Abstract

Robot-assisted gastrointestinal endoscopic surgery (RAGES) has emerged as a critical approach for minimally invasive procedures, including Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection, polypectomy, hemostasis, and therapeutic interventions. However, manual manipulation of flexible endoscopes remains technically demanding and limits surgical precision. To enhance surgical efficiency, this paper proposes a joystick-controlled Endoscopic Robotic System (ERS) comprising a Flexible Arm Delivery Device (FDD) and Main Body Driving Device (MDD). Through systematic structural design and validation, the ERS achieves stable four-DOF control: 360° circumferential rotation, 180° bending, 280–330 mm axial delivery, and ±15° rotational compensation. Key innovations include dual-encoder slippage detection in the FDD and a gripper assembly addressing circumferential angle loss through real-time torque sensing. Experimental results confirm compatibility with dual-channel endoscopes without custom modifications. The system demonstrates proof-of-concept for comprehensive endoscopic control while maintaining compact design (<0.2 m2 per module) and low manufacturing cost. Although force-sensing capabilities require further refinement, this work establishes a foundation for accessible robotic platforms in gastrointestinal endoscopy, with identified limitations guiding future development toward clinical viability.

1. Introduction

Minimally Invasive Surgery (MIS) has revolutionized early-stage gastrointestinal tumor treatment, with flexible endoscopy as a cornerstone of organ-preserving interventions. Early detection of mucosal-layer tumors—enabled by widespread screening—eliminates the need for invasive laparoscopic resection, allowing complete tumor removal via natural orifices.

Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection (ESD) represents the pinnacle of this evolution, offering en bloc resection to preserve organ integrity [1,2]. Inserted orally (upper tract: esophagus, stomach, duodenum) or transanally (lower tract: colon, rectum), ESD achieves true “incisionless” surgery. However, its adoption lags in Western healthcare systems, creating disparities in access for patients with early-stage gastrointestinal malignancies [3].

The primary barrier to broader ESD use is technical complexity: the procedure demands exceptional manual dexterity to manipulate slender, limited-DOF instruments in confined spaces, requiring extensive training for proficiency [4,5,6]. These challenges have driven the development of robotic-assisted gastrointestinal endoscopic surgery (RAGES) systems, which aim to augment human capabilities and reduce the learning curve.

Current RAGES platforms address these issues through diverse designs, yet each has distinct limitations. The University of Twente’s system retrofits conventional endoscopes with motorized tip control but requires manual axial insertion. It is compatible with at least one type of commercial endoscope, though difficult to expand to others [7]. Yanpei et al.’s foot-controlled system offers pitch, yaw, rotation, and telescoping DOFs but has axial space limitations and difficult assembly [8]. The STRAS v2 system from the University of Strasbourg achieves four degrees of freedom (pitch, yaw, rotation, and telescoping) with comprehensive functionality but suffers from a substantial footprint (at least > 0.5 m2) and relies on trolley-based movement for axial positioning—resulting in cumbersome human–robot collaboration. Notably, this system—like Sivananthan et al.’s design (which struggles to achieve compatibility with commercial endoscopes [9])—is not compatible with such devices, further limiting its clinical application [10,11]. Basha et al.’s universal drive system enables rapid assembly (∼1 min) and 5-DOF control but depends on external robotic arms (e.g., UR5e), limiting clinical practicality [12]. Nakadate’s standalone system supports multi-DOF control and efficient assembly, yet axial insertion remains manual [13].

A thorough analysis of existing systems identifies fundamental design trade-offs: many platforms sacrifice full DOF automation (requiring manual control of axial translation or circumferential rotation), which complicates human–robot interaction and increases operational difficulty [7,14,15,16]. Systems with comprehensive DOF control often use rigid endoscopes or auxiliary robotic arms, limiting applicability in standard clinical settings [12,17,18,19]. While some modular designs address multi-DOF needs [9,20,21,22], few balance compactness, assembly efficiency, and universal compatibility. Horizontal endoscope mounting fundamentally constrains miniaturization [10,23]; suspended architectures offer a solution by decoupling axial movement from system translation but require dedicated delivery modules [11,13]. Alternative systems like Medrobotics’ Flex—using continuous bending segments—gain flexibility but lose reach, making them unsuitable for deep gastrointestinal procedures [24,25,26,27].

To address these challenges—operational complexity, compatibility constraints, footprint limitations, and assembly inefficiency—this study presents a novel Endoscopic Robotic System (ERS) with a suspended endoscope architecture (key comparison with existing systems in Table 1). The ERS comprises the two following modules. A Main Body Driving Device (MDD): Suspended configuration for 3-DOF control (pitching, yawing, and primary body rotation). A Flexible Arm Delivery Device (FDD): Friction wheel assemblies for axial delivery and gripper assemblies for rotational compensation.

Table 1.

Comparison of flexible endoscope robotic systems.

Design priorities include the following: (1) full 4-DOF automation (no manual intervention); (2) compatibility with standard dual-channel endoscopes (e.g., GS-600DQ) without modifications; (3) compact footprint (<0.2 m2 per module); and (4) tool-free rapid assembly via snap-fit mechanisms. Integrating adaptive clamping, dual-encoder slip detection, and torque-sensing compensation, the ERS addresses critical gaps in RAGES—aiming to lower barriers to high-quality ESD and democratize access across healthcare settings.

