Seasonal Shifts from Water Depth to Nitrate Reorganize Protistan Communities Following Lake Freeze–Thaw Events

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

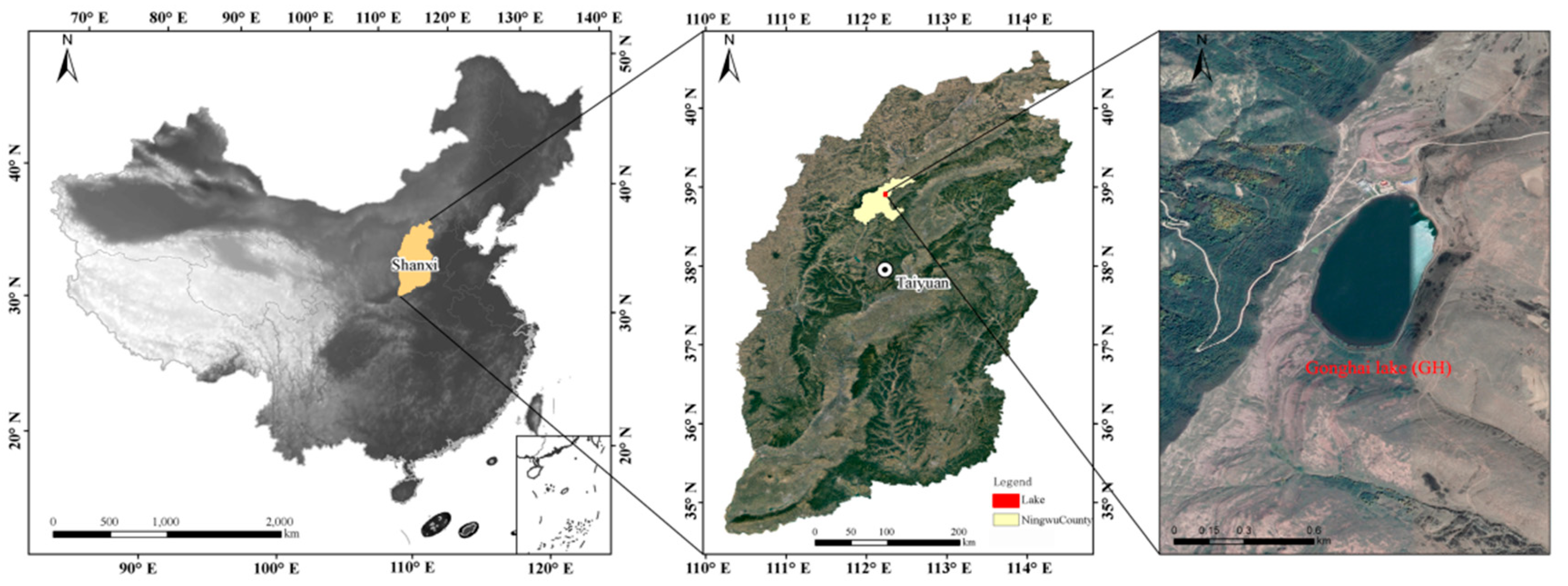

2.1. Site Description and Sampling

2.2. Physicochemical Analysis

2.3. DNA Extractions, PCR Amplification, and High-Throughput Sequencing

2.4. Nucleic Acid Sequences

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Shifts in the Vertical Stratification of Lake Water Physicochemistry Between Ice-Covered and Ice-Free Periods

