Abstract

Underwater exploration relies heavily on autonomous underwater vehicles and sensor platforms for sustained monitoring of marine environments, yet their operational duration is limited by energy constraints. To enhance energy efficiency, various control strategies have been proposed, including robust, optimal, and disturbance-aware approaches. Recent work introduced a variable structure controller (VSC) with a constant-amplitude control action for depth control of a platform equipped with a variable buoyancy module, achieving an average 22% reduction in energy use in comparison with conventional PID-based controllers. In a separate paper, the conditions for its closed-loop stability were proven. This study extends these works by proposing a controller with a variable-amplitude control action designed to minimize energy consumption. A formal proof of stability is provided to guarantee safe operation even under conservative assumptions. The controller is applied to a previously developed depth-regulated sensor platform using a validated physical model. Additionally, this study analyzes how the controller parameters and mission requirements affect stability regions, offering practical guidelines for parameter tuning. A method to estimate oscillation amplitude during hovering tasks is also introduced. Simulation trials validate the proposed approach, showing energy savings of up to 16% when compared to the controller using a constant-amplitude control action.

1. Introduction

Energy is one of the most important topics in today’s world, given the scarcity of resources humankind contemporarily faces. Besides looking for alternative energy sources for buildings [1], industry [2], and transportation [3], research is also focused on how to reduce energy consumption in many different areas such as traffic [4], vehicle consumption [5] and industry [6].

In this energy shortage context, humans are devoting increasing attention to the oceans. Oceans cover over 70% of the Earth’s surface yet remain largely unexplored, making underwater exploration essential for advancing knowledge of marine ecosystems, biodiversity, and deep-sea environments. These efforts provide critical insights into how oceans regulate climate, sustain life, and offer resources such as food and energy. In this context, maintaining a continuous underwater presence is vital for long-term research, conservation, and resource management. Persistent monitoring enables the collection of real-time data on environmental dynamics, marine behavior, and ecosystem health, as well as the detection of subtle or rapid changes driven by climate change, pollution, or anthropogenic impacts such as overfishing [7,8,9,10,11]. Autonomous platforms—including underwater vehicles [12] and sensor-equipped buoys [13]—play a key role in this effort, supporting effective marine resource management and providing early warning systems for natural hazards like tsunamis and harmful algal blooms [14,15]. However, their operational range is often limited by energy autonomy. To address this constraint, energy-efficient control strategies are critical. By optimizing actuator usage, such control laws reduce energy consumption, thereby extending mission durations and expanding the reach of underwater exploration.

In order to minimize energy consumption, several strategies can be found in the literature. In [16], an event triggered sliding mode controller was developed for the depth control of an AUV. This controller updates control inputs only when a triggering condition is met, reducing control update frequency significantly and thereby saving computing and actuation energy. Energy savings of approximately 5% in simulation and approximately 3% in field experiments are reported. A similar event-triggered approach was followed in [17], where dynamic event-triggered fixed-time controllers were designed for multi-AUV systems to achieve coordinated formation or trajectory tracking while minimizing unnecessary control updates.

In [18] a combined depth control strategy was proposed to enable both hovering and efficient low-speed, long-range cruising for AUVs. This strategy alternates between: (1) a water ballast type VBS with a hierarchical architecture-based on-off flowrate controller for stable hovering and large depth changes, and (2) bow and stern fins with propulsion to maintain cruising depth efficiently. Numerical and basin tests demonstrated satisfactory control performance, achieving neglectable steady-state depth error even under model uncertainties. However, steady-state errors emerged in the presence of external disturbances, and no energy consumption data was reported. Regarding energy efficient depth control, in [19] a high-accuracy buoyancy-actuated system (HA-BA) was developed for multimodal underwater vehicles (MUVs), capable of operating as either Argo floats or a Gliders. The HA-BA features a hydraulic variable buoyancy system that uses two drive strategies for floating motions: pumping oil once for rapid ascent and pumping oil multiple times to adjust buoyancy based on floating speed. Simulations suggested a 37% reduction in energy consumption during a deep water to surface ascent using the latter strategy. However, these findings were not experimentally validated as the sea trials focused on evaluating the HA-BA control performance. Energy efficiency was also a focus in [20], where a model predictive control strategy incorporating a quadratic energy term into the cost function (MPC-QE) was developed based on a state-space model for AUVs. The quadratic energy term aimed to reduce energy consumption while minimizing deviations from the reference trajectory and changes in control input. Simulation trials were conducted using step, sinusoidal, and triangular depth references, comparing MPC-QE to conventional MPC. Results showed that MPC-QE reduced energy consumption by 34% for step trajectories and by over 20% for tracking trajectories, even in the presence of significant model uncertainty. However, the approach was not validated through experimental trials. In [21], the depth control of an AUV was simulated using four approaches: propeller-driven control (with a PID controller), hydraulic VBS-driven control (also with PID), and two hybrid strategies combining both. In the first hybrid method, depth is initially stabilized using the propellers, after which the integral term of the PID controller is transferred to the VBS. In the second, both systems operate simultaneously: the VBS with a PID controller and the propeller with a PD controller. A step depth reference from 0.75 m to 1.36 m was used for the simulation trials. Results showed the propeller-only method was the fastest and most energy-efficient. However, the study did not clarify how energy consumption was calculated, and the hydraulic pump efficiency was not disclosed. Energy consumption was also a concern in [22] where a robust controller for an underwater vehicle operating at depths of up to 150 m was developed. This method combined sliding mode control (SMC) for robustness against modeling errors and environmental disturbances with classical optimal control techniques to minimize control effort. During helicoidal trajectory tracking, the controller achieved up to 30% energy savings, albeit with some compromise in tracking accuracy.

In this context, the authors of this paper recently proposed a variable structure depth controller with a constant-amplitude control action. This controller was designed to reduce energy consumption in an underwater sensor platform with a variable buoyancy module (VBM) [23]. The controller activates only when system dynamics drive the vehicle away from the desired depth and deactivates when they naturally guide it back, minimizing unnecessary actuation. Results in [8] show that this approach reduces energy use by an average of 22% compared to the most efficient PID-based alternative, albeit with a trade-off in control performance. The formal proof of stability of the controller was presented in [24] by demonstrating that if the control action remains within specified upper and lower bounds, the system state remains bounded regardless of its initial rest conditions. The study in [24] also highlights how stability regions vary with parameter choices and mission requirements, offering practical guidance for controller tuning. The proposed control law in [24] was shown to ensure formal stability, even under conservative assumptions. Stability analysis is critical for ensuring safe and reliable operation of underwater vehicles in complex marine environments. Without it, control laws may lead to unpredictable behavior, such as instability, oscillations, or mission failure. Stability proofs such as those based on Lyapunov-based methods [25,26,27] provide assurance of safe autonomous operation, enhancing mission success and reducing risks.

It is important to highlight that the control law proposed in [24] is of the switched type, thereby characterizing the overall system as a switched control system. In such systems, the stability analysis is inherently more complex than in non-switched counterparts. This is due not only to the potential need to establish the stability of each individual subsystem, but also to the requirement that the switching between subsystems does not induce instability [28]. A common methodology employed in this context involves the use of multiple Lyapunov functions [28,29,30]. However, this approach presents a significant challenge, as it demands the construction of appropriate Lyapunov functions for each subsystem—an inherently difficult and non-trivial task.

In previous papers [23,24] the controller uses a fixed amplitude control action in the operating regions where it is on. For stability this constant value must be above the one determined by the stability conditions. Since these conditions vary according to the system state, the constant value may be often oversized. To avoid this potential energy waste, the controller proposed in this study uses a variable value that matches the instantaneous stability conditions. Potential energy savings might therefore be obtained. Since the formal proof developed in [24] assumes a constant control action when the controller is on, it is no longer applicable to the one developed in this study. Furthermore, the work developed in this paper also examines how controller parameters and mission requirements influence stability regions and how these regions can be used to estimate the order of magnitude of oscillation amplitude during hovering. It is shown through simulation trials that the proposed controller can further reduce energy consumption compared to two previously developed controllers in [23,24]. From these findings it is also discussed how parameter choices affect energy consumption.

