Abstract

Virulence factors in enterococci play an important role in the pathogenesis of enterococcal infection and colonization. The aim was to determine the prevalence of genes encoding virulence factors in VRE from clinical and intestinal samples. A total of 163 VRE (94 clinical and 69 intestinal) isolated from patients treated in the University Hospital were studied. Species identification was performed by Vitek 2. The genes for vancomycin resistance (vanABCDMN) and virulence factors (ace/acm, asa1, esp, efaA, cylA, gelE and hyl) were detected by multiplex PCR. The prevalence of virulence genes with respect to clinical and intestinal E. faecium was compared using Fisher’s exact test and p > 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Carriers of virulence factors were 107 VRE: 85 clinical and 14 intestinal E. faecium, 6 intestinal E. gallinarum and single E. durans and E. faecalis. The dominant virulence genes were acm and esp. Genes for virulence factors were not detected in the tested E. casseliflavus isolates. There was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of the genes encoding virulence determinants between the clinical and intestinal E. faecium. High diversity of virulence determinants was found in 107 VRE and a combination of two genes, mainly acm and esp, was detected in 94 of them.

1. Introduction

Enterococci are part of the normal microbiota of the human intestinal tract. Also, these bacteria are causative agents of a wide spectrum of nosocomial infections such as urinary tract infections, intra-abdominal, pelvic and postoperative infections, bacteremia, and infective endocarditis. In rare cases, they have been associated with the pathogenesis of central nervous system infections, respiratory tract infections, eye infections, etc. [1,2].

Enterococci are widely spread worldwide. They are the second-most common Gram-positive bacteria in United States, Europe, and China associated with hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) [3,4,5]. Significant healthcare challenge are vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), particularly vancomycin-resistant (VR) E. faecium [6]. In Australia, the Australian Passive AMR Surveillance Report for 2023 concluded that 42.5% of E. faecium isolates are resistant to vancomycin [7]. The latest ECDC Annual Epidemiological Report for 2024 [8] shows that the average percentage of invasive VR E. faecium is 16.5% and it ranged from 0.0% in Iceland and Luxemburg to 61.7% in Lithuania. In Bulgaria, until 2012, the incidence of invasive VR E. faecium was 0%. After that, a trend towards an increase was noted and in 2024, the national percentage of VR E. faecium for Bulgaria was 14.5% [9]. All these data testify for the rapid spread of VRE in the hospitals.

The pathogenicity of enterococci is associated with their ability to adhere to the epithelium of the urinary tract, oral cavity, and embryonic kidney cells; to attach to extracellular matrix proteins and inert materials such as a number of medical devices; and to evade the immune system and form a biofilm, making them resistant to antibiotic action and phagocytic attack [10,11]. The capability of enterococci to acquire new traits contributes to virulence, allowing them to colonize new areas in the host and to cause different types of infections [12].

The virulence of enterococci is regulated by genes located in specific regions of the cell genome, called “pathogenicity islands” (PAIs) [13]. The first report for the presence of PAIs in the genome of a multidrug-resistant nosocomial E. faecalis strain (MMH594) was described by Huycke et al. in 1991 [14]. The genomic region was about 150 kb in size and contained genes encoding transposases, transcriptional regulators, and proteins with a role in the virulence. The PAI genes of E. faecalis were subsequently found to be responsible for the production of enterococcal surface protein, secretory cytolysin, and aggregation substance [15,16]. Usually, PAIs are closely related to virulent enterococcal clones and are often modified or even absent in less virulent strains. The changes that occur in the enterococcal PAIs are an important element for their evolution [12,17].

Virulence factors in enterococci can be divided into three main groups: surface adhesion factors, hydrolytic enzymes, and secreted virulence factors [10]. The first group includes pili, aggregation substance, and extracellular surface proteins. Hydrolytic enzymes include hyaluronidase, gelatinase, and serine protease. A major secreted virulence factor is the cytolysin, also known as β-hemolysin.

The enterococcal surface protein (Esp) is found in the cell wall of E. faecium and E. faecalis and its production is encoded by the esp gene. In vitro conjugative transfer of the esp gene has been demonstrated in the two strains. Esp is widely distributed among different strains of E. faecalis whereas, in E. faecium, it is predominantly presented in hospital-acquired isolates [18]. The functions of this virulence factor is to promote the adhesion, colonization, and evasion of immune system defense mechanisms [19]. Heikens et al. [20] found that E. faecium Esp is responsible for biofilm formation and plays a role in the pathogenesis of endocarditis and bacteremia. Another virulence factor is the aggregation substance (AS) found in E. faecalis and encoded by conjugated plasmid (asa1 or aggA). AS enhances the adhesion to renal tubular cells [21] and promotes the attachment and survival of enterococci in macrophages [22]. Collagen-binding proteins play a key role in the pathogenesis of endocarditis as they help for the attachment of enterococci to tissue cells [23]. Adhesion to collagen in E. faecalis (Ace) is encoded by the ace gene and the adhesion to collagen of E. faecium (Acm) is encoded by the acm gene. It is interesting to note that the functional acm gene is present mainly in clinical isolates [24]. EfaA (E. faecalis antigen A) is a major cell surface antigen in E. faecalis identified using sera from patients with endocarditis. It is encoded by the efaA gene. Data show that the efaA gene is present in almost all E. faecalis isolates, and its homolog has also been found in E. faecium [25]. Gelatinase is an extracellular Zn-containing metalloproteinase that hydrolyzes gelatin, collagen, and other proteins. The gene encoding the production of gelatinase (gelE) is located on an operon together with the fsrE gene encoding the serine protease [26]. Mutations in the fsr operon and inactivation of the fsr-control gene gelE indicate the important role of gelatinase in biofilm formation in E. faecalis [27]. Hyaluronidase (Hyl) produced by E. faecalis and E. faecium is a hydrolytic enzyme that degrades hyaluronic acid with subsequent tissue invasion and provides nutrients to bacteria. Its synthesis is encoded by the hyl gene which is carried on a plasmid. Gomez et al. [28] described a megaplasmid (hylEfm) in E. faecium containing the hyl gene, antibiotic resistance genes, and metabolic genes. These megaplasmids are widely spread among clinical E. faecium isolates and play a key role in colonization. Cytolysin (Cyl), also called β-hemolysin or bacteriocin, is encoded by the cyl gene in E. faecalis. The Cyl has lytic activity against various types of eukaryotic cells, including immune cells [29,30]. Several studies have testified for the role of E. faecalis Cyl in the pathogenesis of enterococcal infection. Huycke et al. [14] found that the mortality rate in patients with bacteremia caused by hemolytic, gentamicin-resistant strains of E. faecalis was five times higher than in patients infected with nonhemolytic, gentamicin-susceptible strains.

