1. Introduction

The primary functions of a vehicle suspension system are to provide a comfortable ride by insulating passengers from road irregularities, maintaining road contact between the tires and the road surface, and minimizing suspension rattle space. Ride comfort and road contact are key performance indicators; however, due to the trade-off relationship, extensive research and development have been conducted on electronically controlled suspension systems. Active and semi-active suspension systems were first proposed in the early 1970s and have proven to achieve superior performance relative to system cost when compared to active suspension systems [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Many studies have been conducted to optimize system control performance by utilizing three performance indicators: tire force, suspension displacement, and body acceleration. Karnopp et al. [

2] proposed the Skyhook control law, a representative semi-active system that applies the concept of controlling damping force by connecting the body (spring mass) to a “point fixed in the sky.” This method significantly improved ride comfort.

Semi-active suspension actuator systems have undergone significant improvements, and the theoretical foundation for control systems has been established. Regarding actuator systems, the development progressed from a single-stage damper system with multiple damping modes to a continuously variable damper system using proportional solenoids. Damping characteristics have been developed into a reverse type, where only tension and compression are varied when current is applied, and a normal type, where both tension and compression damping are firmed. Reverse-type dampers enable Skyhook control without requiring wheel-side information, but this comes at the cost of increased hardware complexity. Normal-type variable dampers, on the other hand, offer reduced complexity and improved responsiveness, but require the use of wheel-side information. Consequently, the industry is commercializing systems tailored to each company’s control system performance objectives.

Regarding ride comfort control, many studies have utilized modern control techniques to optimize the three performance indicators mentioned above. Cheok et al. [

5] derived the control logic for a variable damper using the concept of “optimal model tracking.” This was later demonstrated by Tseng et al. [

6], differs from accurate optimal control in the sense of minimizing secondary performance indicators (minimizing model tracking errors). However, this represents a pioneering form of a practically feasible sub-optimal control law. Tseng and Hedrick [

7] expressed the inherent nonlinearity of conventional semi-active suspension systems as a bilinear model and demonstrated that Clipped Optimal Control [

6], which tracks the optimal control input of an active suspension system with a variable damper’s damping force, is not mathematically optimal. They clarified that the proper optimal solution is related to the time-varying Riccati equation. This paper clearly distinguishes between “clipped optimality” and “optimal model following” as suboptimal approaches that pursue instantaneous optimization. Rajamani and Hedrick [

8] experimentally confirmed the fundamental limitations and potential of semi-active control (following the best passive performance), and specifically, clarified that physical constraints of the damper (e.g., delay due to low bandwidth) can severely degrade performance. This highlights the importance of not only the design of the control algorithm but also the hardware implementation capability. Furthermore, they proposed and verified a method to optimize the H-infinity norm or H2 norm of the ride comfort index under disturbances through H-infinity control [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Furthermore, studies have been conducted to further improve ride comfort through Skyhook-ADD [

16], which integrates acceleration information into the existing Skyhook control. Recently, with the advancement of actuator systems, research has been conducted on further performance enhancement through preview control in conjunction with active suspension [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Techniques have been proposed to optimize vehicle performance by detecting the road surface in advance and to compensate for the delay of the actual semi-active damper.

Several papers have proposed methods to enhance vehicle handling stability during cornering by utilizing semi-active suspension control [

22,

23]. Bodie and Hac [

24] proposed a closed-loop yaw control that compensates for oversteer/understeer in real time by manipulating the MR damper distribution to bring the vehicle yaw rate closer to a desired value. They also proposed that yaw moment control can be achieved by adjusting the lateral force balance through the distribution of front and rear damping forces, thereby maintaining vehicle yaw stability. Guo et al. [

25] reduced body roll by continuously adjusting the damping force installed in the front suspension, and the AFS stabilized the vehicle’s yaw behavior through sliding mode control (SMC). The two controllers were integrated using fuzzy logic, and experimental and simulation results verified that the integrated controller improved vehicle steering maneuverability and ride comfort compared to two independent controllers. They confirmed that damping force adjustment played a significant role in improving roll moment distribution and yaw stability. Van der Sande [

26] discussed the control design of a semi-active suspension and the enhancement of steering stability through steer-by-wire. Based on optimal control using MPC, a rule-based semi-active damping controller that can be implemented in real time was developed. Through this, it was confirmed that the ride comfort can be improved in an actual vehicle, and the lateral acceleration overshoot of the vehicle can be mitigated by adjusting the roll axis damping force during cornering. Her et al. [

27] performed target roll moment control in the upper logic using the sling mode control technique before implementing chassis-integrated control. They dynamically generated the target moment through damper actuator damping force control in the lower logic and confirmed, through simulation, that the yaw behavior of the vehicle could be improved.

Lu et al. [

28] demonstrated that integrated control effectively improves yaw angle and vehicle turning performance compared to standalone control by increasing the outer suspension damping force in roll axis control to ensure driving stability.

Previous studies have primarily focused on ride comfort and roll behavior control on high-friction (high-μ) surfaces, failing to sufficiently verify the effectiveness of damping force distribution control in low-friction (low-μ) environments and ensuring steering stability. Furthermore, research on the interaction between damping force response delay and yaw compensation moment generation due to load transfer in real-world applications of semi-active control has been insufficient. To address these limitations, this paper develops an integrated roll/yaw control logic for a semi-active ECS based on the Swedish Arjeplog snow test. Through experimental verification on low-friction surfaces, this paper quantitatively demonstrates the vehicle stability enhancement effect of front and rear damping force distribution. In particular, by experimentally demonstrating the additional yaw stabilization contribution that semi-active damping force control can provide through cooperative control with VDC, we aim to demonstrate the potential for improving the low-friction driving performance of semi-active suspension systems.

This paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the structure and operation of a reverse-type continuously variable damper, utilizing a proportional control solenoid. This includes the design of the pilot-controlled proportional valve, the damping force characteristics, and the actuator response performance.

Section 3 describes the semi-active control logic architecture, based on Skyhook control and integrated handling control, which consists of a ride control algorithm and roll rate reduction and yaw moment compensation using roll moment distribution.

Section 4 provides a brief description of the low-friction road environment and test scenarios conducted at the Arjeplog Snow Test Track in Sweden.

Section 5 presents experimental handling results under various activation cases of the ECS and VDC and discusses improvements in yaw stability and roll behavior. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper and suggests future research directions for extending the semi-active control performance to various road conditions.

2. Continuous Variable Semi-Active Damper

Recently, Magneto-Rheological (MR) dampers have been applied to various vehicles due to their fast response and wide control range. However, the most widely used semi-active suspension technology in mass-produced vehicles is still the hydraulic proportional solenoid-based Continuously Variable Damper (CDC) system. Hydraulic systems offer advantages in terms of manufacturing cost, durability, temperature stability, compatibility with existing suspension structures, and practical benefits such as high repeatability, even under harsh winter vehicle testing conditions.

The reverse-type CDC damper used in this study features independent rebound/compression control, as well as post-blowoff damping force gradient control, via a Pilot-Controlled Proportional Valve (PCPV). This structure is considered suitable for experimentally isolating and analyzing the physical effects of changes in damping force distribution on roll speed, front-to-rear load transfer, and yaw compensation moment generation in low-friction environments.

