Ensemble Species Distribution Modeling of Climate Change Impacts on Endangered Amphibians and Reptiles in South Korea

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

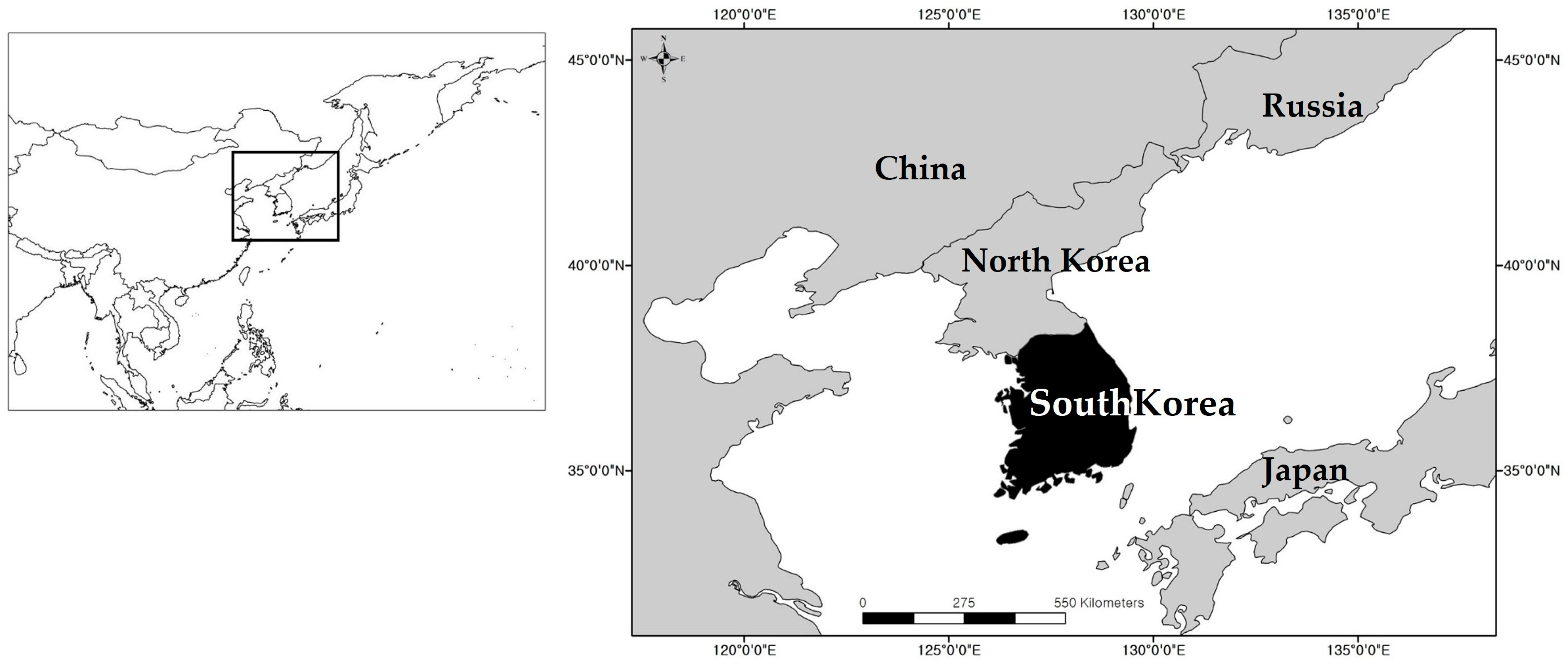

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Target Species

2.3. Species Occurrence Data

2.4. Environmental Variables

| Category | Variable Name | Code | Unit | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioclimatic | Annual Mean Temperature | BIO1 | °C | KMA |

| Bioclimatic | Mean Diurnal Range | BIO2 | °C | KMA |

| Bioclimatic | Isothermality | BIO3 | % | KMA |

| Bioclimatic | Annual Precipitation | BIO12 | mm | KMA |

| Bioclimatic | Precipitation of Wettest Month | BIO13 | mm | KMA |

| Bioclimatic | Precipitation of Driest Month | BIO14 | mm | KMA |

| Topographic | Elevation | elevation | m | National Geographic Information Institute |

| Topographic | Slope | slope | degrees | National Geographic Information Institute |

| Topographic | Topographic Wetness Index | wetness | - | Calculated from DEM |

| Hydrological | Distance to Water | dist_water | km | Ministry of Environment (WAMIS) |

