Abstract

Riverbank erosion poses a significant threat to livelihoods and infrastructure in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta (VMD), necessitating innovative and sustainable solutions. This study explores the use of old tyres as a material for embankment construction to stabilize riverbanks, combining physical reinforcement with bioengineering techniques. A pilot project was conducted in Dinh My commune, An Giang Province, where an embankment was constructed using old tyres, geotextile, riprap, and vegetation. Field measurements using the Leica TS02 Plus Total Station and Finite Element Method (FEM) modeling were employed to assess the embankment’s performance. Results indicate that the embankment effectively stabilized the riverbank, with a maximum displacement of 18 mm observed after one year. The FEM predictions closely aligned with the measured data, achieving an accuracy of 68% or higher, validating the model’s accuracy. The integration of vegetation further enhanced stability, demonstrating the potential of this approach as a sustainable and cost-effective solution for riverbank protection. This study highlights the dual benefits of erosion control and waste management, offering a replicable strategy for addressing riverbank erosion across deltaic and lowland regions. The pilot offers a scalable model for climate-resilient infrastructure in deltaic regions globally, linking erosion control with circular economy strategies.

1. Introduction

The Vietnamese Mekong Delta (VMD), a crucial agricultural and ecological hub in Southeast Asia, is increasingly threatened by riverbank erosion, a problem exacerbated by climate change and human activities [1]. With over half of its population living along riverbanks, the region experiences annual erosion rates of 10–20 m in critical zones, endangering livelihoods, infrastructure, and food security. These threats are projected to intensify due to changing monsoon patterns and rising sea levels [2,3,4,5]. In recent years, the VMD has witnessed alarming rates of riverbank and coastal erosion, resulting in serious economic and social consequences. Between 2010 and 2020, erosion damaged more than 500 km of riverbank and coastal lines, leading to an estimated economic loss of over 7000 billion VND (approximately 300 million USD) [6]. Over 30,000 households have been displaced due to erosion-related incidents [7]. In An Giang and Dong Thap provinces, entire communities were relocated after severe collapse events along the Mekong and Bassac Rivers (also called Tien and Hau rivers) [8]. In the long term, erosion not only disrupts rural livelihoods and resettlement plans but also threatens the region’s rice production and export capacity, upon which Vietnam’s food security and economy heavily rely [2].

Recent studies indicate that sediment-starved conditions in the Bassac River, driven by upstream damming and sand mining, are among the most critical contributors to channel instability [1,9]. A 2024 investigation underscored how illegal sand mining has significantly exacerbated riverbank erosion, while community awareness of its impacts remains limited [10]. A further recent study demonstrated that sand mining has intensified riverbed incision, affecting over 43% of riverbank stretches each year [11]. Furthermore, weak alluvial soils, typical of the region, are particularly vulnerable to hydraulic and structural loads [7]. These soils, mainly silty clays with cohesion values of only 5–20 kPa, have low shear strength and are highly prone to liquefaction and failure under dynamic loading, posing major challenges for stabilization [7,12,13]. These vulnerabilities are compounded by erratic rainfall patterns, intensified flooding, river traffic-induced wave impacts, and the hydrodynamic behavior of meandering channels [14,15,16,17,18]. Human-induced alterations, including unregulated construction, aggressive groundwater extraction, and poorly managed land use, exacerbate the problem and reduce the adaptive capacity of local ecosystems [10].

Traditional erosion control methods have been widely applied across the globe, showcasing effectiveness in bank stabilization [19], wave energy dissipation [16,20], and environmental protection [21,22]. In developed countries, long-term performance monitoring has demonstrated reliability in protecting critical infrastructure and urban coastlines [23,24,25]. However, hard measures often lead to ecological fragmentation, scouring at structure toes, and high maintenance costs [23,24,25]. In response to these limitations, nature-based and hybrid solutions have gained prominence. Living shorelines, vegetated geogrids, brush mattresses, and anchored coir rolls have been successfully implemented in the United States, the Netherlands, and parts of Asia to provide erosion protection while enhancing ecosystem services [26,27]. For instance, the use of mangrove restoration in the Philippines and Vietnam has demonstrated high effectiveness in wave energy attenuation and sediment stabilization [28,29]. Hybrid solutions—integrating ecological components with engineered foundations—combine the stability of hard measures with the resilience of natural systems. Examples include vegetated geotextile tubes and porous breakwaters that facilitate sediment deposition and habitat formation [30]. Comparative studies reveal that such approaches can match or outperform traditional methods in medium- to long-term performance while yielding co-benefits in biodiversity, water quality, and climate adaptation [27,30,31].

However, in Vietnam, particularly within the VMD, the adoption of innovative erosion control strategies remains in its nascent stages, with limited scholarly exploration beyond conventional riverine and coastal defences. This knowledge gap is underscored by the limited number of empirical studies on hybrid systems tailored to local soil conditions and hydrological dynamics, despite recent calls for integrated assessments of erosion drivers and sustainable interventions. Traditional erosion control methods in the VMD predominantly rely on rigid structures such as stone gabions, concrete revetments, and slope paving [23,24,25]. While effective in urban settings, these solutions are costly—three to five times more expensive than ecological alternatives—and can disrupt local ecosystems. In contrast, nature-based solutions (NbSs), including vegetative reinforcement and living shorelines, have demonstrated greater environmental sustainability globally [32,33,34,35]. Only wave attenuation features that are permeable and incorporate ecological or vegetated elements are aligned with NbS principles, whereas rigid concrete dissipators are conventional gray infrastructure. NbS interventions not only stabilize banks but also enhance biodiversity, carbon sequestration, and the resilience of riverine ecosystems to climate variability and extreme events [36]. However, their implementation in Vietnam remains limited due to technical constraints and site-specific hydrological challenges. Recognizing these limitations, there is a growing urgency for Vietnam to transition toward incorporating nature-based and adaptive management strategies into official policy frameworks [37]. In addition, Duy et al. (2025) highlighted the urgent need for enforcing conservation regulations, implementing NbSs like riparian buffers, and adopting sustainable land-use planning [12]. Addressing the interplay between natural processes and anthropogenic pressures would offer actionable insights to enhance riverbank stability, protect ecosystems, and sustain livelihoods in the VMD amidst growing environmental challenges.

