The Impact of Nanoplastics on the Quality of Fish Sperm: A Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

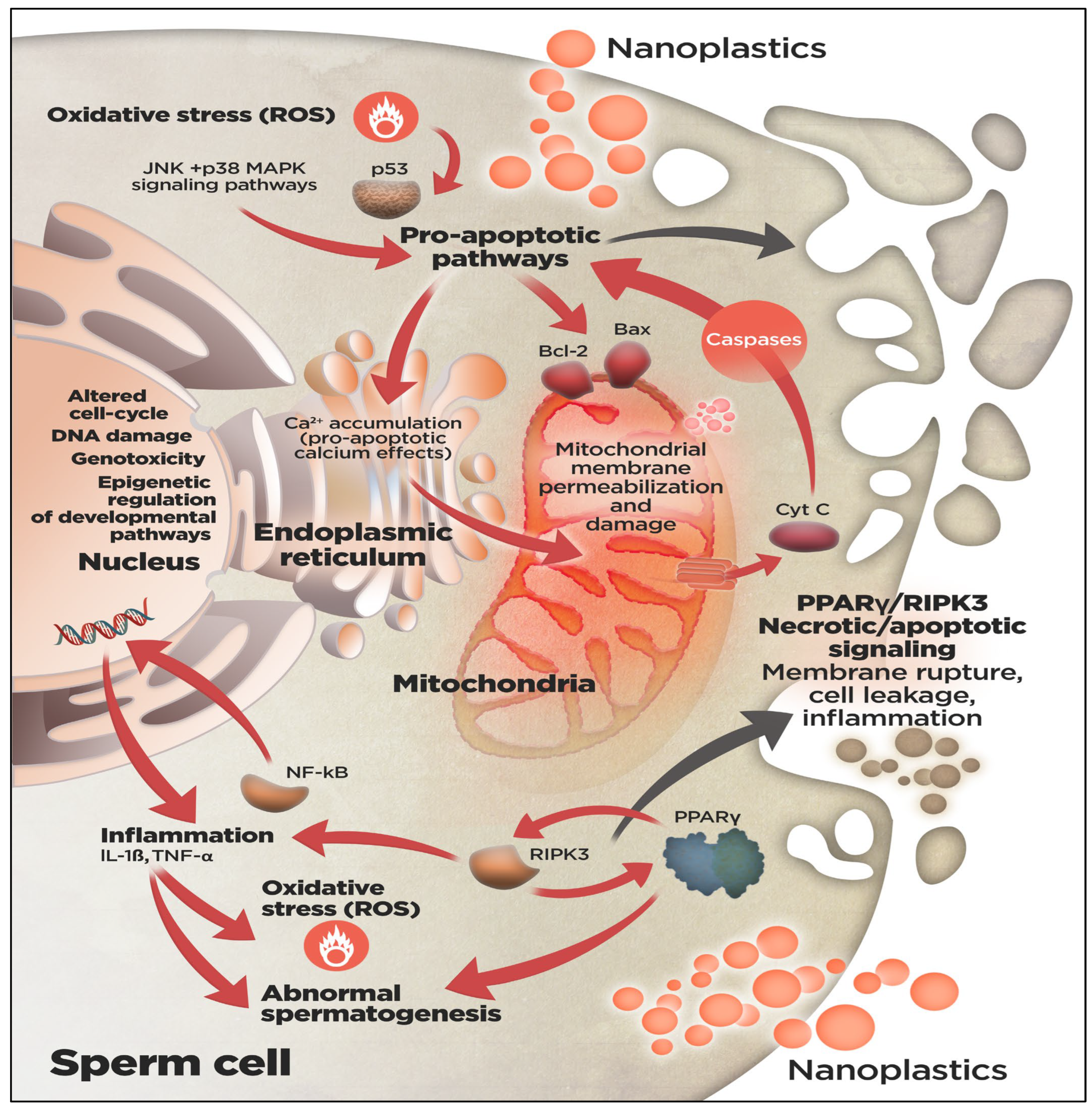

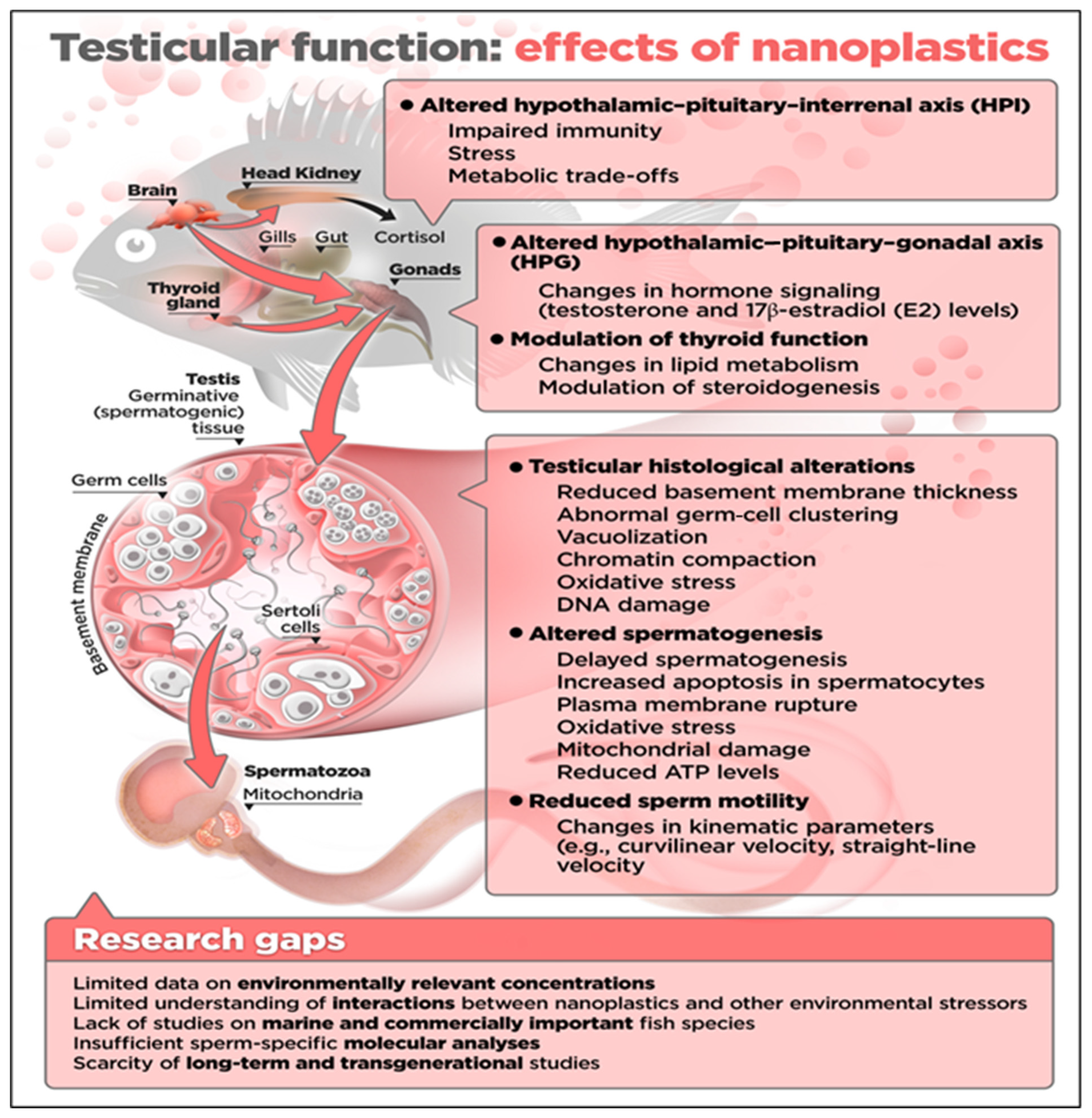

3. Effects of NPs on the Quality of Sperm in Fish

3.1. Sperm Motility

3.2. Effects on Sperm Viability and Fertilization Capacity

3.3. Transgenerational and Developmental Effects

4. Knowledge Gaps

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilkinson, J.; Hooda, P.S.; Barker, J.; Barton, S.; Swinden, J. Occurrence, fate and transformation of emerging contaminants in water: An overarching review of the field. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 231, 954–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Yang, F.; Pang, Q.; Peng, F.; Xu, B.; Wang, L.; Xie, L.; Zhang, W.; Tian, L.; Hou, J.; et al. Fluvial dissolved organic matter quality modulates microbial nitrate transformation: Enhanced denitrification under low carbon-to-nitrate ratio. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 23456–23465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noyes, P.D.; Miranda, D.; Oliveira de Carvalho, G.; Perfetti-Bolaño, A.; Guida, Y.; Barbosa Machado Torres, F.; Barra, R.O. Climate change drives persistent organic pollutant dynamics in marine environments. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thushari, G.G.N.; Senevirathna, J.D.M. Plastic pollution in the marine environment. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekman, M.B.; Walther, B.; Peter, C.; Gutow, L.; Bergmann, M. Impacts of Plastic Pollution in the Oceans on Marine Species, Biodiversity and Ecosystems; WWW Germany: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, M.F.; Andrade, V.S.; Ale, A.; Monserrat, J.M.; Roa-Fuentes, C.A.; Herrera-Martínez, Y.; Wiegand, C. Responses of freshwater organisms to multiple stressors in a climate change scenario: A review on small-scale experiments. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 4431–4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.P.; Piferrer, F.; Chen, S.; Shen, Z.G. (Eds.) Sex Control in Aquaculture; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigault, J.; Ter Halle, A.; Baudrimont, M.; Pascal, P.Y.; Gauffre, F.; Phi, T.L.; El Hadri, H.; Grassl, B.; Reynaud, S. Current opinion: What is a nanoplastic? Environ. Pollut. 2018, 235, 1030–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowicz, I.; Enebro, J.; Yarahmadi, N. Challenges in the search for nanoplastics in the environment—A critical review from the polymer science perspective. Polym. Test. 2021, 93, 106953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Yu, H.; Yi, J.; Lei, P.; He, J.; Ruan, J.; Zhang, X. Behavioral studies of zebrafish reveal a new perspective on the reproductive toxicity of micro-and nanoplastics. Toxics 2024, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasmahapatra, A.K.; Chatterjee, J.; Tchounwou, P.B. A systematic review of the effects of nanoplastics on fish. Front. Toxicol. 2025, 7, 1530209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, X.