Abstract

This work investigates the viability of using NNs to select an appropriate controller for a dynamic system based on its current state. To this end, this work proposes a method for training a controller-scheduling policy using several learning algorithms, including deep reinforcement learning and evolutionary strategies. The performance of these scheduler-based approaches is evaluated on an inverted pendulum, and the results are compared with those of NNs that operate directly in a continuous action space and a backpropagation-based Control Scheduling Neural Network. The results demonstrate that machine learning can successfully train a policy to choose the correct controller. The findings highlight that evolutionary strategies offer a compelling trade-off between final performance and computational time, making them an efficient alternative among the scheduling methods tested.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the application of neural networks in decision-making has become a common topic in fields such as logistics, power distribution, and robotics. Several training algorithms allow a suitable choice to be determined from a set of input and output data. Other approaches, such as unsupervised methods, train NNs to play games, for example, where input data, such as an image frame, is mapped to discrete actions, such as go up, go down, and so on.

Despite their broad use in decision-making, the potential of neural networks to act as controller schedulers, i.e., deciding which controller to use in a dynamic system, remains largely unexplored. In robotics, tasks such as locomotion or manipulation often involve distinct operational phases or environmental changes. These variations mean that a single controller is usually insufficient, creating a need for a higher-level scheduler to manage multiple specialized control strategies.

This work is motivated by the self-righting problem of a quadrupedal robot. The self-righting enables a robot to recover from a fall. Established strategies often use machine learning frameworks to determine the joint references for a low-level controller [1] or employ a trained NN to manage the entire task [2]. In a previous study [3], a Reference Governor Control implemented using Model Predictive Control (RGC-MPC) was employed for the stand-up phase of the robot. Since MPC strategies rely on a dynamic model, and during the task, this model and its constraints change due to varying contact points, more than one MPC optimization problem is required to complete the task. Therefore, a method is needed to schedule these optimization problems to ensure the robot can recover safely. Thus, this paper investigates the following research question: Can a machine learning algorithm effectively train a neural network to derive a scheduling rule for controller selection based solely on the system’s proprioceptive states?

To address this question, this work develops a methodology that utilizes machine learning algorithms to train a neural network to select a controller for a dynamic system, employing a curriculum approach. To prevent the NN from choosing only one control index, a model preference term is added to the reward/fitness function to penalize or reward the NN’s output. This work also presents a comparative study of machine learning frameworks for training neural networks, with a focus on deep learning and evolutionary strategies. The main goal of this paper is to obtain a simple NN policy, trained efficiently, that is capable of stabilizing an inverted pendulum.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the state-of-the-art of multiple controllers scheduled by neural networks. Section 3 defines the core problem and the proposed methods for its solution. Section 4 describes the methodology used to solve the problem of scheduling the controller using machine learning approaches. The results are presented and discussed in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 provides the findings of this work.

This paper uses the following notation: bold, capital letters () represent matrices, and bold lowercase letters () represent vectors. Italic letters denote time-variant scalars, while non-italic, roman letters () denote constants. denotes neural network weights or parameters. To remain consistent with the relevant literature, and represent the current and following system states, respectively.

2. State of the Art

Researchers have utilized neural networks for controlling dynamic systems for a long time. In the 1990s, researchers published studies comparing the capabilities of neural networks with the traditional control methods available at the time [4,5]. Some key strengths of NNs highlighted in these studies include their ability to approximate nonlinear systems, a high degree of fault tolerance due to their intrinsic parallel distributed processing, their capacity to learn and adapt, and their natural ability to handle Multiple-Input–Multiple-Output (MIMO) systems. These characteristics make NNs suitable for control applications such as generating black-box models of dynamic systems.

Furthermore, in [4,5], the use of neural networks for supervised control is highlighted for direct inverse control, internal model control, predictive control, optimal control, adaptive control, gain scheduling, and filtering predictions. However, the authors [4,5] also pointed out challenges associated with using NNs in control applications, such as the lack of a rigorous stability theory for neural network-based control systems, difficulties in selecting network architecture, generalization problems, and robustness issues.

A specific and challenging application of NNs in control is their use as a high-level controller scheduler. In this case, the neural network is used to select an operational mode to control a dynamic system. The NN can be interpreted as a hierarchical controller responsible for scheduling specific control methods.

It is essential to distinguish this high-level scheduling approach from other common uses of NNs in control. One popular area is knowledge transfer, where a neural network is trained to mimic the behavior of a complex, computationally expensive controller, such as an MPC [6]. The goal is to replace the original controller with a fast NN approximation. Another area is adaptive control, where NNs are often used to tune the parameters of an existing controller (like a PID) in real-time [7,8] or to learn and compensate for model uncertainties and parametric errors [9].

The framework proposed in this work is fundamentally different from both of these. It is not knowledge transfer, as the NN is not trained to mimic any single expert. Furthermore, it is not a typical adaptive controller, as it does not modify the gains or parameters of a low-level controller. Instead, the NN functions purely as a high-level scheduler that selects one entire, pre-defined control law from a set of distinct, available options.

Systems that exhibit more complex behavior, with significant nonlinearities, may struggle for a single NN to learn the controlling behavior. In this sense, [10] employs smaller controllers that are individually pre-trained to perform optimally over different parts of the system’s nonlinear behavior. In the online phase, a moving average estimates the root mean square (RMS) of the reference signal to select the desired NN. Reference [11] proposes the Multi-Expert Learning Architecture (MELA), a hierarchical framework that learns to generate adaptive skills from a group of pre-trained expert policies. The core of their solution is a Gating Neural Network (GNN) that dynamically synthesizes a new, unified control policy in real-time by calculating a weighted average of the network parameters—the weights and biases—of all available experts. It is worth noting that both [10,11] employ neural networks as the underlying expert policies. In contrast, the present work uses a neural network to select from a set of distinct, predefined control strategies.

A hierarchical control framework for a rotary inverted pendulum is presented in [12]. This architecture utilizes two collaborating neural networks trained by reinforcement learning agents: a low-level controller and a high-level supervisor. The low-level controller is trained by a (DDPG) agent, which employs a 13-layer neural network to manage the continuous torque application. This NN learns to operate in two distinct modes: an energetic swing-up action to raise the pendulum and a fine-tuned stabilization action to maintain its upright position. A Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) agent trains a high-level supervisor NN, learning the discrete task of selecting when to switch the control objective from swing-up to stabilization, which occurs when the pendulum reaches a near-vertical region. The authors validate this DDPG-PPO architecture against a conventional PID controller. The proposed method exhibits superior performance, stabilizing the pendulum more effectively and reducing the maximum angle deviation compared to the PID controller.

In [12], the neural network training is closely tied to the system model. Consequently, if the model lacks sufficient fidelity, the sim-to-real transfer of the controller can be problematic. To mitigate this, modeling inaccuracies can be incorporated into the training process to enhance the NN’s robustness; however, this approach typically slows the convergence rate.

Training neural networks for scheduling linear controllers is discussed in [13,14]. In their approach, each controller has an associated NN that predicts the future cost of applying its corresponding controller, allowing a function to select the one with the minimum predicted cost. This approach is the one that most closely addresses the central question of this work.

The neural network training occurs in two stages. First, during an offline phase, the system is placed in random initial conditions and distributed over the state space. Then, the system is simulated for each controller, gathering the state evolution into a dataset. Using this dataset, the cost-to-go is estimated as:

where is a discount factor, is the final state using the i-th controller starting the initial state . is a cost function in the shape . Using the dataset, the neural network is trained to minimize the error between the actual value and the one predicted by the NN. A total of 5000 random trajectories were evaluated for this purpose [13,14].

