Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) among commensal Escherichia coli from poultry is a growing concern for food safety and public health. This study investigated AMR patterns in E. coli isolated from broiler neck skin at slaughter, comparing organic, antibiotic-free (ATB-free), and conventional production systems. A total of 375 samples were collected from two Italian slaughterhouses and tested by broth microdilution following EU protocols. E. coli was recovered from 358 samples, and 37.9% were presumptively positive for ESBL/AmpC-producing strains. Conventional broilers showed the highest resistance to ampicillin (73.8%), sulfonamides (72.5%), and fluoroquinolones (nalidixic acid, 62.5%; ciprofloxacin, 67.5%), while organic and ATB-free systems showed significantly lower levels. Intermediate resistance occurred for trimethoprim (21.4–47.9%) and tetracycline (36–54%), and low prevalence (<10%) was found for gentamicin, tigecycline, and third-generation cephalosporins. No relevant resistance was detected to colistin or carbapenems (≤1.2%). Total E. coli counts did not differ among systems, suggesting differences in resistant strain proportions rather than bacterial load. ATB-free flocks processed after conventional batches displayed higher resistance, indicating possible cross-contamination during slaughter. These results highlight the influence of farming practices and slaughterhouse hygiene on AMR dissemination, underscoring the need for integrated farm-to-slaughter control strategies.

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has emerged as one of the most pressing global health challenges, affecting both human and veterinary medicine [1,2]. Predictive statistical models suggest that in 2019 bacterial antimicrobial resistance was responsible for approximately 5 million deaths globally [3] and, without the implementation of comprehensive and coordinated interventions, this burden is projected to rise markedly by 2050 [4]. Nevertheless, recent evidence demonstrates that containment strategies—such as national surveillance plans, antimicrobial stewardship programs, and strengthened infection-prevention measures—can contribute to measurable reductions in AMR incidence over time [5,6].

In food-producing animals, antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli act as major carriers of transferable resistance determinants, posing a concern that directly intersects with the One Health perspective [7,8]. According to the Global Burden of Disease analyses, six bacterial species accounted for the majority of AMR-related fatalities in 2019, with Escherichia coli emerging as the predominant contributor [3]. Industrial food animal production systems, characterized by high stocking densities and routine antimicrobial administration, create strong selective pressure for resistant strains, facilitating their emergence and dissemination. Within this context, poultry production has been consistently identified as a critical hotspot, underscoring the importance of comparative evaluations between conventional and alternative farming systems to elucidate how distinct production environments shape resistance emergence and dissemination [9,10].

Escherichia coli serves as both a ubiquitous commensal and a sentinel for antimicrobial resistance surveillance [11]. In facts, its broad distribution in animal gut microbiota, remarkable ability to acquire mobile resistance elements, and zoonotic relevance via the food chain make it a suitable model for tracking resistance spread [11,12,13]. Particularly worrisome are ESBL-AmpC-producing strains, which often exhibit co-resistance to other antimicrobial classes such as fluoroquinolones, sulfonamides, and tetracyclines [14,15,16]. To better characterize potential dissemination pathways along the poultry production chain, the present study uses neck skin as the sample matrix, a choice that directly reflects contamination occurring at slaughter and thereby enhances the robustness of the comparison between different farming systems. The spread of dominant E. coli lineages harboring ESBL determinants, particularly blaCTX-M variants, has been reported in both human and veterinary contexts, highlighting how resistance evolves across the entire farm-to-fork chain [9,10]. Recent genomic studies across Europe revealed substantial heterogeneity in ESBL determinants, with clear geographical differences in resistance gene distributions [17].

In recent years, the European Union has strengthened efforts to reduce antimicrobial use in livestock. Legislative measures and consumer-driven demand have contributed to the emergence of alternative production systems, notably organic and antibiotic-free (ATB-free) broiler farming [18]. These systems are characterized by the absence of or a drastic reduction in antimicrobial treatments, lower stocking densities, and enhanced biosecurity measures [19]. Evidence from different studies indicates that broilers raised under alternative or non-conventional production systems tend to show a lower prevalence of resistant E. coli in their caecal contents compared with broilers from intensive systems [20,21,22]. Differences in loads and in the profiles of virulence and resistance genes among E. coli isolates from diverse production contexts further support the hypothesis that management practices and antimicrobial exposure can influence the selection pressure and overall resistance levels. Recent global reviews support this evidence, showing that organic and antibiotic-free farms generally exhibit lower levels of AMR compared with conventional systems, although important variations exist between countries and farming conditions [23].

However, the relationship between farming systems and AMR cannot be entirely explained by antimicrobial use alone. Environmental factors, biosecurity practices, vertical transmission from breeders and the slaughtering process may contribute to shaping the final contamination profile observed on poultry carcasses [11,24,25,26]. Slaughterhouses represent a key node in this chain: previous studies have shown that resistant strains can persist and spread within the slaughterhouse environment, raising concerns that the benefits of antimicrobial reduction at the farm level may be partially offset by cross-contamination during processing [21]. This has been further confirmed by recent Italian studies, which revealed high genomic diversity and persistence of ESBL E. coli in slaughterhouse environments, even in regions with reduced antimicrobial use at the farm level [27].

The choice of sample matrix is also critical for assessing AMR exposure risk. While caecal content has been widely used as a proxy for intestinal carriage, it does not directly reflect what consumers are exposed to. In contrast, neck skin samples are recognized by EFSA as a reliable indicator of carcass hygiene and microbial contamination at slaughter [24,28]. Monitoring resistance in neck skin isolates is therefore highly relevant for food safety, as it provides a direct measure of potential consumer exposure to resistant bacteria [29]. Despite this, most research to date has focused on caecal content or retail meat [30,31], with limited studies addressing neck skin contamination in relation to farming systems. Recent work in Europe and Asia (Malaysia) has shown that ESBL-producing E. coli is also widespread in farm environments and broilers, underscoring the importance of considering both pre-harvest and slaughterhouse contamination routes [32,33].

A further layer of complexity is introduced by the molecular epidemiology of resistant E. coli. Genes encoding ESBLs, such as blaCTX-M (groups 1, 2, 9, 8/25), blaTEM, and blaSHV, as well as plasmid-mediated AmpC genes (blaCMY, blaCIT, blaDHA, blaFOX, etc.), are widely distributed across both human and animal isolates [27,32,34]. Recent systematic reviews confirm that the global prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli in farm animals has risen sharply in the last five years, reflecting the spread of mobile resistance determinants across species and geographical regions [35].

These aspects highlight the importance of assessing AMR not only at farm level but also at slaughter, where consumer exposure is most direct. Yet there remains a lack of data on neck skin contamination of broilers across different production systems. Understanding whether the lower prevalence of resistance observed in caecal contents of organic and ATB-free broilers translates into a tangible reduction in resistant E. coli on carcasses is essential for evaluating the true public health benefits of these systems [36,37,38].