2.1. Reverse Type Damper

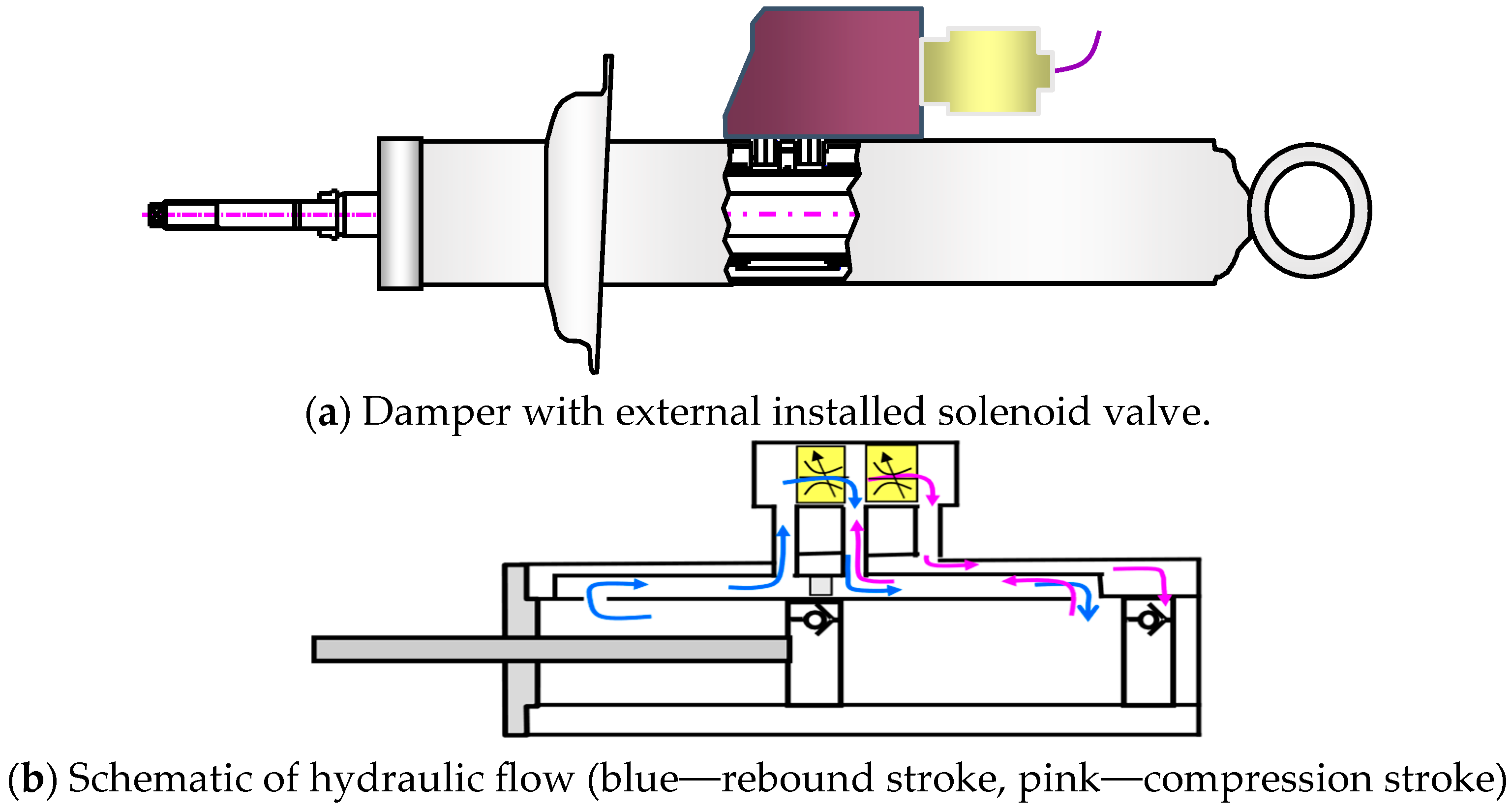

This study utilizes a reverse damper that incorporates a variable valve utilizing a proportional control solenoid. The applied damper features a variable valve mounted outside the damper, allowing for the adjustment of damping force during both rebound and compression strokes. This damper consists of a piston rod, a piston mounted at the end of the rod that separates the rebound chamber and the compression chamber, an inner cylinder that guides the piston’s reciprocating motion, a body valve and a rod guide mounted at the end of the cylinder, an intermediate cylinder that forms a flow path for oil from the rebound and compression chambers to the variable valve, a reservoir guide that is mounted on the intermediate cylinder and prevents gas from the reservoir from entering the variable valve, a valve adapter and valve plate that connect the intermediate cylinder and reservoir guide to the variable valve, a base shell that forms a reservoir with these structures, and a ling guide that is equipped with an oil seal and is mounted on the piston rod to secure the rod guide and inner cylinder to the base shell.

Figure 1 illustrates the oil path when the damper is in operation. During the rebound stroke, oil flows from the rebound chamber through the upper piston, through the rebound variable valve, and into the compression chamber at the bottom of the inner cylinder. It then flows through the resistance chamber and body valve, entering the compression chamber. The oil flow rate is expressed as the difference between the effective piston area and the load area multiplied by the piston speed. During the rebound stroke, the damping force is primarily generated by the flow resistance through the rebound variable valve. This is explained by the pressure increase within the chamber due to increased flow resistance.

Conversely, during the compression stroke, oil flows from the compression chamber through the piston valve and into the rebound chamber, with some of the flow entering the reservoir through the lower cylinder bore and the resistance chamber guide. The compression variable valve primarily generates the damping force, and, as in the rebound stroke, is explained by the pressure increase due to flow resistance. Therefore, the damping force is controlled according to the flow resistance characteristics of the valves during both the rebound and compression strokes, and each valve is designed to operate independently without interference.

2.1.1. Variable Valve

In this study, we designed a variable valve capable of continuous damping force control by utilizing a Pilot Controlled Proportional Valve (PCPV) mechanism that can gently adjust the slope of the damping force characteristic curve after blow-off. Conventional electronically controlled variable valves control flow rate by controlling spool opening but suffer from a rapid increase in damping force after blow-off. The PCPV structure employed in this study precisely controls the pressure differential acting on the spool through a small pilot flow path, smoothly varying the slope of the damping force-velocity curve according to the control current. This suppresses the rapid pressure increase that occurs in the nonlinear region of damping force and ensures continuity in damping force response to changes in control input.

