Design and Experimental Verification of a Compact Robot for Large-Curvature Surface Drilling

Abstract

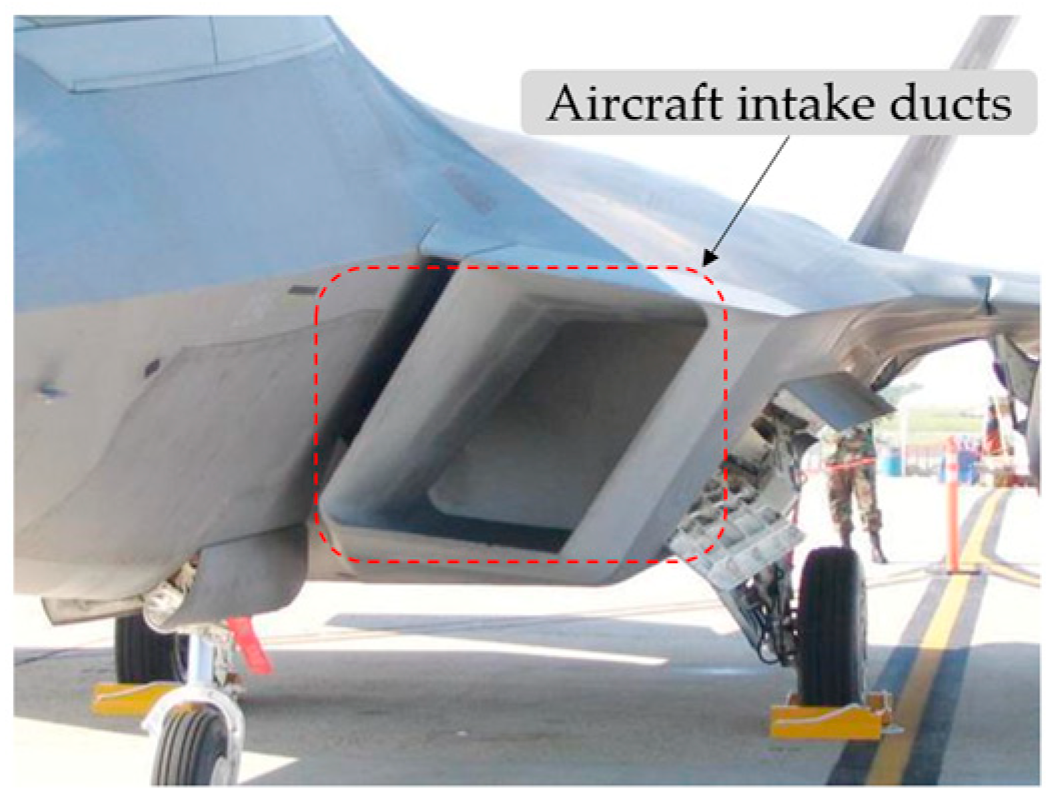

1. Introduction

2. Functional Requirements and Technical Specifications

- (1)

- Compact size: To enable operation within confined spaces and ensure navigation through various scenarios, the robot must possess a compact form factor.

- (2)

- Mobility on large-curvature skins: Given that confined spaces such as air inlets often feature large-curvature surfaces, the robot must achieve omnidirectional movement on skins—particularly enabling flexible traversal across highly curved surfaces—to ensure unobstructed drilling operations.

- (3)

- To achieve high-quality drilling, the robot must ensure precise hole diameter and perpendicularity. Maintaining these tolerances is critical, as any deviation would compromise hole integrity and directly impact aircraft performance.