While international studies have demonstrated the success of hybrid and nature-based techniques in erosion control [38,39,40], their application in Vietnam—particularly in riverine contexts—remains limited. This gap is especially pronounced in the VMD, where empirical research assessing both structural performance and ecological benefits of such approaches remains scarce. This study aims to bridge that gap by providing field-validated evidence on the feasibility, performance, and replicability of a hybrid embankment system using waste tyres. By integrating recycled materials and vegetation, the approach supports both riverbank stabilization and broader sustainability goals. This study introduces a waste tyre revetment system that repurposes discarded automotive tyres—over two million units annually in Vietnam—into modular erosion control structures. By adapting successful coastal applications to fluvial environments, the system incorporates three key innovations: (1) a scenario-based finite element stability assessment of tyre stacking configurations under envelope water levels and representative load cases, (2) integration with native vegetation to enhance ecological benefits, and (3) cost-effective anchoring systems suitable for alluvial soils [41]. The research aims to empirically validate the effectiveness of tyre revetments and develop predictive models to guide implementation. The key objective is to assess bank stability by integrating in situ displacement monitoring at a representative site along the Long Xuyen–Rach Gia channel with scenario-based finite element analysis and by validating model predictions against observations under envelope water levels and load conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

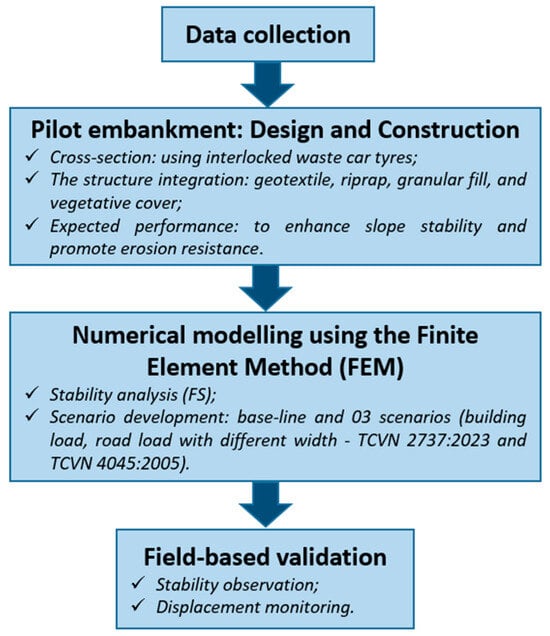

The study combines field monitoring and numerical modeling to assess the performance of tyre-reinforced embankments. The methodology was implemented in four phases (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of the research methodology, outlining the four key phases: data collection, pilot embankment design and construction, numerical modeling using the Finite Element Method, and field-based validation through displacement monitoring.

2.1. Study Area

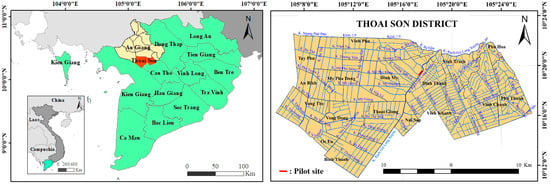

The pilot construction site in Dinh My commune (Thoai Son district, An Giang province) represents typical VMD challenges (Figure 2). The channel is 80 m wide and 8 m deep, with a discharge of 200 m3/s during the flood season. The riverbank section in the study area has experienced serious erosion in recent years. The study employs high-precision geodetic measurements and hydraulic sensors to establish a robust dataset for evaluating system performance and informing adaptive management strategies.

Figure 2.

Location of the pilot embankment site in Dinh My Commune, Thoai Son District, An Giang Province, within the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. The figure highlights the riverbank section selected for tyre-based stabilization, situated along a hydrologically dynamic channel vulnerable to erosion.

2.2. Data Collection

Secondary data, such as geology, hydrology, and cross-section of the pilot canal section of the study area, were collected from the Division of Water Resources, a unit under the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (DARD) of the province, responsible for the situation of river and canal erosion in An Giang province. The collected geological condition data were used as input for the Finite Element method (FEM) model and are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Geological conditions of soil layers beneath the embankment [42].

2.3. Embankment Pilot Design

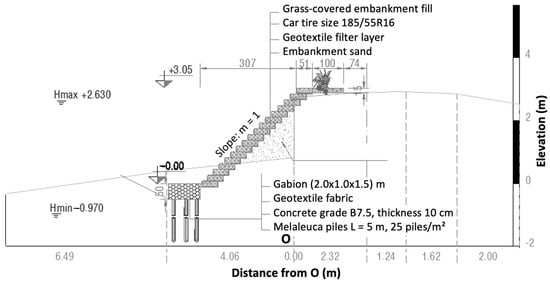

Waste tyres offer strong mechanical performance under load and are increasingly recognized for their potential in civil engineering applications, including slope stabilization and erosion control [43]. The pilot embankment structure was designed using recycled car tyres (size 185/55R16), which are widely available and commonly used in passenger vehicles, ensuring a stable and continuous supply. Each tyre has a nominal width of 185 mm, an internal diameter of approximately 406.4 mm (16 inches), and a sidewall height of about 101.8 mm (55% of the width). The tensile strength of the tyre rubber material ranges from 2000 kg/cm2 to 2400 kg/cm2, providing high durability under mechanical stress and environmental exposure. The slope protection structure was designed with a slope ratio of 1:1 (m = 1), from an elevation of 0.00 m up to the road surface at +3.05 m. Tyres were stacked in interlocked rows and fastened together using bolts to ensure structural stability (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Typical cross-sectional design of the pilot embankment constructed using interlocked waste car tyres. The structure integrates geotextile, riprap, granular fill, and vegetative cover to enhance slope stability and promote erosion resistance.

To improve foundation bearing capacity in weak soil areas, Melaleuca piles were driven at a density of 25 piles/m2, with a minimum diameter of 4 cm and a length of 5 m. Melaleuca (Melaleuca cajuputi), a native swamp species, is abundant in the Mekong Delta and widely used in traditional construction for its resistance to decay in waterlogged soils. Its use supports low-carbon, locally sourced infrastructure solutions and contributes to sustainable resource management in the region [44,45].

On top of the piles, a 10 cm thick concrete bedding layer (grade B7.5) with 4 × 6 cm coarse stone was placed to support the toe of the structure. A gabion mat wrapped in PVC mesh (2.0 × 1.0 × 0.5 m) served as a base beam for the tyre units. Granular fill sand (compacted to K ≥ 0.85) was backfilled behind and inside the tyres to restore eroded soil and stabilize the slope. A geotextile filter layer was included to prevent soil loss and maintain filtration performance. Finally, grass (Bidens pilosa) was planted in the interstitial spaces between tyres to enhance landscape aesthetics and improve erosion control.

