Epidemiological, Diagnostic, and Clinical Features of Intracranial Cystic Echinococcosis: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

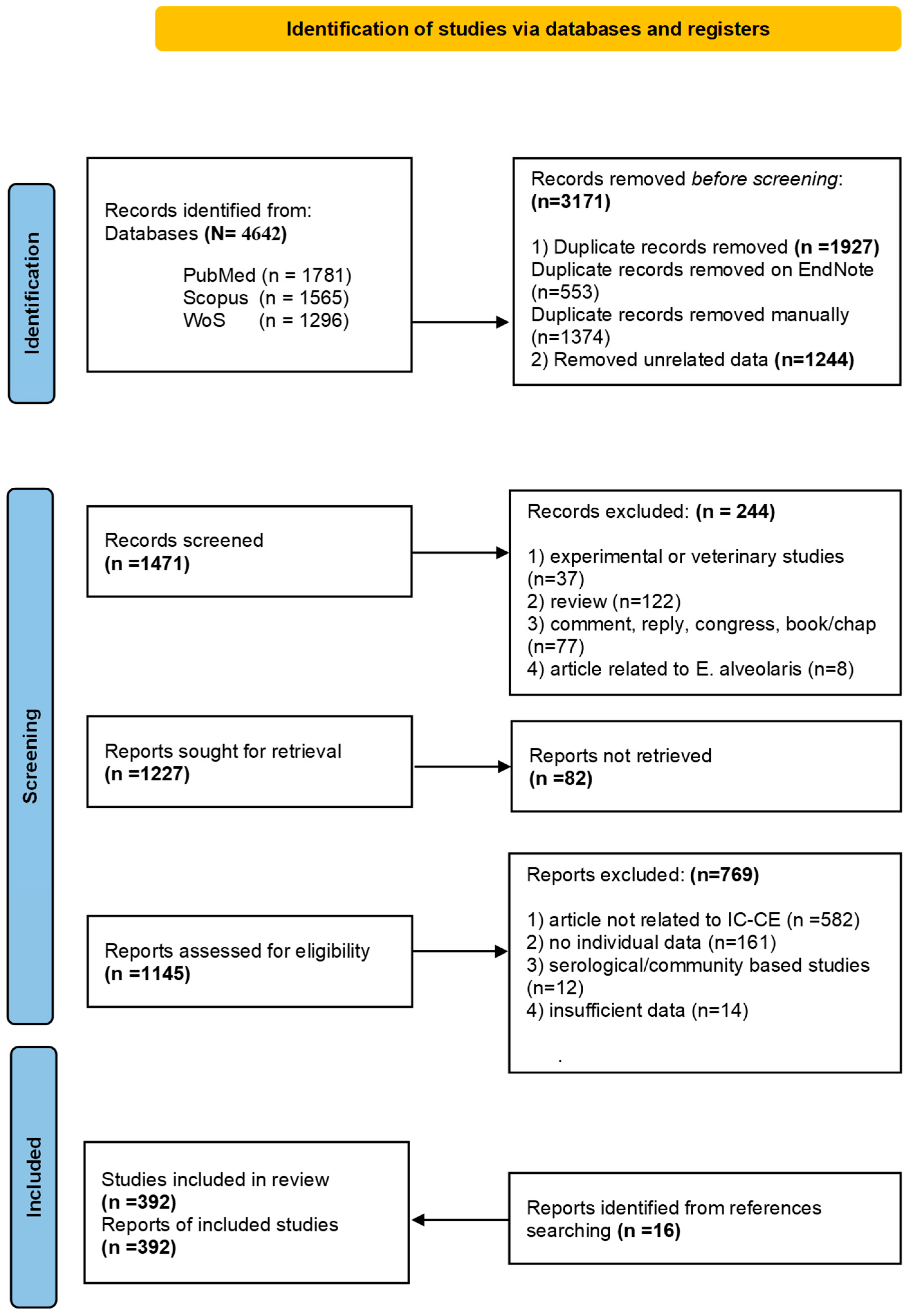

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.3. Risk of Bias (Quality) Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

