The Mechanisms of Bacillus subtilis as a Plant-Beneficial Rhizobacterium in Plant–Microbe Interactions

Abstract

1. Introduction

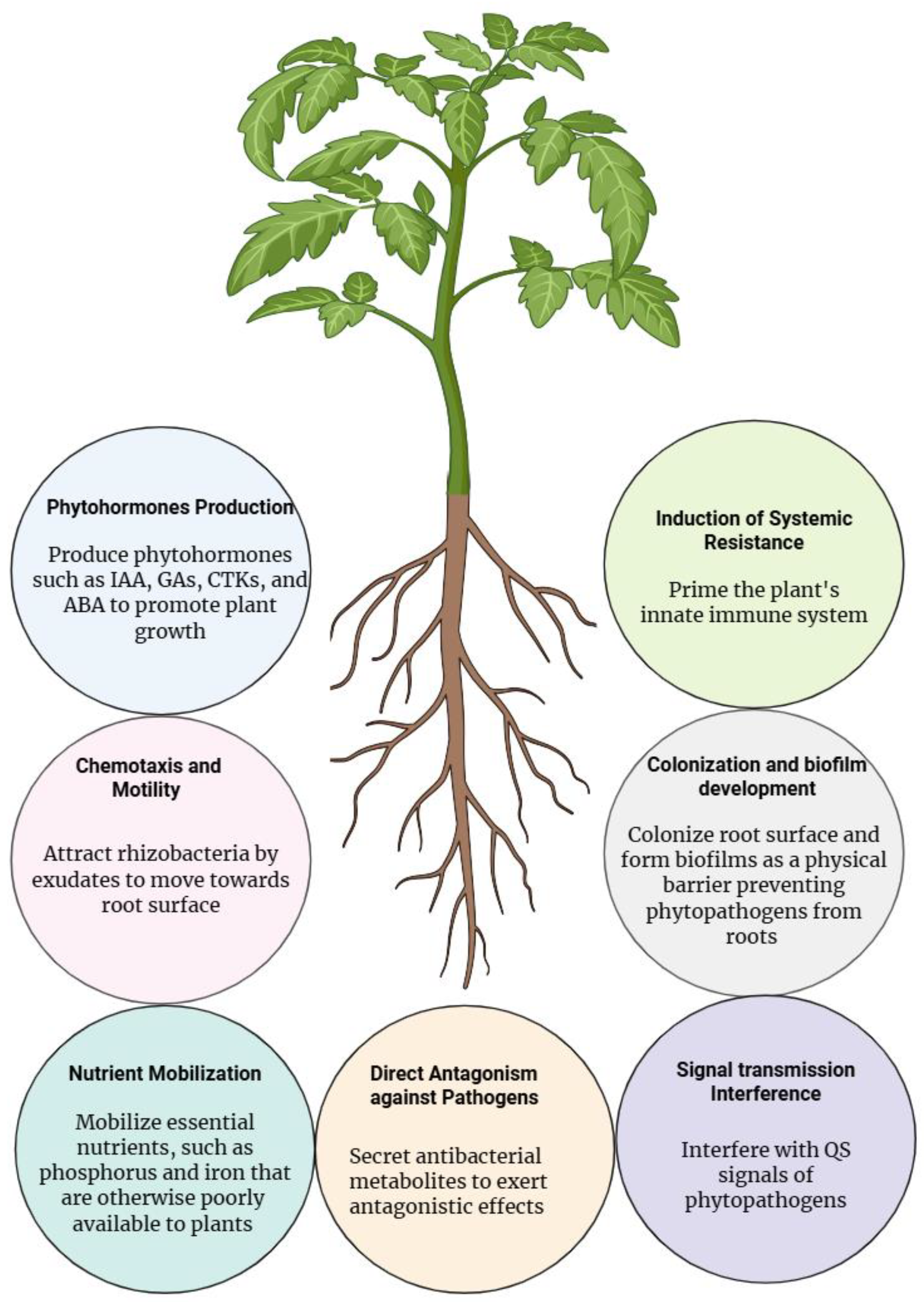

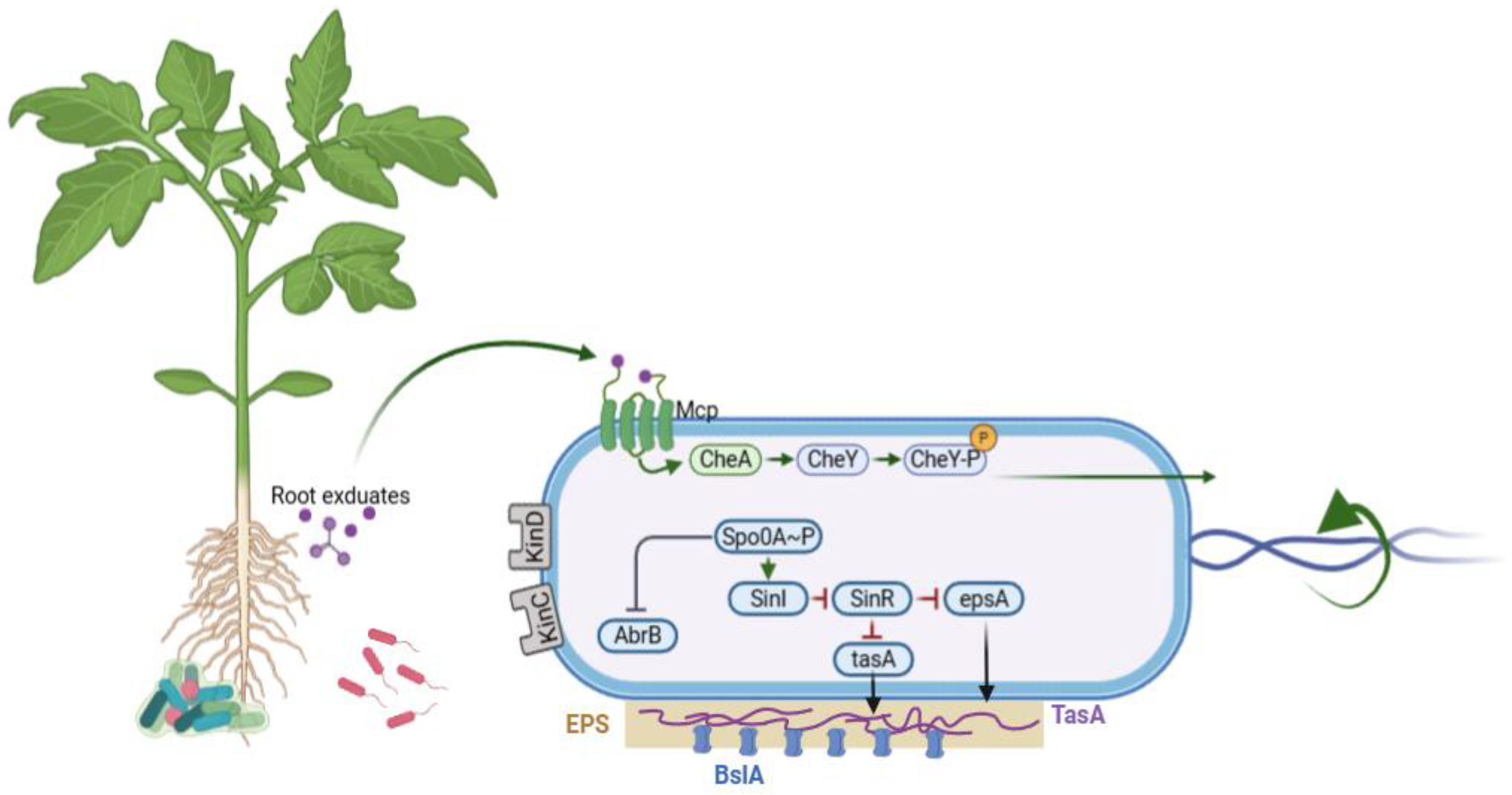

2. Biofilm Formation and Root Colonization

2.1. Cell Heterogeneity and Biofilm Development

2.2. Chemotaxis and Motility

3. Biocontrol and Disease Suppression

3.1. Signal Transduction Interference

3.2. Direct Antagonism Against Pathogens

3.3. Induction of Systemic Resistance

| Species | Tissues | Infection | Strains | Mechanisms/Mode of Action | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Stomata | Pseudomonas syringae | B. subtilis FB17 | Surfactin-mediated ISR, stomatal closure, and biofilm formation | [5] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Roots | Pseudomonas syringae | B. subtilis 6051 | Surfactin secretion and root biofilm formation | [62] |

| Solanum lycopersicum | Roots | Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato DC3000 | B. subtilis IAB/BS03 | Lipopeptide production (surfactin/iturin) and ISR pathway activation | [63] |

| Solanum lycopersicum | Leaf | Pseudomonas syringae pv. and Alternaria solani | B. subtilis | Systemic resistance interconnected via JA/ET pathways | [55] |

