Orthorexia Nervosa and Its Associations with Novel Foods and Body Image Concerns

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Orthorexia and Food: Relationships with Traditional and Novel Foods

1.2. Orthorexia and Body: Relationships with Body Image Facets

1.3. Aims of the Study and Hypotheses Development

1.3.1. Hypotheses on the Association Between ON and Food Attitudes

1.3.2. Hypotheses on the Association Between ON and Body Image

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of the Study

4.2. Potential Impact and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Total Sample N = 306 | Cis. Women N = 209 | Cis. Men N = 86 | Comparison by Sex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (s.d) | M (s.d) | M (s.d) | t/U | d | |

| ONI impairments ✤ | 14.00 [8.00] | 14.00 [8.00] | 15.00 [9.00] | 9676 | 0.08 |

| ONI behavior | 17.98 (6.77) | 17.24 (6.38) | 19.57 (7.46) | 2.53 * | 0.34 |

| ONI emotions | 9.26 (4.57) | 8.87 (4.46) | 10.17 (4.78) | 2.18 * | 0.28 |

| ORTO-R | 15.22 (4.71) | 14.93 (4.61) | 15.58 (4.81) | 1.07 | 0.14 |

| FNSR | 16.17 (5.02) | 16.19 (8.12) | 15.87 (4.73) | −0.51 | −0.06 |

| BSQ | 41.10 (18.34) | 43.59 (18.53) | 35.84 (16.86) | −3.49 *** | −0.44 |

| DMS attitudes ° | 18.02 (9.17) | 16.24 (8.12) | 22.35 (10.06) | 3.82 *** | 0.67 |

| DMS supplement °✤ | 7.00 [5.00] | 6.00 [4.00] | 9.50 [9.00] | 4329 *** | 0.52 |

| DMS ITEM10: anabolic °✤ | 1.00 [0.00] | 1.00 [0.00] | 1.00 [2.00] | 3680 *** | 0.30 |

| DMS training adherence ° | 11.31 (6.10) | 10.09 (5.62) | 13.81 (6.30) | 3.62 *** | 0.62 |

