Simple Summary

Donkeys are an important livestock species that play a significant role in agriculture and rural livelihoods. However, their genetic potential has remained largely unexplored. Recent advances in genomics have provided new insights into the evolutionary history of donkeys. These studies have also identified genetic factors underlying key traits related to survival and productivity, including heat tolerance, metabolism, and reproduction. Such findings are essential for improving breeding programs. They can enhance donkeys’ adaptability to diverse environments and optimize their contributions to milk, meat, and hide production. Despite these advances, the application of genomics in donkey breeding is still constrained. Small sample sizes and inconsistent data quality remain major challenges. This research proposes a roadmap to overcome these limitations. It emphasizes improved data collection, optimized breeding strategies, and sustainable conservation efforts. By addressing these issues, the study aims to support the long-term preservation of donkey populations and maximize their economic value for future generations.

Abstract

Donkeys (Equus asinus) are economically and ecologically important livestock species whose genetic potential remains underexplored. This review synthesizes recent advances in donkey genomics, tracing their evolutionary history while evaluating current applications in selective breeding, conservation genetics, and agricultural management. By integrating evidence from population genomics, functional genomics, and comparative evolutionary studies, we summarize major genomic discoveries and identify persistent knowledge gaps, with a focus on translating genomic information into practical breeding outcomes. High-quality reference genomes, population resequencing, and ancient DNA analyses have clarified the African origin, global dispersal history, and environmental adaptation of donkeys. Genome-wide approaches, including GWAS, QTL mapping, and multi-omics analyses, have further identified genes and regulatory pathways associated with thermotolerance, metabolism, reproduction, and milk production. Nevertheless, progress is still limited by small sample sizes, variable sequencing depth, and inconsistencies in phenotyping and bioinformatic pipelines, which constrain cross-population comparisons and practical applications. Addressing these challenges through standardized phenotyping, improved data integration, and collaborative research frameworks will lay the groundwork for effective conservation strategies and sustainable genomic breeding of global donkey populations.

1. Introduction

The donkey (Equus asinus), one of the earliest domesticated equids, has supported human societies for thousands of years [1]. Originating from African wild ancestors, donkeys dispersed across Eurasia and became integral to transport systems, agricultural production, and long-distance trade networks [2,3]. Today, donkeys remain essential for draft power and livelihood support in many developing regions. At the same time, their economic importance in milk, meat, and hide production is steadily increasing [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Biologically, donkeys exhibit remarkable resilience to arid environments, efficient metabolic regulation, and flexible reproductive performance. These characteristics make them a valuable model for studying adaptation and domestication within the genus Equus [12,13].

Global donkey populations are currently experiencing profound demographic and socio-economic changes. Mechanization and reduced dependence on animal traction have caused sharp population declines in many low- and middle-income countries [14]. In parallel, the rapid expansion of the ejiao industry has driven a surge in demand for donkey hides, further accelerating population losses and unregulated slaughter [15]. Together, these pressures threaten the genetic integrity of indigenous donkey breeds and undermine the livelihoods of pastoral and smallholder communities [16,17]. In contrast, intensive and semi-intensive breeding systems are emerging in China and parts of Europe, particularly for donkey milk production. Donkey milk is valued for its compositional similarity to human milk and its hypoallergenic properties [18,19,20,21,22,23]. These contrasting global dynamics highlight the urgent need to conserve genetic diversity while simultaneously improving productivity through genomics-informed and sustainable management strategies [24].

Over the past decade, technological innovation has fundamentally reshaped donkey genomics research [25]. Early draft genome assemblies provided initial insights into genome organization but were often fragmented and limited in functional annotation [26]. More recently, advances in long-read sequencing platforms, including Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and PacBio HiFi sequencing, together with Hi-C scaffolding, have enabled the generation of chromosome-level assemblies [27]. In parallel, population resequencing and ancient DNA analyses have clarified domestication processes, geographic dispersal routes, patterns of genetic diversity, and signatures of environmental adaptation [12,26,27,28,29,30,31]. As a result, high-quality donkey reference genomes have become available, creating new opportunities to investigate the genetic architecture of complex traits and to support evidence-based breeding and conservation programs [32,33,34,35,36].

Despite significant advances, several important challenges remain in donkey genomics. Compared with major livestock species, foundational insights into the genetic architecture of adaptive and production-related traits are still emerging. The genomic basis of reproductive traits, critical for population sustainability and breeding efficiency, has only recently received systematic attention. Integration of genomic data with standardized phenotypic and environmental information remains limited, and the practical translation of genomic findings into routine breeding and conservation strategies is still in its early stages. Nevertheless, recent studies have made substantial progress, providing key discoveries in evolutionary history, trait biology, and candidate gene identification. Building on these advances, this review summarizes major developments in donkey genomics, highlights important breakthroughs, identifies remaining knowledge gaps, and outlines future directions for sustainable breeding, effective conservation, and responsible industry development.

2. Materials and Methods

This review followed a structured literature-based approach to summarize advances in donkey genomics, genetic diversity, and trait-related biology. Studies published between 2000 and 2025 were primarily retrieved from the Web of Science Core Collection, chosen to ensure coverage of peer-reviewed SCI literature, with supplementary searches conducted in PubMed, Scopus, Elsevier, and Google Scholar. Search terms were applied using combinations of keywords related to donkey (Equus asinus), genomics, genetic diversity, domestication, phenotypic traits, adaptive evolution, and multi-omics, linked by Boolean operators (AND/OR).

Articles were screened through title, abstract, and full-text evaluation. Inclusion was limited to peer-reviewed studies reporting primary genomic or phenotypic data or providing comprehensive analytical syntheses relevant to breeding, adaptation, or conservation. Conference papers and book chapters were excluded. Non-SCI sources were generally excluded to ensure data reliability, although recent high-impact preprints were examined qualitatively to capture emerging trends when consistent with peer-reviewed evidence. In total, more than 420 articles were initially screened, and 161 studies were ultimately included in this review. The final set of studies formed the basis for the synthesis and interpretation presented in this review.

3. The Construction and Optimization of the Donkey Reference Genome

3.1. Evolution of Genome Assembly Technologies in Donkeys

Early donkey genome assemblies, initiated around 2015 and built primarily with short-read sequencing platforms, provided essential but fragmented references that limited the resolution of structural variants and gene organization [26]. Despite these constraints, these early efforts laid the groundwork for comparative analyses with other equids and offered preliminary insights into donkey evolutionary history. A major improvement was achieved through proximity ligation approaches such as the Chicago/HiRise system, which substantially enhanced scaffold continuity and enabled the detection of chromosomal rearrangements, providing early evidence of karyotypic divergence within Equus [28]. Subsequent assemblies, including the Texas donkey genome, further improved assembly completeness and annotation accuracy, establishing a stable foundation for studies of population differentiation and domestication [26].

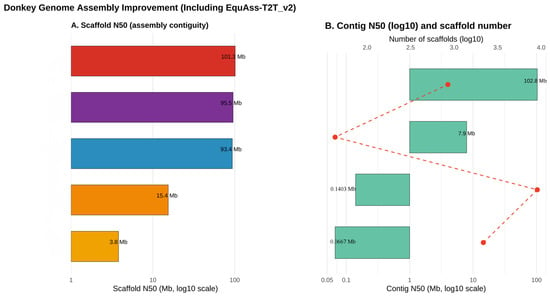

More recently, the integration of advanced sequencing and scaffolding technologies has enabled a transition from reference-quality drafts to true chromosome-level assemblies [37]. The incorporation of long-read sequencing platforms (PacBio SMRT and Oxford Nanopore), together with Hi-C chromatin conformation capture and optical mapping, has allowed accurate haplotype phasing and the reconstruction of structurally complex genomic regions [38,39]. For the first time, repetitive regions such as centromeric and subtelomeric sequences could be reliably assembled, revealing lineage-specific rearrangements and mechanisms underlying hybrid incompatibility between donkeys and horses [40,41,42,43]. These cumulative advances, summarized in Figure 1, have fundamentally transformed the resolution achievable in donkey genomics and now serve as the cornerstone for high-resolution comparative analyses and for exploring the genomic basis of reproductive isolation, karyotype evolution, and species adaptation.

Figure 1.

Comparison of donkey genome assembly quality improvement. The data, derived from references [26,27,28,44,45]. (A) Scaffold N50 values (Mb, log10 scale), where colored bars represent different genome assembly versions (reference numbers in brackets). (B) Contig N50 values (Mb, log10 scale; green bars) and scaffold numbers (log10 scale; red dots). Red dotted lines connect scaffold numbers to their corresponding assemblies, illustrating changes in assembly contiguity and fragmentation.