In the second stage, with these pre-trained neural networks, training continues online; however, the paper does not clarify whether the switching rule is used in conjunction with or only new trajectories are used to validate the NN predictions.

The main difference between the two works lies in this selection function. In [13], a min function is used to schedule the controllers, and the solution is explored in a cart inverted pendulum (CIP) on a cart system. In contrast, [14] employs a more elaborate switching control to avoid the chattering presented in the previous work; in addition to the CIP, a submerged vessel is also used for testing the solution.

The Control Scheduling Neural Network (CSNN) described in [13,14] allows model mismatch to be addressed by the low-level controllers at a high frequency, leaving the NN responsible only for selecting the appropriate control strategy. A drawback of this method is the need to evaluate the neural network output at each sampling instant. This process can be computationally expensive, particularly for large network architectures or systems with numerous control strategies. Furthermore, this approach requires using a single performance index, , for all controllers to ensure a fair comparison in selecting the optimal control action at time step k. This requirement implies that all candidate controllers must operate within the same state–space neighborhood.

The review of the state-of-the-art reveals two primary approaches for NN scheduling, each with significant drawbacks. RL-based methods [12] are heavily model-dependent. In contrast, cost-to-go methods [13] are limited by the need for a single, universal performance index, forcing all candidate controllers to operate within the same state–space neighborhood.

This work presents a novel framework for creating a controller scheduler using machine learning, specifically designed to address these limitations. The primary objective is to avoid using an energy function, as in [13], thereby removing the constraint that limits controller architectures to operating in the same neighborhood. To achieve this, this study uses a policy to choose the controller instead of having the NN compute the control action directly. This approach can accelerate the training process, as the system dynamics are already known, and well-established controllers for this problem exist in the literature. The switching behavior is achieved through a mode preference term added to the reward/fitness function, where the coefficients can be tuned heuristically based on the designer’s knowledge. The methodology used in this study is presented in Section 3.

3. Problem Formulation and Background

This section establishes the formal framework for this work. First, the controller scheduling problem is defined, including the proposed control architecture, key variables, and primary objective. Following this formulation, the section provides a foundational review of the two main classes of algorithms used in this study to solve the scheduling problem: machine learning methods and evolutionary strategies.

3.1. Problem Statement

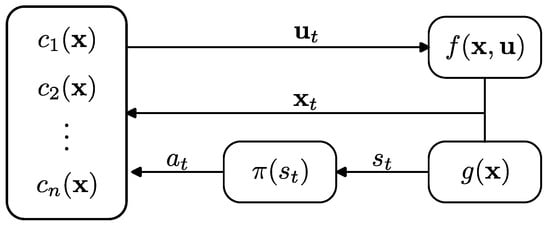

Let be a set of available controllers for the system . Each controller is responsible for imposing a specific behavior on the system according to a control rule. In the instant t, the neural network policy produces the output , where , being the index of the controller . In other words, the policy selects which controller to use, considering the system’s current state . Figure 1 demonstrates the proposed control architecture.

Figure 1.

Proposed control-scheduling architecture: the policy returns the action as the index of the controller to be used in the system.

In Figure 1, the function is used to convert from the system states to . This approach can be used, for example, to normalize the system states within a certain range, thereby improving the learning process.

The objective is to train the policy to select the appropriate controller according to the system’s state. It is necessary to consider that the neural network’s output must be in the discrete action space. From the stated objective, one problem arises: if controller i is chosen at instant t, the closed-loop dynamics may take some time to effectively drive the system from the initial state to a different one. This type of behavior makes it difficult to measure the effectiveness of selecting action i.

To train the NN, this work investigates two classes of algorithms: machine learning methods, discussed in Section 3.2, and evolutionary strategies, discussed in Section 3.3.

3.2. Background: Reinforcement Learning Methods

Depending on the nature of the task, several ML algorithms can be used, such as regression models, instance-based algorithms, decision trees, Bayesian methods, and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs). Among these, ANNs are of particular interest since their flexible structure allows them to be modified for various contexts [15].

The machine learning models can be categorized as follows [16,17,18]:

- Supervised learning is a task-driven approach that utilizes a labeled dataset, where a known output is associated with each input. The objective is to train a model to learn the mapping between these inputs and outputs for tasks such as classification and regression. Once trained, the model can predict outcomes for new, previously unseen data.

- Unsupervised learning is an approach that discovers hidden patterns and structures in unlabeled data. It can group the sample data into different groups based on the similarities of the inputs. Unlike supervised learning, it does not rely on known outputs or supervisors to find these structures. After the training phase, the model can categorize new data points by determining which of the learned groups they belong to based on similarity.

- Semi-supervised learning combines aspects of the previous two approaches. The dataset comprises a small amount of labeled data and a large amount of unlabeled data. This method is advantageous because it can significantly reduce the cost and effort of creating a fully labeled dataset, which is often expensive and requires expert knowledge.

- Reinforcement learning is a machine learning framework driven by rewards generated from the interaction between an agent and an environment. The learning process occurs through the agent learning to map its current state to an action. The ultimate goal is to develop a policy that maximizes cumulative reward over time, guided by a scalar reward signal from the environment.

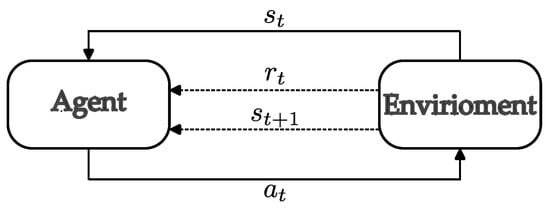

Therefore, based on the initial question of this work, the reinforcement learning strategy appears to be a promising tool for use. Figure 2 shows the standard framework for reinforcement learning algorithms. At instant t, the agent receives the state and returns an action . This action is then applied to the environment, returning the following information: the next state, , and the reward, . Some ML algorithms use this information to improve the agent’s policy.

Figure 2.

Basic machine learning framework.

Several reinforcement learning algorithms have been developed in recent years [19,20]. Given the nature of the central question of this work, choosing a specific controller from the set , the selected algorithms can inherently handle a discrete action space. Another key consideration was their availability in the Stable Baselines3 (SB3) library.

SB3 is a set of reliable implementations of reinforcement learning algorithms in PyTorch (2.8.0+cu126) [21], making it a powerful tool for testing and comparing various ML algorithms. From the algorithms available, the following were used.

3.2.1. Deep Q Network

Deep Q-Network is considered the first deep learning model to successfully learn control policies directly from high-dimensional sensory inputs using reinforcement learning [22]. DQN is derived from the Q-learning algorithm [23]. While traditional Q-learning employs a Q-table trained using the Bellman equation to map state–action pairs to their respective Q-values, DQN instead uses a neural network. This network is trained with a loss function derived from the Bellman equation to approximate the Q-value function.

DQN addresses several fundamental challenges that had previously made deep learning incompatible with reinforcement learning. By replacing Q-tables with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), DQN enables learning from high-dimensional visual inputs that would be intractable for tabular methods. Unlike supervised learning approaches, DQN learns directly from sparse, delayed reward signals without requiring labeled training data [22].

In the DQN framework, represents the expected future discounted return that can be achieved from state s by taking action a. The goal is to approximate the optimal action–value function , representing the maximum expected return achievable by following any policy. DQN trains the neural network by minimizing the Bellman error using temporal difference learning. Another breakthrough of the DQN is the possibility of using the experience replay mechanism, which stores and randomly samples past experiences, breaking the correlation between consecutive samples and stabilizing the training process.

The seminal paper [22] demonstrates that DQN can train a CNN to play Atari games. The trained CNN successfully learned complex temporal sequences, outperforming all previous approaches on six of the seven games tested and achieving superhuman performance on three of them.

