Abstract

Campylobacter concisus is recognized as a potential pathogen in gastrointestinal diseases, particularly in patients with chronic intestinal diseases. This study investigates the genomic characteristics, phylogenetic distribution, virulence factors, resistance genes and presence of plasmids in C. concisus isolates from Slovenian patients with community-acquired infectious diarrhoea. Prospectively collected isolates were analysed using whole-genome sequencing (WGS). WGS analysis revealed substantial genetic diversity among isolates, with distinct differences observed between two genomospecies (GS1, GS2). GS1 isolates had smaller genomes, lower GC content, and fewer coding regions than GS2 isolates. Multilocus sequence typing confirmed a high degree of genetic diversity, with most isolates belonging to novel sequence types. Plasmids, including pSma1 and pICON, were more prevalent in GS2 isolates. The virulence factors Zot and Exo9 toxins were detected in both genomospecies, with Zot predominantly found in GS1 and Exo9 in GS2. The T6 secretion system was prevalent in both groups, whereas the T4SS was less frequently observed. The combination of the T6SS, plasmids, and toxins suggests a complex mechanism of pathogenicity. This study highlights the high genetic diversity of C. concisus and provides new insights into its genomic features and virulence factors. The presence of plasmids and secretion systems, particularly the T6SS, underscores the potential of C. concisus for adaptation and pathogenicity.

1. Introduction

Infections caused by Campylobacter species are the most frequently reported zoonoses in the European Union (EU) [1]. Campylobacteriosis was the most frequently reported bacterial intestinal infection in Slovenia, with 38.6 reports per 100,000 inhabitants in 2023 [2].

Human infection typically occurs through the consumption of undercooked contaminated meat (especially poultry), unpasteurized milk, or contaminated water. Symptoms usually include watery diarrhoea, and in severe cases, bloody diarrhoea. Most infections resolve with fluid and electrolyte replacement, although antibiotic treatment may be necessary in severe cases. The most commonly used antibiotics are macrolides because high fluoroquinolone resistance often precludes empiric ciprofloxacin use in many regions of the EU [3]. The species most often responsible for human infections are Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli, although Campylobacter upsaliensis and Campylobacter lari are also occasionally implicated. In recent years, other Campylobacter species, including C. concisus, whose pathogenic potential is not fully understood, have been increasingly identified, partly due to improvements in molecular detection or changes in culture conditions [4,5,6].

C. concisus is part of the oral microbiota in many people, making it challenging to define its pathogenic role. The oral cavity serves as its likely natural reservoir, harbouring both virulent strains associated with infectious diarrhoea and non-pathogenic variants [7,8,9]. Colonization of the digestive tract likely occurs when the bacteria are introduced through the oral cavity and swallowed with saliva. Environmental factors such as pH changes and bile presence, as well as the individual’s immune status, influence colonization. Colonization with C. concisus has been observed in animals, such as poultry and pets. Poultry appears to be an important reservoir [8,10].

Understanding the pathogenic potential of C. concisus has progressed slowly due to its demanding growth conditions. Initially studied for its role in periodontal disease, recent research has focused on its involvement in intestinal diseases, including infectious diarrhoea and its potential role in chronic inflammatory bowel diseases. Some studies have associated C. concisus with gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s oesophagus, which may progress to oesophageal carcinoma [11,12,13]. Two distinct pathotypes of C. concisus have been described: the adherent-invasive C. concisus (AICC) and the adherent-toxigenic C. concisus (AToCC), which differ in their virulence mechanisms and are thought to play different roles in disease pathogenesis [14].

C. concisus is a genetically diverse species, with some strains being more pathogenic than others. It can adhere to and invade intestinal epithelial cells, causing inflammation and potential tissue damage. Proposed virulence factors for Campylobacter species include flagella-mediated motility, adhesion to intestinal mucosa, invasion of intestinal cells, secretion systems, and toxin production. However, the exact virulence mechanisms for C. concisus are still not fully understood [7,15,16,17,18].

Studies have shown genetic diversity among C. concisus [19,20] strains through multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and whole genome sequencing (WGS) [20,21,22,23]. WGS is a powerful tool for studying C. concisus, providing detailed genomic data that allow comprehensive analysis of virulence factors, resistance genes, genetic diversity, and plasmids that often carry genes related to antibiotic resistance and virulence. WGS can also be used to construct phylogenetic trees, revealing the evolutionary relationships between strains [24,25,26,27].

This study, the first of its kind in Slovenia, molecularly characterizes C. concisus isolates prospectively collected from patients with community-acquired diarrhoea, using WGS. By analysing the genetic diversity, virulence factors, and plasmid distribution in these strains, it provides a better understanding of the pathogenic potential of C. concisus and the factors that contribute to its ability to cause disease.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

This study included C. concisus isolates prospectively collected between 2016 and 2017 at the Institute of Microbiology and Immunology in collaboration with the Division of Infectious Diseases, University Medical Centre Ljubljana. Stool samples were obtained from adult patients with community acquired infectious diarrhoea (defined as three or more loose stools in 24 h lasting up to 14 days) and control group without diarrhoea [28]. During the prospective observational study, 388 stool samples (246 from adult patients with diarrhoea and 142 from control group) were included in the study protocol, which included standard cultivation in combination with membrane filtration and syndromic molecular testing for diarrheal pathogens. In 137 cases, we isolated at least one of the Campylobacter species, with C. concisus being identified in 59 of these cases (53 in patient group; 6 in control group). Because C. concisus is likely to contribute to the aetiology of gastroenteritis, especially in cases that have no known association with other established pathogens, the 53 isolates from patients were divided into two groups: Group A (N 24), in which only C. concisus was identified as a possible cause of community acquired infectious diarrhoea, Group B (N 29), in which C. concisus was identified together with another pathogen causing infectious diarrhoea (C. jejuni/C. coli, Salmonella spp., Aeromonas spp., Shigella/EIEC, Clostridioides difficile, Cryptococcus spp., Giardia intestinalis, norovirus, astrovirus, rotavirus A or adenovirus F40/41).

