Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine fungal diversity and composition in an area of high host diversity and identify the organisms involved in the appearance of symptoms in Pinus needles. Asymptomatic and symptomatic live needle samples were obtained from different Pinus spp. in an arboretum with confirmed presence of brown spot needle blight. The samples were analysed using high-throughput sequencing of fungal ITS2rDNA. Ascomycota dominated all samples, with Lophodermium as the most abundant genus, although it showed lower representation in symptomatic needles. Other genera with recognised pathogenic potential, including Lecanosticta, Pestalotiopsis, Cyclaneusma, Rhizosphaera, Neophysalospora, and Cenangium, were also detected, whereas the Dothistroma genus was absent despite its presence in the region. Alpha diversity was higher in asymptomatic needles, with a significant difference only for the Shannon index, while Bray–Curtis dissimilarity revealed significant shifts in community composition between needle types. Functional guilds were dominated by pathotroph–saprotroph trophic mode, and the functional guild ‘plant pathogen’ was the most abundant across samples. These findings identify fungal genera associated with symptomatic and asymptomatic needles and provide guidance for future targeted isolation and detailed morphological and molecular identification using more resolutive techniques, enabling a deeper understanding of pathogenic community presence and their potential synergistic interactions.

1. Introduction

The frequency of needle disease outbreaks and their severity in Pinus L. spp. have increased over recent decades, likely triggered by climate change and cultural practices such as establishing large plantations of susceptible host species. Needle diseases may result in repeated premature needle loss, which gradually weakens the host, reduces timber yield, and leads to tree death in some cases [1,2,3]. The most significant needle pathogens in Pinus spp. are Dothistroma Hulbary spp., Lecanosticta acicola (Thüm.) Syd., Lophodermium Chevall. spp., Lophodermella Höhn., Phytophthora de Bary spp., and Cyclaneusma minus (Butin) DiCosmo, Peredo and Minter [4,5,6,7]. Among these, Dothistroma spp. are the most destructive pine foliar pathogens [8]. Their similar symptomatology has been associated with various needle diseases such as Dothistroma needle blight, brown-spot needle blight, Lophodermium needle cast, and Cyclaneusma needle cast that affect several conifer species [9].

Brown spot needle blight caused by L. acicola is one of the most important diseases in the Basque Country, where forestry is principally based on monospecific stands of Pinus radiata. The earliest record of L. acicola in Europe dates to 1942, when the pathogen was reported causing defoliation in the Basque Country [10]. At that time, it was observed exclusively on P. radiata D. Don grown under suboptimal conditions, and not on other locally assessed Pinus species [11]. Prior to 2008, disease outbreaks were largely confined to humid environments—particularly valley bottoms and high-density plantations—despite the widespread cultivation of P. radiata in the region. In subsequent years, the distribution and severity of L. acicola have increased markedly. Recent surveys have documented L. acicola infecting multiple Pinus species—including P. radiata, P. nigra Arnold, P. sylvestris L., P. ponderosa Douglas ex C. Lawson, P. elliottii Engelm., and P. brutia Ten.—highlighting the pathogen’s broad host range and colonisation versatility [12,13]. Furthermore, analyses using simple sequence repeat markers and whole-genome sequencing showed that this pathogen exhibited high genetic diversity in the region and confirmed the presence of northern and southern lineages of L. acicola [14,15]. The presence of its sexual form was also confirmed in the region [16].

Environmental and host-related factors determine the differences in fungal community composition, diversity, and richness [17,18]. Fungal interactions with their hosts depend on plant compounds, morphology, and life-history traits. Phylogenetically related host species show association with their mycobiomes [18,19,20,21]. This association or host specialisation may be stronger for pathogenic than for non-pathogenic fungi [18]. Additionally, several needle fungal pathogens spend part of their life cycle as endophytes or epiphytes without causing apparent damage, and visible infection is triggered under certain environmental conditions or when the hosts are weakened by stress [22,23,24,25,26,27].

In the absence of other feasible management methods, the selection of tolerant hosts such as resistant host species, subspecies, or hybrids is recommended for controlling the spread and impact of a pathogen [28]. However, adequate caution must be exercised when complexes of pathogenic fungi exist in a region because a host tolerant to a specific pathogen may still be susceptible to the other pathogens. The susceptibility of large plantations of non-native tree species to pathogens is associated with inadequate species/site matching, the use of individuals with a limited genetic base, and heavy reliance on one or two species in plantation strategies for a region [29]. Additionally, newly established exotic tree species may undergo a pest-free period of variable duration because of the absence of co-evolved pathogens in the area and the inability of native pathogens to adapt to the new hosts [29,30]. Thus, building resilient forest ecosystems requires more effort than the mere introduction of new tree provenances or species. Consequently, a high level of host genetic diversity is a key requirement in both plantations and native forests to assimilate and adapt to adverse conditions such as climate change and diseases [31].

Plants in arboreta and botanical gardens (sentinel species) are important resources for detecting newly introduced pathogens and identifying potential risks resulting from novel pest–host interactions [32] or native pest–exotic forest species interactions. However, arboreta usually contain representative tree species in small numbers; hence, the issues related to extensive plantations may go unnoticed [33]. Nevertheless, the results from arboreta regarding the suitability of new exotic tree species for a region may be useful, albeit preliminary. This is especially true if the experimental sites are located in areas of high exposure to pathogens and representative of the environmental conditions of the region [33].

