Path Planning and Tracking Control for Unmanned Surface Vehicle Based on Adaptive Differential Evolution Algorithm

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- In comparison with the existing research on collision avoidance strategies [17,18,19], this paper introduces an elite archiving mechanism and adaptive adjustments of the scaling factor F and crossover factor , which effectively improve population diversity and prevent premature convergence. Moreover, by integrating COLREGs into the algorithm design, the method enhances autonomous obstacle avoidance in complex maritime scenarios. A multi-objective fitness function is used, which incorporates factors such as voyage distance, collision risk, and vessel maneuverability. This significantly improves the rationality, safety, and feasibility of the planned paths.

- (2)

- The primary contribution of this paper lies in the control aspect. In comparison with traditional path tracking methods [20,21,22], a systematic framework is developed to model USV motion based on the path coordinates generated by CRI-DE. A fuzzy logic system is employed for adaptive control, ensuring an effective match between the USV’s motion trajectory and the planned command signals. This approach overcomes the limitation of conventional algorithms that often neglect dynamic environmental disturbances, thus achieving high-precision integrated path planning and tracking control for USVs.

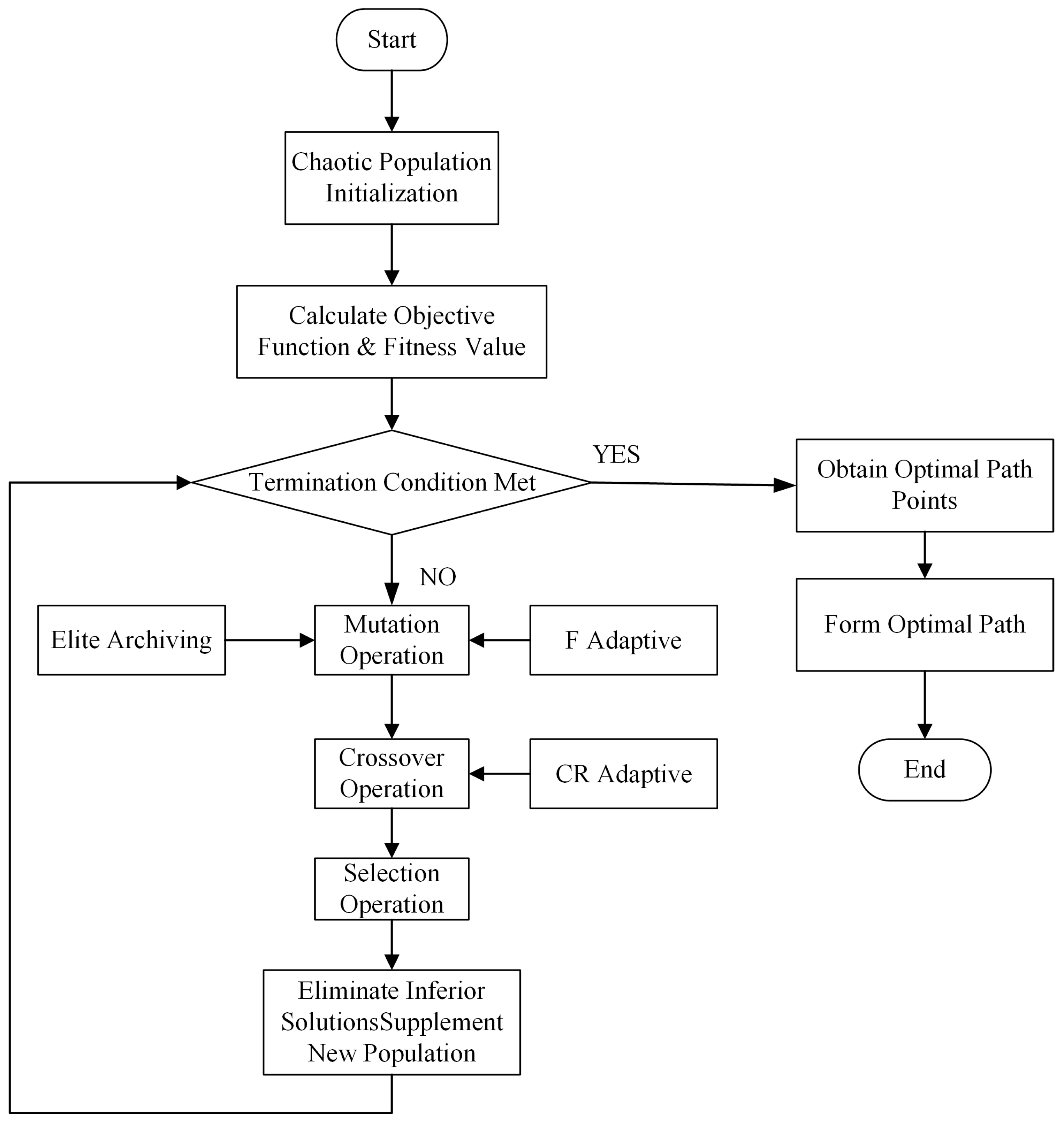

2. Path Planning for USVs Based on Adaptive Differential Evolution

2.1. Differential Evolution Algorithm

2.1.1. Population Initialization

2.1.2. Fitness Evaluation

2.1.3. Differential Mutation

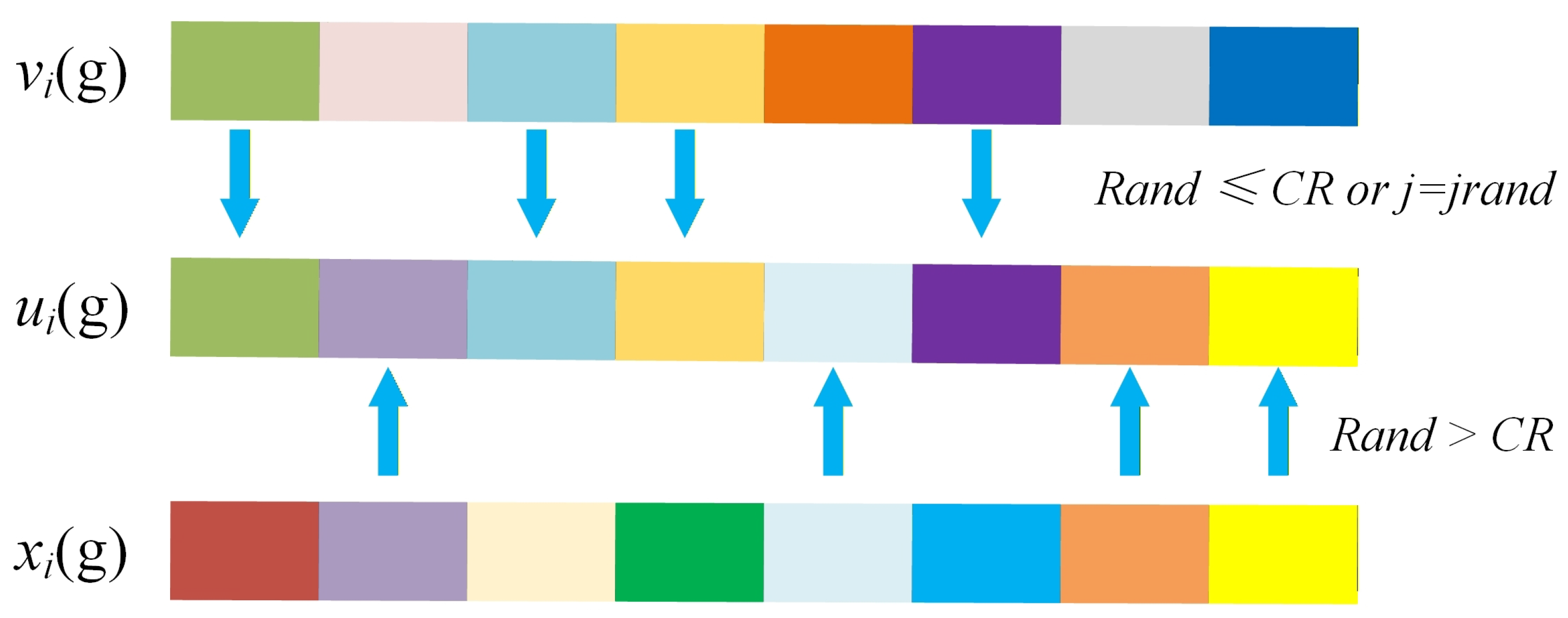

2.1.4. Crossover Operation

2.1.5. Selection Operations

2.2. Improvement Strategies for Differential Evolution Algorithms

2.2.1. Elite Archive Strategy

- (1)

- If was originally a member of G, it directly replaces its counterpart in G.

- (2)

- If is not a member of G but exhibits superior fitness compared with the worst individual in G, it replaces that worst individual. The replaced individual is subsequently transferred to B, and the original counterpart of is removed from B.

