energy producers. Similarly, partnerships between universities and industry, supported by federal government research programs such as the Australian Research Council (ARC), industry or WHS partnerships similar to those of the author, have the potential to integrate technical expertise into regulatory practice and catalyse improvements in air quality management, enhancing transparency and regional discourse. The neutrality of research findings may likewise be questioned, in ways similar to concerns raised about the objectivity of air quality consultancy outputs. On the other hand, the media plays a critical role in framing pertinent debates, yet reporting is often shaped by not only the influence of mining companies and government, but also the public’s propensity for topics and latest trends that can privilege economic narratives and downplay environmental and health concerns.

Historically, the Hunter’s identity has been shaped by close ties between the State Government and the resources sector, reinforced during the corporatisation and privatisation of state-owned power plants and coal mines in the 1990s and 2000s. Local governments, including Singleton and Muswellbrook councils, contribute substantially to state royalties, reflecting the embeddedness of state interests. These dynamics coincide with the “hollowing out” of state power [83] and the evolving influence of industry bodies such as the NSW Minerals Council [77], illustrating the concentration of control over land rights and resource development.

Horizontal governance tensions are particularly pronounced for Indigenous interests, as pre-emptive agreements and mining leases can restrict native title rights, with state indemnification reinforcing power asymmetries. Western legal frameworks such as Australia’s often prioritise individual property and economic interests over collective Indigenous stewardship [55], while historical dispossession has excluded Indigenous ecological knowledge from governance [56]. To increase equity for Indigenous people in economic, social, and environmental development [57], transformative change is needed nationally, at a scale similar to that for combating climate change globally. Unfortunately, the federal policies, legislation, and market mechanisms that continue to shape interactions among resource developers, government agencies, and Indigenous landholders, structuring rights, bargaining power, and decision-making [20], continue to reflect enduring colonial legacies in air quality governance.

Integrating environmental activism, justice considerations, native title, and legislative frameworks offers opportunities for structural reform. Alignment of these elements can enhance corporate social responsibility, reduce conflict, and foster a more transparent, accountable, and inclusive approach to air quality governance in the Upper Hunter, across the state and nationally.

Air quality governance in resource-dependent regions like the Upper Hunter is deeply shaped by historical and institutional dynamics. However, rather than viewing public health and environmental protection as inherently opposed to economic development, this perspective allows for a more nuanced understanding of how sustainable, inclusive development can be achieved. From this perspective, “win–win” outcomes, where economic activity supports livelihoods while minimising harm to health and the environment, are both possible and desirable. This is aided by more favourable weather conditions since the dry and heavy bushfire period of 2019–2020, with PM concentration levels paralleling those in other parts of the state [53]. Achieving these outcomes requires institutional arrangements that balance competing interests, enable genuine stakeholder participation, and build capacity for long-term planning. Examination of the institutions highlights that these arrangements must move beyond narrow, transactional governance to foster collaboration across sectors, while post-colonial and post-capitalist perspectives encourage rethinking dominant development paradigms to include Indigenous knowledge systems, care-based economies, and community-led innovation. In this light, sustainable development is not about sacrificing one goal for another, but about reconfiguring governance and decision-making so that environmental integrity, public health, and economic resilience are pursued together. This shift can help regions like the Upper Hunter move beyond extractive economic models, toward futures where ecological and social well-being are core to economic development strategies.

4. Conclusions

The issue of air quality in the Upper Hunter Valley, NSW, Australia, is significant and highly complex, shaped by intersecting environmental, social, economic, cultural, and political factors. Using a PEA framework, this study has mapped and analysed key stakeholders. These include state and federal governments, mining and energy companies, consultancies, advisory committees, residents, and educational institutions. The mapping and analysis shows that influence over outcomes emerges not solely from formal authority but through building coalitions, collaboration, and strategic engagement across public, private, and social sectors. Effective governance of this common-pool resource requires recognition of diverse actors, their interests, and the institutional arrangements that structure access, influence, and accountability [32]. These dynamics are embedded in colonial structures that historically privilege Western concepts of ownership, prioritising individual and corporate economic rights over collective stewardship and Indigenous land management [20,56].