The main contributions of this paper are therefore the following:

- (i)

- a new variable structure controller that further reduces the energy consumption obtained with the controllers in [24]. The proposed controller achieves energy savings of up to 16% when compared to the most efficient controller presented in [24];

- (ii)

- a formal proof of stability for the new controller;

- (iii)

- the newly proposed formal stability proof differs from conventional approaches found in the literature on switched systems, which are typically based on the use of multiple Lyapunov functions [28];

- (iv)

- a procedure to estimate the order of magnitude of the depth error band that can be obtained with the new controller.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 introduces the underwater device model and Section 3 describes the proposed controller. Section 4 presents the formal stability proof, with Section 4.1 outlining the proof and Section 4.2, Section 4.3 and Section 4.4 detailing its key components. Section 5 starts by quantifying stability bounds using a previously developed prototype as a case study and ends by presenting simulation trials. Finally, Section 6 draws the key conclusions of this work.

2. Underwater Device Closed Loop Model

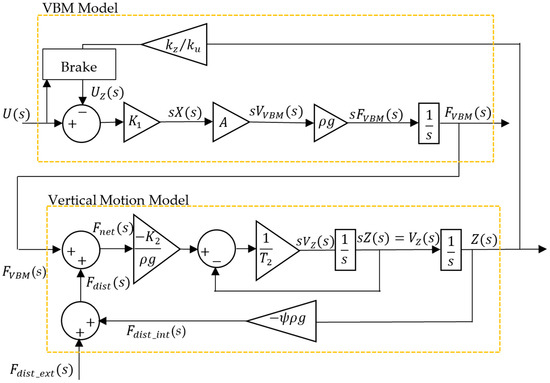

The prototype model used in this work integrates the VBM model with the vertical motion model, as developed in [31]. Given that actuator dynamics are significantly faster than the rest of the system, a reduced-order model, represented in the Laplace domain, is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Prototype reduced-order model.

Figure 1 resumes the model that has already been used in [24]. In this figure, represents the steady-state gain of the actuator’s velocity dynamics, experimentally identified in [32], and , the area of the piston in contact with seawater. The piston position is represented by and piston velocity by . The mechanical brake’s effect on the actuator is represented in the ‘brake’ block of Figure 1. When , the brake is engaged, resulting in an equivalent depth voltage . When , the brake is disengaged, and , reflecting the influence of depth-induced pressure on actuator motion. is the vehicle depth and the ratio , determined in [33], captures the torque exerted on the motor by external pressure forces and the motor’s stall torque at the given voltage.

The net force is the difference between the actual VBM buoyancy force and the total disturbance force , which includes both internal () and external () components.

Parameters and , which characterize the depth dynamics, were identified in [31]. The parameters and represent the water density at 1 atm and the gravitational acceleration, respectively. Parameter accounts for the variation in water density with depth and the volume loss per meter due to hull deformation with pressure. A method for estimating this volumetric loss was presented in [23].

The model is governed by the following differential equations:

where is the vertical speed of the prototype. It will be considered, without loss of generality, that the control purpose is to drive the depth error to . If control action is switched between two states , where

with being a variable control action to be described later in Theorem 2 of Section 4.2.

Then the closed loop dynamics are described by:

where the state is defined as and and defined as:

3. Controller Description

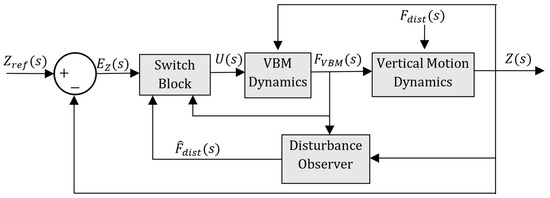

The controller presented in this work has a similar structure to the one presented in [23,24] and will therefore only be briefly presented in the following. Both controllers attempt to minimize consumption of the VBM by leveraging the system’s inherent dynamics to favor low energy depth control. This approach activates the VBM whenever the underwater device deviates from its target depth. Conversely, if the device moves in a way that reduces the depth error, the VBM is deactivated. As a result, the VBM is expected to remain off for a substantial portion of the mission, leading to significant energy savings. Figure 2 presents a block diagram of the controller structure. It should be noticed that while can be obtained by measuring the piston position , the disturbances are estimated using a disturbance observer, as presented in [23]. Further details about the controller and the observer can be found in [23,24].

Figure 2.

VSC system block diagram.

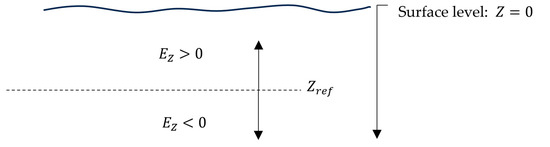

In Figure 2, is the target depth reference. The depth control error and its derivative can be written as (7) and (8), respectively, since is assumed to be constant. Figure 3 presents the system model notation.

Figure 3.

System model notation.

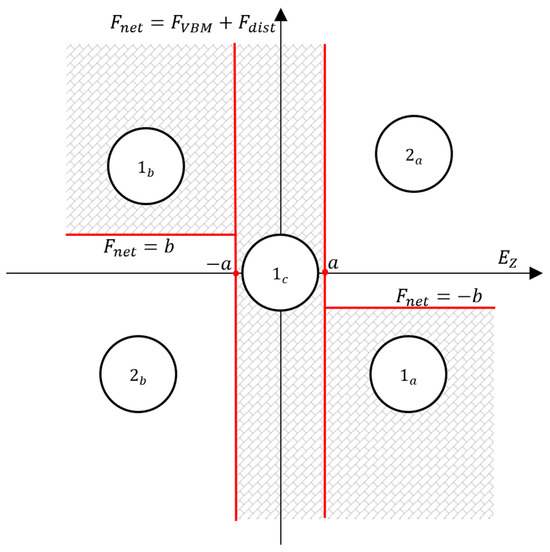

The switch block, described below, determines whether the VBM should be turned OFF—by engaging the brake and applying control law (3) with —or turned ON—by disengaging the brake and using control law (3) with . Figure 4 illustrates the decision-making process of the switch block.

Figure 4.

Schematic of the switch block decision process.

In the shaded areas of the schematic in Figure 4, the VBM is switched OFF (corresponding to in Equation (3)), while in the unshaded regions, it is switched ON (). Specifically, the VBM is OFF in regions 1a, 1b, and 1c, and ON in regions 2a and 2b. To account for disturbances, the net force () is represented on the vertical axis of the schematic.

Table 1 presents the different switch block decisions and control action according to each region in the schematic of Figure 4.

Table 1.

Switch block decision table.

The controller parameters and in Table 1 are strictly positive constants that are used by both the controller developed in [24] and by the one presented in this paper. The two controllers differ on the control action used. The controller presented in [23,24] uses a constant-amplitude control action, , and therefore can be referred to as a variable structure controller with a constant-amplitude control action (). The controller presented in this work is similar but uses a variable-amplitude control action (), designed to be as low as possible while keeping the system stable. As will be shown, this control strategy further reduces energy consumption. This controller will be referred to as , and the formal proof of its stability will be presented in the following sections.

4. Proof of Stability of the Closed-Loop System

4.1. Outline of the Proof of Stability

Section 4 will demonstrate that system (4), using control action (3) and the switching strategy from Table 1 is stable in the Lyapunov sense [34] for constant depth references and constant external disturbances .

