Abstract

The human gut microbiota plays a key role in health and disease across the lifespan and is shaped by complex intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Dysbiosis is increasingly recognized as a contributor to a wide range of clinical conditions, with diarrhoea—particularly antibiotic-associated diarrhoea—representing an early clinical marker of microbiota disruption. This narrative review summarizes current evidence on the probiotic yeast Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 and its clinical applications in both paediatric and adult populations. Available clinical data support its safety and efficacy in the prevention and management of gastrointestinal disorders, particularly diarrhoeal conditions, and suggest a potential role in promoting microbiota resilience. Key mechanisms of action, safety considerations, and findings from randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses are discussed. However, current data remains limited by heterogeneity among studies and a lack of long-term, mechanistic data, highlighting the need for further well-designed studies to clarify its role across different clinical settings.

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, research on the human microbiota has experienced significant growth, attracting increasing attention not only within the scientific community but also among the public. This heightened attention stems from the recognition of the microbiota’s potential for medical applications, encompassing preventive measures and new therapeutic strategies across a diverse array of diseases [1].

The human microbiota has emerged as a crucial factor in health and disease, often conceptualized as the body’s “last organ” due to its vast genetic and metabolic capabilities [1,2]. A 70 kg adult is estimated to harbour approximately 3.8 × 1013 bacterial cells, a number comparable to human cells, forming a highly integrated ecosystem shaped by hundreds of millions of years of host–microbe co-evolution [2]. The gut microbiome encompasses not only bacteria but also archaea, other eukaryotic microorganisms and fungi [1]. The gut “mycobiome”, though representing only a small fraction of the intestinal microbiota (approximately 0.01–0.1%), plays a relevant role in host health and immunity due to the distinct immunoregulatory properties of fungal cells. Factors such as diet, antimicrobial exposure, and age can disrupt fungal composition, contributing to dysbiosis and intestinal inflammation. Interactions between gut fungi, bacteria, and the host immune system are therefore central to intestinal homeostasis, with fungal components involved in immune pathways including Th17 cell activation [3]. Although fungi are now widely recognized as integral members of the microbiome, questions remain regarding the inclusion of other components such as phages, viruses, and mobile genetic elements [1].

Within this evolving framework, the gut microbiome is increasingly appreciated as a complex ecosystem that contributes to host development, metabolic regulation, and physiological homeostasis through essential microbial activities, including nutrient processing, fibre fermentation, neurotransmitter production, and the synthesis of vitamins and short-chain fatty acids [1,4,5,6,7]. Furthermore, the gut microbiota provides defence against pathogens, strengthens mucosal barrier integrity, and modulates local and systemic immune responses [5,6,7].

Through these mechanisms, microbial signals extend beyond the intestine, mediating interconnected “gut-organ axes” that impact the brain, liver, lungs, kidneys, and systemic immunity [6]. Generally, gut dysbiosis is characterised by diminished microbial diversity, a reduction in beneficial or keystone microbes within the core microbiota, and the proliferation of opportunistic pathogens [8,9]. Dysbiosis can manifest as disturbances in both structural composition and the functional performance of the gut microbiome. While some of these changes may be temporary and reversible, others can become persistent and irreversible. The outcome of these changes is influenced by the nature of the perturbation as well as by the baseline composition and functionality of the gut microbiota and host-related determinants [10,11,12]. When these alterations become irreversible, they may adversely impact host health, contributing to impaired gut barrier function and a broad spectrum of conditions, including gastrointestinal, hepatic, renal, metabolic, cardiovascular, and neurological disorders, as well as autoimmune diseases, diabetes, and liver cirrhosis [11,13,14]. Additionally, dysbiosis has been correlated with oxidative stress, elevated intestinal permeability, and systemic immune dysregulation [7,15].

Among the major drivers of gut dysbiosis, prolonged and repeated antibiotic treatment plays a central role. Antibiotic use profoundly influences gut microbiota composition and function, with evidence suggesting that its effects may range from transient perturbations to long-lasting alterations, potentially impacting microbiota resilience depending on the duration, frequency, and context of therapy [12]. Antibiotic exposure induces several alterations in gut microbiota, leading to dysbiosis characterized by loss of beneficial taxa, reduced microbial diversity, and overgrowth of opportunistic microorganisms. These changes promote intestinal inflammation, impair fluid and nutrient absorption, and contribute to the development of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (AAD) [15].

Restoring microbial equilibrium has become a primary therapeutic objective, with probiotics—defined as “live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host”, being among the most thoroughly researched approaches [16,17].

This narrative review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the clinical implications of gut dysbiosis, with a particular focus on the probiotic Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 (S. boulardii). By summarizing current evidence from both paediatric and adult populations, this review evaluates the role of S. boulardii in the prevention and management of gastrointestinal disorders in which dysbiosis contributes to disease pathogenesis, such as AAD. In this context, the efficacy and safety of S. boulardii as an adjuvant to Helicobacter (H.) pylori eradication therapies are also examined.

2. Probiotics: Definition, Mechanisms of Action, and Regulation

The gut microbiota accounts for approximately 0.2–2 kg of body weight and is predominantly localised in the colon, where microbial density reaches about 1011 to 1012 organisms per millilitre [18]. Alterations to the intestinal microbiota induced by dysbiosis significantly affect the host’s metabolic equilibrium. To facilitate the restoration of the gut microbiome after dysbiosis, or to promote a healthy microbial balance, several exogenous interventions have been proposed to enhance its resilience. Among these, probiotics represent a well-established strategy [19]. Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer measurable health benefits by promoting gut microbiota homeostasis and limiting the production of deleterious metabolites from pathogenic species [16].

