Abstract

Shape Memory Alloy (SMA) actuators offer strong potential for compact, lightweight, silent, and compliant robotic grippers; however, their practical deployment is limited by the challenge of controlling nonlinear and hysteretic thermal dynamics. This paper presents a complete Sim-to-Real control framework for precise temperature regulation of a tendon-driven SMA gripper using Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL). A novel 12-action discrete control space is introduced, comprising 11 heating levels (0–100% PWM) and one active cooling action, enabling effective management of thermal inertia and environmental disturbances. The DRL agent is trained entirely in a calibrated thermo-mechanical simulation and deployed directly on physical hardware without real-world fine-tuning. Experimental results demonstrate accurate temperature tracking over a wide operating range (35–70 °C), achieving a mean steady-state error of approximately 0.26 °C below 50 °C and 0.41 °C at higher temperatures. Non-contact thermal imaging further confirms spatial temperature uniformity and the reliability of thermistor-based feedback. Finally, grasping experiments validate the practical effectiveness of the proposed controller, enabling reliable manipulation of delicate objects without crushing or slippage. These results demonstrate that the proposed DRL-based Sim-to-Real framework provides a robust and practical solution for high-precision SMA temperature control in soft robotic systems.

1. Introduction

Smart materials continue to push the boundaries of actuation technologies, enabling new abilities in robotics and advanced engineering systems. Among them, Shape Memory Alloys (SMAs), particularly Nickel–Titanium (NiTi) alloys, have attracted substantial interest due to their unique thermo-mechanical characteristics and their demonstrated effectiveness in compact actuation systems [1,2,3,4]. SMAs exhibit the Shape Memory Effect (SME), a reversible, solid-state phase transformation between Martensite and Austenite phases, allowing a deformed element to recover its predetermined shape upon heating [5,6,7,8]. This property, commonly activated through Joule heating, enables the creation of silent, lightweight, mechanically simple actuators with high power density—characteristics that make SMAs highly suitable for aerospace [9,10,11], biomedical devices [12,13], and soft robotics applications [14,15].

Despite their advantages, the deployment of SMAs in high-performance actuators is fundamentally limited by their complex nonlinear dynamics. SMA behavior is dominated by severe hysteresis in the temperature–strain relationship, strong path dependency, and significant thermal inertia, all of which introduce challenges for achieving precise and fast control [16,17]. Conventional linear controllers such as PID—which must be tuned around a fixed operating point—struggle under such nonlinear, state-dependent conditions, often resulting in overshoot, long settling times, and sensitivity to environmental disturbances or load variations. These challenges are particularly critical in SMA-actuated robotic grippers, where positional or force overshoot can damage delicate or variable-geometry objects, making high-precision thermal control essential [18,19].

Moreover, practical SMA-based grippers require not only rapid heating but also rapid cooling to enable bidirectional (closing–opening) operation. The introduction of forced convection cooling, however, adds another nonlinear and opposing dynamic, further complicating the control problem [2]. Previous studies have investigated advanced nonlinear solutions—including Sliding Mode Control (SMC) [20,21] and Fuzzy Logic Control (FLC) [22,23]—but model-based approaches depend heavily on the accuracy of mathematical models, while FLC performance is limited by human-derived rule sets that may not generalize well across operating conditions.

In response to these limitations, model-free intelligent control techniques such as Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) have been increasingly explored. DRL enables an agent to learn optimal control policies directly through interaction with the environment, without requiring an explicit analytical model of the system dynamics [24,25,26]. Among these methods, Deep Q-Learning (DQL) algorithm is particularly attractive because it combines discrete action selection with continuous state estimation using deep neural networks (DNN) [27,28]. However, standard DQL implementations typically rely on coarse, mutually exclusive thermal actions—such as full heating, full cooling, or off—resulting in limited finesse when managing SMA thermal inertia and difficulty mitigating overshoot.

This paper proposes a novel Deep Q-Network (DQN)-based control architecture featuring a fine-grained discrete action space tailored for high-precision SMA temperature regulation. Unlike most existing DRL-based thermal control approaches that adopt coarse action spaces with only binary (on/off) or ternary heating states (e.g., heating, holding, and cooling), the proposed method defines a substantially finer discrete action space. This increased action granularity enables smoother and more precise modulation of thermal input, which is essential for suppressing overshoot and ensuring stable operation in SMA-actuated robotic grippers. Specifically, we define twelve discrete actions comprising eleven granular heating levels (0–100% PWM) and a dedicated active cooling state. This design empowers the agent with precise control over the thermal input, enabling sophisticated switching policies—such as active damping or pre-emptive braking—to effectively suppress overshoot. Such capabilities are crucial for safe and reliable operation in SMA-actuated robotic grippers. To evaluate this approach, we develop a high-fidelity thermo-mechanical simulation environment modeling Joule heating, natural convection, and forced convection. We train the proposed 12-action DQN agent to demonstrate its autonomous control capabilities. The controller’s performance is rigorously assessed based on its ability to minimize steady-state error and maintain precise setpoint tracking. We specifically analyze the agent’s effectiveness in suppressing overshoot and ensuring stability under dynamic setpoint-tracking scenarios that reflect realistic gripper operation.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the mechanical design of the tendon-driven gripper, the thermo-mechanical modeling of the SMA actuator and formulates the reinforcement learning framework, including the proposed DQN architecture and discrete action design. Section 3 describes the experimental setup and reports the experimental results along with comparative analyses. Section 4 provides a discussion of the experimental findings, limitations, and insights gained from the Sim-to-Real implementation. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mechanical Design of the SMA Gripper