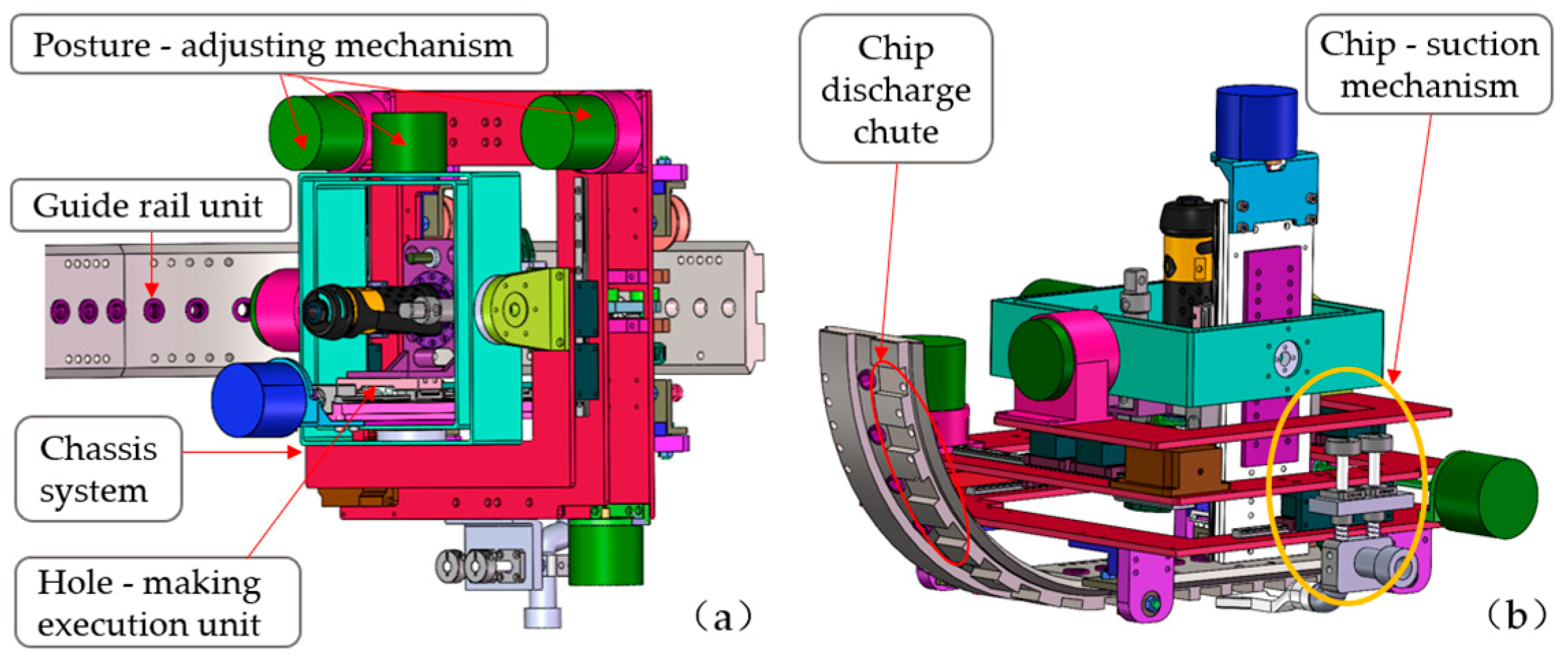

3. Principle Design of the Adaptive Compact Drilling Robot

3.1. Integrated Design of the Adaptive Compact Drilling Robot

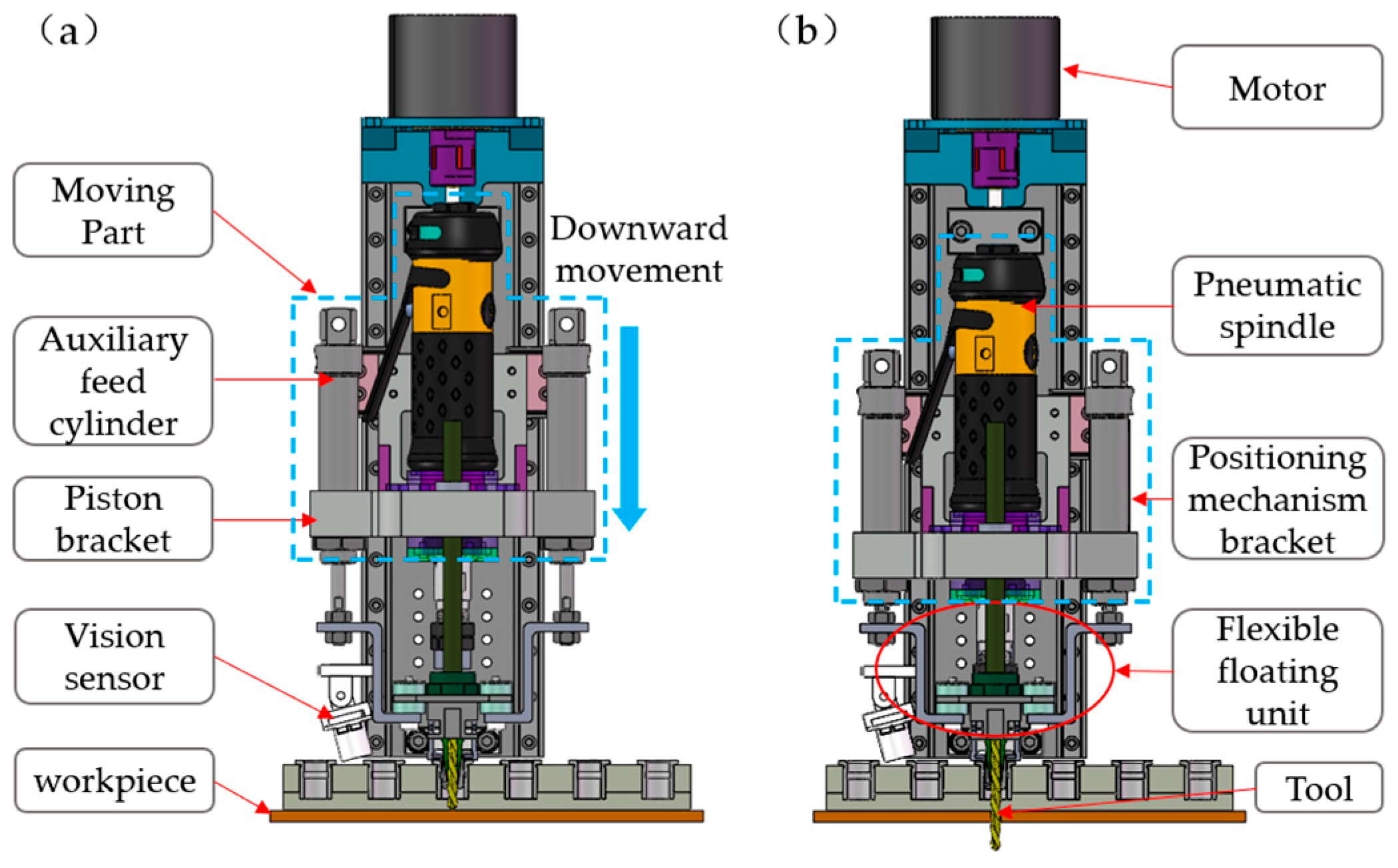

3.2. Drilling Execution Unit

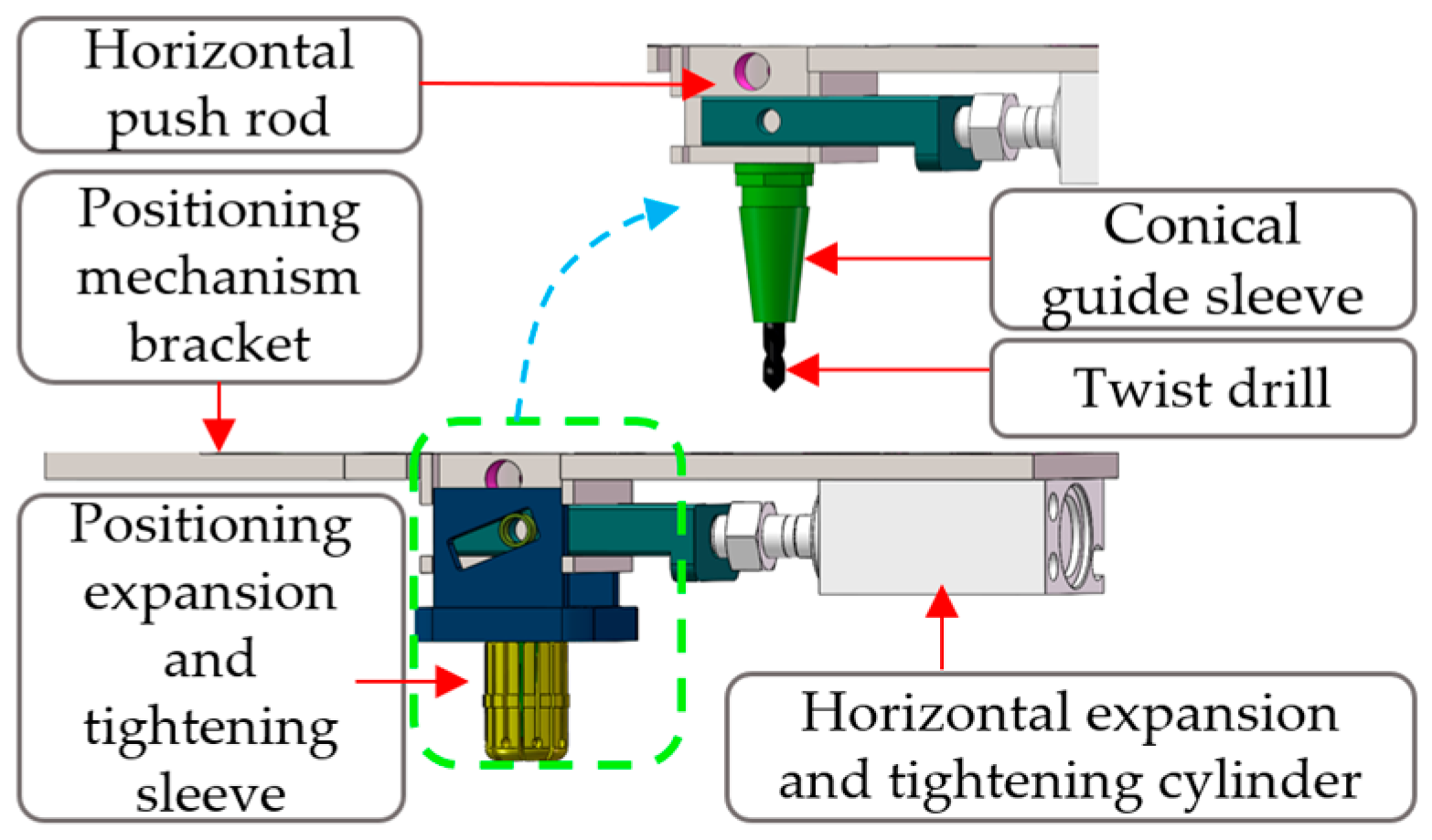

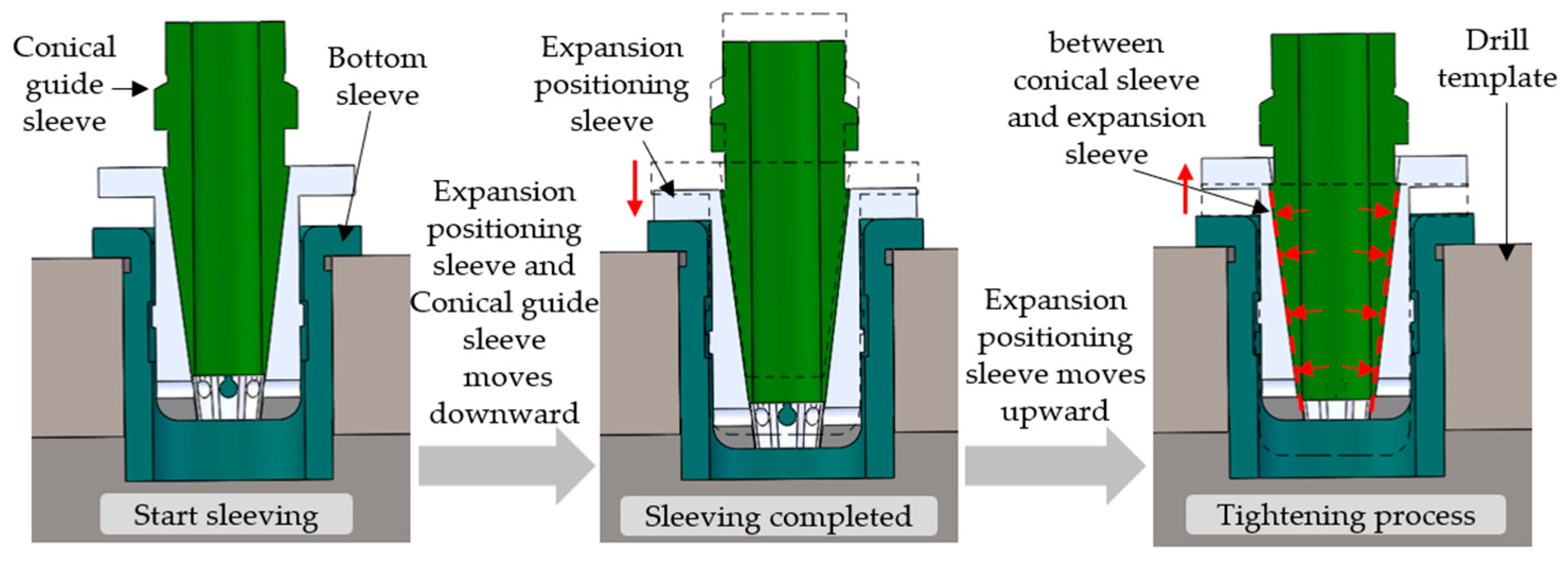

3.3. Expansion Positioning Mechanism Design

- (1)

- Insertion Phase: The flexible floating unit initiates insertion, with the expansion positioning sleeve entering the base sleeve.

- (2)

- Positioning Phase: Once fully inserted, the expansion positioning sleeve reaches its operational position.

- (3)

- Expansion Locking Phase: The horizontal cylinder extends, driving the upward motion of the expansion positioning sleeve. Relative sliding between the tapered guide sleeve and the expansion sleeve induces radial elastic deformation, achieving external and internal bore positioning and clamping with the base sleeve.

