Abstract

Escherichia coli sequence type 648 (ST648), a lineage within the clinically important phylogroup F, has disseminated worldwide in humans and animals. In this study, we performed whole-genome sequencing and comparative genomic analysis for two New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (blaNDM-5) carrying E. coli strains: ECsOL198, recovered from a wild Eurasian otter in Northern Lebanon, and ECOL247, isolated from a hospitalized leukemia patient. Both isolates belonged to phylogroup F and serotype O9:H4, and exhibited IncFIA, IncFIB, and IncFII plasmids. They shared a similar antimicrobial resistance profile, including a carbapenemase gene (blaNDM-5), β-lactamase genes (blaTEM-1, blaCTX-M-15, and blaOXA-1), and other genes that confer resistance to aminoglycosides (acc(3)-Ile, aadA2), sulfonamides (sul1), tetracyclines (tet(A)), and fluoroquinolones (mutations in gyrA and parC). Both isolates also carried common virulence-associated genes related to adhesion, iron acquisition, environmental persistence, and immune evasion. Whole-genome multilocus sequence typing (wgMLST) revealed that both isolates formed a distinct subclade closely related to a bloodstream-derived ST648 isolate from India, indicating limited relatedness to global clones. These findings highlight the transmission of nearly clonal multidrug-resistant E. coli ST648 in both clinical and non-clinical settings, raising concerns about the threat to public health.

1. Introduction

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is an important Gram-negative bacterium that commonly inhabits the gut of humans and warm-blooded animals. Although most E. coli strains are considered harmless, others can potentially cause serious enteric and extra-intestinal infections in both humans and animals [1]. Among these, E. coli ST648 is reported globally as an emerging resistance-associated lineage that occurs as a pathogen and commensal in humans and animals and in the environment [2]. E. coli is highly clonal, as it is recognized with eight major phylogroups (A, B1, B2, C, D, E, F, and clade I) that comprise several unique sequence types (ST) detected by multilocus sequence typing (MLST) [3].

ST648 clone is recognized for its high pathogenic potential, due to its frequent carriage of antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes. Strains of this lineage often harbor resistance determinants to critical antibiotics, such as extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) like blaCTX-M, carbapenemases such as blaNDM, and the colistin resistance gene mcr-1, posing a significant public health threat. Clinical isolates of ST648 are typically extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) and are associated with bacteremia, respiratory, urinary, and wound infections. The global burden of antimicrobial resistance highlights E. coli, including ST648, among the leading causes of death due to antibiotic-resistant infections [4].

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in ST648 includes resistance to fluoroquinolones, third-generation cephalosporins, carbapenems, and other antibiotics [5]. Over the last decade, carbapenems have been recognized as last-resort antibiotics for the treatment of severe bacterial infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria [6]. The emergence of carbapenem-resistant E. coli (CREC) has increased rapidly over the last decades and significantly limited therapeutic options [7]. One of the most clinically significant carbapenemases is the New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM), which has shown rapid evolution and global dissemination [8]. Among NDM variants, blaNDM-5 is particularly concerning due to its enhanced carbapenem resistance, attributed to two amino acid substitutions (Val88Leu and Met154Leu) [9]. It was first identified in 2011 in the MDR E. coli ST648 isolate in the United Kingdom [10]. Since then, NDM-producing ST648 E. coli strains have been reported in several countries, including Japan [11], Algeria [12], the United Kingdom, and India [13].

blaNDM-5 is mostly associated with international high-risk E. coli clones, such as ST167, ST361, ST405, ST410, and ST648, which cause extraintestinal and nosocomial infections in humans [14,15,16]. Notably, the first report of E. coli ST648 and ST156 co-producing blaNDM-5 and mcr-1 was from a single Muscovy duck (Cairina moschata) [17]. Furthermore, a 2019 study from China identified the presence of blaNDM-5-producing E. coli in migratory birds [18]. Despite the scarcity of data on carbapenemase-producing E. coli in wildlife, this sector has been increasingly recognized as an important natural reservoir and disseminator of AMR. The aim of this study was to characterize multidrug-resistant, blaNDM-5-carrying E. coli belonging to ST648, isolated from a Eurasian otter and a hospitalized patient in Lebanon. We performed whole-genome sequencing on both isolates using short- and long-read sequencing and phylogenetic comparison with publicly available E. coli ST648 genomes to assess the genetic relatedness of carbapenem-resistant isolates from other geographic regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Isolation and Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