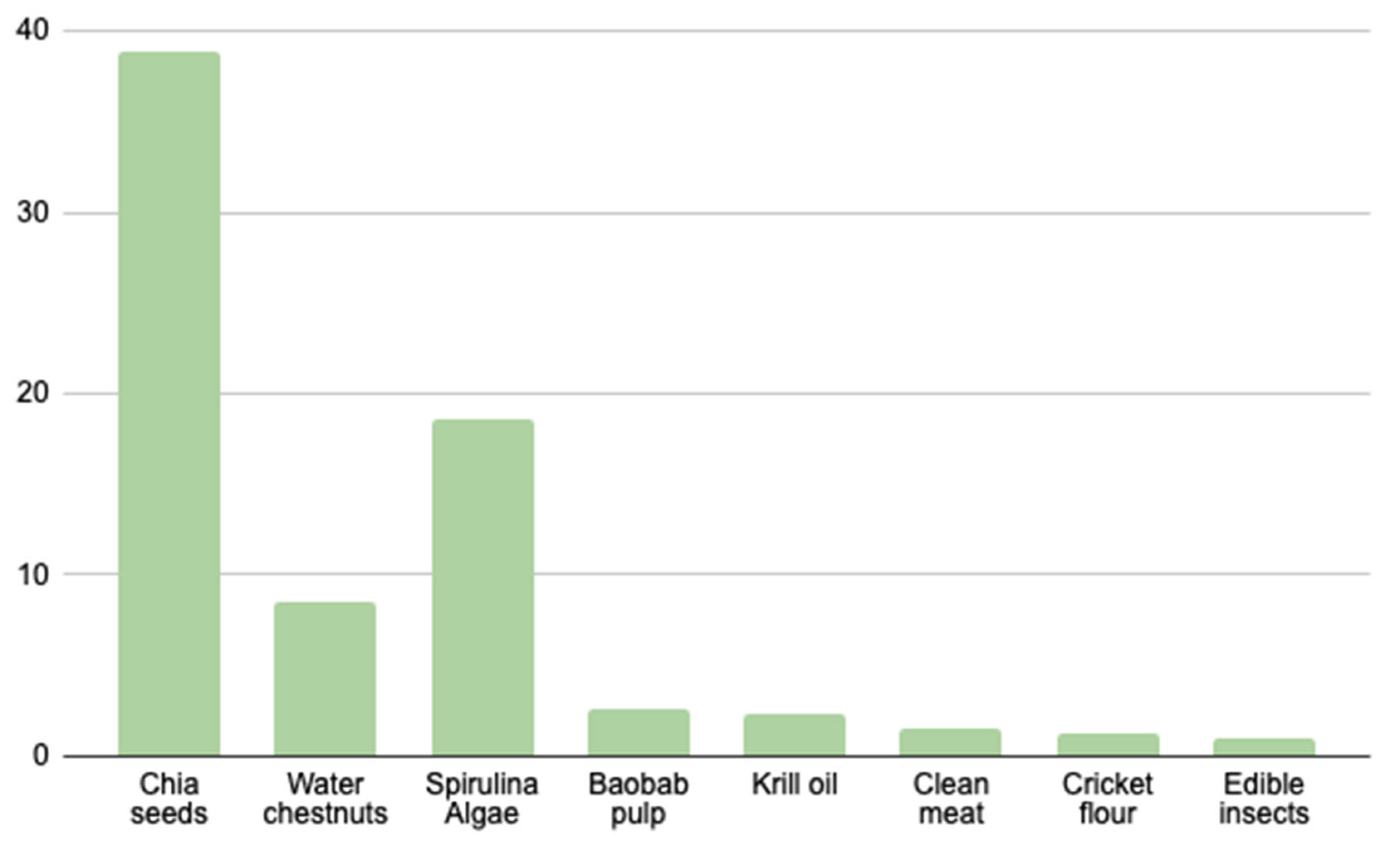

| Chia seeds: PA | 2.74 (1.16) | 2.87 (1.14) | 2.52 (1.19) | −2.28 * | −0.29 |

| Chia seeds: I | 2.97 (1.23) | 3.11 (1.18) | 2.81 (1.31) | −1.79 | −0.23 |

| Water chestnut: PA | 2.32 (1.05) | 2.35 (1.09) | 2.33 (0.99) | −0.18 | −0.02 |

| Water chestnut: I | 2.44 (1.10) | 2.49 (1.13) | 2.44 (1.02) | −0.34 | −0.04 |

| Spirulina algae: PA | 2.55 (1.29) | 2.66 (1.29) | 2.38 (1.24) | −1.72 | −0.22 |

| Spirulina algae: I | 2.60 (1.28) | 2.71 (1.27) | 2.43 (1.27) | −1.71 | −0.22 |

| Baobab pulp: PA | 1.89 (0.94) | 1.89 (0.94) | 1.97 (0.95) | 0.62 | 0.08 |

| Baobab pulp: I | 2.01 (1.04) | 2.00 (1.02) | 2.12 (1.11) | 0.87 | 0.11 |

| Krill oil: PA | 1.77 (0.93) | 1.73 (0.87) | 1.97 (1.07) | 1.83 | 0.24 |

| Krill oil: I | 1.88 (1.00) | 1.82 (0.93) | 2.10 (1.14) | 2.07 * | 0.28 |

| Clean meat: PA | 1.88 (1.10) | 1.86 (1.09) | 1.99 (1.15) | 0.91 | 0.12 |

| Clean meat: I | 1.98 (1.15) | 1.92 (1.12) | 2.20 (1.24) | 1.80 | 0.24 |

| Cricket flour: PA ✤ | 1.00 [1.00] | 1.00 [1.00] | 1.00 [2.00] | 10,644 ** | 0.18 |

| Cricket flour: I ✤ | 1.00 [1.00] | 1.00 [1.00] | 1.00 [2.00] | 10,740 *** | 0.20 |

| Edible insects: PA ✤ | 1.00 [0.00] | 1.00 [0.00] | 1.00 [2.00] | 10,498 *** | 0.17 |

| Edible insects: I ✤ | 1.00 [1.00] | 1.00 [0.00] | 1.00 [1.00] | 10,900 *** | 0.21 |