3.2. Multi-Omics Integration for Functional Genome Annotation

Building upon these robust assemblies, the integration of multi-omics data has shifted the focus from genome structure to function. Combined RNA-seq, Iso-Seq, and ATAC-seq datasets have expanded gene models, resolved alternative splicing, and mapped cis-regulatory landscapes across tissues [46,47,48]. These efforts have revealed the distribution and regulation of protein-coding and non-coding RNAs, while long-read structural variant analyses have pinpointed genomic regions associated with domestication, adaptation, and production traits [30,49]. Together, these developments represent a conceptual transition in donkey genomics—from constructing the genome to interpreting its biological meaning—providing the framework for connecting genotype to phenotype and for guiding future breeding and conservation programs.

4. Population Genomics and Domestication History of Donkeys

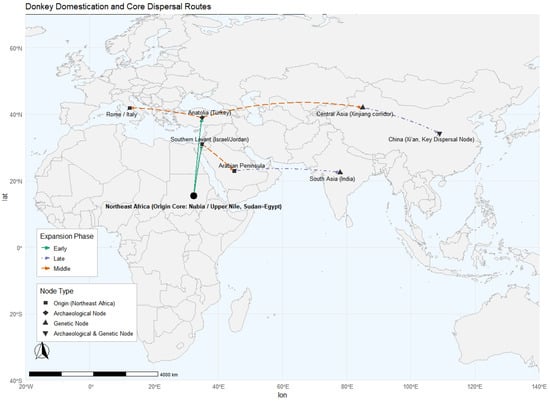

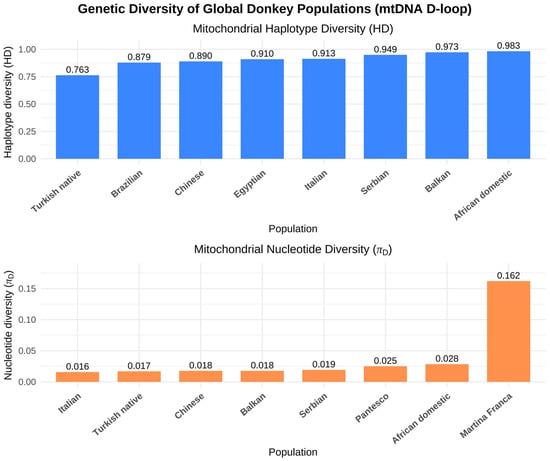

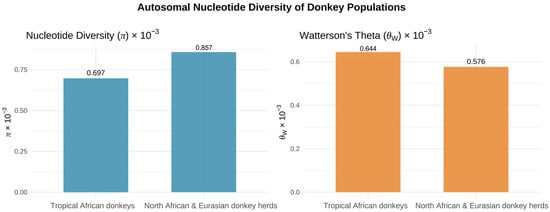

Recent population genomic studies have profoundly expanded our understanding of the evolutionary origins and diversification of domestic donkeys (Equus asinus) [12]. Figure 2 illustrates the reconstruction of donkey domestication centers and principal dispersal routes based on integrated archeological and genetic evidence. High-coverage resequencing across global populations has revealed complex demographic histories shaped by multiple dispersal events, recurrent gene flow, and region-specific adaptation [50,51]. The global distribution of mitochondrial DNA D-loop haplotype diversity is shown in Figure 3, based on mtDNA D-loop sequences compiled from published datasets. African donkeys generally retain the highest genomic diversity, reflecting their proximity to ancestral wild populations, whereas many Asian and European populations exhibit reduced heterozygosity—likely a consequence of founder effects, demographic contractions, and prolonged artificial selection [52,53,54]. Figure 4 presents autosomal nucleotide diversity patterns across African and Eurasian donkey populations, highlighting variation derived from genome-wide data. Despite these insights, the global population structure of donkeys remains only partially resolved due to uneven sampling, especially from Africa, and limited integration between genomic, archeological, and historical evidence.

Figure 2.

Reconstruction of donkey domestication centers and principal dispersal routes based on integrated archeological and genetic evidence [2,3,26,55,56]. Colored dashed lines indicate different expansion phases. Node shapes denote evidence types: squares, origin center (Northeast Africa); diamonds, archaeological nodes; upward triangles, genetic nodes; and inverted triangles, nodes supported by both archaeological and genetic evidence.

Figure 3.

Global distribution of mitochondrial DNA D-loop haplotype diversity in donkey populations. Analysis based on mtDNA D-loop sequences compiled from published datasets [55,57,58,59,60,61,62,63].

Figure 4.

Autosomal nucleotide diversity patterns across African and Eurasian donkey populations. Data derived from [26].

4.1. Genomic Signatures of Adaptation and Selection

Genome-wide selection scans in donkeys have identified candidate loci associated with thermoregulation, osmoregulation, metabolism, and skeletal morphology, providing molecular evidence for adaptation to arid and high-temperature environments and for selection on locomotor efficiency and load-bearing capacity during domestication [64,65,66]. Ancient DNA (aDNA) analyses further place the initial domestication of donkeys in northeastern Africa approximately 5000–7000 years before present, broadly consistent with archeological records [1]. However, discrepancies between archeological interpretations and molecular clock estimates persist, likely reflecting challenges related to degraded aDNA and limited sample sizes. Importantly, although many selection signals have been consistently detected across studies, their biological effects remain largely inferred from genomic correlations. Future work should therefore prioritize functional validation using in vitro systems and model organisms to move beyond association-based evidence and to identify causal genes and mechanisms underlying key adaptive and production-related traits.

4.2. Multi-Origin Domestication and Genetic Admixture

Comparative analyses of ancient and modern donkey genomes reveal a far more dynamic domestication history than previously assumed [2]. Rather than reflecting a single origin, high-coverage African aDNA demonstrates continuity with extant Equus africanus populations, while Eurasian archeological genomes contain signatures of later demographic turnover, recurrent introgression, and population replacement [2]. These patterns indicate that donkeys were repeatedly dispersed and reshaped through human-mediated exchange across transcontinental trade networks such as the Red Sea and Silk Road routes [67,68,69]. Importantly, recent time-calibrated nuclear genome analyses also reveal that domestication involved not only repeated dispersal and admixture events but also a series of region-specific demographic shifts that shaped population structure over time—patterns that were not captured by earlier two-clade domestication models [28].

Uniparental markers contribute complementary perspectives but also highlight the need for genome-wide resolution. Mitochondrial haplogroups (Clades I and II) point to at least two maternal domestication events [56], while the extremely reduced Y-chromosomal diversity reflects strong male-mediated bottlenecks consistent with early breeding systems [54]. However, these markers offer limited power to capture the functional consequences of admixture and selection [70]. Recent integrative frameworks combining uniparental markers, high-resolution nuclear genomes, and calibrated aDNA now reveal directional gene flow among regional lineages and identify functional regions shaped by domestication-related pressures [31,34,71]. This emerging evidence moves the field beyond simple phylogenetic reconstruction toward understanding how demographic processes and selection jointly shaped the genomic architecture of modern donkeys.

5. The Genomic Basis of Economic Traits in the Donkey

Recent genomic studies have increasingly elucidated the genetic architecture underlying production, adaptive, reproductive, and dairy-related traits in donkeys. These traits are often interconnected rather than independent, with overlapping genetic control influencing growth, thermotolerance, metabolic efficiency, reproductive performance, and milk traits [2,26,33,50,72].

5.1. Production and Adaptive Traits

Donkey populations from Africa, the Mediterranean, and China display pronounced variation in body size, musculature, and skin characteristics, reflecting adaptation to diverse ecological and husbandry conditions. Genomic studies have repeatedly highlighted LCORL–NCAPG and IGF1 as associated with growth and body size, where LCORL promotes limb and body elongation through transcriptional regulation of growth-related pathways, NCAPG modulates cell proliferation and muscle fiber hypertrophy, and IGF1 enhances chondrocyte and myoblast differentiation to drive skeletal and muscular development [73,74]. Pigmentation and skin-structure genes such as MC1R, ASIP, and TBX3 influence coat color and dermal traits, with MC1R and ASIP regulating eumelanin–pheomelanin switching and TBX3 contributing to hair follicle patterning and epidermal development [26,75,76]. Genes regulating lipid metabolism and muscle fiber development also contribute to carcass composition and meat quality, partly through modulation of intramuscular fat deposition, oxidative vs. glycolytic fiber ratios, and postmortem muscle biochemical properties [77,78]. Positive selection signals in genes involved in osmoregulation, thermotolerance, and metabolic efficiency across donkey populations suggest that renal ion transport, heat-shock protein activity, and mitochondrial energy pathways have been recurrent targets of adaptation, indicating that adaptive capacity and production traits may have co-evolved under combined natural and artificial selection pressures [34,79,80]. Table 1 summarizes the key candidate genes and their associated phenotypic traits identified through donkey genomics research. Nevertheless, most associations remain statistical rather than functionally validated, and differences in trait definitions across studies limit direct comparisons.

Table 1.

Summary of key candidate genes and their associated phenotypic traits identified through donkey genomics research.