This study aimed to characterise the fungal diversity and composition in symptomatic and asymptomatic needles of Pinus spp. using high-throughput sequencing of the ITS2 region. We hypothesised that symptomatic needles would host distinct fungal community structures, including higher representation of genera with pathogenic potential, and expected that these differences would help identify fungal genera of interest for future isolation and high-resolution morphological and molecular identification.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Sampling

The study site was located in the Umbemendi2 arboretum (AR19) (43°21′05.3″ N, 2°55′47.4″ W) at Laukiz, Biscay, Basque Country, Spain. This arboretum was planted between 2011 and 2013 on a harvested P. radiata plantation as part of the European project REINFFORCE (https://www.efi.int/projects/reinfforce-resource-infrastructures-monitoring-adapting-and-protecting-european-atlantic) (accessed on 26 December 2025). During establishment, the trees were labelled with IDs to facilitate identification. The arboretum is currently surrounded by plantations of P. radiata, P. nigra, and Eucalyptus L’Hér. spp., and native deciduous forest that primarily comprises the Quercus genus. The stand is north-oriented with a 5% slope and cambisol soil. The mean annual temperature of the area is 14 °C, with a mean of 6.2 °C in the coldest month, and the average annual precipitation is 1233 mm.

Samples were collected from nine Pinus species. Of these, P. brutia Ten., P. elliottii Engelm., P. nigra Arnold, P. pinaster Ait., P. pinea L., P. ponderosa Douglas ex C. Lawson, P. sylvestris L., and P. taeda L. were planted in the arboretum and were 12 years old at the time of sample collection. The P. radiata D. Don. trees were located at the border of the arboretum because the P. radiata species was not chosen as part of the REINFORCE arboreta. The selected P. radiata were approximately 15 years old during sampling. Two groups of needle samples were collected from the lower parts of five trees for each Pinus species. One group comprised needles showing symptoms of fungal defoliators (discolouration, spots, bands, or dead tips), and the other group comprised asymptomatic needles. Samples from the same Pinus species and group (asymptomatic or symptomatic) were combined and stored at 4 °C in paper envelopes overnight before DNA extraction. The needles were cut with sterilised scissors into approximately 0.5 cm pieces, and the needle tissue disruption was performed in a Qiagen Tissuelyser II (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany) with sterile metal beads (Ø 2.5 mm). DNA was extracted from approximately 100 mg of the needle powder using the innuPREP Plant DNA Mini Kit (Analytik Jena AG, Jena, Germany).

2.2. Illumina Library Construction, Sequencing, and Data Processing

The internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) region of the nuclear ribosomal DNA was used as a DNA barcoding marker for the molecular identification of fungal taxa using the universal primers ITS86 (F): GTGAATCATCGAATCTTTGAA [34] and ITS4 (R): TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC [35], both of which contain Illumina adapter sequences. The PCR cycle conditions were: 5 min at 95 °C; 40 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, and 72 °C for 1 min; and final extension for 7 min at 72 °C. Each PCR reaction contained 25 µL of Master Mix Supreme NZYTaq II 2X colourless (NZYTech, Lisbon, Portugal), 0.5 µM primers, and 2 µL of DNA at a final volume of 50 µL. PCR amplification was performed in triplicate for each sample.

Library construction, DNA amplification, assemblage of paired-end reads, filtering of bad quality sequences, and sequence clustering of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were performed by Macrogen, Inc. Library construction and DNA amplification were performed using the Herculase II Fusion DNA Polymerase Nextera XT Index Kit V2 by following the Illumina 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation Protocol (Part #15044223, Rev. B). Paired-end sequencing (2 × 301 bp) was performed using the MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

Paired-end reads from each sample were assembled using FLASH 1.2.11 [36] with default parameters. Reads were filtered with a quality score offset of 33, and low-quality, ambiguous, and chimeric sequences were removed. The remaining sequences were clustered into OTUs at a 97% similarity threshold using the CD-HIT-OTU software v.4.8.1 [37].

To classify the representative sequences in QIIME2 2024.2 [38], a Naïve Bayes classifier was trained using the “qiime feature-classifier fit-classifier-naive-bayes” command with the UNITE all eukaryotes developers dataset v10 (04.04.2024) [39], which included singletons set as RefS (in dynamic files) using the “qiime feature-classifier classify-sklearn” command [40]. Unclassified OTUs and those not belonging to the kingdom Fungi, such as Viridiplantae, Rhizaria, Alveolata, and Eukaryota_kingdom_Incertae_sedis, were removed from the dataset using the “qiime taxa filter-table” command.

Technical replicates were merged in the dataset by mean (with qiime feature-table group command and parameter “mode” set as mean-ceiling), and features with fewer than 10 counts were removed using “qiime feature-table filter-features” to minimise the inflation of rare OTUs in community analysis [41,42].

Fungal OTUs were assigned to trophic modes and guilds using the FUNGuild.py Python script v1.0 [43]. Assignments were retained only if they reached the ‘Probable’ or ‘Highly Probable’ confidence ranking. Trophic modes were defined as follows: pathotrophs obtain nutrients by harming host cells (including phagotrophs); symbiotrophs receive nutrients by exchanging resources with host cells; and saprotrophs acquire nutrients by breaking down dead host cells [43]. Functional guilds were constrained to the following categories: undefined saprotrophs, plant saprotrophs, and plant pathogens.

2.3. Community Analysis

Community analysis was performed using QIIME 2 2024.2 [38]. Rarefaction curve analysis was performed on the dataset (via the “qiime diversity alpha-rarefaction” command), and the OTU table was rarefied to the smallest library size (sequence depth of 93,316) via the “qiime feature-table rarefy” command for downstream community diversity analysis to minimise the biases associated with different sample sizes. Alpha diversity was calculated using observed OTUs, Shannon’s index, and Simpson’s index (1-D) (with the “qiime diversity alpha” command). Significant differences were determined using the Kruskal–Wallis test (p < 0.05) (with the “qiime diversity alpha-group-significance” command). Beta diversity was calculated using the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity index and Jaccard similarity index (by the “qiime diversity core-metrics” command). Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) [44] was used to test the association between fungal beta diversity and needle status (via the “qiime diversity beta-group-significance” command). For significant PERMANOVA results, differences in community dispersion were checked using PERMDISP [45] because PERMANOVA results may be affected by beta dispersion. Data of the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity and Jaccard similarity distance matrices generated in QIIME2 were used to perform principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) in R-4.4.2. PCoA images were generated with tidyverse [46] and qiime2R v0.99 [47]. https://github.com/jbisanz/qiime2R packages (accessed on 26 December 2025).