2.2. C. concisus Isolation and Identification

To isolate C. concisus from faeces, we used a cultivation method on a non-selective culture medium containing tryptose and sheep blood (Tryptic Soy Blood Agar, Oxoid, Wesel, Germany), following prior membrane filtration of the stool according to the modified Cape Town protocol [29,30,31]. For membrane filtration, polycarbonate membrane filters with a diameter of 47 mm and a pore size of 0.60 μm were used (Whatman Nuclepore, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). The plates were incubated at 37 °C in a hydrogen-enriched microaerobic atmosphere for 72 h [31].

All suspicious colonies were identified at the species level using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry on a Microflex Biotyper system (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). The isolates were frozen and stored at −80 °C in a routinely used freezing mix containing Mueller–Hinton broth (Becton Dickinson BBL, Sparks, NV, USA) with 10% glycerol [32].

2.3. DNA Extraction

Genomic DNA for whole genome sequencing (WGS) was extracted using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen Ltd., West Sussex, UK), following the manufacturer’s protocol for Gram-negative bacteria. The extracted DNA was stored at −80 °C until further use. DNA concentrations were measured using the Qubit 3.0 fluorometer in combination with the Qubit 1× dsDNA HS Assay Kit (both Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). DNA purity was assessed based on the absorbance ratios at A260/280 and A260/230 using a NanoDrop 2000/2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Only DNA samples with a concentration greater than 1 ng/µL and an A260/280 ratio between 1.8 and 2.0 were selected for WGS and included in further analysis.

2.4. Whole Genome Sequencing

A total of 54 isolates were sequenced using the NextSeq 2000 system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) using 2 × 151 paired-end reads chemistry, aiming for a minimum coverage of 100×. Preparation of genomic DNA libraries was performed with the Illumina DNA Prep workflow (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.5. Bioinformatic Analysis

Acquired raw reads were filtered and trimmed using Fastp v0.23.2 [33]. The quality of both raw and trimmed reads was assessed with FastQC v0.11.9. Raw reads were assembled into contigs using SPAdes v3.15.5 with default parameters [34]. Quast v5.2.0 [35] and BUSCO v5.4.4 [36] were used for quality assessment of assembled genomes. The minimum threshold for a quality assembly was set at N50 score above 20,000, total number of contigs < 500, genome size within 10% of the reference genomes for each of the genomospecies, and BUSCO completeness of more than 95%. For further analyses, isolates were separated into two distinct genomospecies (GS1 and GS2) of C. concisus (16) based on GC content and genome size. FastANI v1.34 was used to perform pairwise average nucleotide identity (ANI) analysis on all the isolates to further confirm the distinction between genomospecies.

Assemblies were annotated using Prokka v1.14.6 [37], using the protein content of completed C. concisus genomes ATCC 33237 (GS1 (GCF_001298465.1)) and P1CDO3 (GS2 (GCF_003048685.2)) as references for genomospecies 1 and 2, respectively. Pangenome analysis for each of the genomospecies as well as all the isolates together, was performed using Roary v3.13.0 [38]. Analysis of gene homology was performed using zDB software v1.3.10 [39], which employs the orthogroup inference algorithm OrthoFinder [40] as well as Pfam domain analysis and COG (Clusters of Orthologous Genes) annotations.

