Abstract

This paper focuses on designing an event-triggered dynamic output feedback controller for discrete-time linear systems subject to actuator and sensor constraints as well as external disturbances. A dynamic event-triggered condition with two generalized weighting parameters is introduced to regulate sensor-to-controller communication. By integrating generalized sector conditions, Lyapunov analysis, and linearization techniques, sufficient conditions are derived in terms of linear matrix inequalities, ensuring bounded closed-loop trajectories, prescribed performance, and asymptotic stability in the disturbance-free case. Furthermore, optimization problems are formulated to maximize the event-triggering rate while preserving the desired system performance. Simulation results show that, compared to time-triggered control, the event-triggered control effectively reduces the communication frequency, thereby significantly conserving communication resources. Compared with existing results, this work presents the first event-triggered dynamic output feedback scheme for discrete-time linear systems with dual saturation constraints. The inclusion of generalized weighting parameters and the use of generalized sector conditions allow the design to be carried out within a flexible local framework with reduced conservatism.

1. Introduction

Actuator saturation, inherent in nearly all feedback control systems due to physical limitations, introduces nonlinear behavior that can severely degrade performance and potentially destabilize the system [1,2,3,4,5]. Designing effective controllers for such systems requires explicitly accounting for these saturation constraints during stability analysis and synthesis. Common design approaches are performed within either the global/semi-global framework or the local framework [6,7,8]. For exponentially unstable open-loop systems, controller design is typically conducted within a regional framework. Within this framework, two principal methodologies have been established to address saturation nonlinearities: polytopic model representations [7,9] and modified sector conditions [6,10].

Sensor saturation represents another prevalent nonlinearity in control systems, arising when sensors reach their physical measurement limits. This phenomenon distorts output signals, yielding incomplete or erroneous controller feedback. Similar to actuator saturation, sensor saturation degrades stability margins and can potentially lead to system instability if unaddressed. Over past decades, substantial research efforts have addressed under sensor saturation constraints [11,12,13]. In particular, significant advances in controller synthesis have been achieved in [14,15] through explicit consideration of concurrent actuator and sensor saturations. This co-design approach acknowledges the coupled nature of dual saturation effects and their collective impact on overall system performance and stability.

Networked control systems (NCSs) constitute feedback control loops wherein sensors, controllers, and actuators communicate via a shared digital network, replacing traditional point-to-point connections. This structure offers significant advantages, including reduced wiring complexity, enhanced system flexibility, and simplified maintenance [16,17,18]. However, it introduces inherent challenges such as network-induced delays, data packet dropouts, limited bandwidth, and scheduling constraints [19,20,21,22,23]. To efficiently manage communication resource utilization while preserving desired system performance, event-triggered mechanisms (ETMs) have been developed, under which sensor data transmissions occur only when specific triggering conditions are violated, significantly reducing network resource usage [24,25,26,27]. Consequently, substantial analysis and synthesis frameworks have been sufficiently established for NCSs employing ETMs [28,29,30,31,32].

Over the past decade, significant advances have emerged for NCSs incorporating saturation constraints [33,34,35], with recent studies increasingly employed ETMs to address these challenges [36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. For instance, a static ETM has been utilized to solve the dynamic output feedback control problem for discrete-time LPV systems with actuator constraints [41]. The control problem has been examined for singularly perturbed systems subject to time delays and sensor saturations under a dynamic ETM [39]. Notably, concurrent sensor and actuator saturations have been tackled in designing the event-triggered dynamic output-feedback controller [43]. However, two limitations persist in existing research: (1) current dual-saturation treatments in [43] rely on non-strict inequalities rather than rigorous generalized sector-bound conditions; and (2) the results in [43] are exclusively confined to continuous-time domains, leaving discrete-time formulations underdeveloped.

