Disproportionate Cybersexual Victimization of Women from Adolescence into Midlife in Spain: Implications for Targeted Protection and Prevention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Contextual Variables on Cyber-Sexual Crimes

2.2. Typology of Cyber-Sexual Offenses and Age Criteria for Victim Classification

2.3. Temporal Trend Analysis by Type of Cyber-Sexual Offense

2.4. Projection of Trends and Predictive Modeling of Cyber-Sexual Crime Rates

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

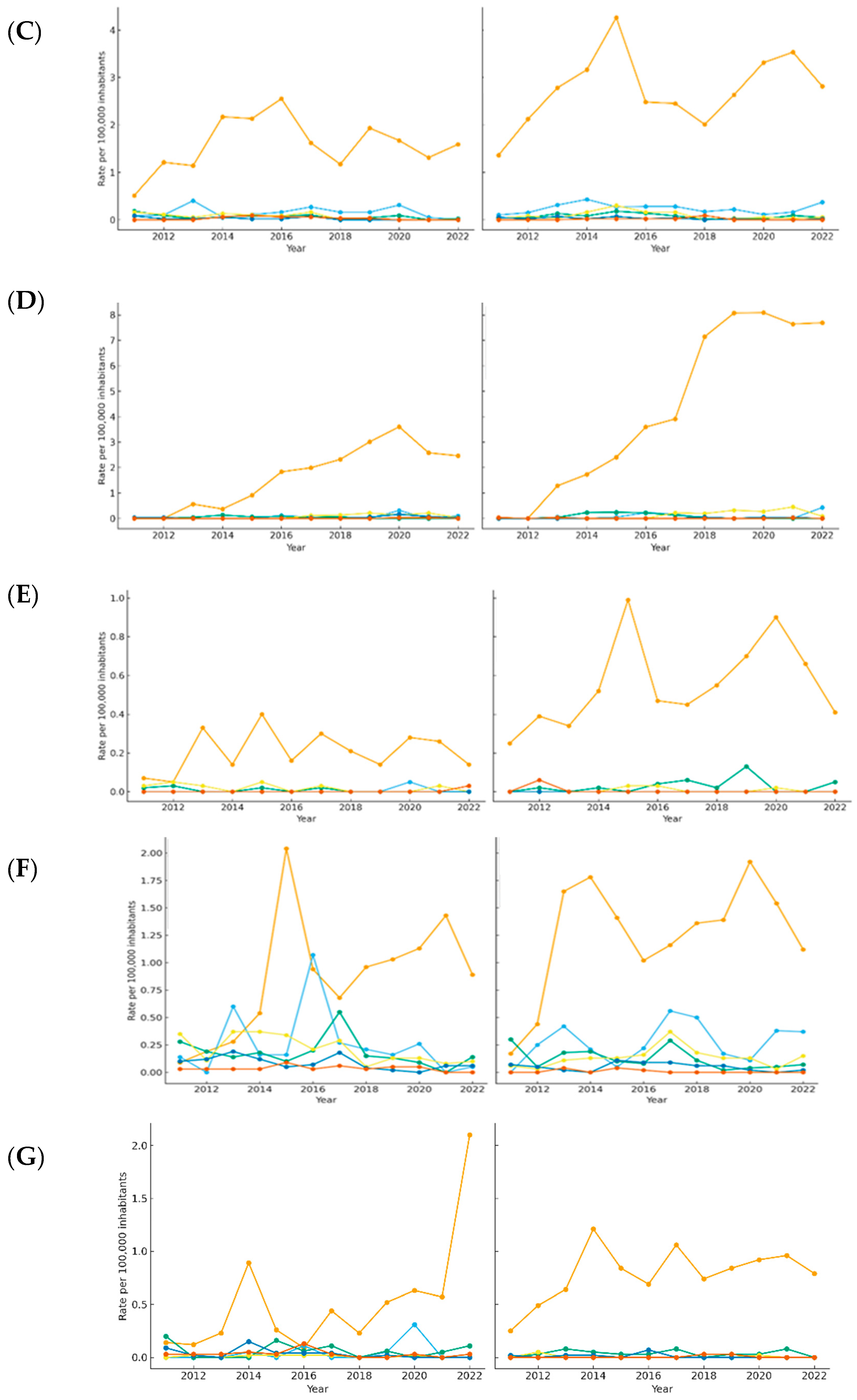

3.1. Annual Evolution of Sexual Crime Rates by Region in Spain

3.2. Regional Deviations from National Means by Offense Type

3.3. Projected Trends of National Cyber-Sexual Crime Rates in Spain (2011–2035)

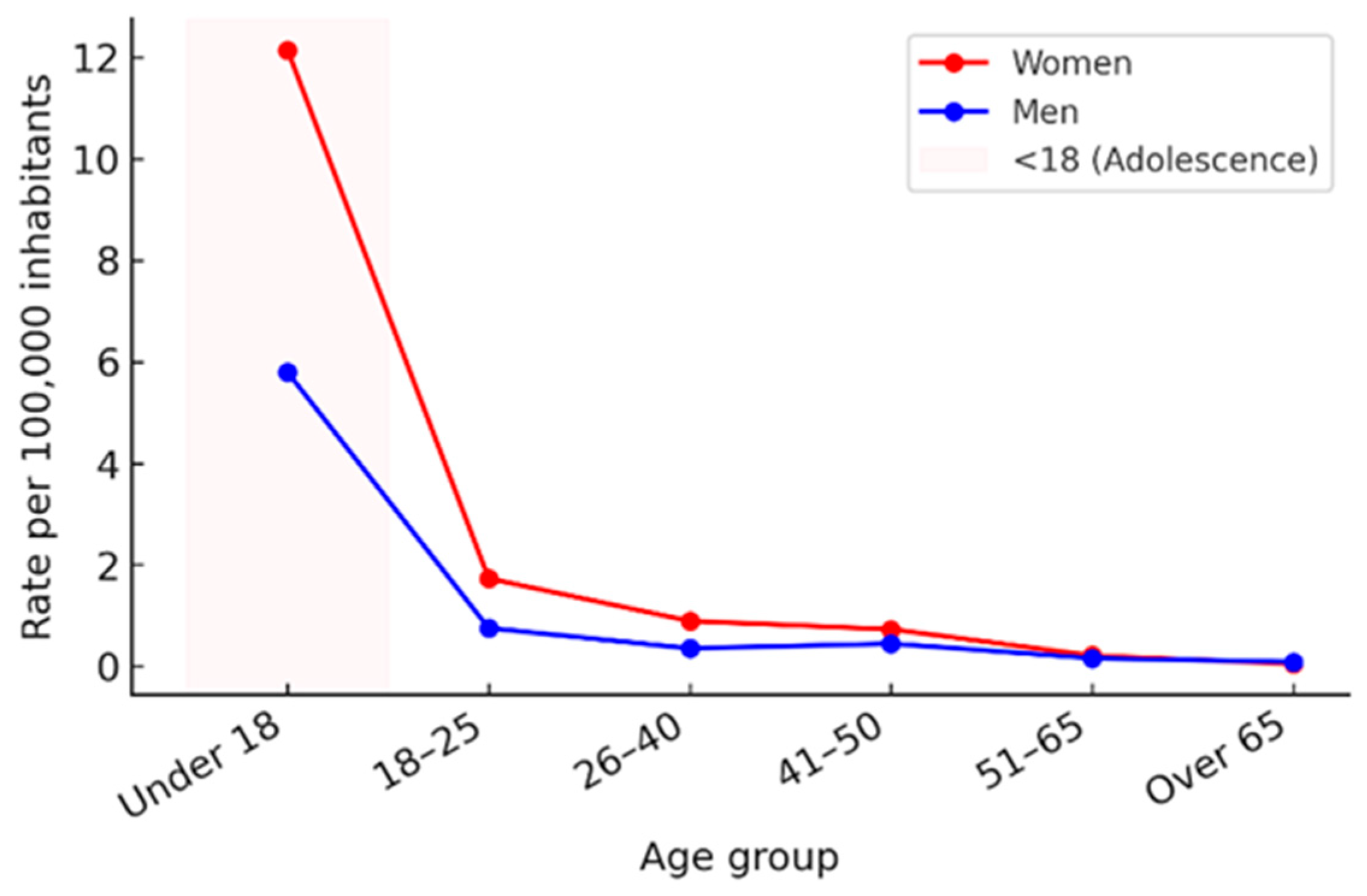

3.4. Evolution of Sexual Offense Rates in Spain by Age and Sex

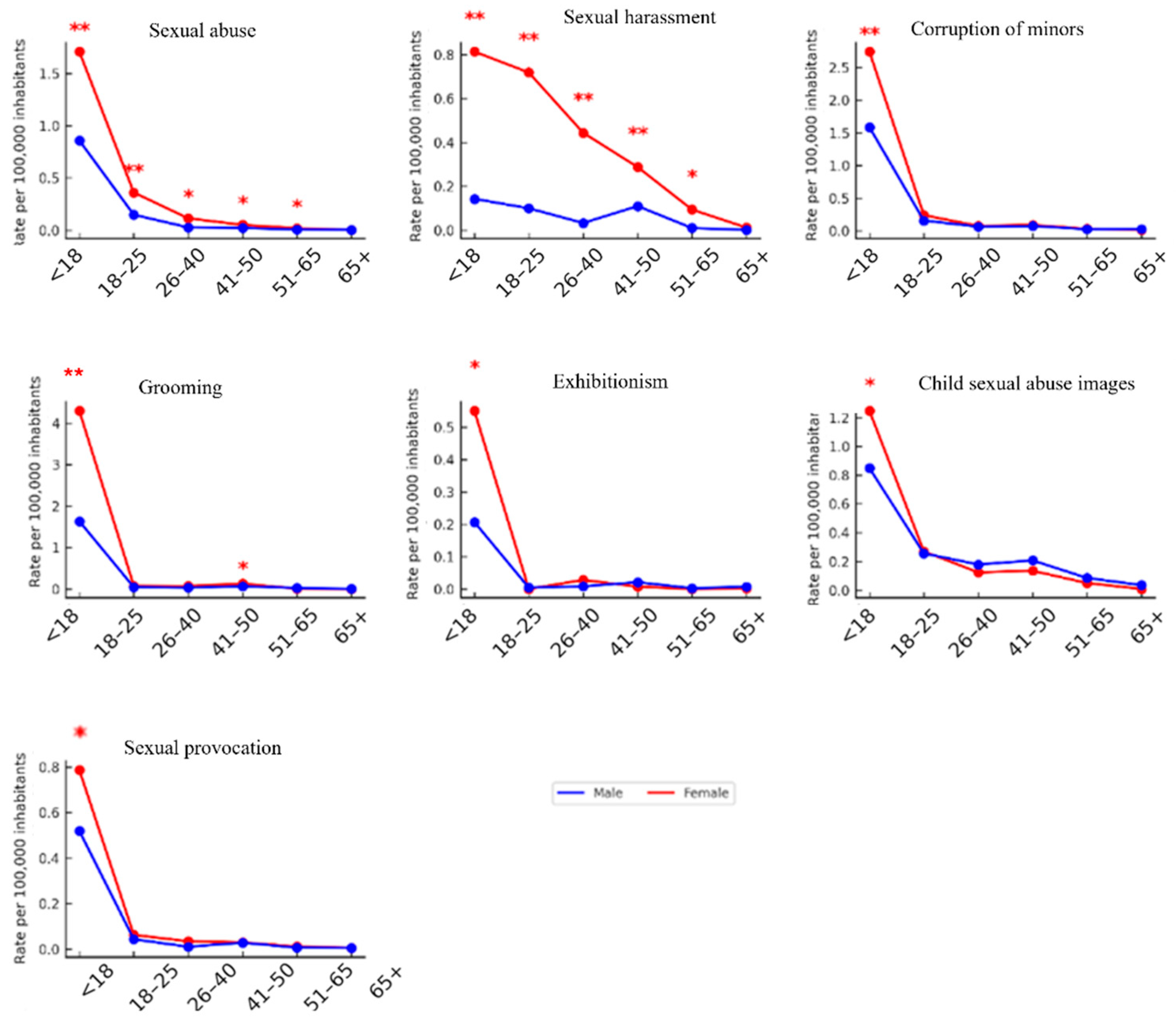

3.5. Sex-Based Differences in Cybersexual Victimization Rates Across Age Groups

3.6. Projected Trends in Cybersexual Victimization Rates in Spain by Sex and Age Group (2011–2035)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acilar, A., & Sæbø, Ø. (2023). Towards understanding the gender digital divide: A systematic literature review. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 72(3), 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, S., Asif, S., & Moulitsas, I. (2024). Examining the societal impact and legislative requirements of deepfake technology: A comprehensive study. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 14(2), 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2002). Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backe, E. L., Lilleston, P., & McCleary-Sills, J. (2018). Networked Individuals, Gendered Violence: A Literature Review of Cyberviolence. Violence and Gender, 5(3), 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomei, M. R., & Cava, A. (2024). Vulnerability, Digital Technologies and International Law: Reflections on Contemporary Migration Flows. Law, Technology and Humans, 6(2), 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, S., Warburton, W. A., Bussey, K., & Sweller, N. (2022). Beyond the screen: Violence and aggression towards women within an excepted online space. Sexes, 3(1), 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienestar y Protección Infantil. (2020). IV plan de acción contra la explotación sexual infantil y adolescente en España (2021–2024). Available online: https://bienestaryproteccioninfantil.es/wpfd_file/iv-plan-de-accion-contra-la-explotacion-sexual-infantil-y-adolescente-en-espana-2021-2024-informe-completo/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Calderón Gómez, D., Puente Bienvenido, H., & García Mingo, E. (2024). Generación expuesta: Jóvenes frente a la violencia sexual digital. Available online: https://docta.ucm.es/entities/publication/0cc09117-5d30-4a91-88a5-2557acf99ba3 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Ceia, V., Nothwehr, B., & Wagner, L. (2021). Gender and Technology: A rights-based and intersectional analysis of key trends. Available online: https://www.oxfamamerica.org/explore/research-publications/gender-and-technology-a-rights-based-and-intersectional-analysis-of-key-trends/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Datos—Portal