Abstract

This paper presents a physics-consistent hybrid surrogate framework for simulating the mechanical behavior of reinforced concrete beams that utilize waste fired clay (WFC) as a partial substitute for cement. The main contribution is the integration of empirically observed deformation behavior with physics-informed learning to produce an interpretable, mechanically valid surrogate model. Full-field surface deformation fields were measured using Digital Image Correlation (DIC) under monotonic loading and processed through a convolutional neural network (CNN) to extract deformation- and crack-sensitive features. These features were integrated with experimentally measured stress–strain data within a Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) in which equilibrium and conditional constitutive monotonicity constraints were enforced through the loss function. A Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) was utilized as a downstream parametric exploration tool to examine trade-offs among maximum load capacity, material cost, and embodied CO2 inside a constrained mixture-design space. Model interpretability was assessed by SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), indicating that deformation-driven kinematic factors predominantly influence stress prediction, whereas WFC content and reinforcement parameters have a secondary, mixture-level impact. The resulting framework achieves enhanced predictive accuracy (R2 = 0.969) relative to its individual components and operates as an offline, physics-calibrated surrogate rather than a real-time digital twin, providing a reliable and interpretable basis for structural assessment and sustainability-oriented design evaluation of WFC-modified reinforced concrete beams.

1. Introduction

Today, there is a growing concern about the environmental impact of cement, primarily due to the significant CO2 emissions generated during its production. Globally, the cement manufacturing sector is one of the largest industrial sources of greenhouse gas emissions, contributing an estimated 5–8% of global CO2 emissions [1,2,3,4,5]. The worldwide usage of cement has exceeded 4 billion tons [6]. One of the most efficient strategies to reduce the environmental impact of cement production is to use mineral additives as partial replacements for cement. In this way, both production costs and energy consumption are reduced. Furthermore, this contributes to waste reduction and sustainability. Among many industrial wastes, waste fired clay has recently gained considerable attention for its environmental benefits and functional capabilities. From an environmental perspective, using waste materials as partial substitutes for cement greatly lowers CO2 emissions linked to clinker manufacturing [7,8,9]. Waste fire clay (WFC) exhibits significant pozzolanic reactivity because of its high silica and alumina content, which allows it to react with calcium hydroxide released during cement hydration, forming extra calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) gel. This secondary hydration process improves the pore structure, decreases permeability, and boosts both strength development and long-term durability in cementitious composites—consistent with findings from studies on waste brick and fired-clay materials [10,11,12,13]. Economically, the widespread availability of WFC as an affordable industrial by-product aids in decreasing cement use and raw material requirements, which lowers production costs and enhances resource efficiency in the construction industry [14,15,16]. This strategy reduces dependence on energy-heavy clinker and boosts sustainability by using ceramic waste like clay brick and fire clay by-products. Collectively, these properties define WFC—a ceramic by-product similar to clay brick and refractory waste—as a practical and eco-friendly supplementary cementitious material for making sustainable mortar and concrete. Additionally, many studies show that clay brick and fire clay wastes can be effective substitutes not only for cement but also for natural aggregates in different concrete and mortar uses, promoting environmental sustainability and conserving resources in construction.

There are several studies on WFCs in the published literature. Özkılıç et al. [17] utilized waste fire clay to substitute up to 50% of the fine aggregate and cement in the concrete production process. To determine the compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strengths of the concrete, a series of mechanical tests was conducted. When WFC was used as a replacement for cement, a reduction in mechanical strength was observed, with compressive strength values decreasing by approximately 12.2% to 68%. Özkılıç et al. [18] further examined the post-fire behavior of WFC-modified concrete and reported that exposure to elevated temperatures (up to 900 °C) caused progressive reductions in compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strengths, confirming the detrimental effect of thermal exposure on mechanical performance. Ajayi et al. [19] examined the effect of the fineness of pulverized burnt clay waste on the compressive strength of concrete mixtures. For this purpose, pulverized burnt clay waste was employed at replacement levels of 0% (control), 10%, and 20% by weight of binder. The study found that the compressive strength of concrete is significantly affected by both the fineness and the ratio of pulverized burnt clay waste. Additionally, the results indicated that adding a slight excess of binder, about 5%, at certain replacement levels can improve the development of compressive strength. Elsheikh et al. [20] performed an experimental study to investigate the use of finely milled fired clay brick debris as a partial substitute for cement in mortar manufacture. Specifically, to accomplish this objective, two samples from different manufacturers were crushed into powder and added to the cement mortar mixes at 10%, 15%, and 20% by cement mass. These findings suggest that, in conjunction with curing time, adding fired clay brick improved mortar strength due to its pozzolanic properties. Schackow et al. [21] studied how replacing up to 40 wt.% of Portland cement with clean waste from fired clay bricks affects the properties of both fresh and hardened mortar. Because of the combined physical and pozzolanic pore-filling effect of the added fired clay brick, the mortars containing it exhibited enhanced strength and microstructural densification during curing. Őze et al. [22] showed that mechanochemical activation substantially improves the reactivity of waste clay brick powder by boosting its amorphous content and its specific surface area. The grinding process effectively induced amorphization of crystalline phases such as anorthite and diopside, leading to a marked increase in active silica content and pozzolanic reactivity. Overall, the study [22] confirmed that mechanochemical activation is an effective and sustainable method to improve the pozzolanic performance of waste clay brick powder, enabling its practical use as a supplementary cementitious material in sustainable cement-based systems.

There are also various studies on the workability and strength of brick waste dust when used as a substitute in concrete materials. Nasr et al. [23] comprehensively reviewed the use of clay brick waste powder as a partial replacement for cement in self-compacting concrete. The study found that clay brick waste powder, rich in silica and alumina, meets the chemical requirements of a Class N pozzolanic material, with acceptable workability and improved long-term strength when up to 10% replacement was used. Its inclusion enhances microstructural densification, shrinkage resistance, and durability through secondary C–S–H formation, though higher dosages may slightly reduce early-age strength. Furthermore, life cycle assessment revealed notable environmental advantages, with reductions in CO2 emissions and global warming potential of approximately 40%. This confirms the potential of clay brick waste powder as a sustainable supplementary cementitious material for producing eco-friendly self-compacting concrete. Sallı Bideci et al. [24] reviewed the potential of waste brick powder (WBP) as a supplementary cementitious material to lower the environmental effect of cement manufacturing. The study revealed that finely ground WBP (25–100 µm) with high silica and alumina oxides improves pozzolanic reactivity and helps maintain or boost compressive strength, pore refinement, and durability when used as a 10–20% cement replacement. At optimal levels, WBP reduces water absorption, shrinkage, and chloride permeability, but higher amounts can decrease early-age strength. Overall, WBP is considered a sustainable, eco-friendly cement alternative, significantly reducing CO2 emissions and resource use in mortar and concrete manufacturing. WFC was utilized by Özkılıç et al. [25] as a partial replacement for fine aggregate in certain quantities. This study aimed to evaluate how different percentages of WFC material affect the bending and shear performance of reinforced concrete beams. Specifically, WFC was added at 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% as a partial replacement for fine aggregate. At the end of the study, it was found that WFC contents in the range of 20% to 30% enhanced the bending performance of reinforced concrete beams, whereas the optimal waste fire clay content for shear behavior was identified as 20%. In this instance, it is important to note that the replacement involved fine aggregate rather than cement. Another study was performed by Sinkhonde et al. [26]. These researchers investigated the ductility behavior of rubberized concrete containing burnt clay brick powder. In their study, three beams were tested in flexure, while the other three were designed to fail in shear and flexure. Compared with control beams, the ductility of concrete beams incorporating 10% waste tire rubber and 5% burnt clay brick powder improved by 23.47% for beams that failed in flexure.

Additionally, studies on the application of waste brick materials to structural components, such as beams and columns, have been conducted. Yahia et al. [27] performed another investigation to examine the behavior of lightweight concrete produced using crushed over-burnt clay bricks. To manufacture structural lightweight concrete, crushed over-burnt clay bricks were employed as coarse aggregate, and a comparison was made with normal-weight concrete. This study included the construction of 15 reinforced concrete beams with a depth of 280 mm, a width of 120 mm, and a length of 2000 mm. At the end of the study, it was found that concrete made with crushed over-burnt clay brick aggregates exhibited lower density than concrete made with gravel aggregates. Moreover, the lower strength of the crushed, over-burnt clay brick aggregate led to increased deformation prior to failure, resulting in greater ultimate deflection of lightweight concrete beams than of normal-weight concrete beams. Miah et al. [28] investigated the potential of recycled crushed clay bricks (RCCB) as a replacement for natural sand in ferrocement mortars used for strengthening reinforced concrete beams. The study found that replacing up to 50% of sand with RCCB improved compressive, tensile, and flexural strengths while also reducing porosity due to finer particles filling microvoids. Ferrocement beams with 50% RCCB showed increased flexural strength and ductility, thanks to robust interfacial bonding provided by the rough brick surface. Overall, incorporating RCCB proved to be a sustainable and effective alternative to fine aggregate, improving structural performance and supporting waste recycling with Environmental benefits in construction. Thansirichaisree et al. [29] examined concrete made with recycled clay brick aggregates, including solid and hollow fired clay bricks, to evaluate their flexural performance when strengthened with low-cost glass fiber-reinforced polymer (LoC-GFRP). Although concrete with clay brick aggregates showed lower strength than natural aggregate concrete, confinement with LoC-GFRP layers increased flexural strength by up to 326% with three layers. The study demonstrated that recycled clay brick aggregate concrete, when properly confined, can achieve substantial flexural performance enhancement and provides a promising route for reusing fired clay waste in concrete construction and potential strengthening or repair applications. Islam et al. [30] studied concrete columns made with recycled burnt clay brick aggregates and strengthened with carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP). The recycled clay brick aggregates, obtained from demolished fired clay masonry, had low strength and high porosity, leading to weaker unconfined columns. However, CFRP confinement significantly improved performance, increasing axial strength by up to 72% and ductility by 23%. The study demonstrated that fired clay brick waste can be effectively reused in structural concrete when combined with CFRP strengthening, promoting sustainability and extended service-life performance. Jia et al. [31] studied the seismic performance of concrete columns and beams made with recycled clay brick aggregates. The results showed that although recycled brick aggregates are generally lightweight, concrete containing them exhibits lower strength, ductility, and energy dissipation capacity than natural aggregate concrete. Columns incorporating recycled brick aggregates showed poorer performance under horizontal cyclic loading, whereas beams exhibited relatively more stable seismic behavior. The study indicated that recycled clay brick aggregates can be used in concrete members, provided that their reduced seismic performance is carefully considered, supporting the sustainable reuse of fired clay waste in construction.

AbdElMoaty et al. [32] investigated the use of recycled crushed clay brick aggregates as replacements for natural coarse and fine aggregates in concrete. The study showed that replacing natural aggregates with crushed clay brick aggregates generally reduced mechanical strength, with larger reductions at higher replacement levels, which was attributed to the porous structure of the recycled material. The fine fraction (CCFA) reduced sorptivity, likely due to improved packing and a denser matrix, whereas the coarse fraction (CCCA) increased water absorption. Overall, the results indicated that some mixtures can fall within the semi-lightweight density range and show potential for structural applications requiring reduced self-weight. Zhu and Zhu [33] reviewed the reuse of waste clay bricks as partial substitutes for cement and aggregates in mortar and concrete. The review confirmed that clay brick powder exhibits pozzolanic activity, contributing to microstructural densification and improved durability when used as a partial cement replacement, with optimal replacement levels often reported in the range of 15–20%. Using clay brick waste as recycled brick aggregates (RBAs) lowers concrete density and provides satisfactory mechanical performance for medium- and low-strength uses, while also enhancing sulfate resistance and fire performance. Overall, the authors found that reusing clay brick waste offers a sustainable and eco-friendly solution, reducing cement use, landfill waste, and CO2 emissions. Wu et al. [34] examined the usage of clay brick waste, focusing on recycled brick powder (RBP) and RBA, for the production of sustainable cementitious materials. The recycled brick powder, which is rich in silica and alumina, showed pozzolanic activity. This helped improve the pore structure and reduced permeability and chloride penetration. In contrast, using recycled brick aggregates led to higher water absorption and drying shrinkage because of their increased porosity. The authors noted that a mix of 50% RBA and 30% RBP provided a balanced performance, maintaining mechanical strength while enhancing durability and sustainability by efficiently reusing fired clay brick waste. Joyklad [35] performed an extensive literature review of global research on RBA concrete and reported that existing studies consistently show lower mechanical strength and higher porosity compared with natural aggregate concrete. RBA concrete offers advantages such as lower density and fire resistance. However, its use has largely been limited to non-structural applications. The review highlighted a notable lack of research on the structural performance of RBA concrete, particularly in reinforced concrete members subjected to critical loading conditions, underscoring the need for further experimental investigations to enable broader, more sustainable structural applications of clay brick aggregates in concrete. Despite extensive experimental investigations, the resulting datasets remain fragmented, high-dimensional, and challenging to generalize. This highlights the need for robust surrogate modeling frameworks that can accurately capture complex structural behavior. Addressing these identified limitations, especially the limited experimental data on structural performance and the complex nature of material behavior, has led to increased use of advanced data-driven and predictive modeling methods in concrete research. Consequently, neural-network-based modeling approaches—particularly deep learning and physics-informed frameworks—have been increasingly explored in the literature to address complex, nonlinear behaviors in cementitious and structural systems [36].

This study aims to develop a physics-consistent surrogate modeling framework that combines experimental full-field deformation measurements, physics-informed learning, and multi-objective optimization to characterize the mechanical behavior of reinforced concrete beams containing WFC. In addition to the aforementioned investigations, although prior studies such as [17,25,37,38] have examined the structural performance of WFC-modified concrete through experimental testing, there is a lack of methodologies that integrate deformation-resolved data with physics-informed machine learning models while maintaining constitutive admissibility. Notwithstanding extensive research on sustainable cement-replacement materials, digital image correlation-based deformation analysis, physics-informed neural networks, and multi-objective optimization, these methodologies have predominantly been developed and used independently. Prior research [39,40,41,42] has either focused on material-level performance without using full-field deformation data or relied on data-driven models without imposing mechanical admissibility via physics-based constraints; notably, such full-field deformation measurements naturally lend themselves to convolutional neural network (CNN)-based feature extraction. Similarly, optimization frameworks have often been decoupled from empirically validated surrogate models, reducing their interpretability and physical significance.

This paper presents a unified hybrid surrogate modeling method that explicitly integrates DIC-derived kinematic descriptors, physics-informed constitutive learning, and design-space exploration into a comprehensive offline approach. The proposed approach incorporates deformation-sensitive features into a physics-based, constrained learning framework. It links the calibrated surrogate model to multi-objective optimization, effectively integrating experimental observations, mechanical integrity, and sustainability-oriented design. This integration facilitates the physically interpretable prediction of structural responses while simultaneously assessing the structural and environmental impacts associated with the utilization of waste fired clay. Consequently, it advances existing methodologies beyond simple enumeration of discrete procedures.

2. Components and Methodology

2.1. Experimental Studies

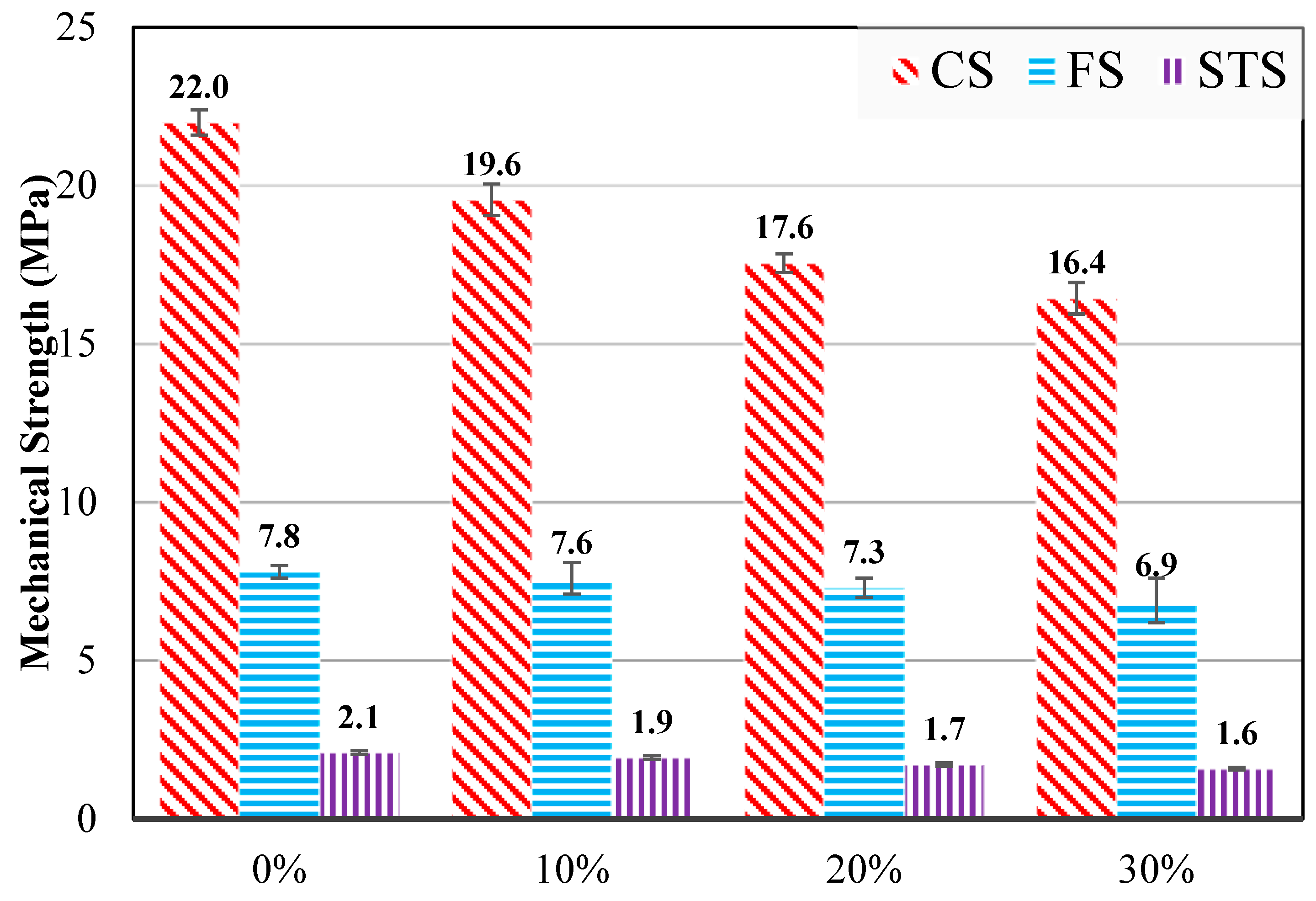

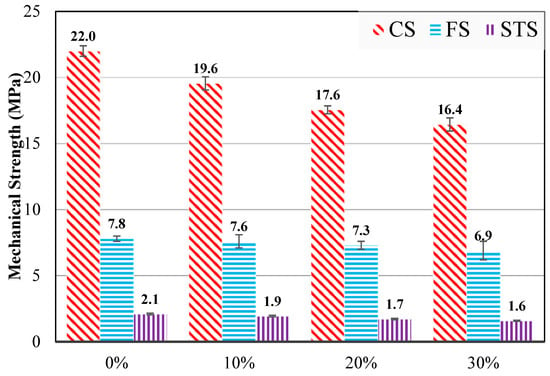

The experimental program consisted of the reinforced concrete (RC) beam specimens. CEM I 32.5 cement was used in the production of all specimens. In both specimen types, cement was partially replaced with WFC at replacement levels of 10%, 20%, and 30%. The results of the concrete tests, including workability and compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strengths, have been previously reported by Özkılıç et al. [17] and are briefly summarized herein for completeness. As shown in Figure 1 [17], the strength values decreased with increasing WFC content when used as a cement replacement.