To bridge the aforementioned gaps, this paper develops a novel event-triggered control framework for discrete-time systems simultaneously subject to actuator saturation, sensor saturation, and external disturbances. The main contributions are summarized as follows. (1) A unified co-design procedure is established for the dynamic output-feedback controller and the ETM. Furthermore, optimization problems are formulated to maximize the event-triggering rate (ETR), thereby explicitly balancing communication efficiency with prescribed control performance. (2) Unlike the approach in [39], two generalized weighting parameters are introduced in the event-triggering condition (ETC), which allows the derivation of LMI conditions without resorting to conservative bounding inequalities, thus reducing design conservatism. (3) In contrast to the continuous-time method in [43] that relies on non-strict inequalities, a discrete-time formulation is developed. It rigorously handles actuator and sensor saturations using generalized sector-bound conditions within a local framework, offering a more systematic and less conservative treatment for discrete-time NCSs.

Notation. : n-dimensional Euclidean space; : the symmetric and positive definite (positive semi-definite) matrix; I: the identity matrix of suitable dimension.

2. Problem Formulation

Consider the discrete-time linear system

where is the system state, is the control input, is the measurement output, is the controlled output, is the disturbance input, A, B, , C and are known constant matrices. The functions and represent actuator and sensor constraints, respectively, where

Here, and denote the saturation levels.

In addition, the disturbance is assumed to satisfy

In this paper, output signals are assumed to be transmitted through communication networks. To conserve communication resources, the ETM is employed. The triggering instants are denoted by , determined by the following ETC:

where , is a given scalar, , are two matrices to be designed. The variable in (3) evolves according to the dynamic equation

with initial condition and parameter .

Remark 1.

The triggering instants are determined by the ETC (3) together with the Equation (4). The weighting parameters and in (3) and (4) can be obtained directly by solving the subsequent LMI-based optimization problems for given scalars and .

This paper focuses on designing an event-triggered dynamic output feedback controller with an anti-windup term:

where is the controller state, and , , , , are gain matrices.

Define the augmented state vector where , and introduce the following nonlinear terms:

From (1) and (5), the closed-loop system is then given by

where

Here, the initial conditions of the system (6) are denoted by .

To address the nonlinear terms and in the system (6), we employ the modified sector conditions [6,10]. This requires the following two constraints:

where , , with and being and gain matrices, respectively. Then, for any diagonal matrix and diagonal matrix , the following modified sector conditions hold [10]:

The main objectives of this paper are to design the event-triggered dynamic output feedback controller (5) that ensures the closed-loop system (6) exhibits: (1) bounded system states for all admissible initial conditions and disturbances satisfying (2); (2) satisfied performance requirement

where denotes the Lyapunov function; (3) asymptotic stability in the absence of external disturbances ().

3. Main Results

To analyze the stability of the system (6), we consider the Lyapunov function

Theorem 1.

Given scalars and , suppose there exist matrix , matrix , matrix , matrices , , diagonal matrix , diagonal matrix , and scalars , , with , such that

where and are the i-th row of the matrix and j-th row of the matrix , respectively, and

with

Then: (1) The closed-loop system (6) has bounded trajectories for all satisfying and all disturbances satisfying (2); (2) The performance constraint (11) holds; (3) In the absence of disturbances, the asymptotic stability of system (6) is guaranteed for all satisfying .

Proof.

Denoting , and using Equations (4) and (6), inequalities (9) and (10), we obtain

where , and , , , are defined in Theorem 1.

Applying the Schur complement to (13) yields

Moreover, from (16), we have

Summing both sides of (18) from 0 to gives

Similarly, the Schur complement applied to (14) and (15) leads to the matrix inequalities

For all with and all satisfying (2), we derive from (12) and (19)–(21) that

Therefore, the constraints (7) and (8) are guaranteed by (22) and (23). Furthermore, (12) and (19) imply , establishing bounded trajectories for the system (6). Taking in (19) and noting verifies the performance requirement (11). For all satisfying in the disturbance-free case, the constraints (7) and (8) remain satisfied. Furthermore, the asymptotic stability of the closed-loop system (6) follows from in (18). □

Next, we formulate the control design using LMIs. To facilitate this, we partition the matrices P and as follows:

where X, Y, M and N are matrices of compatible dimensions.

From the fact , we obtain the relation

Then, define the matrix , and partition and as and , respectively. Moreover, introduce new following matrix variables:

Theorem 2.