The number of studies investigating the distribution of virulence factors among non-faecalis/non-faecium enterococcal species is limited [31,32,33]. In a study from 2016, the most common gene detected in 5/33 E. mundtii, 4/35 E. raffinosus, 3/9 E. solitaries, 2/20 E. malodoratus, 2/10 E. dispar, and 1/17 E. hirae was gelE. Additionally, cylA, hyl and asa1 were confirmed in a single vancomycin-susceptible (VS) non-faecalis/non-faecium strain [31]. Sienko et al. [32] detected esp, hyl, and acm in six unusual vs. enterococci (five E. avium and one E. durans).

The type and number of virulence factors in VR E. faecalis and E. faecium varies among different studies [34,35,36,37]. Haghi et al. [37] investigated the frequency of genes encoding virulence factors in 79 VRE (69 E. faecalis and 10 E. faecium) isolated from urine and found esp in 67.1% of the strains, followed by PAI (45.5%) and sprE (41.7%). Carriage of two or more genes was detected in 67 (97.1%) E. faecalis and in 5 (50%) E. faecium. Iranian authors [36] found that, among 190 VR E. faecalis and 75 VR E. faecium, the most identifiable virulence gene was asa1. In addition, esp and hyl genes have also been demonstrated both in E. faecalis and E. faecium. Jovanovic et al. [34] investigated the prevalence of esp and hyl among VRE isolates from five hospitals in Belgrade, Serbia. The authors confirmed these genes in 45 (29.2%) and 43 (27.9%) E. faecium isolates and in 16 (76.2%) and 0 (0%) E. faecalis isolates, respectively. Only in eight E. faecium were the esp and hyl in combination.

Regarding the clinical significance of VRE, the wide diversity of virulence determinants among VR E. faecium and VR E. faecalis and the limited amount of scientific data about the distribution of virulence genes among VR non-faecalis/non-faecium species, the aim of the current study was to determine the prevalence of genes encoding virulence factors in VRE species isolated from the clinical and intestinal samples of hospitalized patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Isolates

The present study was performed on 163 non-repeated VRE isolated from patients treated in the University Hospital, “Dr. G. Stranski”, Pleven, Bulgaria from January 2016 to December 2020. The research was approved by the local ethics board of Medical University-Pleven. Data processing was anonymized and complied with local data protection legislation (No. 455/21.06.2017 and No. 512/03.05.2018) and with the European Directive on the Privacy of Data (95/46/EC). All subjects that participated in this study gave a written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Various samples were obtained from symptomatic or suspected for colonization patients using sterile swabs, containers, or BD BACTEC™ blood culture bottles (Becton Dickinson, Wokingham, UK). They were directly transported to the Department of Clinical Microbiology with subsequent culturing on the appropriate culture media. All samples obtained from the patients, over 18 years, suspected for infection or colonization in our hospital were included in the study. Duplicated enterococci isolated from the same patient or the same samples were excluded from the analysis. Each enterococcal isolate carrying any of the van genes of resistance were defined as VRE.

A total of 94 VRE were the isolates causing symptomatic infections. They were detected from surgical wounds (n = 45), urine samples (n = 37), hemocultures (n = 6), drainages (n = 2), stomach aspirates (n = 2), and ascites (n = 2), and all these isolates were labeled “Clinical”. The remaining 69 VRE were isolated in fecal screening of patients with high risk for colonization and were labeled “Intestinal”. A total of 23 out of the 69 intestinal VRE strains were described previously [38].

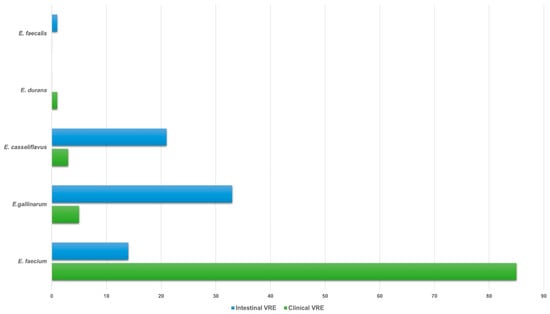

The species distribution of VRE isolates was as follows: 85 clinical and 14 intestinal E. faecium, 5 clinical and 33 intestinal E. gallinarum, 3 clinical and 21 intestinal E. casseliflavus, 1 clinical E. durans and 1 intestinal E. faecalis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Species distribution of 94 clinical and 69 intestinal VRE isolates. Abbreviations: VRE, vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

2.2. Culture Media

The clinical VRE were routinely isolated in the laboratory using 5% blood agar plates (BB-NCIPD Ltd., Sofia, Bulgaria) or ChromID CPS Elite agar (bioMerieux, Lyon, France) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Combination of chromogenic media chromID VRE (bioMerieux, Lyon, France), Brilliance VRE (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK), HiCrome VRE Modified (HIMEDIA, Mombaai, India) and a bile esculin azide broth (BEAV) with 6 μg/mL vancomycin (Liofilchelm, Roseto degli Abruzzi, Italy) were used for isolation of the intestinal VRE as previously described [39,40]. Briefly, the inoculated culture media were incubated at 37 °C and were observed for growth at 24 h and 48 h. Preliminary identification of VRE on each chromogenic media was based on the appropriate color of the colony. The color of positive BEAV broths turn black and were transferred on 5% BAP and chromID CPS Elite agar for an additional 24 h incubation.