DQN has been applied to various fields, including autonomous navigation in robotics [24] and disease prediction [25]. Common variants of the DQN algorithm include Double DQN and Dueling DQN [26].

3.2.2. Advantage Actor–Critic

Advantage Actor–Critic (A2C) is the synchronous counterpart derived from Asynchronous Advantage Actor–Critic (A3C) [27]. Both are on-policy Actor–Critic methods, where the Actor selects actions and the Critic evaluates their quality. The key difference lies in the training procedure: while A3C uses multiple parallel Actor-learners for asynchronous updates, A2C employs synchronous batch updates. The term on-policy indicates that training data is generated by the current policy being optimized.

The Actor is a stochastic policy that outputs a probability distribution over actions given the current state . The Critic estimates the value function and is used to compute the advantage function , which in practice is often estimated using the temporal difference error , where is the discount factor.

During training, the Actor’s parameters are updated via stochastic gradient ascent to maximize expected returns. In contrast, the Critic (with parameters ) is trained using temporal difference (TD) learning to minimize the value prediction error. A2C can utilize multiple parallel environments to collect batches of experience for synchronous updates, though this differs from A3C’s asynchronous approach, where individual actors update the shared model independently.

Some recent works that employ A2C include traffic light control for connected vehicles [28], robotics assembly tasks [29], and inventory management [30]. Further details about A2C can be found in [31,32].

3.2.3. Proximal Policy Optimization

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), introduced in [33], is an on-policy gradient method that employs conservative updates to prevent destructive policy changes.

Unlike standard policy gradient methods that perform one gradient update per data sample, PPO enables multiple epochs of minibatch updates on the same data, significantly improving sample efficiency. This stability is achieved primarily through a Clipped Surrogate Objective, which constrains the probability ratio to within , where is a hyperparameter defined by the user. Another approach demonstrated in the paper is the use of an adaptive Kullback–Leibler (KL) penalty. These considerations result in more stable and reliable learning compared to traditional approaches [33].

PPO also includes a value loss term to train the critic and an entropy bonus to encourage exploration. It typically employs Generalized Advantage Estimation (GAE) to reduce variance in the computation of the advantage. This combination makes PPO both sample-efficient and robust [33].

The results presented in [33] demonstrate that the PPO can be used in high-dimensional continuous control tasks using MuJoCo, including complex humanoid locomotion. Additionally, the framework was tested in the Atari environment, achieving better results than other state-of-the-art deep learning algorithms, and won 30 out of 49 Atari games in terms of sample efficiency.

Applications of PPO have been demonstrated in the following scenarios: battery and robot power management [34,35]; quadrotor control [36]; and power electronic circuits [37].

3.3. Background: Evolutionary Strategies

Evolutionary strategies (ESs) are a class of evolutionary optimization algorithms, a broader category from Evolutionary Computation, including genetic algorithms, genetic programming, differential evolution, and evolutionary programming [38]. Inspired by Darwin’s theory of natural evolution, ES algorithms are black-box optimizers that iteratively refine a population of candidate solutions [39,40].

In the ES framework, each iteration of the algorithm is commonly referred to as a generation. A population of n individuals (candidate solution), each defined by a genome (set of parameters), is evaluated on a given task. After finishing the task, each individual is assigned a performance score, known as its fitness. Individuals with higher fitness are more likely to be selected to produce the next generation’s population. The new population (offspring) is created by applying variation operators, such as mutation and/or crossover, to the genomes of the selected parents [39].

Recently, several studies have addressed ES as an alternative to reinforcement learning. According to [41], this approach does not require gradient information for backpropagation, making ES robust and applicable to many problems, including those with non-differentiable objective functions, noisy or sparse reward signals, and long time horizons. Their results show that ES can achieve performance comparable to that of modern RL methods in environments such as MuJoCo and Atari, although it is slightly less sample-efficient. Another finding is that ES methods exhibit a qualitatively different, and often superior, exploration behavior compared to other techniques.

In another work, ref. [42] employed ES to train simple linear policies and compared their performance to standard machine learning training methods in the MuJoCo and Atari environments. The results demonstrated that ES policies often matched or surpassed the performance of more complex deep neural networks trained using techniques such as PPO and DQN, allowing simple training policies in situations where traditional algorithms can only learn using complex ones.

A study by [43] introduced a hybrid method, referred to as CEM-RL, which combines the Cross-Entropy Method (CEM) with reinforcement learning algorithms such as the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) and Twin Delayed DDPG (TD3). In this framework, a population of actors is iteratively evaluated in an environment. The experiences are stored in a replay buffer, which is used to train a shared critic network. A portion of the actor population is then updated using gradients from this critic, while the rest are updated purely through the evolutionary process. The elite actors from the combined population are then selected to update the CEM distribution for the next generation. The approach demonstrated superior performance and stability compared to its individual components and a key competing method. This advantage was attributed mainly to more effective parameter space exploration, as the CEM sampling method prevents the population’s diversity from collapsing.

Accordingly, Section 3.3.1 presents an explanation of the Cross-Entropy Method (CEM), while Section 3.3.2 addresses the Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES). These two methods are broadly used within the ES framework to adjust neural network weights.

3.3.1. Cross-Entropy Method

The CEM is a specific type of evolutionary algorithm that can be categorized as an Estimation of Distribution Algorithm (EDA) [44]. The CEM approach represents the population’s parameters as a distribution, typically as a Gaussian distribution. Iteratively, during the generations, the method shifts the parameters towards the regions with higher fitness [45].

The optimization process begins by sampling a population of n individuals, each with parameters i, from a normal distribution . After evaluating the fitness of each individual in a specific task, the top individuals, known as elites, are selected to update the distribution parameters [45]. The update rule of the vector and the covariance matrix are

where the constant weights the parameter vector. If , a uniform weight rule is employed, whereas for , more importance is given to higher-ranked individuals. is a regularization term that adds noise to prevent premature convergence. Usually, is updated using exponential decay, as , where is the final value of the noise and is the decay factor. For the next generation, new parameters are sampled as [43].

Some variants of the CEM assume that the parameters are uncorrelated. This consideration simplifies the covariance matrix, making it a diagonal matrix [43]. Therefore, the covariance update from Equation (3) can be rewritten as

In this formulation, the square of the vectors denotes the vectors of the square of the coordinates. This simplification significantly speeds up the update and sampling steps, as it avoids the computation and storage of the full covariance matrix [43].

3.3.2. Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy

The CMA-ES is also an EDA well-established as a stochastic method for optimizing real-parameter functions that are nonlinear and non-convex [46]. The candidate parameters of the first generation are sampled according to , where is the mean vector of the search distribution, representing the current favorite solution. The parameter is the overall step-size, which controls the search scale, and is the covariance matrix, which defines the shape and orientation of the distribution. Initially, is a chosen starting point, is an initial step-size, and is typically the identity matrix, .

After the generation, the mean is updated as

Notice that Equations (2) and (5) look almost the same; however, the value of the last one is only used one generation ahead to sample the new parameters. Also, it is necessary to update the values of and .

The Cumulative Step-size Adaptation (CSA), , is employed to adjust the evolution path, , which represents an exponentially fading memory of the steps taken by the distribution’s mean over recent generations. The core of this adaptation lies in comparing the length of this evolution path against its expected length under random, uncorrelated motion. If the path is statistically longer than expected, it signifies persistent directional progress, prompting an increase in to accelerate convergence. Conversely, suppose the path is shorter than expected. In that case, it suggests oscillation or inefficient exploration, triggering a decrease in to allow for a finer-grained local search, thereby making the algorithm robustly self-adaptive to the landscape’s local topology [46].