Given scalars , , and diagonal matrix , suppose there exist matrices , , matrices , , matrices , , matrices , , diagonal matrix , matrix , matrix , matrix , matrix , matrix , and scalars , , with , such that the following LMIs hold:

where , are the i-th rows of , , respectively, while , are the j-th rows of , , and

with

Then the conclusions of Theorem 1 hold. Moreover, the gain matrices of the controller (5) are given by

Proof.

Pre-and post-multiplying (13) by and its transpose yields

where

Using (25) and (26a)–(26e), it is seen that

Therefore, the matrix inequality (30) is equivalent to (27).

Similarly, pre-and post-multiplying (14) and (15) by and its transpose gives

Furthermore, we observe that (31) and (32) are equivalent to LMIs (28) and (29), respectively.

If the LMI (27) holds, it is seen that

Applying the Schur complement to (33) yields the equivalent condition . This implies , confirming that is nonsingular. We can then compute the matrices M and N satisfying (25) via singular value decomposition. Finally, the controller gain matrices are recovered by solving the Equations (26a)–(26c). □

In this paper, Theorems 1 and 2 are established within a local framework. When and , the sector conditions (9) and (10) reduce to global sector conditions. This yields the following control design criterion for the global framework.

Corollary 1.

Given scalar and diagonal matrix , suppose there exist matrices , , matrices , , diagonal matrix , matrix , matrix , matrix , matrix , matrix , and scalar , such that the following LMIs are satisfied:

where , , , are given in Theorem 2, and

Then, (1) The performance constraint (11) is satisfied; (2) In the absence of disturbances, the system (6) is globally asymptotically stable. Moreover, the controller gain matrices can be computed according to Theorem 2.

Remark 2.

Note that the matrix must be preset in Theorem 2 and Corollary 1. Otherwise, the coupled effects of actuator and sensor saturations render the conditions non-LMIs. For low-dimensional matrix , the linear search can be utilized to optimize system performance levels. For high-dimensional cases, iterative algorithms could be employed to achieve desirable performance.

Finally, we address the optimization problem in the absence of disturbances. For this scenario, the disturbance-related rows and columns can be removed from the LMI (27). Note that the initial conditions satisfy . Without loss of generality, we set . In addition, we assume that the initial conditions lie within the ellipsoid

Here, we specifically consider the case . In this case,

Correspondingly, the initial conditions belong to the set

By minimizing the trace of X, one can obtain the optimized estimate of admissible initial conditions. However, this may lead to an extremely high ETR, rendering the ETM ineffective. Following [8], we select the reference set

ensuring for a given . This inclusion is guaranteed by

We observe that a “large” and “small” typically correspond to the low ETR [40,41]. Recalling that , we can formulate the following ETR-oriented optimization problem over the set :

Remark 3.

Following [39], one may set and , where is a given scalar. For a fixed , the parameter α can be optimized to maximize the admissible set . However, this formulation results in the simultaneous presence of Ω and in the derived condition. To resolve this issue, this paper adopts independent generalized weighting parameters and . This design avoids the coexistence problem altogether, thereby enabling the direct derivation of LMI conditions without resorting to conservative bounding inequalities. Finally, we note that the parameter α can be efficiently optimized via a linear search.

For the disturbance case, we consider zero initial conditions where in (28) and (29) can be replaced by . Minimizing yields the maximum disturbance tolerance level . Given , we can obtain the minimum performance level . Note that the minimum typically results in extremely high ETR. Hence, for a given , we formulate the optimization problem about the ETR

Remark 4.

Over the past decade, serval significant advances have emerged for NCSs subject to saturation constraints under ETMs [37,39,40,41,42]. Despite this progress, concurrent sensor and actuator saturations remain largely overlooked, with [43] representing a notable exception. However, the dual-saturation treatment in [43] relies on non-strict inequalities rather than rigorous generalized sector-bound conditions. Furthermore, its results remain confined exclusively to continuous-time domains. Addressing these gaps, this paper develops event-triggered control for discrete-time NCSs simultaneously subject to actuator and sensor saturations. Crucially, unlike [43], our approach employs sector-bound conditions within a local framework to establish the proposed results.

4. Numerical Examples

Example 1.

