Leishmaniavirus Type 1 Enhances In Vitro Infectivity and Modulates the Immune Response to Leishmania (Viannia) Isolates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Leishmania Isolates and Cell Lines

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Selection and Characterization of Leishmania Isolates

2.4. RNA Extraction and LRV-1 Detection

2.5. Macrophage Differentiation

2.6. In Vitro Infection Assay

2.7. Cytokine Quantification

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

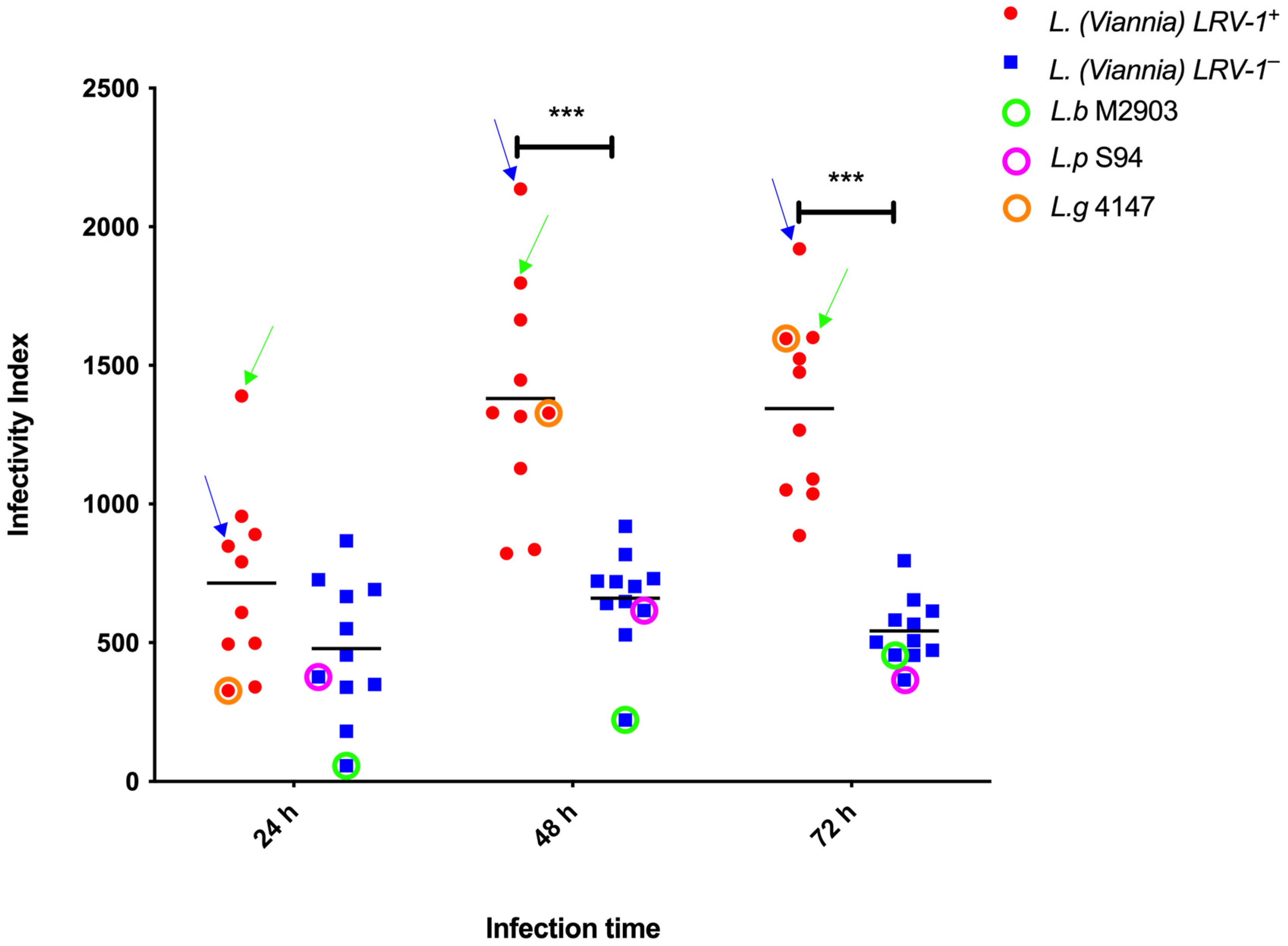

3.1. Infectivity Index (II) of Leishmania (Viannia) Isolates According to LRV-1 Status

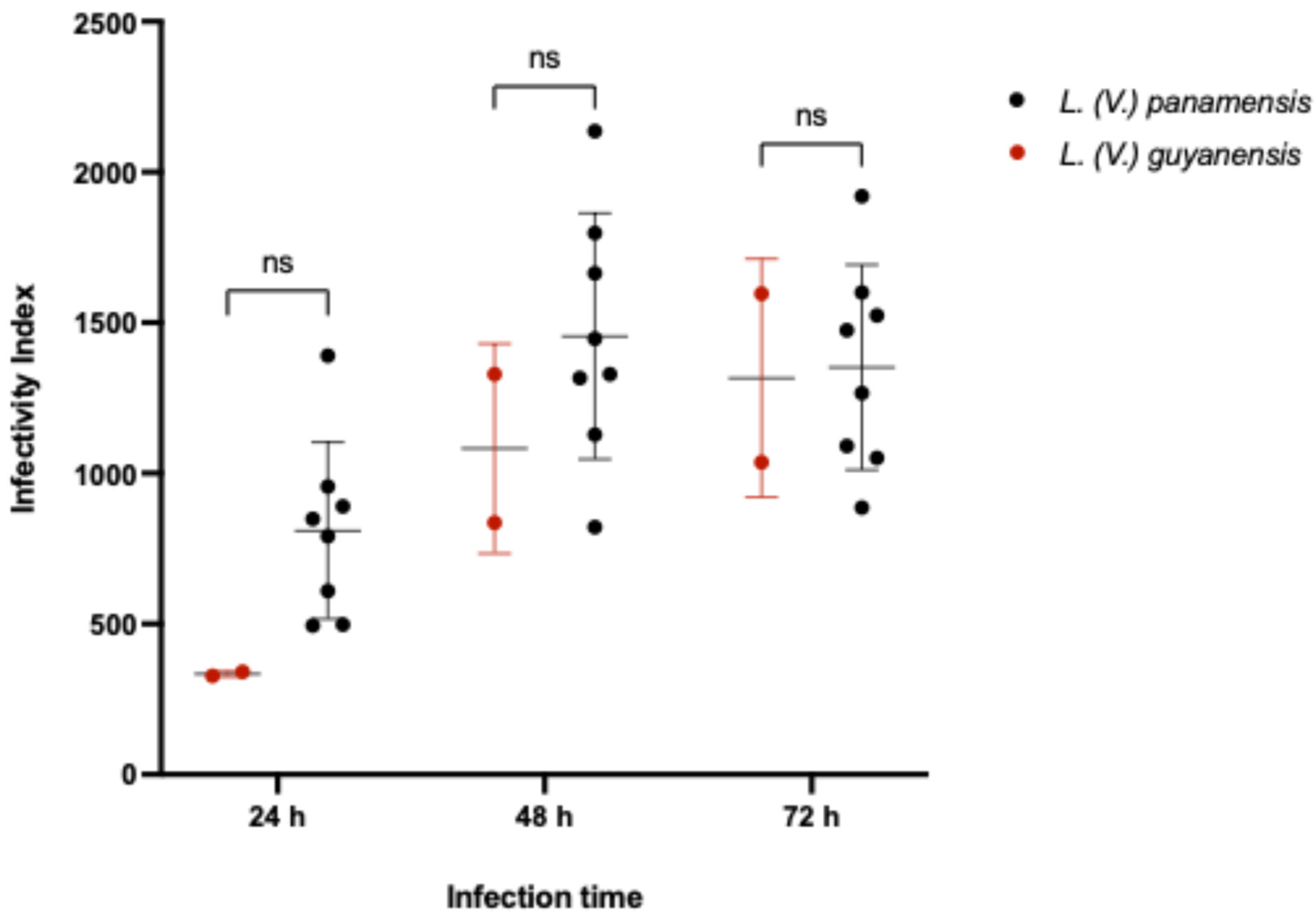

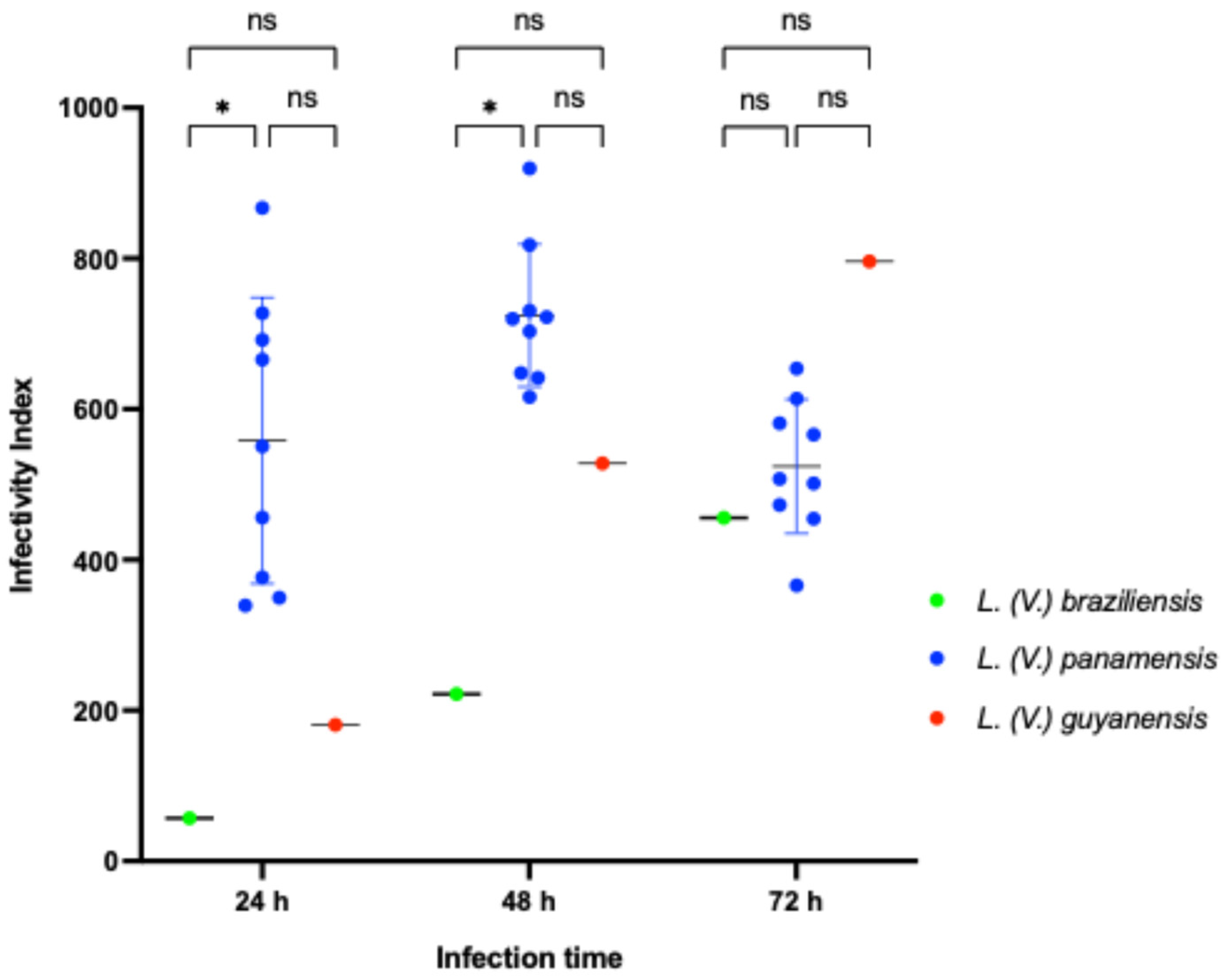

3.2. Infectivity Index (II) of Leishmania (Viannia) Isolates According to Species Stratification

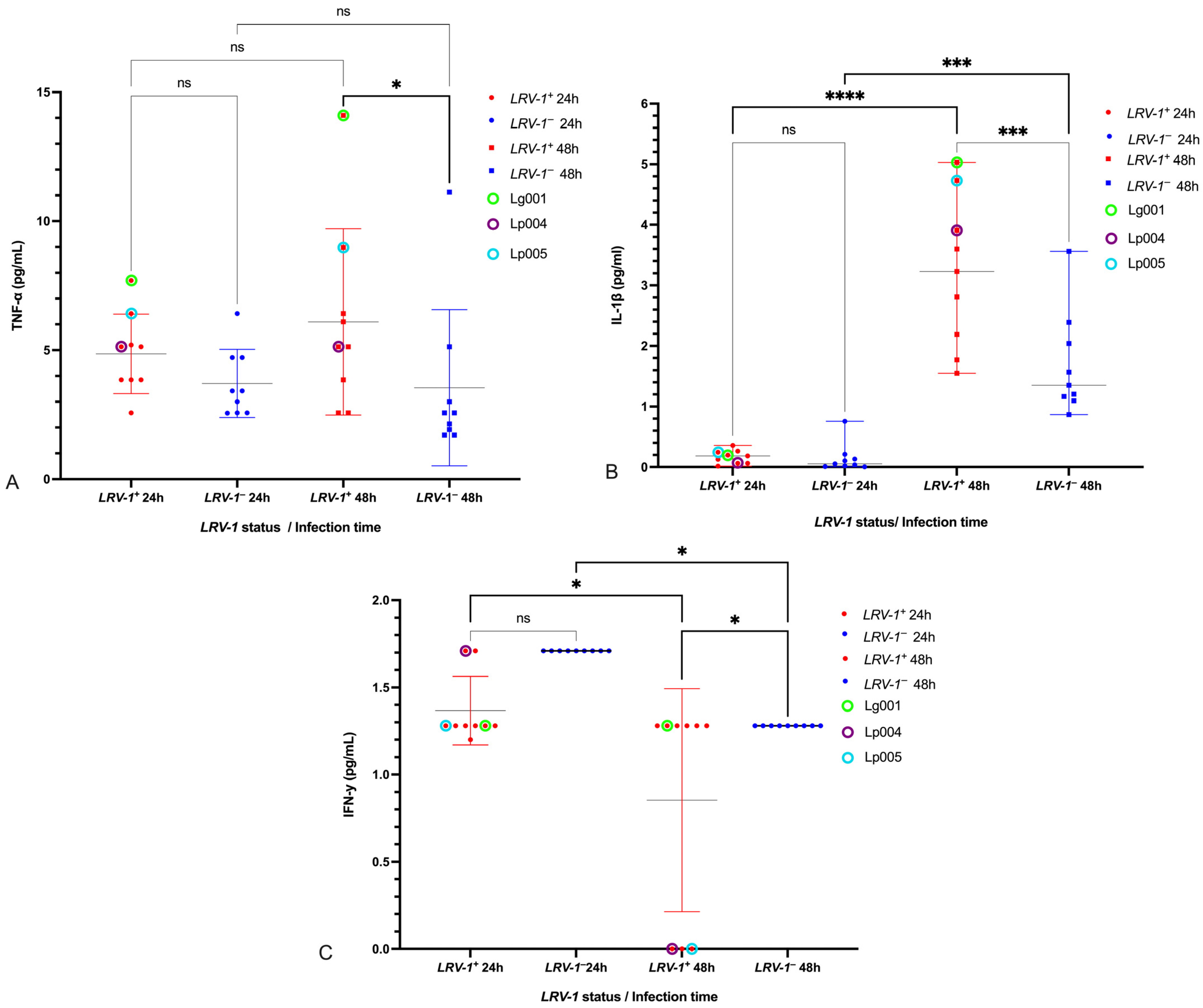

3.3. Modulation of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IFN-γ by LRV-1

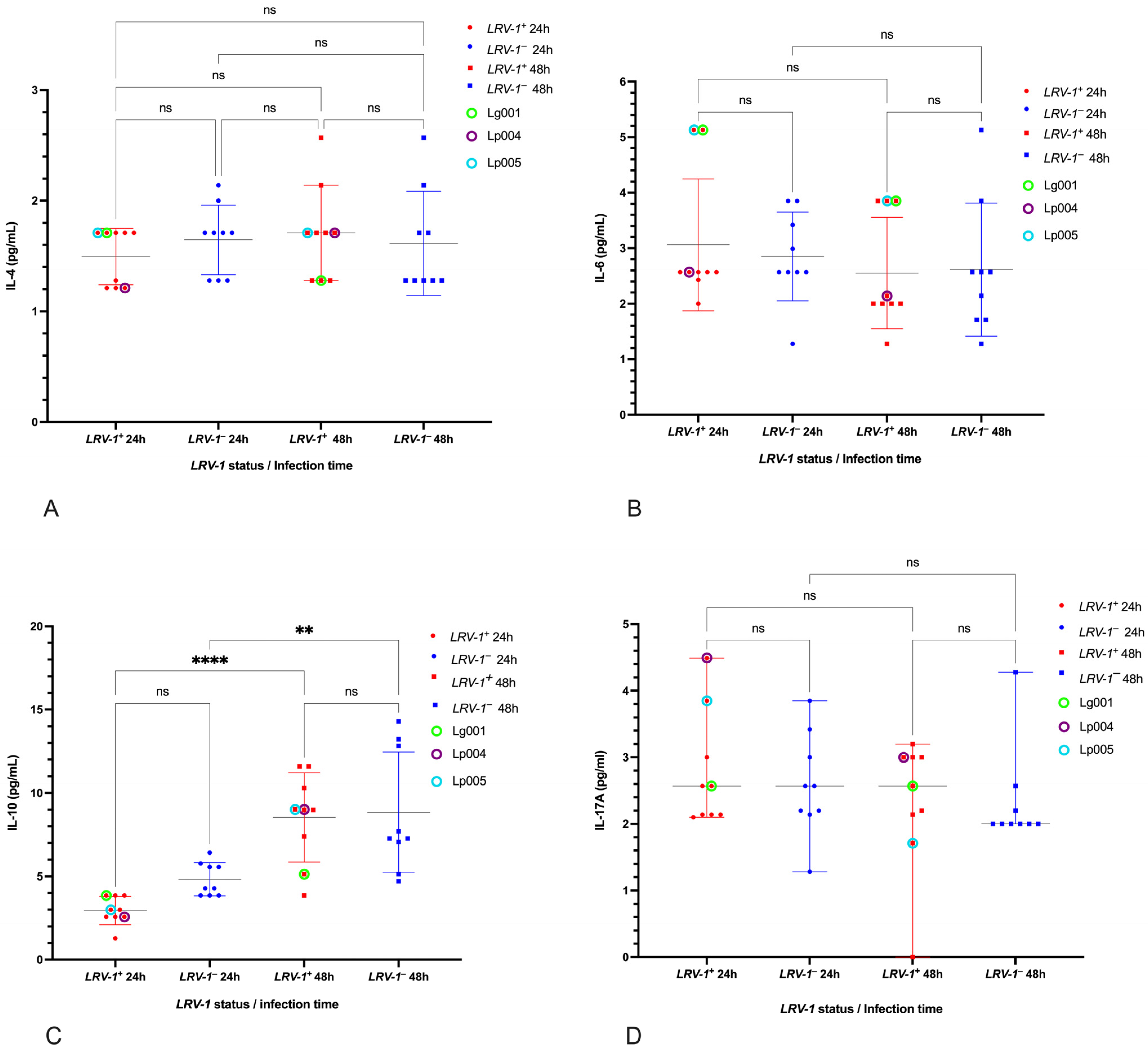

3.4. Cytokines Unaffected by LRV-1 Status

3.5. Cytokine Responses in Reference Strains and LPS Control

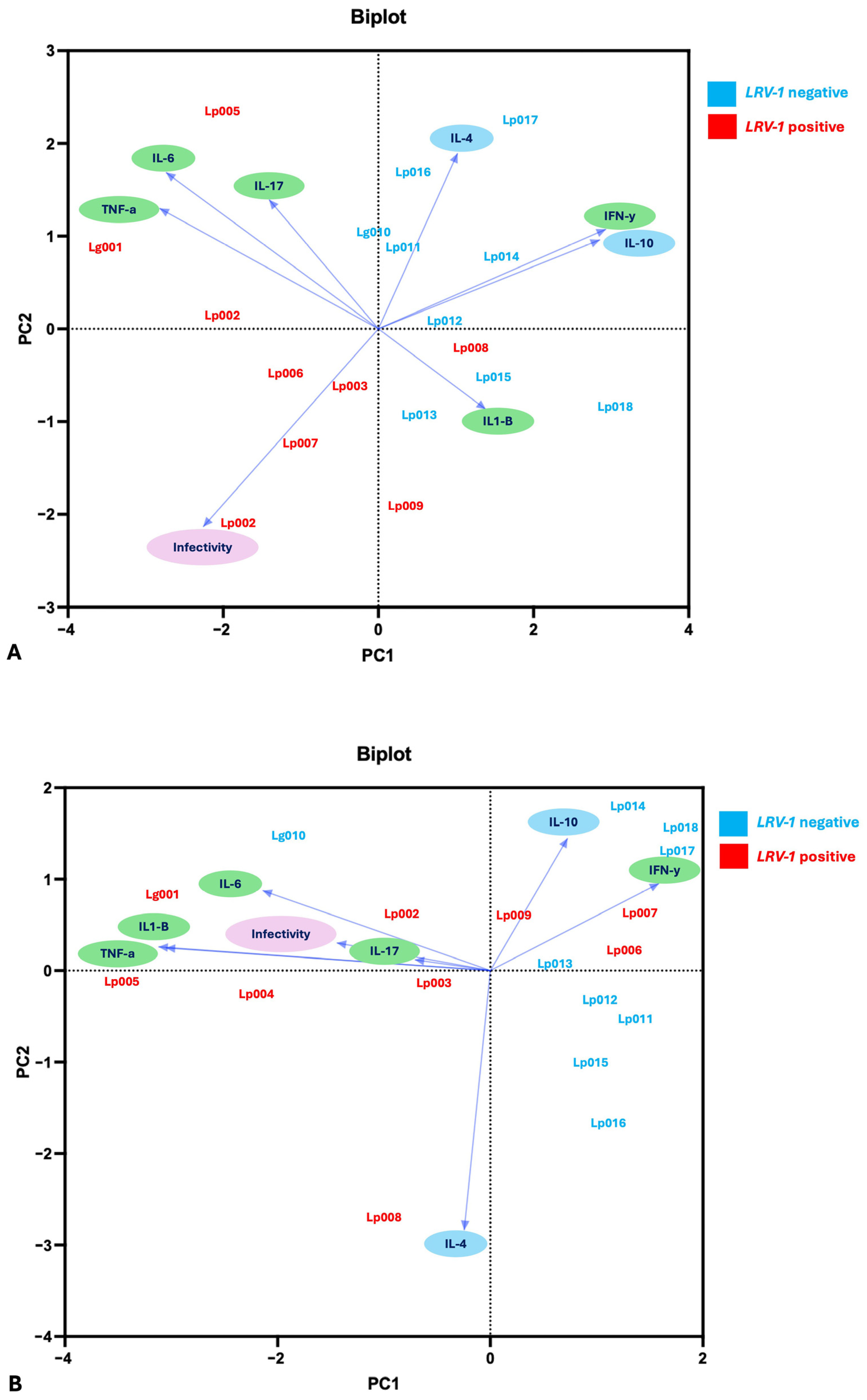

3.6. Multivariate and Correlation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LRV-1 | Leishmaniavirus type 1 |