2.6. MLST and Phylogenetic Analysis

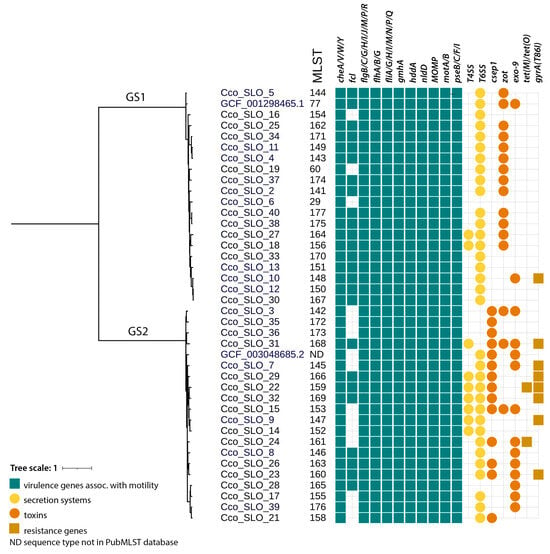

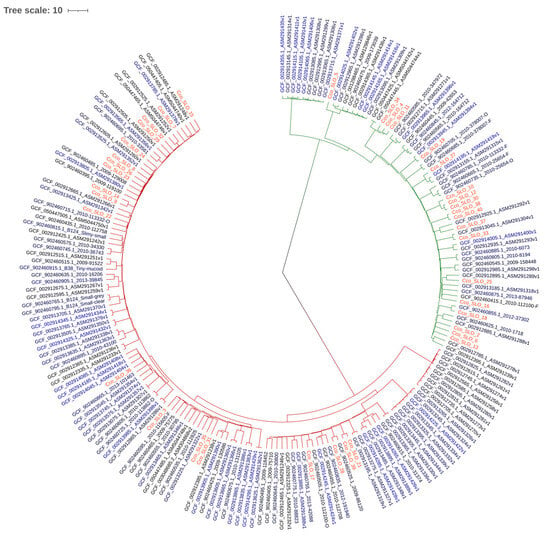

Sequence typing was performed using PubMLST (17) with the Campylobacter non-jejuni/coli scheme (https://pubmlst.org/organisms/campylobacter-non-jejunicoli (accessed on 16 July 2024)). The C. concisus/curvus scheme is based on seven loci: aspA, atpA, glnA, gltA, glyA, ilvD, pgm. Two phylogenetic trees were constructed using ANIclustermap v2.0.1, based on average nucleotide identity, and visualized with iTOL [41]. The distinction between genomospecies within our samples is presented in Figure 1, while Figure 2 shows the phylogenetic similarity and distribution of Slovenian strains in comparison to European C. concisus genomes available in GenBank database.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree with MLST, with distribution of C. concisus virulence genes (green rectangle), secretion systems (yellow circle), toxins (orange circle), and resistance genes (brown rectangle).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of Slovenian C. concisus isolates and available European isolates. Dark red branches represent GS2, green branches represent GS1, and Slovenian isolates are marked in red.

2.7. Analysis of Antimicrobial Resistance, Virulence-Associated Genes and Plasmids

Genomic sequences were analysed with the CARD Resistance Gene Identifier [42] to determine the presence of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes and resistance-associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms.

A list of several virulence factors, previously mentioned in the literature for C. concisus, was created, along with select virulence-related genes of C. jejuni, listed in the Virulence Factor Database. Due to high genetic diversity among homologous genes in C. concisus, OrthoFinder was used to identify homologous gene clusters across all the genomes to determine the presence of chosen genes of interest. The presence of plasmids was assessed in two ways. First we used MOBsuite [43] to reconstruct and type plasmids; to avoid possible false negative results due to lacking databases for C. concisus plasmids, we checked the assembly graphs of each isolate with the Bandage visualization tool and looked for circular, closed contigs, not connected to the chromosomal contigs. Putative plasmid sequences were analysed with the blastn tool on the NCBI website, using the core_nt database. In cases in which there were no results with high reliability (coverage and identity scores above 90%), the plasmids were classified as novel.

Pathotypes were defined based on the presence of Exotoxin 9 (Exo9) and Zonula occludens toxin (Zot). Adherent-Invasive C. concisus, AICC is associated with chronic intestinal disease. In contrast, Adherent-Toxigenic C. concisus (AToCC) strains, which carry the zot gene, have been frequently isolated from patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) [44].

2.8. Statistical Analyses

To evaluate associations between the variables observed, we used the chi-squared (χ2) test. We applied the test under standard assumptions of independent observations and adequate expected cell counts. When assumptions were not met, we used Fisher’s exact test for small samples. Statistical significance was assessed using two-sided p-values with a threshold of p ≤ 0.05. All analyses were performed in IBM® SPSS® for Windows version 27 (SPSS Inc., IBM Company, Armonc, NY, USA) and Excel® for Windows® (MicrosoftTM).

3. Results

In total, 59 isolates of C. concisus were obtained from stool samples and stored at –80 °C. We were only able to successfully revive 54 out of 59 isolates. Of the 54 draft genome assemblies, 40 passed all the quality checks and were used for further analysis; 16 from Group A and 22 from Group B. There were no statistically significant differences in patient age between the two groups. Patients in Group A reported blood in stool less frequently (0% vs. 18.2%, p = 0.007), had less vomiting (62.5% vs. 45.5%, p = 0.034), were more likely to be afebrile (56.3% vs. 27.3%, p = 0.014), and showed lower inflammatory markers with lower CRP levels (CRP > 52.0: 25% vs. 63.6%, p = 0.021) and a lower rate of leucocytosis (>7.75: 56.3% vs. 68.2%, p = 0.048), compared with Group B. There were no differences in stool frequency between the groups. In Group B, bacterial pathogens were the most commonly detected, including Campylobacter jejuni (20.7%), Salmonella spp. (20.7%), and Shigella spp. (6.9%), followed by viruses, primarily Norovirus (13.8%) and Rotavirus (13.8%). Parasites were identified in only one case (3.4% Giardia intestinalis).

The comparison of C. concisus isolates did not reveal significant differences between the two patient groups, except for the presence of Zot (Table 1). Isolates from Group A were predominantly assigned to GS2 (56.3% [9/16]), and those from group B to GS1 (54.5% [12/22]). Only two previously reported STs were identified within GS1: ST29 and ST60. The remaining isolates were classified as novel STs (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Association between genomospecies/virulence genes and Group A and B in Campylobacter concisus isolates.

3.1. Genomic Characteristics of C. concisus Isolates

Based on GC content, genome size, and ANI (Supplementary Tables S1–S3), we were able to divide the isolates into two distinct groups, corresponding to genomospecies GS1 and GS2. The results of the ANI analysis ranged from 94% to 99.8% within the same genomospecies, and around 88% to 89% when compared to other genomospecies.

3.2. MLST and Phylogenetic Analysis of C. concisus Isolates

MLST analysis revealed a high diversity of C. concisus. In each group, only one previously known sequence type (ST) was identified (ST29 in A and ST60 in B), whereas all other STs were novel (Figure 1). All the novel alleles and sequence types were deposited to the Campylobacter non-jejuni/coli scheme on PubMLST.

