Abstract

High-precision position control and pressure control are core performance requirements for modern electro-hydraulic actuators. While the design of controllers for high-performance position servo systems is relatively straightforward, the development of pressure control strategies for electro-hydraulic actuators poses substantially greater challenges. This is primarily due to the fact that unknown time-varying parameters, load dynamics, and sensor-induced measurement noise within the system drastically deteriorate the performance of the closed-loop system. To address these challenges, this study proposes an adaptive output feedback pressure controller specifically tailored for electro-hydraulic servo systems. This controller not only exhibits insensitivity to dynamic load disturbances but also effectively mitigates the adverse effects of time-varying parameters and sensor measurement noise. Theoretical analysis demonstrates that the proposed controller can guarantee the asymptotic stability of the system’s tracking error. Furthermore, detailed simulation and experimental results are presented to validate the superiority of the designed controller over conventional control strategies.

1. Introduction

The core control challenges of electro-hydraulic servo systems can be divided into two primary categories: position control and force control. Force control for these systems has been widely applied in industries such as material testing, active suspension, and injection molding [1,2,3,4]. However, most existing literature focuses primarily on position control [5,6,7], with relatively little attention paid to force control-related issues. As reported in [8], traditional proportional–integral–derivative (PID) controllers have significant limitations when addressing force control in hydraulic systems. Moreover, in specific application scenarios, the output force at the actuator end may not be directly measurable. In such cases, the force control problem of the servo system is converted into an equivalent pressure control problem.

To enhance the robustness of electro-hydraulic servo systems against parameter uncertainties and external disturbances, adaptive robust control has been proposed [9], and this approach has subsequently been applied to various hydraulic servo systems [10,11,12,13,14]. Xiao [15] addressed the force tracking problem of single-rod hydraulic cylinders by developing a composite nonlinear control method based on sliding mode control. This method divides the entire system into linear and nonlinear subsystems, designs corresponding sliding mode reaching laws for each subsystem, and forces the nonlinear subsystem output to track the desired virtual input of the linear subsystem. Shen [16] designed a composite controller integrating offline feedback control and online adaptive compensation to solve the force tracking problem of electro-hydraulic servo systems. For accurate pressure loading on the steering test bench of heavy-duty vehicles, Du [17] developed a sliding mode controller, with experiments verifying its effectiveness in suppressing external disturbances. To resolve force loading disturbances in electro-hydraulic systems, Tang [18] proposed a real-time nonlinear adaptive force control strategy. During controller design, they considered the nonlinearity of the servo valve and parameter uncertainties of typical electro-hydraulic systems, and used vibration disturbance information of the actuator to achieve accurate force tracking. Dakova [19] developed a force tracking controller for valve-controlled hydraulic cylinder systems, where the controller’s proportional gain is adjusted in real time via a gain scheduling algorithm based on the dynamic characteristics of the reference signal. This avoids control gain overflow caused by mechanical coupling between the actuator and the structure. Flayyih [20] adopted a non-standard backstepping sliding mode control method to design a virtual force tracking control algorithm for hydraulic actuators in automotive active suspension systems. Leveraging the sliding mode algorithm’s insensitivity to matched disturbances, system nonlinearities, parameter uncertainties, and road disturbances are effectively suppressed—significantly improving cockpit comfort and safety. For the electro-hydraulic control loading system in flight simulators, researchers also have proposed many methods, such as robust feedforward observer-based force control method [21], torque tracking control method based on singular perturbation theory [22] and observer-based backstepping control strategy [23]. All these methods effectively enhance the dynamic loading performance of load simulators. However, most of the aforementioned controllers only address time-invariant parameter uncertainties. For electro-hydraulic servo systems, many physical parameters change with the operating environment. Furthermore, none of these controllers consider the impact of sensor noise on system control performance which may greatly limiting the application scope of the designed control algorithms.

To address sensor noise and unmeasurable system states, numerous observer-based control strategies have been proposed for electro-hydraulic servo systems [24,25,26,27,28]. Reference [29] presents a novel control strategy that estimates actuator chamber pressures from work port pressures using differential equations, eliminating the need for direct pressure or position sensors. The controller dynamically adjusts gains through fuzzy logic-based gain scheduling, enhancing adaptability across a wide range of operating conditions. Reference [30] proposes an active disturbance rejection control method for electro-hydraulic servo systems, which employs a disturbance observer based on an extended state observer (ESO). Here, the ESO estimates the system’s unknown states and disturbances, while the disturbance observer reconstructs the system’s mismatched disturbances. Reference [31] puts forward two motion control strategies for electro-hydraulic servo systems using linear extended state observers (LESOs). These observers are specifically designed to compensate for system uncertainties, thereby effectively enhancing system robustness. To reduce the impact of measurement noise on velocity signals, Reference [31] also uses an LESO to reconstruct actuator velocity, and adopts a parameter adaptive mechanism to mitigate the influence of parameter uncertainties on system performance. Theoretical analysis shows that this control method can guarantee transient performance and predefined final tracking accuracy even in the presence of time-varying uncertainties. Notably, the ESOs used in References [30,31] are linear in structure. While they offer advantages such as simple architecture and convenient parameter tuning, they are highly sensitive to measurement noise. Designers must therefore make a trade-off between the observer’s estimation accuracy and its ability to suppress measurement noise. Thus, how to design a robust control strategy for electro-hydraulic servo pressure control systems that simultaneously accounts for measurement noise, time-varying parameter uncertainties, and external disturbances remains a highly challenging task.