Probiotics exert their effects through multiple mechanisms, including modulation of environmental pH, production of antimicrobial compound such as bacteriocins, competition with pathogens for essential nutrients, and stimulation of host immune responses [4]. In addition to limiting microbial overgrowth and preventing the onset of dysbiosis, probiotics provide further advantages These include the fermentation of non-digestible fibres to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), the biosynthesis of vitamins and metabolic cofactors, the promotion of anti-inflammatory cytokines and T-cell activity, and the strengthening of intestinal barrier integrity via the upregulation of tight junction proteins. Moreover, by sustaining microbial diversity, functional redundancy, and metabolic flexibility, probiotics enhance the resilience and long- term stability of the gut ecosystem [6]. Evidence suggests that the timely administration of an appropriate dosage of probiotics, either at the initiation of antibiotic therapy or within 48 h, can prevent or reduce the consequences of antibiotic-associated dysbiosis, such as diarrhoea, by supporting gut microbiota resilience and facilitating a return to the pre-antibiotic state [20].

The field of probiotics is experiencing rapid growth; however, several investigations have raised concerns regarding both the microbiological quality and the accuracy of labelling information on many probiotic products [21,22]. For probiotic formulations to confer significant health benefits, they must contain an adequate quantity of well-characterised microbial species and strains, ensuring their viability throughout transit within the gastrointestinal tract [23]. International guidelines consistently emphasise the need for rigorous quality control of probiotic products, including accurate strain identification and confirmation of microbial viability [16,24].

The regulatory framework governing probiotics varies widely across countries and depends on their classification as drugs, dietary supplements, or functional foods, resulting in substantial differences in approval requirements, quality standards, and clinical validation. Probiotic drugs are subject to stringent pre- and post-marketing controls, whereas dietary supplements and functional foods follow less rigorous regulatory pathways. Overall, this regulatory heterogeneity contributes to significant variability in the compositional quality and reliability of commercially available probiotic formulations [23].

European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Health Organization (FAO/WHO) recommend clear product labelling that specifies the genus, species, strain, and the minimum number of viable microorganisms guaranteed at the end of shelf life [16,24].

Within the Italian regulatory framework, extensive experience in the field, together with the considerable number and complexity of probiotic preparations available, has resulted in stricter requirements compared with other European Union nations. The Italian Guidelines on Probiotics and Prebiotics, initially issued by the Ministry of Health in 2011 and periodically updated, establish explicit criteria to ensure the quality of probiotic products, including safety standards designed to protect consumers. The most recent update, issued in March 2018 [25], delineates the criteria for probiotics designated for human use, such as species- and strain-level identification, the minimum daily dose of viable microorganisms, and the permissible variance between the declared viable cell count on the label and that measured at the conclusion of the product’s shelf life. The effectiveness of probiotic interventions largely depends on the use of high-quality, well-characterized strains [26]. A critical aspect is that probiotic effects are strain-specific, with efficacy influenced by host-related factors such as age, baseline microbiota composition, and environmental conditions; therefore, every strain included in a commercial product must be explicitly validated in its clinical context, as data from one strain cannot be extrapolated to others.

In this context, the use of probiotic formulations registered as medicinal products may provide additional assurances of both strain effectiveness and product quality, owing to their specific and stringent regulatory pathway, distinct from that of dietary supplements or medical devices. Although, extensive research has focused on bacterial probiotics, studies concerning yeast-derived probiotics remain comparatively limited.

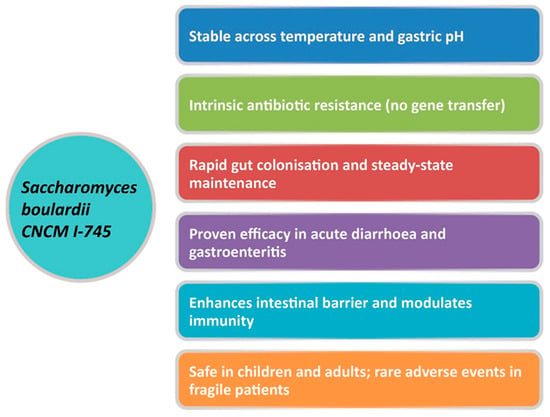

Yeasts naturally possess resistance to antibacterial agents, presenting a distinct advantage as probiotic candidates. S. boulardii CNCM I-745 is a probiotic yeast belonging to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae species, originally identified by Henri Boulard in 1923 [27]. Among yeasts, S. boulardii stands out for its diverse beneficial properties and long-standing clinical use [28]. This non-pathogenic yeast was the first non-bacterial strain to be systematically investigated and applied as a human probiotic, with well-documented efficacy and safety in clinical practice [26]. It differs substantially from bacterial probiotics in terms of size, cell wall architecture, and metabolic functions. Importantly, it is intrinsically resistant to all antibiotics and does not acquire resistance genes, thus allowing its simultaneous administration during antibiotic treatment while maintaining full viability [29]. Pharmacokinetically, it withstands gastric acidity and bile salts, proliferates at 37 °C, reaches a steady state in the intestine within approximately three days, and is eliminated within 3–5 days after discontinuation [26]. S. boulardii employs multiple mechanisms of action, categorized into luminal, trophic, and mucosal- anti-inflammatory signaling effects [30]. Within the intestinal lumen, S. boulardii can interfere with pathogenic toxins and their adherence, interact with the resident microbiota, maintain cellular physiology, and restore short-chain fatty acid levels. Furthermore, S. boulardii may modulate the immune system, both locally within the lumen and systemically [26,30,31,32]. The key features of S. boulardii CNCM I-745 are summarized in Figure 1 [27].

