Abstract

This study presents the state-feedback and output-feedback adaptive shared trajectory tracking control laws for nonlinear Euler–Lagrange systems subject to parametric uncertainties and output constraints framed within linear inequalities. The logarithm-driven coordinate transformation is used to ensure that system outputs are consistently bounded by defined regions, while model-based adaptive laws are used in the machine controller to estimate and cancel parametric uncertainties and the human controller can be given arbitrarily. The stability of the whole controlled system is proved by Lyapunov stability theory, and simulation examples are used to illustrate the performance of the proposed shared control laws.

1. Introduction

Industrial manipulators and many man-made systems exhibit major safety risks due to human tiredness, inattention, and judgment mistakes. Thus, scientists endeavor to synthesize automatic controllers that undertake part of the control task, ensuring the security of the controlled system. In essence, the operation authority in the system is bidirectional switching between a automatic controller and a human operator. A shared control framework involves feedback control inputs and human operator inputs simultaneously in the controlled system [1,2]. Over the past decades, it has attracted significant attention and interest from a wide range of control system societies in both academia and industry, as it combines the reliable, precise, and fast capabilities of automatic controllers with interactive, adaptive, and creative task execution performance of human controllers [3]. Under normal circumstances, the system is handled by human operators, while in dangerous situations, the operation authority is obtained by the automatic controller. For a human–machine coordination control system in dynamic scenarios, the human is accountable for developing a policy, while the automatic controller will evaluate the security of the policy. If it is not safe, the automatic controller should adjust the strategy and apply the updated one. Moreover, human beings are able to perform their operations, feeling that the system is reacting to their behavior, and they receive feedback from the shared controller, which signifies the level of risk associated with their behavior. This is why human–machine control holds considerable significance and is widely employed in both military and civilian facilities. Common applications of human–machine control can be found in robots [4,5,6], automotive vehicles [7,8,9], and human–robot systems [10,11].

To improve the safety and robustness of the controlled system, adaptive shared controllers are developed for Euler–Lagrange systems in this study. New contributions are as follows: firstly, unlike the traditional machine automatic control law design with the known parameters of the system model, certainty equivalent and non-certainty equivalent principles are employed to develop two kinds of state-feedback controllers for human–machine systems to deal with model uncertainties. Secondly, compared with the requirements of full-state measurements in traditional state-feedback control techniques, a different adaptive output-feedback law is designed in the shared control framework based on the inherent passivity of the human operator. In particular, a velocity observer is designed for the output-feedback law to guarantee automatic control performance. Thirdly, different from the authority sharing methods in many human–machine system studies, a hysteresis sharing a function-based smooth transitional mechanism between the automatic control inputs and the human inputs is designed to allocate the operation authority of the shared control system, while the joystick handle-based passive human input is also given to obtain the human intention weighted shared controller. Actually, the proposed human–machine control system in this study could accept any human input freely. Specifically, rigorous proofs of all theoretical results are presented carefully, and simulation examples are given to show the safety and robustness of the proposed algorithm for the system under output constraints.

2. Problem Statement

The category of human–machine systems under consideration is presumed to be represented by the Euler–Lagrange equations [12].

where represent configuration and its derivatives, respectively; represents the inertia matrix; represents the centripetal Coriolis matrix; is the gravity term; and denotes the external control input, which is a blend of the inputs provided by the human and by the automatic controller .

Assumption 1.

An admissible set is characterized by a group of linear matrix inequalities as

where , with and for . When , T and K meet the condition under for , , .

Definition 1.

The jth constraint is considered to be a motivation for the first-order derivative if with .

Definition 2.

There are three subspaces in the whole state space, such as the safe set , the hazardous set , and the hysteresis set , determined by the position and speed towards the borderline. With respect to the ith set of activation constraints

with and invertible matrix , mathematical descriptions of the safe, hazardous, and hysteresis sets are provided by [1]

with and .

Remark 1.

It is noted that the subsets , , and are related to the original system states , but the subsets , , and are related to the constrained system states .

Definition 3.

The s-closed-loop system is defined by (1), and the h-closed-loop system is defined by . Additionally, define and to represent

limit sets for two kinds of closed-loop systems.

