Cloud-Assisted Nonlinear Model Predictive Control with Deep Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Vehicle Path Tracking

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- A DRL-driven model-free cloud-assisted MPC framework is extended based on our previous work [18]. DRL enables the learning of control fusion strategies, thereby bypassing the requirement for exact future cost estimation under disturbances, a crucial capability for complex dynamic environments.

- 2.

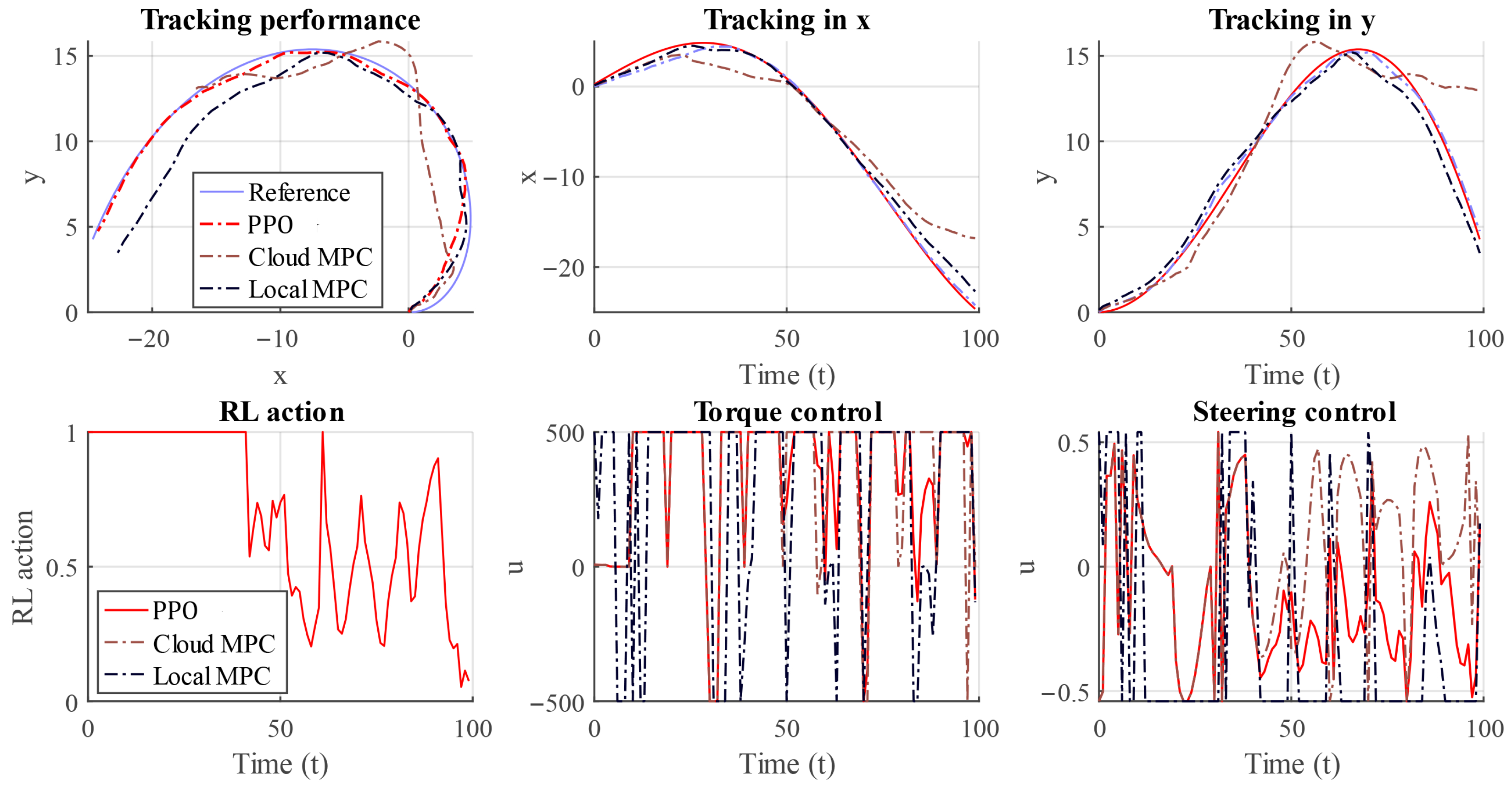

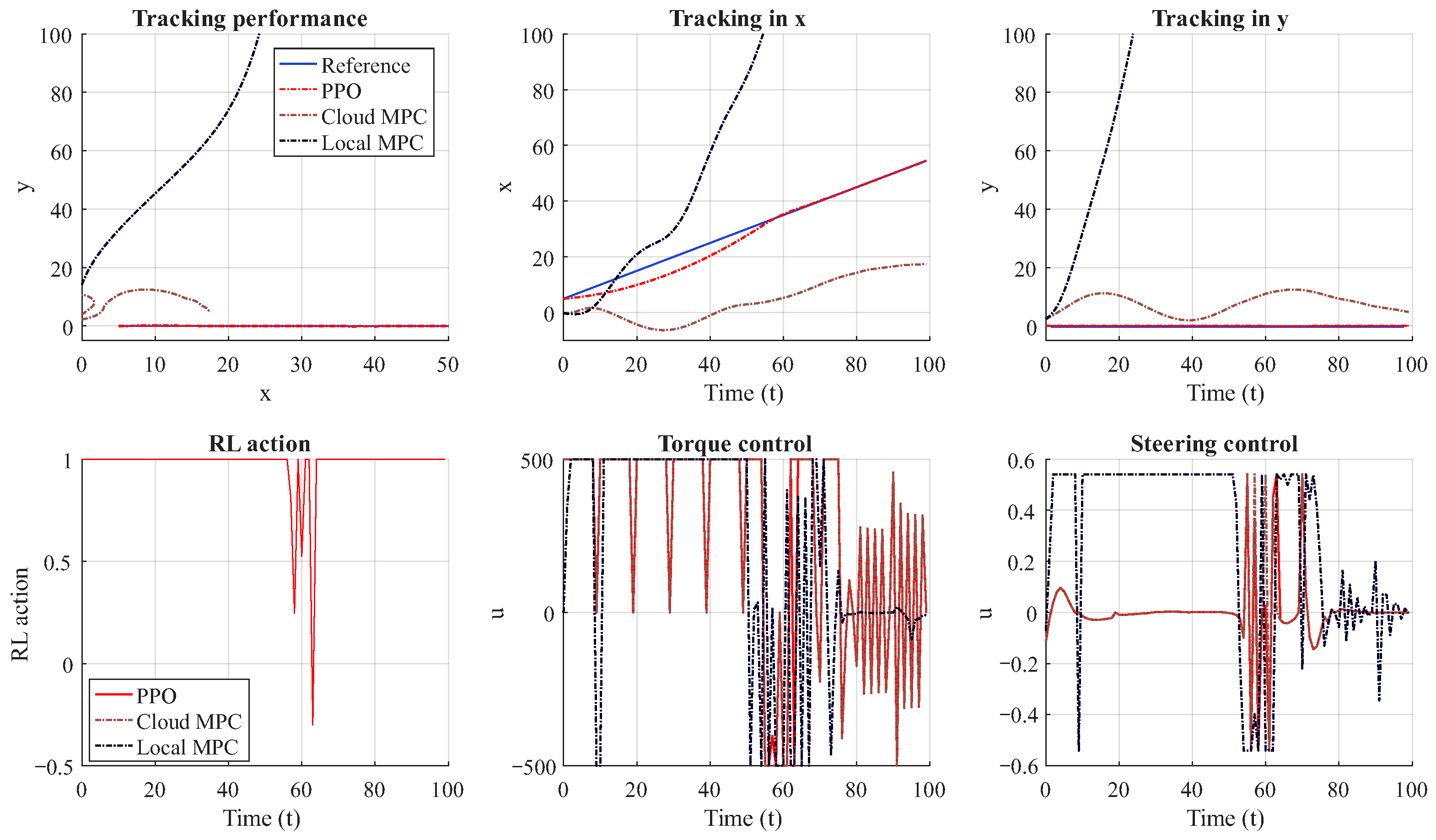

- The DRL-cloud-assisted MPC is validated in the AV path-tracking task. In cloud MPC, a high-fidelity nonlinear vehicle dynamics model is applied that considers the angle of tire slip and axle load transfer, which is commonly neglected in existing MPC-based path tracking research due to the limited computing power on board [9]. The results demonstrate superior performance compared to both cloud-only and local-only baselines, as well as the rule-based method.

- 3.

- The developed cloud-assisted MPC with classical DRL algorithms are well benchmarked and the codes are open-sourced (Codes: https://gitee.com/majortom123/mpc, accessed on 1 January 2025), which is expected to be a valuable resource for future research in the domain of cloud-assisted MPC with DRL and beyond.

