Abstract

Reconstruction after an earthquake is often seen as a material issue, which concerns “objects” such as houses, roofs, and streets. This point of view is supported by the mass media showing the work progress in the disaster areas, especially in conjunction with anniversaries. Rather, we should consider reconstruction as a complex social process in which cultural backgrounds, expectations, and ideas of the future come into play, without neglecting geological, historical, legislative, economic, and political factors. Combining oral history sources and archival records, the article shows the paths taken by two small towns among the most affected by the earthquake of 23rd November 1980 (Mw 6.9). These towns have made opposite reconstruction choices (in situ and ex novo) representing two classical and different ways in which human societies can face their past and think their own future. A careful analysis of these forty-year experiences, with a special focus on cultural heritage, provides useful indications for post-disaster reconstructions in which more attention to the process, and not just to the final product, should be paid.

Keywords:

disasters; earthquake; reconstruction; cultural heritage; experiences; oral history; memory; 1980 earthquake 1. Introduction

The earthquake occurred on 23rd November 1980 has been one of the most disastrous seismic events in recent Italian history. It affected a large area in Southern Italy, destroyed dozens of towns, and there were 2735 victims, 9000 injured, and 394,000 homeless [1]. Over the last few decades, the media have recounted this event by emphasizing the central government’s unpreparedness in managing relief efforts or by remembering the corruption and the wastefulness during the reconstruction phase. Moreover, many Italian scholars have concentrated their attention on political and economic aspects [2,3], especially in the area around Naples [4,5,6].

This study is part of another line of research, in which the experiences and memories of the affected populations have been investigated [7,8,9,10,11]. More specifically, it retraces the history of Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi and Conza della Campania (province of Avellino) (Figure 1)—two towns where the X MCS was reached [12,13]—which adopted opposite approaches to reconstruction. A “philological reconstruction” [14] of the old town center was the choice in Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi, whereas Conza della Campania opted for a new settlement rebuilt ex novo near the ancient center, which today has become an archaeological site. These special cases represent both future-oriented choices and two ways in which the past and cultural heritage can be preserved. The aim is to illustrate how a natural phenomenon interacts with human society and how different responses may arise from the same event. Furthermore, another purpose is to show the complex social process of reconstruction and how people after forty years evaluate and rationalize it. From this perspective, the 1980 earthquake is an extremely interesting case study, because the reconstruction act of law (Act. 219/81) granted much autonomy to the local municipality and, after four decades, a broad spectrum of different choices and outcomes is observable.

Figure 1.

Isoseismal lines of the 1980 earthquake and localization of the two studied towns (modified after Postpischl et al. [13]).

To fully understand the impact of an earthquake on human societies an ecological perspective is necessary. “The natural world and human societies are more easily understandable when they are considered as two systemic and complex realities, fully interactive with each other. They are the most strongly interactive with each other because they rest on the same material, physical, chemical and biological base” [15] (p. vi). Accordingly, “disasters occur at the intersection of nature and culture and illustrate, often dramatically, the mutuality of each in the constitution of the other” [16] (p. 24). Time is also a fundamental factor in understanding catastrophes, because the complex relationship between man and nature is historically constructed and it is based on short or long-duration social processes whereby human beings adapt to their environment [17]. Therefore, an approach capable of encompassing environment, culture, and history becomes essential. In this complex interaction, it is useful to consider the notion of “resilience”, which is widely used in disaster studies. The term has received some criticism because diverse actors infuse the concept with diverse meanings [18] but an agreement on its definition may be very productive in this field [19]. Today, the most common definition is provided by United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR): “The ability of a system, community or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, accommodate, adapt to, transform and recover from the effects of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner, including through the preservation and restoration of its essential basic structures and functions through risk management” [20].

From this perspective, it is interesting to consider how disasters affect tangible cultural heritage and, consequently, how people try (or do not try) to preserve it. In any area that has been settled for centuries, historic buildings and monuments tend to be a highly visible part of daily life. They embody the continuity of time between the generations and help define the genius loci, or spirit of place, of a settlement [21]. When a disaster occurs, the tangible legacy inherited from past generations can be damaged and at the same time, the cultural identity of a geographical locality is threatened. As Ian Convery et al. underline: “Disasters and catastrophic events can be seen as ‘happenings’ that entangle people, place and their heritage, and disasters and displacement can leave people overcome by a ‘loss of self’ and a ‘loss of place’ […]. While the intangible cultural heritage of a community might be considered as less at risk from catastrophe, in extreme cases the loss of culture bearers, or dramatic shifts in society, can result in the loss of these heritage assets” [22] (p. 2).