| Solanum tuberosum | Whole plants | Potato virus Y | B. subtilis EMCCN 1211 | Antiviral defense activation and reduction in PVY accumulation | [64] |

| Phaseolus vulgaris | Root | Pythium aphanidermatum | B. subtilis HE18 | ISR activation, root growth improvement, and degradation of pathogen structures | [65] |

| Passiflora edulis Sims | Stem and plant | Leaf Blight | B. subtilis GUCC4 | Antifungal metabolite production and colonization of stem tissues | [66] |

| Solanum lycopersicum | Roots and leaves | Alternaria solani | B. subtilis J3 | Regulation of resistance genes and antifungal secondary metabolites | [67] |

| Cucumis melo | Roots and leaves | Acidovorax citrulli | B. subtilis 9407 | Surfactin-mediated inhibition of Acidovorax biofilms; suppression of swarming motility | [47] |

| Solanum lycopersicum | Sprouting and seedling | Rhizoctonia rot | B. subtilis SL-13 | Chitinase secretion; inhibition of Rhizoctonia; growth promotion | [68] |

| Oryza sativa | Rice sheath | Rhizoctonia solani | B. subtilis 916 | Production of bacillomycin/surfactin; suppression of R. solani; reduced biofilm required for pathogenic attack | [50] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Seedling leaves | Erwinia carotovora | B. subtilis | Quorum-quenching, AHL degradation, VOC-mediated ISR | [69] |

