The Impact of School Leadership on Inclusive Education Literacy: Examining the Sequential Mediation of Job Stress and Teacher Agency

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. School Leadership and Teacher Inclusive Education Literacy

2.2. Job Stress and Teacher Agency

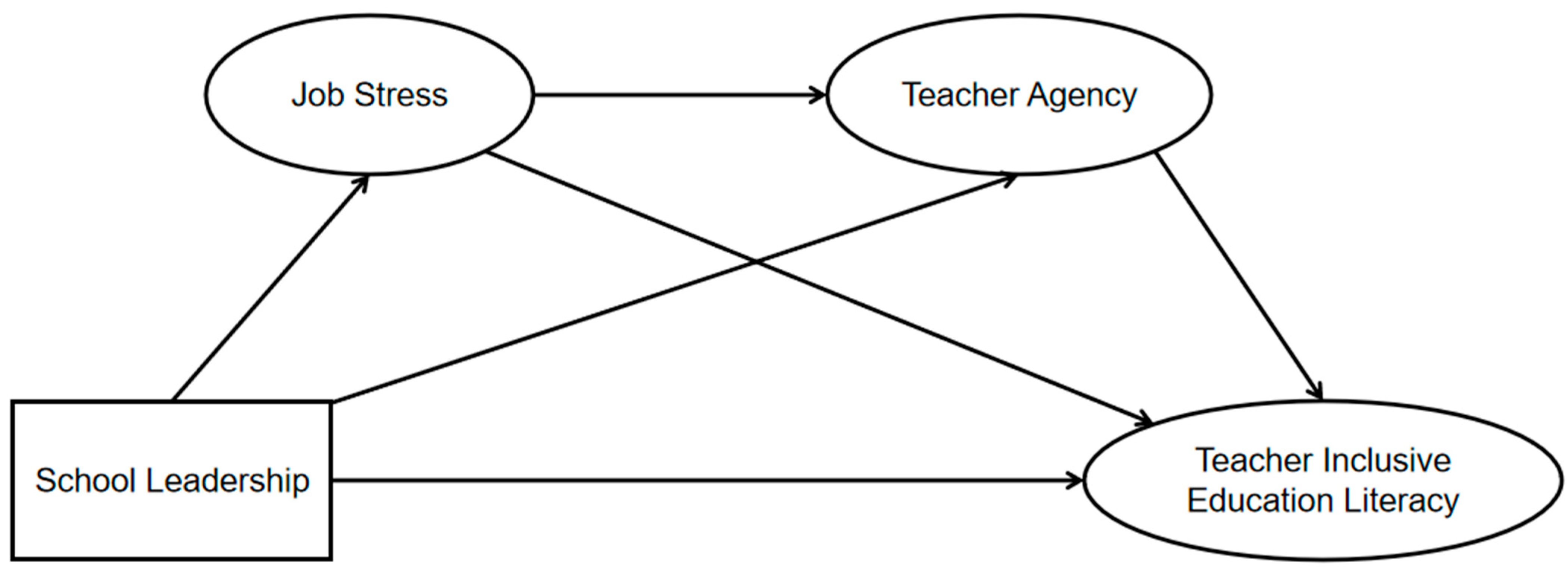

2.3. Research Hypotheses

3. Research Methods

3.1. Procedure

3.2. Data Collection and Processing

3.3. Measurement Tools

- (1)

- School Leadership

- (2)

- Teacher Inclusive Education Literacy

- (3)

- Job Stress

- (4)