Assumption 2.

System states and are available for state-feedback design, while the state is unavailable for output-feedback design. It is assumed that the desired trajectory and its derivatives and exist and are bounded.

The goal of designing the human–machine shared controller in this study is to find an automatic controller, a safe subset, and an operation authority sharing mechanism under a specified human input such that

- The states of the system (1) remain within a specified and compact admissible set under a safe subset , where is a forward invariant set;

- does not modify the objective of the human operator. Specifically if , and if , where represents a projection of into to be designed;

- if the system state remains within the safe subset .

3. Machine Controller Design and Analysis

3.1. Machine Certainty-Equivalent Adaptive Control

Generally, the number of constraints on system outputs mainly depends on the control mission and the environment conditions. When , only n constraints are activated according to (2), while when , augment constraints with a sufficient large constant can be added by the designer to the system until . Without loss of generality, we devise the automatic controller for the scenario with . The Euler–Lagrange system (1) with the coordinate is characterized by (3), and the corresponding automatic controller can be reformulated as

where . A new variable is defined by

to remove the constraint on , where is the reference signal for with defined by

and , , . It is noted that is the projected feasible reference that satisfies all constraints, i.e., . Reference signal (7) is one possible smooth solution. In addition, according to (7), we also find that when m is sufficiently small, indicating that the reference signal tracks the human operator’s intentions as long as the human behavior is sufficiently safe (i.e., is far away from obstacles).

Since the smooth function for all , then and exist and , , . Furthermore, note that .

Suppose denotes a point in at space, so the projection of into the safe subset with regard to the ith set of motivation constraints, denoted by , is characterized by . Thus, the projection of into the subset with regard to the ith group of active constraints is characterized as

The velocity error is defined by under the ith set of motivation constraints. Next, by differentiating and , the tracking dynamics of the constrained Euler–Lagrange system is obtained by

where ,

In the backstepping control design framework, the virtual input of the first subsystem in (9) is formulated as , where . Then the virtual input derivative is . Furthermore, define , and the tracking dynamics (9) is reformulated by

where .

Define with a tunable constant ; then, the model (10) can be reformulated as

where , with the parametric vector formulated from the terms , , , and and with the corresponding regression matrix of . Actually, this is the result of the linear parameterization property of model (1). Different sequences of parameters in the parameter vector result in different regression matrices. Thus, the explicit form of the known regressor vs. the unknown parameter in (11) cannot be directly given based on the general model (1), unless the model (1) of the mechanical system is explicit.

Design the certainty-equivalent adaptive state feedback controller as

where K is a positive-definite matrix; is the estimation of ; and is a tunable constant.

Theorem 1.

Proof.

Choose a candidate Lyapunov function for the system (11) by with parametric estimation error . Then, the derivative of along the trajectory of (11) with controller (12) satisfies . Since and K are negative definite and positive definite matrices, then , which indicates that both and are bounded. In addition, the second derivative with respect to is given as . According to the definition of and (10), it can be concluded that both and exist and are bounded; therefore, exists and is bounded. From Barbalat’s Lemma [13], it is immediately concluded that and as . Furthermore, it can be concluded that and as . □

Remark 2.

The concept of certainty equivalence in traditional adaptive control is an important feature. This implies that initially, a controller is constructed under the assumption that all the system parameters are known. Controller parameters are defined by a function of all model parameters. Given the actual values of the model parameters, the controller parameters of the controller are computed by solving design equations aimed at pole-zero placement, model matching, or optimality. When actual model parameters are unavailable, controller parameters can be either estimated directly or computed indirectly by solving the identical design equations utilizing estimations of the model parameters. The obtained controller, which is estimated or designed specifically for the estimated model, is termed a certainty equivalence adaptive controller. However, since certainty-equivalent adaptive law is generally just an integrator about system states, the parameter estimator performance depends on the state tracking performance.

3.2. Machine Non-Certainty-Equivalent Adaptive Control

Based on (11), one can design non-certainty-equivalent adaptive control law as

with , the stable first-order linear filters

and the regression matrix defined by , where , , and .