References

- Abdulwaliyu, I., Arekemase, S. O., Batari, M. L., Oshodin, J. O., Mustapha, R. A., Ibrahim, D., Ekere, A. T., & Olusina, O. S. (2024). Nutritional and pharmacological attributes of baobab fruit pulp. Food Production, Processing and Nutrition, 6(1), 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Toalá, J. E., Cruz-Monterrosa, R. G., & Liceaga, A. M. (2022). Beyond human nutrition of edible insects: Health benefits and safety aspects. Insects, 13(11), 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, C., Vieira Borba, V., & Santos, L. (2018). Orthorexia nervosa in a sample of Portuguese fitness participants. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 23, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almoraie, N. M., Alothmani, N. M., Alomari, W. D., & Al-Amoudi, A. H. (2025). Addressing nutritional issues and eating behaviours among university students: A narrative review. Nutrition Research Reviews, 38, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., DSM-5). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Babicz-Zielińska, E. (2006). Role of psychological factors in food choice—A review. Polish Journal of Food and Nutrition Sciences, 15(56), 379–384. [Google Scholar]

- Barrada, J. R., & Roncero, M. (2018). Bidimensional structure of the orthorexia: Development and initial validation of a new instrument. Anales de Psicología, 34(2), 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthels, F., Barrada, J. R., & Roncero, M. (2019). Orthorexia nervosa and healthy orthorexia as new eating styles. PLoS ONE, 14(7), e0219609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaran, A. G., & Ozbek, Y. D. (2023). A study of the relationship between university students’ food neophobia and their tendencies towards orthorexia nervosa. Behavioral Sciences, 13(12), 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X., Liang, Q., Jiang, G., Deng, M., Cui, H., & Ma, Y. (2024). The cost of the perfect body: Influence mechanism of internalization of media appearance ideals on eating disorder tendencies in adolescents. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutin, C., Maïano, C., & Aimé, A. (2024). Relation between orthorexia nervosa and healthy orthorexia: A latent profile analysis. Appetite, 194, 107165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bóna, E., Túry, F., & Forgács, A. (2019). Evolutionary aspects of a new eating disorder: Orthorexia nervosa in the 21st century. Psychological Thought, 12(2), 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracale, R., & Vaccaro, C. M. (2020). Changes in food choice following restrictive measures due to COVID-19. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases, 30(9), 1423–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, S. (1997). Health food junkie. Yoga Journal, 136, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Brytek-Matera, A., Gramaglia, C., Gambaro, E., Delicato, C., & Zeppegno, P. (2018). The psychopathology of body image in orthorexia nervosa. Journal of Psychopathology, 24, 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Brytek-Matera, A., Pardini, S., Modrzejewska, J., Modrzejewska, A., Szymańska, P., Czepczor-Bernat, K., & Novara, C. (2022). Orthorexia Nervosa and its association with obsessive–compulsive disorder symptoms: Initial cross-cultural comparison between Polish and Italian university students. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 27(3), 913–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brytek-Matera, A., Sacre, H., Staniszewska, A., & Hallit, S. (2020). The prevalence of orthorexia nervosa in polish and lebanese adults and its relationship with sociodemographic variables and bmi ranges: A cross-cultural perspective. Nutrients, 12(12), 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, F. C., Al-Ansari, S. S., Biddle, S., Borodulin, K., Buman, M. P., Cardon, G., Carty, C., Chaput, J.