The proof of stability of the controller rests upon three stability conditions:

- For system (4): if is bounded, then are also bounded;

- For system (4) with control action (3) and the switching decision presented in Table 1: when the system (4) is in region 2a, and when the system is in region 2b, ;

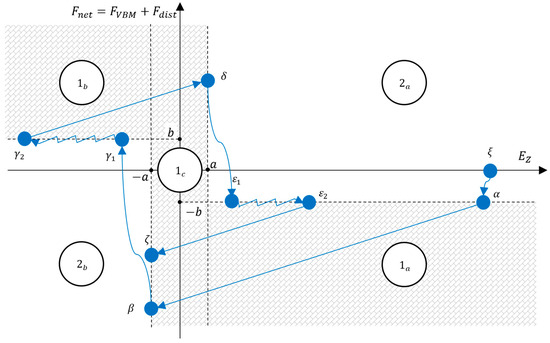

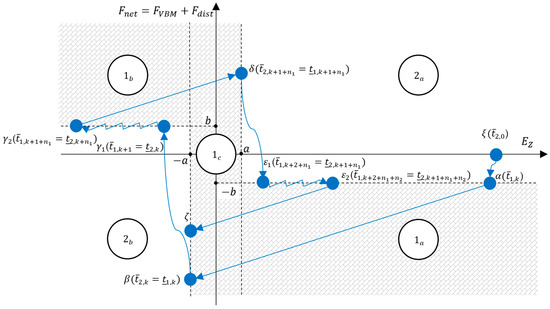

- Using the control law presented in Section 3, and as long as condition 2 is satisfied: starting from an arbitrary state such that , , , where is an arbitrary maximum depth (typically the rated depth of the vehicle), the system performs a cyclical sequence S, traversing points of Figure 5, such that the following conditions are met:

Figure 5. Sequence of states in the plane.

Figure 5. Sequence of states in the plane.- and ;

By satisfying conditions 3a and 3b above, it follows that the absolute values in both and are bounded. From condition 1, the boundedness of implies that is also bounded. From Equation (7), if is bounded, is also bounded. Finally, from (1) and assuming constant external disturbances, the boundedness of and ensures is also bounded. In this work, it is assumed that remains constant, given that, under typical operating conditions, disturbances such as fouling or salinity variations occur at sufficiently slow rates to be approximated as constant. Wave action is assumed to primarily affect depth measurement accuracy rather than buoyancy, as depth is commonly sensed via pressure sensors. Vertical currents may influence the buoyancy force, but, except in highly dynamic shallow waters, they are not expected to exhibit rapid variations. Furthermore, if these disturbances exhibit abrupt transitions at infrequent time instants, the corresponding time-derivatives are non-zero only at those particular time instants. Consequently, such behavior does not compromise system stability. It is therefore shown that satisfying conditions 3a and 3b ensures that the state of Equation (4) remains bounded in the Lyapunov sense [34]:

4.2. Proof of Stability Condition 1

The proof of stability condition 1 rests on Theorem 1. The proof of Theorem 1 has been detailed in [24], and the following sections present the proof of the two remaining stability conditions. Theorem 1 is presented below for convenience.

Theorem 1.

For the system defined by Equation (4) and by the block diagram in Figure 1, if is bounded, is also bounded.

4.3. Proof of Stability Condition 2

Theorem 2.

For the system represented by (4), the variable structure control action of Equation (3) with the switching decision block described in Table 1 ensures that when the system (4) is in region 2a, and when the system (4) is in region 2b, , with as long as Equation (10) is satisfied.

Proof of Theorem 2.

Consider region , where . In this case, to ensure that the system moves out of this region, it is necessary to impose In this work it will be ensured that so that a minimum time rate is guaranteed. From the block diagram of Figure 1, the value of can be written, in the Laplace domain, as:

So, the Laplace transform of time derivative can be written as

To ensure that , the condition presented in Equation (13), written in the time domain, must be met:

Since at region , according to (3), , and since in region , , it follows that . Replacing the value of in Equation (13), and recalling that external disturbances are considered to be constant, Equation (14) can be achieved.

Consider now region , where . In this case, to ensure that the system moves out of this region, For the same reason of region 2a, it will be ensured that . In order to ensure that , Equation (12) can be used to reach Equation (15):

Since at region , according to (3), , and since in region , , then . Replacing in Equation (15), and recalling that external disturbances are considered to be constant, leads to Equation (16).

Conditions (14) and (16) can be written, in a compact form, as in Equation (10). Therefore, it is shown that control law (3) with given by (10) and using the switching decision law presented in Table 1 ensures that when the system (4) is in region 2a, and when the system (4) is in region 2b, . Condition 2 of Section 4.1 is therefore satisfied. □

4.4. Proof of Stability Condition 3

4.4.1. System Trajectory Description

Let be a switching sequence associated with the switched system (4), the set of switching times be defined by and the interval of completion be defined as the set of time intervals during which subsystem is active:

where

and

Consider now Figure 6, showing a sequence of switching actions and the corresponding states in the plane.

Figure 6.

A sequence of switching actions and the corresponding states in the plane.

As detailed in Section 4.1, it will be shown in the following that starting from point , the system will evolve to point crossing , , , and in this order. The system then enters a cyclic sequence , such that conditions 3 of Section 4.1 are met.

For that purpose, the following results derived from the block diagram of Figure 1 will be used:

And, since is considered to be constant,

At the initial point ), it is considered that the system has zero velocity, zero net buoyancy and an initial arbitrary error . The initial point can be defined as:

The change in between points and , can be determined integrating Equation (21) with :

Developing Equation (25):

Since , and

Given that and as has been shown in [24], the sign of and are the same, it follows that point can be defined as:

Please notice that in the first cycle but in subsequent cycles . This is because point of one cycle is point of the following cycle and , as will later be shown. Since and using Equation (20),

The change in between points , , and , can be determined integrating Equation (23) with :

The change in between points , , and , can be determined integrating Equation (21) with .

Since and

Since and between and , the point can therefore be defined as:

The change in between points and , can be determined integrating Equation (21) with :

Developing Equation (34) leads to:

Since and considering (32):

Equation (36) expresses the necessary time for the system to move from to . From the block diagram of Figure 1:

where , and . Since in this region

The expression for the depth velocity between and is thus obtained by solving Equation (37):

To find the depth expression, (39) must be integrated.

After integration, (40) leads to:

Since at ,

Rearranging Equation (42) leads to:

Equation (43) defines the depth at as a function of the depth at and the vehicle depth dynamics. To find the depth error, Equation (7) should be considered:

Rearranging Equation (44)

Considering from (32) and from (36)

The depth error at can therefore be given by:

Equation (47) can be rewritten as:

with

Between and , the system is accelerated when and is decelerated when . The velocity when is positive and may or may not become negative when . The point can therefore be defined as:

If at the velocity is positive, the system will undergo a particular behavior between points and . When the system enters infinitesimally at , the control action is , which makes according to (20). Since is negative, will increase and so does the force magnitude factor due to . This leads to a decrease in the net force, and the system is pushed towards , causing the control action to turn on. This will increase the net force, causing the system to be moved again towards . So, in this situation, the system undergoes a switching phase with switchings between and . This behavior will occur until the vehicle is fully decelerated, making the velocity to change sign from positive to negative. Also, since , at this point, the sign of changes from negative to positive. When this happens, point is reached. Since between and the average value of is constant, the relation between and can be determined, from the block diagram of Figure 1, by:

The solution to the differential Equation (51) is:

where is the depth velocity at . To obtain the expression for depth when time varies between and , expression (52) is integrated, leading to:

In (53) is the depth at point . The point occurs when there is change in the sign of the velocity in (52):

The time instant is therefore given by:

Replacing (55) in (53) leads to:

Considering Equation (7) leads to:

If at the velocity is zero, then according to (57), , which means points and are coincident. If is negative, then (57) is no longer valid since no switching occurs. The depth error in expression (57) can also be expressed as:

where is the change in depth error between and , given by:

Expression (58) is valid when and switching occurs. On the other hand, since points and are coincident when , Equation (58) can take a more general form:

where is a parameter that expresses the occurrence of switching at state :

Point can therefore be defined as:

From point until point , is positive, so is negative (Equation (8)). Thus, the force due to the vehicle deformation decreases, since becomes smaller, and since is constant, the value of increases (Equation (20)) until the system reaches point .