A phylogenetic tree was created by comparing the genomes of Slovenian C. concisus isolates with European C. concisus isolates available in the GenBank database (Figure 2).

3.3. Analysis of Plasmids in Draft C. concisus Genomes

Plasmid analysis of 40 draft C. concisus genomes revealed the presence of one or more plasmids in 15 C. concisus isolates (Table 2), mostly belonging to GS2 (11/15). There were no significant differences in the presence of plasmids between patients from Groups A and B (Table 1). In total, nine novel plasmids and six known plasmids (pADS1, pSMA1, pCCON16, pCCON31, pTJ3, and pICON) were identified (Table 2). Novel plasmids were found in both, GS1 and GS2, whereas known plasmids were only found in GS2.

Table 2.

Characterization of detected plasmids in C. concisus isolates.

3.4. Presence of Virulence and Resistance Genes

Analysis of the draft genomes of C. concisus revealed the presence of many virulence genes important for immune modulation, motility, secretory systems, or toxin production. The most prevalent virulence genes were those associated with motility, particularly genes related to chemotaxis (cheA, cheV, cheW, cheY), and flagellar structure (flgB, flgC, flgG, flgH, flgJ, flgM, flgP, flgR, flhA, flhB, flhG, fliA, fliG, fliH, fliI, fliM, fliN, fliP, fliQ), which were present in all isolates. In addition, two notable toxins were identified: Exo9 and Zot toxin; among 40 isolates 10 AICC (4 Group A, 6 Group B), 12 AToCC (2 Group A, 10 Group B), 3 AICC/AToCC pathotypes were found (3 Group B), with 13 without Exo9 and Zot toxin genes. Moreover, two important secretion systems, the T4SS and T6SS, were also identified in 9 and 34 isolates, respectively (Table 1). In addition, T3SS was present in all isolates.

Regarding antimicrobial resistance, no mutations associated with erythromycin resistance were found in the 23S rRNA gene (rrnA2075G). Nine isolates carried the gyrA T86I (C257T) mutation, which is known to confer resistance to fluoroquinolones. Two isolates harboured the tet(O) gene, conferring tetracycline resistance, and one isolate carried the tet(M) gene.

4. Discussion

This study used WGS analysis to investigate the genomic characteristics, phylogenetic distribution, presence of plasmids, and virulence factors in C. concisus, isolated from Slovenian patients with community-acquired infectious diarrhoea. In total, 59 isolates were obtained; however, only 54 were successfully revived, possibly due to the suboptimal routinely used freezing mix composition for C. concisus with a slightly lower concentration (10%) of cryoprotectant glycerol [32,45].

MLST analysis was consistent with previous findings that nearly all isolates represent unique STs [20]. Only two previously reported STs were identified within GS1—namely, ST29 and ST60—and the remaining isolates were classified as novel STs. GS2 contained only novel STs. This observation indicates high genetic diversity. Prior work suggests that GS2 may be better adapted to the human gut and more often associated with disease [22,44,46]. The phylogenetic analysis showed that Slovenian isolates are interdispersed with other European isolates with no discernible geographic pattern.

In Campylobacter spp., plasmids commonly carry antibiotic resistance determinants. In some C. jejuni lineages, plasmids such as pVir harbour virulence-associated genes and therefore influence their pathogenicity [27]. In addition, plasmids facilitate horizontal gene transfer. The extent and impact of plasmid-borne virulence in C. concisus remain less well defined. Plasmids may enhance adaptability and perhaps virulence, but their role likely varies by species and strain. In this study, plasmids were less frequently present in GS1 and more commonly found in GS2. Some isolates harboured multiple plasmids.

A number of small, high-copy-number plasmids were previously identified in C. concisus by Liu et al. [47], including pSma1 (~1.3 kb) with two ORFs and an estimated copy number of about 60 per cell. pSma1 and related small plasmids were detected more frequently in strains from ulcerative colitis (UC) patients that required surgical intervention due to the severity of their disease. Specifically, this plasmid was found in approximately a third of UC patients who underwent surgery, compared to a lower prevalence in Crohn’s disease patients and healthy controls [47]. Despite this association, the role of pSma1 in pathogenesis remains to be determined. pSma1 was found in two isolates from Group A belonging to GS2.

pADS1 has been reported as a plasmid in C. concisus in comparative genomics studies, but detailed functional characterization is lacking. References to pADS1 typically occur within broader analyses of C. concisus genomic diversity [47], and its role in pathogenesis remains to be clarified. Similarly, there are few available data on the pTJ3 plasmid. One isolate had both the T4SS and T6SS, whereas the other had the genes for Exo9 and Zot toxins. Both isolates had the csep1 gene, which encodes a secreted enterotoxin homolog [10].

The pCCON16 plasmid was found in three GS2 isolates. It has been previously described as one of the most important plasmids in C. concisus strains, particularly in C. concisus reference strain ATCC BAA-145 [44]. It encodes genes that can be involved in C. concisus interactions with its host, contributing to its pathogenicity. In some cases, certain genes encoded on pCCON16 were also found to be integrated into the genome of different C. concisus strains, such as the AICC strain UNSWCD, potentially indicating genomic variation and adaptability of the plasmid [16]. The plasmid contains an origin of replication with tandem repeats, typical of plasmids, which help ensure its stable maintenance within bacterial populations [44].

The pCCON31 plasmid, found in one isolate, is one of the two plasmids (along with pCCON16) present in some C. concisus strains that shows lower levels of conservation and synteny when compared to other plasmids, such as the UNSWCD plasmid [16].