The present study addresses this gap by investigating the prevalence and resistance profiles of E. coli isolated from neck skin of broilers raised in conventional, organic, and ATB-free systems. Furthermore, to explicitly assess the role of slaughterhouse practices in resistance dissemination, the study evaluates the impact of the slaughter sequence on cross-contamination, with particular focus on ATB-free flocks processed before or after conventional batches. By integrating phenotypic resistance data with molecular characterization of ESBL/AmpC genes, this study contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of how farming practices and slaughterhouse dynamics shape AMR at the consumer interface.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The sampling strategy was designed to evaluate potential differences in antimicrobial resistance profiles of E. coli isolates between production systems and slaughterhouses. The specific objectives were:

- ▪

- To verify whether the resistance levels detected in caecal contents were also observed on carcasses (neck skin);

- ▪

- To assess potential differences between the two slaughterhouses for antibiotic-free (ATB-free) flocks;

- ▪

- To investigate whether slaughtering ATB-free flocks after conventional ones could increase the risk of resistance contamination and, based on a priori hypothesis, to determine whether Group C (ATB-free slaughtered after conventional flocks) would show a higher prevalence of resistant E. coli compared with Group D (ATB-free slaughtered before conventional flocks).

Samples originated from a large integrated poultry company which employs three production systems: conventional, organic, and antibiotic-free (ATB-free).

In slaughterhouse 1, organic (group A) and ATB-free (group B) broilers were slaughtered on separate days. In slaughterhouse 2, both conventional (group E) and ATB-free broilers were slaughtered on the same day. For this slaughterhouse, two ATB-free groups were considered depending on slaughter sequence: ATB-free after conventional (group C) and ATB-free before conventional (group D).

The sample size was calculated assuming a 50% expected prevalence of resistant E. coli, 15% precision and 95% confidence level, resulting in a minimum of 285 samples distributed into the five categories listed below. The plan was subsequently adjusted according to field feasibility and slaughterhouse availability, leading to a final sample size greater than initially estimated, thus improving representativeness (Table 1). Neck skin samples were collected at the end of processing from two poultry slaughterhouses, immediately stored at +4 °C, and analyzed within 12 h. Both slaughterhouses operated under comparable hygiene standards and routine line speeds during all sampling days; although minor day-to-day operational variability cannot be entirely excluded, no deviations from standard processing conditions were reported, thereby minimizing the influence of unmeasured confounders on the sequence-based comparison.

Table 1.

Number of neck skin samples collected from broilers raised in conventional, antibiotic-free, and organic production systems across the different categories and slaughterhouses.

2.2. Sampling

Between February and May 2019, 375 neck skin samples were collected from broiler chickens slaughtered at two Italian poultry slaughterhouses (slaughterhouse 1 and slaughterhouse 2). For each category, the sampling plan was defined using an assumed prevalence of 50%, a 95% confidence level, and a precision of 15%. The plan was subsequently adjusted according to field feasibility and slaughterhouse availability, leading to a final sample size greater than initially estimated, thus improving representativeness (Table 1).

2.3. Microbiological Analyses

2.3.1. Bacterial Enumeration

Quantitative culture was used to determine the neck skin loads of E. coli and E. coli resistant to 3rd generation cephalosporin and to nalidixic acid. Briefly, approximately 25 g of neck skin were homogenized in buffered peptone water into a Stomacher bag. The suspension (10−1 dilution w/v) was further 10-fold diluted in 0.9% saline. The colony-forming units (CFU) of E. coli of interests were determined by plating 100 μL of each dilution on MacConkey agar for total E. coli count, MacConkey agar supplemented with cefotaxime (1 µg/mL) (Sigma Aldrich—Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) for the isolation of 3rd generation cephalosporin-resistant E. coli, MacConkey agar supplemented with nalidixic acid (50 µg/mL) (Sigma Aldrich—Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) for the isolation of quinolone-resistant E. coli.

Colony counts were expressed as log10 CFU/g of skin. For negative results, 10 µL of buffered peptone water incubated at 37 °C for 24 h was plated and only presence/absence recorded. One colony per plate was sub-cultured on TSA and confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany).

2.3.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

One typical colony per sample was selected at random and E. coli isolates from MacConkey agar (n = 358) were tested for antimicrobial susceptibility by broth microdilution using Sensititre EU Surveillance Salmonella/E. coli EUVSEC plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), in accordance with Commission Decision 2013/652/EU [39]. The EUVSEC panel (currently commercialized as EUVSEC3) included the following antimicrobials and concentration ranges (mg/L): ampicillin (AMP, 1–64), azithromycin (AZI, 2–64), cefotaxime (FOT, 0.25–4), ceftazidime (TAZ, 0.5–8), chloramphenicol (CHL, 8–128), ciprofloxacin (CIP, 0.015–8), colistin (COL, 1–16), gentamicin (GEN, 0.5–32), meropenem (MEM, 0.03–16), nalidixic acid (NAL, 4–128), sulfamethoxazole (SMX, 8–1024), tetracycline (TET, 2–64), tigecycline (TGC, 0.25–8), and trimethoprim (TMP, 0.25–32).

A total of 142 E. coli isolates recovered on MacConkey agar supplemented with cefotaxime was further tested for ESBL/AmpC phenotypes using Sensititre EU Surveillance ESBL/AmpC EUVSEC2 plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The EUVSEC2 panel included: cefepime (FEP, 0.06–32), cefotaxime (FOT, 0.25–64), cefotaxime/clavulanic acid (F/Cl, 0.06/4–64/4), cefoxitin (FOX, 0.5–64), ceftazidime (TAZ, 0.25–128), ceftazidime/clavulanic acid (T/Cl, 0.12/4–128/4), ertapenem (ETP, 0.015–2), imipenem (IMI, 0.12–16), meropenem (MEM, 0.03–16), and temocillin (TRM, 0.5–128). For wells containing clavulanate, the inhibitor was present at a fixed concentration (4 mg/L). E. coli strain ATCC 25922 served as the quality-control strains.

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) determination was performed on all E. coli isolates recovered from both unsupplemented (EUVSEC panel, n = 358) and cefotaxime-supplemented (EUVSEC 2 panel, n = 142) MacConkey agar using the broth microdilution method. While MIC results from EUVSEC isolates were used to estimate antimicrobial resistance prevalence, EUVSEC 2 tested isolates served for the qualitative assessment of presumptive ESBL/AmpC resistance, later confirmed by PCR.

MIC values were interpreted according to the epidemiological cutoff values (ECOFFs) defined by EFSA in 2024 [40], and percentages of non-wild-type (NWT) isolates are reported as resistance rates.

2.4. Molecular Characterization

The 142 isolates collected from MacConkey agar supplemented with cefotaxime (1 µg/mL) and tested for antimicrobials with EUVSEC2 panels were subjected also to molecular analysis for the detection of ESBL/AmpC genes. Based on the phenotypic interpretation, isolates were preliminarily categorized as presumptive AmpC or ESBL-producing. Subsequent molecular analysis was therefore targeted to the corresponding resistance genes.

Genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hombrechtikon, Switzerland), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The detection of ESBL and AmpC-associated genes was carried out following the protocol described by Tofani et al. [21] with additional methodological details as follows.