Analysis of microbiome compositions with bias correction (ANCOMBC) [48] was applied to identify taxa that were differentially abundant between asymptomatic and symptomatic needles at the genus and family levels using the “qiime composition ancombc” command. Owing to the small sample size, a conservative variance estimator was used for the test statistics. OTUs with Holm-adjusted p < 0.05 were considered significant. Graphic representations of ANCOMBC results were obtained using the “qiime composition da-barplot” command.

3. Results

3.1. Sequencing Data and Relative Abundance of Fungal OTUs

High-throughput sequencing of the ITS2 region of the nuclear ribosomal DNA yielded a total of 9,432,191 reads with a mean of 184,945 reads per sample. After quality evaluation, 7,012,105 clean reads were obtained with a mean of 137,492 ± 16,352 reads per sample at a range of 106,871–176,920 reads. In total, 3227 OTUs were generated. Non-fungal and low-frequency OTUs were filtered to yield 1338 OTUs.

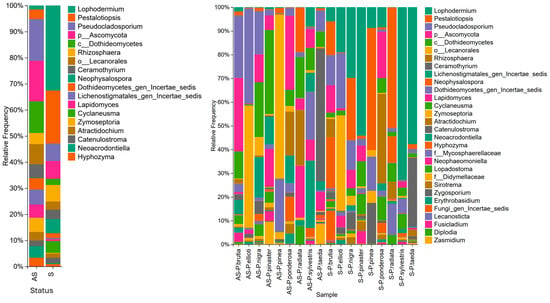

The majority (87%) of fungal OTUs were assigned to Ascomycota, and 11% were assigned to Basidiomycota. The most abundant OTUs belonged to the family Rhytismataceae. The genus Lophodermium showed the highest presence and accounted for 22.2% of the OTUs in symptomatic needles and 0.9% in asymptomatic needles (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(Left): Relative abundance of fungal genera by sample status: asymptomatic (AS) and symptomatic (S). (Right): Relative abundance of fungal genera by sample status: asymptomatic (AS), symptomatic (S), and pine species.

OTUs classified as Pestalotiopsis sp. were highly abundant in symptomatic samples (13.34%) than in asymptomatic samples (2.01%). They were abundant in symptomatic samples of P. pinea (37.7%), P. nigra (21.1%), P. brutia (12.2%), and P. radiata (42%). Additionally, Rhizosphaera was abundant (2.3% in asymptomatic and 4.1% in symptomatic samples) in symptomatic (31.8%) and asymptomatic (15.8%) P. ponderosa samples and symptomatic (6.6%) and asymptomatic (1.4%) P. brutia samples (Figure 1).

Neophysalospora was more abundant in symptomatic samples (3.5%) than in asymptomatic samples (0.04%) and was primarily detected in high abundance in symptomatic needles of P. pinea (1% of OTUs), P. brutia (18% of OTUs), and P. radiata (9% of OTUs). The relative abundance of Cyclaneusma was higher in symptomatic (3%) than in asymptomatic needles (0.03%), with higher relative abundances in symptomatic needles of P. pinaster (6.1% of OTUs), P. sylvestris (4.7% of OTUs), P. ponderosa (8.4% of OTUs), and P. radiata (7.6% of OTUs) (Figure 1).

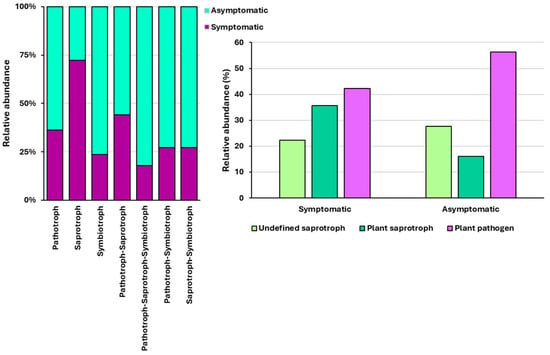

Trophic modes and functional guilds were successfully assigned to 752 OTUs (77.3%) using FUNGuild. The remaining OTUs were unassigned because they were not identified at the genus level. In both asymptomatic and symptomatic needles, trophic mode pathotroph–saprotroph represented the largest proportion (40.5%), followed by saprotroph (36.7%) and pathotroph (12%). When comparing asymptomatic and symptomatic needles, all trophic modes were higher in asymptomatic needles, except for the saprotroph mode. Plant pathogens were the most abundant in both symptomatic and asymptomatic needles, whereas plant saprotrophs were the least abundant in asymptomatic needles and undefined saprotrophs in symptomatic needles (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relative abundance of identified trophic modes (left) and functional guilds (right) in asymptomatic and symptomatic needles.

3.2. Community Analysis

3.2.1. Rarefaction Curves and Diversity Analysis

Rarefaction curves generated by plotting Shannon and Simpson diversity metrics against sequencing depth levelled off in all samples before reaching the sequence depth chosen to rarefy the OTU table for diversity analysis. This finding indicated that fungal diversity was adequately represented. In contrast, the rarefaction curves for the observed OTUs did not reach a plateau in any of the samples, which indicated that rare species may not have been adequately represented.

