Generation of a Human–Mouse Chimeric Anti-Japanese Encephalitis Virus and Zika Virus Monoclonal Antibody Using CDR Grafting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines, Viruses, and Animals

2.2. Expression and Purification of Viral Proteins

2.3. Designment of a Human–Mouse Chimeric mAb

2.4. Expression and Purification of Recombinant mAbs

2.5. Direct ELISA

2.6. Immunofluorescence Assay (IFA)

2.7. Plaque-Reduction Neutralization Test (PRNT)

2.8. Mouse Experiments

2.9. Viral Load Detection

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

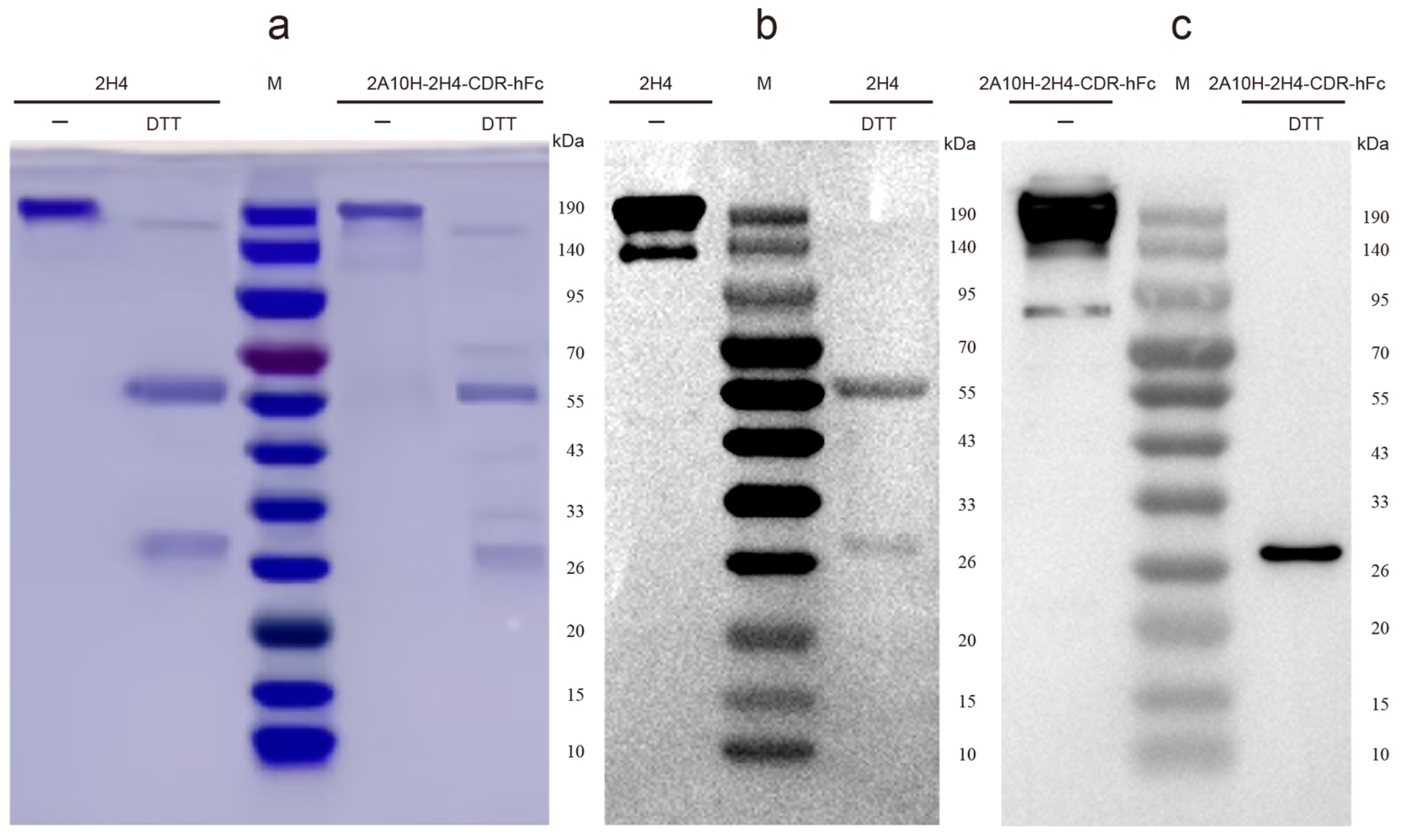

3.1. Construction of Human–Mouse Chimeric mAb 2A10-2H4-CDR-hFc via CDR Grafting

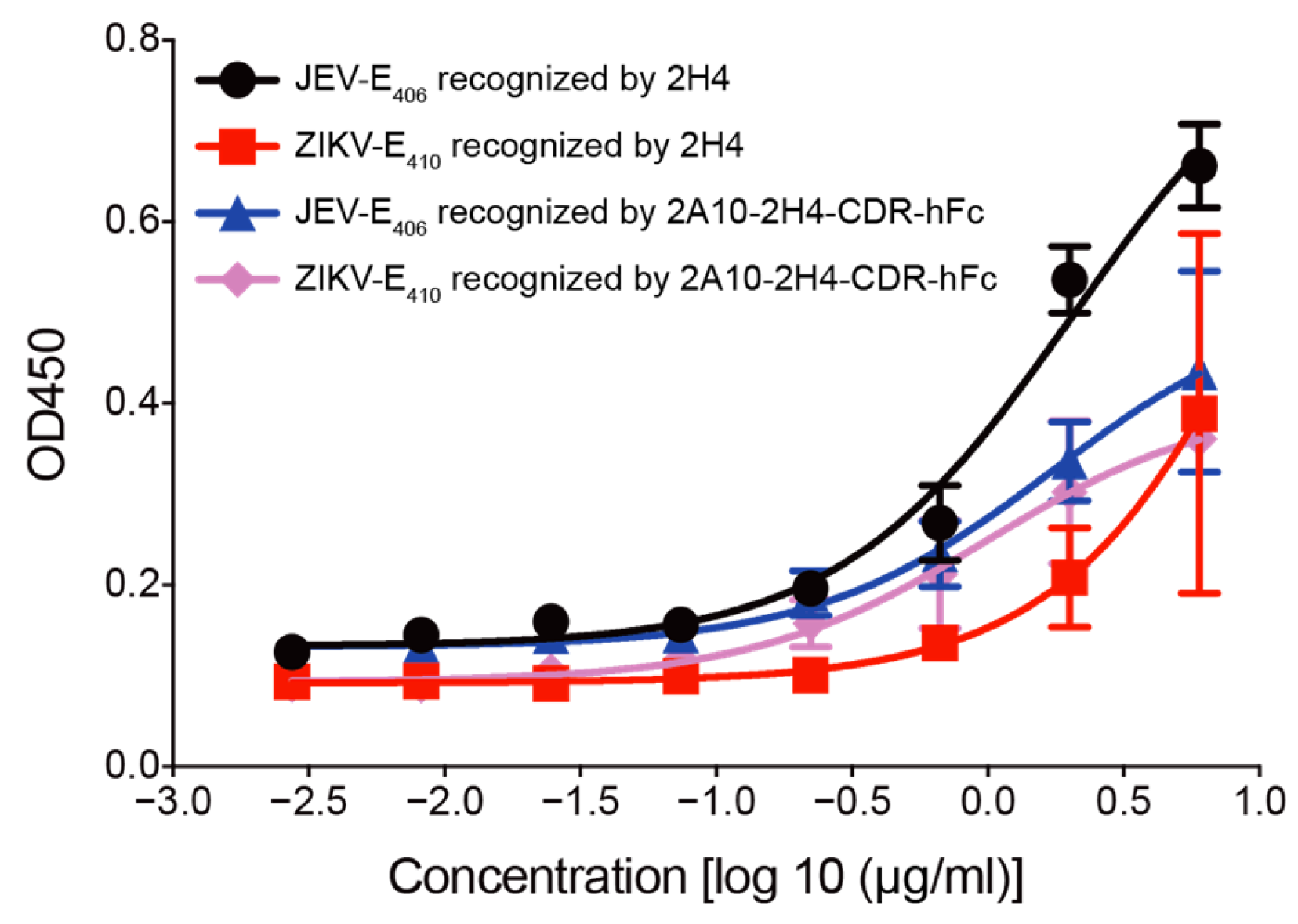

