1. Introduction

Vegetable waste is a general term for tissues that have lost their utilizable value during the production, processing, distribution, and consumption of vegetables. Among this waste, leaf waste mainly comes from old leaves of leafy vegetables and pure processed leaves. In contrast, whole vegetable residues contain multiple organs such as leaves, roots, and stems. Vegetable leaves feature a high water content and a low dry matter content, and are thus inconvenient for long-distance transportation and prone to rotting [

1]. Currently, the main methods of disposal include underground burial and on-field dumping, which not only result in significant organic waste but also pose a huge threat to rural environmental safety. Feed, constituting approximately 70% of the overall production input expenses, matters considerably within the livestock industry [

2]. In recent years, the prices of feed ingredients have been gradually increasing, thereby prompting researchers to explore alternative solutions to cope with the rising costs [

3]. The application of plant protein sources, such as soybean meal, cottonseed meal, peanut meal, and rapeseed meal, to reduce animal protein in feed has been considered an effective cost-saving approach.

Solid-state fermentation is gaining recognition as a highly promising method for improving feed quality [

4]. Recent studies have revealed that microorganisms involved in feed fermentation can produce beneficial compounds such as acetic acid, ethanol, acetaldehyde, and various aromatic acids [

5]. Beyond enhancing the nutritional value, the fermentation process also generates bioactive factors, including biologically active peptides, which can inhibit the growth of harmful intestinal pathogens. The introduction of beneficial microorganisms from fermented feed into the intestinal tract establishes a dominant microbial population and thus fosters a competitive environment against detrimental microorganisms. Key strains utilized in fermentation include

Bacillus subtilis,

Lactobacilli, and yeasts, among others, with each strain offering distinct effects [

5]. Notably,

Bacillus subtilis supplementation during fermentation addresses deficiencies in endogenous digestive enzymes, while the resulting beneficial substances contribute to an improved gut microbial environment [

6].

Lactobacilli are commonly employed for carbohydrate fermentation, converting carbohydrates into lactic acid and assisting in protein and fiber breakdown [

7]. Recent research highlights the advantages of using mixed strains under optimal conditions, harnessing the full potential of each strain and achieving superior fermentation outcomes [

8]. Extensive research has demonstrated that fermented feed improves growth performance, feed efficiency, digestibility, immunity, antioxidant capacity, and gut microbiota composition [

9].

Vegetable leaves, as a type of household waste, tend to rapid spoilage and emit foul odors if not promptly and effectively managed, thus leading to significant environmental pollution [

10]. The utilization of vegetable resources as animal feed can partially alleviate the shortage of feed ingredients in China, reduce environmental pollution, and promote sustainable resource utilization. Studies by Promkot et al. have shown that fermented cassava leaf feed can increase the number of rumen microorganisms in beef cattle and significantly improve their digestion and absorption of nutrients [

11]. Research has indicated that feeding fermented

Broussonetia papyrifera bark to meat sheep can reduce the feed conversion ratio [

12]. However, existing research has focused on a narrow range of fermented plant materials, and there are critical gaps in the systematic study of fermented vegetable leaf feed: few studies have evaluated its comprehensive effects on sheep growth performance, nutritional digestibility, antioxidant, immune function, intestinal morphology, and rumen microbial composition, nor have they elucidated its potential regulatory mechanisms. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis: exploring the use of probiotics to ferment vegetable waste to prepare fermented feed by clarifying its effects on the nutrient digestibility of sheep feed, promoting sheep growth performance, and enhancing the body’s antioxidant capacity and immune function, blood biochemical indicators, intestinal morphology, and rumen microbial community structure.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Probiotics and Culture

The microorganisms used in this study adhered to the established specifications outlined in the

Catalog of Feed Additives (Announcement No. 2045) issued by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China in 2013. This catalog provides guidelines and regulations for the use of microorganisms as feed additives, ensuring their safety and efficacy in animal nutrition. By following these specifications, the study complied with the regulatory standards set forth by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, thereby ensuring the suitability and reliability of the microorganisms employed in the fermentation process.