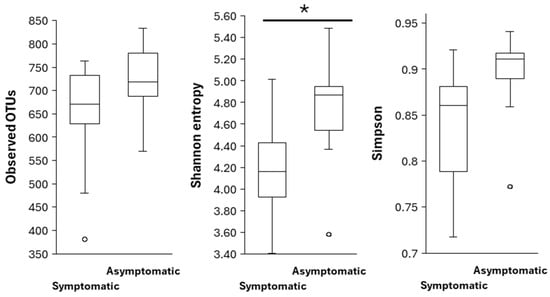

After data rarefaction (at sampling depth of 93,316), a mean of 608 observed OTUs per sample was obtained, ranging from 381 to 780. The highest number of OTUs was detected in asymptomatic needles of P. brutia, and the lowest in symptomatic needles of P. pinea. However, the difference in OTUs between the asymptomatic and symptomatic needles of Pinus spp. was not significant (H = 1.76; p = 0.18). The Shannon diversity index, which emphasises richness, suggested that fungal communities from symptomatic needles were significantly less diverse than those from asymptomatic needles (H = 4.31; p = 0.038). The Simpson diversity index, which emphasises evenness, indicated no significant difference between the fungal communities in the asymptomatic and symptomatic needles (H = 2.96; p = 0.085) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Alpha diversity indices in symptomatic and asymptomatic Pinus spp. needles. (*) indicates a significant difference (p < 0.05) based on the Kruskal–Wallis test. Left: Observed OTUs; Middle: Shannon entropy; Right: Simpson.

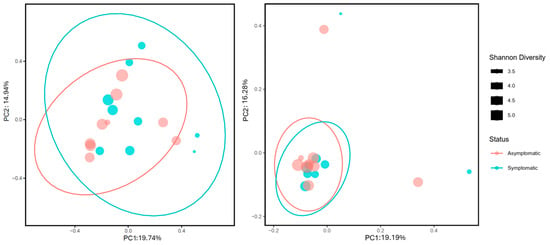

With respect to beta-diversity metrics, the PERMANOVA result for Bray–Curtis dissimilarity (fraction of overabundant counts) was significant (pseudo-F = 1.748; p = 0.032), whereas the Jaccard similarity index (fraction of unique features regardless of abundance) was not significant (pseudo-F = 0.781; p = 0.793) (Figure 4). Analysis of beta dispersion (PERMDISP) was not significant for Bray–Curtis distances (p = 0.7), which indicated that the significant differences obtained through PERMANOVA were due to differences between symptomatic and asymptomatic needle fungal communities and not because of differences in dispersion within the groups.

Figure 4.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of fungal communities associated with asymptomatic (red) and symptomatic (blue) needles of Pinus spp. based on beta diversity metrics: Bray–Curtis (left) and Jaccard (right). Confidence ellipses were calculated at 95%. Circle size indicates the Shannon diversity index. Values of the Shannon diversity index correspond to the size of the black squares present in the right.

3.2.2. Differential Abundance Analysis of Taxa

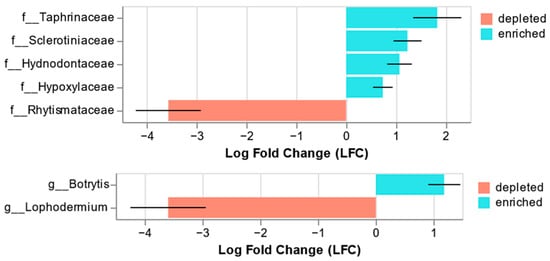

Analysis of microbiome composition with bias correction (ANCOMBC) showed significant differences between organisms in asymptomatic and symptomatic needles at the fungal genus and family levels (Figure 5). At the family level, Rhytismataceae was significantly depleted in asymptomatic needles (q = 0.00001), and Taphrinaceae (q = 0.04), Sclerotiniaceae (q = 0.003), Hydnodontaceae (q = 0.004), and Hypoxylaceae (q = 0.046) were significantly enriched. At the genus level, Lophodermium was significantly depleted in asymptomatic needles (q = 0.00002), whereas Botrytis was significantly enriched (q = 0.01).

Figure 5.

Significant results from the ANCOM-BC. Significant differences in relative abundance (q < 0.05) at the family (top) and genus (bottom) levels are shown. Negative LFC values indicate a decrease in the relative abundance of fungal taxa in asymptomatic needles compared with that in symptomatic needles, whereas positive values indicate an increase.

4. Discussion

We performed high-throughput sequencing of the ITS region of fungal rDNA and compared the fungal communities of symptomatic and asymptomatic needles collected from different Pinus species at an arboretum in Biscay, northern Spain, that was severely affected by pine needle blight.

Ascomycota was identified as the predominant phylum in the analysed needles, and this trend was observed in other conifer mycobiome studies [49,50,51,52,53]. The most abundant pathogens belonged to the family Rhytismataceae. Several species in this family are considered potential primary or opportunistic pathogens of conifers, especially in Pinus spp. Depending on their pathogenic capacity, they cause premature needle loss (needle cast) or sudden foliar death (needle blight) [25,54]. Lophodermium was the most abundant fungal genus, especially in symptomatic needles, and was the only fungal genus that was significantly depleted in asymptomatic needles. Lophodermium species are considered weak pathogens, with the exception of L. seditiosum, which causes severe damage to nurseries and plantations [25]. Additionally, L. pinastri and L. conigenum belong to the Lophodermium genus. L. pinastri is a non-pathogenic endophyte that actively develops at the beginning of needle senescence and damages the weakened or dead needles [25,50]. However, a P. radiata selection trial in Tasmania showed that this species was the only one that correlated with high levels of needle cast [55]. Generally, L. conigenum is considered a weak pathogen, although it has been associated with disease symptoms in P. mugo and P. taeda [56,57]. Additionally, it is often present in New Zealand P. radiata trees previously affected by Cyclaneusma minus. Furthermore, the impact of certain species is worse in nurseries than in plantations [54].

Pestalotiopsis spp. were detected in all analysed samples. They showed high relative abundance, especially in symptomatic needles of P. pinea, P. nigra, P. brutia, and P. radiata. The significance of Pestalotiopsis species is increasing in temperate forests. They usually act as secondary pathogens that cause severe damage to different plant structures [50]. Furthermore, they are associated with the decline of P. pinea and considered a potential threat to the health of pine forests in the Mediterranean Basin [26]. Cyclaneusma was present in all samples except in symptomatic needles of P. pinea. This pathogen is distributed worldwide; however, it is particularly damaging to P. radiata plantations [27]. Its pathogenicity is highly variable and strongly dependent on the host genotype [58]. Rhizosphaera was identified in all Pinus species analysed in this study. Neophysalospora was more abundant in symptomatic samples of P. pinea, P. nigra, and P. radiata. This genus contains only one fungal species, N. eucalypti, which is a pathogen associated with brown leaf spots in eucalyptus plantations [59]. Previously, N. eucalypti was isolated from symptomatic needles of P. radiata trees located in Cantabria, Spain [60]. Lecanosticta was identified in P. pinaster, P. brutia, P. elliotti, P. ponderosa, P. radiata, and P. taeda; however, only the P. radiata needles showed a high relative abundance of this pathogen.