2. Materials and Method

2.1. System Architecture and Design Requirements

For RAGES procedures, the system design must address diverse procedural requirements across endoscopic interventions, enabling researchers and engineers to meet clinical needs. A formal requirements specification report will be drafted upon completion of this phase, with key considerations including the following:

- 1

- The system shall enable the precise control of endoscope tip pitching (up–down) and yawing (left–right), ensuring accurate adjustment of the surgical field during interventions like ESD, polypectomy, and hemostasis.

- 2

- The system shall provide axial insertion/retraction and circumferential rotation, enabling stable access to the operative site and full four-DOF manipulation across anatomical regions (esophagus, stomach, duodenum, colon, and rectum).

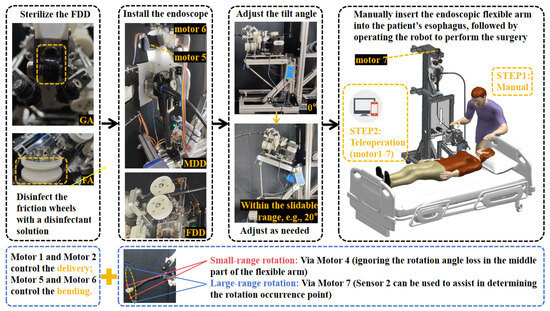

A complete list of all abbreviated terms used in this manuscript is provided in Table 2. To meet these requirements, this work introduces a novel Endoscopic Robotic System (ERS), as shown in Figure 1. The system consists of the Main Body Driving Device (MDD) and Flexible Arm Delivery Device (FDD), which coordinate to achieve full four-DOF control. The MDD—designed on a pulley-equipped hanger—fixes the endoscope main body and occupies < 0.2 m2. The FDD, mounted on an adjustable-inclination support, handles axial delivery and rotational compensation (functions the MDD cannot fully cover). This system is compatible with standard dual-channel electronic endoscopes (e.g., GS-600DQ, Beijing Lepu Zhiying Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) without customization.

Table 2.

Abbreviations and their full forms.

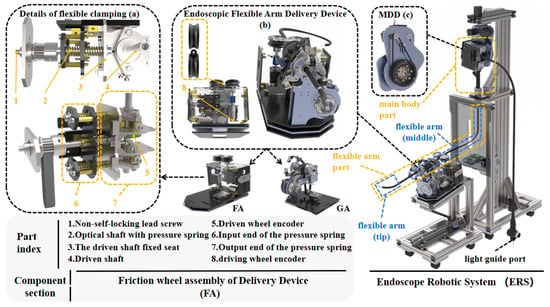

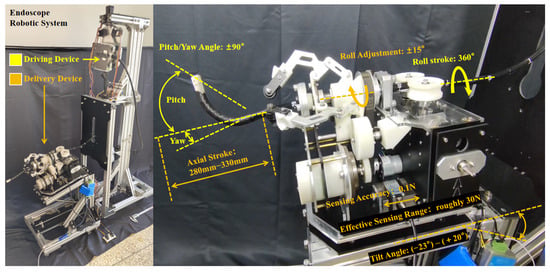

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed ERS and FA details: (a) flexible clamping details; (b) FDD overall structure; (c) MDD diagram.

2.2. System Specification Summary

The key specifications and performance metrics of the ERS are summarized in Table 3, with parameters based on this study’s laboratory data.

Table 3.

Summary of ERS design specifications and performance.

2.3. Main Body Driving Device (MDD)

Conventionally, endoscopists manually control the patient-side endoscope via built-in knobs while assisting surgeons with robotic systems—an approach adopted by systems like MASTER [28] and Via-Cath [29]. In contrast, the proposed MDD drives two dial wheels and the endoscope body via three motors, controlling three DOFs: pitching, yawing, and primary body rotation.

Suspending the endoscope main body reduces the system’s footprint. Horizontally arranged endoscopes require large strokes or manual intervention for axial delivery, but vertically suspended endoscopes allow a single lateral device to handle axial delivery.

The current device stably performs all basic functions. This study focuses on introducing the suspended endoscope as a delivery system auxiliary and demonstrating FDD design feasibility. Interchangeable fitting ferrules in the MDD accommodate diverse endoscopy wheel profiles (see Figure S1). Refined MDD design and optimization will be explored in future work.

2.4. Flexible Arm Delivery Device (FDD)

The FDD is divided into two functional assemblies—Friction Wheel Assembly (FA) and Gripper Assembly (GA)—based on its control of two DOFs: axial delivery and circumferential rotation. It also includes a Force Sensing Platform (FP) for collision detection, force sensing, and clinical platform compatibility.

2.4.1. Friction Wheel Assembly (FA)

The FA uses the friction wheel drive principle: two wheels radially compress the flexible arm to generate axial friction. Both wheels employ a cantilever beam-type single-side shaft fixing scheme, enabling rapid assembly/disassembly—critical for clinical efficiency and sterilization. Its key innovation is the adaptive clamping mechanism (Figure 1a).