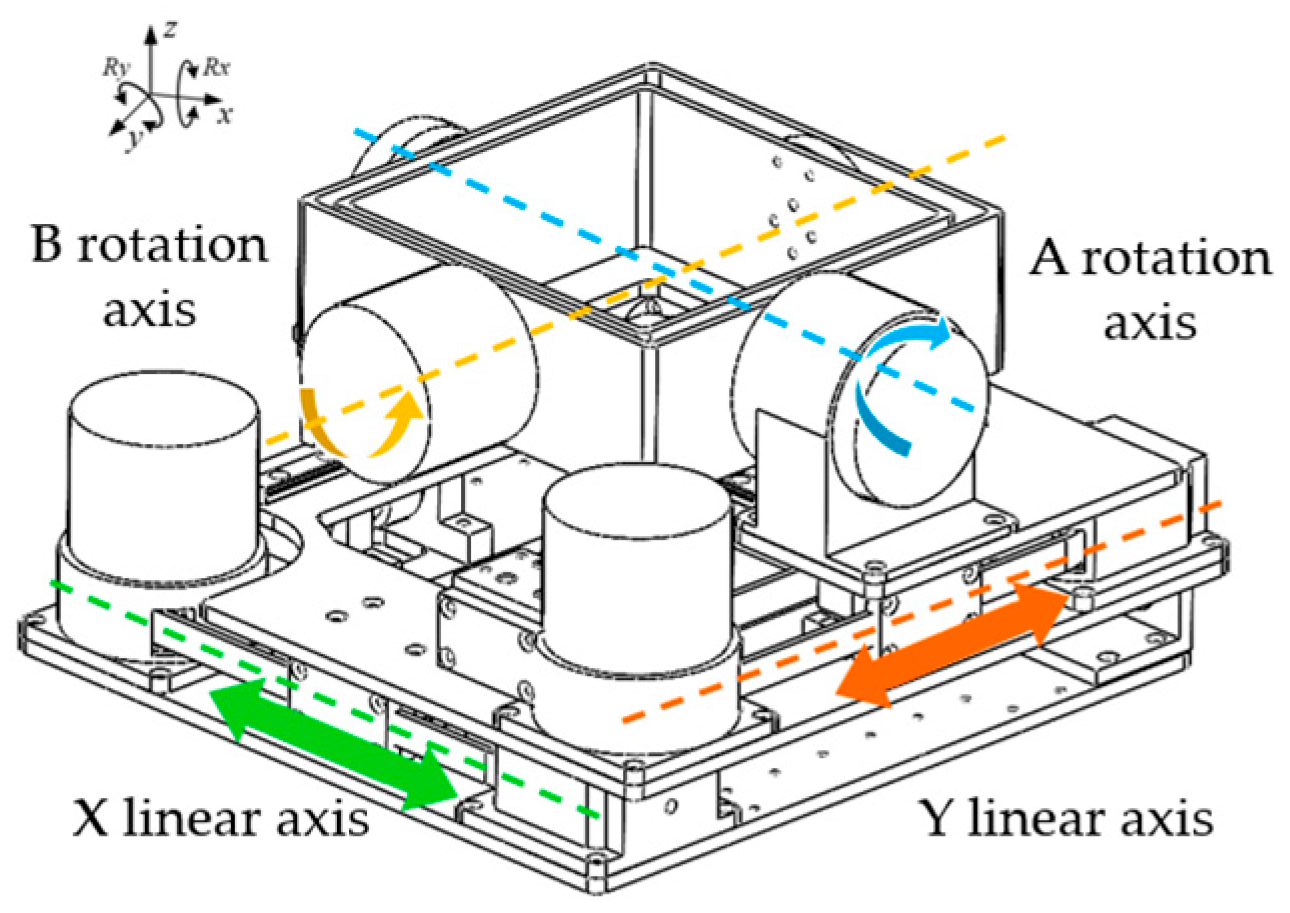

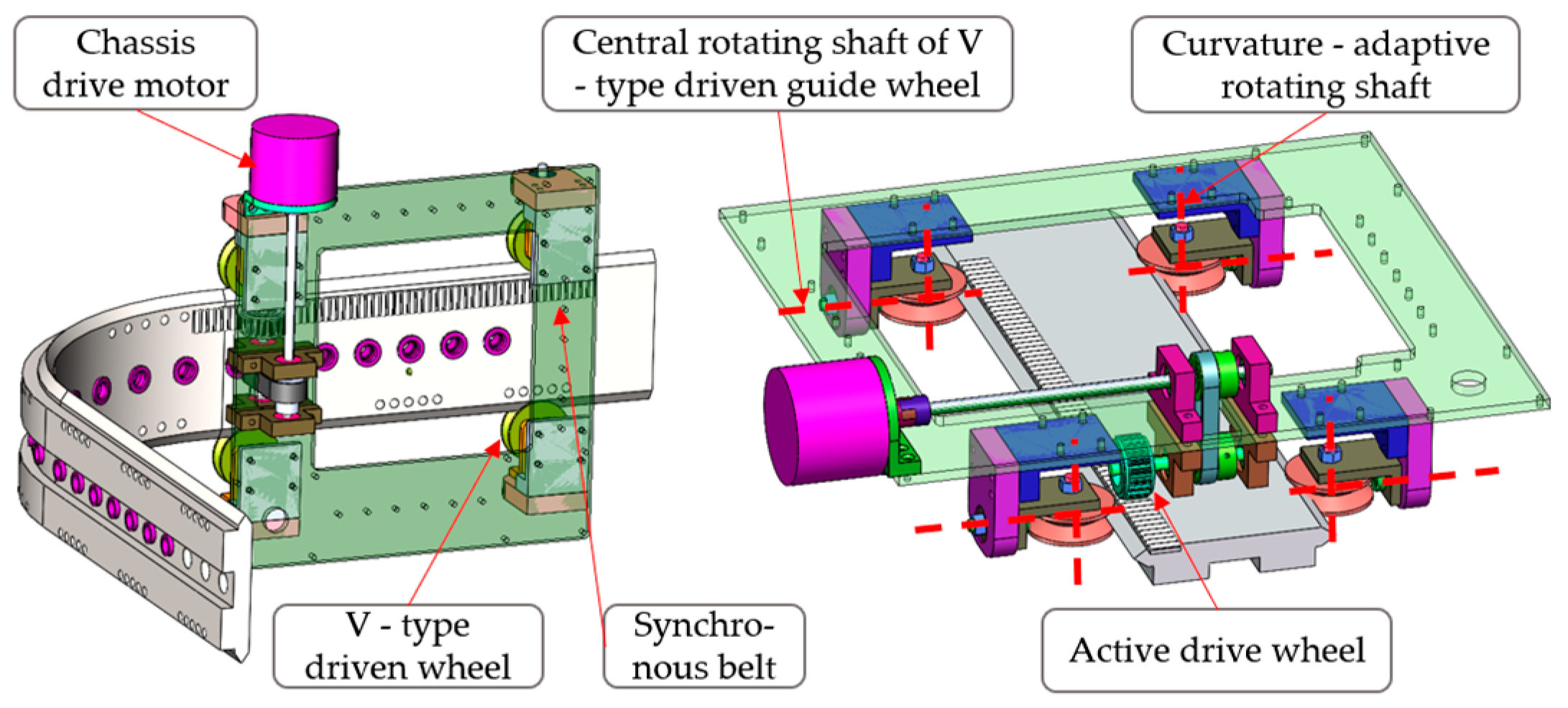

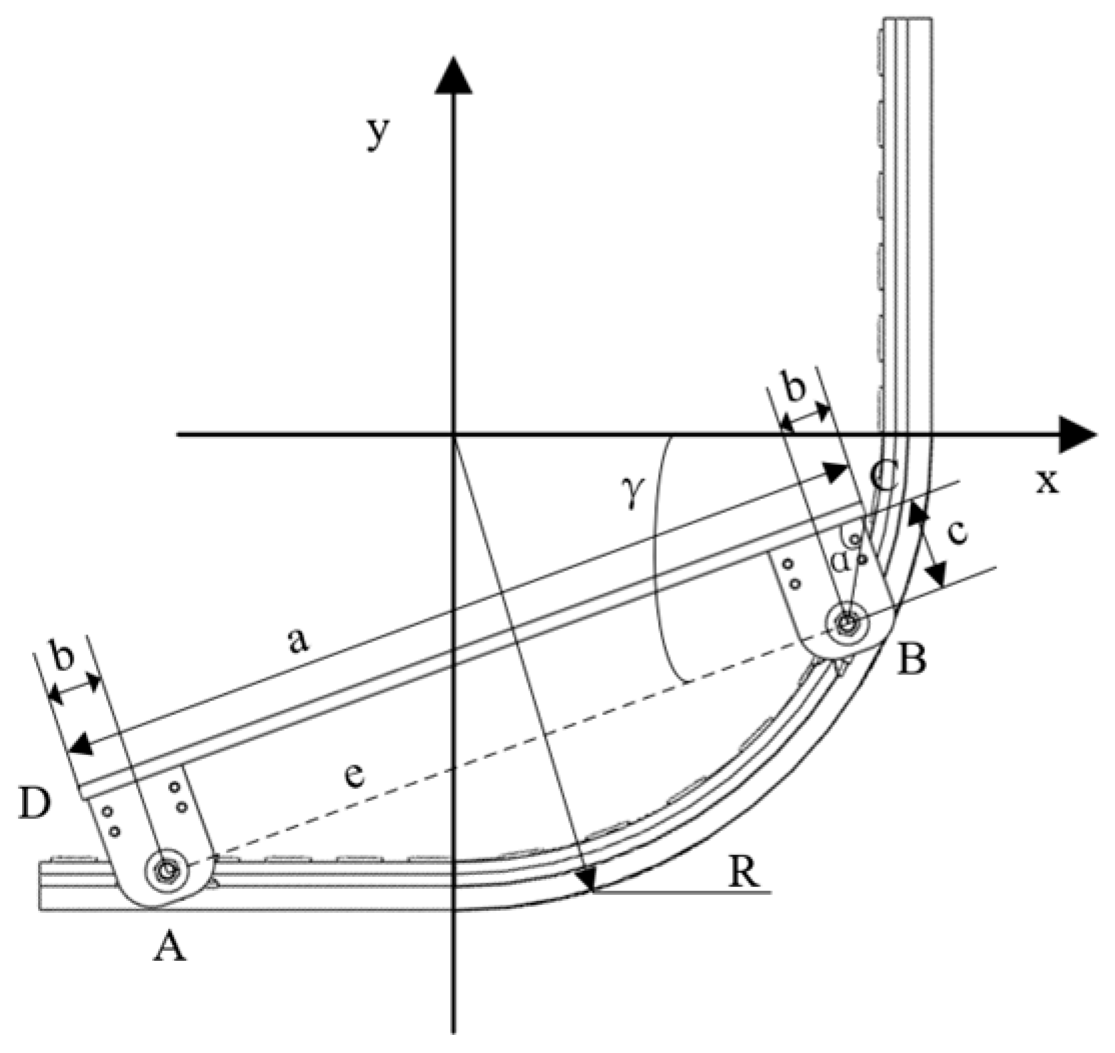

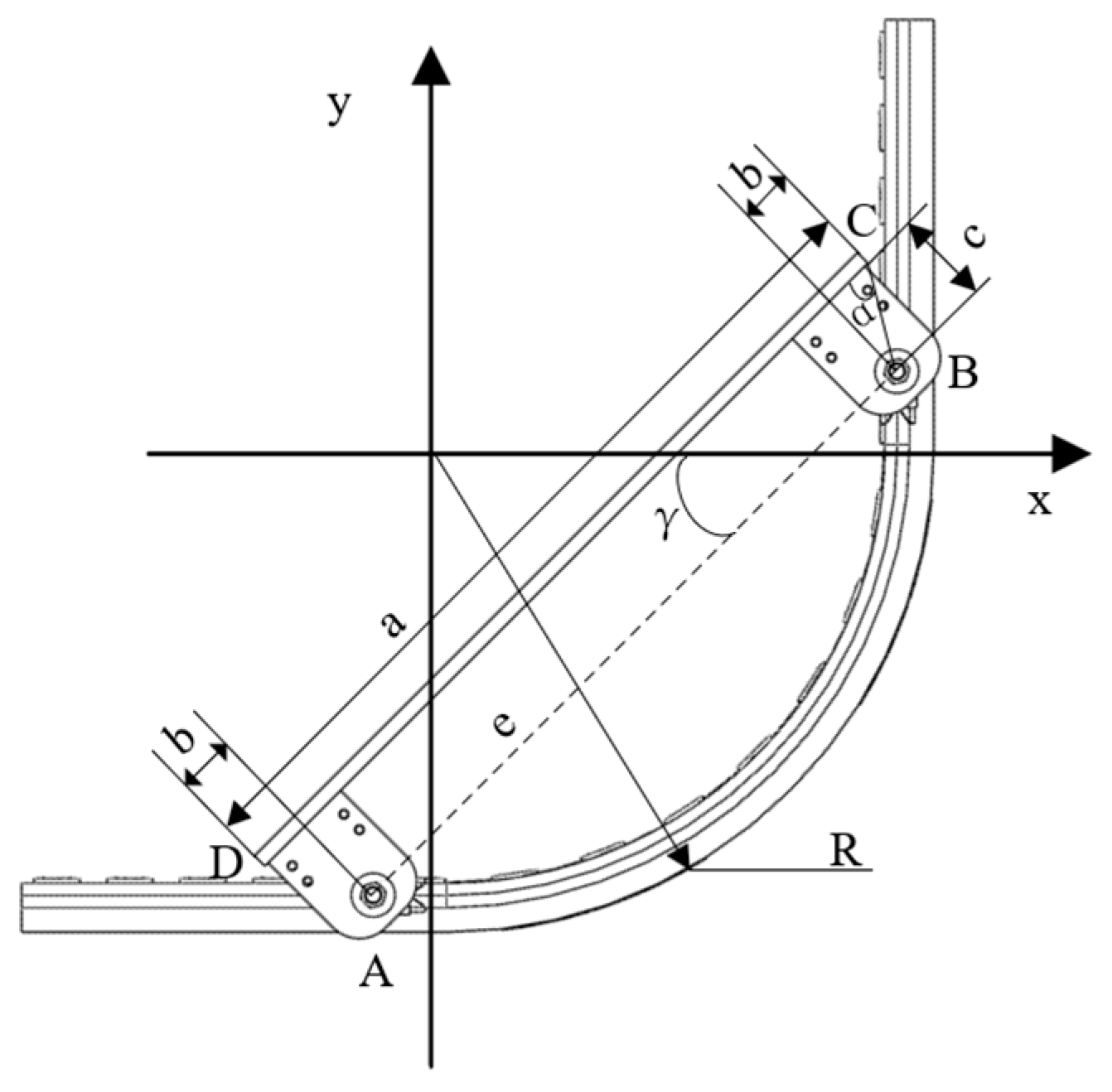

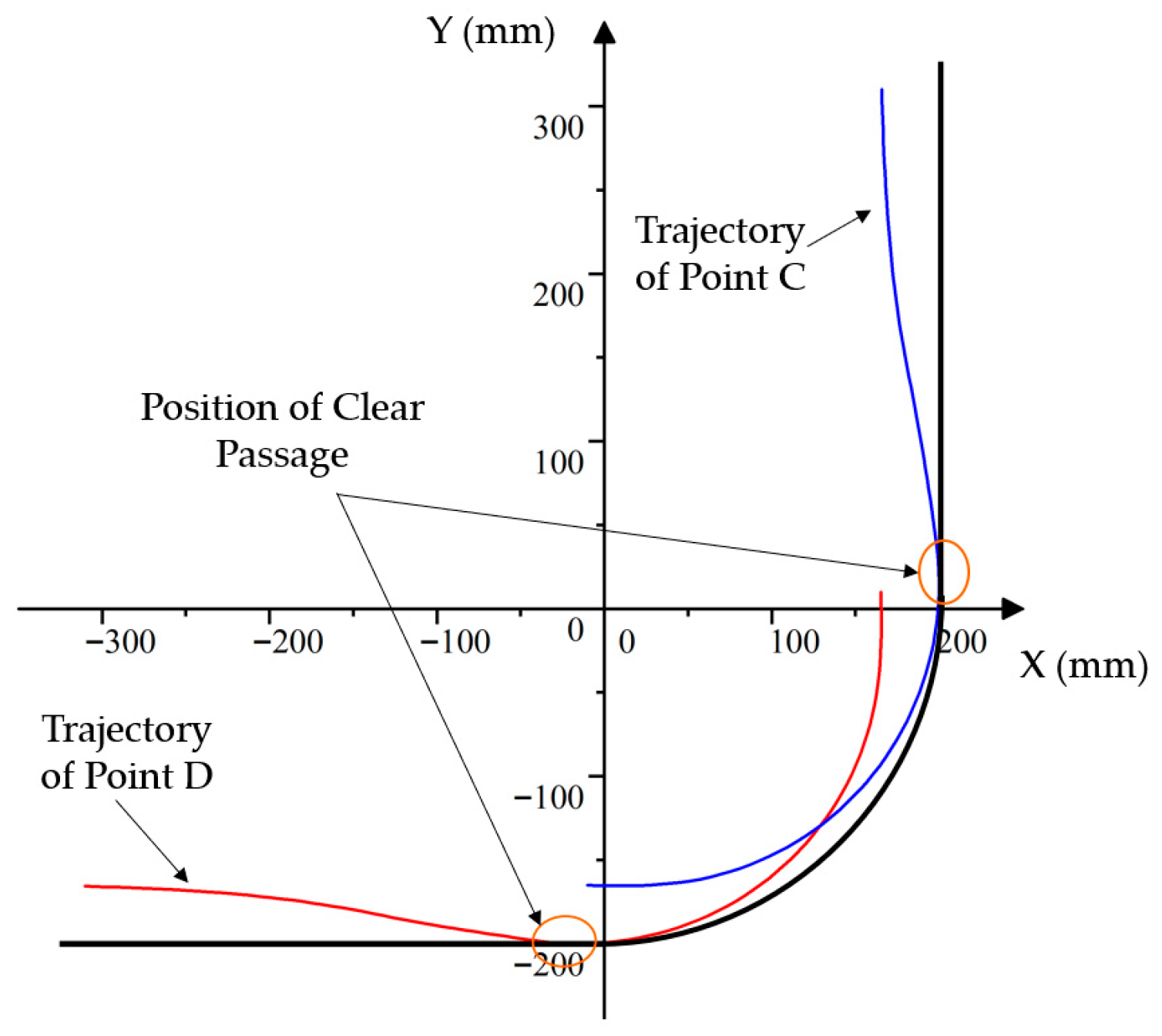