One OTU identified as Botrytis was present in all the samples analysed, and it was the only significantly enriched genus in asymptomatic needles. This genus contains approximately 30 species, with B. cinerea being the most studied member. This species has shown potential to switch between different lifestyles: facultative endophytic to necrotrophic behaviour. It has been reported as a pathogen in several Pinus species. Other species in the Botrytis genus show an endophytic lifestyle with facultative necrotrophy or non-pathogenic associations [61]. Thus, further determination of the Botrytis species in the study area could clarify its possible role in Pinus needles.

Coexistence of pathogens causes pine needle damage [50,56,57,60,62]. Early mutualistic associations may shift toward competitive dynamics, in which the superior species becomes dominant because of the potential differences in nutritional requirements, substrate suitability, production of antifungal compounds, or favourable climatic conditions. This may be attributed to the fact that fungal interactions are highly context-dependent and shaped by factors such as host and pathogen genotype and composition of the surrounding fungal community [50]. Domination of C. minus and L. pinastri in association with lower fungal diversity was observed in Pinus sylvestris symptomatic and asymptomatic needles, and we concluded that Cyclaneusma needle cast in Poland may be caused by C. minus, accompanied by C. ferruginosum, L. seditiosum, L. pinastri, and Sydowia polyspora [50]. White pine needle damage is a disorder in Pinus strobus and was principally associated with Lecanosticta acicola, in addition to other needle cast fungi, including Lophophacidium dooksi and Bifusella linearis [62]. In this study, Lophodermium and Pestalotiopsis were predominant in symptomatic needles, although they were also present in asymptomatic needles. The other fungi associated with symptomatic needles were Neophysalosphora and Cyclaneusma, although their relative frequency highly varied in the different analysed host species.

Fungal community characteristics were analysed in symptomatic and asymptomatic needles. Alpha diversity indices were higher in asymptomatic needles, although only the Shannon index was statistically significant. Bray–Curtis dissimilarity (fraction of overabundant counts) was significant between symptomatic and asymptomatic needles, whereas the Jaccard similarity index (fraction of unique features regardless of abundance) was not significant. Additionally, the Bray–Curtis index was significant when the structure of endophytic fungal communities was studied in healthy and symptomatic needles of Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica [46]. This trend towards increased fungal community diversity in asymptomatic needles has been reported previously [49,63]. This may be attributed to the dominance of certain pathogens that outcompete other species or environmental changes that favour pathogenic growth [49]. In contrast, the opposite trend was observed for fungal community richness in P. taeda needles, which may be attributed to opportunistic pathogens and saprophytes invading the weakened or dead tissues [57].

In the current study, the trophic mode pathotroph–saprotroph represented the largest proportion in both asymptomatic and symptomatic needles, and the functional guild ‘plant pathogen’ was the most abundant in symptomatic and asymptomatic needles. The high proportion of plant pathogens detected in symptomless needles may be explained by the presence of latent pathogens that remain dormant until favourable conditions arise [49]. Additionally, fungi classified as parasites of fungi were detected. For example, Tremella was present in all but one of the analysed samples. Previous studies have found members of this genus parasitising Lophodermium spp. [64,65,66].

Environmental DNA metabarcoding is an effective tool for detecting pathogens, including those at dormant or latent stages, and causing no visible symptoms [24,50,53]. Additionally, it enables the detection of slow-growing microorganisms and those that are unable to grow on artificial culture media [67]. This technique enables the detection and determination of fungal, bacterial, and Oomycete diversity in forest samples, thereby facilitating the development of anticipatory and robust management strategies [67]. The introduction of new tree species, as is happening in the Basque Country as a result of the damage caused by brown spot needle blight in P. radiata plantations, may be associated with ecological impacts caused by the introduction of new pathogens or the adaptation of native pathogens to exotic hosts [29]. The first screening using environmental DNA metabarcoding may be helpful in detecting several of these interactions.

In the present study, none of the sampled Pinus spp. showed Dothistroma species, which are the causal agents of red band needle blight. This result is consistent with a survey conducted in 2020 in the same arboretum, where the pathogen was not detected using conventional PCR or by obtaining isolates from needles of the same Pinus spp. [12]. However, damage caused by Dothistroma species has been reported in the Basque Country. The previously mentioned survey found that Dothistroma septosporum was present in the needles of P. brutia, P. ponderosa, and P. nigra collected from different arboreta. These findings highlight the need to include multiple study areas and larger sample sizes per tree species to obtain a reliable representation of the regional situation. Similarly, Fusarium circinatum was not detected in the present study, although this quarantine pathogen was present in wood samples, roots, and asymptomatic herbaceous and shrubby plants in the P. radiata plantation that existed prior to the establishment of the arboretum [68].