3.2. Human–Mouse Chimeric mAb 2A10-2H4-CDR-hFc Recognizes E Proteins of JEV and ZIKV

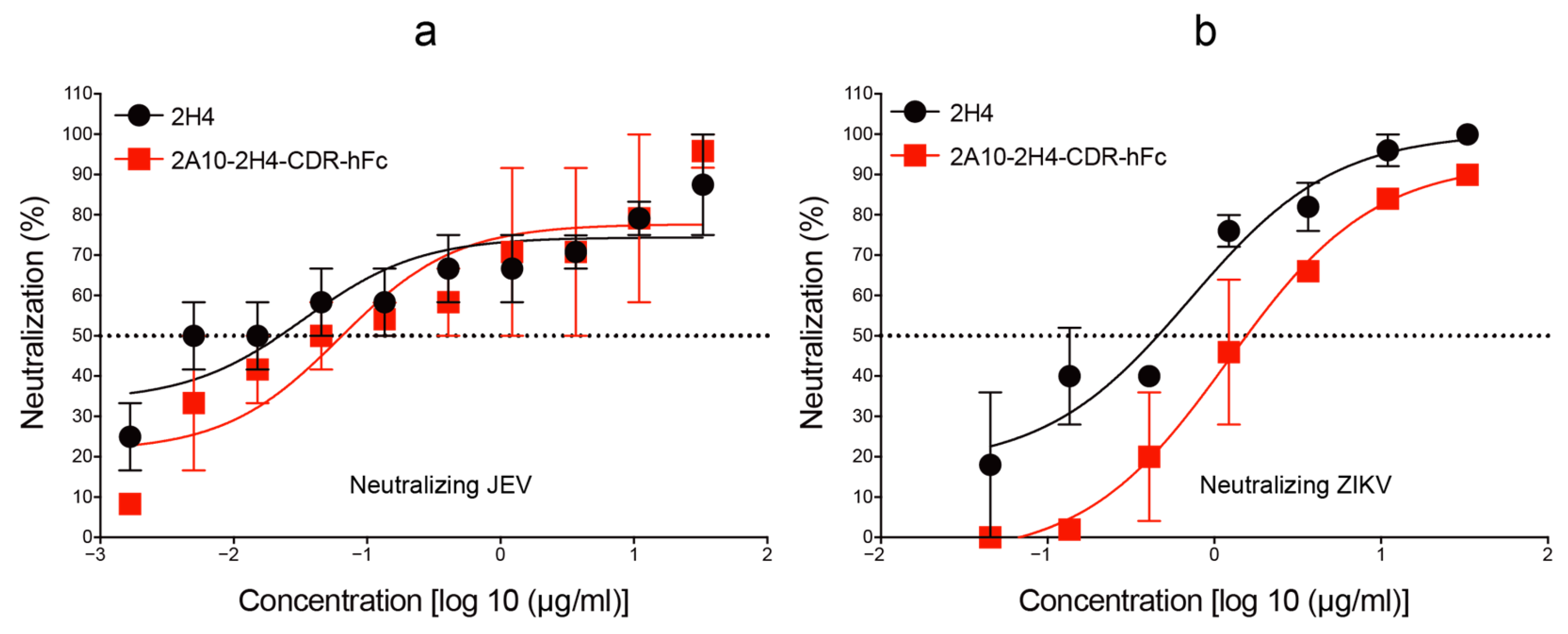

3.3. Human–Mouse Chimeric mAb 2A10-2H4-CDR-hFc Efficiently Neutralizes JEV and ZIKV Infections In Vitro

3.4. A Single Injection of Recombinant 2A10-2H4-CDR-hFc mAb Remarkably Decreases the Mortality of Mice Challenged by JEV or ZIKV