Theorem 2.

Proof.

Adding and subtracting into the right-hand side of dynamics in (11) results in

Denote a linear filter for the control signal as

Thus, the solution of system (18) can be immediately derived by , where . It can be seen that is an exponentially decaying term and its initial value directly depends on , , , , and . Thus for all is equivalent to following conditions about tunable parameters: , , and . Furthermore, based on (14), this means that initial values of filters should satisfy (15).

Thus, leads to the filtered-state error dynamics as

Define the parameter estimation error and the filtered control signal ; then, the filtered-state error dynamics (19) can be rewritten as

and the derivation of the dynamics of the estimation error is obtained by

Set a candidate Lyapunov function for (11) by . Then, recalling and taking the time derivative of along the trajectory of (20) and (21) yields

Remark 3.

Founded on the non-certainty-equivalent principle, the adaptive law of plant parameters could be designed as a stable filter, and the estimator performance could also be improved with the tunable parameter in the filter. Moreover, the estimate parameters of the non-certainty-equivalent adaptive system encompasses not only the estimates from the adaptive dynamic subsystem but also nonlinear functions. The inclusion of additional nonlinear functions within the estimated parameter vector enhances the performance of the controller. A typical non-certainty-equivalent adaptive design technique is the immersion and invariance manifold method. This method aims to keep the manifold’s invariable and attractive properties such that the overall system is stable. This idea is also applied to the adaptive estimator. If the error between the estimation of the plant parameter and its true value is chosen as the invariable manifold and the suitable nonlinear function in the adaptive law is designed, then the estimation error could be always bounded by small constants even asymptotically converging to zero. Thus, the non-certainty-equivalent adaptive controller generally has better parameter estimation capability than the traditional certainty-equivalent adaptive controller. Moreover, since the considered nonlinear mechanical system has the double-integrator structure and the model linear parametrization property, the certainty-equivalent and non-certainty-equivalent principles could be easily employed in the feedback control subsystem designed in this study.

3.3. Machine Adaptive Output-Feedback Control

The error Equation (9) can be reformulated as

where , . Clearly, since can be written as based on the linear parametrization, then the model (23) can be parameterized as

Furthermore, it can be seen that and are the first-order continuously differentiable functions.

The adaptive output feedback control law for (23) is proposed as

where and are filtered signals; is the estimation of ; is an auxiliary variable used in the filter; is a constant, diagonal, positive-definite matrix; is a positive constant; and for any with being the standard signum function.

To facilitate the stability analysis of the controlled system, define a signal as

Taking the time derivative of in (30) yields

After multiplying (32) by and substituting (25) into (24), the closed-loop system is

where and the parameter estimation error is .

Remark 4.

Lemma 1.

Define a function . If the control gain matrix is selected to satisfy the sufficient condition , where is the jth entry of the diagonal matrix , then it can be derived that with the positive constant .

Theorem 3.

Proof.

Define a function from Lemma 1. Choose a function as

Note that (34) can be bounded by

where , and . The time derivative of along the system trajectory of (33) is given by

where , , and . This means that

for or , where is a positive constant. Then, following Theorem 8.4 in [13], one can define the region as . From (35) and (37), we know that , , , , and are bounded. From (30), we further know that is also bounded. Then, from (26)–(28), we know that , , and are bounded. Furthermore, since is a first-order continuously differentiable function, then it is also a bounded function. Then, from (25) and (23), we know that the feedback control inputs and are bounded. Based on the above boundedness statements, it can be deduced that is also bounded, which is a sufficient condition for being uniformly continuous. If we define the region , then we can recall Theorem 8.4 in [13] to state that as for any . Then, from the definition of in Remark 1, we know , , , and as for any . Furthermore, it can be concluded from (30) that as for any . Therefore, all closed-loop system signals are bounded, and and as for any . It can be further noticed that larger results in a larger attraction region to include any initial conditions of systems so that a semi-global type of stability result is derived. Then, based on and , we can derive that the attraction region is such that . □

In spite of the availability of the proposed adaptive output-feedback controller (25), the velocity of system (23) is still unknown, so the safety of system (1) cannot be known in real time. Fortunately, based on the separation principle of observation and control, the velocity observer for (23) could be designed under the adaptive output-feedback controller (25). In fact, once the velocity observation is derived by the velocity observer, the observation for actual velocity in (5) can be directly computed from (6) and the first sub-equation in (9) as

where and . Thus, the objective of velocity observer design is to ensure the observation error as only using measurement .