Figure 1.

Unique properties of S. boulardii CNCM I-745. Adapted from Gopalan et al., 2023 [27].

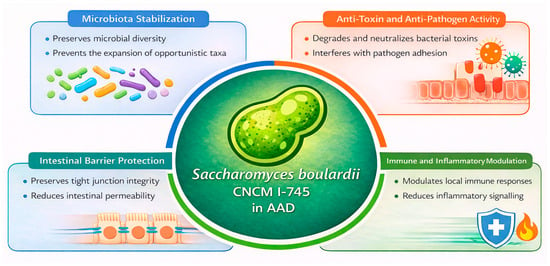

Clinical evidence supports the efficacy of S. boulardii CNCM I-745 in several gastrointestinal disorders, and it is increasingly considered a useful adjunct to antimicrobial therapy. This probiotic has demonstrated both preventive and therapeutic benefits, particularly in AAD, by reducing diarrhoeal incidence and duration [27,28,29,30,31,32]. These clinical effects are supported by multiple mechanisms of action. During antibiotic exposure, S. boulardii CNCM I-745 helps preserve microbiota stability by limiting antibiotic-induced shifts in microbial composition and preventing the expansion of opportunistic taxa [31]. In parallel, it exerts direct anti-toxin activity, including degradation and neutralisation of bacterial toxins, and interferes with pathogen adhesion to the intestinal epithelium [32]. At the mucosal level, S. boulardii reinforces epithelial barrier integrity by protecting tight junctions and reducing intestinal permeability, while also modulating local immune responses and inflammatory signalling pathways (Figure 2) [31,32]. Owing to this multifaceted mode of action, together with its favourable safety profile and extensive clinical validation, S. boulardii CNCM I-745 is widely regarded as a preferred probiotic option for the prevention and management of AAD and paediatric acute gastroenteritis (PAGE) [27].

Figure 2.

Biological Mechanisms Supporting the Use of Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 in AAD. Adapted from Terciolo et al., 2019 [31] and Czerucka D et al., 2019 [32]. Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhoea (AAD).

3. Paediatric Gut Dysbiosis and the Role of Saccharomyces boulardii

The gut microbiota contributes substantially to human health across all stages of life, with its influence being especially pronounced during infancy [33]. The establishment of the infant gut microbiota progresses rapidly during the first months of life, driven by maternal and environmental microbial inputs, and typically reaches a relatively stable configuration by around three years of age [34,35]. However, recent evidence indicates that the maturation of the gut microbiome can extend further, reaching completion only around six years of age in humans [36,37]. During this trajectory, the infant gut microbiota undergoes a stepwise transformation, progressively acquiring the diversity and functional complexity that characterise the adult ecosystem [38]. This developmental period has been defined as a “critical window”, during which the intestinal community remains highly plastic and particularly vulnerable to disruptions such as dysbiosis [39].

Early-life exposure to antibiotics, whether during pregnancy, delivery, lactation, or directly in the infants, profoundly alters microbiota composition and diversity [40,41]. Antibiotics can deplete beneficial groups such as Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes while favouring the expansion of potentially pathogenic taxa including Proteobacteria, Enterococcus, and Klebsiella [42,43]. These disruptions not only reduce overall microbial biodiversity but are also associated with long- term health disorders [44,45].

Antibiotic exposure is strongly associated with diarrhoea [46]. Among the clinical manifestations of early-life dysbiosis, AAD is one of the most frequent and clinically relevant outcomes. It is definite as the occurrence of three or more loose stools within a 24 h period following antibiotic administration. This condition can manifest within hours or up to eight weeks after the start of antibiotic therapy [44]. Its incidence in children ranges from 11% to over 40%, depending on antibiotic class, treatment duration, and host-related factors [47]. These findings highlight the vulnerability of the infant microbiome during this critical window, underscoring the need for careful stewardship of antibiotic use and the potential role of microbiota-supporting interventions such as probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics, and paraprobiotics [48,49]. These recommendations are supported by the most recent international paediatric guidelines, including the 2023 ESPGHAN/European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases (ESPID) guidance on acute gastroenteritis and antibiotic-associated diarrhoea as well as the 2023 World Gastroenterology Organisation (WGO) Global Guidelines on Probiotics and Prebiotics, both of which explicitly list the strain S. boulardii among the evidence-based probiotics recommended for children [50,51]. Importantly, S. boulardii represents the only yeast included among the probiotics recommended by current international guidelines in this setting. Clinical evidence further supports the role of probiotics in reducing the risk and severity of AAD, respiratory tract infections, and allergic manifestations in children [38].

Among these, S. boulardii is specifically recommended for the prevention of AAD in both hospital and outpatient settings, when administered at a daily dose of at least 5 × 109 Colony-Forming Units (CFU), starting at the initiation of antibiotic therapy [52,53]. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of clinical trials have confirmed the strain-specific efficacy of S. boulardii. McFarland et al. analysed 22 randomised controlled trials and observed a significant reduction in AAD with S. boulardii [30]. Abidi corroborated these findings in 300 Indian children, reporting significantly fewer diarrheal episodes in the probiotic group compared with those receiving antibiotics alone [54]. Szajewska et al. synthesized data from 21 randomized controlled trials, demonstrating that the risk of AAD decreased from 20.9% to 8.8% in children treated with S. boulardii [52]. Similarly, another review including 21 studies reported substantially lower rates of diarrhoea in the probiotic group [27].