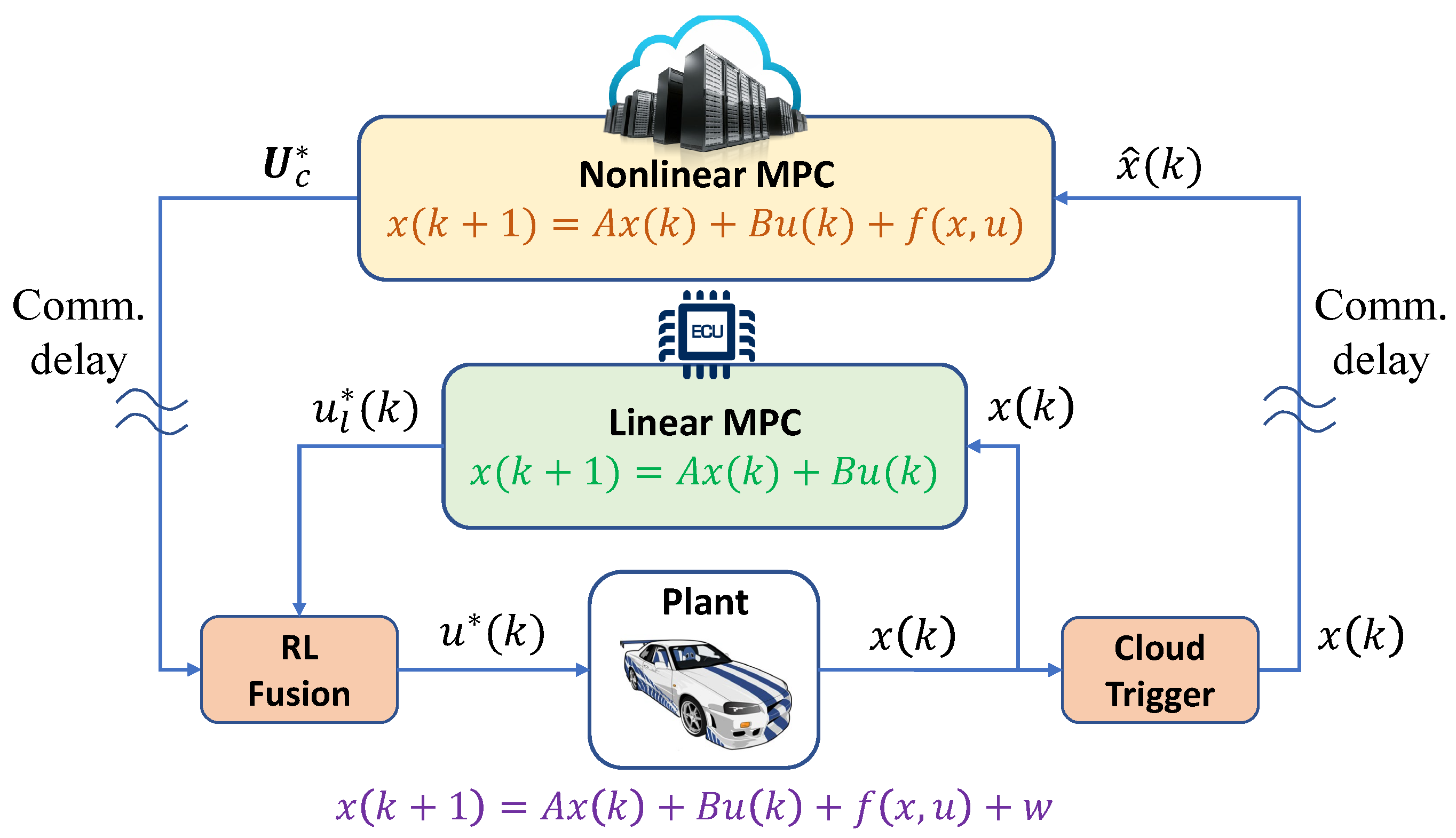

2. Methodology

2.1. Vehicle Dynamics and Path Tracking Problem

2.2. Cloud-Assisted MPC Framework

3. DRL-Based Control Fusion Design

| Algorithm 1 DRL-based Cloud-Assisted MPC. |

| Require: M, T, , , N |

| Ensure: |

| 1: Initialize , |

| 2: for to do |

| 3: Initialize , Z, U, |

| 4: while do |

| 5: Select fusion action based on current state |

| 6: |

| 7: Environment Simulation |

| 8: |

| 9: |

| 10: Local control |

| 11: Fuse control input from the dual controller |

| 12: |

| 13: |

| 14: Apply control and simulate system dynamics |

| 15: |

| 16: Calculate reward |

| 17: |

| 18: Observe next state and store experience |

| 19: |

| 20: Store in |

| 21: Update policy parameters |

| 22: Sample N experiences from and update |

| 23: Move to next time step |

| 24: |

| 25: |

| 26: end while |

| 27: end for |

3.1. Preliminary of DRL

3.2. DRL-Based Cloud-Assisted MPC

- 1.

- Action space : The action generated by the DRL represents the fusion strategy for the DRL-based cloud-assisted MPC, ranging continuously from 0 to 1. This strategy integrates the control signals from both the cloud and local controllers. When , the system solely utilizes the cloud MPC, analogous to a cloud-only approach. Conversely, when it comes to , it employs only the local controller, aligning with the local-only MPC strategy.

- 2.

- State space : The state space is designed to represent the simulation environment to learn a fusion policy and is defined as follows:

- 3.

- Reward function : The design of the reward function plays a critical role in guiding RL agents toward target behaviors. The specific form of the reward function is given in Equation (8), where the term is defined as:where denotes the actual system state (or its current state estimate in the absence of direct measurement), represents the reference trajectory and , and represents the real-time control action, synthesized as , an affine combination of cloud control and local control.

- 4.

- Transition probabilities : As a model-free RL approach, our framework operates without an explicit model of the transition dynamics , which characterizes the robot’s environmental interactions.