To facilitate designing the velocity observer for (23) subject to parametric uncertainty, it is assumed that the matrix can be written as with known part and unknown part . Then the system model (23) is rewritten as

where and .

Assumption 3.

The parametric uncertainty is bounded, and is a first-order continuously differentiable bounded function in (39).

Based on the above assumption, the following velocity observer is designated by

where is an auxiliary variable and are constant, diagonal, and positive definite matrices. Furthermore, the observer (40) can be reformulated as

Then, based on the system model (39), the observation error system is

Define a signal and set with identity matrix . Then, from (42), one has

where . Note that and are bounded functions due to Assumption 3.

It is easily proven that the proposed velocity observer (40) for system (23) can guarantee that and as if the gain matrix satisfies , where and are the jth entry of and , respectively.

Theorem 4.

Proof.

It has been clearly proven in Theorems 1 and 2 that and as under the condition that the feedback controller has no switching from to under . Now consider the case of switching from to under . If in (1) switches without delay from to at ; then, and at . If in (1) switches not directly from to , such as if departs from at and falls into at , then owing to the existence of , there is ensuring that for . Define and note that ; then, we have and . Let represent a succession of motivation constraint groups of which for , and the jth constraint group is motivated in the time under with . Thus, . Set the multiple Lyapunov function for whole system if , then and as for . Furthermore, founded on the signal , it can be derived that ; thus, for . □

3.4. Human Control Inputs

In order to provide human inputs by joystick handles, the position of handles should be away from its zero position, and the human can give the mechanical systems different speed and direction commands based on the human’s intent. When this occurs, a control force feedback is created according to the human’s hand, where the force from the handles scales linearly with the displacement away from the tracked position along each degree of freedom of the mechanical systems, and the control force can be expressed as

where is a spring constant and represents the deviation from the tracked position along each degree of freedom. Note that only the stiffness parameter is applied to calculate the joystick feedback forces, ensuring that the human undergoes the identical stiffness response in both directions.

Assumption 4.

In general, the human–machine interactive system based on the joystick handles is passive, that is , where denotes the input force exerted by a human, denotes an external force exerted by the environment, is the speed of the handle of a joystick, and is the speed of the controlled mechanical systems. As the mechanical system is not manipulating its environment, then it is observed that no external forces are applied to the system except to the disturbances so that and the human control input is passive.

Measures of the human’s intent to control the position of the mechanical system can be defined by using the above assumption. Denote the rates of the joystick handles displaced from the tracked position as . Then, the intent of human’s operation is measured as

Note that whenever the joystick handle is moved away from the tracked position in any direction, and only when so that the human’s intent to control the system is measured conveniently.

5. Simulation Validations

Consider that the omnidirectional mobile robot [17] is characterized by (1), whereas the signals and parameters within the system are represented by , .

, , , and , where denotes the robot’s mass center position and the yaw angle; and are the mass and inertia parameters; r and denote the wheel’s radius and inertia; and denotes the distance the from mass center to any one of the wheels. All robot parameters are set to (kg), (kgm2), (kgm2), (m), (m), and , respectively. In the simulation example, the initial values of the robot’s mass center position and the yaw angle are set to , and the initial values of its derivatives are set to . There is an unknown parametric vector because of unknown parameters , , and for the robot, and its initial value is set to . Then, the human–machine shared controller is given by under (46) or (47), and the human control inputs are imitated by a simple proportional controller (44).