Figure 1.

Strength test results [17].

In contrast, the experimental investigation of RC beam specimens incorporating WFC is presented for the first time in this study, with a focus on their structural behavior and performance.

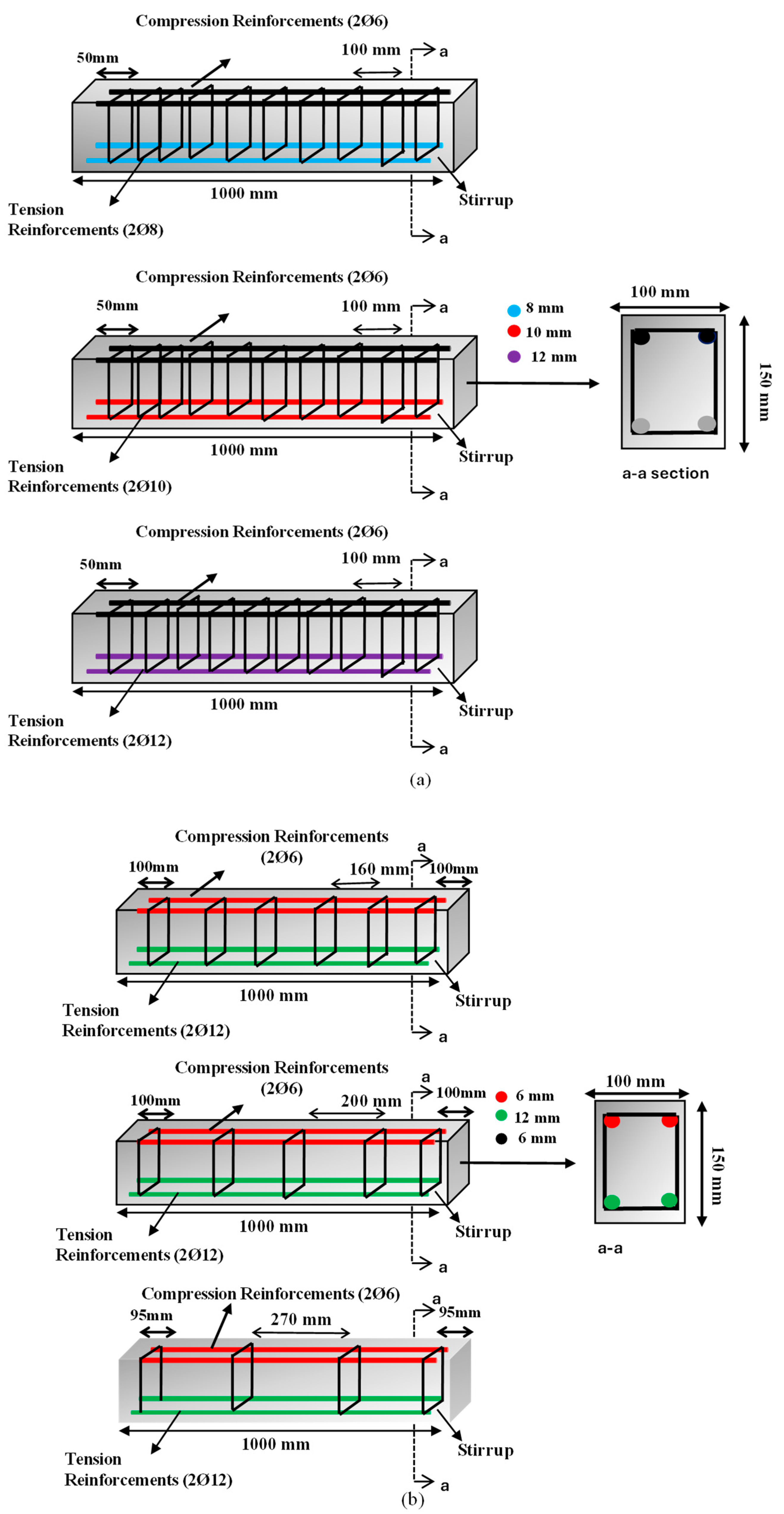

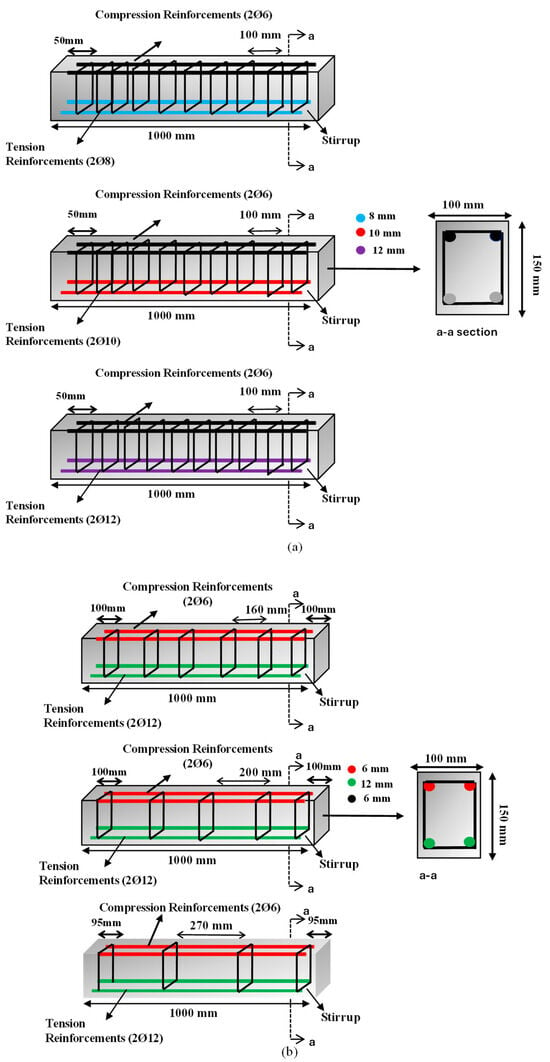

The reinforced concrete beams were experimentally investigated in the Civil Engineering Laboratory of Necmettin Erbakan University, where the samples were also prepared and cast. A total of 24 beam specimens were tested. The reinforced concrete beams had dimensions of 100 × 150 × 1000 mm. Three distinct stirrup spacings of 160, 200, and 270 mm were taken into consideration to examine the shear behavior of the test materials. Furthermore, to investigate flexural behavior, all beams were reinforced with Ø6 longitudinal bars in the compression zone, while the tensile reinforcement varied by beam series as Ø8 (ρs = 0.0077), Ø10 (ρs = 0.0121), or Ø12 (ρs = 0.0174). For the flexural beam specimens, the stirrup spacing was kept constant at 100 mm to ensure flexure-dominated behavior. The shear and flexural beam characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The reinforcement layout is shown in Figure 2, and the experimental test setup is shown in Figure 3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of shear and bending beams.

Figure 2.

Reinforcement arrangement: (a) bending; (b) shear.

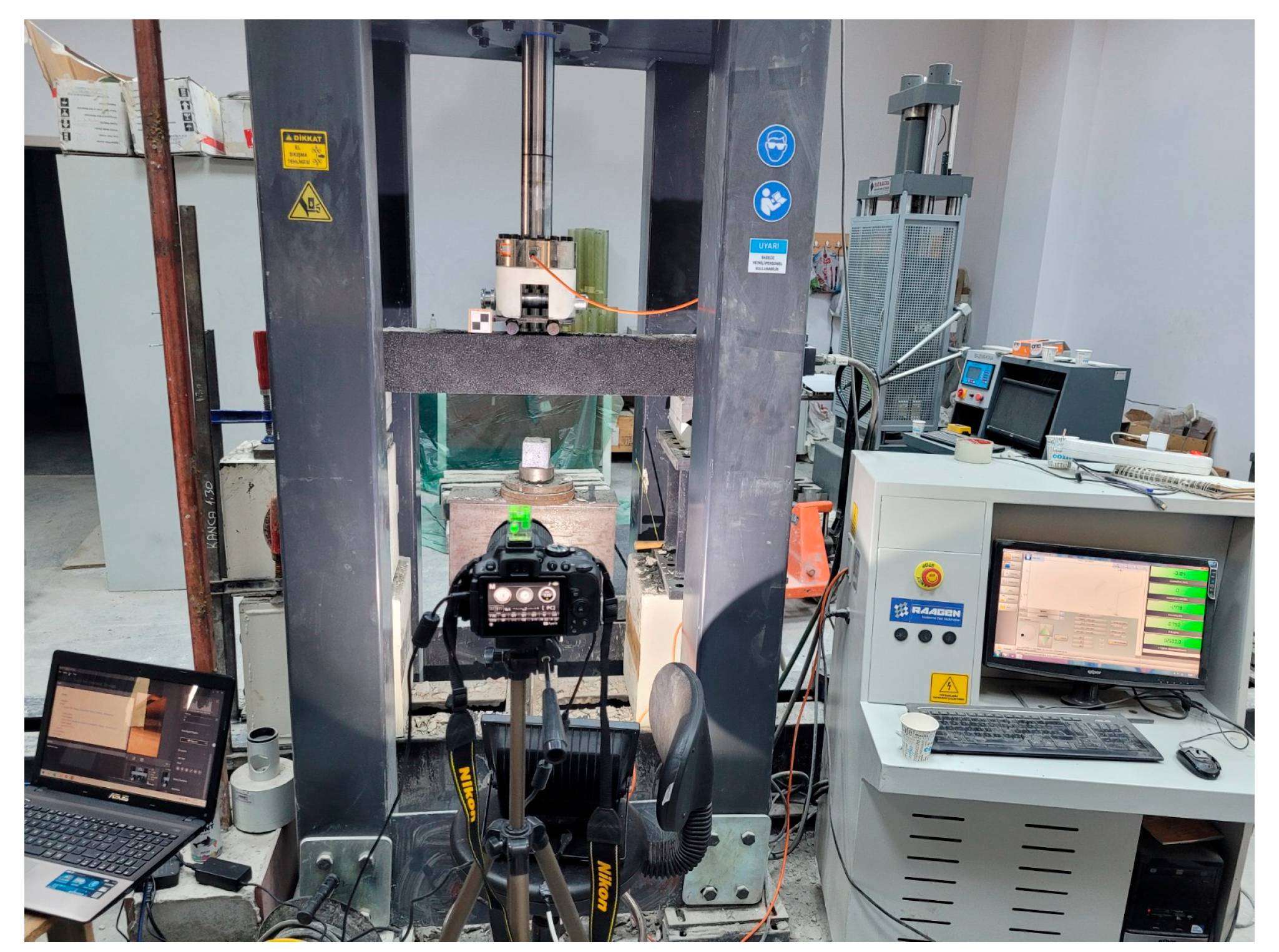

Figure 3.

Test setup.

2.2. Machine Learning-Based Modeling Framework

Comprehensive surface strain measurements (εx, εγ, εeq) were acquired utilizing a stereo Digital Image Correlation (DIC) system during incremental loading. Spatial strain maps were converted into representative statistical descriptors and picture patches for each load phase.

A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) was utilized solely as a feature extractor, converting DIC-derived strain pictures into latent descriptors that characterize fracture initiation, propagation, and strain localization patterns. The CNN was not employed to directly forecast mechanical response variables. The CNN encoder comprises a shallow convolutional architecture with successive convolution–activation–pooling blocks, trained with the Adam optimizer at a learning rate of order 10−3 and mini-batch training. The effective training dataset consists of localized DIC strain patches extracted from the 24 tested beams across incremental load stages.

A Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) was then trained to correlate longitudinal strain and mixture characteristics with stress response. The governing constraints embedded in the PINN include equilibrium consistency, conditional enforcement of positive tangent stiffness in the pre-peak regime, and constitutive smoothness. Boundary conditions are implicitly defined through experimentally measured load–displacement and stress–strain responses, which anchor the learning process to physically observed behavior. The PINN loss function had two elements:

where enforces agreement with experimental stress–strain measurements and penalizes violations of equilibrium, monotonicity, and constitutive smoothness. The physics-based loss term incorporates equilibrium consistency, conditional positive-tangent-stiffness enforcement in the pre-peak regime, and constitutive smoothness constraints. The monotonicity constraint is applied only up to the experimentally observed peak strain and is relaxed beyond peak stress to allow post-peak softening associated with damage evolution. The derivative-based monotonicity penalty is activated conditionally for strain levels below the experimentally identified peak strain and is deactivated in the post-peak regime to permit negative tangent stiffness associated with damage evolution. This formulation ensures that the learned response remains mechanically admissible and avoids purely empirical overfitting. It is emphasized that no closed-form equations were used as neural network architectures. All analytical expressions reported later in the manuscript were derived post-training as simplified regression approximations of trained model behavior for engineering interpretability only. In addition, WFC is highlighted as a pozzolanic powder utilized as a partial substitute for cement and does not function as an independent fiber or bridging reinforcement. The physics-based constraints in the PINN loss function are established as general constitutive admissibility criteria for cementitious composites (equilibrium consistency, pre-peak positive tangent stiffness, and smoothness of the σ–ε response), rather than as fiber-bridging mechanics.

A Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) was utilized as a potential parametric exploration instrument to examine trade-offs among maximum load-carrying capacity (Pmax), material cost, and embodied CO2. The NSGA-II optimization was performed using a fixed population size and generation count selected to ensure adequate coverage of the bounded design space. Sensitivity checks confirmed that the overall Pareto trends were not significantly affected by reasonable variations in initial population sampling or algorithmic parameters, indicating stable convergence behavior. The objective functions were formulated to optimize Pmax while minimizing costs and CO2 emissions. The obtained Pareto-optimal solutions enabled the formation of a Pareto frontier, and a continuous three-dimensional response surface (WFC–W/B–Pmax) was generated by interpolation to depict multi-objective trends. The Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) was utilized as a parametric exploration tool rather than an experimental regression model. The experimental program utilized a constant water–binder ratio (W/B = 0.46). However, a limited variation of W/B was incorporated only during the optimization phase to investigate potential trade-offs among strength, cost, and embodied CO2 for future mixture design scenarios. The distinction between the experimental and exploratory optimization domains is deliberately maintained to prevent methodological inconsistency. The findings of NSGA-II thus signify possible design trends rather than experimentally corroborated replies.

The experimental dataset consists of 24 reinforced concrete beams tested under controlled laboratory conditions. Although the sample size is limited from a strictly empirical standpoint, the suggested framework is deliberately designed as an offline, physics-calibrated surrogate rather than a data-intensive deep learning model. The learning process is thus directed by physical limitations and the consistency of deformation rather than statistical prevalence.

Digital Image Correlation (DIC) pictures obtained at consecutive load stages were analyzed using a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to capture damage features induced by deformation. The CNN was employed as a damage-sensitive feature extractor, transforming localized strain and crack-pattern information into latent descriptors reflecting microcrack initiation, crack propagation, and strain localization. The CNN results were not utilized as independent predictors of structural capacity; rather, they were integrated as supplementary inputs inside the hybrid surrogate framework. The extracted latent features encode spatial strain gradients, crack localization zones, deformation anisotropy, and damage progression patterns derived from full-field DIC measurements. The combined use of spatial feature extraction and physics-informed regularization provides inherent robustness against measurement noise commonly associated with DIC and load–strain data.

Before the PINN formulation, the experimental stress values utilized for model calibration were obtained directly from the load–displacement data. The load-cell measurements (P) were transformed into engineering stress directly from the applied load using the fixed beam cross-section of 100 × 150 mm2. In addition, strain was captured using a stereo DIC system, which computed full-field εx–εγ strain components from tracked surface displacements during loading.

Outputs of the CNN-based deformation descriptors, the PINN, and the NSGA-II parametric model were integrated into a validation-weighted hybrid ensemble surrogate. Each component influenced the final forecast based on its validation performance, as measured by R2 and RMSE. The hybrid surrogate response was articulated as

in which represent the weighting coefficients, and they were normalized.