For the , the adaptation is performed using two main principles: the rank-one update, which uses the evolution path to capture information about the correlation of successive steps over time, and the rank- update, which captures the correlation from the distribution of the best solutions within the current generation [46].

Finally, the new candidate parameters are sampled from

4. Experimental Methodology

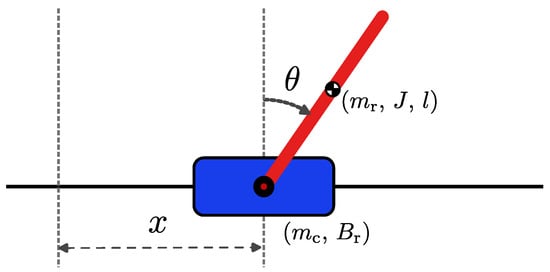

A cart-pendulum system is used to test the main hypothesis. However, another one is adopted instead of using the model presented in [13]. This decision is based on the authors’ mention that the pendulum mass is localized at the rod tip; however, the dynamic equations in their paper indicate a mass distribution along the length. Another aspect is that neither the sample time nor the solver is mentioned. Furthermore, the authors demonstrate that for an initial condition of rad (with other states at zero), the LQR is unstable, while the SM and VF controllers can stabilize the system. However, the initial tests revealed that none of the controllers could stabilize the system due to the force constraint. Therefore, the present work adopts the dynamics formulation from [47] as

where x and are the cart position and rod angle, respectively. is the mass of the cart, is the friction coefficient between the cart and horizontal bar, and d is the pendulum damping coefficient. The rod has mass , moment of inertia J, and the mass is at l. Lastly, g is the gravitational acceleration. Figure 3 shows the system representation. The system constants are shown in Table A1 in Appendix A.

Figure 3.

Representation of the cart-pendulum system and its parameters.

Equation (7) can be arranged in the space–state format, with the following state vector:

therefore, the dynamics are rewritten as

with

The system is subjected to the following constraints:

A Python class was implemented to simulate the system, where Equation (7) is updated using the Forward Euler integration method, with ms. Additionally, to address the x constraint, a soft-wall dynamic was implemented using a spring–damper model. The decision to use a Python implementation is based on the fact that the class can be easily wrapped into the Gymnasium framework [48], which is known for having numerous testing environments for ML algorithms and the ability to create custom ones. Another aspect is that the Gymnasium framework is compatible with the SB3 framework.

For the control set, the same approach as [13] is being used, with three controllers: a Linear Quadratic Regulator, a Velocity Feedback (VF) controller, and a Sliding Mode (SM) controller. The first one is responsible for bringing the system to the origin. It was tuned to address situations where the system has small angles and velocities. The VF (also a LQR controller) was designed to bring the system to small velocities in less than one second, without considering the cart position. Lastly, the SM is designed to bring the rod to small angles as quickly as possible. All the controllers are updated at a frequency of 100 Hz, which is ten times slower than the integration time of the simulation.

The switch polices were derived for the control set using the CSNN, PPO, A2C, DQN, CEM, and CMA-ES frameworks. For the discrete action space, the reward function is written as

where

and

Here, provides a survival reward, penalizes high-energy states, and rewards progress toward lower-energy configurations. The terms and encourage central positioning and upright posture, respectively, while promotes convergence to the origin. The values of and are given by the Gaussian shaping function in Equation (13), where is a positive constant defined as , with being the value of a such that . Lastly, is the preference mode, defined in Equation (14).

In Equation (14), the variable represents the soft probability that the controller of index i is the most suitable choice at time t, obtained from a softmax over controller scores. is a small constant for numerical stability, and is a shift constant ensuring that the best choice contributes positively. To obtain , it is first necessary to define the score vector as

where

and . The terms , and are derived as follows:

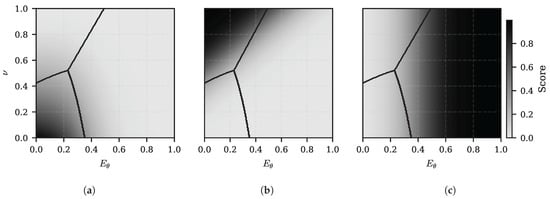

Using the values of , , and , and adjusting the constant values of Equation (16), it is possible to determine the space–state region, where each controller has more importance. Figure 4 shows the scores for the LQR, VF, and SM.

Figure 4.

Score regions: (a) LQR controller—have higher scores with small angles and velocities (lower left corner). (b) VF controller—the highest score is when the system has high kinetic energy, i.e., high linear and angular velocities (upper left corner). (c) SM controller—the highest score is with high angle values (right corner). In the figures, the dark line represents the limit of the score regions.

From the scores, the softmax probability for each controller is

Therefore, , and as i is the current controller, the value is used in Equation (19). It is important to highlight that if, at time t, controller i does not have the highest score, then the final value of is negative— that is, it receives a penalty for choosing a non-suitable controller. Conversely, if it is the best choice, the score receives a bonus. Without a preference mode score, the trained policy tends to predict only one controller index. For the system studied, a high tendency to select the VF controller was observed, likely because this controller can at least bring the pendulum rod upwards in most scenarios.

For comparative purposes, continuous action–space polices were derived for the PPO, A2C, and CEM frameworks. In the continuous action–space case, the reward function is provided by

where corresponds to Equation (11) without the mode-preference term. The coefficient penalizes control effort. The weight values of the reward function and the constants of the preference mode function are provided in Appendix C in Table A2 and Table A3, respectively.

For the SB3 and ES frameworks, a function is used to convert from the system states to the neural network states , as shown in Figure 1. For the cart pendulum, it is defined as

Using the proposed , where , simplifies the NN training once the states are normalized. Finally, , where for a continuous action space or for the discrete action space. In the last one, the control index is selected using a softmax in the last layer. For the CSNN method, to predict the cost of each controller, the NN has all the pendulum states as input and one output, i.e, .

A curriculum-learning framework was developed to train the models. A radius-based method was employed to determine the initial conditions of the system states. The difficulty is minimal at the beginning of training, with initial conditions close to the system’s origin. The reward values increase as the neural networks learn to cope with environmental variations. In evolutionary strategy frameworks, the difficulty rises slowly over the generations.

In the SB3 framework, the training provides learning feedback from which sequences of successful episodes can be identified. The difficulty is also increased when the number of successful environments exceeds a predefined threshold. As the difficulty increases, the initial conditions are placed farther from the center, making the task progressively more challenging. The difficulty factor also scales the reward function weights to normalize the learning signal, ensuring the agent is not penalized for the longer time horizons required by more challenging tasks.

To test the different scheduling algorithms, a common experimental testbed was developed based on the cart-pendulum problem. We first defined a set of three distinct controllers () to be scheduled: an LQR, a VF, and an SM controller, each designed for a different operating region. We then designed a unified, state-based reward function (Equation (11)) that includes the mode preference term (Equation (14)) to encourage practical switching. Finally, all policies were trained using a curriculum learning approach to progressively increase the task difficulty for both the machine learning algorithms (PPO, A2C, and DQN) and the evolutionary strategies (CEM, CMA-ES).

5. Results and Discussion

Considering the scheduling architecture presented in Section 3 and the experimental methodology outlined in Section 4, the NN models were trained to control the inverted pendulum on a cart. All developed scripts are available in the repository in [49].

This section is organized as follows. Section 5.1 details the final training parameters and neural network architectures. Section 5.2 presents the comparative results of all frameworks. Finally, Section 5.3 provides a discussion and summary of the key findings.

5.1. Training Setup

The neural network structure used for each framework is itemized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Neural network architecture models.