3.2. Changes in Protistan Community Composition Across Seasonal Freeze–Thaw Cycles and Lake Depths

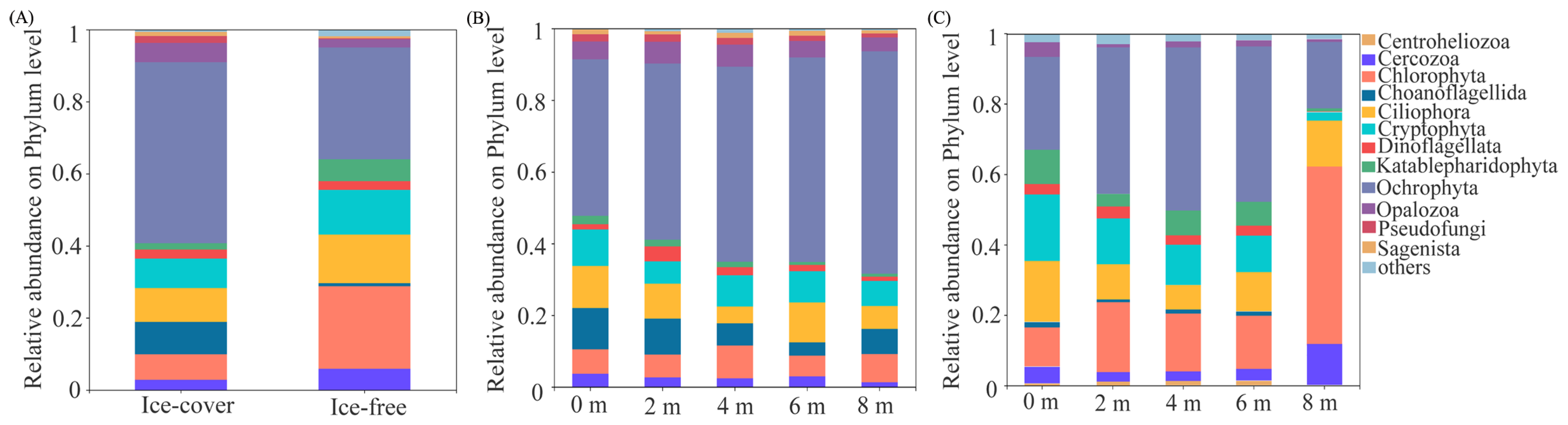

3.2.1. Protistan Community Composition Across Seasonal Freeze–Thaw

3.2.2. Protistan Community Composition Across Different Depths

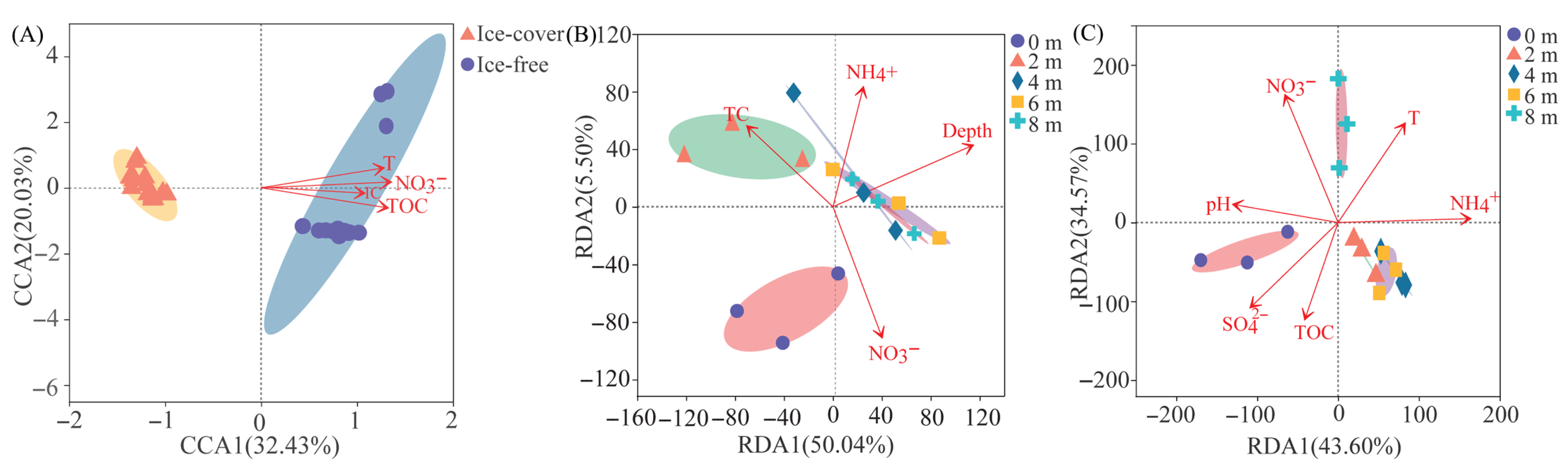

3.2.3. Relationship Between Dominant Taxa and Environmental Factors

3.3. Dynamics and Drivers of the Protistan Community Diversity Across Seasons and Depths

4. Discussion

4.1. Seasonal Shift: From Physically Driven to Resource-Driven Community Assembly

4.2. Mechanistic Links Between Environmental Filters and Taxonomic Succession

4.3. Evaluating the Role of Depth and Vertical Gradients

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grosbois, G.; Rautio, M. Active and colorful life under lake ice. Ecology 2018, 99, 752–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebert, M.P.; Beisner, B.E.; Rautio, M.; Fussmann, G.F. Warming winters in lakes: Later ice onset promotes consumer overwintering and shapes springtime planktonic food webs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2114840118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, C.M.; Sharma, S.; Gray, D.K.; Hampton, S.E.; Read, J.S.; Rowley, R.J.; Schneider, P.; Lenters, J.D.; McIntyre, P.B.; Kraemer, B.M.; et al. Rapid and highly variable warming of lake surface waters around the globe. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 10773–10781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, A.G.G.; Tomasino, M.P.; Duarte, P.; Fernández-Méndez, M.; Assmy, P.; Ribeiro, H.; Surkont, J.; Leite, R.B.; Pereira-Leal, J.B.; Torgo, L.; et al. Diversity and composition of pelagic prokaryotic and protist communities in a thin Arctic sea-ice regime. Microb. Ecol. 2019, 78, 388–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doting, E.L.; Jensen, M.B.; Peter, E.K.; Ellegaard-Jensen, L.; Tranter, M.; Benning, L.G.; Hansen, M.; Anesio, A.M. The exometabolome of microbial communities inhabiting bare ice surfaces on the southern Greenland Ice Sheet. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 26, e16574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertilsson, S.; Burgin, A.; Carey, C.C.; Fey, S.B.; Grossart, H.; Grubisic, L.M.; Jones, I.D.; Kirillin, G.; Lennon, J.T.; Shade, A.; et al. The under-ice microbiome of seasonally frozen lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2013, 58, 1998–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, F.; Liang, H.; Gao, D. Mediative mechanism of freezing/thawing on greenhouse gas emissions in an inland Saline-Alkaline wetland: A metagenomic analysis. Microb. Ecol. 2022, 86, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepernick, B.N.; Chase, E.E.; Denison, E.R.; Gilbert, N.E.; Truchon, A.R.; Frenken, T.; Cody, W.R.; Martin, R.M.; Chaffin, J.D.; Bullerjahn, G.S.; et al. Declines in ice cover are accompanied by light limitation responses and community change in freshwater diatoms. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrad015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard-Varona, C.; Roux, S.; Bowen, B.P.; Silva, L.P.; Lau, R.; Schwenck, S.M.; Schwartz, S.; Woyke, T.; Northen, T.; Sullivan, M.B.; et al. Protist impacts on marine cyanovirocell metabolism. ISME Commun. 2022, 2, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Tao, C.; Jousset, A.; Xiong, W.; Wang, Z.; Shen, Z.; Wang, B.; Xu, Z.; Gao, Z.; Liu, S.; et al. Trophic interactions between predatory protists and pathogen-suppressive bacteria impact plant health. ISME J. 2022, 16, 1932–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capo, E.; Rydberg, J.; Tolu, J.; Domaizon, I.; Debroas, D.; Bindler, R.; Bigler, C. How does environmental inter-annual variability shape aquatic microbial communities? A 40-year annual record of sedimentary DNA from a boreal lake (Nylandssjön, Sweden). Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Xu, Q.H.; Chen, F.H. Origin of the upland lake group in Ningwu Tianchi Region, Shanxi Province. J. Lanzhou Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2014, 50, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunthorn, M.; Klier, J.; Bunge, J.; Stoeck, T. Comparing the hyper-variable V4 and V9 regions of the small subunit rDNA for assessment of ciliate environmental diversity. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2012, 59, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoeck, T.; Bass, D.; Nebel, M.; Christen, R.; Jones, M.D.M.; Breiner, H.; Richards, T.A. Multiple marker parallel tag environmental DNA sequencing reveals a highly complex eukaryotic community in marine anoxic water. Mol. Ecol. 2010, 19, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillou, L.; Bachar, D.; Audic, S.; Bass, D.; Berney, C.; Bittner, L.; Boutte, C.; Burgaud, G.; de Vargas, C.; Decelle, J.; et al. The Protist Ribosomal Reference database (PR2): A catalog of unicellular eukaryote Small Sub-Unit rRNA sequences with curated taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukheloua, R.; Mukherjee, I.; Park, H.; Simek, K.; Kasalicky, V.; Ngochera, M.; Grossart, H.-P.; Picazo-Mozo, A.; Camacho, A.; Cabello-Yeves, P.J.; et al. Global freshwater distribution of Telonemia protists. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamy, M.; Ramond, P.; Bass, D.; Del, C.J.; Dunthorn, M.; Lara, E.; Mitra, A.; Vaulot, D.; Santoferrara, L. Towards a trait-based framework for protist ecology and evolution. Trends Microbiol. 2025, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmaso, N. Long-term phytoplankton community changes in a deep subalpine lake: Responses to nutrient availability and climatic fluctuations. Freshw. Biol. 2010, 55, 825–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghane, A.; Boegman, L. Vertical mixing, light penetration and phosphorus cycling regulate seasonal algae blooms in an ice-covered dimictic lake. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2025, 13, e2024JG008258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Yan, X.; Xu, J.; Su, X.; Li, L. Lipidomic profiling and discovery of lipid biomarkers in Stephanodiscus sp. under cold stress. Metabolomics 2013, 9, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Bai, L.; Yao, Z.; Li, W.; Yang, W. Seasonal lake ice cover drives the restructuring of bacteria-archaea and bacteria-fungi interdomain ecological networks across diverse habitats. Environ. Res. 2025, 269, 120907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, T.M.; Wilhelm, A.; Dwyer, A.C.; Webb, P.N.; Baldwin, A.L.; Techtmann, S.M. Microbial community dynamics during lake ice freezing. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, S.M.; Nielson, J.R.; Mayne, S.R.; Goldberg, C.S.; Manning, J.A. Transport and mixing observed in a pond: Description of wind-forced transport processes and quantification of mixing rates. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2024, 69, 2180–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.J.; Dieser, M.; McKnight, D.M.; SanClements, M.D.; Foreman, C.M. Relationship between dissolved organic matter quality and microbial community composition across polar glacial environments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2018, 94, fiy090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajarajan, A.; Cerbin, S.; Beng, K.C.; Monaghan, M.T.; Wolinska, J. Warming increases richness and shapes assemblages of eukaryotic parasitic plankton. Environ. Microbiome 2025, 20, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammill, E.; Dart, R. Contributions of mean temperature and temperature variation to population stability and community diversity. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e8665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Jiang, H.; Liu, W.; Huang, L.; Huang, J.; Wang, B.; Dong, H.; Chu, R.K.; Tolic, N. Potential utilization of terrestrially derived dissolved organic matter by aquatic microbial communities in saline lakes. ISME J. 2020, 14, 2313–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellogg, C.T.E.; McClelland, J.W.; Dunton, K.H.; Crump, B.C. Strong seasonality in arctic estuarine microbial food webs. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillin, G.; Leppäranta, M.; Terzhevik, A.; Granin, N.; Bernhardt, J.; Engelhardt, C.; Efremova, T.; Golosov, S.; Palshin, N.; Sherstyankin, P.; et al. Physics of seasonally ice-covered lakes: A review. Aquat. Sci. 2012, 74, 659–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, N.B.; Lacelle, D.; Faucher, B.; Cotroneo, S.; Jasperse, L.; Clark, I.D.; Andersen, D.T. Sources of solutes and carbon cycling in perennially ice-covered Lake Untersee, Antarctica. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere, E.; Baulch, H.M. Winter nitrification in ice-covered lakes. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e224864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.I.; Siddorn, J.R.; Blackford, J.C.; Gilbert, F.J. Turbulence as a control on the microbial loop in a temperate seasonally stratified marine systems model. J. Sea Res. 2004, 52, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashaway, A.R.; Carrick, H.J. Effects of light, temperature and habitat quality on meroplanktonic diatom rejuvenation in Lake Erie: Implications for seasonal hypoxia. J. Plankton Res. 2010, 32, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Liu, G.; Xiong, Z.; Cao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Song, C. Dissolved organic nitrogen and phosphorus derived from different cyanobacteria regulate distinctly different nitrate reduction pathways in sediments. Water Res. 2025, 287, 124520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Princiotta, S.D.; VanKuren, A.; Williamson, C.E.; Sanders, R.W.; Valinas, M.S. Disentangling the role of light and nutrient limitation on bacterivory by mixotrophic nanoflagellates. J. Phycol. 2023, 59, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohore, O.E.; Ifon, B.E.; Wang, Y.; Kazmi, S.; Zhang, J.; Sanganyado, E.; Jiao, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, Z. Vertical changes in water depth and environmental variables drove the antibiotics and antibiotic resistomes distribution, and microbial food web structures in the estuary and marine ecosystems. Environ. Int. 2023, 178, 108118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaim, G.; Andreis, D.; Piccolroaz, S.; Obertegger, U. Ice cover and extreme events determine dissolved oxygen in a placid mountain lake. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2020WR027321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, V.W.; Suter, M.J.F.; Narwani, A. Light and nutrients modulate the temperature-sensitivity of growth in phytoplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 2025, 10, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garstecki, T.; Verhoeven, R.; Wickham, S.A.; Arndt, H. Benthic-pelagic coupling: A comparison of the community structure of benthic and planktonic heterotrophic protists in shallow inlets of the southern Baltic. Freshw. Biol. 2000, 45, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta-Maraver, I.; Galloway, J.; Posselt, M.; Arnon, S.; Reiss, J.; Lewandowski, J.; Robertson, A.L. Environmental filtering and community delineation in the streambed ecotone. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Ice-Covered | Ice-Free |