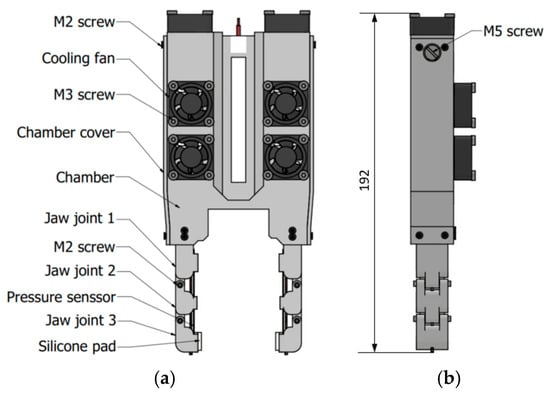

Figure 1 illustrates an overview of the proposed two-way SMA–actuated, tendon-driven gripper. The front view (Figure 1a), side view (Figure 1b), and top view (Figure 1c) highlight the compact mechanical layout and symmetric jaw geometry. Friction losses in the tendon routing are mitigated by the mechanical layout of the actuation system, as illustrated in Figure 1d. The SMA springs are arranged parallel to the tendon path, resulting in a short and nearly straight routing with minimal curvature. This configuration reduces friction-induced force losses and improves grip force transmission efficiency.

Figure 1.

Mechanical design of the two-jaw, tendon-driven gripper using 2-way SMA actuators: (a) front view, (b) side view, (c) top view, (d) cross-sectional view.

The SMA springs used in this study are near-equiatomic NiTi two-way memory springs supplied by NexMetal Co., Ltd., Incheon, Republic of Korea. They were pre-trained and shape-set by the manufacturer to provide stable two-way shape memory behavior and repeatable bidirectional actuation. According to the specifications, the springs have a wire diameter of 0.75 mm, an outer diameter of 6.5 mm, and a reversible length change from approximately 16 mm (heated) to 50 mm (cooled), making them suitable for compact tendon-driven gripper actuation.

The core of the design is the thermomechanical actuation system. The gripper employs two-way SMA springs, which contract during heating and autonomously re-extend during cooling. These springs are located in the chambers to maintain consistent thermal behavior and to minimize heat loss. A thermistor is mounted in close thermal contact with each spring to provide the real-time temperature feedback required for closed-loop control. To accelerate cooling, each SMA spring chamber features a forced-convection system comprising fourteen 3 mm × 15 mm longitudinal slots and two miniature axial fans (25 mm × 25 mm × 10 mm). The 81 mm slotted region ensures the SMA spring remains fully exposed to airflow throughout its 50 mm maximum stroke. Two lateral fans and one top-mounted fan generate multi-directional airflow, optimizing heat dissipation while maintaining thermal isolation and a compact form factor.

During the gripping (heating) phase, electrical current is supplied to the SMA springs via the connection between SMA electric wires and SMA springs, and Joule heating drives the phase transformation to austenite. The springs actively contract, pulling the tendon routed through the jaw linkage (Figure 1d). This tendon force generates a closing torque that enables the gripper to conform to and secure the target object. During the release (cooling) phase, the current is eliminated. Three integrated cooling fans for each chamber enhance forced-air convection, allowing the SMA temperature to decrease rapidly. Owing to the trained two-way effect, the springs automatically re-extend to their low-temperature shape. This relaxation releases the tendon tension and reopens the jaws due to the superelastic backbones (Nitinol wire). This reversible heating–cooling cycle, combined with the compact tendon-routing architecture shown in Figure 1d, produces a lightweight, fully compliant gripper capable of fast, repeatable, and robust actuation suitable for closed-loop temperature-based control.

2.2. Thermal Model and Simulation Environment

To facilitate a safe and efficient training process, we developed a high-fidelity simulation environment based on the fundamental principles of thermodynamics. The thermal behavior of the SMA spring is governed by the first law of thermodynamics, which can be expressed by the following heat transfer equation:

where Pout is further defined by Newton’s law of cooling as hA(T − Tamb). Substituting this into the primary equation yields the complete model used in our simulation:

The parameters for this model were derived from a combination of direct measurements, material datasheets, and empirical experiments. While the spring’s mass (m) and surface area (A) were measured physically and the specific heat capacity (c) was based on typical values for Nitinol alloys, the crucial heat transfer coefficient (h) required experimental determination.

To find, a steady-state thermal analysis was performed. At thermal equilibrium, the rate of temperature change is zero (), which simplifies Equation (1). By applying a constant input power () and measuring the resulting steady-state temperature (), can be calculated as:

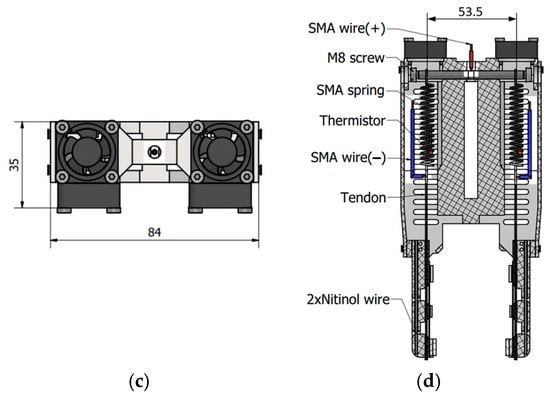

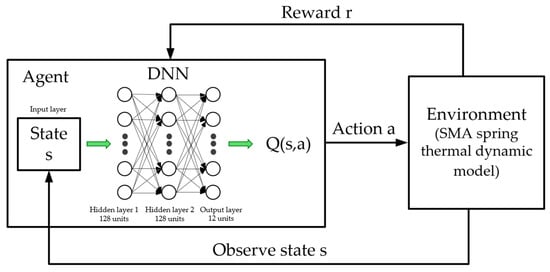

This experiment was conducted for both natural convection () with the fan off and forced convection () with the fan on. Incorporating these empirically derived values ensures that the simulation environment provides a valid and reliable basis for training the reinforcement learning agent before its deployment on the physical system. The results are compared in Figure 2. The plot clearly illustrates the significant impact of forced convection on the cooling rate. With the fan activated, the system’s temperature decreases more significantly, demonstrating a substantially higher heat transfer coefficient ().