We will see how two small towns with a thousand-year history have decided to rebuild their settlement and cultural heritage differently. After crucial choices, a long social process started, and the witnesses interpret it in the light of the present.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is based on both archival records and oral interviews. The archives are Archivio Storico Protezione Civile (ASPC), Archivio di Stato di Avellino (ASAV), Comune di Conza della Campania (CCC), and Comune di Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi (CSL). ASPC and ASAV allow us to reconstruct how the central state dealt with the impact of the earthquake. In particular, about 600 documents have been examined, concerning both relief operations and the emergency structure that was organized in the following months [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. The local archives (CSL, CCC) show how local authorities discussed and then planned the material reconstruction of the towns. Here, about 240 documents have been consulted, including scripts of council meetings, reconstruction plans, and maps [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. Additionally, oral testimonies have been used. They provide important insights into the affected populations’ point of view [59]. In particular, the study of memory can help us to understand what are the reasons behind important choices, how these are interpreted after 40 years, and how the whole reconstruction process influences both the material circumstances and the lives of populations. All the interviews have been collected by the author between 2014 and 2017 [60,61]. Witnesses belong to different generations and social classes: there are “institutional” people (mayors or municipal administrators), adult residents in 1980, and the new generations (born after 1980, but to whom memories have been transmitted) (Table 1). Contact with the witnesses took place in different ways. In some cases, the support of municipalities and local associations was central, in others, personal knowledge networks have been activated. The use of multiple channels to know new witnesses allowed us to reach different points of view and experiences. In general, people told their stories with pleasure, except in some cases where they did not want to speak about the evening of 23rd November. This is a very significant fact, as it is a sign that for someone the trauma has not yet been worked out. The interviews were videotaped and the transcriptions in original language are available upon request. Some of them are also available on the Multimedia Archive of the Memory (Archivio Multimediale delle Memorie) [62], hosted by the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Naples “Federico II”.

Table 1.

List of witnesses with description, year of birth, and date of the interview.

3. Results: Impact, Choices and Experiences

3.1. The Earthquake and Its Impact

“I remember a beautiful day... with a hot sun and a crowded square... full of people with children” says Rosanna. The 23rd November 1980 was an unusually sweet day, and this is a leitmotiv in the collective memory of witnesses. After this pleasant picture, many people use terms such as “apocalypse” or “end of the world” to indicate the sudden impact and effects of the earthquake. In the words of Romualdo: “I heard a noise... terrible... of irons... an explosion... and instinctively I headed for the exit... but I realized that the stairs were beginning to writhe… the building collapsed on the other floors, and then the door collapsed on me... I could not go back into the house and I was in that condition overnight” (Romualdo R.). The interruption of roads and communication lines, the delay in the arrival of reliefs, and the absence of a civil protection plan were the causes that amplified the tragedy [24]. The final toll was 2735 victims, 9000 injured, and 394,000 homeless; 687 municipalities were affected, including 37 declared “devastated”, 314 “seriously damaged” and 336 “damaged” [63].

After the first moments of shock, people and communities faced different situations. Before the earthquake, Conza della Campania retained its original medieval configuration of narrow streets and closely-packed houses. These buildings collapsed in a tragic domino effect becoming a pile of stones and sand. Destruction reached 95% of the settlement (Figure 2). There were 184 dead and first aid came from the inhabitants themselves. Hence, the population abandoned the hill on 24th November, found shelter in a construction site located down the valley, and here spent the first months. “Fortunately, that building was able to accommodate many people […] we were really very crowded, but safe” remembers Luigi. The availability of a safe building to house the survivors allowed people to overcome some initial difficulties, such as the removal of rubble and the construction of temporary lodging. In the following days and months, the situation improved, thanks to the province of Bologna, which provided hundreds of volunteers and means to deal with the emergency [40].

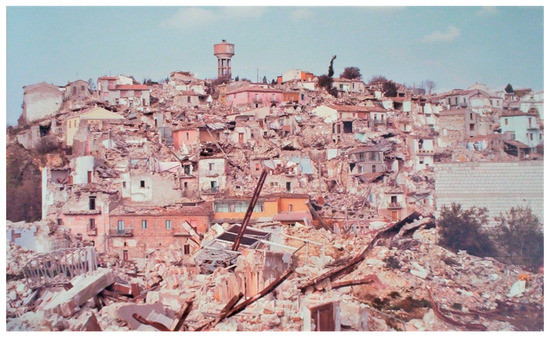

Figure 2.

Effects of the earthquake in Conza della Campania (Courtesy of Pro Loco Compsa).

The old city center of Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi also retained a medieval configuration. After the quake, it became a pile of rubble but most of the 432 deaths occurred in the “new” buildings, those that had arisen since the 1960s around the main square. These ones did not always comply with anti-seismic standards and collapsed generating the well-known pancake effect (Figure 3). “You could touch the roof of all of these buildings with your hands... they had become like an accordion” recalls Carmine. Compared to Conza, the situation was complicated, due to both the larger devastated area and the lack of the means to remove the reinforced concrete. There was no immediate availability of facilities to accommodate people, and the survivors spent the first few days in different ways as in their car or hosts by relatives in other towns. Then, the situation was brought under control thanks to the intervention of the volunteers from the Regione Toscana, and from the Provinces of Brescia and Pesaro-Urbino, who set up camps for homeless [36,37].

Figure 3.

The earthquake in Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi. On the background, the “pancake effect” (Courtesy of Michele V.).

Thanks to the famous speech by President Sandro Pertini, and to the headlines of the Italian press, the devastating impact of the eartquake had a global echo, and economic aid came from all over Italy and other nations. However, while the central state and rescuers were still dealing with the emergency, local populations, experts, and politicians began to debate the future reconstruction.