The change in between points , , and , can be determined integrating Equation (21) with :

Since Equation (63) can be rewritten as:

The point can therefore be defined as:

The change in between points and , can be determined integrating Equation (21) with :

Developing (66) leads to:

Since and given (64):

Equation (68) expresses the necessary time for the system to move from to . From the block diagram of Figure 1:

where , and . Since in this region

Integrating differential Equation (69), the expression for the depth velocity between and is thus:

To find the depth expression, (71) must be integrated.

The solution of Equation (72) is given by:

Since at ,

Rearranging Equation (74),

Equation (75) defines the depth at as a function of the depth at and the vehicle depth dynamics. To find the depth error, Equation (7) should be considered:

Rearranging Equation (76),

Considering from (64) and from (68)

The depth error at can therefore be given by:

Equation (80) can be rewritten as:

With

Between and , the system is accelerated when and is decelerated when . The velocity in region 2a when is negative and may or may not become positive when . The point can therefore be defined as:

If at the velocity is negative, the system will undergo a particular behavior between points and . When the system enters infinitesimally at , the control action is , which makes according to (20). Since is positive, will decrease and so does the force magnitude factor due to . This leads to an increase in the net force, and the system is pushed towards , causing the control action to turn on. This will increase the net force, causing the system to be moved again towards . So, in this situation, the system undergoes a switching phase with switchings between and . This behavior will occur until the vehicle is fully decelerated, making the velocity to change sign from negative to positive. Also, since , at this point, the sign of changes from positive to negative. When this happens, point is reached. Since between and the average value of is constant and equal to , the relation between and can be determined, from the block diagram of Figure 1, as:

The solution to the differential Equation (83) is:

Integrating (84):

In (85) is the depth at point . The point occurs when the velocity in (84) changes its sign:

Rewriting (86):

Plugging (87) into (85):

Rearranging Equation (88) leads to:

Considering Equation (7), the depth error at point is given by:

If at the velocity is zero, then according to (90), , which means points and are coincident. If is positive, then (90) is no longer valid since no switching occurs. The depth error in (90) can also be expressed as:

where is the change in depth error between and , is given by:

Expression (91) is valid when and switching occurs. On the other hand, since points and are coincident when , Equation (91) can take a more general form:

where is a parameter that expresses the occurrence of switching at state :

Point can therefore be defined as:

The change in between points , , and , can be determined by integrating Equation (21) with .

Since

Since , and replacing this value in (97), leads to:

Point can therefore be defined as:

With all the points in the diagram defined, conditions 3 of Section 4.1 can finally be demonstrated to exist. Condition 3a requires that and . From Figure 6, by definition. The demonstration that will be divided into two parts:

- (i)

- To demonstrate that ;

- (ii)

- To demonstrate that ;

By demonstrating that and , it logically follows that . The conditions for each part will be detailed in the following sections.

4.4.2. Detailing of Condition 3a: Part i

The condition for part i is:

Which can also be expressed as:

From (48)

Since

Considering , (49) and (59)

Expression (104) defines the minimum value of that satisfies (100). However, it is not easy to extract direct information from this expression. Therefore (104) will be quantified in a later section.

4.4.3. Detailing of Condition 3a: Part ii

The condition for part ii is:

From (93) and (80) and considering

Considering , (81) and (92)

Rewriting (108) with absolute values:

Expression (109) defines the minimum value of that satisfies (105). However, it is not easy to extract direct information from this expression. Therefore (109) will be quantified in a later section.

4.4.4. Detailing of Condition 3b

For condition 3b to be satisfied, . The first condition is ensured by the definition of points and . For the second condition to be met and since and :

From (32) and (98):

which leads to

The result from expression (112) means that as long (104) and (109) are satisfied, then and is therefore bounded, meeting the requirements of condition 3b.

4.5. Quantifying the Stability Conditions

Since (104) defines a lower bound for , it is interesting, from a conservative approach, to find the maximum value for its right side. To estimate this maximum value, a few assumptions will be made:

- From to , , for the purposes of estimating . Since is the maximum magnitude value takes between and , this will contribute to an overestimation of , leading to a conservative estimation of ;

- At , it will be considered the velocity is . Between and , increases from to . From assumption 1, is the steady-state velocity at . As such, from to , the velocity will decrease. Therefore, considering contributes to an overestimation of , leading to a conservative estimation of .

Considering the block diagram of Figure 1.

This means that maximum depth velocity occurs at steady-state, in which:

From assumption 1,

From (32):

Expression (104) then becomes:

Rearranging (117):

Expression (118) constitutes an overestimation of (104) so that (100) holds.

Regarding (109), since it defines a lower bound for , it is interesting to find the maximum value for its right side. To estimate this maximum value, a few assumptions will be made:

- From to , , for the purposes of estimating . Since is the maximum magnitude value takes between and , this will contribute to an overestimation of , leading to a conservative estimation of ;

- At , it will be considered the velocity is . Between and , decreases from to . From assumption 3, is the steady-state velocity at . As such, from to , the velocity magnitude will decrease. Therefore, considering contributes to an overestimation of , leading to a conservative estimation of .

Using the maximum depth velocity at steady-state determined in Equation (114) and considering assumption 3,

From (64):

In terms of absolute values

Expression (109) then becomes:

Rearranging (122)

Since from (100), , in a worst-case scenario, =. Therefore, (123) becomes:

Expression (124) constitutes an overestimation so that (105) holds. Notice that expression (124) is equal to (118), which ensures that (100) holds. This means that if (118) (or (124)) are satisfied, then (100) and (105) are also satisfied so that condition 3a is ensured. In other words,

Consequently, (118) and (124) can be written as:

where is an overestimation of represented by the right side of (124). Equation (126) will therefore be the basis of the controller stability analysis performed in the next section.

5. Controller Stability: Case Study

5.1. Stability Regions

In order to present a case study of the application of the results obtained in this work to a prototype, in this section expression (124) is used to determine the stability regions according to the depth error at point , . The system model parameters for these expressions are unique to the real system being modelled. For the purposes of this work, the prototype developed in [32] with the parameters fully determined in [23] was considered. The prototype, whose model can be described by the block diagram of Figure 1, uses a diaphragm sealed piston, driven by a DC motor, to change buoyancy (the reader is referred to [23,32] for further details).

