Genetic Diversity of Siberian Isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi Sensu Lato by the ospA Gene

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

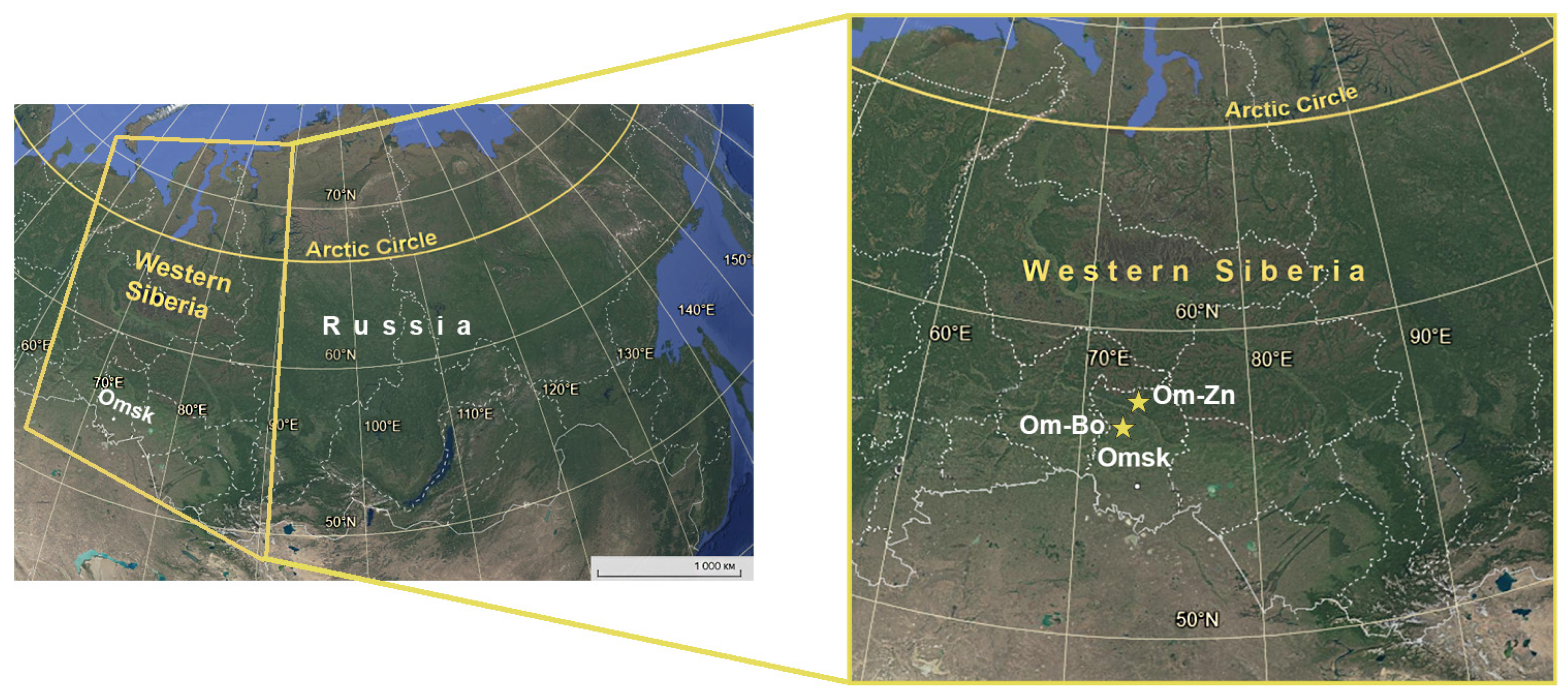

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Borrelia Cultivation

2.3. DNA Extraction

2.4. Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. Detection, Genotyping, and Characterization of the ospA Gene

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.6. Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

3. Results

3.1. Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. Detection and Species Determination