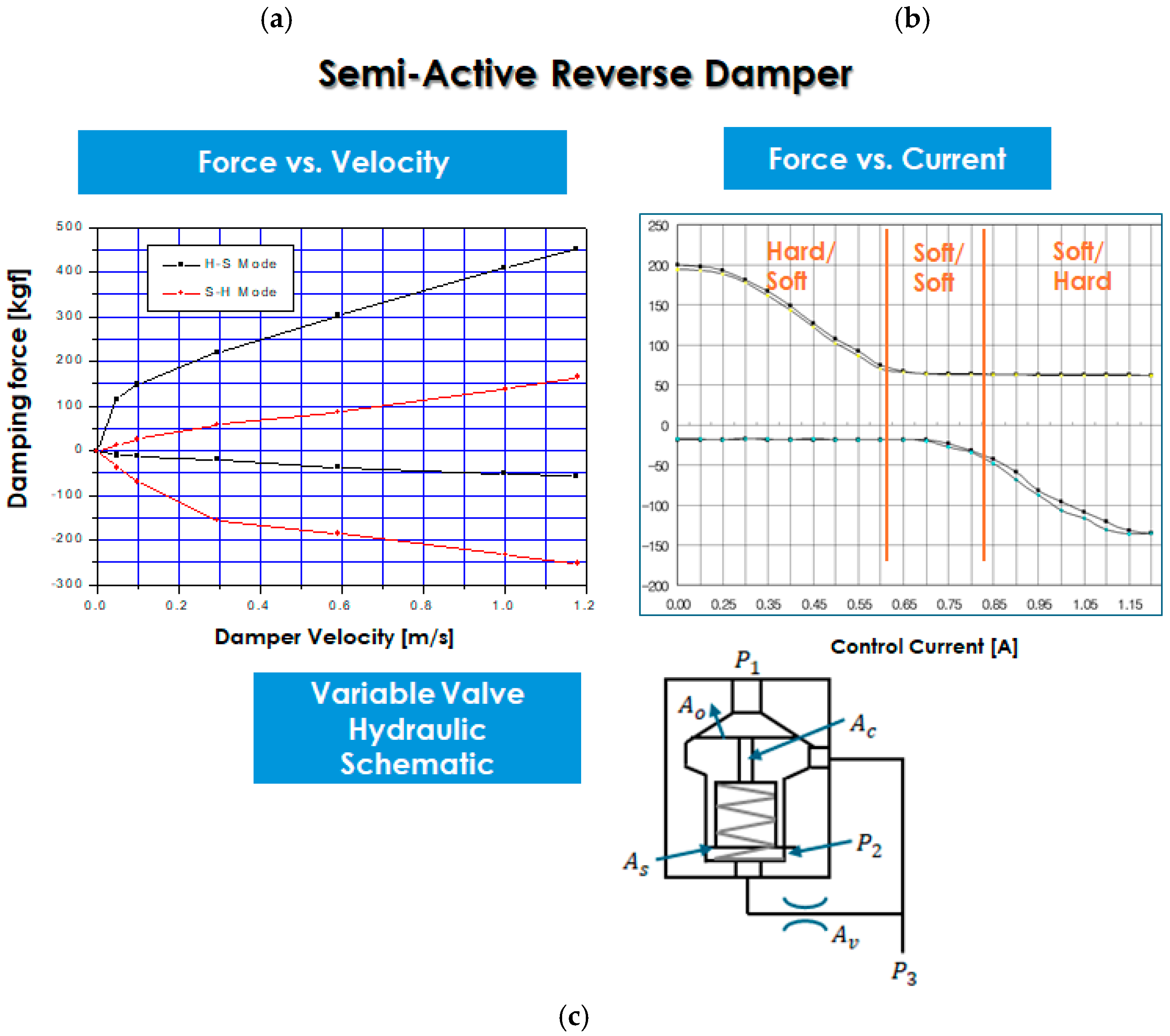

The developed variable valve is designed to independently control the damper’s rebound and compression chambers, achieving the desired damping force characteristics without mutual interference during each stroke. As shown in

Figure 2, this system is configured to implement three control modes: ① Soft–Hard (S–H) mode, with soft rebound and hard compression; ② Soft–Soft (S–S) mode, with soft rebound and soft compression; and ③ Hard–Soft (H–S) mode, with hard rebound and soft compression. These control modes are switched in real time by adjusting the spool opening and pilot pressure, allowing for continuous adjustment of the damping force ratio based on driving conditions (vehicle speed, steering, road friction coefficient, etc.).

This reverse-type variable valve structure exhibits significant changes in damping force on the rebound side and relatively small changes in damping force on the compression side. This enables stable ride quality and steering responsiveness in Skyhook-based semi-active control systems without requiring wheel-side information. Furthermore, the application of the PCPV mechanism minimizes hysteresis between the current input and the damping force response, thereby improving the linearity of the damping force control and facilitating integration with control logic. Therefore, the variable valve in this study can be considered a key component for semi-active ECS, as it simultaneously satisfies continuous controllability, stability in the post-blow-off region, and rapid response.

In this study, a variable valve, as shown in

Figure 2c was used to generate pressure in a damper. In

Figure 2c,

is a fixed orifice with a constant size, and

is a variable orifice whose size can be varied by solenoid current control. These two orifices determine the control pressure (pilot chamber pressure)

. In this valve, the variable orifice determines only the pilot chamber pressure; therefore, if the flow rate through the variable orifice exceeds a specific limit, the valve opens, allowing oil to flow directly to the low-pressure side. In the figure, before the valve begins to open (i.e., before blow-off occurs), the oil flow path passes through

and

, as shown in Equation (1).

If we calculate the force (

) that tries to open the valve based on

, it is as shown in Equation (2).

And the force (

) that tries to close the valve is as shown in Equation (3).

and

are the cross-sectional areas of the two ends of the valve, and

is the spring preload acting on the valve. Since blow-off occurs when these two forces are equal, the two equations above can be rearranged into Equation (4).

Therefore, the flow rate at which blow-off occurs can be obtained as a function of

as shown in Equation (5) below.

In this equation, since

is a constant value, if

>

, the variable orifice becomes smaller, and when

becomes smaller, the flow rate Q at the blow-off point becomes smaller. And if we calculate the relationship between the pressure and flow rate at which blow-off occurs,

becomes Equation (6).

By applying Equation (4) and rearranging Equation (6), the pressure difference across the variable valve can be expressed as Equation (7).

When , the blow-off pressure changes little depending on the error. In addition, when orifice increases steadily, the blow-off pressure decreases relatively uniformly, allowing a large pressure to be generated even at a small flow rate, and the pressure limit can be set accordingly. The pressure-flow characteristics of the variable valve are directly reflected in the damping force characteristics proposed in this study.

2.1.2. Damper Actuator Response Performance

The responsiveness of a variable damper affects the overall control bandwidth of the system. Key factors influencing responsiveness include damper size and pressure changes due to flow conditions, which can be expressed as Equation (8).

To verify the responsiveness, experiments were conducted in a damper rig, and a triangular wave displacement excitation was input to establish a constant speed condition. A responsiveness test was conducted by applying a control current when the input displacement stroke was ±20 mm, and the excitation was performed at a frequency of 1 Hz. The tests were conducted by separating the tension and compression strokes.

Figure 3 summarizes the changes in damping and responsiveness for tension and compression. The damping force fluctuations differ due to the difference in the tension and compression flow rates at the same damper speed, and the damping force fluctuations on the tension side are large.

Furthermore, the soft-to-hard damping test mode, which builds up the damping force, exhibits slower responsiveness than the hard-to-soft damping test mode, which reduces the damping force. The responsiveness varied depending on the damper excitation conditions. However, it was measured to be around 60 ms at most, indicating that the system can control the 0.5 to 3 Hz range, which is a key frequency band for body and handling.