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wen, W.; Yang, Z. Promoting effects of lipophilic pollutants on the reproductive toxicity of proteinophilic pollutants to Daphnia magna under chronic exposure. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 372, 126013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Han, R.; Yao, Z.; Yan, H.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Yue, T.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Z.; Xing, B. Intergenerational transfer of micro (nano) plastics in different organisms. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 488, 137404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, T.C.; de Deus, B.C.T.; Altomari, L.N.; Cardoso, S.J. The effect of plastic pollution on coastal marine organisms—A systematic review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Peng, R. Toxic effects of microplastic and nanoplastic on the reproduction of teleost fish in aquatic environments. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 62530–62548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, I.A.; Dar, J.Y.; Ahmad, I.; Mir, I.N.; Bhat, H.; Bhat, R.A.H.; Ganie, P.A.; Sharma, R. Testicular development and spermatogenesis in fish: Insights into molecular aspects and regulation of gene expression by different exogenous factors. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 2142–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitano, J.; Ansai, S.; Takehana, Y.; Yamamoto, Y. Diversity and convergence of sex-determination mechanisms in teleost fish. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 12, 233–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pujol, G.; Marín-Gual, L.; González-Rodelas, L.; Álvarez-González, L.; Chauvigné, F.; Cerdà, J.; Teles, M.; Roher, N.; Ruiz-Herrera, A. Short-term polystyrene nanoplastic exposure alters zebrafish male and female germline and reproductive outcomes, unveiling pollutant-impacted molecular pathways. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 481, 136529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, R.; Chen, Z.; Fu, X.; Wu, Z.; Chen, J.; Xie, L.; Zong, H.; Mu, J. Dietary exposure to sulfamethazine, nanoplastics and their binary mixture disrupts the spermatogenesis of marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma). Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2024, 43, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wu, B.; Yi, J.; Yu, H.; He, J.; Teng, F.; Xi, T.; Zhao, J.; Ruan, J.; Xu, P.; et al. Impacts of environmental concentrations of nanoplastics on zebrafish neurobehavior and reproductive toxicity. Toxics 2024, 12, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaripour, S.; Huuskonen, H.; Rahman, T.; Kekäläinen, J.; Akkanen, J.; Magris, M.; Kipriianov, P.V.; Kortet, R. Pre-fertilization exposure of sperm to nano-sized plastic particles decreases offspring size and swimming performance in the European whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus). Environ. Pollut. 