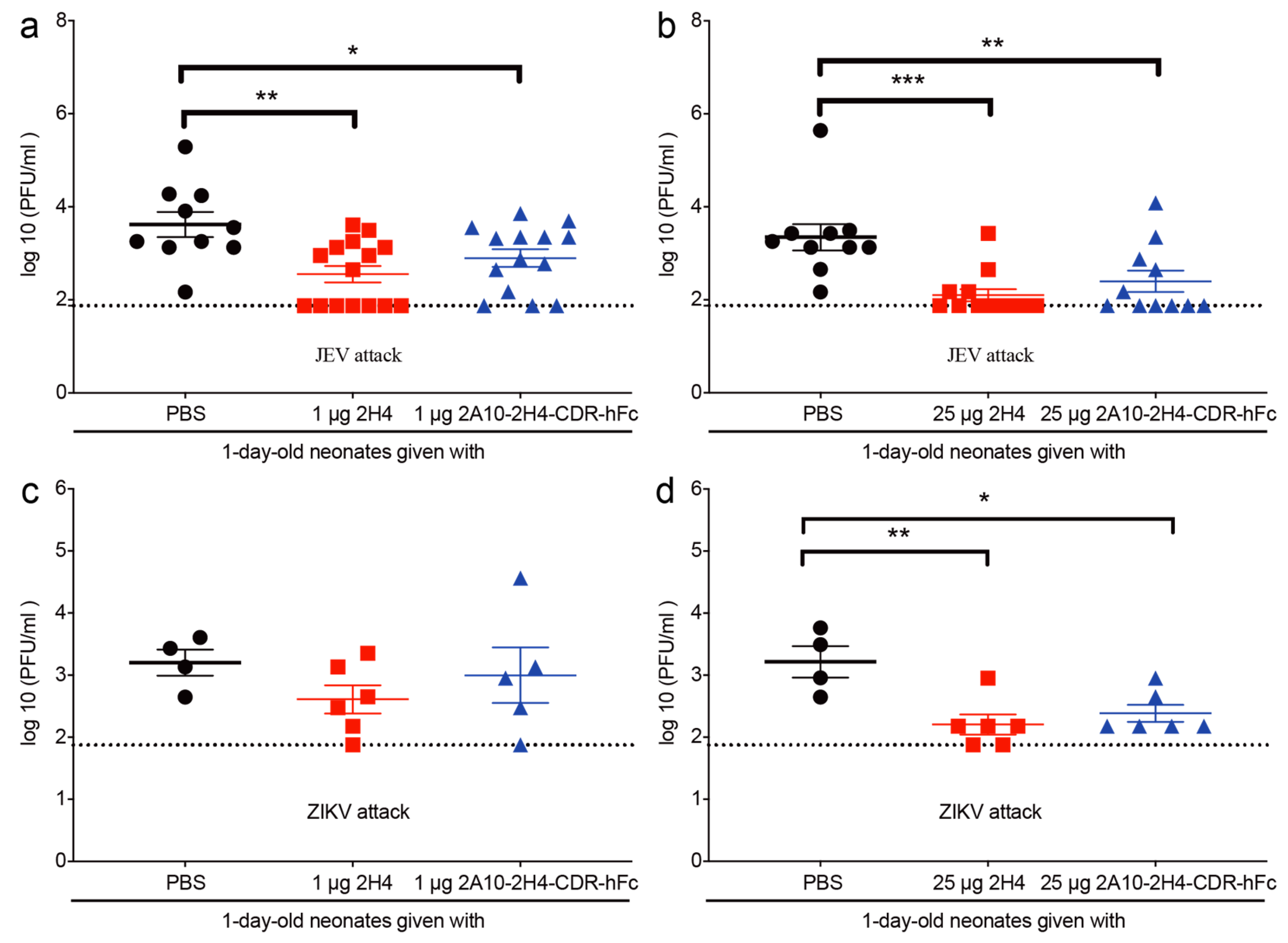

3.5. Application of 2A10-2H4-CDR-hFc mAb Significantly Reduces the Serum Viral Load of Virus-Infected Neonatal Mice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease C. Prevention: Japanese encephalitis surveillance and immunization—Asia and the Western Pacific, 2012. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2013, 62, 658–662. [Google Scholar]

