Abstract

Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and plasmid-mediated AmpC (pAmpC) β-lactamases represent a threat for public health. Their dissemination is often mediated by mobile genetic elements (MGEs), but plasmid identification and characterization could be hindered by sequencing limitations. Hybrid assembly may overcome these barriers. Eight ESBL/pAmpC-producing E. coli isolates from broilers were sequenced using Illumina (short-read) and Oxford Nanopore MinION (long-read). Assemblies were generated individually and using a hybrid approach. Plasmids were typed, annotated, and screened for antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs), MGEs, and virulence factors. Short-read assemblies were highly fragmented, while long reads improved contiguity but showed typing errors. Hybrid assemblies produced the most accurate and complete plasmids, including more circularized plasmids. Long and hybrid assemblies detected IS26 associated with ESBL genes and additional virulence genes not identified by short reads. ARG profiles were consistent across methods, but structural resolution and contextualization of resistance loci were superior in hybrid assembly. Hybrid assembly integrates the strengths of short- and long-read sequencing, enabling accurate plasmid reconstruction and improved detection of resistance-associated MGEs. This approach may enhance genomic surveillance of ESBL/pAmpC plasmids and support strategies to mitigate antimicrobial resistance.

1. Introduction

Bacterial resistance to antimicrobial agents is a major threat to public health [1]. Cephalosporins, a class of β-lactam antibiotics, are widely used in both human and veterinary medicine. Third-generation cephalosporins (3GCs) have particular therapeutic value in human medicine and represent one of the limited treatment options for infections caused by multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae [2]. Resistance to these agents is frequently mediated by extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and AmpC β-lactamases (AmpCs). The genes encoding these enzymes are often located on plasmids and associated with mobile genetic elements (MGEs), such as transposons (Tns) and insertion sequences (ISs) [3,4]. Consequently, horizontal gene transfer (HGT) via mobilization or conjugation plays a major role in the dissemination of β-lactam resistance across different strains and genera of the Enterobacteriaceae family [5]. Among them, Escherichia coli is a key player in the spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), as it readily acquires and transfers AMR genes (ARGs) to other bacterial species [6]. Thus, genetic characterization of plasmids and their associated MGEs in E. coli is essential for understanding the molecular mechanisms driving AMR dissemination [6].

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) provides a powerful tool for analyzing bacterial genomes and investigating ARGs [7]. Illumina short-read sequencing remains the most widely used technology in microbial genomics due to its high accuracy and throughput [8]. However, reconstructing plasmids from short reads alone is challenging, as repetitive regions often exceed the read length and typical paired-end insert sizes (~300–500 bp), which prevents complete plasmid assembly and hinders accurate contextualization of ARGs [9,10]. In contrast, long-read sequencing platforms such as Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) MinION generate reads of 8–10 kb or longer, which can span repetitive regions and improve plasmid reconstruction. Despite their higher error rates (5–15%), ongoing technological advances are steadily reducing these limitations. Hybrid assembly, which combines the structural resolving power of long reads with the base-level accuracy of short reads, has emerged as a promising approach for generating accurate and contiguous plasmid assemblies [10].

This study aimed to assess whether hybrid assembly enhances the characterization of ESBL/pAmpC-carrying plasmids in E. coli isolated from the broiler production pyramid compared to short- or long-read sequencing alone. In particular, we evaluated the ability of each approach to resolve plasmid structures, identify co-localized ARGs, characterize MGEs, and detect virulence genes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Isolates

The eight ESBL/pAmpC-producing E. coli strains included in this study (Table 1) were isolated from three production chains (A, B, and C) of an integrated broiler company in Northern Italy [11]. Screening for ESBL/pAmpC was performed on Eosin Methylene Blue agar (Microbiol, Cagliari, Italy) supplemented with 1 mg/L cefotaxime (CTX-EMB) and incubated at 37 ± 0.5 °C for 20 ± 2 h. ESBL/pAmpC production was confirmed by the double-disk synergy test according to CLSI guidelines [12]. Isolates characterization (i.e., phylogroups and sequence typing) and detection of ESBL/pAmpC resistance genes were performed by multiplex PCR [11]. A subset of isolates, selected on the basis of production chain, production stage, ESBL/pAmpC gene, and phylogroup combinations, was sequenced using Illumina short-read [13].

Table 1.