Bacillus subtilis (CCTCC NO: 2021528),

Saccharomyces cerevisiae (CICC NO: 1769), and

Lactobacillus plantarum (CCTCC NO: M2021527) were all sourced from the College of Life Science and Engineering at Northwest Minzu University. The broccoli residue consists of broccoli leaves harvested in November, provided by Lanzhou Ruiyuan Agricultural Technology Co., Ltd. (Lanzhou, China). Priority is given to selecting processing by-products from broccoli-processing enterprises, such as outer old leaves and rhizome peels, or near-expiration and slightly damaged broccoli from supermarkets/farmers’ markets. For pretreatment, the collected broccoli residue is first spread out and sorted to remove rotten/molded parts, foreign objects like soil and stones, and thick and hard rhizomes (with a diameter exceeding 2 cm). Then, it is cleaned according to its source: processing by-products are sprayed with clean water at 0.2–0.3 MPa for 1–2 min. After cleaning, surface water is drained off, followed by air-drying in a cool and well-ventilated area for 8–12 h. Subsequently, the residue is crushed into particles with a size of 1–2 mm using a hammer mill. To prepare the vegetable leaf fermentation concentrate, a composite microbial agent consisting of

Bacillus subtilis,

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and

Lactobacillus plantarum was uniformly mixed in a mass ratio of 1:1:1. The mixture was then loaded into a fermentation bag equipped with a breathing valve. The fermentation bag was kept at room temperature and subjected to anaerobic fermentation for 5 days. The composition and nutritional profile of the vegetable leaf fermentation concentrate are presented in

Table 1. The commercial fermentation concentrate was purchased from Xi’an Tieqi Leishi Feed Co., Ltd. (Xi’an, China), and the detailed nutritional components can be found in

Table 1.

2.2. Experimental Design, Animals, and Diets

Fifty-four 6-month-old male Oula sheep were selected from Ruilin farm in Yongjing, Gansu Province, with an initial body weight of (21.53 ± 2.03) kg. After two weeks of adaptation, the sheep were randomly divided into three groups: the CON group (basal diet), the CFC group (30% commercial fermentation concentrate), and the VFC group (30% vegetable leaf fermentation concentrate), involving three replicates, with six sheep in each. Each group was raised in the same sheep house. During the pre-feeding period, the three groups of sheep were fed according to the original formula of the farm, with the experimental feed gradually added. They were given equal amounts of feed and drink at 08:00 and 18:00 every day. The composition and nutritional components of the basal diet followed the nutritional requirements set by the National Research Council (NRC) of the United States (National Research Council, 2012 [

13]). Each column was equipped with RFID electronic devices to record the daily feeding data of each sheep. The weight of each sheep was measured at the beginning and end of the experimental period, and the average daily weight gain (ADG) was calculated based on the changes in weight.

2.3. Preparation and Sample Collection

At the conclusion of the 56th day of the experiment, all sheep were weighed, and three sheep were selected from each group for slaughter. The lambs were humanely slaughtered by severing the carotid arteries and jugular veins, following the halal procedure specified in Malaysian Standard MS1500:2009 [

14]. Blood was drawn from the anterior vena cava, and the serum was separated through centrifugation. Subsequently, the lambs were eviscerated to collect rumen fluid, rumen, and liver tissue. The duodenum, jejunum, and ileum of each sheep were sectioned, and the chyme from the respective portions of the intestine was promptly frozen using liquid nitrogen. All samples were then stored in a refrigerator at −80 °C for preservation.

2.4. Apparent Digestibility Measurement

Prior to the conclusion of the feeding trial, sheep feces were collected twice daily for three consecutive days. After weighing, 100–200 g of feces was sampled, immediately mixed with 10% sulfuric acid (H

2SO

4) to preserve ammonia nitrogen, labeled, and stored at −80 °C for subsequent use. Upon thawing, the fecal samples were homogenized, dried at 65 °C for 72 h, and then allowed to equilibrate to ambient humidity at room temperature for 24 h. These fecal samples were used to determine the contents of dry matter (DM), crude protein (CP), and crude fat (EE). The apparent nutrient digestibility was evaluated using the AIA method, calculated by the following formula [

13]:

WFI = weight of feed intake; NF = concentration of nutrient in feed; WEV = weight of total excreta voided; NE = concentration of nutrient in total excreta.

2.5. H&E Staining

Sheep tissue samples from the mid-duodenum, mid-jejunum, and mid-ileum were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 h, then sectioned into 5 μm slices. After xylene dewaxing and ethanol hydration, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was used to examine tissue pathological changes.