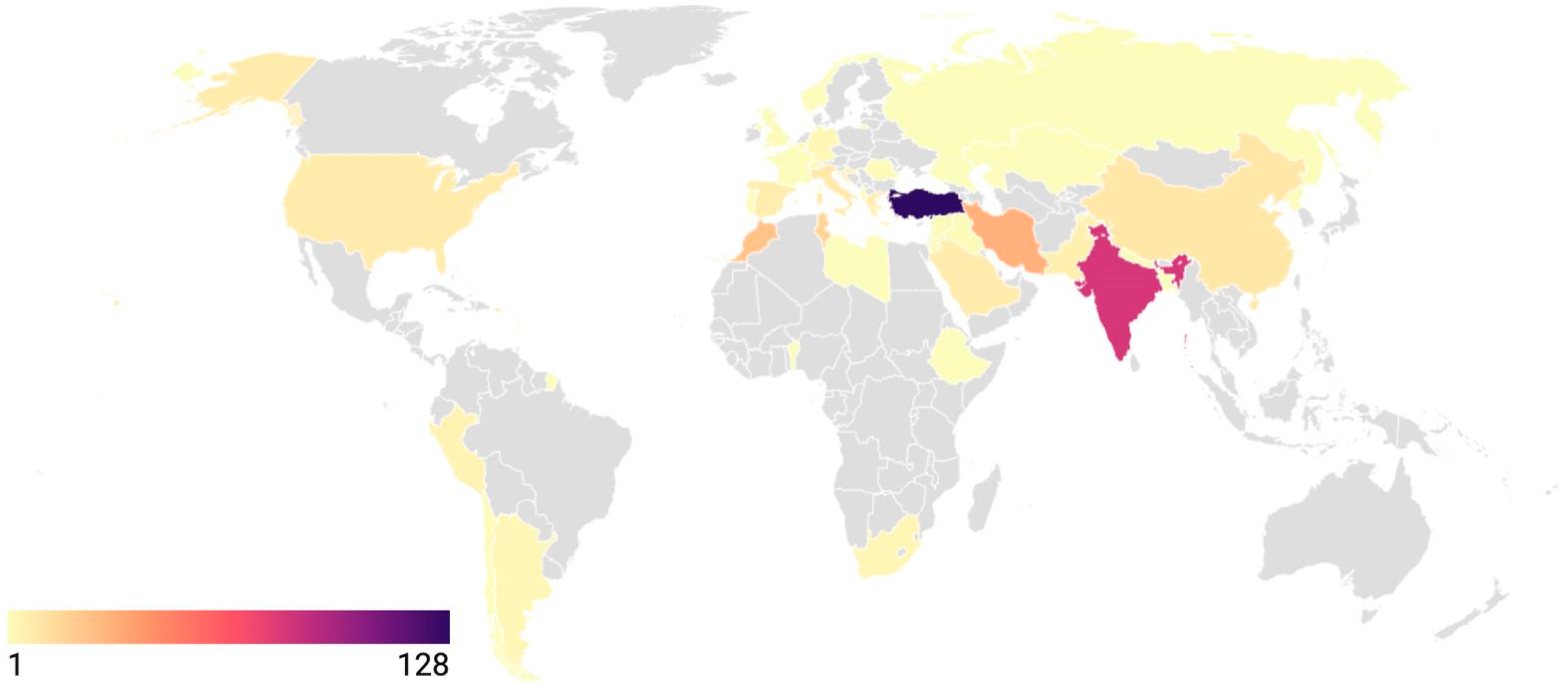

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Clinical Features and Diagnostic Characteristics

3.3. Anatomical Locations

3.4. Overview of Treatment Methods for Intracranial Hydatid Cysts

3.5. Clinical Outcome and Follow-Up

4. Discussion

5. Limitations of Our Study

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CE | Cystic echinococcosis |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| PAIR | Puncture, Aspiration, Injection, Reaspiration |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis |

| PROSPERO | Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| WoS | Web of Science |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Echinococcosis. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/echinococcosis (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Echinococcosis. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/echinococcosis/index.html (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Pawlowski, Z.; Eckert, J.; Vuitton, D.A.; Ammann, R.W.; Kern, P.; Craig, P.S.; Dar, K.F.; Rosa, F.; Filice, C.; Gottstein, B.; et al. Echinococcosis in humans: Clinical aspects, diagnosis and treatment. In WHO/OIE Manual on Echinococcosis in Humans and Animals: A Public Health Problem of Global Concern; Office International des Épizooties: Paris, France, 2001; pp. 20–71. [Google Scholar]

