The Effect of Apple and Pear Cultivars on In Vitro Fermentation with Human Faecal Microbiota

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fruit

2.2. In Vitro Digestion and Fermentation

2.3. Organic Acid Analysis

2.4. Microbiota Analysis

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. pH Changes After In Vitro Human Faecal Fermentation

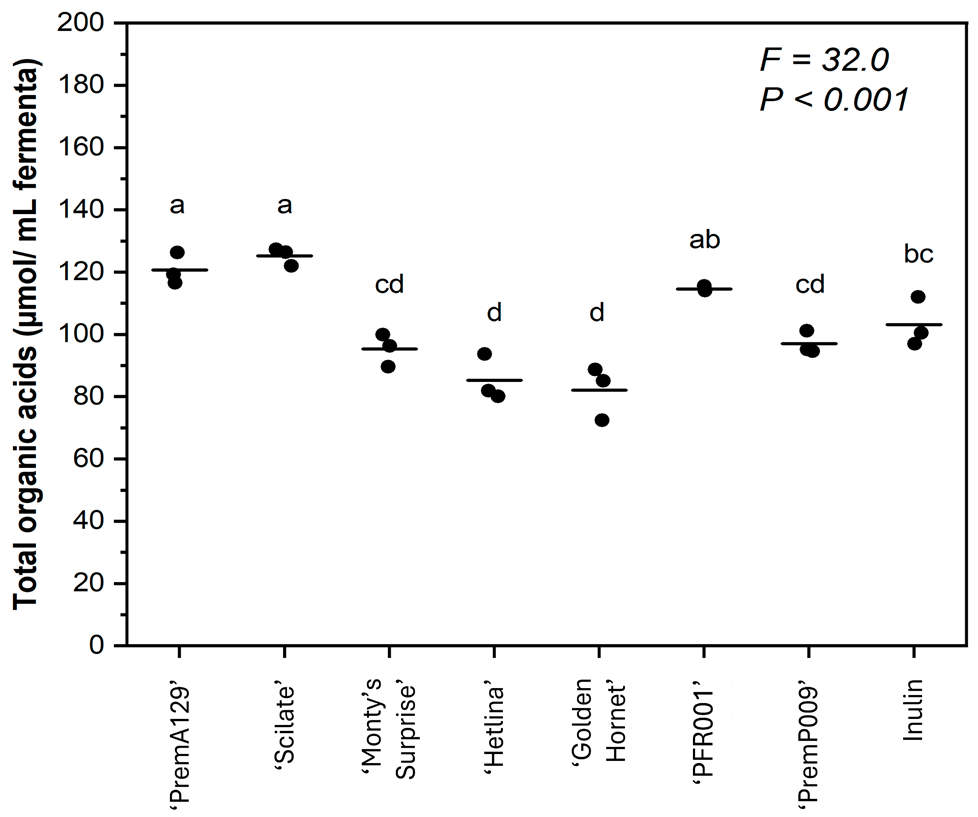

3.2. Production of Organic Acids During In Vitro Faecal Fermentation

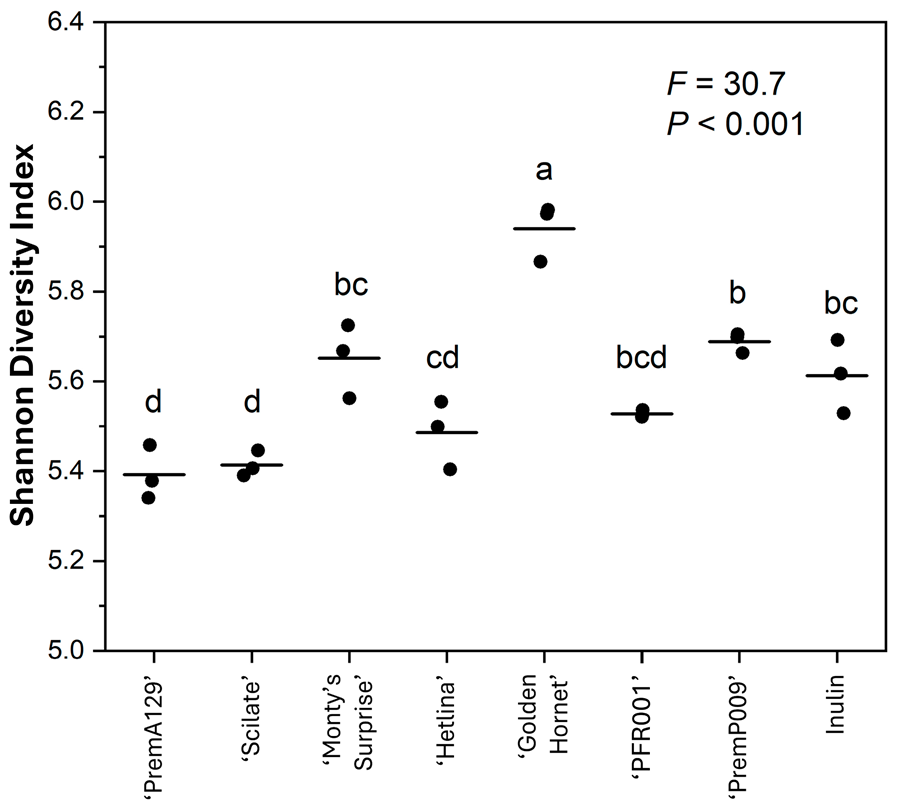

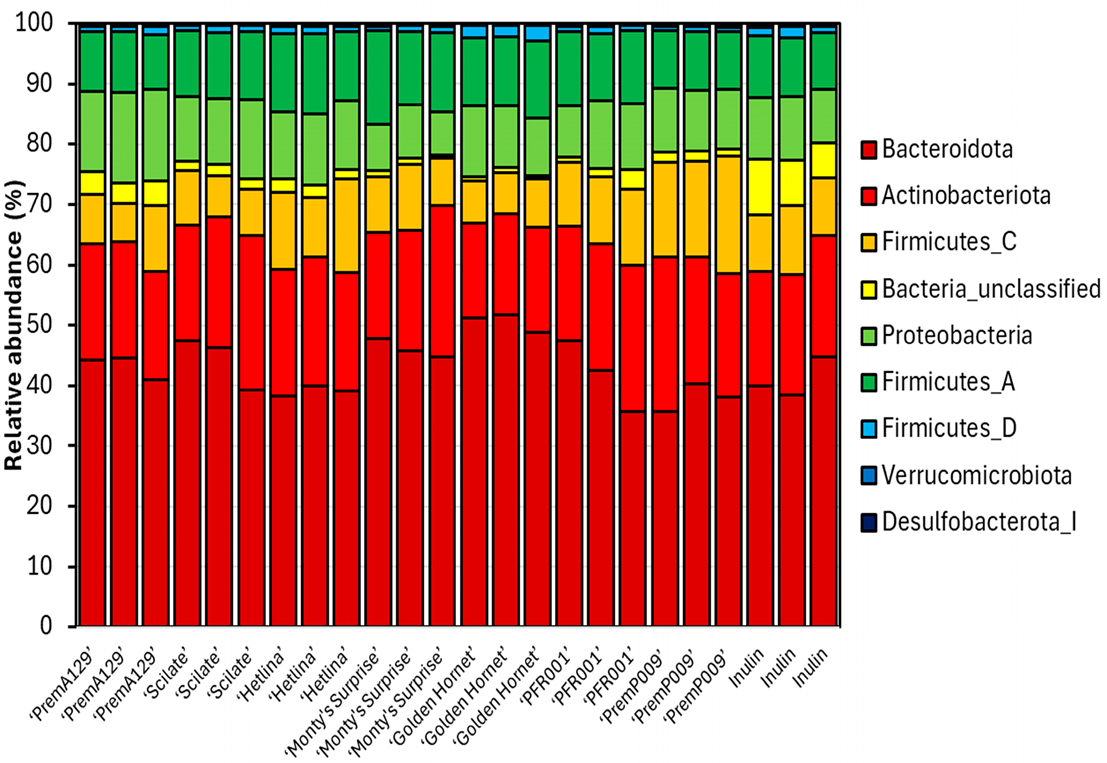

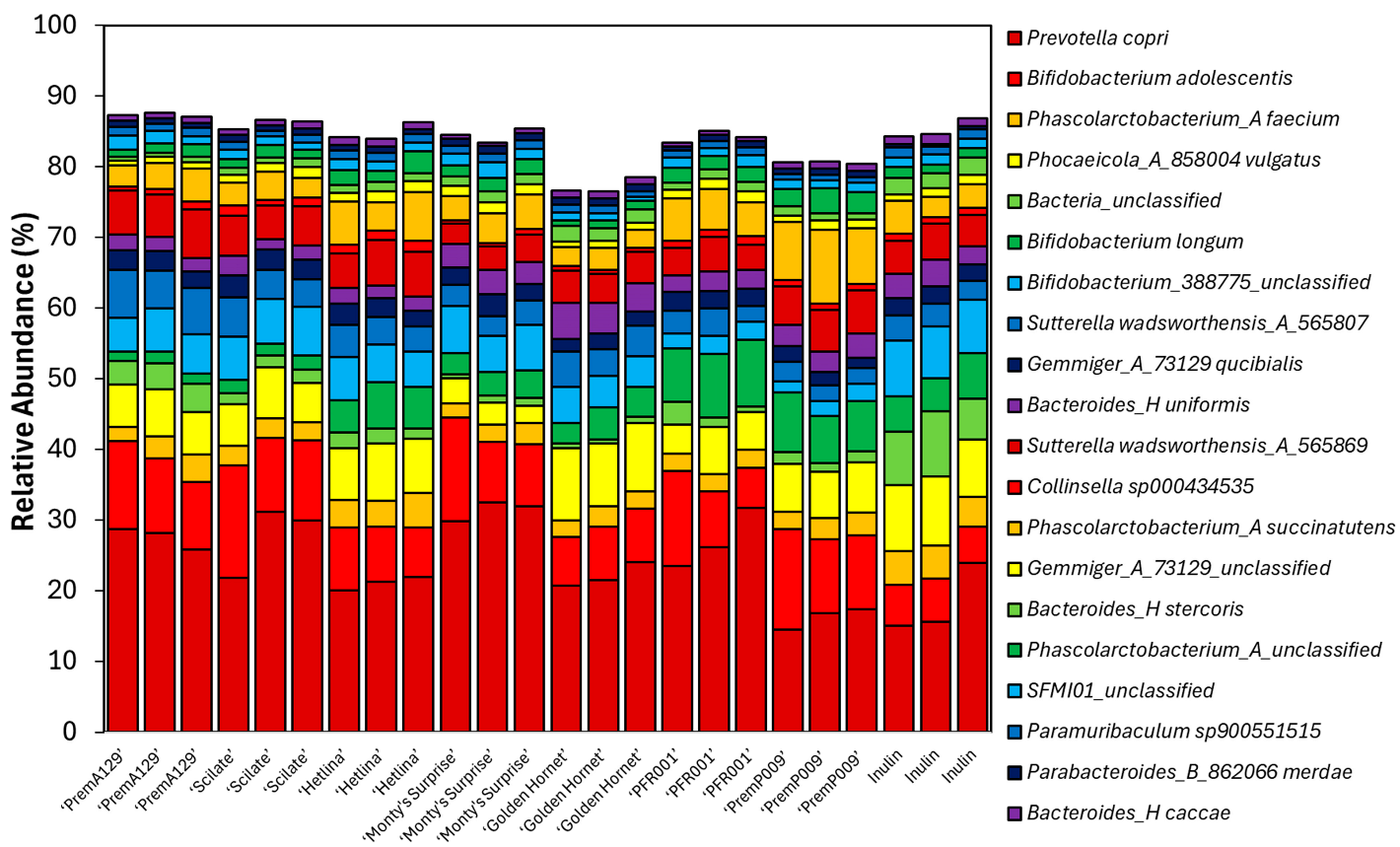

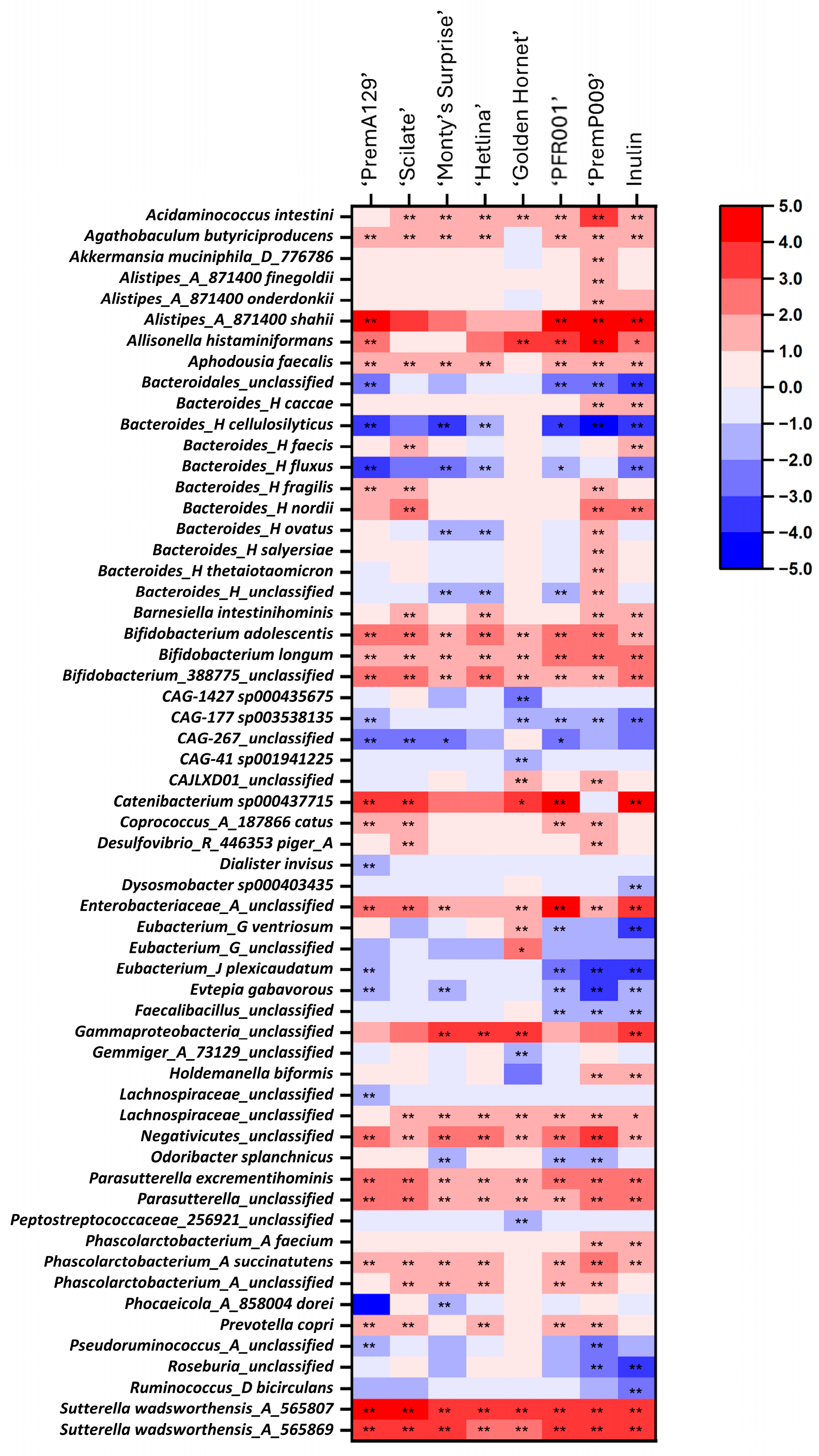

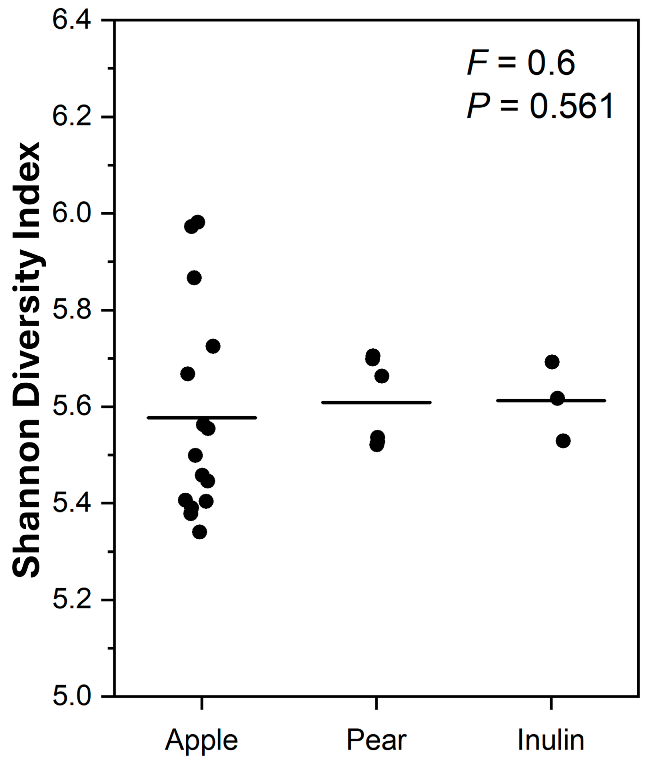

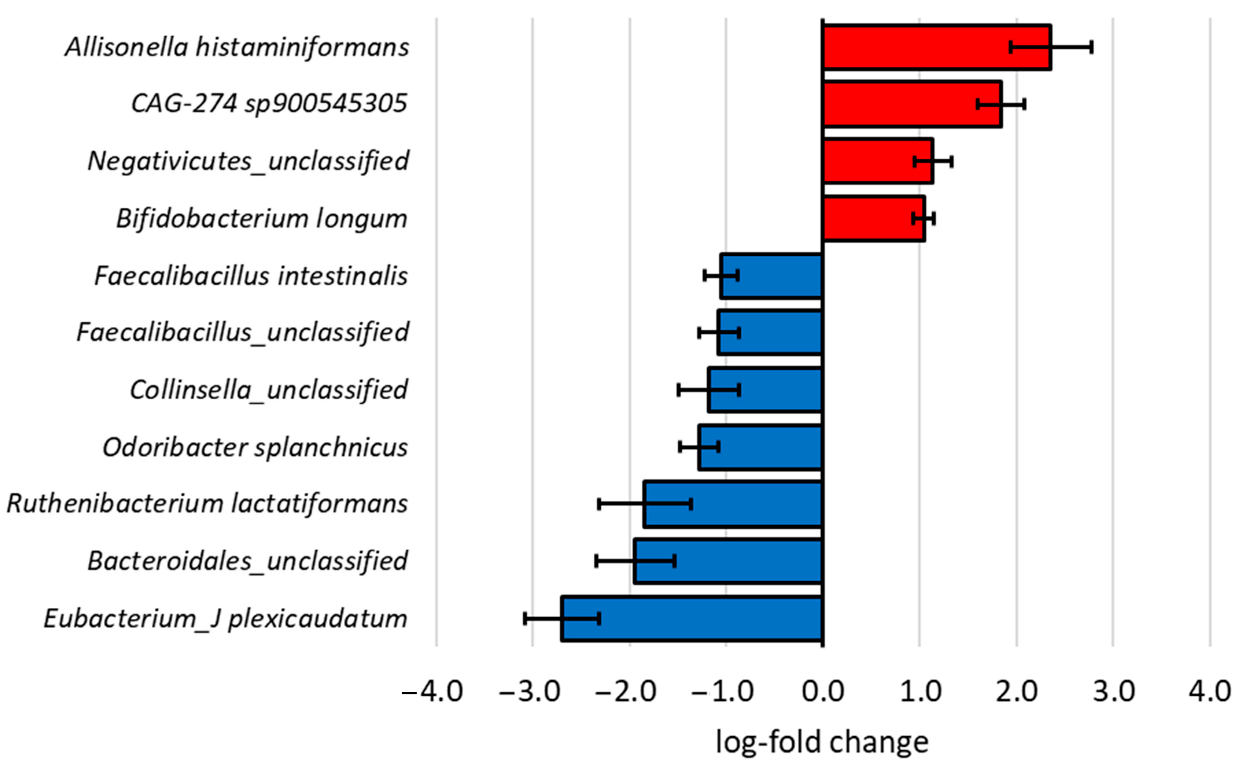

3.3. Microbial Composition After In Vitro Faecal Fermentation

4. Discussion

4.1. The Effect of Apple and Pear Substrates on Fermentation Outcomes After In Vitro Human Faecal Fermentation

4.2. Changes in Microbial Composition During In Vitro Faecal Fermentation Influenced by Apple and Pear Substrates

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arts, I.C.W.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Harnack, L.J.; Gross, M.; Folsom, A.R. Dietary catechins in relation to coronary heart disease death among postmenopausal women. Epidemiology 2001, 12, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Manson, J.E.; Buring, J.E.; Sesso, H.D.; Liu, S. Associations of dietary flavonoids with risk of type 2 diabetes, and markers of insulin resistance and systemic inflammation in women: A prospective study and cross-sectional analysis. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2005, 24, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mink, P.J.; Scrafford, C.G.; Barraj, L.M.; Harnack, L.; Hong, C.P.; Nettleton, J.A.