The design adhered to relevant geotechnical and hydraulic engineering standards, including TCVN 10304:2014 (Design of Foundation Soils) [46], TCVN 8858:2011 (Geosynthetics for Civil Engineering) [47], and established guidance on slope protection using vegetation and bioengineering techniques. In addition, the HR Wallingford Tyres Manual SR 669 [48] was followed for tyre-specific detailing, such as geotextile backing to retain fines, toe protection, and tie or anchor restraints, with the caution that unstabilized infill may be lost and that lightweight units require sufficient anchoring. Considerations were also made for construction feasibility, material availability, environmental impact, and long-term maintenance requirements.

2.4. Stability Analysis Using FEM

In this study, FEM was utilized to analyze the displacement of the embankment. Additionally, the measured results from the Leica TS02 Plus Total Station were compared with those obtained from the FEM to validate the FEM model. This comparison offers a tool to gain insights into the behaviour of tyre-constructed embankments under various conditions. A geological survey was conducted in the study area to collect data on the geological conditions of the soil layers down to 30 m underground at the riverbank. Model calibration was performed using site-specific soil parameters and validated against field-monitored displacements. Sensitivity analysis confirmed that displacement trends were most affected by cohesion and surcharge loads.

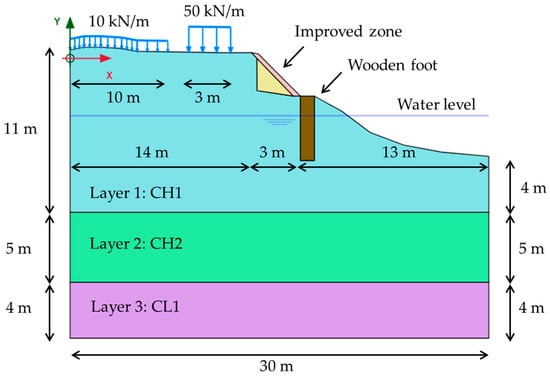

After defining the geometric characteristics, geological conditions, water level variations, and applied loads, the Factor of Stability (FS) was calculated using the shear strength reduction method in PLAXIS 2D 2021 FEM-based software (Figure 4) following the formulations in [12,49,50]:

where c is the cohesive strength in the normal state (kN/m2); φ is the internal friction angle in the normal state (0); cr is the reduced cohesive strength sufficient to maintain equilibrium (kN/m2); φr is the reduced internal friction angle sufficient to maintain equilibrium (0).

Figure 4.

The modeled zone includes a cajuput foundation layer, reinforcing weak alluvial soils. FEM simulations account for construction loads and riverbank hydrodynamics.

The reduction of parameters c and φ is governed by the variable ΣMsf, which varies at each calculation step until instability occurs. At this point, the calculation stops. The final value of ΣMsf is obtained just before the instability is the FS. In the method of reducing shear resistance:

- FS > 1: Structure is stable;

- FS = 1: Structure is at the limit of stability;

- FS < 1: Structure is unstable and prone to sliding failure.

In this study, four calculation scenarios are considered to assess the impact of building and road loads on the subgrade, taking into account water level fluctuations under two envelope water levels derived from the Long Xuyen hydrological station near the pilot site over the most recent 30-year period. Hmax = +2.63 m is the highest recorded stage, and Hmin = −0.97 m is the lowest recorded stage during that period (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the simulation scenarios for the pilot case with two water level cases.

- Scenario 1 (Current Condition): The residential building is a single-story house with a load of 10 kN/m over a frontage width of 10 m, and the road is classified as Class B with a load of 50 kN/m and a width of 3 m.

- Scenario 2 (Building Upgrade): The building is upgraded to three stories, with the load increasing to 30 kN/m, while the road remains unchanged.

- Scenario 3 (Road Upgrade): The road is upgraded to Class A, with a load of 70 kN/m and a width of 5 m, while the building remains as a single-story house.

- Scenario 4 (Full Upgrade): Both the building and the road are upgraded; the building is increased to three stories with a load of 30 kN/m, and the road is upgraded to Class A with a load of 70 kN/m and a width of 5 m.

The calculations are performed in accordance with the current standards: TCVN 2737:2023 (Loads and Actions) [51] and TCVN 4054:2005 (Highway—Specifications for design) [52].

2.5. Pilot and Validation of Stability

2.5.1. Embankment Construction Process

The embankment construction process using waste tyres was implemented in Dinh My commune, An Giang Province, following a systematic approach to ensure stability and sustainability. The process began with the preparation of materials, including waste tyres collected from local recycling centres and landfills, which were cleaned and inspected for structural integrity. Geotextile fabric was used to prevent soil erosion and enhance structural stability, while riprap stones were arranged to protect the surface from water flow and wave impact. Native vegetation was also incorporated to improve ecological and structural resilience through root reinforcement.

The construction process of the embankment using waste tyres is presented in Figure 5, which included five steps. It started with piling using cajuput, which is a very popular foundation reinforcement method in the VMD. In the second step, geotextile was laid down before riprap was placed on top of the geotextile. In the third step, waste tyres were installed as the cover of the embankment using bolt connections. The fourth step involved earth fill work, and the final step was planting vegetation. After completion, the embankment was thoroughly inspected to ensure stability and safety, with periodic maintenance measures implemented to address any wear or damage.

Figure 5.

Step-by-step construction process of the embankment utilizing waste (old) tyres. The process includes foundation reinforcement with Melaleuca piles, placement of geotextile and riprap, installation of interlocked tyre units, earth filling, and final vegetative planting for ecological stabilization.

2.5.2. Displacement Validation

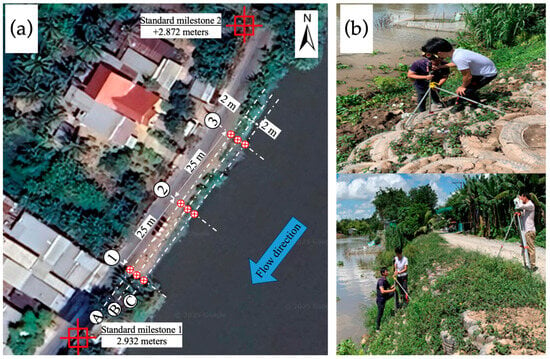

Leica TS02 plus total station survey instruments have proven effective in monitoring structural and natural displacements and are capable of tracking moving objects and making automatic measurements at rates of up to 1 Hz [53,54,55]. Prisms, mounted on each of the points to be monitored, act as targets. The total station measures the horizontal and vertical angles, as well as the slope distance to each target. From the observations obtained, the easting, northing, and height values, along with displacements in three dimensions, are computed. The targeting of the total station to each point is usually achieved using Automatic Target Recognition (ATR) or signal scanning [56]. In order to measure the displacement of the embankment, the Leica TS02 Plus Total Station was utilized. A set of nine monitoring points was established on the embankment, marked with steel benchmarks, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

(a) Layout of monitoring points along the embankment cross-sections used to assess structural performance. (b) Installation of steel benchmarks for displacement tracking using the Leica TS02 Plus Total Station.

