Abstract

This paper addresses the observer-based controller design for adaptive cruise control (ACC) systems using a linear matrix inequality (LMI) framework, considering both input saturation and disturbance attenuation performance. To formulate the controller design problem as LMIs, the nonlinear input saturation is represented as a convex combination of linear state feedback controllers. Unlike conventional approaches that only reformulate input saturation, this work further incorporates the estimated state and the decay rate of a Lyapunov function to establish an invariant level set condition, leading to a novel LMI-based design criterion. The proposed method incorporates level set conditions to handle input constraints and employs an criterion to ensure disturbance attenuation. Since the resulting design conditions are non-convex due to bilinear matrix terms, a two-step approach is applied to derive the controller design conditions in the form of LMIs. Finally, simulation results are presented to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method.

1. Introduction

Extensive research on autonomous driving technologies has accelerated the commercialization of advanced driver assistance systems (ADASs) aimed at enhancing vehicle safety and driving convenience [1,2,3]. An ADAS includes technologies ranging from passive features like emergency braking and driver monitoring to active functions such as adaptive cruise control (ACC) and lane keeping. Among them, ACC is considered a key component toward full self-driving and has been widely studied over the past decades [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Early ACC systems relied on full-state feedback using direct measurements of distance, relative velocity, and acceleration [4,7]. However, the high cost and noise sensitivity of required sensors remain major barriers to practical deployment.

Accordingly, observer-based control structures have become essential in ACC systems, where only a subset of measurable state variables is available for feedback control [8]. It is well known that the observer and controller can be designed simultaneously owing to the separation principle. Therefore, numerous studies have proposed LMI-based observer-controller design methods derived from Lyapunov stability criteria [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Along this line, ref. [10] proposed two independent event-triggered control strategies for the sensor-to-observer and controller-to-actuator channels, respectively, to address the input-to-state stabilization problem to external disturbances. Very recently, continuous-time observer designs have been extended to sampled-data systems composed of digital sensors. For example, ref. [13] proposed a sampled-data observer design for systems with nonlinear output functions, which was further extended in [14] to guarantee the same state estimation performance as previously designed continuous-time observer.

While observer-based control has been widely studied, few works address both input constraints and disturbance attenuation [9,17,18], which are critical for real-world applications. Incorporating actuator limits often leads to bilinear matrix inequality (BMI) conditions, making controller synthesis challenging. Although a two-step iterative linear matrix (ILMI)-based method was proposed in [19] to handle input constraints, the joint treatment of input saturation and disturbance attenuation remains unexplored.

As previously mentioned, it is widely recognized that actuator limitations must be explicitly considered during controller design [20,21,22,23]. To ensure reliable control performance in real vehicles, actuator limitations such as maximum output must be explicitly considered. Generally, two main approaches have been proposed to address such limitations: one directly restricts the norm of the control input [19,24], while the other allows the saturation on the input [21,23,25,26,27,28]. The norm-constrained approach has advantages in terms of design simplicity, but it tends to result in conservative conditions. In contrast, explicitly accounting for input saturation reflects the physical actuator limits more accurately and thus, results in less conservative controller designs. Owing to these benefits, input saturation-based control design has attracted significant attention in recent years [25]. Among various approaches, the authors in [26,27,28] represented the actuator saturation as a convex combination of state feedback controllers, which enables linear matrix inequality (LMI)-based controller design. However, when input saturation is incorporated into an observer-based control structure, the design conditions are typically formulated as BMIs, which cannot be efficiently solved using standard LMI solvers.

In addition to input constraints, maintaining passenger comfort under external disturbances is important. Especially, in the ACC system, acceleration or deceleration of the lead vehicle act as external disturbance. To address disturbance attenuation, control theory is commonly employed, and extensive research has been conducted on LMI-based controller design [29,30,31]. However, most existing works did not explicitly account for input saturation in the performance objectives. As a result, few studies simultaneously consider both the disturbance attenuation requirement and actuator saturation constraints, which are essential in practical vehicle control.

Inspired by the analysis above, this paper presents an LMI approach to the design of an observer-based controller for ACC systems under input saturation and external disturbances. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- LMI-based observer-based controller design conditions are proposed for ACC systems under input saturation.

- A level set condition is derived to ensure input constraint in the presence of external disturbances and state estimation errors.

- To incorporate input saturation into the LMI formulation, the saturated control input is represented as a convex combination of multiple linear state-feedback controllers outputs.

Notations: For a matrix M, . For a vector x, denotes the standard Euclidean norm. with an integer x denotes the integer set . denotes a column vector, i.e., . denotes a block diagonal matrix.

2. Problem Formulation

2.1. ACC System Configuration

In this subsection, the structure of the ACC system, composed of a leader and an ego vehicle, is described. It is well known that the longitudinal dynamics of each vehicle is represented by the following linear model [32]:

where , , and are the position , velocity , and acceleration of the ith vehicle, respectively; denotes the time constant that characterizes the acceleration response of the ith vehicle; is the control input , which is the desired acceleration of the ego vehicle that is physically realized through engine or brake forces by a well-designed external controller. Finally, and correspond to the leader and ego vehicles, respectively.

Based on the constant time headway (CTH) policy [33], which accounts for both headway time and standstill distance, the desired inter-vehicle distance, , and the actual distance between the two vehicles, , are defined as follows:

where is the desired inter-vehicle distance ; is the standstill distance ; and is the headway time .