5.2. Reproductive and Dairy Traits

Reproductive traits constitute an essential component of donkey economic value. Candidate genes such as GDF9 and BMP15 and their downstream signaling pathways play key roles in oocyte development and folliculogenesis, where GDF9 promotes granulosa cell proliferation and cumulus expansion through SMAD2/3-mediated signaling, and BMP15 regulates follicle growth, ovulation rate, and oocyte maturation by modulating granulosa cell differentiation and FSH sensitivity [91,93]. While candidate gene and transcriptomic analyses provide insights for genetic improvement of reproductive traits, low heritability and strong environmental effects constrain short-term genetic gains [33,94,95]. Effective enhancement of reproductive performance requires combining genomic prediction with optimized management strategies, including estrus synchronization, artificial insemination, and targeted nutritional interventions [96,97].

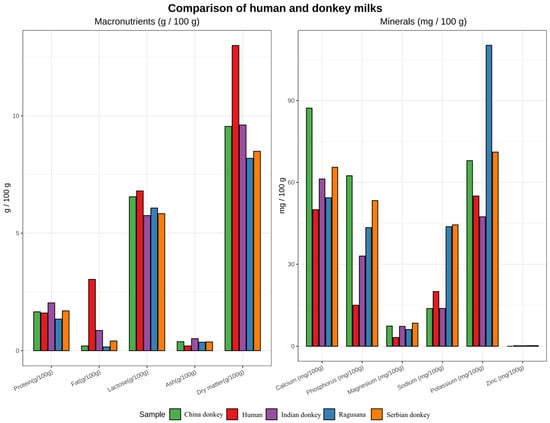

Donkey milk exhibits a distinctive composition characterized by a low casein-to-whey protein ratio and elevated concentrations of lactose and lactoferrin, resulting in biochemical and bioactive properties that closely resemble human milk [98,99]. Figure 5 presents a comparative compositional analysis of macronutrients and minerals in donkey milk from different breeds relative to human milk. Genetic determinants influencing milk composition, including variants in the CSN gene family and copy number variations in LYZ, represent potential targets for selection, with CSN gene variants affecting casein micelle formation, protein stability, and digestibility, and LYZ copy number influencing lysozyme expression and antimicrobial activity in milk [100,101,102,103]. However, standardized lactation phenotyping and functional validation across breeds remain limited [104].

Figure 5.

Comparative compositional analysis of macronutrients and minerals in donkey milk from different breeds relative to human milk. Data were compiled from published literature sources [105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113], including multiple donkey breeds and human reference datasets. Key macronutrients (protein, fat, and lactose) and major minerals are shown using standardized concentration metrics on a comparable scale. The figure was generated using R (version 4.4.1) based on literature-derived datasets.

5.3. Multi-Omics Integration and Functional Verification of Candidate Loci

Multi-omics integration is essential for converting statistical associations into mechanistic insights of candidate genes in donkeys. Rather than relying on single-layer analyses, effective workflows combine genome-wide association studies (GWAS) or genome-wide selection scans with tissue-specific transcriptomics (RNA-seq), epigenomics (ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq), proteomics, and metabolomics [80,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122]. Figure 6 shows a simulated framework from GWAS to functional verification of the LCORL–NCAPG pathway. Transcriptomic and epigenomic data reveal tissue- or stage-specific gene regulation, while proteomic and metabolomic layers capture downstream functional consequences of genetic variation [115,117,120]. Integrating these layers enables the identification of causal alleles, functional networks, and biomarkers for traits of interest. Nevertheless, most donkey studies still rely on low-coverage whole-genome resequencing in geographically restricted, small populations, which reduces statistical power, increases false-positive associations, and limits replication and functional validation [27,123,124]. These constraints hinder the translation of genomic discoveries into practical breeding or conservation strategies.

Figure 6.

From genome-wide association analysis to functional verification: research framework and GWAS visualization of the LCORL–NCAPG pathway in donkey growth traits. Growth-related phenotypes were measured following China National Standard GB/T 29392-2022 and common livestock measurement protocols [125]. The content is derived from published studies [2,24,26,31,38,124,126] based on GWAS results from multiple donkey populations. The figure was visualized using R (version 4.4.1). Horizontal dashed lines indicate genome-wide significance thresholds (p < 5 × 10−8); vertical lines highlight the LCORL–NCAPG region, supported by meta-analysis of three independent replicates.

To overcome these limitations, donkey studies should adopt rigorous experimental designs, including increasing sample sizes where feasible, standardizing phenotyping protocols, recording environmental covariates, and applying statistical corrections for population structure and relatedness [127]. Multi-omics data can be integrated into a unified functional genomics framework: GWAS or selection scans define candidate loci (“genomic coordinates”), transcriptomic and epigenomic data reveal tissue- and context-specific expression, and proteomic or metabolomic layers provide evidence of downstream functional effects [115,128]. Causal inference approaches, such as gene regulatory network reconstruction or Mendelian randomization, further strengthen mechanistic interpretation [129,130]. Applying this integrative framework in donkeys enables systematic validation of candidate loci, clarifies allele-to-trait relationships, and supports evidence-based genomic selection strategies that optimize adaptive or production traits while preserving genetic diversity.

6. Applications of Genomics in Donkey Breeding and Conservation

Genomic technologies are increasingly applied to donkey breeding and conservation management [26,51]. Beyond describing population structure, recent genomic analyses provide actionable insights that can guide selection, maintain diversity, and enhance adaptive potential. GWAS and whole-genome resequencing across multiple populations have identified genomic regions associated with body size, coat color, metabolic efficiency, and reproductive traits [51,80]. For example, Dezhou and Yangyuan donkeys in China exhibit significant SNP signals linked to growth and pigmentation, whereas the Martina Franca and Ragusano breeds in Italy show localized selection in genes influencing body conformation and reproduction [33,36,50]. These findings offer a genomic foundation to inform strategic breeding and conservation plans.

To translate genomic insights into practical management, population-level indicators such as Runs of Homozygosity (ROH), genomic inbreeding coefficients, and nucleotide diversity can be incorporated into genomic mating programs that minimize relatedness, prevent excessive homozygosity, and preserve rare haplotypes [131,132,133]. Conservation units can be prioritized using diversity-based genomic ranking, emphasizing low-inbreeding maternal lines and implementing controlled outcrossing for high-ROH lineages [16]. Beyond mating decisions, genomic data can guide nutrition to enhance reproduction; for example, in Martina Franca jacks, hemp-based PUFA supplementation improved membrane lipids and fertility [134]. This example highlights the practical translation of genomic knowledge into farm-level interventions that optimize breeding performance. However, the routine application of whole-genome sequencing or high-density SNP arrays remains economically challenging in many low-income regions where donkeys are most critical to livelihoods, as per-sample costs can be an order of magnitude higher than locally sustainable breeding budgets. In this context, low-density SNP panels combined with imputation or ddRAD-seq genotyping offer cost-effective alternatives, enabling population monitoring, nutritional guidance, and inbreeding control at a fraction of the cost while retaining sufficient resolution for management decisions [50]. Integrating these genomic metrics with phenotypic and pedigree data further improves breeding value estimation and supports marker-assisted management of economically important loci [33,50].

Comparative genomic studies reveal pronounced geographic differentiation among donkey populations, reflecting divergent evolutionary histories and management practices. African donkeys, including Abyssinian, Afar, and other breeds from the Horn of Africa and East Africa, harbor high genomic diversity and adaptive alleles associated with thermotolerance, drought resilience, and immune function, consistent with long-term exposure to arid and variable environments [2,135,136]. However, African populations remain underrepresented in current genomic datasets, and future sampling efforts should incorporate additional indigenous lineages to improve demographic resolution and capture the full spectrum of ancestral diversity. Mediterranean donkeys, particularly semi-feral or traditionally managed breeds such as Pantesco and Amiatina, exhibit moderate genetic diversity and clear population structuring shaped by regional selection on metabolism, morphology, and local environmental adaptation [50]. In contrast, intensively selected Chinese breeds, including Dezhou and Liangzhou, show reduced genomic diversity, extended runs of homozygosity, and strong selective sweeps targeting growth- and reproduction-related pathways, reflecting recent directional selection under modern breeding systems [26,33,123]. Recent studies integrating whole-genome resequencing with RNA-seq-based functional annotation further indicate that some breed-specific sweeps are driven by regulatory rather than coding variation, underscoring the value of integrative approaches for distinguishing adaptive signals from demographic effects [79,137]. Together, these patterns highlight that donkey genetic improvement and conservation strategies should be population-specific and context-sensitive rather than globally uniform [138]. For clarity, the principal advantages and practical constraints associated with different genomic approaches are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Advantages and constraints of applying genomic tools in donkeys.

7. Challenges, Limitations, and Ethical Considerations

7.1. Phenotypic Data Quality and Standardization

The utility of donkey genomics is constrained by fragmented datasets, variable sequencing quality, and inconsistent bioinformatic pipelines across studies [26,29,133,136]. Such technical heterogeneity limits cross-study comparability and reduces the accuracy and transferability of genomic predictions [146,147]. Donkey-specific features further exacerbate these challenges, as generally small and geographically isolated populations intensify genetic drift and inbreeding, thereby diminishing the statistical power of association analyses and genomic selection models [50,148,149].