- Teacher Agency

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

4.1.1. Common Method Bias Test

4.1.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

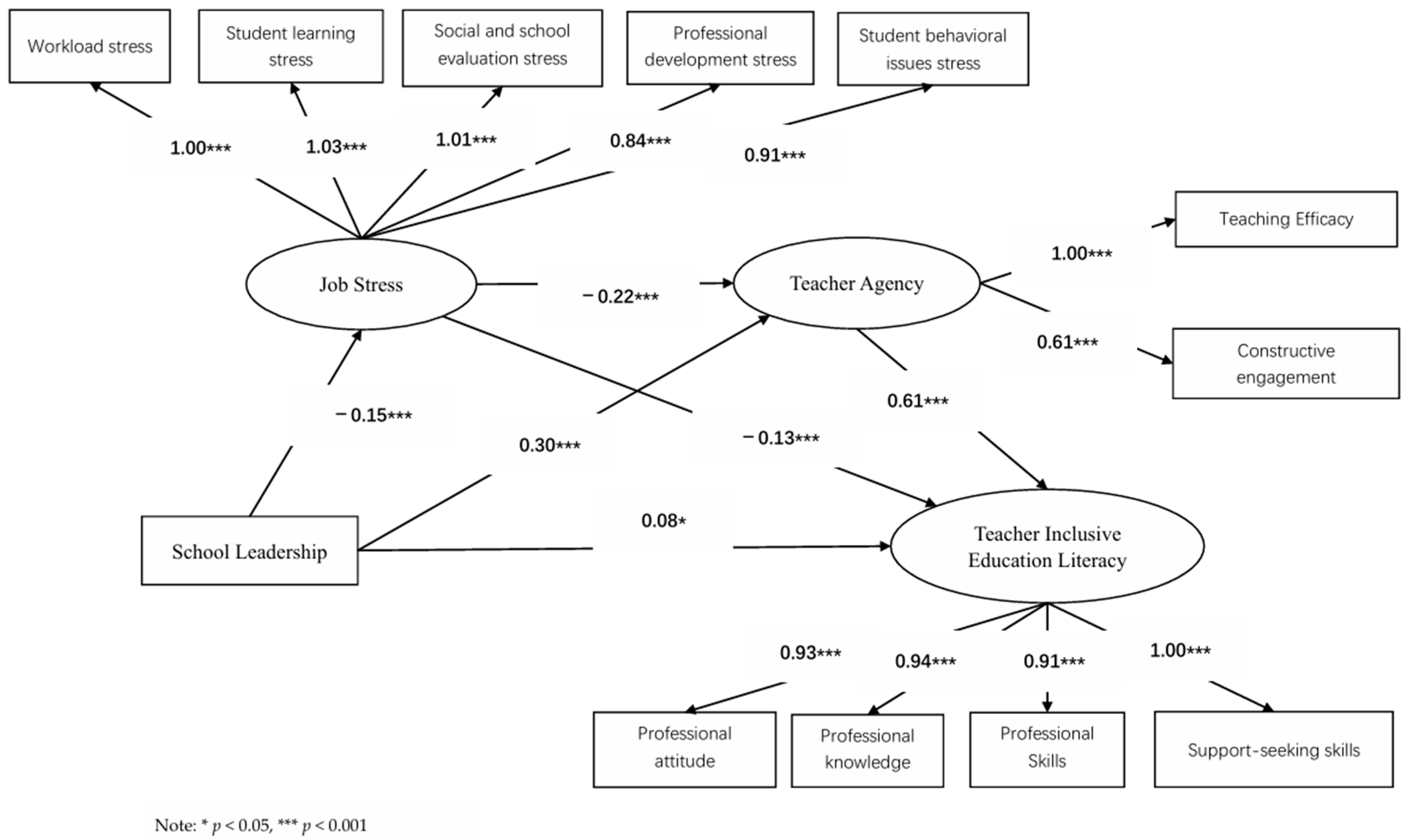

4.1.3. Testing and Comparison of the Chain Mediation Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Direct Effect of School Leadership on Inclusive Education Literacy

5.2. Mediating Role of Job Stress

5.3. Mediating Role of Teacher Agency

5.4. Chain Mediation Through Job Stress and Teacher Agency

6. Recommendations

6.1. Improving Leadership Styles to Provide Active Support

6.2. Reducing Job Stress for Teachers in Learning in Regular Classrooms

6.3. Fully Activating Teacher Agency

6.4. Coordinating Multiple Factors to Enhance Inclusive Education Literacy

7. Limitations and Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldrup, K., Klusmann, U., Lüdtke, O., Göllner, R., & Trautwein, U. (2018). Social support and classroom management are related to secondary students’ general school adjustment: A multilevel structural equation model using student and teacher ratings. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(8), 1066–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. (2023). Job demands-resources theory: Ten years later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellibaş, M. Ş., Gümüş, S., & Chen, J. (2023). The impact of distributed leadership on teacher commitment: The mediation role of teacher workload stress and teacher well-beingp. British Educational Research Journal, 50(2), 814–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. Harper&Row. [Google Scholar]

- CCSSO.STATE. (2018). STRATEGIES-CCSSO inclusive principals guide. Available online: https://ceedar.education.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/The-Role-of-Inclusive-Principal-Leadership.pdf#:~:text=The%20Council%20of%20Chief%20State%20School%20Officers%27,the%20potential%20and%20needs%20of%20each%20student (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., & Perry, N. E. (2012). School climate and social–emotional learning: Predicting teacher stress, job satisfaction, and teaching agency. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 1189–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y. (2014). On the core professionalism of teachers in inclusive classrooms. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 20(01), 4–9+23. [Google Scholar]