Axial slippage during delivery (exacerbated by biological fluids) reduces operational accuracy. The FA detects slippage via real-time encoder value comparison. The driven wheel uses a lead screw to compress a spring, controlling clamping force linearly (this balances maximum static friction against the risk of clamping damage to the flexible arm). The wheels’ clamping contour distributes force evenly, reducing endoscope damage.

2.4.2. Gripper Assembly (GA)

A key challenge in endoscopic rotation is angle loss: under ideal conditions, the endoscope main body’s rotation transmits to the arm’s end at about 1:1 [30], but in actual surgical conditions, the necessary tortuosity of the flexible arm will compromise this (Figure 2).

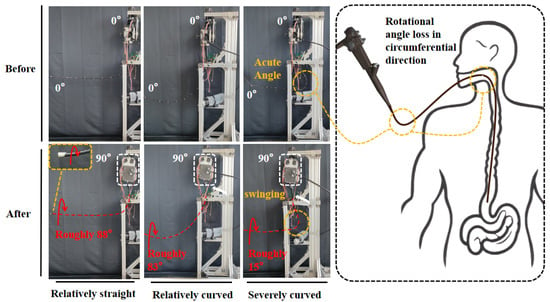

Figure 2.

Comparison of three bending postures of the endoscopic flexible arm.

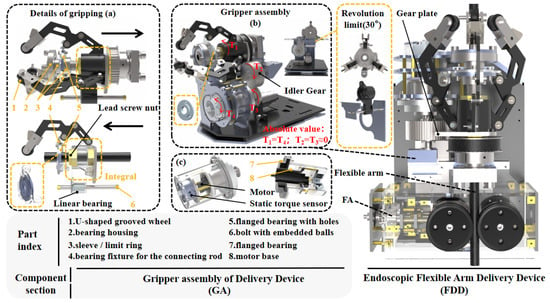

The GA is actuated by two motors. One motor controls the rotation of the hollow screw. The resulting linear motion of the nut drives three sets of coaxial parallel four-bar linkages (grippers), enabling radial clamping of the flexible arm. The contact ends of the grippers are U-grooved pulleys. The clamping action of these three grooved pulleys not only achieves circumferential positioning of the flexible arm but also preserves its degree of freedom for axial advancement. The other motor drives the rotation of the gripper assembly via a gear system. Since this motor is mounted solely on a torque sensor, with the flange bearing providing only support (as shown in Figure 3b,c), the actual operational torque can be directly measured in real time as torque by the sensor.

Figure 3.

GA structural diagram: (a) gripping details; (b) GA overall structure; (c) Rotation motor structure.

Rotational angle loss is an inherent issue that requires compensation. The GA operates under two primary scenarios: (1) when the flexible arm is extended only a short distance and undergoes sharp bending—a situation rarely encountered in practice but directly addressable by GA rotation (as shown in the third condition of Figure 2); and (2) when the flexible arm is inserted deeply with moderate bending—major rotation operations are managed via torque detection, whereas minor ones are handled directly by the GA.

Under scenario (2), when the MDD rotates, the middle segment of the flexible arm first undergoes an “idle rotation angle”—i.e., an ineffective rotational interval. Upon completion of this rotation, a sharp torque peak occurs at the GA clamping point, which triggers a system alert or control response, thereby improving the control efficiency of the rotational degree of freedom. If a positional deviation remains after the idle rotation, the GA can independently drive the distal end of the flexible arm to adjust by up to ±15°, a compensation action unaffected by the idle rotation occurring in the middle segment.

2.4.3. Force Sensing Platform (FP)

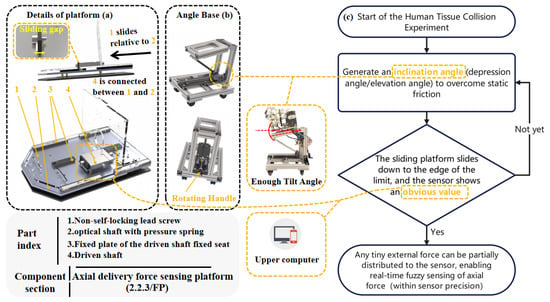

During axial delivery, two risks must be addressed: (1) accidental mucosal scraping/collision, and (2) overstretching the flexible arm. The FP mitigates these via real-time axial force detection.

To overcome static friction, the FP includes a slide rail and adjustable-angle fixed platform. As shown in Figure 4, a sliding clearance between the platforms allows the movable platforms (FA and GA) to slide and contact the fixed platform, thereby activating the tension–compression sensors. Within the stable tilt range—where the movable platform can consistently overcome static friction and initiate sliding—the sensors can reliably detect trends in axial external forces. Theoretically, even a minimal axial force applied to the flexible arm is distributed among three components: the sliding force of the movable platform, friction, and the tension/compression measured by the sensors. This distribution prevents the axial force from being completely masked by static friction when the system is near horizontal or at insufficient tilt angles, thereby avoiding undetectable scenarios. As a result, the sensor readings or their variation trends can alert the surgeon to potential collisions or overstretching.