-P., Chastin, S., Chou, R., Dempsey, P. C., DiPietro, L., Ekelund, U., Firth, J., Friedenreich, C. M., Garcia, L., Gichu, M., Jago, R., Katzmarzyk, P. T., … Willumsen, J. F. (2020). World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(24), 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cena, H., Barthels, F., Cuzzolaro, M., Bratman, S., Brytek-Matera, A., Dunn, T., Varga, M., Missbach, B., & Donini, L. M. (2019). Definition and diagnostic criteria for orthorexia nervosa: A narrative review of the literature. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 24, 209–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerea, S., Bottesi, G., Pacelli, Q. F., Paoli, A., & Ghisi, M. (2018). Muscle dysmorphia and its associated psychological features in three groups of recreational athletes. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 8877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobzeanu, A., Roman, I. C., & Roca, I. C. (2025). When eating healthy becomes unhealthy: A cross-cultural comparison of the indirect effect of perfectionism on orthorexia nervosa through obsessive–compulsive symptoms. Psychiatry International, 6(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, P. J., Taylor, M. J., Cooper, Z., & Fairbum, C. G. (1987). The development and validation of the Body Shape Questionnaire. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 6(4), 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dega, V., & Barbhai, M. D. (2023). Exploring the underutilized novel foods and starches for formulation of low glycemic therapeutic foods: A review. Frontiers in Nutrition, 10, 1162462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depa, J., Barrada, J. R., & Roncero, M. (2019). Are the motives for food choices different in orthorexia nervosa and healthy orthorexia? Nutrients, 11(3), 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donini, L. M., Marsili, D., Graziani, M. P., Imbriale, M., & Cannella, C. (2004). Orthorexia nervosa: A preliminary study with a proposal for diagnosis and an attempt to measure the dimension of the phenomenon. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 9, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donini, L. M., Marsili, D., Graziani, M. P., Imbriale, M., & Cannella, C. (2005). Orthorexia nervosa: Validation of a diagnosis questionnaire. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 10, e28–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dönmez, A. (2024). Orthorexia Nervosa and Perfectionism: A Systematic Review. Psikiyatride Güncel Yaklaşımlar, 16(4), 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duradoni, M., Baroni, M., Fiorenza, M., Bellotti, M., Neri, G., & Guazzini, A. (2025). Readiness to change and the intention to consume novel foods: Evidence from linear discriminant analysis. Sustainability, 17(11), 4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duradoni, M., Gursesli, M. C., Fiorenza, M., & Guazzini, A. (2023). The relationship between orthorexia nervosa and obsessive compulsive disorder. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(5), 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftimov, T., Popovski, G., Petković, M., Seljak, B. K., & Kocev, D. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic changes the food consumption patterns. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 104, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escoto, C., Alvarez-Rayón, G., Mancilla-Díaz, J. M., Camacho Ruiz, E. J., Franco Paredes, K., & Juárez Lugo, C. S. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Drive for Muscularity Scale in Mexican males. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 18, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2023). Novel food. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/safety/novel-food_en (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadit, A. A. (2003). Ethnopsychiatry—A review. Journal-Pakistan Medical Association, 53(10), 483–490. [Google Scholar]