The Gram-positive and catalase-negative cocci were tested with L-pyrrolidonyl arylamidase (PYR) test (Liofilchem, Italy), lucine amino peptidase (LAP) test (Oxoid, UK), ability to grow in 6.5% NaCl and bile esculin agar (Liofilchem, Italy) as well as for the presence of streptococcal D antigen. In addition, the fermentation activity to mannitol, sorbose and methyl-α-D glucopyranoside (MGP) (Oxoid, UK), the arginine hydrolysis, motility and pigment production were used for differentiation of the enterococci to group level. Species identification of the isolates was confirmed by Vitek 2 Compact system (bioMerieux, France).

2.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility

Vancomycin and teicoplanin minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined by E-test (Liofilchem, Italy) which is an agar diffusion method for direct detection of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of the antimicrobial agents. The E-test utilizes a strip (60/5 mm) that has been impregnated with exponential concentrations of the antibiotic to be studied. The strip was placed on the surface of an agar plate that has been inoculated with the tested microorganism and incubated at 35 °C for 18–24 h. During that time, the antibiotic diffused outward from the strip and an elliptical zone of growth inhibition is formed. The point of crossing the ellipse was determined as MIC. The results of the test were interpreted according to the recommendations of The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters) guidelines.

2.4. Amplification of Antibiotic Resistance and Virulence Genes

The genes for vancomycin resistance (vanA, vanB, vanC, vanD, vanM, vanN) and virulence factors (collagen-binding proteins (ace/acm), aggregation substance (asa1), enterococcal surface protein (esp), endocarditis-specific antigen A (efaA), cytolysin (cylA), gelatinase (gelE) and hyaluronidase (hyl) were detected by multiplex PCR using previously described primers sequences [41,42,43] and protocols [38]. A complete list of the primers with sequences is included in Table 1. Briefly, a modified PCR mix (20 μL) for detection of the investigated genes was applied. It contained a 10 ng DNA template, 0.4 μM (each) primer, 200 μM (each) dNTPs (Canvax, Spain), 1 U of Taq (Canvax), 2.5 mM MgCl2 (Canvax), 1X reaction buffer (Canvax), and ultrapure PCR H2O (Canvax).

Table 1.

PCR primers used in the study.

The PCR tal conditions for the detection of van genes were as follows: initial denaturation (94 °C for 4 min), followed by 30 cycles of denaturation (94 °C for 30 s) and annealing (62 °C for 35 s) and extension (68 °C for 1 min), with a single final extension of 7 min at 68 °C.

The PCR amplification protocol to detect genes for virulence factors was as follows: initial denaturation (95 °C for 4 min), followed by 34 cycles of denaturation (96 °C for 20 s), annealing (53 °C for 25 s), extension (72 °C for 30 s), and final extension at 72 °C for 3 min. Capillary electrophoresis was used for the visualization and analysis of amplified PCR products.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out in IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The prevalence of virulence genes between clinical and intestinal E. faecium isolates was evaluated using Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance was defined when p-value was below 0.05. The results are shown as percentages.

3. Results

A total of 107 (65.6%) VRE were carriers of virulence factors: 85 clinical and 14 intestinal E. faecium isolates, 6 intestinal E. gallinarum, and the single isolates E. durans and E. faecalis. Genes for virulence factors were not detected in the tested E. casseliflavus isolates.

3.1. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Antibiotic Resistance Genes

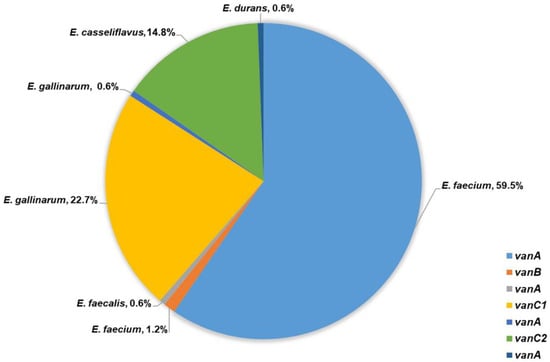

Among the tested 99 E. faecium isolates, 13 intestinal and 84 clinical expressed VanA phenotype of glycopeptide resistance with high-level resistance to vancomycin (MIC ≥ 256 μg/mL) and varying resistance to teicoplanin (MICs: 6–256 μg/mL). The presence of vanA gene was confirmed in all of them. The other two E. faecium (one intestinal and one clinical) showed low-level resistance to vancomycin (MIC = 8 μg/mL), susceptibility to teicoplanin (MIC = 0.5 μg/mL) and vanB was detected. VanB phenotype was confirmed in the intestinal E. faecalis isolate with low-level resistance to vancomycin (MIC = 12 μg/mL), susceptibility to teicoplanin (MIC = 0.5 μg/mL) and vanB gene was confirmed. In addition, high-level resistance to vancomycin (MIC ≥ 256 μg/mL), resistance to teicoplanin (MIC = 16 μg/mL) and a presence of vanA gene was demonstrated by the single clinical E. durans isolate (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Frequency of van genes detected among 163 VRE.