Consider the discrete-time system (1) with parameters

We first consider the disturbance-free case with . Selecting the parameters , , , , , and solving the optimization problem Prob. 1, we obtain the following controller gain matrices and triggering parameters:

Additionally, we have the matrix X associated with the set :

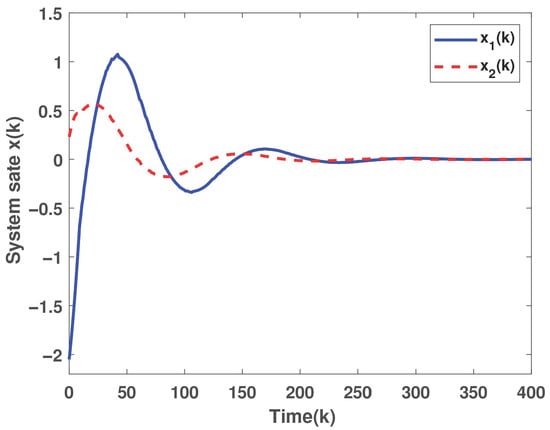

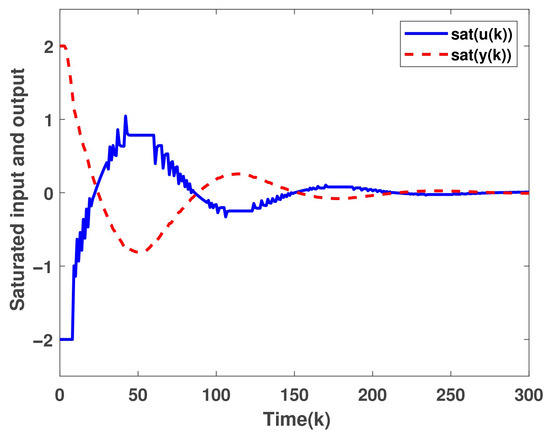

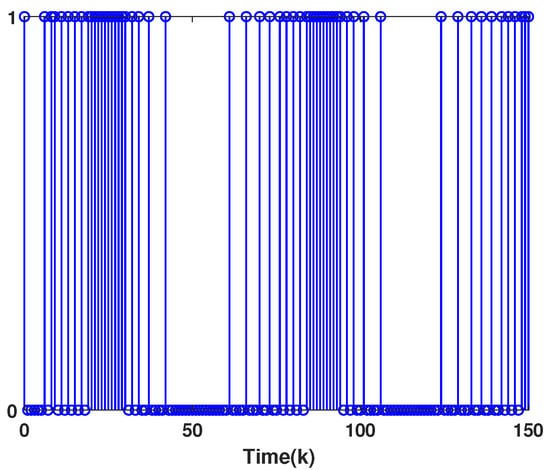

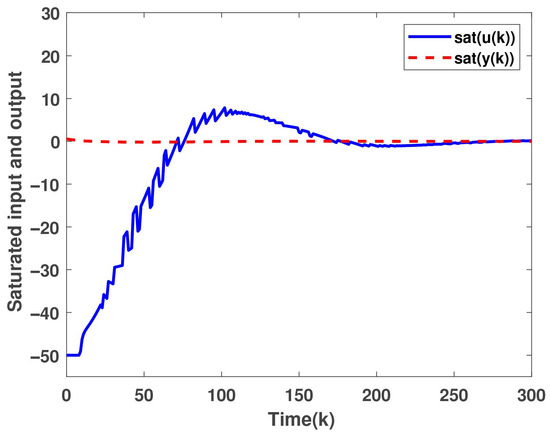

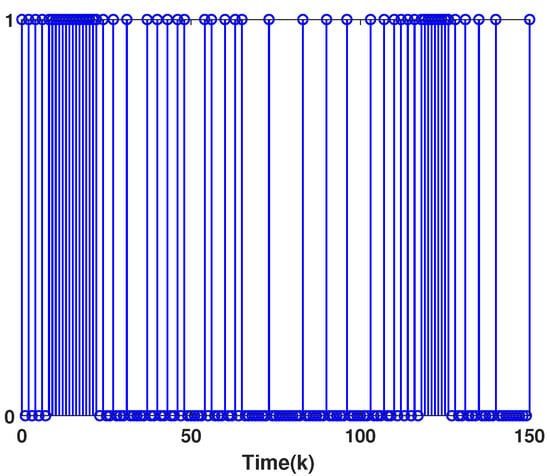

Using the derived parameters with , we simulate the closed-loop system’s state trajectory, saturated control and output signals, and the event-triggering instants. Figure 1 shows the effective stabilization of the inherently unstable system. Figure 2 reveals simultaneous actuator and sensor saturations during transients, explicitly capturing constrained dynamics. Figure 3 confirms the ETM’s efficacy in reducing network resource consumption through condition-based data transmission.

Figure 1.

State trajectory of the closed-loop system.

Figure 2.

Saturated control input and measurement output.

Figure 3.

Triggering instants (1 → triggered, 0 → no triggered).

In Table 1, we list the event-triggering numbers and corresponding rates for different over the time interval . In the simulation, one sets . As shown in the table, the number and the ETR are significantly reduced under the ETM-based design. Noting that the parameter relates to the size of the admissible set of initial conditions, it can be observed that a larger admissible set generally leads to a higher ETR.

Table 1.