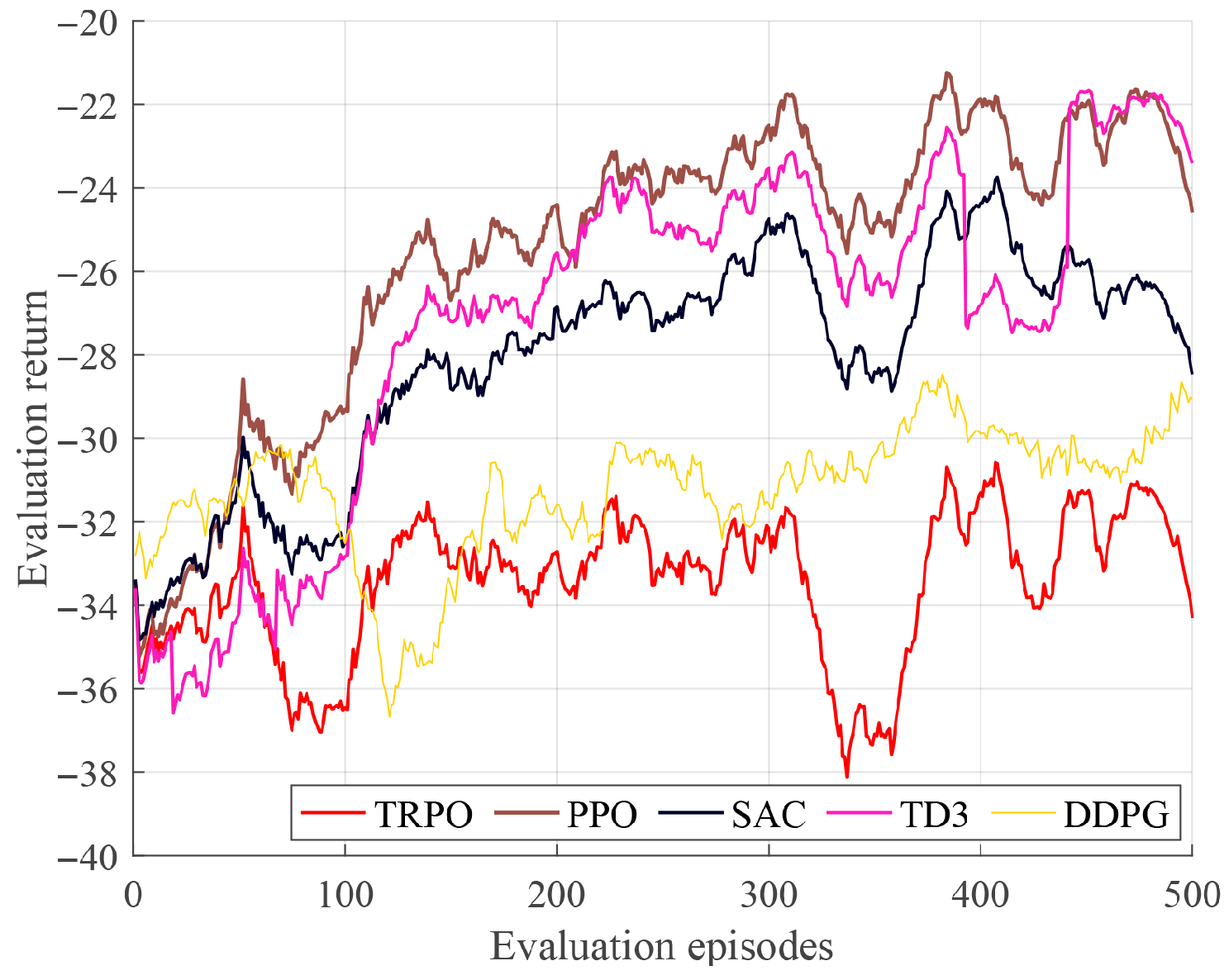

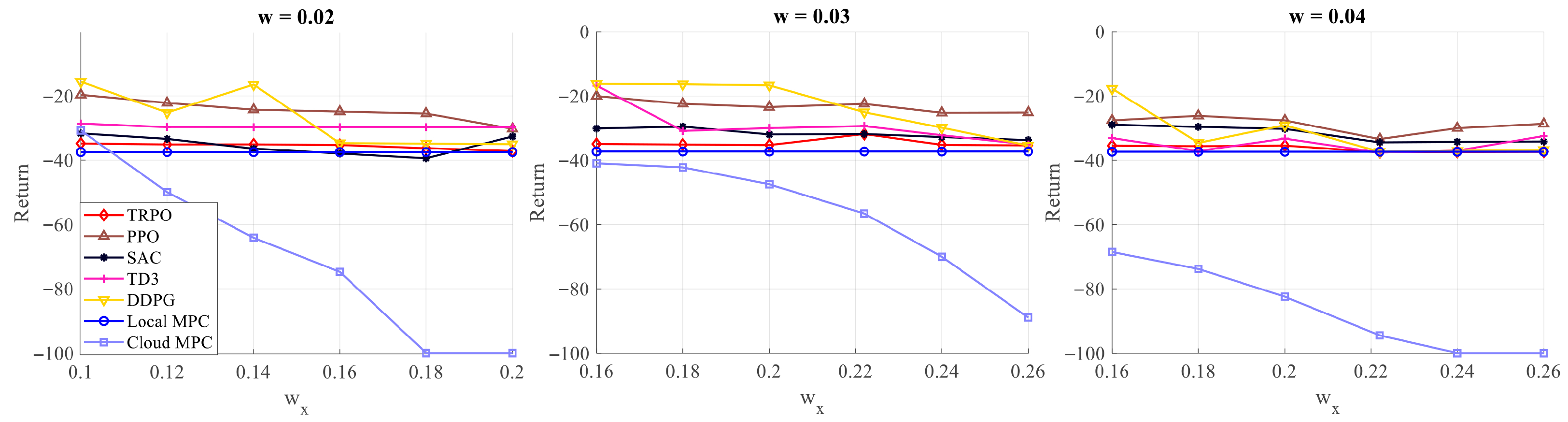

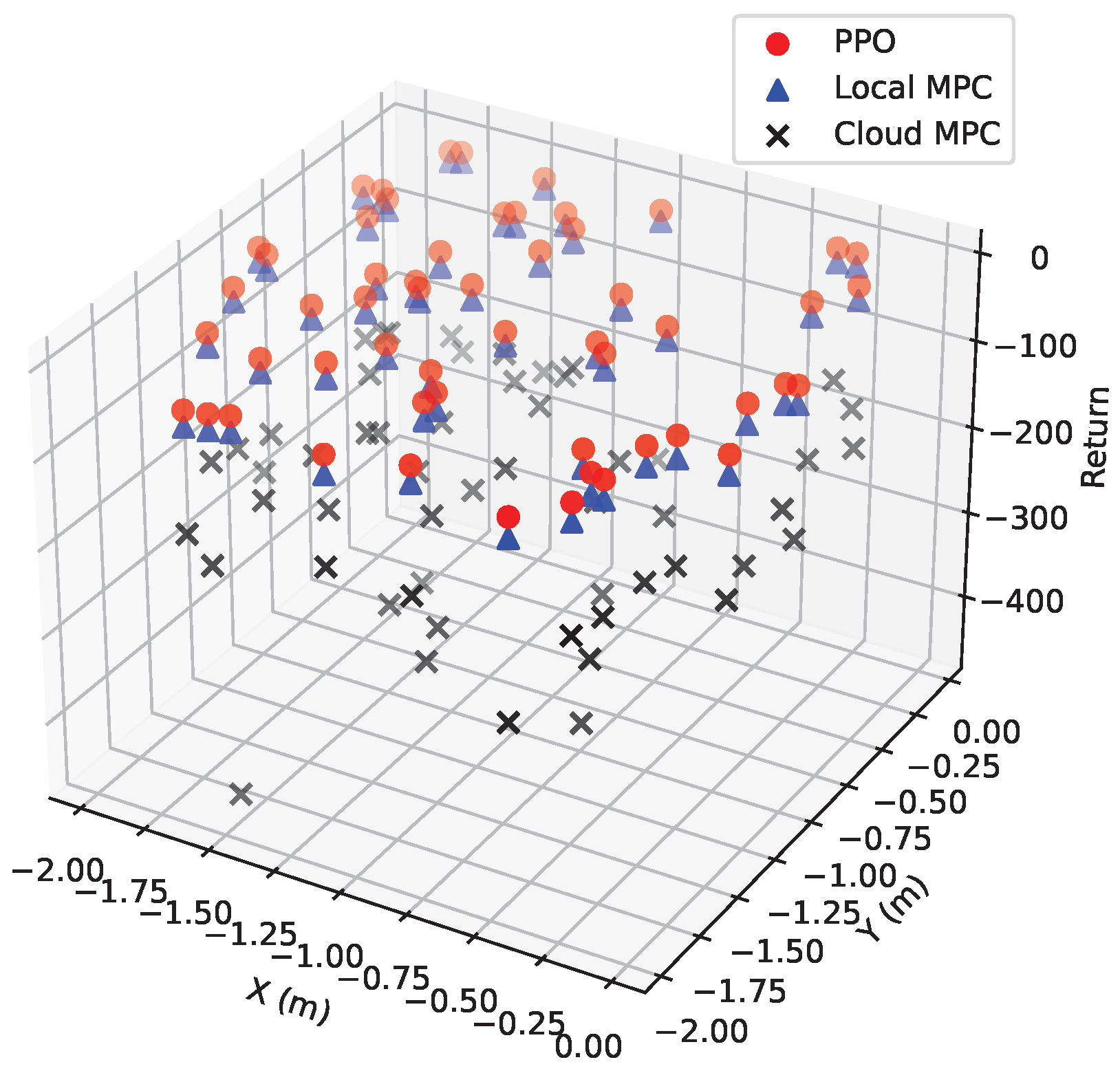

4. Simulation Results

5. Conclusions & Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bagloee, S.A.; Tavana, M.; Asadi, M.; Oliver, T. Autonomous vehicles: Challenges, opportunities, and future implications for transportation policies. J. Mod. Transp. 2016, 24, 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, P.; Wagner, M. Autonomous vehicle safety: An interdisciplinary challenge. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2017, 9, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtsever, E.; Lambert, J.; Carballo, A.; Takeda, K. A survey of autonomous driving: Common practices and emerging technologies. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 58443–58469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Rother, C.; Chen, J. Event-triggered model predictive control for autonomous vehicle path tracking: Validation using carla simulator. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 8, 3547–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, N.H.; Zamzuri, H.; Hudha, K.; Kadir, Z.A. Modelling and control strategies in path tracking control for autonomous ground vehicles: A review of state of the art and challenges. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2017, 86, 225–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Liu, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, T.; Shi, Z.; Zhuang, W. Safety-Critical Lane Change Control of Autonomous Vehicles on Curved Roads Based on Control Barrier Functions. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Automated Vehicle Validation Conference (IAVVC), Austin, TX, USA, 16–18 October 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Meléndez-Useros, M.; Viadero-Monasterio, F.; Jiménez-Salas, M.; López-Boada, M.J. Static Output-Feedback Path-Tracking Controller Tolerant to Steering Actuator Faults for Distributed Driven Electric Vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-bayati, K.Y.; Mahmood, A.; Szabolcsi, R. Robust Path Tracking Control with Lateral Dynamics Optimization: A Focus on Sideslip Reduction and Yaw Rate Stability Using Linear Quadratic Regulator and Genetic Algorithms. Vehicles 2025, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stano, P.; Montanaro, U.; Tavernini, D.; Tufo, M.; Fiengo, G.; Novella, L.; Sorniotti, A. Model predictive path tracking control for automated road vehicles: A review. Annu. Rev. Control 2023, 55, 194–236. [Google Scholar]

