Abstract

This paper presents a novel rotary electromagnetic actuator designed for high-speed and high-precision positioning with ultra-low power consumption, intended for industrial and scientific applications such as rotary index tables, pick and place robots, or optical systems, among others. The actuator is based on harnessing electromagnetic potential energy and its transformation into kinetic energy to enable accurate and rapid changes between different equilibrium positions of the device. A prototype with an outer diameter of 86 mm and a thickness of 25 mm and a mass of about 0.57 kg has been manufactured and tested. It presents eight equilibrium positions evenly separated to 45 degrees, reachable in just 48 ms with a positioning accuracy of 20 arcmin. Experimental results demonstrate that the device generates a torque of 590 mNm, maximum angular speed and acceleration up to 663 rpm and 14,500 rad/s2, respectively, with an input current of ±500 mA and a maximum power consumption of just 6.3 W. This value of power consumption represents a power saving up to 80% when compared to a conventional electromagnetic actuator that reproduces the same motion profile. An energy saving up to 38% is calculated for a change between two adjacent equilibrium positions. This innovative technology provides a new tool for precise positioning in highly dynamic applications with unprecedented energy and power savings.

1. Introduction

There are several engineering and scientific applications that require high accuracy and rapid angular or linear positioning of a payload. Some examples include widely extended applications such as process feeding in serial manufacturing [1], fast tool change systems for machining centers [2], pick-and-place manipulators [3,4,5] and industrial rotary index tables [6], biomedical applications [7,8], or optical filter wheels [9,10].

In all those applications, the payload must be highly accelerated and later decelerated to achieve the target commanded positions with precision and in a fast manner. Power requirement of the actuation system grows with the required acceleration of the payload and increases their energy consumption [11,12,13]. Moreover, heat dissipation becomes a main limitation in the feasibility of this type of electromagnetic actuators [14,15,16,17,18]. Therefore, due to the high-power requirement, the reduced efficiency and thermal issues electromagnetic actuators for highly dynamic applications tend to be over-dimensioned in terms of mass and envelope; they require larger amounts of magnetic materials and present higher environmental impact and operational costs.

In this context, high torque density, high speed, and minimal power consumption are challenging and highly desired features. In this paper, we propose a novel type of electromagnetic actuator based on harnessing of potential magnetic energy, which was theoretically described in a previous paper [19]. This novel technology provides a breakthrough in electromagnetic actuation for highly dynamic positioning applications where power and energy consumption are required or desired to be minimized. A prototype of a potential energy actuator for positioning of a filter wheel payload is theoretically described, manufactured, and experimentally tested in this paper. Experimental results verify the actuation concept and demonstrate high potential for drastic power and energy savings in this type of application.

2. Principle of Operation

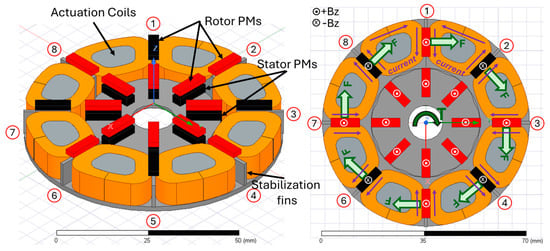

In this section, the principle of operation of the device is described. A particular realization of the proposed actuator is presented in Figure 1, where its main magnetic elements are shown. The actuator presents eight stable equilibrium positions evenly distributed at each 45 degrees (identified in Figure 1 with numbers from 1 to 8). The device is composed mainly of four elements:

Figure 1.

(Left): Isometric view of the actuator. Black and red PMs are magnetized in opposing directions; (Right): Illustration of rotor forces and torque and magnetic and electric fields.

- A rotor, mainly composed of a set of permanent magnets (PMs), evenly distributed at each 45°, magnetized in a direction parallel to the axis of rotation of the actuator.

- A stator mainly composed of a set of PMs, actuation coils, and stabilization fins. The PMs are magnetized parallel to the axis of rotation, with facing opposing magnetic polarities to the PMs in the innermost part or the rotor. When rotor and stator PMs are aligned, they repel each other and store potential magnetic energy.

- The stabilization fins, made of a soft magnetic material, attract the PMs in the outermost part of the rotor, generating a local energy potential well in points of stable equilibrium distributed at , where n is an integer number from 1 to 8.

- Finally, a set of eight actuation coils are placed in each stator part with an angular phase of 45/2 degrees with respect to the PMs in the stator. They are used to overcome the potential energy well and switch from one stable position to another. Forces and momentum generated by the actuation coils are illustrated in Figure 1.