2.2.2. Adaptive Factors

2.2.3. Collision Risk Index Model

2.2.4. Fitness Function

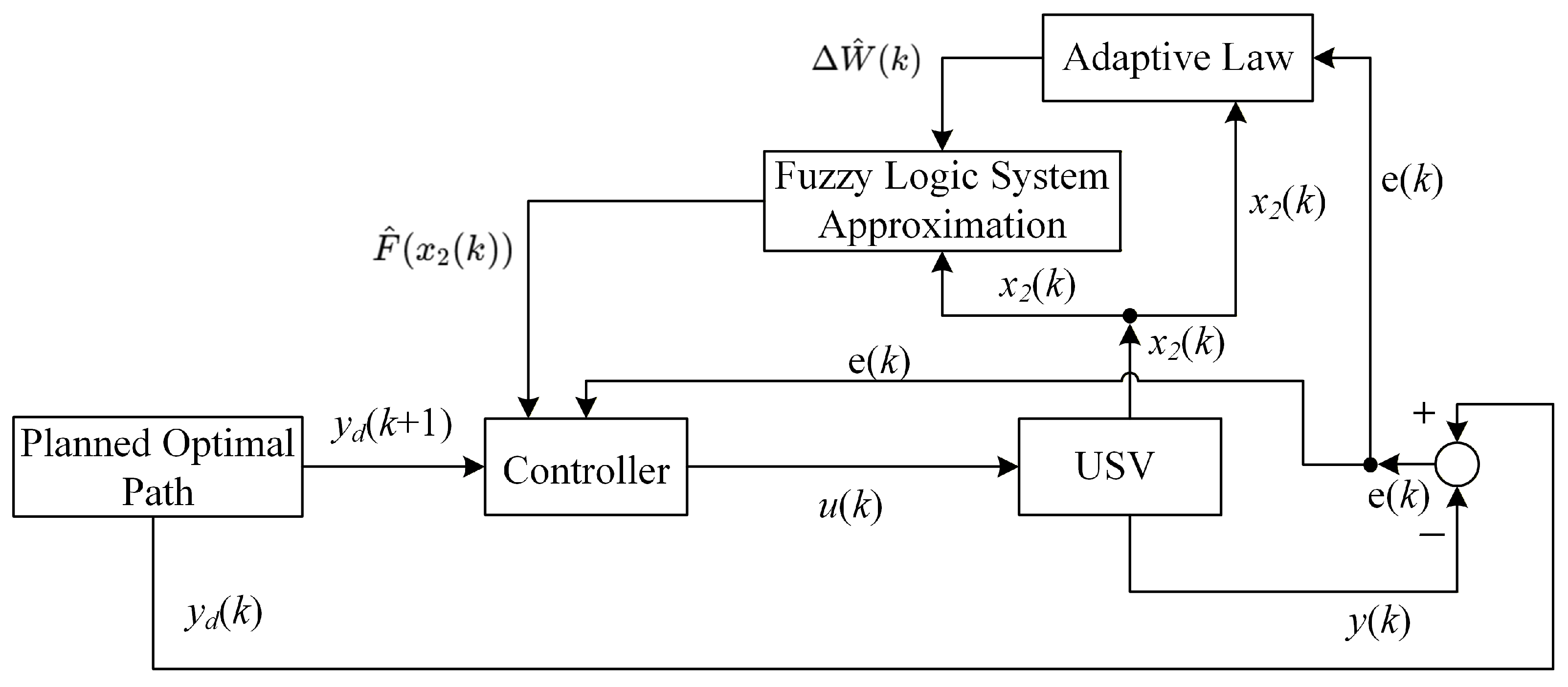

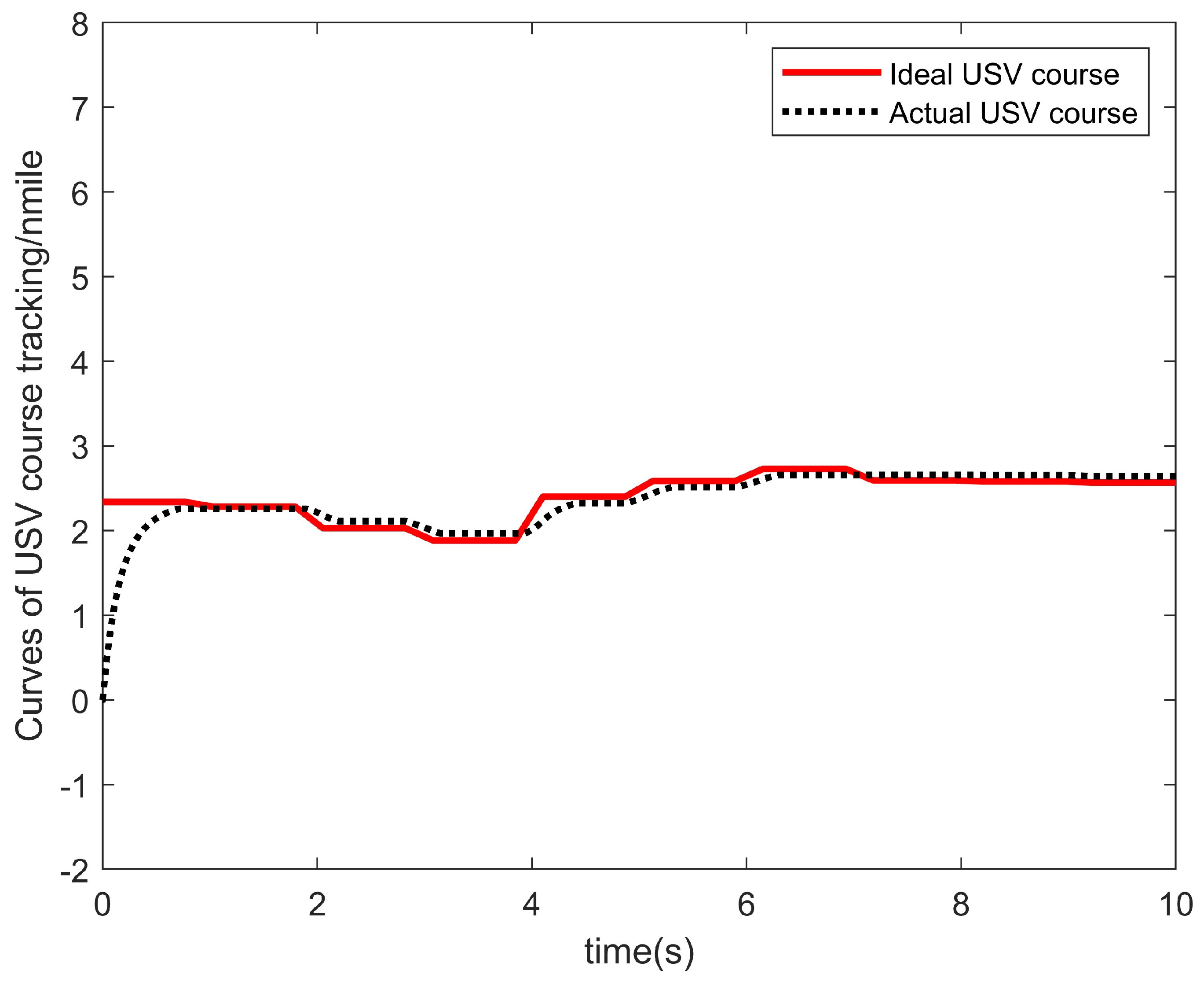

3. Path Tracking Control for USVs

3.1. Mathematical Model of Ship Heading Motion

3.2. Design of Adaptive Fuzzy Logic System Controller for Vessels

3.3. Stability Analysis

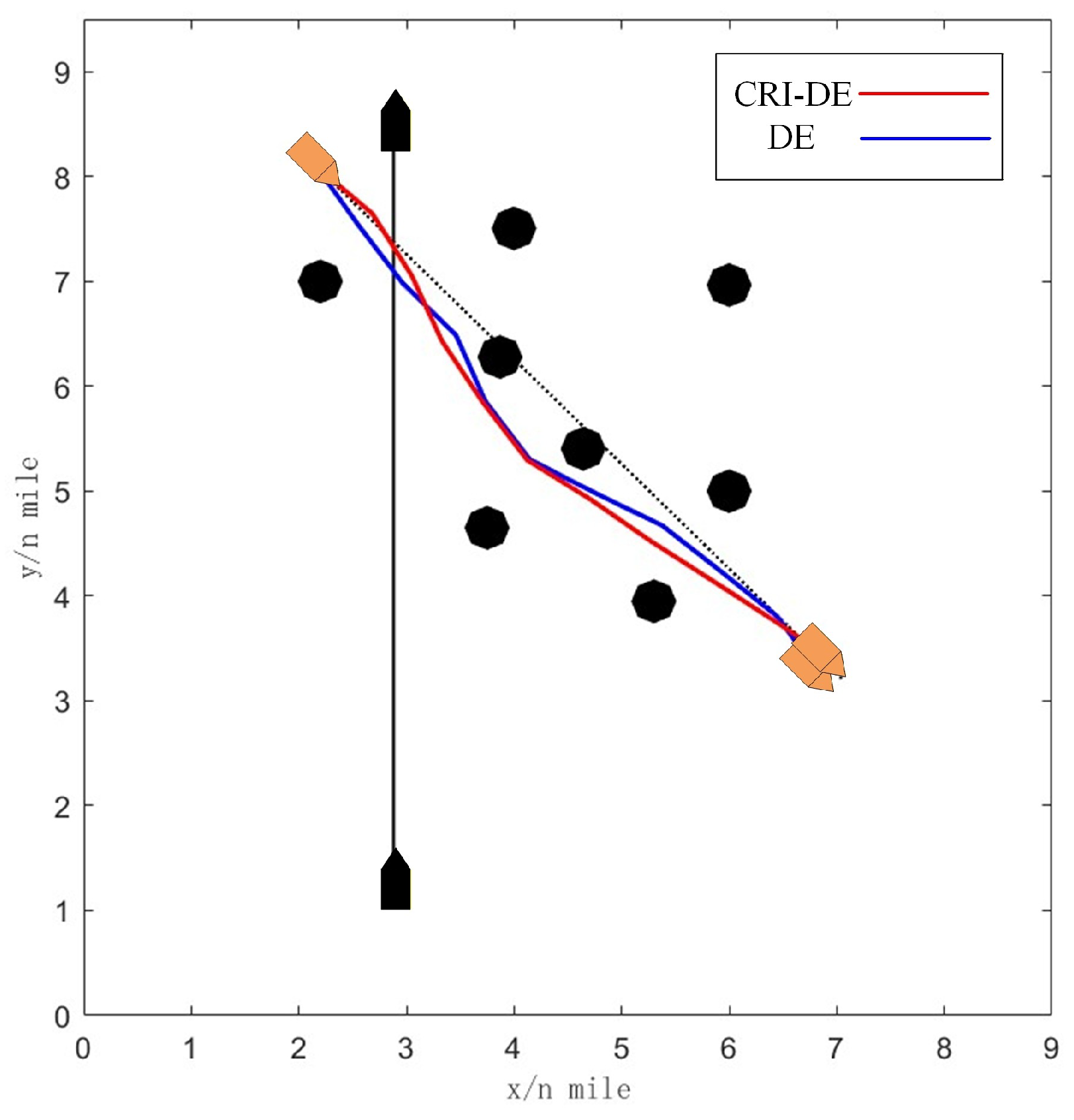

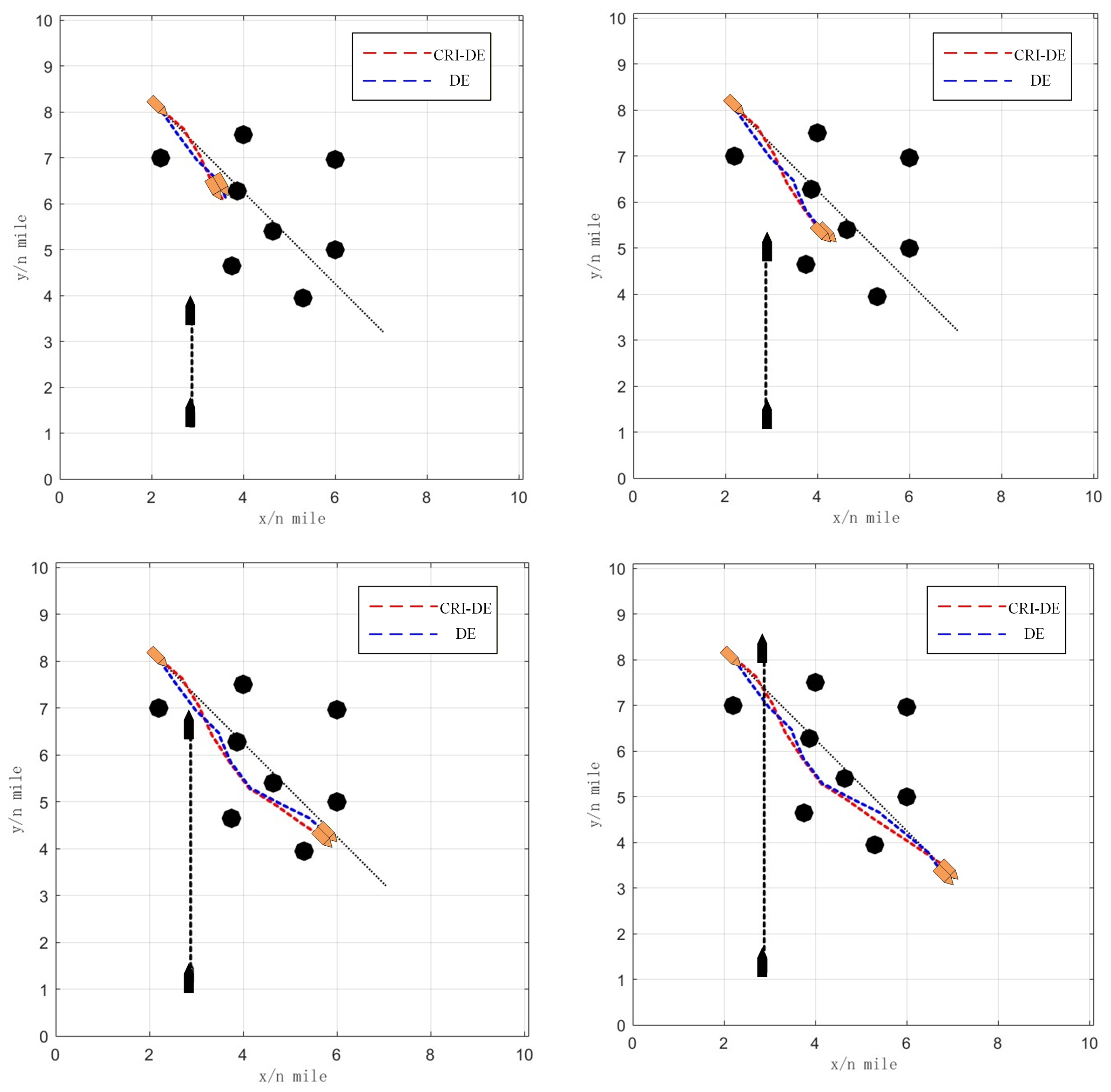

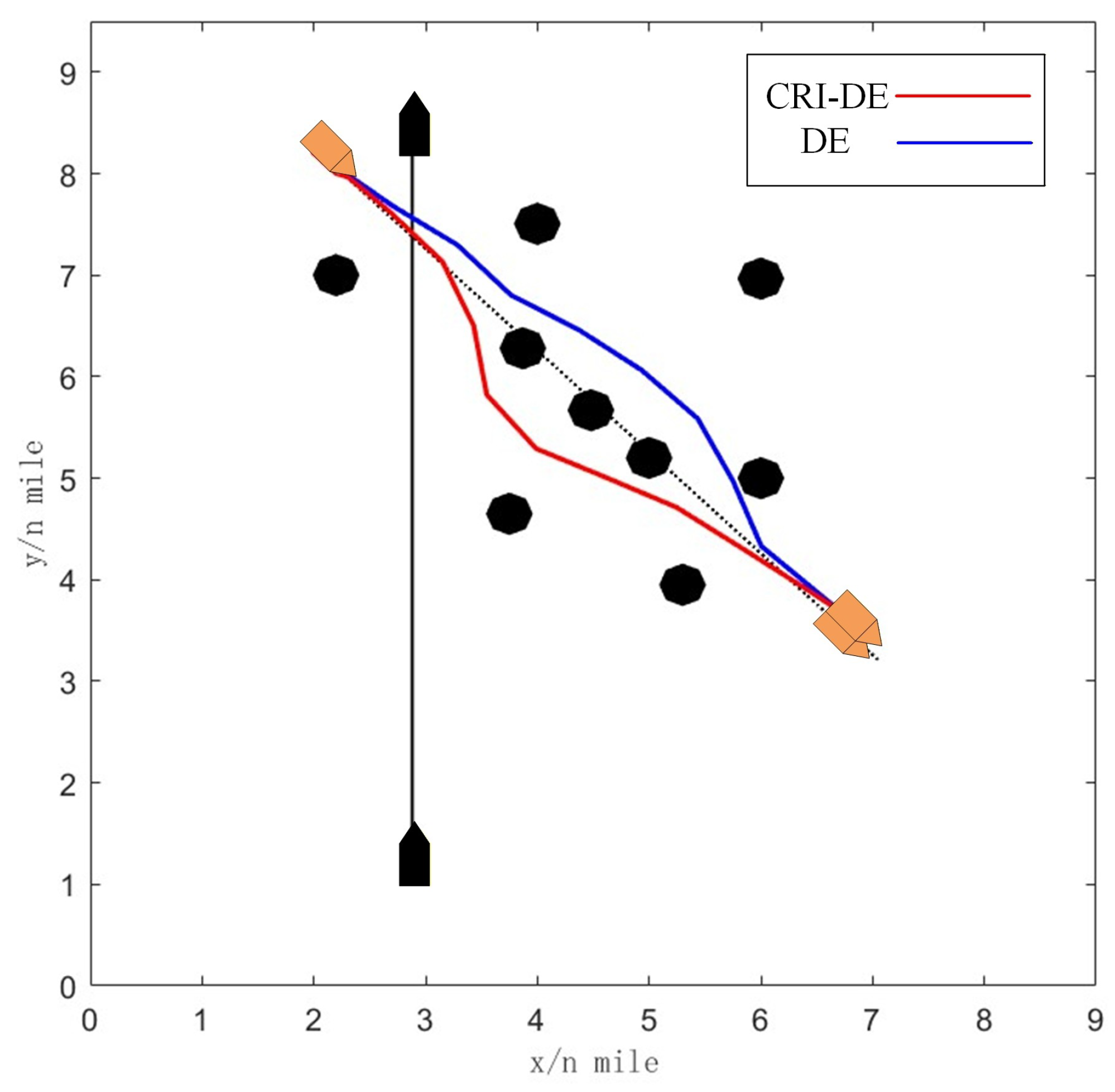

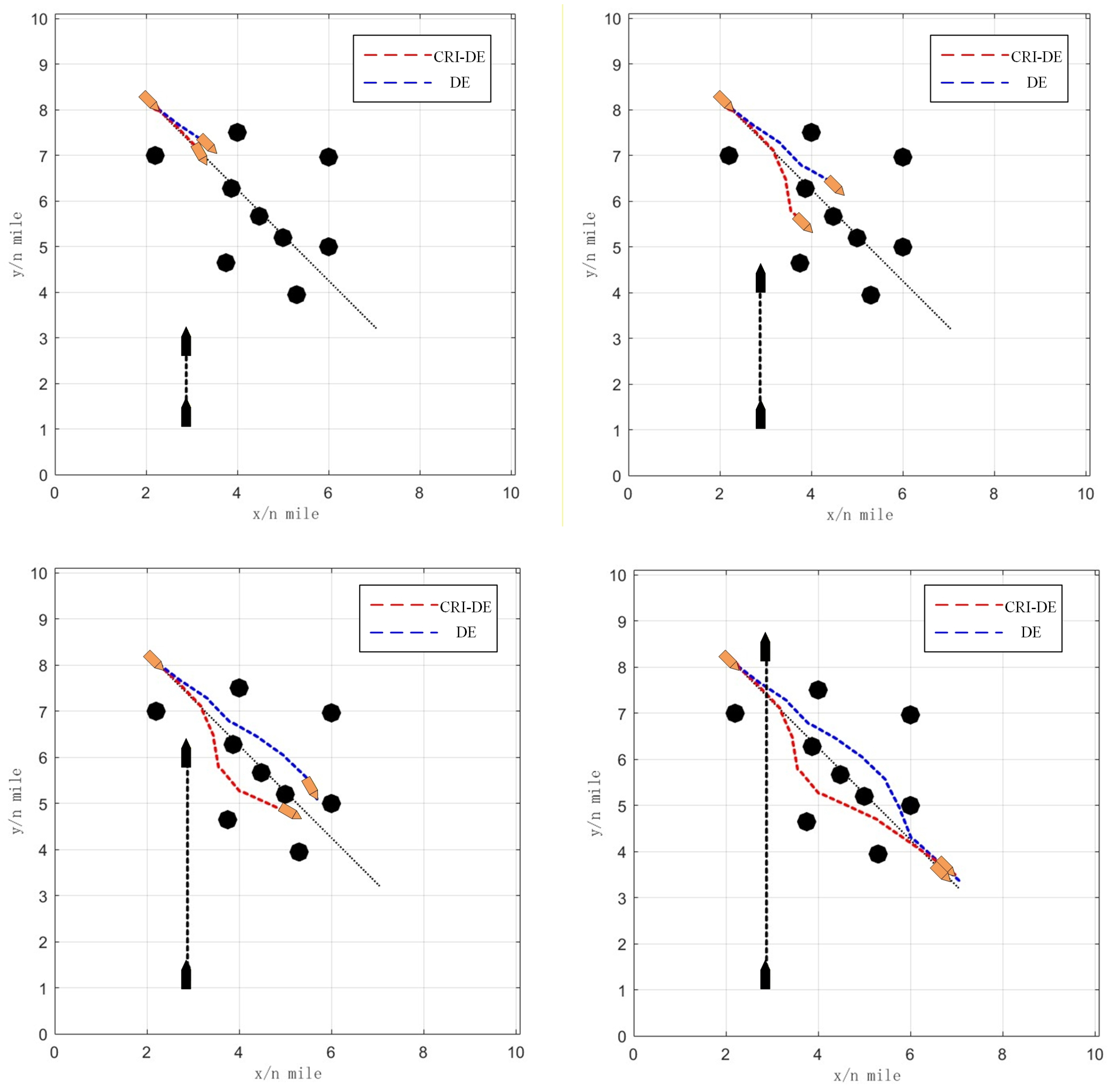

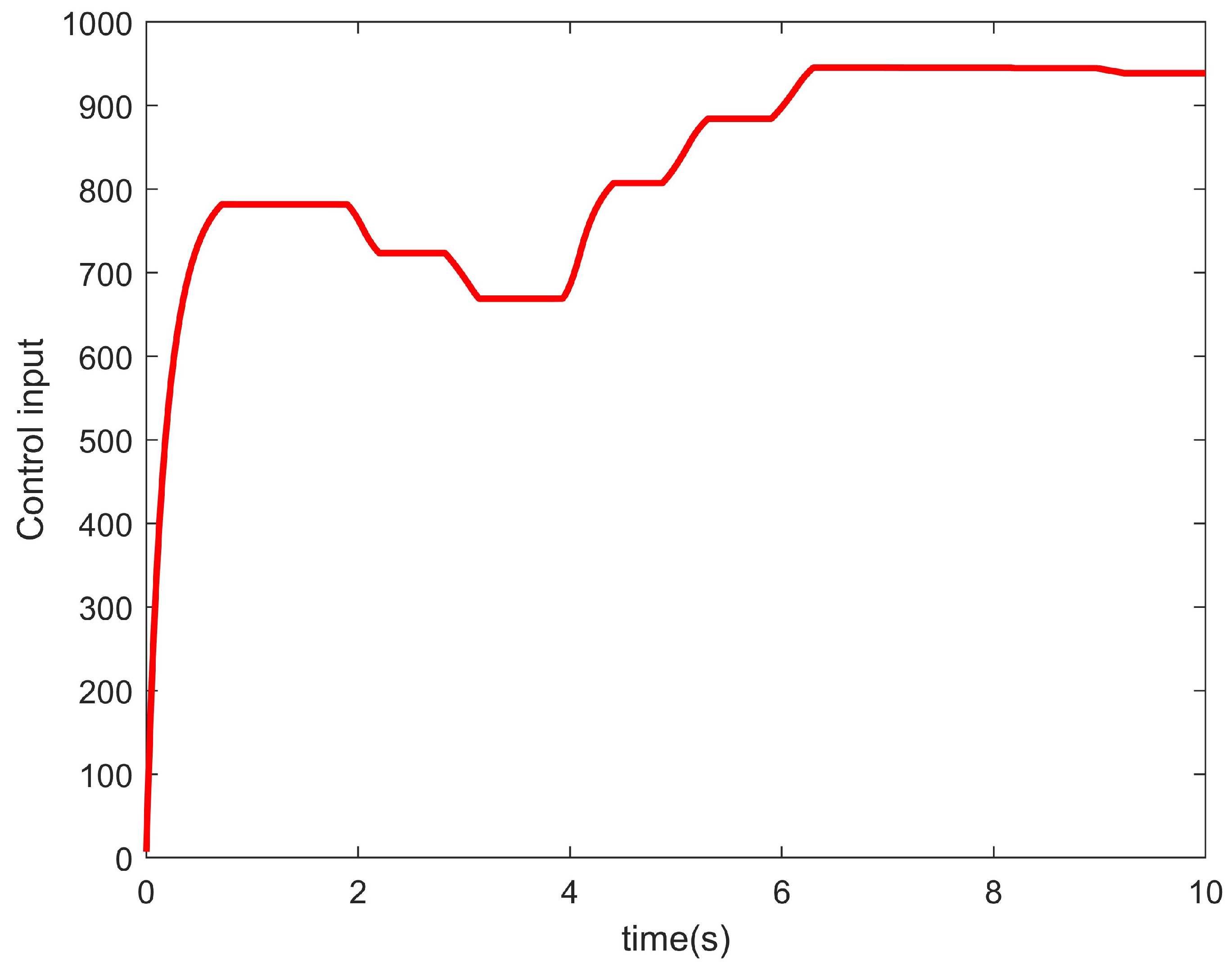

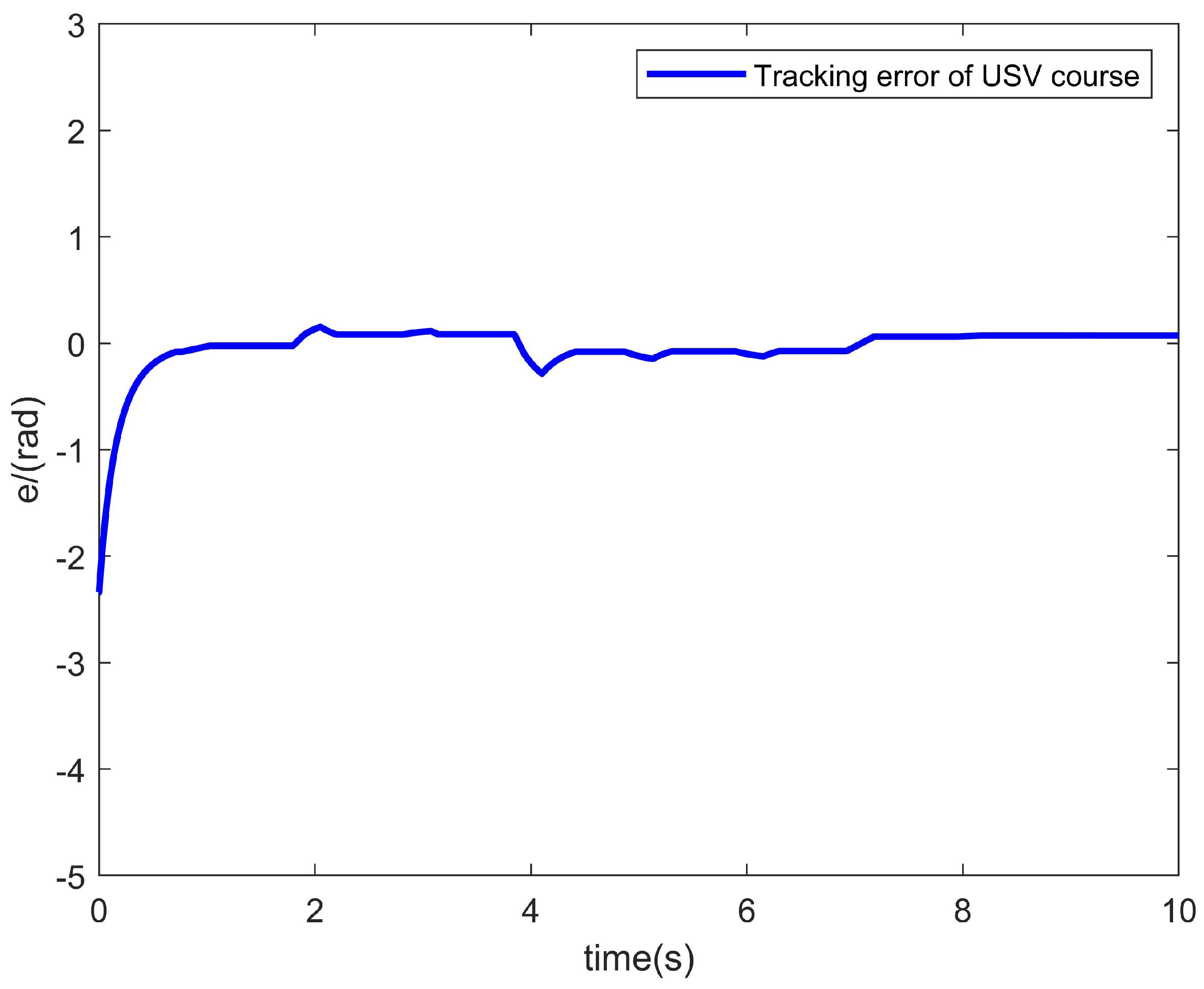

4. Simulation Result

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, T.; Xue, Y.; Xue, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Miao, Z.; Liu, Y. USV-Tracker: A novel USV tracking system for surface investigation with limited resources. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 312, 119196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H. Ship Path Planning Based on Improved Ant Colony Algorithm. Master’s Thesis, Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China, 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Ma, L. An Improved NSGA-II Algorithm for Multi-Objective Nonlinear Optimization. Microelectron. Comput. 2020, 37, 47–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Path Planning for Firefighting Robots Based on an Improved Bidirectional A*-Potential Field Hybrid Algorithm. Robotics 2023, 12, 123. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lyridis, D.V. An improved ant colony optimization algorithm for unmanned surface vehicle local path planning with multi-modality constraints. Ocean. Eng. 2021, 241, 109890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential evolution–A simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. J. Glob. Optim. 