Building on the aforementioned research, this paper proposes an adaptive output feedback pressure control method for electro-hydraulic servo systems. This method simultaneously accounts for the system’s time-varying parameter uncertainties, measurement noise, and external disturbances, while ensuring the asymptotic stability of the system’s tracking error. Compared with existing research methods, the main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

(1) A pressure control method for electro-hydraulic servo systems based on a parameter adaptive mechanism is developed. Unlike existing parameter adaptation methods, the parameter adaptation mechanism designed in this paper is capable of addressing the adverse effects of time-varying parameters on system performance.

(2) A state estimation method that serially connects a filter and a state observer is constructed. This approach addresses the insufficient ability of traditional linear observers to attenuate high-frequency measurement noise, thereby improving state estimation accuracy.

(3) Unlike References [30,31], which only guarantee the bounded stability of the system, this paper provides theoretical proof that the system achieves asymptotic stability when subjected to time-varying disturbances and uncertainties.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the mathematical model of the electro-hydraulic servo pressure control system. The observer and controller design are presented in Section 3. The results of simulation and experimental verification are provided in Section 4 and Section 5. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. System Modeling

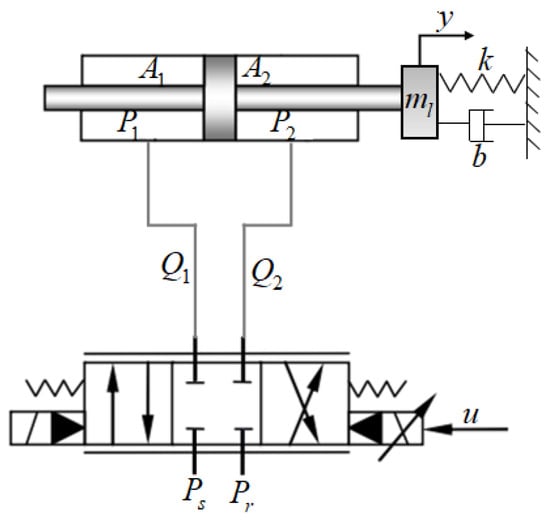

A schematic of the electro-hydraulic servo pressure control system studied in this paper is shown in Figure 1, which is a typical valve-controlled cylinder where the environment or load force acts on the end of the piston rod. The pressure difference between the two chambers of the hydraulic cylinder is indirectly controlled by adjusting the flow rate of the proportional servo valve.

Figure 1.

Schematic of electrohydraulic servo pressure control system.

According to Newton’s Second Law, the dynamics of the load is given by

where is the mass of the load, is the load’s displacement, and are the pressure of the two chambers, and represent the effective areas of the two chambers of the hydraulic cylinder, and denote the equivalent viscous damping coefficient and elastic coefficient.

The pressure dynamic of the cylinder can be written as

where and are the initial volumes of the two chambers, is the bulk modulus of the hydraulic oil, is the internal leakage coefficient, and are the supplied and return flows. For zero-overlapped valves, the relationship between flow and spool displacement is [32,33]

where and are the flow gain coefficients, is the discharge coefficient, and are the spool valve area gradients. and represent the supply pressure and the tank pressure of the hydraulic oil respectively. The function is defined as

According to the response characteristics of proportional servo valves, the spool displacement of servo valve can be related to the control input voltage by the first-order dynamic equation

where and are the time constant and voltage–displacement conversion coefficient, respectively.

Suppose that the valve is symmetrical and matched, i.e., , then Equation (3) can be rewritten as

where , and

By defining the system state variable as , the model (2)–(7) can be expressed in a state space form as

where , , , , , , is the unmodeled disturbance.

To overcome the influence of time-varying parameters, the state Equation (8) can be rewritten as

where represent the upper bound of , respectively, represents the total uncertainty of the system, which is defined as

where represents the parameter uncertainty.

Our goal is to design a controller that enables the pressure difference between the two chambers of the system to follow the given command signal as accurately as possible subject to both measurement noise, time-varying parameter uncertainty and external disturbances. Before the controller design, the following assumption and lemma are provided.

Assumption 1.

The command signal of the system is second-order continuously differentiable. The unknown time-varying parameter satisfies , the parameter uncertainty is also bounded and satisfies , where and are all known positive constants.

Remark 1.

