Benchmarking Robust AI for Microrobot Detection with Ultrasound Imaging

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Aims and Contributions

- Systematic performance benchmarking of six state-of-the-art multi-object detectors for microrobot detection using US imaging.

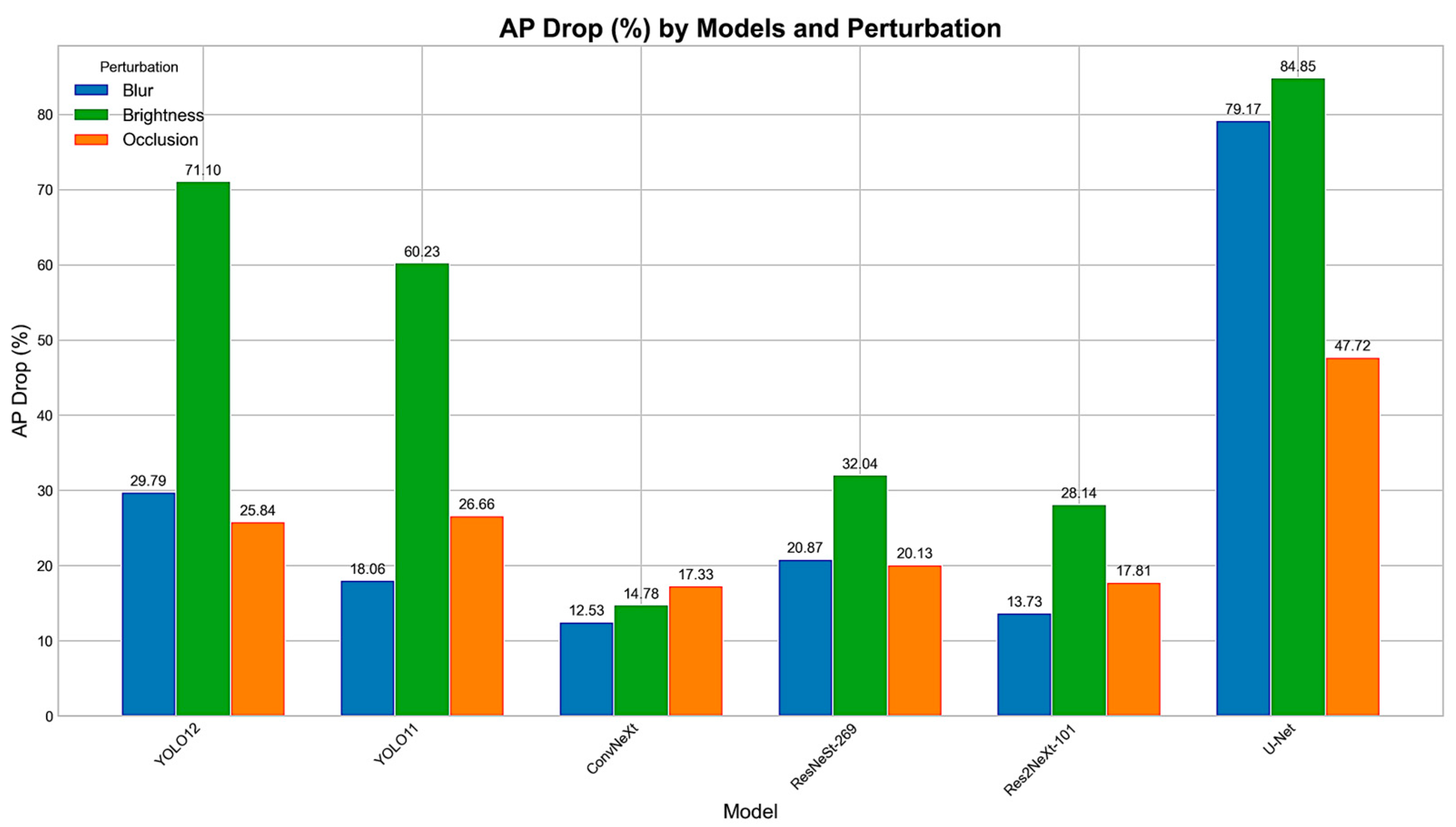

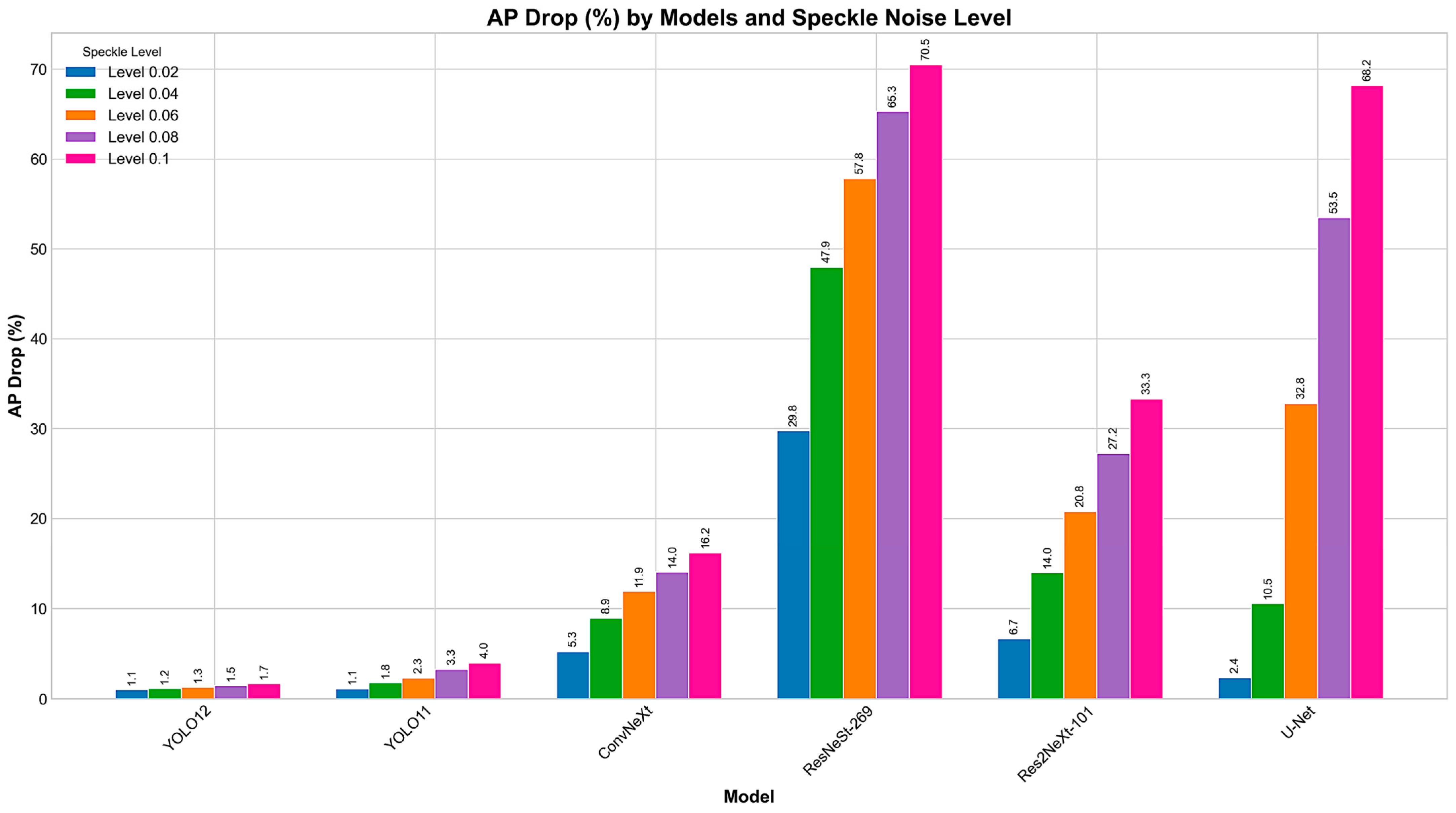

- Evaluation of the robustness of object detectors under realistic US imaging challenges, including blur, brightness variation, occlusion, and speckle noise.