2.6. Oxidative Stress Index Detection

According to the manufacturer’s instructions (Jiancheng, Nanjing, China), the serum of each group of sheep was tested using the corresponding detection reagent kit.

2.7. Determination of Blood Indices

For serum indices, total cholesterol (CHO), triglycerides (TG), total protein (TP), albumin (ALB), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), glucose (GLU), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and creatine kinase (CK) were determined using an automatic biochemical analyzer (Mindray BS-420, Shenzhen Mindray Bio-Medical Electronics Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China).

2.8. Gut Microbiome Analysis

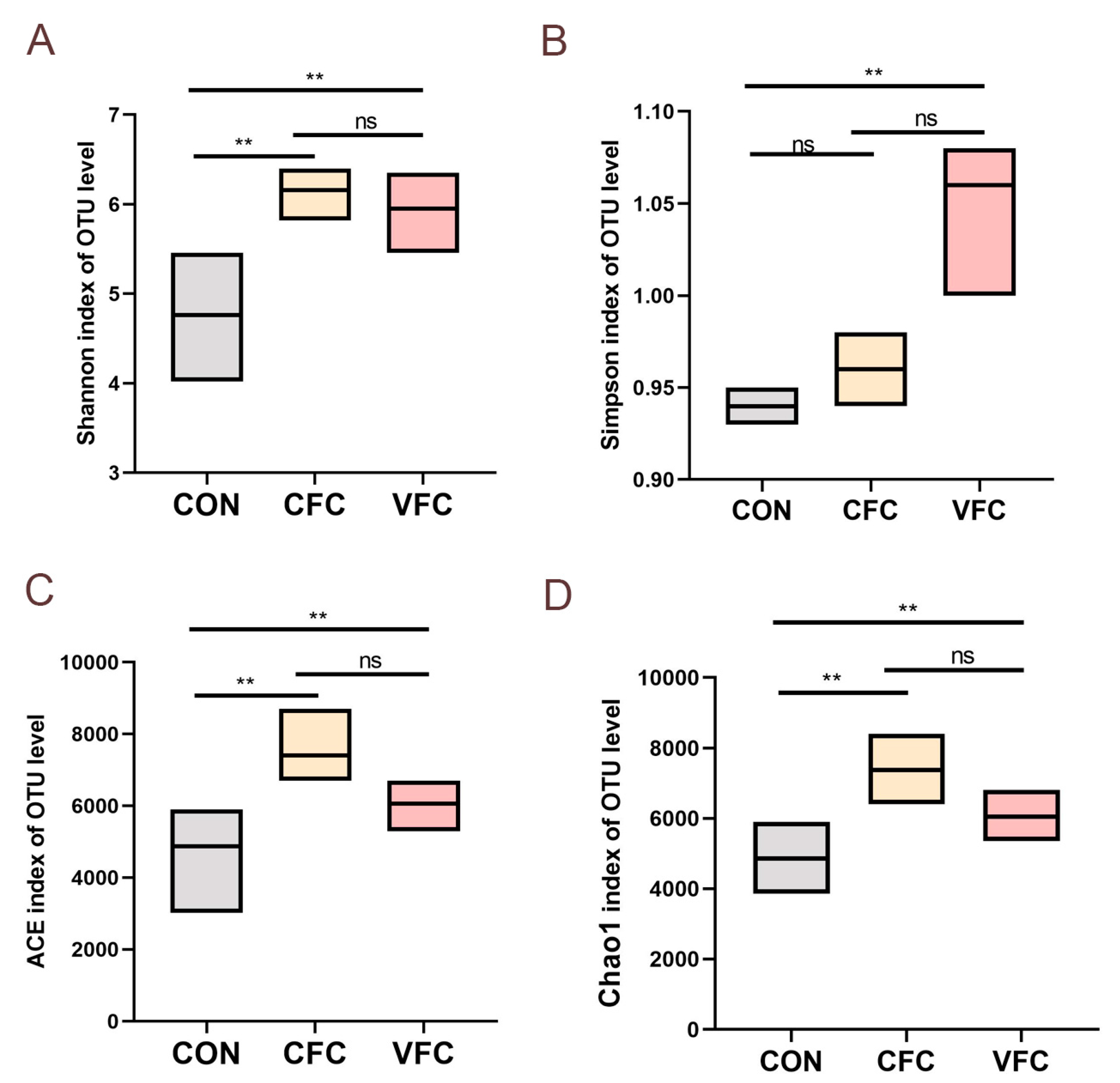

Herein, microbial genomic DNA was extracted from rumen contents using a QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen Ltd., Hilden, Germany). The total DNA from the sample was extracted, and the V3-V4 hypervariable region was amplified using primer 338F (5-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3) and 806R (5-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3). Equimolar quantities of purified amplicons were combined and subjected to paired-end sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq PE300 platform/NovaSeq PE250 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), following the established protocol of Majorbio Biopharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. The Uslust algorithm was used to cluster operational taxa (OTU) with a confidence threshold of 0.7. The Shannon index, Chao 1 index, and ace index were used to analyze the α diversity [

13].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Duncan’s multiple range test was applied to compare the significance of differences among treatment groups, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Meanwhile, normality and homogeneity of variance were tested using the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests, respectively. It should be noted that although the experiment was designed with 54 sheep allocated into three groups, only 3 sheep per group were selected for tissue sample collection.

4. Discussion

Abundant bioactive substances in vegetable leaves are beneficial for improving the production performance of ruminants and have been extensively studied [

15]. However, with the rise in national living standards, people’s demand for high-quality vegetables has also increased, so more discarded vegetables will be produced in the process of harvesting, storage, processing, loading and unloading, and transportation [

16]. Vegetables, as a kind of daily garbage, easily rot, rapidly spoil, and produce odor if not effectively treated in time, thereby causing greater pollution to the environment [

13]. Fermented feed enriches the content of probiotics, vitamins, organic acids, amino acids, polypeptides, enzymes, and growth-promoting factors. This feed-processing technology helps the digestion and absorption of nutrients by the host, thereby improving the growth performance of the animal [