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr. Flavonoid intake and cardiovascular disease mortality: A prospective study in postmenopausal women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayer, B.A.; Avendano, E.E.; Edelson, E.; Nirmala, N.; Johnson, E.J.; Raman, G. Effects of Intake of Apples, Pears, or Their Products on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors and Clinical Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, nzz109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição de Oliveira, M.; Sichieri, R.; Sanchez Moura, A. Weight Loss Associated with a Daily Intake of Three Apples or Three Pears Among Overweight Women. Nutrition 2003, 19, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravn-Haren, G.; Dragsted, L.O.; Buch-Andersen, T.; Jensen, E.N.; Jensen, R.I.; Németh-Balogh, M.; Paulovicsová, B.; Bergström, A.; Wilcks, A.; Licht, T.R.; et al. Intake of whole apples or clear apple juice has contrasting effects on plasma lipids in healthy volunteers. Eur. J. Nutr. 2013, 52, 1875–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espley, R.V.; Butts, C.A.; Laing, W.A.; Martell, S.; Smith, H.; McGhie, T.K.; Zhang, J.; Paturi, G.; Hedderley, D.; Bovy, A.; et al. Dietary Flavonoids from Modified Apple Reduce Inflammation Markers and Modulate Gut Microbiota in Mice1, 2, 3. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumaran, S.; Huffman, L.; Sivakumaran, S. The New Zealand Food Composition Database: A useful tool for assessing New Zealanders’ nutrient intake. Food Chem. 2018, 238, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutsos, A.; Tuohy, K.M.; Lovegrove, J.A. Apples and Cardiovascular Health-Is the Gut Microbiota a Core Consideration? Nutrients 2015, 7, 3959–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic-Malinovska, R.; Kuzmanova, S.; Winkelhausen, E. Oligosaccharide Profile in Fruits and Vegetables as Sources of Prebiotics and Functional Foods. Int. J. Food Prop. 2014, 17, 949–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.K.; Rossi, M.; Bajka, B.; Whelan, K. Dietary fibre in gastrointestinal health and disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinson, J.A.; Su, X.; Zubik, L.; Bose, P. Phenol Antioxidant Quantity and Quality in Foods: Fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 5315–5321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kschonsek, J.; Wolfram, T.; Stöckl, A.; Böhm, V. Polyphenolic Compounds Analysis of Old and New Apple Cultivars and Contribution of Polyphenolic Profile to the In Vitro Antioxidant Capacity. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, S.; Anthony, B.; Boscolo Sesillo, F.; Masia, A.; Musacchi, S. Determination of Post-Harvest Biochemical Composition, Enzymatic Activities, and Oxidative Browning in 14 Apple Cultivars. Foods 2021, 10, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazzocco, S.; Mattila, I.; Guyot, S.; Renard, C.M.G.C.; Aura, A.-M. Factors affecting the conversion of apple polyphenols to phenolic acids and fruit matrix to short-chain fatty acids by human faecal microbiota in vitro. Eur. J. Nutr. 2008, 47, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escarpa, A.; González, M.C. Evaluation of high-performance liquid chromatography for determination of phenolic compounds in pear horticultural cultivars. Chromatographia 2000, 51, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz, R.K.; McGhie, T.K. Genetic Variability in Apple Fruit Polyphenol Composition in Malus × domestica and Malus sieversii Germplasm Grown in New Zealand. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 11509–11521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGhie, T.K.; Hunt, M.; Barnett, L.E. Cultivar and Growing Region Determine the Antioxidant Polyphenolic Concentration and Composition of Apples Grown in New Zealand. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 3065–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mditshwa, A.; Crouch, E.; Opara, U.L.; Vries, F.; Merwe, K.V.d. Antioxidant content and phytochemical properties of apple ‘Granny Smith’ at different harvest times. S. Afr. J. Plant Soil 2015, 32, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, A.; Macià, A.; Romero, M.-P.; Valls, J.; Bladé, C.; Arola, L.; Motilva, M.-J. Bioavailability of procyanidin dimers and trimers and matrix food effects in in vitro and in vivo models. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olthof, M.R.; Hollman, P.C.; Katan, M.B. Chlorogenic acid and caffeic acid are absorbed in humans. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertog, M.G.; Hollman, P.C.; Katan, M.B.; Kromhout, D. Intake of potentially anticarcinogenic flavonoids and their determinants in adults in The Netherlands. Nutr. Cancer 1993, 20, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, L.; Rimm, E.; Hollman, P.C.; de Vries, J.H.; Katan, M.B. Flavonol and flavone intakes in US health professionals. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, 1414–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Dhital, S.; Wu, P.; Chen, X.-D.; Gidley, M. In vitro digestion of apple tissue using a dynamic stomach model: Grinding and crushing effects on polyphenol bioaccessibiity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenore, G.C.; Campiglia, P.; Stiuso, P.; Ritieni, A.; Novellino, E. Nutraceutical potential of polyphenolic fractions from Annurca apple (M. pumila Miller cv Annurca). Food Chem. 2013, 140, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkar, S.G.; Rosendale, D.; Paturi, G.; Herath, T.D.; Stoklosinski, H.; Phipps, J.E.; Hedderley, D.; Ansell, J. In vitro utilization of gold and green kiwifruit oligosaccharides by human gut microbial populations. Plant Food Hum. Nutr. 2012, 67, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkar, S.G.; Simmons, L.; Herath, T.D.; Phipps, J.E.; Trower, T.M.; Hedderley, D.I.; McGhie, T.K.; Blatchford, P.; Ansell, J.; Sutton, K.H.; et al. Evaluation of the prebiotic potential of five kiwifruit cultivars after simulated gastrointestinal digestion and fermentation with human faecal bacteria. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatchford, P.; Stoklosinski, H.; Walton, G.; Swann, J.; Gibson, G.; Gearry, R.; Ansell, J. Kiwifruit fermentation drives positive gut microbial and metabolic changes irrespective of initial microbiota composition. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre 2015, 6, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monro, J.A.; Mishra, S.; Venn, B. Baselines representing blood glucose clearance improve in vitro prediction of the glycaemic impact of customarily consumed food quantities. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roediger, W.E. Role of anaerobic bacteria in the metabolic welfare of the colonic mucosa in man. Gut 1980, 21, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.C.; Waby, J.S.; Chirakkal, H.; Staton, C.A.; Corfe, B.M. Butyrate suppresses expression of neuropilin I in colorectal cell lines through inhibition of Sp1 transactivation. Mol. Cancer 2010, 9, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepelska, M.; Cultrone, A.; Béguet-Crespel, F.; Le Roux, K.; Doré, J.; Arulampalam, V.; Blottière, H.M. Butyrate Produced by Commensal Bacteria Potentiates Phorbol Esters Induced AP-1 Response in Human Intestinal Epithelial Cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezbedová, L.; Heyes, J.; Ahmed Nasef, N.; Mehta, S. Phytochemicals from Monty’s Surprise apple are absorbed in humans, increase plasma antioxidant response, and inhibit lung and breast cancer proliferation in vitro. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2024, 83, E47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesschaeve, I.; Noble, A.C. Polyphenols: Factors influencing their sensory properties and their effects on food and beverage preferences2. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 330S–335S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, S.; Kohl, S.; Thalmann, S.; Mateus, N.; Meyerhof, W.; De Freitas, V. Different phenolic compounds activate distinct human bitter taste receptors. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 1525–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condezo-Hoyos, L.; Mohanty, I.P.; Noratto, G.D. Assessing non-digestible compounds in apple cultivars and their potential as modulators of obese faecal microbiota in vitro. Food Chem. 2014, 161, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutsos, A.; Lima, M.; Conterno, L.; Gasperotti, M.; Bianchi, M.; Fava, F.; Vrhovsek, U.; Lovegrove, J.A.; Tuohy, K.M. Effects of Commercial Apple Varieties on Human Gut Microbiota Composition and Metabolic Output Using an In Vitro Colonic Model. Nutrients 2017, 9, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Luo, H.; Keung, W.; Chan, Y.; Chan, K.; Xiao, X.; Li, F.; Lyu, A.; Dong, C.; Xu, J. Impact of pectin structural diversity on gut microbiota: A mechanistic exploration through in vitro fermentation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 355, 123367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; de Vos, P. Structure-function effects of different pectin chemistries and its impact on the gastrointestinal immune barrier system. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 65, 1201–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinck, J.E.; Sinha, A.K.; Laursen, M.F.; Dragsted, L.O.; Raes, J.; Uribe, R.V.; Walter, J.; Roager, H.M.; Licht, T.R. Intestinal pH: A major driver of human gut microbiota composition and metabolism. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.-H.; Lin, S.-Y.; Chen, L.-L.; Ouyang, K.-H.; Wang, W.-J. The Interaction between Flavonoids and Intestinal Microbes: A Review. Foods 2023, 12, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, S.-J.; Kim, G.; Lim, M.Y.; Song, E.-J.; Jung, D.-H.; Kum, J.-S.; Nam, Y.-D.; Park, C.-S.; Seo, D.-H. The influence of in vitro pectin fermentation on the human fecal microbiome. AMB Express 2018, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J.R.; Curtis, J. An ordination of the upland forest communities of southern Wisconsin. Ecol. Monogr. 1957, 27, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozupone, C.A.; Knight, R. UniFrac: A new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 8228–8235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Mao, K.; Gao, J.; Chitrakar, B.; Sadiq, F.A.