More recent evidence suggests that both S. boulardii and Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG are among the most effective single-strain probiotics for preventing paediatric AAD [20,55]. Furthermore, a large body of clinical research, supported by systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials, demonstrates the efficacy of S. boulardii in PAGE. Szajewska et al. demonstrated shorter diarrhoea duration, reduced stool frequency, and decreased hospitalisation [52], findings corroborated by Padayachee et al. and Fu et al. [56,57]. Meta-analyses consistently report that S. boulardii is safe in children, with only rare cases of fungaemia reported in severely immunocompromised individuals [52,56,57]. It is important to note that most of the cited clinical evidence has been generated using the well-characterised strain S. boulardii.

4. Adult Dysbiosis and the Role of Saccharomyces boulardii

By three years of age, the gut microbiota reaches an adult-like composition, characterized by the dominance of Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria [58]. In adulthood, it typically exhibits stability and resilience, although its composition can vary among individuals and within the same individual, influenced by factors such as age and medication use [59]. A healthy adult microbiota is characterised by significant taxonomic diversity, high gene richness, and a core community that supports metabolic functions, immune regulation, and protection against pathogens [58]. As individuals age, immunosenescence and dietary changes contribute to microbial shifts, including an increase in Clostridia and Proteobacteria and a reduction in Bifidobacterium, a decline associated with elevated inflammation [60]. These alterations have been correlated with a broad spectrum of diseases, including cardiovascular, metabolic, inflammatory, oncological, respiratory, hepatic, and renal disorders [59,61,62]. In summary, the adult gut microbiota operates as an intricate, resilient ecosystem that remains susceptible to external disturbances, with its disruption representing a significant risk factor across multiple disease domains. Meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials demonstrate that S. boulardii significantly reduces the risk of AAD, compared with control or placebo groups, with moderate effect sizes [30,52,53]. These findings are aligned with the 2023 WGO Global Guidelines on Probiotics and Prebiotics, which list S. boulardii among the evidence-based options for the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in adults [51].

Beyond its clinical efficacy in reducing AAD, supplementation with S. boulardii CNCM I-745 has also been shown to exert beneficial effects on gut microbiota composition and recovery following antibiotic exposure. Probiotic co-administration during and after amoxicillin–clavulanate therapy significantly modulates bacterial communities, increasing α-diversity, promoting recovery of commensal families (e.g., Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, Akkermansiaceae), and limiting the expansion of opportunistic taxa induced by antibiotics (Enterobacteriaceae, Enterococcaceae, Peptostreptococcaceae, Tannerellaceae) [63]. Consistent with these findings, a randomized controlled study in 49 healthy volunteers demonstrated that intake of S. boulardii attenuated antibiotic-induced microbiota alterations, restricted Escherichia overgrowth, and significantly reduced AAD, with adverse events reported in only 16.7% of subjects compared with 50% receiving antibiotics alone [64]. Similarly, in a prospective study using high-resolution molecular analysis in 60 women treated for bacterial vaginosis, concomitant or subsequent S. boulardii administration mitigated the one-log reduction in bacterial biomass and persistent diversity loss induced by ciprofloxacin plus metronidazole, preserving major bacterial groups, accelerating microbial recovery, and restoring individual microbiota profiles in ~88% of probiotic-treated subjects [65].

Building on this evidence of microbiota modulation and improved tolerability, the adjunctive role of S. boulardii CNCM I-745 has also been investigated in the setting of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy, particularly in light of the limitations associated with current regimens. Eradication of H. pylori relies on antibiotic-based triple or quadruple regimens; however, increasing antimicrobial resistance and frequent gastrointestinal adverse events are progressively compromising treatment effectiveness and tolerability [66,67,68,69]. In this regard, WGO Global Guidelines refer to the use of selected probiotic formulations, including S. boulardii, as adjunctive options during H. pylori eradication therapy to reduce gastrointestinal adverse events and improve treatment tolerability [51]. Within the context of AAD, the adjunctive use of S. boulardii CNCM I-745 during H. pylori eradication therapy has been investigated, particularly in light of the limitations of current regimens. Standard eradication relies on antibiotic-based triple or quadruple therapies; however, rising antimicrobial resistance and frequent gastrointestinal adverse events increasingly compromise both efficacy and tolerability [66,67,68,69].

In this setting, the WGO Global Guidelines highlight selected probiotic formulations, including S. boulardii, as adjunctive options to reduce gastrointestinal adverse events and enhance treatment tolerability [51]. Recent evidence supports the beneficial role of S. boulardii in H. pylori eradication. A meta-analysis of 19 randomized trials (5036 patients) showed an ~11% relative increase in eradication rates and a ~50% reduction in gastrointestinal adverse events, with diarrhoea risk lowered by ~60–65% [66]. Consistently, a randomized trial in 144 H. pylori-positive adults with non-ulcer dyspepsia found that adding S. boulardii CNCM I-745 to triple therapy improved eradication (75% vs. 65%) and reduced adverse events (18.7% vs. 45.8%), particularly diarrhoea, while bismuth-based quadruple therapy achieved 93% eradication [67]. Similarly, a prospective randomized open-label study in 199 adults reported that supplementation with S. boulardii CNCM I-745 during standard sequential therapy increased eradication by ~11%, reduced overall gastrointestinal adverse events by ~39% (including a ~44% reduction in AAD), and improved treatment adherence by ~4% [68]. Several complementary mechanisms may underlie the beneficial effects of S. boulardii CNCM I-745 during H. pylori eradication. Supplementation has been linked to a reduced abundance of antimicrobial resistance genes compared with standard triple therapy, suggesting a role in limiting antibiotic-driven selection and expansion of resistance determinants [69]. Moreover, S. boulardii appears to modulate host immune responses by lowering bacterial burden and gastric lymphoid follicle formation, enhancing mucosal IgA secretion and antimicrobial peptide production, and downregulating pro-inflammatory signalling pathways, thereby attenuating infection-associated mucosal inflammation [70]. Finally, its use has been associated with a more balanced gastric microbiota, characterized by modulation of anaerobic bacterial populations and enrichment of beneficial commensals, particularly Lactobacillus species [71].