Phenotypic and genotypic features of the eight ESBL/pAmpC-producing E. coli included in the study.

2.2. Library Preparation and Whole-Genome Sequencing

In a previous study [13], bacterial DNA was extracted using the Invisorb Spin Tissue Mini Kit (Invitek, Berlin, Germany), libraries were prepared using the Nextera XT library preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), and sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeqX platform with 2 × 150 bp paired-end reads (Macrogen, Seoul, Republic of Korea). In the present study, bacterial DNA was extracted with the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, Hamburg, Germany) and long-read sequencing was performed on an ONT MinION platform using the Rapid sequencing gDNA barcoding kit (SQK-RBK110.96) (ONT, Oxford, UK) and R9.4.1 flow cells (ONT, Oxford, UK).

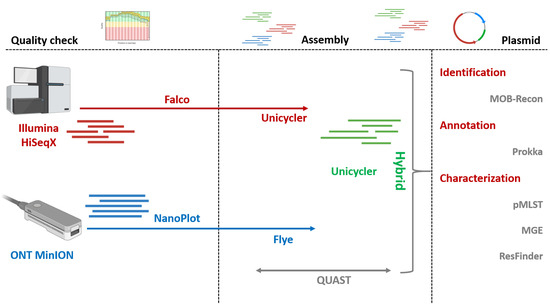

2.3. Raw Reads Quality Control

Illumina read quality was assessed using Falco (v1.2.4) [14]. Adapters and low-quality reads (Phred < 25) were removed using Trimmomatic (v0.39) [15] with default parameters. MinION reads were evaluated with NanoPlot (v1.44.1) [16] and filtered (Q > 8) with Nanofilt (v2.3.0) [17]. A graphical representation of the entire workflow is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the bioinformatics workflow applied for sequencing data processing, genome assembly, plasmid reconstruction, and downstream analyses.

2.4. Bacterial and Plasmid Whole-Genome Assembly

Short-reads assemblies were generated using Unicycler (v0.5.1) [18], meanwhile MinION long-read sequences were assembled using Flye (v2.9.6) [19]. Hybrid assemblies integrating both short- and long-read data were obtained using Unicycler (v0.5.1). General assembly statistics and quality metrics of the assembled genomes were calculated using QUAST (v5.3.0) [20].

2.5. Identification, Annotation, and Characterization of ESBL/pAmpC-Carrying Plasmids

MOB-Recon (v3.1.9) [21] was used to reconstruct and type individual plasmid sequences from short-, long-read, and hybrid assemblies. Plasmids harboring ESBL/pAmpC genes were characterized using pMLST 2.0 (v0.1.0) with default parameters [22] and annotated with Prokka (v1.14.6) [23]. ISs and Tns were identified using MGE (v1.14.6) with default parameters [24].

2.6. Resistance and Virulence Genes Detection

ARGs located on ESBL/pAmpC-carrying plasmids and other plasmids were identified using ResFinder (v4.7.2) with 90% identity threshold and 60% coverage [25]. Virulence genes were detected using MGE (v1.14.6) [24].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Differences in assembly performance (e.g., number of contigs, total length, N50, number of genetic features extracted) across short-read, long-read, and hybrid assemblies were assessed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test using GraphPad Prism (v10.5.0). Significant differences were set at a p-values < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Basic Statistics of Short and Long Reads

Statistics for both Illumina and MinION reads after trimming and quality filtering are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

An overview of basic sequence information statistics and quality. Genome coverage of ESBL/pAmpC-producing E. coli isolates was calculated by dividing the number of base pair (bp) obtained for each strain over the number of bp in the reference E. coli genome (NC_008563.1).

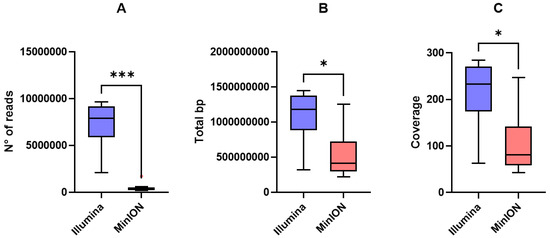

EC-33 and EC-91 showed higher long-read coverage compared to the other genomes. Meanwhile, short-read coverage was comparable among strains. Illumina reads yielded significantly higher number of reads (p = 0.0002), total base pair (bp) (p = 0.01), and coverage (p = 0.01) compared to long-reads (Figure 2A–C).