Figure 2.

A comparison of the cooling rates under natural convection and forced convection.

2.3. Deep Q-Learning Controller Design

2.3.1. State and Action Space Definition

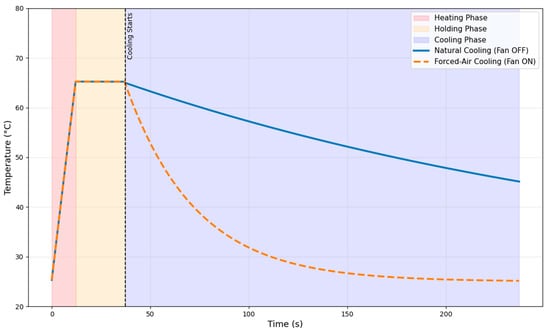

The action-value function Q(s, a) was approximated using a DQN, implemented in PyTorch 2.2.0 framework. As visualized in Figure 3, the architecture is a feed-forward neural network designed to map the environmental state to the expected return for each action.

Figure 3.

The DQN architecture, mapping the input state (error, error rate) to the output Q-values for each possible action.

The network’s input layer accepts the 2-dimensional state vector, st = [et, t], where

The error et in Equation (4) is the temperature error and t is the rate of change in that error. This is followed by two fully connected hidden layers, each containing 128 neurons. The Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) was used as the activation function for the hidden layers to introduce non-linearity, enabling the network to learn the complex dynamics of the thermal system. The output layer is a linear, fully connected layer with 12 neurons, where each neuron corresponds to the predicted Q-value for one of the 12 discrete actions in the action space. During inference, the action with the highest Q-value is selected as the optimal action for the given state.

The agent interacts with the environment by selecting an action from a discrete action space a, consisting of twelve distinct actions. This action space was designed to provide the agent with comprehensive control over the thermal dynamics of the SMA spring, encompassing multiple levels of heating (0–100%), active cooling by fan.

The mapping from the discrete action index selected by the agent to the corresponding physical actuation is detailed in Table 1. The eleven heating actions correspond to different duty cycles of a Pulse-Width Modulated (PWM) signal applied to the spring, which results in varying levels of Joule heating. The active cooling action engages a fan to increase the convective heat transfer coefficient.

Table 1.

The discrete action space of the DQN agent.

2.3.2. Reward Function Design

The design of the reward function is critical for shaping the agent’s behavior towards the desired control objectives. A multi-component reward function, R(st, at), was engineered to synergistically promote four key characteristics: rapid response, high precision without overshoot, goal achievement, and operational stability. The total reward at each time step t is the sum of these components:

The logic for each component is detailed below:

- Proportional Error Penalty (rerror): A continuous, shaped reward is provided to guide the agent towards the setpoint. This penalty is proportional to the square of the error et, encouraging aggressive action when far from the target and finer control when close.where β = 0.1

- Overshoot Penalty (rovershoot): To teach the agent to anticipate the system’s thermal inertia, a large, discrete penalty is applied if the temperature exceeds the setpoint by a small margin (1 °C). This severe punishment effectively discourages overshooting.

- Safety temperature zones (rsafety): To ensure the physical integrity of the SMA actuator and enforce a safe operational envelope, a high-priority safety constraint mechanism was implemented. We defined a valid operating temperature range between 25 °C and 80 °C.

- Goal Achievement Reward (rgoal): A large, positive reward is given when the agent successfully navigates the temperature into a narrow tolerance band (±0.5 °C) around the setpoint. This condition defines a successful outcome and terminates the episode.

- Action Switching Penalty (rswitching): To promote a smooth and stable control policy, a small penalty is proposed whenever the agent changes its action from the previous time step. This discourages inefficient and high-frequency oscillations (chattering) when the system is near a steady state. Also, it reduces the switching state of the fan, and does not make it turn on and turn off frequently.

- Fan activation (rcooling_action): A reward shaping strategy was employed to accelerate the learning process. Specifically, the agent was incentivized to explore the active cooling action. This was implemented by providing a small, discrete reward bonus +2 whenever the ‘FAN ON’ action (action 11) was executed, guiding the agent to discover its effectiveness in controlling the temperature and preventing overshoot.

2.3.3. Hyperparameter Selection

The performance of the DQN agent is highly dependent on the selection of its hyperparameters. These parameters, which define the network architecture and the learning algorithm’s behavior, were carefully chosen through empirical testing to achieve a balance between learning speed and policy stability. The key hyperparameters used for training the final model are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Training Hyperparameters.

2.3.4. Training in the Simulation Environment

To develop the control policy, the DQN agent was trained exclusively within the previously described high-fidelity simulation environment. This simulation-based approach was chosen for several key advantages over training directly on physical hardware. Firstly, it ensures safety and cost-effectiveness, as the agent can freely explore the action space and learn from failures without any risk of damaging the physical SMA actuator. Secondly, it enables accelerated training, allowing the agent to experience thousands of control scenarios in a fraction of the real-world time. The training process was structured into 500 episodes, with each episode lasting a maximum of 300 step times. At the beginning of each episode, the environment was reset with a new, randomly selected setpoint to ensure the agent learns a robust and generalizable policy.