Briefly, isolates recovered on MacConkey agar supplemented with cefotaxime were screened by PCR for the following targets:

- ESBL genes: blaTEM, blaSHV, blaOXA (multiplex PCR); blaCTX-M groups 1, 2, and 9 (multiplex PCR) [41];

- Isolates positive for blaCTX-M group 1 were further analyzed by a specific simplex PCR for the allelic variant blaCTX-M-15 [42];

- AmpC genes: blaACC, blaFOX, blaMOX, blaDHA, blaCIT, and blaEBC (multiplex PCR) [43];

- Isolates positive for blaCIT were tested by a simplex PCR for the detection of blaCMY-2 [44].

The PCR protocol was largely consistent across target genes, with minor target-specific modifications reported in the cited references [21,41,42,43,44]. Each 25 µL reaction contained approximately 50 ng of template DNA, 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase, 2.5 µL of 10× buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, and primers at 0.4–0.5 µM. Thermal cycling included an initial denaturation at 94–95 °C for 5 min, followed by 30–35 cycles of denaturation at 94–95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 58–60 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72 °C for 5–7 min. PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis (1.5% agarose, TBE buffer, Promega, Milan, Italy). Reference strains carrying known ESBL and AmpC genes were included as positive controls.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The bacterial counts were converted to log10 CFU/g of neck skin for statistical analysis and tested for normality (Shapiro–Wilk test). Since distributions were non-normal, Kruskal–Wallis tests were applied to compare groups, followed by pairwise Wilcoxon rank-sum tests with Bonferroni correction.

Prevalence data were summarized as percentages with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Differences in prevalence between production systems were assessed using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Pearson’s Chi-square test was used when all expected cell counts were ≥5, whereas Fisher’s exact test was applied in cases where one or more expected frequencies fell below this threshold, in accordance with standard statistical recommendations. In addition, odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs were calculated for each group with the conventional production type as a reference (OR = 1). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed in R version 4.5.0 (R Core Team, 2025) within RStudio version 2025.05.1+513 (Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA, USA).

3. Results

Out of the 375 samples, E. coli was successfully isolated from 358 (95.5%), which were included in the subsequent analyses, while 17 samples were negative for E. coli growth.

3.1. Enumeration of E. coli: Quantitative Analysis

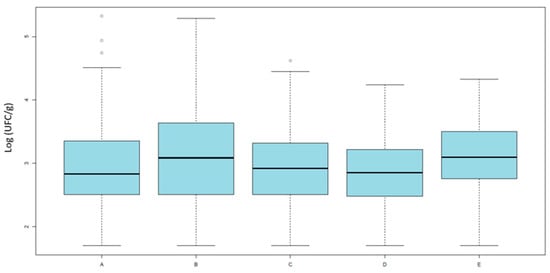

The data did not follow a normal distribution (Shapiro–Wilk test, p < 0.0001), the distribution of total E. coli counts on MacConkey agar (Figure 1) did not significantly differ between groups (Kruskal–Wallis χ2 = 8.58, df = 4, p = 0.0724), indicating that the overall level of E. coli contamination was comparable across groups.

Figure 1.

Results of quantitative analysis. Averages of E. coli loads (Log10 UFC/g) isolated on MacConkey agar across the five categories. Category A includes organic broilers processed in slaughterhouse 1; Category B includes antibiotic-free broilers also from slaughterhouse 1; Categories C and D include antibiotic-free broilers processed in slaughterhouse 2, respectively, after or before conventional batches; and Category E includes conventional broilers processed in slaughterhouse 2.

This suggests that the observed differences in antimicrobial resistance are not attributable to variations in bacterial load, but rather to the relative proportion of resistant strains within the E. coli population.

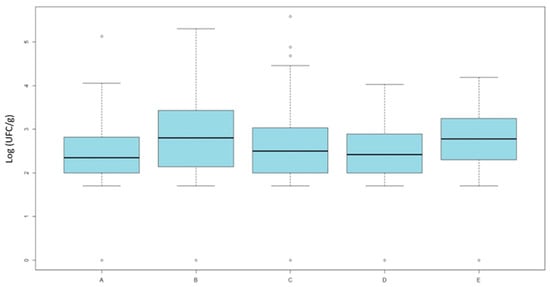

Counts on MacConkey agar supplemented with nalidixic acid showed significant differences (Kruskal–Wallis, χ2 = 17.98, df = 4, p = 0.0012) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Results of quantitative analysis. Averages of E. coli loads (Log UFC/g) isolated on MacConkey agar supplemented with nalidixic-acid across the five categories. Category A includes organic broilers processed in slaughterhouse 1; Category B includes antibiotic-free broilers also from slaughterhouse 1; Categories C and D include antibiotic-free broilers processed in slaughterhouse 2, respectively, after or before conventional batches; and Category E includes conventional broilers processed in slaughterhouse 2.

Pairwise comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Bonferroni adjustment. Post hoc Wilcoxon tests revealed that organic broilers (group A) had significantly lower counts of quinolone-resistant E. coli compared with ATB-free broilers (group B, p = 0.049) and conventional broilers (group E, p = 0.006). Additionally, ATB-free broilers slaughtered before conventional (group D) differed from the conventional group (p = 0.048), while no difference was observed for those slaughtered after (group C).

However, the difference between groups C and D was minimal, as confirmed by the graphical distribution and the non-significant p-value reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Pairwise comparison between different broiler production systems (Wilcoxon rank sum test with Bonferroni correction). Reported values are p-values; dashes indicate redundant comparisons (already shown in the symmetric cell).

On MacConkey agar supplemented with cefotaxime, counts were low and frequently below the detection limit.

The Kruskal–Wallis test indicated significant differences among groups (χ2 = 12.57, df = 4, p = 0.0136). Moreover, most observations fell below the detection threshold or were only positive after pre-enrichment, making quantitative analysis less informative. For this reason, results were transformed into a qualitative outcome (positive/negative growth). A sample was considered ESBL-positive if any growth was detected on MacConkey agar supplemented with cefotaxime. The count of ESBL-positive E. coli also included presumptive AmpC producers.

The distribution of ESBL positive samples was as follows: 33.3% in group A (25/75), 26.2% in group B (17/65), 42.9% in group C (45/105), 30% in group D (15/50), and 50.0% in group E (40/80), corresponding to an overall prevalence of 37.9% (142/375) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence of presumptive ESBL/AmpC positive E. coli in neck skin samples isolated from MacConkey supplemented with cefotaxime, divided by category, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs 95%).

Results of the odds ratio for ESBL/AmpC positivity E. coli, using the conventional production type as a reference (group E), are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the prevalence of ESBL/AmpC-positive E. coli in broiler neck skin samples by production system. The conventional group (E) was used as the reference category (OR = 1).

Given the relevance of slaughter sequence in shaping potential cross-contamination dynamics, the following results specifically address the comparison between ATB-free flocks processed before or after conventional batches. This aspect is particularly noteworthy, as the observed patterns partially diverge from expected contamination trends.