Figure 2.

Tukey box plots of (A) number of reads, (B) total bp, and (C) genome coverage yielded by Illumina short-reads (blue) and MinION long-reads (red). Differences were assessed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. p < 0.05 is shown as * and p < 0.001 as ***.

3.2. Performances of Short, Long, and Hybrid Assemblies

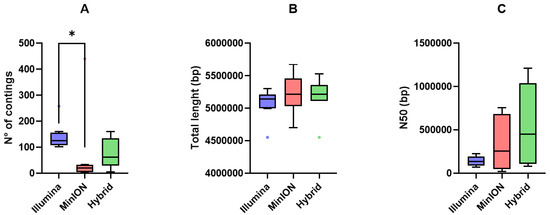

An overview of the comparison of the genome assembly performances of short-, long-read, and hybrid assemblies is reported in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Tukey box plots of (A) number of contigs, (B) total length (bp), and (C) N50 (bp) yielded by Illumina short-reads (blue), MinION long-reads (red), and hybrid assemblies (green). Differences were assessed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. p < 0.05 is shown as *.

Illumina short-reads produced more fragmented assemblies (higher number of contigs) compared to MinION long-reads and hybrid assemblies (p < 0.05; Figure 3A). Total assembly length (bp) was comparable among the three approaches (Figure 3B), whereas N50 values were higher for long-read and hybrid assemblies than for short-read assemblies (Figure 3C).

3.3. Identification, Annotation and Characterization of ESBL/pAmpC-Carrying Plasmids in Short, Long, and Hybrid Assemblies

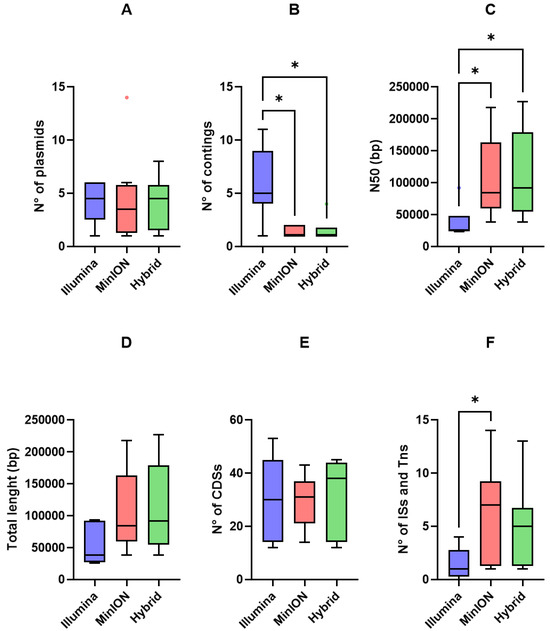

MOB-Recon detected a similar number of plasmids across assemblies (Figure 4A) and correctly identified the plasmid carrying the ESBL/pAmpC genes for each strain across the three assembly approaches.

Figure 4.

Tukey box plots of (A) number of plasmids, (B) number of contigs, (C) N50 (bp), (D) total length (bp), (E) number CDSs, and (F) number of IS and Tn sequences yielded by Illumina short-reads (blue), MinION long-reads (red), and hybrid assemblies (green). Differences were assessed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. p < 0.05 is shown as *.

Some differences among the assemblies were observed. Illumina assemblies produced a higher number of contigs compared to MinION (p = 0.033) and hybrid (p = 0.016) assemblies (Figure 4B), indicating that Illumina reads generated more fragmented plasmid sequences. Accordingly, N50 values were significantly higher for MinION (p = 0.044) and hybrid (p = 0.048) assemblies than for Illumina assemblies (Figure 4C). Lower contig numbers and higher N50 values corresponded to larger average plasmid sizes, although the differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05; Figure 4D). While short- and long-read assemblies produced only one and two ESBL/pAmpC circular plasmids, respectively, four ESBL/pAmpC plasmids were fully circularized in hybrid assemblies (Table 3).

Table 3.

Plasmids typing according to Illumina, MinION, and hybrid assemblies.