1997, 11, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, R.; Fukunaga, A. Success-history based parameter adaptation for differential evolution. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Cancun, Mexico, 20–23 June 2013; pp. 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Z. An improved differential evolution with adaptive population allocation and mutation selection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 258, 125130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Jiang, N.; Wang, X.; Li, M. A hybrid algorithm based on grey wolf optimizer and differential evolution for UAV path planning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 215, 119327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Chen, W.N.; Hu, X.M.; Gu, T.; Yuan, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J. Path planning in multiple-AUV systems for difficult target traveling missions: A hybrid metaheuristic approach. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2019, 12, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, M.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, R.; Dong, S. Multi-AUV adaptive path planning and cooperative sampling for ocean scalar field estimation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.; Liang, X.; Tao, H.; Gong, J.; Qu, X. Global Path Planning and Finite-Time Tracking Control for Unmanned Underwater Vehicles. J. Shanghai Marit. Univ. 2022, 43, 1–7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wei, N.; Kuang, X. Path Planning and Tracking Control of Surface Unmanned Boats in Restricted Areas. J. Ship Mech. 2021, 25, 1127–1136. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. Research on Path Planning and Control Algorithms for Unmanned Vessels Based on Specific Observation Targets. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Engineering University, Harbin, China, 2019. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Precup, R.E.; Voisan, E.I.; Petriu, E.M.; Tomescu, M.L.; David, R.C.; Szedlak-Stinean, A.I.; Roman, R.C. Grey wolf optimizer-based approaches to path planning and fuzzy logic-based tracking control for mobile robots. Int. J. Comput. Commun. Control 2020, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Path Planning and Following Algorithms for Underactuated Ships. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai, China, 2017. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Mou, J.; Chen, P.; Li, M. Path planning for autonomous ships: A hybrid approach based on improved apf and modified vo methods. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S. Intelligent ship collision avoidance algorithm based on DDQN with prioritized experience replay under COLREGs. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; Wang, J.B.; Zeng, C.; Zhang, H.; Lin, M.; Li, G.Y. Unmanned-surface-vehicle-aided maritime data collection using deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 19773–19786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, Z.; Hu, H.; Wang, L.; Dong, J. Backstepping adaptive sliding mode control for the USV course tracking system. In Proceedings of the 2017 9th International Conference on Advanced Infocomm Technology (ICAIT), Chengdu, China, 22–24 November 2017; pp. 265–269. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.; Liao, Y.; Li, Y.; Fan, J.; Miao, Y. Heading control of unmanned surface vehicle with variable output constraint model-free adaptive control algorithm. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 131008–131018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Zhong, L.; Qiang, Z.J. Research on usv heading control method based on kalman filter sliding mode control. In Proceedings of the 2020 Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Hefei, China, 22–24 August 2020; pp. 1547–1551. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z.; Hou, B.; Ning, J.; Lin, B.; Liu, Z. Collision Avoidance for Unmanned Surface Vehicles in Multi-Ship Encounters Based on Analytic Hierarchy Process–Adaptive Differential Evolution Algorithm. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Zhang, S.; Luo, M.; Ma, S. A mutation operator self-adaptive differential evolution particle swarm optimization algorithm for USV navigation. Front. Neurorobot. 2022, 16, 1076455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Sun, R.; Du, X. Path planning of mobile robots based on an improved particle swarm optimization algorithm. Processes 2022, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X. The Research on Collision Avoidance Path Planning of Unmanned Surface Vehicles Based on Improved Differential Evolution Algorithm. Master’s Thesis, Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China, 2024. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z.; Hou, B.; Ning, J.; Lin, B.; Liu, Z. Path Planning of USV Based on the Improved Differential Evolution Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 14th International Conference on Information Science and Technology (ICIST), Kopaonik, Serbia, 10–13 March 2024; pp. 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z.; Hou, B.; Ning, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z. Research on Intelligent Collision Avoidance and Obstacle Avoidance of Unmanned Surface Vehicle in Multi-Target Encounter Scenario. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 34178–34189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, T.; Cai, Y. Neural network-based adaptive control for ship course discrete-time nonlinear system. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 2016, 1, 123–126. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Li, T.; Shan, Q. Optimal adaptive fuzzy control for ship course discrete-time systems. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 2019, 40, 1576–1581. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ning, J.; Wang, H.; Hu, X.; Chen, C.P. Event-triggered Adaptive Coordinated Formation Control of Multiple Under-actuated Vehicles with Input and State Quantization. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Ahn, S.C.; Kwon, W.H. Computational complexity of general fuzzy logic control and its simplification for a loop controller. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2000, 111, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, E.; Liu, L.; Chen, C.P.; Tong, S. Fuzzy trajectory tracking control of under-actuated unmanned surface vehicles with ocean current and input quantization. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2024, 55, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Ma, Y.; Chen, C.P. Event-triggered-based distributed formation cooperative tracking control of under-actuated unmanned surface vehicles with input and state quantization. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 7081–7097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Ma, Y.; Li, T.; Chen, C.P.; Tong, S. Event-triggered based trajectory tracking control of under-actuated unmanned surface vehicle with state and input quantization. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 9, 3127–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.P.; Li, T. Neural network observer based adaptive trajectory tracking control strategy of unmanned surface vehicle with event-triggered mechanisms and signal quantization. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2025, 9, 3136–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | OS | TS |

|---|---|---|

| Length between perpendiculars/m | 189 | 105 |

| Beam/m | 27.8 | 18 |

| Draft/m | 11.0 | 5.4 |

| Block coefficient | 0.720 | 0.5595 |

| Rudder area/m2 | 38 | 11.8 |

| Water density/m3 | 1.025 | 1.025 |

| Displacement/t | 29,268.3 | 5735.5 |

| Metacentric height/m | 1.8 | −0.51 |

| Ship | Initial Heading/° | Initial Speed/kn | Distance from OS/n Mile |

|---|---|---|---|

| OS | 135° | 8 | 0 |

| TS | 0° | 8 | 6.90 |

| Obstacle | none | none | none |

| Algorithm | CRI-DE | DE |

|---|---|---|

| Average Fitness Value | 0.9597 | 1.0033 |

| Best Fitness Value | 0.8851 | 0.9512 |

| Fitness Std. Dev. | 0.4391 | 0.4539 |