2.1.3. Damping Force

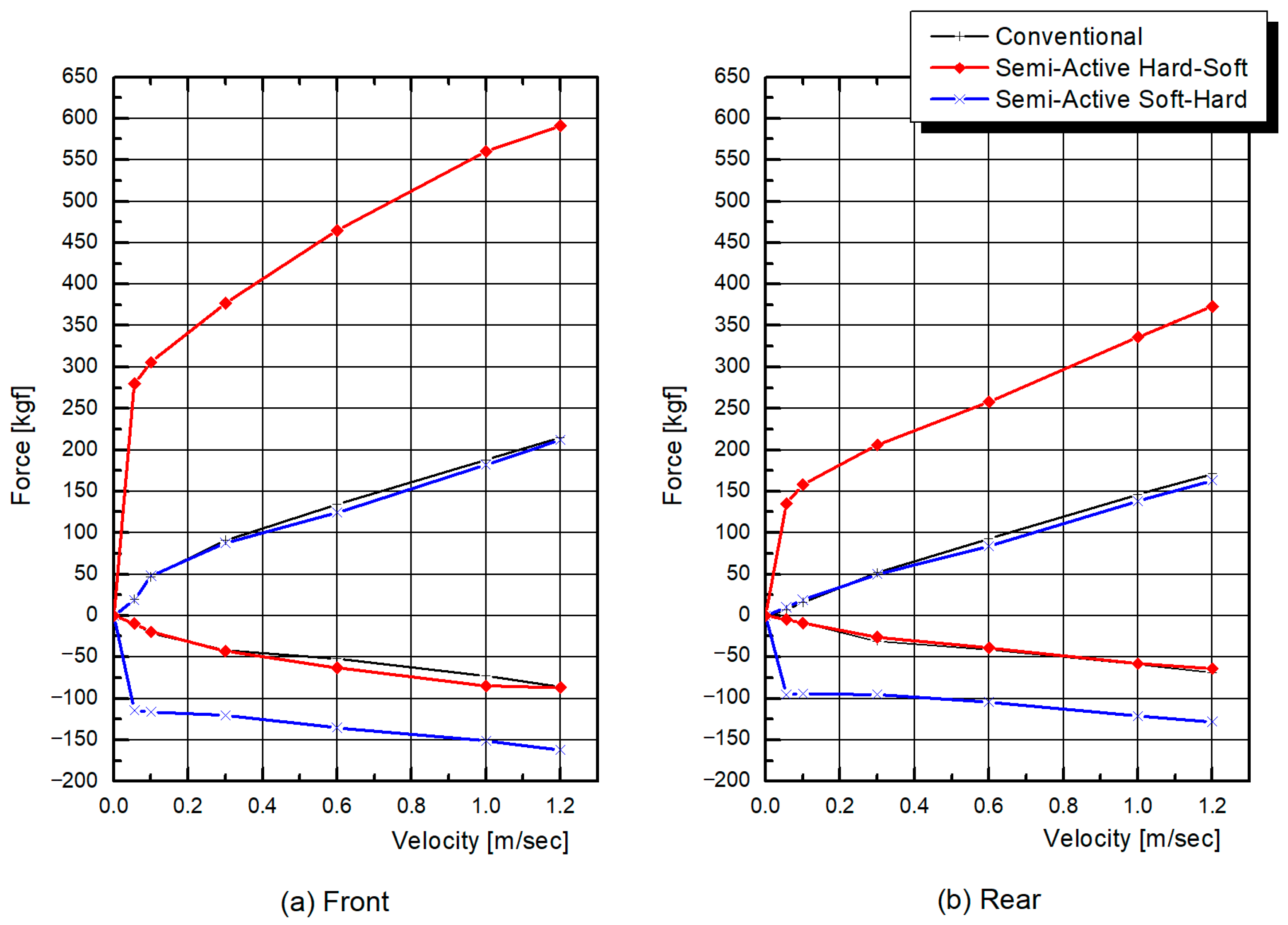

Figure 4 shows the damping force–speed characteristics of the semi-active ECS damper set for the front (a) and rear (b) wheels. These characteristics were checked based on the control current maps for each axle during the pre-test tuning phase. They were designed to balance driving stability and ride comfort by adjusting the damping force ratio in low- and high-speed ranges.

The Hard–Soft mode (red line) provides a high damping force in the low-speed range, enhancing steering responsiveness and roll control. The damping force is relaxed at high speeds, ensuring a comfortable ride despite rough road conditions. Conversely, Soft–Hard mode (blue line) provides low damping force in the low-speed range to enhance road tracking and increases damping force in the high-speed range to stabilize the vehicle’s pitching and yaw behavior. These damping force settings serve as the basic settings for adapting to changes in road friction coefficient and vehicle behavior and were used as the baseline for detailed adjustments during subsequent vehicle testing.

3. Semi-Active Control Logic

This chapter describes the control logic structure and core algorithms of a semi-active electronically controlled suspension (ECS). The control system consists of a ride controller centered on skyhook control and a handling controller to suppress roll behavior during steering. The ride controller utilizes body acceleration signals to adjust damping force in real-time, thereby minimizing body vibration. The handling controller calculates roll damping force distribution and yaw compensation moment based on steering angle and vehicle speed information. The two controllers operate in parallel, performing independent damping force control for each wheel.

Furthermore, anti-dive/anti-squat compensation logic is additionally applied by detecting vehicle acceleration/deceleration states (throttle position, brake switch). The system is designed to respond to frequency-dependent road disturbances through a speed-based damping force compensation function during high-speed driving. This architecture is extended to enable signal exchange with the VDC system via the Controller Area Network (CAN), thereby enhancing yaw stabilization. Hereafter, the mathematical models and algorithms for each detailed controller—Skyhook-based ride control (

Section 3.1) and roll/yaw integrated control (

Section 3.2)—are described in detail.

Figure 5 shows the main modules that constitute the semi-active control logic.

3.1. Ride Control (Skyhook Control)

The Skyhook control logic applied in this study was used as a basic controller to suppress body vibration and ensure damping force control reliability in response to irregular disturbances on low-friction roads. In this paper, a frequency-adaptive Skyhook control technique is applied to address the road surface frequency range encountered in low-friction road conditions.

The vehicle velocity response is estimated based on signals from a vertical acceleration sensor mounted on the vehicle body, and the Skyhook damping force is calculated using the difference in relative speed between each wheel. The calculated ideal damping force is converted into solenoid current through a control current-damping force static map. The actual damping force is reliably implemented through nonlinear section compensation and current rate-limit constraints.

Furthermore, instead of achieving a fixed ride comfort gain, this control utilizes a frequency-weighted filter to reflect the frequency response characteristics, which vary depending on vehicle speed and road conditions. This approach enhances the damping force within the body resonance range of 0.5–3 Hz. It reduces the damping force in the high-frequency range, thereby achieving a balance between ride comfort and handling stability. This Skyhook control serves as the foundational control for the roll suppression and yaw compensation logic presented in

Section 3.2, providing stable damping force control for irregular body vertical motions that occur during low-μ driving. Where

represents the vertical velocity of the sprung mass, and

represents the vertical velocity of the unsprung mass.

Figure 6 illustrates a simplified 1/4 vehicle model for implementing skyhook control.

The vertical velocity

of the body can be formulated into a state space equation form as Equation (11) using quarter car dynamics.

Here, the Skyhook force can be defined by Equation (12),

is the Skyhook damping coefficient, and the absolute velocity

of the body. The body’s vertical velocity

, when applied to the Skyhook logic, applies

with a weighting factor based on frequency. Here,

is the body vertical acceleration magnitude component calculated by passing through a 10 Hz bandpass filter.

Since the damping coefficient of an actual semi-active damper varies depending on the damper speed and control current, it exhibits nonlinear characteristics. When a nonlinear damper is applied, the actual damping force is limited to

, so the input is defined as in Equation (13).

Here, additional signal processing is required to apply the nonlinear characteristics to the linear Skyhook controller. The damper’s damping force characteristic has an arctangent shape, and each solenoid control current generates the damping force. Utilizing this static characteristic, the Skyhook force can be expressed according to Equation (14). Therefore, a linear controller was implemented that defines a combination of linear functions capable of compensating for the static nonlinear characteristics. Therefore, a map can be created to convert the damper characteristics described in the previous section into a partial linear function.

It is also applied independently to each wheel and utilizes three vertical sensors mounted on the vehicle body. For one section without a vertical acceleration sensor, the vertical acceleration of the vehicle body is estimated using the data from the three sensors.

: front left, front right, rear left acceleration signal;

: front tread, rear tread;

: skyhook gain for each rebound and compression side.

In summary, Skyhook control is defined by Equation (16) and is controlled by reflecting the hardware characteristics of the semi-active damper.

3.2. Handling Control

When a vehicle rolls in response to steering input, the vertical loads on the left and right tires change asymmetrically. Since tire lateral force exhibits nonlinear characteristics not only with respect to slip angle but also with respect to vertical load, the increase in lateral force due to an increase in load on the outer tire does not fully compensate for the loss of lateral force due to a decrease in load on the inner tire. Consequently, the effective cornering stiffness of the corresponding axle is reduced, resulting in temporary understeer or oversteer [

29,

30].

In this case, the damping force distribution of the semi-active damper controls the roll rate and the transition speed of load transfer. Differentially adjusting the front and rear damping forces, or rebound and compression damping forces, changes the roll behavior, which in turn alters the instantaneous distribution of tire vertical load, generating a compensating yaw moment that improves steering stability. In this study, we experimentally validated a roll-yaw integrated handling control strategy that utilizes a load transfer-tire nonlinearity-based mechanism in a low-μ environment.

Handling control is an upper-level control function that is added to the ride-oriented Skyhook control to improve the vehicle’s lateral behavior and steering responsiveness. This control aims to secure the vehicle’s lateral stability by controlling the roll motion and load transfer that occur during vehicle steering, and to improve controllability on low-friction roads. The control logic primarily consists of a roll rate controller (

Section 3.2.1) and a yaw controller (

Section 3.2.2) that utilizes roll moment distribution, generating a compensating yaw moment by adjusting the ratio of front and rear wheel damping forces.

3.2.1. Roll Rate Control (Anti-Roll Control)

Anti-roll control logic suppresses vehicle roll by increasing the damping force of the damper during steering. It detects the driver’s steering input from the steering angle sensor and controls the transient region of the vehicle’s behavior. Lateral acceleration is proportional to the square of the vehicle’s speed and the steering angle component. Therefore, as shown in the equation below, the signal from the steering angle sensor is processed to obtain the steering angular velocity, which can then be calculated by taking into account the vehicle speed and the change in lateral acceleration as shown in Equation (17).