3. Results

3.1. Status of the Riverbank After Waste Tyre Embankment Construction

The status of the riverbank after 12 months of construction of the embankment is shown in Figure 7. The route length of the waste tyre embankment solution is 60 m; the implementation plan was in accordance with the original design. In the provided image, one can observe a stretch of riverbank that has been recently reinforced using waste tyres, a method aimed at erosion control. Visual inspection indicates structural stability with no signs of cracking or displacement. This suggests that the tyres are functioning well as a retaining structure, providing the necessary support to prevent further erosion.

Figure 7.

Condition of the riverbank two months after embankment construction using waste tyres. The image shows structural stability and successful vegetation establishment, indicating early effectiveness of the hybrid revetment system in erosion control.

One notable observation is the flourishing vegetation amidst the tyre structures. The interplay between the bioengineering provided by the plants and the physical structure of the tyres is evident. This symbiotic relationship enhances the overall stability of the riverbank, as the roots of the vegetation help bind the soil, while the tyres provide a robust physical barrier against the erosive forces of the river. The successful integration of vegetation and tyre structures highlights the potential of this approach as a sustainable and environmentally friendly solution for riverbank stabilization.

3.2. Displacement of the Embankment Measured by the Leica TS02 Plus Total Station

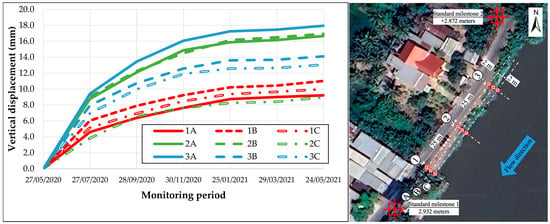

The vertical displacement monitoring results of the structure over time are presented in Figure 8. The embankment experienced its most significant vertical displacement during the first eight months of operation (from 27 May 2020 to 25 January 2021). The largest vertical displacement mark is 3A, with a deviation of 18 mm; the smallest vertical displacement marks are 1A and 2C, with a deviation of 9 mm. The vertical displacement marks are in the direction of the river but are within the allowable limits of QCVN 04–05:2022—Hydraulic structures—Essential regulations for design [57].

Figure 8.

Displacement monitoring results of the tyre-reinforced embankment over a 12-month period. Data collected from nine benchmark points indicate that all measured displacements remained within acceptable limits, confirming the structural stability of the pilot intervention.

To better understand the embankment’s deformation behavior, the results in Figure 8 were grouped and analyzed according to the three cross-sections perpendicular to the shoreline: Section 1 (1A–1B–1C), Section 2 (2A–2B–2C), and Section 3 (3A–3B–3C). Each cross-section captures the horizontal variation in vertical displacement across the slope, from the top (point A) to the toe of the embankment (point C).

- -

- Section 1 (1A–1B–1C): This section shows relatively small and uniform displacements, with 1A and 1C both measuring around 9–10 mm, and 1B slightly higher. The uniformity suggests stable soil conditions and balanced load distribution in the downstream part of the structure. These low values imply that the foundational treatment, such as piling and base concrete, was effective in this segment.

- -

- Section 2 (2A–2B–2C): Displacement values in this section range from 9 mm (2C) to approximately 14–15 mm at 2A and 2B. The relatively higher movement near the top (2A) indicates potential concentration of stress or minor differential settlement at the slope’s base, possibly due to riverbank erosion or localized soil variability. Despite this, the displacements remain within acceptable limits.

- -

- Section 3 (3A–3B–3C): This is the most critical section, with the highest measured displacement at 3A (18 mm), decreasing to 3B (around 16 mm) and 3C (slightly above 13 mm). The trend here shows greater movement near the top of the embankment (3A), diminishing toward the toe (3C), which is indicative of inward rotation or shear deformation. This section likely represents a zone of weaker subsoil or higher hydraulic influence. The results suggest the need for careful observation and possibly targeted reinforcement in this upstream area.

Overall, the cross-sectional analysis confirms that the embankment has performed well under service conditions, with deformations largely within design tolerances. However, the observed displacement gradient in Section 3 warrants additional geotechnical investigation to assess subsoil strength and long-term stability. The variation in displacement across the monitoring points can be attributed to several factors, including the local soil conditions, the intensity of river flow, and the specific load distribution on the embankment. The relatively small displacements observed suggest that the embankment is performing well under the prevailing conditions. However, the higher displacement at 3A may indicate a localized area of weakness or higher stress concentration, which warrants further investigation and potential reinforcement.

3.3. Displacement of the Embankment Modeled by FEM

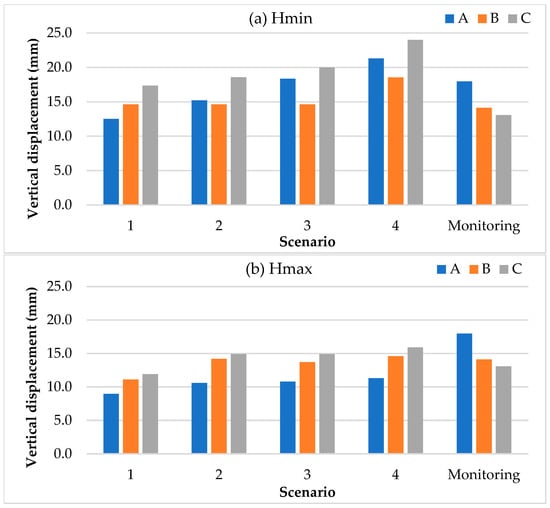

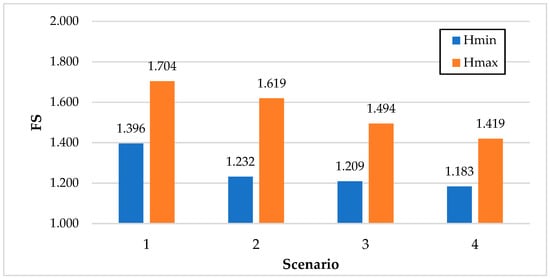

The displacement and stability analysis results from FEM simulations under four loading scenarios and two extreme water levels (Hmax = +2.63 m and Hmin = –0.97 m) are presented in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 9.