For the PPO, A2C, and DQN algorithms, time steps were used to train the agents in continuous and discrete action spaces. For the CEM and CMA-ES methods, the number of generations was determined empirically as for the discrete case and for the continuous case. These values were selected by observing the learning metrics until the reward stabilized and the standard deviation of the population’s weights converged.

Regarding the CSNN, the cost-to-go in Equation (1), was evaluated using , . The system states were initialized randomly and simulated for 2.0 s.

5.2. Training and Performance Analysis

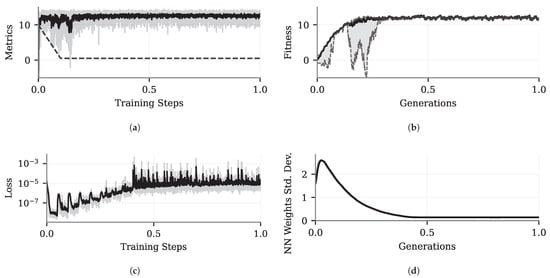

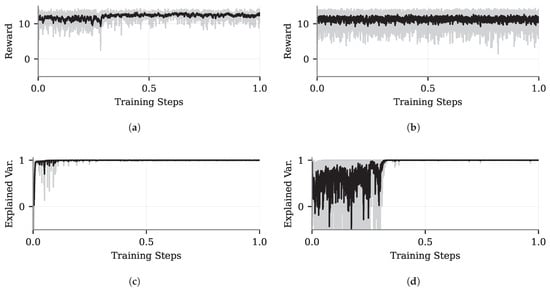

The learning metrics for the DQN and CEM are shown in Figure 5, while the metrics for the other methods are presented in Appendix D.

Figure 5.

Learning metrics: (a) DQN framework—black solid line: smoothed reward value; black dashed line: exploration rate (). (b) CEM framework—black solid line: smoothed fitness value. (c) DQN framework—black solid line: smoothed loss (d) CEM framework—extra standard deviation of the neural network weights. The x-axis was normalized between 0 and 1 in all figures.

For the DQN, as shown in Figure 5a, the mean reward remains constant throughout the learning process, a result of the curriculum learning strategy. At the beginning of the training, the task’s difficulty is low. Consequently, the pole generally remains upward even when an action is chosen randomly from any of the controllers (due to a high exploration rate). Although the pole angle, , tends toward zero, the high variance in the reward (shaded gray area) occurs because the chosen controller may not always guide the cart to the center. As training progresses, the task difficulty increases, causing the loss to rise until it stabilizes around the midpoint of the process (Figure 5c). Nevertheless, despite the increasing loss, the reward remains constant, indicating that the neural network learns to handle new situations not encountered during the initial stages of training.

Regarding the CEM, the results in Figure 5b illustrate that, despite using the curriculum approach, the fitness value in the first generation is close to zero and can even be negative, mainly because the neural network weights are initialized randomly, causing the policy to change controllers frequently and leading the system to instability. As the generations progress, the policies become more deterministic. This convergence reduces the variance among the NN weights (Figure 5d), resulting in better selections of the controller index for each scenario.

To compare the performance of all the methods analyzed, a set of 350 random initial conditions (ICs) was created and used to test each framework. For a better comparison across the different action spaces, a cost function was defined as

where and are weight matrices for the states and control effort. In this analysis, the lower the cost, the better the system behavior. Table 2 summarizes the results.

Table 2.

Comparison of the frameworks’ performances.

Based on the mean cost data analysis in Table 2, the discrete action frameworks exhibit superior performance compared to their continuous counterparts. Despite using curriculum learning, the results show that within the trained interval, the PPO, A2C, and CEMs were unable to learn the task. The primary hypothesis for this observation is that the neural networks are trapped in a local minimum and cannot escape from it. Exploring the hyperparameters further for A2C and PPO could aid this learning process; however, it is not a trivial task, as it is time-consuming and requires careful consideration. For the CEM, an alternative approach is to increase the number of generations, allowing the best individuals to dominate the population.

The DQN, CEM, PPO, and CMA-ES frameworks show similar results within the discrete group. Examining the cost through their respective confidence intervals (DQN: [115.52, 193.92]; CEM: [129.05, 210.49]; PPO: [131.75, 213.72]; CMA-ES: [156.30, 213.72]) reveals a considerable overlap, indicating that there is no statistical evidence to claim that one method is more cost-efficient than another. The key distinction between these methods lies in their training efficiency: the CEM framework completed training approximately 6.5 times faster than the DQN approach and 9.90 times faster than PPO. This result highlights CEM as a compelling alternative to more conventional machine learning-based frameworks, as it combines comparable control performance with significantly reduced computational demands. Compared to other methods from the SB3 framework, A2C presents the lowest results but still achieves a considerably high success rate. Further fine-tuning of the hyperparameters for A2C and the other SB3 frameworks could improve these results.

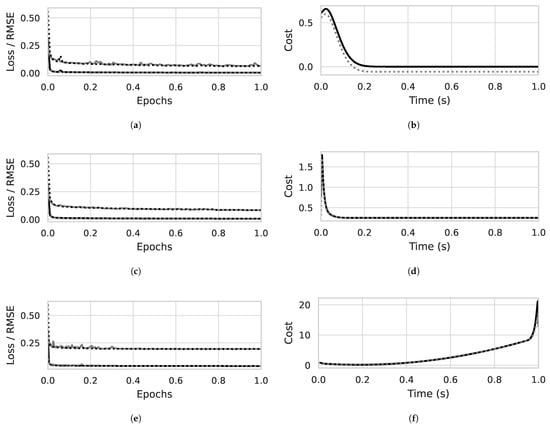

The training results for the CSNN method are presented in Figure 6. Figure 6b (LQR), Figure 6d (VF), and Figure 6f (SM) show the root mean square error (RMSE) between the actual and predicted values, as well as the training loss. In all cases, the RMSE is less than 0.1 for both training and validation data (30.0% of the initial dataset).

Figure 6.

Training metrics for the CSNN method. (a) LQR controller training loss and RMSE. (b) LQR predicted cost-to-go. (c) VF controller training loss and RMSE. (d) VF predicted cost-to-go. (e) SM controller training loss and RMSE. (f) SM predicted cost-to-go. For all the controllers: left figure—black solid line: training loss; gray dashed line: validation loss; black dashed line: training data root mean square error; gray solid line: validation data root mean square error; right—black: true cost-to-go; gray: predicted cost-to-go.

Figure 6 on the right demonstrates the NNs’ predictive accuracy on a random initial trajectory. The networks’ predictions closely match the true cost-to-go, achieving low Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and high correlation for all three controllers: LQR (Figure 6a; MAE: 0.14, Corr: 0.99), VF (Figure 6b; MAE: 0.0055, Corr: 0.98), and SM (Figure 6c; MAE: 0.059, Corr: 0.99).

Although the NNs effectively predict the controller cost, the overall results show poor performance for scheduling the controllers. The main hypothesis for this discrepancy in the results from [13] is the lack of information about the sample time. To evaluate the cost-to-go, it is necessary to multiply by the factor . If a larger sample time, T, is used, some information is lost; conversely, if a small one is used, the cost tends to zero too rapidly. Therefore, the sample time is crucial information for implementing the CSNN strategy correctly.