Notably, S. boulardii CNCM I-745 is the only yeast strain included among the probiotic species currently recommended by international guidelines. In adults, clinical evidence supports the use of S. boulardii primarily for the prevention of AAD, with additional evidence for its role in diarrhoea caused by Clostridioides difficile infection and in the management of travellers’ diarrhoea. Typical therapeutic regimens involve administration of 250 mg twice daily, initiated on the first day of antibiotic therapy and continued throughout the course, occasionally extending for a few days thereafter [30,52,53].

5. Perspectives

This narrative review reflects the shared perspective of a multidisciplinary panel of experts, aiming to critically assess the current evidence on the use of S. boulardii in both paediatric and adult populations. S. boulardii is a unique probiotic yeast with well-documented antimicrobial, antitoxin, barrier-enhancing, and immunomodulatory properties. Traditionally, its use has been limited to the short-term management of acute diarrhoea, particularly in the context of gastroenteritis or antibiotic therapy. Nonetheless, the available evidence, combined with extensive real-world clinical use, indicates that S. boulardii is a safe and effective tool not only for short-term symptom management but also for the broader, long-term goal of restoring gut microbiota resilience in both children and adults. Diarrhoea should not be regarded merely as a transient symptom, but as a sentinel marker of gut dysbiosis. Its timely prevention and treatment are therefore essential, not only to relieve clinical discomfort but also to protect microbiota resilience and reduce the risk of long-term complications. In primary care, efforts should be directed towards preventing antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and supporting microbiota resilience through lifestyle, nutritional, and biological measures. In this context, timely administration, at the initiation of antibiotic treatment or within the first 48 h of an adequately dosed, clinically validated probiotic such as S. boulardii has been shown to prevent or reduce AAD and its underlying dysbiosis, thereby promoting a faster return to a resilient, pre-antibiotic state. Clinical evidence indicates that S. boulardii CNCM I-745, when administered as an adjunct to standard H. pylori eradication regimens, may lower the incidence of overall adverse reactions and diarrhoea. Such effects appear to enhance treatment tolerability and translate into improved patient-reported outcomes. In addition, to acute diarrhoeal episodes the most evident manifestation of gut dysbiosis, S. boulardii may also contribute to the relief of milder, chronic symptoms commonly associated with microbial imbalance, such as abdominal bloating, flatulence, irregular bowel habits, and a sense of incomplete digestion. These symptoms often reflect underlying dysbiosis and can significantly impair quality of life even in the absence of overt disease. Through its modulatory effects on microbial composition, intestinal permeability, and mucosal inflammation, S. boulardii supports the restoration of a balanced and functionally resilient gut ecosystem, thus addressing both the acute and chronic clinical consequences of dysbiosis. Therefore, beyond short-term interventions, S. boulardii may be employed in extended and cyclic regimens aimed at supporting long-term microbiota recovery.

In children, a daily dose of 250 mg is commonly used, whereas in adults 250 mg twice daily is recommended, typically for 10 days per month over a total period of 3–4 months. To optimise outcomes, probiotic therapy should be complemented by healthy dietary habits and regular physical activity. It should be acknowledged that the current body of evidence on S. boulardii has inherent limitations. Most available evidence on S. boulardii derives from trials assessing clinical outcomes such as antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and acute gastroenteritis, which are recognised markers of dysbiosis. However, relatively few studies have directly evaluated dysbiosis as a primary endpoint through microbiota analyses. In addition, the proposed cyclic dosing regimens are based on clinical practice and expert opinion rather than large randomized controlled trials. Finally, although S. boulardii is generally recognised as safe in both children and adults, rare cases of fungaemia have been reported in severely ill or immunocompromised patients, underscoring the importance of careful patient selection and risk assessment in these settings.

6. Conclusions

The gut microbiome, in both children and adults, plays a pivotal role in health and disease. It is shaped by internal factors such as genetics, immune function, and ageing, as well as external influences including diet, medications, and environmental exposures. When the balance of this ecosystem is disrupted—a state known as dysbiosis—the effects can extend beyond the digestive tract, influencing immunity, inflammation, and metabolism. Dysbiosis has also been linked to systemic consequences such as disrupted gut–brain communication, greater vulnerability to disorders of energy balance, and an increased risk of chronic inflammatory conditions. Although the strength of these associations varies across different conditions and causal links remain partly unclear, growing evidence highlights the importance of dysbiosis in the onset and progression of many diseases. This knowledge supports strategies that go beyond symptom control, aiming instead to restore microbiota composition and function. Diarrhoea, particularly when linked to antibiotic use, is often an early sign of microbiota disruption. Timely interventions, such as probiotic supplementation, can help prevent or reduce this complication.