: steering gear ratio (= 17.8): : steering wheel angle rate (rad/s);

: wheel base (= 2.745 m) : vehicle speed (m/s);

: characteristic speed.

In an actual system, a delay in the lateral acceleration response to steering input occurs, so

is calculated after additional signal processing to take this into account. The control amount for roll control alone is calculated as in Equation (18).

3.2.2. Yaw Moment Control

The basic concept used in this study is based on the MR-damper-based yaw-stabilization principle proposed by Bodie and Hac [

24], while the analytical formulations presented in Equations (13)–(15) adapt and extend their model by modifying the roll-damping term and the front–rear damping-force distribution ratio to incorporate the real-time proportional control current of a reverse-type semi-active ECS. The model proposed a method to generate a compensating yaw moment by utilizing the nonlinearity of the tire lateral force damping characteristics and the axle-specific load transfer (ΔFz) according to the roll damping force distribution. In this paper, based on this, the roll damping term and the damping force distribution ratio (ρ) are modified to be adjusted in real time by the proportional control current to reflect the control characteristics of an actual semi-active ECS system.

The input of the control system is the front damping distribution ratio (

) to total roll damping, which, in combination with the transient state roll angular velocity (

), determines the load transfer (

) between the front and rear wheels. The vertical load transfer is calculated by Equation (13).

Here, and represent front/rear wheel roll stiffness, represents total roll damping, represents roll angle, and represents track width.

The tire lateral force has a nonlinear relationship not only with the slip angle but also with the vertical load. By using a second-order polynomial model that combines the linear region and the limit region, the compensating yaw moment generated in the vehicle when the left-right load transfer occurs can be calculated as shown in Equation (20) below.

Here, , are load transfer sensitivity coefficient(linear/limit), is the case of the maximum understeer yaw moment creation

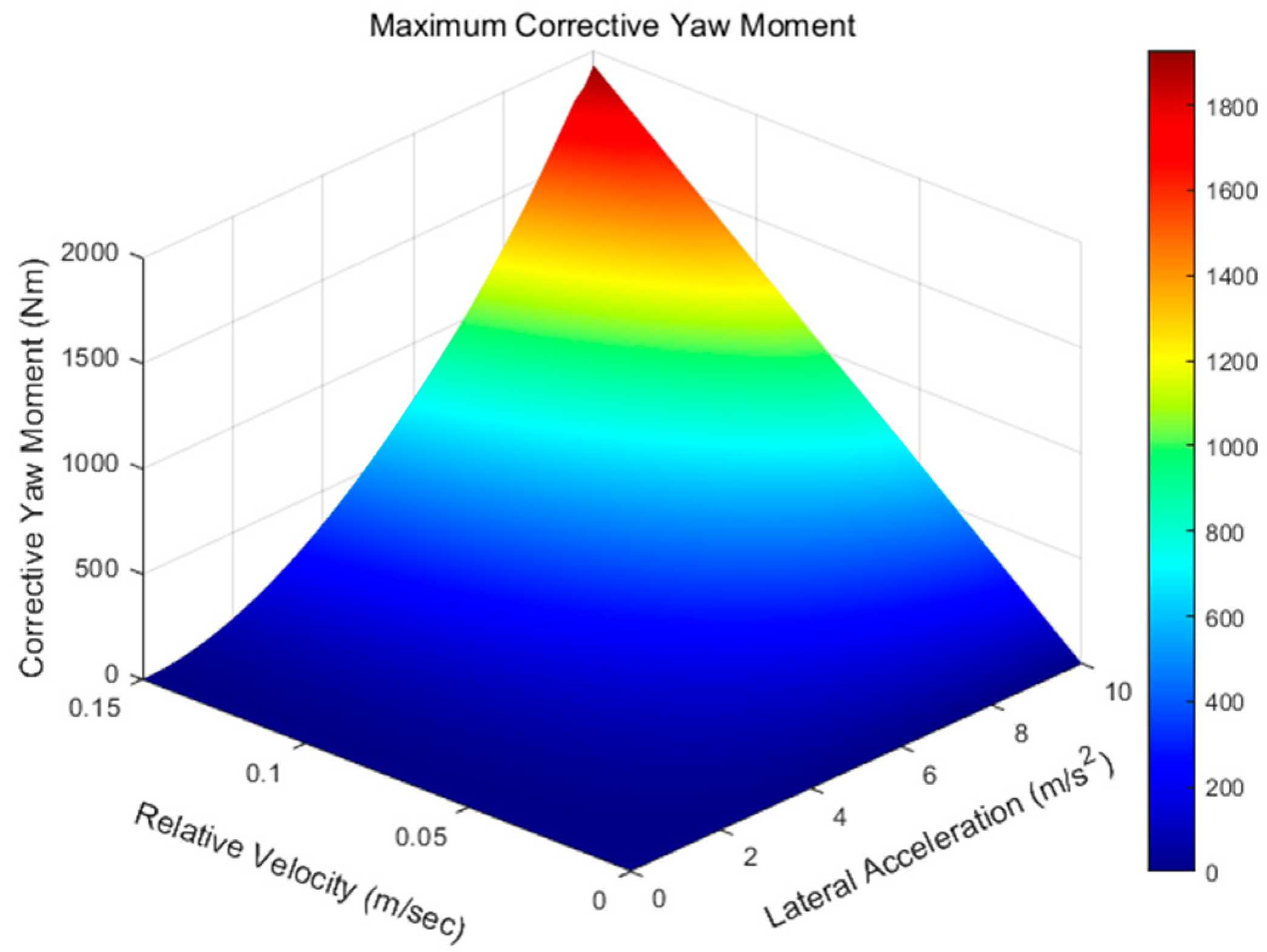

Figure 7 shows that the yaw compensation moment increases as the vehicle’s lateral acceleration and damper relative speed change. The amount of compensation depends on the change in tire vertical force caused by the damper speed change resulting from the vehicle’s roll rate behavior, the tire cornering stiffness, and the basic vehicle specifications, and can be defined as follows (Equation (21)). Here, P represents the basic vehicle specifications. It can be seen that if the vehicle design parameters, such as the damper and tire, are correctly set, the vehicle’s yaw compensation moment can be appropriately generated.

By calculating the lateral acceleration change component of the vehicle using the driver’s input, the roll rate control amount, as described in the previous section, can be weighted to define the compensation yaw moment, thereby configuring the handling controller for the entire vehicle. The control amount is calculated using Equation (22).

(V) represents the front/rear wheel distribution ratio for creating an appropriate yaw moment compensation, and it has a tuning structure that can be adjusted according to the vehicle speed.

Squat control, as shown in

Figure 8a, detects the size and change in the throttle position sensor signal to determine the driver’s intention to decelerate and calculates the control amount. Dive behavior control during deceleration is calculated using the BLS (Brake Light Switch) signal and vehicle speed.

Figure 8b shows a control schematic for controlling the nose-down phenomenon that occurs when the vehicle brakes. The final deceleration is calculated based on the vehicle speed and used as a control decision factor.

4. Vehicle Test Configuration and Environment

To verify the performance of a semi-active suspension on low-friction surfaces, a consistent road surface is required, ensuring a homogeneous coefficient of friction. To achieve this, a handling test was conducted on the Arjeplog Snow Road in Sweden. The test was conducted on a mid-size sedan, with the VDC system and the ECS (Electronically Controlled Suspension) system sharing internal signals via CAN (Controller Area Network) communication. The VDC system is an active safety system that stabilizes the vehicle’s attitude by assessing understeering/oversteering conditions in the vehicle’s yaw behavior. It typically incorporates the functions of an anti-lock braking system (ABS) and a traction control system (TCS). The VDC receives wheel speed signals, throttle position, and BLS information, and the ECS system is configured to output control outputs to the VDC system. This study focused on controlling stability and sensitivity while maintaining ride comfort on low-friction surfaces, with a focus on tuning the control system and measuring its performance.

Figure 9 shows the vehicle configuration and the actual road conditions.