Because the PMs of the stator and the innermost PMs of the rotor present facing opposing polarities, a significant amount of potential magnetic energy is stored when the rotor and stator magnets are aligned in the equilibrium positions . However, without the aid of the stabilization fins, those positions would be of unstable equilibrium, and any external disturbance would cause the rotor to suddenly abandon these positions and get to the equilibrium positions located at . By incorporating a set of properly dimensioned stabilization fins in the desired equilibrium positions, they become stable equilibrium points. Then, the rotor will remain in these positions (, even if there are small external disturbances present.

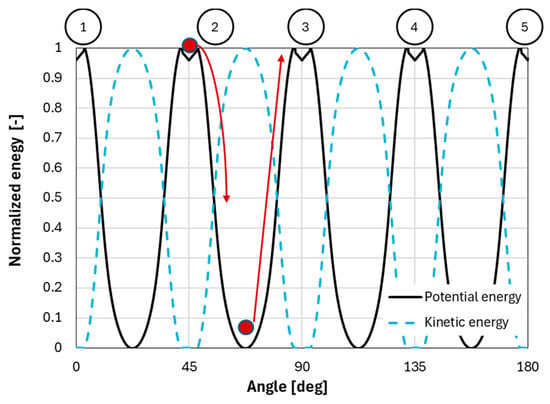

These local potential wells can be overcome by using the actuation coils. By controlling the current level and flow direction, the rotor moves from one equilibrium position to another in the desired direction. When potential wells are overcome, all the stored potential magnetic energy is released, transformed into kinetic energy and back to potential energy as the rotor moves from one equilibrium position to another as illustrated in Figure 2. Energy losses coming from friction or electromagnetic losses shall be compensated by the actuation coils in order to achieve a successful change of position. By this potential energy harnessing principle, it is no longer necessary to externally supply the total power and energy required to accelerate and decelerate the payload. Just a reduced fraction of the energy and power is required to get the rotor from one stable equilibrium to another. The reduction in energy and power consumption potentially results in a more compact system, with reduced operational costs and a reduced environmental impact.

Figure 2.

Normalized kinetic and potential energy of the rotor vs. its angular position.

The number of equilibrium positions can be calculated from the angular period of symmetry of the actuator (). A larger number of equilibrium positions can be obtained by reducing the period of symmetry and increasing the number of coils and PMs in the rotor and stator consequently. For example, a period of symmetry of would provide 12 equilibrium positions and a period of would result in 24 positions of equilibrium.

3. Theoretical Model

A detailed theoretical model and finite element model (FEM) have already been presented and thoroughly discussed in a previous publication [19]. However, the theoretical model is summarized in this section to facilitate understanding of the operating principles of the actuator and the results are presented herein. From a theoretical point of view, based on the principle of conservation of angular momentum (L) of the rotor, it can be stated that:

where is the total torque applied in the direction of the axis of rotation (z), is the moment of inertia of the rotor, and its angular acceleration.

The total torque includes the torque due to its magnetostatic interactions () with PMs and other components of the stator. has been calculated as a function of the angular position of the rotor () using the FEM model described in detail in [19], and experimentally verified in Section 6.1 of this paper. also includes other components such as friction torque in the kinematic chain. For a given rotation from to , the following applies:

where is the angular speed of the rotor.

From the previous equation, the final angular velocity () can be calculated as:

Then, a time description of the motion of the rotor can be obtained by the application of finite differences, so the elapsed time between two very close angular positions can be calculated as:

where is a small angular step and is the average angular speed in the step.

As will be later demonstrated, this simple mathematical formulation is enough for a precise prediction of the motion profile of the rotor.

Power saving potential of the actuator is defined in this paper as a comparison between the electrical consumption of the actuator and the theoretical power consumption that a conventional electromagnetic actuator would present in order to reproduce the same motion profile observed in the experiments. Therefore, the power saving ratio is defined as:

where is the maximum experimental value of the electrical power consumption of the actuator and is the maximum power required for a classical electromagnetic actuator to reproduce the observed motion profile.

On one hand, is determined from experimental data as a function of the electrical current (I) and the resistance of the winding (). On the other hand, is calculated as the sum of the useful mechanical power and the power losses of the system:

where the mechanical useful power can be calculated as:

Power losses on the device () mainly come from the friction in the components of the kinematic chain and the bearings of the actuator and electromagnetic losses of the actuator. Friction losses in the kinematic chain are calculated using Equation (9). The friction torque () has been experimentally measured and it is observed to be constant for the range of speeds in this paper.

Power losses induced by the actuator’s bearings potentially come from mechanical and magnetic forces caused by misalignments, unbalancing, and inhomogeneities in the rotor and stator of the actuator. They remain unknown since they have not been independently determined. Finally, electromagnetic power losses in the actuator come from two main phenomena: eddy current and hysteresis losses inside the actuator. They have been calculated by FEM following the detailed procedure described [19], where the electromagnetic power losses are reported at different speeds.