2.5. Species Distribution Modeling

2.5.1. Modeling Approaches

2.5.2. Model Calibration and Validation

2.5.3. Variable Importance Analysis

2.5.4. Ensemble Modeling

2.6. Habitat Suitability and Future Projections

2.6.1. Current Habitat Suitability Mapping

2.6.2. Future Climate Scenarios

2.6.3. Model Projection and Species Richness Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance and Validation

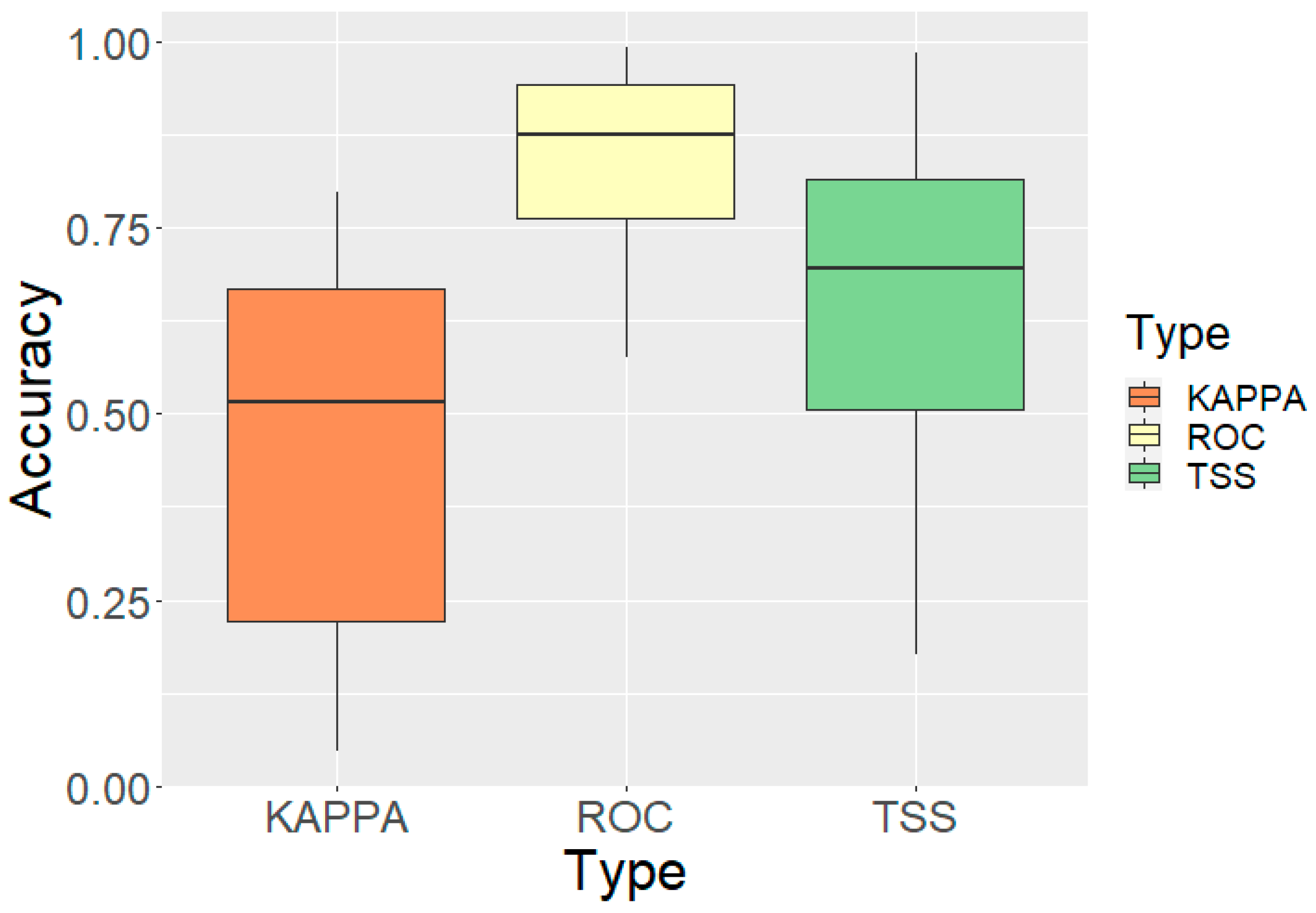

3.1.1. Overall Model Accuracy

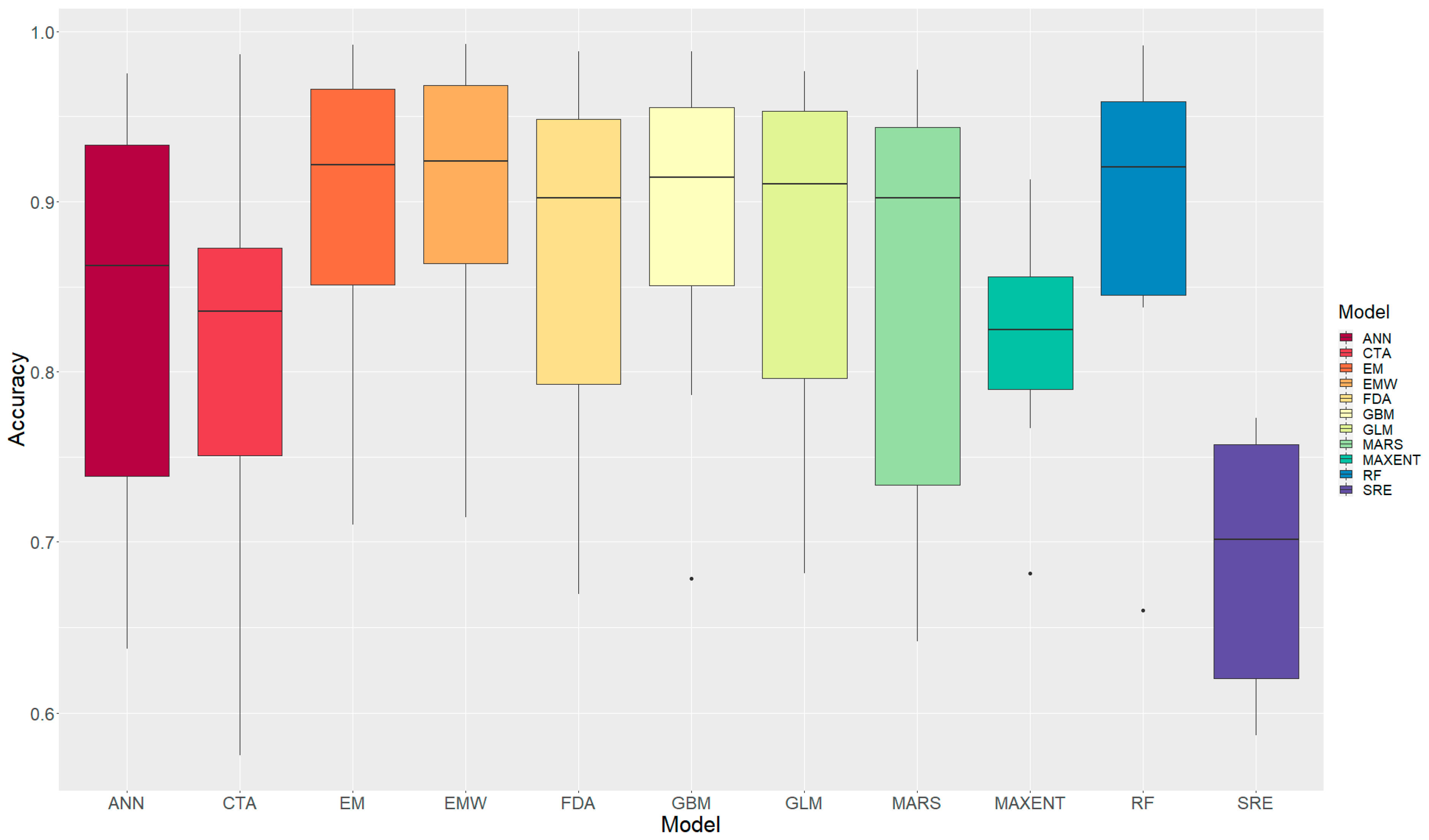

3.1.2. Model Performance Comparison

3.1.3. Species-Specific Model Performance

3.1.4. Model Consensus by Species

3.2. Environmental Variable Importance

3.2.1. Variable Contribution by Species

3.2.2. Variable Importance Ranking

3.2.3. Taxonomic Patterns in Variable Contribution

3.2.4. Variable Redundancy and Interaction Effects

3.3. Environmental Niche Characteristics

3.3.1. Niche Breadth Analysis

3.3.2. Species Similarity in Environmental Preferences

3.3.3. Climate Vulnerability and Conservation Prioritization

3.4. Species Richness Patterns Under Current and Future Climates

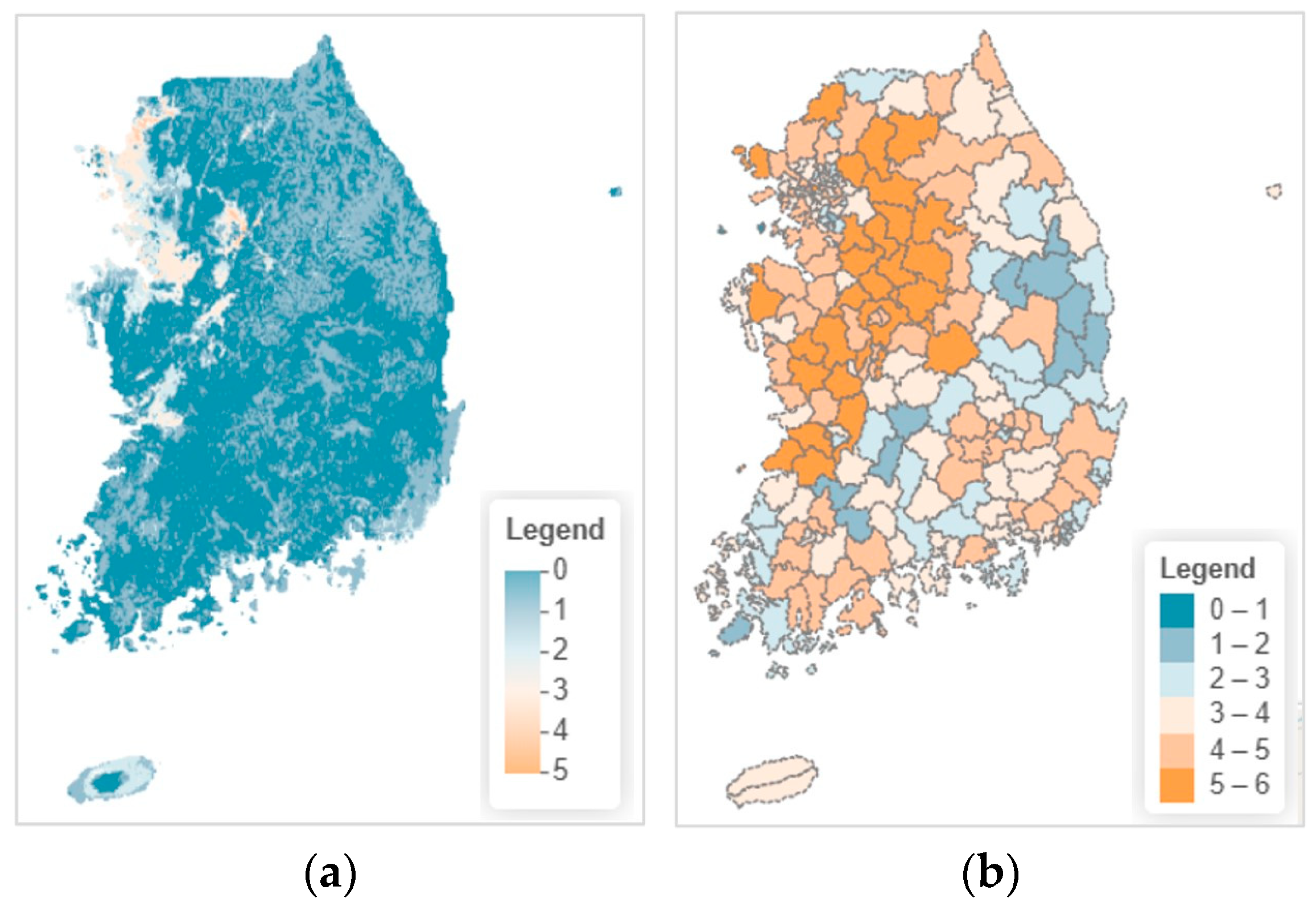

3.4.1. Current Species Richness Distribution

3.4.2. Projected Changes Under Climate Scenarios

4. Discussion

4.1. Model Performance and Methodological Implications

4.2. Environmental Determinants of Species Distribution

4.2.1. Taxonomic Differences in Environmental Requirements

4.2.2. Species-Specific Ecological Implications

4.3. Niche Breadth and Conservation Strategies

4.4. Species Associations and Community Dynamics

4.5. Variable Redundancy and Model Optimization

4.6. Climate Change Vulnerability and Conservation Implications

4.6.1. Species-Specific Vulnerabilities

4.6.2. Future Projections and Adaptive Conservation

4.7. Study Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| TSS | True Skill Statistic |