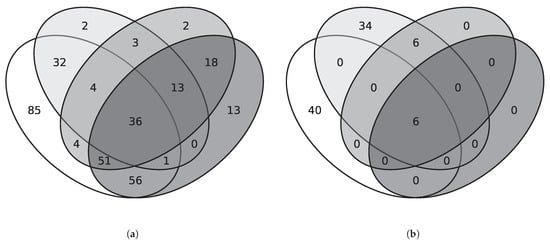

Regarding the failure cases, 46 initial conditions were identified in which none of the frameworks could control the system. These conditions can be grouped into four categories: (i) contradictory dynamics, where the cart’s velocity direction opposes the pole’s lean; (ii) high difficult starting conditions, characterized by large angular deviations () combined with non-negligible initial velocities ( or ); (iii) extreme initial velocities, defined as ; and (iv) high-energy states, where the total energy exceeds . It is essential to mention that the failures are related to the force constraint: if there are no constraints, all controllers can bring the system to the origin. Figure 7a illustrates the distribution of the complete set of initial conditions across the defined categories. Figure 7b then isolates the subset of ICs for which all frameworks failed, showing the classification for only these unsuccessful cases.

Figure 7.

Venn diagram showing the number of initial conditions within defined categories. (a) Distribution of the complete set of tested conditions. (b) Conditions subset for which all controllers failed to stabilize the pendulum. Categories are defined as contradictory dynamics (white), high difficulty (light gray), extreme velocities (gray), and high-energy states (dark gray).

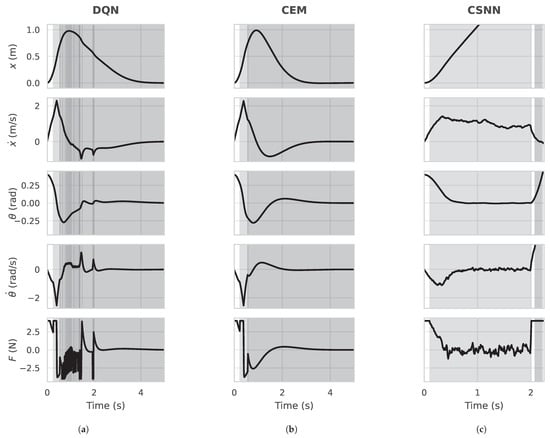

Figure 8 shows the cart-pendulum state behavior using the DQN, CEM, and CSNN approaches to select the controller. The initial state is , and all other states are zero, the same initial condition (IC) used in [14]. Based on a heuristic analysis, the policy is expected to first choose the SM controller due to the large tilt angle, then select the VF controllers to reduce the cart velocity, and lastly, select the LQR to bring the pendulum to the system’s origin. It is possible to observe that both the DQN and CEM were able to stabilize the system at the origin (Figure 8a,b). The main difference lies in the number of control switches: while the NN evolved by the CEM made only three changes (SM, SM to VF, and VF to LQR), the neural network trained by the DQN algorithm made 54 changes to the control index, a behavior that is not desired, as it can lead the system to an unstable situation. For the CSNN, the control architecture made 11 changes but was unable to control the system, as shown in Figure 8c. As mentioned earlier, despite accurately predicting the cost-to-go, the switch rule was unable to select the correct controller.

Figure 8.

State trajectories and control effort using NN to schedule the control method: (a) PPO, (b) CEM, and (c) CSNN. White area—SM controller mode; light gray area—VF controller mode; dark gray area—LQR controller mode.

Another aspect studied in this work is the system’s behavior when noise is added. In this case, another batch of random initial conditions was generated near the system’s origin to ensure that all controllers could stabilize the cart-pendulum system. With this configuration, the system’s mean cost was measured () for each case studied. Then, white noise was added to the simulation using the same seed under the same conditions. Again, the mean cost was measured (). The cost variation percentage was evaluated using these quantities. Table 3 summarizes the results.

Table 3.

Comparison of the approaches adding noise into the system.

As expected, the cost grows in all situations when noise is added to the system. The discrete frameworks continue to have the lower cost; however, the cost variation is of the same order for all methods, except for the CSNN and the continuous action space PPO. The CEM was the framework whose performance deteriorated the most. Despite these cost increases, no failures were observed due to the addition of noise.

Another metric studied was the average time required for the policy to evaluate the output, also presented in Table 3, as the column and its confidence interval . Considering that each policy update must occur within the controller’s 10 ms sample period, all frameworks can be utilized in a real-world application. The fastest update was observed using the CEM framework, where the update took less than 1.00% of the sample time.

As expected, due to its complexity and the number of NNs to be updated, the CSNN takes longer than the other frameworks. In this case, the update time consumes almost 10.00% of the sample period. Therefore, this is not a trivial amount of time and must be taken into consideration in the controller’s design.

5.3. Discussion Summary

The analysis confirms that both reinforcement learning and evolutionary strategies can successfully train a neural network policy for controller scheduling. The results yield three key findings. First, the discrete action–space frameworks (DQN, CEM, PPO, CMA-ES) significantly outperformed their continuous–space counterparts, which largely failed to converge. Second, while the top discrete methods showed statistically similar cost performance, the evolutionary-based CEM framework was approximately an order of magnitude faster to train than RL-based methods, such as PPO and DQN. Third, the quality of the resulting policy varied significantly: the CEM-trained policy was stable and logical.

In contrast, the DQN policy exhibited high-frequency “chattering,” making it less practical for a physical system. Finally, the baseline CSNN method failed to perform, highlighting a critical dependency on implementation details not provided in the original literature. These findings collectively suggest that for this scheduling problem, an evolutionary approach, such as CEM, offers the best trade-off between final performance, training efficiency, and policy stability.

6. Conclusions

This work investigated the possibility of using neural networks as control schedulers. The investigation focused on analyzing existing machine learning algorithms capable of handling systems with continuous action spaces. To do so, the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), Advantage Actor–Critic (A2C), and Deep Q-Network (DQN) algorithms from the Stable-Baselines3 library were investigated. Additionally, two evolutionary strategies were tested: the Cross-Entropy Method (CEM) and the Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES). Lastly, a Control Scheduling Neural Network (CSNN) was implemented and tested. All training algorithms were evaluated on a cart-inverted pendulum system.

The results show that policies trained by machine learning algorithms can choose the correct controller based solely on the system’s states. The PPO, DQN, CEM, and CMA-ES frameworks achieved comparable performance in a pure cost analysis. The main difference was the computational time spent on training: the CEM was the fastest algorithm, yielding results in under two hours—a crucial metric, as it enables rapid testing compared to the others. The CSNN showed poor results, mainly due to the lack of information from the [13]. A more thorough investigation could yield better results.

Another aspect studied in this paper is the comparison with purely neural network control schemes, where the NN generates the control force for the system. A cost comparison revealed that the discrete action space approach outperformed the continuous action space approach.

For future work, it is essential to investigate how the number of states and controllers affects the training process. Another aspect to be explored is the use of different control algorithms, such as a swing-up controller, to handle situations where a lack of control action leads to catastrophic scenarios. In this case, the new controller could bring the pendulum upward, and the other controllers could stabilize the system. Furthermore, it is essential to investigate the possibility of hybrid methods, such as using CEM for initial training and then adding the resulting NN to PPO or DQN algorithms for fine-tuning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.D. and G.A.; Methodology, A.G.D. and G.A.; Software, A.G.D.; Validation, A.G.D.; Formal analysis, A.G.D. and D.W.B.; Investigation, A.G.D.; Resources, A.G.D.; Writing—original draft, A.G.D., G.A. and D.W.B.; Supervision, D.W.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Inovação do Estado de Santa Catarina—FAPESC, scholarship call 48/2021.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT, version 4, for grammar checking and statistical analyses of the results. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| A2C | Advantage Actor–Critic |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| BLF | Barrier Lyapunov Function |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CEM | Cross-Entropy Method |

| CIP | Cart-Inverted Pendulum |

| CMA-ES | Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy |

| CSA | Cumulative Step-size Adaptation |

| CSNN | Control Scheduling Neural Network |

| DDPQ | Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| DQN | Deep Q-Network |

| EDA | Estimation of Distribution Algorithm |

| ES | Evolutionary Strategies |

| GAE | Generalized Advantage Estimation |

| GNN | Gating Neural Network |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Units |

| IC | Initial Condition |

| KL | Kullback–Leibler |

| LQR | Linear Quadratic Controller |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MELA | Multi-Expert Learning Architecture |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| MIMO | Multiple-Input–Multiple-Output |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NN | Neural network |

| PID | Proportional–Integral–Derivative |

| PPO | Proximal Policy Optimization |

| RGC | Reference Governor Control |

| RK | Reinforcement Learning |

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

| SB3 | Stable Baseline3 |

| SM | Sliding Mode |

| VF | Velocity Feedback |

Appendix A. System Constants

Table A1.