Finally, the energy saving ratio is defined as the energy consumption of the actuator for a change between two equilibrium positions vs. the energy consumption that a conventional electromagnetic actuator (without regeneration) would require to reproduce the observed motion profile. It can be calculated as:

where electrical energy consumption is calculated as:

And the energy consumed by an equivalent electromagnetic actuator as:

where the mechanical energy is obtained from the integral of the absolute value of the actuation torque vs. angular position for a change between two stable positions and the energy losses are calculated as the integral of the power losses over time.

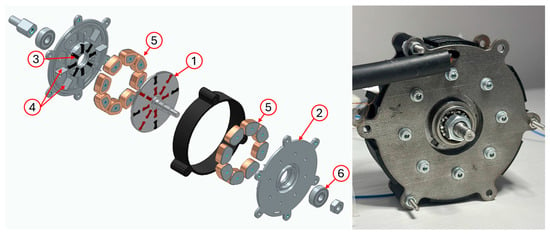

4. Description of the Prototype

An axial flux, single phase, rotary actuator with eight equilibrium positions, evenly separated by 45 degrees, has been designed, manufactured, and tested. The actuator measures 86 mm in diameter and 25 mm in thickness and has a mass of 0.57 kg. The rotor moment of inertia is estimated at kgm2. Figure 3 shows the detailed design and a picture of the actuator.

Figure 3.

(Left): Detailed design of the potential actuator. 1. Rotor, 2. Stator yoke, 3. PMs, 4. Stabilization fins, 5. Coils, 6. Bearing. (Right): Actuator assembled.

The rotor (1) consists of an AISI 304 stainless steel wheel with an outer diameter of 68 mm, onto which 16 nickel coated Nd2Fe14B N35H permanent magnets, with a typical remanence Br = 1.2 T and a coercivity Hc = 910 kA/m, are assembled. The PMs dimensions are 3 × 3 × 10 mm, being magnetized parallel to the axis of rotation of the actuator. While the eight PMs in the innermost part of the rotor are magnetized in the same direction of space, the other eight magnets in the outermost circumference of the rotor are assembled with opposing directions of magnetization to one another, as represented by PMs of different colors in Figure 1 and Figure 3. Rare earth magnets are used in this prototype, owing to their higher performance; however, the increasingly critical challenges associated with their supply in certain regions of the world may raise concerns regarding their use and availability. In this context, alternative PM materials such as AlNiCo or ferrite alloys [20] may also be considered, although their use will probably result in a reduced performance of the device. Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that the novel actuator concept presented in this paper provides a substantial gain in power output and energy efficiency compared with conventional electromagnetic actuators. This fact ultimately enables a more efficient use of PM materials needed in their construction.

The stator is mainly composed of two symmetric yokes made of low carbon steel AISI 1020 (2). In each of these yokes, eight PMs (3) identical to those in the rotor are assembled. All of them are magnetized parallel to the axis of rotation of the actuator and they are assembled with facing opposing polarities to those PMs in the innermost part of the rotor, generating the magnetic potential energy to be harnessed. As part of the stator, 16 stabilization fins made of steel AISI 1020 (4) are manufactured too. They are 1 mm in thickness and 13.1 mm in radial length. These stator fins attract the PMs in the outermost part of the rotor, generating eight equilibrium positions.

Both stator and rotor PMs are evenly separated degrees to one another. The airgap between the PMs in the rotor and the stator is measured in 1.8 ± 0.1 mm while the airgap between the rotor magnets and the fins is measured in 1.9 ± 0.1 mm.

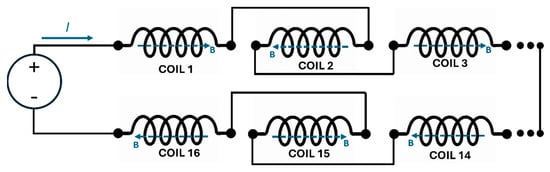

Finally, a set of 16 coils (5) are also integrated in the stator in between the stabilization fins, half of them in each stator yoke. Each of the coils is mainly composed of a solid steel AISI 1020 core with the shape of a 23 degrees circular segment of outer radius 32.5 mm, 23.5 mm inner radius, and 7.5 mm height. The coil cores are mechanically fastened to the stator by means of an M6 screw located at the center of each core. The centers of all coils are arranged along a 28 mm radius circumference, concentric with the axis of rotation of the actuator. About 110 turns of AWG 28 copper magnetic wire are wound on each coil. Coils in each stator yoke are connected in anti-series to one another, so the magnetic field direction they produce is inverted from one coil to the contiguous, as observed in Figure 1. Then, the coils in a yoke are connected in series to the coils in the other yoke, so the magnetic circuit is closed. The resistance of the winding (series of the 16 coils) is measured as 25.4 Ohm and its inductance as 14 mH. A schematic diagram of the electrical connection of the coils is provided in Figure 4, with emphasis on the direction of the magnetic field (B) generated by the coils.