In this vehicle test, a combination of mass-produced VDC sensors (yaw rate, roll rate, and lateral acceleration), a Murata rate gyro, and a Correvit optical velocity sensor was used to precisely measure the vehicle’s yaw, roll, and lateral behavior. All inertial sensors were mounted on a rigid structure near the vehicle’s center of gravity to minimize structural interference. Furthermore, zero-offset calibration was performed before each test session to eliminate temperature and bias variations.

Data acquisition was performed using an in-house developed logging program based on the VDC ECU. CAN signals, including yaw/roll rate, lateral acceleration, wheel speed, steering angle, and damper control current, were recorded at 5 ms (200 Hz) intervals, synchronized. The acquired data was subjected to noise filtering and post-processing using MATLAB R2020 and an in-house signal processing tool.

The detailed specifications of the sensors and data acquisition system employed in this experiment are provided in

Table 1.

Handling Maneuver Test Method

To verify the performance of the semi-active ECS on snowy roads, a 2.5 m-wide double lane change course was created, as shown in

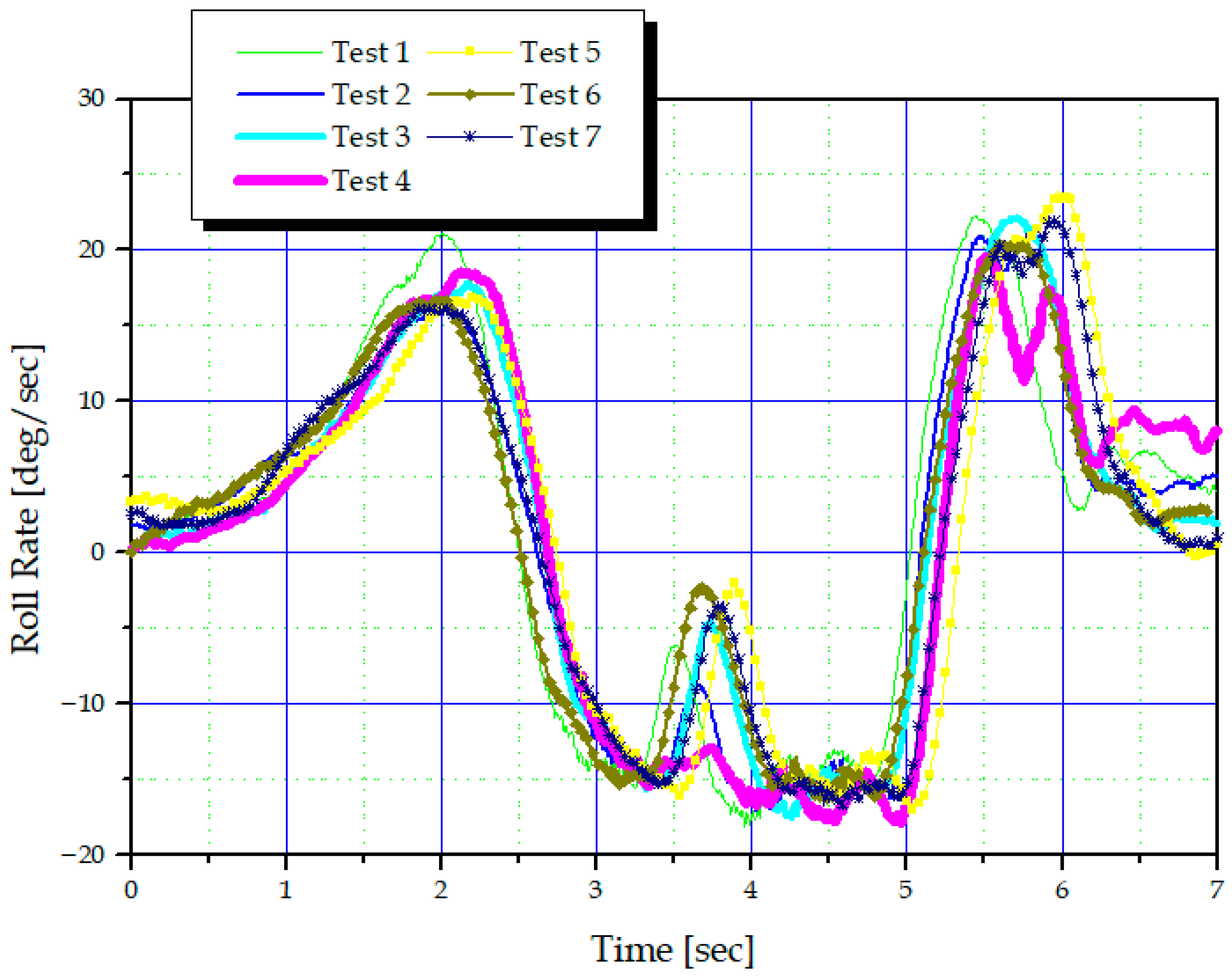

Figure 10, and vehicle responses were measured at a constant speed of 70 km/h. The semi-active handling control tuning results were summarized based on roll rate, yaw rate, and lateral acceleration. To ensure the validity of the measurement results, the measurements were repeated at least three times under identical conditions.

6. Conclusions and Future Works

This study verified the roll-yaw stabilization performance of a semi-active ECS on a real-world vehicle on the Arjeplog low-friction (low-μ) test track in Sweden. Unlike previous studies that primarily focused on improving semi-active ride and handling performance on high-friction (high-μ) road surfaces, this study investigated the practical effectiveness of generating yaw compensation moments using front/rear damping force distributions under low-friction conditions. Furthermore, it confirmed the stable operation of integrated roll-yaw control even under the nonlinear damping characteristics of reverse-type dampers.