2021, 291, 118196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Li, L.; Alava, J.J.; Yan, Z.; Chen, P.; Gul, Y.; Wang, L.; Xiong, D. Female zebrafish (Danio rerio) exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics induces reproductive toxicity in mother and their offspring. Aquat. Toxicol. 2024, 273, 107023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, W.; Yuan, Y.; Ju, W.; Wu, B.; Hu, L.; Tuo, X.; Jiang, M.; Zhao, S. Synergistic reproductive toxicity of microcystin-LR and polystyrene micro/nano-plastics in male zebrafish. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 299, 118377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contino, M.; Ferruggia, G.; Indelicato, S.; Pecoraro, R.; Scalisi, E.M.; Salvaggio, A.; Brundo, M.V. Polystyrene nanoplastics in aquatic microenvironments affect sperm metabolism and fertilization of Mytilus galloprovincialis (lamark, 1819). Toxics 2023, 11, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Gan, X.; Lin, C.; Wang, D.; Chen, R.; Dai, Y.; Jiang, L.; Huang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Song, Y.; et al. Polystyrene nanoplastics cause reproductive toxicity in zebrafish: PPAR mediated lipid metabolism disorder. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 931, 172795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallec, K.; Paul-Pont, I.; Boulais, M.; Le Goïc, N.; González-Fernández, C.; Le Grand, F.; Bideau, A.; Quéré, C.; Cassone, A.L.; Lambert, C.; et al. Nanopolystyrene beads affect motility and reproductive success of oyster spermatozoa (Crassostrea gigas). Nanotoxicology 2020, 14, 1039–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Jin, Y.; Luo, P.; Shi, X. Polystyrene microplastics induced male reproductive toxicity and transgenerational effects in freshwater prawn. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 842, 156820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, H. Enhanced toxicity of triphenyl phosphate to zebrafish in the presence of micro-and nano-plastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 143986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiang, L.; Cheng, J. Exposure to polystyrene microplastics impairs gonads of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Chemosphere 2021, 263, 128161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Jin, Q.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, M. Chronic nanoplastic exposure induced oxidative and immune stress in medaka gonad. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 869, 161838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xian, H.; Ye, R.; Zhong, Y.; Liang, B.; Huang, Y.; Dai, M.; Guo, J.; Tang, S.; Ren, X.; et al. Gender-specific effects of polystyrene nanoplastic exposure on triclosan-induced reproductive toxicity in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 932, 172876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arienzo, M.; Ferrara, L. Environmental fate of metal nanoparticles in estuarine environments. Water 2022, 14, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Tong, L.; Zhang, W. Microplastics in freshwater environments: Sources, fates and toxicity. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, B.; Lin, D. Sexual maturation, reproductive habits, and fecundity of fish. In Biology of Fishery Resources; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 113–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comizzoli, P.; Amelkina, O.; Lee, P.C. Damages and stress responses in sperm cells and other germplasms during dehydration and storage at nonfreezing temperatures for fertility preservation. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2022, 89, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, F.; Bondarenko, O.; Boryshpolets, S. Osmoregulation in fish sperm. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 47, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Sun, J.; Zhou, L.; Teng, M.; Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Wu, F. Defining the size ranges of polystyrene nanoplastics according to their ability to cross biological barriers. Environ. Sci. Nano 2023, 10, 2634–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombul, O.K.; Akdağ, A.D.; Thomas, P.B.; Kaluç, N. Assessing the impact of sub-chronic polyethylene terephthalate nanoplastic exposure on male reproductive health in mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2025, 495, 117235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contino, M.; Ferruggia, G.; Indelicato, S.; Pecoraro, R.; Scalisi, E.M.; Bracchitta, G.; Dragotto, J.; Salvaggio, A.; Brundo, M.V. In vitro nano-polystyrene toxicity: Metabolic dysfunctions and cytoprotective responses of human spermatozoa. Biology 2023, 12, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Xu, K.; Du, W.; Wang, S.; Jiang, M.; Wang, Y.; Han, Q.; Chen, M. Comparing the effects and mechanisms of exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics with different functional groups on the male reproductive system. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 922, 171299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Hao, F.; Liang, H.; Liu, W.; Guo, Y. Exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics impairs sperm metabolism and pre-implantation embryo development in mice. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1562331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Deng, T.; Duan, J.; Xie, J.; Yuan, J.; Chen, M. Exposure to polystyrene microplastics causes reproductive toxicity through oxidative stress and activation of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 190, 110133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urli, S.; Corte Pause, F.; Crociati, M.; Baufeld, A.; Monaci, M.; Stradaioli, G. Impact of microplastics and nanoplastics on livestock health: An emerging risk for reproductive efficiency. Animals 2023, 13, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenol, O.; Sulukan, E.; Baran, A.; Bolat, İ.; Toraman, E.; Alak, G.; Yildirim, S.; Bilgin, G.; Ceyhun, S.B. Global warming and nanoplastic toxicity; small temperature increases can make gill and liver toxicity more dramatic, which affects fillet quality caused by polystyrene nanoplastics in the adult zebrafish model. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, K.; Cao, C.; Li, D.; Akbar, S.; Yang, Z. The thermal regime modifies the response of aquatic keystone species Daphnia to microplastics: Evidence from population fitness, accumulation, histopathological analysis and candidate gene expression. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 783, 147154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanpradit, P.; Byeon, E.; Lee, J.S.; Jeong, H.; Kim, H.S.; Peerakietkhajorn, S.; Lee, J.S. Combined effects of nanoplastics and elevated temperature in the freshwater water flea Daphnia magna. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, R.; Trimpey-Warhaftig, R.; Gaston, K.; Butron, L.; Gaballah, S.; Di Giulio, R.T. Polystyrene nanoplastics impact the bioenergetics of developing zebrafish and limit molecular and physiological adaptive responses to acute temperature stress. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 958, 178026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, R.; Ranasinghe, P.; Jayasundara, N.; Di Giulio, R.T. Nanoplastics in aquatic environments: Impacts on aquatic species and interactions with environmental factors and pollutants. Toxics 2022, 10, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Materić, D.; Peacock, M.; Dean, J.; Futter, M.; Maximov, T.; Moldan, F.; Röckmann, T.; Holzinger, R. Presence of nanoplastics in rural and remote surface waters. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 054036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaid, M.; Liu, S.; Liao, H.; Yue, Q.; Wang, J. Environmental nanoplastics quantification by pyrolysis-gas chromatography–mass spectrometry in the Pearl River, China: First insights into spatiotemporal distributions, compositions, sources and risks. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 476, 135055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ou, Q.; Jiao, M.; Liu, G.; Van Der Hoek, J.P. Identification and quantification of nanoplastics in surface water and groundwater by pyrolysis gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 4988–4997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoffo, E.D.; Thomas, K.V. Quantitative analysis of nanoplastics in environmental and potable waters by pyrolysis-gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 464, 133013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, J.; Ma, Y.; Ruan, J.; You, S.; Ma, J.; Yu, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, K.; Yang, Q.; Jin, L.; et al. The invisible threat: Assessing the reproductive and transgenerational impacts of micro-and nanoplastics on fish. Environ. Int. 2024, 183, 108432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.; Bigman, J.S.; Dulvy, N.K. The metabolic pace of life histories across fishes. Proc. R. Soc. B 2021, 288, 20210910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Keywords | PubMed | Google Scholar | Web of Science |