4. Promotion of Plant Growth

4.1. Phytohormone Production

4.2. Nutrient Mobilization

| Species | Tissues | Strains | Effect on Plants | Hormones Implicated | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. thaliana | Leaves | B. subtilis | Improved stomatal responsiveness | Ethylene modulation via VOCs (2,3-butanediol) | [78] |

| A. thaliana | Leaves and roots | B. Subtilis GB03 | Balanced auxin distribution and increased lateral root formation | IAA (auxin) | |

| A. thaliana and T. aestivum | Seedlings | B. subtilis J-15 | Increased shoot biomass and delayed leaf senescence | Cytokinins and ethylene | [79] |

| N. tabacum | Root cells | B. subtilis OKB105 | Enhanced root elongation and increased cell expansion | Ethylene | [72] |

| Lettuce | Shoots and roots | B. subtilis | Higher biomass and delayed senescence | Cytokinins | |

| A. thaliana | Leaf surface area | B. Subtilis GB03 | Increased leaf area and higher photosynthetic capacity | Cytokinins and ethylene | |

| Trigonella foenum-graecum | Seedlings | B. subtilis ER-08 (BST) | Improved tolerance to salt/drought stress; increased biomass | ABA, cytokinins, ethylene | [61] |

| A. thaliana | Seedlings | B. subtilis GOT9 | Enhanced drought and salt tolerance | ABA, ethylene | [74] |

| T. aestivum | Seedlings | B. subtilis NA2 strain | Growth improvement under salinity | ABA, ethylene | [80] |

| wheat plants | Seedlings | B. strains NMCN1 and LLCG23 | Improved chlorophyll content; enhanced root architecture under stress | ABA | [81] |

| O. sativa L. | Seedlings | B. subtilis | Enhanced drought and salt tolerance; ABA-dependent regulation | ABA | [82] |

| H. vulgare L. | Roots | B. subtilis IB22 | ABA-dependent growth improvement under salt stress | ABA | [56] |

| Brachypodium distachyon | Seedlings | B. subtilis B26 | Increased biomass; enhance | ABA | [75] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Seedlings | B. Subtilis GB03 | Improved osmotic stress tolerance via VOC signaling | IAA, ABA interaction | [4] |

| Saccharum spp. | Roots and stalk | B. subtilis | Improved nutrient uptake; enhanced drought resilience | ABA, cytokinins | [73] |

| Phleum pratense | Seedlings, roots and shoots | B. subtilis B26 | Increased root/shoot biomass under drought | ABA | [76] |

| Brassica napus | Seedlings | B. subtilis XF-1 | Improved resistance to Plasmodiophora brassicae; healthier roots | IAA, ethylene, JA | [60] |