| LRV-2 | Leishmaniavirus type 2 |

| CL | Cutaneous Leishmaniasis |

| LCL | Localized Cutaneous Leishmaniasis |

| II | Infection Index |

| TNF-α | Tumoral necrosis factor alpha |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

References

- Tarr, P.I.; Aline, R.F.; Smiley, B.L.; Scholler, J.; Keithly, J.; Stuart, K. LR1: A candidate RNA virus of Leishmania. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 9572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmer, G.; Comeau, A.M.; Furlong, D.B.; Wirth, D.F.; Patterson, J.L. Characterization of a RNA virus from the parasite Leishmania. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 5979–5982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widmer, G.; Dooley, S. Phylogenetic analysis of Leishmania RNA virus and Leishmania suggests ancient virus-parasite association. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995, 23, 2300–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheffter, S.M.; Ro, Y.T.; Chung, I.K.; Patterson, J.L. The Complete Sequence of Leishmania RNA Virus LRV2-1, a Virus of an Old World Parasite Strain. Virology 1995, 212, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.M.; Catanhêde, L.M.; Katsuragawa, T.H.; da Silva Junior, C.F.; Camargo, L.M.A.; Mattos Rde, G.; Vilallobos-Salcedo, J.M. Correlation between presence of Leishmania RNA virus 1 and clinical characteristics of nasal mucosal leishmaniosis. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 81, 533–540. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1808869415001056 (accessed on 7 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Cantanhêde, L.M.; da Silva Júnior, C.F.; Ito, M.M.; Felipin, K.P.; Nicolete, R.; Salcedo, J.M.V.; Porrozzi, R.; Cupolillo, E.; Ferreira, R.d.G.M. Further Evidence of an Association between the Presence of Leishmania RNA Virus 1 and the Mucosal Manifestations in Tegumentary Leishmaniasis Patients. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0004079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grybchuk, D.; Kostygov, A.Y.; Macedo, D.H.; Votýpka, J.; Lukeš, J.; Yurchenko, V. RNA Viruses in Blechomonas (Trypanosomatidae) and Evolution of Leishmaniavirus. mBio 2018, 9, e01932-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirera, S.; Ginouves, M.; Donato, D.; Caballero, I.S.; Bouchier, C.; Lavergne, A.; Bourreau, E.; Mosnier, E.; Vantilcke, V.; Couppié, P.; et al. Unraveling the genetic diversity and phylogeny of Leishmania RNA virus 1 strains of infected Leishmania isolates circulating in French Guiana. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristhine, M.; Santana, O.; Chourabi, K.; Cantanhede, L.M.; Cupolillo, E. Exploring Host-Specificity: Untangling the Relationship Between Leishmania (Viannia) Species and Its Endosymbiont Leishmania RNA Virus 1. 2023. Available online: www.preprints.org (accessed on 14 August 2023).

- Saberi, R.; Fakhar, M.; Mohebali, M.; Anvari, D.; Gholami, S. Global status of synchronizing Leishmania RNA virus in Leishmania parasites: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 2244–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klocek, D.; Grybchuk, D.; Tichá, L.; Votýpka, J.; Volf, P.; Kostygov, A.Y.; Yurchenko, V. Evolution of RNA viruses in trypanosomatids: New insights from the analysis of Sauroleishmania. Parasitol. Res. 2023, 122, 2279–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra-Rêgo, F.; Sérgio da Silva, E.; Valadares Lopes, V.; Gonçalves Teixeira-Neto, R.; Silva Belo, V.; Augusto Fonseca Júnior, A.; Andrade Pereira, D.; Paulino Pena, H.; Dalastra Laurenti, M.; Araújo Flores, G.V.; et al. First report of putative Leishmania RNA virus 2 (LRV2) in Leishmania infantum strains from canine and human visceral leishmaniasis cases in the southeast of Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2023, 118, e230071. [Google Scholar]

- Zolfaghari, A.; Beheshti-Maal, K.; Ahadi, A.M.; Monajemi, R. Identification of Leishmania species and frequency distribution of LRV1 and LRV2 viruses on cutaneous leishmaniasis patients in Isfahan Province, Iran. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2023, 41, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, R.V.H.; Lima-Junior, D.S.; da Silva, M.V.G.; Dilucca, M.; Rodrigues, T.S.; Horta, C.V.; Silva, A.L.N.; da Silva, P.F.; Frantz, F.G.; Lorenzon, L.B.; et al. Leishmania RNA virus exacerbates Leishmaniasis by subverting innate immunity via TLR3-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourreau, E.; Ginouves, M.; Prévot, G.; Hartley, M.A.; Gangneux, J.P.; Robert-Gangneux, F.; Robert-Gangneux, F.; Dufour, J.; Sainte-Marie, D.; Bertolotti, A.; et al. Presence of Leishmania RNA Virus 1 in Leishmania guyanensis Increases the Risk of First-Line Treatment Failure and Symptomatic Relapse. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 213, 105–111. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/infdis/jiv355 (accessed on 25 April 2021). [CrossRef]