3.2. A Persistent Dilemma: Reform vs Continuity

As noted by Ian Davis and David Alexander [21], this is the first planning dilemma that authorities had to face after a disaster. Post-seism destruction certainly creates a “window of opportunity”. On the one hand, this is an occasion to change what was wrong in the past, on the other it can generate the desire to restore the old world remembered with nostalgia. Likewise, within the post-1980 debate, we can distinguish these two opposite positions. “Reformers”advocated the relocation of whole towns closer to the main roads continuing a trend that had already started before the earthquake. However, “conservers” criticized the relocation, because it was not in harmony with the agricultural vocation of the countryside, and would not have allowed the recovery of the historical-artistic heritage of the old towns. These two options, but also various intermediate solutions, could be realized thanks to both the possibilities offered by the reconstruction law and the huge amount of funds allocated. In May 1981, the government issued Act. 219, based on two keywords: “reconstruction” and “development”. The aim was to “modernize” the affected areas, still considered in a state of backwardness. More precisely, the article 27 reads: “Rebuilding takes place in the area of existing settlements and, if there are geological, technical and social reasons for it, in the municipal area as a whole. It can also be carried out by means of extensions, completions and adaptations, technical and functional, or by means of new works deemed necessary for the reorganization of an area and for its economic and social development”. All the choices took into account the Progetto Finalizzato Geodinamica—CNR, the first major national project for seismic risk assessment. This programme produced maps of seismicity and seismo-tectonics in Italy before the earthquake, and carried out surveys of damage and the potential risk to the stricken towns from seismic sources afterwards. In particular, the most important activities were focused on the production of the Structural Model of Italy, the Neotectonic Map, the Seismic Catalogue, the Atlas of Isoseismala for the largest historical events, the Seismic Hazard Map, the National Seismic Zoning, the Guidelines for seismic risk mitigation of ancient buildings, and the microzonation investigations in the epicentral areas of the 1976 Friuli and 1980 Campania and Basilicata [64,65].

In Conza della Campania the choice of relocation was shared by a large part of the population. Various reasons emerge from the field research:

- Archeological. After the removal of debris, the remains of Compsa (the original name of the ancient Roman city) came to light. The local heritage protection institution (‘Soprintendenza’) intervened to protect the archeological heritage. According to the official communication, no construction work should be undertaken in the historic center [53].

- Geological. Investigations by prof. Franco Ortolani (Department of Geology—Federico II University of Naples) underline the phenomenon of seismic site amplification on Conza hill, whereby the destructive effects of the earthquake were greater. Reconstruction in situ was not recommended [54]. More specifically, the town “was built on two small hills made by clay and sandy clay in the lower part, conglomerates with sands and sandstones in the middle part, and conglomerates of middle-low resistance in the upper part” [66] (p. 127) [67].

- Personal. For many inhabitants, the old town had become associated with the trauma they had experienced. For example, Maria went back to the hilltop for the first time in thirty years.

- Pre-existing trends. From the 1960s, a building and commercial development towards the main roads had already started. As the major in charge remembers: “Our emigrants had invested their savings to build their house there… it was along the Ofantina that commercial and craft businesses sprung up, not on the hilltop of Conza della Campania, so we started to entertain the notion of building, commercial and artisanal expansion along the slopes going down towards the valley” (Felice I.).

Differently, the townspeople of Sant’Angelo intended to restore the lost past. This choice was possible thanks to the geological investigations which considered the area of the ancient center suitable for reconstruction [68]. Various reasons can be identified:

- Status of the town. Compared to other towns of the affected area, Sant’Angelo was perceived as very relevant due to the presence of public facilities such as a prison, a court, a tax office, an ASL (local health districts) and a hospital (inaugurated in 1979). The destruction of the new buildings led also to huge economic losses. As the major in charge remembers: “Sant’Angelo was the leader town of the district [...] we thought to get the court back, to get the hospital back, to continue to playing that role” (Rosanna R.). A municipal resolution fully documents this position [42].

- Cultural/historical. In the early aftermath of the earthquake, hasty demolitions of historic buildings occurred in many small towns. In Sant’Angelo, many scholars opposed the destruction of medieval monuments and tried to recover archaeological heritage creating a “Village of cultural heritage” [43]. In Romualdo’s words, we note the intent to preserve the genius loci of the place: “We all got together united by the common intent to save identity, because if you destroy the site where a community has lived for centuries, you destroy its identity, we said: ‘we don’t need industries... let us use local resources, transplanting is useless’” (Romualdo R.).

- Personal. Unlike Conza, many people did not want to abandon the places of the tragedy. As Michele remembers: “I intended to rebuild the town where it used to be... with its history and its culture... this intent was largely shared by the townspeople… in my opinion, there was a prevalence of personal feelings, of affection, of memory, a wish to stay in the very place where these tragic things had happened… what most people wanted was to stay together, to remain at the site of the tragedy... of the memory” (Michele G.).

Therefore, starting from various reasons, these two small towns have decided to rebuild their settlement differently. In both cases, the tangible cultural heritage and the ancient history of the centers have played an important role in the decisions.

3.3. Preserving Cultural Heritage

Historical monuments and buildings, but also modern structure or landscape features, are often elements that embody the spirit of a place, or genius loci. They help to create a sense of belonging and a special connection between people who identify them as part of their own identity [69]. For these reasons, cultural heritage protection and restoration are often among the immediate priorities of recovery from disaster, although they are expensive, complex, and time-consuming processes. For example, the earthquakes that hit Italy in 1997 (in the regions of Umbria and Marche) damaged about 1200 religious buildings, and a large recovery project was set up in the aftermath [70]. In the post-1980 reconstruction debate, the recovery of historical buildings was central and each town headed for different choices [71,72]. Both of the case studies discussed here represent two ways of preserving and celebrating ancient origins, although they pursue two opposite choices for the future.

Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi became the seat of the Plan Office of Soprintendenza (Ufficio di Piano) and a strong collaboration between local scholars and from all over Italy was created. They opposed the demolitions of the old town center and established the “Cultural and Environmental Heritage Service” with the task of coordinating recovery initiatives [43]. The “Earthquake archaeologists”, as the press nicknamed the group, created a “Village of cultural heritage” and requested funding for interventions in the historic center. After the approval of the Act. 219, the Technical Commission of Cultural Heritage was formed, and it worked on the preparation of the Recovery Plan [41,46]. The aim was to consider the old town center as a whole, and not as a mere sum of buildings [44]. This conception was not applied in other Recovery Plans and, therefore, in Sant’Angelo, the technical standards were established for the specific case. Moreover, among the aims of the Plan, there were both the resettlement of the population and the start of economic activities. The restoration of the entire old town center took many years compared to the new homes. The overall time was approximately 20 years (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The cathedral of Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi, before (above) and after (below) the earthquake.

In comparison to Sant’Angelo, the recovery of the ancient Compsa had different purposes. On the one hand, the resettlement of the population was not planned, as a new town close to the main road would be built. On the other, there were Roman archeological finds to bring to light, and no damaged buildings to restore. Professor Corrado Beguinot (School of Architecture—“Federico II” University of Naples) designed the Recovery Plan which was approved in September 1982. The project considered the old settlement an economic and cultural asset, as supported by the most recent debate on the safeguarding and protection of historic centers. For this reason, interventions and restorations for tourist and cultural activities would have been scheduled. After the removal of debris, excavation and restoration campaigns were planned to create the archaeological park where an antiquarium (a sort of museum) and a seismological center would be built. The park was inaugurated in 2003 (Figure 5) [71].

Figure 5.

In the foreground, the “new Conza”. On the hilltop, the archeological park (Courtesy of Pro Loco Compsa).

3.4. After the Choices, Life Continues

Reconstruction after an earthquake is not a mere material issue concerning “objects” such as houses, roofs, and streets. To fully understand its outcomes, we should consider it as a complex social process, rather than just observing the final product. Thus, in order to illuminate the relationship between people and the environment, we have to study the various stages that the populations go through while waiting for the completion of the work. These phases constituted an important part of their own experience and help us understand how people adapt to their environment, especially after the sudden transformations caused by a major earthquake. As Sara Zizzari has shown in her study—where she combines the L’Aquila post-earthquake urban transformations with oral sources—the path to returning home is a complex social-spatial issue, which has consequences for both individual and collective paths [73]. In the cases presented here, the implementation of the plans was the starting point of a long path.

After the first months spent in the construction site, the inhabitants of Conza lived for twelve years in a valley settlement: “The urbanised area was built by the Province of Bologna according to really valid urban criteria... It really was a model of extraordinary urban cohabitation. All the spaces were well arranged... the prefabricated homes, although small, were comfortable... you got a sense of privacy, of intimacy, in short, of family, not separated, because they were contiguous and therefore in a way they restored the downhome dimension of the old town, of the neighborhood” (Luigi L.). This positive memory is largely shared among townspeople. The settlement allowed people to be as close together as they had been in the old town center. Gerardina, in turn, remembers how the condition of being “all earthquake victims” contributed to strengthening ties: “It was good in the prefabricated homes... this was a good experience... because we lived closer to each other... we were all equal and being all equal is important... there were no rich, there were no poor” (Gerardina M.). Unfortunately, after this good period, the transfer to the new town was traumatic. The “new Conza” had an urban structure very different from the old city (Figure 5). This was a long-lasting cause of disorientation for the population. As Antonia recalls: “This is a dark moment in my mind, the move to the new Conza della Campania, because at that time Conza was not a town, it was a group of houses where there were no facilities for the community... the square was not a square, there were no memories associated with those places, there was nothing for us” (Antonia P.). Since 1992, the appearance of the town has changed a lot, as new urban furniture has made the center more livable. For the younger generations, it is certainly easier to adapt to the new places, but for those who used to live in a different spatial context, the “old” Conza remains a world remembered with nostalgia.