Figure 4.

Electrical connection diagram of the motor windings.

Finally, two deep groove ball bearings (6) from NSK model 628, 24.1 mm in outer diameter, are used to allow smooth rotation. Main characteristics of the actuator are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Device main characteristics.

5. Experimental Set Up and Test Procedure

Two sets of tests were conducted to characterize the performance of the actuator: quasi-static and dynamic tests. The objective of the quasi-static characterization tests was to measure the torque experienced by the rotor vs. its angular position for a full revolution under different levels of excitation current in the winding of the actuator.

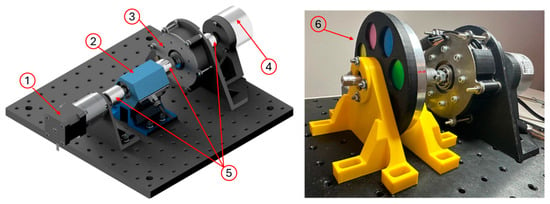

The quasi-static characterization testbench is mainly composed of a geared NEMA 17 bipolar stepper motor (gear ratio i = 1:50) with 20 Nm maximum output torque and about 2 arcmin step angle (1), a slipring DR-20 rotating torque sensor from Lorenz M. GmbH with 1 Nm maximum allowable torque and 1 mNm accuracy (2), the actuator (3) and an optical encoder (4) from Sick model DBS60E with about 4 arcmin resolution and rotor inertia J = 3.3 × 10−6 kgm2. All components were connected using elastic aluminum alloy couplings (5) and assembled on top of an optical table as shown in Figure 5. Data acquisition was performed using a NI USB 6211 16 bit analog/digital board, which was also used for control of the actuation. A KD 3305D DC voltage source from Korad was used for supply of the input voltage and current in the motor. By measuring the voltage drop in a precision resistor of resistance 0.25 Ω connected in series with the actuator winding, the input current was characterized. Quasi-static characterization tests were carried out by slowly actuating the stepper motor for, at least, a full revolution of the actuator while torque and angular position were continuously measured. Then, the test is repeated at different input current levels from 500 to −500 mA. Results are reported in Section 6.1.

Figure 5.

(Left): CAD representation of the testbench for quasi-static characterization tests. (Right): Picture of the testbench for dynamic testing with payload. 1. Stepper motor, 2. Torque sensor, 3. Actuator, 4. Encoder, 5. Elastic couplings, 6. Payload.

After the quasi-static characterization tests were completed, the stepper motor and the torque sensor were removed from the kinematic chain, and the actuator was characterized in dynamic conditions, just connected to the encoder. The input voltage, current, and rotor angular position were measured for the dynamic tests reported in this paper. Speed and angular acceleration are then obtained by differentiation of the angular position with time and compared to the theoretical calculations. Then, dynamic tests were repeated by connecting the actuator to a payload that simulates a filter wheel (6) with 8 filters (and equilibrium positions). It is mainly composed of an Al 6061-T6 disc of 95 mm diameter and about 0.3 kg in mass and an equivalent moment of inertia J = kgm2. As dynamic performance depends on the moment of the inertia of the system it is convenient to define a ratio of the moments of inertia as:

where is the moment of inertia of the rotor of the actuator and is the total moment of inertia of the system (including ). Table 2 summarizes the moments of inertia for the various dynamic tests reported in this paper.

Table 2.

Description of the dynamic test and their associated moment of inertia.

6. Experimental Results and Discussion

6.1. Quasi-Static Testing

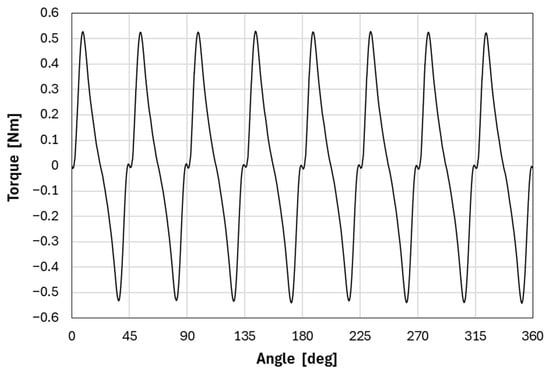

Figure 6 shows the torque vs. angular position of the rotor when no current flows through the coils. Eight positions of stable equilibrium can be observed at . The actuator maximum torque is calculated from the average of the 16 absolute values of the maximum and minimum torque shown in Figure 6. The average value is then calculated as 536 ± 6 mNm. Similarly, the absolute mean value of the maximum and minimum stabilization torque around the stable positions is calculated as 7 ± 2 mNm.