A total of 37 out of 38 tested E. gallinarum and all 24 E. casseliflavus showed VanC phenotype with MICs to vancomycin between 2 μg/mL and 16 μg/mL and susceptibility to teicoplanin (MIC from 0.38 μg/mL to 1.5 μg/mL). E. gallinarum strains were positive for vanC1 and E. casseliflavus for vanC2. A single intestinal E. gallinarum isolate expressed high-level resistance to vancomycin, teicoplanin (MIC ≥ 256 μg/mL), and vanA gene was confirmed (Figure 2).

3.2. Prevalence of Virulence Genes in Clinical Isolates

Positive for virulence determinants were 91.5% (85 E. faecium and 1 E. durans) of the investigated clinical strains (Table 2). The most commonly detected genes among the isolates were esp (n = 84), acm (n = 84), and gelE (n = 5). A total of 77 out of 85 tested E. faecium were positive for acm and esp. Third virulence gene was confirmed in six isolates (7.1%)—three strains were positive for hyl and three for gelE. One E. faecium carried only gelE and another has four virulence genes (gelE, asa1, esp and ace). The combination of acm and hyl was confirmed in E. durans (Table 2). None of the tested E. gallinarum and E. casseliflavus was positive for virulence genes.

Table 2.

Profile of virulence genes in 86 clinical VRE.

3.3. Prevalence of Virulence Genes in Intestinal VRE Isolates

One or more virulence determinants (ace/acm, asa1, cylA, efaA, esp, gelE and hyl) were detected in 30.4% intestinal isolates (14 E. faecium, 6 E. gallinarum and 1 E. faecalis) (Table 3). Among them, the most frequently identified genes were esp (n = 18), acm (n = 17), and hyl (n = 4). The combination of acm and esp was found in 12 (85.7%) out of 14 E. faecium. An additional virulence gene hyl was detected in two enterococci (15.3%). In E. faecalis, four genes (gelE, asa1, efaA and ace) were confirmed. Among the six E. gallinarum isolates, three (50%) were carriers of acm in combination with esp or hyl, two (33.3%) were positive for hyl or esp, and one (16.7%) was positive for asa1, efaA, esp, ace, and cylA (Table 3). Genetic determinants of virulence were not found in the tested 27 E. gallinarum and 21 E. casseliflavus.

Table 3.

Profiles of virulence gene in 21 intestinal VRE isolates.

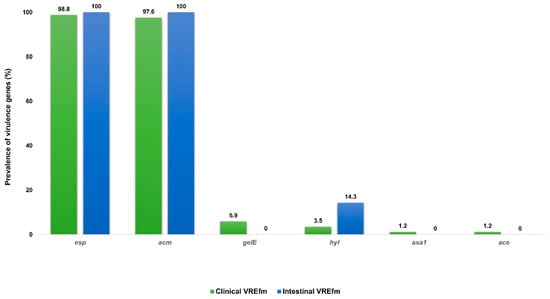

3.4. Comparative Prevalence of Virulence Genes Among Clinical E. faecium and Intestinal E. faecium

The prevalence of genes encoding virulence factors in the two studied E. faecium groups is presented in Figure 3. There was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of the genes encoding virulence determinants between the clinical and intestinal E. faecium. The esp was confirmed in 98.8% clinical and 97.6% intestinal strains (p < 0.999), acm—100% vs. 100% (p < 0.999), gelE—5.9% vs. 0% (p < 0.999), hyl—3.5% vs. 14.3% (p < 0.1451), and asa1 and ace 1.2% vs. 0% (p < 0.999).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of virulence genes among 85 clinical and 14 intestinal E. faecium. Abbreviations: VREfm: vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium; esp, enterococcal surface protein; acm/ace, adhesion to collagen of E. faecalis/E. faecium; gelE, gelatinase; hyl, hyaluronidase; asa1, aggregation substance.

4. Discussion

Enterococci are widely spread in the nature. They can be found in soil, water, food, and various animals. In healthy people, they are part of the normal microbiota of the small and large intestines and are less commonly found in other areas [47]. Dominant enterococcal species in the human gut are E. faecium and E. faecalis. E. faecium is also the main species in the gut of pigs, cattle, and poultry (production animals). In the environment, prevalent non-faecalis/non-faecium species include E. mundtii, E. casseliflavus, etc. [2].

A distinctive characteristic of enterococci is their antibiotic resistance to various agents [48], which is significantly influenced by the geographical location. According to the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program [5], ampicillin resistance in E. faecium was the highest in Asia-Pacific (91.6%), followed by Europe (90.8%), North America (89.6%), and Latin America (81.6%). In all four regions, the most common glycopeptide resistance phenotypes were VanA and VanB, as VanA predominated. Its frequency varied in E. faecium isolates from 19.0% in Europe to 64.7% in North America. Geographical differences were also confirmed in streptomycin susceptibility among the tested enterococci [5].

In addition to antibiotic resistance in Enterococcus, many studies testified for the wide distribution of different genes encoding virulence factors among them. These genetic determinants play an important role in the pathogenesis of VS/VR enterococcal infection and colonization in healthy individuals. It is well known that, once colonizing the gut of hospitalized patients, VRE remain there for weeks or months [49,50]. In addition to being spread by direct patient-to-patient contact, VRE are also transmitted indirectly through transient carriage on the hands of the healthcare personnel, contaminated medical instruments, and other objectives in the hospital environment [51,52]. Enterococci survive for long period of time on various surfaces; they are tolerant to heat, chlorine, and some alcohol preparations. All these factors increased the possibility of their transmission and spreading of antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes in hospitalized patients [3,53].