In parallel, phenotypic data remain a major bottleneck. Measurements of growth, reproduction, and milk traits are frequently incomplete or non-standardized, with protocols differing widely across regions, management systems, and breeds [24,33,150]. This lack of harmonized phenotyping severely limits reliable genotype–phenotype integration and the downstream application of genomic tools [12,151]. Establishing shared reference populations, standardized phenotyping guidelines, and transparent data curation frameworks will be essential to improve reproducibility and analytical robustness.

7.2. Technical, Resource, and Policy Constraints

Progress in donkey genomics is often restricted by limited institutional capacity, insufficient funding, and uneven access to sequencing and computational infrastructure [32,120,152]. These constraints slow the expansion of population-scale genomics and multi-omics integration, particularly in regions where donkeys are most socioeconomically important.

Although international frameworks such as the Nagoya Protocol aim to promote ethical and equitable exchange of genetic resources, their implementation can create practical barriers to collaboration in low-resource settings. Complex permitting procedures, extended approval timelines, and administrative reporting requirements may delay or restrict material transfer and data sharing when local infrastructure and regulatory support are limited [153]. Targeted investment in regional genomic facilities, training programs, and interoperable open-access platforms will be critical to reduce these disparities and enable balanced global participation in donkey genomic research and conservation.

7.3. Ethical and Biosafety Considerations

Emerging biotechnologies, including genomic selection and genome editing, offer theoretical potential to improve disease resistance and reproductive performance in mammals [154,155,156]. However, their application in donkeys raises species-specific ethical and biosafety concerns. In endangered or locally adapted populations, genome editing may unintentionally disrupt population structure, accelerate inbreeding, or compromise adaptive traits shaped by long-term environmental and cultural selection [157,158].

Given the multifunctional roles of donkeys in transport, agriculture, and livelihoods, any welfare, behavioral, or metabolic consequences of genetic intervention must be carefully assessed [159]. Evidence from other livestock species—such as metabolic imbalances following MSTN knockout in pigs [160,161]—illustrates risks that would be unacceptable in small or vulnerable donkey populations. In addition, gene flow between edited donkeys and wild or semi-feral groups could threaten the genetic integrity of local ecotypes, particularly in regions where domestic and wild lineages coexist [26].

To mitigate these risks, future research should prioritize donkey-specific genomic resources, controlled in vitro functional validation, and conservation-oriented breeding frameworks [162]. Any application of advanced biotechnologies should proceed under transparent governance, strict welfare oversight, and long-term genetic monitoring to balance innovation with preservation.

8. Conclusions and Perspectives

Donkey genomics has made significant strides in recent years, producing chromosome-level reference genomes, population-scale resequencing datasets, and multi-omics analyses that offer valuable insights into the species’ evolutionary history, population structure, and the genetic underpinnings of important traits such as growth, reproduction, milk production, and environmental adaptation. Research has revealed that adaptive traits, such as thermotolerance and drought resilience, often evolve in conjunction with production traits, demonstrating the interconnected genetic basis of both fitness and performance. These findings highlight the complexity of donkey genetics and emphasize the need for a nuanced approach to breeding and conservation efforts.