Seven different Inc replicons were identified across the eight plasmids (Table 3). MinION and hybrid assemblies detected all replicons, whereas Illumina reads failed to identify the IncFII replicon in the plasmid from strain EC-94. pMLST analysis was performed for replicons IncA, IncI1, and IncHI2. MinION assemblies performed the least effectively, failing to assign a plasmid sequence type (pST) for EC-94 and producing mismatches or gaps for the other plasmids. pMLST profiles matched between Illumina and hybrid assemblies, except for the plasmid in EC-40; Illumina classified it as pST-26 (clonal complex CC2), whereas hybrid assemblies identified it as a new pST assigned to CC-26. In both cases, pMLST alleles were perfectly matched to known references. Across all assemblies, 1296 coding DNA sequences (CDSs), including putative and hypothetical proteins, were identified among the eight plasmids. Annotated CDSs from Illumina and hybrid assemblies showed strong overlap (Figure 5), while MinION assemblies produced divergent results.

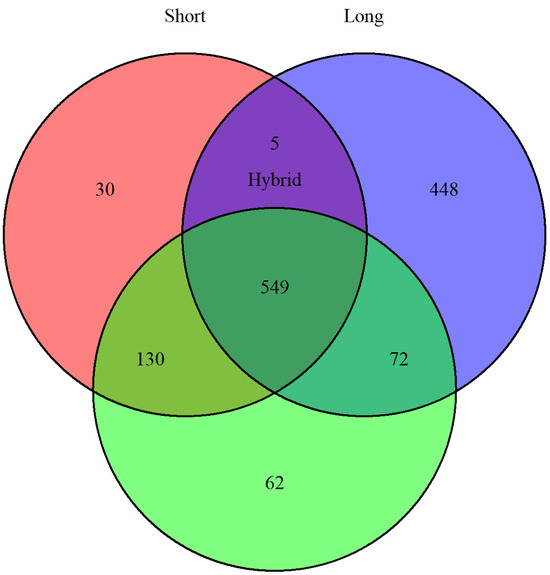

Figure 5.

Venn diagram prepared with VennDiagram in R (v4.5.1) plotting the differences and overlaps of annotated CDSs (including putative and hypothetical proteins) for short (red), long (blue), and hybrid (green) assemblies.

When putative and hypothetical proteins were excluded, short-, long-, and hybrid assemblies yielded a comparable number of CDSs (Figure 4E). Long assemblies showed higher performances in identifying IS and Tn sequences compared to Illumina reads (mean = 6.13 vs. mean = 1.5, and p = 0.042, Figure 4F). Furthermore, long-read and hybrid assemblies overperformed short-reads in characterizing the relationship between MGEs and ESBL/pAmpC genes. Indeed, while Illumina identified only three ISs (i.e., ISEc9 and IS26) and one Tn (Tn2) associated with ESBL/pAmpC genes, MinON and hybrid identified six ISs (i.e., ISEc9, IS26, and IS102), one Tn (Tn2), and one composite Tn (cn_5325_IS26) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Insertion sequences (ISs) and transposons (Tns) associated with ESBL/pAmpC genes and other ARGs identified in the eight ESBL/pAmpC plasmids using Illumina, MinION, and hybrid assemblies.

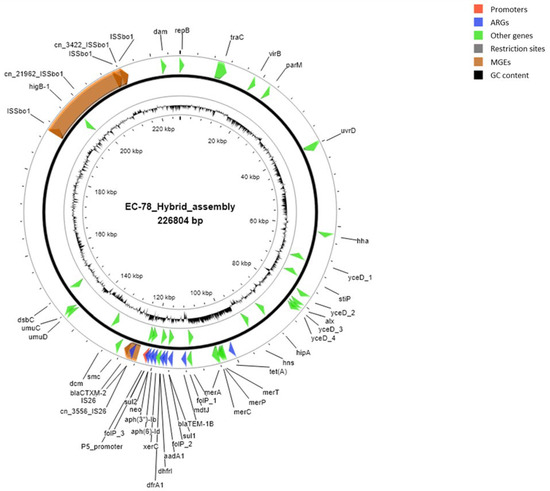

A map of the ESBL-carrying plasmid harbored by strain EC-78, based on sequences and annotations obtained using the hybrid assembly approach, is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Map of the ESBL-carrying plasmid harbored by strain EC-78, based on sequences and annotations obtained using the hybrid assembly approach. Mobile genetic elements (MGEs) are shown in orange, antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) in blue, other genes in green, and promoters in red. GC content and plasmid size are also indicated. Putative and hypothetical proteins are not reported.