The command signal is generally specified manually by the operator. To avoid system shocks and oscillations, it is typically configured as a continuous and smooth signal. In addition, under normal operating conditions, both and are bounded by and , respectively, and the pressure difference is much smaller than the supply pressure , which ensures that the parameter stays well away from zero. Other parameters in the system all represent the actual physical parameters of the hydraulic actuator and are bounded; thus, the parameter set can be guaranteed to be bounded. The total uncertainty consists of parameter uncertainty and disturbance uncertainty. The amplitude of the disturbance is directly related to its energy, based on the fact that the energy of the system in practical applications is always finite, combined with the boundedness of the parameters, it can be inferred that the total disturbance is also bounded.

Lemma 1.

For any positive function and , there always exists a function and a non-negative function that satisfy

Proof.

Considering and , it can be obtained that

then we can get

□

3. Control Algorithm Design

3.1. Observer Design

To suppress the measurement noise, the improved state observer is designed as

where is defined as

where is a positive constant, and the bounded function satisfies

where and are known positive constants.

Remark 2.

The advantages of the improved state observer (14) can be summarized as follows: First, this observer can be regarded as a conventional high-gain observer incorporated with a first-order filter, which can effectively attenuate the measurement noise existing in the pressure sensor signals. On the other hand, a parameter adaptation mechanism and a disturbance estimation mechanism are introduced to counteract the impacts of parameter uncertainty and total disturbance on state estimation accuracy, respectively. Thus, the performance of the observer is improved while the need for high gain is eliminated.

Combining (9) and (17), the dynamic equation of the observer’s error can be written as

where , , .

Define the system observation error vector as . Then, the dynamic Equation (17) can be rewritten as

where , , , .

By reasonably selecting the parameters and , the matrix can be made a Hurwitz matrix. Therefore, there exists a positive definite symmetric matrix that satisfies the following Lyapunov equation

where represents the identity matrix.

3.2. Controller Design

Define the following error variables:

where represents the reference command signal, and is the virtual control input.

Differentiating in (20) yields

Combined with the definition of in (20), (21) can be written as

The virtual control law can be designed as

where

Substituting (24) into (22) yields

Differentiating yields

The control input u can be designed as

Substituting (27) into (26) yields

The parameter adaptive law is designed as

where is the adjustment matrix of adaptive law.

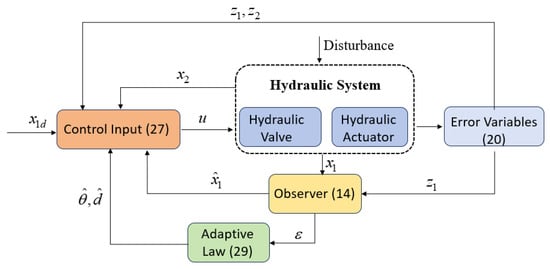

The developed controller diagram based on the above content is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Controller diagram of the proposed algorithm.

3.3. Main Result and Stability Analysis

The main result of this paper is provided below.

Theorem 1.

Based on Assumption 1, the observer (14), the control law (27) and the parameter adaptive law (29), by selecting the proper control parameters , , , , we can ensure that the tracking error of the closed-loop system achieves asymptotic convergence.

Proof of Theorem 1.

Define the Lyapunov function as

Taking its derivative with respect to time yields

According to Young’s theorem, the following inequality holds

Based on Assumption 1 and Lemma 1, one can get that

Combined with (32)–(34), we obtain

where , the form of matrix is

where .

Selecting appropriate parameters , , , , such that the matrix is positive definite, and thus it can be obtained

where is a non-negative function, is the minimum eigenvalue of matrix . Integrating both sides of (37) simultaneously yields the result

From the above equation, it can be seen that the function is bounded, and the integral of the function is bounded. Based on the definition and Assumption 1, it can be concluded that , , , , and are all bounded. Thus, it can be inferred that the system states and are both bounded. From the expression of the control input, it can be known that is also bounded. Based on the definitions of , , , , , and , it can be determined that the derivative of the function is bounded, so is uniformly continuous. Using Barbalat’s lemma [34], when time tends to infinity, tends to zero, thus completing the proof. □

Remark 3.

There exist two approaches to set the parameters of the controller. Firstly, as elucidated in Theorem 1, one can pick up a group of values for , , and to calculate all order sequential principal minor determinants of matrix to guarantee it positive definite. The exact bound of need to be carefully investigated to determine the value of . Matrix is designed to uniformly adjust the update rate of parameters, and its setting depends on the dimensions of each parameter. The positive definite matrix can be determined by solving Equation (19). This method is the most reliable and reasonable, but it often requires considerable effort and can complicate the process of algorithm implementation. Alternatively, as done in [35], a more intuitive method is to select, , and large enough to make the system initially stable without focusing on specific constraints. By doing this, at least locally around the desired trajectory to be tracked. Subsequently, these values can be incrementally adjusted until the system’s tracking performance aligns with the user’s specified requirements.

Remark 4.

To avoid parameter estimation divergence in practical applications, the following discontinuous parameter adaptive law can be used:

where and represent the maximum and minimum values of .