As we have seen (Section 3.1), in Sant’Angelo there was no immediate availability of facilities to accommodate people and even establishing temporary settlements was a complicated matter. The population was larger than Conza, and they did not want to leave the destroyed town center. Thus, temporary housing sprung up in various available areas around the ruins, creating a patchwork spatial pattern. This sudden change led to a sense of displacement among the citizens, who were accustomed to a social life concentrated around the main square and the town center. Tony’s words show this lasting sense of disorientation: “For many years, this patchwork layout caused us to lose the centrality of the agora, of the main square… and perhaps we are still bearing the consequences... the square that is usually the heart of the community, where you meet, where you argue, where you walk, where you discuss... it was empty for many years... it was the ghost of the town’s main square... in the evening there was nothing at all... you could meet at one or two bars, located within these settlements or near them... for too long a period... settlement at the margins of the town led to the loss of the sense of community” (Tony L.). If in the case of Conza there are well-defined stages that the population has gone through, the transition to the “new” Sant’Angelo has been more gradual. Here, the intent was to recover the destroyed old town, to preserve its artistic and cultural identity, and to allow the resettlement of the population. Of course, restoration of ancient buildings is a time-consuming process and most of the population, after spending about fifteen years in prefabricated buildings, preferred to go and live in the new buildings at the edge of town. As Tonino underlines: “When the earthquake occurred, the historic center of Sant’Angelo was almost empty. Indeed, there were very few deaths in the historic center. People were resettled in expansion areas... this means that those whose house had collapsed in the expansion area preferred to return to the expansion area and to opt to have their home in the historic center as a second residence, because its construction would take much longer” (Tonino C.). Thus, today we can distinguish between the old part, which is well reconstructed but underpopulated, and the fragmented outskirts, where most of the inhabitants live [51].

4. Discussion

In their book, Christof Mauch and Christian Pfister recall the notion of “societies as weaving daily tapestries” [74] (p. 6). Following this metaphor, a disaster is “a gash or a sharply discordant thread suddenly introduced into the pattern”. Accordingly, a historical perspective forces analysts to see “how a society repairs/reweaves itself and moves on. In many cases, the tapestry takes off in a dramatically different direction, with new colors and designs” [75] (pp. 1–2). This fascinating idea underlies the study presented here. Forty years after the 1980 earthquake, it is possible to adopt a long-term perspective, retrace the paths taken by the affected communities, and to show how different responses may arise from the same event. Moreover, from a memory studies perspective, forty years represent a significant time frame because “after forty years those who have witnessed an important event as an adult will leave their future-oriented professional career, and will enter the age group in which memory grows as does the desire to fix it and pass it on” [76] (p. 36). As we have seen, the witnesses’ stories allow us to fully understand the upheavals caused by a great earthquake and illuminate how important decisions are made, decisions having an impact both on the environment and on the lives of populations. In other words, the memory perspective helps us to deeply investigate the complex relationship between human beings and their environment.

Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi and Conza della Campania represent two classical and different ways in which, after a great calamity, people can face their past and think their own future. The Italian sociologist Alessandro Cavalli proposed three ways whereby communities deal with the experience of space-time discontinuity. These are “ideal types”, an idea-construct of social phenomena that do not fully correspond to reality, but are meant to stress certain elements common to most cases of the given phenomenon [77]. These types are the “re-localization” (the move of the entire town), the “philological reconstruction” (which aims to restore the pre-disaster state), and the “selective reconstruction” (which preserves some symbolic elements of the past) [14]. The model of re-localization, which concerns the case of Conza, is a sort of “year zero model”, because it represents a real rebirth for the affected communities. In this case, the breaking event is celebrated in order “not to forget”, but also to symbolically mark the start of the new course. In some cases, the past may be removed. However, this does not represent the case of Conza, as the town’s ancient history is now preserved in the archaeological park, an open-air museum where the pre-quake memory has been “frozen”. The case of Sant’Angelo’s old town center corresponds to the “philological reconstruction”, which aims to restore the past from where it left off. This choice reflects the desire to reclaim both lost time and space but, in this possibility, there is also an attempt to remove the disastrous event and to delete the element of discontinuity.

Both in the “ideal types” by Cavalli and in our studied cases, tangible cultural heritage plays an important role, as buildings and historical monuments are among the elements that contribute to create the sense of a place. This is Tony’s opinion on the reconstruction of Sant’Angelo: “The choice was fundamental, the historic centre where it was, even if some mistakes were made [...] I think so... both the town as a whole and the old town centre; thanks to the choice to rebuild as it was, the mayor earned the Zanotti Bianco prize... I have shared and still share this choice today... I am in love with the historic centre” (Tony L.). However, as pointed out above, the reconstruction process is not a mere material issue. Rather, it is a complex social process involving many aspects of community life. For example, the choice to restore the past may also include the desire for a cohesive community. In the words of Tonino: “The story is interpreted in a certain way... as one of successes... that are possibly measured on the ‘material’ reconstruction... but as regards the ‘spiritual’ reconstruction, so to speak... I think that Sant’Angelo stopped existing on that exact day... in the sense that... there are still ruins” (Tonino C.). Thus, in this case, the desire to get back the lost past seems to have been partially fulfilled.

Otherwise, the old center of Conza has changed its meaning, as it has become an open-air museum from an inhabited place. Thus, while a tourist can imagine ancient civilizations by observing the remains of the ancient Roman and medieval Compsa, the inhabitants have different sensations. For some, the hilltop has become a place of death and they have had difficulty returning over time. For others, like Domenico, there is the pleasure of being a tourist guide for his friends, but also the sadness of not seeing the places of youth anymore: “Sometimes I go there... friends come and I take them to see... I bring them but when I get there... the heart suffers” (Domenico T.). Finally, Antonia, born after 1980, during her visits imagines life, stories and places transmitted by photos and family stories: “I imagine these narrow streets made of stone, these houses... always full of life, of people with their coming and going because the cars could not get the hilltop, so people in their daily lives gave life to the town because they went back and forth to do the daily chores... I imagine it as a coloured town” (Antonia P.).