3.4. Identification of Acquired Antimicrobial Resistance Genes and Virulence Factors in Short, Long and Hybrid Assemblies

Aside from genes against 3GCs, 25 different ARGs conferring resistance to eight antimicrobial classes (i.e., aminoglycosides, β-lactams, (fluoro)quinolones, macrolides, phenicol, sulphonamides, tetracyclines, and trimethoprim) were identified by the three assemblies across the eight ESBL/pAmpC carrying plasmids. According to all three assemblies, five out of eight plasmids showed a multi-resistant profile, carrying genes conferring resistance to three or more antimicrobial classes. Detail of ARGs identified by each assembly for each plasmid are reported in Table 4. Six known virulence genes (i.e., cib, terC, traJ, traT, astA, and anr) distributed among four ESBL/pAmpC plasmids were identified by long and hybrid assemblies, while short read detected only four.

3.5. Characterization of Other Plasmids in Short, Long and Hybrid Assemblies

Plasmids other than those carrying the ESBL/pAmpC genes were identified in all the strains but one (i.e., EC-91). The average plasmids size was comparable among the three assemblies (Figure S1A); however, hybrid assemblies yielded a higher number of circular plasmids compared to short- (p = 0.184) and long- (p = 0.129) read assemblies (Figure S1B). Nine different plasmid types (i.e., Col(MG828), ColpVC, ColRNAI, IncFIA, IncFIB, InCFIC, InchHI1B, IncHI2A, and IncI-gamma/K1) were identified across the short, long, and hybrid assemblies, with the latest showing the best typing performances (65.38%, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) 45.79–84.98% vs. 44.12%, 95% CI 26.53–61.70% and 55.56%, 95% CI 35.52–75.59%, respectively), even though the differences among assemblies were not significant (Figure S1C). In total 15 different ARGs belonging to seven different antimicrobial classes (i.e., aminoglycosides, β-lactams, macrolides, phenicol, sulphonamides, tetracyclines, and trimethoprim) were identified among the non-ESBL/pAmpC plasmids across the three assembly methods. Plasmids harbored by strains EC-56 and EC-94 showed multi-resistance profile. While long assembly identified a lower number of ARGs compared to the other two methods, no significant differences were observed (Figure S1D). Long and hybrid assemblies identified a higher number of ISs in non-ESBL/pAmpC plasmids (Figure S1E) compared to Illumina reads; indeed, while short-read assemblies detected 0.9 ISs per plasmid, this ratio increased to 1.48 and 1.85 for long and hybrid assemblies, respectively. Similarly, long and hybrid assemblies identified more virulence genes (n = 51 and n = 47, respectively) compared to short-read assembly (n = 40) (Figure S1F).

4. Discussion

The present study focused on the characterization of ESBL/pAmpC-carrying plasmids in E. coli strains isolated from the broiler production pyramid, using short-, long-, and hybrid-read assembly approaches. Our results, consistent with previous observations, demonstrate that the hybrid assembly strategy outperformed the exclusive use of either Illumina (short-read) or MinION (long-read) data in resolving plasmid structures and enabling detailed characterization [8,10,26]. Illumina assemblies produced a higher number of contigs and lower N50 values than MinION and hybrid assemblies, resulting in more fragmented and smaller plasmids. Consequently, short-reads yielded fewer circularized plasmids, both ESBL/pAmpC-carrying and non-ESBL/pAmpC, compared with the other two approaches, particularly the hybrid assembly approach. These findings reflect a known limitation of Illumina sequencing; short read lengths cannot span repeated elements commonly found in plasmids (e.g., ISs and Tns), making plasmid reconstruction more difficult and less accurate [27]. Long-read assemblies overcame this limitation but highlighted the lower sensitivity and higher error rate of nanopore sequencing. Specifically, long-read assemblies performed poorly in plasmid typing, producing mismatches and gaps against reference sequences and failing to type most plasmids, suggesting that nanopore data alone may not be optimal for plasmid typing or single-variant analysis [28]. However, in this study, long-reads assembly correctly classified two closely related genes of the blaCTX-M group (i.e., blaCTX-M-1 and blaCTX-M-15), which shared a nucleotide sequence similarity of about 98.7% [29]. In hybrid assemblies, Illumina data corrected MinION errors, while preserving the comprehensive detection of ISs and Tns. As a result, hybrid assemblies achieved typing accuracy comparable to Illumina while resolving plasmid structures more effectively and producing the highest number of circularized plasmids. This enhanced resolution enabled the characterization of gene clusters carrying resistance determinants and transfer systems, highlighting potential recombination mechanisms mediated by insertion sequences and other transposable elements [30]). Long-reads and hybrid assembly enabled to identify the association between three different ESBL genes (i.e., blaSHV-12, blaCTX-M-1, and blaCTX-M-2) and IS26, which would have been missed if using Illumina sequencing alone. Because IS26 plays a key role in the mobility of ESBL genes between plasmids and from plasmids to the chromosome [31], the absence of this information can hinder our understanding of ESBL gene transmission across humans, animals, and the environment. Indeed, a recent study combining the genetic analysis of more than 2500 plasmid sequences with in vitro inter-plasmid antibiotic resistance gene transfer experiments reported that IS26 is likely to accelerate ARG dissemination among different bacterial species [32]. Furthermore, IS26-mediated transposition activity of blaKPC-2 seems to play a key role in the emergence of carbapenem resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae [33]. Therefore, the identification and characterization if ISs, in particular IS26, are essential for implementing effective control measures and limiting the dissemination of critically important ARGs. Although dual sequencing increases costs, from an epidemiological and surveillance perspective, this added resolution justifies the use of hybrid assemblies.