- Casulli, A.; Pane, S.; Randi, F.; Scaramozzino, P.; Carvelli, A.; Marras, C.E.; Carai, A.; Santoro, A.; Santolamazza, F.; Tamarozzi, F.; et al. Primary cerebral cystic echinococcosis in a child from Roman countryside: Source attribution and scoping review of cases from the literature. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altinörs, N.; Bavbek, M.; Caner, H.H.; Erdogan, B. Central nervous system hydatidosis in Turkey: A cooperative study and literature survey analysis of 458 cases. J. Neurosurg. 2000, 93, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaradat, J.H.; Alkhawaldeh, I.M.; Nashwan, A.J.; Al-Bojoq, Y.; Ramadan, M.N.; Albalkhi, I. Diagnosis and Management Approaches for Cerebellar Hydatid Cysts: A Systematic Review of Cases. Cureus 2024, 16, e59706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limaiem, F.; Kchir, N. Hydatidosis of the Brain. In Hydatidosis of the Central Nervous System: Diagnosis and Treatment; Turgut, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, M.; Sehgal, R.; Fomda, B.A.; Malhotra, A.; Malla, N. Molecular characterization of Echinococcus granulosus cysts in north Indian patients: Identification of G1, G3, G5 and G6 genotypes. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadjjadi, S.M.; Mikaeili, F.; Karamian, M.; Maraghi, S.; Sadjjadi, F.S.; Shariat-Torbaghan, S.; Kia, E.B. Evidence that the Echinococcus granulosus G6 genotype has an affinity for the brain in humans. Int. J. Parasitol. 2013, 43, 875–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantzanou, M.; Karalexi, M.A.; Vassalos, C.M.; Kostare, G.; Vrioni, G.; Tsakris, A. Central nervous system cystic echinococcosis: A systematic review. Germs 2022, 12, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padayachy, L.C.; Ozek, M.M. Hydatid disease of the brain and spine. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2023, 39, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhopadhyay, N.N. Perspective Chapter: Echinococcosis—An Updated Review. In Echinococcosis—New Perspectives; Inceboz, T., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Yugoslavia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Benzagmout, M.; Himmiche, M. Hydatidosis of the Central Nervous System in Mediterranean Countries and the Middle East. In Hydatidosis of the Central Nervous System: Diagnosis and Treatment; Turgut, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Tlili-Graiess, K.; El-Ouni, F.; Gharbi-Jemni, H.; Arifa, N.; Moulahi, H.; Mrad-Dali, K.; Guesmi, H.; Abroug, S.; Yacoub, M.; Krifa, H. Cerebral hydatid disease: Imaging features. J. Neuroradiol. 2006, 33, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razek, A.; Elshamam, O. Imaging of Cerebral Hydatid Disease. In Hydatidosis of the Central Nervous System: Diagnosis and Treatment; Turgut, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 133–141. [Google Scholar]

- Kharosekar, H.; Bhide, A.; Rathi, S.; Sawardekar, V. Primary Multiple Intracranial Extradural Hydatid Cysts: A Rare Entity Revisited. Asian J. Neurosurg. 2020, 15, 766–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dlamini, S.; Ntusi, N. Chemotherapy for Central Nervous System Hydatidosis. In Hydatidosis of the Central Nervous System: Diagnosis and Treatment; Turgut, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, F. Complications of Cerebral Hydatidosis. In Hydatidosis of the Central Nervous System: Diagnosis and Treatment; Turgut, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 193–213. [Google Scholar]