These results describe a protective effect of ATB-free and organic farming against ESBL-AmpC E. coli contamination. This effect was significant for group B (ATB-free broilers from slaughterhouse 1) and group D (ATB-free slaughtered before conventional batches at slaughterhouse 2). Protective but borderline effect is significant (OR = 0.50, 95% CI = 0.24–1.00, p = 0.049) in group A (organic production system). No significant protection was observed when ATB-free broilers were slaughtered after conventional flocks (group C). Nonetheless, the contrast between groups C and D highlights the potential impact of slaughter sequence on contamination risk, although the difference between groups C and D was modest, as reflected by the prevalence values and the overlapping 95% confidence intervals.

3.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profiles

Both E. coli isolates obtained from MacConkey agar (n = 358) and those recovered from MacConkey agar supplemented with cefotaxime (n = 142) were tested by MIC. The two groups were analyzed for different purposes. Total E. coli isolates from MacConkey, representative of commensal E. coli, were used to assess antimicrobial resistance prevalence across farming systems. Conversely, E. coli isolates from MacConkey supplemented with cefotaxime, presumptively selected for resistance to third-generation cephalosporins, were evaluated qualitatively to estimate the occurrence of ESBL and/or AmpC-producing E. coli. MIC data obtained using EUVSEC 2 panel were not included in prevalence calculations but used to support the presumptive classification subsequently confirmed by molecular testing.

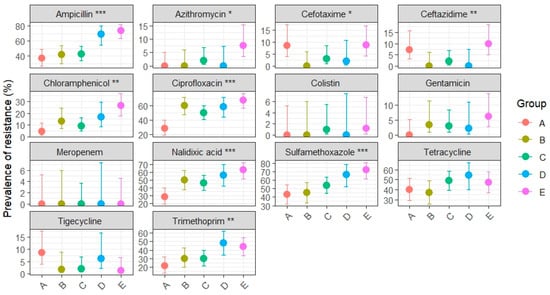

Phenotypic resistance patterns of E. coli isolates from MacConkey agar and tested with EUVSEC panel are summarized in Appendix A, Table A1, while the distribution of MIC values for each antimicrobial agent is presented in Supplementary Table S1. Figure 3 illustrates prevalence estimates with 95% CIs across production systems with statistical significance for overall group differences (Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test).

Figure 3.

Dot-and-whisker plot of resistance prevalence (%) with 95% CIs for total E. coli from MacConkey agar isolated from broiler neck skin, stratified by category (A: organic, B: antibiotic-free, C: ATB-free after conventional, D: ATB-free before conventional, E: conventional). Asterisks indicate the level of statistical significance for overall group differences (Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test): p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***).

Ampicillin resistance was not evenly distributed across production systems (p < 0.001), with the highest prevalence observed in conventional broilers (73.8%, 95% CI: 63.2–82.1), significantly exceeding that in organic (37.1%, 95% CI: 26.8–48.9), ATB-free (43.3%, 95% CI: 30.1–54.3), and ATB-free broilers slaughtered after conventional groups (42.6%, 95% CI: 33.7–52.8). ATB-free broilers slaughtered before conventional batches (group D) showed very high resistance (68.8%, 95% CI: 54.7–80.1), closer to conventional broilers, likely reflecting cross-contamination during slaughter processing.

Ciprofloxacin resistance also differed significantly (p < 0.001) among groups, with conventional broilers showing the highest prevalence (67.5%, 95% CI: 56.0–77.2), significantly greater than organic (28.6%, 95% CI: 19.3–40.1) and ATB-free broilers slaughtered after conventional groups (50.0%, 95% CI: 37.4–62.6). Both ATB-free groups from slaughterhouse 1 and slaughterhouse 2 (before conventional) showed unexpectedly very high prevalence, of 60% (95% CI: 47.4–71.4) and 58.3% (95% CI: 44.3–71.2), respectively.

Similar patterns were observed for nalidixic acid (p < 0.001) and chloramphenicol (p < 0.01). Nalidixic acid resistance was markedly higher in conventional broilers (62.5%, 95% CI: 51.5–72.3) than organic (28.6%, 95% CI: 19.3–40.1); whereas chloramphenicol showed an increasing gradient from organic (4.3%, 95% CI: 1.5–11.9) to conventional (26.2%, 95% CI: 17.9–36.8). Ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid and chloramphenicol intermediate ATB-free groups displayed overlapping CIs.

Resistance to sulfamethoxazole showed consistently high prevalence across all production systems (p < 0.001). The highest rate was in conventional broilers (72.5%, 95% CI: 61.9–81.1), followed by D group (66.7%, 95% CI: 52.5–78.3) but with substantial levels also in ATB-free groups A-B (from 45% to 54%, overlapped CIs) and organic group (42.9%, 95% CI: 31.9–54.5).

Trimethoprim demonstrated differences among production systems (p < 0.01), with groups D and E clustering at higher prevalence values compared to other groups (D: 47.9%, 95% CI: 34.5–61.7; E: 43.8%, 95% CI: 33.4–54.7).

Differences were also observed for ceftazidime (p < 0.01), azithromycin and cefotaxime (p < 0.05). Although all rates fell within the EFSA “low resistance” range (1–10%) [45], ceftazidime and cefotaxime resistance were relatively higher in the conventional group (CEZ: 10%, CEF: 8.8%) compared to the organic group (CEZ: 7.1%, CEF: 8.6%). Conversely, tetracycline resistance was uniformly high across all groups (36–54%), with overlapping confidence intervals indicating no significant differences.

For gentamicin, tigecycline, cefotaxime and ceftazidime prevalence were low (0–10%) and confidence intervals were wide and largely overlapping, suggesting limited epidemiological relevance. No resistance was observed to meropenem or colistin.

These findings demonstrate that antimicrobial resistance is not homogeneously distributed across production systems, with conventional broilers consistently showing the highest prevalence. Organic and ATB-free systems generally displayed reduced resistance, except where cross-contamination during slaughter likely influenced outcomes.

3.3. Molecular Characterization

Prior to molecular analysis, all isolates obtained from MacConkey agar supplemented with cefotaxime were tested for MIC values and, based on the phenotypic interpretation, they were preliminarily categorized as presumptive AmpC or ESBL-producing strains. Subsequent PCR screening was therefore targeted to the corresponding resistance genes.

A total of 142 isolates were analyzed. Based on phenotypic interpretation, 129/142 (90.8%) isolates were initially categorized as presumptive ESBL producers and 12/142 (8.5%) as presumptive AmpC producers. Among the presumptive ESBL producers, 128/129 (99.2%) were confirmed to carry ESBL genes, while among the presumptive AmpC producers, 11/12 (91.7%) were confirmed to carry AmpC genes.

Overall, molecular testing revealed that 128/142 (90.2%) were positive for ESBL genes and 11/142 (7.7%) were positive for AmpC genes. Only 3/142 (2.1%) isolates that were initially classified as presumptive positive were negative for all tested genes. Distributions of detected genes are described in Table 5.

Table 5.

Distribution of detected ESBL and AmpC genes among 142 tested isolates.

Statistical analyses of ESBL and AmpC gene prevalence across production systems were performed using Fisher’s Exact Test. No significant differences were observed for either ESBL (p = 0.869) or AmpC (p = 0.617) gene distribution among the groups, indicating that the occurrence of these resistance genes was similar across the different production systems.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrated that poultry production systems strongly influence the prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant Escherichia coli on broiler neck skin and consequently the carcasses.