The three approaches identified similar, if not identical, ARG profiles across the eight ESBL/pAmpC plasmids, indicating that hybrid assembly does not markedly improve resistance gene detection, in contrast to some previous observations [34].

VF gene prediction was comparable between long-read and hybrid assemblies, whereas Illumina identified fewer VF genes in both ESBL/pAmpC and non-ESBL/pAmpC plasmids. Previous studies have reported conflicting results when comparing short- and long-read sequencing for virulence gene detection [27,35]. Such discrepancies may be attributable to differences in library preparation, assembly, or bioinformatic tools and should be considered when comparing results across studies.

In conclusion, this study shows that hybrid assembly is a powerful approach in bacterial genomics. It provides a high-resolution view of plasmid architecture, improves the detection of resistance genes and their associated MGEs, and yields additional insights beyond those obtained from short- or long-read assemblies alone. Routine implementation of hybrid assemblies could generate essential knowledge to support targeted surveillance and intervention strategies against antimicrobial resistance.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the advantages of hybrid assembly in resolving the structure and genetic context of ESBL/pAmpC-carrying plasmids from E. coli in the broiler production chain. By integrating short- and long-read sequencing, hybrid assemblies overcome the limitations of individual platforms, enabling more accurate plasmid reconstruction and the detection of key mobile genetic elements, such as IS26, involved in resistance gene dissemination. Although resistance gene profiles were broadly similar across approaches, the enhanced structural resolution provided by hybrid assemblies offers valuable insights into plasmid dynamics. Routine application of this strategy can strengthen antimicrobial resistance surveillance and guide more effective interventions within a One Health framework.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pathogens14101039/s1), Figure S1. (A) Tukey box plots of total length of nonESBL/pAmpC plasmids. Bar plots of (B) circular and (C) typed nonESBL/pAmpC plasmids. Tukey box plots of number of (D) ARGs, (E) IS and Tn sequences, and (F) virulence genes identified in nonESBL/pAmpC plasmids by Illumina short-reads, MinION long-reads, and hybrid assemblies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L., I.A. and A.P.; formal analysis, A.L. and E.O.; investigation, R.T.; data curation, A.L. and I.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.L., E.O. and A.P.; writing—review and editing, A.L., E.O., R.T., I.A. and A.P.; visualization, A.L. and A.P.; supervision, A.P.; project administration, A.L. and A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Sequencing data were deposited in NCBI and are publicly available at PRJNA1328595.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jazmín Alejandra Ortega Ramírez for her support in data curation and analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3GCs | Third-generation cephalosporins |