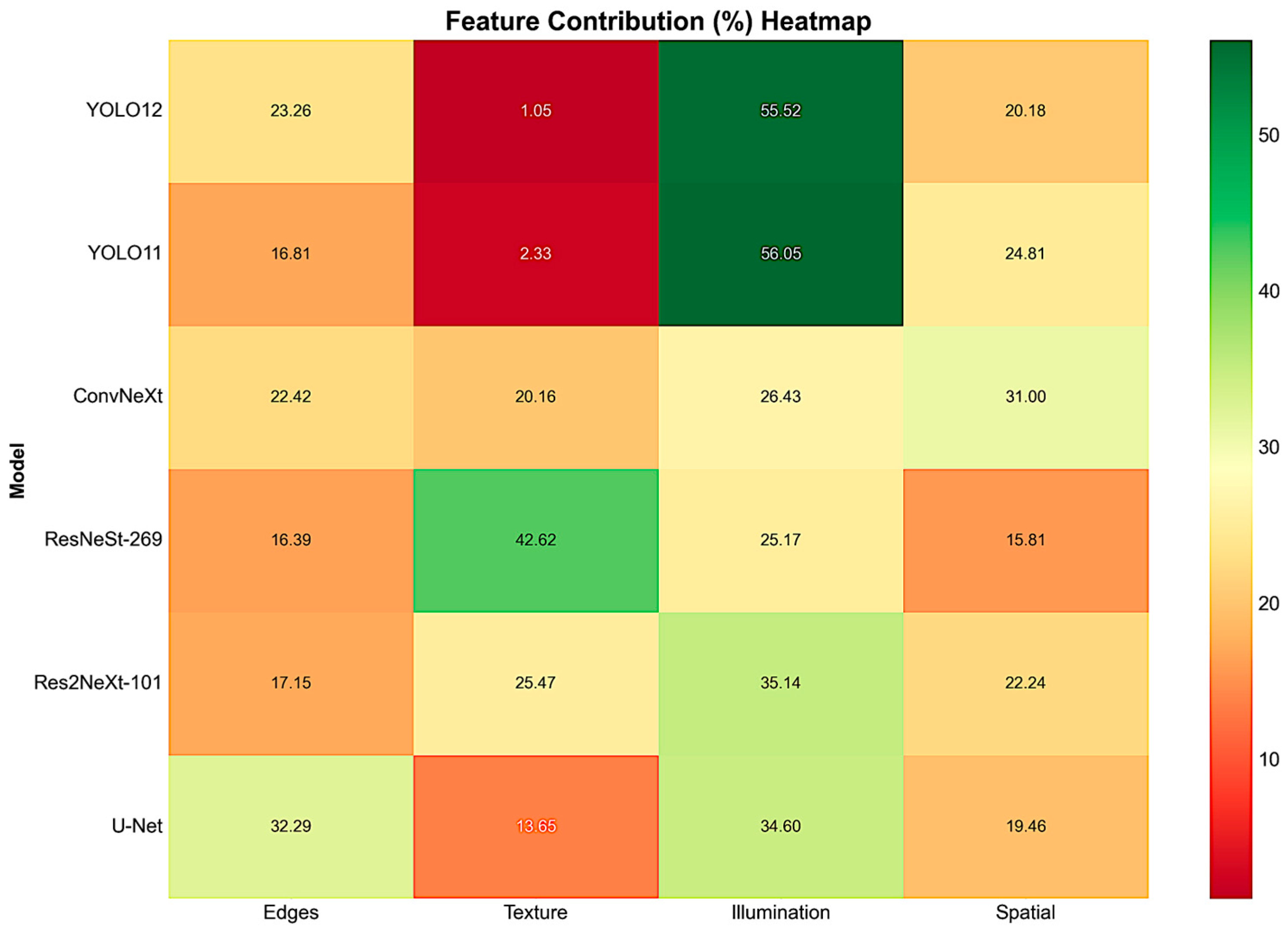

- Feature-level sensitivity analysis that quantifies the contributions of visual cues (edges, sharpness, textures, and regions) to detector performance.