As part of a wildlife surveillance program conducted by the Lebanese Wildlife Team, a carbapenem-resistant E. coli (CREC) isolate, designated ECOL198, was recovered from a Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra). The otter was alive and wild-caught, and fresh fecal samples (<24 h) were collected aseptically in sterile 15 mL Falcon tubes (Corning®, New York, NY, USA). In parallel, another CREC isolate, ECOL247, was obtained during routine clinical testing at the bacteriology laboratories of the American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUB-MC) (Beirut, Lebanon). For further genomic study, ECOL247 was received and transported aseptically under refrigeration conditions (4 °C) at the Experimental Pathology, Immunology, and Microbiology Research Laboratory at the American University of Beirut. Both isolates were identified and confirmed using API 20E strips (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed using the broth microdilution (BMD) against 14 different antimicrobials from 10 different antimicrobial classes: amikacin, aztreonam, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, cefepime, ceftazidime, cefuroxime, colistin, ertapenem, gentamicin, levofloxacin, meropenem, piperacillin/tazobactam, tetracycline, and ceftolozan/tazobactam. Commercially available 96-well microtiter plates (Corning 3788) were used for all broth microdilution assays. The control strain Escherichia coli ATCC® 25922 was used in parallel. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values were assessed according to the clinical breakpoints listed in the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) document M100Ed35 [19].

2.2. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Analysis

Genomic DNA was obtained using the Quick-DNA™ Fungal/Bacterial Miniprep kit, and then DNA was purified using the Genomic DNA Clean & Concentrator™ kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). Short-read whole-genome sequencing was carried out using the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

Long-read whole-genome sequencing was performed using the Oxford Nanopore MinION Mk1C platform (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK). Genomic DNA libraries were prepared with the Rapid Barcoding Kit 96 (SQK-RBK110.96) (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) and sequenced on R9.4.1 flow cells (FLO-MIN106) (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) following the manufacturer’s protocols. Raw sequencing data were processed using tools available on the UseGalaxy platform (https://usegalaxy.org/, accessed on 10 January 2024). Plasmid replicons with a cutoff of above 90% identity, multi-locus sequence typing (MLST), serotypes, phylogroups, pathogenicity, and virulence factors were identified using tools from the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (http://www.genomicepidemiology.org/, accessed on 24 January 2024) [20]. Antimicrobial resistance genes were detected using the CARD (https://card.mcmaster.ca/, accessed on 22 May 2024) and AMRFinder databases (version 3.12.8, accessed on 22 May 2024) [21].

2.3. Comparative Analyses of ST648 and blaNDM-5-Harboring Genomes

E. coli ST648 genomes and corresponding metadata were retrieved from the NCBI Genbank database. Both isolates analyzed in this study were compared with 30 previously sequenced E. coli genomes (Table A1). Whole-genome MLST-based phylogeny was conducted using the canu-wgMLST command-line pipeline (https://github.com/marbl/canu.git, accessed on 20 May 2024) (PMID: 31396192). The resulting Newick-format tree was visualized using the R packages ggplot2 (https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org, accessed on 22 May 2024) and ggtree (version 4.0.1, accessed on 22 May 2024) (PMID: 38867905).

2.4. Data Availability

The samples analyzed include BioProject PRJNA613441 with BioSamples SAMN44683810 (ECOL198), SAMN53307536 (ECOL198_Long), SAMN53235178 (ECOL247), and SAMN53307537 (ECOL247_Long). Accession numbers for the remaining samples in the phylogenetic tree are provided in Appendix A.