4. Simulation Verification

In this section, simulation verification was conducted on the control algorithm proposed in the previous section. The simulation parameters of the valve-controlled hydraulic cylinder system are shown in Table 1. By changing the elastic modulus of the oil in real time, the parameter perturbation caused by temperature changes in the system was simulated. The simulation verification was conducted based on MATLAB/Simulink (R2020b), and the solver was selected as a variable step, the simulation step size was set to 0.1 ms and the simulation time was set to 10 s.

Table 1.

Physical parameters of electro-hydraulic pressure control system.

To fully verify the effectiveness of the proposed control algorithm, three controllers are selected for comparative analysis, as detailed below:

C1: A PI controller with feedforward, which is commonly used in engineering practice. Controller parameters are tuned via the trial-and-error method until the system’s output pressure tracks the given command signal with maximum accuracy. Specifically, the feedforward gain is set to 0.02, the proportional gain to 0.5, and the integral gain to 0.2.

C2: A controller with the same basic structure as the method proposed in this paper, except that the parameter adaptive mechanism is removed. During the control law design, average values of all time-varying parameters are adopted, all other control parameters are consistent with those of Controller C3.

C3: The output feedback adaptive controller constructed in this paper. The observer gain is set to , , , , , , , .

Furthermore, to evaluate the performance of each controller, the maximum, average, and standard deviation of the absolute value of the tracking error were used, represented as Max, Mean, and Std, respectively. Three simulation cases were run to verify the effectiveness of the designed control algorithm.