- Adaui, V.; Lye, L.F.; Akopyants, N.S.; Zimic, M.; Llanos-Cuentas, A.; Garcia, L.; Maes, I.; De Doncker, S.; Dobson, D.E.; Arevalo, J.; et al. Association of the Endobiont Double-Stranded RNA Virus LRV1 With Treatment Failure for Human Leishmaniasis Caused by Leishmania braziliensis in Peru and Bolivia. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 213, 112–121. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/infdis/jiv354 (accessed on 26 January 2021). [CrossRef]

- Pazmiño, F.A.; Parra-Muñoz, M.; Saavedra, C.H.; Muvdi-Arenas, S.; Ovalle-Bracho, C.; Echeverry, M.C. Mucosal leishmaniasis is associated with the Leishmania RNA virus and inappropriate cutaneous leishmaniasis treatment. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariyawasam, R.; Lau, R.; Valencia, B.M.; Llanos-Cuentas, A.; Boggild, A.K. Leishmania RNA Virus 1 (LRV-1) in leishmania (viannia) braziliensis isolates from Peru: A description of demographic and clinical correlates. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 102, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, G.A.; Descoteaux, A. Macrophage cytokines: Involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front Immunol. 2014, 5, 491. [Google Scholar]

- Tomiotto-Pellissier, F.; da Silva Bortoleti, B.T.; Assolini, J.P.; Gonçalves, M.D.; Carloto, A.C.M.; Miranda-Sapla, M.M.; Conchon-Costa, I.; Bordignon, J.; Pavanelli, W.R. Macrophage Polarization in Leishmaniasis: Broadening Horizons. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.F.; Mosser, D.M. A novel phenotype for an activated macrophage: The type 2 activated macrophage. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2002, 72, 101–106. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12101268 (accessed on 1 November 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, D.O. Molecular interactions in macrophage activation. Immunol. Today 1989, 10, 33–35. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0167569989902983 (accessed on 11 November 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ives, A.; Ronet, C.; Prevel, F.; Ruzzante, G.; Fuertes-Marraco, S.; Schutz, F.; Zangger, H.; Revaz-Breton, M.; Lye, L.F.; Hickerson, S.M.; et al. Leishmania RNA virus controls the severity of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Science (1979) 2011, 331, 775–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangger, H.; Ronet, C.; Desponds, C.; Kuhlmann, F.M.; Robinson, J.; Hartley, M.A.; Prevel, F.; Castiglioni, P.; Pratlong, F.; Bastien, P.; et al. Detection of Leishmania RNA Virus in Leishmania Parasites. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, M.A.; Ronet, C.; Zangger, H.; Beverley, S.M.; Fasel, N. Leishmania RNA virus: When the host pays the toll. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 99. Available online: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fcimb.2012.00099/abstract (accessed on 11 November 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Carvalho, R.V.H.; Lima-Júnior, D.S.; de Oliveira, C.V.; Zamboni, D.S. Endosymbiotic RNA virus inhibits Leishmania-induced caspase-11 activation. iScience 2021, 24, 102004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eren, R.O.; Reverte, M.; Rossi, M.; Hartley, M.A.; Castiglioni, P.; Prevel, F.; Martin, R.; Desponds, C.; Lye, L.F.; Drexler, S.K.; et al. Mammalian Innate Immune Response to a Leishmania-Resident RNA Virus Increases Macrophage Survival to Promote Parasite Persistence. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 318–328. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1931312816303456 (accessed on 7 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Felipin, K.P.; Paloschi, M.V.; Silva, M.D.S.; Ikenohuchi, Y.J.; Santana, H.M.; Setúbal Sda, S.; Rego, C.M.A.; Lopes, J.A.; Boeno, C.N.; Serrath, S.N.; et al. Transcriptomics analysis highlights potential ways in human pathogenesis in Leishmania braziliensis infected with the viral endosymbiont LRV1. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariyawasam, R.; Grewal, J.; Lau, R.; Purssell, A.; Valencia, B.M.; Llanos-Cuentas, A.; Boggild, A.K. Influence of Leishmania RNA Virus 1 on Proinflammatory Biomarker Expression in a Human Macrophage Model of American Tegumentary Leishmaniasis. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 216, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilbride, L.; Myler, P.J.; Stuart, K. Distribution and sequence divergence of LRV1 viruses among different Leishmania species. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1992, 54, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira-Gonçalves, R.; Fagundes-Silva, G.A.; Heringer, J.F.; Fantinatti, M.; Da-Cruz, A.M.; Oliveira-Neto, M.P.; Guerra, J.A.O.; Gomes-Silva, A. First report of treatment failure in a patient with cutaneous leishmaniasis infected by Leishmania (Viannia) naiffi carrying Leishmania RNA virus: A fortuitous combination? Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2019, 52, e20180323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginouvès, M.; Simon, S.; Bourreau, E.; Lacoste, V.; Ronet, C.; Couppié, P.; Nacher, M.; Demar, M.; Prévot, G. Prevalence and distribution of Leishmania RNA virus 1 in leishmania parasites from French Guiana. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 94, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shita, E.Y.; Semegn, E.N.; Wubetu, G.Y.; Abitew, A.M.; Andualem, B.G.; Alemneh, M.G. Prevalence of Leishmania RNA virus in Leishmania parasites in patients with tegumentary leishmaniasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, G.; Zamora, M.; Stuart, K.; Saravia, N. Leishmania RNA Viruses in Leishmania of the Viannia Subgenus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1996, 54, 425–429. Available online: https://www.ajtmh.org/view/journals/tpmd/54/4/article-p425.xml (accessed on 23 April 2021). [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Ramos Pereira, L.; Maretti-Mira, A.C.; Rodrigues, K.M.; Lima, R.B.; de Oliveira-Neto, M.P.; Cupolillo, E.; Pirmez, C.; de Oliveira, M.P. Severity of tegumentary leishmaniasis is not exclusively associated with Leishmania RNA virus 1 infection in Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2013, 108, 665–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonilla, A.A.; Pineda, V.; Calzada, J.E.; Saldaña, A.; Dalastra Laurenti, M.; Goya, S.; Abrego, L.; González, K. Epidemiology and Genetic Characterization of Leishmania RNA Virus in Leishmania (Viannia) spp. Isol. Cutan. Leishmaniasis Endem. Areas Panama 2024, 12, 1317. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, K.; De León, S.S.; Pineda, V.; Samudio, F.; Capitan-Barrios, Z.; Suarez, J.A.; Weeden, A.; Ortiz, B.; Rios, M.; Moreno, B.; et al. Detection of Leishmania RNA Virus 1 in Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis Isolates, Panama. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 1250–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan American Health Organization. Leishmaniasis: Epidemiological Report for the Americas Washinton, D.C. 2024. Available online: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/51742 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Vásquez, A.; Paz, H.; Alvar, J.; Perez, D.; Hernandez, C. Informe Final: Estudios Sobre la Epidemiología de la Leishmaniasis Panamá, en la parte Occidental de la República de Panamá; Instituto Conmemorativo Gorgas de Estudio de la Salud, INSA: Panama City, Panama, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Freites, C.O.; Gundacker, N.D.; Pascale, J.M.; Saldaña, A.; Diaz-Suarez, R.; Jimenez, G.; Sosa, N.; García, E.; Jimenez, A.; Suarez, J.A. First case of diffuse leishmaniasis associated with leishmania panamensis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2018, 5, ofy281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, J.; Estripeaut, D.; Diaz, Y.; Pachar Flores, M.R.; Hernandez, C.; Garcia-Redondo, R.; Lozano-Durán, D.; Ramirez, J.D.; Suárez, J.A.; Paniz-Mondolfi, A. Borderline Disseminated (Intermediate) Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A Case-Based Approach to Diagnosis and Clinical Management in Pediatric Population. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2025, 44, e258–e264. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/10.1097/INF.0000000000004761 (accessed on 2 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- de Vasquez, A.M.; Christensen, H.A.; Petersen, J.L. Short report epidemiologic studies on cutaneous leishmaniasis in eastern Panama. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1999, 60, 54–57. Available online: https://www.ajtmh.org/view/journals/tpmd/60/1/article-p54.xml (accessed on 5 July 2021). [CrossRef]