Now, we define the distance tracking error and the velocity tracking error as follows:

Substituting the vehicle dynamics (1) into the definitions in (2) and (3), we obtain the following dynamics of the ACC system:

Before proceeding to next, we introduce the following notations used throughout this paper: , , , and denote the dimensions of the state, input, output, and acceleration vectors, respectively; and the state vector is defined as .

Then, by summarizing the above, we can derive the following linear state-space model:

where is the system output; is the control input to the ego vehicle; denotes the saturated control input vector, in which each element is computed by ; denotes the saturation level; is the acceleration of the leader vehicle; and the system matrices are defined as

Remark 1.

In this study, the distance tracking error is selected as the system output, since it can be readily obtained using either a radar sensor or an RGB camera. Although the relative velocity is also measurable, we assume that the ACC system considered in this paper relies solely on an RGB camera, which makes it difficult to accurately measure it.

With the system model established above, we now consider an observer dynamics which is given by

where denotes the estimated state vector; is the estimated output; and is the observer gain matrix to be designed.

Finally, the control input is determined by the following state feedback law:

where is the gain matrix to be designed.

2.2. Preliminaries

First, we define the following level sets:

The saturation function introduced in the previous subsection is a nonlinear mapping, which complicates the derivation of stability conditions in the form of LMIs. To address this issue, a convex summation representation of the saturation function has been developed in [27,28]. While previous works have focused on full-state feedback controllers, this paper extends the framework by incorporating the estimated state vector into the feedback loop.

The following lemma provides a convex summation representation of .

Lemma 1

([34]). For a given matrix if , then there exist a matrix with and scalar variables such that the following equation holds:

where , ; is a diagonal matrix whose diagonal elements are either 0 or 1, and all off-diagonal entries are 0; and is defined as

with and is a row vector whose -th element is 1 and all other elements are zero. The function is defined recursively as

Remark 2.

For the ACC system considered in this paper, the number of control inputs is . In this case, and ; therefore, , ; , . In addition, from Lemma 1, the existence of certain scalar variables is guaranteed, and since , there are such scalars. However, it is not necessary to explicitly specify the values of . Due to the convex combination property, is not explicitly considered in the controller design condition. A more detailed analysis can be found in [27,28] and in the following section.

For notational simplicity, we define the following shorthand expressions: and From Lemma 1, the saturation in the controller can be reformulated as shown in (8). Therefore, by substituting (8) into the dynamics (4), the system dynamics becomes

By defining the augmented state vector as , and using the error dynamics in (6) together with (9), the augmented system dynamics can be expressed as the following state space equation:

where

Finally, we define the following main control objective, which is to stabilize the ACC system under input saturation using an observer-based state feedback controller.

Problem 1.

Find gain matrices , , and such that the following conditions are satisfied:

- 1.

- When , the equilibrium of the augmented system (10) is asymptotically stable.

- 2.

- If for all , then .

- 3.

- For and , the following disturbance attenuation performance is satisfied:where is a prescribed scalar; is a diagonal matrix that specifies the relative importance of the state components; and is a prescribed scalar denoting disturbance attenuation level.

3. Main Results

3.1. Observer-Based Control Under Input Saturation

In this subsection, we derive a matrix inequality condition for the augmented system (10) that guarantees the controller design objectives presented in Problem 1. The following theorem provides a sufficient condition for solving the controller synthesis problem stated in Problem 1.

Theorem 1.

For given scalars , , , and , and an initial condition , the augmented system (10) satisfies the design criteria described in Problem 1 if there exist a positive definite matrix , a symmetric matrix , and matrices , , and such that the following matrix inequalities hold for :

where and are symmetric matrices; is a matrix;

Proof.

Please refer to Appendix A. □

Remark 3.

Theorem 1 provides sufficient conditions for designing an observer-based controller that satisfies all the objectives defined in Problem 1. However, the decision variables appear in bilinear and multiplicative forms within the matrix inequalities. Consequently, the problem is not easy to be solved using standard convex optimization software such as CVX [35] or YALMIP [36]. Motivated by the result in [19], we propose a two-step approach for solving matrix inequalities in Theorem 1 using convex optimization software.

3.2. LMI-Based State Feedback Controller Design

As the first step of the proposed approach, we consider the case where full-state feedback is available. This is equivalent to assuming , i.e., the estimation error has perfectly converged. Under this assumption, the state equation in (9) reduces to:

The design objective of the first step is to achieve the following problem:

Problem 2.

Find matrices and such that the following conditions are satisfied:

- 1.

- When , the equilibrium of the closed-loop system (15) is asymptotically stable.

- 2.

- If for all , then .

- 3.

- For and , the following disturbance attenuation performance is satisfied:

The following theorem gives an LMI-based sufficient condition for Problem 2:

Theorem 2.

For given scalars , , , and , and an initial condition , the closed-loop system (15) satisfies the design criteria described in Problem 2 if there exist a positive definite matrix , a symmetric matrix , and matrices and such that (14) and the following matrix inequalities hold for :

where . Then, the control gain matrices can be obtained by

Proof.

Please refer to Appendix B. □

Remark 4.