While genomic tools have the potential to quickly influence donkey population structure, it is crucial to balance the maintenance of genetic diversity with the targeted enhancement of key traits. Research indicates that modulating gene expression at selected loci, while preserving effective population sizes, can improve both adaptive and production traits without causing significant loss of diversity. However, excessive directional selection in small or intensively managed populations risks depleting rare haplotypes and locally adapted alleles. To advance practical applications in breeding and conservation, future research should focus on expanding genomic datasets across diverse populations, implementing high-resolution phenotyping, validating candidate loci, and developing cost-effective genomic resources to support informed breeding programs and conservation strategies. This approach will help bridge theoretical genomics with applied practices to ensure sustainable improvements in donkey populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing—original draft, project administration: C.W., M.Z.K., Q.Z. and Y.P.; data curation, validation, writing—review and editing: C.W., M.Z.K., Q.Z., Y.J., M.G., X.Z., Y.Z., X.C. and Y.P.; resources and funding: C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Key R&D Program of Shandong Province (2025LZGC033), Liaocheng Municipal Bureau of Science and Technology, High-talented Foreign Expert Introduction Program (GDWZ202401), the National Key R&D Program of China (grant number 2023YFD1302004), the Shandong Province Modern Agricultural Technology System Donkey Industrial Innovation Team (grant no. SDAIT-27), the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2024MC213), the Horizontal Scientific Research Project of Liaocheng University (K25LD167), the Liaocheng University scientific research fund (318052339), the Livestock and Poultry Breeding Industry Project of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (grant number 19211162), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31671287).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data are available in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rossel, S.; Marshall, F.; Peters, J.; Pilgram, T.; Adams, M.D.; O’Connor, D. Domestication of the donkey: Timing, processes, and indicators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 3715–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, E.T.; Tonasso-Calvière, L.; Chauvey, L.; Schiavinato, S.; Fages, A.; Seguin-Orlando, A.; Clavel, P.; Khan, N.; Pérez Pardal, L.; Patterson Rosa, L. The genomic history and global expansion of domestic donkeys. Science 2022, 377, 1172–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, B.; Marshall, F.B.; Chen, S.; Rosenbom, S.; Moehlman, P.D.; Tuross, N.; Sabin, R.C.; Peters, J.; Barich, B.; Yohannes, H.; et al. Ancient DNA from nubian and somali wild ass provides insights into donkey ancestry and domestication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 278, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalcanti, N.S.H.; Pimentel, T.C.; Magnani, M.; Pacheco, M.T.B.; Alves, S.P.; Branquinho Bessa, R.J.; Marília Da Silva Sant’Ana, A.; de Cássia Ramos Do Egypto Queiroga, R. Donkey milk and fermented donkey milk: Are there differences in the nutritional value and physicochemical characteristics? Lwt 2021, 144, 111239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ren, W.; Peng, Y.; Khan, M.Z.; Liang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Kou, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Elucidating the Role of Transcriptomic Networks and DNA Methylation in Collagen Deposition of Dezhou Donkey Skin. Animals 2024, 14, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Peng, Y.; Liang, H.; Zahoor Khan, M.; Ren, W.; Huang, B.; Chen, Y.; Xing, S.; Zhan, Y.; Wang, C. Comprehensive transcriptomic analysis unveils the interplay of mRNA and LncRNA expression in shaping collagen organization and skin development in Dezhou donkeys. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1335591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, X.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, J.; Ullah, A.; Liu, Y.; Wei, J.; Khan, M.Z.; Wang, C. Morphometric and Histological Characterization of Chestnuts in Dezhou Donkeys and Associations with Phenotypic Traits. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sun, L.; Du, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ren, W.; Man, L.; Zhu, M.; Liu, G.; Khan, M.Z.; Wang, C. Characterization and discrimination of donkey milk lipids and volatiles across lactation stages. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Sun, L.; Du, X.; Ren, W.; Man, L.; Chai, W.; Zhu, M.; Liu, G.; Wang, C. Characterization of lipids and volatile compounds in boiled donkey meat by lipidomics and volatilomics. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 3445–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, D.; Chai, W.; Zhu, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Q.; Fan, D.; Lv, M.; Jiang, X.; et al. Chemical and physical properties of meat from Dezhou black donkey. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2022, 28, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, W.; Wang, L.; Li, T.; Wang, T.; Wang, X.; Yan, M.; Zhu, M.; Gao, J.; Wang, C.; Ma, Q.; et al. Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry-Based Metabolomics Reveals Dynamic Metabolite Changes during Early Postmortem Aging of Donkey Meat. Foods 2024, 13, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sheng, G.; Preick, M.; Hu, S.; Deng, T.; Taron, U.H.; Barlow, A.; Hu, J.; Xiao, B.; Sun, G. Ancient mitogenomes provide new insights into the origin and early introduction of Chinese domestic donkeys. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 759831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hua, X.; Shi, X.; Wang, C. Origin, evolution, and research development of donkeys. Genes 2022, 13, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camillo, F.; Rota, A.; Biagini, L.; Tesi, M.; Fanelli, D.; Panzani, D. The Current Situation and Trend of Donkey Industry in Europe. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2018, 65, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrum, F.; Theuri, S.; Mutua, E.; Carder, G. The Donkey Skin Trade: Challenges and Opportunities for Policy Change. Glob. Policy 2022, 13, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierini, C.; Landi, V.; Ciani, E.; Maggiolino, A.; Campanile, D.; Gomez Carpio, M.; De Palo, P. Conservation and genetic analysis of the endangered Martina Franca donkey using pedigree data. Front. Anim. Sci. 2025, 6, 1588467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordonaro, S.; Guastella, A.M.; Criscione, A.; Zuccaro, A.; Marletta, D. Genetic diversity and variability in endangered Pantesco and two other Sicilian donkey breeds assessed by microsatellite markers. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 648427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyiti, S.; Kelimu, A. Donkey Industry in China: Current Aspects, Suggestions and Future Challenges. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2021, 102, 103642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, M.; Altomonte, I.; Licitra, R.; Salari, F. Short communication: Technological and seasonal variations of vitamin D and other nutritional components in donkey milk. J. Dairy. Sci. 2018, 101, 8721–8725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, M.; Altomonte, I.; Licitra, R.; Salari, F. Nutritional and nutraceutical quality of donkey milk. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2018, 65, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, G.; Ji, C.; Fan, Z.; Ge, S.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Lv, X.; Zhao, F. Comparative whey proteome profiling of donkey milk with human and cow milk. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 911454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Liu, G.; Wang, C. A survey report on the donkey original breeding farms in China: Current aspects and future prospective. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1126138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, F.; Ciampolini, R.; Mariti, C.; Millanta, F.; Altomonte, I.; Licitra, R.; Auzino, B.; Ascenzi, C.D.; Bibbiani, C.; Giuliotti, L.; et al. A multi-approach study of the performance of dairy donkey during lactation: Preliminary results. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 18, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsad, R.; Bagiyal, M.; Ahlawat, S.; Arora, R.; Gera, R.; Chhabra, P.; Sharma, U. Unraveling the genetic and physiological potential of donkeys: Insights from genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics approaches. Mamm. Genome 2025, 36, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; Chen, W.; Wang, X.; Liang, H.; Wei, L.; Huang, B.; Kou, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Chai, W.; et al. A review of genetic resources and trends of omics applications in donkey research: Focus on China. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1366128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, H.; Guo, Y.; Huang, J.; Sun, Y.; Min, J.; Wang, J.; Fang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, S.; et al. Donkey genomes provide new insights into domestication and selection for coat color. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, G.; Petersen, B.; Seguin-Orlando, A.; Bertelsen, M.F.; Waller, A.; Newton, R.; Paillot, R.; Bryant, N.; Vaudin, M.; Librado, P.; et al. Improved de novo genomic assembly for the domestic donkey. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaaq0392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Bai, D.; Shiraigol, W.; Li, B.; Yang, L.; Wu, J.; Bao, W.; Ren, X.; Jin, B.; et al. Donkey genome and insight into the imprinting of fast karyotype evolution. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, F.; Scimone, C.; Geraci, C.; Schiavo, G.; Utzeri, V.J.; Chiofalo, V.; Fontanesi, L. Next generation semiconductor based sequencing of the donkey (Equus asinus) genome provided comparative sequence data against the horse genome and a few millions of single nucleotide polymorphisms. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Liu, H.-Q.; Tu, X.-L.; Ji, C.-M.; Gou, X.; Esmailizadeh, A.; Wang, S.; Wang, M.-S.; Wang, M.-C.; Li, X.-L.; et al. Genomes reveal selective sweeps in kiang and donkey for high-altitude adaptation. Zool. Res. 2021, 42, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Yu, J.; Dai, X.; Li, M.; Wang, G.; Chen, N.; Chen, H.; Lei, C.; Dang, R. Genomic analyses reveal distinct genetic architectures and selective pressures in chinese donkeys. J. Genet. Genom. 2021, 48, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAM, Y. African origins of modern asses as seen from paleontology and DNA: What about the Atlas wild ass? Geobios 2020, 58, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wang, S.; Li, N.; Chang, S.; Dai, S.; Guo, Y.; Wu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Zeng, S. Genome-wide association study to identify snps and candidate genes associated with body size traits in donkeys. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1112377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.-Q.; He, Y.-G.; Lin, X.-R.; Li, Y.; Yang, T.; Feng, M.; Zhang, H.-T.; Wang, X.