To mitigate the overfitting hazards associated with the limited dataset size, the CNN is used solely as a deformation-sensitive feature extractor rather than a flexible predictor. The PINN imposes additional constraints on learning via equilibrium and monotonicity penalties integrated into its loss function, thereby diminishing reliance on data-driven fitting alone. The final training dataset consists of experimentally measured stress–strain pairs, mixture-design parameters, and CNN-derived deformation descriptors, which are jointly used to guide the physics-informed learning process. For each load step, the DIC-derived full-field strain was spatially averaged over the constant-moment region of the beam to obtain a representative longitudinal strain value, which was paired with the corresponding engineering stress and used as input for PINN training.

Model interpretability was examined using SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP). This analysis was used to identify the influence of key input variables, including WFC content, longitudinal reinforcement diameter (Φ), stirrup spacing (s), and the water–binder ratio (W/B), on the predicted load capacity. The global SHAP results indicate that WFC content and reinforcement ratio exert the strongest effects on Pmax, acting in opposite directions, which is consistent with basic principles of structural behavior. Model accuracy was evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE).

In this study, the term digital twin refers to an offline, physics-calibrated surrogate representation rather than a real-time cyber-physical system. All performance measures for the models presented in this paper, including the coefficient of determination (R2), are calculated only from the original experimental dataset of 24 beams. No fake or interpolated samples were used in the validation or testing phases to avert data leaks and artificially enhanced performance.

Cost denotes the material production cost normalized per cubic meter of concrete (€/m3), while CO2 represents embodied carbon emissions (kg CO2/m3) associated with raw material production and mixture composition. The hybrid framework is applied exclusively in a post-processing context and is not intended for real-time monitoring of experimental tests.

3. Evaluation Findings and Discussion

3.1. Influence of Different WFC Rates on Bending Behavior

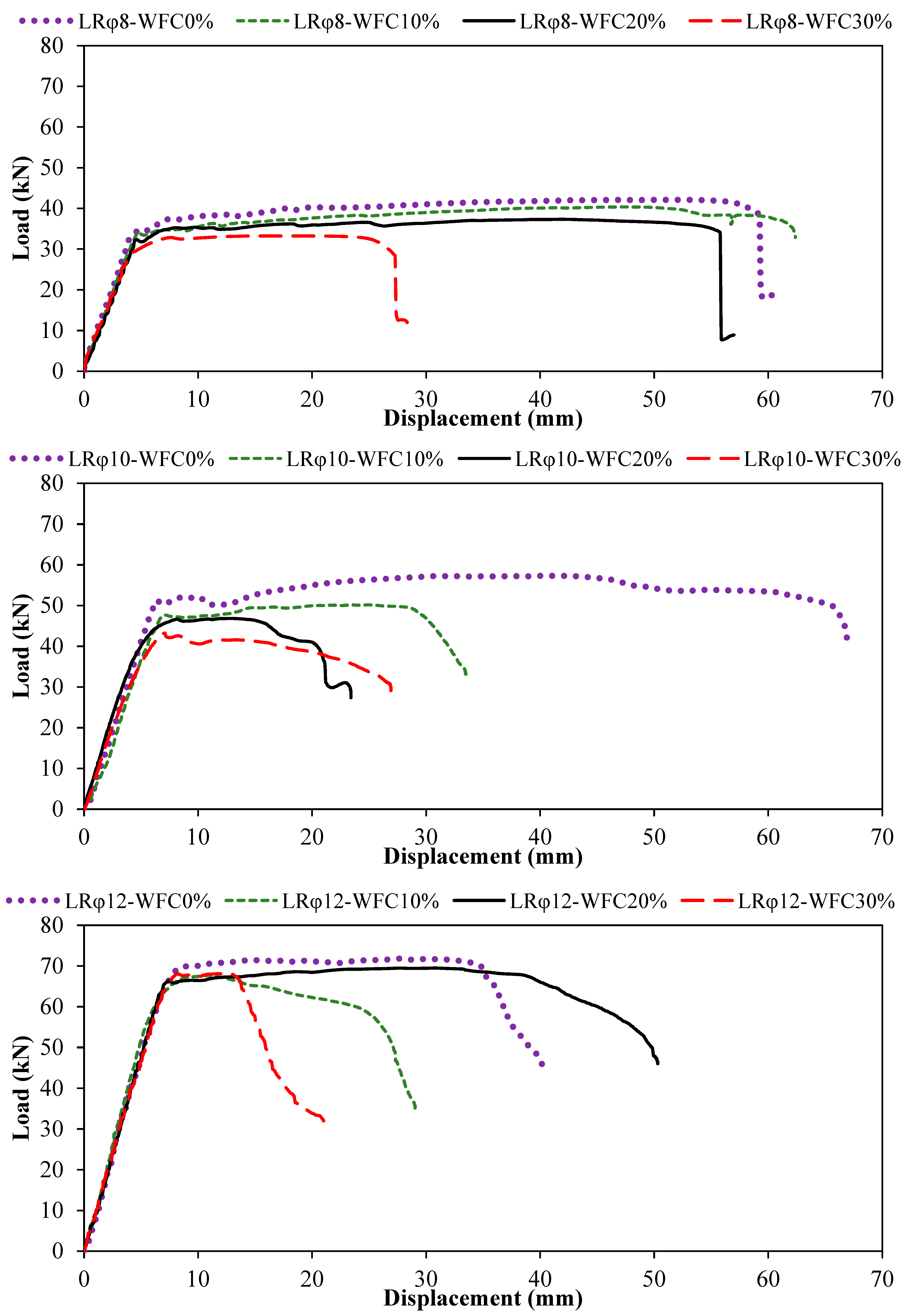

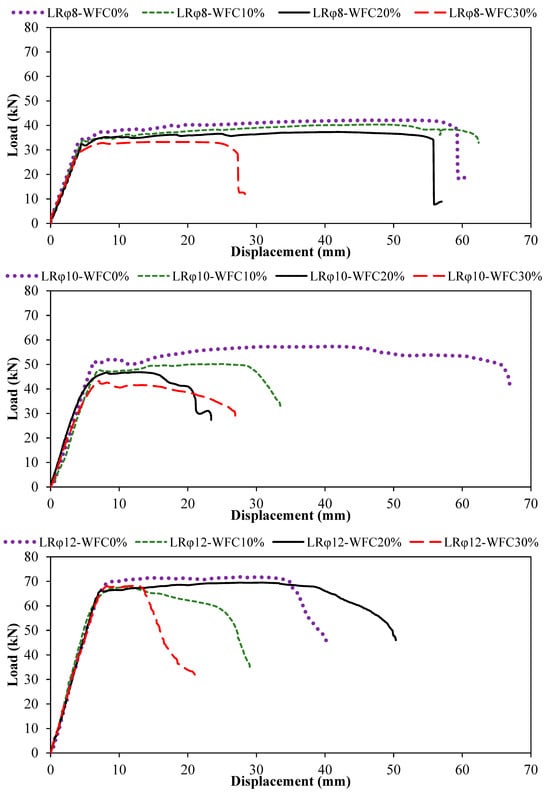

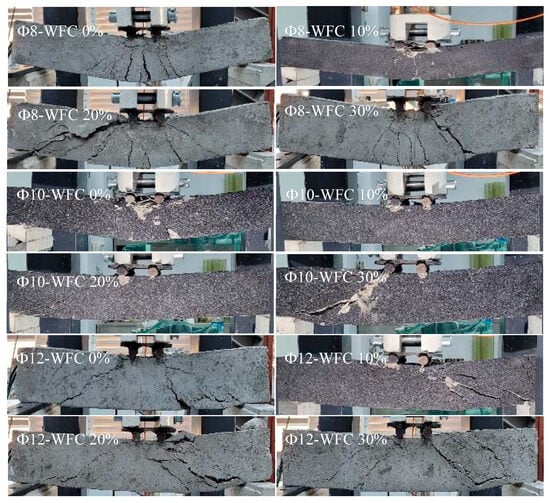

The influence of WFC content in the mixture on the bending behavior of reinforced concrete beams was investigated for four replacement levels: 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%. These levels were selected to evaluate the effect of WFC on flexural performance. For this purpose, Φ8, Φ10, and Φ12 longitudinal reinforcement bars were selected. The experimental results are shown in Figure 4. For the Φ8 beam with 0% WFC, the maximum load-bearing capacity and corresponding deformation were 42.12 kN and 50.26 mm, respectively. When the WFC content increased to 10%, the maximum load-bearing capacity decreased to 40.37 kN with a deformation of 47.82 mm. For WFC contents of 20% and 30%, the values obtained were 37.35 kN–42.06 mm and 33.26 kN–18.98 mm, respectively. In addition, as illustrated by the descending branches of the load–displacement curves in Figure 4, the beams exhibited large deformation capacities at reduced load levels (reduced load level refers to the load level corresponding to 0.85 Pmax, as defined in Table 2). The displacement values corresponding to these reduced load stages were recorded as 60.30 mm at 18.62 kN, 62.38 mm at 32.89 kN, 56.90 mm at 8.89 kN, and 28.33 mm at 11.98 kN for WFC contents of 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%, respectively, as reported in Table 2. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 4, compared with the reference beam (0% WFC), the maximum load-bearing capacity decreased by 4.15%, 11.32%, and 21.04% for WFC contents of 10%, 20%, and 30%, respectively.

Figure 4.

Graphs of load displacement for varying reinforcement diameters and WFC percentages.

Table 2.

Results from experiments and calculations regarding displacement and load values.

The maximum load-carrying capacity and corresponding deformation of the reinforced concrete beam were 57.33 kN and 41.46 mm, respectively, for the Φ10 beam with 0% WFC. When the WFC content increased to 10%, the maximum load-bearing capacity decreased to 50.19 kN with a corresponding deformation of 24.97 mm. For WFC contents of 20% and 30%, the values obtained were 46.85 kN–13.08 mm and 43.21 kN–7.09 mm, respectively. In addition, as illustrated by the descending branches of the load–displacement curves in Figure 4, the beams exhibited significant deformation capacities at reduced load levels. The displacement values corresponding to these reduced load stages were recorded as 66.89 mm at 41.91 kN, 33.49 mm at 32.88 kN, 23.40 mm at 27.40 kN, and 26.90 mm at 28.93 kN for WFC contents of 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%, respectively, as reported in Table 2. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 4, compared with the reference beam (0% WFC), the maximum load-carrying capacity decreased by 12.45%, 18.28%, and 24.63% for WFC contents of 10%, 20%, and 30%, respectively.

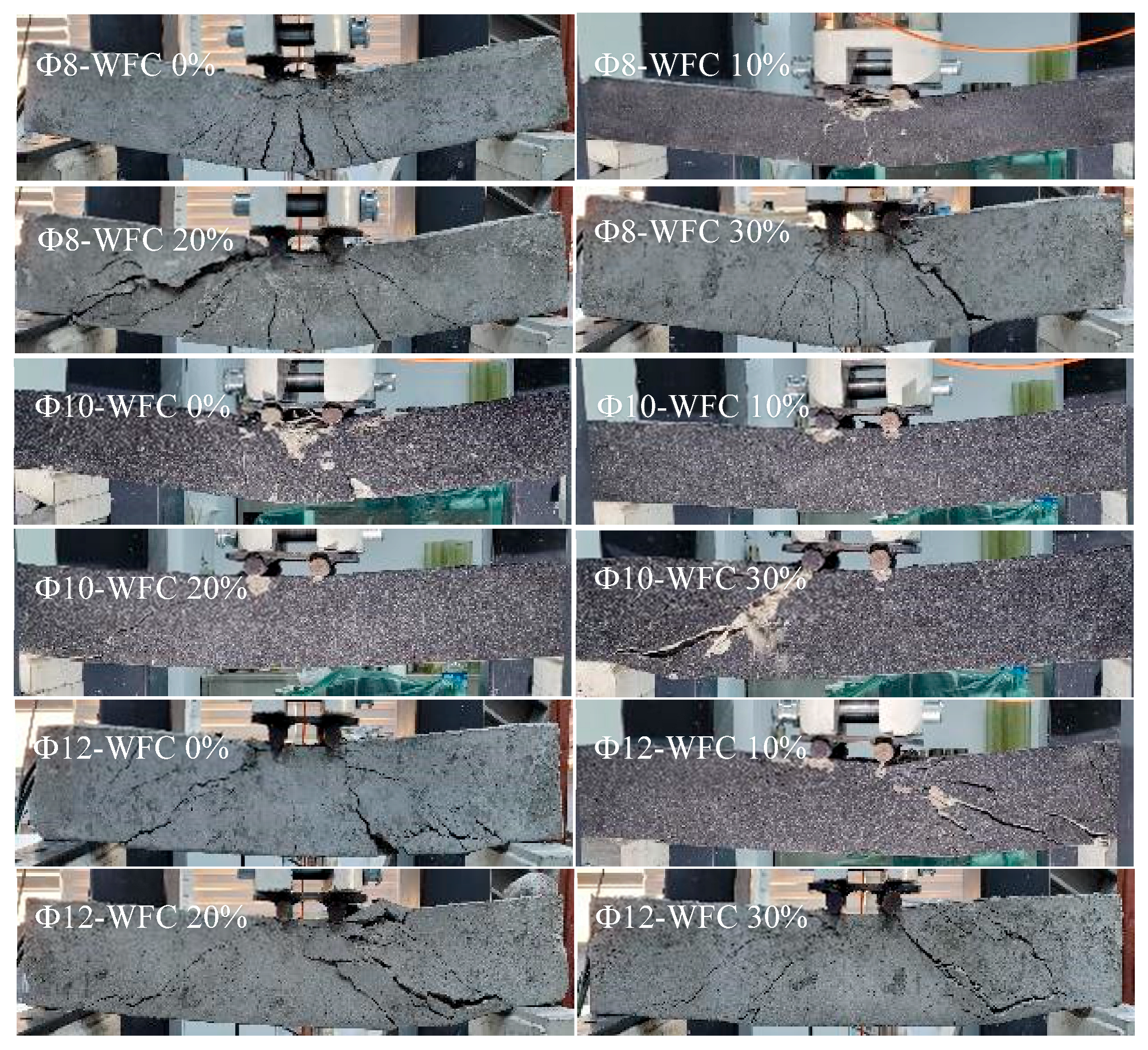

When the tests were carried out in the same manner for Φ12 and WFC ratios of 0%, the maximum load-bearing capacity of the reinforced concrete beam and the corresponding deformation were 71.82 kN and 27.53 mm, respectively. When the WFC ratio was increased to 10%, the maximum load-bearing capacity and deformation were 67.70 kN and 10.92 mm. The values obtained for WFC ratios of 20% and 30% were 69.51 kN–30.73 mm and 68.13 kN–11.70 mm, respectively. In addition, the displacement values corresponding to the reduced load stage (Table 2) were recorded as 40.19 mm at 44.80 kN, 29.07 mm at 34.84 kN, 50.31 mm at 46.07 kN, and 21.01 mm at 30.44 kN, respectively. As shown in Figure 4, compared with the reference beam (0% WFC), the maximum load-bearing capacity decreased by 5.74%, 3.22%, and 5.15% for WFC contents of 10%, 20%, and 30%, respectively. The results also indicate that increasing the reinforcement diameter enhances the maximum load-bearing capacity of the beams. The crack behavior of the beam under load is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Flexural crack patterns observed in beams under bending.