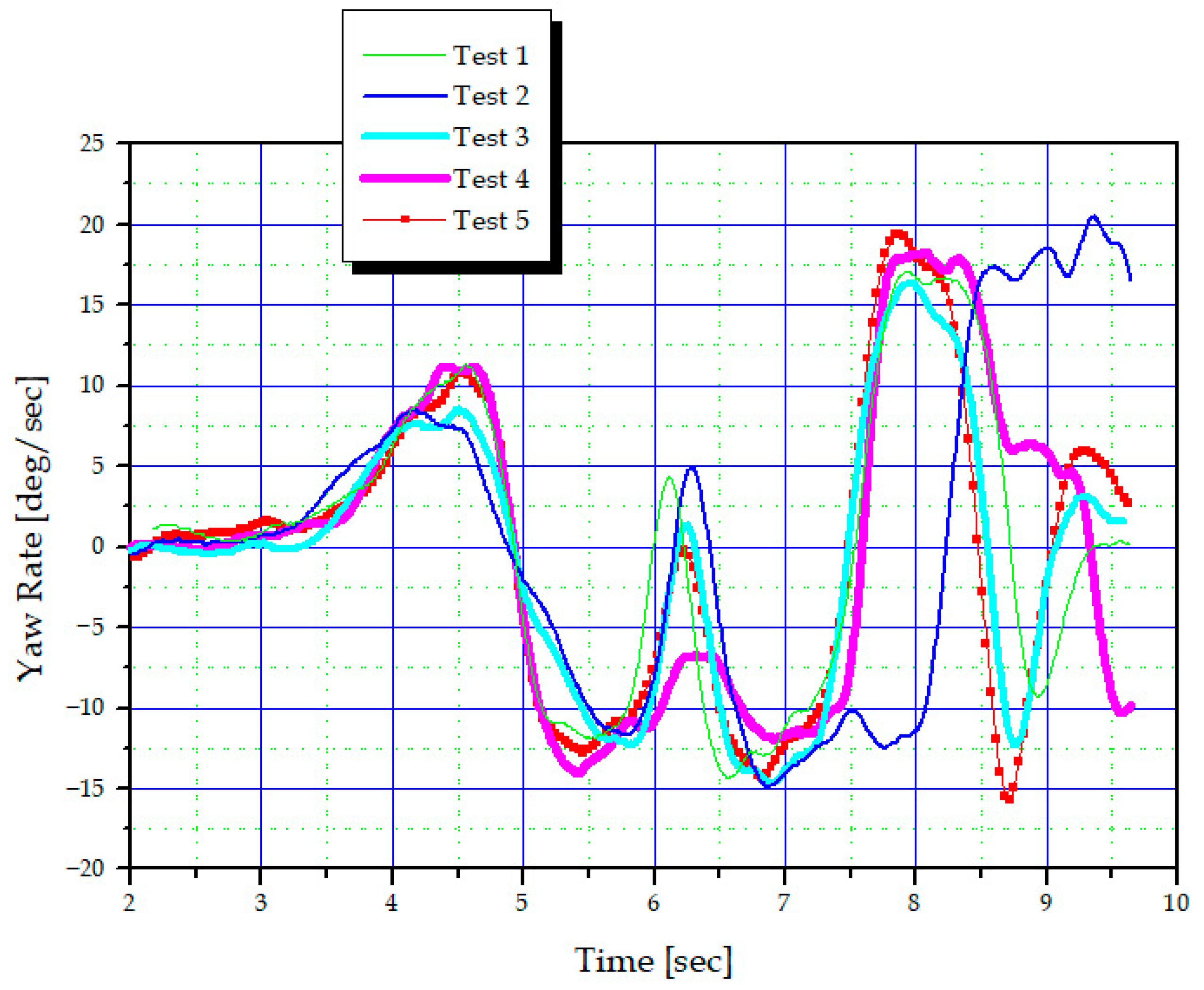

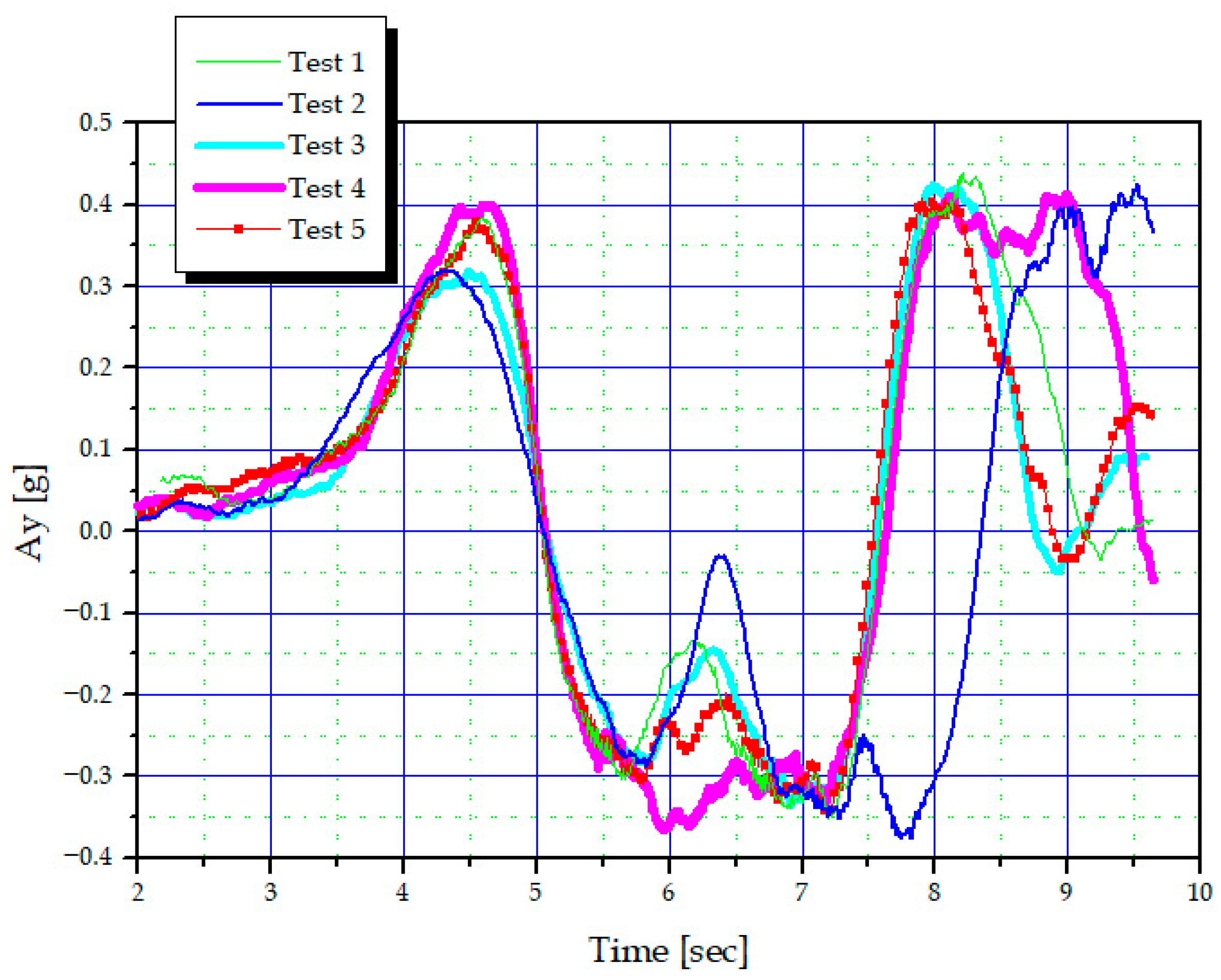

First, the quantitative analysis of integrated roll-yaw control performed in

Section 5.1 showed that while roll-only control exhibited a maximum-minimum yaw rate range of approximately 7 deg/s at the second DLC peak between repeated tests, the proposed integrated roll-yaw control reduced this range to approximately 3 deg/s, demonstrating a 57% reduction in peak yaw rate deviation. Furthermore, the yaw-rate trajectories overlapped almost identically in the post-peak damping region, and the RMS-based repeatability improved approximately twice compared to the roll-only control. Roll-rate also decreased from approximately 8 to 2 in the peak range compared to the roll-only control, resulting in a deviation reduction of about 75%, which confirms that the proposed integrated control provides high steering stability and response reproducibility even under low-friction conditions.