System constants.

Table A1.

System constants.

| Constant | Value | Constant | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.50 kg | d | 0.01 Ns/m | |

| 0.20 kg | 2.00 m | ||

| l | 0.30 m | 4.00 N | |

| 0.10 kg/s | 2.75 m/s | ||

| g | 9.81 m/s2 | 10.0 rad/s | |

| J | kgm2 | - | - |

Appendix B. Controllers

Appendix B.1. Linear Quadratic Regulator

For the LQR and VF controllers, the control rule is

For the LQR control the gain was obtained using the following weight matrices:

resulting in

As for the VF controller, the weight matrices are

leading to:

Appendix B.2. Sliding Mode Controller

For the SM controller, a slide surface is defined as

Then, the control action is

where is the nominal control value that solves for Equation (7) and satisfies for . Furthermore, is considered , and . For the SM controller, the constant d was considered zero.

Appendix C. Reward Function

Table A2.

Reward/fitness function weights values.

Table A2.

Reward/fitness function weights values.

| Weight | Value | Weight | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| - | - |

Table A3.

Preference formulation weights.

Table A3.

Preference formulation weights.

| Weight | Value | Weight | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

Appendix D. Training Metrics

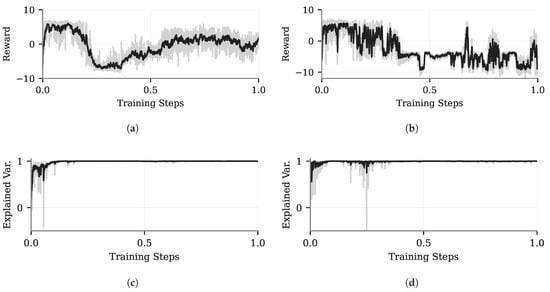

Figure A1c shows that the PPO maintains a nearly constant mean reward throughout the training process because, even when the network selects random actions, any of the controllers can stabilize the pendulum. From the beginning of training, the explained variance, as shown in Figure A1c, remained close to one, indicating that the critic network’s value predictions closely matched the empirical returns—a strong indication that the value function was accurately learned. For the A2C, although the reward remains high throughout the training period (Figure A1b), the explained variance (Figure A1d) fluctuates in the first quarter, indicating poor predictions from the critic. However, as training progresses, this value trends toward one. For both cases, based on the reward and explained variance, it is possible to assume that the NNs learned the task of scheduling the controllers.

In the continuous case, the initial NNs can stabilize the system, leading to high reward values. However, as the difficulty increases, the number of failures grows, reducing the mean reward for both PPO and A2C (Figure A2a and Figure A1b, respectively). The PPO continues to improve the reward values, whereas for A2C, the reward stabilizes at approximately . This result indicates that A2C is in a local minimum. Therefore, based on the reward and explained variance for the PPO in the continuous action space (Figure A1c), it is possible to conclude that the NN learned to control the system. For A2C, since the reward is on a plateau with a negative value while the explained variance is 1 (Figure A2d), it is assumed that the NN cannot control the system adequately. To improve these results, it is necessary to further explore the hyperparameter values.

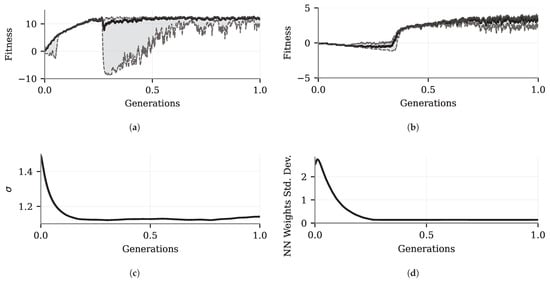

Figure A1a illustrates the fitness evolution of CMA-ES in the discrete action space. Although the fitness value is close to zero at the beginning of training—similar to the CEM case—the neural network progressively learns to select the appropriate controller as the generations evolve. When the overall step-size stabilizes and tends toward a constant value (Figure A3c), it indicates that the neural network parameters are converging toward a steady-state solution. Given that the corresponding reward remains high, it is reasonable to conclude that the neural network has successfully learned to schedule the controllers from the set. Figure A3b reflects the fitness training data for the CEM used in the continuous action space. In this case, different from PPO and A2C, the initial NN cannot stabilize the system. As the standard deviation of the NN weights decays (Figure A3d), making the population less random, the best individual is selected, causing the fitness to rise. As the metrics stabilize with a high fitness, the NN learned to control the pendulum in the discrete action space using the ES strategy.

Figure A1.

Learning metrics for the deep machine learning discrete case: (a) PPO reward. (b) A2C framework reward. (c) PPO explained variance. (d) A2C explained variance. Upper figures—black solid line: smoothed reward value. Lower figures—black solid line: explained variance. The x-axis was normalized between 0 and 1.

Figure A2.

Learning metrics for the deep machine learning continuous case: (a) PPO reward. (b) A2C framework reward. (c) PPO explained variance. (d) A2C explained variance. Upper figures—black solid line: smoothed reward value. Lower figures—black solid line: explained variance. The x-axis was normalized between 0 and 1.

Figure A3.

Learning metrics for the evolutionary framework: (a) CAM-ES discrete action space framework: black solid line: smoothed fineness value. (b) CEM continuous action space framework: black solid line: smoothed fitness value. (c) CMA-ES overall step-size. (d) CEM extra standard deviation of the neural network weights. The x-axis was normalized between 0 and 1.