- Lackritz, E.M.; Ng, L.C.; Marques, E.T.A.; Rabe, I.B.; Bourne, N.; Staples, J.E.; Mendez-Rico, J.A.; Harris, E.; Brault, A.C.; Ko, A.I.; et al. Zika virus: Advancing a priority research agenda for preparedness and response. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, E390–E401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, G.L.; Hills, S.L.; Fischer, M.; Jacobson, J.A.; Hoke, C.H.; Hombach, J.M.; Marfin, A.A.; Solomon, T.; Tsai, T.F.; Tsu, V.D.; et al. Estimated global incidence of Japanese encephalitis: A systematic review. Bull. World Health Organ. 2011, 89, 766–774, 774A–774E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraris, P.; Yssel, H.; Missé, D. Zika virus infection: An update. Microbes Infect. 2019, 21, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xu, D.; Ye, Q.; Hong, S.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, N.; Shi, L.; Qin, C.F.; Xu, Z. Zika Virus Disrupts Neural Progenitor Development and Leads to Microcephaly in Mice. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 19, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlakar, J.; Korva, M.; Tul, N.; Popovic, M.; Poljsak-Prijatelj, M.; Mraz, J.; Kolenc, M.; Resman Rus, K.; Vesnaver Vipotnik, T.; Fabjan Vodusek, V.; et al. Zika Virus Associated with Microcephaly. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Fu, S.; Wang, H.; Lu, Z.; Cao, Y.; He, Y.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, T.; et al. Vaccine strategies for the control and prevention of Japanese encephalitis in Mainland China, 1951–2011. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Duan, Z.; Zhou, W.; Zou, W.; Jin, S.; Li, D.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Japanese encephalitis virus-primed CD8+ T cells prevent antibody-dependent enhancement of Zika virus pathogenesis. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20192152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhen, Z.; Turtle, L.; Hou, B.; Li, Y.; Wu, N.; Gao, N.; Fan, D.; Chen, H.; An, J. T cell immunity rather than antibody mediates cross-protection against Zika virus infection conferred by a live attenuated Japanese encephalitis SA14-14-2 vaccine. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 6779–6789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaiboullina, S.; Uppal, T.; Martynova, E.; Rizvanov, A.; Baranwal, M.; Verma, S.C. History of ZIKV Infections in India and Management of Disease Outbreaks. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutsuna, S.; Kato, Y.; Takasaki, T.; Moi, M.; Kotaki, A.; Uemura, H.; Matono, T.; Fujiya, Y.; Mawatari, M.; Takeshita, N.; et al. Two cases of Zika fever imported from French Polynesia to Japan, December 2013 to January 2014. Euro Surveill. Bull. Eur. Sur Les Mal. Transm. = Eur. Commun. Dis. Bull. 2014, 19, pii: 20683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quyen, N.T.H.; Kien, D.T.H.; Rabaa, M.; Tuan, N.M.; Vi, T.T.; Van Tan, L.; Hung, N.T.; Tuan, H.M.; Van Tram, T.; Le Da Ha, N.; et al. Chikungunya and Zika Virus Cases Detected against a Backdrop of Endemic Dengue Transmission in Vietnam. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 97, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruchusatsawat, K.; Wongjaroen, P.; Posanacharoen, A.; Rodriguez-Barraquer, I.; Sangkitporn, S.; Cummings, D.A.T.; Salje, H. Long-term circulation of Zika virus in Thailand: An observational study. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 439–446, Correction in Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, E109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Wong, G.; Bi, Y.; Yan, J.; Sun, Y.; Chen, E.; Yan, H.; Lou, X.; Mao, H.; et al. Highly diversified Zika viruses imported to China, 2016. Protein Cell 2016, 7, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirohi, D.; Chen, Z.; Sun, L.; Klose, T.; Pierson, T.C.; Rossmann, M.G.; Kuhn, R.J. The 3.8 A resolution cryo-EM structure of Zika virus. Science 2016, 352, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modis, Y.; Ogata, S.; Clements, D.; Harrison, S.C. A ligand-binding pocket in the dengue virus envelope glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 6986–6991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenhuis-Zybert, I.A.; Wilschut, J.; Smit, J.M. Partial maturation: An immune-evasion strategy of dengue virus? Trends Microbiol. 