Figure 6.

Experimental toque vs. angle for I = 0 A.

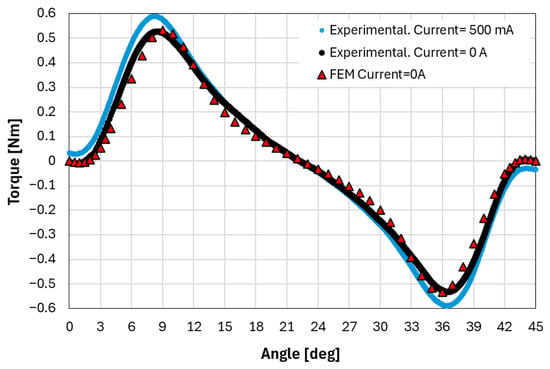

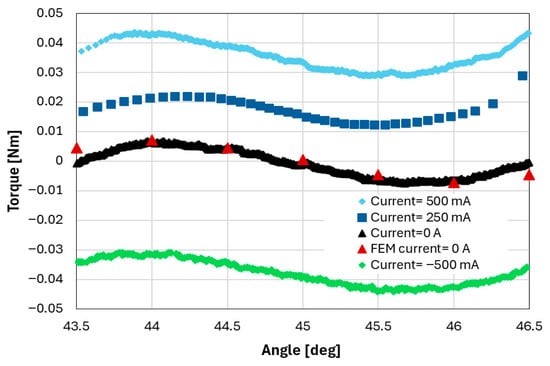

Figure 7 shows the rotor torque vs. angle measured in quasi-static conditions from 0 to 45 degrees (separation between stable positions) for an actuation current of 0 A and 500 mA and compared with the results of the FEM model [19] for an excitation current I = 0 A. A good agreement is observed between experimental and FEM results.

Figure 7.

Experimental and FEM toque vs. angle between two stable positions.

Figure 8 shows the rotor torque around the 45 degrees stable position for various currents excitations between ±500 mA. It can be observed that a relatively small current (calculated in about ±150 mA) is enough to overcome the potential energy well. The sign of the current defines the direction of motion. Again, a good agreement is observed between FEM and experimental results.

Figure 8.

Experimental and FEM toque vs. angle between in the surroundings of an equilibrium position.

6.2. Dynamic Performance Testing

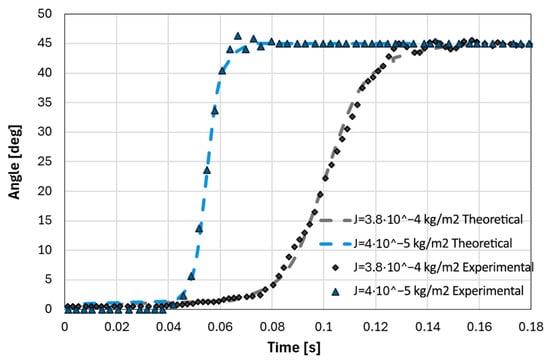

First, the actuator capacity for implementing a change between contiguous stable positions from 0° to 45° was evaluated without payload () and then including the payload (). Once the setup is ready, the actuator is excited by an input voltage of about ±12.7 V. This excitation voltage generates a maximum current amplitude of about ±500 mA, which was the minimal excitation current experimentally determined for a repeatable and successful operation of the actuator. The current in the coils was close-loop controlled by measuring the rotor angular position and based on a programmed command that minimizes energy consumption, as will be explained later. Figure 9 shows the rotor angle vs. time for a successful change between continuous stable positions of the actuator for both set ups, without payload ( or J = kgm2) and with the payload ( or J = kgm2). Experimental data are also compared with the theoretical calculations in Section 3 using FEM torque vs. angle as input data. A very good agreement between experiments and theory is observed, validating the FEM analysis.

Figure 9.

Experimental and theoretically calculated angular position of the rotor vs. time.

From data in Figure 9, a maximum angular speed of 663 rpm and angular acceleration of 14,500 rad/s2 for the actuator with , and 216 rpm and 1540 rad/s2 for the actuator with the payload () are calculated. The time required for a position time change is determined in t = 48 ms for and t = 140 ms for As the inertia of the system increases, the angular acceleration and speed are reduced and the time required for a position change increases consequently.

As previously mentioned, the motion of the actuator was close-loop controlled using the angular position signal from the encoder. A regulable DC power supply was used for generation of the ±12.7 V excitation and a full H-bridge electronic circuit based on chip L293B from STMicroelectronics was implemented for the control of the sign of the excitation current in the winding. The TTL command signal was programmed in NI LabVIEW and generated by the data acquisition board NI 6211. The excitation sequence programmed was as follows:

- Without payload :

- ○

- V = 12.7 V from [0 to 22 deg] and V = −12.7 V from [>22 to 38 deg].