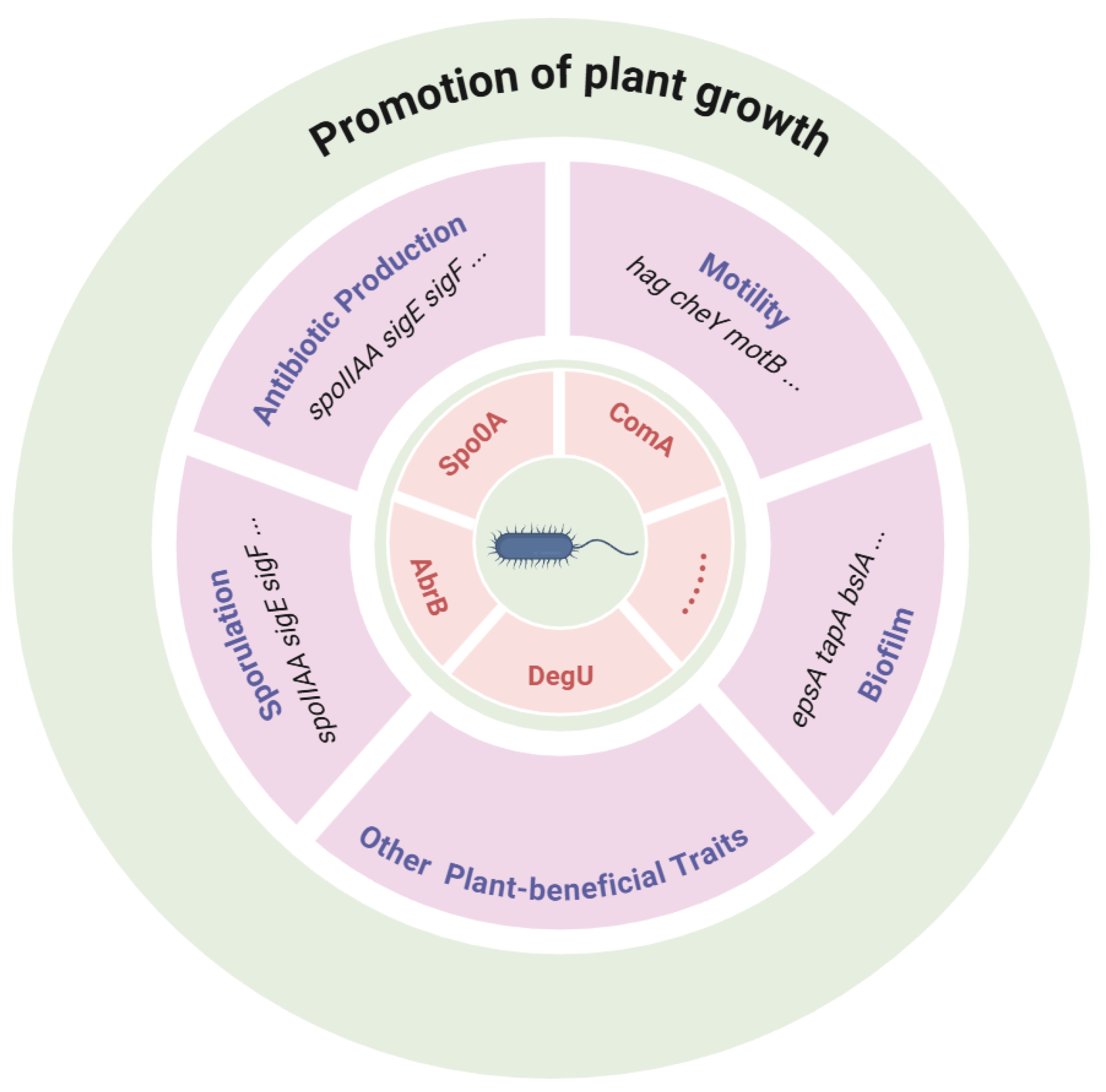

5. The Network and Regulation of Plant-Beneficial Traits

5.1. Connections Among Plant-Beneficial Traits

| Category | Genes/Operons | Function | Plant-Beneficial Role | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Regulators | Spo0A, DegU, ComA, SinR, SinI | Master transcriptional regulators | Coordinate sporulation, biofilm formation, and secondary metabolite production | [19] |

| Biofilm Formation and Colonization | EpsA, TapA, SipW, and TasA | Extracellular polysaccharides and amyloid fibers | Root colonization, biofilm stability, pathogen exclusion | [17] |

| Tli, and Mot | Flagella and motility proteins | Rhizosphere migration and root attachment | [21] | |

| Che | Chemoreceptors and signaling proteins | Chemotaxis toward plant root exudates | [41] | |

| Secondary Metabolite Clusters | Srf | Surfactin synthetase | Biofilm induction, ISR, antimicrobial activity | |

| Itu, and Fen | Iturin, fengycin, plipastatin synthetases | Strong antifungal activity and pathogen suppression | [20] | |

| Bac | Bacilysin biosynthesis | Broad-spectrum antibacterial and antifungal effects | ||

| Alb | Subtilosin A | Antimicrobial peptide | ||

| Dhb | Bacillibactin (siderophore) biosynthesis | Iron acquisition and competition with pathogens | ||

| Plant Growth Promotion | Gcd | Glucose dehydrogenase | Organic acid secretion and phosphate Mobilization | [56] |

| YsnE, and IpdC | Auxin (IAA) biosynthesis enzymes | Root growth promotion and architecture modulation | ||

| AlsS, and AlsD | Acetoin and 2,3-butanediol biosynthesis | VOC-mediated plant growth stimulation and stress tolerance | [28,29,30] | |

| GabT, and GabD | GABA metabolism | Plant–microbe signaling and stress modulation | ||

| Signal Integration and Regulation | ComX, ComP, and ComA | Quorum-sensing system | Controls competence and metabolite biosynthesis | [42] |

| Phr peptides | Quorum-sensing feedback modulators | Fine-tune population behavior in rhizosphere | ||

| DegS, DegU, PhoP, PhoR, ResD and ResE | Sensor–regulator systems | Adaptation to nutrient availability, oxygen, phosphate, and plant signals | [28,29,30] | |

| Stress Response and Adaptation | KatA, and SodA | Catalase and superoxide dismutase | Protection against oxidative stress in rhizosphere | [32] |

| SigB | General stress sigma factor | Global response to abiotic stress | [6,7] | |

| YvcC | Cell wall modification protein | Adaptation to plant-imposed stresses |

5.2. Genes and Their Regulation of Plant-Beneficial Traits

6. Summary and Future Perspectives

- Strain optimization for a specific application: Moving beyond model strains, research should prioritize the isolation and characterization of novel B. subtilis isolate with enhanced, specialized traits. This includes screening for superior biocontrol activity against specific high-impact pathogens (e.g., Fusarium wilt, R. solanacearum) and identifying strains with high resilience to prevent biotic stresses like drought and soil salinity.