What lesson can we learn from these stories? Does studying the experiences of communities affected by disasters have a purely historical interest? Or can we use this knowledge for future experiences? What is the role played by people’s memory?

According to Christian Pfister, “natural hazards are of course retained in memory if they recur frequently, and the more frequently they occur, the more likely people are to anticipate them and to try to develop adequate adaptive strategies, which are always the result of learning processes and which can take different forms” [78] (p. 4). Consequently, the memory of disasters would be able to develop a “culture of disasters” whereby human societies adapt to risky environments [79]. However, this adaptation process is not obvious because “the manner, scope and thus benefit of this implicit or explicit ‘learning’ varies greatly and depends on epoch and culture. This variation reveals the role played by history and culture in the learning process” [80] (p. 76).

Starting from historical knowledge, it may be possible to draw lessons that can be useful for living with environmental risk. In other words, stop building vulnerable settlements, being able to manage future emergencies, and planning reconstructions from a long-term perspective. All these actions should take into account the social dimension of the disaster and not only the material one. As the geographer Robert Geipel pointed out: “Disaster and reconstruction are incisive events in the life of the individual and group […]. Planning that follows only laws of a technical rationality would endanger the already injured identity” [81] (p. 152). For example, our cases inform us about the importance of maintaining social/spatial relations as similar as possible to the pre-disaster state, in order to favor the social cohesion after a traumatic experience. Furthermore, the importance of the recovery of cultural heritage is certainly a fundamental aspect of the reconstructions, as it allows establishing connection and common reference point between generations. However, a “spiritual reconstruction”, which aims to repair the social ties of the affected community, should also be pursued. In conclusion, we should start from people’s stories, because “local actors play such a crucial role in the transmission of social memory. We lack stories that can translate knowledge into a renewed sense of place and cultural identity. Local communities […] teach us about the possibility of living differently on (and with) an unstable earth” [82] (p. 77).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

First of all, I would like to thank the people who wanted to tell their story. Without their voice, this work would not have been possible. Sincere thanks go to the archives staff who made the research possible. Finally, I would like to express my deep gratitude to Gabriella Gribaudi for her precious teachings during my studies and research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References and Notes

- INGV Terremoti. Available online: http://www.ingvterremoti.com (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Osservatorio Permanente sul Doposisma. Le Macerie Invisibili. Rapporto 2010; Edizioni Mida: Pertosa, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Osservatorio Permanente sul Doposisma. La Fabbrica del Terremoto. Come I Soldi Affamano il Sud; Edizioni Mida: Pertosa, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barbagallo, F. Napoli Fine Novecento. Politici Camorristi Imprenditori; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Barbagallo, F.; Becchi Collidà, A.; Sales, I. (Eds.) L’affare Terremoto. Libro Bianco Sulla Ricostruzione; Sciba: Angri, Italy, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- De Seta, C. Dopo il Terremoto la Ricostruzione; Laterza: Bari, Italy, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Gribaudi, G. La Memoria, i Traumi, la Storia. La Guerra e le Catastrofi nel Novecento; Viella: Roma, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gribaudi, G.; Zaccaria, A. (Eds.) Terremoti. Storia, memorie, narrazioni. In Memoria/Memorie; Cierre Edizioni: Verona, Italy, 2013; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Gribaudi, G. Guerra, catastrofi e memorie del territorio. In L’Italia e le Sue Regioni (1945–2011); Salvati, M., Sciolla, L., Eds.; Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2015; pp. 251–273. [Google Scholar]

- Zaccaria, A.; Zizzari, S. Spaces of resilience. Irpinia 1980, Abruzzo 2009. Sociol. Urbana Rural. 2016, 111, 64–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, S. Non Sembrava Novembre Quella Sera; Mephite: Atripalda, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Guidoboni, E.; Ferrari, G.; Mariotti, D.; Comastri, A.; Tarabusi, G.; Sgattoni, G.; Valensise, G. CFTI5Med, Catalogo dei Forti Terremoti in Italia (461 a.C.-1997) e nell’area Mediterranea (760 a.C.-1500); Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV), 2018; Available online: https://www.earth-prints.org/bitstream/2122/11895/1/CFTI5Med_ITA.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- Postpischl, D.; Branno, A.; Esposito, E.; Ferrari, G.; Marturano, A.; Porfido, S.; Rinaldis, V.; Stucchi, M. The Irpinia earthquake of November 23, 1980. In Atlas of Isoseismal Maps of Italian Earthquakes; Postpischl, D., Ed.; CNR-PFG: Roma, Italy, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli, A. Tra spiegazione e comprensione: Lo studio delle discontinuità Socio-Temporali. In La Spiegazione Sociologica. Metodi, Tendenze, Problemi; Borlandi, M., Sciolla, L., Eds.; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2005; pp. 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Agnoletti, M.; Neri Serneri, M. The Basic Environmental History; Springer: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver-Smith, A. Theorizing Disasters. Nature, Power and Culture. In Catastrophe and Culture: The Anthropology of Disaster; Hofmann, S., Oliver-Smith, A., Eds.; School of American Research Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bankoff, G. Comparing vulnerabilities: Toward charting an historical trajectory of disaster. Hist. Soc. Res. 2007, 32, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Tierney, K. Disasters. A Sociological Approach; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, D.E. Resilience and disaster risk reduction: An etymological journey. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 13, 2707–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDRR. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Available online: http://www.undrr.org (accessed on 11 July 2020).