|---|---|---|

| T (°C) | 3.60 ± 0.74 b | 6.17 ± 1.26 a |

| pH | 7.94 ± 0.05 b | 8.69 ± 0.10 a |

| DO (mg·L−1) | 8.90 ± 0.96 b | 11.23 ± 0.75 a |

| EC (μS·cm−1) | 963.27 ± 14.15 a | 826.13 ± 18.97 b |

| NO3− (mg·L−1) | 0.01 ± 0.01 b | 0.03 ± 0.01 a |

| NO2− (mg·L−1) | 0.02 ± 0.01 b | 0.03 ± 0.02 a |

| NH4+ (mg·L−1) | 4.21 ± 0.18 a | 0.11 ± 0.06 b |

| TC (mg·L−1) | 119.53 ± 1.92 b | 131.62 ± 1.09 a |

| TOC (mg·L−1) | 18.94 ± 2.31 b | 29.14 ± 1.34 a |

| IC (mg·L−1) | 100.60 ± 1.56 b | 102.47 ± 0.66 a |

| SO42− (mg·L−1) | 19.72 ± 5.08 a | 20.23 ± 2.55 a |

| PO43− (mg·L−1) | 0.45 ± 0.38 a | 0.25 ± 0.16 a |

| Between Two Periods | Ice-Covered Period | Ice-Free Period | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | CCA1 | CCA2 | R2 | p | Factors | RDA1 | RDA2 | R2 | p | Factors | RDA1 | RDA2 | R2 | p |

| TOC | 0.951 | −0.309 | 0.897 | 0.001 | Depth | 0.816 | 0.578 | 0.699 | 0.001 | NO3− | −0.3771 | 0.926 | 0.738 | 0.002 |

| T | 0.955 | 0.297 | 0.831 | 0.001 | NO3− | 0.153 | −0.988 | 0.449 | 0.035 | NH4+ | 0.999 | 0.042 | 0.674 | 0.002 |

| NO3− | 0.997 | 0.076 | 0.821 | 0.001 | NH4+ | 0.337 | 0.942 | 0.439 | 0.040 | SO42− | −0.7195 | −0.694 | 0.584 | 0.004 |

| IC | 0.998 | −0.058 | 0.518 | 0.002 | TC | −0.668 | 0.745 | 0.289 | 0.045 | T | 0.566 | 0.824 | 0.561 | 0.007 |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | pH | −0.9878 | 0.156 | 0.429 | 0.033 |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | TOC | −0.3361 | −0.942 | 0.408 | 0.038 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, Y.; Luo, Z.; Liu, J. Seasonal Shifts from Water Depth to Nitrate Reorganize Protistan Communities Following Lake Freeze–Thaw Events. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2869. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122869

Zhou Y, Luo Z, Liu J. Seasonal Shifts from Water Depth to Nitrate Reorganize Protistan Communities Following Lake Freeze–Thaw Events. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2869. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122869

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Yanying, Zhengming Luo, and Jinxian Liu. 2025. "Seasonal Shifts from Water Depth to Nitrate Reorganize Protistan Communities Following Lake Freeze–Thaw Events" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2869. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122869

APA StyleZhou, Y., Luo, Z., & Liu, J. (2025). Seasonal Shifts from Water Depth to Nitrate Reorganize Protistan Communities Following Lake Freeze–Thaw Events. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2869. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122869