Among available probiotics, Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 stands out for its unique biological properties and consistent evidence of safety and efficacy in both children and adults. It is well established in preventing and managing antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and has also shown promise as an adjunct to standard Helicobacter pylori eradication therapies. However, while Saccharomyces boulardii is encouraging, current data do not yet support its effectiveness across all dysbiosis-related conditions. More robust randomized controlled trials, with clinically relevant outcomes and longer follow-up, are needed to clarify its role in complex scenarios. Overall, an evidence-based use of Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 may be considered as part of broader strategies to strengthen microbiota resilience and promote gastrointestinal health in children and adults.

Author Contributions

All authors, G.P.N.; A.F.G.C.; L.G.; R.B.C. made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work and to the analysis and interpretation of published data; and drafted the work and revised it critically for important intellectual content; and approved the final version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring that any questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The review was supported by an independent grant from Zambon Italia Srl, dedicated to manuscript writing support and Open Access publication fees (25AD0127).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the editorial assistance provided by Momento Me-dico Srl, Italy.

Conflicts of Interest

In the last 5 years, Prof. Roberto Berni Canani carried out consultancy activities for Zambon, Milan, Italy; Prof. Arrigo Cicero has received grants for consultancy activities from Zentiva SA, Dompé SpA, Italfarmaco SpA, Sharper SpA, and Daiichi-Sankyo SpA; Prof. Gerardo Pio Nardone has served as a consultant for Allergosan and Alfasigma; Prof. Luca Gallelli declare no conflicts of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from Zambon Italia Srl. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAD | Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea |

| CFU | Colony-Forming Units |

| ESPGHAN | European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition |

| ESPID | European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases |

| FAO/WHO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Health Organization |

| H. pylori | Helicobacter pylori |

| PAGE | Pediatric Acute Gastroenteritis |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| S. boulardii | Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 |