17,

18]. Therefore, in this study, the mode of fermented feed was used to ferment the waste vegetable leaves, and the effect of fermented concentrated feed of vegetable leaves on sheep fattening was studied. The utilization rate of nutrient components in feed by animals determines the nutritive value of the feed. The better the degree of digestion and absorption of a specific nutrient by the animal’s gastrointestinal tract, the higher the digestibility of that nutrient will be. The results showed that compared with the CON group, the body weight and average daily gain of sheep were significantly increased, while the feed conversion ratio was significantly decreased by adding a vegetable-fermented feed. The above results indicate that fermented vegetable leaf concentrate can effectively improve the digestibility of nutrient substances in feed, thereby achieving the goal of enhancing the feed utilization rate.

The physiological function and metabolism of the body can be reflected by blood indicators involved in the physiological activities of the body through the circulatory system, and the blood components can also reflect the physiological and pathological changes in the animal body [

19,

20]. The health status of the body can be directly reflected by the content of triglycerides and cholesterol. Triglyceride is involved in the fat metabolism of the body. Generally speaking, the increase in triglycerides in the blood will promote the deposition of fat, leading to the occurrence of fatty liver and other diseases [

21,

22]. The decrease in triglyceride concentration indicates that the body’s utilization of fat increases and that the deposition of fat in the body decreases. Cholesterol is partly synthesized by the liver and partly provided by the diet [

23]. Fat in the diet is digested and absorbed to form fatty acids, galactose, and glycerol, a small part of which is absorbed by the small intestine into the blood. In this case, the composition of lipids in the diet plays an important role in regulating serum triglyceride and cholesterol levels. Herein, the content of triglyceride and cholesterol was significantly reduced in the fermented concentrated feed of vegetable leaves, which improved the health status of sheep and promoted their growth and development. It was also found that the glucose and urea nitrogen contents increased significantly with the addition of the vegetable leaf fermentation concentrate [

24]. The results showed that the addition of the concentrate of fermented vegetable leaves could improve the energy metabolism level of sheep, ensure the demand for rumen microorganisms, and promote the growth of animals. The possible reason for the increase in urea nitrogen content was that the protein content of the fermented concentrated feed of vegetable leaves was too high, so that the sheep’s body could not absorb it completely, indicating the necessity of further adjustment in the following experiment.