| SDM | Species distribution model |

References

- Parmesan, C. Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2006, 37, 637–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellard, C.; Bertelsmeier, C.; Leadley, P.; Thuiller, W.; Courchamp, F. Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, C.; Alexander, M.A. Climate change and amphibian declines: Is there a link? Divers. Distrib. 2003, 9, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaustein, A.R.; Han, B.A.; Relyea, R.A.; Johnson, P.T.J.; Buck, J.C.; Gervasi, S.S.; Kats, L.B. The complexity of amphibian population declines: Understanding the role of cofactors in driving amphibian losses. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1223, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huey, R.B.; Kearney, M.R.; Krockenberger, A.; Holtum, J.A.M.; Jess, M.; Williams, S.E. Predicting organismal vulnerability to climate warming: Roles of behaviour, physiology and adaptation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2012, 367, 1665–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinervo, B.; Mendez-de-la-Cruz, F.; Miles, D.B.; Heulin, B.; Bastiaans, E.; Villagrán-Santa Cruz, M.; Lara-Resendiz, R.; Martínez-Méndez, N.; Calderón-Espinosa, M.L.; Meza-Lázaro, R.N.; et al. Erosion of lizard diversity by climate change and altered thermal niches. Science 2010, 328, 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2023-1. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Stuart, S.N.; Chanson, J.S.; Cox, N.A.; Young, B.E.; Rodrigues, A.S.L.; Fischman, D.L.; Waller, R.W. Status and trends of amphibian declines and extinctions worldwide. Science 2004, 306, 1783–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Meteorological Administration. Korean Climate Change Assessment Report 2020; Korea Meteorological Administration: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2020.