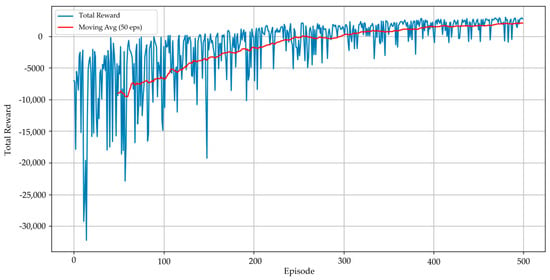

To balance the trade-off between exploration and exploitation, an epsilon-greedy strategy was employed. The exploration rate, epsilon (ϵ), was initialized at 0.9 to encourage broad exploration in the early stages of training. It was then exponentially decayed after each episode, gradually shifting the agent’s behavior towards exploiting its learned knowledge. The successful convergence of the training process is illustrated in Figure 4. The total reward per episode shows a clear upward trend and stabilizes at a high-reward value after approximately 500 episodes. This convergence indicates that the agent has successfully learned an effective policy for the temperature control task and is ready for performance evaluation.

Figure 4.

Total reward per episode during the training phase of 500 episodes.

2.3.5. Evaluation in Simulation

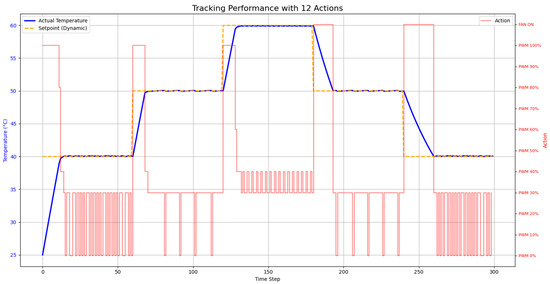

To assess the performance of the trained DQN agent, a rigorous evaluation was conducted using a dynamic setpoint tracking task. This task was designed to test the controller’s key performance metrics, including response speed, tracking accuracy, overshoot, and stability. The result of this evaluation is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Performance of the DQN controller in the dynamic setpoint tracking evaluation of 500 episodes.

The evaluation results demonstrate that the DQN agent learned a highly effective and sophisticated control policy. The analysis of the agent’s behavior reveals the successful emergence of several key characteristics of an advanced controller. Firstly, rapid and accurate tracking: The controller exhibits a fast response to changes in the setpoint. The actual temperature closely follows the target trajectory with minimal lag, indicating that the agent learned to apply maximum heating power (PWM 100) or active cooling (Fan ON) appropriately to induce rapid temperature changes.

- Overshoot Elimination via Anticipatory Control: A critical achievement of the learned policy is the near-complete elimination of temperature overshoot. As seen at each upward step in the setpoint, the agent intelligently deactivates the heater before reaching the target. This “braking” behavior shows that the agent successfully learned to account for the system’s thermal inertia, a sign of an advanced control strategy. This behavior was a direct result of the large, discrete penalty for overshooting in the reward function.

- High Stability and Smooth Control: The policy is remarkably stable once the setpoint is reached. The high-frequency oscillations or “chattering” observed in earlier training stages were successfully eliminated. The agent learned to maintain a steady temperature using low-power PWM actions, which is a direct consequence of the penalty for frequent action switching. This results in a smoother, more efficient, and more hardware-friendly control approach.

The combination of a well-designed reward function and the learning capacity of the DQN resulted in a controller that not only meets but exceeds the primary control objectives. The agent autonomously discovered advanced control strategies, demonstrating the high potential of deep reinforcement learning for complex, non-linear control tasks.

3. Experiments and Results

3.1. Deployment and Evaluation on Physical Hardware

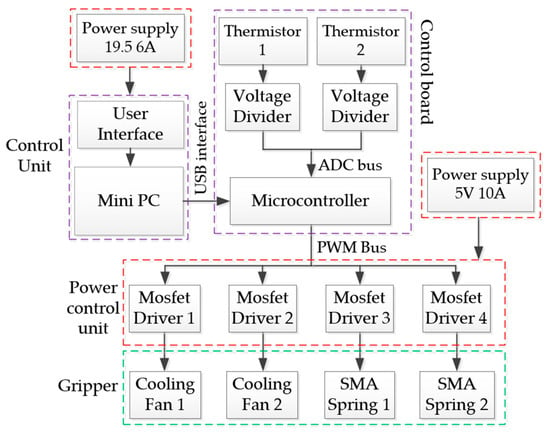

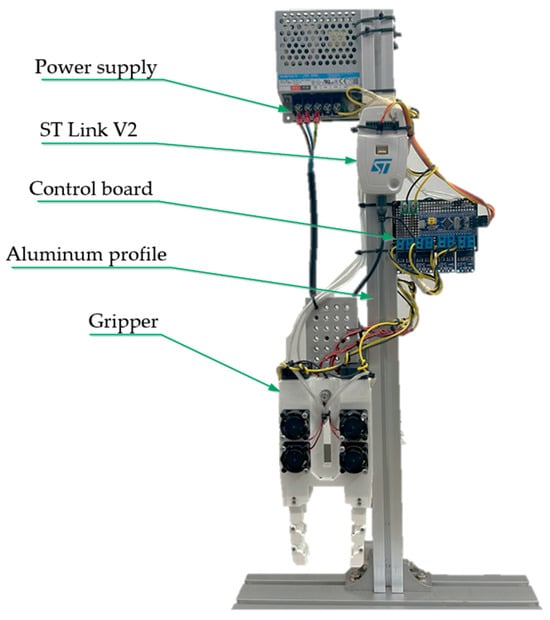

To evaluate the simulation results and assess the real-world viability of the trained DQN agent, a physical hardware system was proposed, as shown in Figure 6. This setup is designed to transfer the control policy from the simulation environment to a tangible system with minimal modifications, demonstrating a successful Sim-to-Real transition.

Figure 6.

Block diagram of the hardware system for real-world deployment and evaluation.