Numbers and ETRs for different .

Next, we address the scenario involving disturbances. By selecting parameters , , , and solving the optimization problem for , we obtain . Then, choosing solving the optimization problem for yields . However, directly implementing these and values would render the ETM ineffective. To optimize the ETR, we set (where ) and solve Prob. 2, obtaining

Simulation using these parameters demonstrates that only 51 data packets are released over the interval , confirming the ETM’s effectiveness in conserving network resources. In the simulation, is set as with for .

Example 2.

The state-space representation of an inverted pendulum is given by [44]

Let the parameters be , , , , with a sampling time of . The discretized model of the system can then be expressed as [44]

The system measurement output is . Furthermore, it is assumed that the system is subject to actuator and sensor saturations with and .

Let , , , , , and solve Prob. 1 to obtain

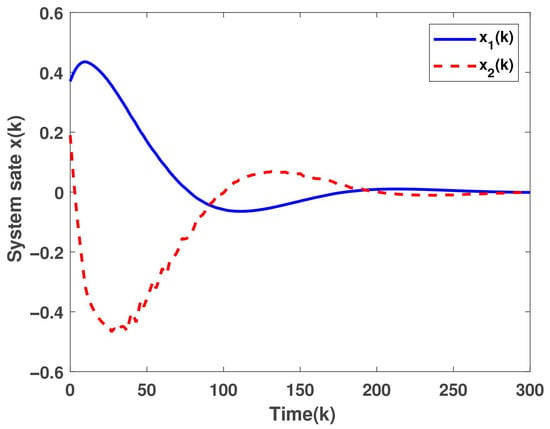

Using the above parameters with , we plot the closed-loop system’s state trajectory, saturated control input and measurement output, as well as data-triggering instants. Figure 4 confirms that closed-loop stabilization is successfully achieved. Figure 5 shows that the actuator experiences saturation during the initial period. Finally, Figure 6 demonstrates that the ETM effectively reduces the number of data transmissions.

Figure 4.

State trajectory of the closed-loop system.

Figure 5.

Saturated control input and measurement output.

Figure 6.

Triggering instants (1 → triggered, 0 → no triggered).