- Hallinger, P., Piyaman, P., & Viseshsiri, P. (2017). Assessing the effects of learning-centered leadership on teacher professional learning in Thailand. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. S., & Lee, W. K. (2024). The effects of job stress on South Korean teachers’ instructional practices: The mediating roles of teacher self-agency and job satisfaction. Kedi Journal of Educational Policy, 21(2), 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kuyini, A. B., Major, T. E., Mangope, B., & Alhassan, M. (2021). Botswana teachers: Competencies perceived as important for inclusive education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 28(7), 1224–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuyini, A. B., Yeboah, K. A., Das, A. K., Alhassan, A. M., & Mangope, B. (2016). Ghanaian teachers: Competencies perceived as important for inclusive education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(10), 1009–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, R., McCarthy, C., Weppner, C., Malerba, C., Osman, D., Holcomb, T. S., & Bottoms, B. L. (2024). Associations between teacher stress and school leadership: A mixed methods study with implications for school psychologists. School Psychology, 38(6), 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., & Zhang, S. (2024). Reform vision of international quality assessment indicators of inclusive education: An interpretation based on OECD report “indicators for inclusive education: A analytical framework”. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 29(08), 10–19+51. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L., & Ruppar, A. (2021). Conceptualizing teacher agency for inclusive education: A systematic and international review. Teacher Education and Special Education, 44(1), 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., Zhang, G. L., & Zhou, J. (2011). The study on sources of occupational stress of primary and secondary school teachers. Psychological Development and Education, 27(1), 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S., & Wang, Y. (2022). The effect of transformational leadership on the attitude to inclusive education of teachers teaching in the regular classroom: A moderated mediation model. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 27(09), 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Litt, M. D., & Turk, D. C. (1985). Sources of stress and dissatisfaction in experienced high schoolteacher. Journal of Educational Research, 78(3), 175–176. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M., & Xie, Y. (2025). Influencing factors and improvement strategies of principal curriculum leadership in promoting regular-special education integration—Based on case studies of four principals from inclusive education demonstration schools. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 30(04), 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S., & Hallinger, P. (2018). Principal instructional leadership, teacher self-agency, and teacher professional learning in China: Testing a mediated-effects model. Educational Administration Quarterly, 54(4), 501–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinek, D. (2019). The consequences of job-related pressure for self-determined teaching. Social Psychology of Education, 22, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendizábal, P. G. (2024). Teaching con Cariño: Teacher agency and teacher-student relationships in a dual language classroom. Journal of Latinos and Education, 24(1), 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. (2022). Notice of the ministry of education on issuing the “guidelines for evaluating the quality of special education”. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A06/s3331/202211/t20221107_975922.html (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Morocco, J. C., & McFadden, H. (1982). The counselor’s role in reducing teacher stress. The Personnel and Guidance Journal, 60(9), 549–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietsch, M., & Tulowitzki, P. (2017). Disentangling school leadership and its ties to instructional practices—An empirical comparison of various leadership styles. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 28(4), 629–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, M., Biesta, G., & Robinson, S. (2016). Teacher agency: An ecological approach. Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Y., Wang, X., & Wu, X. (2020). Teachers’ professional development initiative and its influencing factors: Based on the job characteristics. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 28(04), 779–782+778. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, C., & Wang, Y. (2024). Preliminary thoughts on the construction of competence model for Chinese school teachers in the new era. Education Science, 40(03), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, J. (2010). Impact of teacher efficacy on teacher attitudes toward classroom inclusion [Ph.D. thesis, Capella University]. [Google Scholar]