4. Kinematic Analysis of Large-Curvature Surface Adaptive Motion for the Robot Chassis

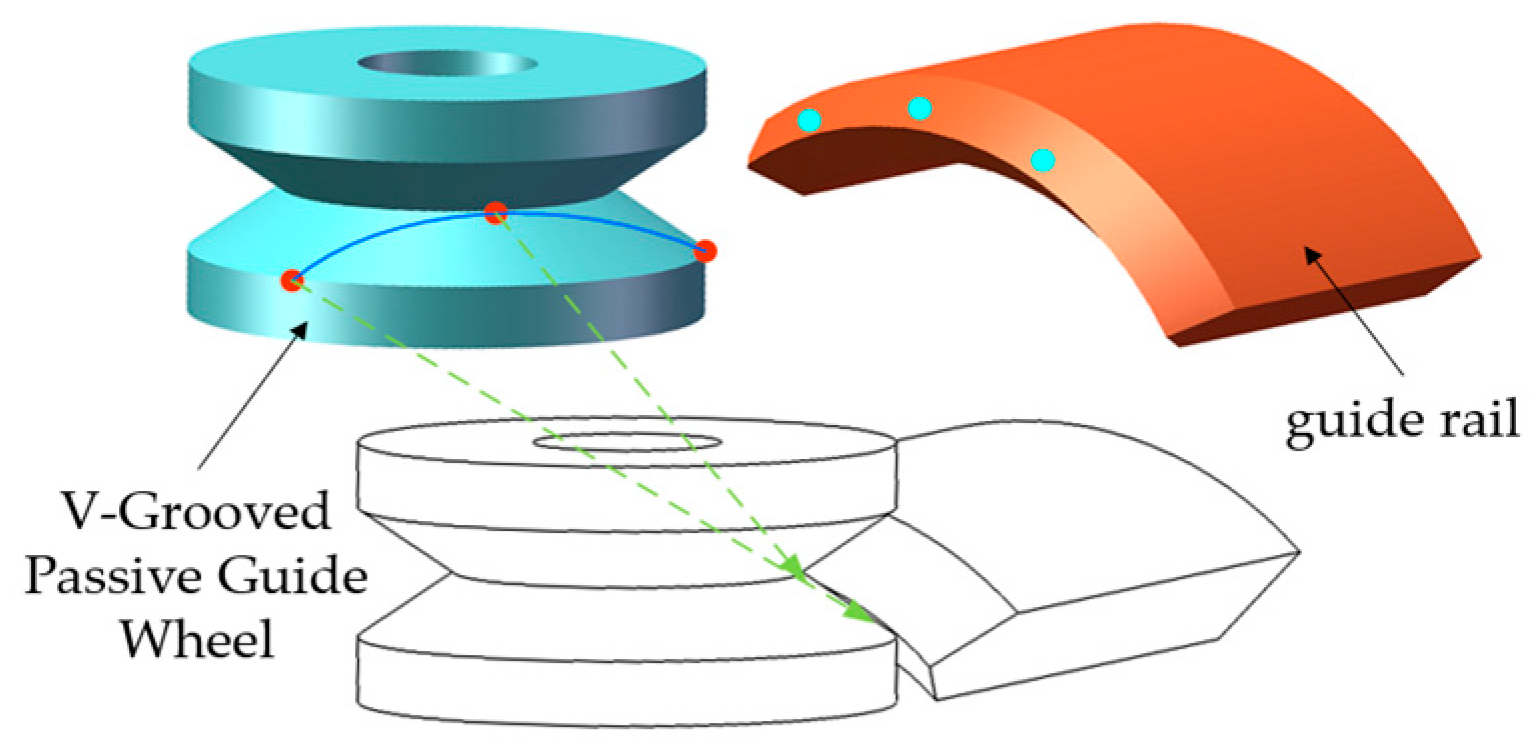

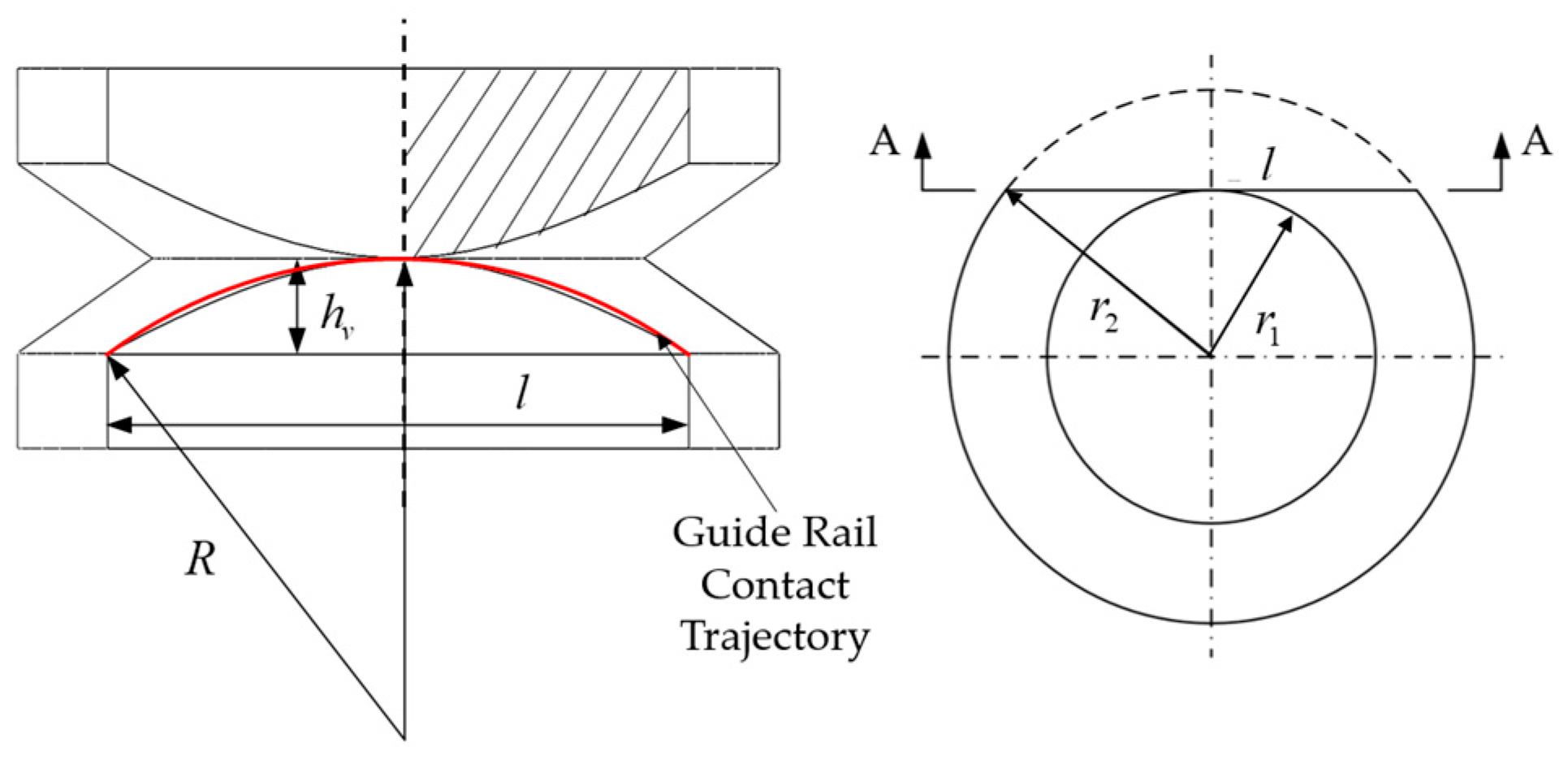

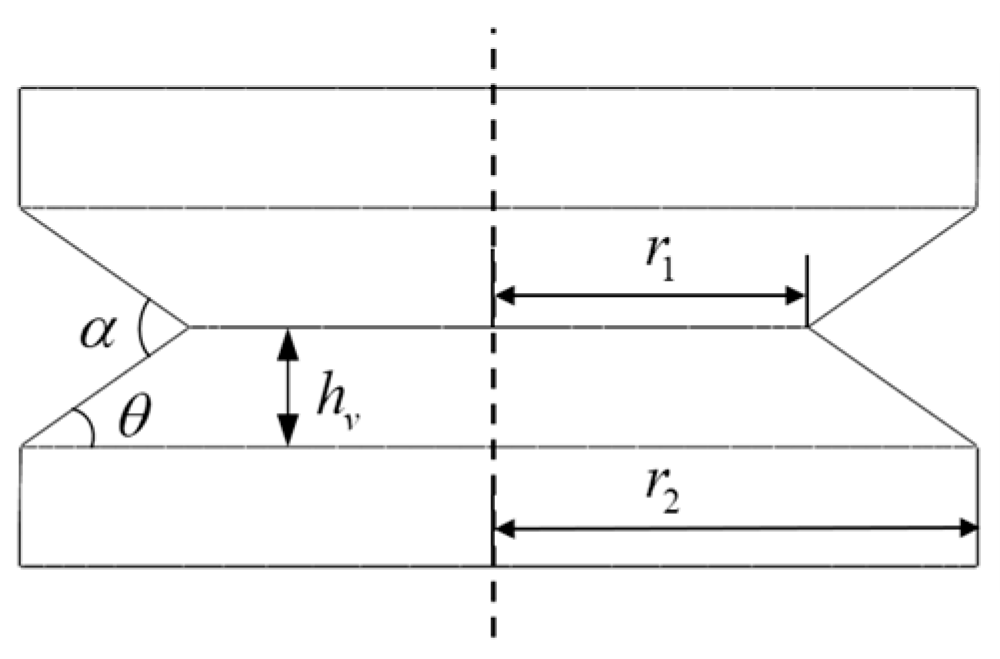