The quantitative results indicate that the overall commensal E. coli load on neck skin samples did not significantly differ among production systems, suggesting that the total level of bacterial contamination was comparable across groups. This observation implies that differences in antimicrobial resistance are not attributable to variations in bacterial load, but rather to the relative abundance of resistant strains within the E. coli population. Similar findings have been reported in previous studies showing that total commensal E. coli counts on poultry carcasses are generally independent of farming type [29,46]. However, when focusing on quinolone- and cephalosporin-resistant E. coli, significant differences emerged between production categories. Organic and antibiotic-free (ATB-free) broilers showed lower counts of resistant E. coli compared with conventional ones, particularly when ATB-free flocks were processed before conventional batches. Conversely, ATB-free broilers slaughtered after conventional flocks exhibited resistance levels comparable to conventional systems, indicating a potential carry-over effect due to cross-contamination during processing. This pattern aligns with previous studies demonstrating that slaughter sequence and equipment hygiene play a crucial role in the dissemination of resistant bacteria, with surfaces and tools acting as reservoirs facilitating transfer between flocks [47,48]. Additionally, these findings extend previous observations on caecal contents [20,30,31] to the slaughterhouse stage, where neck skin represents a relevant indicator for carcass contamination [24]. Our results generally align with previous studies conducted on caecal contents [20,21,22], which, although not directly comparing caecal and carcass isolates from the same animals, supporting the view that the intestinal microbiota represents the primary source of contamination during slaughter. Resistance prevalence on carcasses tends to be slightly lower—mainly due to processing steps such as scalding, defeathering, and washing—while overall resistance profiles remain comparable.

Conventional broilers harbored the highest prevalence of resistant E. coli, particularly to ampicillin (73.8%) and sulfamethoxazole (72.5%), with confidence intervals clearly separating this group from organic (ampicillin 37.1%, sulfamethoxazole 42.9%) and ATB-free broilers (41.7–54%). Resistance to fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid) followed a similar pattern, with significantly higher levels (62.5–67.5%) in conventional compared to organic broilers (28.6% for both). Ampicillin, sulfonamides, and fluoroquinolones remain key markers of resistance in poultry E. coli [14,15,16,47]. These trends are consistent with the pan-European survey conducted in 2022 [49], which reported variable but generally high resistance levels in commensal E. coli from broilers, particularly to ampicillin and sulfonamides. However, the levels observed in our study were often higher, possibly reflecting local differences in antimicrobial use. Differences in production system likely reflect the overuse of antimicrobial and higher stocking densities in conventional systems [30,50], while organic and ATB-free standards reduce selective pressure for resistant strains [51]. Importantly, no resistance was observed to carbapenems (meropenem) or colistin, drugs of last resort in human medicine, confirming generally EU-wide surveillance trends in 2025 [7]. Although resistance to these last-resort antibiotics was generally absent across the EU, isolated reports documented E. coli isolates from healthy broilers carrying the plasmid-borne mcr-1 and blaNDM genes [52], underscoring the One Health risk posed by antimicrobial resistance in poultry. Resistance to cefotaxime and ceftazidime in E. coli, proxies for ESBL production, was detected at low but significant levels, with the highest prevalence in conventional raised broilers. The notably lower resistance rates found in organic and ATB-free production systems further reinforce the hypothesis that restricting antimicrobial use in livestock can effectively reduce the selection and dissemination of resistant bacterial strains.

Although phenotypic resistance varied among production systems, molecular analysis showed no significant differences in the distribution of ESBL/AmpC genetic determinants. This apparent discrepancy is well described in the literature: the presence of a resistance gene does not necessarily result in its phenotypic expression, as transcriptional regulation, promoter variation, gene copy number or mutations can modulate expression levels [53,54,55]. Moreover, additional mechanisms—such as efflux pump overexpression or porin alterations—may contribute to resistance independently of β-lactamase genes [53,56]. Finally, molecular assays detect the presence of genes within the population, whereas phenotypic tests reflect the fraction of cells actively expressing resistance at the time of testing. The expression of resistance genes is also strongly influenced by environmental conditions—including antimicrobial exposure, microbial interactions, disinfectants and other environmental stressors—which may differ across production systems even when the same genetic determinants are widely disseminated [21,53].

This interpretation is consistent with reports from other European studies [32,34], which also observed widespread dissemination of blaCTX-M and blaCMY genes regardless of production type. Our findings do not always fully align with a previous study [21], which observed a reduced prevalence of resistance in organic and ATB-free poultry systems. However, this divergence may be partly attributable to methodological differences and to the type of matrix analyzed (caecal content versus neck skin in our study), primarily reflecting the intestinal microbiota and internal colonization patterns.

The slaughter sequence played a critical role in shaping resistance prevalence: this observation aligns with previous reports highlighting the impact of slaughterhouse hygiene practices and sequencing on cross-contamination [57,58]. The results observed for Groups C and D were partially counter-intuitive, as ATB-free broilers processed before conventional batches unexpectedly showed resistance levels close to conventional broilers, whereas ATB-free flocks slaughtered after conventional displayed lower rates. This apparently contradicts the biological expectation that flocks processed after conventional broilers would be more contaminated and diverges from the expected pattern and from previous evidence [20,21], suggesting that slaughterhouse environment or residual contamination may play a larger role. This complexity should be interpreted with caution, as the sample size available for the sequence sub-study may have limited the statistical power to detect clearer differences. Moreover, unmeasured confounding factors—such as day-specific variations in water quality, ambient temperature, or operational conditions unique to Slaughterhouse 2—may also have influenced cross-contamination dynamics. To address this issue in more detail, several hypotheses can be considered.

First, groups C–E were processed in slaughterhouse 2, where conventional broilers were routinely slaughtered, possibly leading to a baseline environmental contamination that already affected group D. In contrast, slaughterhouse 1 (processing only organic and ATB-free) consistently showed lower resistance levels. Second, hygiene procedures such as partial cleaning and disinfection between production batches could have reduced residual contamination, mitigating the expected increase in group C. Finally, group D included only 50 samples compared with 105 in group C, reducing statistical power and resulting in wider confidence intervals, which weakens the robustness of the comparisons.

In addition, our finding of unexpectedly high ciprofloxacin resistance in E. coli isolates from ATB-free broiler, particularly those slaughtered before conventional batches, is consistent with previous reports documenting substantial fluoroquinolone resistance even in antibiotic-free production systems [16].

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that both production systems and slaughter practices significantly influence the prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant E. coli on broiler neck skin, with potential implications for bacterial contamination of carcasses. Broilers raised under organic and antibiotic-free conditions generally exhibited lower resistance levels compared to those from conventional systems, supporting the protective effect of reduced antimicrobial use. Molecular analysis further showed that 128 of 142 isolates (90.2%) carried ESBL genes and 11 of 142 (7.7%) harbored AmpC genes, whereas only 3 of 142 isolates (2.1%) initially classified as presumptive positives tested negative for all targeted genetic determinants.