Comparison between field-measured displacements and Finite Element Method (FEM) simulation results at nine benchmark locations. In which A, B, C correspond to the monitoring points at the top, shoulder, and toe of the embankment, respectively.

Figure 10.

Stability analysis results derived from FEM simulations, which exceed the regulatory threshold (FSQCVN = 1.15) required by QCVN 04–05:2022/BNNPTNT.

Figure 9 illustrates the vertical displacement results of the embankment obtained from FEM simulations, compared against the actual field monitoring data collected using the Leica TS02 Plus Total Station instrument. The monitoring vertical displacement value used in comparison with FEM results is the maximum value at the top (A), shoulder (B), and toe of the embankment (C) of the three monitoring cross-sections. The displacement patterns predicted by FEM show good agreement with the observed data across most monitoring points, particularly under Scenario 1 (Current Condition), where the maximum simulated displacement remains consistent with the measured value of 18 mm. For Scenario 1 (Current Condition), which reflects the actual field conditions, the FEM predictions achieve an accuracy of 68% or higher compared to observed data. Notably, the Hmin case (−0.97 m) exhibits greater displacement deviations compared to Hmax (+2.63 m), indicating a higher risk under low water level conditions. This close correlation validates the accuracy and predictive capability of the FEM model for current loading conditions. However, the FEM results across all scenarios indicate that the vertical displacement at the toe of the embankment is greater than that at the top. This can be explained by the application of hydrostatic pressure based on water levels during simulation, which differs from the actual dynamic tidal variations observed in field conditions.

As the loading conditions increase across Scenarios 2 to 4, the FEM simulations predict higher displacement values, particularly at the embankment toe and downstream sections. In Scenario 4 (Full Upgrade), the calculated displacements approach the serviceability limit, indicating the need for careful consideration of future development impacts on embankment stability.

Figure 10 presents the Factor of Stability (FS) results derived from the FEM simulations for all scenarios. The analysis shows that even under the most critical case (Scenario 4), the minimum FS remains at 1.183, exceeding the regulatory threshold of FS ≥ 1.15 as required by QCVN 04–05:2022/BNNPTNT [57]. This confirms that the current embankment design with a slope ratio of m = 1.00 ensures sliding stability even under the most unfavorable combined loading conditions.

The comparison between measured and simulated displacements in Figure 9, combined with the FS evaluation in Figure 10, demonstrates that the current revetment design is both structurally stable and meets regulatory safety standards under current and anticipated future load scenarios. However, for long-term resilience, especially under extensive urbanization and infrastructure expansion, reinforcement measures should be considered.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study highlight the effectiveness of using waste tyres for riverbank stabilization in the VMD. After one year of operation, the embankment exhibited minimal displacement, demonstrating that the tyre structures can withstand the river’s erosive forces (Figure 11a). Even after almost five years of use, despite being subjected to various impacts from road upgrades and improvements—such as increased vehicle load capacity, road widening, and asphalt paving, the structure has remained stable and effective in protecting the riverbank (Figure 11b). This approach has gained support from both local residents and authorities.

Figure 11.

(a) Condition of the tyre-reinforced embankment one year after construction, showing maintained structural integrity and vegetation growth. (b) Status after five years of operation, demonstrating long-term durability despite increased road use and environmental exposure.

Compared to traditional hard engineering measures, such as concrete embankments or stone riprap, the tyre revetment offers several advantages aligned with NbS principles. Firstly, the reuse of locally sourced, discarded car tyres not only reduces construction costs but also addresses solid waste management concerns in an environmentally beneficial way. Secondly, the system allows for vegetation to grow in the interstices between tyres, contributing to bank stabilization through root reinforcement while enhancing habitat value and landscape aesthetics. Such multifunctionality is a key criterion in the IUCN Global Standard for NbS, which emphasizes ecological, social, and economic co-benefits in infrastructure design [58].

In comparison with other soft engineering methods like vegetation-based stabilization or D-Box geotextile systems [35], the waste tyre revetment offers unique advantages in cost and sustainability. Vegetation, such as mangroves, enhances biodiversity and reduces wave energy by up to 70% [28,29], but requires years to establish and is vulnerable in high-flow settings like the VMD [1,9]. D-Box provides slope adaptability, but relies on new synthetic materials, increasing costs and carbon footprint [35]. The tyre system, however, delivers immediate stability (18 mm displacement after one year), repurposes waste, integrates vegetation for ecological benefits, and offers a scalable solution for deltaic regions.

While the tyre revetment may not achieve the same level of immediate structural rigidity as reinforced concrete walls, it compensates with superior adaptability and long-term resilience—traits that are particularly critical in the context of the VMD, where subsidence, sediment imbalance, and increasing hydro-climatic variability challenge the effectiveness of rigid structures. This aligns with the strategic vision set forth in Resolution 120/NQ-CP of the Government of Vietnam [59], which advocates for a paradigm shift from “living with floods” to “proactively adapting to climate change and managing water resources sustainably” through integrated, eco-friendly solutions.

Nonetheless, some limitations must be acknowledged. The pilot study faces several constraints, including its single-site implementation within Dinh My commune, which limits the analysis of how soil type and varying hydraulic heads impact strength due to insufficient data on diverse soil profiles. Additionally, the study did not assess the percentage of waste tyre mixing or its influence on strength and stabilization, as the primary focus was on temporal stability evaluation. The long-term performance under extreme flood events, prolonged exposure to UV radiation, or biological degradation also remains unevaluated, alongside limited exposure to extreme weather events and a short monitoring period. This is recognized as a limitation, and future research will expand to multiple locations and include experiments to determine optimal tyre mixing ratios and their effects on durability. Furthermore, public perception and regulatory acceptance of using waste materials in hydraulic infrastructure remain as barriers to widespread adoption. Therefore, while the tyre revetment cannot fully replace conventional methods in all contexts, particularly in high-velocity or urban areas, it represents a valuable addition to the portfolio of riverbank protection measures, particularly in low-income or environmentally sensitive areas.

This approach exemplifies a practical and context-sensitive NbS that delivers multiple co-benefits beyond its core function of structural stability. By repurposing waste tyres—an abundant, non-biodegradable, and problematic component of Vietnam’s solid waste stream—the intervention directly addresses environmental pollution while simultaneously contributing to circular economy objectives. Integrating these materials into engineered riverbank protection structures not only diverts waste from landfills but also gives them a second life in a climate-resilient infrastructure application.