- Decoding the molecular dialog: A deeper understanding of the specific molecular interaction is crucial. This requires employing omics studies such as transcriptomics and metabolomics to identify the key bacterial metabolites (e.g., specific lipopeptides, VOCs) and the corresponding plant genes they regulate. Elucidating this cross-kingdom signaling will allow for the rational design of more effective microbial consortia.

- Engineering effective microbial consortia: Rather than relying on single-strain inoculants, the future lies in designing synthetic microbial communities. Research should unravel the synergistic interactions between B. subtilis and other native beneficial microbes (e.g., mycorrhiza fungi, nitrogen-fixers) to create stable, multifunctional consortia that provide compounded benefits for plant health and soil fertility.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mendes, R.; Garbeva, P.; Raaijmakers, J.M. The rhizosphere microbiome: Significance of plant beneficial, plant pathogenic, and human pathogenic microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 634–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, F.; Wall, L.; Fabra, A. Starting points in plant-bacteria nitrogen-fixing symbioses: Intercellular invasion of the roots. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 1905–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, B.; Zaman, M.; Farooq, S.; Fatima, S.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Baba, Z.A.; Sheikh, T.A.; Reddy, M.S.; El Enshasy, H.; Gafur, A. Bacterial plant biostimulants: A sustainable way towards improving growth, productivity, and health of crops. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Murzello, C.; Sun, Y.; Kim, M.-S.; Xie, X.; Jeter, R.M.; Zak, J.C.; Dowd, S.E.; Paré, P.W. Choline and osmotic-stress tolerance induced in Arabidopsis by the soil microbe Bacillus subtilis (GB03). Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2010, 23, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.S.; Lakshmanan, V.; Caplan, J.L.; Powell, D.; Czymmek, K.J.; Levia, D.F.; Bais, H.P. Rhizobacteria Bacillus subtilis restricts foliar pathogen entry through stomata. Plant J. 2012, 72, 694–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoyo, G.; Urtis-Flores, C.A.; Loeza-Lara, P.D.; Orozco-Mosqueda, M.d.C.; Glick, B.R. Rhizosphere colonization determinants by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR). Biology 2021, 10, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Zhang, N.; Fu, R.; Liu, Y.; Krell, T.; Du, W.; Shao, J.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Recognition of dominant attractants by key chemoreceptors mediates recruitment of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 21, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Andrade, L.A.; Santos, C.H.B.; Frezarin, E.T.; Sales, L.R.; Rigobelo, E.C. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for sustainable agricultural production. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneduzi, A.; Ambrosini, A.; Passaglia, L.M. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR): Their potential as antagonists and biocontrol agents. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2012, 35, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljaković, D.; Marinković, J.; Balešević-Tubić, S. The significance of Bacillus spp. in disease suppression and growth promotion of field and vegetable crops. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, A.M.; Losick, R.; Kolter, R. Ecology and genomics of Bacillus subtilis. Trends Microbiol. 2008, 16, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rooney, A.P.; Price, N.P.; Ehrhardt, C.; Swezey, J.L.; Bannan, J.D. Phylogeny and molecular taxonomy of the Bacillus subtilis species complex and description of Bacillus subtilis subsp. inaquosorum subsp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 2429–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.K.; Mohammed, M.; Ibny, F.Y.; Dakora, F.D. Rhizobia as a source of plant growth-promoting molecules: Potential applications and possible operational mechanisms. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 4, 619676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemneh, A.; Zhou, Y.; Ryder, M.; Denton, M. Mechanisms in plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria that enhance legume–rhizobial symbioses. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 1133–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhusal, B.; Mmbaga, M. Biological control of Phytophthora blight and growth promotion in sweet pepper by Bacillus species. Biol. Control 2020, 150, 104373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaras, A.; Roumeliotis, E.; Ntasiou, P.; Karaoglanidis, G. Bacillus subtilis MBI600 promotes growth of tomato plants and induces systemic resistance contributing to the control of soilborne pathogens. Plants 2021, 10, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Montelongo, A.M.; Montoya-Martínez, A.C.; Morales-Sandoval, P.H.; Parra-Cota, F.I.; de Los Santos-Villalobos, S. Beneficial microorganisms as a sustainable alternative for mitigating biotic stresses in crops. Stresses 2023, 3, 210–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, K.; Earl, A.; Vlamakis, H.; Aguilar, C.; Kolter, R. Biofilm development with an emphasis on Bacillus subtilis. Bact. Biofilms 2008, 322, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Vlamakis, H.; Chai, Y.; Beauregard, P.; Losick, R.; Kolter, R. Sticking together: Building a biofilm the Bacillus subtilis way. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mutar, D.M.K.; Alzawar, N.S.A.; Noman, M.; Azizullah; Li, D.; Song, F. Suppression of fusarium wilt in watermelon by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens DHA55 through extracellular production of antifungal Lipopeptides. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, D.; Dworkin, J. Recent progress in Bacillus subtilis sporulation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard-Massicotte, R.; Tessier, L.; LÚcuyer, F.; Lakshmanan, V.; Lucier, J.-F.; Garneau, D.; Caudwell, L.; Vlamakis, H.; Bais, H.P.; Beauregard, P.B. Bacillus subtilis early colonization of Arabidopsis thaliana roots involves multiple chemotaxis receptors. MBio 2016, 7, e01664-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirouze, N.; Dubnau, D. Chance and necessity in Bacillus subtilis development. Bact. Spore Mol. Syst. 2016, 1, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanan, V.; Bais, H.P. Factors other than root secreted malic acid that contributes toward Bacillus subtilis FB17 colonization on Arabidopsis roots. Plant Signal. Behav. 2013, 8, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohsin, M.Z.; Omer, R.; Huang, J.; Mohsin, A.; Guo, M.; Qian, J.; Zhuang, Y. Advances in engineered Bacillus subtilis biofilms and spores, and their applications in bioremediation, biocatalysis, and biomaterials. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2021, 6, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemesh, M.; Chai, Y. A combination of glycerol and manganese promotes biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis via histidine kinase KinD signaling. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 2747–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaouteli, S.; Bamford, N.C.; Stanley-Wall, N.R.; Kovács, Á.T. Bacillus subtilis biofilm formation and social interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 600–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamathashree, C.; Girijesh, G.; Vinutha, B. Phosphorus dynamics in different soils. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2018, 7, 981–985. [Google Scholar]