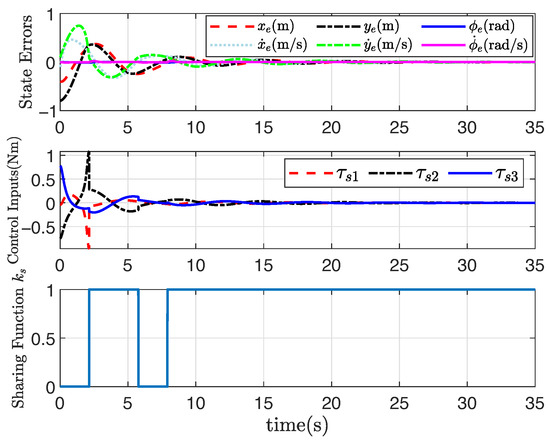

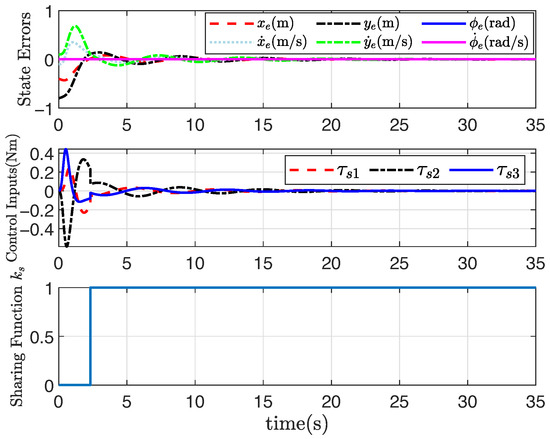

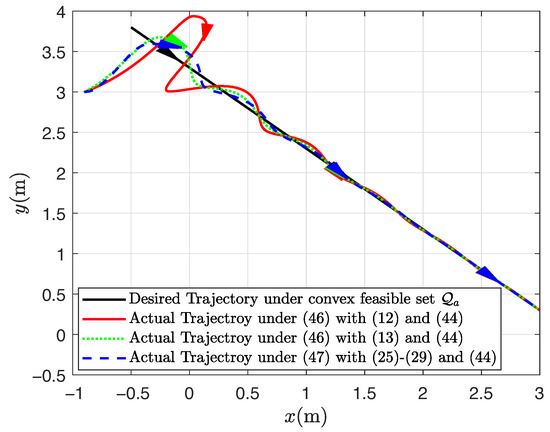

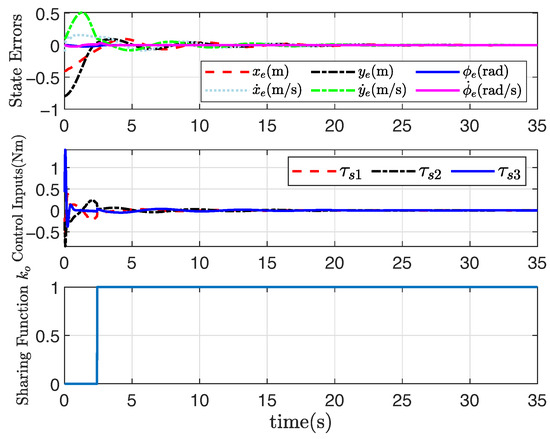

Assume the convex feasible set is given by

Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the trajectory tracking results based on the proposed human–machine shared controllers (46) with (12) and (13) and shared controllers (47) with (25)–(29), respectively. Figure 1 clearly demonstrates the effect of trajectory tracking under output constraints, where the arrows indicate the trajectory direction. With the implementation of the shared controllers we proposed, the robot does not violate the output constraints and is able to accurately follow the desired trajectory. Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively, illustrate the system responses based on three shared controllers, allowing for a more detailed observation of the system changes at each moment as they vary over time. Furthermore, it can be observed that the control input of the system is relatively small. If the initial position is far from the desired trajectory, the control input will increase in order to enable the robot to rapidly track the required trajectory. When appropriate control parameters are selected, the robot can still perform trajectory tracking stably. The stability of the system will not be affected by variations in the initial position and control input. These results illustrate that the convex feasible set of the robot motion trajectory can be guaranteed, and the safety is guaranteed by combining human-controlled input and machine-controlled input, where the feedback controller has full control authority if the state belongs to the hazardous set and the human operator is in full charge if the state belongs to the safe set. Furthermore, the proposed adaptive output-feedback controller (47) is employed to complete the straight-line path-tracking task under the convex feasible set, and simulation results are shown in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. Clearly, the adaptive output-feedback shared controller can also ensure satisfactory performance of the human–robot system in the convex feasible set in the motion space.