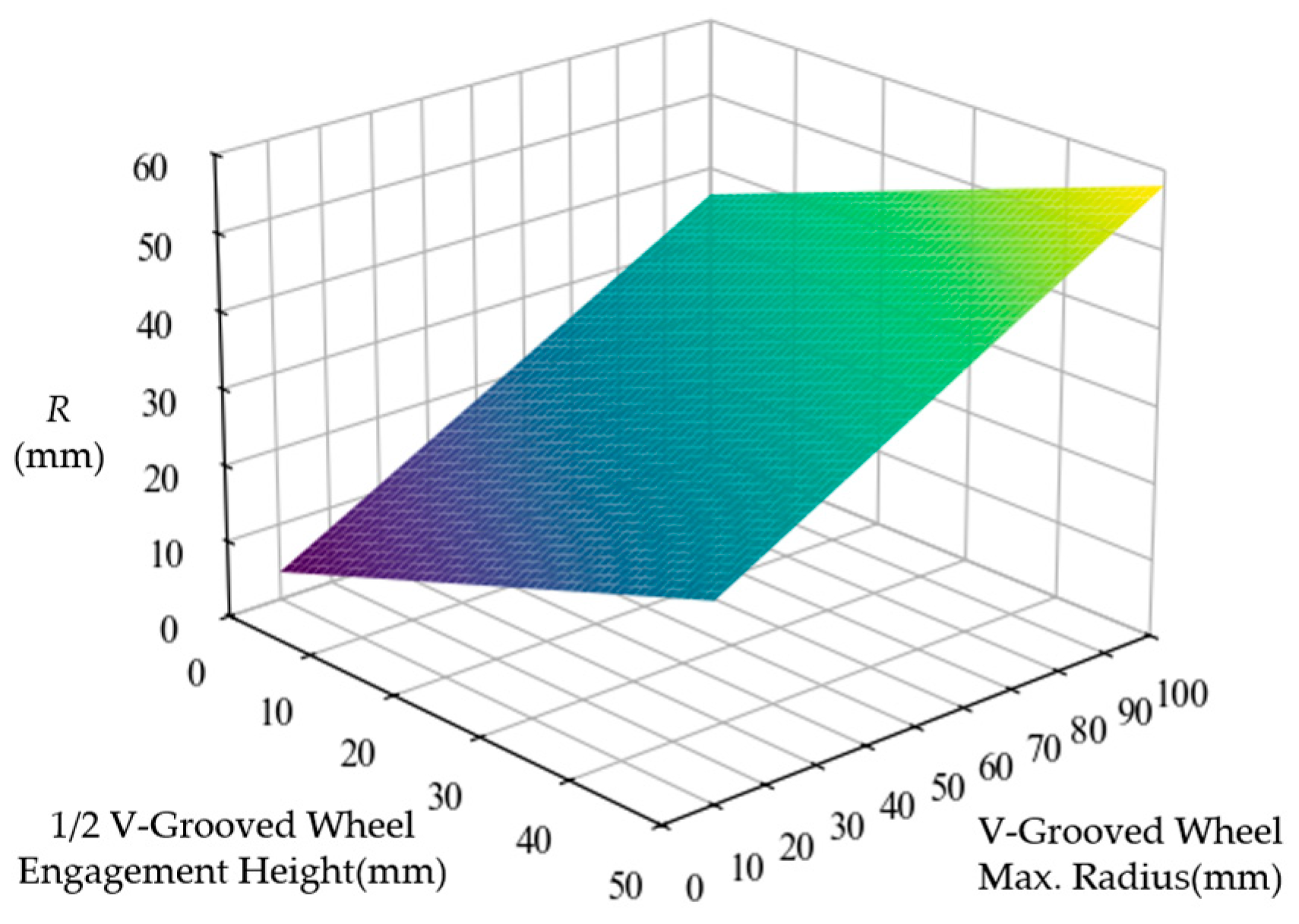

4.1. Guide Wheel Diameter Determinable via Curvature Radius Analysis

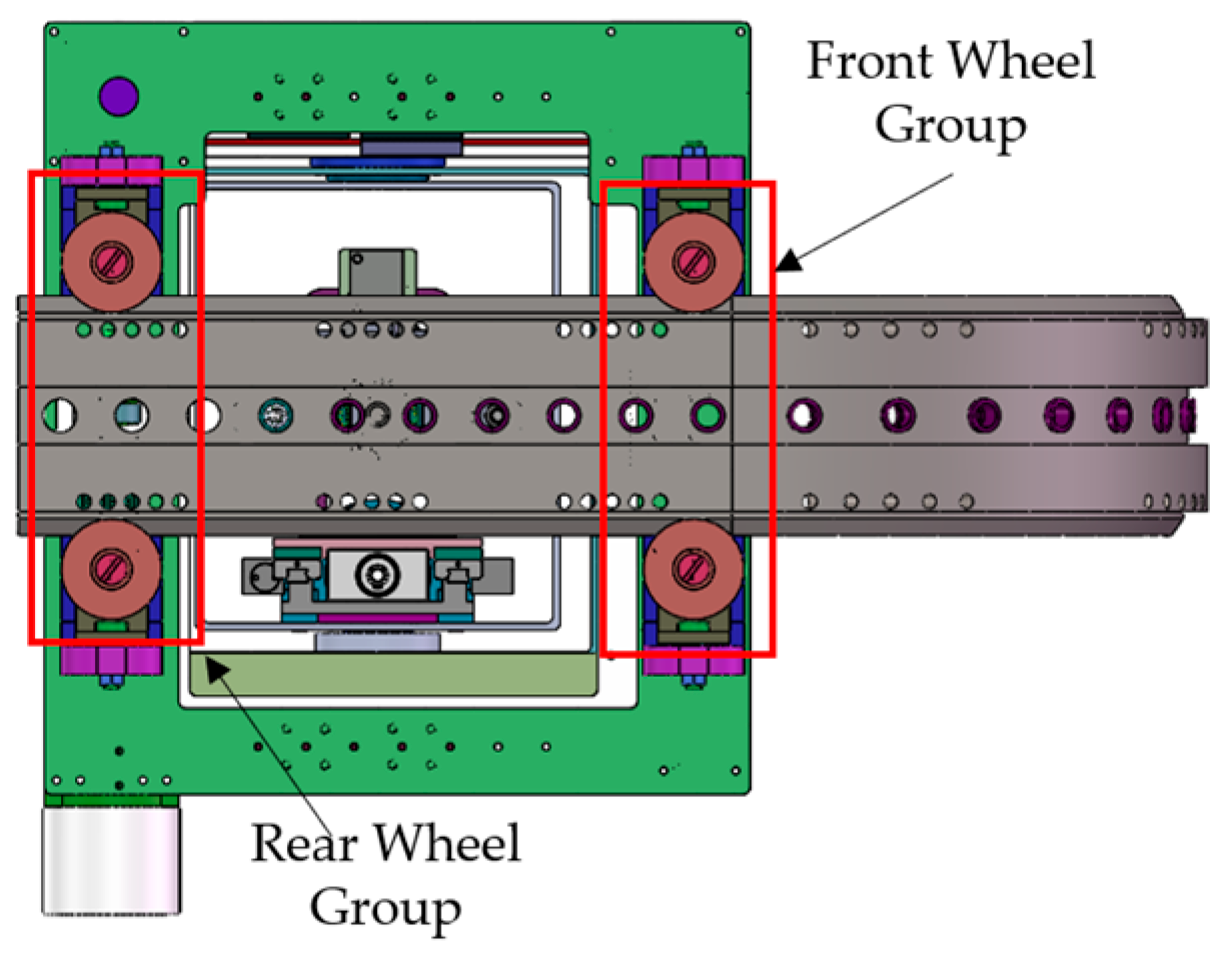

4.2. Traversable Curvature Radius Verification for Robot Chassis