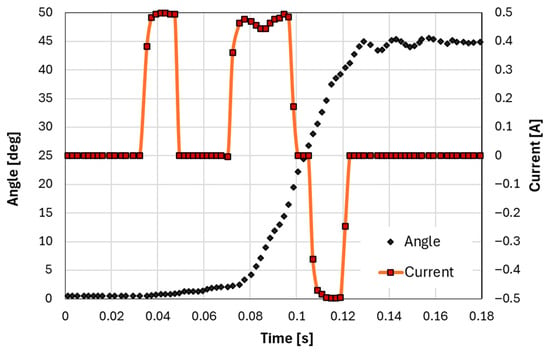

- With payload : Defined for minimization of energy consumption in a position change and shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Angle and current vs. time in a change between stable positions for .

Figure 10. Angle and current vs. time in a change between stable positions for .- ○

- V = 12.7 V from 0 to 1 deg (initial impulse); from 2 to 15 deg (positive current) and V = −12.7 V from 25 to 38 (negative current).

- ○

- V = 0 from 1 to 2; from 15 to 25 deg, and from 38 to 45 deg.

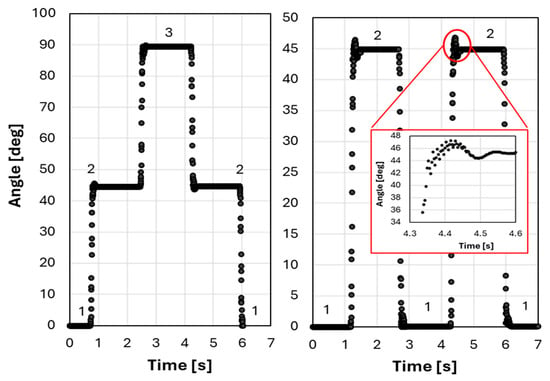

After these preliminary validation tests were performed, a set of motion profiles were programed and executed using the configuration with the payload ). Figure 11 shows two alternative motion profiles changing positions from 0, 45, and 90 degrees.

Figure 11.

Two different motion profiles. Position 1 = 0°; Position 2 = 45°; Position 3 = 90°.

A set of spikes and oscillations in the rotor’s angular position can be observed in the vicinity of the equilibrium positions in Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11. These oscillations are underdamper harmonic vibrations of the rotor around the stable equilibrium positions of the actuator.

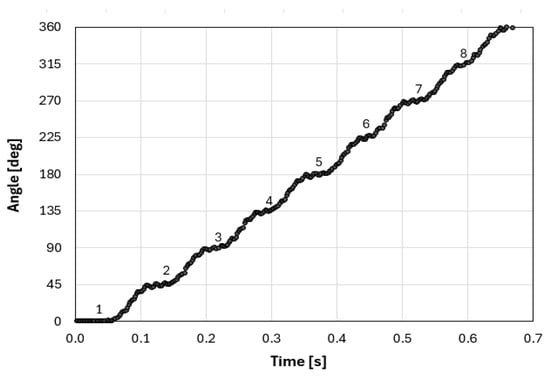

Finally, the actuator was also controlled in what we call continuous motion mode. In this mode, the actuator changes continuously from one stable position to the next one. Figure 12 shows the rotor position in continuous mode for a full revolution. An average speed of 92 rpm is calculated in this mode of actuation.

Figure 12.

Actuator in continuous motion operational mode.

A video of the actuator in continuous motion operational mode is included as Supplementary Materials.

6.3. Position Accuracy and Repeatability

Position accuracy and repeatability of the actuator are evaluated from the experimental results in Figure 11 and Figure 12. Accuracy is calculated as the difference between the target angular position and the measured position achieved after a successful position change:

An average accuracy in positioning can be calculated as 20 ± 20 arcmin. We believe that this accuracy and repeatability can be further improved by implementing a PI control strategy that considers the target position as the output.

6.4. Power and Energy Saving

One of the main objectives of this paper is to demonstrate the potential of the technology for power and energy saving in highly dynamic applications. For the evaluation of the power and energy saving potential, two magnitudes are compared, as explained in Section 3 of this paper. On the one hand, the measured electrical power and energy consumption and, on the other, the power and energy consumption that a conventional electromagnetic actuator would present to reproduce the observed motion profile.