- Park, D.; Cheong, S.; Sung, H.C. Morphological characterization and classification of anuran tadpoles in Korea. J. Ecol. Environ. 2006, 29, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Hahm, E.H.; Lee, H.J.; Park, S.; Won, Y.J.; Choe, J.C. Geographic variation in advertisement calls in a tree frog species: Gene flow and selection hypotheses. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Ecology. Status of Endangered Wildlife in Korea 2021; National Institute of Ecology: Seocheon, Republic of Korea, 2021.

- Guisan, A.; Thuiller, W. Predicting species distribution: Offering more than simple habitat models. Ecol. Lett. 2005, 8, 993–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elith, J.; Leathwick, J.R. Species distribution models: Ecological explanation and prediction across space and time. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2009, 40, 677–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.B.; New, M. Ensemble forecasting of species distributions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuiller, W.; Lafourcade, B.; Engler, R.; Araújo, M.B. BIOMOD—A platform for ensemble forecasting of species distributions. Ecography 2009, 32, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, P.J. Endocrines and Osmoregulation: A Comparative Account in Vertebrates, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2002; ISBN 978-3-662-05014-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, K.D. The Ecology and Behavior of Amphibians; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-226-89334-1. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell, R.K.; Futuyma, D.J. On the measurement of niche breadth and overlap. Ecology 1971, 52, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devictor, V.; Clavel, J.; Julliard, R.; Lavergne, S.; Mouillot, D.; Thuiller, W.; Venail, P.; Villéger, S.; Mouquet, N. Defining and measuring ecological specialization. J. Appl. Ecol. 2010, 47, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julliard, R.; Clavel, J.; Devictor, V.; Jiguet, F.; Couvet, D. Spatial segregation of specialists and generalists in bird communities. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 1237–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clavel, J.; Julliard, R.; Devictor, V. Worldwide decline of specialist species: Toward a global functional homogenization? Front. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 9, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margules, C.R.; Pressey, R.L. Systematic conservation planning. Nature 2000, 405, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, P.H.; Araújo, M.B. Apples, oranges, and probabilities: Integrating multiple factors into biodiversity conservation with consistency. Environ. Model. Assess. 2002, 7, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, B.J.; Duffy, J.E.; Gonzalez, A.; Hooper, D.U.; Perrings, C.; Venail, P.; Narwani, A.; Mace, G.M.; Tilman, D.; Wardle, D.A.; et al. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 2012, 486, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.A.; Carwardine, J.; Possingham, H.P. Setting conservation priorities. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1162, 237–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, B.C.; Kriegler, E.; Ebi, K.L.; Kemp-Benedict, E.; Riahi, K.; Rothman, D.S.; van Ruijven, B.J.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Birkmann, J.; Kok, K.; et al. The roads ahead: Narratives for shared socioeconomic pathways describing world futures in the 21st century. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 42, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, K.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Kriegler, E.; Edmonds, J.; O’Neill, B.C.; Fujimori, S.; Bauer, N.; Calvin, K.; Dellink, R.; Fricko, O.; et al. The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: An overview. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 42, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebaldi, C.; Debeire, K.; Eyring, V.; Fischer, E.; Fyfe, J.; Friedlingstein, P.; Knutti, R.; Lowe, J.; O’Neill, B.; Sanderson, B.; et al. Climate model projections from the Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) of CMIP6. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2021, 12, 253–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guisan, A.; Rahbek, C. SESAM—A new framework integrating macroecological and species distribution models for predicting spatio-temporal patterns of species assemblages. J. Biogeogr. 2011, 38, 1433–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuiller, W.; Guéguen, M.; Renaud, J.; Karger, D.N.; Zimmermann, N.E. Uncertainty in ensembles of global biodiversity scenarios. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Kim, J.-H.; Dang, J.-H.; Seo, I.-S.; Lee, B.Y. Elevational distribution ranges of vascular plant species in the Baekdudaegan mountain range, South Korea. J. Ecol. Environ. 2021, 45, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environment. Endangered Wild Species List (Revised in 2022); Ministry of Environment: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2022. (In Korean)

- NGA.STND.0036_1.0.0_WGS84, Version 1.0.0. Department of Defense World Geodetic System 1984. National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency: Arnold, MO, USA, 2014.

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, O.; Bechtel, B.; Bock, M.; Dietrich, H.; Fischer, E.; Gerlitz, L.; Wehberg, J.; Wichmann, V.; Böhner, J. System for Automated Geoscientific Analyses (SAGA) v. 2.1.4. Geosci. Model Dev. 2015, 8, 1991–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormann, C.F.; Elith, J.; Bacher, S.; Buchmann, C.; Carl, G.; Carré, G.; Marquéz, J.R.G.; Gruber, B.; Lafourcade, B.; Leitão, P.J.; et al. Collinearity: A review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography 2013, 36, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuiller, W.; Georges, D.; Gueguen, M.; Engler, R.; Breiner, F. biomod2: Ensemble Platform for Species Distribution Modeling. R Package Version 4.2-3. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=biomod2 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Korea Meteorological Administration. Climate Change Scenarios for IPCC AR6 SSP Scenarios: 1 km Resolution Data for South Korea; Korea Meteorological Administration: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024.