Estadístico. (n.d.). Available online: https://estadisticasdecriminalidad.ses.mir.es/publico/portalestadistico/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- de Santisteban, P., & Gámez-Guadix, M. (2018). Prevalence and risk factors among minors for online sexual solicitations and interactions with adults. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(7), 939–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endrass, J., Urbaniok, F., Hammermeister, L. C., Benz, C., Elbert, T., Laubacher, A., & Rossegger, A. (2009). The consumption of Internet child pornography and violent and sex offending. BMC Psychiatry, 9(1), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa Zárate, Z., Camilli Trujillo, C., & Plaza-de-la-Hoz, J. (2023). Digitalization in vulnerable populations: A systematic review in Latin America. Social Indicators Research, 170(3), 1183–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Institute for Gender Equality. (2017). Cyber violence against women and girls. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/publications-resources/publications/cyber-violence-against-women-and-girls?language_content_entity=en (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Fatima, T. (2024). Navigating digital sexual violence and harassment (DSVH) in low- and middle-income countries: Scope, impact, and coping strategies. Journal of International Relations and Social Dynamics, 3(1), 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., & Colburn, D. (2022). Prevalence of online sexual offenses against children in the US. JAMA Network Open, 5(10), e2234471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatley, J. (2017). Crime in England and Wales: Year ending June 2017. Crime against household and adult, also including data on crime experienced by children, and crime against businesses and society. Office for National Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Grabosky, P. N., & Smith, R. G. (2018). Crime in the digital age: Controlling telecommunications and cyberspace illegalities (259p). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggisberg, M. (2020). Sexually explicit video games and online pornography—The promotion of sexual violence: A critical commentary. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 53, 101432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, K. N. (2016). Persistent and pervasive community. American Behavioral Scientist, 60(1), 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsper, E. J. (2017). The Social Relativity of Digital Exclusion: Applying Relative Deprivation Theory to Digital Inequalities. Communication Theory, 27(3), 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, N., Flynn, A., & Powell, A. (2020). Technology-facilitated domestic and sexual violence: A review. Violence Against Women, 26(15–16), 1828–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, N., & Powell, A. (2016). Sexual violence in the digital age: The scope and limits of criminal law. Social and Legal Studies, 25(4), 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.ine.es/ (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- International Organization for Standardization. (2020). The International Standard for country codes and codes for their subdivisions (ISO Standard No. 3166). International Organization for Standardization.