-Y.; et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis of genetic diversity, body size, and origins of the hetian gray donkey. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Teng, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Jiang, X.; Ning, C.; Zhang, Q. Optimizing genomic selection in dezhou donkey using low coverage whole genome sequencing. Res. Sq 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Su, J.; Yang, Q.; Sun, M.; Wang, Z.; Yu, J.; Jafari, H.; Lei, C.; Sun, Y.; Dang, R. Genome-wide analyses based on a novel donkey 40K liquid chip reveal the gene responsible for coat color diversity in Chinese Dezhou donkey. Anim. Genet. 2024, 55, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Qian, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, C. Chromosome-Level Haplotype Assembly for Equus asinu. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 738105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Gong, M.; Yang, Q.; Li, Y.; Jafari, H.; Lei, C.; Jiang, Y.; Dang, R. Improved chromosome-level donkey (Equus asinus) genome provides insights into genome and chromosome evolution. J. Genet. Genom. 2025, 52, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jevit, M.J.; Castaneda, C.; Paria, N.; Das, P.J.; Miller, D.; Antczak, D.F.; Kalbfleisch, T.S.; Davis, B.W.; Raudsepp, T. Trio-binning of a hinny refines the comparative organization of the horse and donkey x chromosomes and reveals novel species-specific features. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Xiang, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; An, D.; Dong, J.; Zhao, C.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; et al. Long-read sequencing reveals genomic structural variations that underlie creation of quality protein maize. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, S.; Lam, E.; Saghbini, M.; Bocklandt, S.; Hastie, A.; Cao, H.; Holmlin, E.; Borodkin, M. Structural variation detection and analysis using bionano optical mapping. In Copy Number Variants: Methods and Protocols; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Cantalapiedra, J.L.; Prado, J.L.; Hernández Fernández, M.; Alberdi, M.T. Decoupled ecomorphological evolution and diversification in Neogene-Quaternary horses. Science 2017, 355, 627–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, B.; Bai, D.; Bou, G.; Zhang, X.; Du, M.; Wang, X.; Bou, T.; et al. Analysis of the whole-genome sequences from an equus parent-offspring trio provides insight into the genomic incompatibilities in the hybrid mule. Genes 2022, 13, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). EquAss-T2T_v2 (GCF_041296235.1): Equus asinus Telomere-to-Telomere Genome Assembly; NCBI: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/GCF_041296235.1 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Li, S.; Zhao, G.; Han, H.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Cao, G.; Li, X. Genome collinearity analysis illuminates the evolution of donkey chromosome 1 and horse chromosome 5 in perissodactyls: A comparative study. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Miao, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, C. Transcriptome Atlas of 16 Donkey Tissues. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 682734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, X.; Pei, C.; He, M.; Chu, M.; Guo, X.; Liang, C.; Bao, P.; Yan, P. Integrative analysis of Iso-Seq and RNA-seq data reveals transcriptome complexity and differential isoform in skin tissues of different hair length Yak. Bmc Genom. 2024, 25, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Bellone, R.; Petersen, J.L.; Kalbfleisch, T.S.; Finno, C.J. Successful atac-seq from snap-frozen equine tissues. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 641788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Zhai, X.; Zhang, J.; Jafari, H.; Ren, G.; Lei, C.; Dang, R.; et al. Whole-genome resequencing of 391 Chinese donkeys reveals a population structure and provides insights into their morphological and adaptive traits. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criscione, A.; Chessari, G.; Cesarani, A.; Ablondi, M.; Asti, V.; Bigi, D.; Bordonaro, S.; Ciampolini, R.; Cipolat-Gotet, C.; Congiu, M.; et al. Analysis of ddRAD-seq data provides new insights into the genomic structure and patterns of diversity in Italian donkey populations. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Dong, Z.; Wang, F.; Wang, G.; Luo, X.; Lei, C.; Chen, J. Whole genome sequencing provides new insights into the genetic diversity and coat color of asiatic wild ass and its hybrids. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 818420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbom, S.; Costa, V.; Al-Araimi, N.; Kefena, E.; Abdel-Moneim, A.S.; Abdalla, M.A.; Bakhiet, A.; Beja-Pereira, A. Genetic diversity of donkey populations from the putative centers of domestication. Anim. Genet. 2015, 46, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Khan, M.Z.; Chai, W.; Ullah, Q.; Wang, C. Exploring genetic markers: Mitochondrial DNA and genomic screening for biodiversity and production traits in donkeys. Animals 2023, 13, 2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Chen, N.; Jordana, J.; Li, C.; Sun, T.; Xia, X.; Zhao, X.; Ji, C.; Shen, S.; Yu, J.; et al. Genetic diversity and paternal origin of domestic donkeys. Anim. Genet. 2017, 48, 708–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beja-Pereira, A.; England, P.R.; Ferrand, N.; Jordan, S.; Bakhiet, A.O.; Abdalla, M.A.; Mashkour, M.; Jordana, J.; Taberlet, P.; Luikart, G. African Origins of the Domestic Donkey. Science 2004, 304, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhu, S.; Ning, C.; Cai, D.; Wang, K.; Chen, Q.; Hu, S.; Yang, J.; Shao, J.; Zhu, H.; et al. Ancient DNA provides new insight into the maternal lineages and domestication of Chinese donkeys. BMC Evol. Biol. 2014, 14, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Yu, J.; Zhao, X.; Yao, Y.; Zeng, L.; Ahmed, Z.; Shen, S.; Dang, R.; Lei, C. Genetic diversity and maternal origin of Northeast African and South American donkey populations. Anim. Genet. 2019, 50, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzatenta, A.; Vignoli, M.; Caputo, M.; Vignola, G.; Tamburro, R.; De Sanctis, F.; Roig, J.M.; Bucci, R.; Robbe, D.; Carluccio, A. Maternal Phylogenetic Relationships and Genetic Variation among Rare, Phenotypically Similar Donkey Breeds. Genes 2021, 12, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özkan Ünal, E.; Özdil, F.; Kaplan, S.; Gürcan, E.K.; Genç, S.; Arat, S.; Soysal, M.İ. Phylogenetic Relationships of Turkish Indigenous Donkey Populations Determined by Mitochondrial DNA D-loop Region. Animals 2020, 10, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanisic, L.J.; Aleksic, J.M.; Dimitrijevic, V.; Simeunovic, P.; Glavinic, U.; Stevanovic, J.; Stanimirovic, Z. New insights into the origin and the genetic status of the Balkan donkey from Serbia. Anim. Genet. 2017, 48, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.Y.; Zhou, F.; Xiao, H.; Sha, T.; Wu, S.F.; Zhang, Y.P. Mitochondrial DNA diversity and population structure of four Chinese donkey breeds. Anim. Genet. 2006, 37, 427–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Pardal, L.; Grizelj, J.; Traoré, A.; Cubric-Curik, V.; Arsenos, G.; Dovenski, T.; Marković, B.; Fernández, I.; Cuervo, M.; Álvarez, I.; et al. Lack of mitochondrial DNA structure in Balkan donkey is consistent with a quick spread of the species after domestication. Anim. Genet. 2014, 45, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzi, M.C.; Valiati, P.; Cherchi, R.; Gorla, E.; Prinsen, R.T.M.M.; Longeri, M.; Bagnato, A.; Strillacci, M.G. Mitochondrial DNA genetic diversity in six Italian donkey breeds (Equus asinus). Mitochondrial DNA Part A 2018, 29, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Zhao, C.; Wu, C. Genetic architectures and selection signatures of body height in Chinese indigenous donkeys revealed by next-generation sequencing. Anim. Genet. 2022, 53, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, F.; Pei, H.; Li, M.; Bai, F.; Lei, C.; Dang, R. Genome-wide analysis reveals selection signatures for body size and drought adaptation in liangzhou donkey. Genomics 2022, 114, 110476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y.; Wei, L.; Zhu, Q.; Khan, M.Z.; Wang, C. Potential genetic markers associated with environmental adaptability in herbivorous livestock. Animals 2025, 15, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, E.A.; Weber, J.; Bendhafer, W.; Champlot, S.; Peters, J.; Schwartz, G.M.; Grange, T.; Geigl, E. The genetic identity of the earliest human-made hybrid animals, the kungas of Syro-Mesopotamia. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm0218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambaldi Migliore, N.; Bigi, D.; Milanesi, M.; Zambonelli, P.; Negrini, R.; Morabito, S.; Verini-Supplizi, A.; Liotta, L.; Chegdani, F.; Agha, S.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA control-region and coding-region data highlight geographically structured diversity and post-domestication population dynamics in worldwide donkeys. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.-Y.; Ning, T.; Adeola, A.C.; Li, J.; Esmailizadeh, A.; Lichoti, J.K.; Agwanda, B.R.; Isakova, J.; Aldashev, A.A.; Wu, S.-F.; et al. Potential dual expansion of domesticated donkeys revealed by worldwide analysis on mitochondrial sequences. Zool. Res. 2020, 41, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugo, G.P.; Dover, M.J.; MacHugh, D.E. Unlocking the origins and biology of domestic animals using ancient DNA and paleogenomics. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fages, A.; Hanghøj, K.; Khan, N.; Gaunitz, C.; Seguin-Orlando, A.; Leonardi, M.; McCrory Constantz, C.; Gamba, C.; Al-Rasheid, K.A.S.; Albizuri, S.; et al. Tracking Five Millennia of Horse Management with Extensive Ancient Genome Time Series. Cell 2019, 177, 1419–1435.e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasinou, P.; De Amicis, I.; Fusaro, I.; Bucci, R.; Cavallini, D.; Parrillo, S.; Caputo, M.; Gramenzi, A.; Carluccio, A. The Lipidomics of Spermatozoa and Red Blood Cells Membrane Profile of Martina Franca Donkey: Preliminary Evaluation. Animals 2023, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; Chen, W.; Huang, B.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Chai, W.; Wang, C. Advancements in Genetic Marker Exploration for Livestock Vertebral Traits with a Focus on China. Animals 2024, 14, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.; Wu, F.; Li, M.; Bai, F.; Gao, Y.; Yu, J.; Li, H.; Lei, C.; Dang, R. Tissue expression profile, polymorphism of IGF1 gene and its effect on body size traits of Dezhou donkey. Gene 2021, 766, 145118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claeys, W.L.; Verraes, C.; Cardoen, S.; De Block, J.; Huyghebaert, A.; Raes, K.; Dewettinck, K.; Herman, L. Consumption of raw or heated milk from different species: An evaluation of the nutritional and potential health benefits. Food Control. 2014, 42, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, W.; Kou, X.; Liang, H.; Ren, W.; Khan, M.Z.; Wang, C. Coloration in Equine: Overview of Candidate Genes Associated with Coat Color Phenotypes. Animals 2024, 14, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polidori, P.; Cammertoni, N.; Santini, G.; Klimanova, Y.; Zhang, J.; Vincenzetti, S. Effects of Donkeys Rearing System on Performance Indices, Carcass, and Meat Quality. Foods 2021, 10, 3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhu, M.; Gong, Y.; Wang, C. Identification and functional prediction of lncRNAs associated with intramuscular lipid deposition in Guangling donkeys. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1410109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Fan, Y.; Wang, G.; Lai, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wu, F.; Lei, C.; Dang, R. Detection of Selection Signatures Underlying Production and Adaptive Traits Based on Whole-Genome Sequencing of Six Donkey Populations. Animals 2020, 10, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kefena, E.; Dessie, T.; Tegegne, A.; Beja-Pereira, A.; Kurtu, M.Y.; Rosenbom, S.; Han, J.L. Genetic diversity and matrilineal genetic signature of native Ethiopian donkeys (Equus asinus) inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequence polymorphism. Livest. Sci. 2014, 167, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Feng, M.; Zhao, C. A mutation in POLR2A gene associated with body size traits in Dezhou donkeys revealed with GWAS. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, B.; Chen, S.; Liu, W. A Genome-Wide Association Study of the Chest Circumference Trait in Xinjiang Donkeys Based on Whole-Genome Sequencing Technology. Genes 2023, 14, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auzino, B.; Miranda, G.; Henry, C.; Krupova, Z.; Martini, M.; Salari, F.; Cosenza, G.; Ciampolini, R.; Martin, P. Top-Down proteomics based on LC-MS combined with cDNA sequencing to characterize multiple proteoforms of Amiata donkey milk proteins. Food Res. Int. 2022, 160, 111611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosenza, G.; Ciampolini, R.; Iannaccone, M.; Gallo, D.; Auzino, B.; Pauciullo, A. Sequence variation and detection of a functional promoter polymorphism in the lysozyme c-type gene from Ragusano and Grigio Siciliano donkeys. Anim. Genet. 2018, 49, 270–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdil, F.; Bulut, H.; Işık, R. Genetic diversity of κ-casein (CSN3) and lactoferrin (LTF) genes in the endangered Turkish donkey (Equus asinus) populations. Arch. Anim. Breed. 2019, 62, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, C.; Farnir, F.; Liu, L.; Xiao, H. Unveiling Genetic Markers for Milk Yield in Xinjiang Donkeys: A Genome-Wide Association Study and Kompetitive Allele-Specific PCR-Based Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abitbol, M.; Legrand, R.; Tiret, L. A missense mutation in melanocortin 1 receptor is associated with the red coat colour in donkeys. Anim. Genet. 2014, 45, 878–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utzeri, V.J.; Bertolini, F.; Ribani, A.; Schiavo, G.; Dall’Olio, S.; Fontanesi, L. The albinism of the feral Asinara white donkeys (Equus asinus) is determined by a missense mutation in a highly conserved position of the tyrosinase (TYR) gene deduced protein. Anim. Genet. 2016, 47, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, B.; Rieder, S.; Leeb, T. Two variants in the KIT gene as candidate causative mutations for a dominant white and a white spotting phenotype in the donkey. Anim. Genet. 2015, 46, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J.; Shen, W. Comparative Transcriptomics Uncover the Uniqueness of Oocyte Development in the Donkey. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 839207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Song, X.; Yin, S.; Yan, J.; Lv, P.; Shan, H.; Cui, K.; Liu, H.; Liu, Q. Single-Cell RNA-Seq Revealed the Gene Expression Pattern during the In Vitro Maturation of Donkey Oocytes. Genes 2021, 12, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ake, A.S.; Ayo, J.O. Effects of melatonin on interleukins and heat stress protein responses in donkeys subjected to packing during the hot-dry season in the Northern Guinea Savanna zone of Nigeria. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2023, 32, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samie, K.A.; Kowalewski, M.P.; Schuler, G.; Gastal, G.D.A.; Bollwein, H.; Scarlet, D. Roles of GDF9 and BMP15 in equine follicular development: In vivo content and in vitro effects of IGF1 and cortisol on granulosa cells. BMC Vet. Res. 2025, 21, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Schenkel, F.S.; Melo, A.L.P.; Oliveira, H.R.; Pedrosa, V.B.; Araujo, A.C.; Melka, M.G.; Brito, L.F. Identifying pleiotropic variants and candidate genes for fertility and reproduction traits in Holstein cattle via association studies based on imputed whole-genome sequence genotypes. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, S.; Rafat, S.A.; Fang, L. Integrated TWAS, GWAS, and RNAseq results identify candidate genes associated with reproductive traits in cows. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, G.R.D.; Brito, L.F.; Mota, L.F.M.; Cyrillo, J.N.S.G.; Valente, J.P.S.; Benfica, L.F.; Silva Neto, J.B.; Borges, M.S.; Monteiro, F.M.; Faro, L.E.; et al. Genome-wide association studies and functional annotation of pre-weaning calf mortality and reproductive traits in Nellore cattle from experimental selection lines. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Bao, S.; Zhao, X.; Bai, Y.; Lv, Y.; Gao, P.; Li, F.; Zhang, W. Genome-Wide Association Study and Phenotype Prediction of Reproductive Traits in Large White Pigs. Animals 2024, 14, 3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živkov Baloš, M.; Ljubojević Pelić, D.; Jakšić, S.; Lazić, S. Donkey Milk: An Overview of its Chemical Composition and Main Nutritional Properties or Human Health Benefit Properties. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2023, 121, 104225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; Chen, W.; Li, M.; Ren, W.; Huang, B.; Kou, X.; Ullah, Q.; Wei, L.; Wang, T.; Khan, A.; et al. Is there sufficient evidence to support the health benefits of including donkey milk in the diet? Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1404998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Huang, F.; Du, X.; Liu, G.; Wang, C. Analysis of the Differentially Expressed Proteins in Donkey Milk in Different Lactation Stages. Foods 2023, 12, 4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luoyizha, W.; Zeng, B.; Li, H.; Liao, X. A Preliminary Study of Proteomic Analysis on Caseins and Whey Proteins in Donkey Milk from Xinjiang and Shandong of China. Efood 2021, 2, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosenza, G.; Pauciullo, A. A Comprehensive Analysis of CSN1S2 I and II Transcripts Reveals Significant Genetic Diversity and Allele-Specific Exon Skipping in Ragusana and Amiatina Donkeys. Animals 2024, 14, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gámez, E.; Gutiérrez-Gil, B.; Sahana, G.; Sánchez, J.; Bayón, Y.; Arranz, J. GWA Analysis for Milk Production Traits in Dairy Sheep and Genetic Support for a QTN Influencing Milk Protein Percentage in the LALBA Gene. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liu, L.; Chen, C.J.; Zhang, M.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, X.; Shi, Y. Genome-wide association study of milk and reproductive traits in dual-purpose Xinjiang Brown cattle. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kociszewska-Najman, B.; Borek-Dzieciol, B.; Szpotanska-Sikorska, M.; Wilkos, E.; Pietrzak, B.; Wielgos, M. The creamatocrit, fat and energy concentration in human milk produced by mothers of preterm and term infants. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012, 25, 1599–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios-Leyvraz, M.; Yao, Q. Calcium, zinc, and vitamin D in breast milk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2023, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malacarne, M.; Criscione, A.; Franceschi, P.; Bordonaro, S.; Formaggioni, P.; Marletta, D.; Summer, A. New Insights into Chemical and Mineral Composition of Donkey Milk throughout Nine Months of Lactation. Animals 2019, 9, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Ma, Z.; Du, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, G. The Milk Compositions and Blood Parameters of Lactating Dezhou Donkeys Changes With Lactation Stages. Vet. Med. Sci. 2025, 11, e70269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, C.M.; Ramachandra, C.T.; Nidoni, U.; Hiregoudar, S.; Ram, J.; Naik, N. Physico-chemical composition, minerals, vitamins, amino acids, fatty acid profile and sensory evaluation of donkey milk from Indian small grey breed. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 2967–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garhwal, R.; Bhardwaj, A.; Sangwan, K.; Mehra, R.; Pal, Y.; Nayan, V.; Iquebal, M.A.; Jaiswal, S.; Kumar, H. Milk from Halari Donkey Breed: Nutritional Analysis, Vitamins, Minerals, and Amino Acids Profiling. Foods 2023, 12, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, B. Nutritional and health benefits of donkey milk. J. Food Sci. Nutr. Ther. 2020, 6, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živkov-Baloš, M.; Popov, N.; Vidaković-Knežević, S.; Savić, S.; Gajdov, V.; Jakšić, S.; Ljubojević-Pelić, D. Nutritional quality of donkey milk during the lactation. Biotechnol. Anim. Husb. 2024, 40, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubojević Pelić, D.; Popov, N.; Gardić, E.; Vidaković Knežević, S.; Žekić, M.; Gajdov, V.; Živkov Baloš, M. Seasonal Variation in Essential Minerals, Trace Elements, and Potentially Toxic Elements in Donkey Milk from Banat and Balkan Breeds in the Zasavica Nature Reserve. Animals 2025, 15, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Dahlgren, A.R.; Donnelly, C.G.; Hales, E.N.; Petersen, J.L.; Bellone, R.R.; Kalbfleisch, T.; Finno, C.J. Functional annotation of the animal genomes: An integrated annotation resource for the horse. PLoS Genet. 2023, 19, e1010468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, W.; Gao, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; et al. Comprehensive multi-omics characterization of different cuts of Dezhou donkey meat. Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2025, 11, 100267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzon-Arteaga, C.; Snyder, M.D.; Lazzarotto, C.R.; Moreno, N.F.; Juras, R.; Raudsepp, T.; Golding, M.C.; Varner, D.D.; Long, C.R. Efficient correction of a deleterious point mutation in primary horse fibroblasts with CRISPR-Cas9. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Fei, Y.; Shao, Y.; Liao, Q.; Meng, Q.; Chen, R.; Deng, L. Transcriptome analysis reveals immune function-related mRNA expression in donkey mammary glands during four developmental stages. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genom. Proteom. 2024, 49, 101169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Zhang, F.; Ma, R.; Xing, J.; Wang, M.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, G. Single-cell RNA sequencing unveils dynamic transcriptional profiles during the process of donkey spermatogenesis and maturation. Genomics 2025, 117, 110974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecocci, S.; Pietrucci, D.; Milanesi, M.; Pascucci, L.; Filippi, S.; Rosato, V.; Chillemi, G.; Capomaccio, S.; Cappelli, K. Transcriptomic Characterization of Cow, Donkey and Goat Milk Extracellular Vesicles Reveals Their Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, Y.; Gai, Y.; Liao, Q.