5. Conclusions

In summary, the results demonstrated that alpha diversity indices were higher in asymptomatic needles than in symptomatic needles. The Bray–Curtis dissimilarity index indicated significant differences between symptomatic and asymptomatic needles. Moreover, the trophic mode pathotroph–saprotroph represented the largest proportion in both asymptomatic and symptomatic needles, and the functional guild ‘plant pathogen’ was the most abundant in both symptomatic and asymptomatic needles. The high presence of plant pathogens in symptomless needles may be explained by the presence of latent pathogens that remain dormant until favourable conditions arise. The genus Lophodermium showed the highest abundance, particularly in symptomatic needles, and was the only fungal genus that was significantly depleted in asymptomatic needles. Notably, we did not detect the presence of Dothistroma species, which is a well-known pathogen in the region. This confirms the need for including additional sampling sites to obtain a reliable characterisation of the fungal communities in the area. Future studies must include a broader range of representative samples per tree species to further refine our understanding of host-driven shifts in fungal communities and strengthen the foundation for sustainable forest management under emerging disease threats.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M. and E.I.; methodology, N.M. and E.I.; software, N.M. and E.I.; validation, N.M., J.A. and E.I.; formal analysis, N.M. and E.I.; investigation, N.M., and E.I.; resources, N.M., J.A. and E.I.; data curation, N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M., J.A. and E.I.; writing—review and editing, N.M., J.A. and E.I.; visualisation, N.M. and E.I.; supervision, N.M., J.A. and E.I.; project administration, N.M., J.A., A.U. and E.I.; funding acquisition, N.M., J.A., A.U. and E.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research acknowledges funding from the following organisations: Forest Growers’ Research from New Zealand (FGR), project NZ FAMILIES 21-00055; Interreg VI-A POCTEFA programme (grant no. SANASILVA-EFA052/01) and PLANFORLAB (FEADER, MAPA). https://planforlab.es/en/ (Accessed on 26 December 2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This Targeted Locus Study project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession KJKG00000000. The version described in this paper is the first version, KJKG01000000. The project metadata is organised under the BioProject identifier PRJNA1393052.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Dr Jenny Aitken is the sole owner and managing director of the consulting company Jenny Aitken Biotechnologies Limited and has no conflict of interest to declare. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Tubby, K.; Adamčikova, K.; Adamson, K.; Akiba, M.; Barnes, I.; Boroń, P.; Bragança, H.; Bulgakov, T.; Burgdorf, N.; Capretti, P.; et al. The Increasing Threat to European Forests from the Invasive Foliar Pine Pathogen, Lecanosticta acicola. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 536, 120847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, C.; Lewis, K.; Woods, A. The Outbreak History of Dothistroma Needle Blight: An Emerging Forest Disease in Northwestern British Columbia, Canada. Can. J. For. Res. 2009, 39, 2505–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyka, S.A.; Smith, C.; Munck, I.A.; Rock, B.N.; Ziniti, B.L.; Broders, K. Emergence of White Pine Needle Damage in the Northeastern United States Is Associated with Changes in Pathogen Pressure in Response to Climate Change. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvira-Recuenco, M.; Cacciola, S.O.; Sanz-Ros, A.V.; Garbelotto, M.; Aguayo, J.; Solla, A.; Mullett, M.; Drenkhan, T.; Oskay, F.; Aday Kaya, A.G.; et al. Potential Interactions between Invasive Fusarium circinatum and Other Pine Pathogens in Europe. Forests 2019, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansons, Ā.; Zeltiņš, P.; Donis, J.; Neimane, U. Long-Term Effect of Lophodermium Needle Cast on The Growth of Scots Pine and Implications for Financial Outcomes. Forests 2020, 11, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, M.A.; Williams, N.M.; Bader, M.K.-F.; Gardner, J.F.; Bulman, L.S. Pathogenicity of Phytophthora pluvialis to Pinus radiata and Its Relation with Red Needle Cast Disease in New Zealand. N. Z. J. For. Sci. 2014, 44, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, A.; Gryzenhout, M.; Slippers, B.; Ahumada, R.; Rotella, A.; Flores, F.; Wingfield, B.D.; Wingfield, M.J. Phytophthora pinifolia sp. nov. Associated with a Serious Needle Disease of Pinus radiata in Chile. Plant Pathol. 2008, 57, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenkhan, R.; Tomešová-Haataja, V.; Fraser, S.; Bradshaw, R.E.; Vahalík, P.; Mullett, M.S.; Martín-García, J.; Bulman, L.S.; Wingfield, M.J.; Kirisits, T.; et al. Global Geographic Distribution and Host Range of Dothistroma Species: A Comprehensive Review. For. Pathol. 2016, 46, 408–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednářová, M.; Dvořák, M.; Janoušek, J.; Jankovský, L. Other Foliar Diseases of Coniferous Trees. In Infectious Forest Diseases; Gonthier, P., Nicolotti, G., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2013; pp. 458–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.B. Las Micosis Del Pinus Insignis En Guipúzcoa. Publ. Investig. For. Investig. Exp. 1942, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Michel Rodríguez, M. El pino Radiata en la Historia Forestal Vasca: Análisis de un Proceso de Forestalismo Intensivo; Sociedad de Ciencias Aranzadi: Donostia, Spain, 2006; Volume 247. [Google Scholar]