The pICON plasmid, found in C. concisus strains associated with IBD, including Crohn’s disease, was found in only two isolates. It contains a gene known as csep1, which encodes a secreted enterotoxin homolog. This plasmid is present in some strains of C. concisus from patients with active Crohn’s disease, especially those with small bowel complications. Studies have found that the csep1 gene is more frequently found in strains from patients with active Crohn’s disease compared to healthy controls [10].

Interestingly, the previously described plasmids (pCCON16, pSma1, pADS1, pCCON31, pTJ3, and pICON) were identified in both Groups A and B, but always in GS2 isolates. This is supported by previous research because these plasmids are predominantly but not exclusively found in GS2 [47]. Two of them (pSma1 and pICON) are better studied and associated with specific diseases, pSma1 with UC and pICON with Crohn’s disease.

Plasmids in C. concisus contribute to virulence by carrying various virulence genes, such as exo9. The gene exo9 was identified on a 30 kb plasmid found exclusively in highly invasive strains (AICC), which are associated with chronic intestinal disease. In contrast, the plasmid location of the zot gene (characteristic of AToCC strains) has not been conclusively confirmed in the literature [14,22]

In addition to these toxins, C. concisus produces virulence factors such as FlaC and CadF, secreted through the flagellar system, and some strains possess the T4SS and T6SS, enhancing their ability to adhere to and invade host cells [7,14,18,48].

The distribution of Zot and Exo9 toxin was evaluated across the C. concisus isolates. The Zot toxin, which disrupts tight junctions in epithelial cells and increases intestinal permeability [49,50], was identified in 15 C. concisus isolates: two in Group A and 13 in Group B. A statistically significant difference between the two groups was observed for the presence of Zot (p = 0.004; Table 1), with a higher prevalence in Group B (59.1%) compared to Group A (12.5%). In this study zot was primarily associated with GS1, which is consistent with previous findings [22,23]. Mahendran et al. [49] also reported a higher prevalence of the zot gene in strains from patients with IBD, and described several polymorphisms in the gene, suggesting functional variability among strains.

The Exo9 toxin, which is involved in disrupting host cell functions [51,52], was identified in 12 C. concisus isolates, mostly in Group B, but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.457; Table 1). It was associated with GS2 as previously reported [16,23].

This finding may reflect different pathogenic strategies between C. concisus genomospecies: one is that GS1 isolates may contribute to disease through epithelial barrier disruption due to Zot toxin, and the other is that GS2 isolates may rely on invasion and cytotoxicity because of Exo9 [14]. Deshpande et al. demonstrated that distinct C. concisus pathotypes induce unique global transcriptomic responses in intestinal epithelial cells, supporting the idea that genomic heterogeneity translates into functional and pathogenic diversity [14].

Three isolates (all from Group B) had genes for both Zot and Exo9 toxins, and all three belonged to GS2. The presence of both toxins in GS2 isolates is rare but has been reported previously [16,22,23]. Simultaneous presence could indicate enhanced virulence, because these isolates may combine barrier-disrupting activity with host cell cytotoxicity and invasion. Such isolates could be of particular clinical relevance and may represent a more pathogenic subtype within the C. concisus population. The patients with these three isolates containing both toxins also harbored well-established enteric pathogens (Salmonella enteritidis, Shigella flexneri type 6 and Rotavirus), which were presumed to be the primary etiological agents of their community acquired infectious diarrhoea. Most published work on Zot and Exo9 toxins positive C. concisus isolates relates to chronic intestinal disease (IBD, microscopic colitis) rather than acute infectious gastroenteritis [7,8,22].

In addition to these toxins, the presence of secretory systems was analysed [22]. The T3SS was detected in all isolates, and T5SS was not detected. The T6SS is a more recently discovered secretion system that plays a dual role in both interbacterial competition and host–pathogen interactions [53,54]. The T6SS is also crucial for virulence through its ability to inject effector proteins into host cells. These effectors can induce host cell death or disrupt normal cellular functions, further promoting bacterial survival and dissemination. Pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Vibrio cholerae utilize the T6SS to establish infections by targeting host immune cells or manipulating local tissue structures, thus exacerbating inflammation and promoting tissue damage. This ability to eliminate competing microbiota enhances the survival and establishment of pathogens in the host environment, which is critical for the persistence of infection [53,55,56]. Our isolates with the T6SS belonged to both Groups A and B, and no statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups (p = 0.635; Table 1).

Importantly, 8/40 isolates with the T4SS also carried the T6SS, reinforcing the concept of combined secretion systems in particular isolates [22], and no statistically significant difference was observed between Groups A and B (p = 0.350, Table 1). The T4SS is known to mediate DNA and protein transfer and to play a major role in bacterial adaptation and virulence [57]. The presence of the T4SS and T6SS supports the idea that certain Campylobacter isolates possess complex virulence strategies combining interbacterial antagonism with DNA/protein transfer capabilities.

This study also analysed the presence of antimicrobial resistance genes in C. concisus isolates. No macrolide resistance genes were identified in any of the isolates. Kaakoush et al. reported a low level of resistance to erythromycin (≈2.5%) among a population of 73 isolates [7]. Mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) of the gyrA gene were detected in nine isolates, such as the C257T substitution leading to the Thr-86-Ile amino acid change, which is the predominant fluoroquinolone resistance determinant [58]. Six out of nine were from GS2, indicating the presence of fluoroquinolone resistance in a subset of the population. Tetracycline resistance was confirmed in three isolates. Two of these harboured the tet(O) gene, which encodes a ribosomal protection protein, and the third carried the tet(M) gene, also associated with ribosomal protection and resistance to tetracyclines. The detection of these genes, particularly tet(O) and tet(M), raises the possibility of horizontal gene transfer events occurring within the intestinal microbiota. Overall, our results indicate that although a proportion of C. concisus isolates have acquired resistance to ciprofloxacin and tetracycline, the species remains largely susceptible to macrolides. Nevertheless, the presence of resistance genes underscores the importance of continued surveillance and further investigation into the resistome of C. concisus.