Figure 1.

Trajectory tracking results under convex .

Figure 4.

System response based on (47) under convex .

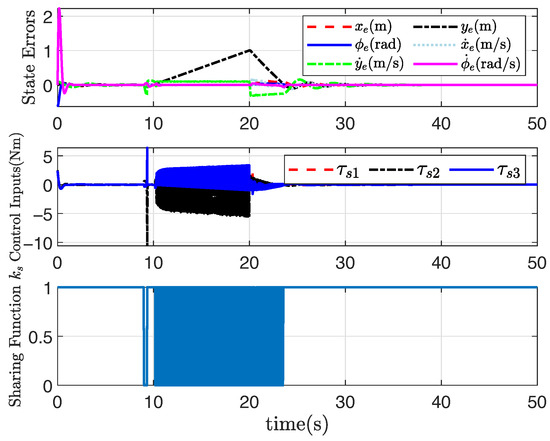

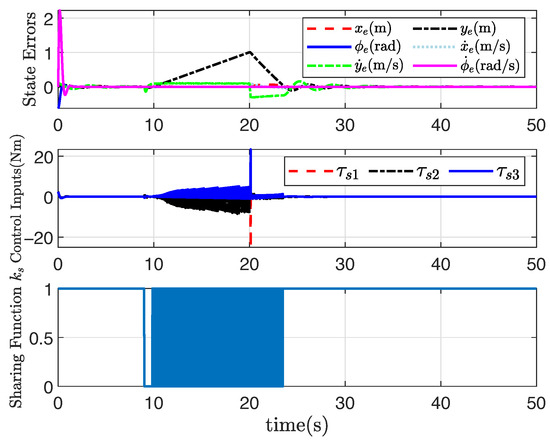

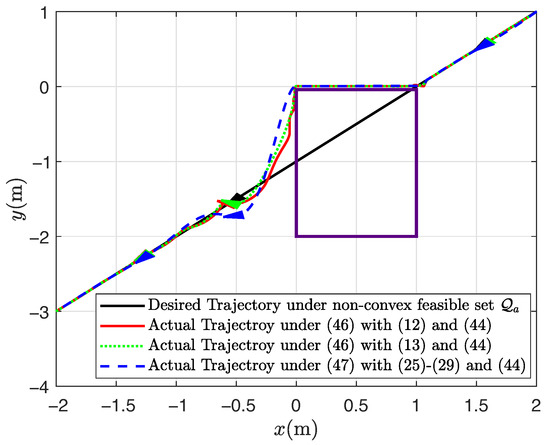

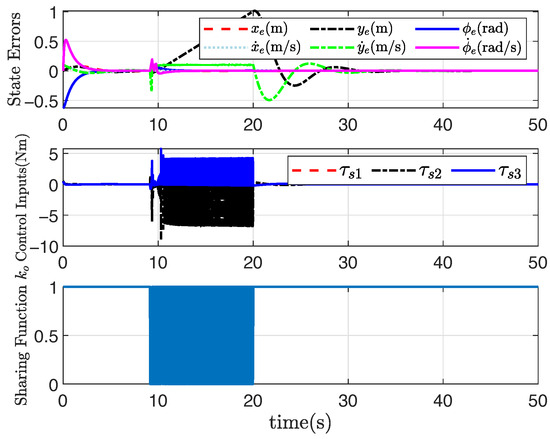

Assume the non-convex feasible set is given by

Under the non-convex feasible set in the robot motion space, the desired straight-line path can be still tracked well through the application of the presented adaptive shared controller, and the tracking performance is also satisfactory, as shown in Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8, where the rectangular obstacle is well avoided. The adaptive state-feedback shared controllers (46) with (12) and (13) can drive the robot to avoid the collision area, even though the robot is approaching the border of the feasible set. Similarly, from Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8, the performance of the robot working in the non-convex feasible set is guaranteed by using the presented adaptive output-feedback controller (47). All results imply that the presented shared control approaches are effective even though the feasible set is non-convex.