|---|---|---|---|

| NPs effect on fish sperm viability | 3 | 742 | 4 |

| NPs effect on fish sperm motility | 3 | 832 | 9 |

| NPs effect on fish sperm fertilization capacity | 0 | 337 | 0 |

| NPs effect on fish reproduction | 12 | 3840 | 90 |

| NPs effect on fish sperm metabolism | 0 | 674 | 0 |

| Species | Plastic Polymer | Exposure Route | Dose | Effects (Major Findings) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) (adult males and females). | Polystyrene nanoplastics (PS-NPs), ~45–50 nm diameter | Waterborne exposure (added directly into aquarium water) | An amount of 5 mg/L (5000 µg/L) PS-NPs. Exposure duration: 96 h (acute short-term exposure) | Males: Testicular damage, increased spermatocyte apoptosis, nanoplastic uptake by germ cells, strong gene dysregulation affecting meiosis and DNA repair, and reduced sperm motility. Females: Delayed oocyte development with minor, non-significant reduction in egg production. Reproductive capacity: Impaired fertilization success, shown by delayed hatching, reduced larval survival, and lower heart rate in offspring. | [18] |

| Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | PS-NPs ~ 100 nm square fragments | Dietary (fish fed with feed mixed with SMZ, PS, or both) | A total of 3.45 mg/g dry feed | SMZ: ~35% GSI reduction, inhibited Aund self-renewal, and disrupted hormonal and apoptotic regulation. PS: No GSI or germ cell changes, but altered spermatogenesis gene expression. SMZ and PS: PS partially rescued GSI by promoting spermatogonia differentiation, without restoring Aund self-renewal | [19] |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | PS-NPs, 50 nm | Waterborne exposure | An amount of 1 mg/L (21 days) | Gonads: PS-NPs impaired gametogenesis—fewer mature sperm and oocytes, delayed spermatogenesis and oocyte maturation. Hormones: Sex-hormone imbalance in both sexes, indicating endocrine disruption. Genes: Dysregulated BPG–axis and steroidogenesis genes. Outcome: Long-term PS-NP exposure caused oxidative stress and reproductive dysfunction | [20] |

| European whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus) | PS (specifically, 50 nm spherical PS-NPs coated with carboxyl groups, red fluorescent, Ex: 552 nm, Em: 580 nm) | Sperm from males was directly exposed to NPs in activation water for 10 s before being used to fertilize eggs | Low dose: 100 particles per spermatozoa High dose: 10,000 particles per spermatozoa | Sperm: High dose reduced motile sperm (more static cells) and altered swimming pattern; low dose had no effect. Embryos: No change in mortality; high dose accelerated hatching. Offspring: High dose reduced body mass and swimming performance, with no effect on length. | [21] |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | PS (specifically, 100 nm spherical PS-NPs with green fluorescence, Ex: 488 nm, Em: 518 nm) | Chronic waterborne exposure of female adults (F0) for 42 days; offspring (F1) raised in clean water but exposed via maternal transfer (PS-NPs detected in F1 embryos and larvae) | Low dose: 200 μg/L High dose: 2000 μg/L | Bioaccumulation: Dose-dependent buildup with maternal transfer to embryos and larvae. F0 reproduction: High dose reduced egg production and ovary maturity, with E2 ↓, T ↑, and disrupted HPG–axis genes. F1 effects: Faster hatching, higher larval heart rate, altered neuroendocrine and sex-differentiation gene expression, but no change in adult sex ratio or ovary structure. | [22] |