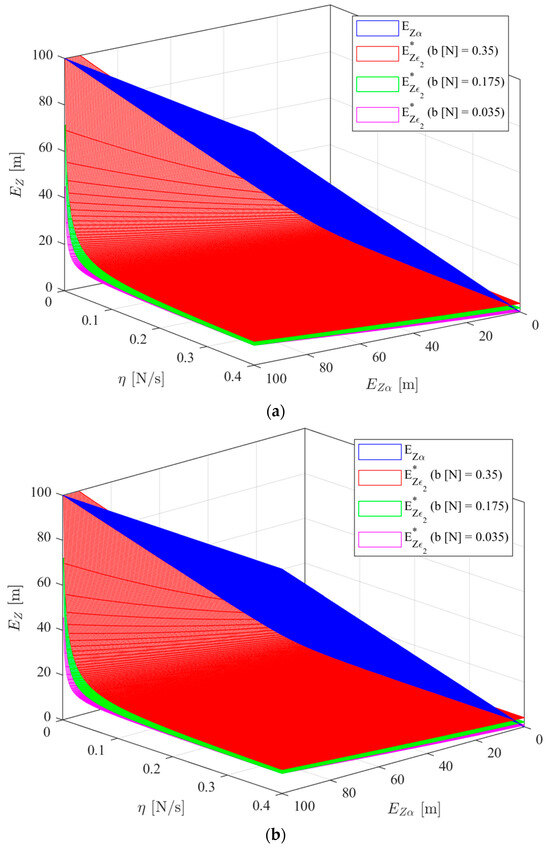

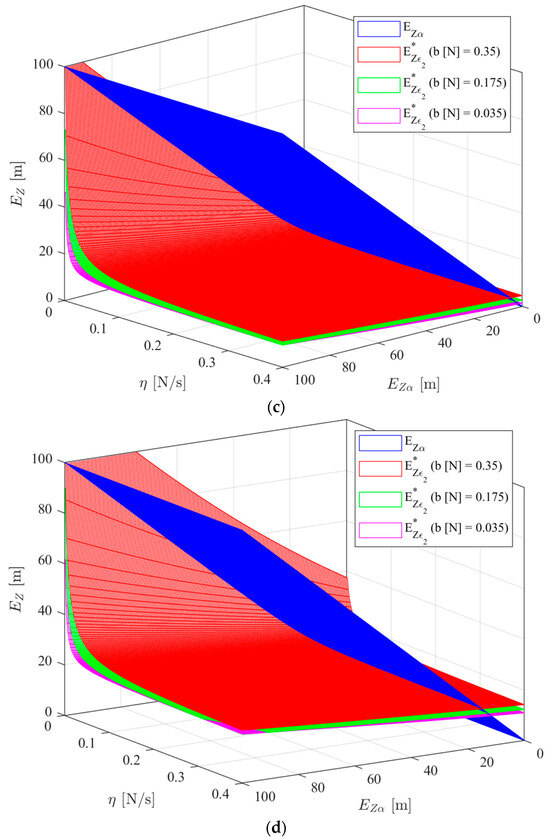

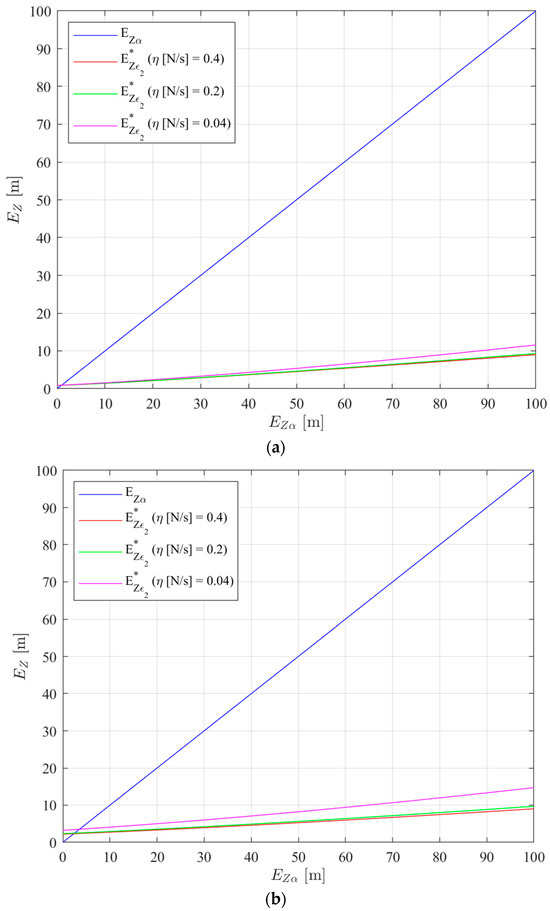

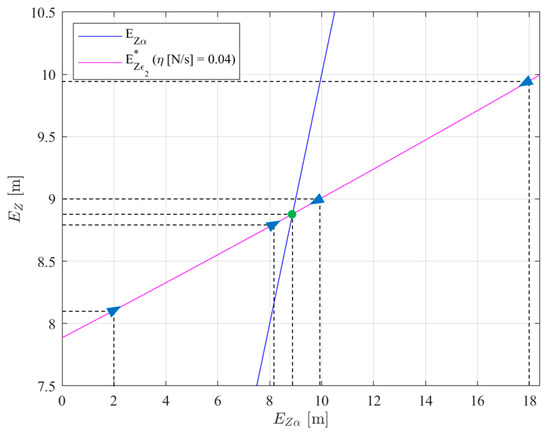

The system model parameters are presented in Table 2. Figure 7 presents three 3D plots of and as a function of and . By comparing the values of and , a direct assessment of expression (126) can be made. Different discrete values of the parameters and were used in the plots of Figure 7. Parameter defines the depth band inside which the controller is turned off. Increasing it will tend to decrease energy consumption while tending to cause an increase in the depth control error. Parameter defines a net force () layer inside which the controller remains turned ON although it could already be turned off. Increasing this parameter tends to increase energy consumption while preventing determination errors to affect the controller behaviour. The chosen values of correspond to 0.1%, 0.5%, 1% and 10% of the prototype maximum depth and the chosen values of correspond to 1%, 5% and 10% of the maximum buoyancy. Parameter defines how fast the net force is changed: increasing it will tend to increase energy consumption while tending to decrease the time the system takes to react. The range for was chosen based on . From the block diagram of Figure 1, considering , . Given the battery voltage of , the maximum voltage considered was , to account for voltage drops in the electronics. As such, the considered range for is N/s. In Figure 7, the regions where the pink, red and green surfaces () are below the blue plane () are the regions where expression (126) is satisfied and, therefore, the system performs a convergent trajectory as explained below. When the pink, red and green surfaces are above the blue plane, the prototype will move away from the target depth reference and increase . This will occur until is big enough so that (126) is again satisfied. This means the system is bounded and therefore Lyapunov stable as described in Section 4.1. From Figure 7, the impact of the parameters , and on the system stability can be evaluated. Increasing parameter leads to an increase in the minimum required value of to satisfy (126). This result is expected since increasing means expanding the region where the controller is turned OFF. Increasing also leads to an increase in the minimum required value of to satisfy (126), but for a different reason. Increasing means that on the diagram of Figure 6 the system will reach point with a higher net force magnitude, leading to an increase in velocity magnitude at point according to Equation (121). Therefore, the system reaches with a higher velocity according to assumption 3, leading to a higher depth error at . On the other hand, increasing leads to a decrease in the minimum required value of to satisfy (126). This is to be expected since it means it takes less time for the system to move from to (or from to ), meaning the switching phase starts earlier, at a lower depth error magnitude at (or ). This is why, as can be seen in Figure 7, for very low values of , the values of increase considerably. In Figure 8, sections of Figure 7b are presented: three 2D plots of and as a function of for an of 0.5% of the maximum depth reference and for the same discrete values of parameters and . The chosen values for correspond to 10%, 50% and 100% of .

Table 2.

System model parameters.

Figure 7.

Plot of and as functions of and for particular values of b: (a) a = 0.1 m; (b) a = 0.5 m; (c) a = 1 m; (d) a = 10 m.

Figure 8.

Plot of and as functions of for a = 0.5 m and for particular values of : (a) b = 0.035 N; (b) b = 0.175 N; (c) b = 0.35 N.