- Steiger, J. H. (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25(2), 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. G., Roberts, A. M., & Zarrett, N. (2021). A brief mindfulness-based intervention (bMBI) to reduce teacher stress and burnout. Teaching and Teacher Education, 100, 103284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Mo, L., & Niu, S. (2020). Research on the implementation of individualized educational plan in inclusive education schools—Based on an investigation in Haidian district, Beijing. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 7, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. (2017). Research on the impact of teachers’ self-awareness and school support atmosphere on teachers’ professional development. Educational Science Research, 30(11), 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T., & Tian, G. (2023). Linking distributed leadership with differentiated instruction in inclusive schools: The mediating roles of teacher leadership and professional literacy. Behavioral Science, 13, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. (2021). Research on inclusive education competence and improvement model of inclusive education teachers. Educational Science Research, 34(08), 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., Fan, W., Zhang, W., & Zhou, D. (2020). The effect of inclusive school climate on teachers’ inclusive education competence: The mediating role of teacher agency. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 25(08), 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., Wang, Z., & Feng, Y. (2015). Research on the current professional competence of teachers for inclusive education and its influencing factors. Teacher Education Research, 27(4), 46–52+60. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., & Yu, L. (2024). The construction and interpretation of teacher support system in the context of inclusive education—Based on the perspective of social ecosystem theory. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 29(09), 30–34+87. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. (2020). The impact of distributed leadership on university teachers’ organizational citizenship behavior: Mediated by attitudinal factors. Teacher Education Research, 32(01), 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, R., Chai, H., Zhu, D., Yao, L., Yan, W., & Fu, W. (2023). Analysis of the factors influencing inclusive education competency of primary and secondary physical education teachers in China. Sustainability, 15, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., & Zhou, D. (2025). Hotspots and trends analysis of teacher agency research based on knowledge graphs. Journal of Hangzhou Normal University (Natural Science Edition), 24(4), 439–448. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. (2022). On the pioneer thought contained in Bandura’s triadic reciprocality determinism. Psychological Research, 15(02), 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y., Su, M., Wang, D., Tian, H., & Peng, Y. (2024). The effects of school inclusive climate on teachers’ work engagement in inclusive education: The chain mediating role of job satisfaction and attitude toward inclusive education. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 29(08), 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X., & Chen, G. (2018). Monograph headmasters’ transboundary leadership: Connotations, functions and promotion strategies. Theory and Practice of Education, 38(26), 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D. (2019). Research on the structure of teacher agency and the mechanism of its relevant factors in inclusive education context [Ph.D. thesis, Beijing Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D., & Wang, Y. (2017). The composition of inclusive education teacher competence in the U.S. and its enlightenment on China. International and Comparative Education, 39(03), 89–95+100. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D., & Wang, Y. (2022). The effects of inclusive school climate on teachers’ job burnout: The mediating role of job stress and teacher agency. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 2022(7), 82–88+96. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | Total | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| School level | Primary | 680 | 90.5 |

| Junior high | 71 | 9.5 | |

| Gender | Male | 113 | 15 |

| Female | 638 | 85 | |

| Age | 21–30 years old | 215 | 28.6 |

| 31–40 years old | 334 | 44.5 | |

| 41–50 years old | 168 | 22.4 | |

| 51–60 years old | 34 | 4.5 | |

| Years of teaching | 0–2 years | 84 | 11.2 |

| 3–10 years | 255 | 34 | |

| 11–20 years | 412 | 54.9 | |

| Years as an inclusive teacher | 0–2 years | 323 | 43 |

| 3–10 years | 255 | 34 | |

| 11–20 years | 173 | 23 | |

| Variable Name | Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (SD) | Correlation Among Variables Teacher Proactivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher Inclusive Education Literacy | Job Stress | Teacher Agency | School Leadership | |||

| Teacher Inclusive Education Literacy | 3.799 | 0.596 | 1 | |||

| Job Stress | 3.484 | 0.722 | −0.212 ** | 1 | ||

| Teacher Agency | 3.449 | 0.718 | 0.546 ** | −0.284 ** | 1 | |

| School Leadership | 4.045 | 0.769 | 0.380 ** | −0.155 ** | 0.300 ** | 1 |

| Fitting Index | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMR | GFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | NFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculated Value | 396.072 | 49 | 8.083 | 0.028 | 0.916 | 0.932 | 0.908 | 0.931 | 0.923 | 0.097 |

| Judgment Criteria | ≤5 | ≤0.10 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≤0.10 |

| Effects | Path | Effect Value | Proportion of the Total Effect | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||||

| Direct Effects | Path 1: School Leadership → Teacher Inclusive Education Literacy | 0.084 | 26.17% | 0.014 | 0.154 |

| Indirect Effects | Path 2: School Leadership → Job Stress → Teacher Inclusive Education Literacy | 0.022 | 6.85% | 0.008 | 0.042 |

| Indirect Effects | Path 3: School Leadership → Teacher Agency → Teacher Inclusive Education Literacy | 0.193 | 60.13% | 0.135 | 0.255 |

| Indirect Effects | Path 4: School Leadership → Job stress → Teacher Agency → Teacher Inclusive Education Literacy | 0.022 | 6.85% | 0.011 | 0.037 |

| Total Effect Value | 0.284 | 100% | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, Y.; Zhou, D.; Wei, Y. The Impact of School Leadership on Inclusive Education Literacy: Examining the Sequential Mediation of Job Stress and Teacher Agency. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111572

Feng Y, Zhou D, Wei Y. The Impact of School Leadership on Inclusive Education Literacy: Examining the Sequential Mediation of Job Stress and Teacher Agency. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111572

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Yulu, Dan Zhou, and Yihong Wei. 2025. "The Impact of School Leadership on Inclusive Education Literacy: Examining the Sequential Mediation of Job Stress and Teacher Agency" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111572

APA StyleFeng, Y., Zhou, D., & Wei, Y. (2025). The Impact of School Leadership on Inclusive Education Literacy: Examining the Sequential Mediation of Job Stress and Teacher Agency. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111572