| WGO | World Gastroenterology Organisation |

References

- Berg, G.; Rybakova, D.; Fischer, D.; Cernava, T.; Vergès, M.C.; Charles, T.; Chen, X.; Cocolin, L.; Eversole, K.; Corral, G.H.; et al. Microbiome definition re-visited: Old concepts and new challenges. Microbiome 2020, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sender, R.; Fuchs, S.; Milo, R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, H.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhong, W.; He, F.; Li, J. The mycobiome as integral part of the gut microbiome: Crucial role of symbiotic fungi in health and disease. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2440111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Origüela, V.; Lopez-Zaplana, A. Gut Microbiota: An Immersion in Dysbiosis, Associated Pathologies, and Probiotics. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gilbert, J.A.; Blaser, M.J.; Caporaso, J.G.; Jansson, J.K.; Lynch, S.V.; Knight, R. Current understanding of the human microbiome. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Safarchi, A.; Al-Qadami, G.; Tran, C.D.; Conlon, M. Understanding dysbiosis and resilience in the human gut microbiome: Biomarkers, interventions, and challenges. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1559521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, J.; Jain, S.; Nijkamp, J.F.; Sasidharan, R.; Agarwal, A.; Bird, J.K.; Spooren, A.; Wittwer Schegg, J.; Ver Loren van Themaat, E.; Mak, T.N. Gut health predictive indices linking gut microbiota dysbiosis with healthy state, mild gut discomfort, and inflammatory bowel disease phenotypes using gut microbiome profiling. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0027125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aguirre de Carcer, D. The human gut pan-microbiome presents a compositional core formed by discrete phylogenetic units. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrncir, T. Gut microbiota dysbiosis: Triggers, consequences, diagnostic and therapeutic options. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippot, L.; Griffiths, B.S.; Langenheder, S. Microbial community resilience across ecosystems and multiple disturbances. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2021, 85, e00026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Nair, G.B. Homeostasis and dysbiosis of the gut microbiome in health and disease. J. Biosci. 2019, 44, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, F.; Anderson, J.M.; Bharti, R.; Raes, J.; Rosenstiel, P. The resilience of the intestinal microbiota influences health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Alammar, N.; Singh, R.; Nanavati, J.; Song, Y.; Chaudhary, R.; Mullin, G.E. Gut microbial dysbiosis in the irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and metanalysis of case-control studies. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 120, 565–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, H. Role of gut Dysbiosis in liver diseases: What have we learned so far? Diseases 2019, 7, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, C.; Round, J.L. Defining dysbiosis and its influence on host immunity and disease. Cell Microbiol. 2014, 16, 1024–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Working Group on Drafting Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: London, ON, Canada; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flori, L.; Benedetti, G.; Martelli, A.; Calderone, V. Microbiota alterations associated with vascular diseases: Postbiotics as a next-generation magic bullet for gut-vascular axis. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 207, 107334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.K.; Guevarra, R.B.; Kim, Y.T.; Kwon, J.; Kim, H.; Cho, J.H.; Kim, H.B.; Lee, J.H. Role of Probiotics in Human Gut Microbiome-Associated Diseases. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 29, 1335–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waitzberg, D.; Guarner, F.; Hojsak, I.; Ianiro, G.; Polk, D.B.; Sokol, H. Can the Evidence-Based Use of Probiotics (Notably Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG) Mitigate the Clinical Effects of Antibiotic-Associated Dysbiosis? Adv. Ther. 2024, 41, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Warzée, J.P.; Elli, M.; Fall, A.; Cattivelli, D.; François, J.Y. Supranational Assessment of the Quality of Probiotics: Collaborative Initiative between Independent Accredited Testing Laboratories. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Taha, M.W.; Fenwick, D.J.C.; Marrs, E.C.L.; Chaudhry, A.S. Assessing Bacterial Viability and Label Accuracy in Human and Poultry Probiotics Sold in the United Kingdom. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mazzantini, D.; Calvigioni, M.; Celandroni, F.; Lupetti, A.; Ghelardi, E. Spotlight on the Compositional Quality of Probiotic Formulations Marketed Worldwide. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 693973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolaček, S.; Hojsak, I.; Berni Canani, R.; Guarino, A.; Indrio, F.; Orel, R.; Pot, B.; Shamir, R.; Szajewska, H.; Vandenplas, Y.; et al. Commercial Probiotic Products: A Call for Improved Quality Control. A Position Paper by the ESPGHAN Working Group for Probiotics and Prebiotics. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 65, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italian Ministry of Health. Directorate-General for Hygiene and Food Safety and Nutrition. Guidelines on Probiotics and Prebiotics; Italian Ministry of Health: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kelesidis, T.; Pothoulakis, C. Efficacy and safety of the probiotic Saccharomyces boulardii for the prevention and therapy of gastrointestinal disorders. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2012, 5, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gopalan, S.; Ganapathy, S.; Mitra, M.; Neha Kumar Joshi, D.; Veligandla, K.C.; Rathod, R.; Kotak, B.P. Unique Properties of Yeast Probiotic Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e46314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Berni Canani, R.; Cucchiara, S.; Cuomo, R.; Cuomo, R.; Pace, F.; Papale, F. Saccharomyces boulardii: A summary of the evidence for gastroenterology clinical practice in adults and children. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2011, 15, 809–822. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neut, C.; Mahieux, S.; Dubreuil, L.J. Antibiotic susceptibility of probiotic strains: Is it reasonable to combine probiotics with antibiotics? Médecine Et Mal. Infect. 2017, 47, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFarland, L.V. Systematic review, and meta-analysis of Saccharomyces boulardii in adult patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 2202–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Terciolo, C.; Dapoigny, M.; Andre, F. Beneficial effects of Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 on clinical disorders associated with intestinal barrier disruption. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2019, 12, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Czerucka, D.; Rampal, P. Diversity of Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 mechanisms of action against intestinal infections. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 2188–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gasparrini, A.J.; Wang, B.; Sun, X.; Kennedy, E.A.; Hernandez-Leyva, A.; Ndao, I.M.; Tarr, P.I.; Warner, B.B.; Dantas, G. Persistent metagenomic signatures of early-life hospitalization and antibiotic treatment in the infant gut microbiota and resistome. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 2285–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Planer, J.D.; Peng, Y.; Kau, A.L.; Blanton, L.V.; Ndao, I.M.; Tarr, P.I.; Warner, B.B.; Gordon, J.I. Development of the gut microbiota and mucosal IgA responses in twins and gnotobiotic mice. Nature 2016, 534, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baym, M.; Kryazhimskiy, S.; Lieberman, T.D.; Chung, H.; Desai, M.M.; Kishony, R. Inexpensive multiplexed library preparation for megabase-sized genomes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128036, Erratum in PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131262. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0131262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Suárez-Martínez, C.; Santaella-Pascual, M.; Yagüe-Guirao, G.; Martínez-Graciá, C. Infant gut microbiota colonization: Influence of prenatal and postnatal factors, focusing on diet. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1236254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toubon, G.; Butel, M.J.; Rozé, J.C.; Nicolis, I.; Delannoy, J.; Zaros, C.; Ancel, P.Y.; Aires, J.; Charles, M.A. Early Life Factors Influencing Children Gut Microbiota at 3.5 Years from Two French Birth Cohorts. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bankole, T.; Li, Y. The early-life gut microbiome in common pediatric diseases: Roles and therapeutic implications. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1597206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, R.S. The Microbiome, Antibiotics, and Health of the Pediatric Population. EC Microbiol. 2016, 3, 388–390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Morreale, C.; Giaroni, C.; Baj, A.; Folgori, L.; Barcellini, L.; Dhami, A.; Agosti, M.; Bresesti, I. Effects of Perinatal Antibiotic Exposure and Neonatal Gut Microbiota. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Prescott, S.; Dreisbach, C.; Baumgartel, K.; Koerner, R.; Gyamfi, A.; Canellas, M.; St Fleur, A.; Henderson, W.A.; Trinchieri, G. Impact of Intrapartum Antibiotic Prophylaxis on Offspring Microbiota. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 754013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aloisio, I.; Quagliariello, A.; De Fanti, S.; Luiselli, D.; De Filippo, C.; Albanese, D.; Corvaglia, L.T.; Faldella, G.; Di Gioia, D. Evaluation of the effects of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis on newborn intestinal microbiota using a sequencing approach targeted to multi hypervariable 16S rDNA regions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 5537–5546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stearns, J.C.; Simioni, J.; Gunn, E.; McDonald, H.; Holloway, A.C.; Thabane, L.; Mousseau, A.; Schertzer, J.D.; Ratcliffe, E.M.; Rossi, L.; et al. Intrapartum antibiotics for GBS prophylaxis alter colonization patterns in the early infant gut microbiome of low-risk infants. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yan, T.; Goldman, R.D. Probiotics for antibiotic- associated diarrhea in children. Can. Fam. Physician 2020, 66, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central]