| Male zebrafish (Danio rerio) | PS; microplastics [PSMPs] of 5 μm diameter; NPs [PSNPs] of 80 nm diameter) | Waterborne (chronic exposure in aerated glass tanks with renewal of exposure solutions every 3 days); also in vitro exposure on mouse GC-2 spermatocytes | PSMPs/PSNPs: 1 mg/L Microcystin-LR (MCLR): 0, 5, 25 μg/L Combinations: MCLR (5 or 25 μg/L) and PSMPs (1 mg/L) or PSNPs (1 mg/L) (Exposure duration: 45 days for in vivo; various for in vitro) | Synergy: PS (especially PSNPs) increased MCLR bioavailability, causing stronger combined testicular toxicity than single exposures. Mechanisms: Co-exposure amplified oxidative stress, DNA damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cell-cycle arrest in spermatogenic cells. Reproduction: Reduced GSI, severe testicular damage, and high risk of impaired spermatogenesis and fertility. | [23] |

| Mediterranean mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis) | PS (specifically, 50 nm amino-modified PS-NPs [nPS-NH2]; 100 nm NPs also tested but showed no significant effects) | Waterborne exposure of sperm in controlled aquatic microenvironments (in vitro; sperm incubated with NPs for 30 min prior to fertilization) | Low: 0.1 mg/L Medium: 1 mg/L High: 10 mg/L (100 nm NPs tested at same concentrations but showed no significant effects) | Size-dependent toxicity: 50 nm nPS-NH2 (not 100 nm) induced ROS, mitochondrial damage, and ATP loss in sperm. Sperm quality: High doses reduced motility and caused membrane and DNA damage. Reproduction: Fertilization success markedly decreased at ≥1 mg/L. | [24] |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | PS-NPs with diameters of 80 nm, 200 nm, and 500 nm) | Waterborne exposure (chronic exposure in aquariums with water renewal every 2 days) | Single concentration: 0.5 mg/L (Exposures tested for each size: 80 nm, 200 nm, 500 nm; duration: 21 days for F0 adults, with F1 embryo assessment) | F0 reproduction: Delayed spermatogenesis, abnormal follicle growth, reduced GSI, strongest effects with 500 nm NPs. F1 offspring: Impaired development—higher mortality, delayed hatching (worst with 500 nm). Mechanisms: Disrupted PPAR signaling and lipid metabolism in ovaries, resembling PCOS. Size effect: 500 nm NPs caused greatest bioaccumulation and reproductive toxicity. | [25] |

| Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) | Polystyrene (specifically, 50 nm polystyrene beads with amine [50-NH2] or carboxyl [50-COOH] functional groups) | Waterborne exposure (in vitro; oyster spermatozoa incubated with NPs in filtered seawater for 1 h) | Range: 0.1 to 25 mg/mL Key tested concentrations: 0.1, 1, 10, and 25 mg/mL (for both 50-NH2 and 50-COOH beads) | Sperm motility: 50-NH2 (10 mg/mL) and 50-COOH (25 mg/mL) strongly reduced motile sperm and velocity; lower doses had no effect. Reproduction: 50-NH2 decreased embryogenesis by 59%; 50-COOH had no significant effect. Mechanism: 50-NH2 caused membrane-mediated spermiotoxicity; 50-COOH effects were due to aggregation/physical blockage. | [26] |