The system architecture employs a clear separation of duties. A Mini PC serves as the high-level controller, responsible for running the Python 3.10 environment (User interface), loading the trained PyTorch model, and executing the DQN agent’s decision-making logic. It receives temperature data and sends high-level action commands (integers 0–12) to a microcontroller (STM32F103C8T6) via a Universal Asynchronous Receiver/Transmitter (UART) communication via USB Communications Device Class (CDC). The microcontroller handles all low-level, real-time tasks. It converts the received action command into the appropriate electrical signal: a precise PWM signal for heating or a digital signal for the cooling fan. A Mosfet Driver (Model XY-MOS, Shenzhen Sungood Electronics Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) is used to safely amplify the microcontroller’s low-power PWM output to deliver the high current required for Joule heating of the SMA Spring. A thermistor, mounted in thermal contact with SMA spring, measures the real-time temperature. The analog signal from thermistor is read by the microcontroller’s Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC), processed, and sent back to the Mini PC (Model IT13, GEEKOM, Shenzhen, China), closing the control loop.

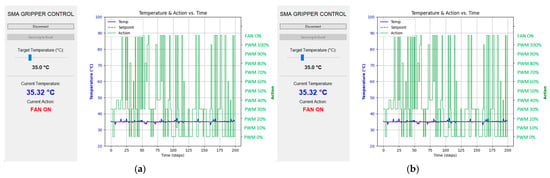

3.2. Temperature Control Evaluation

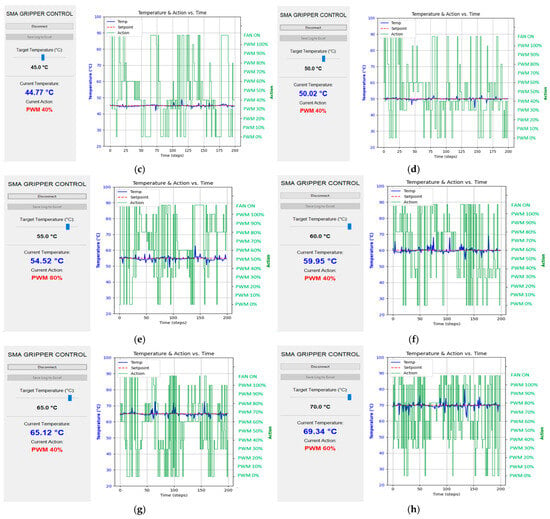

The steady-state tracking performance of the trained DQN controller was experimentally evaluated on the physical hardware over a wide operating range. Figure 7a–h present the controller’s performance when maintaining constant temperature setpoints from 35 °C to 70 °C. In each subfigure, the left vertical axis shows the temperature measured by the contact thermistor, while the right axis indicates the discrete control actions selected by the DQN agent. The controller exhibits rapid switching among zero-PWM states, multiple heating levels, and fan-assisted cooling, reflecting an active and adaptive policy that compensates for thermal inertia and environmental heat dissipation. To obtain reliable steady-state values, the thermistor readings were averaged over a five-minute window to reduce sensor noise and long-term variability.

Figure 7.

Experimental results: Steady-state control performance evaluation: (a) 35 °C, (b) 40 °C, (c) 45 °C, (d) 50 °C, (e) 55 °C, (f) 60 °C, (g) 65 °C, (h) 70 °C.

Across the low-temperature range (<50 °C), the controller achieves excellent steady-state regulation with a typical error of approximately 0.26 °C. At higher operating temperatures (50–70 °C), a slight increase in steady-state error is observed, with an average value of approximately 0.41 °C. This increase is attributed to the larger temperature gradient between the SMA spring and the ambient environment, which accelerates heat loss and necessitates more frequent control action switching. Nevertheless, the achieved accuracy remains sufficient for stable and safe SMA actuation, confirming the robustness of the proposed control strategy across the full operating range.

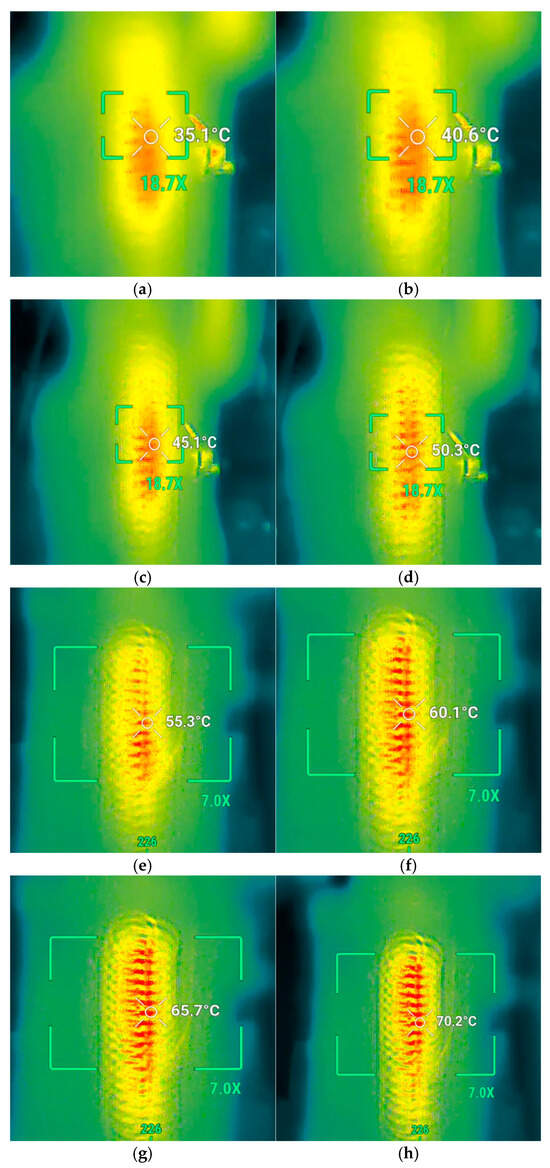

To independently validate the DQN controller performance and verify the actual temperature of the SMA spring, a non-contact thermal imaging camera (DJI Matrice 4T, SZ DJI Technology, Inc., Shenzhen, China) was used to capture the thermal images inside the chamber of the gripper, as shown in Figure 8a–h. The controller was commanded to maintain four temperature setpoints (35 °C to 70 °C). After allowing the system to stabilize for one minute at each setpoint, a thermal image was recorded. The resulting images show a stable and spatially uniform heating distribution along the SMA actuator. The camera’s independent measurement of 35.1 °C (Figure 8a) provides critical external validation, confirming the accuracy of the contact temperature sensor and demonstrating that the controller maintains the actuator at the desired temperature. Similar high-fidelity agreement was observed for the remaining setpoints, with measured temperatures of 40.6 °C, 45.1 °C, 50.3 °C, 55.3 °C, 60.1 °C, 65.7 °C, 70.2 °C.