- Saeid, A.; Prochownik, E.; Dobrowolska-Iwanek, J. Phosphorus solubilization by Bacillus species. Molecules 2018, 23, 2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, M.A.; Medeiros, F.H.; Carvalho, S.P.; Guilherme, L.R.; Teixeira, W.D.; Zhang, H.; Paré, P.W. Augmenting iron accumulation in cassava by the beneficial soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis (GBO3). Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, L.; Zhu, K.; Hou, S.; Chen, L.; Mi, D.; Gui, Y.; Qi, Y.; Jiang, C.; Guo, J.-H. Plant root exudates are involved in Bacillus cereus AR156 mediated biocontrol against Ralstonia solanacearum. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oslizlo, A.; Stefanic, P.; Dogsa, I.; Mandic-Mulec, I. Private link between signal and response in Bacillus subtilis quorum sensing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 1586–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mhatre, E.; Monterrosa, R.G.; Kovács, Á.T. From environmental signals to regulators: Modulation of biofilm development in Gram-positive bacteria. J. Basic Microbiol. 2014, 54, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.D.; Wolanin, P.M.; Stock, J.B. Signal transduction in bacterial chemotaxis. Bioessays 2006, 28, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, D.B. A field guide to bacterial swarming motility. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 634–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, D.B.; Losick, R. Swarming motility in undomesticated Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 49, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengistu, A.A. Endophytes: Colonization, behaviour, and their role in defense mechanism. Int. J. Microbiol. 2020, 2020, 6927219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wu, K.; He, X.; Li, S.-q.; Zhang, Z.-h.; Shen, B.; Yang, X.-m.; Zhang, R.-f.; Huang, Q.-w.; Shen, Q.-r. A new bioorganic fertilizer can effectively control banana wilt by strong colonization with Bacillus subtilis N11. Plant Soil 2011, 344, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsharkawy, M.M.; Elsawy, M.M.; Ismail, I.A. Mechanism of resistance to Cucumber mosaic virus elicited by inoculation with Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora, I.; Cabrefiga, J.; Montesinos, E. Cyclic lipopeptide biosynthetic genes and products, and inhibitory activity of plant-associated Bacillus against phytopathogenic bacteria. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Wu, H.; Yu, X.; Qian, L.; Gao, X. Swarming motility plays the major role in migration during tomato root colonization by Bacillus subtilis SWR01. Biol. Control 2016, 98, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, K.R.; Srinivasan, S.; Ravi, A.V. Inhibition of quorum sensing-mediated virulence in Serratia marcescens by Bacillus subtilis R-18. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 120, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Xiao, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, L.; Zheng, Z.; Yu, Z. Antagonistic effects of volatiles generated by Bacillus subtilis on spore germination and hyphal growth of the plant pathogen, Botrytis cinerea. Biotechnol. Lett. 2008, 30, 919–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, E.A.; Abd El-Shafea, Y.M. Biological control of potato soft rot caused by Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2018, 28, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, P. Surfactin and other lipopeptides from Bacillus spp. In Biosurfactants: From Genes to Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 57–91. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood, C.R.; Mouillon, J.-M.; Pohl, S.; Arnau, J. Secondary metabolite production and the safety of industrially important members of the Bacillus subtilis group. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 42, 721–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Duan, Y.; Wang, Q. Biocontrol of bacterial fruit blotch by Bacillus subtilis 9407 via surfactin-mediated antibacterial activity and colonization. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, M.; Kim, S.W.; Um, Y.H.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, S.C.; Song, J.Y.; Kim, H.G.; Lee, Y.S. Biological control of bacterial fruit blotch of watermelon pathogen (Acidovorax citrulli) with rhizosphere associated bacteria. Plant Pathol. J. 2017, 33, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabbene, O.; Azaiez, S.; Di Grazia, A.; Karkouch, I.; Ben Slimene, I.; Elkahoui, S.; Alfeddy, M.; Casciaro, B.; Luca, V.; Limam, F. Bacillomycin D and its combination with amphotericin B: Promising antifungal compounds with powerful antibiofilm activity and wound-healing potency. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 120, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Zhou, H.; Zou, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, R.; Xiang, Y.; Chen, Z. Bacillomycin L and surfactin contribute synergistically to the phenotypic features of Bacillus subtilis 916 and the biocontrol of rice sheath blight induced by Rhizoctonia solani. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 1897–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Khan, S.U.; Khan, W.U.; Saleh, T.A.; Khan, M.H.U.; Ullah, S.; Ali, A.; Ikram, M. Antagonist effects of strains of Bacillus spp. against Rhizoctonia solani for their protection against several plant diseases: Alternatives to chemical pesticides. Comptes Rendus Biol. 2019, 342, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, R.A.B.; Stedel, C.; Garagounis, C.; Nefzi, A.; Jabnoun-Khiareddine, H.; Papadopoulou, K.K.; Daami-Remadi, M. Involvement of lipopeptide antibiotics and chitinase genes and induction of host defense in suppression of Fusarium wilt by endophytic Bacillus spp. in tomato. Crop Prot. 2017, 99, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilani-Feki, O.; Khedher, S.B.; Dammak, M.; Kamoun, A.; Jabnoun-Khiareddine, H.; Daami-Remadi, M.; Tounsi, S. Improvement of antifungal metabolites production by Bacillus subtilis V26 for biocontrol of tomato postharvest disease. Biol. Control 2016, 95, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arienzo, R.; Maurano, F.; Mazzarella, G.; Luongo, D.; Stefanile, R.; Ricca, E.; Rossi, M. Bacillus subtilis spores reduce susceptibility to Citrobacter rodentium-mediated enteropathy in a mouse model. Res. Microbiol. 2006, 157, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Schenk, P.M.; Dart, P. Phyllosphere bacterial strains Rhizobium b1 and Bacillus subtilis b2 control tomato leaf diseases caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato and Alternaria solani. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 134, lxad139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtyamova, Z.; Arkhipova, T.; Martynenko, E.; Nuzhnaya, T.; Kuzmina, L.; Kudoyarova, G.; Veselov, D. Growth-promoting effect of rhizobacterium (Bacillus subtilis IB22) in salt-stressed barley depends on abscisic acid accumulation in the roots. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashem, A.; Tabassum, B.; Abd_Allah, E.F. Bacillus subtilis: A plant-growth promoting rhizobacterium that also impacts biotic stress. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 1291–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilham, B.; Noureddine, C.; Philippe, G.; Mohammed, E.G.; Brahim, E.; Sophie, A.; Muriel, M. Induced systemic resistance (ISR) in Arabidopsis thaliana by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and Trichoderma harzianum used as seed treatments. Agriculture 2019, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, D.K.; Prakash, A.; Johri, B. Induced systemic resistance (ISR) in plants: Mechanism of action. Indian J. Microbiol. 2007, 47, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Cui, W.; Munir, S.; He, P.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Yang, X.; Tang, P.; He, Y. Plasmodiophora brassicae root hair interaction and control by Bacillus subtilis XF-1 in Chinese cabbage. Biol. Control 2019, 128, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Islam, S.; Husain, F.M.; Yadav, V.K.; Park, H.-K.; Yadav, K.K.; Bagatharia, S.; Joshi, M.; Jeon, B.-H.; Patel, A. Bacillus subtilis ER-08, a multifunctional plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium, promotes the growth of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) plants under salt and drought stress. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1208743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bais, H.P.; Fall, R.; Vivanco, J.M. Biocontrol of Bacillus subtilis against infection of Arabidopsis roots by Pseudomonas syringae is facilitated by biofilm formation and surfactin production. Plant Physiol. 2004, 134, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinarejos, E.; Castellano, M.; Rodrigo, I.; Bellés, J.M.; Conejero, V.; López-Gresa, M.P.; Lisón, P. Bacillus subtilis IAB/BS03 as a potential biological control agent. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2016, 146, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.A.; El Kammar, H.F.; Saied, S.M.; Soliman, A.M. Effect of Bacillus subtilis on potato virus Y (PVY) disease resistance and growth promotion in potato plants. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2023, 167, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, Y.M.; El-Sharkawy, H.H.; Hafez, M.; Bourouah, M.; Abd-ElGawad, A.M.; Youssef, M.A.; Madbouly, A.K. Fostering resistance in common bean: Synergistic defense activation by Bacillus subtilis HE18 and Pseudomonas fluorescens HE22 against Pythium root rot. Rhizosphere 2024, 29, 100851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qin, S.; Fan, R.; Peng, Q.; Hu, X.; Yang, L.; Liu, Z.; Baccelli, I.; Migheli, Q.; Berg, G. Plant growth promotion and biocontrol of leaf blight caused by Nigrospora sphaerica on passion fruit by endophytic Bacillus subtilis strain GUCC4. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Mu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Fu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, H.; Yu, X.; Ye, Z. Biosynthetic pathways and functions of indole-3-acetic acid in microorganisms. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Jing, T.; Yujun, Y.; Bin, L.; Hui, L.; Chun, L. Biocontrol efficiency of Bacillus subtilis SL-13 and characterization of an antifungal chitinase. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2011, 19, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, C.-M.; Farag, M.A.; Hu, C.