IgA, IgG, and IgM have been reported to be the key immune factors representing the immune level of sheep [

25]. An important component of mammalian humoral immunity is immunoglobulin, which can enhance the phagocytosis of mononuclear macrophages, thereby inhibiting the reproduction of viruses and harmful microorganisms [

26]. It was found that the levels of IgA, IgG, and IgM in the serum of sheep that were fed diets supplemented with vegetable-fermented feed were significantly increased. Through the above results, the addition of vegetable-fermented feed to the diet was found capable of improving the immune ability of sheep. In addition, oxidative stress is a common problem in sheep production, which seriously affects animal welfare and growth. A large number of studies have reported the existence of a variety of bioactive compounds in vegetable leaves, including bioactive substances and phenols [

27]. These ingredients generally feature good physiological activities such as sterilization, anti-inflammation, anti-oxidation, anti-radiation, anti-cancer, and so on. T-AOC is a comprehensive index that can reflect the antioxidant capacity of the antioxidant defense system in vivo and in vitro [

28]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging enzymes such as T-SOD can reduce superoxide free radicals and hydrogen peroxide in piglets [

29,

30]. Based on the above results, it was found that the addition of vegetable-fermented feed in the diet could improve the antioxidant capacity of sheep by resisting oxidative stress. Intestinal morphology matters considerably in nutrient absorption, intestinal health, growth, and development of ruminants during the growing period. It has been reported that the height of intestinal villi is closely related to the nutritional efficiency of ruminants, and the higher the height of intestinal villi, the faster the rate of nutrient absorption. Studies have also shown that the depth of intestinal crypts reflects the degree of intestinal damage, and that intestinal epithelial tissue is the key to intestinal barrier function, which responds to inflammation through cytokines. A previous study has also indicated that fermented feed improves the performance of ruminants by tending to prolong the villus height and V:C ratio, which is consistent with the present study. Herein, it was found that a fermented vegetable leaf diet increased the villus height and V:C ratio in the intestines of sheep. Therefore, the protective effect of fermented vegetable leaf feed on intestinal barrier function resulted in better growth performance and feed efficiency in sheep [

31].