3.2. Results of ospA Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wolcott, K.A.; Margos, G.; Fingerle, V.; Becker, N.S. Host association of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato: A review. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2021, 12, 101766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergamo, S.; Trevisan, G.; Ruscio, M.; Bonin, S. Borrelial Diseases Across Eurasia. Biology 2025, 14, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, P. Epidemiology of Lyme Disease. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 36, 495–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strle, F.; Maraspin, V.; Lotrič-Furlan, S.; Ogrinc, K.; Rojko, T.; Kastrin, A.; Strle, K.; Wormser, G.P.; Bogovič, P. Lower Frequency of Multiple Erythema Migrans Skin Lesions in Lyme Reinfections, Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.R.; Strle, F.; Wormser, G.P. Comparison of Lyme Disease in the United States and Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 2017–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strle, F.; Nadelman, R.B.; Cimperman, J.; Nowakowski, J.; Picken, R.N.; Schwartz, I.; Maraspin, V.; Aguero-Rosenfeld, M.E.; Varde, S.; Lotric-Furlan, S.; et al. Comparison of culture-confirmed erythema migrans caused by Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto in New York State and by Borrelia afzelii in Slovenia. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999, 130, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strle, F.; Ružić-Sabljić, E.; Logar, M.; Maraspin, V.; Lotrič-Furlan, S.; Cimperman, J.; Ogrinc, K.; Stupica, D.; Nadelman, R.B.; Nowakowski, J.; et al. Comparison of erythema migrans caused by Borrelia burgdorferi and Borrelia garinii. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011, 11, 1253–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strnad, M.; Hönig, V.; Růžek, D.; Grubhoffer, L.; Rego, R.O.M. Europe-Wide Meta-Analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi Sensu Lato Prevalence in Questing Ixodes ricinus Ticks. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e00609-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomenko, N.V.; Livanova, N.N.; Romanova, E.V.; Karavaeva, I.I.; Panov, V.V.; Chernousova, N.I. Detection of DNA of borrelia circulating in Novosibirsk region. J. Microbiol. Epidemiol. Immunobiol. 2006, 7, 22–28. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Rar, V.; Livanova, N.; Tkachev, S.; Kaverina, G.; Tikunov, A.; Sabitova, Y.; Igolkina, Y.; Panov, V.; Livanov, S.; Fomenko, N.; et al. Detection and genetic characterization of a wide range of infectious agents in Ixodes pavlovskyi ticks in Western Siberia, Russia. Parasit. Vectors 2017, 10, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabitova, Y.; Fomenko, N.; Tikunov, A.; Stronin, O.; Khasnatinov, M.; Abmed, D.; Danchinova, G.; Golovljova, I.; Tikunova, N. Multilocus sequence analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato isolates from Western Siberia, Russia and Northern Mongolia. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018, 62, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabitova, Y.; Rar, V.; Tikunov, A.; Yakimenko, V.; Korallo-Vinarskaya, N.; Livanova, N.; Tikunova, N. Detection and genetic characterization of a putative novel Borrelia genospecies in Ixodes apronophorus/Ixodes persulcatus/Ixodes trianguliceps sympatric areas in Western Siberia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2023, 14, 102075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhacheva, T.A.; Kovalev, S.Y. Borrelia spirochetes in Russia: Genospecies differentiation by real-time PCR. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014, 5, 722–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korenberg, E.I.; Kovalevskii, Y.V.; Gorelova, N.B.; Nefedova, V.V. Comparative analysis of the roles of Ixodes persulcatus and I. trianguliceps ticks in natural foci of ixodid tick-borne borrelioses in the Middle Urals, Russia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2015, 6, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margos, G.; Gatewood, A.G.; Aanensen, D.M.; Hanincová, K.; Terekhova, D.; Vollmer, S.A.; Cornet, M.; Piesman, J.; Donaghy, M.; Bormane, A.; et al. MLST of housekeeping genes captures geographic population structure and suggests a European origin of Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 24, 8730–8735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Will, G.; Jauris-Heipke, S.; Schwab, E.; Busch, U.; Rössler, D.; Soutschek, E.; Wilske, B.; Preac-Mursic, V. Sequence analysis of ospA genes shows homogeneity within Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto and Borrelia afzelii strains but reveals major subgroups within the Borrelia garinii species. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 1995, 184, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, T.J. Borrelia outer membrane surface proteins and transmission through the tick. J. Exp. Med. 2004, 199, 603–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallich, R.; Jahraus, O.; Stehle, T.; Tran, T.T.; Brenner, C.; Hofmann, H.; Gern, L.; Simon, M.M. Artificial-infection protocols allow immunodetection of novel Borrelia burgdorferi antigens suitable as vaccine candidates against Lyme disease. Eur. J. Immunol. 