| Oriental river prawn (Macrobrachium nipponense) | Polystyrene (PS; specifically, polystyrene microplastics [PS-MPs] with a size of 5 μm) | Waterborne (acute exposure for larvae; chronic exposure for adults via immersion in contaminated water) | Acute exposure (larvae): 0, 2, 20 mg/L (24-h exposure) Chronic exposure (adults): 0, 2, 20 mg/L (4-week exposure) | Larvae (acute): Reduced survival and heart rate; no direct reproductive effects. Adult males (chronic): Impaired testicular development, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and disrupted steroid hormones. Reproduction: Lower hatching success, higher F1 malformations. F1 offspring: Reduced survival and immune function; bioaccumulation of PS-MPs observed. | [27] |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Polystyrene (PS; microplastics [MPS] of 5.8 μm diameter; NPs [NPS] of 46 nm diameter) | Waterborne exposure (chronic exposure via immersion in contaminated water) | MPS and NPS: 0, 20 μg/L Triphenyl phosphate (TPhP): 0, 200 μg/L Combinations: TPhP (200 μg/L) + MPS (20 μg/L) or NPS (20 μg/L) (Duration: 21 days) | Acute toxicity: MPS/NPS did not alter TPhP LC50. Reproduction: TPhP enlarged liver/gonads; NPS worsened effects, MPS minimal impact. Histology: Co-exposure impaired spermatogenesis and oogenesis, more severe with NPS. Hormones: NPS altered E2/T and Vtg levels in a sex-dependent manner. Outcome: TPhP and PS reduced egg production, fertilization, and hatchability; NPS amplified reproductive toxicity most. | [28] |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Polystyrene (specifically, polystyrene microplastics with a size of 5 μm) | Waterborne exposure (continuous immersion in contaminated water) | Low: 10 mg/L Medium: 100 mg/L High: 1000 mg/L (Duration: 21 days) | Oxidative stress: ROS increased in gonads and liver at ≥100 mg/L; no effect at 10 mg/L. Apoptosis: Elevated in testes at 1000 mg/L via p53 pathway; lower doses unaffected. Histology: Testicular basement membrane thinning at 1000 mg/L; no changes at lower doses. | [29] |

| Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) | Polystyrene (specifically, polystyrene NPs [NPs] with a diameter of 100 nm) | Waterborne exposure (chronic exposure via immersion in contaminated water) | Low: 10 particles/L Medium: 104 particles/L (10,000 particles/L) High: 106 particles/L (1,000,000 particles/L) (Duration: 3 months) | Immune & oxidative stress: Reduced LZM, SOD, CAT, GPx, and increased MDA in gonads at ≥104 particles/L. Gonads: High dose (106 particles/L) inhibited spermatogenesis and oogenesis; lower doses had no effect. Survival: Three-month exposure decreased survival, worst at 106 particles/L. | [30] |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Polystyrene (specifically, polystyrene NPs [NPs] with a diameter of 50 nm) | Waterborne exposure (chronic exposure via immersion in contaminated water) | Polystyrene NPs (NPs): 0, 10 μg/L Triclosan (TCS): 0, 0.3 μg/L Combinations: TCS (0.3 μg/L) + NPs (10 μg/L) (Duration: 21 days, with F1 generation assessment) | GSI: TCS reduced GSI; NPs alone had no effect; co-exposure further decreased GSI, especially in males. Histology: TCS impaired spermatogenesis and oogenesis; NPs worsened testicular and ovarian damage. Hormones: TCS disrupted E2/T balance; NPs amplified male E2 increase and female T elevation. Genes: Co-exposure dysregulated sex hormone and vitellogenin genes in both sexes. Reproduction (F1): Lower fertilization, hatching, and larval survival, strongest from male exposure. | [31] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Djafar, H.; Naz, S.; Rivera Del Alamo, M.M.; Balasch, J.C.; Teles, M. The Impact of Nanoplastics on the Quality of Fish Sperm: A Review. Animals 2026, 16, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010094

Djafar H, Naz S, Rivera Del Alamo MM, Balasch JC, Teles M. The Impact of Nanoplastics on the Quality of Fish Sperm: A Review. Animals. 2026; 16(1):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010094

Chicago/Turabian StyleDjafar, Hayam, Saira Naz, Maria Montserrat Rivera Del Alamo, Juan Carlos Balasch, and Mariana Teles. 2026. "The Impact of Nanoplastics on the Quality of Fish Sperm: A Review" Animals 16, no. 1: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010094

APA StyleDjafar, H., Naz, S., Rivera Del Alamo, M. M., Balasch, J. C., & Teles, M. (2026). The Impact of Nanoplastics on the Quality of Fish Sperm: A Review. Animals, 16(1), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010094