- Ministry of Land; Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT); National Geographic Information Institute (NGII). DEM (Digital Elevation Model) Dataset (File Data). Public Data Portal, Republic of Korea. Available online: https://www.data.go.kr/data/15059920/fileData.do (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Ministry of Environment (MOE); Water Management Information System (WAMIS). Available online: https://www.wamis.go.kr/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- McCullagh, P.; Nelder, J.A. Generalized Linear Models, 2nd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: London, UK, 1989; ISBN 978-0-412-31760-6. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Schapire, R.E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model. 2006, 190, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elith, J.; Leathwick, J.R.; Hastie, T. A working guide to boosted regression trees. J. Anim. Ecol. 2008, 77, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouche, O.; Tsoar, A.; Kadmon, R. Assessing the accuracy of species distribution models: Prevalence, kappa and the true skill statistic (TSS). J. Appl. Ecol. 2006, 43, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, A.H.; Bell, J.F. A review of methods for the assessment of prediction errors in conservation presence/absence models. Environ. Conserv. 1997, 24, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmion, M.; Parviainen, M.; Luoto, M.; Heikkinen, R.K.; Thuiller, W. Evaluation of consensus methods in predictive species distribution modelling. Divers. Distrib. 2009, 15, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; White, M.; Newell, G. Selecting thresholds for the prediction of species occurrence with presence-only data. J. Biogeogr. 2013, 40, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, R.J. Raster: Geographic Data Analysis and Modeling. R Package Version 3.6-23. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=raster (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Araújo, M.B.; Peterson, A.T. Uses and misuses of bioclimatic envelope modeling. Ecology 2012, 93, 1527–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elith, J.; Kearney, M.; Phillips, S. The art of modelling range-shifting species. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2010, 1, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Labs Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spellerberg, I.F.; Fedor, P.J. A tribute to Claude Shannon (1916–2001) and a plea for more rigorous use of species richness, species diversity and the ‘Shannon-Wiener’ Index. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2003, 12, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, B.L. The generalization of “Student’s” problem when several different population variances are involved. Biometrika 1947, 34, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubbs, F.E. Procedures for detecting outlying observations in samples. Technometrics 1969, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.H. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokal, R.R.; Rohlf, F.J. The comparison of dendrograms by objective methods. Taxon 1962, 11, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2.6-4. 2022. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Hao, T.; Elith, J.; Guillera-Arroita, G.; Lahoz-Monfort, J.J. A review of evidence about use and performance of species distribution modelling ensembles like BIOMOD. Divers. Distrib. 2019, 25, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elith, J.; Graham, C.H.; Anderson, R.P.; Dudík, M.; Ferrier, S.; Guisan, A.; Hijmans, R.J.; Huettmann, F.; Leathwick, J.R.; Lehmann, A.; et al. Novel methods improve prediction of species’ distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 2006, 29, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbet-Massin, M.; Jiguet, F.; Albert, C.H.; Thuiller, W. Selecting pseudo-absences for species distribution models: How, where and how many? Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012, 3, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buisson, L.; Thuiller, W.; Casajus, N.; Lek, S.; Grenouillet, G. Uncertainty in ensemble forecasting of species distribution. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 1145–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuiller, W.; Brotons, L.; Araújo, M.B.; Lavorel, S. Effects of restricting environmental range of data to project current and future species distributions. Ecography 2004, 27, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huey, R.B.; Deutsch, C.A.; Tewksbury, J.J.; Vitt, L.J.; Hertz, P.E.; Álvarez Pérez, H.J.; Garland, T. Why tropical forest lizards are vulnerable to climate warming. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 276, 1939–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.I.; Song, J.Y. Conservation status and ecological characteristics of Sibynophis chinensis (Günther, 1889) in Korea. Korean J. Environ. Ecol. 2020, 34, 298–305. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.S.; Yoon, I.B. Herpetofauna of Korea; National Institute of Biological Resources: Incheon, Republic of Korea, 2011; ISBN 978-89-94555-11-1. [Google Scholar]

- VanDerWal, J.; Murphy, H.T.; Kutt, A.S.; Perkins, G.C.; Bateman, B.L.; Perry, J.J.; Reside, A.E. Focus on poleward shifts in species’ distribution underestimates the fingerprint of climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Park, D. The effects of tadpole size and density on growth and survival of Kaloula borealis. Korean J. Herpetol. 2009, 1, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ra, N.Y.; Sung, H.C.; Cheong, S.; Lee, J.H.; Eom, J.; Park, D. Habitat use and home range of the endangered Kaloula borealis. Korean J. Herpetol. 2013, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, Y.H.; Karraker, N.E.; Hau, B.C.H. Demographic evidence of illegal harvesting of an endangered Asian turtle. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 27, 1421–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.D.; Cameron, A.; Green, R.E.; Bakkenes, M.; Beaumont, L.J.; Collingham, Y.C.; Erasmus, B.F.N.; de Siqueira, M.F.; Grainger, A.; Hannah, L.; et al. Extinction risk from climate change. Nature 2004, 427, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufresnes, C.; Borzée, A.; Horn, A.; Stöck, M.; Ostini, M.; Sermier, R.; Washietl, M.; Kolenda, K.; Safarek, G.; Ilgaz, Ç.; et al. Phylogeography of Hyla orientalis (Anura, Hylidae): A European tree frog with Asiatic roots. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2019, 130, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slatyer, R.A.; Hirst, M.; Sexton, J.P. Niche breadth predicts geographical range size: A general ecological pattern. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 1104–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.; Koo, K.S.; Jang, H.J. Population genetic structure and conservation implications of the endangered treefrog Hyla suweonensis. Anim. Cells Syst. 2017, 21, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrig, L.; Baudry, J.; Brotons, L.; Burel, F.G.; Crist, T.O.; Fuller, R.J.; Sirami, C.; Siriwardena, G.M.; Martin, J.L. Functional landscape heterogeneity and animal biodiversity in agricultural landscapes. Ecol. Lett. 2011, 14, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, R.J.; Cameron, S.E.; Parra, J.L.; Jones, P.G.; Jarvis, A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2005, 25, 1965–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D.R.; Edwards, T.C.; Beard, K.H.; Cutler, A.; Hess, K.T.; Gibson, J.; Lawler, J.J. Random forests for classification in ecology. Ecology 2007, 88, 2783–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMenamin, S.K.; Hadly, E.A.; Wright, C.K. Climatic change and wetland desiccation cause amphibian decline in Yellowstone National Park. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 16988–16993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheele, B.C.; Foster, C.N.; Banks, S.C.; Lindenmayer, D.B. Niche contractions in declining species: Mechanisms and consequences. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2017, 32, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.A.; Evans, J.S.; Storfer, A. Quantifying Bufo boreas connectivity in Yellowstone National Park with landscape genetics. Ecology 2010, 91, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradervand, J.N.; Dubuis, A.; Pellissier, L.; Guisan, A.; Randin, C. Very high resolution environmental predictors in species distribution models: Moving beyond topography? Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2014, 38, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021.