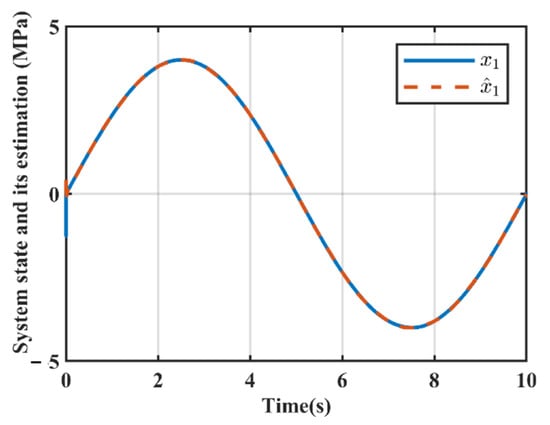

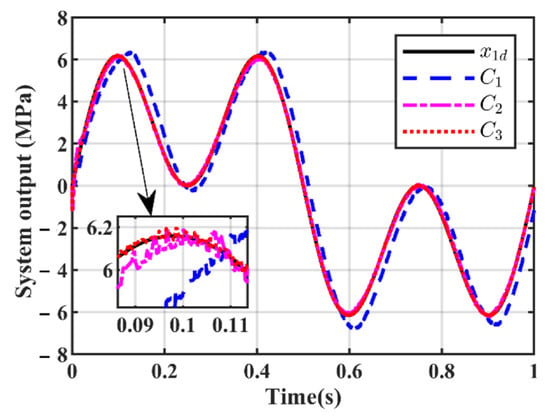

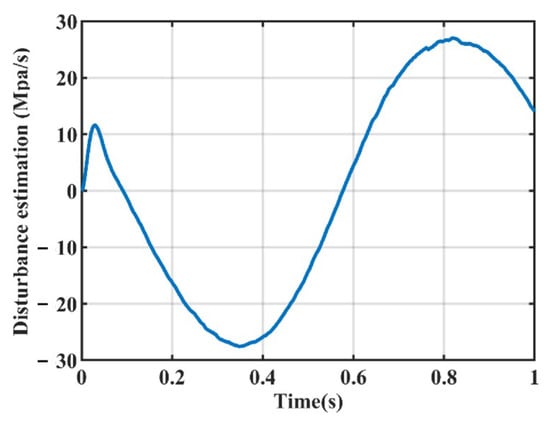

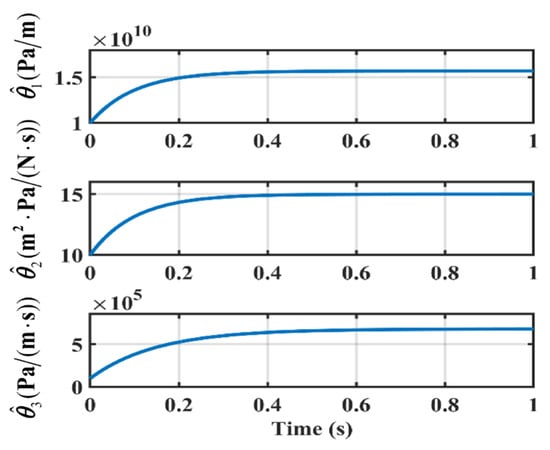

Case 1: First a low frequency command was employed to test the control accuracy of the proposed controller. The command signal is set to MPa, and the corresponding simulation results are presented in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8. Figure 3 shows the system output responses under the three controllers. The tracking errors of the three controllers are depicted in Figure 4. The specific performance indicators of the tracking errors are listed in Table 2. As observed from Figure 4 and Table 2, it can be seen that, when tracking the low-frequency command signal, the control accuracy of the traditional PI controller C1 and the model-based controller without adaptive mechanism C2 is relatively close. This is primarily attributed to the integral term in the PI controller, which eliminates steady-state errors. In contrast, the proposed output feedback adaptive controller C3 achieves higher tracking accuracy than C2 among model-based controllers—fully demonstrating the effectiveness of the parameter adaptive mechanism designed in this paper. The observer’s estimation of the system output signal is illustrated in Figure 5. At low frequencies, the constructed observer can accurately reconstruct the actual system output, verifying its reliability for state estimation. Figure 6 presents the output of the perturbation estimator. It can be seen that the perturbation estimation remains bounded throughout the simulation, which is consistent with the theoretical analysis. Figure 7 shows the variation trend of adaptive parameters. After a short transient period, all adaptive parameters converge to their steady-state values, indicating the stability of the adaptive mechanism. The control input of the proposed C3 controller is shown in Figure 8. The control input is continuous and bounded, which satisfies the practical operation requirements of engineering applications.

Figure 3.

System output in case 1.

Figure 4.

System tracking error in case 1.

Figure 5.

System state estimation in case 1.

Figure 6.

Disturbance estimation in case 1.

Figure 7.

Convergences of the parameters in case 1.

Figure 8.

Control input in case 1.

Table 2.

Performance indices in the last two cycles in Case 1.

Case2: To test the tracking ability of the designed controller for high-frequency command signals and its suppression ability for measurement noise, the composite command signal was set to MPa, and a white noise signal was added to the system output to simulate the measurement noise of the actual sensor. The corresponding simulation results are shown in Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14. Figure 9 shows the output of the system under different control actions, the tracking error of the system under different controller are shown in Figure 10, and Table 3 presents the specific performance indicators of the tracking error. By combining Figure 10 and Table 3, it can be seen that when tracking high-frequency composite command signal, the performance of controllers C2 and C3 is far superior to that of controller C1, which fully demonstrates the superiority of model-based controller design. Furthermore, by comparing Figure 4 and Figure 10, it can be concluded that as the operating frequency of the system increases, the effect of the parameter adaptive mechanism weakens accordingly. This is reasonable because the rate of parameter convergence is already lower than the rate of parameter change caused by the change in the operating state. Figure 11 shows the output results of the system observer. It can be seen that compared with the original signal, the reconstructed system state is smoother, thereby effectively reducing the interference of high-frequency noise. Figure 12 shows the result of the disturbance observer, the disturbance estimation is always bounded and varies with the change in the command signal. The estimated values of the adaptive parameters are depicted in Figure 13, and all parameters are convergent. Figure 14 shows the control input of the system under this working condition, which is also bounded.

Figure 9.

System output in case 2.

Figure 10.

System tracking error in case 2.

Figure 11.

System state estimation in case 2.

Figure 12.

Disturbance estimation in case 2.

Figure 13.

Convergences of the parameters in case 2.

Figure 14.

Control input in case 2.

Table 3.

Performance indices in the last two cycles in Case 2.

Case 3: To test the robustness to load dynamics of the designed controller, a disturbance signal is added to the system, and the command signal is selected to be consistent with that in case 2. The simulation results under this working condition are shown in Figure 15 and Figure 16. Figure 15 shows the output pressures of the three controllers, Figure 16 presents the pressure tracking errors, and Table 4 shows the performance indicators of the three controllers in the last two cycles. Comparing Figure 16 and Figure 10, one can conclude that under the influence of external disturbances, the performance of the C1 controller becomes worse, while C2 and C3 can still maintain high tracking accuracy, and the tracking error of the C3 controller is less than 2%, which fully demonstrates the strong robustness of the controller designed in this paper to external disturbances or load dynamics.

Figure 15.

System output in case 3.

Figure 16.

System tracking error in case 3.

Table 4.

Performance indices in the last two cycles in Case 3.

5. Experimental Verification

To further verify the effectiveness of the designed controller, comparative experiments were conducted on the electro-hydraulic servo motion platform shown in Figure 17. Table 5 summarizes the detailed hardware configuration of the platform, for more detailed physical parameters of the experimental platform, one can refer to reference [31]. The implementation of the control algorithm relies on the RTX real-time operating system and the operation interface developed with Lab-Windows/CVI. The controller operates at a sampling frequency of 2 kHz.

Figure 17.

Verification platform components.

Table 5.

Composition of the experimental platform.

The comparative experiments were also conducted based on the three controllers mentioned in the simulation. Compared with the simulation, the selection of controller parameters was made more conservative during the experiment due to the presence of sensor measurement noise and sampling delay. The parameter settings for each controller are as follows:

C1: Consistent with the simulation, the trial-and-error method was adopted to tune the control parameters. The feedforward gain was set to 0.08, the proportional gain to 0.5, and the integral gain to 0.15.

C2: Except for the lack of parameter adaptation mechanism, all other parameters are consistent with C3.