- Internet Segura for Kids (IS4K) | INCIBE. (n.d.). Who we work with—European projects. INCIBE. Available online: https://www.incibe.es/en/incibe/corporate-information/who-we-work-with/european-projects/is4k (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Jurasz, O., & Barker, K. (2021). Sexual violence in the digital age: A criminal law conundrum? German Law Journal, 22(5), 784–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., Ellithorpe, M., & Burt, S. A. (2023). Anonymity and its role in digital aggression: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 72, 101856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostin, G. A., Chernykh, A. B., Andronov, I. S., & Pryakhin, N. G. (2021, April 14). The phenomenon of tolerance and non-violence in the development of the individual in the digital transformation of society. 2021 Communication Strategies in Digital Society Seminar, ComSDS 2021 (pp. 213–216), St. Petersburg, Russia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritsen, J. L., & Davis Quinet, K. F. (1995). Repeat victimization among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 11(2), 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M. S. C., Agius, P. A., Carrotte, E. R., Vella, A. M., & Hellard, M. E. (2017). Young Australians’ use of pornography and associations with sexual risk behaviours. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 41(4), 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L. S. F. (2025). Examining the role of deepfake technology in organized fraud: Legal, security, and governance challenges. Frontiers in Law, 4, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M. L., Alison, L. A., & McManus, M. A. (2013). Child Pornography and Likelihood of Contact Abuse: A Comparison Between Contact Child Sexual Offenders and Noncontact Offenders. Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment, 25(4), 370–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacAya, J. F. M., Ribeiro, M. M., Jereissati, T., Dos Reis Lima, C., & Cunha, M. A. (2021). Gendering the digital divide: The use of electronic government services and implications for the digital gender gap. Information Polity, 26(2), 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamuth, N. M. (2018). “Adding fuel to the fire”? Does exposure to non-consenting adult or to child pornography increase risk of sexual aggression? Aggression and Violent Behavior, 41, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marganski, A. J. (2020). Feminist Theories in Criminology and the Application to Cybercrimes. In The Palgrave Handbook of International Cybercrime and Cyberdeviance (pp. 623–651). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Bacaicoa, J., Henry, N., Mateos-Pérez, E., & Gámez-Guadix, M. (2024). Online gendered violence victimization among adults: Prevalence, predictors and psychological outcomes. Psicothema, 36(3), 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mas’udah, S., Razali, A., Sholicha, S. M. A., Febrianto, P. T., Susanti, E., & Budirahayu, T. (2024). Gender-based cyber violence: Forms, impacts, and strategies to protect women victims. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 26(4), 5. [Google Scholar]

- Mee, P., Gussy, M., Huntley, P., Kenny, A., Jarratt, T., Kenward, N., Ward, D., & Vaughan, A. (2024). Digital exclusion as a barrier to accessing healthcare: A summary composite indicator and online tool to explore and quantify local differences in levels of exclusion. Universal Access in the Information Society, 24, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, J., Mekkawi, H., Hassan, J. M., Judge, M., & Hassan, M. (2023). The challenges of digital evidence usage in deepfake crimes era. Journal of Law and Emerging Technologies, 3(2), 176–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, I., Carbonell, E., & Pereda, N. (2016). Multiple online victimization of Spanish adolescents: Results from a community sample. Child Abuse & Neglect, 52, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odudu, Q. (2024). Child abuse: The emerging role of the internet and technology. SSRN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashang, S., Clarke, J., Khanlou, N., & Degendorfer, K. (2018). Redefining cyber sexual violence against emerging young women: Toward conceptual clarity. In Today’s Youth and Mental Health (pp. 77–97). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, N. E., & Sitges Maciá, E. (2025). Perfil de conducta digital, ciberdelitos y cifra negra: Análisis de una muestra española. Revista Española de Investigación Criminológica, 22(2), e887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A., & Henry, N. (2025). Sextortion: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 26(1), 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relinque-Medina, F., & Álvarez-Pérez, P. (2024). Socio-digital challenges for social work in the metaverse. The British Journal of Social Work, 54(5), 2258–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M. M., Fisher, C., Ali, P., Allmark, P., & Fontes, L. (2022). Technology-facilitated abuse in intimate relationships: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 24(4), 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S., & Rajan, B. (2023). Materiality and discursivity of cyber violence against women in India. Journal of Creative Communications, 18(1), 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, G., Powell, A., & Cameron, R. (2014). Crime and justice in digital society: Towards a “digital criminology”? International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 6(2), 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E. (2018). Pornography as a public health issue: Promoting violence and exploitation of children, youth, and adults. Dignity: A Journal of Analysis of Exploitation and Violence, 3(2), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J. B. (2020). Mediated interaction in the digital age. Theory, Culture & Society, 37(1), 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trittin-Ulbrich, H., Scherer, A. G., Munro, I., & Whelan, G. (2021). Exploring the dark and unexpected sides of digitalization: Toward a critical agenda. Organization, 28(1), 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, H., Hamilton-Giachritsis, C., Beech, A., & Collings, G. (2013). A review of online grooming: Characteristics and concerns. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18(1), 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Offense Types | Age Groups | Mean (Men) | Mean (Women) | t | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual abuse | Under 18 | 0.858 | 1.709 | −3.21 | 0.004 |