The LMI conditions in Theorem 2 are the first step of the proposed two-step approach, derived from the BMI formulation in Theorem 1 to compute the controller gain matrices. Consequently, the scalar parameters (γ, μ) and the matrix (Q) defined in Theorem 1 are utilized in Theorem 2 with exactly the same values and physical meanings. Although the gain matrices obtained from Theorem 2 can be substituted into the matrix inequalities in Theorem 1, the resulting condition remains non-convex due to the bilinear terms involving in (11). The introduction of the non-zero off-diagonal block creates coupling terms between the Lyapunov matrix variables and the controller and observer gains (e.g., products such as and ). While standard change-of-variable techniques can linearize terms involving diagonal blocks, they cannot simultaneously linearize the cross-terms involving without introducing non-convexity. Consequently, the inequality contains products of two unknown variables, rendering it a BMI, and it prevents the matrix inequality from being expressed as an LMI. To resolve this problem, we assume in the subsequent subsection.

3.3. LMI-Based Observer-Based Controller Design

By letting , we derive the following sufficient LMI condition for solving Problem 1 from Theorem 1:

Corollary 1.

For given scalars , , , , and , an initial condition , and the control gain matrices, K and H, designed from Theorem 2, the augmented system (10) satisfies the design conditions in Problem 1 if there exist symmetric positive definite matrices , a symmetric matrix , a matrix such that the following LMIs hold:

where , , , . The observer gain matrix can be obtained by .

Proof.

The LMIs (19)–(22) follow directly from Theorem 1 by substituting and . □

Remark 5.

γ determines the disturbance attenuation level; smaller γ improves performance but makes the LMI more conservative. The parameter α represents the decay rate of the Lyapunov function; larger α ensures faster convergence but also increases conservatism. Moreover, these parameters are coupled by the condition . When the LMIs in Corollary 1 become infeasible, feasibility can be recovered by enlarging γ, reducing , recomputing α accordingly, and then resolving the LMIs in Theorem 2 and Corollary 1.

In addition, selecting an excessively large α may lead to unnecessary conservatism in LMI conditions without providing meaningful improvement in control performance. For this reason, in this paper, α is chosen at its lower bound in the simulations so that the required disturbance attenuation is satisfied while maintaining LMI feasible.

Remark 6.

The following LMI conditions can be further considered to explicitly bound the eigenvalues of the system matrices [37]:

where and are the predefined lower bounds of eigenvalues, i.e., with eigenvalue .

4. Simulation Examples

This section presents simulation results to validate the effectiveness of the proposed observer-based control design for ACC systems under input saturation.

4.1. Example 1: Validation of Observer-Based ACC Controller

This example verifies the proposed observer-based controller under input saturation and external disturbance. The vehicle parameters are set to , , and , implying a 2 gap at standstill and a 3-s spacing during steady-state cruising. The leader vehicle starts at with a constant velocity .

The controller is designed using the two-step procedure proposed in Section 3. First, the gain matrices K and H are computed by solving the LMI conditions in Theorem 2, with additional constraints in (23) to limit eigenvalues. The following design parameters are chosen: , , , , , and . The initial states are and , respectively, resulting in the initial estimation error . Under these settings, solving the LMIs (16)–(18) and (23) yields:

In the second step, the observer gain L is computed using the LMI conditions in Corollary 1 along with the eigenvalue bounding constraint in (24). The previously used parameters are retained, with additional design settings and . Solving the resulting LMIs yields the following observer gain matrix:

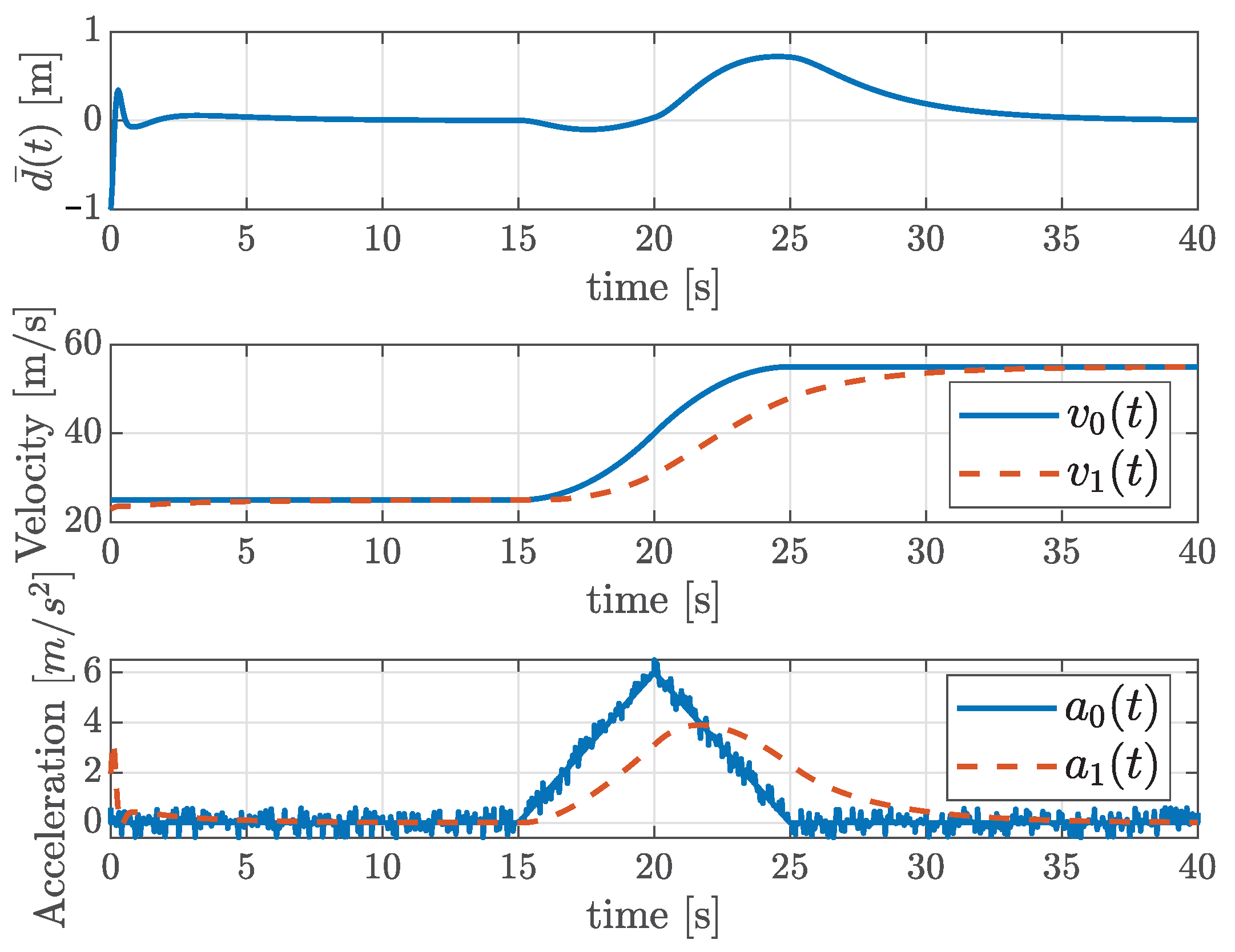

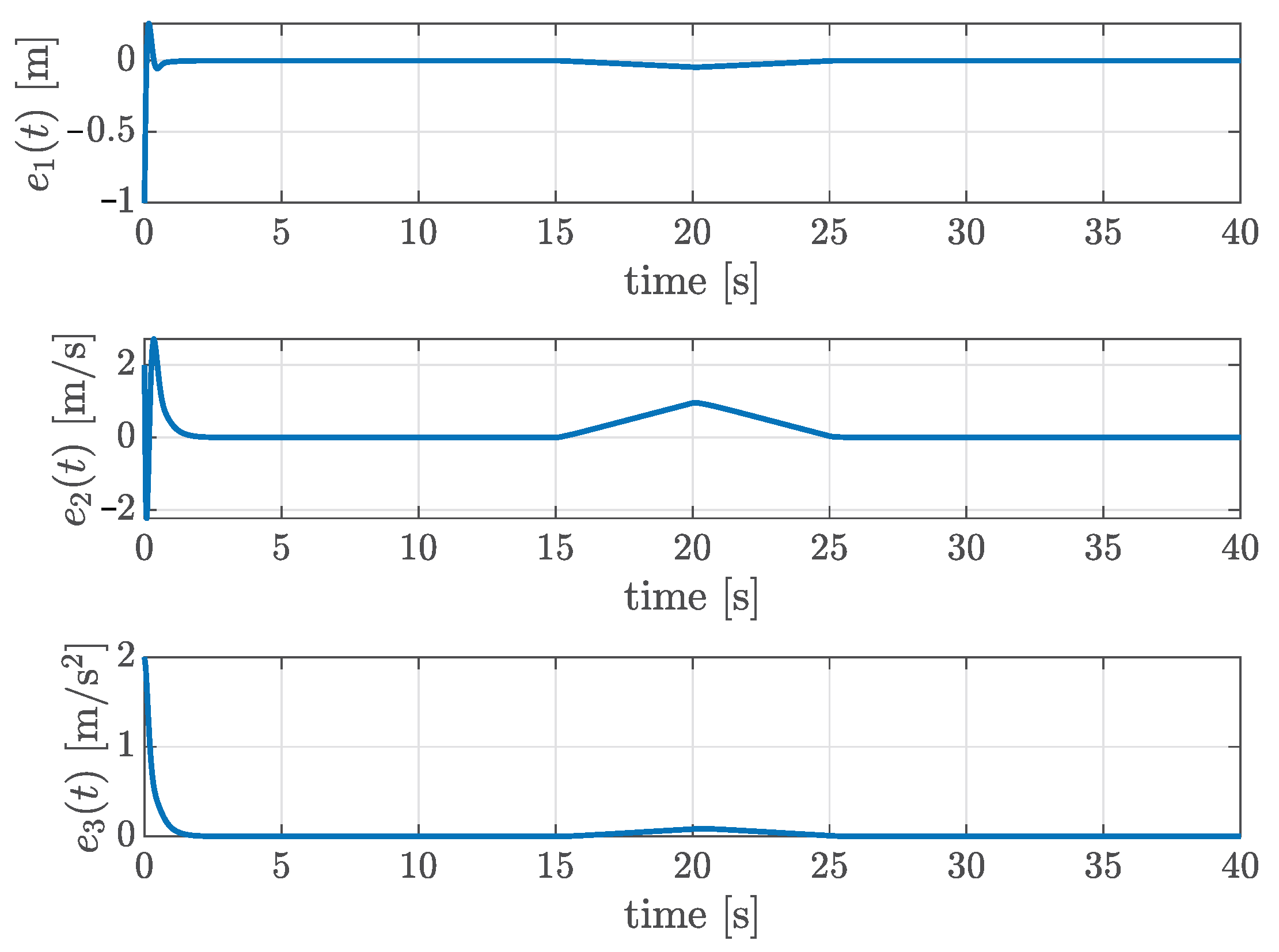

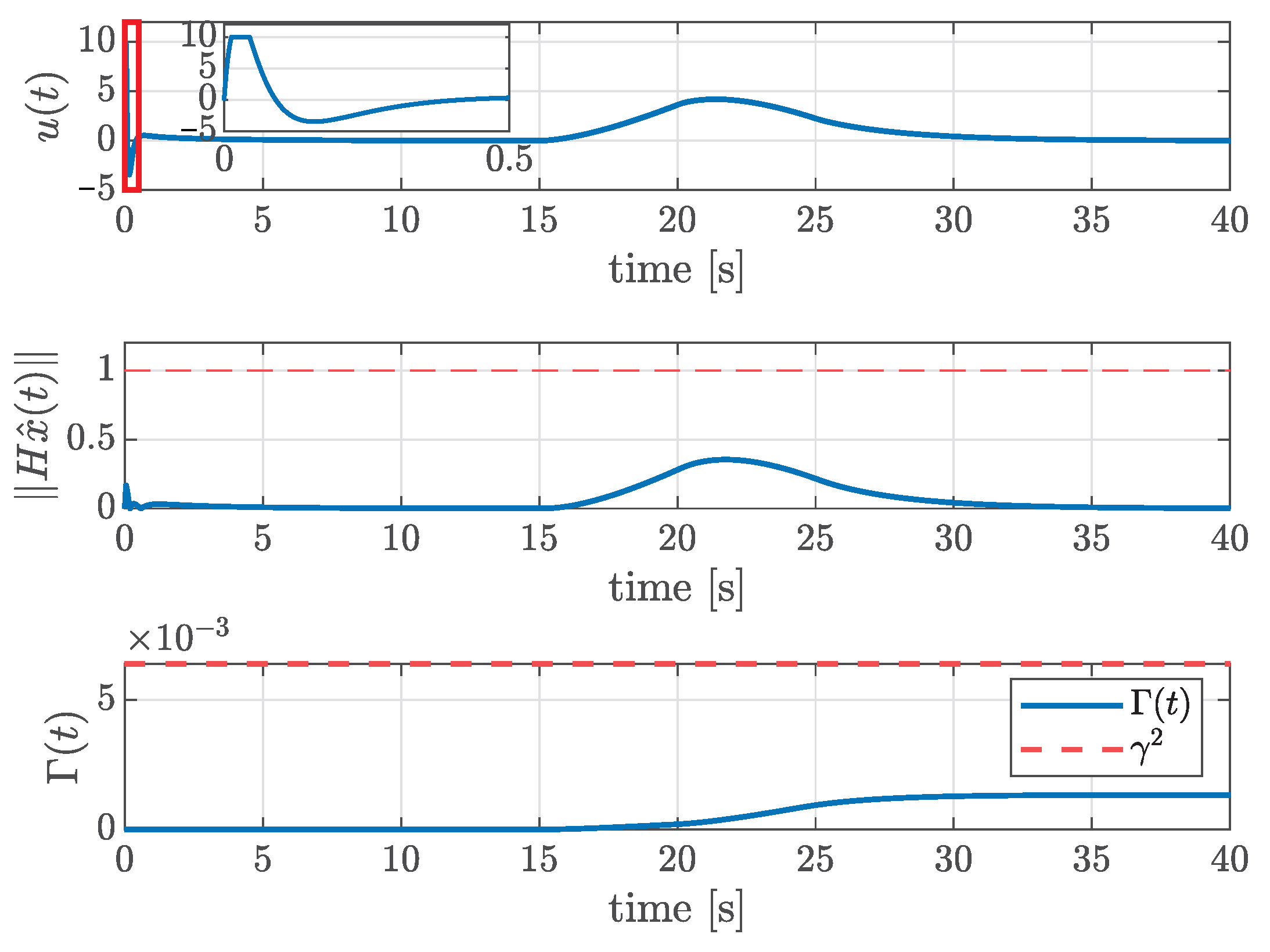

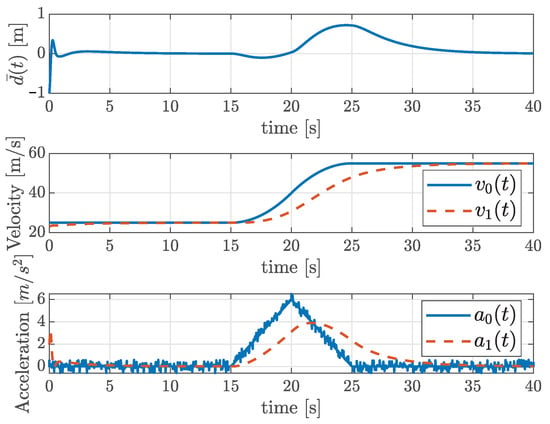

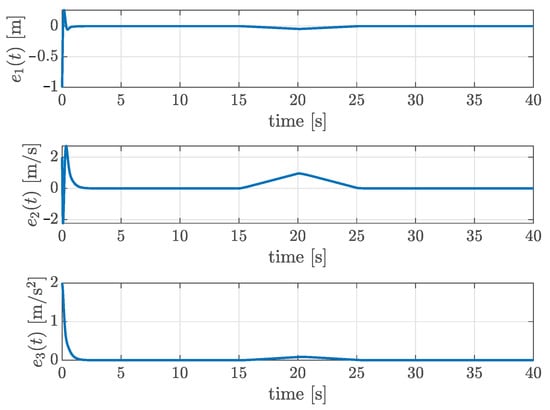

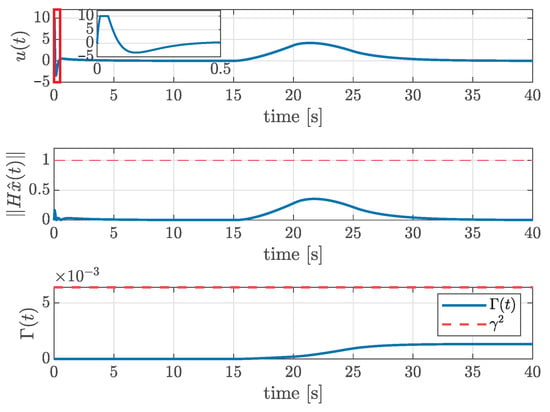

Figure 1 shows the time response of the ACC system. In the simulation, the leader vehicle accelerates as shown in the plot for the time response of the acceleration. To more closely emulate real-world vehicle-operation conditions, a random noise term of was added to the acceleration of the lead vehicle. The state estimation errors are presented in Figure 2. From the figures, we can see that all state variables and all estimation errors converge to zero when , verifying the first condition in Problem 1. Figure 3 illustrates the control input . The input is initially saturated due to a large distance error, but the proposed method ensures . Finally, under the zero initial condition, the disturbance attenuation performance is evaluated using the following performance index: . The maximum value of was measured as , which is lower than the prescribed upper bound , verifying that the third design condition in Problem 1 is satisfied.

Figure 1.

Time responses of the tracking error , velocities of leader and ego vehicles , , and ego vehicle acceleration .

Figure 2.

Time responses of the estimation errors .

Figure 3.

Time responses of , norm with its upper bound, and .

4.2. Example 2: Comparison of Full-State Feedback Controllers

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed full-state feedback controller design, this example compares its disturbance attenuation performance with two baseline controllers. The first baseline ensures only asymptotic stability without addressing disturbance attenuation, while the second considers the disturbance attenuation performance. To reflect the physical limitations of the vehicle, both baseline controllers are designed to satisfy the input constraint instead of input saturation.

As in the previous example, all parameters are the same as in Example 1 except for . Then, we obtained the following gain matrices:

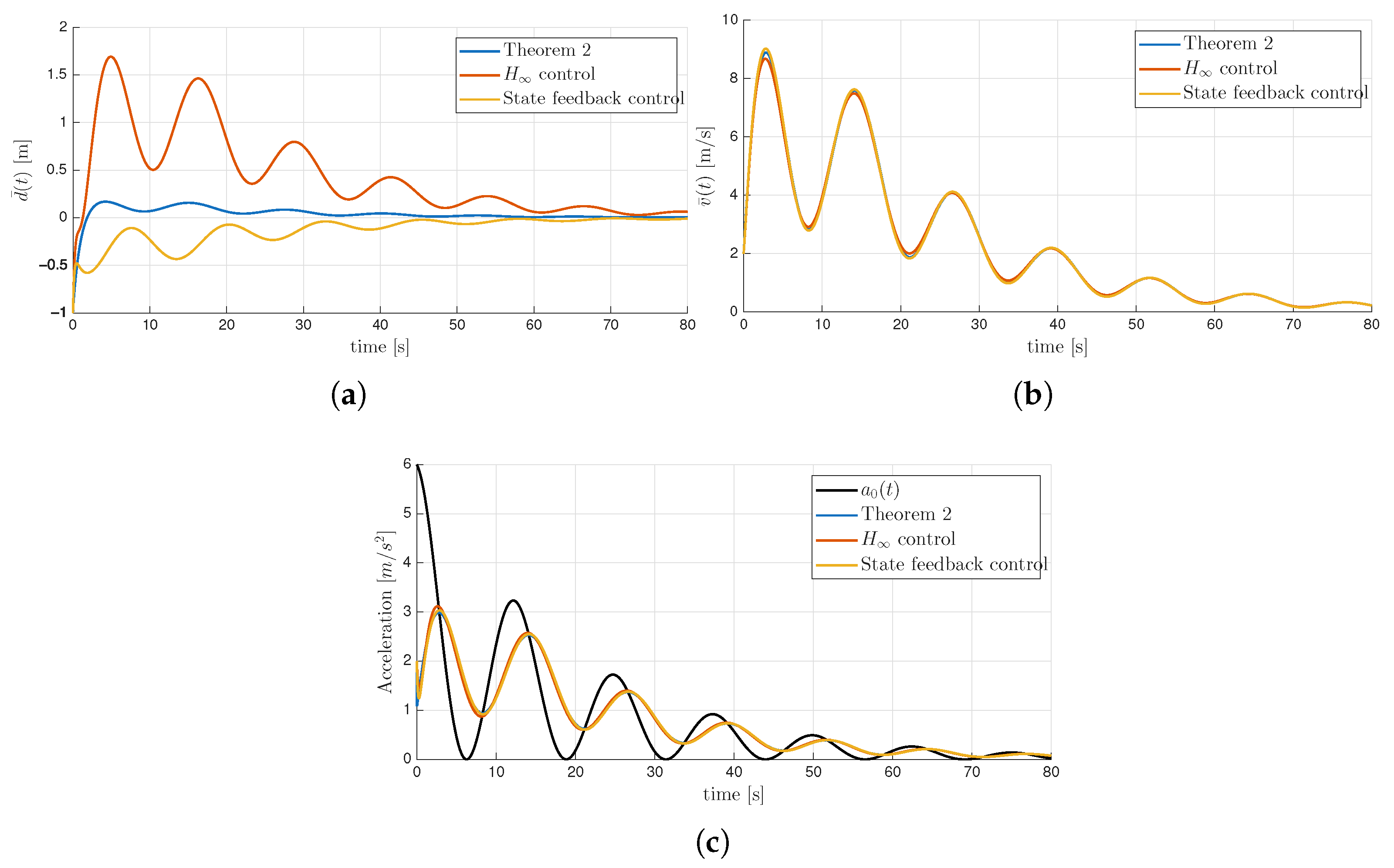

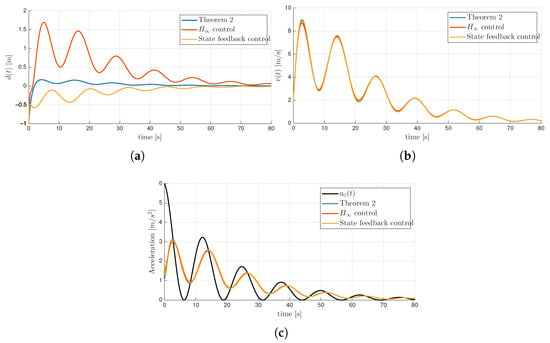

The controller designed from Theorem 2 allows input saturation, resulting in a larger gain K than the baseline controllers. According to the high-gain control principle, we can expect that faster convergence and improved disturbance attenuation performance would be obtained. To compare the disturbance attenuation performance, was defined as follows: . Figure 4 illustrates the state responses from each control methods. As can be observed, the proposed method achieves superior disturbance attenuation performance by explicitly allowing input saturation. The baseline controller designed with conditions shows improved performance compared to the baseline controller that only ensures asymptotic stability; however, due to the absence of saturation consideration, its performance is degraded compared to the proposed method. Finally, the RMS values of position and velocity tracking errors were quantitatively compared and summarized in Table 1.

Figure 4.

Time responses of (a) the distance tracking error , (b) the velocity tracking error , and (c) the acceleration.

Table 1.

RMS value of the distance and velocity tracking errors for each controller.

5. Conclusions

This paper presented an observer-based controller design for ACC systems under input saturation and disturbances. Unlike previous approaches that handled saturation only for state feedback control systems, the proposed method incorporates the estimated state and decay rate of the Lyapunov function while guaranteeing the invariant level set condition. This enables a systematic two-step observer-based controller design that ensures both constraint satisfaction and disturbance attenuation. Simulation results confirmed that the proposed controller provides superior tracking accuracy and robustness compared with conventional designs.

It should be noted, however, that the observer dynamics may be affected by sensor noise, modeling errors, and unmodeled nonlinearities in vehicle behavior, which were not explicitly addressed in this work. Moreover, since ACC systems are implemented digitally, a discrete-time realization or conversion strategy is essential for practical deployment, but was beyond the scope of this study. These aspects will be considered in future research toward the real-world implementation of constrained ACC systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.J.; Methodology, H.J.; Validation, H.J.; Writing—original draft, H.J.; Writing—review & editing, K.L.; Writing—review & editing, H.S.K.; Supervision, H.S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The present research was supported by the research fund of Dankook University in 2025.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in article here.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Proof of Theorem 1

The proof consists of three steps.

Appendix A.1. Asymptotic Stability Without Disturbance

Consider the following Lyapunov function candidate:

and define

where is a scalar satisfying ; and are given positive scalars; and ; and and are given diagonal matrices with positive elements.

Thus, the following matrix inequality

ensures .

Appendix A.2. Invariant Level Set

Next, to guarantee that the level set is satisfied, we introduce the following inequality:

which implies that, for some initial condition, . By applying the Schur complement, we obtain the matrix inequality (12).

Given , we now show that and thus . As already established, the following inequality holds:

Multiplying both sides by yields

Integrating this from to an arbitrary gives

Now, assume that the right-hand side of the above inequality satisfies the following:

Therefore, if , it follows that , which implies .

We now show that if . To this end, we rewrite as

where .

Then, the objective is achieved if

Since is already satisfied, this implication holds if

which can be conservative in practice. To reduce conservatism, we introduce a slack variable such that .

By the Schur complement, the above condition is equivalent to:

which corresponds to (13).

Furthermore, to ensure , it suffices to impose: which is guaranteed by (14).

Therefore, if the matrix inequalities (13) and (14) hold, it follows that

ensuring that . Thus, the second objective in Problem 1 is satisfied.

Appendix A.3. Disturbance Attenuation

We now revisit the following inequality derived previously:

Integrating both sides over the interval gives

Assume and take the limit as . Since for all t, it follows that

which establishes the desired attenuation performance:

This confirms that the third objective in Problem 1 is satisfied.

Appendix B. Proof of Theorem 2

Under the assumption , the Lyapunov function in (A1) becomes , and the associated term is also simplified accordingly: .

Therefore, the inequality reduces to the following matrix inequality:

To convert this into an LMI, we apply a congruence transformation using , where . Then, the above matrix inequality becomes

However, the resulting matrix inequality is still not an LMI due to the term . To resolve this, we apply the Schur complement to the -block of the above matrix and define new variables , , which yields the LMI (16).

In addition, similar to Theorem 1, the condition is satisfied if the following matrix inequality holds:

By applying the congruence transformation with , this is equivalent to the LMI (17).