C3: The output feedback adaptive controller constructed in this paper. The observer gain is set to , , , , , , , .

Case 1: To verify the static tracking performance of the designed controller, a constant pressure command with an amplitude of 4 MPa was given. The system outputs under the action of three controllers are illustrated in Figure 18. Figure 19 presents the static tracking errors of different controllers, and Table 6 lists the performance indices of the three controllers. Combining the results in Figure 19 and Table 6, it can be observed that C3 achieves the highest tracking precision. In addition, due to the introduction of the state observer, the control accuracies of C2 and C3 are higher than that of C1, which fully validates the noise suppression capability of the observer proposed in this paper.

Figure 18.

System output of case 1 in the experiment.

Figure 19.

System tracking error of case 1 in the experiment.

Table 6.

Experimental performance indices in Case 1.

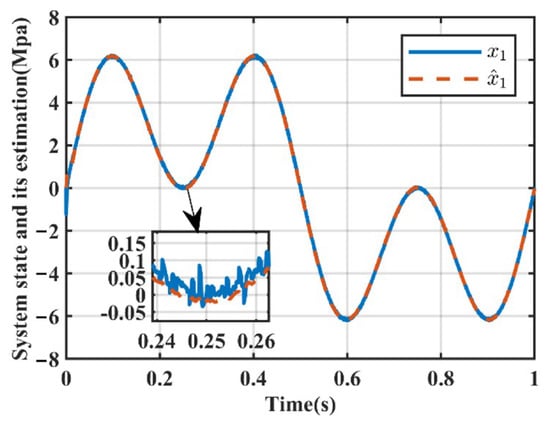

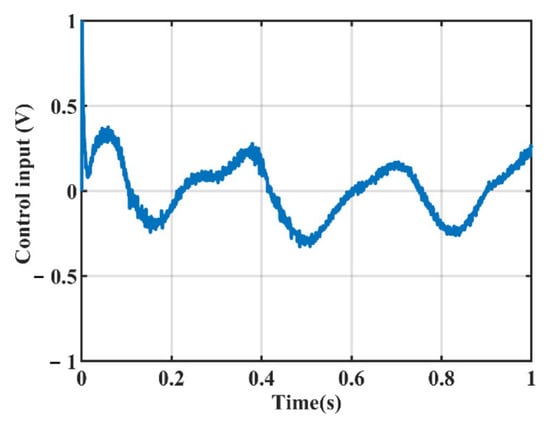

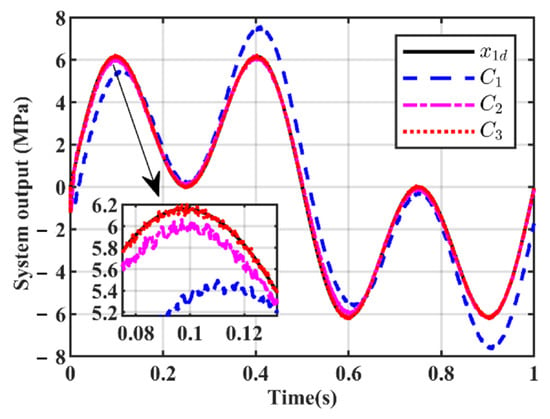

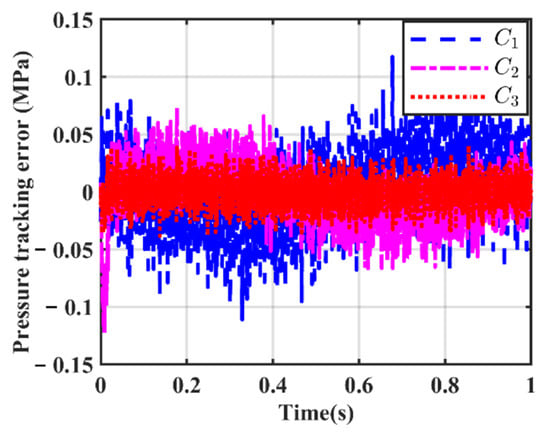

Case 2: To verify the dynamic tracking performance of the designed controllers, a sinusoidal pressure command with an amplitude of 4 MPa and a frequency of 0.1 Hz was given. The system outputs under the action of the three controllers are illustrated in Figure 20. Figure 21 presents the dynamic tracking errors of different controllers and Table 7 lists the performance indices. Combining the results in Figure 21 and Table 7, it can be observed that in this case, Controller C3 still exhibits the optimal tracking performance. Figure 22 shows the estimation of the system pressure by the state observer; as can be seen, consistent with the simulation results, the pressure estimation value is smoother compared with the original signal. Figure 23 presents the estimation result of the disturbance observer, which is bounded. The estimation results of the adaptive parameters are shown in Figure 24, all of which converge to their steady-state values within a finite time. Figure 25 depicts the control input of the system, whose amplitude falls within the effective input range of the servo valve.

Figure 20.

System output of case 2 in the experiment.

Figure 21.

System tracking error of case 2 in the experiment.