Socially, the low-cost nature of the embankment system increases its accessibility for rural and economically disadvantaged communities throughout the VMD, where budget constraints and large lead times often limit the feasibility of conventional hard engineering solutions. The use of locally available materials reduces dependency on imported or industrial inputs, making the solution scalable and replicable across similar deltaic regions. The involvement of local labor and artisans in collecting, preparing, and assembling the tyre structures generated short-term employment during the pilot phase and fostered local ownership over the intervention, which is crucial for long-term maintenance and monitoring.

Although designed for the hydrological and geotechnical conditions of the VMD, the tyre–vegetation hybrid model presented here holds potential for adaptation in other sediment-starved or subsiding deltas, such as the Ganges–Brahmaputra Delta in Bangladesh, the Nile Delta in Egypt, or vulnerable regions across South and Southeast Asia. Its low-cost, modular structure and reliance on locally available materials make it particularly suitable for data-scarce and resource-constrained settings. Environmentally, the integration of native vegetation between and around the tyre units enhances the bioengineering function of the embankment. Plants such as Bidens pilosa, with their extensive root systems, help stabilize the soil matrix, reduce surface runoff, and support microhabitat formation. Over time, this hybrid solution can contribute to increased bank resilience, sediment retention, and even ecological restoration, as the vegetated tyre revetments support riparian habitat connectivity and biodiversity regeneration. The permeability of the tyre matrix allows water to flow and sediment to settle, minimizing hydrological disruption compared to concrete revetments.

Furthermore, this model reflects key attributes including stakeholder participation, cost-effectiveness, ecological integrity, and adaptability to local conditions. It responds directly to Resolution 120/NQ-CP of the Government of Vietnam, which calls for integrated, eco-friendly, and adaptive approaches to climate change and water management in the Mekong Delta. As such, this soft-measure intervention not only stabilizes eroding riverbanks but also delivers cross-cutting benefits across social equity, ecological restoration, waste valorization, and climate resilience. It offers a compelling, scalable solution for policy-makers, engineers, and community leaders seeking sustainable alternatives to conventional infrastructure in a rapidly changing delta landscape.

As highlighted by Gonzalez-Ollauri (2022), NbSs for slope and erosion control suffer from a lack of standardized performance metrics and field-scale validation [60]. This study contributes to filling that gap by demonstrating the feasibility and stability of a tyre–vegetation hybrid embankment under real-world deltaic conditions. To enable wider application of tyre-based revetments as adaptive infrastructure in deltaic contexts, it is essential to embed recycled-material strategies within Vietnam’s formal regulatory and planning frameworks. Institutionalizing the use of waste-derived construction materials—such as discarded tyres—within national embankment design standards would not only legitimize alternative engineering practices but also reflect a shift toward more socially and environmentally responsive forms of infrastructural governance.

Equally important is the alignment of such interventions with broader policy instruments targeting climate resilience and sustainability. The inclusion of tyre-based soft-engineering solutions within the funding and programmatic priorities of key national and international organizations would enhance the visibility, legitimacy, and financial feasibility of such nature-based interventions.

Moreover, the operationalization of circular economy principles in this context requires active engagement with the informal recycling sector, which remains a vital yet underrecognized actor in the material flows of waste management in Vietnam [61,62,63]. Developing collaborative models that incorporate local recyclers into the planning and implementation process not only supports the material viability of tyre-based embankments but also advances inclusive socio-spatial outcomes, including livelihood diversification and participatory environmental stewardship at the community scale.

Institutionalizing the use of waste-derived construction materials—such as discarded tyres—within national embankment design standards would not only legitimize alternative engineering practices but also reflect a shift toward more socially and environmentally responsive forms of infrastructural governance [64,65]. Rey (2021) further argues that co-benefits of NbSs—those that combine structural stability, biodiversity enhancement, and flood mitigation—should be promoted at the river catchment scale through integrated governance and field-scale demonstration, as attempted in this pilot study [66].

Our pilot study is constrained by its single-site implementation, limited exposure to extreme weather events, and short monitoring period. Future research should extend to multiple river systems, explore long-term degradation of tyre materials under tropical conditions, and assess public perceptions and policy feasibility for mainstream adoption. This pilot intervention offers scalable insights for integrating circular economy principles into climate adaptation infrastructure in deltas worldwide, supporting Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 11, 13, and 14.

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

This study offers empirical validation for a hybrid riverbank stabilization approach that integrates waste tyres with geotextile, riprap, and vegetative cover in a flood-prone commune of the VMD. Situated within a socio-ecological landscape increasingly shaped by land degradation and infrastructure precarity, the pilot embankment demonstrated both technical stability—evidenced by a maximum displacement of only 18 mm over 12 months—and ecological promise through the integration of vegetation. These findings confirm the utility of locally adapted hybrid designs, particularly in geographies where formal engineering interventions are often cost-prohibitive or socially inaccessible.

The application of FEM further strengthens the methodological contribution of this study, providing a replicable framework for future design interventions under similar deltaic conditions. Notably, the reuse of waste tyres not only addresses a pressing environmental management challenge but also repositions discarded materials as spatially embedded assets within sustainable infrastructure systems. The approach thus intersects circular economy practices with landscape-based resilience planning.

Importantly, the embedding of vegetative components within the structural matrix underscores the value of NbSs in reconciling infrastructure needs with ecological restoration goals. Beyond its engineering performance, the embankment becomes a socio-ecological artefact—demonstrating how localized materials, traditional ecological knowledge, and adaptive design can coalesce into climate-resilient infrastructure.