The maximum electrical power consumption for the proposed actuator is independent of the payload, and it is equal to 6.3 W. The equivalent conventional actuator power is calculated using Equation (7). For evaluation of the friction losses of the kinematic chain, the friction torque was experimentally evaluated at different speeds from 0 to 750 rpm. A mostly constant friction torque of about 10 mNm in the case of and 13.5 mNm for was observed. Finally, electromagnetic power losses in the components of the actuator have been calculated by FEM described in [19], and their value, dependent on the speed, are there reported. Other sources of power losses, such as misalignments in the actuator or friction in the bearings of the actuator, even though surely present, have not been considered in the calculation of and . Measured and calculated maximum power losses and energy consumption are included in Table 3.

Table 3.

Main results of the performance evaluation of the prototype.

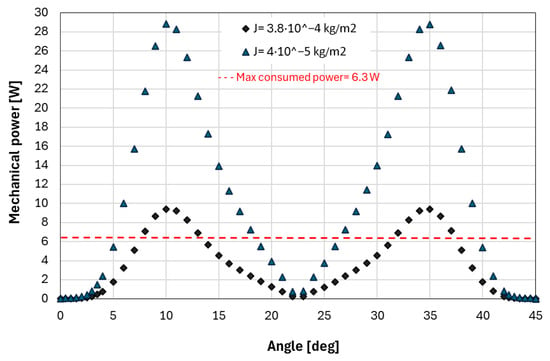

Figure 13 shows the equivalent actuator mechanical power vs. the angular position of the rotor and the experimental maximum power consumption of the potential actuator. From results in Figure 13 and Table 3, the power saving ratio is calculated as:

Figure 13.

Theoretical and maximum experimental power consumption.

The power saving of the actuator is remarkable in both cases, reducing the maximum power of the actuator up to 80% compared to that of a conventional actuator. It must be noted that for values of power losses and mechanical power of the potential actuator in this paper (see Table 3), a conventional actuator efficiency of about 90% could be calculated, which seems reasonable and fair for the comparison done.

It can be observed that both the power saving and the energy saving ratio are both dependent on the payload ratio. The energy saving for the potential actuator with no payload assembled is determined to be about 37.8%, which is a very significant and promising energy saving. In both cases, energy and power saving ratio could be highly improved by reducing the power losses of the actuator to a theoretical maximum of about 90% [19].

Finally, Table 3 summarizes the measured and calculated main performance parameters of the actuator.

7. Conclusions

Electromagnetic actuators for highly dynamic applications, due to the high-power requirement, the reduced efficiency, and associated thermal issues, tend to be over-dimensioned in terms of mass and envelope; in addition, they require larger amounts of magnetic materials and present higher environmental impact and operational costs. In this paper, a breakthrough concept of an ultra-low power consumption rotary electromagnetic actuator for high-speed and precise positioning is presented.

The novel actuator, based on the principle of potential magnetic energy harnessing, is mainly composed of a set of PMs with facing opposing polarities that provide the magnetic potential energy, a soft ferromagnetic system for passive stabilization of the rotor in its equilibrium positions. The theoretical principles of operation of the actuator and an experimental validation of the concept are presented in this paper. A prototype of such an actuator, an axial flux, single phase electromagnetic actuator with eight equilibrium positions has been designed, manufactured, and experimentally validated. The actuator has a diameter of 86 mm, a thickness of 25 mm, and a mass of 0.57 kg. Its rotor inertia is kgm2. The device is actuated by a single phase winding of 16 coils connected in series with a total resistance of 25.4 Ω. The motion between stable equilibrium positions is controlled by a short current pulse, with the direction of motion defined by the sign of the excitation current. For an excitation current of ±500 mA and a maximum power consumption of 6.3 W, a maximum torque of ±590 mNm is produced by the actuator. Therefore, a torque density of 4 kNm/m3 and a specific torque of 1.1 Nm/kg can be calculated.

Dynamic parameters of the actuator are highly dependent on the ratio of the moment of inertia of the payload to the moment of inertia of the rotor. For a payload ratio close to 1, the time required for change between stable positions is minimum and equal to just 48 ms. Maximum speed and angular acceleration of the actuator have been measured in 663 rpm and 14,500 rad/s2 respectively. For a payload ratio close to 11, the time for position change is 140 ms, the maximum speed 216 rpm and the maximum acceleration 1540 rad/s2. Moreover, the accuracy of the positioning is experimentally determined in 20 ± 20 arcmin.

Thanks to the harnessing of the potential magnetic energy principle, the maximum power requirements of the actuator and its energy consumption can be highly reduced compared to those of a conventional electromagnetic actuator. A maximum reduction of the peak actuation power of 80% and a maximum reduction of the consumed energy of 38% is experimentally determined.

These promising results provide an experimental verification of a breakthrough concept of electromagnetic actuators with immense potential for drastic reduction in power and energy consumption in highly dynamic applications requiring precise positioning of a payload such as optical filter wheels, rotary index tables, or pick and place robotic manipulators.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/act15010025/s1.

Author Contributions

Software, M.A.-C. and D.L.-P.; Experimental tests, O.M.-N.; Analysis of the results: M.A.-C. and I.V.-B.; Supervision, I.V.-B. and S.S.-P.; Project administration, I.V.-B.; Funding acquisition: I.V.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has received funding from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities under grant agreement numbers RYC-2017-23684 and CNS2023-143982.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z. A review of CNC feed systems dynamics design: Time-domain accuracy and coupling mechanisms. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 141, 5931–5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gest, G.; Culley, S.; McIntosh, R.; Mileham, A.; Owen, G. Review of fast tool change systems. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 1995, 8, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzzone, L.; Verotti, M.; Fanghella, P. Dynamic model and performance assessment of the natural motion of a SCARA-like manipulator in pick-and-place tasks. Rob. Auton. Syst. 2026, 195, 105215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodovozov, V.; Raud, Z.; Petlenkov, E. Intelligent Control of Robots with Minimal Power Consumption in Pick-and-Place Operations. Energies 2023, 16, 7418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.; Shao, Z.-F.; Guan, L.; Xie, F.; Tang, X. Dynamic performance analysis of the X4 high-speed pick-and-place parallel robot. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2017, 46, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taek, O.Y. Design of precision angular indexing system for calibration of rotary tables. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2012, 26, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Fuaad, M.R.; Hasan, M.N.; Ahmad Asri, M.I.; Mohamed Ali, M.S. Microactuators technologies for biomedical applications. Microsyst. Technol. 2023, 29, 953–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba-Alumbreros, G.; Moron-Alguacil, C.; Fernandez-Munoz, M.; Valiente-Blanco, I.; Diez-Jimenez, E. Scale Effects on Performance of BLDC Micromotors for Internal Biomedical Applications: A Finite Element Analysis. J. Med. Devices 2022, 16, 031011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, O.; Birkmann, S.; Blümchen, T.; Böhm, A.; Ebert, M.; Grözinger, U.; Henning, T.; Hofferbert, R.; Huber, A.; Lemke, D.; et al. Cryogenic wheel mechanisms for the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST): Detailed design and test results from the qualification program. In Advanced Optical and Mechanical Technologies in Telescopes and Instrumentation; SPIE: New York, NY, USA, 2008; p. 701824. [Google Scholar]

- McCully, S.; Clark, C.; Schermerhorn, M.; Trojanek, F.; O’Hara, M.; Williams, J.; Thatcher, J. Development Tests of a Cryogenic Filter Wheel Assembly for the NlRCam Instrument. In Proceedings of the 38th Aerospace Mechanisms Symposium, Williamsburg, VA, USA, 17–19 May 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Antonino-Daviu, J. Electrical Monitoring under Transient Conditions: A New Paradigm in Electric Motors Predictive Maintenance. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Energy-Saving Design and Research of High-Speed Permanent Magnetic Synchronous Motor Under the Development of Rare Earth Resources. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2024, 19, 1565–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakeman, N.; Bullough, W.; Bingham, C.; Mellor, P. Brushless PM linear actuator for high acceleration textile winding applications. Int. J. Appl. Electromagn. Mech. 2004, 19, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Chen, Z.; Du, R.; Feng, M. Loss and Thermal Analysis of a High-Power-Density Permanent Magnet Starter/Generator. Energies 2024, 17, 5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, P.; Liu, L.; Xu, Q.; Che, S.; Zhang, L.; Du, S.; Zhang, H.; Sun, H. Loss calculation and thermal analysis of ultra-high speed permanent magnet motor. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.; Zhi-gang, G.; Jun, Z. Power Loss and Heat Dissipation Characteristics of High-Power Electromechanical Actuators. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 153, 03003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente-Blanco, I.; López-Pascual, D.; Nas, M.A.-C.; Díez-Jiménez, E. Novel Method for the Characterization of the Electrical Conductivity and Eddy Current Damping of Aluminum Foams. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 6003308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ye, W.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, M. A coupled structure-electromagnetism-thermal optimal design method of reluctance actuator in ultra-high acceleration lithography reticle stage. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2025, 68, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertos-Cabanas, M.; Lopez-Pascual, D.; Valiente-Blanco, I.; Villalba-Alumbreros, G.; Fernandez-Munoz, M. A Novel Ultra-Low Power Consumption Electromagnetic Actuator Based on Potential Magnetic Energy: Theoretical and Finite Element Analysis. Actuators 2023, 12, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente-Blanco, I.; López-Pascual, D. High-T c Superconducting Bearings Design: Towards High-Performance Machines. In High-Tc Superconducting Technology; Jenny Stanford Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.