- Duishanbai, S.; Jiafu, D.; Guo, H.; Liu, C.; Liu, B.; Aishalong, M.; Mijiti, M.; Wen, H. Intracranial hydatid cyst in children: Report of 30 cases. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2010, 26, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cataltepe, O.; Tahta, K.; Colak, A.; Erbengi, A. Primary multiple cerebral hydatid cysts. Neurosurg. Rev. 1991, 14, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turgut, M. Intracranial hydatidosis in Turkey: Its clinical presentation, diagnostic studies, surgical management, and outcome. A review of 276 cases. Neurosurg. Rev. 2001, 24, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, G.; Li, Y.; Wu, P.; Wang, X.; Su, R.; Fan, Y.; Geng, D. Diagnosis, treatment, and misdiagnosis analysis of 28 cases of central nervous system echinococcosis. Chin. Neurosurg. J. 2021, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duran, E.; Pehlivan, B. Factors increasing mortality in Echinococcosis patients treated percutaneously or surgically. A review of 1,143 patients: A retrospective single center study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izci, Y.; Tuzun, Y.; Secer, H.I.; Gonul, E. Cerebral hydatid cysts: Technique and pitfalls of surgical management. Neurosurg. Focus. 2008, 24, E15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onal, C.; Unal, F.; Barlas, O.; Izgi, N.; Hepgul, K.; Turantan, M.I.; Canbolat, A.; Turker, K.; Bayindir, C.; Gokay, H.K.; et al. Long-term follow-up and results of thirty pediatric intracranial hydatid cysts: Half a century of experience in the Department of Neurosurgery of the School of Medicine at the University of Istanbul (1952–2001). Pediatr. Neurosurg. 2001, 35, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunardi, P.; Missori, P.; Di Lorenzo, N.; Fortuna, A. Cerebral hydatidosis in childhood: A retrospective survey with emphasis on long-term follow-up. Neurosurgery 1991, 29, 515–517; discussion 517–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Cases (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| All Cases (N = 718) | Adult Patients (n = 251) | Paediatric Patients * (n = 467) | |

| Age Mean ± SD | 17.9 ± 14.3 | 33.5 ± 13.5 | 9.5 ± 3.7 |

| Gender (No Data) | 7 | 3 | 4 |

| Female Male | 290 (40.8) 421 (59.2) | 104 (41.9) 144 (58.1) | 186 (40.2) 277 (59.8) |

| Symptoms and Signs ** | (n = 680) | (n = 242) | (n = 438) |

| Increased Intracranial Pressure Signs Headache Nausea and Vomiting Papilledema Motor Neurological Deficits and Findings Visual Abnormalities Seizure/Convulsion Coordination and Balance Disturbances Altered Consciousness Cognitive or Mental Status Alterations Speech and Language Disorders Others | 540 (79.4) 396 (58.2) 241 (35.6) 190 (27.9) 258 (37.9) 158 (23.2) 147 (21.6) 99 (14.6) 66 (9.7) 41 (6.0) 37 (5.4) 79 (11.6) | 190 (78.5) 171 (70.7) 88 (36.4) 45 (18.6) 85 (35.1) 54 (22.3) 58 (24.0) 43 (17.8) 28 (11.6) 20 (8.3) 12 (5.0) 31 (12.8) | 350 (79.9) 225 (51.4) 153 (34.9) 145 (33.1) 173 (39.5) 104 (23.7) 89 (20.3) 56 (12.8) 38 (8.7) 21 (4.8) 25 (5.7) 48 (11.0) |

| Serology | (n = 168) | (n = 69) | (n = 99) |

| Positive Negative | 95 (56.6) 73 (43.4) | 49 (71.0) 20 (29.0) | 46 (46.5) 53 (53.5) |

| Eosinophilia | (n = 82) | (n = 34) | (n = 48) |

| Positive Negative | 33 (40.2) 49 (59.8) | 16 (47.1) 18 (52.9) | 17 (35.4) 31 (64.6) |

| Imaging Modalities Performed ** | (n = 671) | (n = 247) | (n = 424) |

| Cranial CT Cranial MRI Cranial Plain Radiography Others | 540 (80.5) 403 (60.1) 72 (10.7) 28 (4.6) | 196 (79.4) 174 (70.4) 15 (6.1) 6 (2.4) | |

| Maximum Cyst Diameter at Diagnosis *** | (n = 377) | (n = 117) | (n = 260) |

| <5 cm ≥5 cm | 111 (29.4) 266 (70.6) | 47 (40.2) 70 (59.8) | 64 (24.6) 196 (75.4) |

| Cyst Morphology | (n = 705) | (n = 243) | (n = 462) |

| Single Multiple | 497 (70.5) 208 (29.5) | 122 (50.2) 121 (49.8) | 375 (81.2) 87 (18.8) |

| Region (N = 798) | Anatomical Distribution | Total (%) | Localization (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left | Right | No Data | |||

| Supratentorial (n = 710) | Cerebral Hemispheres | 132 (16.5) 85 (10.7) 59 (7.4) 43 (5.4) 102 (12.8) 99 (12.4) 62 (7.8) 17 (2.1) 4 (0.5) 33 (4.1) 20 (2.5) 5 (0.6) 1 (0.1) | 67 41 25 12 58 44 26 9 1 12 14 3 - | 52 32 26 22 32 44 27 6 2 18 4 2 1 | 13 12 8 9 12 11 9 2 1 3 2 - - |

| Parietal Frontal Occipital Temporal Frontoparietal * Parietooccipital * Parietotemporal * Frontotemporal * Temporooccipital * Frontotemporoparietal ** Temporoparietooccipital ** Frontoparietooccipital ** Frontotemporoparietooccipital ** | |||||

| Ventricular System | 24 (3.0) 6 (0.8) | 10 - | 9 - | 5 - | |

| Lateral ventricle Third ventricle | |||||

| Mentioned as supratentorial | 18 (2.2) | ||||

| Infratentorial (n = 88) | Mesencephalon Aqueduct of sylvius Pons Fourth ventricle Cerebellum Cerebellopontine angle | 2 (0.3) 4 (0.5) 6 (0.8) 6 (0.8) 25 (3.1) 9 (1.1) | - - - - 10 3 | - - - - 5 3 | - - - - 10 3 |

| Mentioned as infratentorial | 36 (4.6) | ||||

| Number of Cases (%) | Duration of Medical Treatment in Months Median (IQR)/n | |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment Methods (n = 665) | ||

| Surgery only Surgery and medical treatment Medical treatment only | 309 (46.5) 328 (49.3) 28 (4.2) | |

| Preoperative Medical Treatment (n = 106) | 3 (3-3)/71 | |

| Albendazole monotherapy Mebendazole monotherapy Albendazole + Praziquantel | 99 (93.4) 4 (3.8) 3 (2.8) | 3 (3-3)/69 3 (3-3)/1 12 (12-12)/1 |

| Postoperative Medical Treatment (n = 297) | 3 (2-6)/201 | |

| Albendazole monotherapy Mebendazole monotherapy Albendazole + Praziquantel | 273 (91.9) 14 (4.7) 10 (3.4) | 3 (2-6)/186 12 (1-12)/7 2 (1-5.25)/8 |

| Medical Treatment Only (n = 28) | 5 (3-6)/11 | |

| Albendazole monotherapy Mebendazole monotherapy Albendazole + Praziquantel | 23 (82.1) - 5 (17.9) | 5 (3-6.75)/10 - 6 (6-6)/1 |

| Number of Cases | Clinical Outcome | Follow-Up Duration in Months | Postoperative Recurrence | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete Recovery | Sequelae | Death | No Data | Median IQR | No Data | + | − | No Data | ||

| All Cases | 718 | 461 (85.5) | 31 (5.8) | 47 (8.7) | 179 | 12 (6–24) | 423 | 69 (26.0) | 196 (74.0) | 453 |

| Adults | 251 | 152 (88.4) | 5 (2.9) | 15 (8.7) | 79 | 12 (6–24) | 147 | 26 (38.8) | 41 (61.2) | 184 |

| Paediatric | 467 | 309 (84.2) | 26 (7.1) | 32 (8.7) | 100 | 12 (7–36) | 276 | 43 (21.7) | 155 (78.3) | 269 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Can, S.M.; Aldi, F.I.; Sarikaya, M.B.; Serin, P.S.; Sakru, N. Epidemiological, Diagnostic, and Clinical Features of Intracranial Cystic Echinococcosis: A Systematic Review. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1264. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121264

Can SM, Aldi FI, Sarikaya MB, Serin PS, Sakru N. Epidemiological, Diagnostic, and Clinical Features of Intracranial Cystic Echinococcosis: A Systematic Review. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1264. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121264

Chicago/Turabian StyleCan, Songul Meltem, Feza Irem Aldi, Muhammed Burak Sarikaya, Pelin Sari Serin, and Nermin Sakru. 2025. "Epidemiological, Diagnostic, and Clinical Features of Intracranial Cystic Echinococcosis: A Systematic Review" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1264. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121264

APA StyleCan, S. M., Aldi, F. I., Sarikaya, M. B., Serin, P. S., & Sakru, N. (2025). Epidemiological, Diagnostic, and Clinical Features of Intracranial Cystic Echinococcosis: A Systematic Review. Pathogens, 14(12), 1264. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121264