The role of production systems and slaughterhouse practices in shaping antimicrobial resistance highlights the need for further investigation. Future studies could integrate genomic approaches to better characterize circulating E. coli strains across different production systems, providing deeper insights into AMR dynamics along the food chain and supporting the development of effective mitigation strategies.

These results highlight that not only farm management but also the slaughterhouse environment and hygiene strongly influence AMR spread. Improving slaughter hygiene practices and expanding non-conventional production systems may reduce the dissemination of resistant bacteria along the food chain, thereby contributing to a lower public health risk associated with resistant E. coli and reinforcing the One Health perspective.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pathogens14121265/s1. Table S1. Distribution of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of E. coli isolates from MacConkey agar (n = 358) obtained using the EUVSEC panel. Percentages are shown in brackets. The gray-shaded areas indicate the range of concentrations tested for each antimicrobial. Black vertical bars indicate the epidemiological cut-off values (ECOFFs), according to the EFSA report (2024) [40].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization G.P. and C.F.M.; methodology G.D., F.B., S.T., E.A., S.O., M.C., F.R.M. and M.P.; software G.D.; validation G.P. and C.F.M.; formal analysis G.D., F.B., S.T., E.A., S.O., M.C., F.R.M. and M.P.; investigation G.D., F.B., S.T., E.A., S.O., M.C., F.R.M. and M.P.; resources G.P. and C.F.M.; data curation G.D., F.B. and F.R.M.; writing—original draft preparation G.D., F.B., F.R.M. and C.F.M.; writing—review and editing G.D., F.B., S.T., E.A., S.O., M.C., F.R.M., M.P., G.P. and C.F.M.; supervision G.P. and C.F.M.; project administration G.P. and C.F.M.; funding acquisition G.P. and C.F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Programma di Sviluppo Rurale 2014/2020 Regione Marche, “Il biopackaging in una filiera agricola industriale a basso impatto ambientale nel rispetto dell`economia circolare” (ABRIOPACK), grant number PSRM32019.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMR | Antimicrobial Resistance |

| ATB-free | Antibiotic-free |

| CFU | Colony Forming Units |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| COL | Colistin |

| df | Degrees of Freedom |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| E. coli | Escherichia coli |

| ECDC | European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control |

| ECOFF | Epidemiological Cut-Off Value |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| ETP | Ertapenem |

| EU | European Union |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| EUVSEC/EUVSEC2/EUVSEC3 | Sensititre EU Surveillance E. coli/Salmonella panels |

| ESBL | Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase |

| FEP | Cefepime |

| FOT | Cefotaxime |

| F/Cl | Cefotaxime/Clavulanic acid |

| FOX | Cefoxitin |

| GEN | Gentamicin |

| IMI | Imipenem |

| MEM | Meropenem |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MALDI-TOF MS | Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization–Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry |

| NAL | Nalidixic Acid |

| NWT | Non-Wild Type |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| R | R statistical software |

| SE | Standard Error |

| SMX | Sulfamethoxazole |

| TBE | Tris–Borate–EDTA buffer |

| TET | Tetracycline |

| TGC | Tigecycline |

| TMP | Trimethoprim |

| TRM | Temocillin |

| TAZ | Ceftazidime |

| T/Cl | Ceftazidime/Clavulanic acid |

| TSA | Tryptic Soy Agar |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WT | Wild Type |

| χ2 | Chi-squared statistic test |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Selected resistance profiles of E. coli isolates collected on MacConkey agar from neck skin with CIs 95% in different production systems (A = Organic, B = ATB-free, C = ATB-free after conventional, D = ATB-free before conventional, E = Conventional). Groups A and B refer to slaughterhouse 1; groups C, D and E refers to slaughterhouse 2.

Table A1.

Selected resistance profiles of E. coli isolates collected on MacConkey agar from neck skin with CIs 95% in different production systems (A = Organic, B = ATB-free, C = ATB-free after conventional, D = ATB-free before conventional, E = Conventional). Groups A and B refer to slaughterhouse 1; groups C, D and E refers to slaughterhouse 2.

| Antibiotic | A | B | C | D | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | 37.1% | 41.7% | 43.0% | 68.8% | 73.8% |

| (26.8–48.9) | (30.1–54.3) | (33.7–52.8) | (54.7–80.1) | (63.2–82.1) | |

| Azithromycin | 0% | 0% | 2% | 0% | 7.5% |

| (0.0–5.2) | (0.0–6.0) | (0.6–7.0) | (0.0–7.4) | (3.5–15.4) | |

| Cefotaxime | 8.6% | 0% | 3% | 2.1% | 8.8% |

| (4.0–17.5) | (0.0–6.0) | (1.0–8.5) | (0.4–10.9) | (4.3–17.0) | |

| Ceftazidime | 7.1% | 0% | 2% | 0% | 10% |

| (3.1–15.7) | (0.0–6.0) | (0.6–7.0) | (0.0–7.4) | (5.2–18.5) | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 28.6% | 60% | 50% | 58.3% | 67.5% |

| (19.3–40.1) | (47.4–71.4) | (40.4–59.6) | (44.3–71.2) | (56.6–76.8) | |

| Chloramphenicol | 4.3% | 13.3% | 9% | 16.7% | 26.2% |

| (1.5–11.9) | (6.9–24.2) | (4.8–16.2) | (8.7–29.6) | (17.9–36.8) | |

| Meropenem | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| (0.0–5.2) | (0.0–6.0) | (0.0–3.7) | (0.0–7.4) | (0.0–4.6) | |

| Nalidixic acid | 28.6% | 50% | 46% | 56.2% | 62.5% |

| (19.3–40.1) | (37.7–62.3) | (36.6–55.7) | (42.3–69.3) | (51.5–72.3) | |

| Trimethoprim | 21.4% | 30% | 30% | 47.9% | 43.8% |

| (13.4–32.4) | (19.9–42.5) | (21.9–39.6) | (34.5–61.7) | (33.4–54.7) | |

| Tigecycline | 8.6% | 1.7% | 2% | 6.2% | 1.2% |

| (4.0–17.5) | (0.3–8.9) | (0.6–7.0) | (2.1–16.8) | (0.2–6.7) | |

| Tetracycline | 40% | 36.7% | 49% | 54.2% | 47.5% |

| (29.3–51.7) | (25.6–49.3) | (39.4–58.7) | (40.3–67.4) | (36.9–58.3) | |

| Colistin | 0% | 0% | 1% | 0% | 1.2% |

| (0.0–5.2) | (0.0–6.0) | (0.2–5.4) | (0.0–7.4) | (0.2–6.7) | |

| Gentamicin | 0% | 3.3% | 3% | 2.1% | 6.2% |

| (0.0–5.2) | (0.9–11.4) | (1.0–8.5) | (0.4–10.9) | (2.7–13.8) | |

| Sulfamethoxazole | 42.9% | 45% | 54% | 66.7% | 72.5% |

| (31.9–54.5) | (33.1–57.5) | (44.3–63.4) | (52.5–78.3) | (61.9–81.1) |

References

- WHO. EMRO—Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/drug-resistance/global-action-plan.html (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Measures to Tackle Antimicrobial Resistance Through the Prudent Use of Antimicrobials in Animals; Overview Report; DG Health and Food Safety Health and Food Safety: Brussel, Belgium, 2019. [CrossRef]