Figure 8.

Performance evaluation and thermal imaging validation of the heated SMA spring controlled by the DQN-based temperature regulator under four target setpoints: (a) 35 °C, (b) 40 °C, (c) 45 °C, (d) 50 °C, (e) 55 °C, (f) 60 °C, (g) 65 °C, (h) 70 °C.

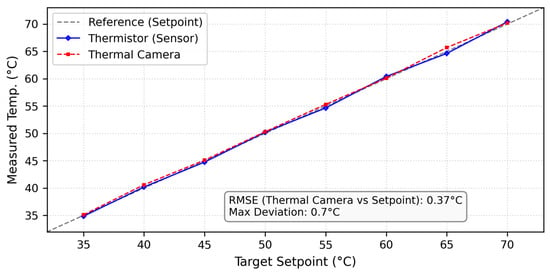

To validate the reliability of the thermal imaging results shown in Figure 8, a quantitative comparative analysis was conducted under steady-state conditions across the full operating temperature range (35–70 °C). Specifically, the spatially averaged temperature obtained from the thermal camera (Tthermal_camera) was compared with the local thermistor measurement (Tthermistor) and the corresponding temperature setpoint (Tsetpoint).

The results, summarized in Figure 9, show that the thermal camera measurements closely track the thermistor readings, yielding a root mean square error (RMSE) of only 0.37 °C. This small discrepancy indicates that no significant spatial temperature gradients exist within the SMA spring after the settling time. The strong agreement between global thermal imaging and local closed-loop sensing confirms that the temperature field experienced by the actuator during operation is effectively uniform. Since the controller relies on the thermistor signal for real-time decision-making, this validation directly demonstrates that the control input accurately reflects the global thermal state of the SMA, providing convincing experimental evidence of both thermal uniformity and control reliability.

Figure 9.

Cross-validation of local temperature sensing (thermistor) and global thermal field measurement (thermal camera).

3.3. Experiment of Grasping Objects with Different Shapes, Sizes, and Weight

3.3.1. Experiment Setup of Grasping Objects with Different Shapes, Sizes, and Weight

To validate the performance of the trained DQN agent in a real-world scenario, a physical hardware testbed was constructed, as illustrated in Figure 10. The setup consists of the SMA-actuated gripper assembly, a low-level embedded control unit, and a high-level processing unit (PC). A block diagram of the overall system architecture is provided in Figure 6.

Figure 10.

The real experimental setup for the grasping test.

The gripper is mounted on the aluminum profile frame. The custom control board is responsible for measuring temperature via thermistors, driving the SMA springs, and controlling the cooling fans. The control system is powered by a 50 W power source (5V, 10A). An ST-Link V2 programmer (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland) is used for firmware upload to the STM32F103 Blue Pill microcontroller (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland).

The grasping experiment is conducted as follows:

- The target object is placed between the two gripper jaws.

- The temperature setpoint is gradually increased from 35 °C until the gripper can securely hold the object for at least two minutes, ensuring steady-state stability.

- A photograph of the grasping action is captured, and the corresponding temperature is recorded for the successful grasping event.

3.3.2. Experiment of Grasping Test with Various Target Objects

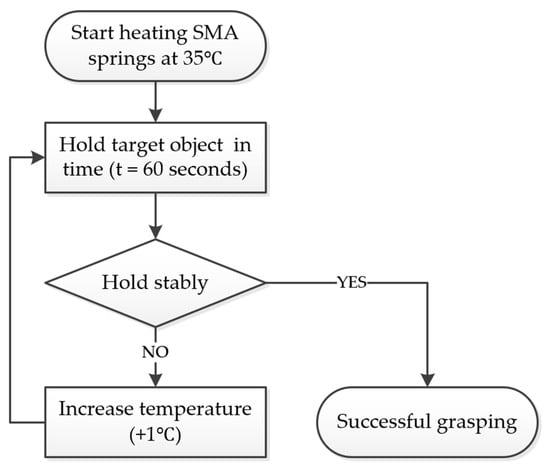

Figure 11 illustrates the flowchart of the SMA-based gripper control strategy during object grasping experiments. The process begins by heating the SMA springs to an initial temperature of 35 °C. The gripper then attempts to hold the target object for a time elapsed of 60 s. A decision step evaluates if the object is held stably. If the object is maintained without slipping or dropping for the full time, the grasping is considered successful. If the object slips or is dropped, the temperature of the SMA springs is incrementally increased by 1 °C, and the grasp attempt is repeated. This iterative approach ensures reliable grasping by adjusting the SMA activation according to the object’s stability. The specifications of the grasping objects are shown in Table 3.

Figure 11.

Flowchart of the grasping strategy for evaluating the controller performance with diverse payloads.

Table 3.

Specifications of target objects used in functional grasping experiments.