Our study provided insight into the genotypic variability of clinical C. concisus isolates from patients with community-acquired infectious diarrhoea in Slovenia. We found that the genetic heterogeneity of clinical C. concisus isolates is high. The gene profiles for virulence factors are not directly linked to the determination of ST but are associated with GS. By identifying plasmids and genes associated with resistance and virulence factors, we gained a better understanding of C. concisus virulence.

5. Conclusions

This study provides the first in-depth whole-genome sequencing analysis of C. concisus isolates from Slovenian patients with infectious diarrhoea. C. concisus isolates from patients, in whom no other gastrointestinal pathogens were detected, were predominantly assigned to genomospecies GS2, characterized by larger genomes, higher GC content, and a greater number of coding regions. These isolates showed a higher prevalence of plasmids associated with virulence, including the exo9 toxin gene and the conjugative T4SS and T6SS, suggesting enhanced pathogenic potential and adaptability. In contrast, C. concisus isolates from patients, in whom other gastrointestinal pathogens were detected simultaneously, were mainly from genomospecies GS1, and they had smaller genomes and more frequent presence of the zot toxin gene. The majority of isolates harboured the T6SS, emphasizing its fundamental role in C. concisus biology. This genomic insight advances the understanding of C. concisus pathogenicity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/microorganisms14010087/s1, Table S1. Genome information data; Table S2. Pangenome information; Table S3. Average nucleotide identity matrix.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.K., M.P., T.M. and T.T.; methodology, R.K., M.P., T.M., T.T. and A.C.Š.; software, A.C.Š.; validation, R.K., A.C.Š., T.T., T.M. and M.P.; formal analysis, R.K., A.C.Š., T.T., T.M., M.P. and A.K.; investigation, R.K., T.M., M.P., T.T. and A.C.Š.; data curation, A.C.Š., R.K. and M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.K.; writing—review and editing, M.P., T.T., T.M., T.K. and T.L.Z.; visualization, A.C.Š.; supervision, M.P., T.T. and T.M.; project administration, R.K., T.M. and M.P.; funding acquisition T.M. and T.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (grant P3-0083).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Slovenian National Medical Ethics Committee (No. 143/12/15—approved on 15 December 2015 and No. 50/03/16—approved on 1 May 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all persons enrolled in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The genomic data associated with this study can be found under the BioProject accession number PRJEB98669.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GS1 | Genomospecies 1 |

| GS2 | Genomospecies 2 |

| AICC | Adherent-invasive C. concisus |

| AToCC | Adherent-toxigenic C. concisus |

| T6SS | Type VI secretion system |

| T4SS | Type IV secretion system |

| Zot | Zonula occludens toxin |

| Exo9 | Exotoxin9/DnaI toxin |

| WGS | Whole-genome sequencing |

| MLST | Multilocus sequence typing |

References

- The European Union One Health 2023 Zoonoses Report|EFSA. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/9106 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Grilc, E.; Praprotnik, M.; Trkov, M.; Kotnik, E.; Berce, I.; Car Drnovšek, T. Intestinal Communicable Diseases and Zoonoses in Slovenia in 2023. Epidemiological Surveillance of Communicable Diseases in Slovenia. Available online: https://nijz.si/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Crevesne-nalezljive-bolezni-in-zoonoze-v-Sloveniji-v-letu-2023.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025). (In Slovene).