2011, 19, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Sun, Y.; Liang, X.; Gu, X.; Ning, J.; Xu, Y.; Chen, S.; Pan, L. Emerging new therapeutic antibody derivatives for cancer treatment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.S.; Yan, Y.S.; Ho, K. US FDA-approved therapeutic antibodies with high-concentration formulation: Summaries and perspectives. Antib. Ther. 2021, 4, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansel, T.T.; Kropshofer, H.; Singer, T.; Mitchell, J.A.; George, A.J. The safety and side effects of monoclonal antibodies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevendal, A.T.K.; Hurley, S.; Bartlett, A.W.; Rawlinson, W.; Walker, G.J. Systematic Review of the Efficacy and Safety of RSV-Specific Monoclonal Antibodies and Antivirals in Development. Rev. Med. Virol. 2024, 34, e2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markham, A. Ibalizumab: First Global Approval. Drugs 2018, 78, 781–785, Correction in Drugs 2018, 78, 859. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-018-0926-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, H.; Hobbs, F.D.R.; Padilla, F.; Arbetter, D.; Templeton, A.; Seegobin, S.; Kim, K.; Campos, J.A.S.; Arends, R.H.; Brodek, B.H.; et al. Efficacy and safety of intramuscular administration of tixagevimab-cilgavimab for early outpatient treatment of COVID-19 (TACKLE): A phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, C.; Carbaugh, D.L.; Shu, B.; Ng, T.S.; Castillo, I.N.; Bhowmik, R.; Segovia-Chumbez, B.; Puhl, A.C.; Graham, S.; Diehl, S.A.; et al. Structure and neutralization mechanism of a human antibody targeting a complex Epitope on Zika virus. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1010814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, M.J.; Broecker, F.; Freyn, A.W.; Choi, A.; Brown, J.A.; Fedorova, N.; Simon, V.; Lim, J.K.; Evans, M.J.; García-Sastre, A.; et al. Human Monoclonal Antibodies Potently Neutralize Zika Virus and Select for Escape Mutations on the Lateral Ridge of the Envelope Protein. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00405-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.H.; Tu, H.A.; Gimblet-Ochieng, C.; Liou, G.A.; Jadi, R.S.; Metz, S.W.; Thomas, A.; McElvany, B.D.; Davidson, E.; Doranz, B.J.; et al. Human antibody response to Zika targets type-specific quaternary structure epitopes. JCI Insight 2019, 4, 124588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussupt, V.; Sankhala, R.S.; Gromowski, G.D.; Donofrio, G.; De La Barrera, R.A.; Larocca, R.A.; Zaky, W.; Mendez-Rivera, L.; Choe, M.; Davidson, E.; et al. Potent Zika and dengue cross-neutralizing antibodies induced by Zika vaccination in a dengue-experienced donor. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.S.; Miller, A.; Sapparapu, G.; Fernandez, E.; Klose, T.; Long, F.; Fokine, A.; Porta, J.C.; Jiang, W.; Diamond, M.S.; et al. A human antibody against Zika virus crosslinks the E protein to prevent infection. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, F.; Doyle, M.; Fernandez, E.; Miller, A.S.; Klose, T.; Sevvana, M.; Bryan, A.; Davidson, E.; Doranz, B.J.; Kuhn, R.J.; et al. Structural basis of a potent human monoclonal antibody against Zika virus targeting a quaternary epitope. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 1591–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, D.M.; Rogers, T.F.; Beutler, N.; Ricciardi, M.J.; Bailey, V.K.; Gonzalez-Nieto, L.; Briney, B.; Sok, D.; Le, K.; Strubel, A.; et al. Neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies prevent Zika virus infection in macaques. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, 8184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbiani, D.F.; Bozzacco, L.; Keeffe, J.R.; Khouri, R.; Olsen, P.C.; Gazumyan, A.; Schaefer-Babajew, D.; Avila-Rios, S.; Nogueira, L.; Patel, R.; et al. Recurrent Potent Human Neutralizing Antibodies to Zika Virus in Brazil and Mexico. Cell 2017, 169, 597–609 e511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapparapu, G.; Fernandez, E.; Kose, N.; Bin, C.; Fox, J.M.; Bombardi, R.G.; Zhao, H.; Nelson, C.A.; Bryan, A.L.; Barnes, T.; et al. Neutralizing human antibodies prevent Zika virus replication and fetal disease in mice. Nature 2016, 540, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stettler, K.; Beltramello, M.; Espinosa, D.A.; Graham, V.; Cassotta, A.; Bianchi, S.; Vanzetta, F.; Minola, A.; Jaconi, S.; Mele, F.; et al. Specificity, cross-reactivity, and function of antibodies elicited by Zika virus infection. Science 2016, 353, 823–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, H.; Liu, X.; Dai, L.; Ma, T.; Qi, J.; Wong, G.; Peng, R.; Liu, S.; Li, J.; et al. Molecular determinants of human neutralizing antibodies isolated from a patient infected with Zika virus. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 369ra179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Wang, R.; Gao, F.; Li, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Hong, W.; Zhao, L.; Wen, Y.; Yin, C.; et al. Delineating antibody recognition against Zika virus during natural infection. JCI Insight 2017, 2, 93042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Loy, T.; Ng, T.S.; Lim, X.N.; Chew, S.V.; Tan, T.Y.; Xu, M.; Kostyuchenko, V.A.; Tukijan, F.; Shi, J.; et al. A Human Antibody Neutralizes Different Flaviviruses by Using Different Mechanisms. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, E.; Kose, N.; Edeling, M.A.; Adhikari, J.; Sapparapu, G.; Lazarte, S.M.; Nelson, C.A.; Govero, J.; Gross, M.L.; Fremont, D.H.; et al. Mouse and Human Monoclonal Antibodies Protect against Infection by Multiple Genotypes of Japanese Encephalitis Virus. mBio 2018, 9, e00008-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Lei, Y.; Yang, P.; Gao, Q.; Wang, N.; Cao, L.; Yuan, S.; Huang, X.; Deng, Y.; Ma, W.; et al. Structural basis for neutralization of Japanese encephalitis virus by two potent therapeutic antibodies. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 3, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.J.; Wang, M.J.; Jiang, S.Z.; Ma, W.Y. Passive protection of mice, goats, and monkeys against Japanese encephalitis with monoclonal antibodies. J. Med. Virol. 1989, 29, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvert, A.E.; Bennett, S.L.; Dixon, K.L.; Blair, C.D.; Roehrig, J.T. A Monoclonal Antibody Specific for Japanese Encephalitis Virus with High Neutralizing Capability for Inclusion as a Positive Control in Diagnostic Neutralization Tests. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 101, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, T.; Masaki, H.; Takasaki, T.; Aoyama, I.; Yumisashi, T.; Yamanaka, A.; Konishi, E.; Ohnuki, Y.; Muraguchi, A.; Kishi, H. Human monoclonal antibodies against West Nile virus from Japanese encephalitis-vaccinated volunteers. Antivir. Res. 2018, 154, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Chen, J.; Ni, H.; Wen, J. A human monoclonal antibody isolated from Japanese encephalitis virus vaccine-vaccinated volunteer neutralizing various flaviviruses. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1508923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrowsky, J.T.; Katzelnick, L.C.; Bourne, N.; Barrett, A.D.T.; Thomas, S.J.; Diamond, M.S.; Beasley, D.W.C.; Harris, E.; Wilder-Smith, A.; Leighton, T.; et al. Zika virus vaccines and monoclonal antibodies: A priority agenda for research and development. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, E402–E415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; He, C.; Liu, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhang, J.; Chen, D.; Ni, H.; Wen, J. An engineered Japanese encephalitis virus mRNA-lipid nanoparticle immunization induces protective immunity in mice. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1472824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Fernandez, E.; Dowd, K.A.; Speer, S.D.; Platt, D.J.; Gorman, M.J.; Govero, J.; Nelson, C.A.; Pierson, T.C.; Diamond, M.S.; et al. Structural Basis of Zika Virus-Specific Antibody Protection. Cell 2016, 166, 1016–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Gao, Y.; Shen, C.; Yang, W.; Peng, Q.; Cheng, J.; Shen, H.M.; Yang, Y.; Gao, G.F.; Shi, Y. A human monoclonal antibody targeting the monomeric N6 neuraminidase confers protection against avian H5N6 influenza virus infection. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Ho, M. Humanization of high-affinity antibodies targeting glypican-3 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Nishimura, M.; Maekawa, Y.; Kotari, T.; Okuno, T.; Mori, Y. Humanization of Murine Neutralizing Antibodies against Human Herpesvirus 6B. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e02270-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettleborough, C.A.; Saldanha, J.; Heath, V.J.; Morrison, C.J.; Bendig, M.M. Humanization of a mouse monoclonal antibody by CDR-grafting: The importance of framework residues on loop conformation. Protein Eng. 1991, 4, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaborators GDaI: Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [CrossRef]