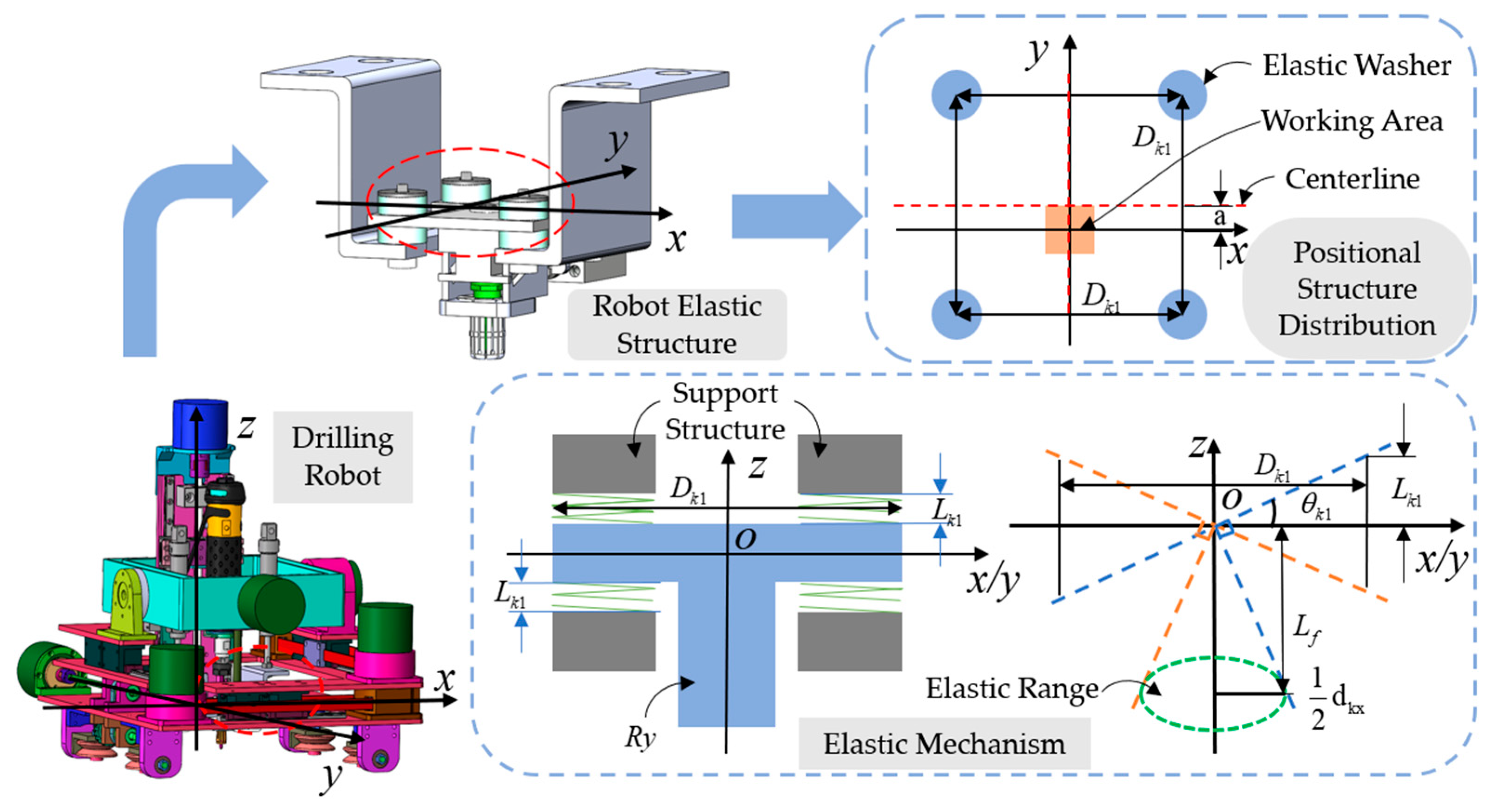

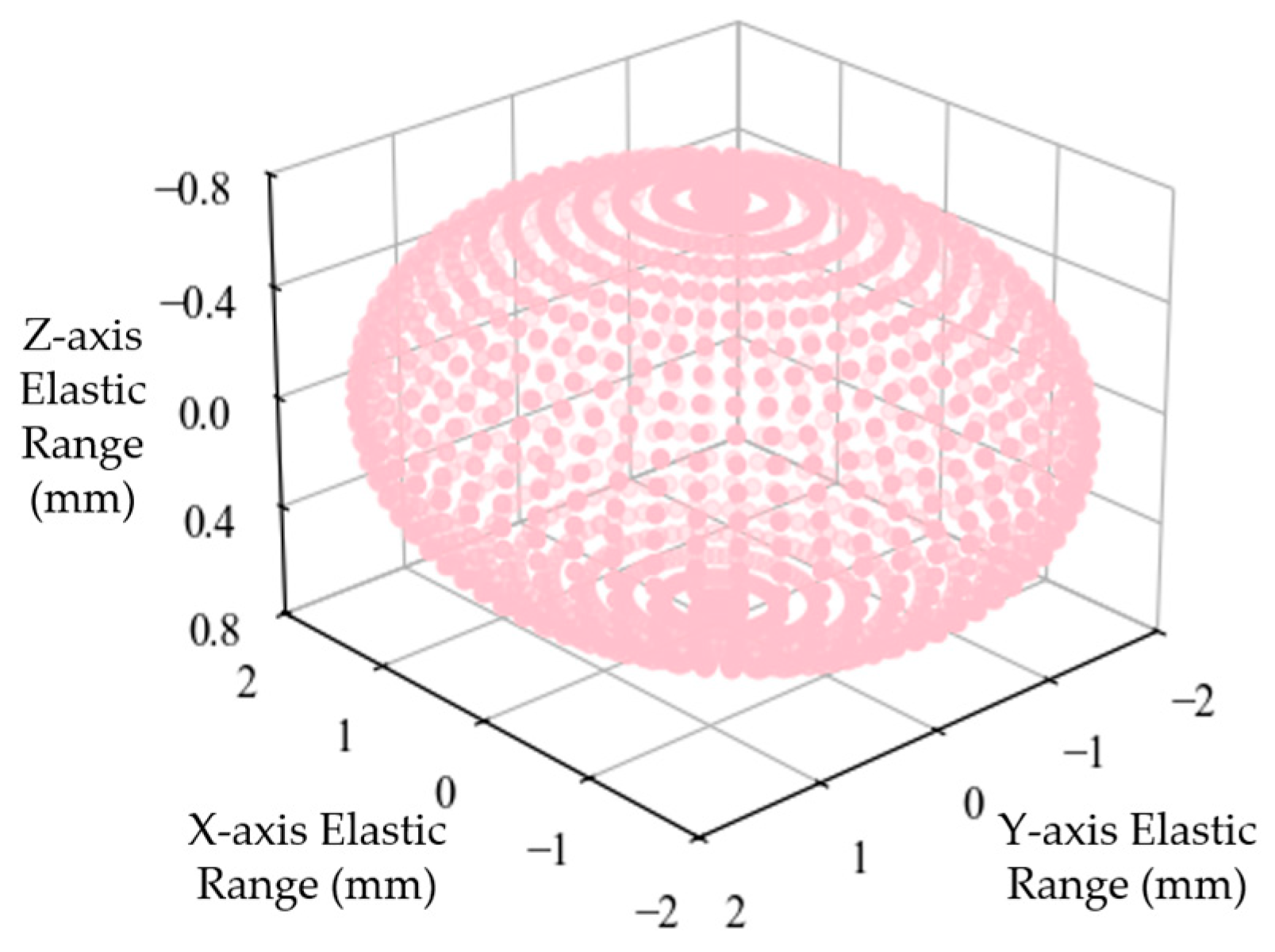

5. Elastic Engagement Kinematics Analysis for Drilling End

- (1)

- In the x-z plane:

- (2)

- In the y-z plane:

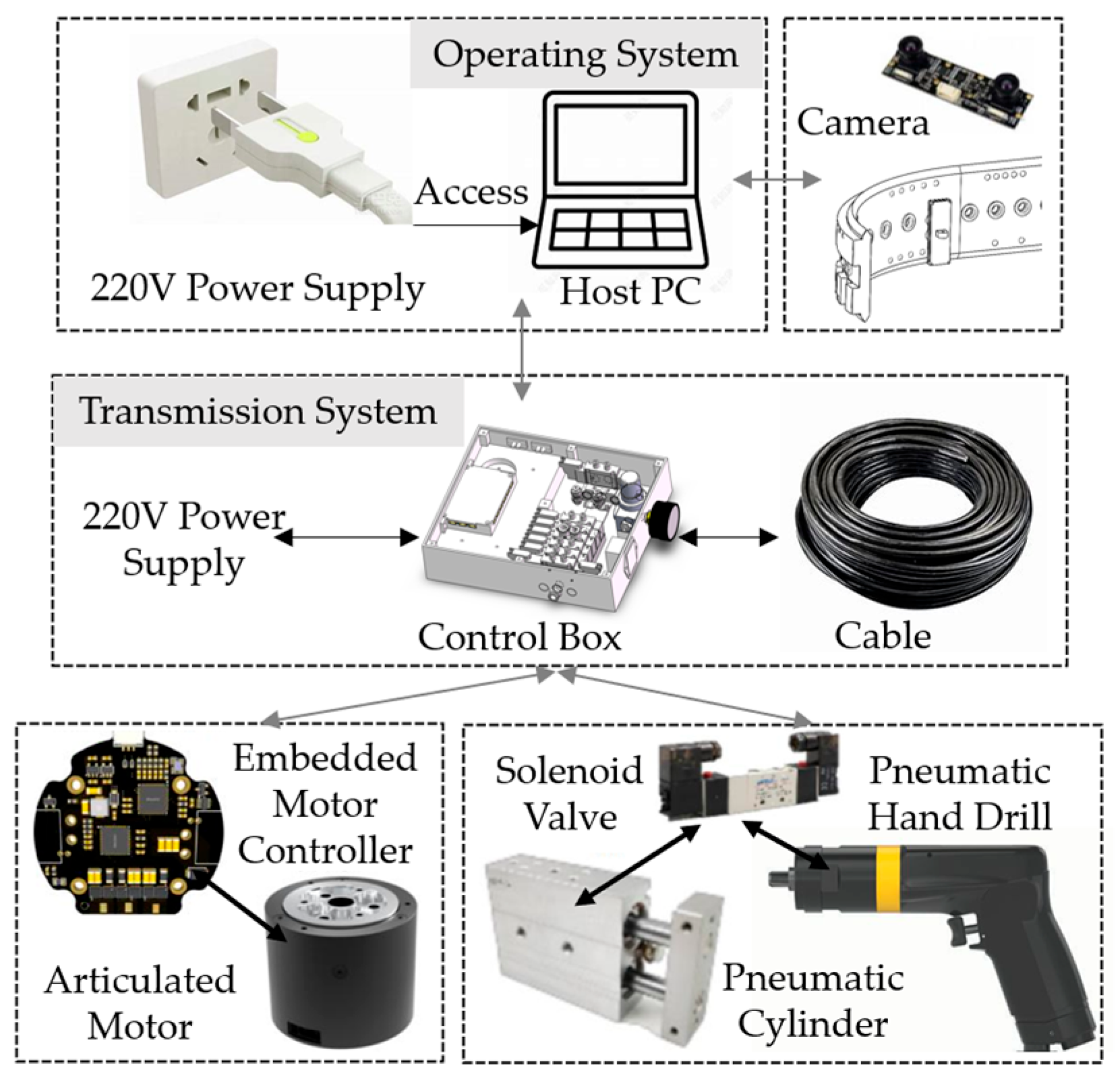

6. Control System Assembly

6.1. Integrated Control System Design

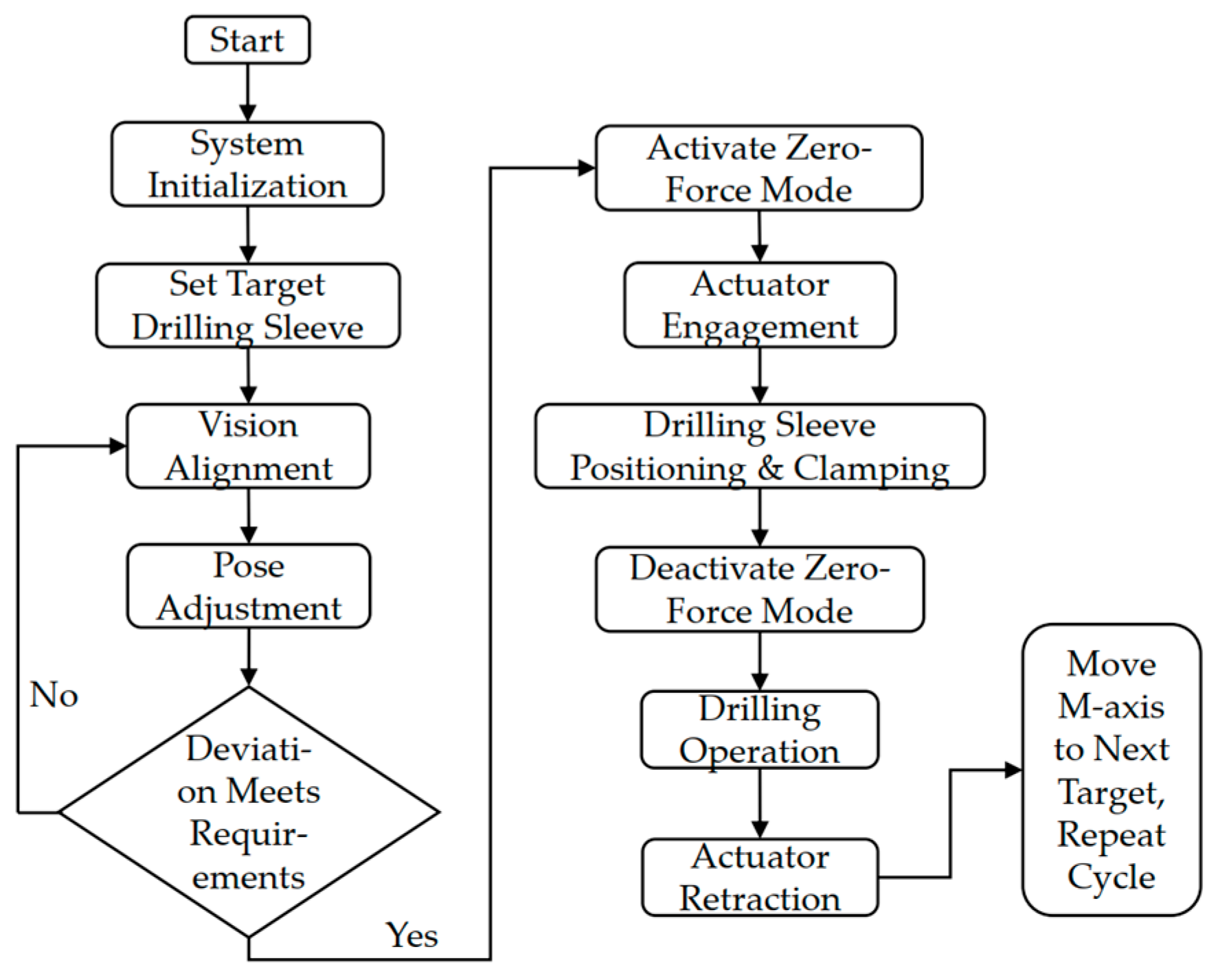

6.2. Wall-Climbing Robot Control Flow Design

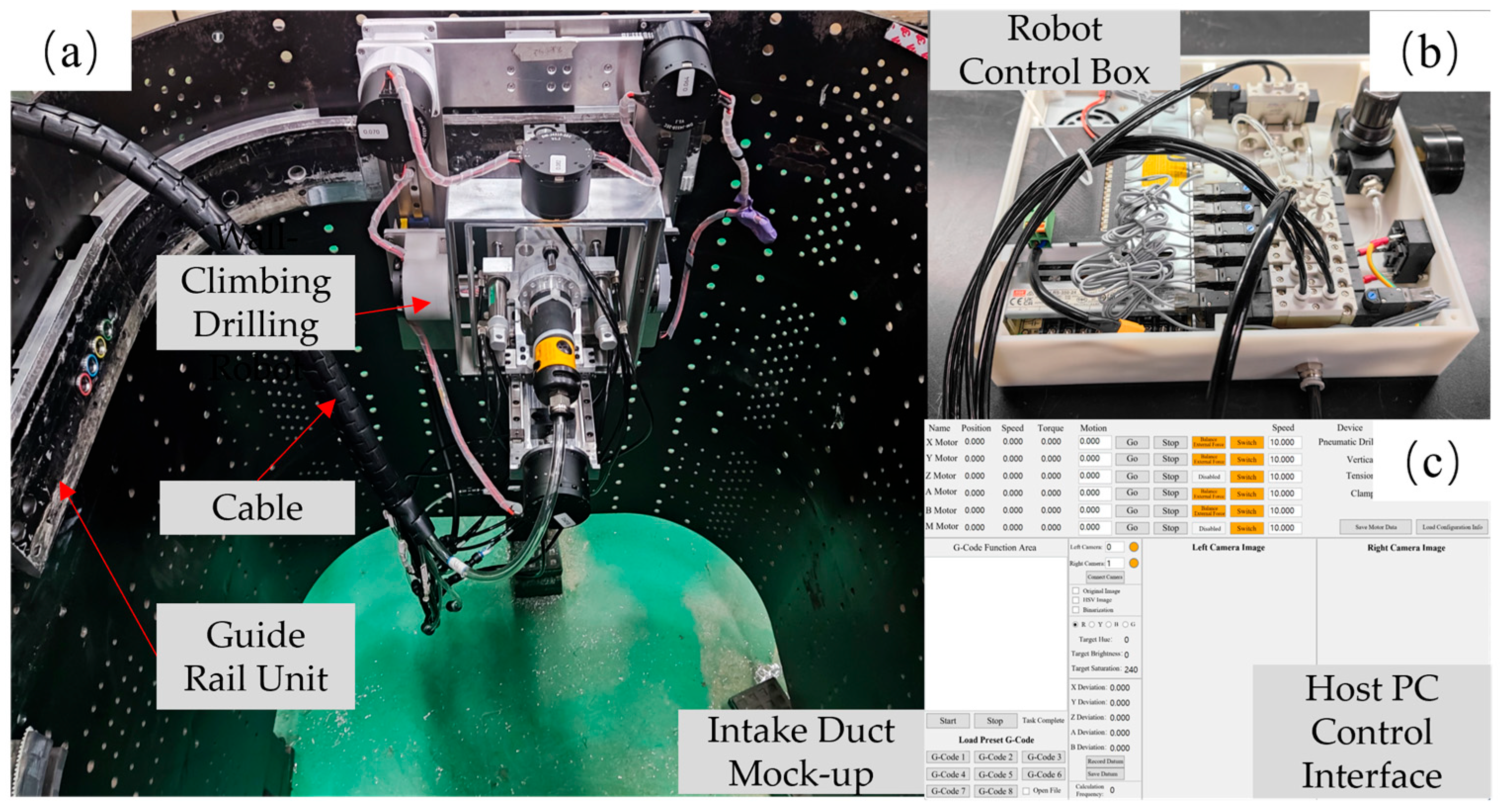

7. Compact Wall-Climbing Robot Experimental Tests

7.1. Traversability Verification Test

7.2. Robot Drilling Capability

8. Conclusions

- (1)

- Compact Design: The developed compact drilling robot, with overall dimensions less than 400 × 400 × 400 mm and a mass under 15 kg, successfully addresses the challenges of spatial accessibility faced by existing industrial robots and traditional drilling equipment.

- (2)

- Large-Curvature Surface Adaptive Mobility: The robot achieves large-curvature surface adaptive mobility through the design of novel actively driven wheels and passive V-grooved guide wheels. Precise calculation of wheel parameters, such as a V-groove angle of 70° and a wheel diameter of 20 mm, enables stable traversal and precise positioning on skins with a minimum curvature radius of R200 mm, overcoming the limitations of commercial drilling robots that are confined to low-curvature, open spaces.

- (3)

- High-Stiffness Precision Drilling Mechanism: The robot’s high-stiffness precision drilling mechanism, verified through experiments, incorporates a floating spindle mechanism that provides an elastic movement range of 0.2 mm in all directions. This ensures that the drill bit enters the guide mechanism with high precision. As a result, closed-loop force transmission between the twist drill and the guide rail is achieved, significantly enhancing machining stiffness and chatter resistance during the drilling process.