| Computation Time/Seconds | 4.5780 | 3.6609 |

| Minimum Distance to Target Ship/Nautical Miles | 1.36 | 1.34 |

| Minimum Distance to Obstacle/Nautical Miles | 0.82 | 0.81 |

| Maximum Yaw Distance/Nautical Miles | 0.58 | 0.76 |

| Algorithm | CRI-DE | DE |

|---|---|---|

| Average Fitness Value | 1.2064 | 1.2796 |

| Best Fitness Value | 1.1476 | 1.2335 |

| Fitness Std. Dev. | 0.4867 | 0.4280 |

| Computation Time/Seconds | 4.5852 | 3.7689 |

| Minimum Distance to Target Ship/Nautical Miles | 1.20 | 1.22 |

| Minimum Distance to Obstacle/Nautical Miles | 0.85 | 0.81 |

| Maximum Yaw Distance/Nautical Miles | 0.71 | 0.71 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xiao, Z.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Z.; Yang, G. Path Planning and Tracking Control for Unmanned Surface Vehicle Based on Adaptive Differential Evolution Algorithm. Actuators 2026, 15, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010013

Xiao Z, Zhao J, Liu Z, Yang G. Path Planning and Tracking Control for Unmanned Surface Vehicle Based on Adaptive Differential Evolution Algorithm. Actuators. 2026; 15(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Zhongming, Jingyi Zhao, Zhengjiang Liu, and Guang Yang. 2026. "Path Planning and Tracking Control for Unmanned Surface Vehicle Based on Adaptive Differential Evolution Algorithm" Actuators 15, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010013

APA StyleXiao, Z., Zhao, J., Liu, Z., & Yang, G. (2026). Path Planning and Tracking Control for Unmanned Surface Vehicle Based on Adaptive Differential Evolution Algorithm. Actuators, 15(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010013