| 18–25 | 0.147 | 0.360 | −2.85 | 0.008 | |

| 26–40 | 0.026 | 0.113 | −2.95 | 0.007 | |

| 41–50 | 0.021 | 0.050 | −2.50 | 0.018 | |

| 51–65 | 0.007 | 0.018 | −2.10 | 0.041 | |

| Over 65 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.00 | 1.000 | |

| Sexual harassment | Under 18 | 0.143 | 0.814 | −3.80 | 0.002 |

| 18–25 | 0.100 | 0.719 | −3.45 | 0.004 | |

| 26–40 | 0.033 | 0.444 | −3.15 | 0.006 | |

| 41–50 | 0.110 | 0.288 | −2.40 | 0.022 | |

| 51–65 | 0.010 | 0.094 | −2.25 | 0.030 | |

| Over 65 | 0.002 | 0.012 | −2.10 | 0.041 | |

| Corruption of minors | Under 18 | 1.584 | 2.741 | −4.20 | 0.001 |

| 18–25 | 0.155 | 0.238 | −1.50 | 0.150 | |

| 26–40 | 0.063 | 0.073 | −0.80 | 0.430 | |

| 41–50 | 0.072 | 0.089 | −0.70 | 0.490 | |

| 51–65 | 0.024 | 0.028 | −0.50 | 0.600 | |

| Over 65 | 0.026 | 0.014 | 1.20 | 0.240 | |

| Grooming | Under 18 | 1.635 | 4.296 | −4.60 | 0.001 |

| 18–25 | 0.047 | 0.081 | −1.10 | 0.280 | |

| 26–40 | 0.034 | 0.074 | −1.50 | 0.150 | |

| 41–50 | 0.070 | 0.131 | −1.60 | 0.140 | |

| 51–65 | 0.027 | 0.011 | 1.30 | 0.210 | |

| Over 65 | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.60 | 0.560 | |

| Exhibitionism | Under 18 | 0.207 | 0.551 | −3.00 | 0.009 |

| 18–25 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 1.00 | 0.320 | |

| 26–40 | 0.008 | 0.028 | −1.20 | 0.240 | |

| 41–50 | 0.021 | 0.007 | 1.00 | 0.320 | |

| 51–65 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 1.00 | 0.320 | |

| Over 65 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.90 | 0.350 | |

| Child sexual abuse images | Under 18 | 0.849 | 1.247 | −2.70 | 0.012 |

| 18–25 | 0.256 | 0.270 | −0.30 | 0.770 | |

| 26–40 | 0.179 | 0.124 | 1.10 | 0.280 | |

| 41–50 | 0.207 | 0.135 | 1.20 | 0.240 | |

| 51–65 | 0.085 | 0.050 | 1.00 | 0.320 | |

| Over 65 | 0.036 | 0.009 | 1.50 | 0.150 | |

| Sexual provocation | Under 18 | 0.519 | 0.787 | −2.20 | 0.036 |

| 18–25 | 0.043 | 0.062 | −1.10 | 0.280 | |

| 26–40 | 0.010 | 0.034 | −1.50 | 0.150 | |

| 41–50 | 0.028 | 0.029 | −0.10 | 0.910 | |

| 51–65 | 0.006 | 0.011 | −0.80 | 0.430 | |

| Over 65 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.20 | 0.840 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mármol, C.J.; Luna, A.; Legaz, I. Disproportionate Cybersexual Victimization of Women from Adolescence into Midlife in Spain: Implications for Targeted Protection and Prevention. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111571

Mármol CJ, Luna A, Legaz I. Disproportionate Cybersexual Victimization of Women from Adolescence into Midlife in Spain: Implications for Targeted Protection and Prevention. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111571

Chicago/Turabian StyleMármol, Carlos J., Aurelio Luna, and Isabel Legaz. 2025. "Disproportionate Cybersexual Victimization of Women from Adolescence into Midlife in Spain: Implications for Targeted Protection and Prevention" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111571

APA StyleMármol, C. J., Luna, A., & Legaz, I. (2025). Disproportionate Cybersexual Victimization of Women from Adolescence into Midlife in Spain: Implications for Targeted Protection and Prevention. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111571