- (4)

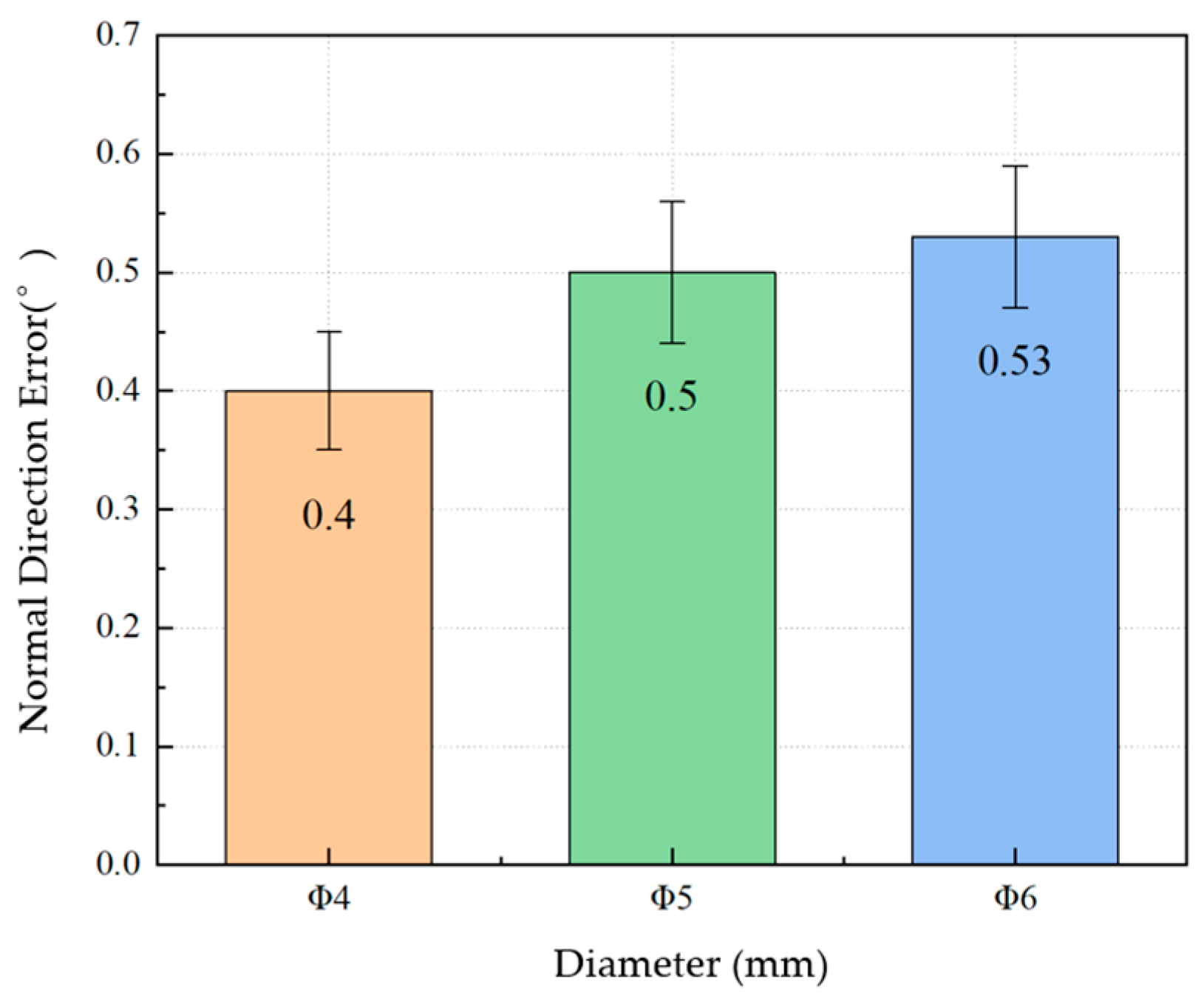

- Experimental Validation: Experimental results demonstrate the robot’s ability to traverse skins with an R200 mm curvature and perform automated drilling of Φ4–Φ6 mm fastener holes in CFRP/7075 aluminum stacks. The dimensional accuracy of the drilled holes was maintained, with size errors of less than 0.05 mm, and normal direction errors of less than 0.65°, meeting the design requirements. The average drilling rate was 2.1 holes per minute, indicating the robot’s satisfactory performance in terms of drilling efficiency.

- (5)

- In the future, we will focus on two key directions: first, developing an intelligent drilling system with autonomous path planning and real-time parameter optimization to enhance intelligence and autonomy; second, conducting long-term reliability tests and exploring multi-robot collaborative operation modes for large-scale components, thereby promoting the engineering application of this technology in automated assembly of complex aerospace structures.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mei, Z.; Maropoulos, P.G. Review of the application of flexible, measurement-assisted assembly technology in aircraft manufacturing. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2014, 228, 1185–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Zhuang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Qin, J. Multimodal perception-fusion-control and human–robot collaboration in manufacturing: A review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 132, 1071–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, C.; Li, C.; Hui, X.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, G. A review of digital twin intelligent assembly technology and application for complex mechanical products. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 127, 4013–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Liu, Y.; Geng, D.; Zhang, D.; Ying, E.; Liu, R.; Jiang, X. Cutting performance and surface integrity during rotary ultrasonic elliptical milling of cast Ni-based superalloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 35, 980–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Jiang, X.; Ying, E.; Sun, Z.; Geng, D.; Zhang, D. High-performance milling of Ti-6Al-4V through rotary ultrasonic elliptical milling with anticlockwise elliptical vibration. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. A 2025, 26, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, D.; Geng, D. Design of a self-excited vibration tool bar for cutting difficult-to-machine alloys. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 300, 110456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Geng, D.; Zheng, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Ying, E.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, D. An innovative study on high-performance milling of carbon fiber reinforced plastic by combining ultrasonic vibration assistance and optimized tool structures. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 22, 2131–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Feng, P.; Yu, D.; Wang, J. Elliptical vibration chiseling: A novel process for texturing ultra-high-aspect-ratio microstructures on the metallic surface. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2024, 6, 025102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.U.; Iqbal, J.; Manzoor, S.; Khalid, A.; Khan, S. An autonomous image-guided robotic system simulating industrial applications. In Proceedings of the 2012 7th International Conference on System of Systems Engineering (SoSE), Genova, Italy, 16–19 July 2012; pp. 344–349. [Google Scholar]

- Russ, D.; Sitton, K.; Feikert, E. Once (One Sided Cell End Effector) Robotic Drilling System; SAE Technical Papers 2002-01-2626; SAE: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Shao, X.J.; Liu, Y.J.; Liu, Y.S.; Yue, Z.F. The effect of holes quality on fatigue life of open hole. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 467, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVlieg, R. Robotic Trailing Edge Flap Drilling System; SAE Technical Papers; SAE: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Frommknecht, A.; Kuehnle, J.; Effenberger, I.; Pidan, S. Multi-sensor measurement system for robotic drilling. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2017, 47, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Liang, F.; Fang, L. Design and performance analysis of an industrial robot arm for robotic drilling process. Ind. Robot. Int. J. Robot. Res. Appl. 2019, 46, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, S.; Liang, J. Robotic drilling system for titanium structures. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2010, 54, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Qin, X.; Bai, J.; Tan, X.; Li, J. Design and Implementation of Multifunctional Automatic Drilling End Effector. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 187, 012032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberoi, H.; Draper, A.; Thompson, P. Production Implementation of a Multi Spindle Flexible Drilling System for Circumferential Splice Drilling Applications on the 777 Airplane; SAE Technical Papers; SAE: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, E. Development of Portable and Flexible Track Positioning System for Aircraft Manufacturing Processes; SAE Technical Papers; SAE: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Marguet, B.; Cibiel, C.; De Francisco, Ó.; Felip, B.; Bernal, J.; Del Pozo, J.; Val, J.; Pujantell, D. Crawler Robots for Drilling and Fastener Installation: An Innovative Breakthrough in Aerospace Automation; SAE Technical Papers; SAE: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Chen, W.; Zhang, D. Light-weight automatic driling system and key technology for aircraft. Aeronaut. Manuf. Technol. 2012, 19, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Liu, J.; Xue, G.; Xu, S. Control Technology of Flexible Track Automatic Drilling Machine. Aeronaut. Manuf. Technol. 2009, 24, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Liu, H.; Yong, B.; Xue, G.; Liu, J. Research on Drilling Experiment of Flexible Track Automatic Drilling Equipment. Assem. Process. 2011, 22, 78–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, F.; Hu, Y.; Yao, Z. Research on PMAC-Based Control System for Flexible Track Drilling Machine. Aeronaut. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 5, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Yuan, P.; Wang, T. The aeronautical drilling robot based on flexible track. In Proceedings of the 32nd Chinese Control Conference, Xi’an, China, 26–28 July 2013; pp. 5728–5733. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, W.; Dong, H.; Ke, Y. An improved kinematic model for serial robot calibration based on local POE formula using position measurement. Ind. Robot. Int. J. 2018, 45, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, R.; Hu, J.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Tian, W. A high-precision digital twin modeling approach for the serial-parallel hybrid drilling robot in aircraft assembly. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2025, 94, 102986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, T.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, X.; Yan, S.; Dai, X.; Ding, H. A review of recent advances in machining techniques of complex surfaces. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2022, 65, 1915–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Sun, N.; Ren, F.; Liu, X.; Guo, W.; Guo, M.; Fan, X.; Zhou, J. Multi-process aerospace components: Residual stress modeling and deformation optimization. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2026, 309, 111077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baizid, K.; Ćuković, S.; Iqbal, J.; Yousnadj, A.; Chellali, R.; Meddahi, A.; Devedžić, G.; Ghionea, I. IRoSim: Industrial Robotics Simulation Design Planning and Optimization platform based on CAD and knowledgeware technologies. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2016, 42, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Geng, D.; Jiang, X.; Xue, J.; Guo, G.; Zhang, D. An innovative normal self-positioning method with gravity and friction compensation for wall-climbing drilling robot in aircraft assembly. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 138, 3687–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Xue, J.; Guo, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhang, D. Stiffness Optimization of a Robotic Drilling System for Enhanced Accuracy in Aerospace Assembly. Actuators 2025, 14, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Requirement |

|---|---|

| Dimensions (L × W × H, mm) | ≤400 × 400 × 400 |

| Robot Mass (kg) | ≤15 |

| Drilling Diameter Range (mm) | ≥Φ4 |

| Min. Traversable Curvature Radius (mm) | R200 |

| Drilling Normal Direction Error (°) | ≤1 |

| Drilling Efficiency (holes quantity/min) | ≥2 |

| Parameter | Requirement |

|---|---|

| V-Groove Angle (°) | 70 |

| Half-Height of V-Grooved Wheel (mm) | 5 |

| Radius of V-Grooved Wheel (mm) | 20 |

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Dimensions (Length/mm × Width/mm × Height/mm) | 386 × 317 × 312.5 |

| Robot Mass (kg) | 13.2 |

| Parameter | Numerical Value |

|---|---|

| Drilling Diameter (mm) | 4.0/5.0/6.0 |

| Drilling Depth (mm) | 7 |

| Spindle Speed (rpm) | 3200 |

| Feed Speed (mm/r) | 0.25 |

| Parameter | Numerical Value |

|---|---|

| Drilling Diameter (mm) | 4/5/6 |

| Drilling Depth (mm) | 100 |

| Spindle Speed (rpm) | 118 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ren, S.; Li, X.; Geng, D.; Sun, Z.; Xu, H.; Fu, J.; Zhang, D. Design and Experimental Verification of a Compact Robot for Large-Curvature Surface Drilling. Actuators 2026, 15, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010024

Ren S, Li X, Geng D, Sun Z, Xu H, Fu J, Zhang D. Design and Experimental Verification of a Compact Robot for Large-Curvature Surface Drilling. Actuators. 2026; 15(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Shaolei, Xun Li, Daxi Geng, Zhefei Sun, Haiyang Xu, Jianchao Fu, and Deyuan Zhang. 2026. "Design and Experimental Verification of a Compact Robot for Large-Curvature Surface Drilling" Actuators 15, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010024

APA StyleRen, S., Li, X., Geng, D., Sun, Z., Xu, H., Fu, J., & Zhang, D. (2026). Design and Experimental Verification of a Compact Robot for Large-Curvature Surface Drilling. Actuators, 15(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010024