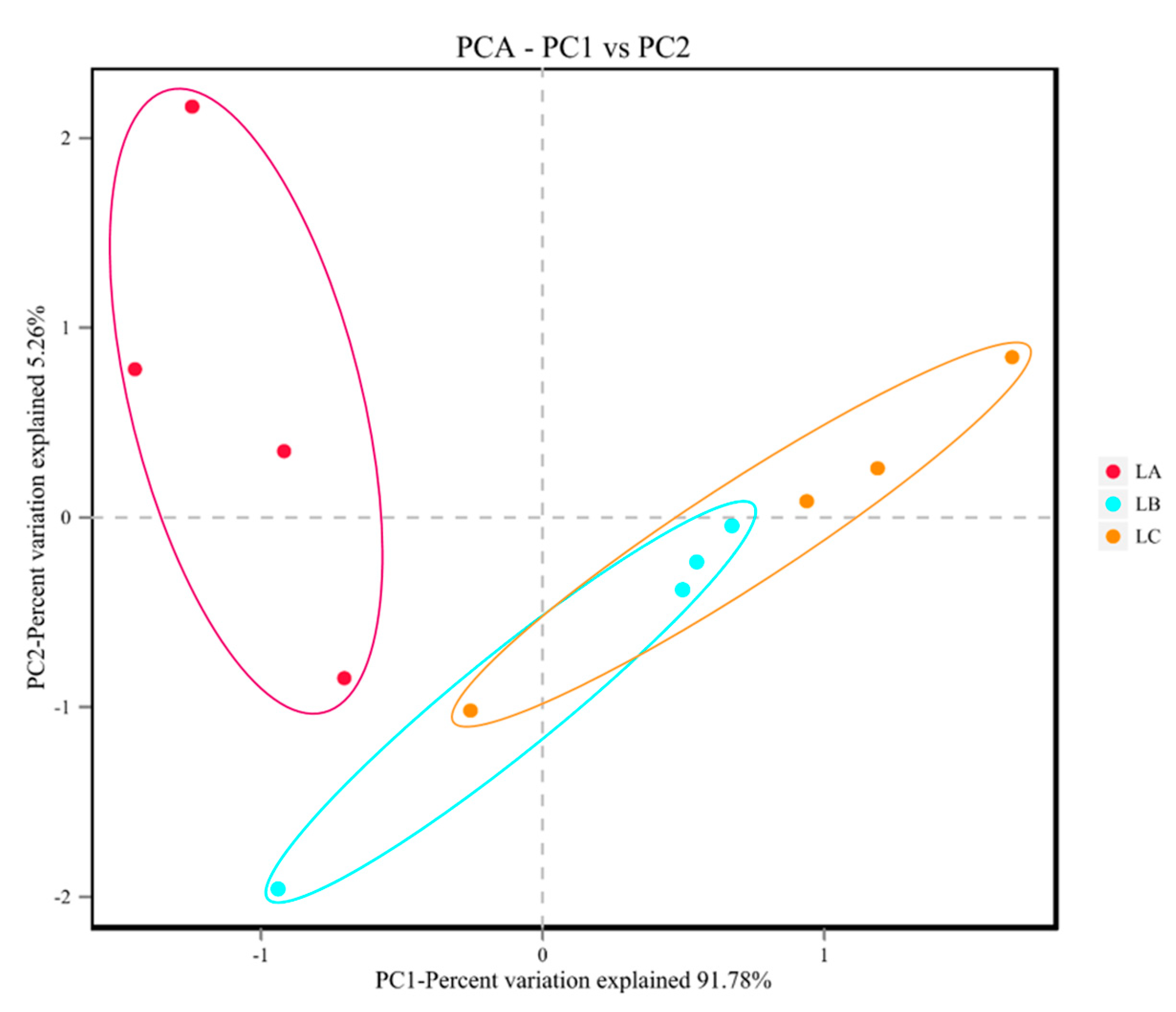

The determination of rumen microbial community composition not only clarifies ruminant physiology but also helps to precisely manage animal nutrition and improve feed conversion. Intestinal flora is closely related to the host’s digestion and absorption of nutrients and immune response. For example, Wang et al. observed that roughage type had a significant effect on rumen microorganisms and metabolites, thereby altering growth performance. Studies have also shown that fermented feed can change the intestinal flora of animals [