3. Results

3.1. Basic Genomic Features

In Silico genotyping revealed that both E. coli isolates, ECOL198 and ECOL247, belonged to ST648, phylogroup F, and O9:H4 serotype. PathogenFinder indicated both isolates as a potential human pathogen with a probability of 93.2%. Analysis of the sequences showed that the two isolates have comparable genomic properties, including genome size, GC content, and the number of contigs (Table 1). Further, plasmid replicons IncFIA, IncFIB (AP001918), and IncFII (pRSB107) were detected in both isolates. In addition, ECOL247 also harbored the Col (MG828) plasmid (Table 2).

Table 1.

Basic genomic characteristics of the animal and human isolates.

Table 2.

Detailed characteristics of the plasmids identified in E. coli isolates, ECOL198 and ECOL247.

3.2. Phenotype of E. coli Isolates

The detailed antimicrobial resistance profiles of both isolates are listed in Table 3. Both ECOL198 and ECOL247 exhibit broad multidrug resistance, with resistance to most β-lactams—including extended-spectrum cephalosporins, β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, monobactams, and carbapenems. They are also resistant to fluoroquinolones, sulfonamides, and tetracycline. They are only susceptible to colistin and amikacin, although gentamicin resistance persists in both strains. Overall, the profiles demonstrate a carbapenem-resistant, multidrug-resistant (MDR) phenotype.

Table 3.

The antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of the animal and human isolates to 14 antimicrobials were assessed using the broth microdilution (BMD) method. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for each isolate are reported, with R indicating resistance and S indicating susceptibility.

3.3. Antimicrobial Resistance Genes and Virulence Genes

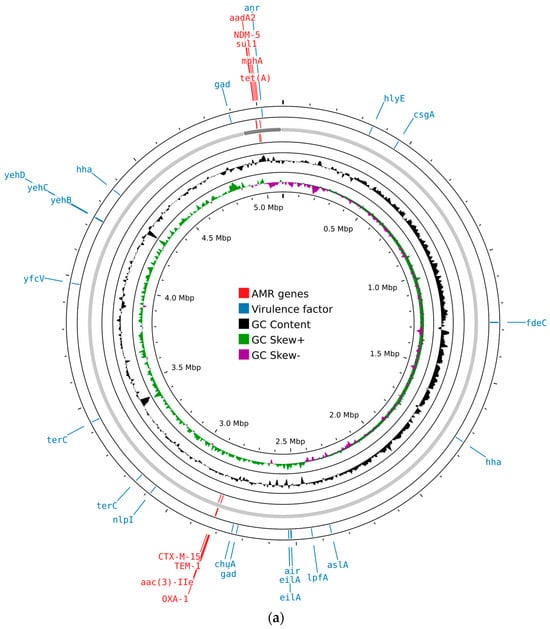

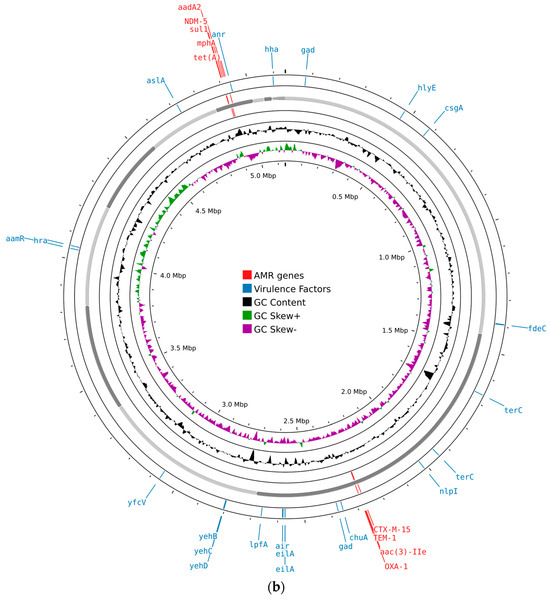

AMRFinder-based screening identified the carbapenemase gene blaNDM-5 and β-lactamase genes (blaTEM-1, blaCTX-M-15, and blaOXA-1), fluoroquinolone resistance-associated mutations in the genes gyrA and parC, a macrolide resistance gene (mphA), aminoglycoside resistance genes (acc(3)-lle, aadA2), a sulphonamide resistance gene (sul1), and a tetracycline resistance gene (tet(A)) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Circular maps of the genomic features of E. coli isolates generated using Proksee (https://proksee.ca/, accessed on 22 May 2024): (a) circular map of ECOL198; (b) circular map of ECOL247. Different features are shown in different colored bars, with virulence factors in blue and resistance genes in red.