References

- Lee, J.; Hwangbo, J.; Hutter, M. Robust recovery controller for a quadrupedal robot using deep reinforcement learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.07517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, H.; Qin, Z.; Moiseev, G.V.; Huo, J. Research on self-recovery control algorithm of quadruped robot fall based on reinforcement learning. Actuators 2023, 12, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrikopf, A.G.; Schulze, L.; Widlgrube Bertol, D.; Barasuol, V. MPC-Based Reference Governor Control for Self-Righting of Quadruped Robots: Preliminary Results. In Proceedings of the 2022 Latin American Robotics Symposium (LARS), 2022 Brazilian Symposium on Robotics (SBR), and 2022 Workshop on Robotics in Education (WRE), São Bernardo do Campo, Brazil, 18–21 October 2022; pp. 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, K.; Sbarbaro, D.; Żbikowski, R.; Gawthrop, P. Neural networks for control systems—A survey. Automatica 1992, 28, 1083–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagan, M.; Demuth, H. Neural networks for control. In Proceedings of the 1999 American Control Conference (Cat. No. 99CH36251), San Diego, CA, USA, 2–4 June 1999; Volume 3, pp. 1642–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekhar, N.; Nagappan, K.K.; Radhakrishnan, T.K.; Devaraj, D. Effective MPC strategies using deep learning methods for control of nonlinear system. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2024, 12, 3694–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silaa, M.Y.; Bencherif, A.; Barambones, O. Indirect Adaptive Control Using Neural Network and Discrete Extended Kalman Filter for Wheeled Mobile Robot. Actuators 2024, 13, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Li, X.; Gao, C.; Wu, J. Neural Network Supervision Control Strategy for Inverted Pendulum Tracking Control. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2021, 2021, 5536573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inanc, E.; Habboush, A.; Gurses, Y.; Yildiz, Y.; Annaswamy, A.M. Neural Network Adaptive Control With Long Short-Term Memory. Int. J. Adapt. Control. Signal Process. 2025, 39, 1870–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, X.; Cheer, J. Dynamic neural network switching for active control of nonlinear systems. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2025, 158, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Yuan, K.; Zhu, Q.; Yu, W.; Li, Z. Multi-expert learning of adaptive legged locomotion. Sci. Robot. 2020, 5, eabb2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhourji, R.; Mozaffari, S.; Alirezaee, S. Reinforcement Learning DDPG–PPO Agent-Based Control System for Rotary Inverted Pendulum. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 49, 1683–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, E.D.; Krogh, B.H. Controller Scheduling by Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 36th IEEE Conference on Decision & Control, San Diego, CA, USA, 12 December 1997; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. 3950–3955. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, E.D.; Krogh, B.H. Controller Scheduling Using Neural Networks: Implementation and Experimental Results. In Proceedings of the Hybrid Systems V; Antsaklis, P., Lemmon, M., Kohn, W., Nerode, A., Sastry, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 86–99. [Google Scholar]

- Janiesch, C.; Zschech, P.; Heinrich, K. Machine learning and deep learning. Electron. Mark. 2021, 31, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N, T.R.; Gupta, R. A Survey on Machine Learning Approaches and Its Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Students’ Conference on Electrical,Electronics and Computer Science (SCEECS), Bhopal, India, 22–23 February 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici, İ.; Shayea, I.; Din, J. A survey of applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning in future mobile networks-enabled systems. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2023, 44, 101455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye, M.M. Understanding of Machine Learning with Deep Learning: Architectures, Workflow, Applications and Future Directions. Computers 2023, 12, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMahamid, F.; Grolinger, K. Reinforcement Learning Algorithms: An Overview and Classification. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE), Virtual, 12–17 September 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, A.K.; Pillai, G.; Chakrabarty, S. Reinforcement learning algorithms: A brief survey. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 231, 120495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffin, A.; Hill, A.; Gleave, A.; Kanervisto, A.; Ernestus, M.; Dormann, N. Stable-Baselines3: Reliable Reinforcement Learning Implementations. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2021, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Graves, A.; Antonoglou, I.; Wierstra, D.; Riedmiller, M. Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.5602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, C.J.C.H.; Dayan, P. Q-learning. Mach. Learn. 1992, 8, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Naranjo, J.; Caiza, G.; Ayala, P.; Jordan, E.; Garcia, C.A.; Garcia, M.V. Autonomous Navigation of Robots: Optimization with DQN. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdelAziz, N.M.; Fouad, G.A.; Al-Saeed, S.; Fawzy, A.M. Deep Q-Network (DQN) Model for Disease Prediction Using Electronic Health Records (EHRs). Sci 2025, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewak, M. Deep Q Network (DQN), Double DQN, and Dueling DQN. In Deep Reinforcement Learning; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Chapter 8; pp. 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Badia, A.P.; Mirza, M.; Graves, A.; Harley, T.; Lillicrap, T.; Silver, D.; Kavukcuoglu, K. Asynchronous methods for deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning, New York, NY, USA, 20–22 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, Z.; Li, W.; Fu, Y.; Ruan, K.; Di, X. CVLight: Decentralized learning for adaptive traffic signal control with connected vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2022, 141, 103728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, M.; Neto, P. Deep reinforcement learning applied to an assembly sequence planning problem with user preferences. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 122, 4235–4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, N.N.; Meisheri, H.; Baniwal, V.; Nath, S.; Ravindran, B.; Khadilkar, H. Reinforcement Learning for Multi-Product Multi-Node Inventory Management in Supply Chains. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.04037. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. OpenAI Baselines: ACKTR & A2C. 2017. Available online: https://openai.com/index/openai-baselines-acktr-a2c/ (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Wang, J.X.; Kurth-Nelson, Z.; Tirumala, D.; Soyer, H.; Leibo, J.Z.; Munos, R.; Blundell, C.; Kumaran, D.; Botvinick, M. Learning to reinforcement learn. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1611.05763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Shaw, R.; Mason, K. A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach to Battery Management in Dairy Farming via Proximal Policy Optimization. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.01653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Park, S.; Lee, R.; Kim, S.; Kwak, J.; Lee, S. Energy efficient robot operations by adaptive control schemes. Oxf. Open Energy 2024, 3, oiae012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano Lopes, G.; Ferreira, M.; da Silva Simões, A.; Luna Colombini, E. Intelligent Control of a Quadrotor with Proximal Policy Optimization Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 Latin American Robotic Symposium, 2018 Brazilian Symposium on Robotics (SBR) and 2018 Workshop on Robotics in Education (WRE), João Pessoa, Brazil, 6–10 November 2018; pp. 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, U.; Jawad, A.; Shahria, S.; Rashid, A.H.U. Proximal policy optimization-based reinforcement learning approach for DC-DC boost converter control: A comparative evaluation against traditional control techniques. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slowik, A.; Kwasnicka, H. Evolutionary algorithms and their applications to engineering problems. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 12363–12379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, E.; Madhavan, V.; Such, F.P.; Lehman, J.; Stanley, K.O.; Clune, J. Improving Exploration in Evolution Strategies for Deep Reinforcement Learning via a Population of Novelty-Seeking Agents. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1712.06560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, D.E.; Schultz, A.C.; Grefenstette, J.J. Evolutionary Algorithms for Reinforcement Learning. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 1999, 11, 241–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimans, T.; Ho, J.; Chen, X.; Sidor, S.; Sutskever, I. Evolution Strategies as a Scalable Alternative to Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.03864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; de Nobel, J.; Bäck, T.; Plaat, A.; Kononova, A.V. Solving Deep Reinforcement Learning Tasks with Evolution Strategies and Linear Policy Networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.06912. [Google Scholar]

- Pourchot, A.; Sigaud, O. CEM-RL: Combining evolutionary and gradient-based methods for policy search. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1810.01222. [Google Scholar]

- Larrañaga, P.; Lozano, J.A. Estimation of Distribution Algorithms: A New Tool for Evolutionary Computation; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2001; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- de Boer, P.T.; Kroese, D.P.; Mannor, S.; Rubinstein, R.Y. A Tutorial on the Cross-Entropy Method. Ann. Oper. Res. 2005, 134, 19–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, N. The CMA Evolution Strategy: A Comparing Review. In Towards a New Evolutionary Computation: Advances in the Estimation of Distribution Algorithms; Springer: Berlin/ Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiga, A.; Ghorbel, C.; Benhadj Braiek, N. Nonlinear/Linear Switched Control of Inverted Pendulum System: Stability Analysis and Real-Time Implementation. Math. Probl. Eng. 2019, 2019, 2391587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towers, M.; Kwiatkowski, A.; Terry, J.; Balis, J.U.; Cola, G.D.; Deleu, T.; Goulão, M.; Kallinteris, A.; Krimmel, M.; KG, A.; et al. Gymnasium: A Standard Interface for Reinforcement Learning Environments. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.17032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrikopf, A.G. AureoGD—Control Scheduling with Neural Networks. Available online: https://github.com/AureoGD/control_scheduling (accessed on 21 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).