- Gortat, M., Samardakiewicz, M., & Perzyński, A. (2021). Orthorexia nervosa-a distorted approach to healthy eating. Psychiatria Polska, 55(2), 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grajek, M., Krupa-Kotara, K., Słoma-Krześlak, M., & Sas-Nowosielski, K. (2022). Analysis of eating behavior of health science students in terms of emotional eating and restrained eating. Journal of Education, Health and Sport, 12(12), 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramaglia, C., Gambaro, E., Delicato, C., Marchetti, M., Sarchiapone, M., Ferrante, D., Roncero, M., Perpiñá, C., Brytek-Matera, A., Wojtyna, E., & Zeppegno, P. (2019). Orthorexia nervosa, eating patterns and personality traits: A cross-cultural comparison of Italian, Polish and Spanish university students. BMC Psychiatry, 19, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, M., Carraro, L., Cavazza, N., & Roccato, M. (2018). Validation of the revised Food Neophobia Scale (FNS-R) in the Italian context. Appetite, 128, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanganu-Bresch, C. (2019). Orthorexia: Eating right in the context of healthism. Medical Humanities, 46, 311–322. [Google Scholar]

- Hebbar, U., Ranjan, S., Dasgupta, N., & Mishra, R. K. (Eds.). (2020). Nano-food engineering. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- IBM. (2025). Software IBM SPSS. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/it-it/spss (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- Indelicato, S., Lino, C., Bongiorno, D., Orecchio, S., D’Agostino, F., Indelicato, S., Todaro, A., Parafati, L., & Avellone, G. (2025). Cricket flour for a sustainable pasta: Increasing the nutritional profile with a safe supplement. Foods, 14(14), 2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalender, G. İ. (2020, March 20). The portrayal of ideal beauty both in the media and in the fashion industry and how these together lead to harmful consequences such as eating disorders. 10th Conference on Humanities, Psychology and Social Sciences, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss-Leizer, M., & Rigó, A. (2019). People behind unhealthy obsession to healthy food: The personality profile of tendency to orthorexia nervosa. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 24(1), 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıçaslan, A. K. (2025). Orthorexia in obsessive–compulsive personality disorder: The impact of perfectionism and metacognition. BMC Psychiatry, 25(1), 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyu, E. B., Karaağaç, Y., & Öner, B. N. (2024). The association between food neophobia, bi-dimensional aspects of orthorexia, and anxiety among vegetarians and omnivores. Appetite, 197, 107303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. M., Majeed, N. M., & Sharma, D. K. (2024). An updated review on water chestnut. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 13(13), 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kuş, Y., Tan, E., Doğan, O., & Bas, A. (2025). From likes to obsessions: The mediating role of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in the relationship between social media addiction and orthorexia nervosa. Turkish Journal Clinical Psychiatry, 28(1), 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakew, H., Bahta, Y., Ogundeji, A., & Sebastian, Y. (2025). Impacts of climate change and population pressure on food consumption patterns and economic consequence: A comparative analysis of urban and rural areas in Sub-Saharan Africa. Africa Review, 1, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, M. B., Hinze, C. J., Emborg, B., Thomsen, F., & Hemmingsen, S. D. (2017). Compulsive exercise: Links, risks and challenges faced. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 10, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardon, J., Tylka, T. L., & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. (2021). Intuitive eating and its psychological correlates: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 54(7), 1073–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łucka, I., Janikowska-Hołoweńko, D., Domarecki, P., Plenikowska-Ślusarz, T., & Domarecka, M. (2019). Orthorexia nervosa-a separate clinical entity, a part of eating disorder spectrum or another manifestation of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatria Polska, 53(2), 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPhail, D. C., & Oberle, C. D. (2022). Seeing Shred: Differences in muscle dysmorphia, orthorexia nervosa, depression, and obsessive-compulsive tendencies among groups of weightlifting athletes. Performance Enhancement & Health, 10(1), 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzola, E., Martini, M., Longo, P., Toppino, F., Bevione, F., Delsedime, N., Abbate-Daga, G., & Preti, A. (2022). Psychometric properties of the Italian body shape questionnaire: An investigation of its reliability, factorial, concurrent, and criterion validity. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 27(8), 3637–3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazac, R., Meinilä, J., Korkalo, L., Järviö, N., Jalava, M., & Tuomisto, H. L. (2022). Incorporation of novel foods in European diets can reduce global warming potential, water use and land use by over 80%. Nature Food, 3(4), 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCreary, D. R., Sasse, D. K., Saucier, D. M., & Dorsch, K. D. (2004). Measuring the drive for muscularity: Factorial validity of the drive for muscularity scale in men and women. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 5(1), 49. [Google Scholar]

- Messer, M., Liu, C., McClure, Z., Mond, J., Tiffin, C., & Linardon, J. (2022). Negative body image components as risk factors for orthorexia nervosa: Prospective findings. Appetite, 178, 106280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monaco, A., König, L. M., Kotz, J., Allmeta, A., & Al Masri, M. (2023). Consumers perception of novel foods and the impact of heuristics and biases: A systematic review. Appetite, 196, 107285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, P. (2015). Satisfaction, satiation and food behaviour. Current Opinion in Food Science, 3, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Q. X., Lee, D. Y. X., Yau, C. E., Han, M. X., Liew, J. J. L., Teoh, S. E., Ong, C., Yaow, C. Y. L., & Chee, K. T. (2024). On orthorexia nervosa: A systematic review of reviews. Psychopathology, 57(4), 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolosi, G. (2006). Biotechnologies, alimentary fears and the orthorexic society. Tailoring Biotechnologies, 2(3), 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Oberle, C. D., De Nadai, A. S., & Madrid, A. L. (2021). Orthorexia Nervosa Inventory (ONI): Development and validation of a new measure of orthorexic symptomatology. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 26, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osowiecka, K., & Myszkowska-Ryciak, J. (2020). Attitudes towards ‘superfood’ depending on the risk of orthorexia among students in Poland and The Netherlands. General Medicine & Health Sciences/Medycyna Ogólna i Nauki o Zdrowiu, 26(4), 378. [Google Scholar]