3.2. Influence of Different WFC Rates on Shear Behavior

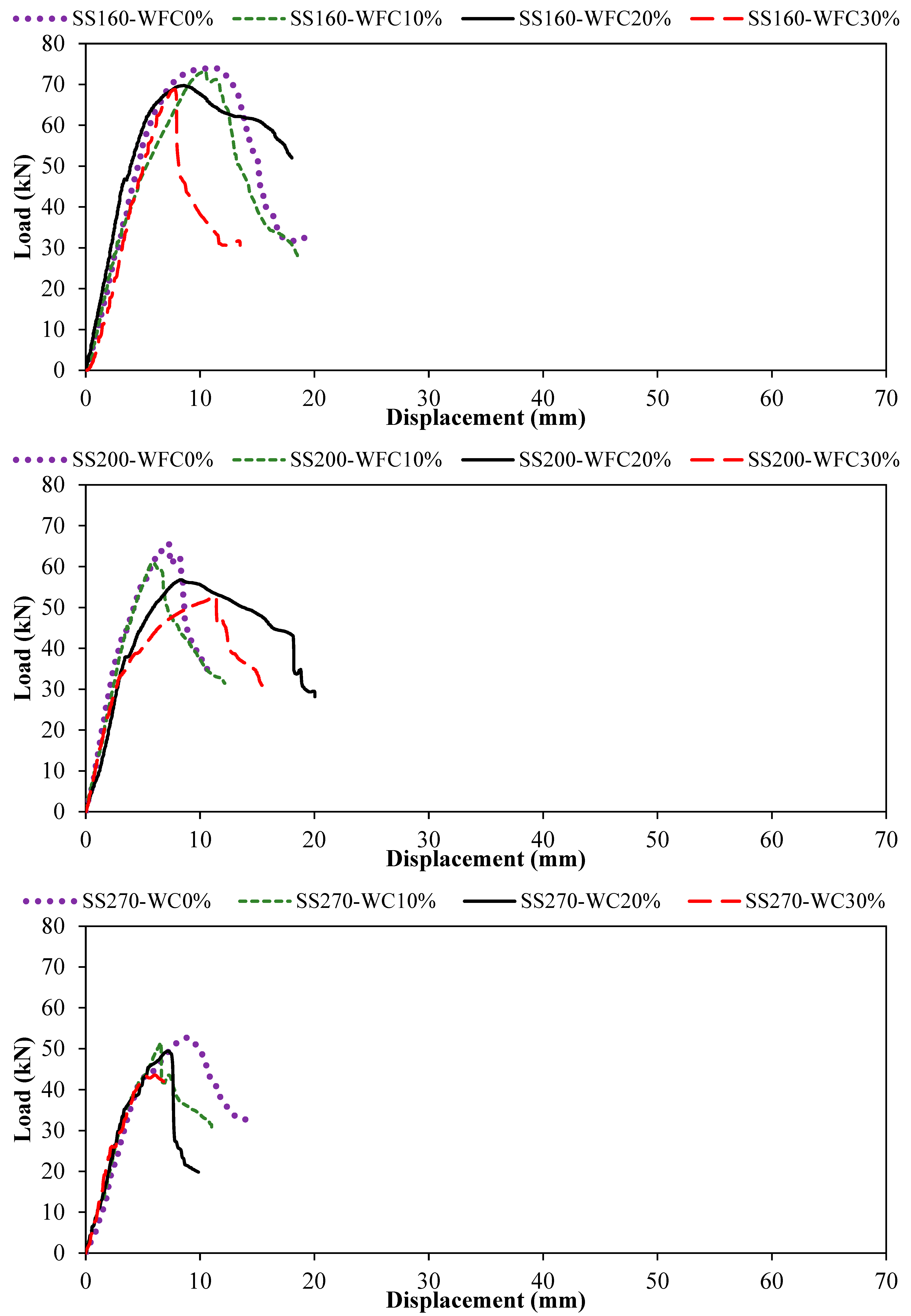

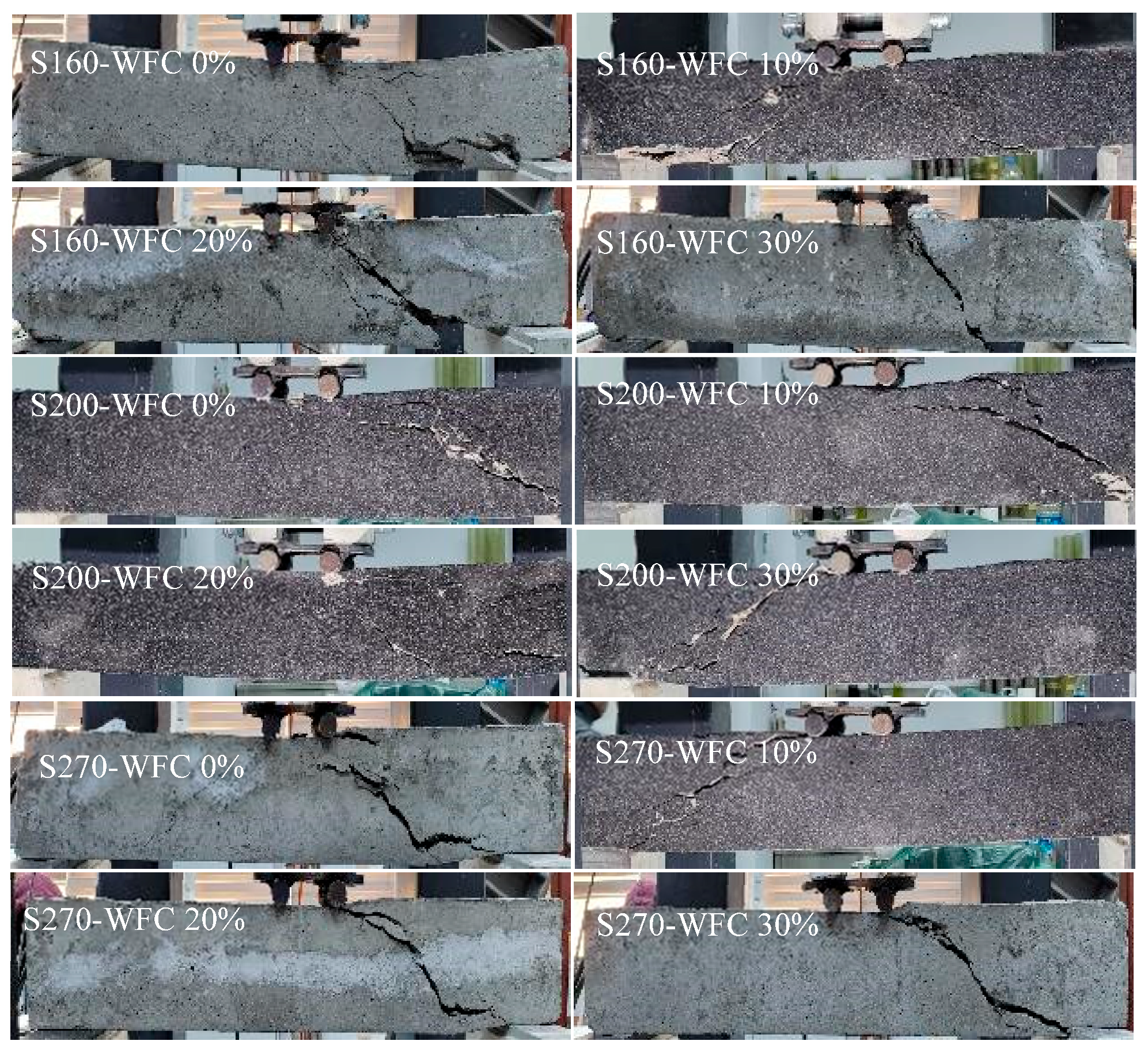

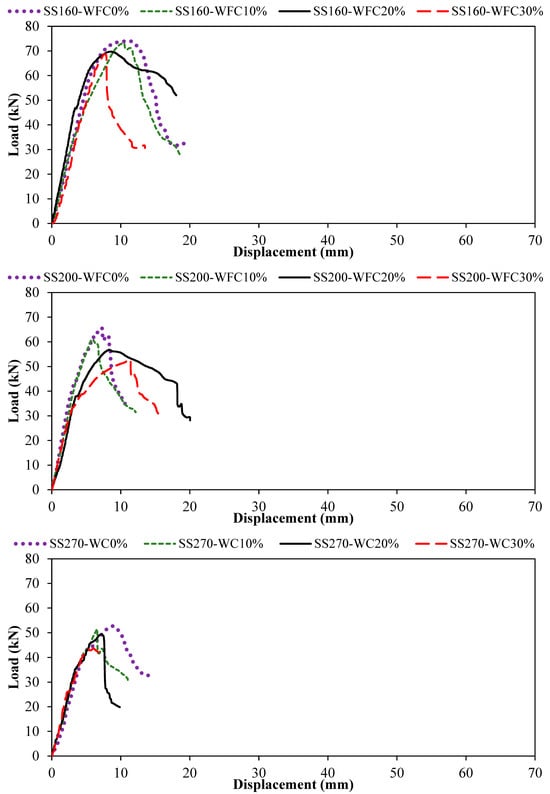

The shear behavior of reinforced concrete beams was investigated for four WFC contents: 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%. The influence of WFC content was evaluated for three stirrup spacings: 160 mm, 200 mm, and 270 mm. Figure 6 presents the load–displacement responses of the beams used to investigate shear behavior for different WFC contents and stirrup spacings. For the 160 mm stirrup spacing, the maximum load-bearing capacity and corresponding deformation were 74.07 kN and 11.24 mm, respectively, for 0% WFC. When the WFC content was increased to 10%, these values were 73.17 kN and 10.50 mm. For WFC contents of 20% and 30%, the maximum load-bearing capacity and deformation were obtained as 69.74 kN–8.62 mm and 68.72 kN–7.83 mm, respectively. In addition, the displacement values corresponding to the reduced load stage, as reported in Table 2, were recorded as 19.76 mm at 31.63 kN, 18.66 mm at 27.33 kN, 18.02 mm at 52.01 kN, and 13.50 mm at 30.65 kN for WFC contents of 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%, respectively. As shown in Figure 6, compared with the reference beam (0% WFC), the maximum load-bearing capacity decreased by 1.22%, 5.85%, and 7.22% for WFC contents of 10%, 20%, and 30%, respectively.

Figure 6.

Graphs of load displacement for varying stirrup spacing and WFC percentages.

Figure 6 illustrates the load–displacement responses of reinforced concrete beams with 200 mm stirrup spacing for different WFC contents. The reinforced concrete beam’s maximum load-bearing capacity and corresponding deformation were 65.47 kN and 7.32 mm, respectively, for 0% WFC. When the WFC content increased to 10%, these values became 60.98 kN and 5.90 mm. The corresponding results for WFC contents of 20% and 30% were 56.80 kN–8.34 mm and 52.70 kN–11.38 mm, respectively. In addition, the displacement values corresponding to the reduced load stage, as reported in Table 2, were recorded as 10.83 mm at 33.64 kN, 12.16 mm at 31.44 kN, 20.04 mm at 28.15 kN, and 15.76 mm at 29.26 kN, respectively. As shown in Figure 6, compared with the reference beam (0% WFC), the maximum load-bearing capacity decreased by 6.86%, 13.25%, and 19.51% for WFC contents of 10%, 20%, and 30%, respectively.

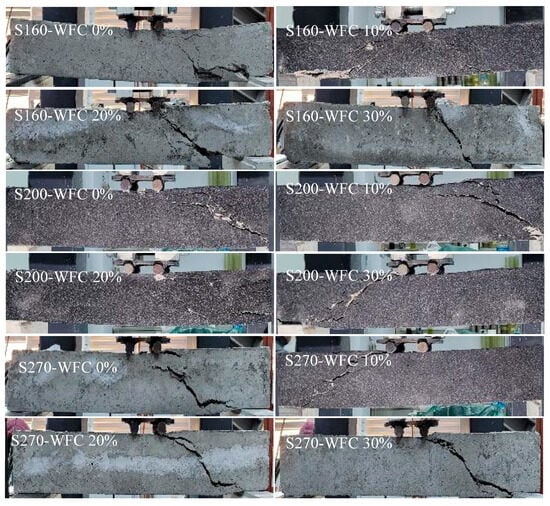

As illustrated in Figure 6, the load–displacement responses of reinforced concrete beams with 270 mm stirrup spacing vary with WFC content. For the reference beam with 0% WFC, the maximum load-bearing capacity and corresponding deformation were 52.68 kN and 8.80 mm, respectively. When the WFC content was increased to 10%, these values decreased to 51.52 kN and 6.59 mm. For WFC contents of 20% and 30%, the maximum load-bearing capacity and deformation were obtained as 49.37 kN–7.19 mm and 43.57 kN–6.03 mm, respectively. In addition, the displacement values corresponding to the reduced load stage, as reported in Table 2, were recorded as 14.05 mm at 32.71 kN, 11.06 mm at 30.09 kN, 9.86 mm at 19.81 kN, and 7.69 mm at 41.34 kN for WFC contents of 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%, respectively. Compared with the reference beam (0% WFC), the maximum load-bearing capacity decreased by 2.20%, 6.28%, and 17.29% for WFC contents of 10%, 20%, and 30%, respectively, as shown in Figure 6. The results indicate that increasing stirrup spacing leads to a reduction in the maximum load-bearing capacity of the beams. Moreover, for all three stirrup spacings, an increase in WFC content results in a consistent decrease in shear resistance. The fracture behavior of the beams under bending is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Shear-dominated crack patterns in beams with different stirrup spacings.

It is observed that higher WFC replacement levels generally reduce the load-bearing capacity of reinforced concrete beams under both flexural and shear-dominated responses, particularly when compared with the reference (0% WFC) specimens. This trend is consistent with findings reported for other fired-clay-based cement replacements, such as waste clay brick. In that context, the reduction in strength has been attributed mainly to (i) a dilution effect due to partial cement replacement, which lowers the amount of hydration products, and (ii) increased porosity in the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between the clay-based particles and cement paste, potentially weakening the overall bond [43].

In this study, ductility is defined in accordance with conventional reinforced concrete design practice as μ = δu/δy, where δy is the yield displacement and δu is the ultimate displacement corresponding to the onset of post-peak degradation. The ductility ratio was recalculated using the standard structural definition:

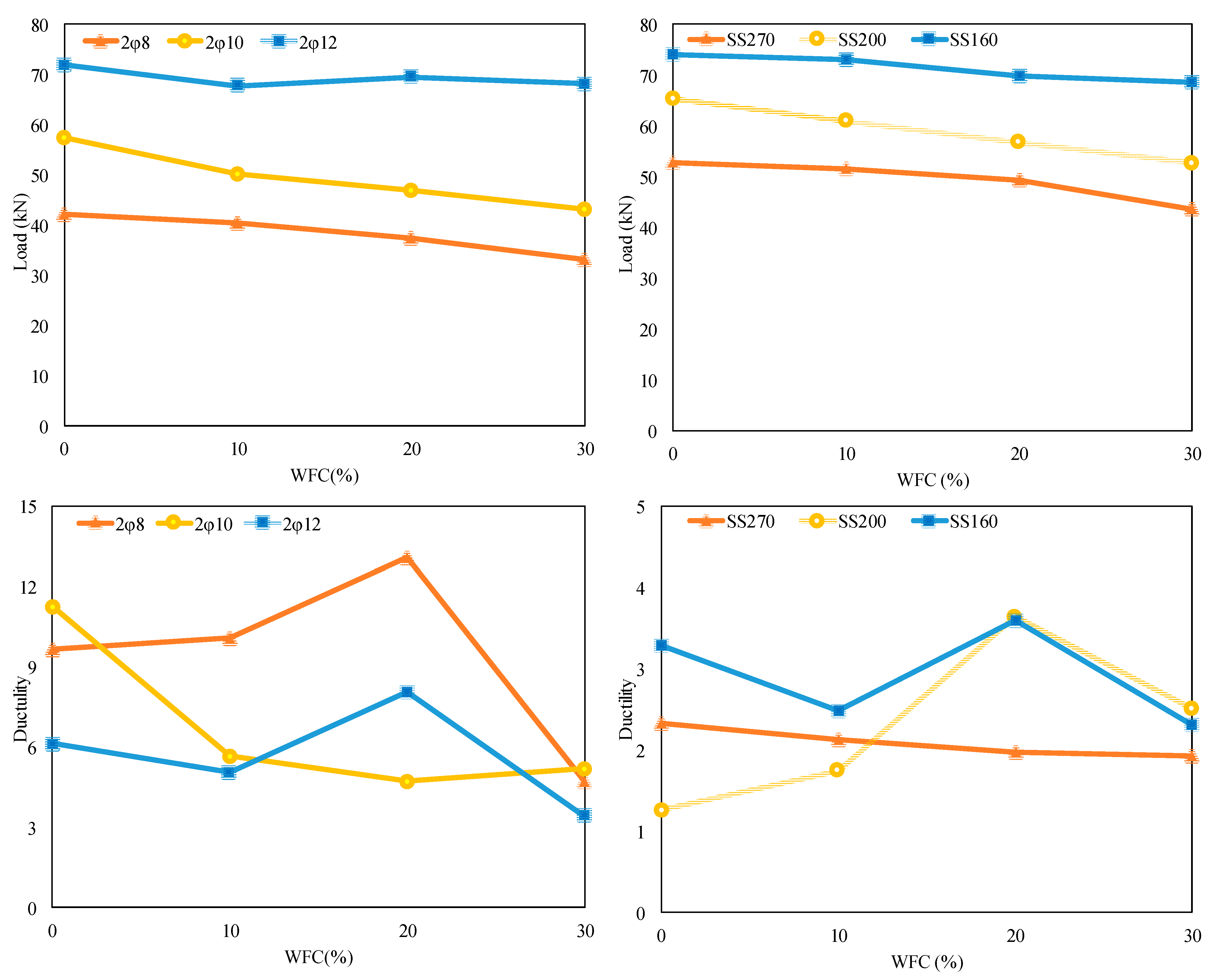

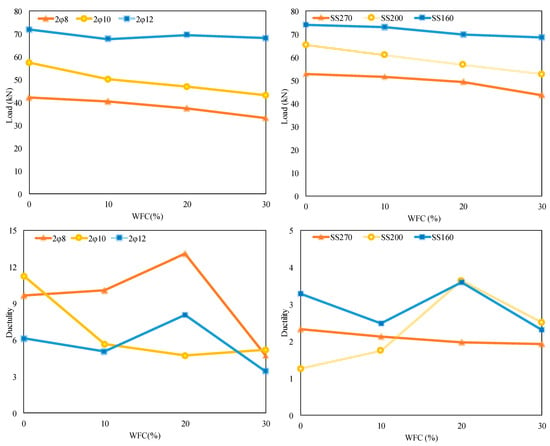

The yield displacement δy was identified at the point where the descending branch reached 0.85 Pmax. The ultimate displacement δu was taken as the maximum displacement attained prior to significant post-peak strength degradation. The ductility values of beam components that include varying fractions of WFC are shown in Table 2. These ductility values correspond to flexural behavior; shear-related deformation capacities are evaluated separately. Load-carrying and ductility values for varying WFC contents are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Load-carrying and ductility values according to varying WFC contents.

When the WFC replacement level increased from 0% to 30%, the ductility ratios of the Φ8 beams under flexural behavior were 9.68, 10.06, 13.08, and 4.74, respectively. Relative to the reference beam (0% WFC), a slight increase in ductility was observed at 10% WFC, followed by a more pronounced increase at 20% WFC. However, a significant reduction in ductility occurred at 30% WFC, indicating a loss of post-peak deformation capacity at higher replacement levels. For the Φ10 beams, the ductility ratios corresponding to WFC contents of 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% were 11.24, 5.68, 4.72, and 5.21, respectively. Compared with the reference specimen, a substantial decrease in ductility was observed at 10% and 20% WFC, while a slight recovery was noted at 30% WFC, although the ductility remained lower than that of the control beam. For the Φ12 beams, the ductility ratios were 6.15, 5.06, 8.06, and 3.44 for WFC contents of 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%, respectively. These results indicate a moderate reduction in ductility at 10% WFC, followed by an increase at 20% WFC, and a notable decrease at 30% WFC, suggesting that excessive WFC replacement adversely affects ductility even at higher reinforcement ratios.