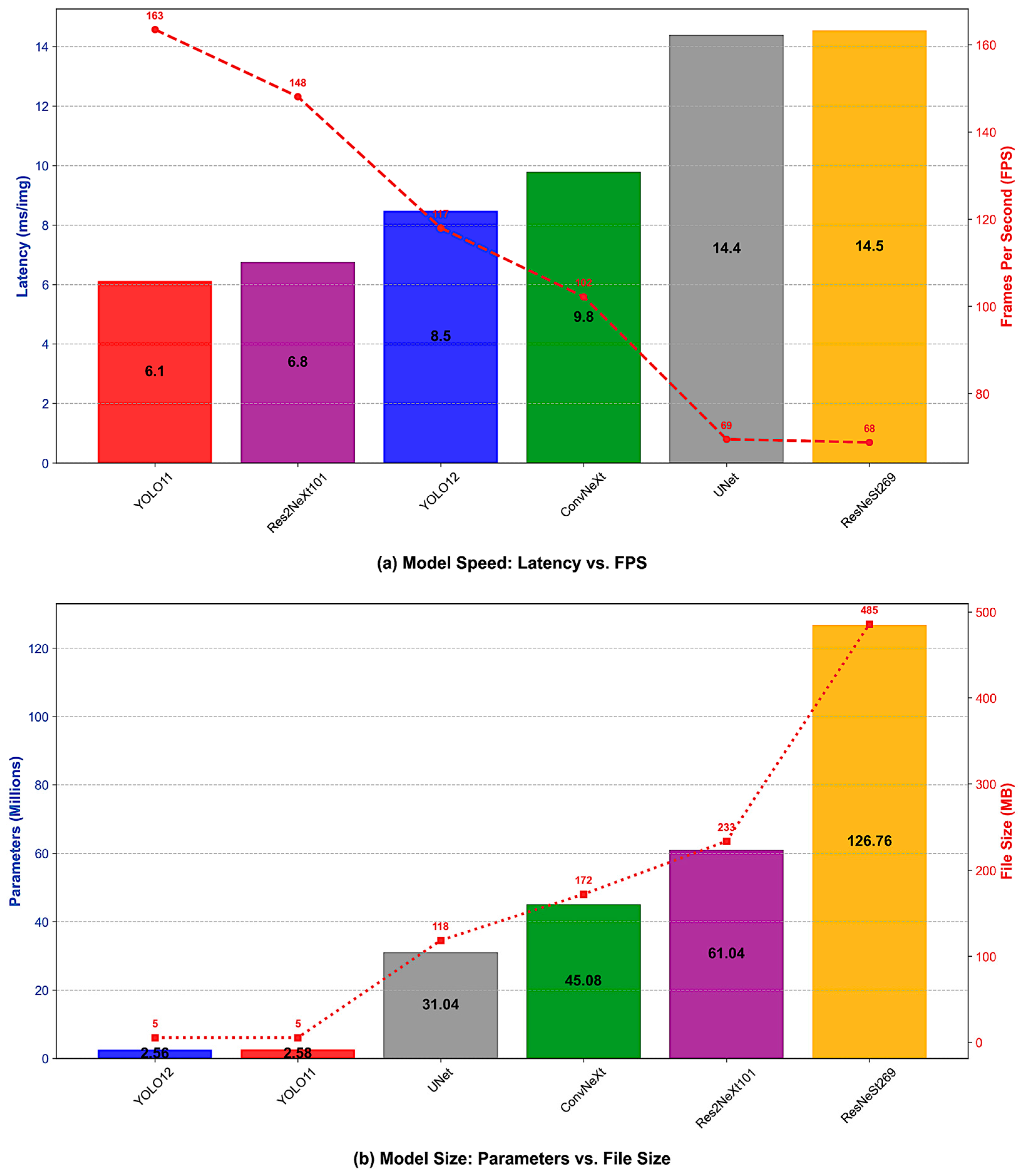

- Understand the detector’s efficiency and deployment feasibility by examining computational efficiency using metrics such as latency, frames per second (FPS), parameter count, and giga floating-point operations per second (GFLOPs).