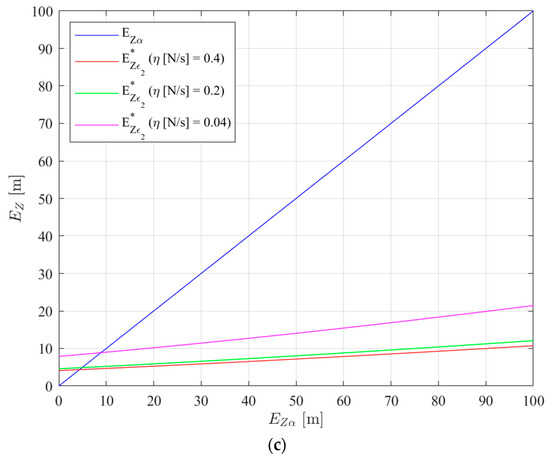

In Figure 9, a close-up of Figure 8c for N/s, = 0.5 m and = 0.35 N is presented. As an example, consider three consecutive switching sequences (S1, S2 and S3) the system might undergo. Assume that the estimation is perfect () and that switching sequence S1 starts at point with , represented by the right-most triangular marker in Figure 9. In this situation, . This means that after performing the switching sequence S1, the depth error reduces from to Point can now be seen as point of switching sequence S2. In this situation, . This means that after performing switching sequence S2, the depth error reduces from to Point can now be seen as point of switching sequence S3. In this situation, , close to the intersection between the two curves of Figure 9. A similar process can be followed by starting another different sequence S1, at point with , represented by the left-most triangular marker in Figure 9. In this situation, . This means that after performing switching sequence S1, the depth error increases from to Point can now be seen as point of the new switching sequence S2. In this situation, . This means that after performing switching sequence S2, the depth error increases from to Point can now be seen as point of the new switching sequence S3. In this situation, . It is clear from these examples that whether the system starts to the left or to the right of the intersection between the curves of Figure 9, it always moves in the direction of the intersection. This means the depth error is bounded. Moreover, the information provided in Figure 7 and Figure 8 allows the estimation of the order of magnitude of the depth error bounds around which the system oscillates. These bounds are given by the intersection between and . In the next section a numerical example will be presented.

Figure 9.

Close-up of Figure 8c.

5.2. Simulation Trial

In this section, the proposed controller is simulated and compared to controller 7b of [33] and to the controller proposed in [24]. In [33], the authors proposed a cascaded control strategy consisting of a depth controller and a volume controller for the VBM. The control structure 7b led to the smallest energy consumption and was therefore selected for datum comparison in this work. In [23,24] a variable structure controller with a constant control action was presented and it’s stability was proven. A particular version of this controller was simulated in [23] and its energy consumption was lower compared to the lowest energy consuming controllers from [33]. As such, the controllers used for the simulation trial are:

- Controller : a cascaded I-PD/PI control scheme, with the I-PD depth controller in the outer loop and the PI volume controller with a deadband in the inner loop;

- Controller : a variable structure controller with a constant-amplitude control action ;

- Controller : the variable structure controller presented in this work, with a constant net force time rate

Controllers and require a disturbance observer, presented in [23], to provide an estimation of the net force acting on the prototype. The parameters of controller 7b are presented in Table 3, whereas the VSCs and observer parameters are shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Controller 7b parameters used in the simulation trial.

Table 4.

VSC and observer parameters used in the simulation trial.

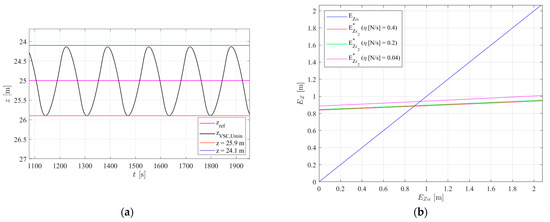

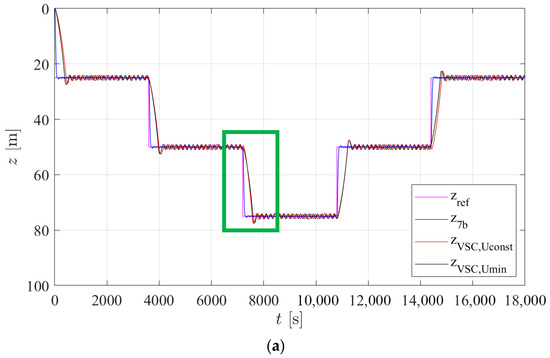

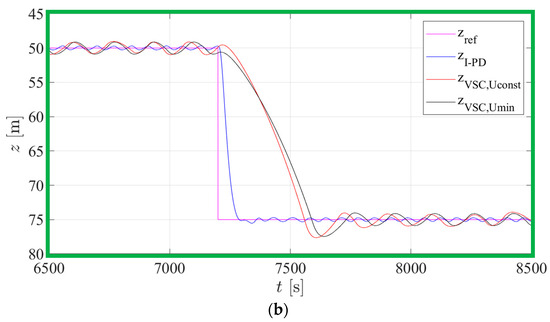

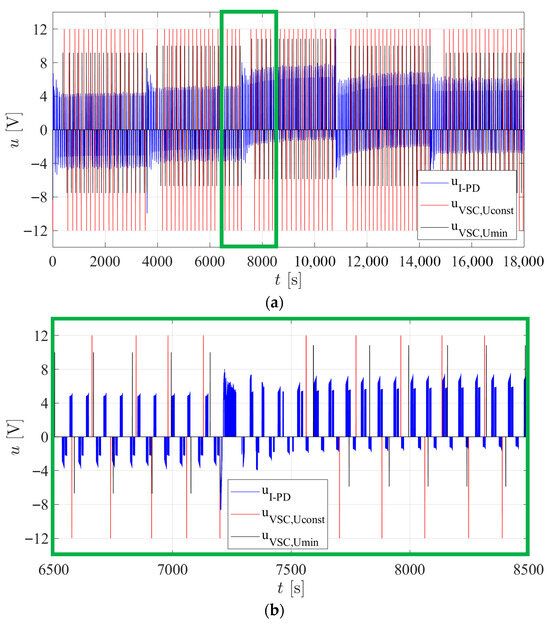

Controller 7b tuning conditions are described in a previous paper by the authors [33], where several PID based structures and parameters were heuristically tuned to achieve low energy consumption. The controller parameters leading to the lowest energy consumption are the ones presented in Table 3. The choice of parameters for the was based on the charts presented in [24]. In particular, the controller voltage was chosen so that inside the stability regions the range for the parameter is . The same values were used for parameters and on the , and the average value of was considered. In this manner, a fair comparison can be made between both controllers. The simulation trial conducted in Matlab Simulink corresponds to a type 1 test as described in [33]: a target depth consisting in a set of five equal amplitude steps, without external disturbances. The system model was implemented with quantization of the measured variables and to account for sensor resolution as well as Zero Order Holds (ZOH) with a sampling time of 0.1 s (corresponding to the real system sampling time) to simulate the holding of control actions and measured variables calculated between sampling instants. The solver used was Matlab ode45, based on an explicit Runge–Kutta (4,5) formula, the Dormand-Prince pair. The simulations were run with a variable time-step. The solver uses a relative error tolerance of 10−3. Further details of the implementation can be found in [33]. Figure 10 presents the prototype depth for the complete simulation trial and a close-up of the region marked with a green rectangle. In Figure 11, the control action is shown for the corresponding time intervals of Figure 10. Figure 12 exhibits the energy consumption.

Figure 10.

Depth in Simulation Trial: (a) full simulation; (b) close-up.

Figure 11.

Control action in simulation trials: (a) full simulation; (b) close-up.

Figure 12.

Simulation Trials: energy consumption.

From Figure 10 it is clear that controller 7b is faster than both VSCs. This comes at a price of a bigger energy consumption as can be seen in Figure 12. Comparing only the VSCs, they are similarly fast but the is less energy demanding. The differences in energy consumption between the three controllers can be explained with the help of Figure 11. Controller 7b uses a control action with a smaller amplitude than both VSCs, but at a much higher frequency. In contrast, the VSCs operate at a similar frequency: maintains a fixed amplitude of 12 V, while adjusts its amplitude to the minimum required by (10), leading to smaller amplitudes than . It should be noticed that the actual amplitude of the control action is larger when increasing buoyancy since the external water pressure opposes piston movement. Conversely, when decreasing buoyancy, the surrounding water pressure aids the piston return motion, so a lower voltage is sufficient. As expected, Figure 11 shows this asymmetry becomes more pronounced with depth due to the higher pressure.