Both E. coli isolates carried a range of virulence-associated genes. These included genes related to adhesion and invasion (aslA, chuA, csgA, fdeC, lpfA, and yfcV), iron uptake (chuA), and bacteriocin production (hlyE). Genes involved in protection against environmental stress and host defenses were also present, such as gad, hha, nlpI, and terC. In addition, genes responsible for capsule synthesis (yehB, yehC, and yehD) were detected. Other virulence factors included air, anr, and eilA, contributing to the overall pathogenic potential of the isolates (Figure 1).

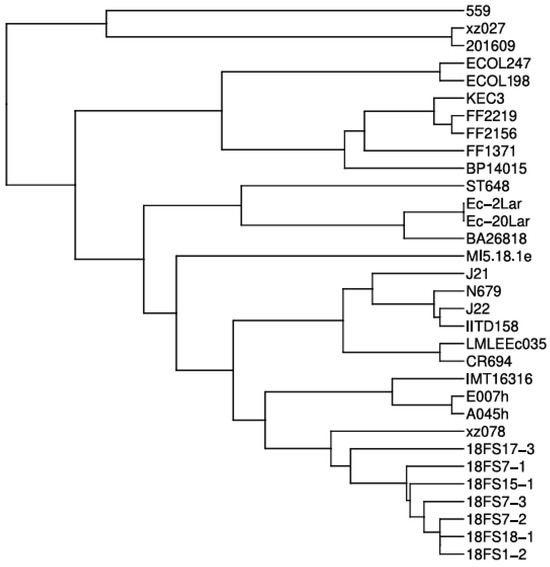

3.4. Comparative Analysis of the E. coli Isolates

To determine the phylogenetic relationship of both E. coli ST648 isolates with previously characterized global isolates carrying blaNDM-5, we performed whole-genome multilocus sequence typing (wgMLST) analysis (Figure 2). The results revealed that ECOL198 and ECOL247 clustered tightly together, suggesting a recent common ancestor and indicating a near-clonal relationship. These two isolates formed a distinct sub-clade with BP14015, a strain isolated from a patient’s blood in India, which branched off earlier in the tree. Notably, this clade also showed phylogenetic proximity to FF isolates (FF2137, FF2156, and FF2219) that were isolated from human clinical samples. Overall, our isolates formed a clearly separated clade, distinct from most publicly available global isolates, highlighting their unique phylogenetic position.

Figure 2.

Whole-genome multilocus sequence typing (wgMLST)-based phylogenetic tree of Escherichia coli ST648 isolates carrying blaNDM-5. The tree shows the evolutionary position of our isolates among globally distributed ST648 strains.

4. Discussion

The emergence of carbapenem-resistant E. coli, particularly high-risk clones such as ST648, poses a significant threat to public health. Worldwide, several studies have reported the presence of blaNDM-5-producing ST648 isolates in both clinical and non-clinical settings [22]. This study provided genomic and phenotypic features of blaNDM-5-carrying isolates, ECOL198 from a wild Eurasian otter and ECOL247 from a hospitalized patient in Lebanon. In addition, we evaluated the phylogenetic relationships of E. coli ST648 isolates from diverse sources, retrieved from public databases with sequenced draft genomes of our two isolates.