When the same comparison was carried out for shear behavior, distinct trends were observed depending on stirrup spacing. For beams with a 160 mm stirrup spacing, the ductility ratios for WFC contents of 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% were 3.28, 2.49, 3.60, and 2.31, respectively. A reduction in ductility was observed at 10% WFC, followed by an increase at 20% WFC, and a subsequent decrease at 30% WFC. For beams with a 200 mm stirrup spacing, the corresponding ductility ratios were 1.26, 1.75, 3.64, and 2.51, indicating a progressive increase in ductility up to 20% WFC, followed by a reduction at 30% WFC. For the largest stirrup spacing of 270 mm, the ductility ratios were 2.33, 2.12, 1.97, and 1.92 for WFC contents ranging from 0% to 30%. In this case, a gradual decrease in ductility was observed with increasing WFC content, highlighting the combined adverse effect of larger stirrup spacing and higher WFC replacement on post-peak deformation capacity. Beams with 0–20% WFC generally demonstrated moderate ductility levels, whereas 30% WFC replacement led to reduced μ values due to increased brittleness may associated with higher porosity and ITZ weakening.

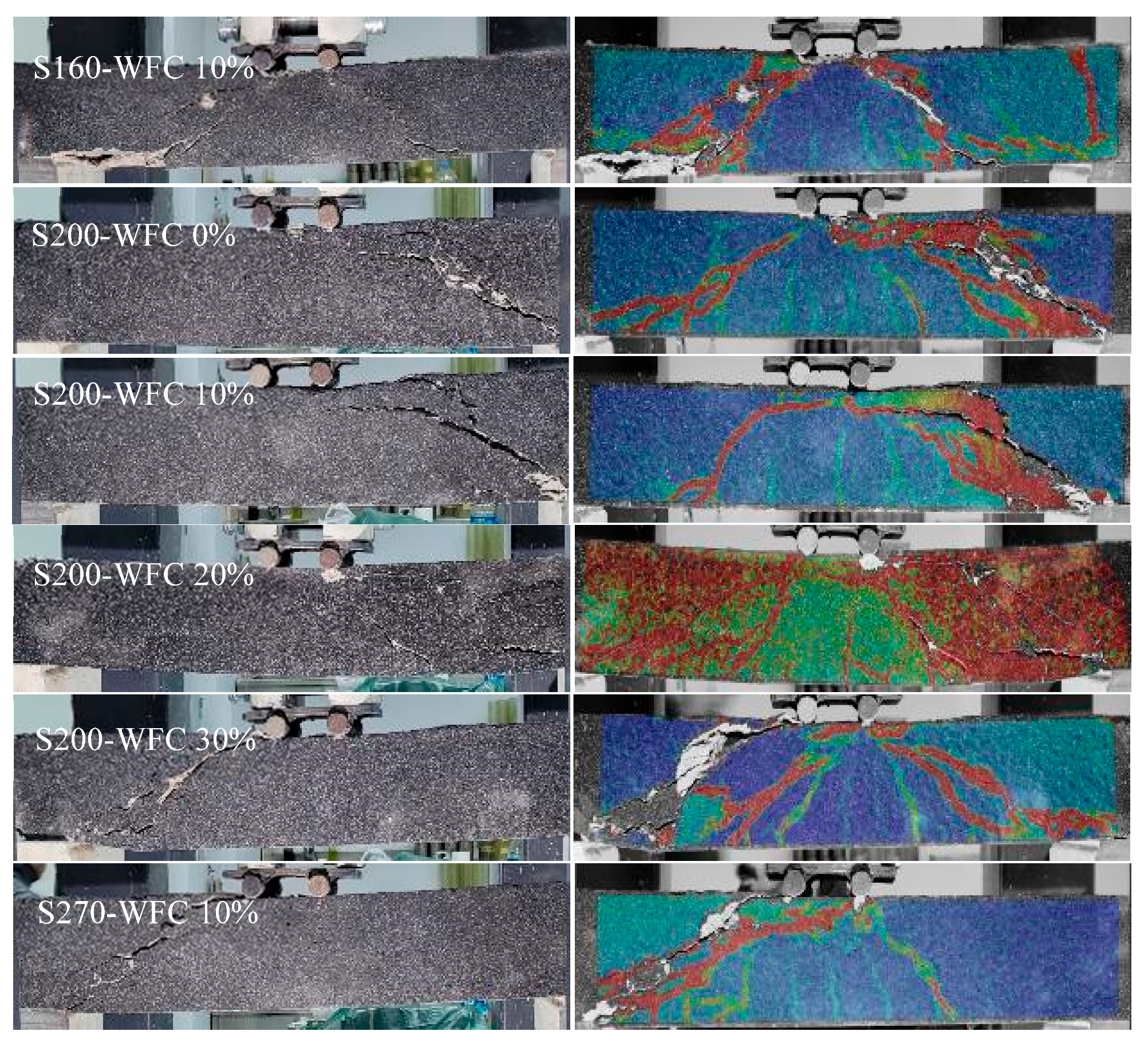

4. Comparative Analysis of Test Results with the Digital Image Method

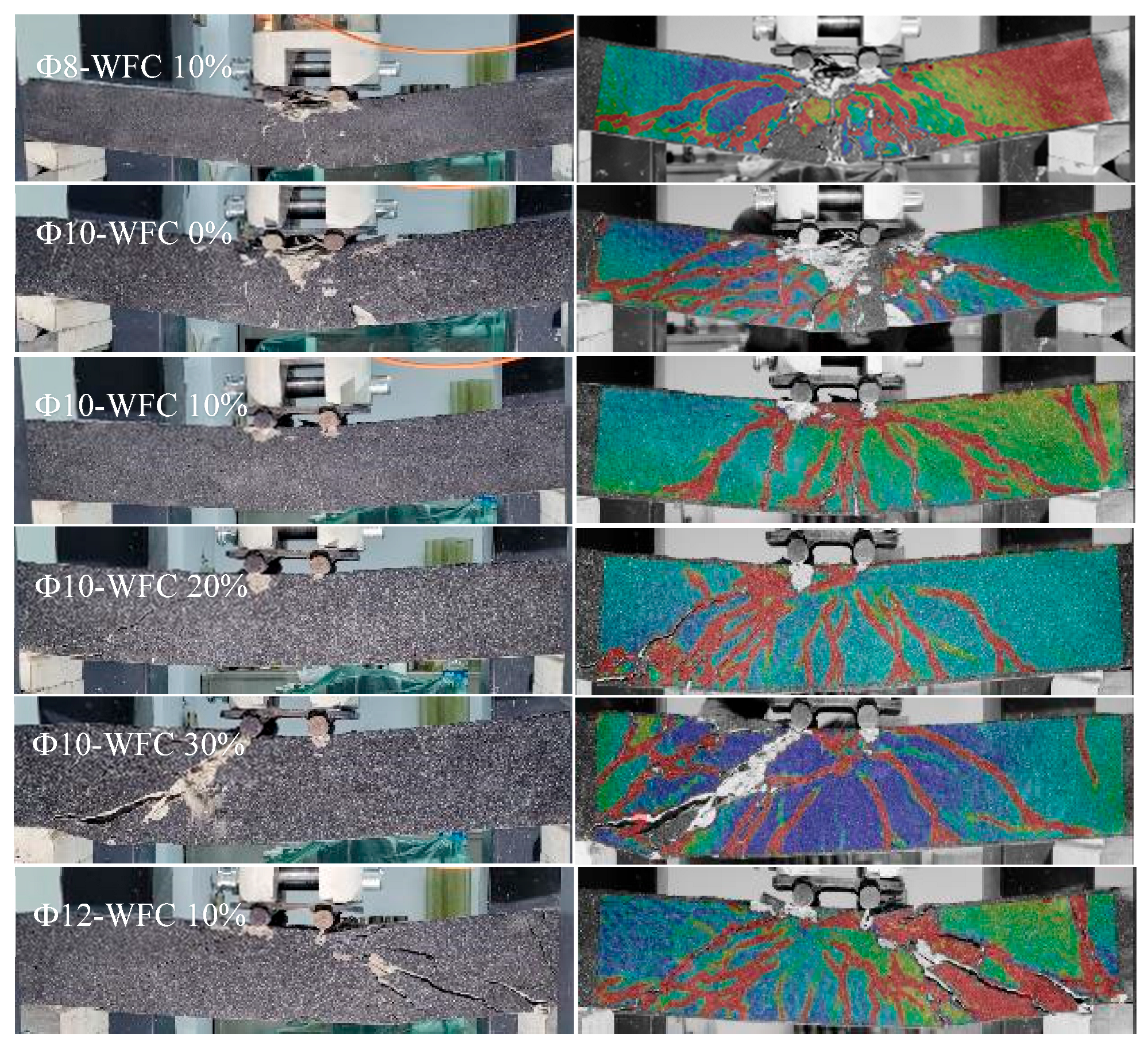

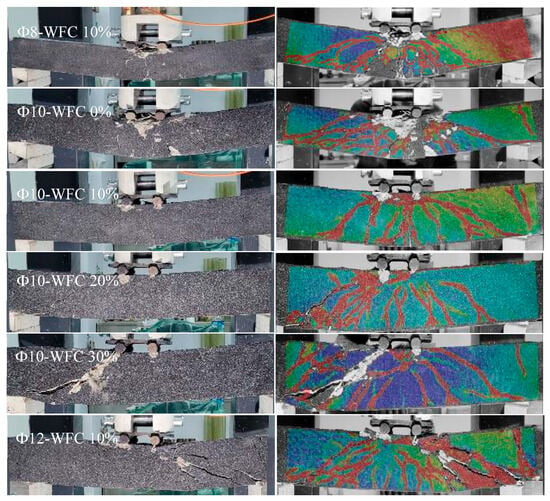

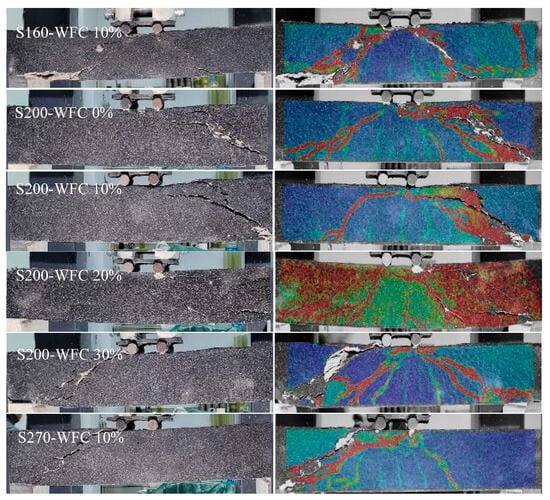

A comparison will be made in this section between the deformation the beam underwent and the data collected using the imaging technique employed throughout the experiment. For image processing purposes, the reinforced concrete beams were painted black, and white speckle points were applied to enhance the visibility of crack initiation and propagation during imaging. Similar studies have been conducted by the authors and more details are provided in [44,45,46,47]. The basic idea here is to convert the grid displacements obtained from digital images into the actual displacement of the reinforced concrete beam test piece. In addition, the digital image of the test sample is highly effective for detecting the presence of microcracks on the surface of the reinforced concrete beam, provided that the strain values are taken into account. The location of damage when the test beam is exposed to the ultimate load is comparable to the locations of potential damage observed earlier during the loading phase. According to the findings of the investigation, as the applied load increases, microcracks that are not visible to the naked eye occur. These microcracks are shown in Figure 9. As observed in Figure 9, the strain concentration in the reinforced concrete test beam subjected to the ultimate load occurs at approximately the same locations as in the reinforced concrete test beam subjected to lower load levels, and the direction of progression is similar; moreover, the strain concentration spreads over a larger portion of the reinforced concrete beam surface. The results of the examination of the displacement values obtained from experimental testing and image processing are presented in Figure 9. As shown in Figure 10, the values obtained from the two methods are comparable.

Figure 9.

Comparison of test beam image processing and experimental rupture observation.

Figure 10.

A comparison of displacement values in experimental and image processing values.

5. Interpretation of Hybrid Physics Data-Driven System Results

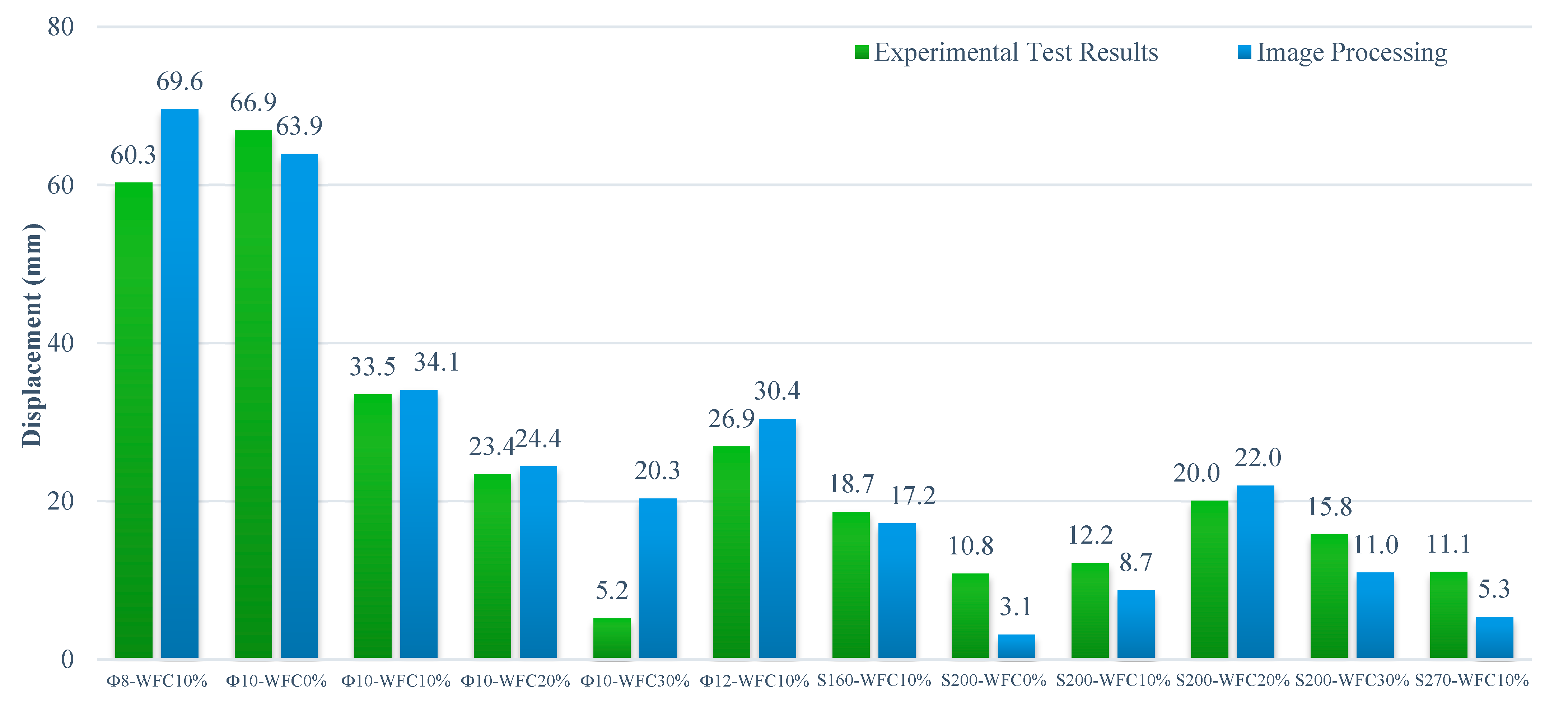

5.1. Correlation Analysis of DIC–CNN Deformation Features

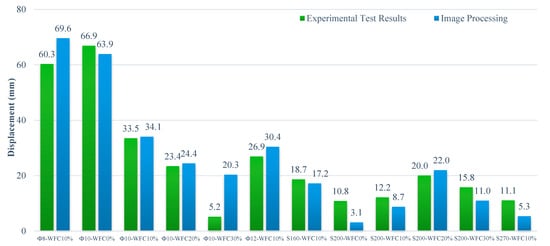

Correlation matrix for DIC–CNN feature set (Figure 11) shows an almost perfectly linear relationship between εx, εγ, and δmax, with correlation coefficients of r ≈ 0.98 across the board, because such near-unity values indicate strong internal coherence of the extracted features and accurately capture the deformation mechanisms expected for RC beams [48]. In the case of flexure-dominated behavior, longitudinal strain, transverse strain, and mid-span displacement evolve together with increasing curvature, and the persistence of such strong correlations is thus evidence that the CNN encoder preserved the fundamental kinematics of the beam, free from numerical artifacts or oversmoothing of physically meaningful gradients.

Figure 11.

Correlation matrix heatmap.

The strong correlation between εx and εγ is consistent with prior observations of WFC-modified beams, where microcrack development leads to strain redistribution and, consequently, concurrent transverse widening and longitudinal stretching. Moreover, the near-unity correlations between the strain components and δmax indicate physically consistent translation of local strain fields to global displacement [49,50], which suggests that the DIC measurements preserved geometric compatibility throughout loading and that the encoder transformed pixel-level deformation patterns into mechanically meaningful representations. This behavior implies that the strain-derived features reside on a low-dimensional manifold governed by curvature-driven behavior, which is advantageous for the subsequent PINN and ensemble learning stages, as it minimizes redundant use of feature space, while preserving essential structural information. Furthermore, no signs of decorrelation or nonlinear drift are apparent at higher deformation levels, because the oversampling and normalization procedures maintained the integrity of the dataset, and the lack of divergence is especially promising, as small-sample experimental campaigns often magnify noise during preprocessing, while preservation of structural relationships increases confidence in the robustness of the hybrid DIC–CNN feature extraction framework.