Figure 4.

FP structural diagram and axial force experiment role: (a) FP details; (b) FP angle base structure; (c) Axial force detection experiment schematic.

The overall workflow of the complete ERS is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

ERS surgical workflow and DOF control logic diagram.

3. Results and Discussion

To meet the functional verification needs of each structural part of the FDD, the four motors of this device are all low-cost brushed DC gear motors. This selection helps reduce the device’s debugging cycle and manufacturing cost, allowing rapid judgment of the design’s rationality and feasibility only through encoder readings and the intuitive working effect of driving the flexible arm. However, this approach introduces known limitations, as the performance of these components may affect the quantitative rigor of certain verification experiments. A comprehensive performance evaluation with higher-precision hardware is planned for subsequent studies.

The endoscope used in this experiment is a dual-channel electronic endoscope for the digestive tract (GS-600DQ). The parameters of the key electrical components in the FDD are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

The parameter table of key electrical hardware.

Details of the experiment implementation and on-site layout can be viewed in the Supplementary Video attached to this article.

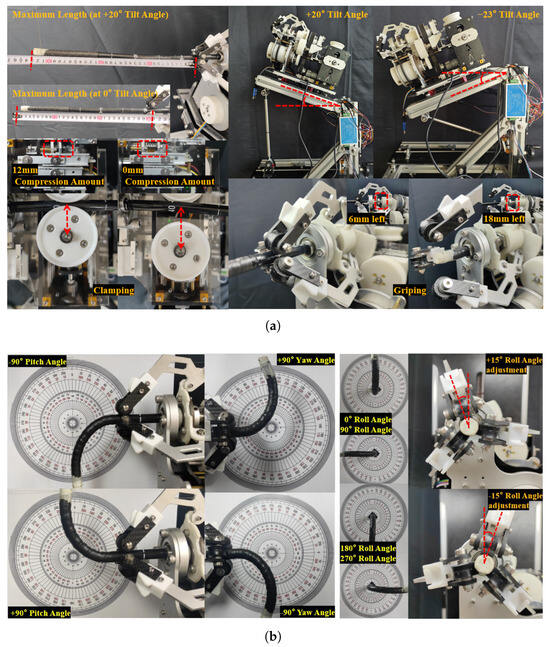

3.1. System Motion Capability Experiment

The overall motion capability reflects the robot system’s ability to control the motion of the endoscope’s flexible arm. Since the FDD can only control the flexible arm’s delivery and small-range circumferential rotation in terms of DOF, we integrate the MDD into this part of the experiment to ensure system integrity; by installing the endoscope, we test the stable motion range of each DOF using the drive motor.

For measuring instruments: the axial stroke of the flexible arm is measured with a tape measure (JC-06, DELIXI ELECTRIC, Linyi, Shandong, China); the compression amount of the pressure spring and the nut stroke of the GA are measured with a vernier caliper (YBKC-01, DELIXI ELECTRIC, China); the tilt angle of the FP and the roll angle of the GA are read directly from the designed 3D model; the pitch/yaw angles of the flexible arm are read by comparing with a common 360° protractor pattern; and the force magnitude is read in real time using the host computer provided by the sensor manufacturer (HYchuangan, China). The resulting motion parameter diagram, which provides an overview of the ERS 4-DOF control range, is shown in Figure 6. The detailed profiles of individual parameters (e.g., axial stroke–tilt angle relationship and rotational compensation range) are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

The overview of the endoscope driving parameters for the ERS.

Through experiments, it is confirmed that the system can stably achieve four DOFs of the flexible arm: pitching, yawing, telescoping, and rotation. The FP allows the FDD to have a sufficiently large elevation angle, enabling the tension–compression sensor to sense the initial contact force (the range obtained through continuous testing is 15 N–19 N; therefore, the sensing range is approximately 30 N).

A primary limitation identified in this experiment is the effective axial stroke. Although the FDD module has the ability to independently deliver the flexible arm with an axial stroke of 700 mm, after being integrated into the ERS system, the effective axial stroke (with GS-600DQ) is only about 280 mm (at a 23° depression angle) to 330 mm (at a 20° elevation angle). This is the result of using an endoscope with an effective length of only 1000 mm. To meet the operational requirements of ESD, the available length achieved by the robotic system should reach 900 mm. Replacing it with a longer endoscope, such as the ESM-370 (Weishikang Medical Electronics Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) (1680 mm effective length), could potentially achieve an available length of 960 mm to 1010 mm in this system. Alternatively, we can further optimize the structural design, module usage mode, and layout of the robotic system.

3.2. Operational Performance Experiment

3.2.1. Basic Surgical Operation Experiment

The operation mode of ERS directly affects its usability and operational experience. Based on the ADC peripheral of the STM32 control system (F407ZGT6, from Your Cee, Shenzhen, China), a simple wired remote controller is developed. The two toggle directions of a single joystick are respectively set as the forward and reverse control directions for two motors (e.g., the forward and backward toggle directions of the left joystick are configured to control the forward and reverse rotation of Motor 1 with 0–30% PWM, enabling teleoperation of Motor 1). In turn, open-loop control of the four motors of the FDD is realized via two joysticks. The toggle directions of the joysticks are set to correspond to the associated motion directions of the flexible arm, which helps improve operational intuitiveness. For the MDD, Bluetooth control via the HC-05 module is adopted to enable convenient debugging, and it assists the FDD in completing the experiments.