Achieving meaningful improvements requires multi-disciplinary and multi-actor partnerships that bridge top-down governance with bottom-up engagement. Stakeholder analysis highlights how collaborations between universities, industry, and government integrate technical expertise into regulatory practice, while coalitions including Indigenous representatives and environmental organisations counter entrenched power asymmetries and promote equitable outcomes, exemplified by recent initiatives such as the Murujuga rock art monitoring program [84] in Western Australia (WA). Transparent communication of technological and regulatory decisions, grounded in scientific reasoning, enhances accountability and legitimacy [64]. However, technical solutions are also adopted in different ways by different actors from both industry and government. This is highlighted by the inclusion of the dustiness standard, AS4156.6, into an EPL in WA for the iron ore industry, despite it being specific to coal; meanwhile, it is not implemented in EPLs in NSW for coal mining operations [26].

Recent legal and policy developments underscore the urgency of these approaches. The NSW Court of Appeal’s decision to halt a major mine expansion for failing to account for full life-cycle emissions, including scope 3 impacts from exported coal [85], extends accountability from local scale to transnational climate effects, reinforcing the need to integrate climate considerations into governance. This parallels the calls of environmental advocacy groups. At the same time, the Upper Hunter illustrates how prioritising short-term economic benefits undermines social licence to operate, highlighting the fragility of acceptance when environmental risks are poorly managed [62,76]. Transition pathways that combine land restoration, renewable energy, and sustainable community development address environmental concerns while maintaining regional economic resilience [86].

More broadly, the Upper Hunter exemplifies contested management of public resources within a global, capital-centric economic system [21]. Embedding principles of equity, precaution, and sustainability into governance, reforming colonial legacies, and redefining ownership to recognise Indigenous rights and collective stewardship aligns with robust institutional design [32]. Institutional reform and multi-level, multi-actor partnerships that reconcile economic, environmental, and social objectives are essential for long-term air quality improvements. Lessons from the Upper Hunter offer guidance for national policy, supporting Australia’s transition from fossil fuel dependence toward a reduced carbon, climate resilient, and socially equitable future [20,56].

The outcomes of this PEA and stakeholder analysis provide recommendations that are grounded in a normative position that prioritises environmental justice, inter-generational equity, and the recognition of Indigenous rights within air quality governance. This perspective challenges dominant, growth-oriented policy frameworks that privilege economic efficiency and corporate interests over ecological sustainability and social well-being. The analysis draws from a political economy lens, informed by critical institutionalism, post-capitalism, and post-colonialism, which holds that enduring solutions to environmental problems such as air pollution require structural reforms that address historical inequalities, redistribute power, and enable meaningful participation by historically marginalised groups. From this perspective, technical and regulatory interventions are necessary but may also be deemed insufficient without parallel efforts to democratise decision-making and transform the institutional logic that underpins resource governance.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the support of industry and government partners in engineering projects on air quality and biomass, as well as the forums that facilitated open discussion and knowledge-sharing on air quality management in the Upper Hunter. This collaboration was essential in providing the situational awareness that informed the framing of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The acknowledged partners had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABC | Australian Broadcasting Corporation |

| ACARP | Australian Coal Association Research Program (ACARP) |

| ACPS | Australian Coal Preparation Society |

| AGL | Australian Gas Light |

| AS | Australian Standards |

| CCC | Community Consultative Committee |

| CFMEU | Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union |

| CSIRO | Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation |

| DCCEEW | Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water |

| DFID | Department for International Development |

| DPIE | Department of Primary Industries, Planning and Environment |

| EPA | Environment Protection Authority |

| IPC | Independent Planning Commission |

| LCS | Low-cost sensors |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| NGOs | Non-government Organisations |