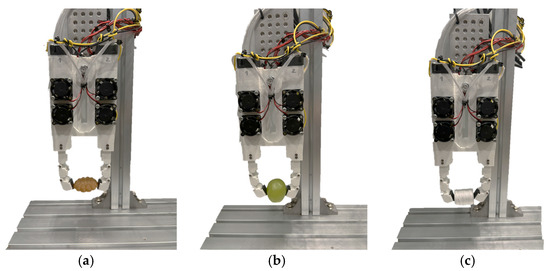

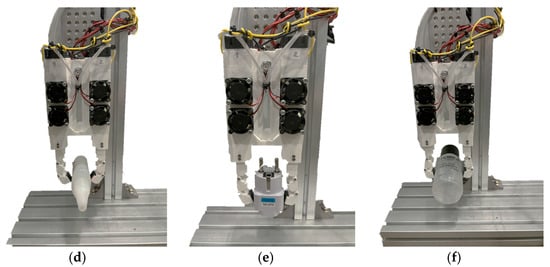

The experimental grasping images, shown in Figure 12, are categorized into two distinct groups to evaluate different control purposes. Figure 12a–c demonstrate the manipulation of small, lightweight, and fragile objects (a grape, a small pastry, and a spool of thread). For these items, the controller successfully maintained a low temperature (35 °C), applying just enough force to secure the object without causing deformation or damage. In contrast, Figure 12d–f show the handling of larger and heavier objects (a plug socket, a metal adhesive bottle, and an acetone bottle). In these cases, the controller stabilized at higher temperatures (42–78 °C) to generate the large contraction and friction force required to hold the heavy payloads without slipping. The list of abbreviations used in this article is included in Table 4.

Figure 12.

Overview of the gripper performing object grasping tasks: (a) grasping a small pastry; (b) grasping a grape; (c) grasping a small pool of thread; (d) grasping a metal adhesive bottle; (e) grasping a plug socket; (f) grasping an acetone bottle.

Table 4.

List of abbreviations used in this article.

4. Discussion

4.1. Assessment of the Proposed Control Strategy

The experimental results validate the effectiveness of the proposed Sim-to-Real pipeline. By defining a granular 12-action discrete space, the DRL agent successfully learned the nonlinear thermal dynamics of the SMA without requiring any real-world training samples. A key merit of this approach is the prevention of temperature overshoot. Unlike conventional PID controllers, which often struggle with the thermal inertia of SMAs, the DRL agent learned to preemptively switch to cooling or lower heating states as the temperature approached the setpoint. This behavior resulted in a steady-state error of only 0.26 °C, enabling safe interaction with delicate objects.

4.2. Evaluation of the Gripper Design

The tendon-driven design offers clear advantages in terms of lightweight structure and inherent compliance. The use of a compliant bias spring allows the gripper to passively adapt to object shapes, reducing the risk of damage to fragile items like pastries (Figure 12a,b).

However, the current design also presents limitations. The cooling rate is slower than the actuation rate, as de-actuation relies on forced air cooling and natural convection. Although the dedicated “Fan ON” action (a11) accelerates cooling, rapid actuation–deactuation cycles remain challenging, which is a known limitation of thermally driven actuators. Furthermore, the maximum grasping force is constrained by the SMA wire diameter. Handling objects heavier than 100 g would require thicker wires or a multi-wire configuration, which would increase force at the expense of response speed.

4.3. Limitations of the Sim-to-Real Pipeline

While the Sim-to-Real transfer demonstrated promising performance, it depends strongly on the accuracy of the thermal parameters identified in simulation (Section 2). Significant changes in environmental conditions, such as ambient temperature variations or altered convection coefficients due to airflow, may degrade policy performance. Future work will explore the incorporation of domain randomization during training to enhance robustness against environmental uncertainties.

5. Conclusions

This study presented a robust Sim-to-Real control framework for a tendon-driven SMA gripper based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. The proposed approach effectively addresses the nonlinear and hysteretic thermal behavior of SMA actuators while ensuring safe and reliable real-world deployment. The main contributions and findings are summarized as follows:

- First, a discrete 12-action control space was designed and trained within a high-fidelity thermal simulation to enable robust Sim-to-Real transfer. Experimental results demonstrate that the learned DRL policy can be directly deployed on physical hardware without additional fine-tuning, confirming the effectiveness of the discrete action formulation in mitigating model mismatch and hardware uncertainties.

- Second, the proposed controller achieves high-precision temperature regulation across a wide operating range (35–70 °C). In the low-temperature regime (<50 °C), a mean steady-state error of approximately 0.26 °C was achieved. At higher operating temperatures (50–70 °C), the steady-state error increased slightly to approximately 0.41 °C due to enhanced heat dissipation, yet remained well within acceptable limits for SMA-based actuation. These results were further validated through non-contact thermal imaging, which showed close agreement between the global thermal field and local thermistor measurements.