- Chen, I.C.; Hill, J.K.; Ohlemüller, R.; Roy, D.B.; Thomas, C.D. Rapid range shifts of species associated with high levels of climate warming. Science 2011, 333, 1024–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunday, J.M.; Bates, A.E.; Dulvy, N.K. Thermal tolerance and the global redistribution of animals. Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.G.; Cho, D.G. Status and ecological resource value of the Republic of Korea’s De-militarized Zone. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2005, 1, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimm, S.L.; Jenkins, C.N.; Abell, R.; Brooks, T.M.; Gittleman, J.L.; Joppa, L.N.; Raven, P.H.; Roberts, C.M.; Sexton, J.O. The biodiversity of species and their rates of extinction, distribution, and protection. Science 2014, 344, 1246752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekercioglu, C.H.; Schneider, S.H.; Fay, J.P.; Loarie, S.R. Climate change, elevational range shifts, and bird extinctions. Conserv. Biol. 2008, 22, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urban, M.C.; Bocedi, G.; Hendry, A.P.; Mihoub, J.B.; Pe’er, G.; Singer, A.; Bridle, J.R.; Crozier, L.G.; De Meester, L.; Godsoe, W.; et al. Improving the forecast for biodiversity under climate change. Science 2016, 353, aad8466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022.

- Pecl, G.T.; Araújo, M.B.; Bell, J.D.; Blanchard, J.; Bonebrake, T.C.; Chen, I.C.; Clark, T.D.; Colwell, R.K.; Danielsen, F.; Evengård, B.; et al. Biodiversity redistribution under climate change: Impacts on ecosystems and human well-being. Science 2017, 355, eaai9214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, R.; Price, J.; Graham, E.; Forstenhaeusler, N.; VanDerWal, J. The projected effect on insects, vertebrates, and plants of limiting global warming to 1.5 °C rather than 2 °C. Science 2018, 360, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trisos, C.H.; Merow, C.; Pigot, A.L. The projected timing of abrupt ecological disruption from climate change. Nature 2020, 580, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerly, D.D.; Loarie, S.R.; Cornwell, W.K.; Weiss, S.B.; Hamilton, H.; Branciforte, R.; Kraft, N.J.B. The geography of climate change: Implications for conservation biogeography. Divers. Distrib. 2010, 16, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharouba, H.M.; Algar, A.C.; Kerr, J.T. Historically calibrated predictions of butterfly species’ range shift using global change as a pseudo-experiment. Ecology 2009, 90, 2213–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppel, G.; Van Niel, K.P.; Wardell-Johnson, G.W.; Yates, C.J.; Byrne, M.; Mucina, L.; Schut, A.G.T.; Hopper, S.D.; Franklin, S.E. Refugia: Identifying and understanding safe havens for biodiversity under climate change. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012, 21, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcroft, M.B. Identifying refugia from climate change. J. Biogeogr. 2010, 37, 1407–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A.; Green, D.M. Dispersal and the metapopulation paradigm in amphibian ecology and conservation: Are all amphibian populations metapopulations? Ecography 2005, 28, 110–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semlitsch, R.D. Principles for management of aquatic-breeding amphibians. J. Wildl. Manage 2000, 64, 615–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, N.M.; Brudvig, L.A.; Clobert, J.; Davies, K.F.; Gonzalez, A.; Holt, R.D.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Sexton, J.O.; Austin, M.P.; Collins, C.D.; et al. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannah, L.; Midgley, G.; Andelman, S.; Araújo, M.; Hughes, G.; Martinez-Meyer, E.; Pearson, R.; Williams, P. Protected area needs in a changing climate. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2007, 5, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, N.E.; Zavaleta, E.S. Biodiversity management in the face of climate change: A review of 22 years of recommendations. Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.S.; Danehy, R.J. A synthesis of the ecology of headwater streams and their riparian zones in temperate forests. For. Sci. 2007, 53, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulse, C.D.; Semlitsch, R.D.; Trauth, K.M.; Williams, A.D. Influences of design and landscape placement parameters on amphibian abundance in constructed wetlands. Wetlands 2010, 30, 915–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, P.; Noss, R.F. Do habitat corridors provide connectivity? Conserv. Biol. 1998, 12, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert-Norton, L.; Wilson, R.; Stevens, J.R.; Beard, K.H. A meta-analytic review of corridor effectiveness. Conserv. Biol. 2010, 24, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crooks, K.R.; Sanjayan, M. Connectivity Conservation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0-521-67381-6. [Google Scholar]

- Huntley, B.; Barnard, P.; Altwegg, R.; Chambers, L.; Coetzee, B.W.T.; Gibson, L.; Hockey, P.A.R.; Hole, D.G.; Midgley, G.F.; Underhill, L.G.; et al. Beyond bioclimatic envelopes: Dynamic species’ range and abundance modelling in the context of climatic change. Ecography 2008, 31, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littell, J.S.; Peterson, D.L.; Millar, C.I.; O’Halloran, K.A. U.S. National Forests Adapt to Climate Change through Science-Management Partnerships. Clim. Change 2012, 110, 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Class | Order | Scientific Name | Red List Category 1 | ME Endangered Grade 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphibia | Caudata | Hynobius yangi | EN | II |

| Amphibia | Anura | Dryophytes suweonensis | EN | I |

| Amphibia | Anura | Pelophylax chosenicus | VU | II |

| Amphibia | Anura | Kaloula borealis | VU | II |

| Reptilia | Squamata | Sibynophis chinensis | EN | I |

| Reptilia | Squamata | Eremias argus | VU | II |

| Reptilia | Squamata | Elaphe schrenckii | VU | II |

| Reptilia | Testudines | Mauremys reevesii | VU | II |

| Species | Raw Occurrences (n) | After 1 km Thinning (n) |

|---|---|---|

| H. yangi | 178 | 87 |

| E. schrenckii | 87 | 71 |

| P. chosenicus | 191 | 96 |

| M. reevesii | 37 | 25 |

| K. borealis | 356 | 122 |

| S. chinensis | 30 | 23 |

| D. suweonensis | 228 | 129 |

| E. argus | 45 | 23 |

| Metric | Mean | Min | Max | Std |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROC-AUC | 0.843 | 0.575 | 0.992 | 0.120 |

| TSS | 0.654 | 0.177 | 0.985 | 0.221 |

| Kappa | 0.460 | 0.047 | 0.797 | 0.231 |

| Model | Mean ROC-AUC | Min | Max | Std | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMW | 0.897 | 0.715 | 0.992 | 0.099 | 1 |