- Pauzé, A., Plouffe-Demers, M. P., Fiset, D., Saint-Amour, D., Cyr, C., & Blais, C. (2021). The relationship between orthorexia nervosa symptomatology and body image attitudes and distortion. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 13311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piochi, M., Franceschini, C., Fassio, F., & Torri, L. (2025). A large-scale investigation of eating behaviors and meal perceptions in Italian primary school cafeterias: The relationship between emotions, meal perception, and food waste. Food Quality and Preference, 123, 105333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plichta, M., Jezewska-Zychowicz, M., & Gębski, J. (2019). Orthorexic tendency in Polish students: Exploring association with dietary patterns, body satisfaction and weight. Nutrients, 11(1), 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pliner, P., & Hobden, K. (1992). Development of a scale to measure the trait of food neophobia in humans. Appetite, 19(2), 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontillo, M., Zanna, V., Demaria, F., Averna, R., Di Vincenzo, C., De Biase, M., Di Luzio, M., Foti, B., Tata, M. C., & Vicari, S. (2022). Orthorexia nervosa, eating disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorder: A selective review of the last seven years. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(20), 6134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raffone, F., Atripaldi, D., Barone, E., Marone, L., Carfagno, M., Mancini, F., Saliani, A. M., & Martiadis, V. (2025). Exploring the role of guilt in eating disorders: A pilot study. Clinics and Practice, 15(3), 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoza, R., & Donini, L. M. (2021). Introducing ORTO-R: A revision of ORTO-15: Based on the re-assessment of original data. Eating and Weight Disorders, 26(3), 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaffardi, L., & Formici, G. (2022). Novel foods and edible insects in the European Union: An interdisciplinary analysis (p. 169). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Scarff, J. R. (2017). Orthorexia nervosa: An obsession with healthy eating. Federal Practitioner, 34(6), 36. [Google Scholar]

- Sforza, S. (2022). Food (In)Security: The role of novel foods on sustainability. In Novel foods and edible insects in the European Union (pp. 59–79). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Shahidi, F., & Abad, A. (2024). Why is Antactic krill (Euphasia superba) oil on the spotlight? A review. Food Production, Processing and Nutrition, 6(1), 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahler, J., & Stark, R. (2020). Perspective: Classifying orthorexia nervosa as a new mental illness—Much discussion, little evidence. Advances in Nutrition, 11(4), 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, H., Memon, M. A., Thurasamy, R., & Cheah, J. H. (2025). Snowball sampling: A review and guidelines for survey research. Asian Journal of Business Research (AJBR), 15(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth-Király, I., Gajdos, P., Román, N., Vass, N., & Rigó, A. (2021). The associations between orthorexia nervosa and the sociocultural attitudes: The mediating role of basic psychological needs and health anxiety. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 26, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tragantzopoulou, P., & Giannouli, V. (2024). Unveiling anxiety factors in orthorexia nervosa: A qualitative exploration of fears and coping strategies. Healthcare, 12, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ucar, E. M., Sevim, S., & Kizil, M. (2018). Is there a link to food neophobia and orthorexia nervosa? Clinical Nutrition, 37, S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usta Ulutaş, P., & Okan Bakır, B. (2025). The type of social media is a greater influential factor for orthorexia nervosa than the duration: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 25(1), 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, M., Thege, B. K., Dukay-Szabó, S., Túry, F., & van Furth, E. F. (2014). When eating healthy is not healthy: Orthorexia nervosa and its measurement with the ORTO-15 in Hungary. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A. K., Dewangan, K., Daunday, L., Naurange, K., Verma, K., & Bhiaram, M. (2024). Spirulina as functional food: Insights into cultivation, production, and health benefits. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Research, 12(5), 28–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M., Berry, R., & Rodgers, R. F. (2020). Body image and body change behaviors associated with orthorexia symptoms in males. Body Image, 34, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, D. A., Martin, C. K., & Stewart, T. (2004). Psychological aspects of eating disorders. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology, 18(6), 1073–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagaria, A., Barbaranelli, C., Mocini, E., & Lombardo, C. (2023). Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Orthorexia Nervosa Inventory (ONI). Journal of Eating Disorders, 11(1), 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, T., Fournier-Level, A., Ebert, B., & Roessner, U. (2024). Chia (Salvia hispanica L.), a functional ‘superfood’: New insights into its botanical, genetic and nutraceutical characteristics. Annals of Botany, 134(5), 725–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | ONI Impairments ✤ | ONI Behavior | ONI Emotions | ORTO-R |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chia seeds: PA | 0.15 ** | 0.33 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.22 *** |