- Reasults GBoDSG: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) 2021. Available online: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool (accessed on 12 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, J.; Ni, H.; Chen, D.; Zhang, M.; Fang, Y.; Ma, C.; Wang, S.; Chen, J.; et al. Generation of a Human–Mouse Chimeric Anti-Japanese Encephalitis Virus and Zika Virus Monoclonal Antibody Using CDR Grafting. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2868. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122868

Liu Y, Zhang J, Zhu J, Ni H, Chen D, Zhang M, Fang Y, Ma C, Wang S, Chen J, et al. Generation of a Human–Mouse Chimeric Anti-Japanese Encephalitis Virus and Zika Virus Monoclonal Antibody Using CDR Grafting. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2868. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122868

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yusha, Jiayi Zhang, Jiayang Zhu, Hongxia Ni, Dong Chen, Meiqing Zhang, Yuqian Fang, Cheng Ma, Shuangwei Wang, Jie Chen, and et al. 2025. "Generation of a Human–Mouse Chimeric Anti-Japanese Encephalitis Virus and Zika Virus Monoclonal Antibody Using CDR Grafting" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2868. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122868

APA StyleLiu, Y., Zhang, J., Zhu, J., Ni, H., Chen, D., Zhang, M., Fang, Y., Ma, C., Wang, S., Chen, J., Zheng, Y., Chi, L., Cai, L., & Wen, J. (2025). Generation of a Human–Mouse Chimeric Anti-Japanese Encephalitis Virus and Zika Virus Monoclonal Antibody Using CDR Grafting. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2868. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122868