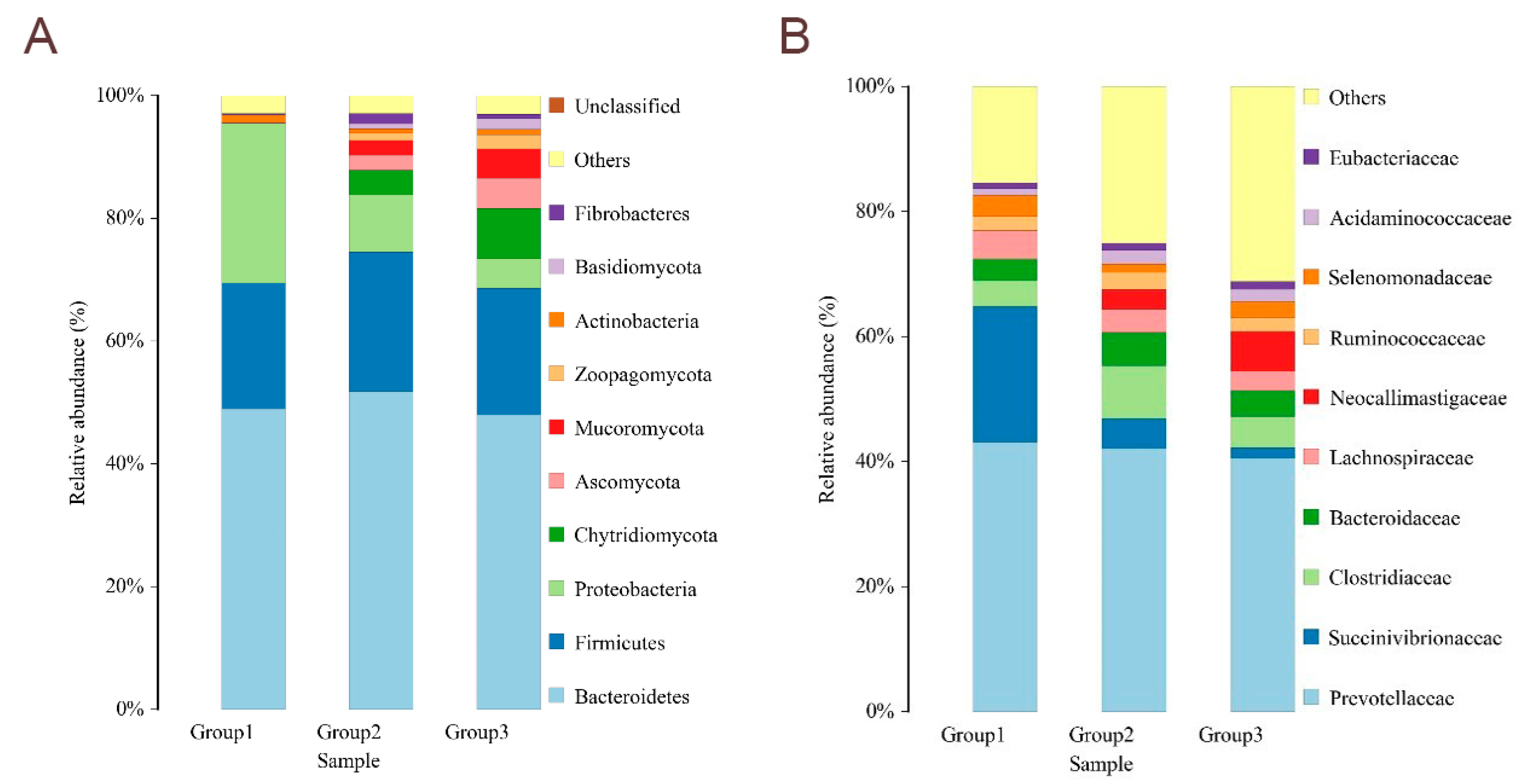

32]. However, the effects of fermented vegetable feed on intestinal microflora in sheep have been rarely investigated. To this end, a metagenomic sequencing approach was used to examine the rumen microbiome of sheep to assess any effects of the addition of vegetable-fermented feed to the diet. In this study, a decrease in ruminal microflora species, Shannon, Chao, and Ace indices was found in sheep-fed fermented diets, indicating an increase in ruminal microflora richness and diversity. In addition, the results of β-diversity showed that the gastrointestinal microbiota of the CFC and VFC groups were different from that of the CON group, which might also be related to the probiotic effect of fermented feed.

Bacteroidetes and

Firmicutes are associated with the digestion and decomposition of plant-derived diets by ruminants.

Bacteroidetes favor the digestion of complex carbohydrates, and

Firmicutes contribute to the digestion of fiber and cellulose [

33]. In this study, the relative abundance of

Firmicutes and

Bacteroidetes was increased by the fermented feed of vegetable leaves. Similarly to the present results, previous studies have shown that the addition of fermented feed can increase the relative abundance of

Firmicutes and

Bacteroidetes in ruminants [

34,

35,

36]. Meanwhile,

Prevotella is the main bacterium that degrades starch in the rumen of ruminants [

37].

Clostridium butyricum is the main

Clostridium in the gastrointestinal tract, which, as a probiotic in the gastrointestinal tract, stimulates mucosal immune response by fermenting cellulose and producing butyric acid, thus inhibiting the growth of intestinal pathogens [

38,

39]. It was found that the relative abundance of

Prevotella in the rumen of sheep was increased by the addition of fermented feed [

40,

41,

42].