Furthermore, by the same analysis as in Theorem 1, if , from , it is easy to show that . In addition, from the LMI (18), which is a sufficient condition for , it can be concluded that .

Finally, it can be readily shown from the inequality that the following disturbance attenuation performance is guaranteed:

This completes the proof.

References

- Liu, C.Z.; Li, L.; Chen, X.; Yong, J.-W. An innovative adaptive cruise control method based on mixed H2/H∞ out-of-sequence measurement observer. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 5602–5614. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, X.; Zheng, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, J.; Zheng, H. A novel stochastic model predictive control considering predictable disturbance with application to personalized adaptive cruise control. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2024, 22, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Ram, C.A.R.; Pachamuthu, R. LiDAR sensing-based exponential adaptive cruise control and steering assist for ADAS. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 3597–3607. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Han, K.; Tiwari, P.; Work, D.B. Gaussian process-based personalized adaptive cruise control. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 21178–21189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Wang, Y.; Na, J.; Guo, G.; Zuo, Z.; Gao, H. Optimal adaptive cruise control in mixed traffic with communication latency and driver reaction. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 18636–18647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhao, D.; He, H. Synthesis of cooperative adaptive cruise control with feedforward strategies. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 3615–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.Y.; Peng, H. Optimal adaptive cruise control with guaranteed string stability. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 1999, 31, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, Z.; Kuczmann, M. Linear-matrix-inequality-based controller and observer design for induction machine. Electronics 2022, 11, 3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Liu, M.; Wu, Z.G.; Shi, K. Observer-based sliding mode control for Markov jump systems with actuator failures and asynchronous modes. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2021, 68, 1967–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, Z.; Ma, L.; Liu, H. Observer-based event-triggered control for nonlinear systems with mixed delays and disturbances: The input-to-state stability. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2019, 49, 2806–2819. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, W.X. Fuzzy observer-based repetitive tracking control for nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 28, 2401–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, Z.; Lendek, Z.; Busoniu, L. TS fuzzy observer-based controller design for a class of discrete-time nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2022, 30, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Lee, K. Sampled-data fuzzy observer design for nonlinear systems with a nonlinear output equation under measurement quantization. Inf. Sci. 2021, 575, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.H.; Lee, K.; Kim, H.S. An intelligent digital redesign approach to the sampled-data fuzzy observer design. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 31, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Hwang, S.; Kim, H.S. T–S fuzzy observer-based output feedback lateral control of UGVs using a disturbance observer. Drones 2024, 8, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Duan, G.; Hou, M. State and disturbance observer-based controller design for fully actuated systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2024, 71, 5261–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Song, S. Observer-based sliding mode control for stabilization of mismatched disturbance systems with or without time delays. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2021, 51, 7337–7345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, H.; Nguyen, N.P.; Ghadiri, H.; Mobayen, S.; Bayat, F.; Skruch, P. LMI-based Luenberger observer design for uncertain nonlinear systems with external disturbances and time-delays. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 71823–71839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lens, H.; Adamy, J. Observer based controller design for linear systems with input constraints. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2008, 41, 9916–9921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Mu, D.; Wang, G.; Fan, Y. Trajectory tracking control for unmanned surface vehicle subject to unmeasurable disturbance and input saturation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 191278–191285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Li, H.; Dong, G.; Lu, R. Event-triggered control for multiagent systems with sensor faults and input saturation. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2021, 51, 3855–3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lam, H.-K.; Qiu, J.; Qi, P.; Chen, Q. Fuzzy-model-based output feedback steering control in autonomous driving subject to actuator saturation. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 29, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Deng, H. Robust stabilization of uncertain switched nonlinear systems with hybrid saturated inputs. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2023, 53, 5084–5095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Ge, S.S.; Ren, B. Adaptive tracking control of uncertain MIMO nonlinear systems with input constraints. Automatica 2011, 47, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzaouia, A.; Mesquine, F.; Benhayoun, M. Saturated Control of Linear Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q. Observer-based path tracking controller design for autonomous ground vehicles with input saturation. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2023, 10, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiko, S.; Mesquine, F. Constrained control for a class of TS fuzzy systems. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 31, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B. Analysis and design of discrete-time linear systems with nested actuator saturations. Syst. Control Lett. 2013, 62, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatavi, M.; Vu, M.T.; Mobayen, S.; Fekih, A. H∞ robust LMI-based nonlinear state feedback controller of uncertain nonlinear systems with external disturbances. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, Z.; Ding, D.; Wei, G. H∞ PID control with fading measurements: The output-feedback case. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2020, 50, 2170–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Feng, G. Finite-time H∞ controller synthesis of T-S fuzzy systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2020, 50, 1956–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wu, J.; Su, H. V2V-based cooperative control of uncertain, disturbed and constrained nonlinear CAVs platoon. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 1796–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Fu, C.; Li, K.; Hu, M. Spacing policies for adaptive cruise control: A survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 50149–50162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Lin, Z. Control Systems with Actuator Saturation: Analysis and Design; Birkhäuser: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, M.; Boyd, S. CVX: Matlab Software for Disciplined Convex Programming, Version 2.2. Available online: http://cvxr.com/cvx (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Löfberg, J. YALMIP: A toolbox for modeling and optimization in MATLAB. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, New Orleans, LA, USA, 26 April–1 May 2004; pp. 284–289. [Google Scholar]

- Chilali, M.; Gahinet, P. H∞ design with pole placement constraints: An LMI approach. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1996, 41, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).