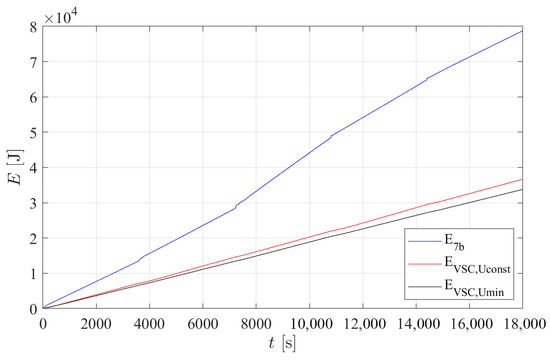

Considering the with the parameters described in Table 3, the chart from Figure 8a is applicable. Figure 13 shows a close-up of Figure 10 and Figure 8a.

Given that for the simulation trial N/s was used, the corresponding curve is located between the green and red curves of Figure 13b. The intersection between this curve of and the blue line gives an estimation of the maximum depth error band that can be obtained. As such, the system should tend to oscillate around the target depth with an amplitude of the same order of magnitude of the value given by this intersection. From Figure 13b, this value is m, so when the target depth is 25 m, this corresponds to a minimum value of z = 24.1 m and a maximum value of z = 25.9 m, as represented by the red and blue lines of Figure 13a. This result matches the one presented in Figure 13a, where the oscillation has an amplitude of about 0.9 m. This shows how the charts from Figure 8 can be used to estimate the controlled system oscillation amplitude.

In order to assess the energy consumption of the controllers with different values of and , additional simulation trials were conducted. The energy consumption results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Energy consumption of the VSCs according to the chosen parameters.

The results from Table 5 show that absolute energy consumption increases with the parameter . This is to be expected since it means that the controllers must perform larger buoyancy changes. On the other hand, it is also clear that increasing the value of parameter leads to a reduction in absolute energy consumption at the cost of a larger depth error band. This is also not surprising since increasing means increasing the admissible depth error and, as such, the amount of time the system is turned off also increases. Another important result is that for comparable parameters, the always lead to less absolute energy consumption than the . This effect is particularly evident for small values of , where up to 16% energy savings were achieved. The relative reduction in energy savings percentage for higher values of can be explained by the fact that having a wider depth error band reduces the control action’s ON time, thereby diminishing the relative benefit of the proposed controller. Finally, energy savings percentage also generally increases with the increase in parameter . This may show that using a smaller control action for longer time (VSCUmin) as opposed to using a larger control action for shorter times (VSCUconst) is beneficial as it increases the relative advantage of the proposed controller.

The performance of each controller in maintaining the sensor platform’s suitability for underwater acoustic measurements was assessed. The results are also presented in the two last columns of Table 5. This assessment focused on measuring how long each controller remained inactive for periods of at least 60 s. The two last columns of Table 5 summarize the off-time for each trial and controller, as a percentage of the overall trial durations. The results show that in most cases where the error band is equal to 0.1 m, the controller is not able to be off more than 60 consecutive seconds in a significant part of the mission. This is expected since for tighter depth error bands, the controller must turn on more frequently. However, if the error band is equal or higher than 0.5 m (a typically accepted error value in many missions), the controller is off most of the time. There also appears to be an increase in the 60 consecutive seconds period that the controller is off when b is decreased. This is consistent with the energy decrease noticed when b is reduced. Furthermore, there were no notable differences in inactive periods between using a constant-amplitude control action and a variable one. These findings highlight the strong suitability of the controller developed in this study for scenarios that demand minimal acoustic emissions.

Lastly, to assess the influence of parameter on energy consumption, a few more simulations were conducted for different values of . The results are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Energy consumption of the VSCUmin for different values of .

The results presented in Table 6 show that parameter contributes to increase energy consumption. This is expected since to achieve a higher value of , a higher value of is required.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a new variable structure controller with a variable control action designed to minimize energy consumption in underwater vehicles and platforms using variable buoyancy actuation. A formal proof of stability is provided, demonstrating that if the initial conditions are within specified depth error bounds, the system state remains bounded. These bounds can be quantified for a given system, offering practical guidance for selecting controller parameters. The proposed approach was applied to a previously developed depth-controlled sensor platform using a validated system model while accounting for physical constraints. Results confirm that the control law is implementable in such a prototype, despite the highly conservative approach considered.

This study further explores how stability regions are affected by controller parameters and mission requirements. It also shows that the stability conditions derived can be used to estimate the amplitude of oscillations during hovering tasks. Simulation trials were conducted to validate the proposed controller (VSCUmin), comparing it with two previously developed controllers: a constant control action VSC (VSCUconst) and a controller from the PID family (a cascaded I-PD/PI). The variable structure controllers exhibit a slower response than the I-PD/PI but with the benefit of less energy consumption. Moreover, the VSCUmin achieves up to a 16% energy reduction when compared to the VSCUconst. The analysis also highlighted how parameter choices impact the energy consumption of the VSCUmin, particularly in comparison to VSCUconst. These findings provide a foundation for controller tuning with specific mission requirements. Future work will involve the experimental validation of the controller through pool and sea trials and extension of the stability proof to account for variable external disturbances. Also, the necessary changes regarding system parameters for electro-hydraulic and other actuators will be explored, as well as a comparison with other controllers, such as Linear Quadratic Regulators and Model Predictive Control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F.C., J.B.P., F.G.d.A. and N.A.C.; methodology, J.F.C., F.G.d.A. and N.A.C.; software, J.B.P.; investigation, J.F.C., J.B.P., F.G.d.A. and N.A.C.; writing, J.F.C. and J.B.P.; writing—review and editing, J.F.C., J.B.P., F.G.d.A. and N.A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported through the grant LAETA—UIDB/50022/2020—from the “Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia”, which the authors gratefully acknowledge.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| Depth deadband [m] | |

| rea of the piston in contact with sea water [m2] | |

| band [N] | |

| Depth controller | |

| Volume controller | |

| Volume dead band parameter for [m3] | |

| Energy spent by [J] | |

| Energy spent by [J] | |

| Depth control error [m] | |

| Depth control error at state [m] | |

| Overestimation of | |

| System model state functions | |

| Total disturbance forces [N] | |

| External disturbance forces [N] | |

| Internal disturbance forces [N] | |

| Difference between and [N] | |

| at state i [N] | |

| Variable buoyancy module force [N] | |

| Acceleration of gravity [ms−2] | |

| Variable buoyancy module linear model steady-state gain [ms−1V−1] | |

| Vertical motion linear model steady-state gain [ms−1m−3] | |

| Integral gain of [V/(m3s)] | |

| Proportional gain of [V/m3] | |

| Derivative gain of [m3/(ms−1)] | |

| Integral gain of [m3/(ms)] | |

| Proportional gain of [m3/m] | |

| Disturbance observer proportional gain [Nm−1] | |

| Disturbance observer derivative gain [Nsm−1] | |

| Parameter relating the depth and the equivalent depth voltage [Vm−1] | |

| p | Water pressure [Pa] |

| System state boundaries in the Lyapunov sense | |

| Switching sequence | |

| Time [s] | |

| Switching time instant for subsystem j [s] | |

| Switching time instant when subsystem i is switched on for the kth time [s] | |

| Switching time instant when subsystem i is switched off for the kth time [s] | |