1.2. Structure of the Paper

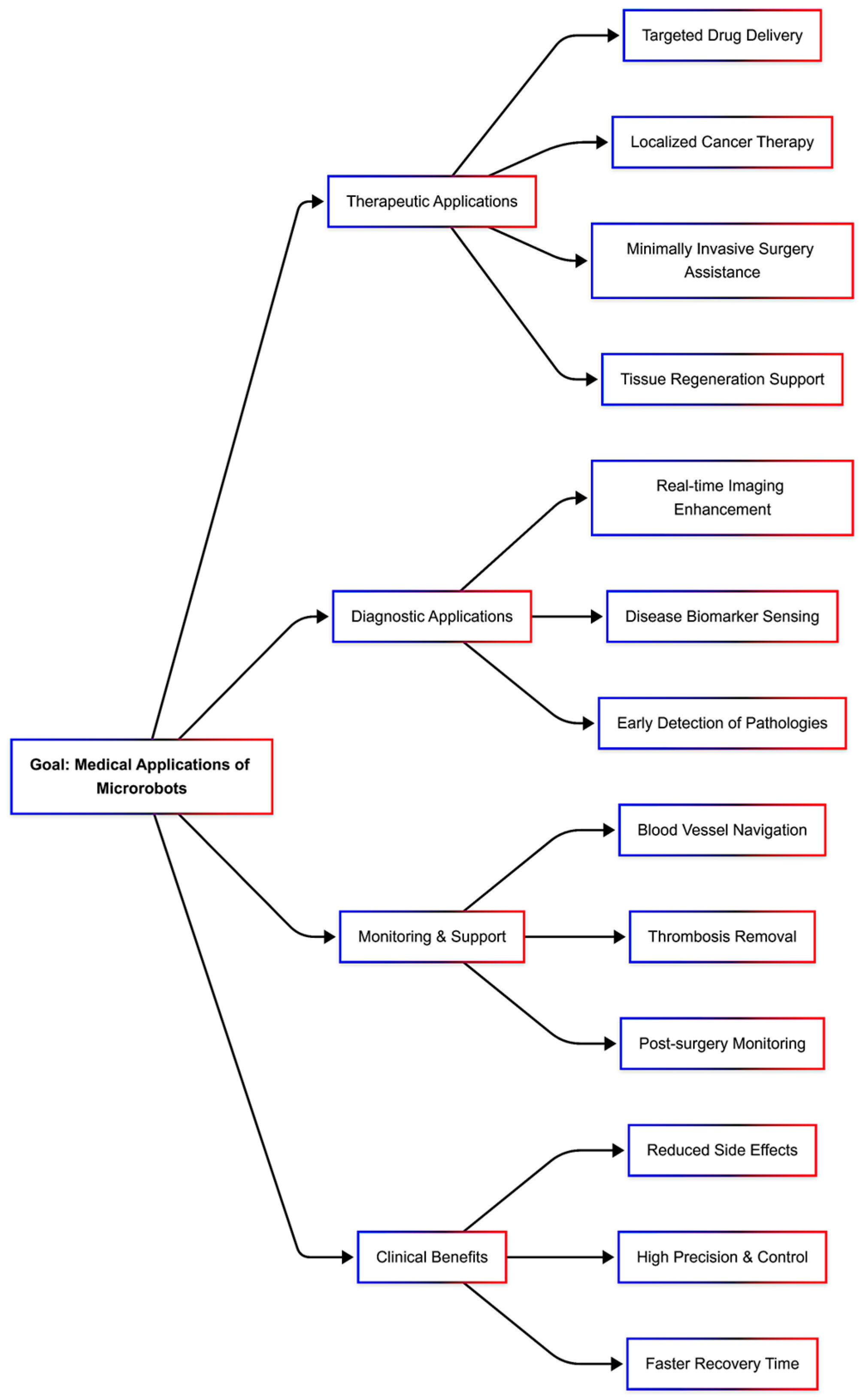

2. Literature Review

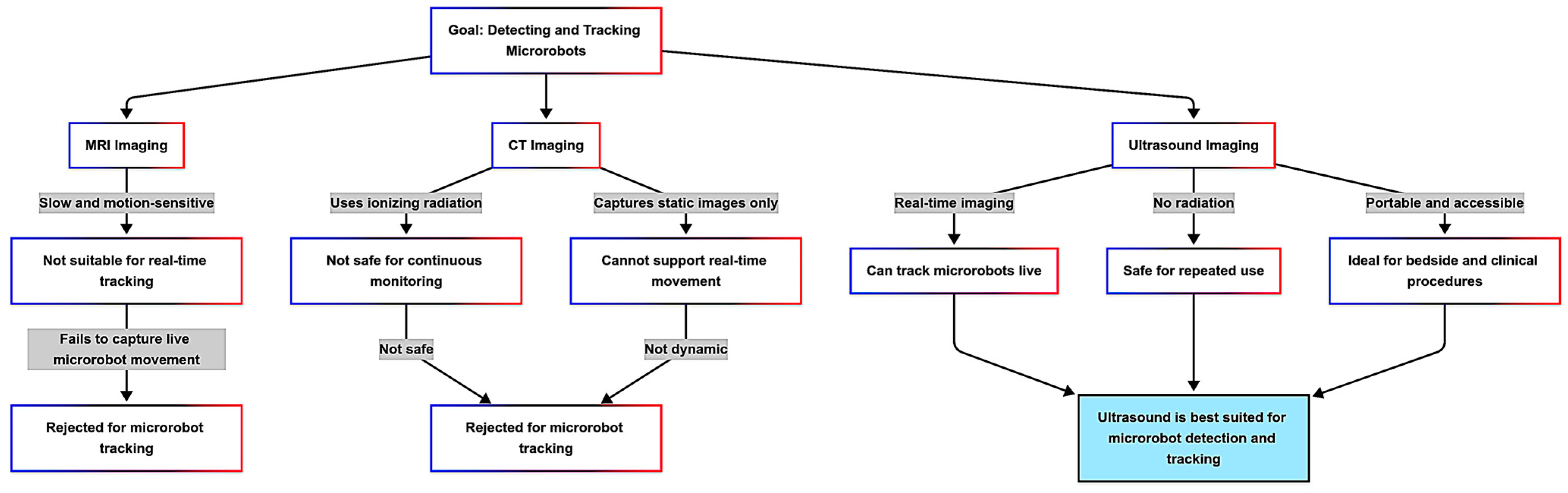

2.1. Why Ultrasound Imaging?

2.2. Microrobot Detection

3. Methodology

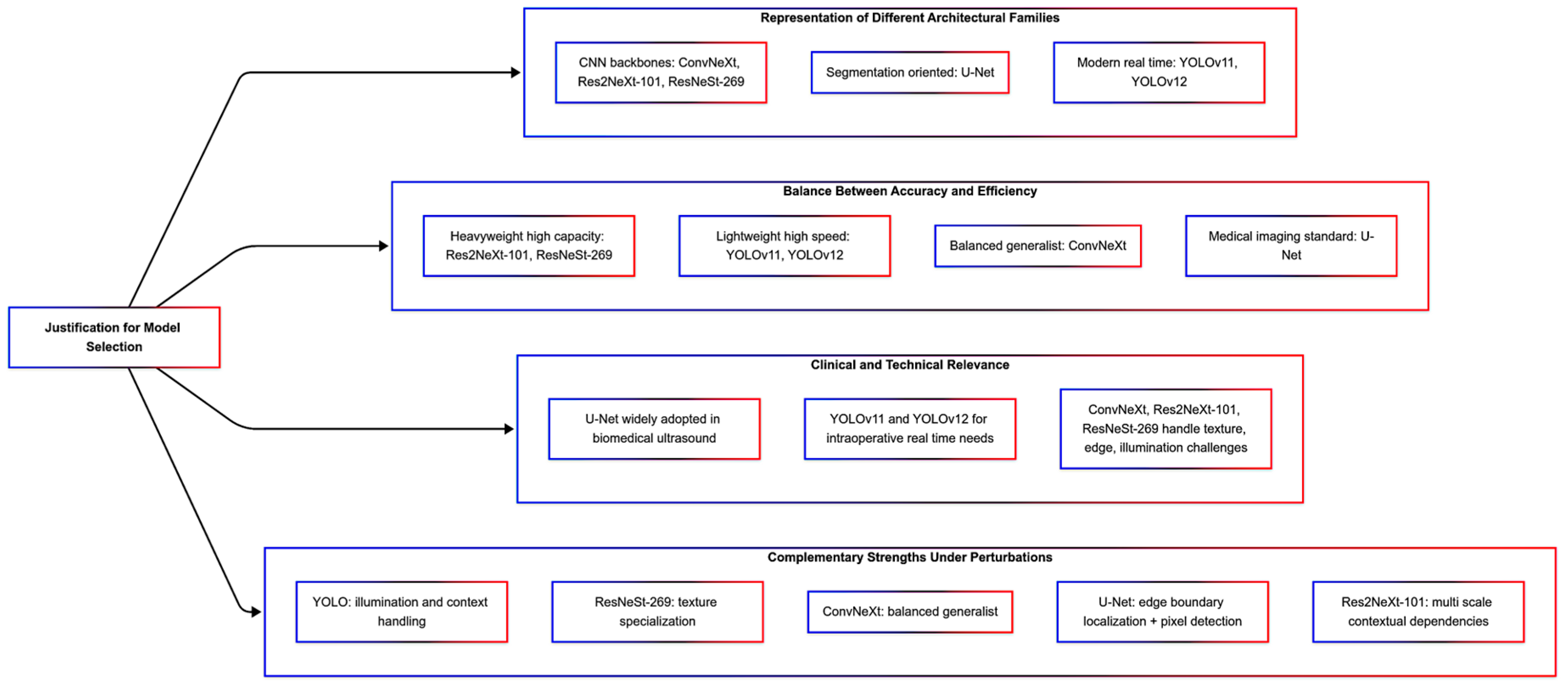

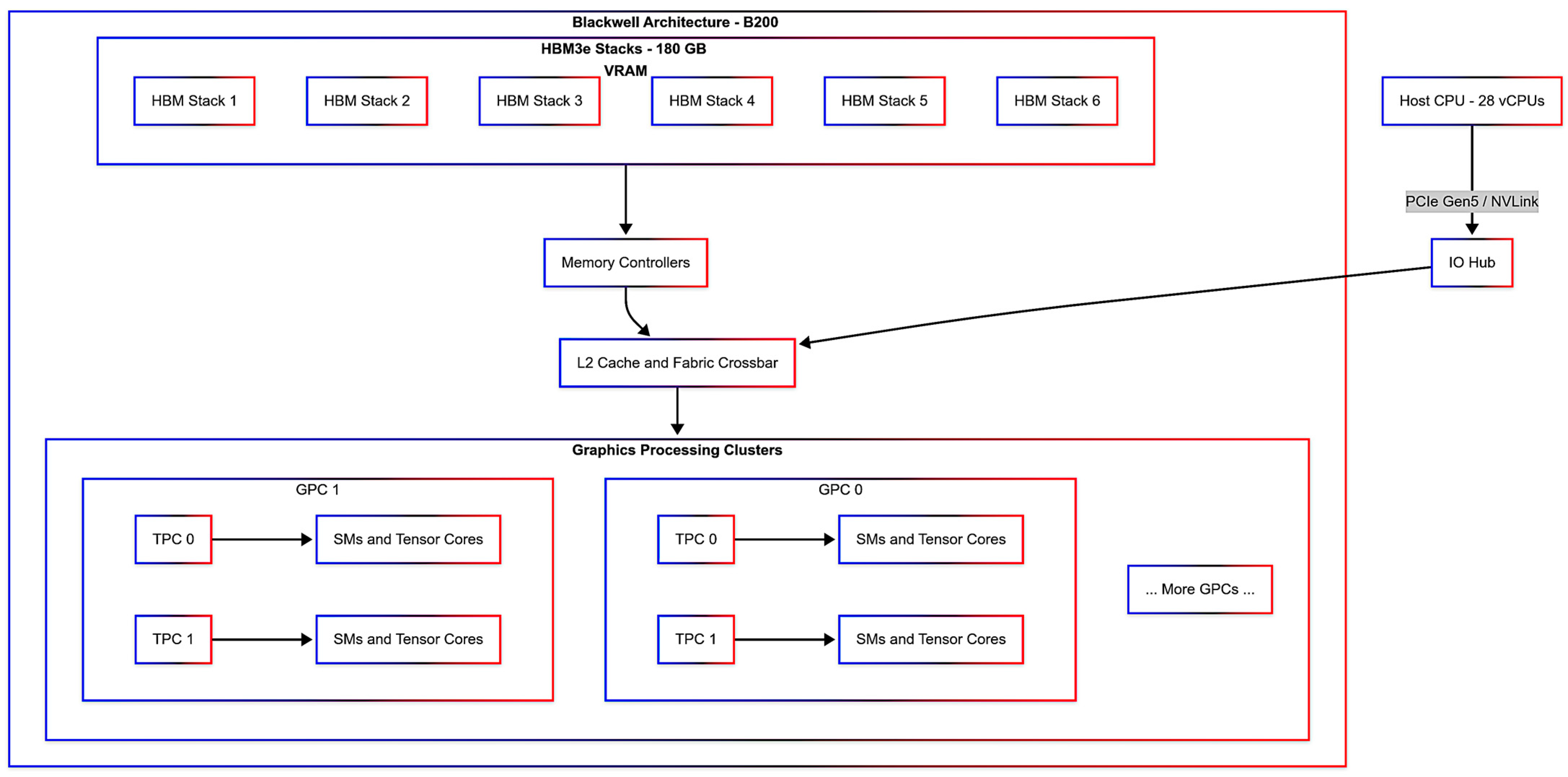

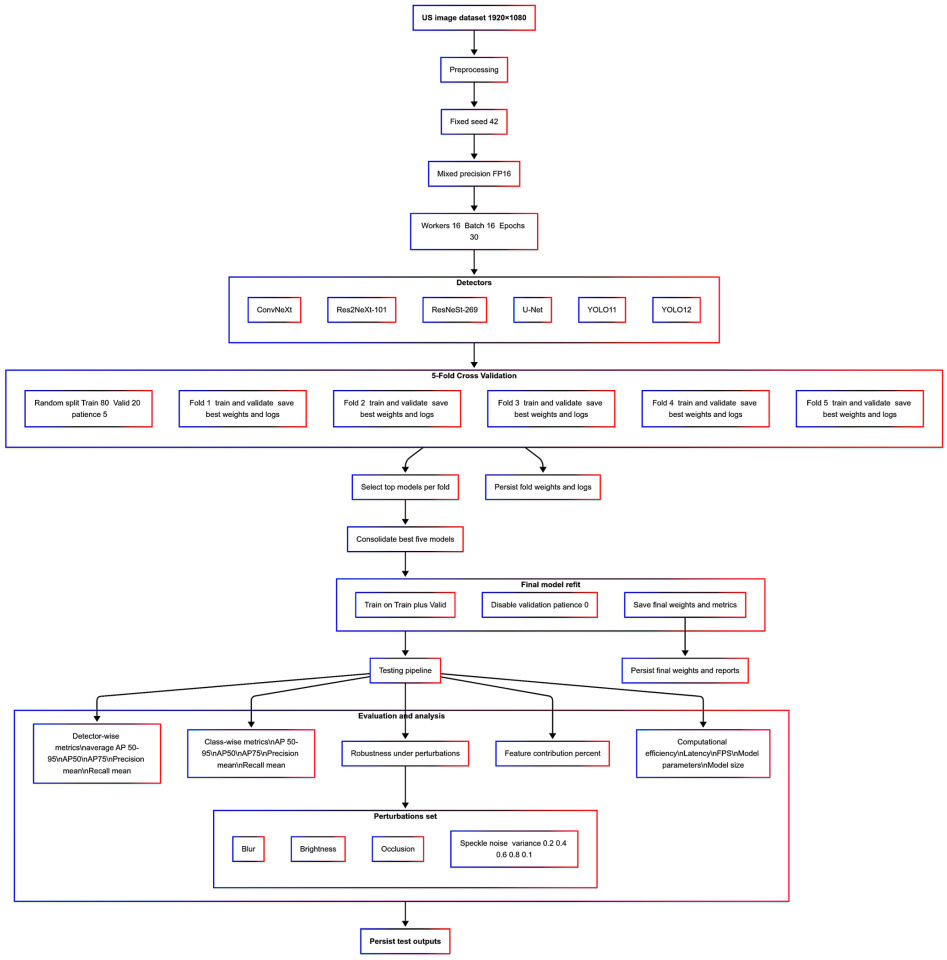

3.1. Experimental Setup

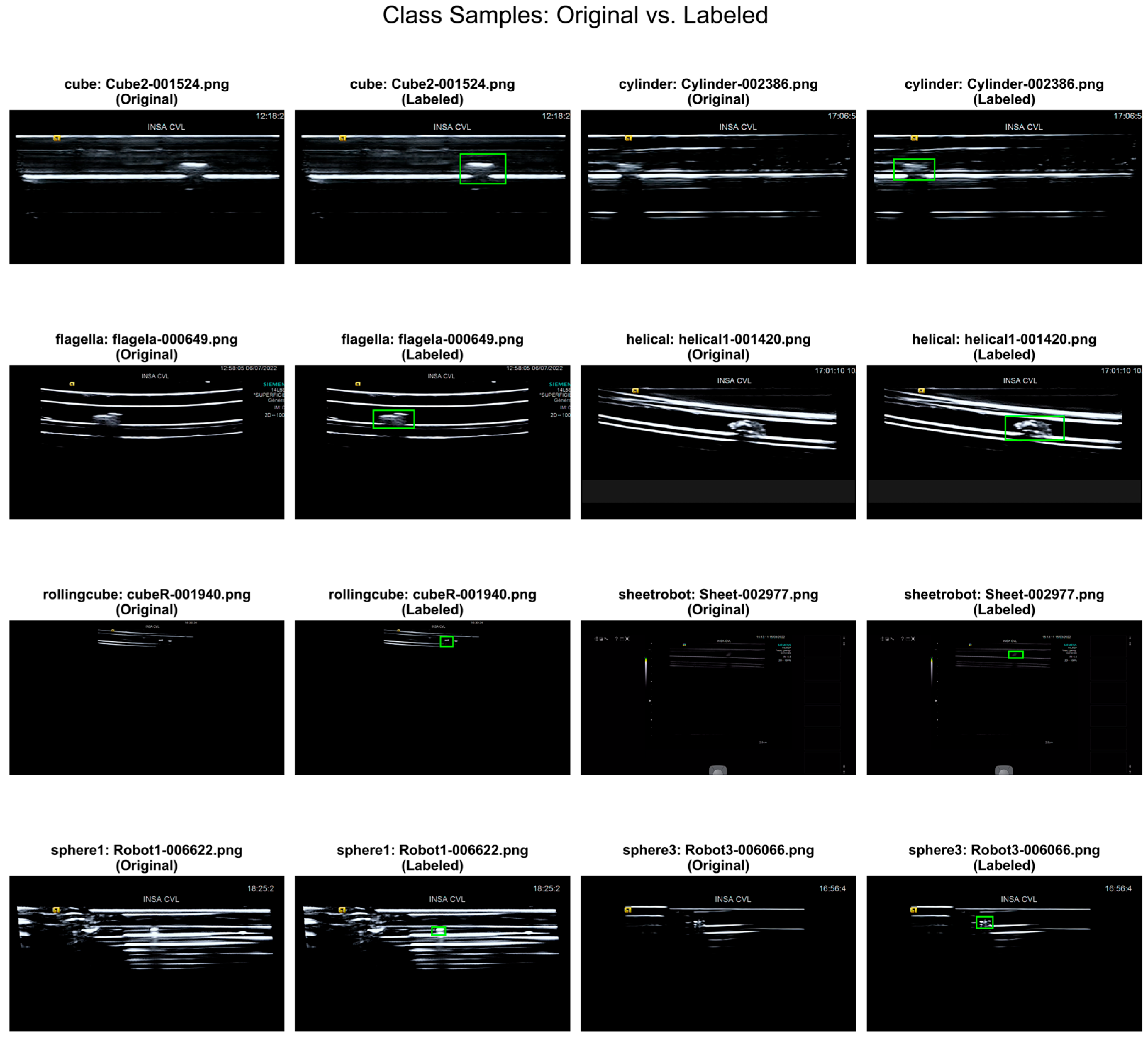

3.2. Dataset

3.3. Benchmarking Pipeline

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Classical Detection Metrics

4.2. Perturbations

4.3. Feature Contributions

4.4. Explainability

4.5. Computational Efficiency

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.; Li, C.; Dong, L.; Zhao, J. A Review of Microrobot’s System: Towards System Integration for Autonomous Actuation In Vivo. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, J.; Chang, H. Application of Micro/Nanorobot in Medicine. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1347312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacovacci, V.; Diller, E.; Ahmed, D.; Menciassi, A. Medical Microrobots. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 26, 561–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, C.K.; Medina-Sánchez, M.; Edmondson, R.J.; Schmidt, O.G. Engineering Microrobots for Targeted Cancer Therapies from a Medical Perspective. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Liu, J.; Yang, Z.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Du, X.; Fu, Y.; Song, P.; Yu, J. Microrobotic Swarms for Cancer Therapy. Research 2025, 8, 0686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Du, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, G. Development of Microrobot with Optical Magnetic Dual Control for Regulation of Gut Microbiota. Micromachines 2023, 14, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Jing, W.; Mehrmohammadi, M. Photoacoustic Imaging to Track Magnetic-Manipulated Micro-Robots in Deep Tissue. Sensors 2020, 20, 2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.G.; Raj, R.R.; Day, N.B.; Shields, C.W. Microrobots for Biomedicine: Unsolved Challenges and Opportunities for Translation. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 14196–14204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauber, R.; Goudu, S.R.; Goeckenjan, M.; Bornhäuser, M.; Ribeiro, C.; Medina-Sánchez, M. Medical Microrobots in Reproductive Medicine from the Bench to the Clinic. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakde, I.; Dhondge, P.; Bansode, D. Microrobotics a New Approach in Ocular Drug Delivery System: A Review. Prepr. Res. Sq. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Ding, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, B.; Yin, R.; Zhou, W.; Bi, Z.; Zhang, W. Development of 3D-Printed Magnetic Micro-Nanorobots for Targeted Therapeutics: The State of Art. Adv. NanoBiomed Res. 2023, 3, 2300018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanach, P.; Pena-Francesch, A.; Sheehan, D.; Bozuyuk, U.; Yasa, O.; Borros, S.; Sitti, M. Zwitterionic 3D-Printed Non-Immunogenic Stealth Microrobots. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2003013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L. An Automated Microrobotic Platform for Rapid Detection of C. Diff Toxins. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 67, 1517–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrede, P.; Degtyaruk, O.; Kalva, S.K.; Deán-Ben, X.L.; Bozuyuk, U.; Aghakhani, A.; Akolpoglu, B.; Sitti, M.; Razansky, D. Real-Time 3D Optoacoustic Tracking of Cell-Sized Magnetic Microrobots Circulating in the Mouse Brain Vasculature. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm9132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Yin, T.; Li, S.; Xu, T.; Ma, A.; Chen, Z.; Luo, Y.; Lai, Z.; Lv, Y.; Pan, H.; et al. Sequential Magneto-Actuated and Optics-Triggered Biomicrorobots for Targeted Cancer Therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2008262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiryaki, M.E.; Sitti, M. Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Based Tracking and Navigation of Submillimeter-Scale Wireless Magnetic Robots. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2022, 4, 2100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pane, S.; Iacovacci, V.; Sinibaldi, E.; Menciassi, A. Real-Time Imaging and Tracking of Microrobots in Tissues Using Ultrasound Phase Analysis. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 118, 014102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pane, S.; Iacovacci, V.; Ansari, M.H.D.; Menciassi, A. Dynamic Tracking of a Magnetic Micro-Roller Using Ultrasound Phase Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawhney, M.; Karmarkar, B.; Leaman, E.J.; Daw, A.; Karpatne, A.; Behkam, B. Motion Enhanced Multi-Level Tracker (MEMTrack): A Deep Learning-Based Approach to Microrobot Tracking in Dense and Low-Contrast Environments. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 6, 2300590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botros, K.; Alkhatib, M.; Folio, D.; Ferreira, A. USMicroMagSet: Using Deep Learning Analysis to Benchmark the Performance of Microrobots in Ultrasound Images. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 3254–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botros, K.; Alkhatib, M.; Folio, D.; Ferreira, A. Fully Automatic and Real-Time Microrobot Detection and Tracking Based on Ultrasound Imaging Using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 9763–9768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yi, X.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y. Magnetic-Controlled Microrobot: Real-Time Detection and Tracking through Deep Learning Approaches. Micromachines 2024, 15, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillinger, C.; Rasaiah, A.; Vogel, A.; Ahmed, D. Real-Time Color Flow Mapping of Ultrasound Microrobots. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H. Artificial Intelligence in Medical Ultrasonography: Driving on an Unpaved Road. Ultrasonography 2021, 40, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, F.; Plawiak, P.; Almaghthawi, A.; Qazani, M.R.C.; Mohanty, S.; Roohallah Alizadehsani, A. NeuroHAR: A Neuroevolutionary Method for Human Activity Recognition (HAR) for Health Monitoring. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 112232–112248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, F.; Mohammed Alnazzawi, T.S.; Mehmood, R.; Al-maghthawi, A. A Review of the Applications, Benefits, and Challenges of Generative AI for Sustainable Toxicology. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 2025, 8, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Song, X.; You, C.; Liu, X.; Li, L.; Chen, P.; Tang, X.; Feng, Z.; Liu, F.; Guo, Y.; et al. AI Meets Physics: A Comprehensive Survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawade, D.B.; Fapohunda, O.; Usman, S.O.; Akintayo, A.; Ige, A.O.; Adekunle, Y.A.; Adeola, A.O. Artificial Intelligence in Computational and Materials Chemistry: Prospects and Limitations. Chem. Afr. 2025, 8, 2707–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X. Applications of Deep Learning Method of Artificial Intelligence in Education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 1563–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, R.; Alam, F.; Albogami, N.N.; Katib, I.; Albeshri, A.; Altowaijri, S.M. UTiLearn: A Personalised Ubiquitous Teaching and Learning System for Smart Societies. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 2615–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Dastres, R. Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and Deep Learning in Advanced Robotics, a Review. Cogn. Robot. 2023, 3, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshanfar, M.; Salimi, M.; Kaboodrangi, A.H.; Jang, S.J.; Sinusas, A.J.; Wong, S.C.; Mosadegh, B. Advanced Robotics for the Next-Generation of Cardiac Interventions. Micromachines 2025, 16, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Du, X.; Wu, H.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H.L.; Zhang, J. Review of Artificial Intelligence Applications in Astronomical Data Processing. Astron. Tech. Instrum. 2024, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.M.; Brunetti, A.; Lucarelli, G.; Memeo, R.; Bevilacqua, V.; Buongiorno, D. Deep Learning Based Image Processing for Robot Assisted Surgery: A Systematic Literature Survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 122627–122657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Duelmer, F.; Huang, D.; Navab, N. Machine Learning in Robotic Ultrasound Imaging: Challenges and Perspectives. Annu. Rev. Control Robot. Auton. Syst. 2024, 7, 335–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshanfar, M.; Salimi, M.; Jang, S.J.; Sinusas, A.J.; Kim, J.; Mosadegh, B. Emerging Image-Guided Navigation Techniques for Cardiovascular Interventions: A Scoping Review. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, W.; Zhang, X.; Luo, J.; Pan, F.; Liang, J.; Huang, H.; Li, M.; Cheng, M.; Pan, J.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Value of Multimodality Imaging in the Diagnosis of Breast Lesions with Calcification: A Retrospective Study. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2020, 76, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, C.W.J.; Zhou, G.Q.; Law, S.Y.; Mak, T.M.; Lai, K.L.; Zheng, Y.P. Ultrasound Volume Projection Imaging for Assessment of Scoliosis. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2015, 34, 1760–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinene, B.; Mudadi, L.-s.; Mutasa, F.E.; Nyawani, P. A Survey of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Availability and Cost in Zimbabwe: Implications and Strategies for Improvement. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 2025, 56, 101819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, S.; Ding, H.; Adedeji, F.; Qin, C.; Obungoloch, J.; Asllani, I.; Anazodo, U.; Ntusi, N.A.B.; Mammen, R.; Niendorf, T.; et al. Bringing MRI to Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Directions, Challenges and Potential Solutions. NMR Biomed. 2024, 37, e4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, A.; Açıkgöz, G.; Yavuz, A.; Bulut, D. Computed Tomography: Are We Aware of Radiation Risks in Computed Tomography? East. J. Med. 2014, 19, 164–168. [Google Scholar]

- Power, S.P.; Moloney, F.; Twomey, M.; James, K.; O’Connor, O.J.; Maher, M.M. Computed Tomography and Patient Risk: Facts, Perceptions and Uncertainties. World J. Radiol. 2016, 8, 1567–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojkovic, M.; Rosenberger, K.; Kauczor, H.U.; Junghanss, T.; Hosch, W. Diagnosing and Staging of Cystic Echinococcosis: How Do CT and MRI Perform in Comparison to Ultrasound? PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 6, e1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcello Scotti, F.; Stuepp, R.T.; Dutra-Horstmann, K.L.; Modolo, F.; Gusmão Paraiso Cavalcanti, M. Accuracy of MRI, CT, and Ultrasound Imaging on Thickness and Depth of Oral Primary Carcinomas Invasion: A Systematic Review. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2022, 51, 20210291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, B.B.; Ros, P.R.; Abbitt, P.L.; Kerns, S.R.; Sabatelli, F.W. Comparison of Ultrasound, CT, and MR Imaging in the Evaluation of Candidates for TIPS. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 1995, 5, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Jing, Y.; Xu, C.; Wang, X.; Xie, X.; Zhu, Y.; Dai, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Yu, S. Medical Imaging Technology for Micro/Nanorobots. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, L. Ultrasound Imaging and Tracking of Micro/Nanorobots: From Individual to Collectives. IEEE Open J. Nanotechnol. 2020, 1, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Zhang, J.; Shao, Y.; Liu, J.; Shi, K.; He, C.; Kong, D. Deep Learning-Based Medical Ultrasound Image and Video Segmentation Methods: Overview, Frontiers, and Challenges. Sensors 2025, 25, 2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadak, F. An Explainable Deep Learning Model for Automated Classification and Localization of Microrobots by Functionality Using Ultrasound Images. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2025, 183, 104841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhang, J.; Matkovic, L.; Liu, T.; Yang, X. Reinforcement Learning in Medical Image Analysis: Concepts, Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2023, 24, e13898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, C.; Wu, M.; Ping, A.; Zavodni, A.; Matsuura, N.; Diller, E. Transformer-Based Robotic Ultrasound 3D Tracking for Capsule Robot in GI Tract. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2025, 20, 2011–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, R.; Kazerouni, A.; Heidari, M.; Aghdam, E.K.; Molaei, A.; Jia, Y.; Jose, A.; Roy, R.; Merhof, D. Advances in Medical Image Analysis with Vision Transformers: A Comprehensive Review. Med. Image Anal. 2024, 91, 103000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medany, M.; Piglia, L.; Achenbach, L.; Mukkavilli, S.K.; Ahmed, D. Model-Based Reinforcement Learning for Ultrasound-Driven Autonomous Microrobots. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2025, 7, 1076–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrage, M.; Medany, M.; Ahmed, D. Ultrasound Microrobots with Reinforcement Learning. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2201702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Esser, D.; Wagstaff, B.; Zavodni, A.; Matsuura, N.; Kelly, J.; Diller, E. Capsule Robot Pose and Mechanism State Detection in Ultrasound Using Attention-Based Hierarchical Deep Learning. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 11966–11976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.H.; Cheng, M.M.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, X.Y.; Yang, M.H.; Torr, P. Res2Net: A New Multi-Scale Backbone Architecture. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y.; He, T.; Mueller, J.; Manmatha, R.; et al. ResNeSt: Split-Attention Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, W.; Zhu, X. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. IEEE Access 2015, 9, 16591–16603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLO11. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolo11/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; Doermann, D. YOLOv12: Attention-Centric Real-Time Object Detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauber, R.; Hoppe, J.; Robles, D.C.; Medina-Sánchez, M. Photoacoustics-Guided Real-Time Closed-Loop Control of Magnetic Microrobots through Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the MARSS 2024—7th International Conference on Manipulation, Automation, and Robotics at Small Scales, Delft, The Netherlands, 1–5 July 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, M.; Hamza, H.M.; Hosny, K.M. De-Speckling of Medical Ultrasound Image Using Metric-Optimized Knowledge Distillation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value/Setting | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Epochs | 30 | Ensures equal training duration across architectures |

| Batch Size | 16 | Maintains identical gradient update frequency |

| Dataloader Workers | 16 | Ensures equal data throughput efficiency |

| Input Resolution | 1080 × 1920 (rectangular)/YOLO imgsz = 1920 | Same image scale for consistent feature learning |

| Optimizer | AdamW | Same optimization behavior across networks |

| Learning Rate | 0.0001 | Uniform learning dynamics |

| Mixed Precision (AMP) | Enabled | Same precision & GPU acceleration method |

| Model Compilation | torch.compile/compile = True | Equal computational optimization |

| Class Name | Training Count | Testing Count |

|---|---|---|

| cube | 2267 | 1222 |

| cylinder | 1596 | 861 |

| flagella | 1956 | 1054 |

| helical | 3155 | 1699 |

| rollingcube | 1255 | 677 |

| sheetrobot | 3010 | 1622 |

| sphere1 | 5900 | 3178 |

| sphere3 | 1988 | 1071 |

| Total | 21,127 | 11,384 |

| Detectors Launch Year | Key Innovation | Strength for Ultrasound Microrobot Detection | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| YOLO12 (2025) | Attention-centric modules (Area Attention, R-ELAN) | Improves contextual awareness and fine-grained discrimination, even if the background is noisy | supporting trustworthy clinical decision-making by maximizing precision in challenging imaging conditions |

| YOLO11 (2024) | Improved backbone–neck design, multi-task capability. | Greater adaptability for handling complex microrobot appearances and dynamics in ultrasound. | Supports advanced applications related to monitoring and controlling microrobot behavior. |

| ConvNeXt (2022) | The transformer-inspired CNN architecture uses large kernels, depthwise convolutions, and normalization improvements. | Robust hierarchical feature extraction, speckle noise handling, and low contrast in ultrasound. | Provides reliable baseline detection and supports fusion with more advanced detectors. |

| ResNeSt-269 (2020) | Split-attention blocks for channel-wise feature recalibration | Enhances robustness to background clutter in ultrasound by selectively emphasizing informative channels. | Supports precise localization of microrobots amidst complex tissue structures. |