- European Food Safety Authority; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. The European Union Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in Zoonotic and Indicator Bacteria from Humans, Animals and Food in 2022–2023. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François, R.; Yori, P.P.; Rouhani, S.; Siguas Salas, M.; Paredes Olortegui, M.; Rengifo Trigoso, D.; Pisanic, N.; Burga, R.; Meza, R.; Meza Sanchez, G.; et al. The Other Campylobacters: Not Innocent Bystanders in Endemic Diarrhea and Dysentery in Children in Low-Income Settings. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastovica, A.J. Emerging Campylobacter spp.: The Tip of the Iceberg. Clin. Microbiol. Newsl. 2006, 28, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, C.; Schweiger, A.; von Steiger, N.; Droz, S.; Marschall, J. Campylobacter concisus Pseudo-Outbreak Caused by Improved Culture Conditions. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 660–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaakoush, N.O.; Mitchell, H.M. Campylobacter concisus—A New Player in Intestinal Disease. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaakoush, N.O.; Castaño-Rodríguez, N.; Mitchell, H.M.; Man, S.M. Global Epidemiology of Campylobacter Infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 687–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, D.; Iraola, G. Pathogenomics of Emerging Campylobacter Species. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00072-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Ma, R.; Tay, C.Y.A.; Octavia, S.; Lan, R.; Chung, H.K.L.; Riordan, S.M.; Grimm, M.C.; Leong, R.W.; Tanaka, M.M.; et al. Genomic Analysis of Oral Campylobacter concisus Strains Identified a Potential Bacterial Molecular Marker Associated with Active Crohn’s Disease. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akutko, K.; Matusiewicz, K. Campylobacter concisus as the Etiologic Agent of Gastrointestinal Diseases. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2017, 26, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, S.; Furrie, E.; Macfarlane, G.T.; Dillon, J.F. Microbial colonization of the upper gastrointestinal tract in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 45, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaakoush, N.O.; Castaño-Rodríguez, N.; Man, S.M.; Mitchell, H.M. Is Campylobacter to esophageal adenocarcinoma as Helicobacter is to gastric adenocarcinoma? Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshpande, N.P.; Wilkins, M.R.; Castaño-Rodríguez, N.; Bainbridge, E.; Sodhi, N.; Riordan, S.M.; Mitchell, H.M.; Kaakoush, N.O. Campylobacter concisus Pathotypes Induce Distinct Global Responses in Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Ma, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. The Clinical Importance of Campylobacter concisus and Other Human Hosted Campylobacter Species. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, N.P.; Kaakoush, N.O.; Wilkins, M.R.; Mitchell, H.M. Comparative Genomics of Campylobacter concisus Isolates Reveals Genetic Diversity and Provides Insights into Disease Association. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrencic, P.; Kaakoush, N.O.; Huinao, K.D.; Kain, N.; Mitchell, H.M. Investigation of Motility and Biofilm Formation by Intestinal Campylobacter concisus Strains. Gut Pathog. 2012, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaakoush, N.O.; Man, S.M.; Lamb, S.; Raftery, M.J.; Wilkins, M.R.; Kovach, Z.; Mitchell, H. The Secretome of Campylobacter concisus. FEBS J. 2010, 277, 1606–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalischuk, L.D.; Inglis, G.D. Comparative Genotypic and Pathogenic Examination of Campylobacter concisus isolates from Diarrheic and Non-Diarrheic Humans. BMC Microbiol. 2011, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, H.L.; Nielsen, H.; Torpdahl, M. Multilocus Sequence Typing of Campylobacter concisus from Danish Diarrheic Patients. Gut Pathog. 2016, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.G.; Chapman, M.H.; Yee, E.; On, S.L.W.; McNulty, D.K.; Lastovica, A.J.; Carroll, A.M.; McNamara, E.B.; Duffy, G.; Mandrell, R.E. Multilocus Sequence Typing Methods for the Emerging Campylobacter Species C. Hyointestinalis, C. Lanienae, C. Sputorum, C. Concisus, and C. Curvus. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemmell, M.R.; Berry, S.; Mukhopadhya, I.; Hansen, R.; Nielsen, H.L.; Bajaj-Elliott, M.; Nielsen, H.; Hold, G.L. Comparative Genomics of Campylobacter concisus: Analysis of Clinical Strains Reveals Genome Diversity and Pathogenic Potential. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, K.F.; Méric, G.; Nielsen, H.L.; Pascoe, B.; Sheppard, S.K.; Thorlacius-Ussing, O.; Nielsen, H. Molecular Epidemiology and Comparative Genomics of Campylobacter concisus Strains from Saliva, Faeces and Gut Mucosal Biopsies in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, A.J.; Huq, M.; On, S.L.W.; French, N.P.; Vandenberg, O.; Miller, W.G.; Lastovica, A.J.; Istivan, T.; Biggs, P.J. Genetic Characterisation of Campylobacter concisus: Strategies for Improved Genomospecies Discrimination. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 44, 126187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolley, K.A.; Bray, J.E.; Maiden, M.C.J. Open-Access Bacterial Population Genomics: BIGSdb Software, the PubMLST.Org Website and Their Applications. Wellcome Open Res. 2018, 3, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clausen, P.T.L.C.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Lund, O. Rapid and Precise Alignment of Raw Reads against Redundant Databases with KMA. BMC Bioinform. 2018, 19, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Fernandez, A.; Janowicz, A.; Marotta, F.; Napoleoni, M.; Arena, S.; Primavilla, S.; Pitti, M.; Romantini, R.; Tomei, F.; Garofolo, G.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance, Plasmids, and Virulence-Associated Markers in Human Strains of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli Isolated in Italy. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1293666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotar, T.; Pirš, M.; Steyer, A.; Cerar, T.; Šoba, B.; Skvarc, M.; Poljšak Prijatelj, M.; Lejko Zupanc, T. Evaluation of Rectal Swab Use for the Determination of Enteric Pathogens: A Prospective Study of Diarrhoea in Adults. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, K.F.; Nielsen, H.L.; Thorlacius-Ussing, O.; Nielsen, H. Optimized Cultivation of Campylobacter concisus from Gut Mucosal Biopsies in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gut Pathog. 2016, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachamkin, I.; Nguyen, P. Isolation of Campylobacter Species from Stool Samples by Use of a Filtration Method: Assessment from a United States-Based Population. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 2204–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilmanne, A.; Kandet Yattara, H.M.; Herpol, M.; Vlaes, L.; Retore, P.; Quach, C.; Vandenberg, O.; Hallin, M.; Martiny, D. Multi-Step Optimization of the Filtration Method for the Isolation of Campylobacter Species from Stool Samples. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 38, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feavers, I.M.; Suker, J.; McKenna, A.J.; Heath, A.B.; Maiden, M.C. Molecular analysis of the serotyping antigens of Neisseria meningitidis. Infect. Immun. 1992, 60, 3620–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, S. Ultrafast One-Pass FASTQ Data Preprocessing, Quality Control, and Deduplication Using Fastp. iMeta 2023, 2, e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prjibelski, A.; Antipov, D.; Meleshko, D.; Lapidus, A.; Korobeynikov, A. Using SPAdes De Novo Assembler. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2020, 70, e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikheenko, A.; Prjibelski, A.; Saveliev, V.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A. Versatile Genome Assembly Evaluation with QUAST-LG. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i142–i150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manni, M.; Berkeley, M.R.; Seppey, M.; Simão, F.A.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO Update: Novel and Streamlined Workflows along with Broader and Deeper Phylogenetic Coverage for Scoring of Eukaryotic, Prokaryotic, and Viral Genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 4647–4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.J.; Cummins, C.A.; Hunt, M.; Wong, V.K.; Reuter, S.; Holden, M.T.G.; Fookes, M.; Falush, D.; Keane, J.A.; Parkhill, J. Roary: Rapid Large-Scale Prokaryote Pan Genome Analysis. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3691–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, B.; Pillonel, T.; Carrara, A.; Bertelli, C. zDB: Bacterial Comparative Genomics Made Easy. mSystems 2024, 9, e00473-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emms, D.M.; Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: Phylogenetic Orthology Inference for Comparative Genomics. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent Updates to the Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation Tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, B.P.; Huynh, W.; Chalil, R.; Smith, K.W.; Raphenya, A.R.; Wlodarski, M.A.; Edalatmand, A.; Petkau, A.; Syed, S.A.; Tsang, K.K.; et al. CARD 2023: Expanded Curation, Support for Machine Learning, and Resistome Prediction at the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D690–D699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, J.; Nash, J.H.E. MOB-Suite: Software Tools for Clustering, Reconstruction and Typing of Plasmids from Draft Assemblies. Microb. Genom. 2018, 4, e000206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, N.P.; Kaakoush, N.O.; Mitchell, H.; Janitz, K.; Raftery, M.J.; Li, S.S.; Wilkins, M.R. Sequencing and Validation of the Genome of a Campylobacter concisus Reveals Intra-Species Diversity. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, R.; Adley, C.C. An Evaluation of Five Preservation Techniques and Conventional Freezing Temperatures of −20 °C and −85 °C for Long-Term Preservation of Campylobacter jejuni. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 38, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhang, X.; Chung, H.K.L.; Riordan, S.M.; Grimm, M.C.; Zhang, S.; Ma, R.; Lee, S.A.; Zhang, L. Campylobacter concisus Genomospecies 2 Is Better Adapted to the Human Gastrointestinal Tract as Compared with Campylobacter concisus Genomospecies 1. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Chen, S.; Luu, L.D.W.; Lee, S.A.; Tay, A.C.Y.; Wu, R.; Riordan, S.M.; Lan, R.; Liu, L.; Zhang, L. Analysis of Complete Campylobacter concisus Genomes Identifies Genomospecies Features, Secretion Systems and Novel Plasmids and Their Association with Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Microb. Genom. 2020, 6, mgen000457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddick, L.E.; Alto, N.M. Bacteria Fighting Back—How Pathogens Target and Subvert the Host Innate Immune System. Mol. Cell 2014, 54, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahendran, V.; Tan, Y.S.; Riordan, S.M.; Grimm, M.C.; Day, A.S.; Lemberg, D.A.; Octavia, S.; Lan, R.; Zhang, L. The Prevalence and Polymorphisms of Zonula Occluden Toxin Gene in Multiple Campylobacter concisus Strains Isolated from Saliva of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Controls. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano, A.; Fiorentini, C.; Donelli, G.; Uzzau, S.; Kaper, J.B.; Margaretten, K.; Ding, X.; Guandalini, S.; Comstock, L.; Goldblum, S.E. Zonula Occludens Toxin Modulates Tight Junctions through Protein Kinase C-Dependent Actin Reorganization, in Vitro. J. Clin. Investig. 1995, 96, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaakoush, N.O.; Deshpande, N.P.; Wilkins, M.R.; Tan, C.G.; Burgos-Portugal, J.A.; Raftery, M.J.; Day, A.S.; Lemberg, D.A.; Mitchell, H. The Pathogenic Potential of Campylobacter concisus Strains Associated with Chronic Intestinal Diseases. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e29045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaakoush, N.O.; Castaño-Rodríguez, N.; Day, A.S.; Lemberg, D.A.; Leach, S.T.; Mitchell, H.M. Campylobacter concisus and Exotoxin 9 Levels in Paediatric Patients with Crohn’s Disease and Their Association with the Intestinal Microbiota. J. Med. Microbiol. 2014, 63, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnetti, J.; Seth-Smith, H.M.B.; Ursich, S.; Reist, J.; Basler, M.; Nickel, C.; Bassetti, S.; Ritz, N.; Tschudin-Sutter, S.; Egli, A. Clinical Impact of the Type VI Secretion System on Virulence of Campylobacter Species during Infection. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pena, R.T.; Blasco, L.; Ambroa, A.; González-Pedrajo, B.; Fernández-García, L.; López, M.; Bleriot, I.; Bou, G.; García-Contreras, R.; Wood, T.K.; et al. Relationship Between Quorum Sensing and Secretion Systems. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Tian, M.; Wang, Z.; Shu, R.-D.; Zhao, M.-Y.; Chen, W.-D.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; et al. The Phospholipase Effector Tle1Vc Promotes Vibrio Cholerae Virulence by Killing Competitors and Impacting Gene Expression. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2241204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolle, A.-S.; Meader, B.T.; Toska, J.; Mekalanos, J.J. Endogenous Membrane Stress Induces T6SS Activity in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2018365118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohmann, E.; Christie, P.J.; Waksman, G.; Backert, S. Type IV Secretion in Gram-Negative and Gram-Positive Bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 2018, 107, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, K.; Osek, J. Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanisms among Campylobacter. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 340605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.