2003, 33, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilske, B.; Preac-Mursic, V.; Göbel, U.B.; Graf, B.; Jauris, S.; Soutschek, E.; Schwab, E.; Zumstein, G. An OspA serotyping system for Borrelia burgdorferi based on reactivity with monoclonal antibodies and OspA sequence analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1993, 31, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilske, B.; Busch, U.; Fingerle, V.; Jauris-Heipke, S.; Preac Mursic, V.; Rössler, D.; Will, G. Immunological and molecular variability of OspA and OspC. Implications for Borrelia vaccine development. Infection 1996, 24, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.T.; Li, Z.; Nunez, L.D.; Katzel, D.; Perrin, B.S., Jr.; Raghuraman, V.; Rajyaguru, U.; Llamera, K.E.; Andrew, L.; Anderson, A.S.; et al. Development of a sequence-based in silico OspA typing method for Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Microb. Genom. 2024, 10, 001252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.M.; Norris, D.E. Genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto in Peromyscus leucopus, the primary reservoir of Lyme disease in a region of endemicity in southern Maryland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 5331–5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ćakić, S.; Veinović, G.; Cerar, T.; Mihaljica, D.; Sukara, R.; Ružić-Sabljić, E.; Tomanović, S. Diversity of Lyme borreliosis spirochetes isolated from ticks in Serbia. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2019, 33, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryffel, K.; Péter, O.; Dayer, E.; Bretz, A.G.; Godfroid, E. OspA heterogeneity of Borrelia valaisiana confirmed by phenotypic and genotypic analyses. BMC Infect. Dis. 2003, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mediannikov, O.Y.; Ivanov, L.; Zdanovskaya, N.; Vorobyova, R.; Sidelnikov, Y.; Fournier, P.E.; Tarasevich, I.; Raoult, D. Diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Russian Far East. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005, 49, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colunga-Salas, P.; Hernández-Canchola, G.; Sánchez-Montes, S.; Lozano-Sardaneta, Y.N.; Becker, I. Genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto: Novel strains from Mexican wild rodents. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 1263–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomenko, N.V.; Stronin, O.V.; Khasnatinov, M.N.; Danchinova, G.A.; Bataa, J.; Gol’tsova, N.A. Heterogeneity of the ospA gene structure from isolates of Borrelia garinii and Borrelia afzelii from Western Siberia and Mongolia. Mol. Genet. Microbiol. Virol. 2009, 24, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippova, N.A. Fauna of the USSR. In Arachnida, New Ser. 4: Ixodid Ticks of the Subfamily Ixodinae; Nauka: Leningrad, Russia, 1977; 396p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Rar, V.; Yakimenko, V.; Tikunov, A.; Vinarskaya, N.; Tancev, A.; Babkin, I.; Epikhina, T.; Tikunova, N. Genetic and morphological characterization of Ixodes apronophorus from Western Siberia, Russia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2020, 11, 101284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonechnikov, K.; Golosova, O.; Fursov, M. UGENE team. Unipro UGENE: A unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1166–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Rar, V.; Yakimenko, V.; Igolkina, Y.; Sabitova, Y.; Fedorets, V.; Karimov, A.; Rubtsov, G.; Epikhina, T.; Tikunova, N. The first study of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato persistence in small mammals captured in the Ixodes persulcatus distribution area in Western Siberia. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, U.; de Silva, A.M.; Montgomery, R.R.; Fish, D.; Anguita, J.; Anderson, J.F.; Lobet, Y.; Fikrig, E. Attachment of Borrelia burgdorferi within Ixodes scapularis mediated by outer surface protein A. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 106, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trezel, P.; Guérin, M.; Da Ponte, H.; Maffucci, I.; Octave, S.; Avalle, B.; Padiolleau-Lefèvre, S. Borrelia surface proteins: New horizons in Lyme disease diagnosis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 109, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, D.; Hornok, S. Checklist of hosts, illustrated geographical range and ecology of tick species from the genus Ixodes (Acari, Ixodidae) in Russia and other post-Soviet countries. Zookeys 2024, 1201, 255–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sándor, A. Ixodes apronophorus Schulze, 1924. In Ticks of Europe and North Africa; Estrada-Peña, A., Mihalca, A., Petney, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 179–181. [Google Scholar]