- Grüne, L.; Pannek, J.; Grüne, L.; Pannek, J. Nonlinear Model Predictive Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schwenzer, M.; Ay, M.; Bergs, T.; Abel, D. Review on model predictive control: An engineering perspective. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 117, 1327–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, F.; Wang, J.; Li, K. A Bayesian expectation maximization algorithm for state estimation of intelligent vehicles considering data loss and noise uncertainty. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2025, 68, 1220801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givehchi, O.; Trsek, H.; Jasperneite, J. Cloud computing for industrial automation systems—A comprehensive overview. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 18th Conference on Emerging Technologies & Factory Automation (ETFA), Cagliari, Italy, 10–13 September 2013; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Breivold, H.P.; Sandström, K. Internet of things for industrial automation–challenges and technical solutions. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Data Intensive Systems, Sydney, Australia, 11–13 December 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 532–539. [Google Scholar]

- Skarin, P.; Eker, J.; Kihl, M.; Årzén, K.E. An assisting model predictive controller approach to control over the cloud. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.06305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarin, P.; Tärneberg, W.; Årzén, K.E.; Kihl, M. Control-over-the-cloud: A performance study for cloud-native, critical control systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/ACM 13th International Conference on Utility and Cloud Computing (UCC), Leicester, UK, 7–10 December 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, W.; Wuniri, Q.; Du, X.; Xiong, Q.; Huang, T.; Li, K. Cloud control system architectures, technologies and applications on intelligent and connected vehicles: A review. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2021, 34, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhang, K.; Li, Z.; Srivastava, V.; Yin, X. Cloud-assisted nonlinear model predictive control for finite-duration tasks. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2022, 68, 5287–5300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulkumaran, K.; Deisenroth, M.P.; Brundage, M.; Bharath, A.A. Deep reinforcement learning: A brief survey. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2017, 34, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Deep reinforcement learning: An overview. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1701.07274. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, F.; Chen, D.; Chen, J.; Li, Z. Event-triggered model predictive control with deep reinforcement learning for autonomous driving. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 9, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yi, Z. Comparison of event-triggered model predictive control for autonomous vehicle path tracking. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Conference on Control Technology and Applications (CCTA), San Diego, CA, USA, 9–11 August 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 808–813. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yin, G.; Hang, P.; Zhao, J.; Lin, Y.; Huang, C. Fundamental estimation for tire road friction coefficient: A model-based learning framework. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 74, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillicrap, T.P.; Hunt, J.J.; Pritzel, A.; Heess, N.; Erez, T.; Tassa, Y.; Silver, D.; Wierstra, D. Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1509.02971. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, S.; Hoof, H.; Meger, D. Addressing function approximation error in actor-critic methods. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 1587–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Haarnoja, T.; Zhou, A.; Abbeel, P.; Levine, S. Soft actor-critic: Off-policy maximum entropy deep reinforcement learning with a stochastic actor. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 1861–1870. [Google Scholar]

- Schulman, J.; Levine, S.; Abbeel, P.; Jordan, M.; Moritz, P. Trust region policy optimization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Lille, France, 6–11 July 2015; pp. 1889–1897. [Google Scholar]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, P. Soft actor-critic for discrete action settings. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.07207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | [-] | [-] | |||||

| Values | 1500 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 4192 | 0.2159 | −4.5837 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Chen, B.; Wang, Y.; Li, N. Cloud-Assisted Nonlinear Model Predictive Control with Deep Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Vehicle Path Tracking. Actuators 2025, 14, 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120609

Zhang Y, Chen B, Wang Y, Li N. Cloud-Assisted Nonlinear Model Predictive Control with Deep Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Vehicle Path Tracking. Actuators. 2025; 14(12):609. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120609

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yuxuan, Bing Chen, Yan Wang, and Nan Li. 2025. "Cloud-Assisted Nonlinear Model Predictive Control with Deep Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Vehicle Path Tracking" Actuators 14, no. 12: 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120609

APA StyleZhang, Y., Chen, B., Wang, Y., & Li, N. (2025). Cloud-Assisted Nonlinear Model Predictive Control with Deep Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Vehicle Path Tracking. Actuators, 14(12), 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120609