- Korpela, K.; Salonen, A.; Virta, L.J.; Kekkonen, R.A.; Forslund, K.; Bork, P.; de Vos, W.M. Intestinal microbiome is related to lifetime antibiotic use in Finnish pre-school children. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, A.M.C.; Salazar, D.d.J.R.; Stefanolo, J.P.; Serrano, M.C.C.; Casas, I.C.; Peña, J.R.Z. Intestinal Dysbiosis: Exploring Definition, Associated Symptoms, and Perspectives for a Comprehensive Understanding—A Scoping Review. Probiot. Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, 17, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gray, C.; Dulong, C.; Argaez, C. Probiotics for Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea in Pediatrics: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness and Guidelines; Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Selvamani, S.; Kapoor, N.; Ajmera, A.; El Enshasy, H.A.; Dailin, D.J.; Sukmawati, D.; Abomoelak, M.; Nurjayadi, M.; Abomoelak, B. Prebiotics in New-Born and Children’s Health. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Miqdady, M.; Al Mistarihi, J.; Azaz, A.; Rawat, D. Prebiotics in the infant microbiome: The past, present, and future. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2020, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szajewska, H.; Berni Canani, R.; Domellöf, M.; Guarino, A.; Hojsak, I.; Indrio, F.; Lo Vecchio, A.; Mihatsch, W.A.; Mosca, A.; Orel, R.; et al. Probiotics for the Management of Pediatric Gastrointestinal Disorders: Position Paper of the ESPGHAN Special Interest Group on Gut Microbiota and Modifications. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2023, 76, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarner, F.; Sanders, M.E.; Szajewska, H.; Cohen, H.; Eliakim, R.; Herrera-deGuise, C.; Karakan, T.; Merenstein, D.; Piscoya, A.; Ramakrishna, B.; et al. World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines: Probiotics and Prebiotics. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2024, 58, 533–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szajewska, H.; Kołodziej, M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in children and adults. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 42, 1149–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinleyici, E.C.; Kara, A.; Ozen, M.; Vandenplas, Y. Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 in different clinical conditions. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2014, 14, 1593–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abidi, A. Prophylactic role of saccharomyces boulardii in prevention of antibiotic associated diarrhoea in children in indian population. Nov. Sci. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 03–04, 346–350. [Google Scholar]

- Storr, M.; Stengel, A. Klinische Evidenz zu Probiotika in der Prävention einer Antibiotika-assoziierten Diarrhö: Systematischer Review [Systematic review: Clinical evidence of probiotics in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea]. MMW-Fortschritte Der Med. 2021, 163, 19–26, (German). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padayachee, M.; Visser, J.; Viljoen, E.; Musekiwa, A.; Blaauw, R. Efficacy, and safety of Saccharomyces boulardii in the treatment of acute gastroenteritis in the paediatric population: A systematic review: A systematic review. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 32, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Li, J.; Xu, X.; Xia, C.; Pan, Y. Effectiveness and Safety of Saccharomyces Boulardii for the Treatment of Acute Gastroenteritis in the Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review and Meta- Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 2022, 6234858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yatsunenko, T.; Rey, F.E.; Manary, M.J.; Trehan, I.; Dominguez-Bello, M.G.; Contreras, M.; Magris, M.; Hidalgo, G.; Baldassano, R.N.; Anokhin, A.P.; et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature 2012, 486, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fan, Y.; Pedersen, O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, T.S.; Shanahan, F.; O’Toole, P.W. The gut microbiome as a modulator of healthy ageing. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lynch, S.V.; Pedersen, O. The Human Intestinal Microbiome in Health and Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2369–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilg, H.; Adolph, T.E.; Gerner, R.R.; Moschen, A.R. The Intestinal Microbiota in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 954–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spatz, M.; Wang, Y.; Lapiere, A.; Da Costa, G.; Michaudel, C.; Danne, C.; Michel, M.L.; Langella, P.; Sokol, H.; Richard, M.L. Saccharomyces bou-lardii CNCM I-745 supplementation during and after antibiotic treatment positively influences the bacterial gut microbiota. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1087715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kabbani, T.A.; Pallav, K.; Dowd, S.E.; Villafuerte-Galvez, J.; Vanga, R.R.; Castillo, N.E.; Hansen, J.; Dennis, M.; Leffler, D.A.; Kelly, C.P. Prospective randomized controlled study on the effects of Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 and amoxicillin-clavulanate or the combination on the gut microbiota of healthy volunteers. Gut Microbes 2017, 8, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Swidsinski, A.; Loening-Baucke, V.; Schulz, S.; Manowsky, J.; Verstraelen, H.; Swidsinski, S. Functional anatomy of the colonic bioreactor: Impact of antibiotics and Saccharomyces boulardii on bacterial composition in human fecal cylinders. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 39, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Xie, Y. Efficacy and safety of Saccharomyces boulardii as an adjuvant therapy for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori: A meta-analysis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1441185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, B.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Du, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z. Saccharomyces boulardii combined with triple therapy alter the microbiota in the eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Seddik, H.; Boutallaka, H.; Elkoti, I.; Nejjari, F.; Berraida, R.; Berrag, S.; Loubaris, K.; Sentissi, S.; Benkirane, A. Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 plus sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori infections: A randomized, open-label trial. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 75, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cifuentes, S.G.; Prado, M.B.; Fornasini, M.; Cohen, H.; Baldeón, M.E.; Cárdenas, P.A. Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 supplementation modifies the fecal resistome during Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Helicobacter 2022, 27, e12870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Tian, Z.B.; Yu, Y.N.; Zhang, C.P.; Li, X.Y.; Mao, T.; Jing, X.; Zhao, W.J.; Ding, X.L.; Yang, R.M.; et al. Saccharomyces boulardii administration can inhibit the formation of gastric lymphoid follicles induced by Helicobacter suis infection. Pathog. Dis. 2017, 75, ftx006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keikha, M.; Kamali, H. The impact of Saccharomyces boulardii adjuvant supplementation on alternation of gut microbiota after Helicobacter pylori eradication: A metagenomics analysis. Gene Rep. 2022, 26, 101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.