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Li, B.; Bai, M.; Li, N.; Deng, L. An Integrated Analysis of Lactation-Related miRNA and mRNA Expression Profiles in Donkey Mammary Glands. Genes 2022, 13, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zeng, H.; Teng, J.; Ding, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z. Integrating eQTL and genome-wide association studies to uncover additive and dominant regulatory circuits in pig uterine capacity. Animal 2025, 19, 101599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Deng, B.; Zhu, M.; Wang, Y.; Yan, C.; Wang, T.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Ding, Y.; Jin, G. Integration of GWAS and eQTL Analysis to Identify Risk Loci and Susceptibility Genes for Gastric Cancer. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Teng, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Jiang, X.; Li, H.; Ning, C.; Zhang, Q. Towards a Cost-Effective Implementation of Genomic Prediction Based on Low Coverage Whole Genome Sequencing in Dezhou Donkey. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 728764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Zhang, S.; Shen, W.; Zhang, G.; Guo, R.; Zhang, W.; Cao, Y.; Pan, Q.; Liu, F.; Sun, Y.; et al. Identification of Candidate Genes for Twinning Births in Dezhou Donkeys by Detecting Signatures of Selection in Genomic Data. Genes 2022, 13, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 29392-2022; Quality Grading of Livestock and Poultry Meat—Beef. Standardization Administration of China and State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Tetens, J.; Widmann, P.; Kühn, C.; Thaller, G. A genome-wide association study indicates LCORL/NCAPG as a candidate locus for withers height in German Warmblood horses. Anim. Genet. 2013, 44, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallick, H.; Rahnavard, A.; McIver, L.J.; Ma, S.; Zhang, Y.; Nguyen, L.H.; Tickle, T.L.; Weingart, G.; Ren, B.; Schwager, E.H.; et al. Multivariable association discovery in population-scale meta-omics studies. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1009442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zanotelli, V.R.T.; Howald, C.; Chammartin, N.; Kolpakov, I.; Xenarios, I.; Froese, D.S.; Wollscheid, B.; Pedrioli, P.G.A.; Goetze, S. A Multi-Omics Framework for Decoding Disease Mechanisms: Insights From Methylmalonic Aciduria. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2025, 24, 100998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Dong, L.; Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zeng, X. Summary data-based Mendelian randomization and single-cell RNA sequencing analyses identify immune associations with low-level LGALS9 in sepsis. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, L.; Heise, J.; Liu, Z.; Bennewitz, J.; Thaller, G.; Tetens, J. Mendelian randomisation to uncover causal associations between conformation, metabolism, and production as potential exposure to reproduction in German Holstein dairy cattle. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2025, 57, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosse, M.; van Loon, S. Challenges in quantifying genome erosion for conservation. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 960958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellmann, R. Selection index theory for populations under directional and stabilizing selection. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2023, 55, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustefa, A.; Assefa, A.; Misganaw, M.; Getachew, F.; Abegaz, S.; Hailu, A.; Emshaw, Y. Phenotypic characterization of donkeys in Benishangul Gumuz. Online J. Anim. Feed. Res. 2020, 10, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Fusaro, I.; Parrillo, S.; Buonaiuto, G.; Prasinou, P.; Gramenzi, A.; Bucci, R.; Cavallini, D.; Carosi, A.; Carluccio, A.; De Amicis, I. Effects of hemp-based polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation on membrane lipid profiles and reproductive performance in Martina Franca jacks. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1553218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefena, E.; Rosenbom, S.; Beja-Pereira, A.; Kurtu, M.Y.; Han, J.L.; Dessie, T. Genetic diversity and population genetic structure in native Ethiopian donkeys (Equus asinus) inferred from equine microsatellite markers. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 53, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getachew, T.B.; Kassa, A.H.; Megersa, A.G. Phenotypic characterization of donkey population in South Omo Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Qiu, L.; Guan, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, J.; Du, M. Comparative transcriptome analysis of longissimus dorsi tissues with different intramuscular fat contents from Guangling donkeys. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Marle-Köster, E.; Lashmar, S.F.; Retief, A.; Visser, C. Whole-Genome SNP Characterisation Provides Insight for Sustainable Use of Local South African Livestock Populations. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 714194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Han, J.; Chang, T.; Jafari, H.; Yang, Q.; Guo, J.; Lei, C.; Dang, R. Whole-genome analysis reveals genetic diversity and selection pressure in Sichuan donkey. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, V.; Ceccobelli, S.; Bruno, S.; Pierini, C.; Campanile, D.; Ciani, E.; De Palo, P. Insights into pedigree- and genome-based inbreeding patterns in Martina Franca donkey breed. Animal 2025, 19, 101652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.A.A.; Harder, A.M.; Kirksey, K.B.; Mathur, S.; Willoughby, J.R. Detectability of runs of homozygosity is influenced by analysis parameters and population-specific demographic history. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2024, 20, e1012566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatkar, M.S.; Moser, G.; Hayes, B.J.; Raadsma, H.W. Strategies and utility of imputed SNP genotypes for genomic analysis in dairy cattle. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, T.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, X.; Guo, J.; Ge, W.; Liu, S.; Sun, Y.; et al. The Transcriptomic Signature of Donkey Ovarian Tissue Revealed by Cross-Species Comparative Analysis at Single-Cell Resolution. Animals 2025, 15, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, W.; Qu, H.; Ma, Q.; Zhu, M.; Li, M.; Zhan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xu, J.; Yao, H.; Li, Z.; et al. RNA-seq analysis identifies differentially expressed gene in different types of donkey skeletal muscles. Anim. Biotechnol. 2023, 34, 1786–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambini, A.; Smith, J.M.; Gurkin, R.J.; Palacios, P.D. Current and Emerging Advanced Techniques for Breeding Donkeys and Mules. Animals 2025, 15, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maswana, M.; Mugwabana, T.J.; Tyasi, T.L. Evaluation of breeding practices and morphological characterization of donkeys in Blouberg Local Municipality, Limpopo province: Implication for the design of community-based breeding programme. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0278400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Park, J.; Coffey, S.R.; Russo, A.; Hsu, I.; Wang, J.; Su, C.; Chang, R.; Lam, T.T.; Gopal, P.P.; et al. Single-cell transcriptomic and proteomic analysis of Parkinson’s disease brains. Sci. Transl. Med. 2024, 16, eabo1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Gong, S.; Tulafu, H.; Zhang, R.; Tao, W.; Adili, A.; Liu, L.; Wu, W.; Huang, J. Analysis of the Genetic Relationship and Inbreeding Coefficient of the Hetian Qing Donkey through a Simplified Genome Sequencing Technology. Genes 2024, 15, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, S.; Dong, J.; Cao, Y.; Sun, Y. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and indels identified from whole-genome re-sequencing of four Chinese donkey breeds. Anim. Biotechnol. 2023, 34, 1828–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, B.; Xiao, H.; Liu, W. Study on lactation performance and development of KASP marker for milk traits in Xinjiang donkey (Equus asinus). Anim. Biotechnol. 2023, 34, 2724–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gichure, M.; Onono, J.; Wahome, R.; Gathura, P. Assessment of Phenotypic Characteristics and Work Suitability for Working Donkeys in the Central Highlands in Kenya. Vet. Med. Int. 2020, 2020, 8816983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, H.; Guo, K.; Zhong, Z.; Teng, J.; Xu, Z.; Wei, C.; Shi, S.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, Y. Benchmarking 24 combinations of genotype pre-phasing and imputation software for SNP arrays in pigs. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, J.; Riddle, K.; Hudson, M.; Anderson, J.; Kusabs, N.; Coltman, T. Benefit sharing: Why inclusive provenance metadata matter. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1014044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuellar, C.J.; Amaral, T.F.; Rodriguez-Villamil, P.; Ongaratto, F.; Martinez, D.O.; Labrecque, R.; Losano, J.D.D.A.; Estrada-Cortés, E.; Bostrom, J.R.; Martins, K.; et al. Consequences of gene editing of PRLR on thermotolerance, growth, and male reproduction in cattle. FASEB Bioadv 2024, 6, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Lin, J.; Huang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Cao, C.; Hambly, C.; Qin, G.; Yao, J.; et al. Reconstitution of UCP1 using CRISPR/Cas9 in the white adipose tissue of pigs decreases fat deposition and improves thermogenic capacity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E9474–E9482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monod, A.; Koch, C.; Jindra, C.; Haspeslagh, M.; Howald, D.; Wenker, C.; Gerber, V.; Rottenberg, S.; Hahn, K. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Targeting of BPV-1-Transformed Primary Equine Sarcoid Fibroblasts. Viruses 2023, 15, 1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, G.B.; Korkuć, P.; Arends, D.; Wolf, M.J.; May, K.; König, S.; Brockmann, G.A. Genomic diversity and relationship analyses of endangered German Black Pied cattle (DSN) to 68 other taurine breeds based on whole-genome sequencing. Front. Genet. 2023, 13, 993959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, C.; Chen, J.; Bai, Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y.; Fang, M. Genome-Wide Analysis Reveals Human-Mediated Introgression from Western Pigs to Indigenous Chinese Breeds. Genes 2020, 11, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesfaye, S.; Deressa, B.; Teshome, E. Study on the Health and Welfare of Working Donkeys in Mirab Abaya District, Southern Ethiopia. Acad. J. Anim. Dis. 2016, 5, 40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, Y.; Song, Y.; Feng, Z.; Li, H.; Mu, Y.; Rehman, S.U.; Liu, Q.; Li, K. Myostatin Alteration in Pigs Enhances the Deposition of Long-Chain Unsaturated Fatty Acids in Subcutaneous Fat. Foods 2022, 11, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Xiao, W.; Qin, X.; Cai, G.; Chen, H.; Hua, Z.; Cheng, C.; Li, X.; Hua, W.; Xiao, H.; et al. Myostatin regulates fatty acid desaturation and fat deposition through MEF2C/miR222/SCD5 cascade in pigs. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Khan, M.Z.; Peng, Y.; Wang, C. A Comparative Review of Donkey Genetic Resources, Production Traits, and Industrial Utilization: Perspectives from China and Globally. Animals 2025, 15, 3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.