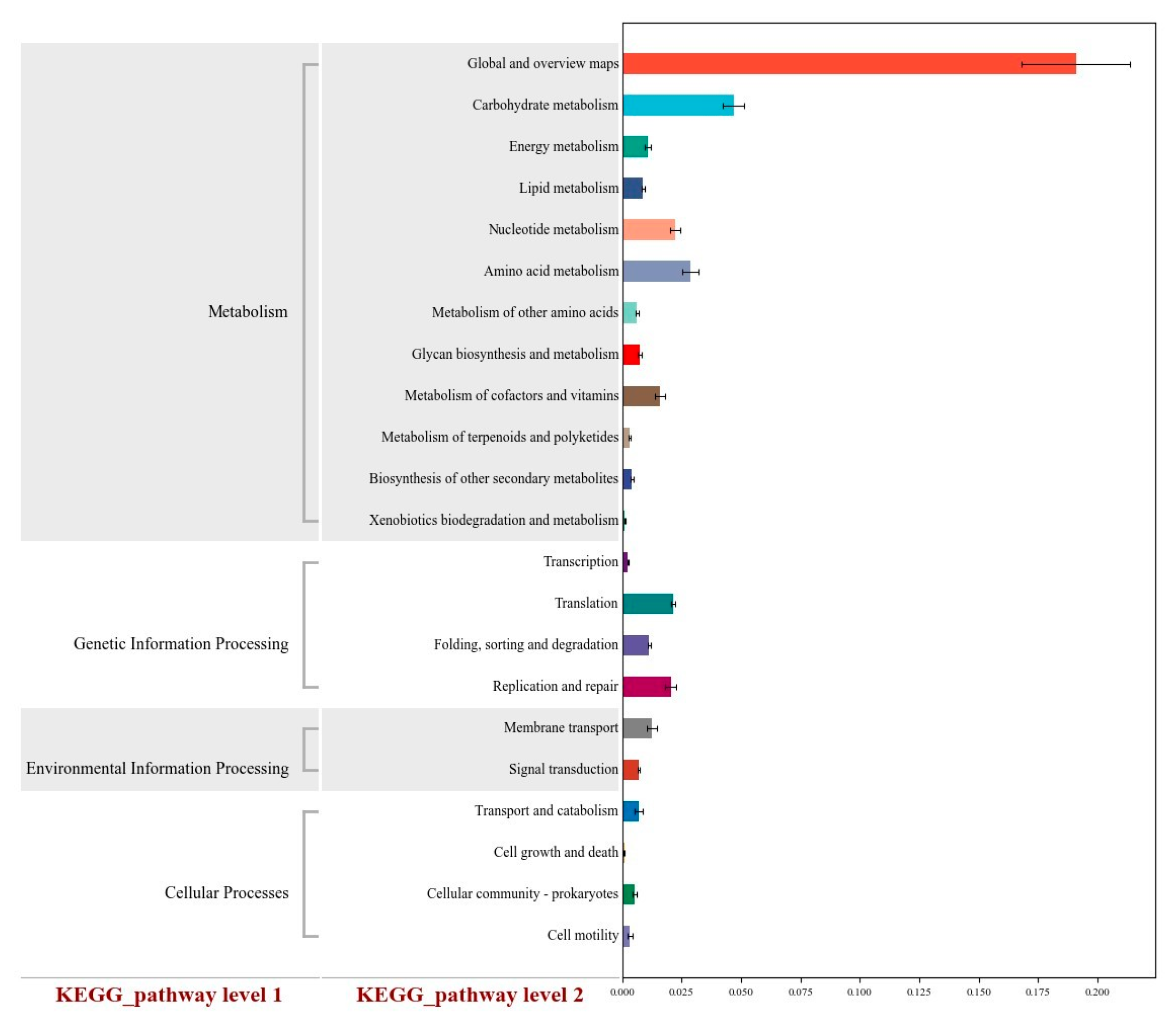

The KEGG functional prediction further confirms the metabolic mechanism underlying VFC’s beneficial effects. Compared with CON, the VFC group showed significantly higher enrichment in three key metabolic pathways: the carbohydrate metabolism pathway, the amino acid metabolism pathway, and the nucleotide metabolism pathway. The enrichment of the carbohydrate metabolism pathway activates the metabolic genes of core carbohydrate-degrading bacteria, optimizing the composition of VFAs and enhancing energy supply—this explains the higher ADG and lower FCR in the VFC group [

43]. The enrichment of the amino acid metabolism pathway enhances transamination and deamination processes, improving the conversion efficiency of non-protein nitrogen to microbial protein, reducing nitrogen loss, and providing sufficient amino acids for the synthesis of serum immunoglobulins [

44]. The enrichment of the nucleotide metabolism pathway provides raw materials for nucleic acid synthesis in beneficial microbes, supporting the increase in rumen microbial richness and diversity and consolidating the microbial foundation for nutrient utilization [

43,

44,

45]. These three pathways form a “metabolic network” that links microbial function, nutrient metabolism, and animal growth, providing a clear molecular mechanism for the comprehensive beneficial effects of VFC. While this study demonstrates the significant value of VFC in sheep husbandry, it also has a notable limitation: the high BUN level in the VFC group indicates incomplete protein absorption, which requires further optimization of VFC’s nutrient composition in future research. Future studies should also explore the long-term effects of VFC on sheep (such as meat quality and reproductive performance) and identify the specific bioactive components in VFC that drive its antioxidant and immune effects. Additionally, the molecular mechanism by which VFC regulates rumen microbial communities (e.g., signaling interactions between microbes and the intestinal barrier) requires further investigation using multi-omics approaches.