| EM | 0.892 | 0.710 | 0.992 | 0.103 | 2 |

| RF | 0.889 | 0.660 | 0.992 | 0.108 | 3 |

| GBM | 0.885 | 0.679 | 0.988 | 0.105 | 4 |

| GLM | 0.864 | 0.682 | 0.977 | 0.118 | 5 |

| FDA | 0.860 | 0.670 | 0.988 | 0.125 | 6 |

| MARS | 0.844 | 0.642 | 0.978 | 0.134 | 7 |

| ANN | 0.830 | 0.638 | 0.975 | 0.135 | 8 |

| MAXENT | 0.816 | 0.682 | 0.913 | 0.071 | 9 |

| CTA | 0.806 | 0.575 | 0.987 | 0.137 | 10 |

| SRE | 0.690 | 0.587 | 0.773 | 0.074 | 11 |

| Model | Mean ROC-AUC | Std | CV (%) * | Range | IQR † | Stability Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAXENT | 0.816 | 0.071 | 8.7 | 0.231 | 0.089 | 1 |

| SRE | 0.690 | 0.074 | 10.7 | 0.186 | 0.098 | 2 |

| EMW | 0.897 | 0.099 | 11.0 | 0.277 | 0.124 | 3 |

| EM | 0.892 | 0.103 | 11.5 | 0.282 | 0.128 | 4 |

| GBM | 0.885 | 0.105 | 11.9 | 0.309 | 0.142 | 5 |

| RF | 0.889 | 0.108 | 12.1 | 0.332 | 0.156 | 6 |

| GLM | 0.864 | 0.118 | 13.7 | 0.295 | 0.167 | 7 |

| FDA | 0.860 | 0.125 | 14.5 | 0.318 | 0.189 | 8 |

| MARS | 0.844 | 0.134 | 15.9 | 0.336 | 0.198 | 9 |

| ANN | 0.830 | 0.135 | 16.3 | 0.337 | 0.201 | 10 |

| CTA | 0.806 | 0.137 | 17.0 | 0.412 | 0.223 | 11 |

| Species | Class | Mean ROC-AUC | Min | Max | Std | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. chinensis | Reptilia | 0.992 | 0.988 | 0.997 | 0.003 | 0.009 |

| D. suweonensis | Amphibia | 0.981 | 0.974 | 0.987 | 0.004 | 0.013 |

| H. yangi | Amphibia | 0.964 | 0.935 | 0.987 | 0.014 | 0.052 |

| P. chosenicus | Amphibia | 0.929 | 0.887 | 0.951 | 0.021 | 0.064 |

| K. borealis | Amphibia | 0.918 | 0.872 | 0.955 | 0.021 | 0.083 |

| E. argus | Reptilia | 0.890 | 0.805 | 0.938 | 0.041 | 0.133 |

| M. reevesii | Reptilia | 0.784 | 0.659 | 0.903 | 0.071 | 0.244 |

| E. schrenckii | Reptilia | 0.715 | 0.666 | 0.824 | 0.043 | 0.158 |

| Amphibia Mean | - | 0.948 | - | - | 0.015 | |

| Reptilia Mean | - | 0.845 | - | - | 0.04 | |

| Overall Mean | - | 0.897 | - | - | 0.027 |

| Species | Mean ROC-AUC | Std | CV (%) * | Range (max-min) | Consensus Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. chinensis | 0.912 | 0.047 | 5.2 | 0.219 | Very High |

| D. suweonensis | 0.894 | 0.061 | 6.8 | 0.272 | High |

| H. yangi | 0.878 | 0.073 | 8.3 | 0.305 | High |

| P. chosenicus | 0.851 | 0.089 | 10.5 | 0.286 | Moderate |

| K. borealis | 0.847 | 0.096 | 11.3 | 0.380 | Moderate |

| E. argus | 0.824 | 0.112 | 13.6 | 0.300 | Moderate-Low |

| E. schrenckii | 0.748 | 0.14 | 18.7 | 0.237 | Low |

| M. reevesii | 0.772 | 0.171 | 22.1 | 0.244 | Very Low |

| Species | BIO1 | BIO2 | BIO3 | BIO12 | BIO13 | BIO14 | Elevation | Slope | Dist_Water | Wetness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. yangi | 0.205 | 0.109 | 0.022 | 0.159 | 0.031 | 0.443 | 0.007 | 0.014 | 0.01 | 0.001 |

| E. schrenckii | 0.330 | 0.054 | 0.098 | 0.056 | 0.079 | 0.093 | 0.068 | 0.098 | 0.111 | 0.013 |

| P. chosenicus | 0.047 | 0.050 | 0.044 | 0.099 | 0.120 | 0.081 | 0.369 | 0.097 | 0.072 | 0.021 |

| M. reevesii | 0.252 | 0.041 | 0.08 | 0.035 | 0.289 | 0.034 | 0.080 | 0 | 0.182 | 0.006 |

| K. borealis | 0.120 | 0.041 | 0.098 | 0.056 | 0.108 | 0.088 | 0.061 | 0.255 | 0.162 | 0.012 |

| S. chinensis | 0.014 | 0.392 | 0.065 | 0.037 | 0 | 0.439 | 0.044 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0 |

| D. suweonensis | 0.058 | 0.099 | 0.027 | 0.283 | 0.081 | 0.058 | 0.112 | 0.244 | 0.025 | 0.014 |

| E. argus | 0.064 | 0.138 | 0.065 | 0.138 | 0.048 | 0.193 | 0.205 | 0.008 | 0.069 | 0 |

| Variable | Amphibia Mean | Reptilia Mean | Reptilia * | Difference † |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIO1 | 0.107 | 0.165 | 0.215 | −0.058 |

| BIO2 | 0.075 | 0.156 | 0.078 | −0.081 |

| BIO3 | 0.048 | 0.077 | 0.081 | −0.029 |

| BIO12 | 0.149 | 0.067 | 0.076 | 0.083 |

| BIO13 | 0.085 | 0.104 | 0.139 | −0.019 |

| BIO14 | 0.168 | 0.190 | 0.107 | −0.022 |

| elevation | 0.137 | 0.099 | 0.118 | 0.038 |

| slope | 0.152 | 0.046 | 0.059 | 0.106 |

| dist_water | 0.067 | 0.091 | 0.121 | −0.024 |

| wetness | 0.012 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.007 |

| Temperature sum ‡ | 0.230 | 0.398 | 0.374 | −0.168 |

| Precipitation sum § | 0.402 | 0.360 | 0.322 | 0.042 |

| Topographic sum ¶ | 0.290 | 0.146 | 0.177 | 0.144 |

| Hydrological sum ** | 0.079 | 0.096 | 0.127 | −0.017 |

| Species | BIO1 | BIO2 | BIO3 | BIO12 | BIO13 | BIO14 | Elevation | Slope | Dist_water | Wetness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. yangi | 2 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 10 |