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| AmpCs | AmpC β-lactamases |

| ARGs | Antimicrobial resistance genes |

| bp | Base pairs |

| CC | Clonal complex |

| CDS | Coding DNA sequence |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| CTX-EMB | Cefotaxime Eosin Methylene Blue |

| E. coli | Escherichia coli |

| EMB | Eosin Methylene Blue |

| ESBLs | Extended-spectrum β-lactamases |

| HGT | Horizontal gene transfer |

| IS | Insertion sequence |

| kb | Kilobase pairs |

| MGEs | Mobile genetic elements |

| N50 | Assembly contiguity statistic |

| NA | Not assigned/applicable |

| ONT | Oxford Nanopore Technologies |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| pMLST | Plasmid multilocus sequence typing |

| pST | Plasmid sequence type |

| Q | Quality score (Phred) |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| ST | Sequence type |

| Tn | Transposon |

| VF | Virulence factor |

| WGS | Whole-genome sequencing |

References

- Li, T.; Wang, Z.; Guo, J.; de la Fuente-Nunez, C.; Wang, J.; Han, B.; Tao, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, X. Bacterial Resistance to Antibacterial Agents: Mechanisms, Control Strategies, and Implications for Global Health. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 860, 160461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghnieh, R.; Estaitieh, N.; Mugharbil, A.; Jisr, T.; Abdallah, D.I.; Ziade, F.; Sinno, L.; Ibrahim, A. Third Generation Cephalosporin Resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Multidrug Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria Causing Bacteremia in Febrile Neutropenia Adult Cancer Patients in Lebanon, Broad Spectrum Antibiotics Use as a Major Risk Factor, and Correlation with Poor Prognosis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, R. Growing Group of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases: The CTX-M Enzymes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carattoli, A. Plasmids and the Spread of Resistance. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2013, 303, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebana, E.; Carattoli, A.; Coque, T.M.; Hasman, H.; Magiorakos, A.-P.; Mevius, D.; Peixe, L.; Poirel, L.; Schuepbach-Regula, G.; Torneke, K.; et al. Public Health Risks of Enterobacterial Isolates Producing Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases or AmpC β-Lactamases in Food and Food-Producing Animals: An EU Perspective of Epidemiology, Analytical Methods, Risk Factors, and Control Options. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 56, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trongjit, S.; Chuanchuen, R. Whole Genome Sequencing and Characteristics of Escherichia coli with Co-Existence of ESBL and mcr Genes from Pigs. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonvegna, M.; Tomassone, L.; Christensen, H.; Olsen, J.E. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) Analysis of Virulence and AMR Genes in Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL)-Producing Escherichia coli from Animal and Environmental Samples in Four Italian Swine Farms. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maio, N.; Shaw, L.P.; Hubbard, A.; George, S.; Sanderson, N.D.; Swann, J.; Wick, R.; AbuOun, M.; Stubberfield, E.; Hoosdally, S.J.; et al. Comparison of Long-Read Sequencing Technologies in the Hybrid Assembly of Complex Bacterial Genomes. Microb. Genom. 2019, 5, e000294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.; Pankhurst, L.; Hubbard, A.; Votintseva, A.; Stoesser, N.; Sheppard, A.E.; Mathers, A.; Norris, R.; Navickaite, I.; Eaton, C.; et al. Resolving Plasmid Structures in Enterobacteriaceae Using the MinION Nanopore Sequencer: Assessment of MinION and MinION/Illumina Hybrid Data Assembly Approaches. Microb. Genom. 2017, 3, e000118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, H.; McCarthy, M.C.; Nnajide, C.R.; Sparrow, J.; Rubin, J.E.; Dillon, J.-A.R.; White, A.P. Identification of Plasmids in Avian-Associated Escherichia coli Using Nanopore and Illumina Sequencing. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolakos, I.; Mughini-Gras, L.; Fasolato, L.; Piccirillo, A. Assessing the Occurrence and Transfer Dynamics of ESBL/pAmpC-Producing Escherichia coli Across the Broiler Production Pyramid. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 28th ed.; CLSI Supplement M100; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2018; ISBN 156238838X. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolakos, I.; Feudi, C.; Eichhorn, I.; Palmieri, N.; Fasolato, L.; Schwarz, S.; Piccirillo, A. High-Resolution Characterisation of ESBL/pAmpC-Producing Escherichia coli Isolated from the Broiler Production Pyramid. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandine, G.d.S.; Smith, A.D. Falco: High-Speed FastQC Emulation for Quality Control of Sequencing Data. F1000Research 2019, 8, 1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Coster, W.; Rademakers, R. NanoPack2: Population-Scale Evaluation of Long-Read Sequencing Data. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Coster, W.; D’Hert, S.; Schultz, D.T.; Cruts, M.; Van Broeckhoven, C. NanoPack: Visualizing and Processing Long-Read Sequencing Data. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 2666–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Gorrie, C.L.; Holt, K.E. Unicycler: Resolving Bacterial Genome Assemblies from Short and Long Sequencing Reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yuan, J.; Kolmogorov, M.; Shen, M.W.; Chaisson, M.; Pevzner, P.A. Assembly of Long Error-Prone Reads Using de Bruijn Graphs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E8396–E8405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikheenko, A.; Prjibelski, A.; Saveliev, V.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A. Versatile Genome Assembly Evaluation with QUAST-LG. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i142–i150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; Nash, J.H.E. MOB-Suite: Software Tools for Clustering, Reconstruction and Typing of Plasmids from Draft Assemblies. Microb. Genom. 2018, 4, e000206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carattoli, A.; Zankari, E.; García-Fernandez, A.; Larsen, M.V.; Lund, O.; Villa, L.; Møller Aarestrup, F.; Hasman, H. In Silico Detection and Typing of Plasmids using PlasmidFinder and Plasmid Multilocus Sequence Typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 3895–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, M.H.K.; Bortolaia, V.; Tansirichaiya, S.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Roberts, A.P.; Petersen, T.N. Detection of Mobile Genetic Elements Associated with Antibiotic Resistance in Salmonella enterica Using a Newly Developed Web Tool: MobileElementFinder. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 76, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortolaia, V.; Kaas, R.S.; Ruppe, E.; Roberts, M.C.; Schwarz, S.; Cattoir, V.; Philippon, A.; Allesoe, R.L.; Rebelo, A.R.; Florensa, A.F.; et al. ResFinder 4.0 for Predictions of Phenotypes from Genotypes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 3491–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydenham, T.V.; Overballe-Petersen, S.; Hasman, H.; Wexler, H.; Kemp, M.; Justesen, U.S. Complete Hybrid Genome Assembly of Clinical Multidrug-Resistant Bacteroides fragilis Isolates Enables Comprehensive Identification of Antimicrobial-Resistance Genes and Plasmids. Microb. Genom. 2019, 5, e000312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezri, A.; Avershina, E.; Ahmad, R. Hybrid Assembly Provides Improved Resolution of Plasmids, Antimicrobial Resistance Genes, and Virulence Factors in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Isolates. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxt, A.M.; Avershina, E.; Frye, S.A.; Naseer, U.; Ahmad, R. Rapid Identification of Pathogens, Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Plasmids in Blood Cultures by Nanopore Sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, O.; Chueiri, A.; O’Connor, L.; Lahiff, S.; Burke, L.; Morris, D.; Pfeifer, N.M.; Santamarina, B.G.; Berens, C.; Menge, C.; et al. Portable Differential Detection of CTX-M ESBL Gene Variants, blaCTX-M-1 and blaCTX-M-15, from Escherichia coli Isolates and Animal Fecal Samples Using Loop-Primer Endonuclease Cleavage Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e03316-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, C.; Hall, R. IS26-Mediate Formation of Transposons Carrying Antibiotic Resistance Genes. mSphere 2016, 1, e00038-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, L.; Cárdenas, P.; Graham, J.P.; Trueba, G. IS26 Drives the Dissemination of blaCTX-M Genes in an Ecuadorian Community. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e02504-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Yu, S.; Li, D.; Gillings, M.R.; Ren, H.; Mao, D.; Guo, J.; Luo, Y. Inter-Plasmid Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes Accelerates Antibiotic Resistance in Bacterial Pathogens. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrad032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Qin, X.; Yue, M.; Wu, L.; Li, N.; Su, J.; Jiang, M. IS26 Carrying blaKPC−2 Mediates Carbapenem Resistance Heterogeneity in Extensively Drug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolated from Clinical Sites. Mob. DNA 2025, 16, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boostrom, I.; Portal, E.A.R.; Spiller, O.B.; Walsh, T.R.; Sands, K. Comparing Long-Read Assemblers to Explore the Potential of a Sustainable Low-Cost, Low-Infrastructure Approach to Sequence Antimicrobial Resistant Bacteria with Oxford Nanopore Sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 796465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Escalona, N.; Kastanis, G.J.; Timme, R.; Roberson, D.; Balkey, M.; Tallent, S.M. Closed Genome Sequences of 28 Foodborne Pathogens from the CFSAN Verification Set, Determined by a Combination of Long and Short Reads. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2020, 9, e00152-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).