5.2. PINN-Based Constitutive Reconstruction and Post-Peak Behavior

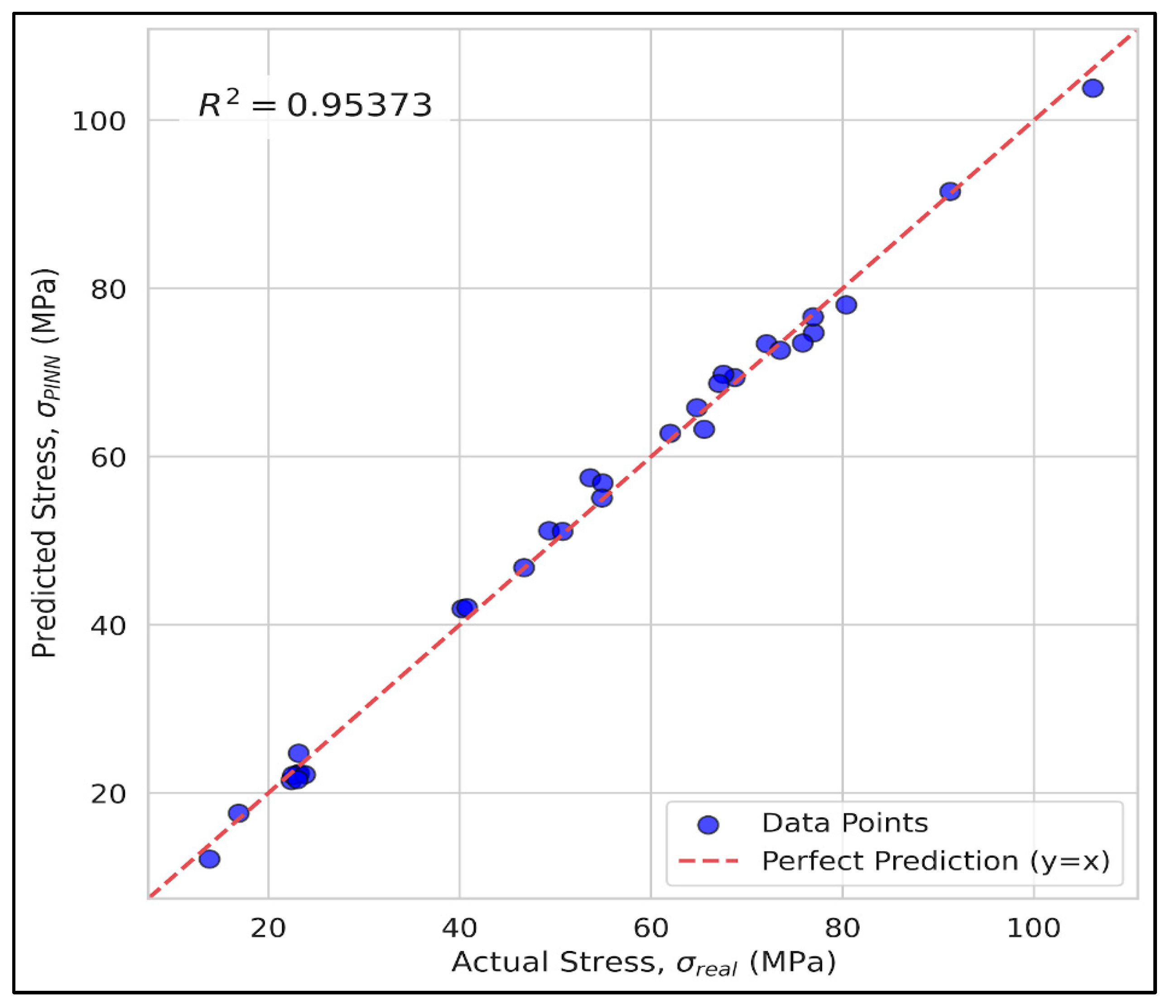

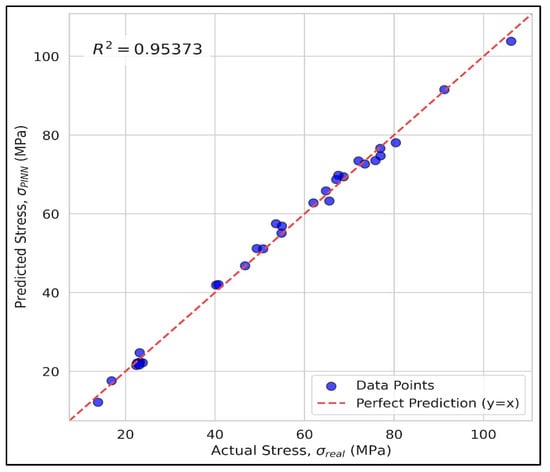

The PINN-predicted stress–strain curves are in excellent agreement with the experimental data, as shown in Figure 12. The agreement between the measured σ–ε response and the PINN prediction over the entire deformation history is excellent, indicating that the model captures the nonlinear mechanical behavior of WFC-modified concrete, including the initial linear-elastic region and the subsequent strain-hardening phase with only minor deviations, which suggests that the network has learned the underlying constitutive behavior of WFC-based cementitious composites, governed by mechanics, in addition to the empirical patterns. The strong agreement is mainly attributed to the formulation of the PINN loss function, which, in addition to the data-fitting residual, also includes the equilibrium-based residual and the monotonicity-based residual that penalize the violation of σ′(ε) > 0 and discontinuities in the stress–strain curve, respectively. These penalties drive the network to find mechanically admissible solutions throughout the loading process, and such constraints are especially important for WFC-based cementitious composites, where microstructural heterogeneity may result in irregular stiffness variations and scattered test results. In this context, the PINN acts as a physics-aware filter to remove noise and preserve the characteristic curvature of the σ–ε envelope, consistent with recent findings on physics-guided learning of heterogeneous materials [51,52].

Figure 12.

Experimental and PINN-predicted stress responses of WFC-modified reinforced concrete beams under monotonic loading.

Monotonicity constraints are enforced in the PINN framework only up to the peak region and relaxed past peak stress so the model can capture the experimentally observed softening. The main advantage of the PINN framework is its stability in the high-strain, near-peak region (≈60–100 MPa), which is difficult to capture with small experimental datasets due to the strong fluctuations in the measurements induced by rapid crack growth and localized strain bands; nevertheless, the PINN produced consistent predictions in the range ε ≈ 0.0025–0.0035, demonstrating the effectiveness of the derivative-based regularization in keeping stresses bounded and preventing the model from overfitting to individual noisy points. The network also successfully replicated the experimentally observed loss of stiffness and decrease in peak stress at higher WFC dosages, which shows that the PINN remains sensitive to key degradation mechanisms—such as increased ITZ porosity and reduced C–S–H formation—without masking or over-smoothing their effect. The clustering of the PINN-predicted points further supports the claim that the model preserves meaningful differences between mixes rather than collapsing all data onto a single averaged constitutive curve, as mixes with higher WFC dosages, which systematically exhibited lower stress at equivalent strain levels, were clearly distinguished by the network. Capturing mix-specific mechanical signatures is important for the subsequent NSGA-II optimization, because a precise description of the relationship between σ–ε behavior and WFC content is required to ensure that the optimization stage reflects material sensitivities and yields reliable, physically grounded Pareto-optimal design solutions.

5.3. NSGA-II-Based Design-Space Exploration and Trade-Off Analysis

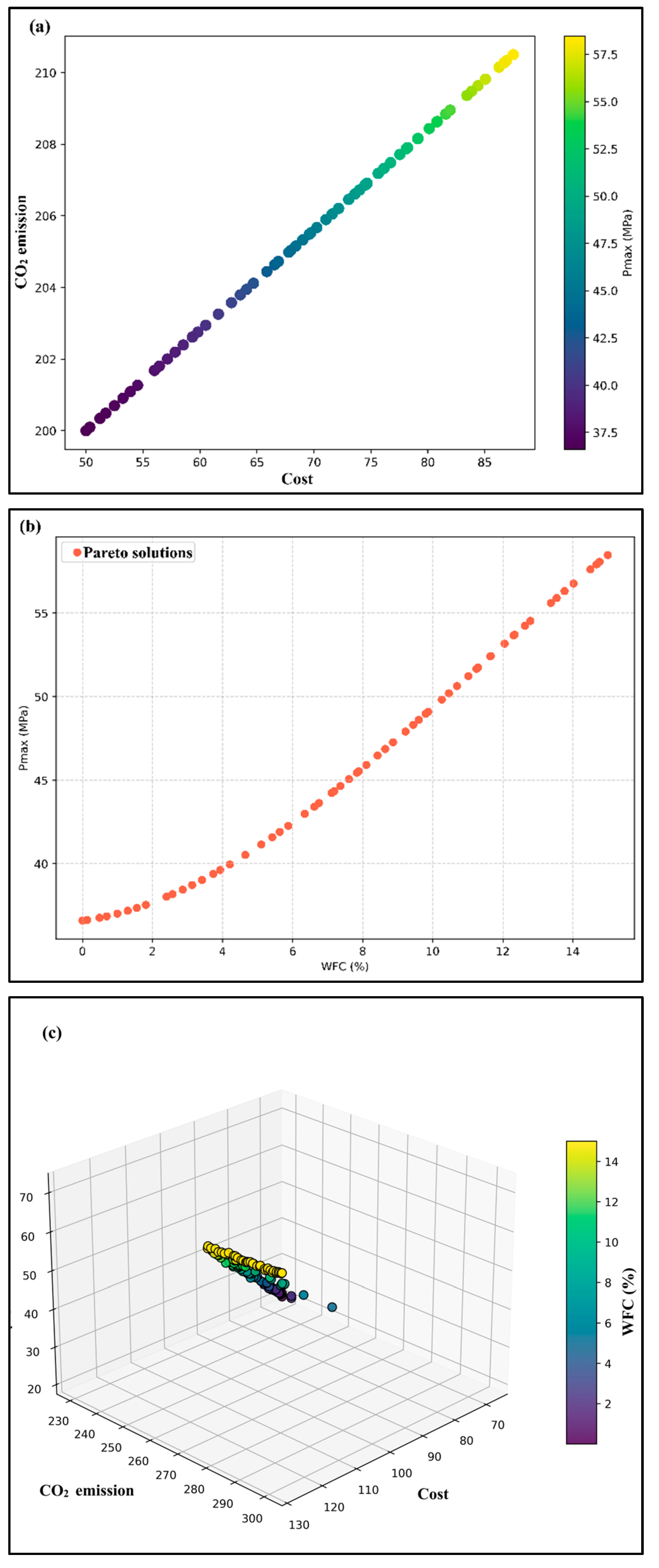

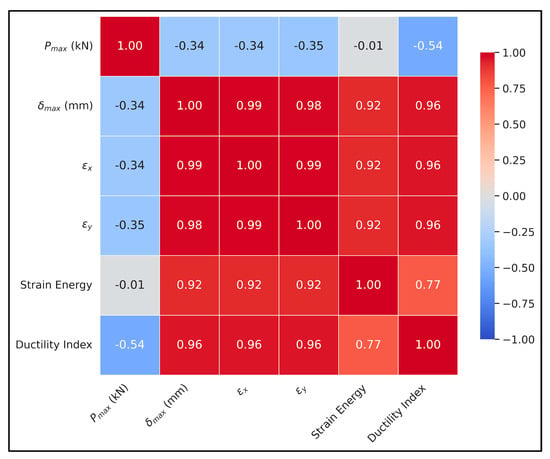

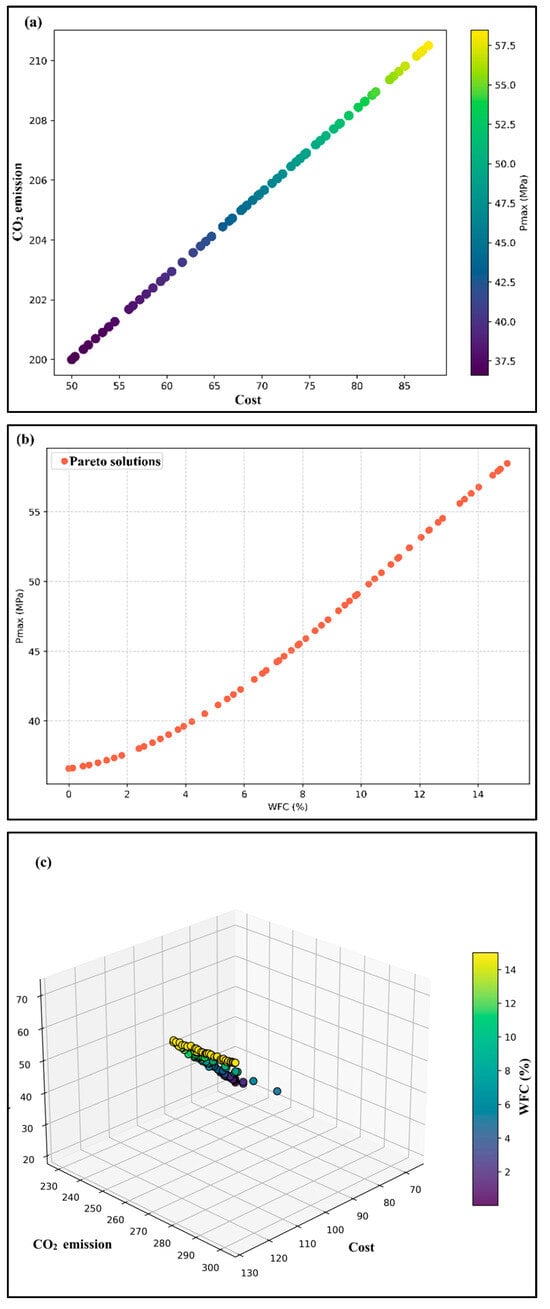

The NSGA-II optimization framework is used to systematically explore the trade-off between Pmax, material cost, and CO2 emissions for mixtures with different WFC contents. The 2D Pareto front in Figure 13a shows a smooth, monotonic trend, as expected, since cement content essentially controls both cost and embodied CO2, and the fact that an almost linear trade-off is found instead of multiple competing local optima within the considered design space can be attributed to the fact that the cost–CO2 projection considered in this work is approximately linear, as cement dominates both objectives. Thus, the present optimization should be considered as a design space exploration rather than as evidence of a strongly nonlinear cost–CO2 interaction. Mixtures with higher Pmax present higher cost and CO2 emissions, which is consistent with the behavior of cement-based composites: higher performance usually requires more cement and denser microstructures, which lead to a larger environmental impact and production costs, and the near-linear relationship between cost and CO2 indicates a direct, proportional influence of the input variables on both metrics. Since cement production is the main driver of embodied carbon and cost, the optimization naturally favors cement-reduced mixtures when the main objective is to minimize CO2.

Figure 13.

NSGA-II-based design-space exploration results for WFC-modified concrete mixtures: (a) Pareto-based cost–CO2 trade-off illustrating feasible design tendencies, (b) corresponding Pareto-optimal mixture solutions, and (c) the associated design response surface derived from the optimization domain.

The incorporation of WFC, however, clearly creates a trade-off, since lower CO2 emissions are achieved at the expense of lower mechanical strength; consequently, WFC-containing mixtures fall in the low-carbon but lower-strength region of the Pareto space, suggesting that WFC can be an attractive choice if the environmental performance is preferred over maximum structural capacity. The evolution of the population in Figure 13b confirms once more the robustness of the NSGA-II search process, and the population evolves from an initial widely spread distribution into a compact and well-defined Pareto front, which is indicative of a maintained genetic diversity and an avoided premature convergence, a common issue in multi-objective evolutionary optimization [53]. An interesting observation is the identified strength-improving trend with WFC contents of 12–14% by mass, and in this range, modest WFC additions contribute to micro-filling and packing benefits without compromising the cementitious matrix, which results in a balanced optimum. The predicted decrease in Pmax for higher WFC contents is also consistent with experimental findings indicating that increased WFC contents lead to higher porosity and a weaker interfacial transition zone, which ultimately decreases the load-bearing capacity of the concrete [54].

The 3D Pareto surface, shown in Figure 13c, provides a more holistic view of the optimization space, showing Pmax, cost and CO2 emissions as functions of WFC content, and the layering is clearly visible with low-WFC-content mixtures falling in the high-strength, poor environmental performance category, while high-WFC-content mixtures are concentrated in the low-carbon region but suffer from a reduced structural capacity. The smooth gradient in the direction of WFC dosage further highlights its critical influence on the optimization path, and this is a point that will be further emphasized in the next SHAP analysis.

It is important to note that NSGA-II alone does not provide physically reliable or experimentally consistent solutions. Although the algorithm adeptly navigates the trade space, its exclusively evolutionary characteristics do not naturally impose mechanical limitations or ensure constitutive consistency. This study’s accuracy in identifying the Pareto front is fundamentally reliant on the physically anchored predictions produced by the PINN model and the feature-level interpretability provided by SHAP. Without these hybrid components, NSGA-II can likely converge to mathematically optimal yet mechanically unrealistic mixtures—an issue widely reported in concrete optimization literature. Thus, the strong performance of the optimization results from the synergy between NSGA-II and the physics- and data-informed models that guide it, rather than from the evolutionary algorithm alone.

It should be noted that all reinforced concrete beams in the experimental program were cast with a constant W/B of 0.46, and neither CNN-based deformation features nor PINN-based constitutive learning involve any change in W/B; therefore, the physics-informed surrogate learns, infers or encodes no mixture-sensitive mechanical trends resulting from a change in W/B. The presence of W/B in the SHAP analysis results from the subsequent NSGA-II design-space exploration where bounded, hypothetical perturbations of W/B were introduced only to explore potential strength cost–CO2 trade-offs for future mix scenarios, and such hypothetical W/B values were never used during CNN or PINN training, while no model parameters were calibrated using unobserved W/B variations. The SHAP sensitivity associated with W/B should therefore be understood as a property of the optimization domain and not as an experimentally validated constitutive trend, because this clarification maintains full methodological consistency: the hybrid surrogate remains strictly physics-consistent within its calibrated experimental domain (W/B = 0.46), while the optimization outcomes are presented as exploratory design tendencies and not as confirmed mixture-dependent mechanical responses.