| E. schrenckii | 1 | 9 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 10 |

| P. chosenicus | 8 | 7 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 10 |

| M. reevesii | 2 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 3 | 9 |

| K. borealis | 3 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 10 |

| S. chinensis | 6 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| D. suweonensis | 6 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 10 |

| E. argus | 8 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 10 |

| Variable | BIO1 | BIO2 | BIO3 | BIO12 | BIO13 | BIO14 | Elevation | Slope | Dist_Water | Wetness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIO1 | 1 | 0.142 | 0.682 | −0.245 | −0.089 | −0.312 | −0.198 | 0.287 | 0.412 | 0.056 |

| BIO2 | 0.142 | 1 | 0.715 | 0.089 | −0.156 | 0.587 | 0.234 | −0.098 | −0.267 | −0.189 |

| BIO3 | 0.682 | 0.715 | 1 | −0.123 | −0.201 | 0.298 | 0.076 | 0.134 | 0.045 | −0.112 |

| BIO12 | −0.245 | 0.089 | −0.123 | 1 | 0.524 | 0.231 | 0.156 | −0.089 | −0.312 | 0.098 |

| BIO13 | −0.089 | −0.156 | −0.201 | 0.524 | 1 | 0.187 | 0.289 | −0.167 | −0.098 | 0.134 |

| BIO14 | −0.312 | 0.587 | 0.298 | 0.231 | 0.187 | 1 | 0.089 | −0.234 | −0.412 | −0.156 |

| elevation | −0.198 | 0.234 | 0.076 | 0.156 | 0.289 | 0.089 | 1 | 0.318 | −0.156 | 0.023 |

| slope | 0.287 | −0.098 | 0.134 | −0.089 | −0.167 | −0.234 | 0.318 | 1 | 0.267 | 0.089 |

| dist_water | 0.412 | −0.267 | 0.045 | −0.312 | −0.098 | −0.412 | −0.156 | 0.267 | 1 | −0.045 |

| wetness | 0.056 | −0.189 | −0.112 | 0.098 | 0.134 | −0.156 | 0.023 | 0.089 | −0.045 | 1 |

| Species | Shannon Index (H′) | Classification | Primary Variables (>15% Contribution) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. chinensis | 1.523 | Specialist | BIO14 (43.9%), BIO2 (39.2%) |

| H. yangi | 1.628 | Moderate Specialist | BIO14 (44.3%), BIO1 (20.5%), BIO12 (15.9%) |

| D. suweonensis | 1.753 | Moderate Specialist | BIO12 (28.3%), slope (24.4%) |

| P. chosenicus | 1.828 | Moderate Specialist | elevation (36.9%) |

| E. argus | 1.872 | Moderate Specialist | elevation (20.5%), BIO14 (19.3%) |

| K. borealis | 1.965 | Generalist | slope (25.5%), dist_water (16.2%) |

| M. reevesii | 2.011 | Generalist | BIO13 (28.9%), BIO1 (25.2%), dist_water (18.2%) |

| E. schrenckii | 2.058 | Generalist | BIO1 (33.0%) |

| Species | S. chinensis | H. yangi | D. suweonensis | P. chosenicus | K. borealis | E. argus | M. reevesii | E. schrenckii |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. chinensis | 1.000 | 0.524 | 0.429 | 0.738 | 0.310 | 0.714 | 0.238 | 0.190 |

| H. yangi | 0.524 | 1.000 | 0.905 ** | 0.595 | 0.429 | 0.476 | 0.333 | 0.357 |

| D. suweonensis | 0.429 | 0.905 ** | 1.000 | 0.619 | 0.548 | 0.500 | 0.405 | 0.452 |

| P. chosenicus | 0.738 | 0.595 | 0.619 | 1.000 | 0.595 | 0.810 ** | 0.524 | 0.500 |

| K. borealis | 0.310 | 0.429 | 0.548 | 0.595 | 1.000 | 0.524 | 0.786 ** | 0.738 |

| E. argus | 0.714 | 0.476 | 0.5 | 0.810 ** | 0.524 | 1.000 | 0.429 | 0.452 |

| M. reevesii | 0.238 | 0.333 | 0.405 | 0.524 | 0.786 ** | 0.429 | 1.000 | 0.595 |

| E. schrenckii | 0.190 | 0.357 | 0.452 | 0.500 | 0.738 | 0.452 | 0.595 | 1.000 |

| Species | Niche Breadth (H′) | Model Performance (ROCAUC) | Projected Habitat Change * | Vulnerability Level | Conservation Priority |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. chinensis | 1.523 | 0.992 | 42.30% | High | Immediate |

| H. yangi | 1.628 | 0.964 | 38.70% | High | Immediate |

| D. suweonensis | 1.753 | 0.981 | 31.50% | High | Immediate |

| P. chosenicus | 1.828 | 0.929 | 24.80% | Moderate | High |

| E. argus | 1.872 | 0.89 | 22.10% | Moderate | High |

| K. borealis | 1.965 | 0.918 | 18.60% | Moderate | Moderate |

| M. reevesii | 2.011 | 0.784 | 12.40% | Low | Moderate |

| E. schrenckii | 2.058 | 0.715 | 8.90% | Low | Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, J.-H.; Chang, M.-H.; Shin, M.-S.; Lee, E.-S.; Lee, J.-S.; Seo, C.-W. Ensemble Species Distribution Modeling of Climate Change Impacts on Endangered Amphibians and Reptiles in South Korea. Animals 2026, 16, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010095

Lee J-H, Chang M-H, Shin M-S, Lee E-S, Lee J-S, Seo C-W. Ensemble Species Distribution Modeling of Climate Change Impacts on Endangered Amphibians and Reptiles in South Korea. Animals. 2026; 16(1):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010095

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jae-Ho, Min-Ho Chang, Man-Seok Shin, Eun-Seo Lee, Jae-Seok Lee, and Chang-Wan Seo. 2026. "Ensemble Species Distribution Modeling of Climate Change Impacts on Endangered Amphibians and Reptiles in South Korea" Animals 16, no. 1: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010095

APA StyleLee, J.-H., Chang, M.-H., Shin, M.-S., Lee, E.-S., Lee, J.-S., & Seo, C.-W. (2026). Ensemble Species Distribution Modeling of Climate Change Impacts on Endangered Amphibians and Reptiles in South Korea. Animals, 16(1), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010095