| Res2NeXt-101 (2019) | Combines ResNeXt split-transform-merge strategy with Res2Net multi-scale feature representation. | Able to capture fine-to-coarse structural details, which results in better detection of varying sizes and shapes of microrobots. | Enables the accurate identification of diverse microrobot morphologies, which is crucial for heterogeneous robotic swarms. |

| U-Net (2015) | Symmetric encoder–decoder with skip connections for biomedical image segmentation. | During noisy ultrasound scans, it provides strong boundary delineation of microrobots. | Widely adopted in medical imaging, it facilitates accurate segmentation for monitoring the interactions of microrobots with tissue. |

| Model | mAP (50–95) | mAP50 | mAP75 | Precision (Mean) | Recall (Mean) | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLO12 | 0.617824433 | 0.962943476 | 0.670267625 | 0.93580446 | 0.840348152 | 0.5591 | 0.6126 |

| YOLO11 | 0.613175223 | 0.949897181 | 0.690278055 | 0.962045926 | 0.769022882 | 0.3186 | 0.7536 |

| ConvNeXt | 0.866752148 | 0.98678273 | 0.916006863 | 0.985324123 | 0.995195712 | 0.7955 | 0.8484 |

| ResNeSt269 | 0.878249645 | 0.988578439 | 0.930365086 | 0.986016259 | 0.995728513 | 0.8219 | 0.8515 |

| Res2NeXt-101 | 0.866416454 | 0.988445342 | 0.919016898 | 0.985829465 | 0.995924184 | 0.8211 | 0.8563 |

| U-Net | 0.7309196 | 0.875163198 | 0.781938016 | 0.7309196 | 0.880745351 | 0.732 | 0.8141 |

| Detectors | ClassName | mAP_50–95 | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLO12 | cube | 0.806887618 | 0.965999001 | 0.976479533 | 0.971210994 |

| cylinder | 0.575627952 | 0.913242006 | 0.977932636 | 0.944480898 | |

| flagella | 0.687789202 | 0.923809947 | 0.9971537 | 0.959081665 | |

| helical | 0.7488874 | 0.921603437 | 0.987639788 | 0.953479589 | |

| rollingcube | 0.473179148 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| sheetrobot | 0.389423904 | 0.844249491 | 0.825443706 | 0.834740694 | |

| sphere1 | 0.58550647 | 0.969081873 | 0.966539217 | 0.967808875 | |

| sphere3 | 0.675293773 | 0.948449929 | 0.991596639 | 0.969543491 | |

| YOLO11 | cube | 0.754743564 | 0.991617812 | 0.968089958 | 0.97971265 |

| cylinder | 0.624071655 | 0.937022061 | 0.975609756 | 0.955926652 | |

| flagella | 0.706563798 | 0.988828166 | 0.996204934 | 0.992502843 | |

| helical | 0.77122878 | 0.98956242 | 0.994114185 | 0.99183308 | |

| rollingcube | 0.436169457 | 1 | 0.002394288 | 0.004777139 | |

| sheetrobot | 0.419482015 | 0.859680018 | 0.827373613 | 0.843217488 | |

| sphere1 | 0.577313013 | 0.980651387 | 0.971365639 | 0.975986427 | |

| sphere3 | 0.615829503 | 0.949005542 | 0.417030685 | 0.579434752 | |

| ConvNeXt | cube | 0.969044566 | 0.971360382 | 0.999181669 | 0.985074627 |

| cylinder | 0.873152435 | 0.988399072 | 0.989547038 | 0.988972722 | |

| flagella | 0.906403005 | 0.994334278 | 0.999051233 | 0.996687175 | |

| helical | 0.947784066 | 0.996472663 | 0.997645674 | 0.997058824 | |

| rollingcube | 0.939757824 | 0.995575221 | 0.99704579 | 0.996309963 | |

| sheetrobot | 0.858920813 | 0.954896142 | 0.991985203 | 0.97308739 | |

| sphere1 | 0.588896036 | 0.988976378 | 0.988042794 | 0.988509366 | |

| sphere3 | 0.850058556 | 0.99257885 | 0.999066293 | 0.995812006 | |

| ResNeSt-269 | cube | 0.966920018 | 0.957647059 | 0.999181669 | 0.977973568 |

| cylinder | 0.877728045 | 0.993039443 | 0.994192799 | 0.993615786 | |

| flagella | 0.919314921 | 0.998104265 | 0.999051233 | 0.998577525 | |

| helical | 0.953000605 | 0.997648442 | 0.998822837 | 0.998235294 | |

| rollingcube | 0.93028307 | 0.99704579 | 0.99704579 | 0.99704579 | |

| sheetrobot | 0.878918886 | 0.95317131 | 0.991368681 | 0.971894832 | |

| sphere1 | 0.650590539 | 0.992407466 | 0.987098804 | 0.989746017 | |

| sphere3 | 0.849241078 | 0.999066293 | 0.999066293 | 0.999066293 | |

| Res2NeXt-101 | cube | 0.964771032 | 0.971360382 | 0.999181669 | 0.985074627 |

| cylinder | 0.868212938 | 0.987312572 | 0.994192799 | 0.990740741 | |

| flagella | 0.890216649 | 0.997159091 | 0.999051233 | 0.998104265 | |

| helical | 0.948049784 | 0.997647059 | 0.998234255 | 0.997940571 | |

| rollingcube | 0.941604495 | 0.99704579 | 0.99704579 | 0.99704579 | |

| sheetrobot | 0.861603558 | 0.952690716 | 0.993218249 | 0.972532448 | |

| sphere1 | 0.609460592 | 0.990834387 | 0.986469478 | 0.988647114 | |

| sphere3 | 0.847412467 | 0.992585728 | 1 | 0.99627907 | |

| U-Net | cube | 0.580823183 | 0.580823183 | 0.580823183 | 0.580823183 |

| cylinder | 0.820490539 | 0.820490539 | 0.820490539 | 0.820490539 | |

| flagella | 0.787256718 | 0.787256718 | 0.787256718 | 0.787256718 | |

| helical | 0.762020171 | 0.762020171 | 0.762020171 | 0.762020171 | |

| rollingcube | 0.887949109 | 0.887949109 | 0.887949109 | 0.887949109 | |

| sheetrobot | 0.647820532 | 0.647820532 | 0.647820532 | 0.647820532 | |

| sphere1 | 0.573726833 | 0.573726833 | 0.573726833 | 0.573726833 | |

| sphere3 | 0.787269592 | 0.787269592 | 0.787269592 | 0.787269592 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Almaghthawi, A.; He, C.; Luo, S.; Alam, F.; Roshanfar, M.; Cheng, L. Benchmarking Robust AI for Microrobot Detection with Ultrasound Imaging. Actuators 2026, 15, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010016

Almaghthawi A, He C, Luo S, Alam F, Roshanfar M, Cheng L. Benchmarking Robust AI for Microrobot Detection with Ultrasound Imaging. Actuators. 2026; 15(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmaghthawi, Ahmed, Changyan He, Suhuai Luo, Furqan Alam, Majid Roshanfar, and Lingbo Cheng. 2026. "Benchmarking Robust AI for Microrobot Detection with Ultrasound Imaging" Actuators 15, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010016

APA StyleAlmaghthawi, A., He, C., Luo, S., Alam, F., Roshanfar, M., & Cheng, L. (2026). Benchmarking Robust AI for Microrobot Detection with Ultrasound Imaging. Actuators, 15(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010016