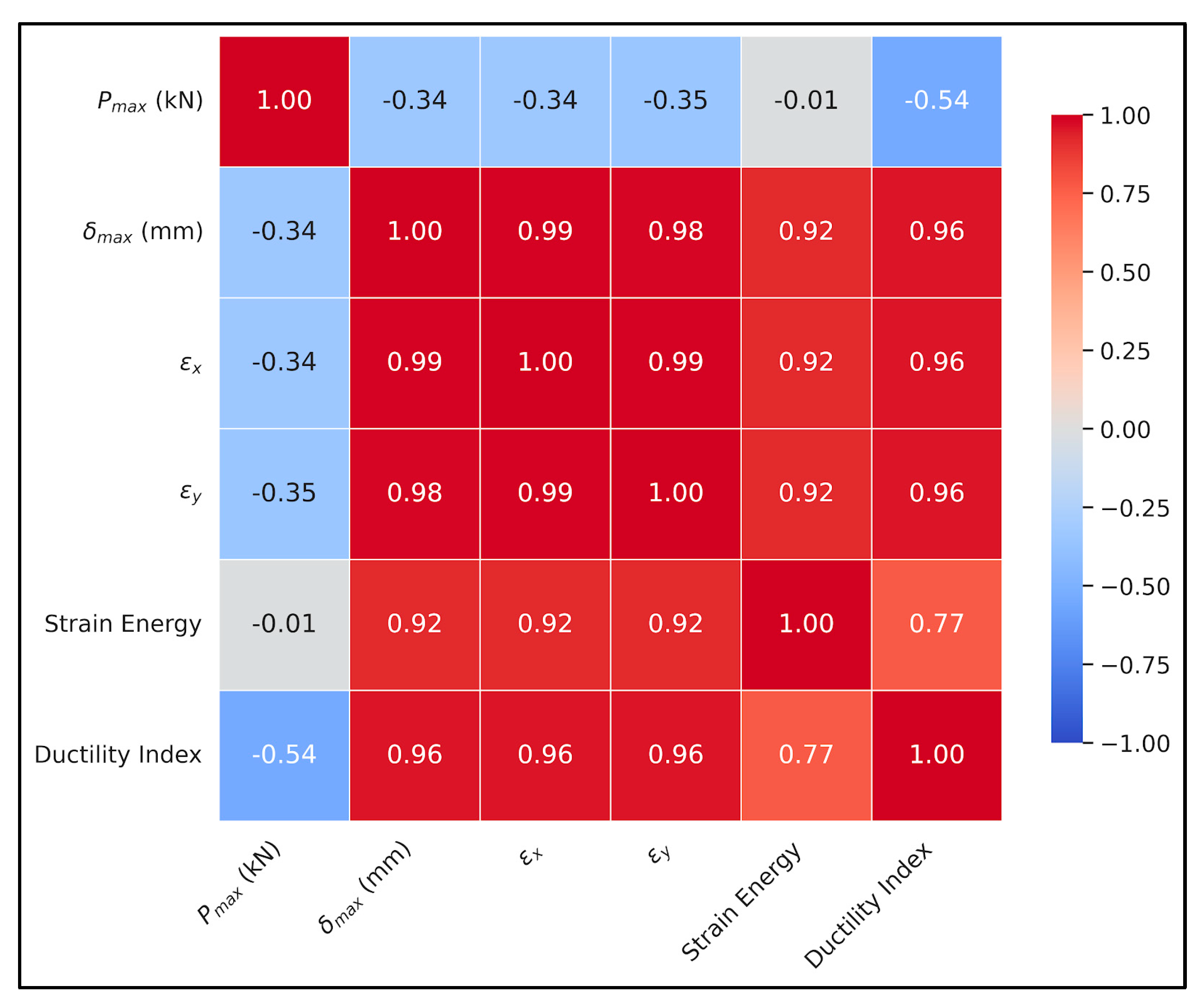

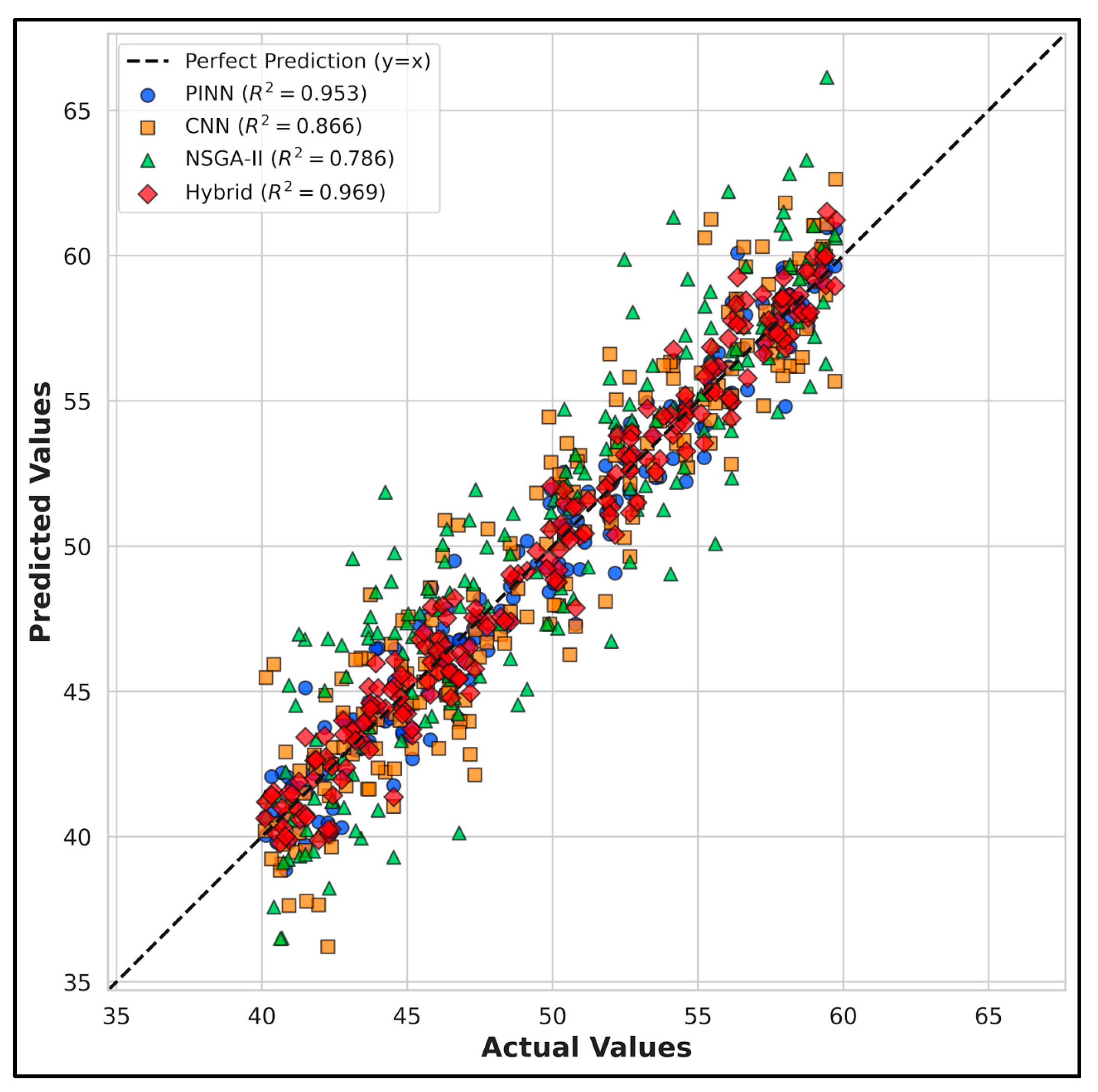

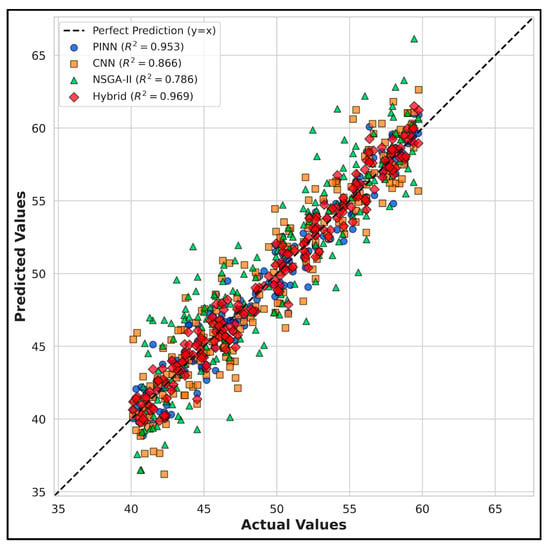

5.4. Hybrid Surrogate Performance and Ensemble Behavior

The hybrid ensemble model achieved the highest predictive accuracy across the framework by combining the physics-consistent constitutive reconstruction of the PINN with the deformation-sensitive feature extraction of the CNN (Figure 14). This integration resulted in a marked improvement in prediction fidelity (R2 = 0.969) compared to the standalone PINN (R2 = 0.953) and CNN (R2 = 0.866). NSGA-II was not employed as a predictive component; instead, it was used downstream to explore parametric trends and multi-objective trade-offs within the bounded design space.

Figure 14.

The performance comparison of the utilized models and the proposed hybrid system.

The most striking feature is the obvious reduction in scatter around the ideal prediction line (y = x), while the CNN may occasionally underestimate peak stress, as image-derived features are sensitive to noise, and the NSGA-II algorithm is generally expected to produce more scattered predictions, given its inherently stochastic, evolutionary nature; however, the ensemble as a whole is observed to strongly dampen these effects thanks to the weighting strategy. The PINN provides smooth, physics-consistent σ–ε trajectories, the CNN brings sensitivity to crack-induced nonlinearities that traditional numerical models cannot capture, and the NSGA-II explores a broader design space by considering intermediate WFC contents and reinforcement layouts that are very sparsely represented in the experimental data. This improved accuracy is a clear demonstration of the benefits of integrating complementary sources of knowledge: the CNN extracts rich deformation textures and pixel-level strain fields that help resolve the timing and manner of crack initiation and propagation, the PINN ensures constitutive monotonicity and equilibrium, keeping its predictions physically admissible even in noisy or poorly sampled regions, and the NSGA-II offers a multi-objective perspective by considering strength, cost, and CO2 emissions simultaneously as the WFC dosage changes. When the CNN- and PINN-based predictors are combined through a validation-guided ensemble procedure, prediction variance is drastically reduced, and the NSGA-II adds an extra layer of insight at the optimization stage; consequently, from a structural mechanics perspective, the high R2 value suggests that the ensemble is capable of capturing both the global load–deformation response and the localized, damage-induced nonlinearities. This is particularly important for concrete, where microstructural variability, porosity in the interfacial transition zone, and fluctuations in pozzolanic reactivity introduce complexities that conventional constitutive models are unable to represent; therefore, the hybrid ensemble acts as a robust offline digital surrogate that leverages image-based deformation information, physics-informed constitutive modeling, and optimization-driven parametric sensitivity to deliver stable, interpretable, and highly accurate predictions across the full experimental domain [55,56].

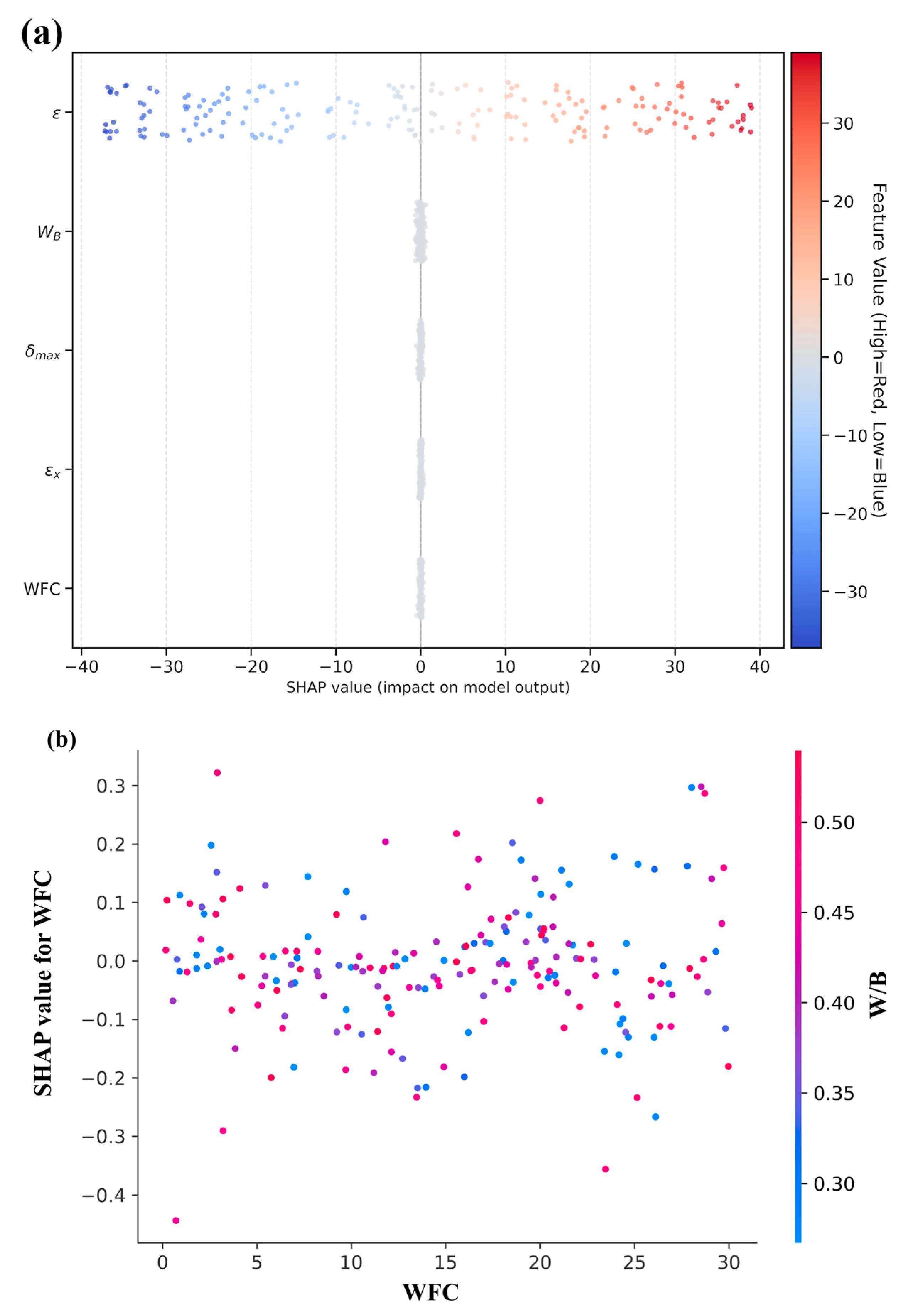

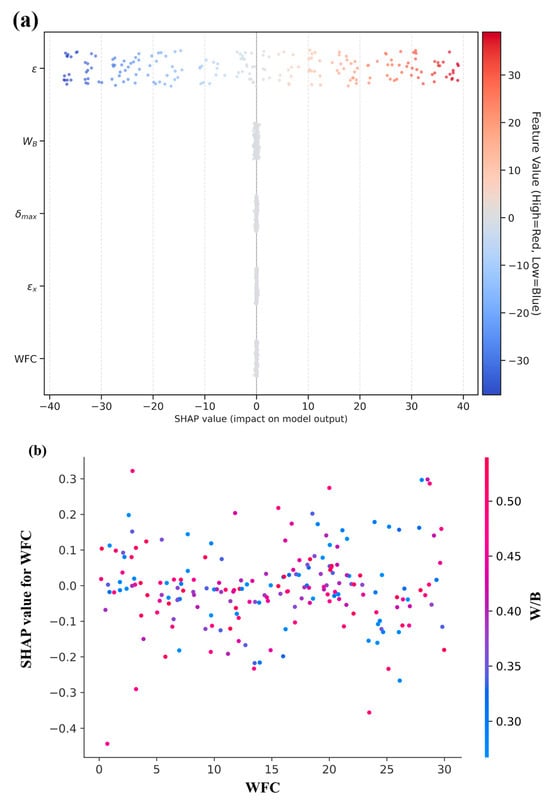

5.5. SHAP-Based Interpretability and Micro-Mechanical Insights

The SHAP distributions for WFC exhibit a distinctly nonlinear and heterogeneous effect of WFC on structural performance, as a consequence of the complex role played by waste fired clay particles in the cementitious matrix, because WFC SHAP values fluctuate around zero across the compositional space (Figure 15a), which implies that WFC functions as a conditional modifier of the response rather than a control variable per se. Such behavior is typical of inclusions that simultaneously impart beneficial mechanisms (e.g., micro-filling-driven stress redistribution) and detrimental ones (e.g., increased porosity, weakened interfacial transition zone), and the hybrid model’s capacity to capture this dual behavior lends credence to the idea that the predictions of the model are based on physical mechanisms rather than oversimplified linear trends. The color gradients for W/B in Figure 15b indicate that the hybrid system has learned a three-way interaction between deformation, binder chemistry, and WFC content, while at low W/B, WFC particles are poorly lubricated, which facilitates particle clustering and weakens particle-matrix bonding, as reflected by predominantly negative SHAP values. As W/B increases, improved workability and more favorable hydration conditions alleviate these issues, and WFC SHAP values become neutral or positive; therefore, the reversal in sign with W/B reveals that the hybrid model is implicitly capturing the microstructural behavior of WFC-enhanced composites from the data itself, rather than adhering to pre-defined analytical expressions. SHAP analysis shows that the hybrid surrogate is sensitive to micromechanical nuances that conventional regression models would struggle to discern; moreover, the scatter of points in the WFC–SHAP space, in addition to the systematic color changes associated with W/B, indicate that the model captures local variations in crack morphology, strain localization, and interfacial integrity features that are typically ignored in conventional mixture design approaches. This suggests the promise of hybrid ML physics models as high-resolution “behavioral microscopes” that can interpret complex material responses arising from nonlinear interactions among binder hydration, aggregate structure, and WFC replacement.

Figure 15.

SHAP plots. (a) Global Feature Contributions in the Hybrid Surrogate Model. (b) SHAP Dependence Plot Illustrating the Interaction Between WFC Content and the Water Binder Ratio.