Table 7.

Experimental performance indices in Case 2.

Figure 22.

System state estimation of case 2 in the experiment.

Figure 23.

Disturbance estimation of case 2 in the experiment.

Figure 24.

Convergences of the parameters of case 2 in the experiment.

Figure 25.

Control input of case 2 in the experiment.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposed an adaptive output feedback pressure control strategy for electro-hydraulic servo systems. Through the effective integration of an Extended State Observer and a parameter adaptive mechanism, the proposed method achieved remarkable robustness against time-varying parameter uncertainties, external disturbances, and sensor measurement noise inherent in the system. Comparative simulation and experimental results verified that the designed controller outperformed traditional control methods with distinct advantages, including higher tracking precision and enhanced anti-disturbance performance. Nevertheless, this paper did not take into account the complex friction characteristics of the actuator and the dead zone of the valve. In certain special cases, friction and dead zone could induce stick-slip phenomena in the system. Therefore, based on the existing work, how to achieve accurate identification of friction and dead zone and implement targeted compensation would be the direction of our future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.H., J.L. and X.Y.; methodology, T.H., J.L. and W.W.; software, J.L.; validation, J.Y. (Jing Ye) and J.Y. (Jianyong Yao); formal analysis, T.H. and X.Y.; investigation, W.W. and T.H.; resources, J.L. and J.Y. (Jianyong Yao); data curation, T.H.; writing—original draft, T.H., J.L. and X.Y.; writing—review and editing, T.H., J.Y. (Jing Ye), J.Y. (Jianyong Yao) and X.Y.; visualization, J.Y. (Jing Ye); supervision, W.W. and J.Y. (Jianyong Yao); project administration, W.W. and J.Y. (Jing Ye); funding acquisition, J.Y. (Jing Ye) and W.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Industrial Innovation Technology Support Special Project 2024 (Changzhou Science and Technology Plan Project), grant number CF20240021. The APC was funded by Jiangsu Hengli Hydraulic Co., Ltd.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are available upon request. Please contact the corresponding author for access.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Jing Ye and Weitang Wang were employed by the company Jiangsu Hengli Hydraulic Co., Ltd. The authors declare that this study received funding from Jiangsu Hengli Hydraulic Co., Ltd. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Nomenclature