- Kariyawasam, R.; Lau, R.; Valencia, B.M.; Llanos-Cuentas, A.; Boggild, A.K. Novel detection of Leishmania RNA virus-1 (LRV-1) in clinical isolates of Leishmania Viannia panamensis. Parasitology 2023, 151, 151–156. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0031182023001221/type/journal_article (accessed on 5 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, A.M.; Fraga, J.; Maes, I.; Dujardin, J.C.; Van der Auwera, G. Three new sensitive and specific heat-shock protein 70 PCRs for global Leishmania species identification. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 31, 1453–1461. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22083340 (accessed on 12 April 2019). [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, E.S.; Jesus, J.A.; Bezerra-Souza, A.; Laurenti, M.D.; Ribeiro, S.P.; Passero, L.F.D. Activity of Fenticonazole, Tioconazole and Nystatin on New World Leishmania Species. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2018, 18, 2338–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arena, A.; Capozza, A.B.; Delfino, D.; Iannello, D. Production of TNF alpha and interleukin 6 by differentiated u937 cells infected with leishmama major. Microbiologica 1997, 20, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hartley, M.A.; Bourreau, E.; Rossi, M.; Castiglioni, P.; Eren, R.O.; Prevel, F.; Couppié, P.; Hickerson, S.M.; Launois, P.; Beverley, S.M.; et al. Leishmaniavirus-Dependent Metastatic Leishmaniasis Is Prevented by Blocking IL-17A. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reithinger, R.; Dujardin, J.C.; Louzir, H.; Pirmez, C.; Alexander, B.; Brooker, S. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2007, 7, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strazzulla, A.; Cocuzza, S.; Pinzone, M.R.; Postorino, M.C.; Cosentino, S.; Serra, A.; Cacopardo, B.; Nunnari, G. Mucosal Leishmaniasis: An Underestimated Presentation of a Neglected Disease. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 805108. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3703408/ (accessed on 3 December 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llanes, A.; Restrepo, C.M.; Vecchio GDel Anguizola, F.J.; Lleonart, R. The genome of Leishmania panamensis: Insights into genomics of the L. (Viannia) subgenus. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8550. Available online: http://www.nature.com/articles/srep08550 (accessed on 18 October 2019). [CrossRef]