- Alexander, D.E.; Davis, I. Recovery from Disaster; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Convery, I.; Corsane, G.; Davis, P. (Eds.) Displaced Heritage: Responses to Disaster, Trauma, and Loss; The Boydell Press: Woodbridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Archivio Storico Protezione Civile—ANSA Notizie Varie.

- Archivio Storico Protezione Civile—Ministero dell’Interno. Direzione Generale della Protezione Civile, Terremoto del 23/11/1980—Sintesi Cronológica degli Avvenimenti Salienti.

- Archivio Storico Protezione Civile—Ministero dell’Interno. Direzione Generale della Protezione Civile, Rapporto VV.FF.

- Archivio Storico Protezione Civile—Ministero dell’Interno. Direzione Generale della Protezione Civile, Sintesi Cronológica degli Avvenimenti Salienti FF. AA.

- Archivio Storico Protezione Civile—Ministero dell’Interno. Direzione Generale della Protezione Civile, Situazione degli uomini, Mezzi e Materiali Inviati nelle Provincie Terremotate, Roma 24.11.1980, ore 14.45.

- Archivio Storico Protezione Civile—Ministero dell’Interno. Gabinetto del Ministro, Terremoto in Campania e Lucania del 23 Novembre 1980, ore 19.37, Attività di Soccorso e di Assistenza alle Popolazioni Colpite. «Situazione» n. 5—4 Dicembre 1980—ore 10.00.

- Archivio Storico Protezione Civile—Ministero dell’Interno. Direzione Generale della Protezione Civile, Roma 25.11.1980, ore 4.00.

- Archivio di Stato di Avellino—Arretramento, Interventi Assistenziali in Favore Delle Popolazioni del Territorio Dipendente dal COS n°1 di Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi, 24 Gennaio 1981.

- Archivio di Stato di Avellino—Centri Operativi. Organizzazione e Compiti.

- Archivio di Stato di Avellino—Comando Settore Avellino. Settori di Responsabilità.

- Archivio di Stato di Avellino—C.O.P. Avellino presso Caserma Berardi. C.O.S Centri Operativi di Settore.

- Archivio di Stato di Avellino—Commissariato Straordinario del Governo per la Campania e la Basilicata, Scioglimento dell’organizzazione dei Centri Operativi di Settore, 19 Giugno 1980.

- Archivio di Stato di Avellino—Riunione con i Coordinator dei CC.OO.SS., 26 Gennaio 1981.

- Archivio di Stato di Avellino—Provincia di Pesaro-Urbino, Intervento a Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi eseguito dall’Unità Operativa Servizi Speciali dell’Amministrazione Provinciale Coadiuvata da Personale di altri enti e Volontari.

- Archivio di Stato di Avellino—Centro Operativo «Toscano» Località Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi—Situazione Enti, uomini e mezzi Presenti al 9.XII.1980.

- Archivio di Stato di Avellino—Situazione Insediamenti Provvisori alla data del 13/06/1981 COS n.1.

- Archivio di Stato di Avellino—COS n.3 Situazione Insediamenti Provvisori alla data del 10/06/1981.

- Archivio di Stato di Avellino—Enti locali dell’Emilia Romagna.

- Comune di Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi—Castellano, R., De Cunzo, M., De Martino, V., Franco, V., Marandino, R., Massarelli, A. Piano di Recupero del Centro Storico, D.C. 29 Giugno 1981.

- Comune di Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi—D.C. n.20, Centro Storico: Orientamenti, 10 Aprile 1981.

- Comune di Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi—D.C. n. 1, Servizio Beni Culturali e Ambientali, 3 geNnaio 1981.

- Comune di Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi—De Cunzo, M., Restauro dei Centri Storici, in Particolare in S. Angelo dei Lombardi.

- Comune di Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi—D.C. n. 133, Adozione Piani ai sensi dell’art. 28 della legge 14.5.1981 n. 219, 16 Settembre 1981.

- Comune di Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi—D.C. n. 75, Commissione Tecnica Beni Culturali—Proposta della Giunta Municipale, 29 Giugno 1981.

- Comune di Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi—D.C. n. 2, Individuazione aree Prefabbricati, 12 Gennaio 1981.

- Comune di Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi—Criteri per L’assegnazione dei Prefabbricati, 20 Maggio 1981.

- Comune di Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi—Studio di Architettura Corrado Beguinot e Associati, Piano Regolatore Generale, Comune di Sant’Angelodei Lombardi 1983.

- Comune di Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi—Campisi, M., Corona, F., Losco, G., Piano di Recupero. Progetto di variante, Comune di Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi 1991.

- Comune di Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi—Dal Piaz, A., Apreda, A., Bruno, G., Piano Urbanistico Comunale. Relazione Generale, Comune di Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi, Aggiornamento Aprile 2019.

- Comune di Conza della Campania—D.C. n. 1/S, 8 Dicembre 1980.

- Comune di Conza della Campania—DC. n.112, 25 Settembre 1982.

- Comune di Conza della Campania—Indagine Geologico Tecnico e Geognostica dell’area del Centro Abitato, prof. Franco Ortolani, Maggio 1982.

- Comune di Conza della Campania—D.C. n. 29, 24 Maggio 1981.