- Mesanza, N.; Raposo, R.; Elvira-Recuenco, M.; Barnes, I.; Nest, A.; Hernández, M.; Pascual, M.T.; Barrena, I.; San Martín, U.; Cantero, A.; et al. New Hosts for Lecanosticta acicola and Dothistroma septosporum in Newly Established Arboreta in Spain. For. Path. 2021, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortíz De Urbina, E.; Mesanza, N.; Aragonés, A.; Raposo, R.; Elvira-Recuenco, M.; Boqué, R.; Patten, C.; Aitken, J.; Iturritxa, E. Emerging Needle Blight Diseases in Atlantic Pinus Ecosystems of Spain. Forests 2016, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesanza, N.; Barnes, I.; Van Der Nest, A.; Raposo, R.; Berbegal, M.; Iturritxa, E. Genetic Diversity of Lecanosticta acicola in Pinus Ecosystems in Northern Spain. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcet-Houben, M.; Cruz, F.; Gómez-Garrido, J.; Alioto, T.S.; Nunez-Rodriguez, J.C.; Mesanza, N.; Gut, M.; Iturritxa, E.; Gabaldon, T. Genomics of the Expanding Pine Pathogen Lecanosticta acicola Reveals Patterns of Ongoing Genetic Admixture. mSystems 2024, 9, e00928-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesanza, N.; Hernández, M.; Raposo, R.; Iturritxa, E. First Report of Mycosphaerella dearnessii, Teleomorph of Lecanosticta acicola, in Europe. Plant Health Prog. 2021, 22, 565–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Wei, P.; Sun, N.; Wen, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, D.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, X. Differences Between Microbial Communities of Pinus Species Having Differing Level of Resistance to the Pine Wood Nematode. Microb. Ecol. 2022, 84, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franić, I.; Allan, E.; Prospero, S.; Adamson, K.; Attorre, F.; Auger-Rozenberg, M.-A.; Augustin, S.; Avtzis, D.; Baert, W.; Barta, M.; et al. Climate, Host and Geography Shape Insect and Fungal Communities of Trees. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, G.S.; Magarey, R.; Suiter, K.; Webb, C.O. Evolutionary Tools for Phytosanitary Risk Analysis: Phylogenetic Signal as a Predictor of Host Range of Plant Pests and Pathogens. Evol. Appl. 2012, 5, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeralo, C.; Martín-García, J.; Martínez-Álvarez, P.; Muñoz-Adalia, E.J.; Gonçalves, D.R.; Torres, E.; Witzell, J.; Diez, J.J. Pine Species Determine Fungal Microbiome Composition in a Common Garden Experiment. Fungal Ecol. 2022, 56, 101137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Chen, T.; Wang, W.; Liu, G.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Wang, M.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, H.; et al. Plant Phenotypic Traits Eventually Shape Its Microbiota: A Common Garden Test. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, T.N. Endophytic Fungi in Forest Trees: Are They Mutualists? Fungal Biol. Rev. 2007, 21, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.S.; Ganley, R.J.; Bradshaw, R.E. The Hemibiotrophic Lifestyle of the Fungal Pine Pathogen Dothistroma septosporum. For. Pathol. 2015, 45, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agan, A.; Solheim, H.; Adamson, K.; Hietala, A.M.; Tedersoo, L.; Drenkhan, R. Seasonal Dynamics of Fungi Associated with Healthy and Diseased Pinus sylvestris Needles in Northern Europe. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ata, J.P.; Burns, K.S.; Stewart, J.E. Needle Pathogens of Rhytismataceae: Current Knowledge and Research Opportunities for Conifer Foliar Diseases. For. Pathol. 2024, 54, e12851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.; Diogo, E.; Henriques, J.; Ramos, A.P.; Sandoval-Denis, M.; Crous, P.W.; Bragança, H. Pestalotiopsis pini sp. nov., an Emerging Pathogen on Stone Pine (Pinus pinea L.). Forests 2020, 11, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.; Glen, M.; McDougal, R. Molecular Tools for Differentiating Cyclaneusma minus Morphotypes and Assessing Their Distribution in Pinus radiata Forests in New Zealand. N. Z. J. For. Sci. 2016, 46, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingfield, M.J.; Brockerhoff, E.G.; Wingfield, B.D.; Slippers, B. Planted Forest Health: The Need for a Global Strategy. Science 2015, 349, 832–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Protecting Plantations from Pests and Diseases. Report Based on the Work of W.M. Ciesla. In Forest Plantation Thematic Papers, Working Paper 10; Forest Resources Development Service, Forest Resources Division; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Robin, C.; Wagner, S.; Baubet, O.; Ehrenmann, F.; Castagneyrol, B.; Capdevielle, X.; Fabreguettes, O.; Petit, R.J.; Piou, D. Effects of the Cascading Translocations of Larch (Larix decidua Mill.) on Canker Disease Due to Lachnellula willkommii (R. Hartig) Dennis. Ann. For. Sci. 2023, 80, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, A.A.; Sgrò, C.M. Climate Change and Evolutionary Adaptation. Nature 2011, 470, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, M.J.; Quijada, L.; Tobin, P.C.; Braun, U.; Newlander, C.; Potterfield, T.; Alford, É.R.; Contreras, C.; Coombes, A.; Moparthi, S.; et al. More Than Just Plants: Botanical Gardens Are an Untapped Source of Fungal Diversity. Horts 2022, 57, 1289–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennos, R.; Cottrell, J.; Hall, J.; O’Brien, D. Is the Introduction of Novel Exotic Forest Tree Species a Rational Response to Rapid Environmental Change?—A British Perspective. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 432, 718–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turenne, C.Y.; Sanche, S.E.; Hoban, D.J.; Karlowsky, J.A.; Kabani, A.M. Rapid Identification of Fungi by Using the ITS2 Genetic Region and an Automated Fluorescent Capillary Electrophoresis System. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999, 37, 1846–1851, Erratum in J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000, 38, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.D.; Lee, S.B.; Taylor, J.W. Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast Length Adjustment of Short Reads to Improve Genome Assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Fu, L.; Niu, B.; Wu, S.; Wooley, J. Ultrafast Clustering Algorithms for Metagenomic Sequence Analysis. Brief. Bioinform. 2012, 13, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable and Extensible Microbiome Data Science Using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857, Erratum in Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarenkov, K.; Zirk, A.; Piirmann, T.; Pöhönen, R.; Ivanov, F.; Nilsson, R.H.; Kõljalg, U. UNITE QIIME Release for Eukaryotes; UNITE Community: Bradford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Kaehler, B.D.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.; Bolyen, E.; Knight, R.; Huttley, G.A.; Gregory Caporaso, J. Optimizing Taxonomic Classification of Marker-Gene Amplicon Sequences with QIIME 2′s Q2-Feature-Classifier Plugin. Microbiome 2018, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, A.K.; Brown, S.P.; Callaham, M.A.; Jumpponen, A. Polymerase Matters: Non-Proofreading Enzymes Inflate Fungal Community Richness Estimates by up to 15%. Fungal Ecol. 2015, 15, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.P.; Veach, A.M.; Rigdon-Huss, A.R.; Grond, K.; Lickteig, S.K.; Lothamer, K.; Oliver, A.K.; Jumpponen, A. Scraping the Bottom of the Barrel: Are Rare High Throughput Sequences Artifacts? Fungal Ecol. 2015, 13, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Song, Z.; Bates, S.T.; Branco, S.; Tedersoo, L.; Menke, J.; Schilling, J.S.; Kennedy, P.G. FUNGuild: An Open Annotation Tool for Parsing Fungal Community Datasets by Ecological Guild. Fungal Ecol. 2016, 20, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.-Z.; Chen, G.; Alekseyenko, A.V. PERMANOVA-S: Association Test for Microbial Community Composition That Accommodates Confounders and Multiple Distances. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2618–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J.; Ellingsen, K.E.; McArdle, B.H. Multivariate Dispersion as a Measure of Beta Diversity. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisanz, J.E. qiime2R: Importing QIIME2 Artifacts and Associated Data into R Sessions. 2018. Available online: https://github.com/jbisanz/qiime2R (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Lin, H.; Peddada, S.D. Analysis of Compositions of Microbiomes with Bias Correction. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ata, J.P.; Ibarra Caballero, J.R.; Abdo, Z.; Mondo, S.J.; Stewart, J.E. Transitions of Foliar Mycobiota Community and Transcriptome in Response to Pathogenic Conifer Needle Interactions. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke-Borowczyk, J.; Kwaśna, H.; Kulawinek, B. Fungi Associated with Cyclaneusma Needle Cast in Scots Pine in the West of Poland. For. Pathol. 2019, 49, e12487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oono, R.; Lefèvre, E.; Simha, A.; Lutzoni, F. A Comparison of the Community Diversity of Foliar Fungal Endophytes between Seedling and Adult Loblolly pines (Pinus taeda). Fungal Biol. 2015, 119, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millberg, H.; Boberg, J.; Stenlid, J. Changes in Fungal Community of Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris) Needles along a Latitudinal Gradient in Sweden. Fungal Ecol. 2015, 17, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarević, J.; Menkis, A. Fungal Diversity in the Phyllosphere of Pinus Heldreichii H. Christ—An Endemic and High-Altitude Pine of the Mediterranean Region. Diversity 2020, 12, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulman, L.S.; Gadgil, P.D. Cyclaneusma Needle-Cast in New Zealand, Forest Research Bulletin No. 222; Forest Research: Rotorua, New Zealand, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Prihatini, I.; Glen, M.; Wardlaw, T.J.; Mohammed, C.L. Lophodermium pinastri and an Unknown Species of Teratosphaeriaceae Are Associated with Needle Cast in a Pinus radiata Selection Trial. For. Pathol. 2015, 45, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartnik, C.; Kowalski, T.; Bilański, P.; Zwijacz-Kozica, T. Fungi Associated with Disease Symptoms on Pinus mugo Needles in the Polish Tatra Mountains. Pl. Fung. Systt. 2021, 66, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinecke, C.D.; Niyas, A.M.M.; McCarty, E.; Quesada, T.; Smith, J.A.; Villari, C. Searching the Pinus taeda Foliar Mycobiome for Emerging Pathogens Among Brown-Spot Needle Blight and Needlecast Outbreaks in the Southeast United States. Phytobiomes J. 2024, 8, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondruskova, E.; Kobza, M.; Janosikova, Z.; McDougal, R.; Adamcikova, K. Which Cyclaneusma minus Morphotypes Are Responsible for Needle Cast of Pinus spp. in Slovakia? J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2024, 131, 1665–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Wingfield, M.J.; Cheewangkoon, R.; Carnegie, A.J.; Burgess, T.I.; Summerell, B.A.; Edwards, J.; Taylor, P.W.J.; Groenewald, J.Z. Foliar Pathogens of Eucalypts. Stud. Mycol. 2019, 94, 125–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, P.; Gonçalves, M.F.M.; Pinto, G.; Silva, B.; Martín-García, J.; Diez, J.J.; Alves, A. Three Novel Species of Fungi Associated with Pine Species Showing Needle Blight-like Disease Symptoms. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2022, 162, 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kan, J.A.L.; Shaw, M.W.; Grant-Downton, R.T. Botrytis Species: Relentless Necrotrophic Thugs or Endophytes Gone Rogue? Mol. Plant Pathol. 2014, 15, 957–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broders, K.; Munck, I.; Wyka, S.; Iriarte, G.; Beaudoin, E. Characterization of Fungal Pathogens Associated with White Pine Needle Damage (WPND) in Northeastern North America. Forests 2015, 6, 4088–4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, N.; Wang, L.; You, C. Diversity, Community Structure, and Antagonism of Endophytic Fungi from Asymptomatic and Symptomatic Mongolian Pine Trees. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Endoh, R.; Masumoto, H.; Yoshihashi, Y.; Ohkuma, M.; Degawa, Y. Taxonomic Study of Polymorphic Basidiomycetous Fungi Sirobasidium and Sirotrema: Sirobasidium apiculatum sp. nov., Phaeotremella translucens Comb. nov. and Rediscovery of Sirobasidium japonicum in Japan. Antonie Van. Leeuwenhoek 2022, 115, 1421–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandoni, R.J. Sirotrema: A New Genus in the Tremellaceae. Can. J. Bot. 1986, 64, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, D.A.; Minter, D.W. Pseudostypella translucens (Gordon) Reid & Minter Comb.Nov., a Hyperparasite on Lophodermium conigenum. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1979, 72, 345–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenstein, K.; Terhonen, E.; Sun, H.; Asiegbu, F.O. Methods for Studying the Forest Tree Microbiome. In Forest Microbiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Escribano, L.; Iturritxa, E.; Elvira-Recuenco, M.; Berbegal, M.; Campos, J.A.; Renobales, G.; García, I.; Raposo, R. Herbaceous Plants in the Understory of a Pitch Canker-Affected Pinus radiata Plantation Are Endophytically Infected with Fusarium circinatum. Fungal Ecol. 2018, 32, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.