5. Conclusions

This paper has investigated the co-design of an event-triggered dynamic output feedback controller for discrete-time linear systems under dual saturation constraints. A dynamic ETM incorporating generalized weighting parameters is proposed, and sufficient LMI-based conditions are established using a Lyapunov approach combined with generalized sector conditions. Convex optimization problems are further formulated to maximize the ETR under guaranteed closed-loop performance. Numerical simulations demonstrate that the proposed scheme effectively reduces communication frequency while preserving desirable system performance. The developed framework offers a practical design tool for NCSs operating under bandwidth limitations and physical saturation constraints, with direct applications in self-balancing robotic platforms such as two-wheeled autonomous vehicles and legged robots. Future research focus on: (1) extending the approach to time-delay systems and multi-agent systems [18,26,32]; (2) incorporating actuator rate constraints alongside amplitude saturation [3]; and (3) developing adaptive and neural network-based strategies for nonlinear systems with unknown parameters [5,45].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C.; methodology, J.J. (Jinze Jia) and Y.C.; software, L.L.; validation, J.J. (Jishen Jia) and L.L.; formal analysis, J.J. (Jinze Jia) and Y.C.; investigation, J.J. (Jishen Jia) and R.D.; writing—original draft preparation, J.J. (Jinze Jia); writing—review and editing, J.J. (Jishen Jia), Y.C., L.L. and R.D.; supervision, J.J. (Jishen Jia); funding acquisition, Y.C., J.J. (Jishen Jia) and R.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62273132), the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province of China (No. 242300421052), the Soft Science Research Program Project of Xinxiang City of China (No. RKX2020008), and the Key Scientific Research Project of Higher Education Institution in Henan Province of China (No. 23A120002).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, H.; Zhou, P.; Yang, R.; Chen, Y. Trajectory tracking control by PCH method for AUVs with input saturations. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2025, 56, 3512–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Sun, W. Predefined time fuzzy adaptive control of switched fractional-order nonlinear systems with input saturation. Int. J. Netw. Dyn. Intell. 2023, 2, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Qin, J.; Shi, Y.; Zheng, W.X. Auxiliary fault tolerant control with actuator amplitude saturation and limited rate. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2017, 48, 1816–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Xie, M.; Zhang, J.; Ming, Z.; Gao, Z. Integral reinforcement learning-based stochastic guaranteed cost control for time-varying systems with asymmetric saturation actuators. Actuators 2025, 14, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xiang, Z. Finite-time robust adaptive simultaneous stabilisation of nonlinear time-delay systems with actuator saturation. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2024, 55, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarbouriech, S.; Garcia, G.; Gomes da Silva, J.-M., Jr.; Queinnec, I. Stability and Stabilization of Linear Systems with Saturating Actuators; Springer: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Lin, Z.; Duan, G. A parametric Lyapunov equation approach to the design of low gain feedback. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2008, 53, 1548–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B. Analysis and design of discrete-time linear systems with nested actuator saturations. Syst. Control Lett. 2013, 62, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Z. Local stabilization for discrete-time systems with distributed state delay and fast-varying input delay under actuator saturations. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2021, 66, 1337–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shen, B.; Han, Q.-L. Local stabilization for multiple input-delay systems subject to saturating actuators: The continuous-time case. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2022, 67, 3090–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Hou, Z.; Yu, Q.; Yang, Y. Quantized data driven iterative learning control for a class of nonlinear systems with sensor saturation. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2020, 50, 5119–5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.C.; Tarbouriech, S. Anti-windup compensation for systems with sensor saturation: A study of architecture and structure. Int. J. Control 2009, 82, 1253–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Li, Y. Set-membership filtering for systems with sensor saturation. Automatica 2009, 45, 1896–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, G.; Tarbouriech, S.; Gomes da Silva, J.M., Jr.; Eckhard, D. Finite L2 gain and internal stabilisation of linear systems subject to actuator and sensor saturations. IET Control Theory Appl. 2009, 3, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ho, D.W.C.; Dong, H.; Gao, H. Robust H∞ finite-horizon control for a Class of stochastic nonlinear time-varying systems subject to sensor and actuator saturations. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 2010, 55, 1716–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hespanha, J.P.; Naghshtabrizi, P.; Xu, Y. A survey of recent results in networked control systems. Proc. IEEE 2007, 95, 138–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Guo, G. Control and communication scheduling co-design for networked control systems: A survey. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2023, 54, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi, S.P.; Werner, S.; Huang, Y.-F.; Gupta, V. Distributed algebraic Riccati equations in multi-agent systems. In Proceedings of the 2022 European Control Conference, London, UK, 12–15 July 2022; pp. 1810–1817. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, Y. Synchronization control for delayed neural networks under Round-Robin protocol and input saturations. Neurocomputing 2025, 645, 130474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Wang, Z.; Han, Q.-L.; Wei, G. Neural-network-based output-feedback control under Round-Robin scheduling protocols. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2019, 49, 2372–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Ma, L.; Zhao, C.; Liu, Q. State estimation in networked control systems with a real-time transport protocol. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 2024, 12, 2347885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Gao, M.; Sheng, L. Fault-tolerant formation consensus control for time-varying multi-agent systems with stochastic communication protocol. Int. J. Netw. Dyn. Intell. 2024, 3, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ma, L.; Rui, Q.; Gao, C. A survey on privacy-preserving control and filtering of networked control systems. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2024, 55, 2269–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, A. Dynamic triggering mechanisms for event-triggered control. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2015, 60, 1992–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Li, F. A survey on recent advances in event-triggered communication and control. Inform. Sci. 2018, 457, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, C.; Ma, L.; Xu, S. Distributed fixed-time leader-following consensus for multi-agent systems: An event-triggered mechanism. Actuators 2024, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, D.; Tian, E.; Han, Q.-L. A delay system method for designing event-triggered controllers of networked control systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2013, 58, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Li, J.; Song, Y.; Yang, F. Event-based recursive filtering for nonlinear bias-corrupted systems with amplify-and-forward relays. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 2024, 12, 2332419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zeng, P.; Deng, F.; Wu, Z.-H.; Li, M. Event-triggered L2-L∞ control for discrete-time Markov jump systems with DoS attacks and exogenous disturbance. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2024, 55, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Wu, Y.; Shen, B. Novel adaptive memory event-triggered-based fuzzy robust control for nonlinear networked systems via the differential evolution algorithm. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2024, 11, 1836–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Ma, L.; Yang, J. Event-triggered regional stabilization for T-S fuzzy systems subject to communication delays and actuator saturations. J. Franklin. Inst. 2024, 361, 106653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Tan, H. Dynamic event-triggered state estimation for discrete-time delayed switched neural networks with constrained bit rate. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 2024, 12, 2334304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, Z.; Yang, X. Anti-windup design for networked time-delay systems subject to saturating actuators under round-robin protocol. Appl. Math. Comput. 2025, 499, 129413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Pan, F. Fault detection for nonlinear networked control systems with sensor saturation and random faults. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 92541–92551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Xia, Y.; Yuan, H.; Yan, J. Quantized stabilization of networked control systems with actuator saturation. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2016, 26, 3595–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Hu, J.; Lin, H. Dynamic event-triggered regional synchronization for discrete-time delayed dynamical networks: Dealing with saturating actuators. Neurocomputing 2025, 653, 131179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Yang, G.-H. Event-triggered non-fragile control for linear systems with actuator saturation and disturbances. Inform. Sci. 2018, 429, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Chen, Y.; Jia, J.; Zhao, K.; Jia, J. Event-triggered anti-windup strategy for time-delay systems subject to saturating actuators. AIMS Math. 2024, 9, 27721–27738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Wang, Z.; Cai, C.; Alsaadi, F.E. A dynamic event-triggered approach to H∞ control for discrete-time singularly perturbed systems with time-delays and sensor saturations. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2020, 51, 6614–6625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, L.G.; Groff, L.B.; Gomes da Silva, J.M., Jr. Event-triggered state-feedback control for continuous-time plants subject to input saturation. J. Control Autom. Elec. Syst. 2016, 27, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, C.D.; Tarbouriech, S.; Leite, V.J.S.; Castelan, E.B. Co-design of an event-triggered dynamic output feedback controller for discrete-time LPV systems with constraints. J. Franklin. Inst. 2022, 359, 697–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Guan, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, H. Dynamic event-triggered and self-triggered control for saturated systems with anti-windup compensation. J. Franklin. Inst. 2017, 354, 7624–7642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zou, W.; Fei, S. Event-based dynamic output-feedback controller design for networked control systems with sensor and actuator saturations. J. Franklin. Inst. 2017, 354, 4331–4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Peng, C.; Zheng, M. Improved results for linear discrete-time systems with an interval time-varying input delay. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2016, 47, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Lu¨, S.; Yu, J. Adaptive NN-based consensus for a class of nonlinear multi-agent systems with actuator faults and faulty networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 33, 3474–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).