- Margos, G.; Fingerle, V.; Reynolds, S. Borrelia bavariensis: Vector Switch, Niche Invasion, and Geographical Spread of a Tick-Borne Bacterial Parasite. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollins, R.E.; Sato, K.; Nakao, M.; Tawfeeq, M.T.; Herrera-Mesías, F.; Pereira, R.J.; Kovalev, S.; Margos, G.; Fingerle, V.; Kawabata, H.; et al. Out of Asia? Expansion of Eurasian Lyme borreliosis causing genospecies display unique evolutionary trajectories. Mol. Ecol. 2023, 32, 786–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Locus | Organism | Reaction | Primer Name | Primer Sequences 5′-3′ | T # (°C) | Size (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS2 | Ixodes spp. | Multiplex | dITS29 | ccttcccgtggcttcgtctgt | 60 | [29] | |

| ITS2 | I. persulcatus | IP_rev | ctgtacatccgtccatttaggc | 412–413 | |||

| ITS2 | I. trianguliceps | IT_rev | cggcaatcgaacgacgt | 222 | |||

| ITS2 | I. apronophorus | IA_rev | tggcgaagatcatttgagttg | 706–709 | |||

| IGS | B. burgdorferi s.l. | Primary | NC1 | cctgttatcattccgaacacag | 50 | 350–384 | [10] |

| NC2 | tactccattcggtaatcttggg | ||||||

| Nested | NC3 | tactgcgagttcgcgggag | 50 | 237–271 | |||

| NC4 | cctaggcattcaccatagac | ||||||

| “Ca. B. sibirica” | Nested | Bsib | ataaaacattctaaaaaaatgaaca | 50 | 172 | This study | |

| NC4 | cctaggcattcaccatagac | [10] | |||||

| clpA | B. burgdorferi s.l. | Primary | clpAF1237 | aaagatagatttcttccagac | 50 | 982 | [15] |

| clpAR2218 | gaatttcatctattaaaagctttc | ||||||

| Nested | clpAF1255 | gacaaagcttttgatattttag | 50 | 850 | |||

| clpAR2104 | caaaaaaaacatcaaattttctatctc | ||||||

| p83/100 | B. burgdorferi s.l. | Primary | F7 | ttcaaagggatactgttagagag | 50 | 438–528 | [10] |

| F10 | aagaaggcttatctaatggtgatg | ||||||

| Nested | F5 | acctggtgatgtaagttctcc | 54 | 336–426 | |||

| F12 | ctaacctcattgttgttagactt | ||||||

| ospA | B. burgdorferi s.l. | Primary | pA3 | ctatttgttatttgttaatcttatac | 48 | 935–944 | [27] |

| pA4 | gcaaatcctagtaaatattgtttc | ||||||

| Nested | ospA91F | aaaaggagaatatattatgaaaa | 48 | 855–862 | This study | ||

| ospA924R | tattktttcataaattctcctt | ||||||

| ospA | B. burgdorferi s.l. | Sequencing | ospA561F * | ccggaaaagctaaagaagtt | This study | ||

| ospA561R * | aacttctttagcttttccgg |

| Site | Sampling Period | Source of Isolation | No. of Ticks | No. (%) of Ticks Containing Bbsl DNA | Results of Bbsl Species Determination | Samples Used for ospA Genotyping | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B.a | B.bav | Ca.B.sib | Mixed | B.a | B.bav | Ca.B.sib | |||||

| Om-Bo | June 2024 | I. persulcatus, flagging | 28 | 8 (28.6) | 2 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Om-Bo | May 2025 | I. persulcatus, flagging | 95 | 24 (25.3) | 8 | 9 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 0 |

| Om-Zn | September 2024 | Ixodes spp, from rodents, molted: | 90 | 28 (31.1) | 5 | 20 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 0 |

| I. apronophorus | 8 | 3 (37.5) | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | ||

| I. trianguliceps | 14 | 2 (14.3) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | ||

| I. persulcatus | 68 | 23 (33.8) | 5 | 15 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Om-Bo | September 2024 | Ixodes spp, from rodents, molted: | 69 | 41 (59.4) | 11 | 13 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| I. persulcatus | 69 | 41 (59.4) | 11 | 13 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Om-Bo | June 2025 | Ixodes spp, from rodents, molted: | 102 | 58 (56.8) | 4 | 41 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| I. apronophorus | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| I. trianguliceps | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| I. persulcatus | 95 | 57 (60.0) | 4 | 40 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Om-Bo | June 2016 | Ixodes spp. from rodents: | 44 | 5 (11.4) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| I. apronophorus | 10 | 5 (50.0) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | ||

| I. trianguliceps | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| I. persulcatus | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Isolate | Site | Source of Isolation | Results of Borrelia Genotyping by | Cluster by ospA Gene | GenBank Accession No. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| clpA | ospA | |||||