| Chia seeds: I | 0.19 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.22 *** |

| Water chestnut: PA | −0.06 | 0.13 * | 0.14 * | 0.14 * |

| Water chestnut: I | −0.03 | 0.11 * | 0.12 * | 0.13 * |

| Spirulina algae: PA | −0.08 | 0.13 * | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| Spirulina algae: I | −0.08 | 0.13 * | 0.08 | 0.12 * |

| Baobab pulp: PA | −0.02 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.11 * |

| Baobab pulp: I | 0.03 | 0.21 *** | 0.12 * | 0.19 *** |

| Krill oil: PA | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.03 |

| Krill oil: I | −0.01 | 0.12 * | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| Clean meat: PA | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.18 ** | 0.21 *** |

| Clean meat: I | 0.16 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.22 *** | 0.27 *** |

| Cricket flour: PA ✤ | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.14 * |

| Cricket flour: I ✤ | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.17 ** |

| Edible insects: PA ✤ | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.12 * |

| Edible insects: I ✤ | 0.04 | 0.14 * | 0.06 | 0.14 * |

| Variables | FNSR | BSQ | DMS Attitudes ° | DMS Supplement °✤ | DMS ITEM10: Anabolic °✤ | DMS Training Adherence ° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ONI impairments ✤ | 0.07 | 0.45 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.39 *** |

| ONI behavior | −0.04 | 0.26 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.49 *** |

| ONI emotions | −0.06 | 0.53 *** | 0.57 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.53 *** |

| ORTO-R | −0.07 | 0.60 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.45 *** |

| Variables | Age | Sex | FNSR | BSQ | DMS Attitudes ° | DMS ITEM10: Anabolic °॥ | DMS Training Adherence ° | R2 | F (7;160) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ONI impairments ✤ | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.35 *** | 0.13 | 0.32 *** | 0.12 | 0.43 | 18.55 (p < 0.001) |

| ONI behavior | 0.20 ** | −0.02 | −0.06 | 0.21 ** | 0.04 | 0.41 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.48 | 22.43 (p < 0.001) |

| ONI emotions | 0.04 | −0.07 | −0.04 | 0.45 *** | 0.14 | 0.27 *** | 0.12 | 0.53 | 26.88 (p < 0.001) |

| ORTO-R | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.55 *** | 0.08 | 0.25 *** | 0.10 | 0.57 | 28.56 (p < 0.001) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duradoni, M.; Colombini, G.; Gori, N.; Guazzini, A. Orthorexia Nervosa and Its Associations with Novel Foods and Body Image Concerns. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081138

Duradoni M, Colombini G, Gori N, Guazzini A. Orthorexia Nervosa and Its Associations with Novel Foods and Body Image Concerns. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081138

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuradoni, Mirko, Giulia Colombini, Noemi Gori, and Andrea Guazzini. 2025. "Orthorexia Nervosa and Its Associations with Novel Foods and Body Image Concerns" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081138

APA StyleDuradoni, M., Colombini, G., Gori, N., & Guazzini, A. (2025). Orthorexia Nervosa and Its Associations with Novel Foods and Body Image Concerns. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081138