- Comune di Conza della Campania—Studio di Architettura Corrado Beguinot e Associati, Criteri Generali di Impostazione del P.R.G.C. Piano per L’edilizia Economica e Popolare, Comune di Conza della Campania 1981.

- Comune di Conza della Campania—Architettura e Studi urbani Valter Bordini, Progetto di variante al Piano per L’edilizia Economica e Popolare, Comune di Conza della Campania 1984.

- Comune di Conza della Campania—Ciccone, E., Sposito, T., Ciccone, F., Strazza, G., Piano Particolareggiato di Esecuzione per la «zona B», Comune di Conza della Campania 2002.

- Portelli, A. Storie Orali. Racconto, Immaginazione, Dialogo; Donzelli: Roma, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Moscaritolo, G.I. Storia Sociale di un Terremoto. Esperienze, Memorie e Trasformazioni nel Cratere Irpino. Sant’Angelodei Lombardi—Conza della Campania (1950–2016). Ph.D. Thesis, Federico II University of Naples, Naples, Italy, 2 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moscaritolo, G.I. Memorie dal Cratere. Storia Sociale del Terremoto in Irpinia; Editpress: Firenze, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Archivio Multimediale delle Memorie. Available online: http://www.memoriedalterritorio.it (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Senato della Repubblica, Camera dei Deputati. Commissione Parlamentare di Inchiesta sulla Attuazione degli Interventi per la Ricostruzione e lo Sviluppo dei Territori della Basilicata e della Campania Colpiti dai Terremoti del Novembre 1980 e Febbraio 1981, Relazione Conclusiva e Propositiva; Tipografia del Senato: Roma, Italy, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Postpischl, D. Catalogo dei Terremoto Italiani Dall’anno 1000 al 1980; Quaderni della Ricerca Scientifica; 114, 2B; CNR-PFG: Bologna, Italy, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Siro, L. (Ed.) Indagini di Microzonazione Sismica: Intervento Urgente in 39 Centri Abitati della Campania e Basilicata Colpiti dal Terremoto del 23.11.1980. In Collaboration with Basilicata, Campania, Emilia-Romagna, Toscana Regions; 492; CNR-PFG: Bologna, Italy, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Porfido, S.; Alessio, G.; Gaudiosi, G.; Nappi, R.; Spiga, E. The Resilience of Some Villages 36 Years after the Irpinia-Basilicata (Southern Italy) 1980. In Advancing Culture of Living with Landslides. WLF 2017; Mikoš, M., Vilímek, V., Yin, Y., Sassa, K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guelfi, F.; Monteforti, B.; Bozzo, E.; Galliani, G.; Plesi, G. Comune di Conza della Campania (AV). In Indagini di Microzonazione Sismica: Intervento Urgente in 39 Centri Abitati Della Campania e Basilicata Colpiti dal Terremoto del 23.11.1980; 492; CNR-PFG: Bologna, Italy, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bosi, C.; Parducci, A.; Rossi-Doria, M. (Eds.) Comune di S. Angelo dei Lombardi: Carta Geologico-Tecnica; CNR-PFG: Bologna, Italy, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Violi, P. Paesaggi Della Memoria. Il Tempo, lo Spazio, la Storia; Bompiani: Milano, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Canti, M.; Polichetti, M.L. Marche 1997. Dai danni al restauro: Un virtuoso dialogo istituzionale. Econ. Della Cult. 2014, 24, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvigno, V. Terremoto e Ricostruzioni in Irpinia, il Restauro e i Piani di Recupero dei Centri Storici Minori. Ph.D Thesis, Federico II University of Naples, Naples, Italy, 12 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoleni, D.; Sepe, M. (Eds.) Rischio Sismico, Paesaggio, Architettura: L’Irpinia Contributi per un Progetto; CRdC-AMRA: Naples, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zizzari, S. L’Aquila Oltre i Sigilli. Il Terremoto tra Ricostruzione e Memoria; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mauch, C.; Pfister, C. (Eds.) Natural Disasters, Cultural Responses. CASE Studies Toward Global Environmental History; Lexington Books: Plymouth, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, R.S.; Gawronski, V.T. Mexico as a Living Tapestry: The 1985 Disaster in Retrospect. Nat. Hazards Obs. 2005, 30, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, J. Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. Methodology of Social Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pfister, C. “The Monster Swallows You”. Disaster Memory and Risk Culture in Western Europe, 1500–2000. RCC Perspect. 2011, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bankoff, G. Cultures of Disaster. Society and Natural Hazard in the Philippines; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schenk, G.J. «Learning from history»? Chances, problems and limits of learning from historical natural disasters. In Cultures and Disasters: Understanding Cultural Framings in Disaster Risk Reduction; Kruger, F., Bankoff, G., Cannon, T., Orlowski, B., Lisa, E., Schipper, F., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 72–87. [Google Scholar]

- Geipel, R. Long-Term Consequences of Disasters: The Reconstruction of Friuli, Italy, in Its International Context, 1976–1988; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Parrinello, G. To Whom Does the Story Belong? Earthquake Memories, Narratives, and Policy in Italy. In Sites of Remembering: Landscapes, Lessons, Policies; Lakhani, V., De Smalen, E., Eds.; RCC Perspectives: Munich, Germany, 2018; pp. 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).