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Xu, C.; Sang, Y. Pear pomace soluble dietary fiber ameliorates the negative effects of high-fat diet in mice by regulating the gut microbiota and associated metabolites. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1025511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.M.; Munoz-Munoz, J.; van Sinderen, D. Plant Glycan Metabolism by Bifidobacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 609418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumas-Bilak, E.; Carlier, J.-P.; Jean-Pierre, H.; Mory, F.; Teyssier, C.; Gay, B.; Campos, J.; Marchandin, H. Acidaminococcus intestini sp. nov., isolated from human clinical samples. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 2314–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, F.; Ren, X.; Du, B.; Niu, K.; Yu, Z.-Q.; Yang, Y.-D. Insoluble dietary fiber of pear fruit pomace (Pyrus ussuriensis Maxim) consumption ameliorates alterations of the obesity-related features and gut microbiota caused by high-fat diet. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 99, 105354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, M.R.; Flint, J.F.; Russell, J.B. Allisonella histaminiformans gen. nov., sp. nov.: A Novel Bacterium that Produces Histamine, Utilizes Histidine as its Sole Energy Source, and Could Play a Role in Bovine and Equine Laminitis. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2002, 25, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorani, M.; Del Vecchio, L.E.; Dargenio, P.; Kaitsas, F.; Rozera, T.; Porcari, S.; Gasbarrini, A.; Cammarota, G.; Ianiro, G. Histamine-producing bacteria and their role in gastrointestinal disorders. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 17, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuri, J.A.; Neira, A.; Quilodran, A.; Motomura, Y.; Palomo, I. Antioxidant activity and total phenolics concentration in apple peel and flesh is determined by cultivar and agroclimatic growing regions in Chile. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2009, 7, 513–517. [Google Scholar]