| Variable buoyancy module linear model time constant [s] | |

| Vertical motion linear model time constant [s] | |

| Control action [V] | |

| Variable-amplitude control action [V] | |

| Variable structure controller control action [V] | |

| Equivalent depth voltage [V] | |

| Depth velocity [ms−1] | |

| Depth velocity at state i [ms−1] | |

| Constant-amplitude variable structure controller | |

| Variable-amplitude variable structure controller | |

| System state vector | |

| Piston position [m] | |

| Vehicle depth [m] | |

| Vehicle depth at state i [m] | |

| Maximum vehicle [m] | |

| Depth reference [m] | |

| α, β, γ1, γ2, δ, ε1, ε2, ζ, ξ | System states |

| Change in depth error between states i and j | |

| Change in depth error between and | |

| Parameter that expresses the occurrence of switching at state [0, 1] | |

| Parameter that expresses the occurrence of switching at state [0, 1] | |

| controller parameter [] | |

| Hull loss of volume per meter depth [m3m−1] | |

| Water volumetric mass [kgm−3] | |

| Set of time intervals during which subsystem is active | |

| Time derivative of | |

| Maximum value of | |

| Absolute value of | |

| Norm of vector |

References

- Choi, M.-I.; Kang, B.; Lee, S.; Park, S.; Seon Beck, J.; Hyeon Lee, S.; Park, S. Empirical study on optimization methods of building energy operation for the sustainability of buildings with integrated renewable energy. Energy Build. 2024, 305, 113908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonsale, A.N.; Yashpal; Purohit, J.K.; Pohekar, S.D. Renewable & alternative energy sources for strategic energy management in recycled paper & pulp industry. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2021, 16, 100857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudy-Laskowska, K.; Chudy, M.; Pisula, J.; Pisula, T. Taxonomical Analysis of Alternative Energy Sources Application in Road Transport in the European Union Countries. Energies 2025, 18, 4228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viadero-Monasterio, F.; Meléndez-Useros, M.; Zhang, H.; Boada, B.L.; Boada, M.J.L. Signalized Traffic Management Optimizing Energy Efficiency Under Driver Preferences for Vehicles With Heterogeneous Powertrains. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025, 71, 3454–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulraj, T.; Obulesu, Y.P. Machine learning-based approach for reduction of energy consumption in hybrid energy storage electric vehicle. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioshchikhes, B.; Frank, M.; Weigold, M. A Systematic Review of Expert Systems for Improving Energy Efficiency in the Manufacturing Industry. Energies 2024, 17, 4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, R.K. Marine Biodiversity, Climate Change, and Governance of the Oceans. Diversity 2012, 4, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morato, T.; González-Irusta, J.-M.; Dominguez-Carrió, C.; Wei, C.-L.; Davies, A.; Sweetman, A.K.; Taranto, G.H.; Beazley, L.; García-Alegre, A.; Grehan, A.; et al. Climate-induced changes in the suitable habitat of cold-water corals and commercially important deep-sea fishes in the North Atlantic. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 2181–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.A.; Bett, B.J.; Gates, A.R.; Heimbach, P.; Howe, B.M.; Janssen, F.; McCurdy, A.; Ruhl, H.A.; Snelgrove, P.; Stocks, K.I.; et al. Global Observing Needs in the Deep Ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthwick, A.G.L. Marine Renewable Energy Seascape. Engineering 2016, 2, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon, F.; Seymour, Z.; Monteiro, Z.; Graham, R. Spatial ecology of a newly described oceanic manta ray population in the Atlantic Ocean. Mar. Biol. 2023, 170, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camus, L.; Andrade, H.; Aniceto, A.S.; Aune, M.; Bandara, K.; Basedow, S.L.; Christensen, K.H.; Cook, J.; Daase, M.; Dunlop, K.; et al. Autonomous Surface and Underwater Vehicles as Effective Ecosystem Monitoring and Research Platforms in the Arctic—The Glider Project. Sensors 2021, 21, 6752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riser, S.C.; Freeland, H.J.; Roemmich, D.; Wijffels, S.; Troisi, A.; Belbéoch, M.; Gilbert, D.; Xu, J.; Pouliquen, S.; Thresher, A.; et al. Fifteen years of ocean observations with the global Argo array. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaviano, F.; Esposito, R.; Cosmo, A.D.; Esposito, F.; Gerevini, L.; Ria, A.; Molinara, M.; Bruschi, P.; Costantini, M.; Zupo, V. Management and Sustainable Exploitation of Marine Environments through Smart Monitoring and Automation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.K.; Mickett, J.B.; Doucette, G.J.; Adams, N.G.; Mikulski, C.M.; Birch, J.M.; Roman, B.; Michel-Hart, N.; Newton, J.A. An Autonomous Platform for Near Real-Time Surveillance of Harmful Algae and Their Toxins in Dynamic Coastal Shelf Environments. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, G.; Sun, Y. Energy-Saving Depth Control of an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Using an Event-Triggered Sliding Mode Controller. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Wang, H.-b.; Wang, Y. Dynamic event-triggered formation control for AUVs with fixed-time integral sliding mode disturbance observer. Ocean Eng. 2021, 240, 109893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, A.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, X.; Ge, T. Combined Depth Control Strategy for Low-Speed and Long-Range Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Lin, R.; Liu, C.; Feng, H.; Yu, C.; Yao, B.; Lian, L. Energy optimal depth control for multimodal underwater vehicles with a high accuracy buoyancy actuated system. Ocean Eng. 2023, 286, 115516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Yang, C.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y. Optimization of the Energy Consumption of Depth Tracking Control Based on Model Predictive Control for Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. Sensors 2019, 19, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedev, A.V.; Kostenko, V.V.; Tolstonogov, A.Y. Depth control methods of variable buoyancy AUV. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Underwater Technology (UT), Busan, Republic of Korea, 21–24 February 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, M.; Nandy, S.; Shome, S.N. Energy Efficient Trajectory Tracking Controller for Underwater Applications: ARobust Approach. Aquat. Procedia 2015, 4, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão Carneiro, J.; Bravo Pinto, J.; Gomes de Almeida, F.; Cruz, N.A. Variable Structure Controller for Energy Savings in an Underwater Sensor Platform. Sensors 2024, 24, 5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo Pinto, J.; Falcão Carneiro, J.; Gomes de Almeida, F.; Cruz, N.A. Variable structure depth controller for energy savings in an underwater device: Proof of stability. Actuators 2025, 14, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, W.; Tang, J. Lyapunov-based model predictive control trajectory tracking for an autonomous underwater vehicle with external disturbances. Ocean Eng. 2021, 232, 109010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, J.; Yue, L. Distributed Lyapunov-Based Model Predictive Control for AUV Formation Systems with Multiple Constraints. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Meng, B.; Tian, X. Finite-Time Prescribed Performance Trajectory Tracking Control for Underactuated Autonomous Underwater Vehicles Based on a Tan-Type Barrier Lyapunov Function. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 53664–53675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Brown, L.J. A multiple Lyapunov functions approach for stability of switched systems. In Proceedings of the 2010 American Control Conference, Baltimore, MD, USA, 30 June–2 July 2010; pp. 3253–3256. [Google Scholar]

- Branicky, M.S. Multiple Lyapunov functions and other analysis tools for switched and hybrid systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1998, 43, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipovic, V. Global exponential stability of switched systems. Appl. Math. Mech. 2011, 32, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão Carneiro, J.; Bravo Pinto, J.; Gomes de Almeida, F.; Cruz, N.A. Electrohydraulic and Electromechanical Buoyancy Change Device Unified Vertical Motion Model. Actuators 2023, 12, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão Carneiro, J.; Bravo Pinto, J.; Gomes de Almeida, F.; Cruz, N.A. Model Identification and Control of a Buoyancy Change Device. Actuators 2023, 12, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão Carneiro, J.; Bravo Pinto, J.; Gomes Almeida, F.; Cruz, N. Depth control of an underwater sensor platform: Comparison between variable buoyancy and propeller actuated devices. Sensors 2024, 24, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slotine, J.J.E.; Li, W. Applied Nonlinear Control; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).