- Montalvo Alvarez, A.M.; Nodarse, J.F.; Goodridge, I.M.; Fidalgo, L.M.; Marin, M.; Van Der Auwera, G.; Dujardin, J.C.; Bernal, I.D.V.; Muskus, C. Differentiation of Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis and Leishmania (V.) guyanensis using BccI for hsp70 PCR-RFLP. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 104, 364–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, N.; Blaizot, R.; Prévot, G.; Aoun, K.; Demar, M.; Cazenave, P.A.; Bouratbine, A.; Pied, S. Clinical and immunological spectra of human cutaneous leishmaniasis in North Africa and French Guiana. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1134020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Ochoa, W.; Zúniga, C.; Chaves, L.F.; Flores, G.V.A.; Pacheco, C.M.S.; da Matta, V.L.R.; Corbett, C.E.P.; Silveira, F.T.; Laurenti, M.D. Clinical and immunological features of human Leishmania (L.) infantum-infection, novel insights Honduras, central america. Pathogens 2020, 9, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, M.; Pineda, V.; Calzada, J.E.; Saldaña, A.; Samudio, F. Evaluation of cytochrome b sequence to identify leishmania species and variants: The case of Panama. Mem. Do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2021, 116, e200572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendieta, D.; Vásquez, V.; Jaén, L.; Pineda, V.; Saldaña, A.; Calzada, J.E.; Samudio, F. Insights into the Genetic Diversity of Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis in Panama, Inferred via Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST). Pathogens 2023, 12, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liese, J.; Schleicher, U.; Bogdan, C. The innate immune response against Leishmania parasites. Immunobiology 2008, 213, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, I.; Ferreira, C.; Barbosa, A.M.; Ferreira, C.M.; Moreira, D.; Carvalho, A.; Cunha, C.; Rodrigues, F.; Dinis-Oliveira, R.J.; Estaquier, J.; et al. The impact of IL-10 dynamic modulation on host immune response against visceral leishmaniasis. Cytokine 2018, 112, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval Pacheco, C.M.; Araujo Flores, G.V.; Gonzalez, K.; De Castro Gomes, C.M.; Passero, L.F.D.; Tomokane, T.Y.; Sosa-Ochoa, W.; Zúniga, C.; Calzada, J.; Saldaña, A.; et al. Macrophage Polarization in the Skin Lesion Caused by Neotropical Species of Leishmania sp. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 202, 5596876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, P.; Novais, F.O. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: Immune responses in protection and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, S.; Shankar, P.; Mishra, J.; Singh, S. Possibilities and challenges for developing a successful vaccine for leishmaniasis. Parasites Vectors 2016, 9, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockhart, E.; Green, A.M.; Flynn, J.L. IL-17 Production Is Dominated by γδ T Cells rather than CD4 T Cells during Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 4662–4669. Available online: http://www.jimmunol.org/lookup/doi/10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4662 (accessed on 15 September 2019). [CrossRef]

- Ghoreschi, K.; Laurence, A.; Yang, X.P.; Tato, C.M.; McGeachy, M.J.; Konkel, J.E.; Ramos, H.L.; Wei, L.; Davidson, T.S.; Bouladoux, N.; et al. Generation of pathogenic TH17 cells in the absence of TGF-β signalling. Nature 2010, 467, 967–971. Available online: http://www.nature.com/articles/nature09447 (accessed on 6 January 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Isolate ID | Leishmania Species | LRV-1 Status | Isolate Description | Origin | Lesions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lg001 | L. (V.) guyanensis | LRV-1+ | Group 1 | COC, PA | 1 |

| Lp002 | L. (V.) panamensis | LRV-1+ | Group 1 | DA, PA | 1 |

| Lp003 | L. (V.) panamensis | LRV-1+ | Group 1 | COL, PA | 4 |

| Lp004 | L. (V.) panamensis | LRV-1+ | Group 1 | PAC, PA | 11 |

| Lp005 | L. (V.) panamensis | LRV-1+ | Group 1 | COL, PA | 1 ^ |

| Lp006 | L. (V.) panamensis | LRV-1+ | Group 1 | PO, PA | 1 |

| Lp007 | L. (V.) panamensis | LRV-1+ | Group 1 | COL, PA | 1 |

| Lp008 | L. (V.) panamensis | LRV-1+ | Group 1 | BT, PA | 1 |

| Lp009 | L. (V.) panamensis | LRV-1+ | Group 1 | BT, PA | 1 |

| Lg010 | L. (V.) guyanensis | LRV-1− | Group 2 | PO, PA | 1 |

| Lp011 | L. (V.) panamensis | LRV-1− | Group 2 | COL, PA | 1 |

| Lp012 | L. (V.) panamensis | LRV-1− | Group 2 | VE, PA | 1 |

| Lp013 | L. (V.) panamensis | LRV-1− | Group 2 | PA, PA | 1 |

| Lp014 | L. (V.) panamensis | LRV-1− | Group 2 | BT, PA | 1 |

| Lp015 | L. (V.) panamensis | LRV-1− | Group 2 | DA, PA | 2 |

| Lp016 | L. (V.) panamensis | LRV-1− | Group 2 | PA, PA | 5 |

| Lp017 | L. (V.) panamensis | LRV-1− | Group 2 | PO, PA | 2 |

| Lp018 | L. (V.) panamensis | LRV-1− | Group 2 | COL, PA | 1 |

| Lg4147 (MHOM/BR/1975/WR4147) | L. (V.) guyanensis | LRV-1+ | Reference strain | BR | N/A |

| Lb566 (MHOM/BR/1975/M2903) | L. (V.) braziliensis | LRV-1− | Reference strain | BR | N/A |

| LpS94 (MHOM/PA/1971/LS94) | L. (V.) panamensis | LRV-1− | Reference strain | PA | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bonilla Fong, A.A.; Pineda, V.J.; Calzada, J.E.; Laurenti, M.D.; Passero, L.F.D.; Beltran, D.; Chaves, L.F.; Saldaña, A.; González, K. Leishmaniavirus Type 1 Enhances In Vitro Infectivity and Modulates the Immune Response to Leishmania (Viannia) Isolates. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121263

Bonilla Fong AA, Pineda VJ, Calzada JE, Laurenti MD, Passero LFD, Beltran D, Chaves LF, Saldaña A, González K. Leishmaniavirus Type 1 Enhances In Vitro Infectivity and Modulates the Immune Response to Leishmania (Viannia) Isolates. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121263

Chicago/Turabian StyleBonilla Fong, Armando A., Vanessa J. Pineda, José E. Calzada, Marcia Dalastra Laurenti, Luiz Felipe Domingues Passero, Davis Beltran, Luis Fernando Chaves, Azael Saldaña, and Kadir González. 2025. "Leishmaniavirus Type 1 Enhances In Vitro Infectivity and Modulates the Immune Response to Leishmania (Viannia) Isolates" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121263

APA StyleBonilla Fong, A. A., Pineda, V. J., Calzada, J. E., Laurenti, M. D., Passero, L. F. D., Beltran, D., Chaves, L. F., Saldaña, A., & González, K. (2025). Leishmaniavirus Type 1 Enhances In Vitro Infectivity and Modulates the Immune Response to Leishmania (Viannia) Isolates. Pathogens, 14(12), 1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121263