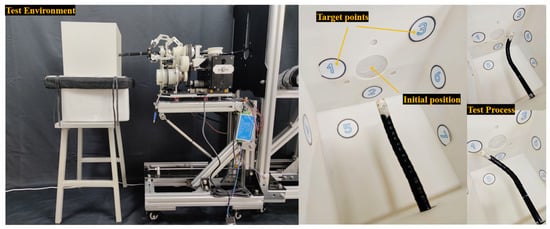

The setup of this surgical operation experiment is shown in Figure 8, and a working environment for the flexible arm is established: an open box with a delivery port is used, and 7 target points are placed at different positions inside the box to simulate the locations of target sites for various endoscopic procedures. The experimenter controls the joystick handle and Bluetooth software simultaneously by a single person to drive the system, guiding the end of the flexible arm to reach the simulated target positions. The video of the physical object’s motion effect can be found in Appendix A [Single-Person Operation of ERS].

Figure 8.

The experiment setup diagram for the surgical operation experiment.

During the experiment, it is observed that the control of the flexible arm’s delivery, pitching, and yawing is extremely sensitive. However, since the control of pitching and yawing has not yet been implemented through a mapping method similar to that of the joystick handle, controlling these two DOFs proved challenging, indicating a need for a more intuitive mapping strategy to improve usability.

Additionally, a key finding was the inferior clamping performance of the GA compared to that of the FA for rotational tasks: only when Motor 4 is stalled under 50% PWM can the generated friction force be sufficient to drive the entire endoscope (including the flexible arm) to rotate. Three main reasons are identified for this phenomenon: first, the GA lacks a flexible clamping structure, making it difficult to control the clamping force; second, the tangential friction force required for rotation is significantly greater than the axial friction force required for delivery; third, the U-shaped grooved wheels of the GA are made of smooth nylon without anti-slip patterns, resulting in a lower friction coefficient compared to the FA friction wheels (3D-printed with ABS).

Subsequently, to validate this hypothesis, the surface of the grooved wheels is manually modified to increase its coefficient of friction. Upon repeating the experiment, it is found that the anti-slip effect for rotation is indeed improved (with only approximately 45% PWM required to drive rotation). Overall, the GA can achieve a certain degree of rotation control: within a rotation angle range of 30°, it can independently control the end of the flexible arm to reach the simulated target areas.

3.2.2. Tilt Angle Force Experiment

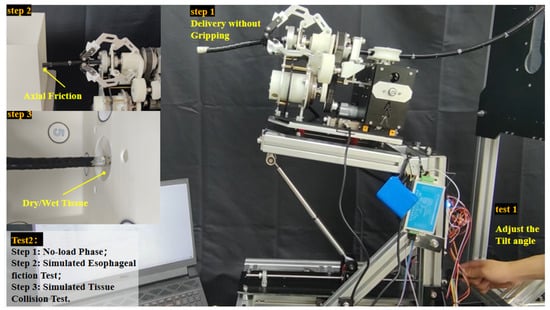

To characterize the force sensing capabilities of the FP, an experiment was conducted to investigate the influence of static and sliding friction. Specifically, this experiment only involves adjusting the tilt angle to observe the variation characteristics of the force. The setup of the tissue collision force experiment is depicted in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

The tissue collision force experiment setup diagram.

In this experiment, the force magnitude is read in real time using the host computer provided by the sensor manufacturer (HYchuangan, Bengbu, Anhui, China). Considering that the sensor has a detection accuracy of only 0.1 N and the lack of a calibration compensation algorithm, no zero-calibration is performed on the tension/compression force data. This approach facilitates the judgment of the actual force-bearing condition and also makes it easy to determine whether the absolute measuring range (50 N) is exceeded.

In the experiment, when the movable platform of the FDD stably shows a downward sliding trend, the absolute value of the initial tension/compression force detected by the tension–compression sensor is approximately 17.3 N (in practice, this value still fluctuates by about ±1.3 N due to sliding friction), corresponding to an inclination angle of roughly 8°. Therefore, when the downward or upward tilt angle exceeds 8°, the movable platform maintains a stable downward sliding trend, enabling the most accurate detection of external forces—this serves as the minimum tilt threshold for all subsequent force measurement experiments.