- Bouayed, J.; Deußer, H.; Hoffmann, L.; Bohn, T. Bioaccessible and dialysable polyphenols in selected apple varieties following in vitro digestion vs. their native patterns. Food Chem. 2012, 131, 1466–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkar, S.G.; Trower, T.M.; Stevenson, D.E. Fecal microbial metabolism of polyphenols and its effects on human gut microbiota. Anaerobe 2013, 23, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cultivars | Type of Pip Fruit | Total Polyphenol (μg g−1 Whole Fruit) 1 |

|---|---|---|

| PremA129 | apple | 574 |

| Scilate | apple | 587 |

| Monty’s Surprise | apple | 772 |

| Hetlina | apple | 1336 |

| Golden Hornet | apple | 3152 |

| PFR001 | pear | NA |

| PremP009 | pear | 303 |

| Organic Acid | Substrate | p Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘PremA129’ | ‘Scilate’ | ‘Monty’s Surprise’ | ‘Hetlina’ | ‘Golden Hornet’ | ‘PFR001’ | ‘PremP009’ | INULIN | ||

| µmol/mL fermenta | |||||||||

| Formic | 0.30 ± 0.00 d | ND | 1.27 ± 0.09 bc | 1.64 ± 0.06 b | 0.99 ± 0.01 c | 1.67 ± 0.09 b | 2.79 ± 0.21 a | 2.32 ± 0.04 a | <0.001 |

| Acetic | 64.8 ± 1.15 a | 67.5 ± 0.52 a | 41.9 ± 0.88 d | 48.7 ± 1.29 c | 40.4 ± 1.13 d | 57.9 ± 0.92 b | 47.6 ± 0.85 c | 51.3 ± 1.03 c | <0.001 |

| Butyric | 1.70 ± 0.10 e | 2.03 ± 0.08 de | 1.87 ± 0.08 e | 2.82 ± 0.17 cd | 3.96 ± 0.17 ab | 3.41 ± 0.28 bc | 4.68 ± 0.35 a | 2.76 ± 0.08 cd | <0.001 |

| Propionic | 4.66 ± 0.26 c | 3.24 ± 0.16 c | 4.30 ± 0.35 c | 6.31 ± 0.48 b | 3.90 ± 0.12 c | 7.86 ± 0.28 ab | 8.96 ± 0.56 a | 6.75 ± 0.20 b | <0.001 |

| Lactic | 44.1 ± 1.65 ab | 46.7 ± 1.21 a | 33.8 ± 2.97 bc | 33.4 ± 1.35 bc | 29.4 ± 3.83 c | 38.3 ± 0.94 abc | 32.5 ± 0.55 bc | 39.8 ± 4.60 abc | <0.001 |

| Succinic | 5.04 ± 0.15 a | 5.43 ± 0.13 a | 2.11 ± 0.10 c | 2.47 ± 0.25 c | 3.68 ± 0.21 b | 2.75 ± 0.083 b | 0.45 ± 0.04 d | 0.91 ± 0.12 d | <0.001 |

| Organic Acid | Substrate | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apple | Pear | Inulin | ||

| µmol/mL fermenta | ||||

| N | 15 | 6 | 3 | |

| Total 2 | 102 ± 1.48 | 106 ± 2.34 | 103 ± 3.31 | 0.360 |

| Formic acid | 0.90 ± 0.05 b | 2.23 ± 0.07 a | 2.32 ± 0.12 a | <0.001 |

| Acetic acid | 52.7 ± 0.45 | 52.7 ± 0.71 | 51.3 ± 1.00 | 0.437 |

| Butyric acid | 2.47 ± 0.08 b | 4.05 ± 0.13 a | 2.76 ± 0.19 b | <0.001 |

| Propionic acid | 4.48 ± 0.15 c | 8.41 ± 0.24 a | 6.75 ± 0.30 b | <0.001 |

| Lactic acid | 37.5 ± 1.14 | 35.4 ± 1.80 | 39.8 ± 2.55 | 0.360 |

| Succinic acid | 3.75 ± 0.07 a | 1.60 ± 0.14 b | 0.91 ± 0.16 c | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoogeveen, A.M.E.; Butts, C.A.; Kim, C.C.; Jobsis, C.M.H.; Parkar, S.G.; Stoklosinski, H.M.; Sutton, K.H.; Davis, P.; Hedderley, D.I.; Johnston, J.; et al. The Effect of Apple and Pear Cultivars on In Vitro Fermentation with Human Faecal Microbiota. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13081870

Hoogeveen AME, Butts CA, Kim CC, Jobsis CMH, Parkar SG, Stoklosinski HM, Sutton KH, Davis P, Hedderley DI, Johnston J, et al. The Effect of Apple and Pear Cultivars on In Vitro Fermentation with Human Faecal Microbiota. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(8):1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13081870

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoogeveen, Anna M. E., Christine A. Butts, Caroline C. Kim, Carel M. H. Jobsis, Shanthi G. Parkar, Halina M. Stoklosinski, Kevin H. Sutton, Patricia Davis, Duncan I. Hedderley, Jason Johnston, and et al. 2025. "The Effect of Apple and Pear Cultivars on In Vitro Fermentation with Human Faecal Microbiota" Microorganisms 13, no. 8: 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13081870

APA StyleHoogeveen, A. M. E., Butts, C. A., Kim, C. C., Jobsis, C. M. H., Parkar, S. G., Stoklosinski, H. M., Sutton, K. H., Davis, P., Hedderley, D. I., Johnston, J., & Gopal, P. K. (2025). The Effect of Apple and Pear Cultivars on In Vitro Fermentation with Human Faecal Microbiota. Microorganisms, 13(8), 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13081870