| NSW | New South Wales |

| METS | Mining equipment and technology services |

| NEPC | National Environment Protection Council |

| NEPM | National Environment Protection Measure |

| PEA | Political economy analysis |

| PM | Particulate Matter |

| PHIC | Port Hedland Industries Council |

| RSL | Returned and Services League |

| TAFE | Technical and Further Education |

| SSD | State Significant Developments |

| UHAQMN | Upper Hunter Air Quality Monitoring Network |

| UHMD | Upper Hunter Mining Dialogue |

| WA | Western Australia |

| WHS | Work Health and Safety |

| WWF | World Wildlife Fund |

References

- Hunter Joint Organisation of Councils (HJOC). Upper Hunter Diversification Action Plan: Implementation Priorities; HJOC: Thornton, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McManus, P. Mines, Wines, and Thoroughbreds: Towards Regional Sustainability in the Upper Hunter, Australia. Reg. Stud. 2008, 42, 1275–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSW Mining. Our Economic Contribution. 2025. Available online: https://nswmining.com.au/mining-in-nsw/our-economic-contribution/ (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Mills, C. Strategic Review of Resources for Regions Program; University of Technology Sydney: Ultimo, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- NSW Government. Regional Growth Fund. 2024. Available online: https://www.nsw.gov.au/grants-and-funding/regional-growth-fund (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Cottle, D.; Keys, A. Open-cut coal mining in Australia’s Hunter valley: Sustainability and the Industry’s economic, ecological, and social implications. Int. J. Rural. Law Policy 2014, 1, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Climate and Health Alliance (CHA). Coal and Health in the Hunter: Lessons from one Valley for the World; Summary for Policymakers; CHA: Clifton Hill, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Hibberd, M.F.; Selleck, P.W.; Keywood, M.D.; Cohen, D.D.; Stelcer, E.; Atanacio, A.J. Upper Hunter Particle Characterisation Study; CSIRO: Campbell, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- NSW Government. Better Evidence, Stronger Networks, Healthy Communities, Five Year Review of the Upper Hunter Air Quality Monitoring Network. Report. 2017. Available online: https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/publications/better-evidence-stronger-networks-healthy-communities (accessed on 9 September 2025).[Green Version]

- NSW Government. Upper Hunter Air Quality Monitoring Network 5-Year Review 2022. Report. 2022. Available online: https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/publications/upper-hunter-air-quality-monitoring-network-5-year-review-2022 (accessed on 9 September 2025).[Green Version]

- Ferro, K.; Zeederberg, S. Upper Hunter Mining Dialogue Perceptions Study. Summ. Rep. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- McCarthy, J. The Independent Planning Commission is in Muswellbrook Today Considering a Mount Pleasant Coal Mine Application. Newcastle Herald. 2018. Available online: https://www.newcastleherald.com.au/story/5505849/muswellbrook-coal-mine-hearing-considers-serious-air-quality-concerns/ (accessed on 28 June 2024).[Green Version]