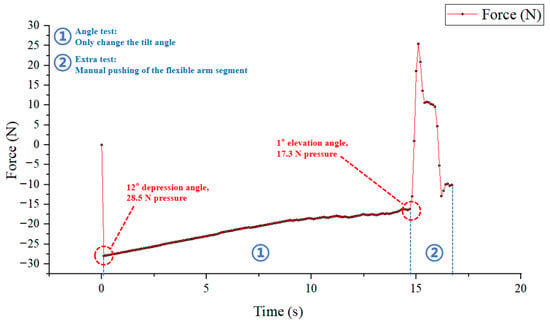

To preliminarily verify the real-time performance and accuracy of the sensor after installation on the device, a downward tilt scenario is tested: starting from an initial downward tilt angle of approximately 13°, an initial force of 28.5 N is recorded. With the sensor kept powered on, as the downward tilt angle is further increased, the force is observed to increase controllably at the sensor’s precision (0.1 N) as shown in Figure 10. However, when the force returns to around 17.3 N, the tilt angle of the FP is close to horizontal (approximately 1° upward tilt). When the tilt angle is 0° (horizontal state), the sensor force is approximately 17.5 N, which indicates that the horizontal static friction force is at least greater than 17.5 N.This significant static friction may be attributed to the use of standard drawer slides in the FP assembly.

Figure 10.

The tilt angle experiment setup diagram.

This experiment already demonstrates that the influence of friction is significant enough to greatly reduce the accuracy of tissue collision force experiments. Nevertheless, since the sensor can still provide real-time feedback with a minimum precision of 0.1 N on the device, the subsequent experiment aimed to determine if the trend of force variation, rather than its absolute value, could reliably indicate different operational states. This approach, if viable, would hold reference value even with low-cost components.

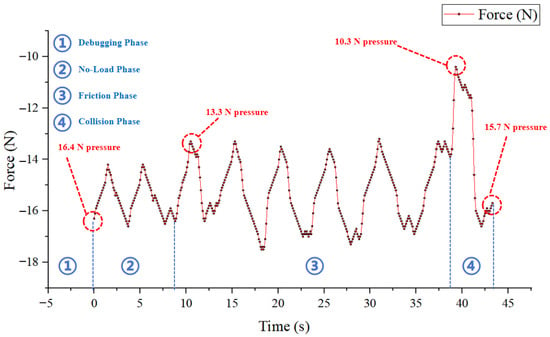

We quickly conducted experiments under various working conditions, and basically obtained relatively obvious and distinguishable force curves. Taking Figure 11 as an example, the experiment was carried out at an 8° depression angle. Phase 2 (Step 1) to Phase 4 (Step 3) correspond respectively to the no-load delivery stage of the GA (without clamping), the simulated friction stage under normal friction of the human esophagus (using holes for simulation), and the collision stage where the end of the flexible arm breaks through the wet tissue while maintaining the friction state.

Figure 11.

Force curve diagram of the experiment under three working condition stages.

Although the sensed force value of this curve has a repeatability deviation of approximately ±1 N under different working conditions, the characteristics under each working condition can still be clearly distinguished through the force change rate. However, the reliability of this method is compromised by several factors. First, the experimental conditions were not exhaustive. Second, obvious vibrations generated during the operation of the FDD, or vibrations generated during the GA clamping process controlled by Motor 3, will make the characteristics of the force curve extremely irregular. These findings suggest that while trend-based force sensing is a promising concept, its current implementation is not sufficiently robust for reliable application due to mechanical noise, and the video of the intuitive response effect of the tension–compression force sensor can be found in Appendix A [Elevation Angle and Human Tissue Collision Test].

3.2.3. Discussion

First, in terms of four DOFs control performance (pitching, yawing, axial telescoping, and circumferential rotation), the achieved stable manipulation ranges (e.g., 360° circumferential rotation and 180° bending) confirm the mechanical design’s adequacy for macro-scale positioning of the flexible arm during various gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures. As summarized in Table 3 (Section 2.2), the system achieves 280–330 mm axial delivery stroke and ±15° rotational compensation capability through the FDD. However, the operation mode still needs to be improved in terms of intuitiveness and simplicity.

Second, the roles of the GA design in both mitigating circumferential angle loss and reducing the flexible arm’s usable stroke require further discussion. Future designs must therefore focus on miniaturizing the GA or better balancing this functional trade-off. For instance, it is feasible to reduce the height of the MDD, thereby shortening the middle section of the flexible arm and increasing the axial telescopic stroke of the ERS. These design efforts are all aimed at better fulfilling the essential requirements of surgical procedures.

Third, the low-cost force-sensing method proved inadequate for reliable collision detection due to its qualitative nature and noise susceptibility. Should this function be retained, any future implementation must incorporate higher-precision sensors and effective vibration damping.

Finally, the manufacturing cost is remarkably low, which highlights the system’s potential for low-cost production. Using low-performance motors and sensors was a deliberate choice to prioritize rapid functional verification, but future work should balance necessary hardware upgrades—essential for translating laboratory prototypes into commercial products.

4. Conclusions

This study designed, fabricated, and validated an Endoscopic Robotic System (ERS) for robot-assisted gastrointestinal endoscopic surgery (RAGES). Through systematic structural design and experimental validation, the ERS achieved stable control over four degrees of freedom of the endoscopic flexible arm, including 360° circumferential rotation, 180° bending, 280–330 mm axial delivery, and ±15° rotational compensation—capabilities that address the macro-positioning requirements of various gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures including ESD, polypectomy, and therapeutic interventions.