- Finally, the practical applicability of the proposed framework was verified through grasping experiments involving objects of different sizes, weights, and fragilities. By accurately regulating the SMA temperature, the gripper was able to generate appropriate grasping forces without damaging delicate objects or losing heavy payloads. Overall, the results demonstrate that the proposed Sim-to-Real DRL-based control strategy provides a reliable and scalable solution for precise temperature-controlled SMA actuation in soft robotic grippers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.T.D.; methodology, P.T.D.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.K. and P.T.D.; experiment, P.T.D., H.K. and H.P.; writing—review and editing, Y.K., Q.N.L., S.S., K.P. and P.T.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Korea Agency for Infrastructure Technology Advancement (KAIA) grant funded by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (Grant RS-2025-02315537).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ding, Q.; Chen, J.; Yan, W.; Yan, K.; Kyme, A.; Cheng, S.S. A High-Performance Modular SMA Actuator with Fast Heating and Active Cooling for Medical Robotics. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2022, 27, 5902–5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, P.T.; Le, Q.N.; Luong, Q.V.; Kim, H.-H.; Park, H.-M.; Kim, Y.-J. Tendon-Driven Gripper with Variable Stiffness Joint and Water-Cooled SMA Springs. Actuators 2023, 12, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Sun, B.; Ding, Q.; Yan, W.; Zheng, W.; Yan, K.; Hong, Y.; Cheng, S.S. Design, Modeling, and Control of a Compact SMA-Actuated MR-Conditional Steerable Neurosurgical Robot. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 1381–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Cui, Y.; Sun, H.; Shao, Q.; Zhao, H. Active-Cooling-in-the-Loop Controller Design and Implementation for an SMA-Driven Soft Robotic Tentacle. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 2325–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lexcellent, C.; Leclercq, S.; Gabry, B.; Bourbon, G. The Two Way Shape Memory Effect of Shape Memory Alloys: An Experimental Study and a Phenomenological Model. Int. J. Plast. 2000, 16, 1155–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Kim, S. Structural Morphing Using Two-Way Shape Memory Effect of SMA. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2005, 42, 1759–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur, S.; Frantziskonis, G.N.; Muralidharan, K. Atomistic Simulation of Shape Memory Effect (SME) and Superelasticity (SE) in Nano-Porous NiTi Shape Memory Alloy (SMA). Comput. Mater. Sci. 2018, 152, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Patel, S.; Swain, B.; Roshan, R.; Sahu, N.K.; Behera, A. A Brief Review of Shape Memory Effects and Fabrication Processes of NiTi Shape Memory Alloys. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 33, 5552–5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xiang, Y.; Yu, J.; Yang, L. Development and Prospect of Smart Materials and Structures for Aerospace Sensing Systems and Applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanza, G.; Tata, M.E. Shape Memory Alloys for Aerospace, Recent Developments, and New Applications: A Short Review. Materials 2020, 13, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, E.T.F.; Friend, C.M.; Allen, D.M.; Hora, J.; Webster, J.R. A Technical and Economic Appraisal of Shape Memory Alloys for Aerospace Applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 438–440, 589–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, K.; Haribhakta, V.K.; Jadhav, P.V. A Review of Shape Memory Alloys in MEMS Devices and Biomedical Applications. Mater. Today Proc. 2024, S2214785324002943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchareb, N.; Fellah, M.; Hezil, N.; Guesmi, A.; Khezami, L. A Review of Nitinol Shape Memory Alloys for Biomedical Applications: Advancements and Biocompatibility. JOM 2025, 78, 140–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wagner, R.J.; Liu, S.; He, Q.; Li, T.; Pan, W.; Feng, Y.; Feng, H.; Meng, Q.; Zou, X.; et al. Locomotion of an Untethered, Worm-Inspired Soft Robot Driven by a Shape-Memory Alloy Skeleton. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zhuo, J.; Fan, M.; Li, X.; Cao, X.; Ruan, D.; Cao, H.; Zhou, F.; Wong, T.; Li, T. A Bioinspired Shape Memory Alloy Based Soft Robotic System for Deep-Sea Exploration. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 6, 2300699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, G.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Z.; Ren, Y.; Cui, L.; Yu, K. Large Thermal Hysteresis in a Single-Phase NiTiNb Shape Memory Alloy. Scr. Mater. 2022, 212, 114574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Hubert, O.; He, Y. Characterization on Thermal Hysteresis of Shape Memory Alloys via Macroscopic Interface Propagation. Materialia 2024, 33, 102038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, R.-C.; Precup, R.-E.; Preitl, S.; Szedlak-Stinean, A.-I.; Bojan-Dragos, C.-A.; Hedrea, E.L.; Petriu, E.M. PI Controller Tuning via Data-Driven Algorithms for Shape Memory Alloy Systems. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth, D.J.S.; Sohn, J.-W.; Dhanalakshmi, K.; Choi, S.-B. Control Aspects of Shape Memory Alloys in Robotics Applications: A Review over the Last Decade. Sensors 2022, 22, 4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Liu, H.; Hao, L. Model-Free Adaptive Sliding Mode Control of Parallel Platform Actuated by Shape Memory Alloys. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 160845–160854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.M.; Bijalwan, V.; Baek, H.; Shin, B.; Kim, Y. Dynamic High-Gain Observer Approach with Sliding Mode Control for an Arc-Shaped Shape Memory Alloy Compliant Actuator. Microsyst. Technol. 2024, 30, 1593–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pi, Y. Fuzzy Time Delay Algorithms for Position Control of Soft Robot Actuated by Shape Memory Alloy. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2021, 19, 2203–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.F.M.; Kim, Y.; Le, Q.H.; Shin, B. Modeling and Control of Two DOF Shape Memory Alloy Actuators with Applications. Microsyst. Technol. 2022, 28, 2305–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, E.F.; Murrieta-Cid, R.; Becerra, I.; Esquivel-Basaldua, M.A. A Survey on Deep Learning and Deep Reinforcement Learning in Robotics with a Tutorial on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Intell. Serv. Robot. 2021, 14, 773–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarz, J.; Tan, J.; Finn, C.; Kalakrishnan, M.; Pastor, P.; Levine, S. How to Train Your Robot with Deep Reinforcement Learning: Lessons We Have Learned. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2021, 40, 698–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, R.; Niu, H.; Carrasco, J.; Arvin, F.; Yin, H.; Lennox, B. Design and Experimental Validation of Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Fast Trajectory Planning and Control for Mobile Robot in Unknown Environment. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 5778–5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Zhang, T. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Mobile Robot Navigation: A Review. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2021, 26, 674–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaoui, H.; Gualous, H.; Boulon, L.; Kelouwani, S. Deep Reinforcement Learning Energy Management System for Multiple Battery Based Electric Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference (VPPC), Chicago, IL, USA, 27–30 August 2018; IEEE: Chicago, IL, USA; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.