Moving forward, longitudinal monitoring is essential to evaluate seasonal and interannual performance, particularly in the face of shifting hydrological regimes. Refining the FEM model with context-specific geotechnical and hydrodynamic parameters may enhance predictive fidelity. Moreover, integrating native plant species with deeper rooting systems could advance both soil cohesion and habitat complexity, reinforcing the multifunctional character of such interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.N.T., T.V.T. and C.N.X.Q.; methodology, C.N.T., N.T.B. (Nguyen Thanh Binh) and T.V.T.; formal analysis, C.N.T., T.V.T. and C.N.X.Q.; investigation, N.T.B. (Nguyen Thanh Binh), C.N.X.Q. and N.T.B. (Nguyen Thi Bay); resources, C.N.T. and C.N.X.Q.; data curation, C.N.T., N.T.B. (Nguyen Thanh Binh) and T.V.T.; writing—original draft preparation, C.N.T., T.V.T. and C.N.X.Q.; writing—review and editing, C.N.T., T.V.T., N.T.B. (Nguyen Thanh Binh), N.T.B. (Nguyen Thi Bay), C.N.X.Q. and N.K.D.; visualization, C.N.T. and N.T.B. (Nguyen Thanh Binh); supervision, C.N.X.Q., N.T.B. (Nguyen Thi Bay) and N.K.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partly funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Vietnam (No. KHCN-TNB.DT/14-19/C10) and the Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City (VNU-HCM) under grant number C2023-24-04.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Khanh Hung Construction JSC for providing us with the license for PLAXIS 2D 2021.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anthony, E.J.; Brunier, G.; Besset, M.; Goichot, M.; Dussouillez, P.; Nguyen, V.L. Linking rapid erosion of the Mekong River delta to human activities. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects; Contribution of working group II to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; 1132p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C.; Visscher, J.; Viet Dung, N.; Apel, H.; Schlurmann, T. Impacts of human activity and global changes on future morphodynamics within the tien river, vietnamese mekong delta. Water 2020, 12, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.M.H.; Huynh, T.P.L.; Tamas, P.; Woillez, M.-N.; Espagne, E.; Umans, L.; Eslami, S.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Minderhoud, P.S. How consistent are adaptation strategies with ongoing climatic and environmental changes in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Policy 2025, 168, 104064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tri, V.P.D.; Yarina, L.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Downes, N.K. Progress toward resilient and sustainable water management in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2023, 10, e1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, D.H.; Nam, V.Q.; Samadhiya, A.; Kumar, A.; Gupta, S.; Jagtap, S. Unravelling the economic impact of climate change in Vietnam’s Mekong River Delta and Southeast region. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diep, G.H.; Pham, T.D.; Tran, V.T. Assessment of the current status of changes and stability of Hau River bank, from An Giang to the river mouth. Constr. Mater. Mag.—Minist. Constr. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoai, H.C.; Bay, N.T.; Khoi, Đ.N.; Nga, T.N.Q. Analyzing the causes producing the rapidity of river bank erosion in Mekong delta. Vietnam. J. Hydrometeorol. 2019, 703, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Sarker, S.; Sarker, T.; Leta, O.T. Analyzing the critical locations in response of constructed and planned dams on the Mekong River Basin for environmental integrity. Environ. Res. Commun. 2022, 4, 101001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.D.; Thien, N.D.; Yuen, K.W.; Lau, R.Y.S.; Wang, J.; Park, E. Uncovering the lack of awareness of sand mining impacts on riverbank erosion among Mekong Delta residents: Insights from a comprehensive survey. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, E. Sand mining in the Mekong Delta: Extent and compounded impacts. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duy, D.V.; Ty, T.V.; Phat, L.T.; Minh, H.V.T.; Thanh, N.T.; Downes, N.K. Assessing River Corridor Stability and Erosion Dynamics in the Mekong Delta: Implications for Sustainable Management. Earth 2025, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Le, T.; Vo, P.L.; Ha, Q.K.; Thi, V.T.; Luu, H.D. Land Subsidence in Ho Chi Minh City and the Mekong Delta Region, Vietnam: Causes, Challenges, and Solutions. In Transcending Humanitarian Engineering Strategies for Sustainable Futures; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 39–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, A.D.; Darby, S.E.; Hong, H.M.; Tompkins, E.L.; Van, T.P. Adaptation and development trade-offs: Fluvial sediment deposition and the sustainability of rice-cropping in An Giang Province, Mekong Delta. Clim. Change 2016, 137, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, C.N.; Giang, P.H.H.; Tri, L.H.; Anh, N.P.V. Effect of load on the stability of Ong Chuong riverbank, An Giang province. Constr. Mater. Mag.—Minist. Constr. 2023, 13, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, C.; Hino, T.; Quang, C.N.; Lam, L. Effects of ship waves on riverbank erosion in the Mekong delta: A case study in An Giang province. Lowl. Technol. Int. 2020, 22, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bang, L.; Thinh, L.; Tri, L.; Duy, D.; Ty, T.; Minh, H. Research on the impacts of geological, hydrological factors on the stability of riverbanks of Cai Vung river in Hong Ngu district, Dong Thap province. Vietnam. J. Hydrometeorol. 2021, 731, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phat, L.T.; Duy, D.V.; Hieu, C.T.; An, N.T.; Lavane, K.; Ty, T.V. Initial assessment on the causes of riverbank instability in Chau Thanh district, Hau Giang province. Vietnam. J. Hydrometeorol. 2022, 740, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisserant, M.; Bourgeois, B.; González, E.; Evette, A.; Poulin, M. Controlling erosion while fostering plant biodiversity: A comparison of riverbank stabilization techniques. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 172, 106387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuoka, S.; Watanabe, A.; Hosokawa, S.; Tomari, H.; Kyousai, S. Characteristics of a wave group generated by a tanker in a river and effects of detached breakwaters as a bank erosion measure. Proc. Hydraul. Eng. 2002, 46, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Polk, M.A.; Eulie, D.O. Effectiveness of living shorelines as an erosion control method in North Carolina. Estuaries Coasts 2018, 41, 2212–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Núñez, D.A.; Bernal, G.; Mancera Pineda, J.E. The relative role of mangroves on wave erosion mitigation and sediment properties. Estuaries Coasts 2019, 42, 2124–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, N.T. Application of spring network in stabilizing the entire weak soil mass in the Mekong Delta. Constr. Mater. Mag.—Minist. Constr. 2021, 04, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hue, V.H. Construction solutions overcomes erosions in Thanh Long Island. Vietnam. J. Hydrometeorol. 2023, 754, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hue, V.H. Construction solutions prevents erosion on Vam Co Tay riverbank. Vietnam. J. Hydrometeorol. 2023, 754, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuerch, M.; Spencer, T.; Temmerman, S.; Kirwan, M.L.; Wolff, C.; Lincke, D.; McOwen, C.J.; Pickering, M.D.; Reef, R.; Vafeidis, A.T. Future response of global coastal wetlands to sea-level rise. Nature 2018, 561, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temmerman, S.; Meire, P.; Bouma, T.J.; Herman, P.M.; Ysebaert, T.; De Vriend, H.J. Ecosystem-based coastal defence in the face of global change. Nature 2013, 504, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevaña, D.T.; Garcia, J.E.; Ruzol, C.D.; Malabayabas, F.L.; Grefalda, L.B.; O’Brien, E.; Santos, E.P.; Camacho, L.D. Climate change resiliency through mangrove conservation: The case of alitas farmers of Infanta, Philippines. In Fostering Transformative Change for Sustainability in the Context of Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ty, T.V.; Duy, D.V.; Phat, L.T.; Minh, H.V.T.; Thanh, N.T.; Uyen, N.T.N.; Downes, N.K. Coastal erosion dynamics and protective measures in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton-Grier, A.E.; Wowk, K.; Bamford, H. Future of our coasts: The potential for natural and hybrid infrastructure to enhance the resilience of our coastal communities, economies and ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 51, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apollonio, C.; Petroselli, A.; Tauro, F.; Cecconi, M.; Biscarini, C.; Zarotti, C.; Grimaldi, S. Hillslope erosion mitigation: An experimental proof of a nature-based solution. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Jones, P.; Donnison, I. Characterisation of nature-based solutions for the built environment. Sustainability 2017, 9, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, C.; Spangenberg, J.H.; Schröter, B. Nature-based solutions: Criteria. Nature 2017, 543, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowińska-Świerkosz, B.; García, J. What are Nature-based solutions (NBS)? Setting core ideas for concept clarification. Nat.-Based Solut. 2022, 2, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, C.N.; Van, T.C.; Quang, C.N.X. Measures to protect the river/channel bank in mekong delta towards soft, ecology and environment-friendly engineering. J. Sci. Technol.—Univ. Danang 2018, 2, 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, J.C.; Wilcock, P.R. Metrics for assessing the downstream effects of dams. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, W04404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondolf, G.M.; Gao, Y.; Annandale, G.W.; Morris, G.L.; Jiang, E.; Zhang, J.; Cao, Y.; Carling, P.; Fu, K.; Guo, Q. Sustainable sediment management in reservoirs and regulated rivers: Experiences from five continents. Earth’s Future 2014, 2, 256–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, N.; Pasha, G.A.; Hamidifar, H.; Ghani, U.; Ahmed, A. Enhancing flood resilience: Comparative analysis of single and hybrid defense systems for vulnerable buildings. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 116, 105078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, T.; King, J.; Simm, J.; Beck, M.; Collins, G.; Lodder, Q.; Mohan, R. International Guidelines on Natural and Nature-Based Features for Flood Risk Management; US Army Corps of Engineers: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Kapetas, L.; Fenner, R. Integrating blue-green and grey infrastructure through an adaptation pathways approach to surface water flooding. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2020, 378, 20190204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quynh, N.P.; Hai, D.D.; Truong, T.V.; Hoa, V.H. Evaluation of coastal wave reduction for dyke types that reuse car tires as waveblocking materials. J. Water Resour. Sci. Technol. 2022, 73, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Water Resources Division, Department of Agriculture and Environment of An Giang province. Topographic Survey Report—Contract Package: Topographic and Geological Survey for Design of Bank Protection Model at Rach Gia Canal—Long Xuyen, Long Xuyen Quadangle Area; Water Resources Division, Department of Agriculture and Environment of An Giang province: Long Xuyen, Vietnam, 2017.