A quantitative comparison of the models clearly demonstrates that the hybrid surrogate model performs better than any of its individual components because it has the highest predictive accuracy with R2 close to 0.97, and simultaneously the lowest RMSE and MAE among all models investigated, indicating that prediction is more robust and reliable when physics-informed learning from PINN, high-resolution strain information from CNN and parametric exploration via NSGA-II are combined rather than when any of these approaches are used individually. The standalone PINN model, which is the second most accurate model, consistently reaches R2 values above 0.95, which indicates the benefits of encoding the constitutive laws and equilibrium constraints into the training process; moreover, its low RMSE values further demonstrate that the PINN model is capable of accurately replicating the nonlinear σ–ε response with high fidelity over the entire deformation range even if it is trained on a relatively small experimental dataset, which confirms its generalization ability and numerical stability. However, the CNN model, though reasonably accurate with R2 of around 0.86, has higher RMSE and MAE values than the PINN model because of the sensitivity of image-based features to the heterogeneous crack patterns, local noise, and pixel-level deformation artifacts, all of which make purely vision-driven predictions more challenging. Nonetheless, the CNN is very powerful in resolving localized strain fields and spatial deformation patterns and provides fine-scale information inaccessible to purely numerical or physics-only models, which is why the CNN remains a vital part of the ensemble. As expected, the NSGA-II surrogate on its own yields the lowest predictive accuracy, with R2 values of about 0.78 and significantly higher scatter, which is consistent with its primary role as an evolutionary optimizer, designed to explore a large design space and to identify Pareto-efficient trade-offs, but not to provide highly accurate pointwise predictions; still, the NSGA-II makes an important contribution to the hybrid framework by introducing parametric diversity and by characterizing nonlinear trade-offs between strength, cost and CO2 emissions. By pooling these complementary strengths, the hybrid ensemble attains the lowest RMSE, MAE and MAPE of all models studied, with very small deviations from the experimental data and high predictive reliability, which demonstrates how the ensemble counteracts the limitations of each sub-model: the PINN enforces physical consistency and stabilizes the constitutive response, the CNN enhances sensitivity to local deformation and crack-driven nonlinearities, and NSGA-II adds a broad multi-objective view that enriches exploration of the design space, thereby forming a predictive framework that is well balanced, interpretable and highly accurate—frequently matching and in many cases exceeding the precision of the experimental results across all performance indicators.

5.6. Physics Validation and Digital Representation Consistency

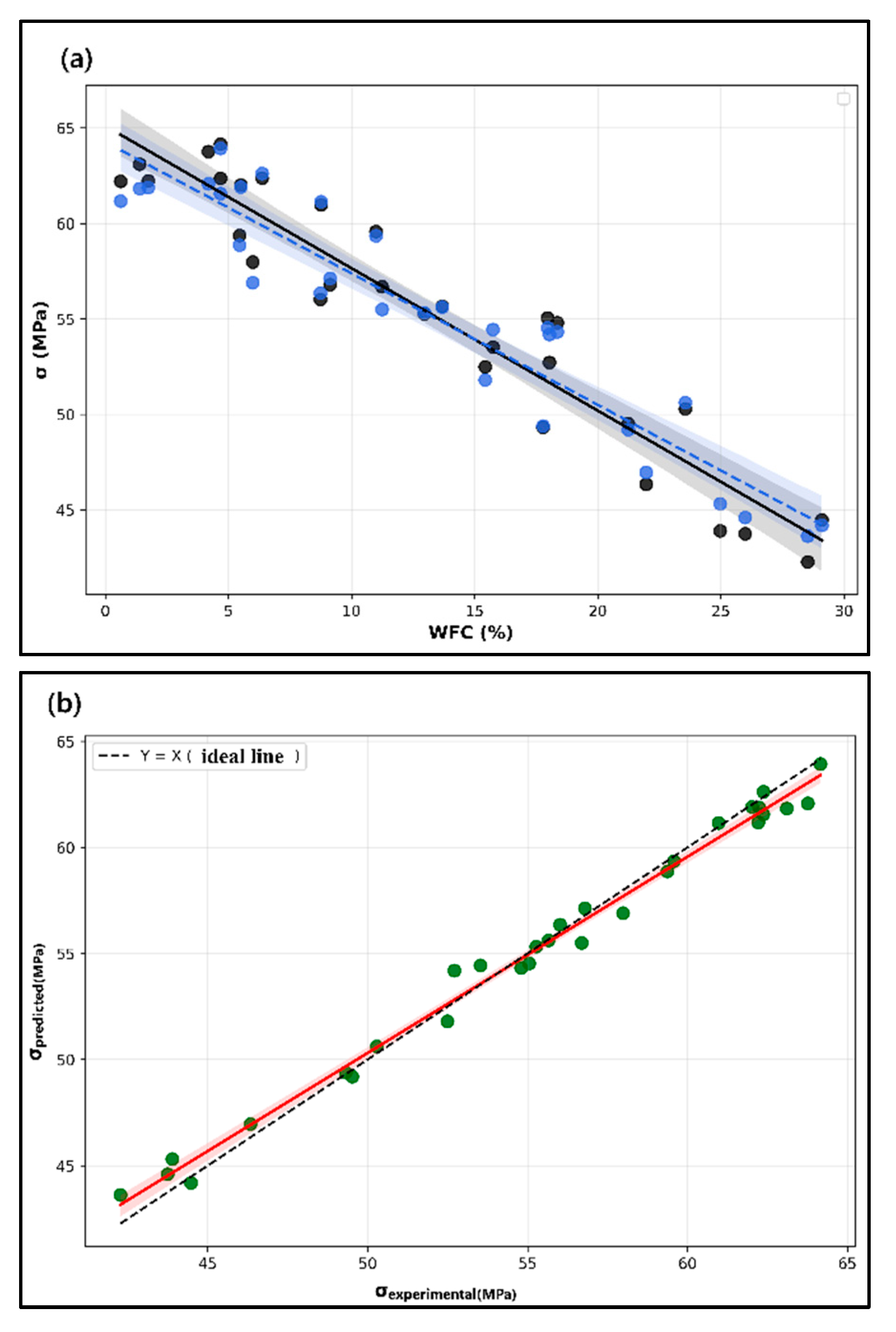

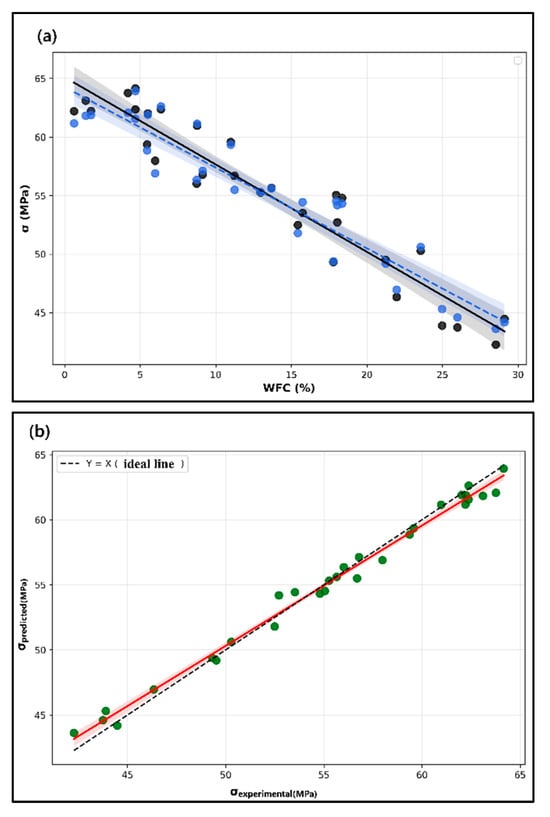

The robustness of the model across the whole composition range is further confirmed by the small confidence interval for the predicted path, and the hybrid model always achieves a highly accurate and stable prediction, although higher-WFC compositions show larger experimental dispersion due to greater variations in the material structure and interfacial defects. The PINN term is especially useful in imposing the mechanical constraints by physics-based regularization, as can be seen by the stable response in Figure 16a; moreover, the model reproduces the local nonlinear responses related to WFC particle clustering, poor dispersion and microcracking, as demonstrated by the excellent correlation between measured and predicted σ–WFC trends.

Figure 16.

Physics validation results. (a) Physics-Based Validation of the WFC–Stress Relationship. (b) Digital Representation Overlay of Experimental and Predicted Stress.

The physics-validation study also demonstrates that the hybrid model can capture the mechanical physics involved in the behavior of WFC-modified concrete beams, as shown in Figure 16a, where both experimental measurements and model predictions show a clear declining trend of stress with an increasing amount of WFC, which is consistent with existing micromechanical knowledge: higher WFC content often causes higher pore connectivity, less dense cement matrix and a weaker interfacial transition zone (ITZ), all of which lower the load-carrying capacity of the material, and the close alignment of the experimental and predicted regression lines indicates that the hybrid surrogate is capturing the underlying physical relationship rather than exploiting spurious correlations or random noise in the dataset. In Figure 16a, Blue dots represent the experimental compressive strength measurements at different WFC contents, while black dots indicate the corresponding model-generated or reference dataset values. The solid black line denotes the best-fit regression line for the reference data, whereas the blue dashed line represents the regression fitted to the experimental data. The shaded grey and blue regions indicate the 95% confidence intervals around their respective regression lines, highlighting the uncertainty bounds of the fitted trends.

Further evidence of the model is provided in the Digital Representation Overlay Chart of Figure 16b, where the model is directly compared with the experiment at each stress measurement, and most of the predicted stress values are close to the ideal line Y = X. The fitted regression line fairly well represents the relationship between the model and the experiment, although the small deviations present, particularly in the mid-strength regime, are coherent with experimental scatter because such differences are attributed to measurement uncertainty, crack initiation and growth, and WFC distribution variability. However, the model is unbiased; there is no systematic over or under prediction of strength, which further evidences the stability and reliability of the proposed hybrid framework. In Figure 16b, green dots represent the predicted versus experimental compressive strength values used to evaluate model accuracy. The red solid line shows the regression line fitted to the predicted data, while the black dashed line corresponds to the ideal 1:1 line (Y = X) indicating perfect prediction accuracy. The light red shaded region illustrates the 95% confidence interval of the regression fit, reflecting the associated uncertainty.

Both the physics-based validation and the digital twin analysis reveal that the hybrid system goes beyond simple interpolation and serves as a physics-consistent digital twin of the structural response, with high fidelity in capturing the controlling mechanisms of WFC-modified concrete, because by combining CNN-extracted strain features, PINN-enforced constitutive constraints, and NSGA-II based parametric exploration, the model accomplishes a unique tradeoff between accuracy and interpretability. This fidelity is particularly important for WFC-enhanced concrete, while strong nonlinearities, material heterogeneity, and microstructural uncertainties often limit the accuracy of traditional empirical models.

5.7. Engineering-Oriented Surrogate Expressions and Interpretability

The analytical expressions presented in Equations (4)–(7) are introduced to improve engineering interpretability of the hybrid surrogate framework. With the exception of Equation (7), which combines trained surrogate outputs, these equations are not governing physical laws but post-training or post-optimization approximations derived from the learned or explored response trends. The set of prediction equations provides a clearer and more physically consistent representation of how the hybrid system models the mechanical response of WFC-modified concrete. A physics-consistent surrogate representation derived from the trained PINN predictions is expressed as follows:

The coefficient 25,000 in Equation (4) represents an effective stiffness scale (MPa) inferred from the trained PINN response and reflects the average initial tangent modulus of the tested reinforced concrete beams. It is not a directly measured Young’s modulus but a regression-derived parameter obtained post-training to summarize the dominant stiffness trend learned by the network. Since strain is dimensionless, multiplication by this coefficient yields stress values in MPa, ensuring dimensional consistency. This formulation includes the two main degradation mechanisms that depend on the mixture: the stiffness reduction caused by adding WFC and the porosity increase that happens when the water binder ratio changes. The model’s multiplicative character is in line with well-known micromechanical ideas. According to these rules, clay-based inclusions and too much mixing water lower the effective modulus. This could be because the ITZ is getting weaker and the gel space ratio is decreased. In this context, the PINN functions as a physics based constitutive model. It reconstructs stress responses that correspond with the empirically established pattern of reduced strength at increased WFC replacement levels. This illustrates that the PINN accurately encapsulates mixture-dependent mechanical behavior while maintaining proportionality to the longitudinal strain derived from DIC measurements. This ensures that the observed deformation patterns and the results as constitutive reaction are in line with each other. This expression represents the dominant constitutive patterns learned by the PINN; however, these learned relationships are valid only within the parameter ranges present in the training dataset and are not intended to be extrapolated beyond that domain. A design-oriented response surface derived from NSGA-II Pareto-optimal solutions is expressed in terms of maximum load capacity:

Equation (5) represents an empirical regression surface fitted to the Pareto-optimal solutions obtained from the NSGA-II design-space exploration. The coefficients in this expression are therefore not learned during model training but are estimated post hoc to summarize optimization-driven trends in maximum load capacity as a function of mixture parameters. This relation represents a design-space approximation extracted from Pareto trends and describes the expected variation in maximum load capacity as a function of mixture proportions. Unlike the PINN, which reconstructs the constitutive σ–ε response using strain input and physics-based constraints, this response surface does not predict stress–strain behavior and does not constitute a learning model. It is used exclusively for preliminary mixture-design screening and for visualizing multi-objective trade-offs (strength–cost–CO2) within the bounded optimization domain. The linear penalties associated with WFC concentration and variations in the water–binder ratio accurately reflect the optimization trends: Elevated WFC levels decrease maximum load owing to matrix dilution and compromised ITZ integrity, while W/B ratios above 0.35 introduce additional capillary porosity that significantly reduces load-bearing capacity. The equation thus functions as a swift, mixture-design-centric approximation wherein the mechanical reaction is only determined by material proportions, providing a computationally efficient instrument for initial mixture optimization. An interpretable surrogate expression fitted to the CNN-predicted stress responses is given as

which captures the deformation driven contribution learned from the image based features; however, it should be emphasized that this relationship is a post training regression approximation and is valid only within the deformation ranges represented in the training dataset.. This expression does not represent the internal convolutional operations of the CNN, but rather provides a simplified analytical approximation of deformation-sensitive patterns learned from DIC-derived strain fields. The dominant coefficients associated with longitudinal and transverse strains indicate that the model captures crack orientation, strain localization, and diagonal tension effects.

The final hybrid stress prediction is obtained through a weighted combination of the surrogate representations derived from the trained models:

where α is a validation-calibrated weighting coefficient reflecting the dominant role of physics-informed constitutive consistency provided by the PINN. NSGA-II is not included as a predictive component and is applied only downstream to the hybrid surrogate outputs for multi-objective optimization.

The hybrid surrogate combines the complementary strengths of two physically meaningful models using validation-based weighting. The PINN provides strong consistency with fundamental mechanical behavior, while the CNN enhances sensitivity to local deformation and damage patterns extracted from DIC data. This weighted combination attains significant prediction accuracy (R2 = 0.97), indicating that the integration of physics guided learning with image based deformation data is beneficial within a cohesive surrogate modeling framework.

6. The Limitations of the Study

Although the proposed hybrid framework shows strong predictive performance and remains consistent with physical principles, several limitations should be acknowledged. The surrogate models were trained on a relatively small experimental dataset limited to WFC-modified concrete tested under monotonic loading and a single beam geometry. For this reason, by extending the findings to different mixture designs, curing regimes or structural configurations should be approached cautiously.

The DIC CNN workflow provides detailed information on deformation and damage evolution, but its reliability depends on experimental conditions such as surface preparation, lighting stability, camera calibration, and image noise. Fluctuations in these parameters may diminish feature robustness, especially beyond regulated laboratory settings. The PINN integrates monotonicity and equilibrium restrictions within its loss formulation; yet, its accuracy is fundamentally limited by the simplifying assumptions inherent in these formulations. Consequently, intricate damage events, such as coupled shear/flexural effects, progressive microcrack interactions, or anisotropic material degradation, may not be entirely represented.

Similarly, while NSGA II effectively explores the defined multi objective design space, the current optimization is restricted to load capacity, material cost, and embodied CO2 emissions. Other performance aspects related to durability, including shrinkage, creep, freeze thaw resistance, and fire responses, were not considered and could influence optimal mixture selection under long-term service conditions. Finally, the proposed framework operates as an offline, physics-guided surrogate model rather than a real-time digital twin. Although strong agreement was observed between experimental results and model predictions within the calibrated domain, validation under field conditions or real-time monitoring scenarios has not yet been performed, which limits immediate practical deployment.

The suggested hybrid system, while not a true real-time digital twin, offers a physics-calibrated surrogate model pertinent to engineering decision making. The framework, in its current state, is applicable to offline tasks such as mixture design optimization, structural performance evaluation, and sustainability-focused trade-off analysis of rein-forced concrete systems with supplemental cementitious ingredients. From an engineering standpoint, combining DIC derived deformation characteristics with physics-informed constitutive learning enables physically interpretable forecasting of load-deformation behavior under monotonic loading. This capacity is especially beneficial for evaluating post-peak response, damage progression, and stiffness deterioration, which are sometimes challenging to capture with traditional analytical models. The proposed technique may promote the deployment of a full digital twin in future studies by integrating real-time sensing, automatic data assimilation, and bidirectional updating. This work is intentionally structured as an offline hybrid surrogates model to provide methodological rigor and experimental validation inside a controlled laboratory setting.

7. Conclusions

This study aims to investigate the effects of longitudinal reinforcement diameter, stirrup spacing, and WFC content on the shear and flexural behavior of reinforced concrete beams, and to do so, WFC was added to beams with different longitudinal bar diameters (Φ8, Φ10, and Φ12), stirrup spacings (160 mm, 200 mm, and 270 mm), and replacement ratios (0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%). A total of 24 specimens were tested, with a combination of longitudinal reinforcement, stirrup spacing, and WFC content, and in addition, the Digital Image Correlation (DIC) technique was used to detect and analyze the cracks and microcracks in the beams. The following conclusions can be drawn from this study: