Abstract

The study presents the design and simulation of a pneumatic drive unit intended for energy-efficient vehicle propulsion. The research focuses on developing a MATLAB 23.2/Simulink-based model that accurately represents the dynamic behavior of double-acting pneumatic actuators, including the interaction between pressure, force, torque transmission, and wheel rotation. The model integrates pneumatic circuit parameters with mechanical drivetrain components, allowing a comprehensive evaluation of system performance and compressed-air consumption. The simulation architecture is fully modular and parameterized, enabling rapid reconfiguration for different drive layouts and operating conditions. Results demonstrate that the proposed model provides a realistic representation of the physical processes in pneumatic systems, offering valuable insights for optimizing actuator control, gear ratios, and energy management strategies. Identified challenges include computational complexity and sensitivity to manually defined parameters, which highlight opportunities for further refinement. The developed model serves as a practical design and analysis tool for future engineers engaged in the development of sustainable pneumatic propulsion systems and educational simulations. Future work will address adaptive control algorithms, improved visualization using multibody dynamics, and optimization of air consumption under varying load conditions.

1. Introduction

The growing emphasis on sustainable and energy-efficient technologies has renewed interest in pneumatic actuation systems, particularly in applications where environmental compatibility, reliability, and simplicity are key requirements. Compressed-air-driven mechanisms are widely used in automation, robotics, and experimental vehicles due to their cleanliness, fast response, and robustness. However, the main limitation of pneumatic systems remains their relatively low energy efficiency and high air consumption, which significantly affect both operational costs and system performance. For this reason, developing simulation-based design tools that enable the optimization of pneumatic drives has become increasingly important for both academia and industry [1,2,3].

In recent years, several research and educational projects have explored air-powered propulsion concepts, such as the Aventics Pneumobile competition, which encourages innovative approaches to pneumatic mobility. Previous studies have mostly concentrated on the mechanical design, kinematic analysis, and construction of pneumatic engines. These works have provided valuable insights into structural configuration and force transmission, yet they often lack comprehensive models that capture the dynamic interaction between pneumatic components, control valves, and mechanical subsystems. As a result, designers have limited access to predictive tools that can evaluate system performance, energy consumption, and the influence of design parameters prior to prototype manufacturing [4,5,6,7].

Despite the growing interest in pneumatic actuation, there is still a lack of parameter-driven simulation environments capable of linking pneumatic circuit dynamics with mechanical power transmission in real time. Addressing this gap requires a modeling framework that not only replicates real physical behavior but also allows for modularity, reusability, and future system extensions. Such an approach would support research into efficiency optimization, control logic design, and virtual prototyping of pneumatic propulsion systems [4,7,8,9].

Recent advances in pneumatic system modeling have significantly improved the accuracy and reliability of simulation-based design tools. Experimental studies on the dynamic behavior of pneumatic components have shown that modern modeling platforms can faithfully reproduce pressure evolution, flow characteristics, and transient force generation across a wide range of operating conditions. Standardized procedures for defining flow-rate parameters have further strengthened the consistency of model inputs, allowing designers to more precisely evaluate valve performance and compressed-air consumption. Research on pneumatic line dynamics also highlights the relevance of propagation delays, nonlinear losses, and the influence of tubing configuration, all of which are critical factors when predicting system response in energy-efficient drive architectures [10,11,12,13,14,15,16].

In parallel, progress in the modeling of pneumatic propulsion systems and industrial actuators has demonstrated the value of integrating pneumatic subsystems with mechanical drivetrain components into unified simulation environments. Such approaches enable comprehensive analysis of torque transmission, actuator loading, and overall system efficiency before prototype development. Complementary work on virtual pneumatic simulators, fault-oriented modeling, and specialized pneumatic elements illustrates the potential of advanced simulation tools to support both engineering education and practical design tasks. Collectively, these developments emphasize the importance of modular, parameter-driven simulation frameworks that can adapt to diverse applications and provide meaningful insights for optimizing pneumatic actuation strategies [16,17,18].

The present work aims to design and validate a modular MATLAB/Simulink model that simulates the behavior of a pneumatic drive unit integrated into an air-powered vehicle. The model reproduces the actual pneumatic circuit of an experimental motor developed at the Technical University of Košice and includes double-acting linear actuators, 4/3 directional control valves, and a gear transmission mechanism. By coupling the pneumatic and mechanical domains, the simulation captures key operational parameters such as pressure, force, torque, rotational speed, and compressed-air consumption during simulated motion. Reference data from experimental configurations and established models were used to ensure physical accuracy and numerical stability [1,2,3,4,6,7,8,9,19,20,21].

The novelty of this study lies in the development of a fully parametric and extendable simulation framework, which allows users to modify geometrical and pneumatic parameters, test control strategies, and analyze system efficiency under varying operating conditions. The model provides a reliable and cost-effective foundation for evaluating pneumatic systems without the need for complex experimental setups. The findings presented herein contribute to the advancement of energy-efficient pneumatic propulsion and serve as a methodological reference for future research in the field of mechatronic system design [1,2,3,6,7,8,9].

2. Materials and Methods

This section describes the computational tools, modeling approach, and analytical procedures used for the design, simulation, and evaluation of the pneumatic propulsion unit developed as part of the Aventics Pneumobile project.

2.1. Conceptual Background and Analytical Foundations

The theoretical principles of fluid mechanics and machine design form the fundamental basis of the present study. The analysis focuses primarily on the dynamics of reciprocating motion, the thermodynamic behavior of compressed air, and the application of Bernoulli’s equation to model the pressure–flow relationship within pneumatic systems. These concepts are essential for understanding how compressed air can be effectively converted into mechanical work while minimizing energy losses. Special attention was given to the flow and consumption of compressed air through connecting components, control valves, and pneumatic cylinders, as well as to identifying potential sources of throttling and leakage that reduce overall efficiency [1,2,3].

The methodological framework also incorporates the theoretical comparison between pneumatic and internal combustion engines. Although pneumatic drives differ in their working medium and thermodynamic processes, they share common kinematic structures based on piston–crank or rack-and-pinion mechanisms that convert linear motion into rotation. The study leverages this analogy to analyze how the configuration of cylinders, their sequence of operation, and the mechanical transmission layout influence torque output, smoothness of motion, and energy consumption [3,5,6].

The resulting analytical synthesis provides a solid foundation for further model-based optimization. It establishes the governing equations and assumptions later implemented in the MATLAB/Simulink environment to enable simulation of the pneumatic propulsion system under dynamic conditions, serving as a reproducible basis for the design and refinement of energy-efficient pneumatic drives [8,9].

2.2. Selection and Structural Analysis of the Pneumatic Drive Concept

Several conceptual configurations of pneumatic engines were analyzed with respect to their applicability in energy-efficient vehicular propulsion systems. The comparative study included various cylinder arrangements and kinematic linkages, ranging from single-acting piston drives to multi-cylinder systems with different mechanical transmissions. Based on this evaluation, the design implemented in the Air Force TUKE Pneumobile 2019 project was selected as the reference configuration for further simulation and optimization. This system, designed and constructed at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Technical University of Košice, represents a robust and well-documented platform for analytical and simulation-based verification [6].

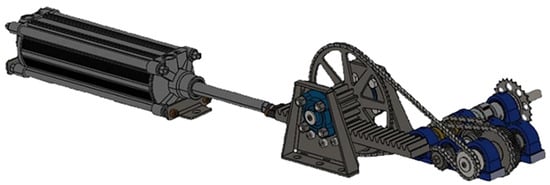

The selected concept employs two double-acting pneumatic cylinders from the company EMERSON|AVENTICS, Eger, Hungary, with a bore diameter of 100 mm and a stroke length of 320 mm. The piston rods are equipped with a rack mechanism engaging a gear train that converts the reciprocating motion of the pistons into continuous unidirectional rotation of the output shaft as shown in Figure 1 [6].

Figure 1.

A 3D model of the actuator and transformation mechanism of the Air TUKE Pneumobile.

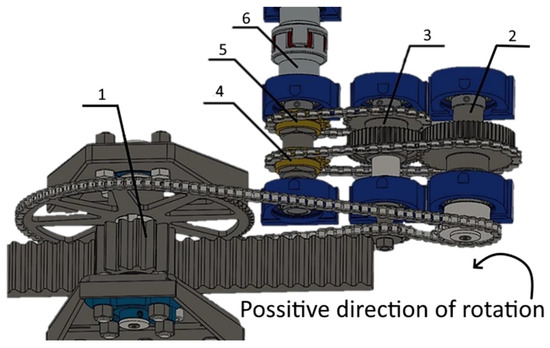

The transformation of the piston’s reciprocating motion into a unidirectional rotational output is shown in Figure 2. and operates as follows: During the extension stroke, the gear and chain wheels (1) rotate in the positive direction, and this rotational motion is transmitted through a chain to shaft (2). The motion is further transferred by another chain to the freewheel coupling (4), which drives the output shaft (6). Simultaneously, the rotation from shaft (2) is transmitted via a gear pair to shaft (3), which rotates in the opposite direction. The chain from shaft (3) drives the freewheel coupling (5), which freely rotates on shaft (6) in the negative direction and does not affect its motion. During the retraction stroke, the rotation directions of shafts and freewheel couplings are reversed. The torque is then transmitted in the positive direction to the output shaft (6) through coupling (5), while coupling (4) rotates freely. In this manner, a constant positive torque is maintained on the output shaft throughout the entire operating cycle of the pneumatic drive [6].

Figure 2.

Diagram of the transformation mechanism.

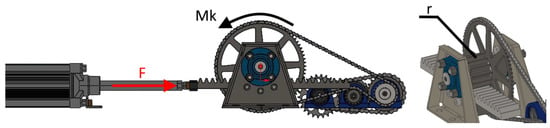

From the following schematic, as shown in Figure 3, the output force of the piston can be expressed, which serves as the basis for determining the torque acting on the gear and chain wheel (1), where

Figure 3.

Diagram of force distribution.

F—maximum force generated by the pneumatic actuator [N];

r = 35 mm … pitch circle radius [mm];

Mk—torque acting on the gear and chain wheel (1) [Nm].

The maximum piston force F can be expressed by the following relation:

where the symbols denote the following:

F—maximum force of the pneumatic actuator [N];

dpiston = 100 mm—piston diameter of the actuator;

pmax = 1 MPa—maximum air pressure allowed by the competition rules.

Using this relation, the torque on the gear and chain wheel (1) can be determined:

This value applies to a single set of the rack mechanism. When both actuators operate simultaneously and the gear ratios are adjusted accordingly, the maximum output torque at the shaft (6) and its gearing is as follows:

Although this configuration provides acceptable output performance, it requires precise synchronization and occupies a relatively large volume within the vehicle’s frame—a factor considered in the optimization and simulation stages of this work. For modeling purposes, the original pneumatic circuit was divided into functional subsystems: (1) the main pressure vessel equipped with a safety and pressure regulation system, and (2) the auxiliary air reservoir supplying two nearly identical actuation circuits. Each actuation circuit (3) consisted of a double-acting pneumatic cylinder operated by a 5/2 directional control valve. The two circuits were designed to operate in alternating phases, ensuring continuous torque generation on the output shaft. Each subsystem was subsequently analyzed in terms of flow capacity, pressure losses, and relative cross-sectional ratios to establish consistent input parameters for the numerical simulation and subsequent optimization [6].

2.3. Analytical Preprocessing and Parameter Estimation

Before constructing the simulation model, a detailed analytical preprocessing stage was conducted to determine the geometric and flow parameters of the pneumatic system. Since the available technical documentation did not contain all the required input data, several parameters—such as hose cross-sections, valve flow coefficients, and connection diameters—were approximated based on standard component specifications and previous Pneumobile designs [1,2,3].

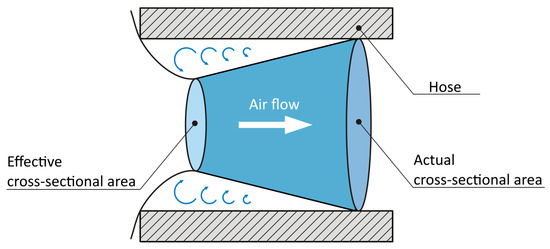

The key objective of this stage was to quantify the effective flow capacity of each subsystem through the concept of the effective cross-section ratio, defined as the ratio between the actual and reference flow areas (Figure 4). Specific numerical values were obtained from the component datasheets, and their cumulative sum was expressed as the limiting internal diameter of the pneumatic line, following the condition

Figure 4.

Flow ratios through the hose.

The calculation procedure followed fundamental fluid mechanics relations, applying Bernoulli’s equation and continuity principles to estimate pressure drops and air consumption along the circuit. The resulting equivalent cross-sectional ratios were used to represent relative flow capacities of each subsystem in the model. These ratios were subsequently implemented as variable coefficients within Simscape Fluid blocks to maintain proportional accuracy while allowing parametric adjustments.

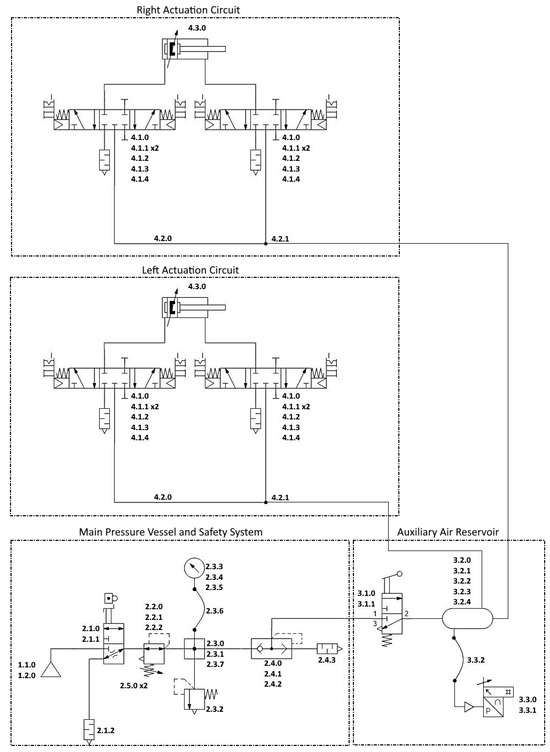

Based on the derived flow parameters and effective cross-section ratios, the complete pneumatic system was schematically represented to illustrate the interconnection of its functional units. The resulting circuit was divided into three principal subsystems: the main pressure vessel and safety regulation stage, the auxiliary air reservoir, and the actuator circuits controlling the double-acting cylinders. Since both actuation branches were identical in configuration, only one representative subsystem is described in detail in the following figures and analytical derivations [6].

2.3.1. Main Pressure Vessel and Safety System

The pneumatic circuit shown in Figure 5. begins with the primary pressure vessel (1.1.0) of 10 L capacity, filled with compressed nitrogen at a nominal pressure of 20 MPa. Nitrogen was selected as the working medium due to its ready availability and physical properties closely matching those of air. The vessel pressure is reduced to an operating level of 1 MPa by a pressure-reducing valve (1.2.0), ensuring that all downstream components can operate efficiently within their rated pressure limits.

Figure 5.

Pneumatic circuit diagram of the pneumobile engine.

Following the regulator, the medium passes through the safety system, which consists of multiple protection elements identified in the schematic and summarized in Table 1. As these components form a compact assembly, their combined flow resistance can be represented by a single equivalent flow cross-section. For the purposes of analytical modeling, this equivalent cross-section was treated as a constant parameter rather than a variable, since the safety assembly remains static throughout all operational states.

Table 1.

List of components forming the main pressure vessel and safety circuit.

Nominal flow rates of the individual components were obtained from manufacturer datasheets and subsequently converted into a dimensionless relative cross-sectional ratio according to the relation

where S represents the effective cross-sectional area, and Qn denotes the nominal volumetric flow rate. These parameters served as the baseline for determining the cumulative flow capacity of the pressure vessel subsystem.

Thus, the relative cross-sectional area of the pressure vessel and safety system was determined by substituting the values of the serially connected components listed in Table 1. into the Equation (7).

2.3.2. Auxiliary Air Reservoir

This section of the circuit begins with a ball valve (3.1.0) positioned upstream of the auxiliary air reservoir (3.2.0) with a total capacity of 25 L. The reservoir serves to compensate for flow fluctuations within the system and functions as a junction between individual circuit branches. For this reason, although compressed nitrogen flows through it, the reservoir itself can be considered a passive consumer element, and its nominal flow rate and corresponding relative cross-sectional area are not included in subsequent flow calculations. A digital manometer (3.3.0) is connected to a dedicated outlet of the reservoir. It continuously monitors and displays the internal pressure while simultaneously transmitting the measured data to the control unit. Based on these readings, the control system can adjust the motor operation in the event of a significant pressure drop. The remaining outlets of the reservoir supply the pneumatic circuits of the right and left linear actuators. The nominal flow values for each connection, as listed in Table 2, were substituted into Equation (6) to determine the relative cross-sectional ratios of the components associated with the reservoir subsystem.

Table 2.

List of components forming the auxiliary air reservoir.

The recalculated relative cross-sectional areas of the serially connected components were substituted into Equation (5) to determine the overall relative cross-section of the air reservoir circuit.

2.3.3. Actuation Circuit

The double-acting actuators (4.3.0) feature pistons with a diameter of 100 mm and a stroke length of 320 mm. Each actuator port is controlled by an individual 5/3 directional valve (4.1.0), which is modified according to the schematic to function as a 3/3 valve by sealing two of its outlets with threaded plugs (4.1.1). This configuration enables independent control of both sides of the actuator, allowing the nitrogen supply to be interrupted at a specific stroke phase while the actuator completes its motion using the residual pressure.

The valves are mounted directly onto the actuator ports, minimizing the dead volume of nitrogen that would otherwise perform no useful work. The piston position is continuously monitored by an analog linear sensor along the full stroke length.

All pneumatic lines, except for the blind branches leading to pressure gauges, are made of plastic tubing with an outer diameter of 12 mm and an inner diameter of 9 mm. Since the configurations of the left and right actuator circuits are nearly identical, their relative cross-sectional ratios are equivalent, differing only in the fitting dimensions at the air reservoir outlets. The left actuator connection uses a 3/8″ thread for a Ø12 mm hose (3.2.3), while the right actuator employs a 1/2″ thread for a Ø12 mm hose (3.2.1).

Although these fittings are listed in the Table 3, they are also included in the actuator circuit calculations, as they represent the distribution nodes supplying nitrogen to both parallel branches. The nominal flow rates of all relevant components were taken from the manufacturer’s specifications and converted to the corresponding relative cross-sectional ratios using Equation (6).

Table 3.

List of components forming the actuation circuit.

The total relative cross-sectional area for the left (S3) and right (S4) branches is expressed using Equation (5).

After recalculating the relative cross-sectional areas for all subcircuits, their combination yields the overall equivalent cross-section of the entire Pneumobile aggregate. For maximum accuracy, the total cross-section must also include the contribution of the hoses that distribute compressed nitrogen throughout the circuit. According to the technical literature, a Table 4. provides cross-sectional values as a function of hose diameters and lengths, from which the corresponding values were obtained for hoses with lengths of 4 × 0.5 m, 1 × 1.5 m, and 2 × 1 m.

Table 4.

Relative cross-sectional area for pneumatic hoses.

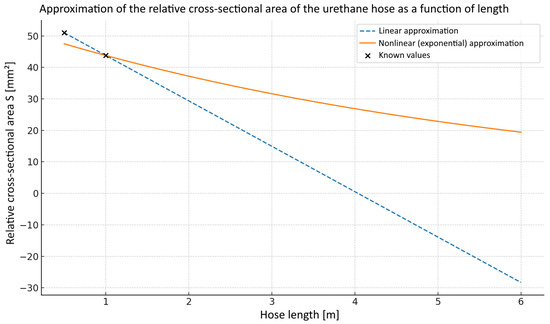

The cross-sectional area is specified for polyurethane pneumatic tubing with an outer diameter of 12 mm and an inner diameter of 9 mm. Values were given for hose lengths of 0.5 m and 1 m; by approximating these known data, the relative cross-sectional area for a length of 1.5 m was determined to be 38.5 mm2. This value was obtained from the reference graph correlating hose length with flow capacity Figure 6. Due to the limited number of reference points, the resulting fit should be understood as an approximate relationship used primarily to preserve parameter continuity in the subsequent flow modelling. Although additional intermediate measurements were not available, the assumed linear trend is consistent with empirical behaviour of pneumatic hoses documented in the literature. Nevertheless, the restricted dataset may introduce a minor deviation in the predicted distributed resistance, which is acknowledged as a limitation of the present analysis.

Figure 6.

Graph of the relative cross-sectional area approximation as a function of length.

Finally, all calculated values were substituted into Equation (5) to determine the total relative cross-sectional area of the Pneumobile pneumatic circuit.

2.3.4. Parameter Estimation by ISO 6358

The previous sections described airflow modelling based on Bernoulli’s equation together with the relative flow parameters S and Qn provided by component manufacturers. Although Bernoulli’s formulation offers a convenient first-order approximation of pressure losses, its accuracy becomes limited when applied to pneumatic systems with strong throttling, turbulent flow development, and transitions into choked flow. These nonlinear regimes are common in pneumatic valves, orifices, and coupling interfaces, and cannot be captured reliably by classical incompressible flow theory [10,11].

To obtain a more physically consistent representation of the flow behaviour, the ISO 6358 standard [11] introduces two key parameters:

Sonic conductance (C)—characterizing the mass flow rate in the choked (sonic) regime,

Critical pressure ratio (b)—defining the boundary between subcritical and critical flow conditions.

Since manufacturers rarely provide C and b directly, it was necessary to estimate them indirectly. The available nominal data Qn and S served as the basis for this approximation. The sonic conductance C was estimated from the nominal flow rate using the relation

where Qn denotes the nominal flow rate (converted to L/s), and P1 represents the reference upstream pressure (0.6 MPa) specified for the component.

The critical pressure ratio b was assigned based on the expected behaviour of sharp-edged orifices and pneumatic fittings, for which

This is generally representative and consistent with published ISO 6358 [11] valve characteristics. Using these relations, the ISO 6358 [11] parameters C and b were estimated for all relevant flow-restricting components in the system. The resulting values are summarized in the Table 5.

Table 5.

List of components forming the pneumatic system by ISO 6358.

The analytical evaluation of the pneumatic circuit provided a complete and dimensionally consistent parameter set describing the flow behaviour of all subsystems. Initially, the relative cross-sectional area obtained from manufacturer data and nominal flow rate Qn enabled uniform characterization of geometric restrictions in the circuit. However, because Bernoulli-based formulations offer only a limited representation of compressible and potentially choked flow regimes, these quantities were subsequently used as a foundation for estimating the ISO 6358 [11] flow parameters.

By approximating the sonic conductance C and critical pressure ratio b from the available nominal data, each flow-restricting component was assigned a more physically representative nonlinear flow model. This refinement allowed the transition from simplified incompressible flow assumptions to a standardized compressible-flow description consistent with pneumatic industrial practice.

The combined parameter set—relative area S, nominal flow-based estimates, and ISO 6358 conductance parameters C and b ensured that all simulated flow paths exhibited realistic pressure losses, subsonic/sonic transitions, and time-dependent mass-flow dynamics. This preprocessing stage established a robust foundation for the subsequent numerical modelling in MATLAB Simulink, where the validated parameters were implemented to construct, calibrate, and reliably simulate the virtual Pneumobile drive unit [11].

2.4. Simulation Model Development

The analytical evaluation from the previous section provided the basis for creating a parametric simulation model of the Pneumobile pneumatic drive. The purpose of the simulation was to verify the theoretical assumptions, analyze the dynamic response of the system, and evaluate how individual subsystems influence overall performance under various operating conditions. Using the results of analytical preprocessing, all geometric and flow parameters were implemented in a virtual environment to ensure that the simulated model reflects realistic physical behavior. The pneumatic motor model was developed in MATLAB using its Simulink extension, which enables block-diagram modeling for dynamic system simulation. Additional toolboxes—Simscape and Simscape Fluids—were required, providing the library blocks used to construct the pneumatic circuit. The model was divided into four parts, corresponding to the pneumatic schematic shown in Figure 5. The modeling process began with the main pressure vessel and safety system, followed by the auxiliary air reservoir, pneumatic actuator subsystem, and control logic for actuator operation [8,9,12,13,14,15,16,17].

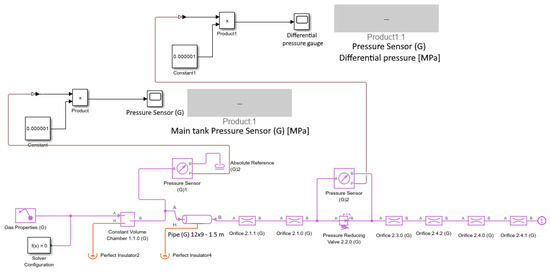

2.4.1. Main Pressure Vessel and Safety System Model

The first subsystem of the simulation model as show in Figure 7. represents the main pressure vessel and the associated safety circuit, corresponding to the initial section of the pneumatic layout described earlier. The modeled 10 L constant-volume chamber stores compressed nitrogen at an initial pressure of 20 MPa. The pressure is subsequently reduced to approximately 0.6 MPa by a pressure-reducing valve, ensuring safe and stable operation of the downstream pneumatic components. The safety assembly was modeled as a sequence of restrictive elements—valves and fittings—whose flow characteristics were expressed through relative cross-sectional ratios derived from catalog data. Since these components form a fixed series connection, their combined flow capacity was treated as a constant parameter in the model, maintaining consistency with the analytical evaluation from Section 2.3.

Figure 7.

Circuit diagram of the main pressure vessel and safety system.

The implemented functional blocks of this subsystem can be summarized as follows:

- Gas Properties (G)—Defines the gas type and thermodynamic parameters.

- Solver Configuration—Specifies the computational parameters for the simulation.

- Constant Volume Chamber 1.1.0 (G)—Represents the 10 L main pressure vessel.

- Perfect Insulator—Models thermal isolation of the chamber.

- Pressure Sensor (G)—Measures absolute and differential pressure values [MPa].

- Absolute Reference (G)—Establishes the zero-pressure reference.

- Orifice (G)—Represents the flow restrictions corresponding to relative cross-sections of the safety components.

- Pressure Reducing Valve (G)—Simulates pressure regulation from 20 MPa to 0.6 MPa.

- Pipe (G)—Models the connecting pneumatic line.

- Constant—Mathematical constant input.

- Product—Mathematical multiplication block.

- Scope—Displays graphical plots of signal outputs.

- Display—Shows numerical signal values during simulation.

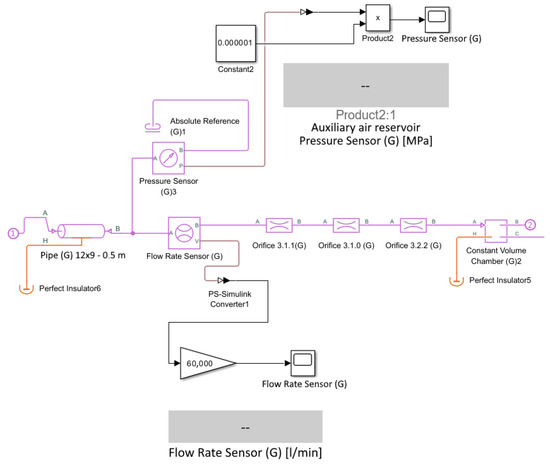

2.4.2. Auxiliary Air Reservoir Model

In the simulation model, the auxiliary air reservoir subsystem was constructed to represent the dynamic pressure behavior downstream of the reduction stage. Its primary purpose within the Simulink environment is to observe and validate pressure stabilization and flow transients under different actuation loads. The model captures the interaction between the constant-volume chamber, connecting tubing, and flow restrictions defined by the calculated relative cross-sections from the analytical preprocessing stage. During the simulation, this part of the model provides measurable outputs for reduced pressure and volumetric flow rate, enabling verification of the overall system response and comparison with expected analytical results.

The implemented functional blocks of this subsystem, shown in Figure 8, include

- Pipe (G)—Models the pneumatic connection between the reducer outlet and the actuation circuit.

- Perfect Insulator—Defines thermally insulated boundaries for adiabatic behavior.

- Pressure Sensor (G)—Measures the reduced static pressure in the reservoir [MPa].

- Flow Rate Sensor (G)—Measures the volumetric flow rate at the outlet [L/min].

- Orifice (G)—Represents flow restrictions corresponding to equivalent relative cross-sectional areas.

- Constant Volume Chamber (G)2—Simulates the 24 L auxiliary reservoir as a pressure buffer element.

- Absolute Reference (G)—Sets the zero-pressure reference point.

- Constant—Provides a fixed input value for signal operations.

- Product—Performs multiplication of signal inputs.

- Scope—Displays real-time plots of simulation signals.

- Display—Outputs numerical signal values for monitoring.

- Gain—Multiplies the signal by an internal constant to adjust measurement scaling.

Figure 8.

Circuit diagram of the auxiliary air system.

2.4.3. Actuation Circuit Model

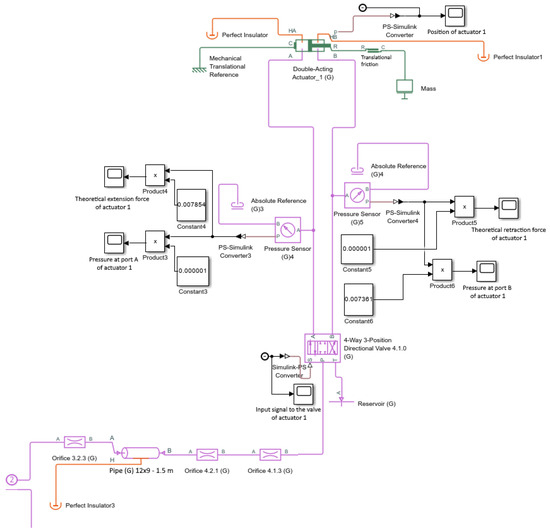

The modeling process continued with the development of the actuator circuit. The configurations of both pneumatic actuators are nearly identical, differing only in the cross-sectional area of the air outlet from the auxiliary reservoir and in the initial displacement settings of the pistons. To simulate alternating operation, Actuator 1 was initialized at 0 mm and Actuator 2 at 320 mm. Pressure sensors were placed between the ports A and B of the valve and the actuator chambers to measure the instantaneous pressure values used for calculating the extension and retraction forces. These pressure signals were also visualized in real time using the Scope blocks for monitoring dynamic behavior during the simulation.

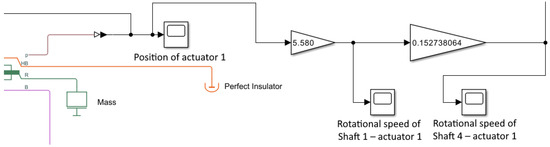

Figure 9 shows the structure of the actuator subsystem, which consists of the following Simscape Fluids and Simulink blocks:

Figure 9.

Circuit diagram of the actuator.

- Orifice (G)—Represents the relative flow areas of the connecting components with identical codes

- Pipe (G)—Pneumatic hose elements connecting the valve and actuator

- Perfect Insulator—Thermal isolation element closing the heat exchange port

- 4-Way 3-Position Directional Valve (G)—Valve controlling the extension and retraction of the actuator

- Reservoir (G)—Infinite-volume block representing the atmosphere

- Pressure Sensor (G)—Measures pressure between the valve and actuator [MPa]

- Absolute Reference (G)—Zero-pressure reference node

- Constant—Mathematical constant block

- Product—Multiplication block

- Scope—Visualization of simulated signals and pressure curves

- Mechanical Translation Reference—Mechanical grounding for the actuator casing (port C)

- Mass—Represents the load on the piston rod (rack + rod mass) connected to port R

- Double-Acting Actuator (G)—Pneumatic double-acting cylinder used for the main propulsion

- Translational Friction—Mechanical block that represents basic friction and dynamic loss

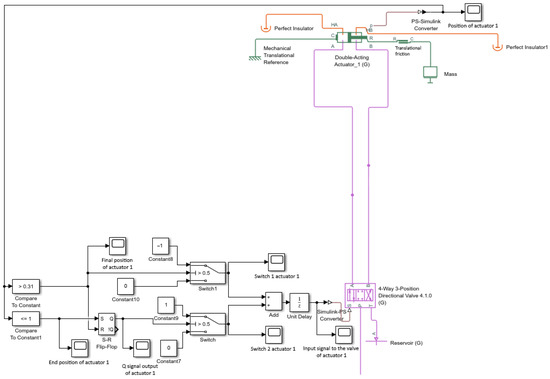

2.4.4. Control Logic Model

The final part of the simulation model represents the control logic governing the 4/3 directional control valve. This valve block contains four pneumatic ports (P, A, B, and T) and two flow paths: P–A with A–T, and P–B with B–T. The valve remains in the central neutral position at rest. A control signal is applied through input port S. When the signal value equals 1, the valve opens flow paths P–A and B–T, and when the signal equals –1, the paths P–B and A–T are activated.

The linear actuator provides a continuous output signal corresponding to its current piston position. The control logic compares this signal with predefined constants representing the end positions with a hysteresis margin. When a comparison condition is satisfied, the logical subsystem outputs 1 or −1, switching the valve accordingly.

The comparison output is further processed through a Set–Reset Flip-Flop block to maintain the stable state of the control signal, preventing oscillations caused by rapid switching. Finally, a Unit Delay block is implemented to introduce a small time offset in the feedback loop, effectively eliminating algebraic loop formation within the Simulink structure.

The blocks used in this subsystem (Figure 10) are as follows:

Figure 10.

Logic control circuit diagram for the valve.

- Compare To Constant—compares the input signal to a defined threshold; outputs logical 1 if the condition is met.

- Scope—visualizes the simulated signal response over time.

- S–R Flip Flop—provides memory for the control state (Set–Reset function).

- Constant—defines numerical constants used for logic comparison.

- Switch—routes one of multiple input values based on a logical condition.

- Add—combines or modifies signal inputs arithmetically.

- Unit Delay—holds the previous signal value to prevent algebraic loops.

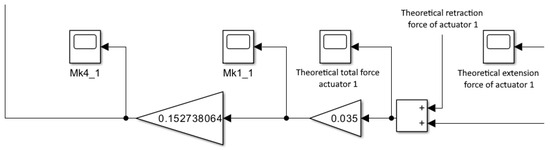

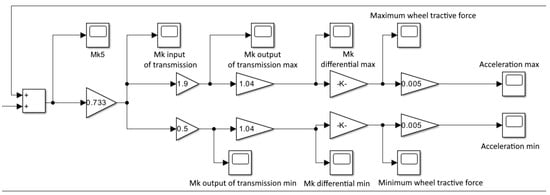

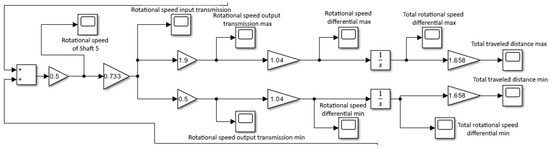

2.4.5. Drive Force and Torque Model

The final stage of model development focused on the calculation of the resulting mechanical output parameters—the drive torque, wheel traction force, acceleration, and the total distance traveled by the Pneumobile. These quantities were derived from the simulated forces acting on the piston rods of both actuators and subsequently transformed through the defined gear ratios and transmission elements of the drivetrain.

The computed extension and retraction forces were first combined and converted into an equivalent torque acting on the differential shaft, as illustrated in Figure 11. This torque served as the primary input for determining the tractive force applied to the drive wheels and the corresponding acceleration of the vehicle, as shown in Figure 12. Using the position feedback from both actuators, the angular velocity of the driving pinion on Shaft 1 was calculated (Figure 13), and by successive multiplication through all gear ratios, the final wheel rotational speed and the linear displacement of the vehicle were obtained (Figure 14).

Figure 11.

Circuit diagram for combining forces and torque.

Figure 12.

Circuit diagram for combining torques and calculating driving force and acceleration.

Figure 13.

Circuit diagram for rotational speed calculation.

Figure 14.

Circuit diagram for combining rotational speeds and calculating traveled distance.

Each sub-block of this part of the model was implemented using basic arithmetic and signal routing elements in Simulink, such as Product, Gain, Sum, and Scope blocks, which ensured a clear and traceable flow of the mechanical relationships between pneumatic power generation and the resulting vehicle motion.

3. Results

After assembling all functional subsystems, defining the parameters, and establishing interconnections between individual Simulink and Simscape blocks, several preliminary test simulations were carried out to verify the model’s stability and accuracy. The final simulation was performed for a total duration of 60 s, providing a comprehensive set of time-dependent responses that describe the behavior of the entire pneumatic system. From all obtained outputs, only the most representative results are presented and discussed below—systematically following the flow of energy through the model, from the main pressure vessel to the actuators and ultimately to the vehicle’s drivetrain.

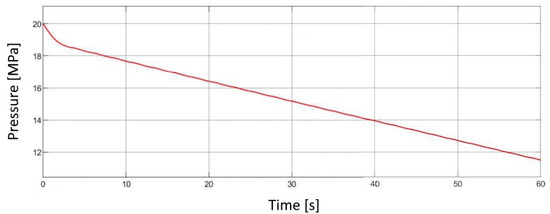

3.1. Pressure and Flow Characteristics

As shown in Figure 15, the pressure (20 MPa) in the main vessel decreases over time as the entire pneumatic circuit becomes filled with nitrogen and as the actuators subsequently consume the compressed gas during operation.

Figure 15.

Pressure in the main vessel over time.

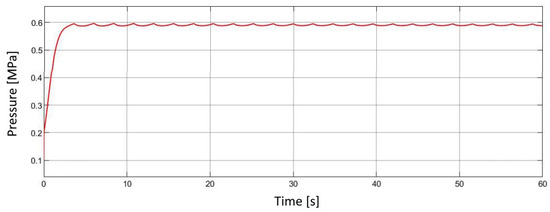

From Figure 16, it can be observed that the pressure behind the regulator gradually approaches its target value of 0.6 MPa, which the regulator continuously attempts to maintain at a stable level throughout the simulation.

Figure 16.

Pressure evolution downstream of the regulator over time.

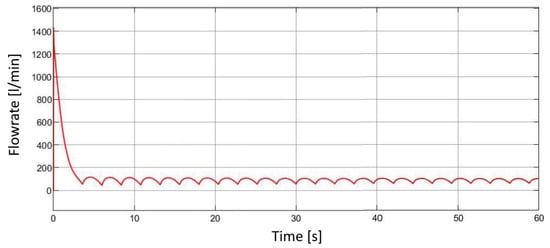

The flow rate characteristics, illustrated in Figure 17, show an initial sharp peak reaching approximately 100 L/min, representing the rapid pressurization of the pneumatic system at startup. After this transient phase, the flow rate gradually decreases and stabilizes at a steady level corresponding to the continuous nitrogen consumption by the actuators.

Figure 17.

Mass flow rate over time.

3.2. Actuator Control Signals and Position Response

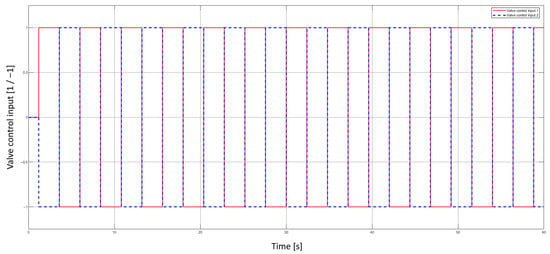

The subsequent stage of the analysis focused on the control inputs and motion response of both pneumatic actuators. Each actuator was operated by a solenoid valve receiving a discrete control signal that defined its extension or retraction phase. As illustrated in Figure 18, the input signals were set in a counter-phase operation—actuator 1 began at an initial position of 0 mm and extended upon receiving a signal value of +1, while actuator 2 started at 320 mm and retracted under a signal value of −1.

Figure 18.

Valves control signal input over time.

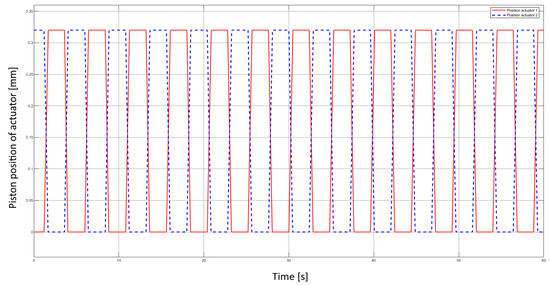

The resulting displacement of both actuators over time is shown in Figure 19. The motion profiles correspond directly to the control logic, demonstrating synchronized but opposite movements. This configuration reflects the physical setup of the drivetrain, where the opposing actuators alternately drive the transformation mechanism.

Figure 19.

Actuators piston position over time.

3.3. Performance and Output Parameters

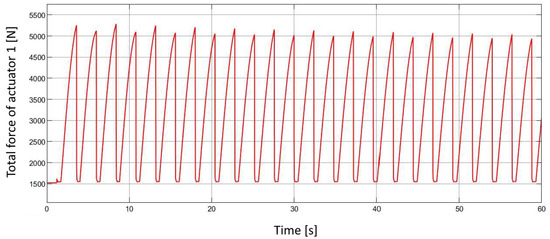

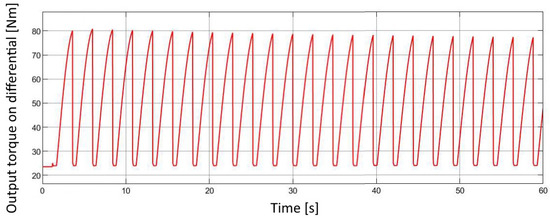

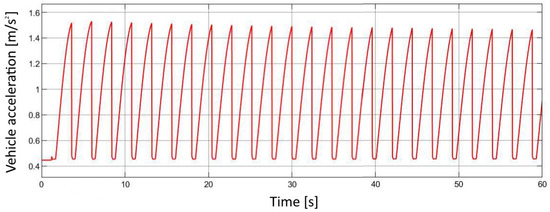

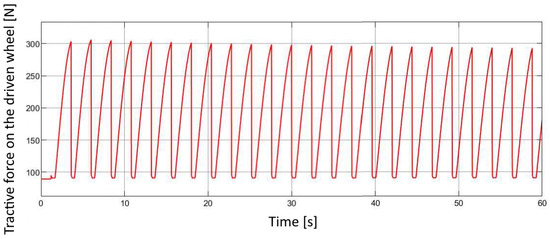

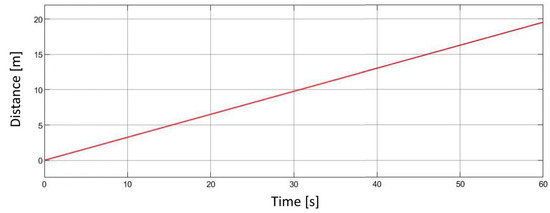

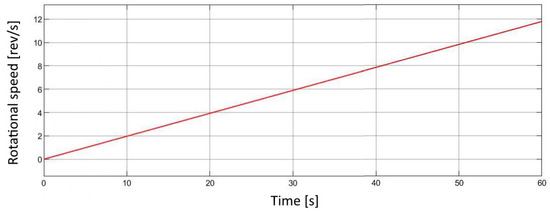

The final simulation results illustrate the overall dynamic performance of the pneumatic drive system and its mechanical interaction with the drivetrain. The plots present the total actuator forces during both extension and retraction strokes (Figure 20), which directly reflect the alternating pressure conditions within the actuator chambers. These forces were subsequently transformed through the system’s gear ratios to obtain the resulting torque acting on the differential shaft (Figure 21). The torque curve shows a characteristic oscillating pattern, corresponding to the cyclic operation of the two opposing actuators. From the calculated torque, the tractive force on the driven wheel (Figure 22) and the corresponding instantaneous and peak acceleration of the vehicle (Figure 23) were determined. These parameters describe the conversion efficiency of pneumatic energy into linear motion and provide a direct indication of the system’s ability to deliver stable propulsion. Furthermore, using the position output signals from both actuators, the rotational speeds of the intermediate shafts and the final differential output were computed (Figure 24). The gradual increase of rotational speed illustrates the transient phase of acceleration followed by a steady operating state. Integration of these rotational values yielded the total vehicle travel distance over the 60 s simulation period (Figure 25), demonstrating smooth motion without instability or undesired oscillations. Overall, these results confirm the correct functional coupling and energy transfer between the pneumatic, mechanical, and control subsystems of the developed model. The observed values and trends validate the consistency of the simulation setup and provide a solid foundation for further optimization of the Pneumobile’s performance.

Figure 20.

Total actuator forces over time.

Figure 21.

Torque on the differential shaft over time.

Figure 22.

Wheel traction forces over time.

Figure 23.

Vehicle acceleration over time.

Figure 24.

Rotational speed of the drivetrain over time.

Figure 25.

Total distance traveled over time.

The presented results confirm that the developed simulation model accurately reproduces the dynamic behavior of the Pneumobile’s pneumatic and mechanical systems under operating conditions. The obtained force, torque, and motion profiles form the basis for a more detailed discussion and evaluation of the system’s performance, efficiency, and potential optimization, which are addressed in the following section.

4. Discussion

The developed simulation model accurately reproduces the behavior of a pneumatic drive system used in a compressed-air-powered vehicle. Created in the MATLAB/Simulink environment, the model integrates the control of double-acting actuators via a 4/3 directional valve, the calculation of generated forces, the transmission of torque through the gear train, and the observation of the resulting torque on the drive shaft. Its primary purpose is to simulate the mechanical response and air consumption of the Pneumobile system in a physically realistic way, providing a foundation for further optimization of pneumatic drive efficiency and control strategies.

The modeling approach builds upon previous research conducted at the Department of Production Technology and Robotics (KVTaR), where pneumatic and bio-inspired actuation systems were experimentally analyzed and compared with conventional double-acting cylinders [4]. The results of these studies provided valuable input for understanding actuator dynamics and guided the simulation setup used in this work.

Furthermore, the use of MATLAB/Simulink and the Simscape–Multibody framework follows earlier investigations into their suitability for static and dynamic mechanical analyses [19,20,21]. Those studies demonstrated that, with appropriate parameter scaling and solver configuration, MATLAB-based simulations can achieve accuracy comparable to finite-element methods. The present model extends this methodology to the pneumatic domain by coupling mechanical and fluid subsystems within a single computational architecture.

Comparable modeling strategies have also been applied in pneumatic and soft-robotic research using Simscape Fluids, where system accuracy was verified against experimental data with discrepancies below 10%. The consistency of results obtained in this study confirms that the implemented approach can effectively replicate the real physical behavior of pneumatic propulsion systems while maintaining numerical stability.

Overall, the simulation framework presented here establishes a robust and extendable platform for analyzing and optimizing pneumatic propulsion systems. The obtained insights into the relationship between pneumatic power, torque transmission, and vehicle motion form the basis for the final conclusions and proposed research directions discussed in the following section.

4.1. Strengths and Advantages of the Model

One of the main strengths of the proposed model lies in its high level of physical fidelity. The calculated actuator forces are based on the actual parameters of the pneumatic components, taking into account the difference in efficiency between extension and retraction, operating pressure, and piston position. This ensures that the simulation results closely correspond to real operational behavior.

Another advantage is the dynamic and self-contained control logic. The actuator motion is governed directly by piston position feedback and boundary switching of the valve, eliminating the need for external controllers. This design approach increases the model’s robustness and autonomy while maintaining functional simplicity.

The model also provides precise tracking of transmitted torque and rotational speed throughout the drivetrain. Force transmission is calculated using real gear tooth counts and pitch diameters, which allows for accurate determination of torque at each stage of the mechanism and for estimating the total vehicle displacement.

Finally, due to its modular structure, the model is easily extendable. It can be adapted for different configurations—such as a modified number of cylinders, alternative gear ratios, or the addition of feedback control loops—making it suitable for future experimental validation or optimization tasks.

4.2. Limitations and Numerical Challenges

Despite its accuracy and robustness, the model faces several limitations. The detailed physical representation of pneumatic dynamics and control logic results in high computational demands. Simulations covering a few minutes of real time may require several hours of computation, depending on solver settings and hardware performance.

The occurrence of algebraic loops, particularly in feedback and logical switching elements (e.g., Simulink Switch blocks), can lead to numerical instability or solver convergence issues. These must be mitigated through appropriate delay elements or solver configuration.

Furthermore, the precision of the simulation is highly dependent on the accuracy of manually entered parameters—such as hose cross-sections, fitting losses, actuator properties, and gear ratios. Any deviation from real values may significantly affect the fidelity of the results.

Lastly, the current version of the model lacks a direct mechanical visualization of motion. While the numerical outputs are reliable, the addition of a Simscape Multibody representation would provide a clearer physical interpretation of the actuator and drivetrain behavior.

4.3. Future Improvements

Future development of the model may focus on several key enhancements. Implementing adaptive control strategies (e.g., PID-based valve regulation) could improve pressure utilization and dynamic response based on available supply pressure and current load.

Introducing simulations of variable driving scenarios—such as start-up, steady drive, or climbing—would enable a more comprehensive performance analysis.

An advanced air management subsystem could also be implemented to optimize the use of stored compressed air according to vehicle demand and route profile.

Finally, exporting simulation data directly to the MATLAB Workspace for post-processing, visualization, and efficiency optimization would allow for more detailed analytical studies and support the development of predictive control strategies.

Overall, the simulation framework presented in this study establishes a robust and extendable platform for analyzing and optimizing pneumatic propulsion systems. The obtained insights into the relationship between pneumatic power, torque transmission, and vehicle motion form the basis for the final conclusions and proposed research directions discussed in the following section.

5. Conclusions

The primary objective of this study was to design and assemble a detailed simulation model of a compressed-air-powered vehicle’s pneumatic drive using MATLAB and Simulink. Building upon previous research on pneumatic actuation and simulation-based modeling approaches, the presented model focused on reproducing key physical quantities such as piston position, generated force, transmitted torque, and wheel rotational speed in direct relation to the consumption of compressed nitrogen as the working medium.

Throughout the development, pneumatic subsystems were systematically integrated with mechanical drivetrain components, enabling a combined analysis of dynamic motion, power transmission, and energy consumption. The model was designed with modularity and physical accuracy as core principles while maintaining numerical stability and computational feasibility. Special attention was given to solver configuration, mitigation of algebraic loops, and proper parameterization of pneumatic elements to ensure reliable and repeatable simulation results.

The simulation successfully replicated the expected system behavior and enabled estimation of wheel rotational speed and total travel distance based on the available air supply, thus indirectly providing a prediction of the vehicle’s driving range. The main contribution of this work lies in the integration of pneumatic actuation, real mechanical parameters, and power output evaluation within a unified computational framework. This approach provides a solid foundation for future optimization of actuator performance, gear selection, and drivetrain design in compressed-air propulsion systems.

Beyond its research relevance, the developed model also demonstrates strong didactic potential. It can be effectively applied for educational and laboratory purposes, serving as a practical tool for understanding pneumatic drive dynamics, system interactions, and control strategies. Future work may focus on incorporating real system losses, feedback-based or adaptive control mechanisms, and Simscape Multibody visualization to capture the complete motion of the Pneumobile. These enhancements will further strengthen the model’s utility for performance evaluation and system-level optimization in pneumatic vehicle design and development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and J.B.; methodology, M.S. and R.J.; software, M.S.; validation, R.J.; data curation, J.M.; writing—review and editing, J.B.; visualization, J.B.; supervision, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Slovak Grant Agency—project VEGA 1/0294/24—Research and development of a multi-robotic system with distributed intelligence in the cloud and project 043TUKE-4/2024—Creating promising educational tools for the field of additive manufacturing with the implementation of progressive virtual reality elements.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hajduk, M.; Tuleja, P. Základy Pneumatických Mechanizmov I: Výroba, Úprava a Rozvod Stlačeného Vzduchu a Vákua; Technická Univerzita v Košiciach: Košice, Slovakia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hajduk, M.; Tuleja, P. Základy Pneumatických Mechanizmov II: Pneumatické Ventily; Technická Univerzita v Košiciach: Košice, Slovakia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rimár, M.; Šmeringai, P.; Fedák, M. Operational Characteristics of Experimental Actuator with a Drive Based on the Antagonistic Pneumatic Artificial Muscles. In Smart Technology Trends in Industrial and Business Management; Springer Innovations in Communication and Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuleja, P.; Jánoš, R.; Semjon, J.; Sukop, M.; Marcinko, P. Analysis of the Antagonistic Arrangement of Pneumatic Muscles Inspired by a Biological Model of the Human Arm. Actuators 2023, 12, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palko, M. Návrh Experimentálneho Vozidla Poháňaného Stlačeným Vzduchom. Bachelor’s Thesis, Technical University of Košice, Košice, Slovakia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Solárik, R. Návrh Motora Pre Pneumobil 2019. Bachelor’s Thesis, Technical University of Košice, Košice, Slovakia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brna, J. Návrh Pohonu Pneumobilu. Bachelor’s Thesis, Technical University of Košice, Košice, Slovakia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xavier, M.; Fleming, A.; Yong, Y.K. Modelling and Simulation of Pneumatic Sources for Soft Robotic Applications. In Proceedings of the IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics (AIM), Boston, MA, USA, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 916–921. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343466100_Modelling_and_Simulation_of_Pneumatic_Sources_for_Soft_Robotic_Applications (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- MathWorks.com. Pneumatic Actuation Circuit. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/simscape/ug/pneumatic-actuation-circuit.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Dvořák, L.; Fojtášek, K.; Dyrr, F. Experimental Verification of Pneumatic Elements Mathematical Models in MATLAB–Simulink–Simscape. MM Sci. J. 2023, 01, 6378–6385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6358-1:2013; Pneumatic Fluid Power—Determination of Flow-Rate Characteristics of Components—Part 1: General Rules and Test Methods for Steady-State Flow. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Nowakowski, M.; Kosiuczenko, K. Evaluation of TAERO UGV structural collision resistance using FEM analysis. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Tech. Sci. 2025, 73, e153431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, G.; Hristov, H.; Anchev, A.; Rachev, S. Modelling and Simulation of Dynamic Processes of Pneumatic Lines. Eng. Rural Dev. 2023, 3, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakács, T. A dynamic model of a pneumobile vehicle. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1935, 012016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakács, T. A MATLAB/Simulink® Dynamic Model of a Pneumatic Piston and System for Industrial Application. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Management of Technology and Information (ISMSIT), Istanbul, Turkey, 22–24 October 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairuddin Osman, N.; Zainuddin, N.; Kamal, A.H. Development of a New Virtual Pneumatic Control Simulator for Educational Purposes. Int. J. Res. Innov. Sci. Stud. 2025, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.G.; Zhang, X.J. Study on Fault Simulation for Pneumatic Actuator Model. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 706–708, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filo, G. Modelling of a Pneumatic Cushion in MATLAB-Simulink System. Czas. Tech. 2017, 2017, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, R.; Rosa, D.R.; Flores-Caballero, A.; Garrido, S. Deployment of Model-Based-Design-Adaptive Controllers for Monitoring and Control Mechatronic Devices. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, G. Study on Pressure Change Rate of the Automatic Pressure Regulating Valve in the Electronic-Controlled Pneumatic Braking System of Commercial Vehicle. Processes 2021, 9, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwin, P.; Gola, A.; Wójcik, Ł.; Cioch, M. Optimization of the Flow of Parts in the Process of Brake Caliper Regeneration Using the System Dynamics Method. Processes 2024, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.