- Mohajerani, A.; Burnett, L.; Smith, J.V.; Markovski, S.; Rodwell, G.; Rahman, M.T.; Kurmus, H.; Mirzababaei, M.; Arulrajah, A.; Horpibulsuk, S. Recycling waste rubber tyres in construction materials and associated environmental considerations: A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cuong, C.; Brown, S.; To, H.H.; Hockings, M. Using Melaleuca fences as soft coastal engineering for mangrove restoration in Kien Giang, Vietnam. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 81, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma’ruf, M.A.; Arifin, Y.F.; Asy’ari, M. Utilization pattern and potential of gelam wood (Melaleuca cajuputi Powell) as a foundation structure. GEOMATE J. 2023, 25, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TCVN 100304-2014; Design of Foundation Soils. Ministry of Construction: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2015.

- TCVN 8858-2011; Geosynthetics for Civil Engineering. Ministry of Construction: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2011.

- UK Department of Trade and Industry Partners. Sustainabale Re-Use Tyre in Port, Coastal and River Engineering: Guidance for Planning, Implementation and Maintenance; Report SR 669; HR Wallingford: Wallingford, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.M.; Lansivaara, T.; Wei, W. Two-dimensional slope stability analysis by limit equilibrium and strength reduction methods. Comput. Geotech. 2007, 34, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhong, Z.; Li, Y. New criteria for defining slope failure using the strength reduction method. Eng. Geol. 2016, 212, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TCVN 2737-2023; Loads and Actions. Ministry of Construction: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2023.

- TCVN 4054:2005; Highway—Specifications for Design. Ministry of Construction: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2005.

- Hill, C.D.; Sippel, K.D. Modern deformation monitoring: A multi sensor approach. In Proceedings of the FIG XXII International Congress, Washington, DC, USA, 19–26 April 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann, H.; Glaser, A. Investigation of new measurement techniques for bridge monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2nd Symposium on Geodesy for Geotechnical and Structural Engineering, Berlin, Germany, 21–24 May 2002; pp. 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Beshr, A.A. Monitoring the Structural Deformation of Tanks; LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Azeez, A.K. Deformation monitoring using Total Stations: An evaluation of system performance. J. Geomat. Environ. Res. 2018, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- QCVN 04-05:2022/BNNPTNT; Hydraulic Structures—Essential Regulations for Design. Ministry of Construction: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2022.

- Le Gouvello, R.; Cohen-Shacham, E.; Herr, D.; Spadone, A.; Simard, F.; Brugere, C. The IUCN Global Standard for Nature-based Solutions™ as a tool for enhancing the sustainable development of marine aquaculture. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1146637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. Resolution on Sustainable and Climate-Resilient Development of the Mekong Delta; 120/NQ-CP; Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2017.

- Gonzalez-Ollauri, A. Sustainable use of nature-based solutions for slope protection and erosion control. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, M. The World’s Scavengers: Salvaging for Sustainable Consumption and Production; Rowman Altamira: Lanham, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sembiring, E.; Nitivattananon, V. Sustainable solid waste management toward an inclusive society: Integration of the informal sector. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.D.; Huynh, T.D.X.; Khong, T.D. Understanding the role of informal sector for sustainable development of municipal solid waste management system: A case study in Vietnam. Waste Manag. 2021, 124, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, P.; Anantharaman, M.; Anggraeni, K.; Foxon, T.J. (Eds.) The Circular Economy and the Global South; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; ISBN 9780429434006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomponi, F.; Moncaster, A. Circular economy for the built environment: A research framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, F. Harmonizing erosion control and flood prevention with restoration of biodiversity through ecological engineering used for co-benefits nature-based solutions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).