- Dalton, C.B.; Durrheim, D.N.; Marks, G.; Pope, C.A. Investigating the health impacts of particulates associated with coal mining in the Hunter Valley. Air Qual. Clim. Change 2014, 48, 39–43. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Hendryx, M.; Islam, M.S.; Dong, G.H.; Paul, G. Air Pollution Emissions 2008–2018 from Australian Coal Mining: Implications for Public and Occupational Health. Int. J. Environ. Resour. Public Health 2020, 17, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government. Orderly Exit Management Framework; Consultation Paper; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- NSW Government. Strategic Statement on Coal Exploration and Mining in NSW; NSW Government: Sydney, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- National Environment Protection Measure (NEPM). 2021. Available online: http://www.nepc.gov.au (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Australian Government. Available online: https://www.directory.gov.au/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- NSW Government. Available online: https://www.nsw.gov.au/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- O’Faircheallaigh, C. Aborigines, mining companies and the state in contemporary Australia: A new political economy or ‘business as usual’? Aust. J. Political Sci. 2006, 41, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.R. Transformation from “Carbon Valley” to a “Post-Carbon Society” in a climate change hot spot: The coalfields of the Hunter Valley, New South Wales, Australia. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshire, L.; Everingham, J.; Lawrence, G. Governing the impacts of mining and the impacts of mining governance: Challenges for rural and regional local governments in Australia. J. Rural. Stud. 2014, 36, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for International Development (DFID). How to Note: Political Economy Analysis; A DFID Practice Paper; DFID: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.; Graves, A.; Dandy, N.; Posthumus, H.; Hubacek, K.; Morris, J.; Prell, C.; Quinn, C.H.; Stringer, L.C. ‘Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management’. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1933–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilic, D. Update of Coal Dustiness and Dust Extinction Moisture (DEM) Standard AS4156.6. ACARP Project Number C33070. Final Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.acarp.com.au/abstracts.aspx?repId=C33070 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Ilic, D.; Lavrinec, A.; Sutton, L.; Holdsworth, J. Development and implementation of low-cost sensors and LiDAR for managing dust emissions due to mining activity. In Proceedings of the Iron Ore Conference 2023, Perth, Australia, 18–20 September 2023; Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Carlton, Australia, 2023; pp. 292–306. [Google Scholar]

- Ilic, D.; Lavrinec, A. Integration of Real-Time Low-Cost Particulate Matter Sensors into Coal Mining Air Quality Management to Identify Sources and Reduce Hazardous Exposure, Final Report. Coal Services Health and Safety Trust. 2024. Available online: https://www.coalservices.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Integration-of-real-time-low-cost-particulate-_20657-Final-Report_8_5_24.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Vanka, K.S. Characterizing the Effects of Mining Dust Particulate Matter Exposure on Respiratory Health. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vanka, K.S.; Shukla, S.; Gomez, H.M.; James, C.; Palanisami, T.; Williams, K.; Chambers, D.C.; Britton, W.J.; Ilic, D.; Hansbro, P.M.; et al. Understanding the pathogenesis of occupational coal and silica dust-associated lung disease. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022, 31, 210250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilic, D.; Williams, K.; Farnish, R.; Webb, E.; Liu, G. On the challenges facing the handling of solid biomass feedstocks. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2018, 12, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, D.; Leftwich, A. From Political Economy to Political Analysis; Developmental Leadership Program; Research Paper 25; University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Worker, J.; Palmer, N. A Guide to Assessing the Political Economy of Domestic Climate Change Governance; Working Paper; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denney, L. Using Political Economy Analysis in Conflict, Security and Justice Programmes; Toolkit; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Samji, S.; Andrews, M.; Pritchett, L.; Woolcock, M. PDIA toolkit. In A DIY Approach to Solving Complex Problems; Harvard Kennedy School: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT). Political Economy Analysis and Adaptive Management; Good practice note; DFAT: Barton, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- De Lopez, T.T. Stakeholder management for conservation projects: A case study of Ream National Park, Cambodia. Environ. Manag. 2001, 28, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eden, C.; Ackermann, F. Making Strategy: The Journey of Strategic Management; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.G.; Bruyneel, S. Rescaling environmental governance, rethinking the state: A three-dimensional review. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2010, 34, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owonikoko, A. Characterisation of Biomass Feedstocks Relaxation Properties Using Visco-Elastic Models. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ilic, D. Revised Dustiness and DEM Test Method (Update of AS4156.6) Part 2:Preparation. ACARP Project Number C26007. Final Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.acarp.com.au/abstracts.aspx?repId=C26007 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Parliamentary Education Office (PEO). Three Levels of Government: Governing Australia. 2025. Available online: https://peo.gov.au/understand-our-parliament/how-parliament-works/three-levels-of-government/three-levels-of-government-governing-australia (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Dobbie, B.; Green, D. Australians are not equally protected from industrial air pollution. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 055001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA). Pollution Reduction Programs. Operating Procedure. Environment Protection Authority, Sydney, Australia 2014. Available online: https://www.epa.nsw.gov.au/Publications/Licensing/140733-pollution-programs (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- NSW Environmental Protection Authority (EPA). NSW Coal Mining Benchmarking Study. In Best-Practice Measures for Reducting Non-Road Diesel Exhaust Emission; NSW Environmental Protection Authority (EPA): Griffith, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Katestone Environmental. NSW Coal Mining Benchmarking Study: International Best Practice Measures to Prevent and/or Minimise Emissions of Particulate Matter from Coal Mining; Katestone Environmental: South Brisbane, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Katestone Environmental. Literature Review of Coal Train Dust Management Practices; Katestone Environmental: South Brisbane, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- AGL Greenhouse Gas Policy. Available online: https://www.agl.com.au/about-agl/who-we-are/our-company (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Newcastle Herald. Mount Arthur Coal Mine in Hunter Valley Fined $15,000 for Excessive Dust Emissions. 2019. Available online: https://www.newcastleherald.com.au/story/6298238/mine-fined-15000-for-failing-to-minimise-dust-blown-off-premises/ (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- NSW Government. Protection of the Environment Operations (PEO), General Regulation; NSW Government: Sydney, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- NSW Government. Protection of the Environment Operations (PEO) Act; NSW Government: Sydney, Australia, 1997; Volume 156. [Google Scholar]