This study found a high prevalence of virulence determinants in a total of 86 clinical VRE, in contrast with data from Southwest Nigeria which testified for the low occurrence of virulence factors in clinical VRE [54]. Also, the current results showed that there was no significant difference in the circulating genes encoding virulence factors. The most common combination of virulence genes was esp and acm. Two or more genetic determinants were detected in 84 E. faecium and in 1 E. durans. High prevalence of esp (87%) among VR E. faecium was also described by Cakirlar et al. [55]. Song et al. [56] studied 40 VR E. faecium and confirmed the presence of esp and hyl genes in 100% and 92.5% of the isolates, respectively. Research from 2023 revealed that the gelE gene is the most common among VR E. faecium (76%) and VR E. faecalis (69%) [57]. Bulgarian authors investigated the prevalence of genes encoding virulence factors among a total of 110 clinical vs. E. faecium and found efaA in 88.5%, acm in 72.8%, hyl in 24.2%, asa1 in 22.8%, gelE in 17.1%, and esp in 4.3% of the isolates [58].

Usually, genes encoding aggregation substance synthesis (asa1), efaA protein (efaA), gelatinase (gelE), and cytolysin (cyl) are commonly detected in E. faecalis [59,60,61]. Some publications testified for the presence of these virulence determinants also in E. faecium [31,36,58,62]. Nasaj et al. [36] found asa1 gene in 51 VR E. faecium. In another study, gelE, esp, and asa1 were demonstrated in 45 (100%), 36 (80%), and 33 (73.3%) clinical VR E. faecium, respectively [62]. In the testing of 46 clinical vs. E. faecium for carriage of virulence determinants, asa1 was confirmed in 9 of them, and gelE and cylA in 7 and 6 isolates, respectively [31]. In addition, the collagen-binding protein in E. faecalis was usually encoded by ace and in E. faecium by acm, although Haghi et al. [37] reported the presence of ace in 89.8% of VR E. faecalis and in 80% of VR E. faecium. An Iranian study found the acm gene in 87 (81%) E. faecium, and in 7 of them, it was in combination with ace [63]. All these data testified for the circulation of acm and ace in both E. faecalis and E. faecium.

Determinants of enterococcal pathogenicity have been described among isolates from different origins—clinical, animal, or food. However, data on their distribution among VRE isolated from the human intestinal tract are limited. The results of this study showed the presence of genes encoding virulence factors in 30.4% of a total of 69 intestinal VRE. All 14 E. faecium and 1 E. faecalis were carrying virulence genes, whereas only 6 (5 vanC E. gallinarum and 1 vanA E. gallinarum) out of 54 non-faecalis/non-faecium VRE were positive. These data testified for the higher prevalence of virulence determinants among E. faecium compared to E. gallinarum and E. casseliflavus. The current results were similar to those of Sienko et al. [32] who found that the number and types of virulence determinants was significantly higher among E. faecium strains in comparison with uncommon clinical enterococcal isolates such as E. avium, E. gallinarum, E. casseliflavus, and E. durans.

The majority of intestinal VRE (19/90.5%) in that research were carriers of two or more virulence genes. The acm gene was detected in 85.7% of the isolates, esp in 81% and hyl in 19% of them. Similar data was reported from Chinese authors [35] that found the esp in 62 (89.9%) E. faecium and hyl in 19 (27.5%). The two genes were in combination in 18 (28.6%) of the positive isolates, and in 45 (71.4%) they were presented alone. In the testing of 26 intestinal VRE, Biswas et al. [31] detected virulence determinants in 19 (61.5%), while a combination of 2 genes was only confirmed in 5 of them. The predominant genes among the positive strains were gelE (29.2%), esp (29.2%), and asa1 (25.0%). In the study of 35 intestinal E. faecium, 34 (97.1%) of them were carriers of the esp gene, 21 (60%) of asa1, 18 (51.4%) of gelE, and only 1 isolate (2.8%) was positive for hyl [62].

Regarding the investigated vanC enterococci in the present study, E. gallinarum isolates (6/33) were more likely to acquire virulence determinants than E. casseliflavus (0/21). Two of the positive E. gallinarum carried one virulence gene, three strains were positive for two genes, and one isolate had five virulence determinants. These results are in contrast with Dworniczek et al. [64,65] that reported an absence of virulence factor in E. gallinarum and E. casseliflavus isolated from urinary catheters and other clinical specimens. Other authors have described the presence of cylA, hyl or asa1 genes in single intestinal E. gallinarum isolates [31,66]. In 2011, Radhouani et al. [67] found a carriage of genes encoding virulence factors in seven out of eight tested E. gallinarum isolated from red fox faces.

The prevalence of virulence genes among the clinical E. faecium and intestinal E. faecium in that research were similar. The genes acm and esp and combination between them were the most commonly detected in the two studied groups. Six E. gallinarum were also positive for virulence genes, whereas none of the clinical E. gallinarum expressed virulence determinants. In E. casseliflavus isolates from both groups, genes encoding virulence factors were not confirmed. Biswas et al. [31] compared the distribution of virulence determinants in vs. and VR enterococci isolated from clinical and intestinal samples. The authors found that the frequency of virulence genes was higher among VRE compared to VSE and the prevalence of the studied genetic determinants was comparable between clinical and intestinal VRE.

The present results testified for circulation of VR E. faecium with almost identical virulence and van genes profile among both clinical and intestinal isolates. Reliable restriction measures to avoid the spread of VRE, together with measures for their early detection in infected and colonized patients could be of high importance in reduction in VRE HAIs/colonization and might prevent the distribution of additional virulence and resistance genes between these problematic microorganisms. Regardless of the small sample size and rare species detected, which is a weakness of this study, a future research goal is the genomic sequencing for PAI analysis of the VRE collection.

5. Conclusions

High diversity of virulence determinants was found in more than half (65.6%) of the studied VRE. A combination of two genes, mainly acm and esp, was detected in 94 (87.8%) of the positive isolates. The presence of virulence factors among intestinal E. gallinarum was low, while there was complete lack of such virulence genes in clinical E. gallinarum and clinical/intestinal E. casseliflavus. In comparison, in clinical and intestinal E. faecium, similar virulence factors were expressed and their prevalence was considerably high. Usually, the virulent enterococci are opportunistic pathogens in animals, and in rare cases, they are associated with serious infections. The animals are the main reservoir for the transmission of enterococci containing virulence and resistance genes to healthy humans. The aforementioned fact confirms that enterococci impact both animal and public health. To my knowledge, this is the first study in Bulgaria revealing the distribution of virulence genes among a significant number of VRE of clinical and especially intestinal origin.

Funding

This study is financed by the European Union-Next Generation EU, through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, project No. BG-RRP-2.004-0003.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sievert, D.M.; Ricks, P.; Edwards, J.R.; Schneider, A.; Patel, J.; Srinivasan, A.; Kallen, A.; Limbago, B.; Fridkin, S. National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Team and Participating NHSN Facilities. Antimicrobial-Resistant Pathogens Associated with Healthcare-Associated Infections Summary of Data Reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009–2010. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2013, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullally, C.A.; Fahriani, M.; Mowlaboccus, S.; Coombs, G.W. Non-Faecium Non-Faecalis Enterococci: A Review of Clinical Manifestations, Virulence Factors, and Antimicrobial Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2024, 37, e00121–e00123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkwirth, S.; Ayobami, O.; Eckmanns, T.; Markwart, R. Hospital-Acquired Infections Caused by Enterococci: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, WHO European Region, 1 January 2010 to 4 February 2020. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2001628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.-F.; Liu, C.; Xu, Y.-X.; Wang, F.; Luan, M.-X.; Li, F. Prevalence of Nosocomial Infections and Their Influencing Factors in a Tertiary General Hospital in Qingdao. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2024, 18, 1522–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Cormican, M.; Flamm, R.K.; Mendes, R.E.; Jones, R.N. Temporal and Geographic Variation in Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Resistance Patterns of Enterococci: Results from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997–2016. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019, 6, S54–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida-Santos, A.C.; Novais, C.; Peixe, L.; Freitas, A.R. Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus faecium: A Current Perspective on Resilience, Adaptation, and the Urgent Need for Novel Strategies. J. Global Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 41, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Passive AMR Surveillance: An Update of Resistance Trends in Multidrug-Resistant Organisms—2006 to 2023. 2024. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/australian-passive-amr-surveillance-update-resistance-trends-multidrug-resistant-organisms-2006-2023 (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Antimicrobial Resistance in the EU/EEA (EARS-Net)—Annual Epidemiological Report for 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/antimicrobial-resistance-eueea-ears-net-annual-epidemiological-report-2024 (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Surveillance Atlas of Infectious Diseases 2024. Available online: http://Atlas.Ecdc.Europa.Eu (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Sahm, D.F.; Kissinger, J.; Gilmore, M.S.; Murray, P.R.; Mulder, R.; Solliday, J.; Clarke, B. In Vitro Susceptibility Studies of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1989, 33, 1588–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, J.A.; Huang, D.B. Biofilm Formation by Enterococci. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007, 56, 1581–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, N.; Baghdayan, A.S.; Gilmore, M.S. Modulation of Virulence within a Pathogenicity Island in Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Nature 2002, 417, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker, J.; Kaper, J.B. Pathogenicity Islands and the Evolution of Microbes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2000, 54, 641–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huycke, M.M.; Spiegel, C.A.; Gilmore, M.S. Bacteremia Caused by Hemolytic, High-Level Gentamicin-Resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991, 35, 1626–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, V.; Baghdayan, A.S.; Huycke, M.M.; Lindahl, G.; Gilmore, M.S. Infection-Derived Enterococcus faecalis Strains Are Enriched in Esp, a Gene Encoding a Novel Surface Protein. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyaya, P.G.; Ravikumar, K.; Umapathy, B. Review of Virulence Factors of Enterococcus: An Emerging Nosocomial Pathogen. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2009, 27, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdayan, A.S.; Shankar, N.; Tendolkar, P.M. Pathogenic Enterococci: New Developments in the 21st Century. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2003, 60, 2622–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, R.J.; Homan, W.; Top, J.; van Santen-Verheuvel, M.; Tribe, D.; Manzioros, X.; Gaillard, C.; Vandenbroucke-Grauls, C.M.; Mascini, E.M.; van Kregten, E.; et al. Variant Esp Gene as a Marker of a Distinct Genetic Lineage of Vancomycinresistant Enterococcus faecium Spreading in Hospitals. Lancet 2001, 357, 853–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foulquié Moreno, M.R.; Sarantinopoulos, P.; Tsakalidou, E.; De Vuyst, L. The Role and Application of Enterococci in Food and Health. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 106, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heikens, E.; Singh, K.V.; Jacques-Palaz, K.D.; van Luit-Asbroek, M.; Oostdijk, E.A.N.; Bonten, M.J.M.; Murray, B.E.; Willems, R.J.L. Contribution of the Enterococcal Surface Protein Esp to Pathogenesis of Enterococcus faecium Endocarditis. Microbes Infect. 2011, 13, 1185–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreft, B.; Marre, R.; Schramm, U.; Wirth, R. Aggregation Substance of Enterococcus faecalis Mediates Adhesion to Cultured Renal Tubular Cells. Infect. Immun. 1992, 60, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süssmuth, S.D.; Muscholl-Silberhorn, A.; Wirth, R.; Susa, M.; Marre, R.; Rozdzinski, E. Aggregation Substance Promotes Adherence, Phagocytosis, and Intracellular Survival of Enterococcus faecalis within Human Macrophages and Suppresses Respiratory Burst. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 4900–4906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nallapareddy, S.R.; Singh, K.V.; Murray, B.E. Contribution of the Collagen Adhesin Acm to Pathogenesis of Enterococcus faecium in Experimental Endocarditis. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 4120–4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickx, A.P.A.; van Wamel, W.J.B.; Posthuma, G.; Bonten, M.J.M.; Willems, R.J.L. Five Genes Encoding Surface-Exposed LPXTG Proteins Are Enriched in Hospital-Adapted Enterococcus faecium Clonal Complex 17 Isolates. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 8321–8332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaton, T.J.; Gasson, M.J. Molecular Screening of Enterococcus Virulence Determinants and Potential for Genetic Exchange between Food and Medical Isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 1628–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Singh, K.V.; Weinstock, G.M.; Murray, B.E. Effects of Enterococcus faecalis fsr Genes on Production of Gelatinase and a Serine Protease and Virulence. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 2579–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, L.E.; Perego, M. Systematic Inactivation and Phenotypic Characterization of Two-Component Signal Transduction Systems of Enterococcus faecalis V583. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 7951–7958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverde Gomez, J.A.; van Schaik, W.; Freitas, A.R.; Coque, T.M.; Weaver, K.E.; Francia, M.V.; Witte, W.; Werner, G. A Multiresistance Megaplasmid pLG1 Bearing a hylEfm Genomic Island in Hospital Enterococcus faecium Isolates. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 301, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, C.; Coburn, P.; Gilmore, M. Enterococcal Cytolysin: A Novel Two Component Peptide System That Erves as a Bacterial Defense against Eukaryotic and Prokaryotic Cells. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2005, 6, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierbaum, G.; Sahl, H.-G. Lantibiotics: Mode of Action, Biosynthesis and Bioengineering. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2009, 10, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P.P.; Dey, S.; Sen, A.; Adhikari, L. Molecular Characterization of Virulence Genes in Vancomycin-Resistant and Vancomycin-Sensitive Enterococci. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2016, 8, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieńko, A.; Ojdana, D.; Majewski, P.; Sacha, P.; Wieczorek, P.; Tryniszewska, E. Comparison of Biofilm-Producing Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus faecium, and Unusual Enterococcus Strains. Eur. J. Biol. Res. 2017, 7, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpınar Kankaya, D.; Tuncer, Y. Detection of Virulence Factors, Biofilm Formation, and Biogenic Amine Production in Vancomycin-resistant Lactic Acid Bacteria (VRLAB) Isolated from Foods of Animal Origin. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e16423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, M.; Milošević, B.; Tošić, T.; Stevanović, G.; Mioljević, V.; Inđić, N.; Velebit, B.; Zervos, M. Molecular Typing, Pathogenicity Factor Genes and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Vancomycin Resistant Enterococci in Belgrade, Serbia. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung 2015, 62, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, T.; Ning, Y.; Shao, D.; Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Liang, G. Molecular Characterization of Resistance, Virulence and Clonality in Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis: A Hospital-Based Study in Beijing, China. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015, 33, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasaj, M.; Mousavi, S.M.; Hosseini, S.M.; Arabestani, R. Prevalence of Virulence Factors and Vancomycin-Resistant Genes among Enterococcus faecalis and E. faecium Isolated from Clinical Specimens. Iran. J. Public Health 2016, 45, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Haghi, F.; Lohrasbi, V.; Zeighami, H. High Incidence of Virulence Determinants, Aminoglycoside and Vancomycin Resistance in Enterococci Isolated from Hospitalized Patients in Northwest Iran. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hristova, P.; Nankov, V.; Stoikov, I.; Vanov, I.; Ouzounova-Raykova, V.; Hitkova, H. Prevalence of Genes Encoding Resistance to Aminoglycosides and Virulence Factors among Intestinal Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2022, 15, e128003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristova, P.; Hitkova, H.; Georgieva, D.; Todorova, G.; Sredkova, M. Evaluation of Three Chromogenic Media and a Selective Broth for Detection of Vancomycin Resistant Enterococci from Rectal Swab Specimens. Comptes Rendus Acad. Bulg. Sci. 2021, 74, 1146–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristova, P.; Nankov, V.; Hristov, I.; Trifonov, S.; Alexandrova, A.; Hitkova, H. Gut Colonization with Vancomicyn-Resistant Enterococci among Patients with Hematologic Malignancies. Gut Pathog. 2023, 15, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, T.; Hashimoto, Y.; Kurushima, J.; Hirakawa, H.; Tanimoto, K.; Zheng, B.; Ruan, G.; Xue, F.; Liu, J.; Hisatsune, J.; et al. New Colony Multiplex PCR Assays for the Detection and Discrimination of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcal Species. J. Microbiol. Methods 2018, 145, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Li, J.; Wei, Q.; Hu, Q.; Lin, X.; Chen, M.; Ye, R.; Lv, H. Characterization of Aminoglycoside Resistance and Virulence Genes among Enterococcus spp. Isolated from a Hospital in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 3014–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, I.L.B.C.; Gilmore, M.S.; Darini, A.L.C. Multilocus Sequence Typing and Analysis of Putative Virulence Factors in Vancomycin-Resistant and Vancomycin-Sensitive Enterococcus faecium Isolates from Brazil. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2006, 12, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vankerckhoven, V.; Van Autgaerden, T.; Vael, C.; Lammens, C.; Chapelle, S.; Rossi, R.; Jabes, D.; Goossens, H. Development of a Multiplex PCR for the Detection of Asa1, gelE, cylA, Esp., and Hyl Genes in Enterococci and Survey for Virulence Determinants among European Hospital Isolates of Enterococcus faecium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 4473–4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duprè, I.; Zanetti, S.; Schito, A.M.; Fadda, G.; Sechi, L.A. Incidence of Virulence Determinants in Clinical Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis Isolates Collected in Sardinia (Italy). J. Med. Microbiol. 2003, 52, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creti, R.; Imperi, M.; Bertuccini, L.; Fabretti, F.; Orefici, G.; Di Rosa, R.; Baldassarri, L. Survey for Virulence Determinants among Enterococcus faecalis Isolated from Different Sources. J. Med. Microbiol. 2004, 53, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannock, G.W.; Cook, G. Enterococci as Members of the Intestinal Microflora of Humans. In The Enterococci: Pathogenesis, Molecular Biology, and Antibiotic Resistance; Gilmore, M.S., Clewell, D.B., Courvalin, P., Dunny, G.M., Murray, B.E., Rice, L.B., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 101–132. [Google Scholar]

- Szczuka, E.; Rolnicka, D.; Wesołowska, M. Cytotoxic Activity of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci Isolated from Hospitalised Patients. Pathogens 2024, 13, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, K.E.; Anglim, A.M.; Anneski, C.J.; Farr, B.M. Duration of Colonization with Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2002, 23, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, K.M.; Peck, K.R.; Joo, E.-J.; Ha, Y.E.; Kang, C.-I.; Chung, D.R.; Lee, N.Y.; Song, J.-H. Duration of Colonization and Risk Factors for Prolonged Carriage of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci after Discharge from the Hospital. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 17, e240–e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, A.; Schwebke, I.; Kampf, G. How Long Do Nosocomial Pathogens Persist on Inanimate Surfaces? A Systematic Review. BMC Infect. Dis. 2006, 6, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirakzadeh, A.; Patel, R. Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci: Colonization, Infection, Detection, and Treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2006, 81, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Haddad, L.; Hanson, B.M.; Arias, C.A.; Ghantoji, S.S.; Harb, C.P.; Stibich, M.; Chemaly, R.F. Emergence and Transmission of Daptomycin and Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci Between Patients and Hospital Rooms. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 2306–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, F.M.; Yusuf, N.-A.; Adeboye, R.R.; Oyedara, O.O. Low Occurrence of Virulence Determinants in Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus from Clinical Samples in Southwest Nigeria. Int. J. Infect. 2021, 8, e114143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakirlar, F.; Samasti, M.; Baris, I.; Kavakli, H.; Karakullukcu, A.; Sirekbasan, S.; Bagdatli, Y. The Epidemiological and Molecular Characterization of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci Isolated from Rectal Swab Samples of Hospitalized Patients in Turkey. Clin. Lab. 2014, 60, 1807–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.Y.; Cheong, H.J.; Seo, Y.B.; Kim, I.S.; Heo, J.Y.; Noh, J.Y.; Choi, W.S.; Kim, W.J. Clinical and Microbiological Characteristics of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci with the VanD Phenotype and vanA Genotype. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 66, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doss Susai Backiam, A.; Duraisamy, S.; Karuppaiya, P.; Balakrishnan, S.; Chandrasekaran, B.; Kumarasamy, A.; Raju, A. Antibiotic Susceptibility Patterns and Virulence-Associated Factors of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcal Isolates from Tertiary Care Hospitals. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strateva, T.; Atanasova, D.; Savov, E.; Petrova, G.; Mitov, I. Incidence of Virulence Determinants in Clinical Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium Isolates Collected in Bulgaria. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 20, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, A.M.; Lambert, P.A.; Smith, A.W. Cloning of an Enterococcus faecalis Endocarditis Antigen: Homology with Adhesins from Some Oral Streptococci. Infect. Immun. 1995, 63, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, E.W. A Comparative Serological Study of Streptolysins Derived from Human and from Animal Infections, with Notes on Pneumococcal Hæmolysin, Tetanolysin and Staphylococcus Toxin. J. Pathol. 1934, 39, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayaoglu, G.; Ørstavik, D. Virulence Factors of Enterococcus faecalis: Relationship to Endodontic Disease. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2004, 15, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchi, A.P.; Perdigão Neto, L.V.; Martins, R.C.R.; Rizek, C.F.; Camargo, C.H.; Moreno, L.Z.; Moreno, A.M.; Batista, M.V.; Basqueira, M.S.; Rossi, F.; et al. Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci Isolates Colonizing and Infecting Haematology Patients: Clonality, and Virulence and Resistance Profile. J. Hosp. Infect. 2018, 99, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattari-Maraji, A.; Jabalameli, F.; Node Farahani, N.; Beigverdi, R.; Emaneini, M. Antimicrobial Resistance Pattern, Virulence Determinants and Molecular Analysis of Enterococcus faecium Isolated from Children Infections in Iran. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworniczek, E.; Kuzko, K.; Mróz, E.; Wojciech, Ł.; Adamski, R.; Sobieszczańska, B.; Seniuk, A. Virulence Factors and in Vitro Adherence of Enterococcus Strains to Urinary Catheters. Folia Microbiol. 2003, 48, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworniczek, E.; Wojciech, L.; Sobieszczanska, B.; Seniuk, A. Virulence of Enterococcus Isolates Collected in Lower Silesia (Poland). Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 37, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Sallem, R.; Klibi, N.; Klibi, A.; Ben Said, L.; Dziri, R.; Boudabous, A.; Torres, C.; Ben Slama, K. Antibiotic Resistance and Virulence of Enterococci Isolates from Healthy Humans in Tunisia. Ann. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhouani, H.; Igrejas, G.; Carvalho, C.; Pinto, L.; Gonçalves, A.; Lopez, M.; Sargo, R.; Cardoso, L.; Martinho, A.; Rego, V.; et al. Clonal Lineages, Antibiotic Resistance and Virulence Factors in Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci Isolated from Fecal Samples of Red Foxes (Vulpes vulpes). J. Wildlife Dis. 2011, 47, 769–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.