| Om16-76_Iapr | Om-Bo | I.apr, F; from A. agrarius | Ca.B.sib | Ca.B.sib | new | PX461036 |

| Om16-61_Iapr | Om-Bo | I.apr, N; from C. glareolus | Ca.B.sib | Ca.B.sib | new | PX461037 |

| Om16-101/2-Ipr * | Om-Bo | I.pers, N; from C. glareolus | Ca.B.sib | Ca.B.sib | new | PX461038 |

| Om16-103-Iapr * | Om-Bo | I.apr, F; from Ar. amphibious | Ca.B.sib | Ca.B.sib | new | PX461040 |

| Om16-75-Iapr * | Om-Bo | I.apr, N; from C. glareolus | Ca.B.sib | Ca.B.sib | new | |

| Om16-79/2-Iapr * | Om-Bo | I.apr; F; from M. oeconomus | Ca.B.sib | Ca.B.sib | new | |

| Om16-101/1-Ipr * | Om-Bo | I.pers, L; from C. glareolus | Ca.B.sib | Ca.B.sib | new | |

| Om16-132/2-Ipr * | Om-Bo | I.pers, L; from C. glareolus | Ca.B.sib | Ca.B.sib | new | |

| Om16-132/4-Ipr * | Om-Bo | I.pers, L; from C. glareolus | Ca.B.sib | Ca.B.sib | new | |

| Om16-132/5-Ipr * | Om-Bo | I.pers, L; from C. glareolus | Ca.B.sib | Ca.B.sib | new | |

| Om16-132/7-Ipr * | Om-Bo | I pers, L; from C. glareolus | Ca.B.sib | Ca.B.sib | new | |

| Om16-147_Iapr | Om-Bo | I.apr, F; from Ar. amphibious | Ca.B.sib | Ca.B.sib | new | |

| Om24-105_Sorex ** | Om-Zn | Sorex araneus, blood | Ca.B.sib | Ca.B.sib | new | PX461039 |

| Om25-93_Ipr | Om-Bo | I.pers, F; flag | B.bav | B.bav | IST9 | PX461045 |

| Om24-Zn1_Ipr | Om-Zn | I.pers, L molted into N; from C. rutilus | B.bav | B.bav | IST9 | PX461043 |

| Om24-Zn10_Iapr | Om-Zn | I.apr, L molted into N; from C. rutilus | B.bav | B.bav | IST9 | PX461044 |

| Om24-Zn37_Iapr | Om-Zn | I.apr, L molted into N; from C. rutilus | B.bav | B.bav | IST9 | PX513326 |

| Om24-Zn43_Itr | Om-Zn | I.tr, L molted into N; from C. rutilus | B.bav | mixed | n.d. | |

| Om25-23_Itr | Om-Bo | I.tr, L molted into N; from M. oeconomys | B.bav | B.bav | IST9 | PX461042 |

| Om25-50_Ipr | Om-Bo | I.pers, L molted into N; from A. agrarius | B.bav | B.bav | IST9 | PX461041 |

| Om25-64_Ipr | Om-Bo | I.pers, L molted into N; from C. rutilus | B.bav | mixed | n.d. | |

| Om25 34_Ipr | Om-Bo | I.pers, F; flag | B.bav | mixed | n.d. | |

| Om25 51_Ipr | Om-Bo | I.pers, M; flag | B.bav | B.bav | IST10 | PX513323 |

| Om25-10_Ipr | Om-Bo | I.pers, F; flag | B.bav | B.bav | IST10 | PX513321 |

| Om25-44_Ipr | Om-Bo | I.pers, F; flag | B.bav | B.bav | IST9 | PX513320 |

| Om25-73_Ipr | Om-Bo | I.pers, F; flag | B.bav | mixed | n.d. | |

| Om24-Zn_25_Itr | Om-Zn | I.tr, L molted into N; from C. rutilus | B.bav | B.bav | IST9 | PX513318 |

| Om24-45_Ipr | Om-Bo | I.pers, M; flag | B.bav | B.bav | IST10 | PX513319 |

| Om24-25_Ipr | Om-Bo | I.pers, L molted into N; from C. rutilus | B.bav | B.bav | IST10 | PX513322 |

| Om24-Zn23_Ipr | Om-Zn | I.pers, L molted into N; from C. rutilus | B. afzelii | B. afzelii | IST2 | PX461046 |

| Om24-Zn32_Ipr | Om-Zn | I.pers, L molted into N; from C. rutilus | B. afzelii | B. afzelii | IST2 | PX461047 |

| Om24-Zn45_Ipr | Om-Zn | I.pers, L molted into N; from C rutilus | B. afzelii | B. afzelii | IST2 | PX461048 |

| Om24-Zn88_Ipr | Om-Zn | I.pers, L molted into N; from C. rutilus | B. afzelii | B. afzelii | IST2 | PX461049 |

| Om25-82_Ipr | Om-Bo | I.pers, M; flag | B. afzelii | B. afzelii | IST2 | PX461050 |

| Om25-95_Ipr | Om-Bo | I.pers, F; flag | B. afzelii | B. afzelii | IST2 | PX513324 |

| Nov25-72_Ipav | Nov | I.pavl; F; flag | B. garinii | B. garinii | IST5 | PX513325 |

| Species, Strain | Serotype/IST | % Identity |

|---|---|---|

| B. afzelii, VS461 (Z29087) | 2 | 85.4 |

| B. bavariensis, PBi (CP000015) | 4 | 88.7 |

| B. bavariensis BgVir (CP003202) | 9 | 87.9 |

| B. bavariensis FujiP2 (NZ_JACGTX010000003) | 10 | 84.8 |

| B. burgdorferi, B31 (AE000790) | 1 | 86.4 |

| B. garinii, 20047 (CP028862) | 3 | 84.0 |

| B. garinii, PBr (CP001308) | 3 | 84.0 |

| B. garinii, PMe (PubMLST 2738) | 5 | 87.2 |

| B. garinii, PHez (PubMLST 2736) | 6 | 86.5 |

| B. garinii, PBes (CP119347) | 7 | 83.0 |

| B. garinii, PKi (PubMLST 2737) | 8 | 85.8 |

| B. garinii, HT59 (PubMLST 2728) | 11 | 85.0 |

| B. garinii, J-21 (PubMLST 2729) | 12 | 86.8 |

| B. mayonii MN14-1420 (NZ_CP015795) | 14 | 87.6 |

| B. spielmanii A14S (CP001469) | 13 | 86.8 |

| B. turdi Ya501 (AB016975) | 16 | 85.9 |

| B. valaisiana, VS116 (CP001433) | 15 | 81.5 |

| B. yangtzensis Okinawa-CW62 (PubMLST 2758) | 17 | 87.1 |

| “Candidatus B. sibirica” | B. afzelii, IST2 | B. bavariensis, IST9 | B. bavariensis, IST10 | All B. bavariensis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of isolates | 13 | 24 | 13 | 10 | 23 |

| Size (bp) | 819 | 822 | 822 | 822 | 822 |

| No. of haplotypes | 2 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 11 |

| No. of polymorphic sites | 2 | 6 | 37 | 37 | 150 |

| Nucleotide diversity, π ± S.D. | 0.0004 ± 0.0003 | 0.0015 ± 0.0002 | 0.0150 ± 0.0015 | 0.0244 ± 0.0031 | 0.0785 ± 0.0056 |

| Haplotype diversity, Hd ± S.D. | 0.154 ± 0.126 | 0.7500 ± 0.073 | 0.872 ± 0.067 | 0.733 ± 0.120 | 0.913 ± 0.033 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Igolkina, Y.; Rar, V.; Yakimenko, V.; Bardasheva, A.; Fedorets, V.; Karimov, A.; Rubtsov, G.; Epikhina, T.; Tikunova, N. Genetic Diversity of Siberian Isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi Sensu Lato by the ospA Gene. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2825. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122825

Igolkina Y, Rar V, Yakimenko V, Bardasheva A, Fedorets V, Karimov A, Rubtsov G, Epikhina T, Tikunova N. Genetic Diversity of Siberian Isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi Sensu Lato by the ospA Gene. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2825. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122825

Chicago/Turabian StyleIgolkina, Yana, Vera Rar, Valeriy Yakimenko, Alevtina Bardasheva, Valeria Fedorets, Alfrid Karimov, Gavril Rubtsov, Tamara Epikhina, and Nina Tikunova. 2025. "Genetic Diversity of Siberian Isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi Sensu Lato by the ospA Gene" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2825. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122825

APA StyleIgolkina, Y., Rar, V., Yakimenko, V., Bardasheva, A., Fedorets, V., Karimov, A., Rubtsov, G., Epikhina, T., & Tikunova, N. (2025). Genetic Diversity of Siberian Isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi Sensu Lato by the ospA Gene. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2825. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122825