-H.; Reddy, M.S.; Kloepper, J.W.; Paré, P.W. Bacterial volatiles induce systemic resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004, 134, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerff, F.; Amoroso, A.; Herman, R.; Sauvage, E.; Petrella, S.; Filée, P.; Charlier, P.; Joris, B.; Tabuchi, A.; Nikolaidis, N. Crystal structure and activity of Bacillus subtilis YoaJ (EXLX1), a bacterial expansin that promotes root colonization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 16876–16881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, C.; Christensen, M.N.; Kovács, Á.T. Molecular aspects of plant growth promotion and protection by Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2021, 34, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.-S.; Wu, H.-J.; Zang, H.-Y.; Wu, L.-M.; Zhu, Q.-Q.; Gao, X.-W. Plant growth promotion by spermidine-producing Bacillus subtilis OKB105. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2014, 27, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, M.d.C.d.; Bossolani, J.W.; de Oliveira, S.L.; Moretti, L.G.; Portugal, J.R.; Scudeletti, D.; de Oliveira, E.F.; Crusciol, C.A.C. Bacillus subtilis inoculation improves nutrient uptake and physiological activity in sugarcane under drought stress. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, O.-G.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.-S.; Keum, H.L.; Lee, K.-C.; Sul, W.J.; Lee, J.-H. Bacillus subtilis strain GOT9 confers enhanced tolerance to drought and salt stresses in Arabidopsis thaliana and Brassica campestris. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagné-Bourque, F.; Mayer, B.F.; Charron, J.-B.; Vali, H.; Bertrand, A.; Jabaji, S. Accelerated growth rate and increased drought stress resilience of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon colonized by Bacillus subtilis B26. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagné-Bourque, F.; Bertrand, A.; Claessens, A.; Aliferis, K.A.; Jabaji, S. Alleviation of drought stress and metabolic changes in timothy (Phleum pratense L.) colonized with Bacillus subtilis B26. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Gao, C.; Lu, Y.; Sheng, Y.; Xiao, M.; Yun, Y.; Selvaraj, J.N.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. Endophytic bacteria for Cd remediation in rice: Unraveling the Cd tolerance mechanisms of Cupriavidus metallidurans CML2. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 469, 133846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Li, X.; Ma, L.; Borriss, R.; Wu, Z.; Gao, X. Acetoin and 2,3-butanediol from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens induce stomatal closure in Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana benthamiana. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 5625–5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, S.; Ma, M.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, D. Metabolites from Bacillus subtilis J-15 affect seedling growth of Arabidopsis thaliana and cotton plants. Plants 2022, 11, 3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, S.; Javed, S.; Azeem, M.; Aftab, A.; Anwaar, N.; Mehmood, T.; Zeshan, B. Application of Bacillus subtilis for the alleviation of salinity stress in different cultivars of Wheat (Tritium aestivum L.). Agronomy 2023, 13, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, M.; Ali, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, R.; Wang, Z.; Mu, G.; Khan, S.A.; Khan, A.R.; Manghwar, H.; Wu, H. Salt tolerant Bacillus strains improve plant growth traits and regulation of phytohormones in wheat under salinity stress. Plants 2022, 11, 2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddika, A.; Rashid, A.A.; Khan, S.N.; Khatun, A.; Karim, M.M.; Prasad, P.V.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Harnessing plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria, Bacillus subtilis and B. aryabhattai to combat salt stress in rice: A study on the regulation of antioxidant defense, ion homeostasis, and photosynthetic parameters. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1419764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, C.; Xu, J.; Qi, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Peng, D.; Ruan, L. Endophyte Bacillus subtilis evade plant defense by producing lantibiotic subtilomycin to mask self-produced flagellin. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Liang, Y.; Wu, M.; Chen, Z.; Lin, J.; Yang, L. Natural products from Bacillus subtilis with antimicrobial properties. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2015, 23, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adjei, M.O.; Yu, R.; Cao, X.; Fan, B. The Mechanisms of Bacillus subtilis as a Plant-Beneficial Rhizobacterium in Plant–Microbe Interactions. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2823. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122823

Adjei MO, Yu R, Cao X, Fan B. The Mechanisms of Bacillus subtilis as a Plant-Beneficial Rhizobacterium in Plant–Microbe Interactions. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2823. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122823

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdjei, Mark Owusu, Ruohan Yu, Xianming Cao, and Ben Fan. 2025. "The Mechanisms of Bacillus subtilis as a Plant-Beneficial Rhizobacterium in Plant–Microbe Interactions" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2823. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122823

APA StyleAdjei, M. O., Yu, R., Cao, X., & Fan, B. (2025). The Mechanisms of Bacillus subtilis as a Plant-Beneficial Rhizobacterium in Plant–Microbe Interactions. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2823. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122823