- NSW Government. NSW Annual Air Quality Statement 2024: Air Quality Summary. 2024. Available online: https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/topics/air/nsw-air-quality-statements/annual-air-quality-statement-2024/air-quality-summary#exceedance-days (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Upper Hunter Mining Dialogue (UHMD). Upper Hunter Air Quality Monitoring Network Analysis Project—Annual Review for 2024. 2025. Available online: https://miningdialogue.com.au/news/2024-air-quality-update (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Colagiuri, R.; Morrice, E. Do coal-related health harms constitute a resource curse? A case study from Australia’s Hunter Valley. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2015, 2, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, V.; France-Hudson, B. Implications of Climate Change for Western Concepts of Ownership: Australian Case Study. UNSW Law J. 2019, 42, 869–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layden, T.J.; David-Chavez, D.M.; Galofré García, E.; Gifford, G.L.; Lavoie, A.; Weingarten, E.R.; Bombaci, S.P. Confronting colonial history: Toward healing, just, and equitable Indigenous conservation futures. Ecol. Soc. 2025, 30, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First Nations Portfolio. Marramarra Murru (Creating Pathways). In First Nations Economic Development Symposium; Background Paper; Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Justice Australia. Clearing the Air, Why Australia Urgently Needs Effective National Air Pollution Laws; Environmental Justice Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Higginbotham, N.; Freeman, S.; Connor, L.; Albrecht, G. Environmental injustice and air pollution in coal affected communities, Hunter Valley, Australia. Health Place 2010, 16, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, L.; Freeman, S.; Higginbotham, N. Not Just a Coalmine: Shifting Grounds of Community Opposition to Coal Mining in Southeastern Australia. Ethnos 2009, 74, 490–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doctors for the Environment Australia, Fossil Fuels Are a Health Hazard. Report. 2024. Available online: https://www.dea.org.au/fossil_fuels_are_a_health_hazard_report (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Laurence, D. The devolution of the social licence to operate in the Australian mining industry. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 100742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, L. Experimental Publics: Activist Culture and Political Intelligibility of Climate Change Action in the Hunter Valley, Southeast Australia. Oceania 2012, 82, 228–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arranz, A.M.; Askland, H.H.; Box, Y.; Scurr, I. United in criticism: The discursive politics and coalitions of Australian energy debates on social media. Energy Res. Social Sci. 2024, 108, 102591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosberg, D. Theorising environmental justice: The expanding sphere of a discourse. Environ. Politics 2021, 22, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, L.; Adams, M.; McGregor, H.; Toole, S. Climate change and Australia. WIREs Clim. Change 2014, 5, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenhagen, J.H.; Cox, S. How do politics, news media and the public frame the discourse on coal mining? Implications for the legitimacy, (de)stabilisation and transition of an industry regime. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 218, 124217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, C. Climate Change and Future Justice: Precaution, Compensation and Triage, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, D.; Hobbs, M. Fighting for Coal: Public Relations and the Campaigns Against Lower Carbon Pollution Policies in Australia. In Carbon Capitalism and Communication, Palgrave Studies in Media and Environmental Communication; Brevini, B., Murdock, G., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, D.; Griffiths, K. Who’s in the Room? Access and Influence in Australian Politics. Working Paper. Grattan Institute. 