Interestingly, both isolates exhibited a high degree of genomic similarity: they belonged to phylogroup F and carried an identical set of beta-lactamase genes (blaNDM-5, blaTEM-1, blaCTX-M-15, and blaOXA-1). Both isolates harbored IncF plasmid types (IncFIA, IncFIB, and IncFII), which are known vehicles for horizontal gene transfer of AMR and virulence determinants. Studies have shown that E. coli ST648 is an emerging MDR, high-risk clonal lineage that is regularly detected in wild bird populations, waterfowl, companion animals, and humans [23]. Our detection of resistant E. coli ST648 in clinical and wildlife samples supports its classification as a host generalist rather than a specialist, capable of frequent cross-species transmission, thriving in various clinical and nonclinical settings [5]. Of particular concern is the detection of such clinically relevant multidrug-resistant bacteria in wildlife, which are typically not exposed to direct antibiotic pressure. This phenomenon is likely driven by increased human population and habitat fragmentation that forces humans and wild animals to be in closer proximity [24], or it could be due to environmental contamination, as water polluted with feces appears to be the most significant vector of contamination [25]. Overall, the presence of potentially pathogenic E. coli lineages such as ST648 in wildlife raises concerns about wildlife serving as reservoirs or spillover sources for high-risk E. coli clones. For example, an outbreak of E. coli infection resulting in 15 illnesses and two deaths was traced back to Oregon-grown strawberries contaminated with wild deer feces [26]. In another case, eight children contracted E. coli following exposure to wild Rocky Mountain elk feces on a soccer field in Colorado [27].

Additionally, PathogenFinder predicted both E. coli ST648 isolates to be potential human pathogens with a high probability score of 93.2%. This computational prediction aligns with the presence of several hallmark ExPEC-associated virulence genes in both genomes, including chuA, fdeC, yfcV, and hlyE, which are well-documented mediators of iron acquisition, adhesion, and toxin production in extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli. Among ExPEC, UPEC are defined as strains positive to two or more chuA loci, fyuA, vat, and yfcV [28]. According to these criteria, both E. coli ST648 strains studied likely have the potential to be uropathogens, as they carried both chuA and yfcV. Added to this, these isolates belong to phylogroup F, which is closely related to phylogroup B2 that includes the majority of strains associated with UTIs [3]. Moreover, the high pathogenicity score suggests that these isolates possess a genomic backbone compatible with human infection, even though one was derived from a wildlife source. This finding parallels previous findings demonstrating that wild animal species may be carriers of clinically important resistance and virulence determinants [29]. Similar findings have been reported in other studies where E. coli ST648 strains from environmental or animal origins displayed virulence and resistance profiles characteristic of human pathogens [23]. Notably, these results underscore the zoonotic potential of wildlife-associated ST648 strains and support the possibility of clonal dissemination and shared environmental exposure sources. It also highlights the relevance of a One Health surveillance approach to monitoring high-risk lineages circulating across environmental, animal, and human interfaces.

Whole-genome phylogenetic analysis demonstrated a near-clonal relationship between our two isolates, despite their origin from different hosts. They clustered together in a distinct subclade alongside a clinical isolate from India (BP14015), suggesting recent common ancestry and possibly regional dissemination of a unique ST648 lineage. Importantly, this subclade was phylogenetically distant from most other ST648 strains harboring blaNDM-5 present in public databases, indicating limited relatedness to global clones and pointing to a potentially localized evolutionary path.

5. Conclusions

The occurrence of carbapenem-resistant E. coli ST648 in human and non-human sources represents a growing threat. Wildlife serves as a significant reservoir, facilitating the transmission of resistance to humans and threatening public health. To effectively address this issue, it is essential to monitor antimicrobial resistance in wildlife through conducting nationwide surveillance programs that would adopt a “One Health” approach, recognizing the interdependence of human, animal, and environmental health. In this context, the multidrug resistance profiles of these isolates and their phylogenetic distinctness from global clones underscore the need for urgent action to monitor and control the spread of high-risk clones in both clinical and non-clinical settings. Urgent actions and public health policies must be implemented by local authorities and municipalities to prevent the spread of high-risk clones into the environment and animal populations. Such interventions may include enforcing strict regulations for the management of clinical waste from both healthcare facilities and households with infected individuals [30], as well as upgrading aging water infrastructure and ensuring that wastewater treatment plants are adequately maintained to effectively reduce microbial burdens, including antibiotic-resistant bacteria [31]. In addition, strengthening biosecurity measures in animal husbandry—such as keeping farm animals separated from wildlife and introducing vaccination programs—can help lower disease rates and reduce the need for antibiotics in animals [32].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.F.S., Z.C.J. and Z.R.H.; methodology, Z.F.S., Z.C.J., H.M.H. and Z.R.H.; software, Z.C.J., A.K., L.H. and R.M.; validation, A.G.A.F. and H.M.H.; formal analysis, A.G.A.F. and G.M.M.; investigation, Z.F.S., Z.C.J. and Z.R.H.; resources Z.F.S., Z.C.J. and Z.R.H.; data curation, Z.F.S., H.M.H. and Z.C.J.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.F.S.; writing—review and editing, Z.C.J., G.M.M. and Z.R.H.; visualization, A.G.A.F. and Z.C.J.; supervision, A.G.A.F., M.I.K., G.M.M. and R.E.H.; project administration, A.G.A.F.; funding acquisition, A.G.A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the American University of Beirut Institutional Review Board (AUB-IRB) committee to perform this work under the BIO-2023-0185 (5 April 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in GenBank at NCBI at https://account.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?back_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov%2Fmyncbi%2F, reference number BioProject 613441.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| CREC | Carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli |

| NDM | New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase |

| wgMLST | Whole-genome multilocus sequence typing |

Appendix A

Table A1.

E. coli ST648 isolates carrying blaNDM-5 present worldwide.

Table A1.

E. coli ST648 isolates carrying blaNDM-5 present worldwide.

| Continent | Geographic Location | Strain Name | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | China, Guangdong | 18FS17-3 | JADDNL010000046.1 |

| 18FS15-1 | JADDNO010000044.1 | ||

| 18FS18-1 | JADDNK010000029.1 | ||

| 18FS7-3 | JADDNP010000027.1 | ||

| 18FS7-2 | JADDNQ010000027.1 | ||

| 18FS7-1 | JADDNR010000031.1 | ||

| 18FS1-2 | JADDNX010000048.1 | ||

| China, Shandong | 559 | MOIL01000023.1 | |

| E007h | RYEE01000044.1 | ||

| A045h | RYEK01000045.1 | ||

| China, Xuzhou | xz027 | JAHQLA010000004.1 | |

| xz078 | JAHQMY010000031.1 | ||

| China, Beijing | strain_ST648 | CP008697 | |

| China | 201609 | CP048107 | |

| Bangladesh | LMLEEc035 | JACHQF010000062.1 | |

| India, Delhi | IITD158 | JAGJWJ010000056.1 | |

| India, Rajasthan | J21 | JADDOA010000102.1 | |

| J22 | JADDOB010000076.1 | ||

| India, Vellore | BA26818 | JACUXU010000057.1 | |

| BP14015 | JACUYT010000075.1 | ||

| FF1371 | JACUYY010000030.1 | ||

| FF2156 | JACUZC010000070.1 | ||

| FF2219 | JACUZD010000070.1 | ||

| Kenya, Nairobi | KEC3 | JABTVQ010000067.1 | |

| Lebanon | ECOL198 | SAMN44683810 | |

| ECOL198_Long | SAMN53307536 | ||

| ECOL247 | SAMN53235178 | ||

| ECOL247_Long | SAMN53307537 | ||

| Europe | Germany | IMT16316 | CP023815 |

| Greece | Ec_2Lar | CP035318 | |

| Ec_20Lar | CP035317 | ||

| Italy | MI5.18.1e | NZ_JAJSDB000000000.1 | |

| Switzerland | N679 | JADDLQ010000002.1 | |

| Oceania | Australia, Queensland | CR694 | JTGI01000069.1 |

References

- Bendary, M.M.; Abdel-Hamid, M.I.; Alshareef, W.A.; Alshareef, H.M.; Mosbah, R.A.; Omar, N.N.; Al-Sanea, M.M.; Alhomrani, M.; Alamri, A.S.; Moustafa, W.H. Comparative Analysis of Human and Animal E. coli: Serotyping, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Virulence Gene Profiling. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.R.; Johnston, B.D.; Gordon, D.M. Rapid and Specific Detection of the Escherichia coli Sequence Type 648 Complex within Phylogroup F. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 1116–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili, M.; Goli, H.; Javidnia, J.; Alipour, T.; Eslami, M. Genetic Diversity and Antibiotic Resistance Patterns of Escherichia coli Isolates Causing Septicemia: A Phylogenetic Typing and PFGE Analysis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2025, 111, 116586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronina, O.L.; Kunda, M.S.; Ryzhova, N.N.; Ermolova, E.I.; Goncharova, E.R.; Koroleva, E.A.; Kapotina, L.N.; Morgunova, E.Y.; Amelina, E.L.; Zigangirova, N.A. Chronic Escherichia coli ST648 Infections in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis: The In Vitro Effects of an Antivirulence Agent. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufler, K.; Semmler, T.; Wieler, L.H.; Trott, D.J.; Pitout, J.; Peirano, G.; Bonnedahl, J.; Dolejska, M.; Literak, I.; Fuchs, S.; et al. Genomic and Functional Analysis of Emerging Virulent and Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli Lineage Sequence Type 648. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e00243-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheu, C.-C.; Chang, Y.-T.; Lin, S.-Y.; Chen, Y.-H.; Hsueh, P.-R. Infections Caused by Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae: An Update on Therapeutic Options. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Gamal, M.I.; Brahim, I.; Hisham, N.; Aladdin, R.; Mohammed, H.; Bahaaeldin, A. Recent Updates of Carbapenem Antibiotics. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 131, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dortet, L.; Poirel, L.; Nordmann, P. Worldwide Dissemination of the NDM-Type Carbapenemases in Gram-Negative Bacteria. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 249856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, P.; Cheng, J.; Qin, S.; Xie, W. Characterization of a Novel BlaNDM-5-Harboring IncFII Plasmid and an Mcr-1-Bearing IncI2 Plasmid in a Single Escherichia coli ST167 Clinical Isolate. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M.; Phee, L.; Wareham, D.W. A Novel Variant, NDM-5, of the New Delhi Metallo-β-Lactamase in a Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli ST648 Isolate Recovered from a Patient in the United Kingdom. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 5952–5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, R.; Nakano, A.; Hikosaka, K.; Kawakami, S.; Matsunaga, N.; Asahara, M.; Ishigaki, S.; Furukawa, T.; Suzuki, M.; Shibayama, K.; et al. First Report of Metallo-β-Lactamase NDM-5-Producing Escherichia coli in Japan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 7611–7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sassi, A.; Loucif, L.; Gupta, S.K.; Dekhil, M.; Chettibi, H.; Rolain, J.-M. NDM-5 Carbapenemase-Encoding Gene in Multidrug-Resistant Clinical Isolates of Escherichia coli from Algeria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 5606–5608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Rahman, M.; Shukla, S.K.; Prasad, K.N.; Ovejero, C.M.; Pati, B.K.; Tripathi, A.; Singh, A.; Srivastava, A.K.; Gonzalez-Zorn, B. Prevalence and Molecular Characterisation of New Delhi Metallo-β-Lactamases NDM-1, NDM-5, NDM-6 and NDM-7 in Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae from India. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2014, 44, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, T.; Sadek, M.; Yao, Y.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Stephan, R.; Poirel, L.; Nordmann, P. Cross-Border Emergence of Escherichia coli Producing the Carbapenemase NDM-5 in Switzerland and Germany. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 59, e02238-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, Y.; Akeda, Y.; Hagiya, H.; Sakamoto, N.; Takeuchi, D.; Shanmugakani, R.K.; Motooka, D.; Nishi, I.; Zin, K.N.; Aye, M.M.; et al. Spreading Patterns of NDM-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Clinical and Environmental Settings in Yangon, Myanmar. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e01924-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, D.; Kerdsin, A.; Akeda, Y.; Sugawara, Y.; Sakamoto, N.; Matsumoto, Y.; Motooka, D.; Ishihara, T.; Nishi, I.; Laolerd, W.; et al. Nationwide Surveillance in Thailand Revealed Genotype-Dependent Dissemination of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales. Microb. Genom. 2022, 8, 000797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.-S.; Feng, Y.; Lv, X.-Y.; Duan, J.-H.; Chen, J.; Fang, L.-X.; Xia, J.; Liao, X.-P.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y.-H. Emergence of NDM-5- and MCR-1-Producing Escherichia coli Clones ST648 and ST156 from a Single Muscovy Duck (Cairina moschata). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 6899–6902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Yang, R.-S.; Xia, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, R.; Fang, L.-X.; Lei, F.; Song, G.; Jia, L.; Han, L.; et al. High Colonization Rate of a Novel Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella Lineage among Migratory Birds at Qinghai Lake, China. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 2895–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI M100; Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Malvern, PA, USA, 2025. Available online: https://clsi.org/shop/standards/m100/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Carattoli, A.; Zankari, E.; García-Fernández, A.; Voldby Larsen, M.; Lund, O.; Villa, L.; Møller Aarestrup, F.; Hasman, H. In Silico Detection and Typing of Plasmids Using PlasmidFinder and Plasmid Multilocus Sequence Typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 3895–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, E.-J.; Jeong, S.H. Mobile Carbapenemase Genes in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 614058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Yan, R.; Liu, C.; Zhai, J.; Zheng, J.; Chen, W.; Cao, X. Epidemiological and Genomic Characteristics of Global blaNDM-Carrying Escherichia coli. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2024, 23, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleichenbacher, S.; Stevens, M.J.A.; Zurfluh, K.; Perreten, V.; Endimiani, A.; Stephan, R.; Nüesch-Inderbinen, M. Environmental Dissemination of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Rivers in Switzerland. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 265, 115081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.; Abreu, R.; Serrano, I.; Such, R.; Garcia-Vila, E.; Quirós, S.; Cunha, E.; Tavares, L.; Oliveira, M. Resistant Escherichia coli Isolated from Wild Mammals from Two Rescue and Rehabilitation Centers in Costa Rica: Characterization and Public Health Relevance. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhouani, H.; Silva, N.; Poeta, P.; Torres, C.; Correia, S.; Igrejas, G. Potential Impact of Antimicrobial Resistance in Wildlife, Environment and Human Health. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidler, M.R.; Tourdjman, M.; Buser, G.L.; Hostetler, T.; Repp, K.K.; Leman, R.; Samadpour, M.; Keene, W.E. Escherichia coli O157:H7 Infections Associated with Consumption of Locally Grown Strawberries Contaminated by Deer. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 1129–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, A.B.; VerCauteren, K.C.; Maguire, H.; Cichon, M.K.; Fischer, J.W.; Lavelle, M.J.; Powell, A.; Root, J.J.; Scallan, E. Wild Ungulates as Disseminators of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli in Urban Areas. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammad, A.M.; Gonzalez-Escalona, N.; El Tahan, A.; Abbas, N.H.; Koenig, S.S.K.; Allué-Guardia, A.; Eppinger, M.; Hoffmann, M. Pathogenome Comparison and Global Phylogeny of Escherichia coli ST1485 Strains. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Mowlaboccus, S.; Jackson, B.; Cai, C.; Coombs, G.W. Antimicrobial Resistance among Clinically Significant Bacteria in Wildlife: An Overlooked One Health Concern. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2024, 64, 107251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musoke, D.; Namata, C.; Lubega, G.B.; Niyongabo, F.; Gonza, J.; Chidziwisano, K.; Nalinya, S.; Nuwematsiko, R.; Morse, T. The Role of Environmental Health in Preventing Antimicrobial Resistance in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2021, 26, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lübcke, P.; Heiden, S.E.; Homeier-Bachmann, T.; Bohnert, J.A.; Schulze, C.; Eger, E.; Schwabe, M.; Guenther, S.; Schaufler, K. Multidrug-Resistant High-Risk Clonal Escherichia coli Lineages Occur along an Antibiotic Residue Gradient in the Baltic Sea. Npj Clean Water 2024, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vora, N.M.; Hannah, L.; Walzer, C.; Vale, M.M.; Lieberman, S.; Emerson, A.; Jennings, J.; Alders, R.; Bonds, M.H.; Evans, J.; et al. Interventions to Reduce Risk for Pathogen Spillover and Early Disease Spread to Prevent Outbreaks, Epidemics, and Pandemics. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, e221079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).