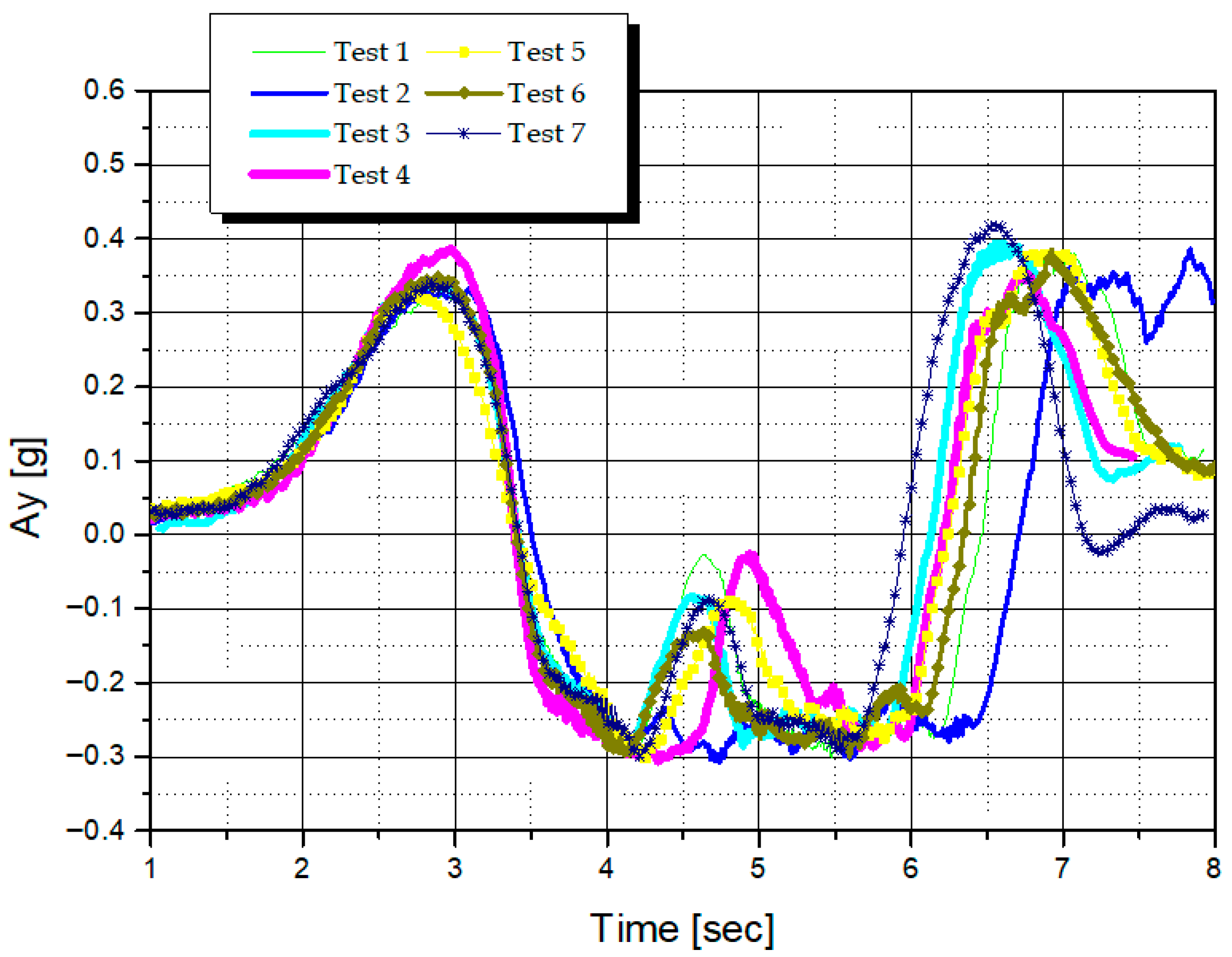

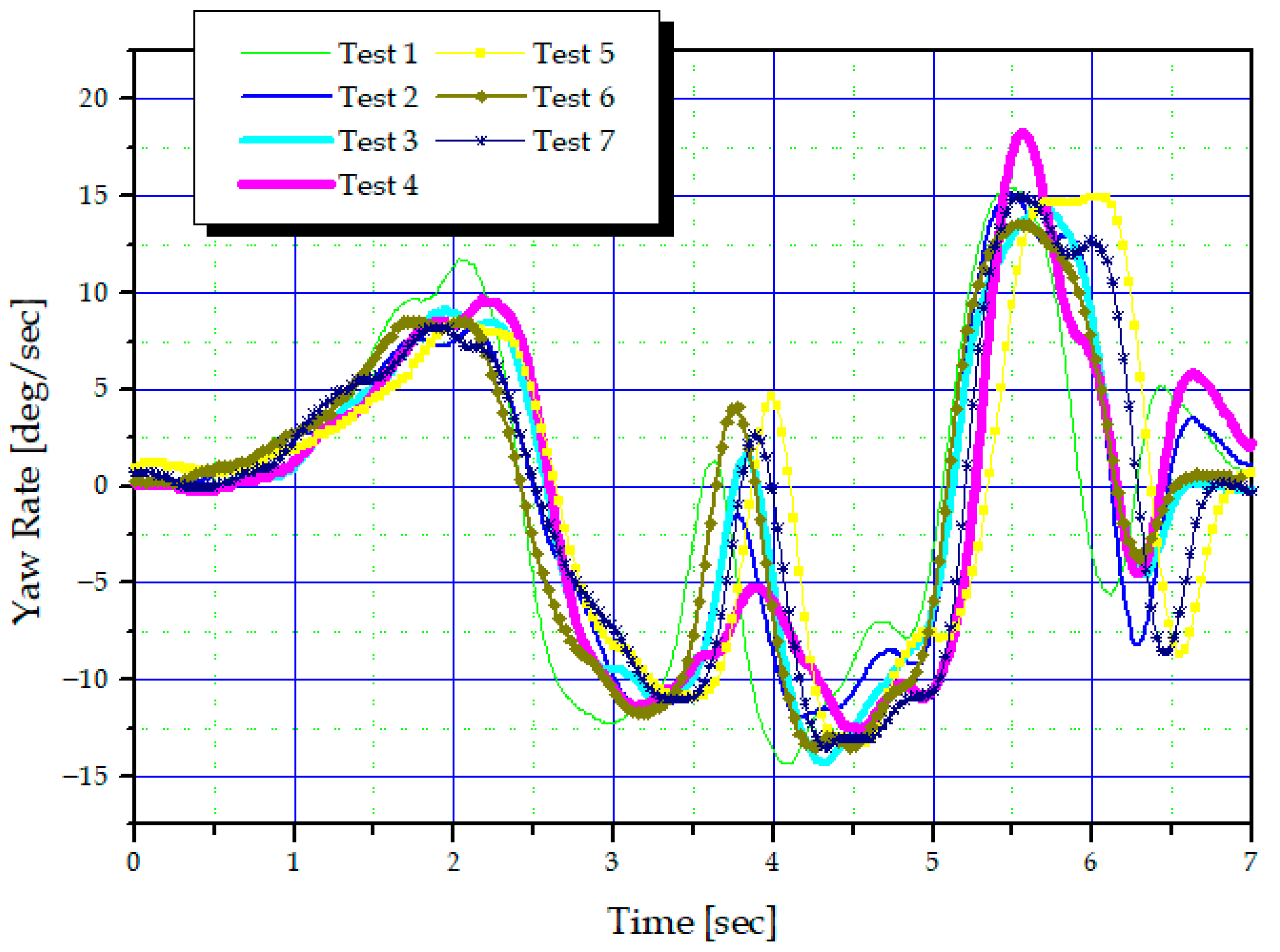

Next, in the comparison with the conventional damper in

Section 5.2, yaw overshoot and increased rear-wheel slip repeatedly occurred under fixed damping conditions, with the test only completing two of six trials. In contrast, when the semi-active ECS was applied, the peak yaw-rate amplitude was reduced by approximately 16.3%, and no course deviation occurred in any of the repeated tests. This result, based on actual vehicle data, demonstrates that the yaw compensation moment, achieved through adjustments to the front/rear damping ratio, effectively stabilizes the vehicle’s lateral and yaw responses. Furthermore, in the VDC cooperative control environment analysis in

Section 5.3, the yaw-rate deviation at the second DLC peak was approximately 7 deg/s under the VDC on, ECS off conditions, but decreased to approximately 4 deg/s with ECS on, indicating a peak deviation reduction of approximately 40–45%. The RMS repeatability also decreased by approximately 50% compared to the ECS off condition. The roll-rate also showed a peak deviation of approximately 6 deg/s under the VDC on, ECS off conditions, but decreased to approximately 4 deg/s with ECS on, indicating a reduction of approximately 30%, and an improvement of 30–40% on the RMS basis. This suggests that the semi-active ECS plays a role in stabilizing the roll–yaw behavior prior to VDC braking-based intervention, thereby improving the temporal consistency and repeatability of the overall chassis response. The key findings and achievements of this study are summarized as follows:

Superior Yaw Stability: Comparative experiments demonstrated that the proposed semi-active control significantly outperforms the conventional damping mode.

Roll-Yaw Integrated Control Effect: Improved steering stability under low-friction conditions. This suppressed excessive vehicle slip and derailment, which were frequently observed in conventional mode and roll control only.

Synergy with VDC: The combination of semi-active suspension and the VDC system resulted in smoother vehicle behavior and high repeatability across multiple tests, proving its practicality for real-world winter driving conditions.

In conclusion, this study provides experimental evidence that a properly tuned semi-active suspension can actively contribute to vehicle safety on low-friction roads, beyond merely improving ride comfort. Future research will expand to encompass expanded validation under various low-μ conditions, the application of an adaptive yaw compensation control structure based on road surface lateral friction coefficient estimation, analysis of the impact of differences in reverse/normal-type damping characteristics on yaw moment generation, and prediction-based cooperative control with ADAS and VDC to enhance overall chassis stability in low-friction environments.