Figure 5.

Trajectory tracking results under non-convex .

Figure 8.

System response based on (47) under non-convex .

6. Conclusions

This study developed human–machine shared controllers for uncertain output-constrained Euler–Lagrange systems subject to parametric uncertainties, where certainty-equivalent and non-certainty-equivalent principles are employed to develop two types of adaptive state-feedback shared controllers, and an output-feedback shared controller is also designed. The hysteresis sharing function is also designed to synthesize the human controller and the machine controller together, and the trajectory tracking performance of shared control systems is also analyzed in a Lyapunov framework. Simulation results illustrate that the presented human–machine shared controller is efficacious for Euler–Lagrange systems under non-convex feasible areas. Safety is guaranteed by the presented shared controller, since the desired trajectory is tracked precisely and collision areas are also avoided. The robustness of the system is mainly seen from the good tracking performance of the system under model parametric uncertainties. In addition, due to the current limitations under experimental conditions, we have not yet conducted experimental validation. Thus in future studies, we plan to apply the proposed method to our omnidirectional mobile robot platform to evaluate its feasibility and robustness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.S.; Methodology, L.S.; Software, K.T.; Validation, K.T.; Formal analysis, K.T. and L.S.; Investigation, K.T.; Data curation, K.T.; Writing—original draft, K.T.; Writing—review & editing, L.S.; Visualization, K.T.; Supervision, L.S.; Project administration, L.S.; Funding acquisition, L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 62373038) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (no. FRF-IDRY-GD22-002).

Data Availability Statement

Data not available due to ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Jiang, J.; Astolfi, A. State and output-feedback shared control for a class of linear constrained systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2015, 61, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Jiang, J. Adaptive state-feedback shared control for constrained uncertain mechanical systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2022, 67, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habboush, A.; Yildiz, Y. An adaptive human pilot model for adaptively controlled systems. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 2022, 6, 1964–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tika, A.; Bajcinca, N. Predictive control of cooperative robots sharing common workspace. IEEE Control Syst. Technol. 2024, 32, 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becanovic, F.; Bonnet, V.; Dumas, R.; Jovanovic, K.; Mohammed, S. Force sharing problem during gait using inverse optimal control. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 872–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wang, Z.; Ding, L.; Li, Z.; Shi, J.; Gao, H.; Liu, G.; Huang, Y. A closed-loop shared control framework for legged robots. IEEE-ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2024, 29, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y. Shared steering control for human-machine co-driving system with multiple factors. Appl. Math. Modell. 2021, 100, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Yin, G.; Zhang, H. Human-machine shared control for path following considering driver fatigue characteristics. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 7250–7264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Yin, G.; Liang, J.; Lu, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhou, C.; Peng, P.; Cai, G. A robust cooperative game theory-based human-machine shared steering control framework. IEEE Trans. Transp. Elect. 2024, 10, 6825–6840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Zhao, S.; Cao, H.; Yi, B.; Song, X. Koopman operator-based driver-vehicle dynamic model for shared control systems. Appl. Math. Modell. 2023, 114, 423–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J. A corrective shared control architecture for human–robot collaborative polishing tasks. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2025, 92, 102876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, R.; Perez, J.A.L.; Nicklasson, P.J.; Sira-Ramirez, H. Passivity-Based Control of Euler-Lagrange Systems: Mechanical, Electrical and Electromechanical Applications; Springer: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, H. Nonlinear Systems; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, D.; Akella, M.R. Non-certainty equivalent adaptive control for robot manipulator systems. Syst. Control Lett. 2009, 58, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astolfi, A.; Karagiannis, D.; Ortega, R. Nonlinear and Adaptive Control Design with Applications; Springer: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Prieur, C.; Teel, A. Uniting local and global output feedback controller. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2010, 56, 1636–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sira-Ramirez, H.; Lopez-Uribe, C.; Velasco-Villa, M. Linear observer-based active disturbance rejection control of the omnidirectional mobile robot. Asian J. Control 2013, 15, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).