| Terms and Definitions: | |

| PID | Proportional–integral–derivative controller |

| PI | Proportional–integral controller |

| ESO | Extended state observer |

| LESOs | Linear extended state observers |

| C1 | Controller 1 |

| C2 | Controller 2 |

| C3 | Controller 3 |

| Symbols and Notations: | |

| the mass of the load (kg) | |

| the load’s velocity (m/s) | |

| the elastic coefficient (N/m) | |

| the pressure inside the left chamber of the hydraulic cylinder (MPa) | |

| the supply pressure (Mpa) | |

| the ram area of the left chamber (m2) | |

| the initial volumes of the left chamber (m3) | |

| the internal leakage coefficient (m5/(N·s)) | |

| the supplied flow rate (m3/s) | |

| the load pressure in the hydraulic actuator (MPa) | |

| the filter value of position estimation error | |

| the time constant of servo valve | |

| the system state variable | |

| the unmodeled disturbance | |

| the control input | |

| the state estimation error | |

| the initial value of parameter | |

| the estimated value of | |

| the load’s displacement (m) | |

| the load’s acceleration (m/s2) | |

| the effective oil bulk modulus (Mpa) | |

| the pressure inside the right chamber of the hydraulic cylinder (MPa) | |

| the return pressure (MPa) | |

| the ram area of the right chamber (m2) | |

| the initial volumes of the right chamber (m3) | |

| the viscous damping coefficient (N·(m/s)−1) | |

| the return flow rate (m3/s) | |

| the spool displacement of servo valve (m) | |

| the voltage–displacement conversion coefficient | |

| the controller gain | |

| the system parameter | |

| the total uncertainty | |

| the virtual control law | |

| the positive auxiliary functions | |

| the adjustment matrix of adaptive law | |

| the estimation error of | |

References

- Zhao, G.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; Guo, K. A novel reference governor for disturbance observer-based load pressure control in a dual-actuator-driven electrohydraulic actuator. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Shen, F.; Wu, K.; Lee, H.; Hwang, S. Injection molding process control of servo-hydraulic system. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ge, Y.; Zhu, W.; Deng, W.; Zhao, X.; Yao, J. Adaptive Motion Control for Electro-Hydraulic Servo Systems with Appointed-Time Performance. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2025; early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Deng, W.; Yao, J. Neural Adaptive Dynamic Surface Asymptotic Tracking Control of Hydraulic Manipulators with Guaranteed Transient Performance. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 7339–7349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, H.; Chung, W. Sliding-mode-based output feedback neural network control for electro-hydraulic actuator subject to unknown dynamics and uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2024, 54, 7884–7896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrat, G.; Ranjan, P.; Bhola, M.; Mishra, S.K.; Das, J. Position control and performance analysis of hydraulic system using two pump-controlling strategies. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part I J. Syst. Control. Eng. 2018, 233, 1093–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ge, Y.; Deng, W.; Yao, J. Observer-based motion axis control for hydraulic actuation systems. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2023, 36, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alleyne, A.; Liu, R. On the limitations of force tracking control for hydraulic servosystems. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control. 1999, 121, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, B.; Al-Majed, M.; Tomizuka, M. High-performance robust motion control of machine tools: An adaptive robust control approach and comparative experiments. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 1997, 2, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, H.; Hu, J.; Xia, K.; Yao, B. Indirect adaptive robust backstepping control for input delay systems with unknown periodic disturbances: Theory and experiments. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2025, 4, 3081–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchi, D.; Macchelli, A.; Bosi, G.; Marconi, L.; Foschi, D.; Mezzetti, M. Design of a robust adaptive controller for a hydraulic press and experimental validation. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2021, 29, 2049–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yao, B. Decoupled torque control of series elastic actuator with adaptive robust compensation of time-varying load-side dynamics. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 7, 5604–5614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, L.; Chen, Z.; Yao, B. Advanced valves and pump coordinated hydraulic control design to simultaneously achieve high accuracy and high efficiency. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2021, 29, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helian, B.; Chen, Z.; Yao, B.; Lyu, L.; Li, C. Accurate motion control of a direct-drive hydraulic system with an adaptive nonlinear pump flow compensation. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2021, 26, 2593–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Lu, B.; Yu, B.; Ye, Z. Cascaded sliding mode force control for a single-rod electrohydraulic actuator. Neurocomputing 2015, 156, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Zhu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, W.; Tang, Y.; Li, X. Real-time tracking control of electro-hydraulic force servo systems using offline feedback control and adaptive control. ISA Trans. 2017, 67, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Cheng, Y.; Huang, S.; Wu, M.; Huang, H.; Li, Y.H. Pressure control of electro-hydraulic servo loading system in heavy vehicle steering test board based on integral sliding mode control. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2020, 234, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Shen, G.; Rui, G.; Cheng, D.; Li, X.; Sa, Y. Real-time nonlinear adaptive force tracking control strategy for electrohydraulic systems with suppression of external vibration disturbance. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2019, 41, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakova, S.; Sawodny, O.; Bohm, M. Force tracking control for hydraulically actuated adaptive high-rise buildings. Control Eng. Pract. 2024, 146, 105899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flayyih, M.; Hamzah, M.; Hassan, J. Nonstandard backstepping based integral sliding mode control of hydraulically actuated active suspension system. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2023, 24, 1665–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Shen, G.; Yang, C.; Zhu, W.; Yao, J. A robust force feed-forward observer for an electro-hydraulic control loading system in flight simulators. ISA Trans. 2019, 89, 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, C.; Xu, H.; Jiang, J. Practical torque tracking control of electro-hydraulic load simulator using singular perturbation theory. ISA Trans. 2020, 102, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ping, Z.; Fu, Y.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, P. Observer-based backstepping adaptive force control of electro-mechanical actuator with improved LuGre friction model. Aerospace 2022, 9, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Won, D.; Shin, D.; Chung, C. Output feedback nonlinear control for electro-hydraulic systems. Mechatronics 2012, 22, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Celler, B.; Su, S. Backstepping control of electro-hydraulic system based on extended-state-observer with plant dynamics largely unknown. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 63, 6909–6920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, V.; Phan, Q.; Ahn, K. Observer-based adaptive fuzzy tracking control for a valve-controlled electro-hydraulic system in presence of input dead zone and internal leakage fault. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Li, S.; Kong, X.; Ma, H.; Yu, Z.; Ai, C.; Jiang, Y. Output feedback control of dual-valve electro-hydraulic valve based on cascade structure extended state observer systems with disturbance compensation. Machines 2025, 13, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Shen, G.; Li, X.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Q. An improved nonlinear extended disturbance observer for sliding mode control in electro-hydraulic servo system. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2024, 30, 2155–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, J.T.; Wrat, G.; Mishra, S.K.; Ranjan, P.; Das, J. Fuzzy PD-Based Control for excavator boom stabilization using work port pressure feedback. Actuators 2025, 14, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Yao, J.; Hu, J.; Feng, G. Output feedback active disturbance rejection control of an electro-hydraulic servo system based on command filter. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 38, 103169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ge, Y.; Deng, W.; Yao, J. Precision Motion Control for Electro-Hydraulic Axis Systems under Unknown Time-Variant Parameters and Disturbances. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2024, 37, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Deng, W. Active disturbance rejection adaptive control of hydraulic servo systems. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2017, 64, 8023–8032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, H. Hydraulic Control Systems; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Krstic, M.; Kanellakopoulos, I.; Kokotovic, P. Nonlinear and Adaptive Control Design; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, B.; Bu, F.; Reedy, J.; Chiu, G. Adaptive robust motion control of single-rod hydraulic actuators: Theory and experiments. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2000, 5, 79–91. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.