2018. Available online: https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/908-Who-s-in-the-room-Access-and-influence-in-Australian-politics.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- O’Faircheallaigh, C. Resource development and inequality in indigenous societies. World Dev. 1998, 26, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoscience Australia. Australia’s Identified Mineral Resources 2023. 2024. Available online: https://www.ga.gov.au/aimr2023/summary-of-reserve-and-resource-life (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Geoscience Australia. Australia’s Energy Commodity Resources 2024, Gas. Available online: https://www.ga.gov.au/aecr2024/gas (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Campbell, R. Seeing Through the Dust: Coal in the Hunter Valley Economy; Policy Brief No. 62; The Australia Institute: Canberra, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- NSW Minerals Council. NSW Mining Industry Expenditure Impact Survey 2022/23; Lawrence Consulting: Sydney, Australia, 2023; Available online: https://nswmining.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/NSW-Mining-Industry-Expenditure-Impact-Survey-2022-23-Final.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Cattonar, L.; Suh, J.; Nursey-Bray, M. Coal dust pollution in regional Australian coal mining towns: Social License to Operate and community resistance. Geoforum 2024, 151, 104008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulby, H. Undermining Our Democracy: Foreign Corporate Influence Through the Australian Mining Lobby; Discussion Paper; The Australia Institute: Canberra, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Knaus, C. Christopher Pyne and the Revolving Door of MPs Turned Lobbyists. The Guardian. 2019. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/jun/28/christopher-pyne-and-the-revolving-door-of-mps-turned-lobbyists (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Lock the Gate Alliance. FREE-LOADERS. Air and Water Pollution from NSW Coal Mines. Analysis Paper. 2016. Available online: https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/lockthegate/pages/2754/attachments/original/1458616247/LTG_Load_Based_Licensing_Report.pdf?1458616247 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- NSW Environmental Protection Authority (EPA), Hunter Mines on Notice to Bust the Dust. 2025. Available online: https://www.epa.nsw.gov.au/news/epamedia/250901-hunter-mines-on-notice-to-bust-the-dust (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Wood, D.; Chan, I.; Coates, B. Inflation and Inequality: How High Inflation Is Affecting Different Australian Households. Working Paper. Grattan Institute. 2025. Available online: https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/confs/2023/pdf/rba-conference-2023-wood-chan-coates.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Coates, B.; Moloney, J.; Bowes, M. Housing Is Less Affordable Than Ever. 2025. Available online: https://grattan.edu.au/news/housing-is-less-affordable-than-ever/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Catney, P.; Doyle, T. Challenges to the State, Understanding the Environmental and Social Policy; Fitzpatrick, T., Ed.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of Western Australia, Legislative Council Publication Details, Murujuga Rock Art-Monitoring Program, Tuesday 27 May 2025. 2024. Available online: https://www.parliament.wa.gov.au/hansard/daily/uh/2025-05-27/21 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Yeandle, C. Mount Pleasant Coal Mine Expansion Halted After Community Legal Challenge. ABC News. 2025. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-07-24/mount-pleasant-coal-mine-expansion-halted-by-court/105566836 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Crofts, K.; Phelan, L. ‘We Need to Restore the Land’: As Coal Mines Close, Here’s a Community Blueprint to Sustain the Hunter Valley. 2023. Available online: https://theconversation.com/we-need-to-restore-the-land-as-coal-mines-close-heres-a-community-blueprint-to-sustain-the-hunter-valley-198792 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).