- L Murray, C.J.; Shunji Ikuta, K.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, R. O’Neill report on antimicrobial resistance: Funding for antimicrobial specialists should be improved. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2016, 23, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.S.; Wong, C.T.H.; Aung, T.T.; Lakshminarayanan, R.; Mehta, J.S.; Rauz, S.; McNally, A.; Kintses, B.; Peacock, S.J.; de la Fuente-Nunez, C.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance: A concise update. Lancet Microbe 2025, 6, 100947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECDC. Antimicrobial Resistance in the EU/EEA (EARS-Net) EU Targets on Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/antimicrobial-resistance-eueea-ears-net-annual-epidemiological-report-2024 (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- European Food Safety Authority; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. The European Union summary report on antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2022–2023. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M.A.; Rempel, H.; Carrillo, C.D.; Ziebell, K.; Ziebell, K.; Manges, A.R.; Topp, E.; Diarra, M.S. Virulence Genotype and Phenotype of Multiple Antimicrobial-Resistant Escherichia coli Isolates from Broilers Assessed from a “One-Health” Perspective. J. Food Prot. 2022, 85, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landoni, M.F.; Albarellos, G. The use of antimicrobial agents in broiler chickens. Vet. J. 2015, 205, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nhung, N.T.; Cuong, N.V.; Thwaites, G.; Carrique-Mas, J. Antimicrobial Usage and Antimicrobial Resistance in Animal Production in Southeast Asia: A Review. Antibiotics 2016, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirel, L.; Madec, J.-Y.; Lupo, A.; Schink, A.K.; Kieffer, N.; Nordmann, P.; Schwarz, S. Antimicrobial Resistance in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, N.; Turton, J.F.; Livermore, D.M. Multiresistant Gram-negative bacteria: The role of high-risk clones in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 35, 736–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falgenhauer, L.; Ghosh, H.; Doijad, S.; Yao, Y.; Bunk, B.; Spröer, C.; Kaase, M.; Hilker, R.; Overmann, J.; Imirzalioglu, C.; et al. Genome Analysis of the Carbapenem- and Colistin-Resistant Escherichia coli Isolate NRZ14408 Reveals Horizontal Gene Transfer Pathways towards Panresistance and Enhanced Virulence. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewers, C.; Bethe, A.; Semmler, T.; Guenther, S.; Wieler, L.H. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing and AmpC-producing Escherichia coli from livestock and companion animals, and their putative impact on public health: A global perspective. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madec, J.Y.; Haenni, M.; Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase/AmpC- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in animals: A threat for humans? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017, 23, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, N.; Anjali; Shreyata; Sabu, B.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Rajagopal, R. Assessment of antibiotic resistance in chicken meat labelled as antibiotic-free: A focus on Escherichia coli and horizontally transmissible antibiotic resistance genes. LWT 2024, 194, 115751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspersen, H.P.; Brouwer, M.S.M.; Nunez-Garcia, J.; Cárdenas-Rey, I.; AbuOun, M.; Duggett, N.; Ellaby, N.; Delgado-Blas, J.; Hammerl, J.A.; Getino, M.; et al. Escherichia coli from six European countries reveals differences in profile and distribution of critical antimicrobial resistance determinants within One Health compartments, 2013 to 2020. Eurosurveillance 2024, 29, 2400295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Environment Agency. Veterinary Antimicrobials in Europe’s Environment: A One Health Perspective. 2024. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/veterinary-antimicrobials-in-europes-environment-a-one-health-perspective (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Van Boeckel, T.P.; Glennon, E.E.; Chen, D.; Gilbert, M.; Robinson, T.P.; Grenfell, B.T.; Levin, S.A.; Bonhoeffer, S.; Laxminarayan, R. Reducing antimicrobial use in food animals. Science 2017, 357, 1350–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesciaroli, M.; Magistrali, C.F.; Filippini, G.; Epifanio, E.M.; Lovito, C.; Marchi, L.; Maresca, C.; Massacci, F.R.; Orsini, S.; Scoccia, E.; et al. Antibiotic-resistant commensal Escherichia coli are less frequently isolated from poultry raised using non-conventional management systems than from conventional broiler. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 314, 108391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofani, S.; Albini, E.; Blasi, F.; Cucco, L.; Lovito, C.; Maresca, C.; Pesciaroli, M.; Orsini, S.; Scoccia, E.; Pezzotti, G.; et al. Assessing the Load, Virulence and Antibiotic-Resistant Traits of ESBL/Ampc E. coli from Broilers Raised on Conventional, Antibiotic-Free, and Organic Farms. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, G.; Buonavoglia, A.; Farooq, M.; Festino, A.R.; Ruffini, F.; Paludi, D.; Francesco, C.E.D.; Vergara, A.; Smoglica, C. Antibiotic resistance in Italian poultry meat production chain: A one-health perspective comparing antibiotic free and conventional systems from the farming to the slaughterhouse. Front. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 3, 1168896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ager, E.O.; Carvalho, T.; Silva, E.M.; Ricke, S.C.; Hite, J.L. Global trends in antimicrobial resistance on organic and conventional farms. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panels on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ); on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM); on Animal Health and Welfare (AHAW). Scientific Opinion on the public health hazards to be covered by inspection of meat (poultry). EFSA J. 2012, 10, 2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhung, N.T.; Yen, N.T.P.; Dung, N.T.T.; Nhan, N.T.M.; Phu, D.H.; Kiet, B.T.; Thwaites, G.; Geskus, R.B.; Baker, S.; Carrique-Mas, J.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance in commensal Escherichia coli from humans and chickens in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam is driven by antimicrobial usage and potential cross-species transmission. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 4, dlac054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA BIOHAZ Panel (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards); Koutsoumanis, K.; Allende, A.; Álvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Bolton, D.; Bover-Cid, S.; Chemaly, M.; Davies, R.; De Cesare, A.; Herman, L.; et al. Role played by the environment in the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) through the food chain. EFSA J. 2021, 19, e06651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marcantonio, L.; Chiatamone Ranieri, S.; Toro, M.; Marchegiano, A.; Cito, F.; Sulli, N.; Del Matto, I.; Di Lollo, V.; Alessiani, A.; Foschi, G.; et al. Comprehensive regional study of ESBL Escherichia coli: Genomic insights into antimicrobial resistance and inter-source dissemination of ESBL genes. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1595652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial consumption and resistance in bacteria from humans and food-producing animals. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e9237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langkabel, N.; Burgard, J.; Freter, S.; Fries, R.; Meemken, D.; Ellerbroek, L. Detection of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL) E. coli at Different Processing Stages in Three Broiler Abattoirs. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, N.; Käsbohrer, A.; Mayrhofer, S.; Zitz, U.; Hofacre, C.; Domig, K.J. The application of antibiotics in broiler production and the resulting antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli: A global overview. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 1791–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oguttu, J.W.; Veary, C.M.; Picard, J.A. Antimicrobial drug resistance of Escherichia coli isolated from poultry abattoir workers at risk and broilers on antimicrobials. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 2008, 79, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, A.; Bucur, I.M.; Imre, K.; Tirziu, A.T.; Ivan, A.A.; Gros, R.V.; Moza, A.C.; Popa, S.A.; Ban-Cucerzan, A.; Tirziu, E. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characterization of ESBL and AmpC β-Lactamase-Producing E. coli Isolates from Poultry in Northwestern Romania. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemlem, M.; Aklilu, E.; Mohamed, M.; Kamaruzzaman, N.F.; Devan, S.S.; Lawal, H.; Kanamma, A.A. Prevalence and molecular characterization of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli isolated from broiler chicken and their respective farms environment in Malaysia. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewers, C.; de Jong, A.; Prenger-Berninghoff, E.; Garch, F.E.; Leidner, U.; Tiwari, S.K.; Semmler, T. Genomic Diversity and Virulence Potential of ESBL- and AmpC-β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli Strains from Healthy Food Animals Across Europe. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 626774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandujano-Hernández, A.; Martínez-Vázquez, A.V.; Paz-González, A.D.; Herrera-Mayorga, V.; Sánchez-Sánchez, M.; Lara-Ramírez, E.E.; Vázquez, K.; de Jesús de Luna-Santillana, E.; Bocanegra-García, V.; Rivera, G. The Global Rise of ESBL-Producing Escherichia coli in the Livestock Sector: A Five-Year Overview. Animals 2024, 14, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolaia, V.; Bisgaard, M.; Bojesen, A.M. Distribution and possible transmission of ampicillin- and nalidixic acid-resistant Escherichia coli within the broiler industry. Vet. Microbiol. 2010, 142, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laconi, A.; Tolosi, R.; Chirollo, C.; Penon, C.; Berto, G.; Galuppo, F.; Piccirillo, A. From Farm to Slaughter: Tracing Antimicrobial Resistance in a Poultry Short Food Chain. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Smoglica, C.; Ruffini, F.; Soldati, L.; Marsilio, F.; Di Francesco, C.E. Antibiotic Resistance Genes Occurrence in Conventional and Antibiotic-Free Poultry Farming, Italy. Animals 2022, 12, 2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloeil, P.; Guerra, B.; Stoicescu, A. Manual for reporting on antimicrobial resistance within the framework of Directive 2003/99/EC and Decision 2013/652/EU for information derived from the year 2019. EFSA Support. Publ. 2020, 17, 1794E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority); Amore, G.; Beloeil, P.-A.; Garcia Fierro, R.; Guerra, B.; Rizzi, V.; Stoicescu, A.-V. Manual for reporting 2024 antimicrobial resistance data under Directive 2003/99/EC and Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2020/1729. EFSA Support. Publ. 2025, 22, 9238E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallenne, C.; da Costa, A.; Decré, D.; Favier, C.; Arlet, G. Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosavian, S.; Rezvani-Rad, A. Determining frequency of genes of CTX-M and CTX-M-15 of producing Enterobacteriaceae of isolated extended-spectrum beta-lactamases from clinical samples of patients referred to training hospitals of Medical Sciences University, Khorramabad, Iran. Int. J. Pharm. Investig. 2017, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Pérez, F.J.; Hanson, N.D. Detection of Plasmid-Mediated AmpC β-Lactamase Genes in Clinical Isolates by Using Multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 2153–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasman, H.; Mevius, D.; Veldman, K.; Olesen, I.; Aarestrup, F.M. β-Lactamases among extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-resistant Salmonella from poultry, poultry products and human patients in The Netherlands. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005, 56, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antimicrobial Resistance Remains Commonly Detected in Bacteria in Humans, Animals and Food: EFSA -ECDC Report|EFSA. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/press/news/140325?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- De Cesare, A.; Oliveri, C.; Lucchi, A.; Savini, F.; Manfreda, G.; Sala, C. Pilot Study on Poultry Meat from Antibiotic Free and Conventional Farms: Can Metagenomics Detect Any Difference? Foods 2022, 11, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, L.; Proietti, P.C.; Branciari, R.; Menchetti, L.; Bellucci, S.; Ranucci, D.; Marenzoni, M.L.; Franciosini, M.P. Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Escherichia coli and ESBL-Producing Escherichia coli Diffusion in Conventional, Organic and Antibiotic-Free Meat Chickens at Slaughter. Animals 2020, 10, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Projahn, M.; von Tippelskirch, P.; Semmler, T.; Guenther, S.; Alter, T.; Roesler, U. Contamination of chicken meat with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing- Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli during scalding and defeathering of broiler carcasses. Food Microbiol. 2019, 77, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jong, A.; Garch FEl Hocquet, D.; Prenger-Berninghoff, E.; Dewulf, J.; Migura-Garcia, L.; Perrin-Guyomard, A.; Veldman, K.T.; Janosi, S.; Skarzynska, M.; Simjee, S. European-wide antimicrobial resistance monitoring in commensal Escherichia coli isolated from healthy food animals between 2004 and 2018. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 3301–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silbergeld, E.K.; Graham, J.; Price, L.B. Industrial food animal production, antimicrobial resistance, and human health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2008, 29, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Bogaard, A.E.; Stobberingh, E.E. Epidemiology of resistance to antibiotics: Links between animals and humans. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2000, 14, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.; Ma, P.-P.; Liu, W.-S.; Liang, X.; Li, X.-Y.; Li, Y.-Z.; Liu, B.-T. Prevalence and Antibiotic Resistance Characteristics of Extraintestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli among Healthy Chickens from Farms and Live Poultry Markets in China. Animals 2021, 11, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.; Andersson, D.I. Environmental and genetic modulation of the phenotypic expression of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 374–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.A.; Besser, T.E.; Orfe, L.H.; Baker, K.N.K.; Lanier, A.S.; Broschat, S.L.; New, D.; Call, D.R. Genotypic-phenotypic discrepancies between antibiotic resistance characteristics of Escherichia coli isolates from calves in management settings with high and low antibiotic use. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 3293–3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eladawy, M.; Heslop, N.; Negus, D.; Thomas, J.C.; Hoyles, L. Phenotype–genotype discordance in antimicrobial resistance profiles of Gram-negative uropathogens recovered from catheter-associated urinary tract infections in Egypt. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, 3123–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viveiros, M.; Dupont, M.; Rodrigues, L.; Couto, I.; Davin-Regli, A.; Martins, M.; Pagès, J.M.; Amaral, L. Antibiotic stress, genetic response and altered permeability of E. coli. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyink, B.; von Haacke, H.; Reich, F.; Beterams, A.; Bandick, N.; Albert, T.; Südbeck, M.; Alter, T.; Kreienbrock, L.; Kirse, A. Microbiological contamination in broiler– a narrative overview on recent data and documentation in routine slaughter. Food Saf. Risk 2025, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Tippelskirch, P.; Gölz, G.; Projahn, M.; Daehre, K.; Friese, A.; Roesler, U.; Alter, T.; Orquera, S. Prevalence and quantitative analysis of ESBL and AmpC beta-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae in broiler chicken during slaughter in Germany. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 281, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).