The main innovations include the following: a high-precision delivery control module (FDD) with flexible clamping and dual-encoder slip detection; a gripper assembly (GA) that mitigates circumferential angle loss—common in suspended endoscope configurations—through real-time torque sensing and ±15° fine-tuning; and compatibility with standard dual-channel endoscopes (e.g., GS-600DQ) without the need for custom modifications. The low-cost manufacturing approach demonstrates feasibility for rapid prototyping and accessible production.

Key limitations pave the way for future research. First, miniaturization of the GA is necessary to maximize the endoscope’s usable stroke—currently reduced from 700 mm (standalone FDD) to 280–330 mm (integrated system). Integration of longer endoscopes or redesign of the GA could address this constraint. Second, the force-sensing approach requires validation with higher-precision sensors and vibration damping mechanisms before clinical translation. The current implementation’s susceptibility to mechanical vibrations and reliance on qualitative trend analysis necessitate substantial refinement. Finally, the hybrid control interface (joystick and Bluetooth) should be unified to streamline the surgical workflow and reduce cognitive load on operators.

This research offers a design reference for endoscopic robotic systems targeting RAGES applications and serves as a foundational step toward clinically viable, accessible robotic platforms for advanced endoscopic procedures. By demonstrating that a compact, low-cost system can achieve comprehensive four-DOF control while addressing key challenges such as angle loss and slippage detection, this work establishes proof-of-concept for democratizing robotic assistance in gastrointestinal endoscopy.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/act15010014/s1, Figure S1: Schematic Diagram of the Structure and Working Principle of MDD; Table S1: Detailed Specifications in Table 1; Video S1: Single-Person Operation of ERS; Video S2: Elevation Angle and Human Tissue Collision Test.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C. and C.H.; methodology, P.C.; software, H.X.; validation, P.C., C.H. and Y.L.; formal analysis, P.C.; investigation, P.C., J.C. and C.G.; resources, C.H. and G.G.; data curation, P.C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.C.; writing—review and editing, C.H., P.C. and Y.L.; visualization, P.C.; supervision, C.H.; project administration, C.H. and G.G.; funding acquisition, C.H. and G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62563021), Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects 202401BE070001-047 and 202501CF070162.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the assistance of DeepSeek-V3.2 in language polishing during the manuscript preparation. All content was ultimately reviewed, revised, and confirmed by the authors to ensure accuracy and compliance with academic standards.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

The motion capabilities of the ERS mentioned in the experiment, the single-person operability of the ERS, and the fuzzy sensing effect of the sensor on real-time collision force can be intuitively observed through the two videos in Supplementary Materials.

Table A1.

Attachment video information.

Table A1.

Attachment video information.

| Video Title | Displayed Content | Video Length(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Person Operation of ERS | Basic Motion and Manipulation | 169 |

| Elevation Angle and Human Tissue Collision Test | Intuitive Manifestation of Fuzzy Sensing | 115 |

Appendix B

The Supplementary Materials also include two images: a schematic diagram of the MDD’s structure and installation method (Figure S1), and a detailed supplement to Table S1, with the latter being provided in the form of an Excel spreadsheet.

Table A2.

Attachment figure and table information.

References

- Gotoda, T.; Kondo, H.; Ono, H.; Saito, Y.; Yamaguchi, H.; Saito, D.; Yokota, T. A new endoscopic mucosal resection procedure using an insulation-tipped electrosurgical knife for rectal flat lesions: Report of two cases. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1999, 50, 560–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yahagi, N.; Fujishiro, M.; Kakushima, N.; Kobayashi, K.; Hashimoto, T.; Oka, M.; Iguchi, M.; Enomoto, S.; Ichinose, M.; Niwa, H.; et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer using the tip of an electrosurgical snare (thin type). Dig. Endosc. 2004, 16, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanström, L.L. Treatment of early colorectal cancers: Too many choices? Endoscopy 2012, 44, 991–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deprez, P.H.; Bergman, J.J.; Meisner, S.; Ponchon, T.; Repici, A.; Dinis-Ribeiro, M.; Haringsma, J. Current practice with endoscopic submucosal dissection in Europe: Position statement from a panel of experts. Endoscopy 2010, 42, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukami, N. What we want for ESD is a second hand! Traction method. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2013, 78, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Cheon, B.; Kim, J.; Kwon, D.S. easyEndo robotic endoscopy system: Development and usability test in a randomized controlled trial with novices and physicians. Int. J. Med. Robot. 2021, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiter, J.; Rozeboom, E.; van der Voort, M.; Bonnema, M.; Broeders, I. Design and evaluation of robotic steering of a flexible endoscope. In Proceedings of the 2012 4th IEEE RAS & EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob), Rome, Italy, 24–27 June 2012; pp. 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanpei, H.; Wenjie, L.; Lin, C.; Burdet, E.; Phee, S.J. Design and Evaluation of a Foot-Controlled Robotic System for Endoscopic Surgery. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 2469–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivananthan, A.; Kogkas, A.; Glover, B.; Darzi, A.; Mylonas, G.; Patel, N. A novel gaze-controlled flexible robotized endoscope; preliminary trial and report. Surg. Endosc. 2021, 35, 4890–4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohuchida, K. Robotic surgery in gastrointestinal surgery. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2020, 2020, 9724807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorn, L.; Nageotte, F.; Zanne, P.; Legner, A.; Dallemagne, B.; Marescaux, J.; de Mathelin, M. A Novel Telemanipulated Robotic Assistant for Surgical Endoscopy: Preclinical Application to ESD. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 65, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, S.; Khorasani, M.; Abdurahiman, N.; Padhan, J.; Baez, V.; Al-Ansari, A.; Tsiamyrtzis, P.; Becker, A.T.; Navkar, N.V. A generic scope actuation system for flexible endoscopes. Surg. Endosc. 2024, 38, 1096–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakadate, R.; Iwasa, T.; Onogi, S.; Arata, J.; Oguri, S.; Okamoto, Y.; Akahoshi, T.; Eto, M.; Hashizume, M. Surgical robot for intraluminal access: An ex vivo feasibility study. AAAS Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2020, 2020, 8378025. [Google Scholar]

- Pullens, H.J.; van der Stap, N.; Rozeboom, E.D.; Schwartz, M.P.; van der Heijden, F.; van Oijen, M.G.; Siersema, P.D.; Broeders, I.A. Colonoscopy with robotic steering and automated lumen centralization: A feasibility study in a colon model. Endoscopy 2016, 48, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozeboom, E.; Ruiter, J.; Franken, M.; Broeders, I. Intuitive user interfaces increase efficiency in endoscope tip control. Surg. Endosc. 2014, 28, 2600–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilink, R.; de Bruin, G.; Franken, M.; Mariani, M.A.; Misra, S.; Stramigioli, S. Endoscopic camera control by head movements for thoracic surgery. In Proceedings of the 2010 3rd IEEE RAS & EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics, Tokyo, Japan, 26–29 September 2010; pp. 510–515. [Google Scholar]

- Khorasani, M.; Abdurahiman, N.; Padhan, J.; Zhao, H.; Al-Ansari, A.; Becker, A.T.; Navkar, N. Preliminary design and evaluation of a generic surgical scope adapter. Int. J. Med. Robot. Comput. Assist. Surg. 2023, 19, e2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurahiman, N.; Khorasani, M.; Padhan, J.; Baez, V.M.; Al Ansari, A.; Tsiamyrtzis, P.; Becker, A.T.; Navkar, N.V. Scope actuation system for articulated laparoscopes. Surg. Endosc. 2023, 37, 2404–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurahiman, N.; Padhan, J.; Zhao, H.; Balakrishnan, S.; Al-Ansari, A.; Abinahed, J.; Velasquez, C.A.; Becker, A.T.; Navkar, N.V. Human-computer interfacing for control of angulated scopes in robotic scope assistant systems. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Symposium on Medical Robotics (ISMR), Atlanta, GA, USA, 13–15 April 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiter, J.; Bonnema, G.M.; van der Voort, M.C.; Broeders, I.A.M.J. Robotic control of a traditional flexible endoscope for therapy. J. Robot. Surg. 2013, 7, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasa, T.; Nakadate, R.; Onogi, S.; Okamoto, Y.; Arata, J.; Oguri, S.; Ogino, H.; Ihara, E.; Ohuchida, K.; Akahoshi, T. A new robotic-assisted flexible endoscope with single-hand control: Endoscopic submucosal dissection in the ex vivo porcine stomach. Surg. Endosc. 2018, 32, 3386–3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kume, K.; Sakai, N.; Goto, T. Development of a novel endoscopic manipulation system: The endoscopic operation robot ver. 3. Endoscopy 2015, 47, 815–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. Research on the Design and Sensing Method of a Dexterous Mechanism for Digestive Endoscopic Robots. Master’s Thesis, Shenyang Ligong University, Shenyang, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Funk, E.; Goldenberg, D.; Goyal, N. Demonstration of transoral robotic supraglottic laryngectomy and total laryngectomy in cadaveric specimens using the Medrobotics Flex System. Head Neck 2017, 39, 1218–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, S.; Hodges, A.; Larach, S.W. Direct target NOTES: Prospective applications for next generation robotic platforms. Tech. Coloproctol. 2018, 22, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remacle, M.; Prasad, V.M.N.; Lawson, G.; Plisson, L.; Bachy, V.; Van der Vorst, S. Transoral robotic surgery (TORS) with the Medrobotics Flex™ System: First surgical application on humans. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2015, 272, 1451–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Serrano, C.M.; Johnson, P.; Zubiate, B.; Kuenzler, R.; Choset, H.; Zenati, M.; Tully, S.; Duvvuri, U. A transoral highly flexible robot. Laryngoscope 2012, 122, 1067–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phee, S.J.; Reddy, N.; Chiu, P.W.; Rebala, P.; Rao, G.V.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Wong, J.Y.; Ho, K.Y. Robot-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection is effective in treating patients with early-stage gastric neoplasia. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 1117–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, D.J.; Becke, C.; Rothstein, R.I.; Peine, W.J. Design of an endoluminal NOTES robotic system. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, 29 October–2 November 2007; pp. 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Phee, S. Modeling tendon-sheath mechanism with flexible configurations for robot control. Robotica 2013, 31, 1131–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.